24. The Feminist Era

Following the most active period of the Civil Rights and Antiwar movements, women were inspired to fight for equality and opportunity in movements of their own. Unlike the institutional and legal gains of the Second Wave feminists, smaller and diverse movements emerged to combat sexism in local communities.

How to cite this source?

Remedial Herstory Project Editors. "24. THE FEMINIST ERA" The Remedial Herstory Project. November 1, 2025. www.remedialherstory.com.

The Civil Rights and antiwar Movements inspired other groups in America to speak up and fight for greater equality and opportunity in society. Women had achieved sweeping changes in law and society that dramatically altered social dynamics and improved women’s status. Major organizations like NOW were established, and a presidential commission on women was made to focus on the status of women around the country. As a result major legislation known as Title IX passed and the ERA, or Equal Rights Amendment, was proposed. It was a time of huge change.

Soon, other social movements arose to demand and fight for Native American, Gay and Lesbian, and Latino rights. Women involved in these various movements continued to experience sexism as they implemented methods of political organizing and tactics to achieve goals learned in the earlier struggles. Over time, they found the language needed to express their own frustrations. The late 1960s witnessed the rise of the women’s liberation movement in which American women fought against their second class status in society.

ERA March, 1979, Public Domain

Join the Club

Join our email list and help us make herstory!

Frustrations Facing Women

Women struggled against employment discrimination as they entered the workforce in greater numbers. In 1960, women made up only 6% of the nation’s doctors, 3% of its lawyers, and less than 1% of engineers. Over a million worked for the federal government but made up just over 1% of the civil service workers in the top 4 managerial pay grades. Women found themselves routinely passed over for positions that led to management training and executive responsibility. The earnings of women working full time jobs averaged only 60% of that of men working full time. State minimum wage requirements exempted most traditional women’s jobs, and Help Wanted advertisements were often segregated by gender, making it clear that were jobs for which women could not apply.

Beyone employment practices, many laws discriminated against women. Banks could refuse to issue a credit card to an unmarried woman. If a married woman requested credit, the card would be issued in her husband’s name. Banks often did not include a married woman’s earnings when calculating the family’s income for a loan application. In many states, women were excluded or exempted from serving on juries due to the belief that jury service interfered with their primary responsibility as caregivers. Women’s nature was cited as additional reasoning, claiming women were too fragile to hear about grisly crimes or too sympathetic to remain objective. Birth control was restricted in many states and was only prescribed to married women for the purpose of family planning.

In STEM fields, while some women were breaking barriers in science, women were struggling to access career options. In 1977, Rosalyn Yalow was the second woman to win a Nobel Prize when she and her colleagues won the award in Physiology or Medicine for the creation of radio-immunoassay, a technique to accurately and quickly measure a concentrations of hormones, vitamins, viruses, enzymes, drugs, and more. The next year, Anna Jane Harrison was the first woman to be elected president of the American Chemical Society. However, women were still actively and passively discouraged from pursuing careers in science and technology. Jewel Plummer Cobb was a cell biologist and cancer researcher who, in 1979, wrote one of her most famous articles, “Filters for Women in Science,” which systematically analyzed the barriers facing women entering the field.

Maurine Neuberger-Solomon a Senator from Oregon 1962, Public Domain

Race

Feminists in this period did a better job than the suffragists era at being “intersectional,” a term used to describe the way a movement includes the needs of the diverse populations. The earlier feminist movement had been led by middle-class white women. They focused on their own concerns, which caused a complicated and sometimes conflicting relationship with women from different social classes and races. The new phase of feminism was more inclusive but still had a long way to go. Women of color in particular were pushed to the sidelines of the movement.

Black women had to confront both racism and sexism, and they had to find ways to make Black men aware of gender issues while making white women aware of the importance of race. Black feminists such as Michele Wallace, Mary Ann Weathers, bell hooks, and Alice Walker, addressed these complex issues in their work. In 1973, activists from the National Black Feminist Organization recognized that the aims of the feminist movement, including day care, abortion, maternity leave, and ending violence against women, would benefit Black women and their families. Despite the frustrations, Black women and white women were able to build strong coalitions.

Alice Walker, Public Domain

President’s Commission

The women in leadership roles began pushing the government for action. In 1961, Esther Peterson, Assistant Secretary of Labor for Women's Affairs, suggested the creation of a President's Commission on the Status of Women. Established by President Kennedy by executive order, the bipartisan commission was chaired by Eleanor Roosevelt to examine discrimination against women and make recommendations on ways to eliminate it. The order stated “prejudices and outmoded customs act as barriers to the full realization of women's basic rights which should be respected and fostered as part of our Nation's commitment to human dignity, freedom, and democracy.” The commission found that women faced barriers that limited their opportunities for employment and advancement. It recommended that women have the opportunity to compete for federal contracts, advocated changes to discriminatory state laws, and supported affordable daycare and equal access to education for women. The creation of the President's Women led to the establishment of similar commissions across the country. It helped to bring together women working for various women’s issues who had never met. Together, they created data that the women’s movement needed to challenge legislation at the federal and state level.

The early 1960s saw the passage of important federal legislation to help women. One direct result of the President's Commission on the Status of Women was the passage of the Equal Pay Act of 1963. It prohibits employers from paying unequal wages to men and women working jobs that require “equal skill, effort, and responsibility, and which are performed under similar working conditions.” This was one of the first pieces of federal legislation to address gender discrimination. It was followed by the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The legislation was a result of the hard work of the Civil Rights Movement and prohibited segregation in public places. It also banned employment discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion,or national origin. Representative Howard Smith (VA) proposed an amendment to include sex as an employment discrimination category, a move that would have likely killed the bill. Representative Martha Griffiths (MI) and the other female representatives lobbied in support of the provision, and it was included in the bill that passed the House. Senator Margaret Chase Smith (ME) championed the bill in the Senate, and it was signed into law by President Nixon in 1972. The law established the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission to help enforce the anti-discrimination provisions of the law.

.jpg)

Esther Peterson, Public Domain

The National Organization for Women

In 1966, the Third National Conference of Commissions on the Status of Women was held with the theme “Targets for Action.” One issue of concern was the EEOC’s failure to enforce the prohibition on sex discrimination in employment. The EEOC refused to use its limited resources to act on women’s claims, feeling its main duty was to help African American workers. Attendees such as Betty Friedan and Pauli Murray became frustrated with the lack of action at the conference and wanted to make the theme a reality. Friedman invited a group of women to her hotel room and wrote NOW on a napkin, National Organization for Women. Friedan and Murray created a new organization to fight for women’s rights to “take action to bring women into full participation in the mainstream of American society now, exercising all the privileges and responsibilities thereof in truly equal partnership with men.” NOW pressured the EEOC to hold hearings about sex discrimination in employment ads and uphold its mandate to prohibit sex discrimination. NOW also lobbied the White House to expand affirmative action programs to include women and Congress to pass more legislation to benefit women.

The Stonewall Riots

Throughout the first half of the 20th century, LGBTQ+ people remained largely closeted, leading dual lives. Gay bars were the center of a quiet gay culture. They were secretive, a safe space, and even a spiritual experience for many queer people. Gay bars were frequently raided and queer people arrested and charged with the crime of sexual deviance. This changed dramatically after a riot at the Stonewall Inn in New York City in the early morning hours of June 28, 1969. Stormé DeLaverie, a butch lesbian who sometimes performed in drag, was at the bar that night. When the police raided the facility under the guise of protecting decency, they beat and abused patrons. DeLaverie’s altercation with police became the catalyst for the riot. She was arrested, handcuffed, and beaten by police. Bloodied and fighting with police she yelled, “Why don’t you guys do something!?” The crowd reacted with decades of pent up injustices and resentment. Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera, two trans women of color, were in the bar that night as well and fought back against police in what became the larger Stonewall Riots.

LGBTQ+ leaders organized the Gay Liberation Front (GLF) immediately following the Stonewall riots. Women were among the primary advocates in GLF marches. They held fundraising dances, conducted consciousness-raising groups, and formed radical study circles. They also established their own publication called "Come Out!" operating from the Alternate U on Sixth Avenue and 14th Street. Over time, GLF transformed into a network of semi-independent cells. But the focus of these cells often revolved around integrating gays and lesbians into the mainstream culture, often at the expense of the others like bisexual and transgender people.

After the riots, Johnson, a trans woman, co-founded the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR) organization alongside Sylvia Rivera. They felt the work of the mostly white, middle class gays and lesbians was excluding trans people. STAR aimed to provide support, advocacy, and housing for homeless transgender youth in New York City. Marsha and Sylvia's work with STAR and presence did not fit within the assimilationist goals of lesbians. Johnson was known for her vibrant personality, advocacy work, and dedication to helping those in need. Rivera considered her to be like a mother figure. Rivera struggled with homelessness her entire life and attempted suicide. Johnson mentored her and helped her to heal. Rivera left activism for a bit to recover.

Sadly, Johnson's life was cut short when she was found dead in the Hudson River in 1992. While her death was initially ruled a suicide, there have been ongoing efforts to reexamine the case and seek justice for her untimely passing. Hundreds of people attended her funeral. It was standing room only. The police reopened her case in 2012.

Feminists were not always inclusive of their LGBTQ+ sisters and often saw the gay rights movement as separate from feminist struggles. The most notable example of this was Betty Friedan the president of the National Organization of Women (NOW), author of The Feminine Mystique, who also promoted anti-gay propaganda. Freidan coined the term “lavender menace” in reference to the increasing number of “out” lesbians. Other women in the movement were more inclusive and intersectional in their approaches to feminism, but prominent women like Friedan undercut them.

At a NOW meeting in 1970, lesbians from Radicalesbians, the GLF, and other feminist groups staged a theatrical demonstration to rally feminists behind the cause of lesbians. In the middle of the programing, they shut off the lights. There was some shuffling and when the lights came back up the isles were lined by lesbians wearing shirts with Betty Friedan’s words: “Lavender Menace.” They all held signs that read, “We are all lesbians,” “Lesbianism is a women’s liberation plot,” or “We are your worst nightmare, your best fantasy.” The Menaces seized the microphone and held it for two hours, demanding that NOW take up the cause of the lesbian. This uprising by the Lavender Menace gave lesbians a voice and visibility in the mainstream feminist movement. NOW acknowledged the challenges and oppression facing lesbians by passing a resolution acknowledging the double-oppression of lesbians as women and homosexuals and recognizing the “oppression of lesbians as a legitimate concern of feminism” in 1971. Friedan maintained her homophobia for sometime afterward.

In addition to fighting for legislation, NOW and other women’s organizations, such as the ACLU Women’s Rights Project fought in the courts. Decided in 1971, the Supreme Court ruled in Reed v Reed that a law that discriminated against women was unconstitutional. This landmark case was followed byRoe v. Wade in which a woman was allowed to choose whether or not to terminate a pregnancy. The Supreme Court went on to invalidate state and federal laws and local customs that differentiated between sexes such as the sex-separte male and female help wanted ads.But the Court failed to hold sex discrimination to the strict scrutiny standard it used for race.

NOW also campaigned for women running for office. They supported the campaign of Shirley Chisholm who became the first Black woman elected to the House of Representatives. In 1971, Chisholm, along with other women leaders including Friedan, newly elected Representative Bella Abzug, and activist and Ms. Magazine founding editor, Gloria Steinem, founded the National Women’s Political Caucus. This organization is “dedicated exclusively to increasing women’s participation in all areas of political and public life.

In 1974, Kathy Kozachenko, a lesbian was elected to the Ann Arbor City Council in Michigan and became the first openly gay person elected to political office. Then, Elaine Noble was elected to the Massachusetts House of Representatives. They both predate Harvey Milk, who is often misattributed as the first openly gay official.

Organizations like the Gay Liberation Front and Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR) played pivotal roles in advocating for both mainstream acceptance and the rights of the most vulnerable within the LGBTQ+ community. Furthermore, the academic and scientific validation of LGBTQ+ identities, such as the American Psychological Association's declassification of homosexuality as a mental illness, paved the way for societal change. Despite significant challenges, the persistent efforts of activists, feminists, and politicians—who fought both within and outside their movements for inclusion—fostered a sense of empowerment and solidarity.

_-_colorized.jpg)

Stormé DeLarverié (center), surrounded by three female impersonators at Roberts Show Club, Public Domain

%3B_Barb.jpg)

NOW founder and president Betty Naomi Goldstein Friedan and co-chair Barbara Ireton, and feminist attorney Marguerite Rawalt, Public Domain

Elaine Noble 1975, Public Domain

Feminist Era Culture

Feminist culture also provided opportunities for young girls to re-think aspects of their lives. A pre-feminist doll, Barbie, encouraged critiques of female stereotyp[es and the ways in which women were portrayed in toys for children. Barbie, an 11-inch (29-cm) tall plastic doll resembling an adult woman, was introduced by Mattel, Inc. in 1959. Ruth Handler, co-founder of Mattel, alongside her husband Elliot, led the development of the doll. Since Barbie's launch, her body shape has been controversial. In a 1958 Mattel-sponsored market study, mothers criticized Barbie for having "too much of a figure." She was exclusively white, too tall, had impractical feet, large breasts, and an unrealistic waist. To address this, Mattel marketed Barbie directly to children through television commercials, becoming the first toy company to advertise to children when it sponsored Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse Club in 1955. Despite the criticism, many women credit Barbie with providing an alternative to the restrictive gender roles of the 1950s. Unlike baby dolls that encouraged the act of nurturing, Barbie, with her various career outfits, modeled financial independence. Her résumé includes roles such as airline pilot, astronaut, doctor, Olympic athlete, and US presidential candidate. Barbie has no husband or children, and when consumers requested a Barbie-scale baby in the early 1960s, Mattel released the “Barbie Baby-Sits” playset instead of making Barbie a mother.

In response to consumer demand, Mattel introduced Barbie's boyfriend, Ken, in 1961, named after the Handlers' son. In 1963, Barbie's best friend Midge was introduced, followed by her little sister Skipper in 1964. Other siblings were added and by 1968, Barbie had friends of color. However, an African American and Latina Barbie were not released until 1980. Although the goal was to create Barbies that could do any job (President Barbie, Astronaut Barbie, etc.), Barbie faced criticism for promoting materialism and narrow ideas of womanhood.

Toy maker Annalee Thorndike dedicated herself to her childhood hobby of doll making after the family farm in New Hampshire failed. A repurposed chicken coop became her design studio and her husband, Chip, became her salesman. Thorndike concentrated on creating female figures engaged in everyday activities, with categories for occupations, sports, and hobbies. Thorndike was ahead of her time and found ways to support the people, mostly women, who worked for her. She offered childcare and flexible work hours and the ability to care for their children. As a working mother, Annalee knew how difficult it was to juggle work and home. Although she faced sexism from banks who refused to work with her because she was a woman and women couldn’t open accounts or take out loans without male cosigners, her dolls were the largest manufactured item from New Hampshire. In 1974, Thorndike was named the “Business Person of the Year” by the United States Small Business Administration.

Women were increasingly seen and heard in popular music. Motown stars such as Gladys Knight and Aretha Franklin, hard rockers like Janis Joplin, folk singers who spoke to social issues, including Judy Collins, Joan Baez and Joni Mitchell, and popular songwriters like Carole King, whose reflexive ballads captured the spirit of the early 1970s, all brought the issues of their time to their music, appealing to men and women alike. By the early 1970s, young Americans knew that their time was fundamentally different from that of their parents. At the same time, singers like Tina Turner sang in her own dynamic style in songs that revealed the pain of a woman’s life, much as the female blues singer of the 1920s had done.

Eunice Walker Johnson was a fashion entrepreneur who founded Fashion Fair in 1973 with her husband, John H. Johnson. The company catered to the makeup needs of women of color, prompting major brands like Revlon, Avon, and Max Factor to expand their shade ranges. Johnson also created the Ebony Fashion Fair, a nationwide tour showcasing couture and ready-to-wear clothing for a predominantly Black audience, supporting and promoting Black designers and models.

Ruth Handler, posing with collection of Barbie dolls, 1961, Public Domain

Women's Sports

Women made history in sports by breaking barriers of prejudice, but they were not always well-liked or celebrated in mainstream pop culture. Even stars that we remember with awe were frequently portrayed negatively in the press during their careers. Female athletes were often assumed to have been lesbians or that they were too “manly” both in behavior and physicality. Some of these stereotypes persist today.

One of the biggest threats to feminism were pervasive myths about women’s supposed physical inferiority. This bled into everyday life, including in job prospects and comparisons of men’s and women’s sports. Many, both men and women, believed, without evidence, that women’s bodies simply could not sustain certain sports like running.

Although women had gained entrance into track, distance running was still barred to them competitively. The logic that had been disproved in the 1920s that distance running would be harmful to women’s reproductive potential resurfaced in the 1960s.. Of course, this was nonsense, but it kept male race directors from permitting women to race. In 1965, the untrained and uncoached Bobbi Gibb was running recreationally for up to 40 miles at a stretch. She wrote to the Boston Athletic Association (BAA), to earn official entry to the 1966 Boston Marathon. They responded:

“We have received your request for an application for the Boston Marathon and regret that we will not be able to send you an application. Women are not physiologically capable of running a marathon and we would not want to take on the medical liability… Sorry, we could not be of more help.”

It wasn’t just the race director who disapproved, it was also her then husband. He forbade her from racing. She took barely enough money and rode a scooter to the bus station and rode the bus across the country from San Diego to Boston, where she stayed with her parents. Her father also disapproved, stating that she was delusional and feared she might die. He told her emphatically that she could not run. Her mother relented and drove her to the starting line.

Along the course, many men cheered her on and at the finish, the Governor of Massachusetts shook her hand. She returned to run in Boston in 1967 and 1968, where she also finished first in the unsanctioned field.

In 1967, another woman made history, Katherine Switzer who trained with her boyfriend and coach and entered the race officially as K. Switzer. Wearing an official bib, she ran the course. The media swarmed her and followed. Part way along, the race director showed up and physically tried to pull her from the course. Her boyfriend and coach played bodyguard. She finished. In 1972, the AAU finally changed their rules and the first official women’s field was accepted, but it took women who defied conventional wisdom and intimate oppression to get there. Kathrine Switzer’s historic run as the first woman to compete in the Boston Marathon in 1967 shattered gender barriers in distance running. Similarly, Marilyn Bevans became a trailblazer as one of the first prominent Black female marathoners. Bobbi Gibb, who ran Boston unofficially before Switzer, also played a crucial role in advancing the sport for women. Oprah Winfrey’s embrace of recreational running helped popularize the activity, bringing the “running boom” to a wider audience and inspiring countless women to take up the sport.

In 1968, at just age 13, Deborah Meyer was the first female swimmer to win three gold medals in individual events at the Olympics. She was just 16 years old when she set world records in the 200, 400, and 800 meter events.. She won gold in all three. The effort required to continue to perform at that level was immense and she decided to retire at 19.

Perhaps the most iconic champion of women’s sports in the late twentieth century was Billie Jean King. King is celebrated as one of the greatest tennis players of all time. She was inducted into the International Tennis Hall of Fame in 1987 and received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Barack Obama in 2009..

King's most famous match, the 1973 "Battle of the Sexes," saw her defeat former men's champion Bobby Riggs in front of 30,492 spectators and millions of TV viewers worldwide. Riggs, who had previously defeated Margaret Court, boasted that no female player could beat him, but King proved him wrong with a decisive 6–4, 6–3, 6–3 victory. This match was pivotal in changing perceptions about women's tennis and in advancing gender equality in sports. King remarked that the victory was not just about beating Riggs but about exposing new audiences to tennis and uplifting women's self-esteem.

Beyond her on-court success, King was a tireless advocate for gender equality in sports. She criticized the United States Lawn Tennis Association's "shamateurism" and campaigned for equal prize money, leading to the US Open becoming the first major tournament to offer equal prizes for men and women in 1973. King also co-founded the Women's Tennis Association and the Women's Sports Foundation, promoting women's professional tennis and advocating for Title IX legislation. Her efforts have left an indelible mark on sports and feminism, creating greater opportunities for women everywhere.

Runner Kathrine Switzer attacked by race official Jock Semple while running in the 1967 Boston Marathon, Public Domain

Title IX in Sports and Education

Women’s rights ran parallel to another important movement of the period, women’s equal access to educational opportunities, which obviously helped women’s rights tremendously. With equal access to education, women were more empowered, and therefore women sought more leadership roles.

Patsy Mink, an Asian-American member of the U.S. House of Representatives, co-authored and sponsored the Title IX legislation, officially known as the Education Amendments of 1972. Title IX prevented discrimination on the basis of sex in schools receiving public funding. This legislation was interpreted to protect girls from sexual harassment and discrimination. It ensured that if an opportunity existed for boys, it could exist for girls too.

Congress member Patsy Mink was a strong advocate for gender equality and worked tirelessly to eliminate gender-based discrimination in education. Patsy Mink's personal experiences and her commitment to equal opportunity for women in education fueled her dedication to this cause.

Title IX, in its early years, had the largest impact on girls and women’s sports in high school and college, which had often been viewed as an afterthought. Girls teams were often given the boys hand-me-down uniforms and equipment and received little, if any funding. In one case, a girls basketball game was canceled mid game so the boys team could practice. To add insult to injury, at the University of Michigan, dogs were allowed in the stadium, but not girls sports fans, so the notion that girls might one day be the featured athletic talent was a distant dream.

Title IX required schools treat boys and girls equally: so sports teams needed to be funded equally. If the boys soccer team got X dollars, the girls team should get X dollars. This of course meant major changes in how schools budgeted for their sports teams and the mostly male coaches and administrators were not thrilled. Battles over Title IX erupted in schools and courts around the country.

In 1976, 19 college athletes from Yale

protested the unfair treatment of women in sports. The women's rowing team faced inequalities and lacked facilities, including locker rooms, bathrooms, and an equipment manager. The athletes stripped their uniforms to reveal "Title IX" written on their bodies, drawing attention to the landmark legislation. They wanted to address the violations of Title IX, as the university neglected their needs while providing better facilities for male athletes. The protest highlighted gender disparities and demanded equal treatment for women in sports.

In the 1980s, Debra Thomas made history as the first African American to earn a figure skating medal at the Winter Olympics, breaking significant racial barriers. Joan Campbell also blazed trails as the first Black woman to win a ladies' event at the U.S. Figure Skating Championships, while Tiffany Chin became the first Asian American ladies' champion in 1985. By the 1990s, figure skating had entered a golden age, marked by American dominance. The 1991 World Championships saw an iconic podium sweep by Kristi Yamaguchi, Tonya Harding, and Nancy Kerrigan, signaling a decade of U.S. success. Rising stars like Michelle Kwan and Tara Lipinski followed, with Kwan earning her first title in 1996 and Lipinski becoming the youngest champion at just 14.

This era also brought major milestones and controversies. Claire Ferguson became the first woman to serve as president of U.S. Figure Skating, and the organization secured a record-breaking broadcast deal with ABC. Tonya Harding made history in 1991 as the first woman to land a triple axel in competition but became embroiled in scandal after Nancy Kerrigan was attacked by an assailant linked to Harding's associates. Harding pleaded guilty to hindering the investigation and faced probation, fines, and a lifetime ban from amateur skating.

Despite the controversy, the sport flourished, with figures like Michelle Kwan solidifying their legacies as icons of American figure skating.

From the establishment of the WNBA women’s basketball has continually gained traction. The 1996 U.S. Women’s Olympic Basketball Team’s dominance helped launch the WNBA, while coaches like Tara VanDerveer have redefined success, surpassing even legendary men’s coaches in career wins. Trailblazers like Sheryl Swoopes, the first player signed to the WNBA, and modern figures like Sue Bird have not only elevated the game but also challenged norms around gender and sexuality. Flo Jo’s influence in style and design lives on in the sport, as athletes increasingly assert their individuality both on and off the court.

At the 1996 Atlanta Olympics, the U.S. women's gymnastics team, dubbed the "Magnificent 7," secured a historic gold medal. In the team competition, each gymnast performed two vaults, with only the higher score counting. The team, led by Phelps, Chow, Miller, and Dawes, had a narrow lead heading into Moceanu's vault. However, Moceanu’s under-rotated attempts earned her a 9.200, leaving the outcome uncertain, as the Russian team could still secure the gold with strong performances. Strug, who had injured her ankle, needed to vault again to secure the win. Despite the injury, she performed a near-perfect vault, earning a 9.712 and securing the gold, though she collapsed in pain afterward. Her heroic vault became one of the defining moments of the Games.

Strug’s injury did not stop her from joining her teammates for the medal ceremony, despite being rushed to a hospital tent afterward. Karolyi, determined not to let her miss the ceremony, carried her to the podium, where Miller and Moceanu helped lift Strug in a display of solidarity. While Strug was unable to compete in subsequent events due to her injury, her vault not only secured the team gold but also earned her a place in the vault finals, which she could not attend. Miller had the highest score of the competition, but Strug's final vault, combined with her resilience, became an iconic moment in Olympic history.

Women’s ice hockey has made significant strides in visibility and recognition. Cami Granato’s leadership of Team USA to its first Olympic gold medal in 1998 and her induction into the Hockey Hall of Fame as its first female member mark key milestones. These achievements have helped to dismantle gender barriers in a sport traditionally dominated by men, inspiring a new generation of women players to take the ice.

The U.S. Women’s National Soccer Team (USWNT) has set records for viewership and inspired millions. Iconic moments like Brandi Chastain’s winning penalty kick in the 1999 World Cup and Mia Hamm’s prolific career established women’s soccer as a force. Players such as Abby Wambach, Megan Rapinoe, Alex Morgan, and Carli Lloyd have further cemented the team’s legacy through Olympic and World Cup victories.

The USWNT’s fight for equal pay and visibility reflects broader societal shifts. As other nations catch up to the US’s dominance, global competition strengthens the sport, benefiting women’s soccer as a whole.

As a result of Title IX, women and girls gained greater access to athletic scholarships, improved facilities, and increased participation in sports, fostering personal growth, health, and empowerment.

But while Title IX made headlines for sports, probably the most significant impact was curbing discrimination that had long term impacts on women’s future careers and lives. In schools girls had been segregated into classes that taught them the skills of a housekeeper, while boys learned the skills of a trade or prepared them for college academics. Girls who took those courses were often the only ones in the room and faced harassment from the teachers and students alike.

Patsy Mink, Public Domain

Chris Ernst, Public Domain

Ruth Bader Ginsburg

In the late 1950s, a professor at Harvard Law School looked out at the first year class and made all the women stand and explain why they were taking a spot in the class from a man. Ruth Bader Ginsburg, a future Supreme Court Justice, was in one of those classes. She soon left Harvard for Columbia.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg's journey through law was marked by a relentless fight for gender equality and justice, deeply shaped by the discrimination she faced early in her career. After graduating from Columbia Law School, where she earned her LL.B., Ginsburg struggled to secure a job at a law firm in New York despite her top grades. This challenge led her to become a professor at Rutgers and later at Columbia Law School, where she found the space to push for change. Ginsburg's entire legal career was devoted to reforming the legal system from within, advocating for women and minorities by arguing cases that challenged systemic discrimination. She believed in changing the law, not by invalidating laws, but by ensuring they applied equally to all, regardless of gender.

One of her earliest and most significant cases, known as the "mother brief," involved Charles Moritz, a Colorado man who was denied a tax deduction for caring for his elderly mother because the law only allowed such deductions for women or divorced or widowed men. Ginsburg, alongside her husband Marty, a tax lawyer, took on the case. Instead of asking the court to invalidate the statute, she argued for its equal application to men, ultimately winning the case in the lower courts. This success marked the beginning of her career as a fierce advocate for women's rights. Over the next decade, Ginsburg would litigate and win several cases, including Reed v. Reed (1971), where she argued against a law that automatically preferred men over women as executors of estates, and Weinberger v. Wiesenfeld (1975), which challenged gender discrimination in Social Security benefits. Ginsburg's strategic, careful approach to cases emphasized practical change, often choosing male plaintiffs to demonstrate how gender discrimination harmed men as well. Her legal philosophy, centered on the belief that the 14th Amendment's equal protection clause applied to both men and women, eventually won the support of the U.S. Supreme Court.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg 2016, Public Domain

Harassment Cases

Several Supreme Court cases protected students from harassment by their peers and teachers. In the 1999 case, Davis v. Monroe County Board of Education, the Supreme Court clarified the rules for holding schools responsible for student-on-student sexual harassment under Title IX. The case involved a fifth-grade student named LaShonda Davis, who was sexually harassed by another student. Despite LaShonda's complaints, the school did not take action. Her parents sued the school board, claiming that the school had violated Title IX.

The Court decided that a school district can be held responsible for student-on-student sexual harassment if they knew about it and did nothing and if the harassment was severe, widespread, and the creator of an unfriendly environment that affected the victim's education. This ruling stated that schools must address and prevent sexual harassment between students to ensure a safe learning environment.

Another case protected students from teacher harassment. In Gebser v. Lago Vista Independent School District the Supreme Court dealt with the issue of liability for sexual harassment by a school employee under Title IX. Alida Star Gebser, a student, had a sexual relationship with a teacher at Lago Vista High School. Gebser and her mother sued the school district, claiming that the school knew about the teacher's misconduct but did not take appropriate action. The Supreme Court decided that a school district can be held responsible for sexual harassment by a teacher under Title IX if district officials had actual knowledge of the harassment and ignored it.

Title IX gave women a chance at equal opportunities in school. Girls learned how to be leaders through their engagement in sports and have surpassed men in college graduation rates.

The Equal Rights Amendment

Outside of the classroom, women fought for labor protections, childcare, maternity leave, and greater representation in all fields, especially government. Decades before, in 1923 Alice Paul and the National Women’s Party proposed the Equal Rights Amendment. The ERA was intended to remove all legal barriers to women’s equality. The NWP believed the amendment would cost less than state by state legislative challenges and bring permanent equality to women in the country by enshrining the concept in the Constitution. The ERA was introduced in every session of Congress but failed to pass in committee. In the 1940s, both the Republican and Democratic parties endorsed the ERA in their platforms. Despite the support, the ERA failed to move forward with many women’s organizations in opposition because of the assumption that the law would invalidate protective labor laws they fought for during the Progressive Era.

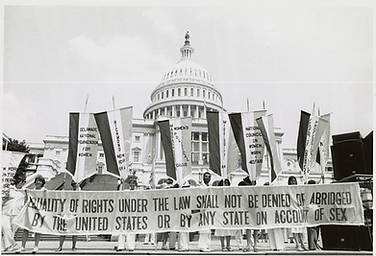

By the 1970s, ERA supporters convinced Democratic Senator Birch Bayh (IN) to hold hearings on the amendment in the Senate. At about the same time, Representative Martha Griffiths filed a motion to discharge the ERA from the House Judiciary Committee. During debate over the amendment, women presented evidence as to the necessity of a Constitutional amendment. They claimed sex discrimination was still more the rule than the exception in America. For example, in some states height requirements for police forces were set to exclude women and in other states public assistance programs provided less food for women claiming they needed less to survive. Congress also learned that college admissions practices discriminated against women. In 1972, almost 50 years after it was first introduced, Congress passed the Equal Rights Amendment reading “Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex.” According to the Constitution, a proposed amendment must be ratified by three-fourth of the states. Congress set a seven year deadline for ratification of the ERA.

Within the first year, twenty-two states had ratified the ERA and eight more followed in 1973. Supporters believed the amendment would quickly become a part of the U.S. Constitution. However, they underestimated the opposition and failed to develop a strategy to combat opposing arguments. The leader of the opposition was a conservative from Illinois, Phyllis Schlafly. She used her nationwide newsletter, The Eagle Forum, to campaign against the ERA and create an opposition organization, STOP ERA, meaning Stop Taking Our Privileges. She and members of the organization testified against the ERA in states that had not yet ratified the amendment..

Opponents contended the amendment was unnecessary because women’s rights were already protected. They pointed to the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth amendment, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the variety of recent legislation as evidence. Opponents argued that women could use the existing laws to challenge discrimination in the courts.

The opposition focused much of the debate on how the ERA would erode traditional family values and have negative unintended consequences. Schlafly said that trying to achieve women’s goals through the ERA was “like trying to kill a fly with a sledgehammer. You won’t kill the fly, but you surely will break up some of the furniture.” Opponents argued that women had special privileges due to their gender that the ERA would eliminate. They claimed the ERA would require women to contribute equally to the family’s income. Therefore, they claimed the amendment would force women into the workforce and take away their choice to be a homemaker. Opponents also contended that ERA would erode states’ rights and destroy the traditional family structure in America. It would take issues related to the sexes and the family out of state control. The amendment would invalidate state laws related to such things as divorce, child custody, alimony and inheritance.

The ERA, opponents maintained, would have broader impacts on society as well. Women would be drafted and sent into combat where they would have to perform tasks they were not able to handle to the detriment of America’s security. They also claimed the ERA would lead to sexual sameness and lead to unisex restrooms and an end to gender specific organizations like the Boy Scouts. Opponents also asserted the ERA would promote homosexuality and legalize same sex marriages. The amendment, according to opponents, would lead to societal chaos.

ERA opponents successfully shifted much of the debate on the law away from the constitutional principles to the claim that the amendment would create radical change to American society. Supporters continued to demonstrate the need for the amendment.

The Fourteenth amendment was not adequate protection for women, supporters declared. They pointed to the many instances of discrimination against women since the Fourteenth amendment’s passage. For example, if the due process and equal protection clauses found in the Fourteenth truly protected women’s rights, then the Nineteenth amendment, guaranteeing women the right to vote, would not have been necessary. Federal laws, supporters pointed out, were full of loopholes, subject to change, and not comprehensive. Proponents also said that courts routinely did not interpret the Fourteenth amendment in ways that truly protected women. Fighting discrimination on a case by case basis was expensive and time consuming. The ERA was needed to enshrine women’s rights fully into the Constitution and end continued discriminatory practices found across the country. Passage of ERA would send a clear message that the nation was committed to its core value, equality for all.

Constitutional and legal scholars concluded the ERA would not hurt states’ rights and that the amendment did not prevent legislation that makes distinctions between physical characteristics. While supporters conceded the ERA would make women eligible for the draft, they argued this was a positive consequence since it would increase opportunities for women in the armed services. Current restrictions based on sex hurt a woman’s chance of reaching the rank of general and the ERA would open jobs such as pilots, navigators, and flight engineers which had been closed to women. Supporters said if women expected the same rights as men, they must be willing to take on the responsibility of defending the country.

Supporters asserted the amendment would not radically change the American family structure. They said the protection of women as wives and mothers depended on mutual affection between men and women and not the law. The ERA, proponents argued, would not force women into the workforce but actually help recognize the contributions made by women in the home as well as in jobs outside the home..

By 1977, only thirty five states had ratified the ERA, leaving it three states short of the necessary three-fourths to become a part of the Constitution. The original congressional deadline was set to expire in March 1979. Arguing that the ERA was still being actively debated in the states, Congress granted a three year extension until 1982. As long as there were vocal opponents to the ERA, especially large groups of women, state legislators felt confident in voting against it. Therefore, despite the extension, the Equal Rights Amendment fell three states short of the thirty-eight states needed to become a part of the U.S. Constitution.

Opponents of the amendment celebrated while proponents attempted to regroup and devise a new plan of action. NOW promised to work toward defeating anti-ERA legislators across the country. The fight for the ERA had held together the women’s movement for a time, but with its defeat, the women’s liberation movement lost momentum and gradually declined. Groups fragmented while continuing to fight for various women’s rights.

Phyllis Schafly protesting in front of the White House, Public Domain

Opposition to ERA in front of the White House, Public Domain

March for ERA in Washington D.C. 1978, Public Domain

Electoral Politics

Women lacked adequate representation in government. In 1962, there were only 2 women in the U.S. Senate and 18 women members of the House of Representatives. Hattie Caraway and Margaret Chase Smith were the first women Senators, but by 1962, their progress had not cleared the way for more women. Caraway of Arkansas became the first woman to win election to the Senate in 1932 and 1949 Margaret Chase Smith of Maine followed her, becoming the first woman to serve in both the U.S. House of Representatives and the Senate. Only 2 women had ever served in the President’s cabinet and only 6 had served as foreign ministers or ambassadors. No woman had served on the Supreme Court and only 2 women were federal district judges. Across the country, there were over 7,000 elected state legislature positions, only 234 of which were held by women.

Women were needed wherever laws and decisions were made. The first women in political positions sometimes got there by association with their husbands in power. Natalie Tayloe Ross won a special election to fill a vacancy caused by the death of her husband as Governor of Wyoming. Inaugurated fifteen days before Miriam Ferguson of Texas, Ross was the first woman sworn in as a US governor in 1925. Ferguson too was elected twice as a surrogate for her husband who could not run for re-election. In Alabama, Lurleen Wallace was also elected as a surrogate for her husband. In 1975, Ella T. Grasso was elected in her own right in Connecticut.

Women also found places in the Senate and House of Representatives in larger numbers.

Bella Abzug served in the House of Representatives from 1971-1977. She was called “Battling Bella” because of her unwavering support for civil rights, gay rights, and women’s rights. She often said, “A woman’ place is in the house–the House of Representatives.”

Margaret Chase Smith from Maine became the first woman elected to the Senate. Although others preceded her she was the first woman elected, as others had been appointed to serve. Since she had previously served in the House, she was the first to do both.

Shirley Chisholm was the first African-American to serve in the House. She faced both gender and race based discrimination her entire career in politics. In 1972 she campaigned for president during the Democratic primary. She was unfairly blocked from participating in televised debates by her male peers. She took legal action but was only permitted to make a single speech. Even though she was unsuccessful, Chisholm raised hope that a future woman might occupy the White House.

Jimmy Carter’s presidency marked a transformative era for gender equity in the United States. Elected in 1976, he championed the Equal Rights Amendment and set new benchmarks for representation by appointing an unprecedented number of women and people of color to the federal judiciary and executive branch. Notably, Carter appointed Patricia Roberts Harris as the first Black woman to serve in a presidential cabinet as the Secretary of Housing and Urban Development. Carter extended the ratification deadline for the Equal Rights Amendment. His administration also enacted key legislation like the Pregnancy Discrimination Act and ratified the UN’s Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, while creating a permanent office for the first lady, setting a precedent for future administrations.

In his post-presidency, Carter remained deeply committed to combating gender-based violence and discrimination globally. Through the Carter Center, he addressed systemic injustices such as trafficking, female genital mutilation, and gender inequity in over 145 countries. Carter’s advocacy extended to criticizing the Southern Baptist Convention for its subjugation of women, leading him to sever ties with the denomination while continuing to support women pastors in his local church.

But progress for women in politics would feel stagnant through the conservative era that followed. By 1980, 22 women served in the House of Representatives and 2 were in the Senate.

Hillary Clinton's appointment as head of the healthcare task force marked a significant deviation from traditional First Lady roles, symbolizing the administration's commitment to women’s leadership. However, her high-profile involvement and the task force’s secretive operations drew criticism and became a political liability. The healthcare reform effort ultimately failed, hindered by public backlash, Republican opposition, and internal missteps. Nevertheless, Hillary Clinton’s prominence in shaping policy underscored the administration’s broader emphasis on advancing women’s roles in public and political life.

Despite his administration’s advancements in women’s representation, Clinton’s presidency was marred by controversies involving women, including the Monica Lewinsky affair and sexual harassment allegations by Paula Jones. These scandals damaged Clinton’s personal reputation and drew widespread criticism, even as his approval ratings for job performance remained high. Hillary Clinton’s poised handling of these crises won her widespread admiration and bolstered her own public image. Together, the Clintons’ experiences reflected both progress and challenges in navigating the complexities of gender and leadership in modern American politics.

Further, his presidency enforced limited views of gender and sexuality. He signed the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) into law, which strictly defined marriage as between a man and a woman. He also introduced “Don’t Ask Don’t Tell” into the military. The policy was meant to be a compromise with those who wanted to outright man non-heterosexual people from the military. Yet, the policy led to more suspicion of queer people. The effect was particularly profound on lesbians, who were already facing uphill battles as women in the military.

Clinton’s legacy related to women and gender hasn’t aged well. As society moves beyond the peculiar politics of the time, his compromises are harder to appreciate and the many allegations of sexual harassment make him a complicated figure.

Shirley Chisholm, Public Domain

Conclusion

Title IX’s comprehensive approach to combating gender-based discrimination, promoting equal opportunity, and fostering inclusivity has had a profound and lasting impact on women's lives. It has not only expanded educational and athletic opportunities but has also challenged societal norms and advanced the pursuit of gender equality, making it widely recognized as a landmark piece of legislation of the 20th century.

The ERA continues to be introduced in Congress, and Illinois, Nevada, and Virginia all ratified the amendment in recent years. Some claim the time limit placed on the ratification was unconstitutional since the Article V of the Constitution which describes the amendment process does not include language about time limits. By this argument, with these three states, the ERA should become part of the Constitution. Critics say that the amendment is dead, and a recent appeals court decision refused to force the Archivist of the United States to certify the amendment. In order to become a part of the Constitution, the process must start again. The ERA would have to be voted on by Congress and then sent to the states again for ratification.

Despite the failure of the ERA, the fight for it helped to ativate women across the country. Women, on both sides of the issue, wrote letters, visited legislators, and protested in support of their cause. They learned how to lobby for important issues and the importance of electing supportive officials. Women took on a much more active role in politics due to the fight for the Equal Rights Amendment.

By the end of this era, so much remained in question. Would the ERA ever be fully ratified? Was it good for women? What would be the lasting effects of the feminist movement?