6. Women and the Trail of Tears

Indigenous women in the Southeastern and Northwestern frontiers of the United States, found their communities in direct conflict with expansionist Americans eager to displace them and Southerners who wanted to take their lands to expand slave-based plantations. Cherokee women in particular were affected by this conflict and endured despite the violent expansion efforts. Some white women used their positions to speak out against the atrocities, but more often than not, they were complicit.

How to cite this source?

Remedial Herstory Project Editors. "6. WOMEN AND THE TRAIL OF TEARS" The Remedial Herstory Project. November 1, 2025. www.remedialherstory.com.

In the 1830s, Native Americans were forcibly removed from the Southeastern and Northwestern United States. The removals in the Southeast were deadly and became known as the Trail of Tears, but that term could be used to describe events in the Northwest as well. Centuries of Euro-American ideology had transformed the lives of indigenous women, forcing a divergence in Native definitions of womanhood. By the 1830s, Native women had lost some, but not all, of the privileges and responsibilities they previously held. Men were negotiating with men, and women became witnesses to the horrors of removal. Women were responsible for keeping families together during this removal, in spite of the difficulties they faced.

The Trail of Tears was a shameful and horrific event. This chapter will include discussions of rape and sexual assault, as these are pervasive when violence is used against a civilian population.

American Progress by John Gast is an idealized painting of Manifest Destiny with both racist and sexist portrayals from white and a native American perspective.

Join the Club

Join our email list and help us make herstory!

Manifest Destiny

With the arrival of European settlers in North America, native communities saw aggressive encroachment on lands they used or inhabited. By the 1800s, the expansion of the United States was intentional, stated, and often in violation of prior agreements made with Indigenous communities.

Some politicians even made a career out of championing expansionism. Starting with the purchase of Louisiana Territory in 1803 and through Andrew Jackson’s presidency in the 1830s, the US entered a period of gross and rapid westward movement.

Expansion was fueled by the ideology of “Manifest Destiny,” the idea that it was the United States’ destiny to expand and control the continent from sea to “shining sea.” Lewis and Clark’s exploration into the Pacific Northwest–beyond the Louisiana Purchase territory suggested this idea early on. In fact, maps made as early as 1815 showed the US controlling as far west as California, even though that land belonged to Mexico at that time.

Western expansion as a theme in American history existed long before the term Manifest Destiny was coined in 1845. The idea was visually symbolized in art by John Gast in his famous painting “American Progress” completed in 1872. In the painting, Columbia, a female symbol representing the United States, sweeps across the western territories bringing “civilization” to the “savages'' out wJoest. This piece of American propaganda covered up the wars, massacres, and land theft that occurred in the decades of rapid westward expansion. The image of an angelic-looking woman with a robe and a book takes up most of the frame. A closer examination of the painting, however, illustrates several themes. For one, the image is divided into two halves. Columbia herself is the divider. On the right of Columbia we see all the markers of civilization and progress: canals, railroads, telegraph wires, and farming. On the left side of the image we see all the markers of savagery and primitivism. The left side of the image is dark, but if you look closely, you see animals and indigenous people seemingly running scared–and away–from Columbia. This painting features many of the hallmarks of the Hudson River School–America’s first real school of painting that often relied on themes of the savage and dark juxtaposed against the civilized and bright. In essence, this painting was designed to show man’s power over nature. Ironically, in this painting, the symbol for America was a woman though women aren’t really prominent anywhere else.

A disproportionate number of the figures in the painting are male. The white men are all seen being productive on farms or operating the wagon trains moving west. White women are presumably passengers in the wagons, although their image is difficult to see. The clearest female figures are of Indigenous women, who are shown fleeing with the other native men, topless, or being dragged along.

Although not pictured, debates over expansion were deeply tied to conversations about slavery for, as the US expanded, would those new territories be slave or free?

Manifest Destiny did not occur by some act of God. Rather it was an entirely man-made occurrence. Male leaders in the United States, spurred on by fearful wives no doubt, took direct action to remove and massacred the Native communities that stood in the way of White, settler migrations. The foremost of these men was Andrew Jackson.

.jpg)

American Progress, Public Domain

“Battle Horseshoe Bend”, Public Domain

Andrew Jackson and the Cherokee

Growing up, Jackson listened to stories of native violence toward settlers and developed prejudices, like many Americans. He called Indigenous people “savages” and believed they should be removed to make room for White settlers.

Jackson earned a name for himself after his heroics in the War of 1812 and would go on to found the longest lasting political party in US history, the Democratic Party; however, it would be his treatment of the Cherokee that he would be most remembered for.

In 1814, Jackson tried to wipe out the Red Sticks community in modern Alabama (ironically a Native American word meaning “Great Lands”) in a full on assault. Illustrative of the complicated alliances formed between White and Native communities, he only won this conflict because the Cherokee Nation reinforced him. The Red Sticks lost almost 900 warriors. Junaluska, a Cherokee man, saved Jackson from death. Almost immediately their support was forgotten. Jackson confiscated 23 million acres of land in Alabama and Georgia—some of which belonged to the Cherokees.

The Cherokee and other major tribes of the Southeast lived in fertile land that colonial settlers wanted to exploit for the production of cotton on large plantations. Instead of signing bad treaties with the US and moving west like other tribes, the Cherokee had converted to Christianity, developed a written language, printed a newspaper, and sent children to schools for formal education, in what historians call the Cherokee Renaissance.

Like many indigenous cultures, Cherokee women living in the early 1800s held significant positions in their communities, even after centuries of contact with patriarchal Europeans. It’s true, white men, like Jackson, preferred to deal with Native men in trade and political negotiations, despite women sitting at the helm in most Native communities.

Native American Women, Public Domain

Role of Cherokee Women

Many White, colonial settlers did not comprehend the Cherokee notion of female equality. Women were valued and respected. The most important person in a child’s life was their mother. Fathers had no formal relationship with their offspring. Women could own property and participate in the tribe’s governing councils. In addition, Cherokee women were the guardians of their children, and the culture was matrilineal, with families taking their name and lineage from mothers rather than fathers. Cherokee women were sexually liberated, entering unions by choice and exiting them when they wanted. Sexual relations between consenting adults were always considered natural or spiritual. They did not have the same notions of shame and sin that European or white American women had.

Cherokee women were sometimes sought as marriage partners by white men because they controlled the family wealth and belongings. By marrying Cherokee women, white men could gain access to Cherokee wealth and property; however, white men were shocked to understand that their wives controlled the children and made decisions about property. The Cherokee passed laws that penalized men who abandoned their wives, revoking their citizenship and forcing them to pay fines.

Men and women performed different types of work–men hunted and women gathered food and farmed the land–but for Cherokee women, motherhood was a source of power not oppression. Cherokee women were equals of men and held in high regard. Cherokee “War Women'' even fought in battles alongside men.

The Cherokee also harbored and protected runaway slaves. Hundreds flocked from the plantations onto native territory where they integrated, married, and had children.

Every fall, the Cherokee people held a festival to honor Selu, the Corn Mother, who sacrificed her life so that her sons, and the entire Cherokee people, could live. The festival celebrated the bounty of the harvest and the power of the woman who, according to tribal lore, had saved her people.

But by the 1800s things were beginning to change for the Cherokee. Jefferson purchased the Louisiana Territory and committed the federal government to future removal of the Creek and the Cherokee from Georgia.

Not all Americans endorsed Native removal and instead pushed for civilization and assimilation. For Cherokee men and women, becoming “civilized” meant a complete reversal of centuries old gender norms and major changes in attitudes towards sexuality and the body. The government and missionaries introduced Euro-American and Christian values of “true womanhood” and confined the strong Cherokee women to the domestic sphere. Over time, as marriages and integration between the cultures occurred, this shift happened.

The Cherokee began to feel pressure from all sides and saw civilization as a path to maintaining their traditional homelands. They embraced Euro-American dress and religion, art, and culture. Women ceased farming as that was now men’s work, and men stopped hunting. Women began to lose their sense of what womanhood was as there seemed to be no clear definition. Buck Watie, a missionary among the Cherokee wrote, “A wife! What a sacred name, what a responsible office!... She must be an unspotted sanctuary to which wearied men flow from the crimes of the world, and feel that no sin dare enter there. A wife! She must be the guardian angel of his footsteps on earth, and guide him to Heaven.” This definition of a wife was far removed from the ways of the traditional Cherokee matriarchs. Men’s roles may have felt even more changed than women because they no longer hunted and fought as warriors for the community. Instead they were tied to the land doing what traditional Cherokee saw as “women’s work.” This would have been a big challenge to their masculinity.

Tensions continued to mount. In 1816, the Cherokee sent two young men: John Ross and Major Ridge, to Washington to negotiate with the US government over land that had been taken. They were successful so long as they sold the US land in South Carolina. Nanyehi (“She who walks among the spirits”) had lived through the American Revolution and always been a champion of cooperation between settlers and Natives. Nanyehi was a Beloved Woman of the Cherokee Nation and once a leader of the Nation. Now, she was 80-years old in a declining community. The time for cooperation was over. She sent her son to read a plea signed by twelve women on the Women’s Council, including her daughter and granddaughter: “Our beloved children and head men of the Cherokee Nation, we address you warriors in council. We have raised all of you on the land which we now have. . . . We know that our country has once been extensive, but by repeated sales has become circumscribed to a small track. . . . Your mothers, your sisters ask and beg of you not to part with any more of our land.” The Council passed a resolution vowing not to give another acre to the United States.

A year later, Jackson, as a Federal Indian Commissioned Officer, worked to expel the Cherokee from Tennessee. He used bribes and threats and was successful in getting many to leave. By 1822, Ross and 16,000 remained, resolved to hold the line.

The Cherokee continued to morph their society to be more Euro-American and maintain their autonomy. In 1827 they adopted a new constitution that included an executive, legislative, and judicial branch. The constitution stripped Cherokee women of political involvement. They became disenfranchised and were unable to serve on the Council. Nanyehi’s daughters and granddaughters would have much different lives and roles than she did.

Nanyehi, also known as Nancy Ward, Public Domain

Rachel Jackson

Despite, or perhaps because of, his history as an “Indian Remover,” Jackson eventually won the presidency: an endorsement by the voting American people (white men) of his policies. But Jackson’s path to the Presidency was mired in controversy. He lost the presidential election in 1824 in a bitter battle with John Quincy Adams. The 1828 rematch cost Jackson dearly. Up for reelection, Adams’ supporters were ready for him and decided to focus their ire on Jackson’s wife– Rachel.

Adams’ supporters argued that Jackson was unfit to be president because of the circumstances surrounding his marriage. Although the Jacksons had been married for nearly 40 years by the time of this election, those years were all negated by the troubled beginning of their marriage. Rachel was a “divorcee.” And worse, evidence came into Adam’s hands that her divorce from her first husband was never finalized because her first-husband never completed the paperwork..

The Adams campaign dug into this scandal and attacked Rachel’s morals. They called her a whore and branded her the “American Jezebel,” (See our Episode on Christianity for the history of that term).

The Jackson’s fought back by publishing a pamphlet, renewing their vows, and casting Jackson as a defender of women. He ultimately won the election, but Rachel was devastated by the vile attacks on her character, and they quickly took their toll. Unexpectedly, Rachel died of a heart attack. A source close to Jackson later wrote “These slanders, it is thought, hastened the death of Mrs. Jackson, and they certainly roused the devil in her husband’s nature.”

Rachel was buried in the dress she had planned to wear to her husband’s inaugural ball. After the bitter attacks and death of his wife, Jackson was a bitter man when he entered the white house as the first Democratic president. Jackson felt women's virtue was worth defending and this would become clear in another episode during his presidency.

Rachel Jackson Circa 1823, Public Domain

Peggy Eaton

With Rachel in his mind, Jackson soon came to the defense of another white woman wrapped up in an American political scandal: Margaret “Peggy” O’Neale Timberlake, who had just married his Secretary of War, John Eaton. Peggy’s first husband died at sea and Peggy eventually married John Eaton. But rumors soon surfaced that Peggy and John had been having an affair while she was married. Because of these rumors, many of the elite women in Washington, D.C. refused to socialize with her.

Floride Calhoun, the wife of the Vice President was the ringleader of the society ladies and would not attend events if Peggy was there. Because Peggy’s father owned a tavern, rumors also swirled that Peggy had been sexually promiscuous and perhaps even a sex worker. Since a woman’s social status was tied to her perceived virtue, these women feared Peggy’s potential promiscuity would malign them by proxy.

Jackson took the Eatons’ side during this scandal, which was referred to as the “Petticoat Affair,” and privately and publicly defended the couple. Ultimately the affair was resolved by Jackson dismissing members of his cabinet and sending them out of Washington to other political appointments. When asked about the scandal, Jackson remarked, “I would rather have live vermin on my back than the tongue of one of these Washington women on my reputation.”

It’s clear from the Eaton Affair that women in Washington held political sway–even power to change a presidential cabinet. This event also showed that Jackson did present himself as a defender of women, but what about women of color? How did this softer side extend to his policies toward the Native Americans and the enslaved? In short, it did not.

Indian Removal Act

Removal of Native Americans from the southeast was one of Jackson’s top priorities in office. In 1830, Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act into law, giving the federal government the power to exchange Native-held land in the cotton kingdom east of the Mississippi for land to the west, in “Indian Territory” located in present-day Oklahoma. This exchange would also result in the forced removal of the indigenous people from the cotton territory to Indian Territory.

The Cherokee appealed their forced removal in the 1832 US Supreme Court case Worcester v. Georgia. The court objected to native removal and affirmed that native nations had “sovereignty.” They wrote, “the laws of Georgia [and other states] can have no force.” President Andrew Jackson ignored the Court’s decision, saying, “Justice Marshall has made his ruling, Now let him enforce it.” This was a flagrant disregard for the separation of powers foundational to American democracy.

Not all white Americans approved of removal. In December of 1839, reformer Catharine Beecher wrote a circular, “Addressed to the Benevolent Ladies of the United States.” She exhorted women to appeal to the government to stop the removal policy and protect the natives. Appealing to women, she asked, “Have not then the females of this country have some duties devolving upon them to this helpless race?” Beecher used biblical language from Exodus 22: 21-24 to support her claim that women had a responsibility to try to influence their government.

More than 1,400 women from Monson, Massachusetts to Steubenville, Ohio signed petitions on behalf of the Native Americans. Women in Hallowell, Maine asserted that they were “unwilling that the church, the school, and the domestic altar should be thrown down before the avaricious god of power.” But American women could not vote and their pleas fell on deaf ears.

The Cherokee took the Supreme Court victory as a chance to argue another pressing case. Many Christian Missionaries in the south, sent to Christianize the Native Americans, preferred life with the Cherokee. The state of Georgia began forcing these white missionaries to swear allegiance to the state. When the missionaries refused, they were arrested. Again the Court sided with the Cherokee. They ruled that Georgia had no power on Native lands and that the federal government could intervene to protect the Cherokee from state intrusions.

Dr. Elizur Butler was one such missionary. He moved with his first wife to serve the Cherokee as a missionary and stayed for decades. When his first wife died, Dr. Butler then married Mrs. Lucy Ames who had served as a teacher at the Brainard Mission. In the tensions over Cherokee lands, the Georgia Militia arrested Butler,with other men, for residing in the Cherokee Nation without a permit. Butler was eventually released early by the Georgian Governor after two years of hard labor. What his wife did and thought during this time is lost, though she would play an important role later on.

Jackson was intent on enforcing the Indian Removal Act. A few tribes negotiated treaties that promised that they would be well-treated, but they were nevertheless forcibly removed from their land. In the winter of 1831, with the US Army at their doorstep, the Choctaw became the first of many Native nations who would be forced from their homeland on what would become known as the Trail of Tears. They marched 1,000 miles on foot, some in chains, without food or supplies. Along the way, they were subjected to brutal treatment, including the rape of many women.

Although some of the generals directly tasked with indigenous removal advocated for more resources and time in an attempt to treat the people more humanely, Jackson pushed for haste and economic efficiency– directly resulting in the greater suffering of the indigenous people.

Trail of Tears

In 1836, the Creeks were driven from their homes. An estimated 3,500 of the 15,000 Creeks died from diseases such as whooping cough, typhus, dysentery, cholera as well as fatigue.

By 1838, only about 2,000 Cherokees had complied with removal orders, so President Martin Van Buren, who had been Jackson’s Vice President during his second term, ordered 7,000 soldiers to speed up the process, marching the Native families, the elderly and children included, at bayonet point.

Major Ridge, a Cherokee leader who had been negotiating with the US for decades, saw the situation as it was and tried to convince his tribe to leave; however, doing so without sounding like a traitor to their cause was undoubtedly a difficult line to walk. In 1838, Ridge signed a conciliatory treaty with the US, a decision he described as his “death warrant.”

Ridge was considered a traitor, and his former partner in negotiations, John Ross, worked to overturn the treaty. In May 1838, the US Army herded over 16,000 Cherokees into holding camps and began marching them west. Worse, Natives who fled were shot. Women in these camps, and along the trail, were sexually assaulted by US soldiers imprisoning them– a gendered strategy to humiliate not only the women, but their male family members, as well. Sexual assault served as a way of emasculating the men and reminding them of their weakness through their failure to protect. It is also the result of unequal power relations. So many Cherokee died that the Army postponed the rest of the march until the fall– forcing the Cherokee to march through the frigid winter months.

Major Ridge moved westward with the Cherokee on the Trail of Tears, but divisions within the Cherokee tribes were deep and Ridge was ultimately murdered by his own people.

One Cherokee woman, Wahnenauhi, recalled her experience during the beginning of the Trail of Tears and forced removal of the Cherokee people. “They were gathered up and driven, at the point of the bayonet, into camp with the others. [T]hey were not allowed to take any of their household stuff, but were compelled to leave as they were, with only the clothes which they had on. One old, very old man, asked the soldiers to allow him time to pray once more, with his family in the dear old home, before he left it forever. The answer was, with a brutal oath, ‘No! no time for prayers. Go!’ at the same time giving him a rude push toward the door. Indians were evicted, the whites entered, taking full possession of everything left.”

Dr. Elizur Butler accompanied the Cherokee on the Trail of Tears. Lucy described the scene in a letter to a friend: “When these companies arrive in their new country, the greatest part will be without shelters as they were in this [place], after they were prisoners; and it is to be feared many will be cut down by death, as has been the case with new emigrants in the country… Will not the people in whose power it is to redress Indian wrongs awake to their duty? Will they not think of the multitudes among the various tribes that have within a few years been swept into Eternity by the cupidity of the ‘white man’ who is in the enjoyment of wealth and freedom on the original soil of these oppressed Indians?”

Eliza Whitmire was about five years old when she and her parents, who were enslaved to a Cherokee family, were forced to leave Georgia. She later described the process of removal: “The women and children were driven from their homes, sometimes with blows and close on the heels of the retreating Indians came greedy whites to pillage the Indian's homes, drive off their cattle, horses, and pigs, and they even rifled the graves for any jewelry, or other ornaments that might have been buried with the dead… The aged, sick and young children rode in the wagons, which carried provisions and bedding, while others went on foot… all who lived to make this trip, or had parents who made it, will long remember it, as a bitter memory.”

Rachel Dodge recalled the stories of her Grandmother, Aggie Silk, from the Trail of Tears, giving a look into the harsh conditions that faced the men, women, and children on the trail. “Aggie Silk was my grandmother and she has told me of the many hardships of the trip to this country. Many had chills and fever from the exposure, change of country and they didn't have too much to eat. When they would get too sick to walk or ride, they were put in the wagons and taken along until they died. The Indian doctors couldn't find the herbs they were used to and didn't know the ones they did find, so they couldn't doctor them as they would have at home. Some rode in wagons, some rode horses and some had to walk. There was a large bunch when she came; she was sixteen years old. They were Cherokees and stopped close to Muldrow where they built log houses or cabins but they didn't like this country at first as everything was so strange.”

Elizabeth Watts, the daughter of a woman who was born along the Trail of Tears, recounted her mother’s story of the removal in an oral history: “Even before they were loaded in wagons, many of them got sick and died… The trail was more than tears, it was death.”

Another oral history described: “Sin-e-cha…had left her home and with shattered happiness she carried a small bundle of her few belongings and reopening and retying her pitiful bundle she began a sad song… ‘I have no more land. I am driven away from home, driven up the red waters, let us all go, let us all die together and somewhere upon the banks we will be there.’”

Josephine Usray Lattimer was interviewed by Amelia Harris. She said, “Even for all the well and strong, the journey was almost beyond human endurance. Many were weak and broken-hearted, and as night came there were new graves dug beside the way.”

At least 4,000, but possibly 8,000, Cherokees did not survive the Trail of Tears. Those figures don’t include the thousands more Creek, Choctaw, Seminole, and other natives who perished in this forced removal.

Trail of Tears Map, Public Domain

“The Trail of Tears”, Public Domain

Northwestern Removal

Similar tensions played out in the Northwestern Territory at the same time as the Trail of Tears. Again, treaties were mishandled, arguably fraudulent, and it resulted in war and the eventual forced removal of Native Americans. The brief and bloody Black Hawk War in 1832 opened new territory for white settlement. Millions of acres of land in present-day Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin was taken from the Sauk, Fox and other nations.

In this region too, women played an important role. Sauk and Mesquakie women held positions of power in their communities. These communities thrived on sustainable systems of land use, cycling through hunting, gathering, farming, fishing, and sugar-making as the seasons directed. Men and women were essential to this subsistence labor, much to the chagrin of European onlookers, who claimed these “laboring women” were slaves to their men. Men and women spent portions of the year apart, as men left to follow game, trap, and hunt. While the men were gone, women, children, and the elderly processed maple sugar for sustenance.

Mixed race women (called Métis by the French Canadians) in these communities often serve as liaisons with the intruding white settlers, often because their heritage ensured they spoke multiple languages. Seen as “public mothers” they helped bridge cultural barriers and negotiate between groups. Metis women also resisted colonization in their own ways. Elizabeth Thérèse Fisher Baird wrote a memoir describing her experiences. Others aligned themselves with resistance groups. When Black Hawk organized a rebellion against an unjust treaty, women were behind him. Women were some of his strongest allies because their contributions to the communal economy relied on their familiarity with the land. Violating a treaty they deemed unjust, Black Hawk and his followers crossed the river into Illinois to harvest crops from their fields. The settlers responded by requesting troops to reinforce them. Bloody skirmishes erupted, people were scalped and massacred. Two white teenage girls were kidnapped and ransomed back, but the Sauk were losing. Retreating quickly they abandoned the slow and weary, leaving children and the elderly to be picked off by the US Army.

Like the Natives of the Southeast, the communities of the Northwest were also forced further west. By 1837, their lands, farms, and territory were being used by white families.

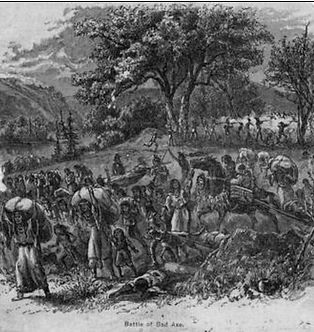

Battle of Bad Axe from the Black Hawk War, Public Domain

Migration to the West of the Muskogee

Another personal account of the migration of indigenous people comes from Mary Hill, who recounts her grandmother, Sallie Farney’s experience of forced migration from Alabama to the western

continental U.S. Just prior to the beginning of the Trail of Tears, the Muskogee people were located in Alabama and believed “Alabama was to be the permanent home of the Muskogee tribe. But many different rumors of a removal to the far west was often heard.”

Sallie told of how these rumors or removal suddenly became a reality to Sallie and her people. Sallie recounts how one day the Muskogee people were commanded to forcibly leave their homes: “Wagons stopped at our home and the men in charge commanded us to gather what few belongings could be crowded into the wagons. We were to be taken away and leave our homes never to return. This was just the beginning of much weeping and heartaches.”

Sallie explains how people were often “penned up,” put into closed quarters with other tribes, and separated from family and loved ones, before even beginning the dangerous forced migration west. Once they began moving west, Sallie elaborates on what the indigenous people who became sick during the forced migration faced: “Many fell by the wayside, too faint with hunger or too weak to keep up with the rest. The aged, feeble, and sick were left to perish by the wayside. A crude bed was quickly prepared for these sick and weary people. Only a bowl of water was left within reach, thus they were left to suffer and die alone.

The little children piteously cried day after day from weariness, hunger, and illness. Many of the men, women, and even the children were forced to walk. They were once happy children - left without mother and father - crying could not bring consolation to those children. The sick and the births required attention, yet there was no time or no one was prepared. Death stalked at all hours, but there was no time for proper burying or ceremonies. My grandfather died on this trip.”

Sallie notes in her oral history how it was many of the women of the Muskogee people that were able to encourage the continued perseverance of their tribe. “Some of the older women sang songs that meant, "We are going to our homes and land; there is One who is above and ever watches over us; He will care for us." This song was to encourage the ever downhearted Muskogees.”

Sallie’s telling of the horrors, sadness and despair of the forced removal of her people shows the subhuman treatment that was forced upon the indigenous people removed during the Trail of Tears. However, Sallie’s own recount also shows the bravery and honor of many women in the Muskogee.

Women of the Muskogee tribe exhibited immense perseverance, strength, and resilience in the face of oppression and suffering. Their continued strength, support, and sense of community helped the Muskogee people to survive the terror and horror of their forced removal and migration. Sallie’s oral history is one of the many stories that showed the resilience of these women and how they contributed to the prosperity of their tribes.

Scenery of the Upper Mississippi: An Indian Village, Public Domain

Aftermath

Traumatized, and with few resources, women in these communities found the strength and resilience to rebuild. They built new homes, churches, and schools. Ross’ leadership ensured the reluctant government paid them for their lands in the east. Women raised their families and did the important work of enduring and surviving. They shared their stories and told the history of what happened to their people.

Dr. Butler and his wife Lucy continued to serve as Missionaries with the Cherokee. He was a teacher at the Cherokee Female Seminary prior to his death in Arkansas in 1857. This work helped Cherokee women find strength and have economic opportunities moving forward.

Not all missionary work was embraced however. The long history of Euro-American and Christian ideology left bitter resentments. Sophia Sawyer, a female Christian missionary, apparently chased a local woman hoping to convince her to send her child into the missionary school. The Cherokee woman responded that she would “as soon see her child in hell as in the mission classroom.”

At the end of the century, Helen Hunt Jackson published an important book, A Century of Dishonor, that exposed the treatment of the indigenous population. She wrote, “There is no escape from the inexorable logic of facts. The history of the Government connections with the Indians is a shameful record of broken treaties and unfulfilled promises. The history of the border, white man’s connection with the Indians is a sickening record of murder, outrage, robbery, and wrongs committed by the former, as the rule, and occasional savage outbreaks and unspeakably barbarous deeds of retaliation by the latter, as the exception… The testimony of some of the highest military officers of the United States is on record to the effect that, in our Indian wars, almost without exception, the first aggressions have been made by the white man.” She spoke the truth.

Helen Hunt Jackson, Public Domain

Conclusion

The federal government promised that their new lands in Oklahoma would remain untouched by Americans forever, but of course the US continued expansion westward. In 1907, Oklahoma became a state and Indian Territory was considered lost. Native women struggled alongside other American women in a quest for rights they had once held but lost through intrusions of Euro-American ideals.

Ironically, this “barren land” reserved for Native Americans so that the more fertile lands in the east could be cultivated for cash crops and the expansion of slavery held a secret. In 1859 the Ross family discovered oil. In a great twist of fate, native families who owned the headrights to the oil would become incredibly wealthy as the need for oil to fuel the industrial revolution took off. Headrights could not be bought or sold, only inherited– and since traditional communities were matrilineal, this meant this wealth passed from mother to daughter for generations.

Nevertheless the Cherokee Women endured. At the end of the 20th century, many Cherokee women re-entered the public stage. Their achievements from service to their community outweighed any personal achievements. In Oklahoma, 1985, Wilma Mankiller succeeded a male banker and became the principal chief of the Cherokee Nation in Oklahoma.

Similarly, in 1995, women from the Eastern range of Cherokees from North Carolina impeached Joyce Dugan, a corrupt chief. The success of these Cherokee women is a testament to their ability to embody the values exhibited by Cherkoee women as well as showing how the Cherkoee nation is not a history of decline and loss of culture, but of perseverance, change, tragedy, and ultimate survival.

By the end of this era, so much remained in question. What would happen to the remaining native tribes west of the Mississippi? Would Native people ever be considered US Citizens? And if so, would they want to be?