1. Early North American Women

|

Native Americans had distinct and diverse cultures across North America. The communities varied depending on their environment and the traditions that developed there. Distinct gender norms developed as well. Much is known about these gender norms and the lives of women before European contact.

|

|

Public Domain

Public Domain

Before the US was the US, the land was home to numerous Native American nations whose diversity, then and now, rivals that of Eurasia. Each of the hundreds of nations have, and had, their own language, religion, customs, governance structure, judicial system, and history. The role of women in Native culture is as complex and different as the nations from which they emerged.

Like most cultures, so much depended on where the nation was located and the particular needs of that geography, and environment dictated the various roles people within that society played. Northwestern nations lived on rivers and relied on fishing, while those on the plains followed buffalo and planted corn for their livelihood. While gender usually plays a role in determining responsibilities, gender did not limit women in many Native cultures.

Investigating the lives of women native to North America is deeply challenging because the experiences of Indigenous people varied from region to region, community to community, and even within communities. Native people are diverse, their societies rich, complex, and enduring. Gender was, however, significant in the lives of early Native peoples wherever they were.

Like most cultures, so much depended on where the nation was located and the particular needs of that geography, and environment dictated the various roles people within that society played. Northwestern nations lived on rivers and relied on fishing, while those on the plains followed buffalo and planted corn for their livelihood. While gender usually plays a role in determining responsibilities, gender did not limit women in many Native cultures.

Investigating the lives of women native to North America is deeply challenging because the experiences of Indigenous people varied from region to region, community to community, and even within communities. Native people are diverse, their societies rich, complex, and enduring. Gender was, however, significant in the lives of early Native peoples wherever they were.

Public Domain

Public Domain

Family and community systems brought Native people together through mutual reliance and respect. As in many places and cultures, men were generally responsible for hunting, warfare, and interacting with outsiders, therefore they had more visible roles. This is why the names of male Natives tend to be more visible in our histories.

Role in Governance:

Native women were active in community governance and activities. Many nations, perhaps one-fourth if not a majority, were organized matrilineally, where husbands would come to live with the wife’s family and inheritance was passed down from the mother.

In matrilineal societies, women owned the family’s home and goods. They did all the agricultural production and reared children. They also held political and economic power.

The Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy, or the Haudenosaunee (hoe-deh-no-SHOW-nee) were all led matrilineally– with women at the helm. Clan leaders selected a male chief to represent the nation and they removed them when the women were dissatisfied with their leadership.

In other nations, women would even become warriors. Some were able to earn the title of chief because of their own achievements on the battlefield or due to their husband’s death. In the midwest, women often helped hunt and harvest buffalo, and were responsible for utilizing the entirety of the animal. In these communities the relationship between gender and service to the nation was much less significant.

Gender Norms:

In other communities, however, gender determined many of the expectations about what contributions to the community a person would make. For example, the Cherokee of the Southeast assigned male and female infants a bow or a sifter at birth to connect them to their future lives as hunters and fishers or agricultural production. The Iroquois of the Northeast, also known as the Haudenosaunee classified the forest as male and the village as female.

Role in Governance:

Native women were active in community governance and activities. Many nations, perhaps one-fourth if not a majority, were organized matrilineally, where husbands would come to live with the wife’s family and inheritance was passed down from the mother.

In matrilineal societies, women owned the family’s home and goods. They did all the agricultural production and reared children. They also held political and economic power.

The Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy, or the Haudenosaunee (hoe-deh-no-SHOW-nee) were all led matrilineally– with women at the helm. Clan leaders selected a male chief to represent the nation and they removed them when the women were dissatisfied with their leadership.

In other nations, women would even become warriors. Some were able to earn the title of chief because of their own achievements on the battlefield or due to their husband’s death. In the midwest, women often helped hunt and harvest buffalo, and were responsible for utilizing the entirety of the animal. In these communities the relationship between gender and service to the nation was much less significant.

Gender Norms:

In other communities, however, gender determined many of the expectations about what contributions to the community a person would make. For example, the Cherokee of the Southeast assigned male and female infants a bow or a sifter at birth to connect them to their future lives as hunters and fishers or agricultural production. The Iroquois of the Northeast, also known as the Haudenosaunee classified the forest as male and the village as female.

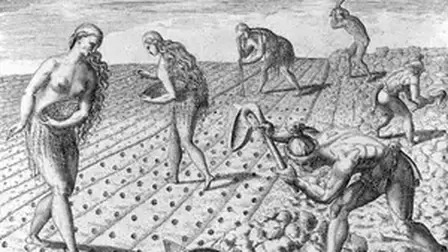

European sketches showing indigenous women farming, Library of Congress

European sketches showing indigenous women farming, Library of Congress

But for Indigenous people, gender wasn’t always strictly binary. For example, Dine and Navajo recognized six different genders. The Ojibwe did have male and female roles, but individuals could align with the gender of their choice.

Despite the birth rituals, the Cherokee also allowed for gender variance and even built it into their language. A variety of words in the Cherokee language describe people who are “Two-Spirit” or whose gender expression or identity fits outside the binary male or female. There are words that translate to “he or she thinks like a man or woman.”

In most Native communities, women had significant spiritual roles. They often served as spiritual leaders, healers, and in political leadership. In many Native American creation stories, one of the female characters created life, nature, and Earth through their body through some sort of birth.

The Pueblo of the Southwest have a fascinating origin story where the Corn Mother gave birth to human life and corn sprouted up through the ground. All babies were given an ear of corn at birth to recognize this sacred connection to the Mother. This story illustrates the centrality of the feminine to Pueblo life.

The belief in women’s inherent spirituality lended to their role as healers. Many nations believed that women had more healing power. Women had extensive knowledge of plants and medicines for healing and were vital to the nation's success. Most Native American women were master craftspeople producing blankets, baskets, jewelry and pottery. Because women work– and always have.

Despite the birth rituals, the Cherokee also allowed for gender variance and even built it into their language. A variety of words in the Cherokee language describe people who are “Two-Spirit” or whose gender expression or identity fits outside the binary male or female. There are words that translate to “he or she thinks like a man or woman.”

In most Native communities, women had significant spiritual roles. They often served as spiritual leaders, healers, and in political leadership. In many Native American creation stories, one of the female characters created life, nature, and Earth through their body through some sort of birth.

The Pueblo of the Southwest have a fascinating origin story where the Corn Mother gave birth to human life and corn sprouted up through the ground. All babies were given an ear of corn at birth to recognize this sacred connection to the Mother. This story illustrates the centrality of the feminine to Pueblo life.

The belief in women’s inherent spirituality lended to their role as healers. Many nations believed that women had more healing power. Women had extensive knowledge of plants and medicines for healing and were vital to the nation's success. Most Native American women were master craftspeople producing blankets, baskets, jewelry and pottery. Because women work– and always have.

European sketches of indigenous mothers, Library of Congress

European sketches of indigenous mothers, Library of Congress

Marriage and Sexual Freedoms:

Marriage and sexual activity in Native communities was extremely varied. Sex was not necessarily reserved for only marriage, and sex often began at a young age. Some nations were polygamous– meaning people had multiple partners in their lifetime or at the same time– a practice still in place in some Mormon and Muslim families today. Some nations had formal marriage ceremonies, while others considered a couple married when they began living together.

Women’s power in relationships and within the nation showed most notably in divorce. Both men and women could decide to end a marriage or relationship, but in many nations, women owned all the household belongings, so men leaving marriages could only take the items they had when they began the relationship. Unlike the patriarchal societies of Eurasia where fathers owned their children and mothers had little rights to them, children in Native societies often belonged exclusively to their mother. When a widow remarried, her children from the prior marriage would be adopted by the new husband.

Native cultures had different practices around menstruation. In some, women inhabited separate quarters during menstruation. For the Ojibwe, women were considered most powerful during that time of the month. Generally, most cultures celebrated female puberty, rather than shamed it. The Hupa people, for instance, celebrate a 3-10 day coming-of-age ceremony following the first menstruation.

Some nations would not allow a couple to have sex until their child reached a certain age, although this practice varied considerably from the child’s ability to crawl to closer to ten years, as practiced by the Cheyenne. As a result, Native American families had about three children, while Eurasian families would sometimes have up to fourteen children.

Native women did what the later Europeans considered “men’s work.” But Native Americans believed in equality, fairness, and autonomy– novel concepts. Most scholars agree that Native American women had more authority and independence than their European counterparts.

Marriage and sexual activity in Native communities was extremely varied. Sex was not necessarily reserved for only marriage, and sex often began at a young age. Some nations were polygamous– meaning people had multiple partners in their lifetime or at the same time– a practice still in place in some Mormon and Muslim families today. Some nations had formal marriage ceremonies, while others considered a couple married when they began living together.

Women’s power in relationships and within the nation showed most notably in divorce. Both men and women could decide to end a marriage or relationship, but in many nations, women owned all the household belongings, so men leaving marriages could only take the items they had when they began the relationship. Unlike the patriarchal societies of Eurasia where fathers owned their children and mothers had little rights to them, children in Native societies often belonged exclusively to their mother. When a widow remarried, her children from the prior marriage would be adopted by the new husband.

Native cultures had different practices around menstruation. In some, women inhabited separate quarters during menstruation. For the Ojibwe, women were considered most powerful during that time of the month. Generally, most cultures celebrated female puberty, rather than shamed it. The Hupa people, for instance, celebrate a 3-10 day coming-of-age ceremony following the first menstruation.

Some nations would not allow a couple to have sex until their child reached a certain age, although this practice varied considerably from the child’s ability to crawl to closer to ten years, as practiced by the Cheyenne. As a result, Native American families had about three children, while Eurasian families would sometimes have up to fourteen children.

Native women did what the later Europeans considered “men’s work.” But Native Americans believed in equality, fairness, and autonomy– novel concepts. Most scholars agree that Native American women had more authority and independence than their European counterparts.

19th Century sketch of an Indigenous woman, Library of Congress

19th Century sketch of an Indigenous woman, Library of Congress

Property Ownership:

The importance of property ownership depended on where the nation was located and what natural resources the nation used to sustain itself.

In the Pacific Northwest, trees and acorns were incredibly important to the community’s diet, so ownership of trees was passed down from mother to daughter.

In the east, some Native nations placed emphasis on actual land ownership, and unsurprisingly, women often owned the land. The Algonquin and other North Central nations used markers, like Eurasians, to show where one family’s property began and ended.

Other nations, like the Lenape, thought of ownership more like leasing, where someone had the right to use the land, but that it belonged to the nation as a whole. To the Iroquois, or Haudenosaunee , women owned the fields they worked, the longhouses, and everything in them. The Hopi women owned the pueblos and the land which was inherited matrilineally.

One early Native source said, “You ought to hear and listen to what we women shall speak . . . for we are the owners of this land and it is ours.” Native Americans women engaged in agricultural activity for generations prior to European contact.

The importance of property ownership depended on where the nation was located and what natural resources the nation used to sustain itself.

In the Pacific Northwest, trees and acorns were incredibly important to the community’s diet, so ownership of trees was passed down from mother to daughter.

In the east, some Native nations placed emphasis on actual land ownership, and unsurprisingly, women often owned the land. The Algonquin and other North Central nations used markers, like Eurasians, to show where one family’s property began and ended.

Other nations, like the Lenape, thought of ownership more like leasing, where someone had the right to use the land, but that it belonged to the nation as a whole. To the Iroquois, or Haudenosaunee , women owned the fields they worked, the longhouses, and everything in them. The Hopi women owned the pueblos and the land which was inherited matrilineally.

One early Native source said, “You ought to hear and listen to what we women shall speak . . . for we are the owners of this land and it is ours.” Native Americans women engaged in agricultural activity for generations prior to European contact.

Plains Natives, Public Domain

Plains Natives, Public Domain

On the Great Plains, where buffalo were essential and nations migrated to follow them, inheritance rules put emphasis on objects that people moved with them. When these nations, like the Lakota and the Pawnee got horses brought from Europe, they became the predominant source of wealth. Everyone, even children, had the right to own horses.

Domesticating animals other than horses was rare in Native cultures because they tended to believe that animals had equal spiritual rights as humans and because it disrupted gendered distributions of labor.

We have few reliable written sources about Native women’s lives before contact with Europeans, so unfortunately we have to turn to white men’s interpretations of Natives for some of our sources. In 1644, the Rev. John Megalopensis, minister at a Dutch Church in New Netherlands (modern day New York) said that Native American women were, “obliged to prepare the Land, to mow, to plant, and do everything; the Men do nothing except hunting, fishing, and going to War against their Enemies. . .” Others described Native women as “slaves'' to the men. These European observers were describing and defining the actions of indigenous people, but filtered through their own lens. Specifically, these white men were witnessing what they saw as abberations to idealized European gender roles. Some historians have argued that these observations contributed to the racialization of native peoples as “savage” or uncivilized–because their gendered division did not mirror Europeans’ gendered division of labor. The reality was that these European writers didn’t really understand, or care to understand, the way Natives shared the burden of labor.

European Arrival:

After the arrival of more European explorers, 90 to 95 percent of the Indigenous population was wiped out by diseases. Territorial disputes and the resulting conflicts also had devastating impacts on the already weakened Native populations.

Scholars disagree on how European expansion and migration impacted Native women. Some argue that, after contact, women’s authority declined because of a term called “cultural assimilation”– where cultures shift and change to become similar to the dominant culture. White men preferred to deal with Native men in trade and political negotiations, despite women sitting at the helm in most Native communities. White Christian leaders demanded of their Native converts that they follow patriarchal norms and European gender norms.

Domesticating animals other than horses was rare in Native cultures because they tended to believe that animals had equal spiritual rights as humans and because it disrupted gendered distributions of labor.

We have few reliable written sources about Native women’s lives before contact with Europeans, so unfortunately we have to turn to white men’s interpretations of Natives for some of our sources. In 1644, the Rev. John Megalopensis, minister at a Dutch Church in New Netherlands (modern day New York) said that Native American women were, “obliged to prepare the Land, to mow, to plant, and do everything; the Men do nothing except hunting, fishing, and going to War against their Enemies. . .” Others described Native women as “slaves'' to the men. These European observers were describing and defining the actions of indigenous people, but filtered through their own lens. Specifically, these white men were witnessing what they saw as abberations to idealized European gender roles. Some historians have argued that these observations contributed to the racialization of native peoples as “savage” or uncivilized–because their gendered division did not mirror Europeans’ gendered division of labor. The reality was that these European writers didn’t really understand, or care to understand, the way Natives shared the burden of labor.

European Arrival:

After the arrival of more European explorers, 90 to 95 percent of the Indigenous population was wiped out by diseases. Territorial disputes and the resulting conflicts also had devastating impacts on the already weakened Native populations.

Scholars disagree on how European expansion and migration impacted Native women. Some argue that, after contact, women’s authority declined because of a term called “cultural assimilation”– where cultures shift and change to become similar to the dominant culture. White men preferred to deal with Native men in trade and political negotiations, despite women sitting at the helm in most Native communities. White Christian leaders demanded of their Native converts that they follow patriarchal norms and European gender norms.

Motherhood, Wikimedia Commons

Motherhood, Wikimedia Commons

And while that may be true in some places, other scholars insist that women’s leadership remained central to other societies. Matrilineal inheritance of clan identity remained important to many communities, as evidenced by women’s central role in those communities long after European contact and today.

For example, in 1787, a Cherokee woman appealed to Benjamin Franklin on behalf of her community. She said, “. . . ought to mind what a woman says, and look upon her as a mother – and I have Taken the prevelage to Speak to you as my own Children . . . and I am in hopes that you have a beloved woman amongst you who will help to put her children right if they do wrong, as I shall do the same. . . . ”

Later in the 1800s when the Cherokee nation was increasingly forced out of their homes, groups of Cherokee women petitioned their Council to stand their ground. They forcefully stated, “[b]eloved children… God gave us to inhabit and raise provisions… [do not] part with any more lands.”

These quotes give merit to the suggestion that women’s roles remained and remain central to the leadership of at least some Native communities.

By the end of this era, so much remained in question. How would these rich cultures continue? What would happen to the Native people that survived European arrival and what role would women play in that survival? What efforts would be made to resist European expansion? And how many would assimilate to European norms and culture?

For example, in 1787, a Cherokee woman appealed to Benjamin Franklin on behalf of her community. She said, “. . . ought to mind what a woman says, and look upon her as a mother – and I have Taken the prevelage to Speak to you as my own Children . . . and I am in hopes that you have a beloved woman amongst you who will help to put her children right if they do wrong, as I shall do the same. . . . ”

Later in the 1800s when the Cherokee nation was increasingly forced out of their homes, groups of Cherokee women petitioned their Council to stand their ground. They forcefully stated, “[b]eloved children… God gave us to inhabit and raise provisions… [do not] part with any more lands.”

These quotes give merit to the suggestion that women’s roles remained and remain central to the leadership of at least some Native communities.

By the end of this era, so much remained in question. How would these rich cultures continue? What would happen to the Native people that survived European arrival and what role would women play in that survival? What efforts would be made to resist European expansion? And how many would assimilate to European norms and culture?

Draw your own conclusions

|

Learn how to teach with inquiry.

Many of these lesson plans were sponsored in part by the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources Eastern Region Program, coordinated by Waynesburg University, the History and Social Studies Education Faculty at Plymouth State University, and the Patrons of the Remedial Herstory Project. |

Lesson Plans from Other Organizations

- The National Women's History Museum has lesson plans on women's history.

- The Gilder Lehrman Institute for American History has lesson plans on women's history.

- The NY Historical Society has articles and classroom activities for teaching women's history.

- Unladylike 2020, in partnership with PBS, has primary sources to explore with students and outstanding videos on women from the Progressive era.

- The Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media has produced recommendations for teaching women's history with primary sources and provided a collection of sources for world history. Check them out!

- The Stanford History Education Group has a number of lesson plans about women in World History.

Period Specific Lesson Plans from Other Organizations

- Gilder Lehrman: The conclusion that encounters between European settlers and Native Americans changed the lives of both groups has been central to many historical accounts of colonial history. While the arguments made are convincing, the discussions do not directly address the lives of women. It is possible that this omission is a result of a paucity of sources. Regardless of the problems with sources, the question may still be asked: Does this assumption hold up when we look at the encounter of women of both cultures? If not, why not? Before we can consider questions such as these, we need to look at the available primary sources for seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century women and gather as much useful information as we can. Because there is not a wealth of primary sources available on the Internet on these women, we need to read what we do have carefully and learn as much as we can. Hopefully, this will enable us to analyze and write this history. In this lesson, students will use primary and secondary sources to research and understand the lives of women (both Native American and European) in North America in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

- NY Historical Society: Women were an integral part of the daily life and success of New Netherland. They served as translators between the Dutch government and the local Native tribes, and acted as liaisons during negotiations with enemy forces. Women were at the center of the colony’s struggle to define the terms of slavery and freedom for the black colonials who lived in the territory. Dutch women actively participated in the bustling trade in the colony, while Native women manipulated imperial power structures to ensure their own survival. And all women in New Netherland contributed to the survival of the colony while still carrying out the responsibilities of home and child care.

- NY Historical Society: The traditional role of women in English society was one of subordination or second-class status. Women were expected to answer to their fathers, their husbands, and their religious and political leaders. The English common law practice of coverture made it so married women did not legally or economically exist, so they could not be free. But women were hard at work affecting the colonies in many ways, from enslaved women bringing agricultural knowledge that made colonies flourish to housewives inventing new ways to perform basic tasks. Women took part in the armed resistance to European invasion, and challenged the gender norms they were forced to live under. The power of women was well recognized by English colonial governments, who made laws to govern their reproduction, tried them for heresy and witchcraft, and severely punished their crimes, even when the women themselves were not at fault. The very first published poet of the English colonies was a woman. Even though the odds were against them, the women of the early English colonies were important to the development of the New World.

James Adair: The History Of The American Indians

It has been long too feelingly known, that instead of observing the generous and hospitable part of the laws of war, and saving the unfortunate who fall into their power, that they generally devote their captives to death, with the most agonizing tortures. No representation can possibly be given, so shocking to humanity, as their unmerciful method of tormenting their devoted prisoner; and as it is so contrary to the standard of the rest of the known world, I shall relate the circumstances so far as to convey proper information thereof to the reader...

They are condemned, and tied to the dreadful stake, one at a time. The victors first strip their miserable captives quite naked... Then they know their doom—deep black, and burning fire, are fixed seals of their death-warrant. Their punishment is always left to the women... Each of [the women] prepares for the dreadful rejoicing, a long bundle of dry canes, or the heart of fat pitch-pine, and as the victims are led to the stake, the women and their young ones beat them with these in a most barbarous manner.

The women make a furious onset with their burning torches: his pain is so excruciating, that he rushes out from the pole... Then they pour over him a quantity of cold water, and allow him proper time of respite till his spirits recover, and he is capable of suffering new tortures... Now they scalp him... and carry off all the exterior branches of the body in shameful, and savage triumph.

This is the most favourable treatment their devoted captives receive: it would be too shocking to humanity either to give, or peruse, every particular of their conduct in such doleful tragedies— nothing can equal these scenes.

Adair, James. The History of the American Indians. United Kingdom: E. & C. Dilly, 1775.

Questions:

They are condemned, and tied to the dreadful stake, one at a time. The victors first strip their miserable captives quite naked... Then they know their doom—deep black, and burning fire, are fixed seals of their death-warrant. Their punishment is always left to the women... Each of [the women] prepares for the dreadful rejoicing, a long bundle of dry canes, or the heart of fat pitch-pine, and as the victims are led to the stake, the women and their young ones beat them with these in a most barbarous manner.

The women make a furious onset with their burning torches: his pain is so excruciating, that he rushes out from the pole... Then they pour over him a quantity of cold water, and allow him proper time of respite till his spirits recover, and he is capable of suffering new tortures... Now they scalp him... and carry off all the exterior branches of the body in shameful, and savage triumph.

This is the most favourable treatment their devoted captives receive: it would be too shocking to humanity either to give, or peruse, every particular of their conduct in such doleful tragedies— nothing can equal these scenes.

Adair, James. The History of the American Indians. United Kingdom: E. & C. Dilly, 1775.

Questions:

- Who wrote this "history" of the American Indians? Are they native?

- What biases may the author have?

- Why does Adair say that a slow, painful death is “the most favorable treatment their devoted captives receive”? Is this true? Why or why not?

Mrs. Johnson: Narrative Of Her Capture

In justice to the Indians, I ought to remark, that they never treated me with cruelty to a

wanton degree; few people have survived a situation like mine, and few have fallen into the

hands of savages disposed to more lenity and patience. Modesty has ever been a characteristic of

every savage tribe; a truth which my whole family will join to corroborate, to the extent of their

knowledge. As they are aptly called the children of nature, those who have profited by

refinement and education, ought to abate part of the prejudice, which prompts them to look with

an eye of censure on this untutored race. Can it be said of civilized conquerors, that they, in the

main, are willing to share with their prisoners, the last ration of food, when famine stares them

in the face? Do they ever adopt an enemy, and salute him by the tender name of brother? And I

am justified in doubting, whether if I had fallen into the hands of French soldiery, so much

assiduity would have been shewn to preserve my life.

Johnson, Mrs., John Curtis Chamberlain, and David Carlisle. A Narrative of the Captivity of Mrs. Johnson.: Containing an Account of Her Sufferings, During Four Years with the Indians and French. Published According to Act of Congress. Printed at Walpole, New Hampshire: by David Carlisle, Jun, 1796.

Questions:

wanton degree; few people have survived a situation like mine, and few have fallen into the

hands of savages disposed to more lenity and patience. Modesty has ever been a characteristic of

every savage tribe; a truth which my whole family will join to corroborate, to the extent of their

knowledge. As they are aptly called the children of nature, those who have profited by

refinement and education, ought to abate part of the prejudice, which prompts them to look with

an eye of censure on this untutored race. Can it be said of civilized conquerors, that they, in the

main, are willing to share with their prisoners, the last ration of food, when famine stares them

in the face? Do they ever adopt an enemy, and salute him by the tender name of brother? And I

am justified in doubting, whether if I had fallen into the hands of French soldiery, so much

assiduity would have been shewn to preserve my life.

Johnson, Mrs., John Curtis Chamberlain, and David Carlisle. A Narrative of the Captivity of Mrs. Johnson.: Containing an Account of Her Sufferings, During Four Years with the Indians and French. Published According to Act of Congress. Printed at Walpole, New Hampshire: by David Carlisle, Jun, 1796.

Questions:

- How does Mrs. Johnson describe her treatment under the Indians? Does she think she would be treated better by fellow Euro-Americans (like the French)?

- What bias may Mrs. Johnson have?

Mary Jemison: Memoir Of Her Life

It was my happy lot to be accepted for adoption; and at the time of the ceremony I was received by the two squaws, to supply the place of their brother in the family; and I was ever considered and treated by them as a real sister, the same as though I had been born of their mother.

During my adoption, I sat motionless, nearly terrified to death at the appearance and actions of the company, expecting every moment to feel their vengeance, and suffer death on the spot. I was, however, happily disappointed, when at the close of the ceremony the company retired, and my sisters went about employing every means for my consolation and comfort.

My sisters were diligent in teaching me their language; and to their great satisfaction I soon learned so that I could understand it readily, and speak it fluently. I was very fortunate in falling into their hands; for they were kind good natured women; peaceable and mild in their dispositions; temperate and decent in their habits, and very tender and gentle towards me.

Seaver, James E. A Narrative of the Life of Mrs. Mary Jemison .. New York: Corinth Books, 1961.

Questions:

During my adoption, I sat motionless, nearly terrified to death at the appearance and actions of the company, expecting every moment to feel their vengeance, and suffer death on the spot. I was, however, happily disappointed, when at the close of the ceremony the company retired, and my sisters went about employing every means for my consolation and comfort.

My sisters were diligent in teaching me their language; and to their great satisfaction I soon learned so that I could understand it readily, and speak it fluently. I was very fortunate in falling into their hands; for they were kind good natured women; peaceable and mild in their dispositions; temperate and decent in their habits, and very tender and gentle towards me.

Seaver, James E. A Narrative of the Life of Mrs. Mary Jemison .. New York: Corinth Books, 1961.

Questions:

- How does Mary Jemison describe her acceptance by and life among her adoptive family?

- Why might Mary be up for adoption? Who placed her up for adoption?

Benjamin Franklin: Letter To Peter Collinson

When white persons of either sex have been taken prisoners young by the Indians, and lived a while among them, tho’ ransomed by their Friends, and treated with all imaginable tenderness to prevail with them to stay among the English, yet in a Short time they become disgusted with our manner of life, and the care and pains that are necessary to support it, and take the first good Opportunity of escaping again into the Woods, from whence there is no reclaiming them.

Benjamin Franklin, “From Benjamin Franklin to Peter Collinson, 9 May 1753,” May 9, 1753, Founders Online, National Archives, Accessed 20 May 2022, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-04-02-0173.

Questions:

Benjamin Franklin, “From Benjamin Franklin to Peter Collinson, 9 May 1753,” May 9, 1753, Founders Online, National Archives, Accessed 20 May 2022, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-04-02-0173.

Questions:

- What does Benjamin Franklin say about captives who have been ransomed and returned to Euro-American society?

- Why might Euro-Americans, and specifically women, prefer to live among the Indians? Is this a problem for Euro-Americans? Why or why not?

- What does this say about Euro-American society?

Remedial Herstory Editors. "1. EARLY NORTH AMERICAN WOMEN." The Remedial Herstory Project. November 20, 2022. www.remedialherstory.com.

Primary AUTHOR: |

Kelsie Brook Eckert

|

Primary ReviewerS: |

Dr. Margaret Huettl

Hannah Dutton |

Consulting TeamKelsie Brook Eckert, Project Director

Coordinator of Social Studies Education at Plymouth State University Dr. Barbara Tischler, Consultant Professor of History Hunter College and Columbia University Dr. Alicia Gutierrez-Romine, Consultant Assistant Professor of History at La Sierra University Jacqui Nelson, Consultant Teaching Lecturer of Military History at Plymouth State University Dr. Deanna Beachley Professor of History and Women's Studies at College of Southern Nevada |

EditorsAlice Stanley

ReviewersColonial

Dr. Margaret Huettl Hannah Dutton Dr. John Krueckeberg 19th Century Dr. Rebecca Noel Michelle Stonis, MA Annabelle L. Blevins Pifer, MA Cony Marquez, PhD Candidate 20th Century Dr. Tanya Roth Dr. Jessica Frazier Mary Bezbatchenko, MA Dr. Alicia Gutierrez-Romine Matthew Cerjak |

|

American Indian women have traditionally played vital roles in social hierarchies at the family, clan, and tribal levels. In the Cherokee Nation, specifically, women and men are considered equal contributors to the culture. With this study, however, we learn that three key historical events in the 19th and early 20th centuries—removal, the Civil War, and allotment of their lands—forced a radical renegotiation of gender roles and relations in Cherokee society.

Roxanne Dunbar Ortiz tells a survey of indigenous people in the United States.

|

Weaving her own story with the story of her ancestors and with the broader themes of creation, replacement, and disappearance, Krawec helps readers see settler colonialism through the eyes of an Indigenous writer. Settler colonialism tried to force us into one particular way of living, but the old ways of kinship can help us imagine a different future.

|

A collection of historical and contemporary women of Indigenous heritage who have contributed to the survival and success of their families, communities--and the United States of America.

|

|

Based on an Athabascan Indian legend passed along for many generations from mothers to daughters of the upper Yukon River Valley in Alaska, this is the suspenseful, shocking, ultimately inspirational tale of two old women abandoned by their tribe during a brutal winter famine.

|

In this haunting and groundbreaking historical novel, Danielle Daniel imagines the lives of women in the Algonquin territories of the 1600s, a story inspired by her family’s ancestral link to a young girl who was murdered by French settlers.

|

Daunis Fontaine must learn what it means to be a strong Anishinaabe kwe (Ojibwe woman) and how far she’ll go for her community, even if it tears apart the only world she’s ever known.

|

How to teach with Films:

Remember, teachers want the student to be the historian. What do historians do when they watch films?

- Before they watch, ask students to research the director and producers. These are the source of the information. How will their background and experience likely bias this film?

- Also, ask students to consider the context the film was created in. The film may be about history, but it was made recently. What was going on the year the film was made that could bias the film? In particular, how do you think the gains of feminism will impact the portrayal of the female characters?

- As they watch, ask students to research the historical accuracy of the film. What do online sources say about what the film gets right or wrong?

- Afterward, ask students to describe how the female characters were portrayed and what lessons they got from the film.

- Then, ask students to evaluate this film as a learning tool. Was it helpful to better understand this topic? Did the historical inaccuracies make it unhelpful? Make it clear any informed opinion is valid.

|

We Still Live Here: Âs Nutayuneân: Remember the Wampanoags from the first Thanksgiving? The same tribe from southeastern Massachusetts was also the first group in the United States to revive its lost language. This Independent Lens documentary follows Jessie Little Doe, a Wampanoag social worker who had a dream of people speaking Wampanoag, a dead language for more than 100 years.

We Still Live Here: Âs Nutayuneân (2010) - IMDb |

|

|

What Was Ours: A Shoshone veteran, a teenage powwow princess, and an Arapaho journalist discover their purpose on the Wind River Indian Reservation as they seek lost artifacts.

What Was Ours (2016) - IMDb |

|

|

A Thousand Voices: Thousands of voices of the past present one universal story of New Mexico's Native American Women. From the creation stories through the invasions of Spain, Mexico and the United States. The power of Native American women remains strong.

A Thousand Voices (2014) - IMDb |

|

|

The Real-Life Stories of Native American Warrior Women: An 11-minute short video following the stories of 12 historic Native American women, highlighting their persistence and accomplishments.

The Real-Life Stories Of Native American Warrior Women - YouTube |

|

|

Native American Women in the Colonial Era: Women's History Month, Part 6: A 60-second short discussing how a Dutch merchant observed Native women's roles in their tribes.

Native American Women in the Colonial Era: Women's History Month, Part 6 - YouTube |

|

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Collins, Gail, America's Women: Four Hundred Years of Dolls, Drudges, Helpmates, and Heroines. New York, William Morrow, 2003.

DuBois, Ellen Carol, 1947-. Through Women's Eyes : an American History with Documents. Boston :Bedford/St. Martin's, 2005.Indians Editors. “NATIVE AMERICAN WOMEN.” Indians. N.D. http://indians.org/articles/Native-american-women.html.

“Letter from Cherokee Indian Woman to Benjamin Franklin, Governor of the State of Pennsylvania,” Paul Lauter et al., eds, The Heath Anthology of American Literature, Volume A: Beginnings to 1800, 6th ed. New York: 2009.

Megalopensis, John. “A Dutch Minister Describes the Iroquois.” Albert Bushnell Hart, ed., American History Told by Contemporaries, vol. I. New York: 1898.

Petitions of the Women’s Councils, Petition, May 2, 1817 in Presidential Papers Microfilm: Andrew Jackson. Library of Congress, series 1, reel 22.

Sanchez, Casey. "Book Review: Asegi Stories: Cherokee Queer and Two-Spirit Memory by Qwo-Li Driskill." Pasatiempo. August 19, 2016. https://www.santafenewmexican.com/pasatiempo/books/book_reviews/asegi-stories-cherokee-queer-and-two-spirit-memory-by-qwo-li-driskill/article_846a2910-9ae8-5d06-956d-234b68ea4b7e.html.

Teaching History Editors. “American Indian Women.” Teaching History. N.D. https://teachinghistory.org/history-content/ask-a-historian/23931.

Yazzie, Jolene. “Why are Diné LGBTQ+ and Two Spirit people being denied access to ceremony? We should not be discriminated against when our gender roles don’t match our sex.” High Country News. January 7, 2020. https://www.hcn.org/issues/52.2/indigenous-affairs-why-are-dine-lgbtq-and-two-spirit-people-being-denied-access-to-ceremony#:~:text=In%20the%20Din%C3%A9%20language%2C%20there,N%C3%A1dleeh%20Hastii%20(gay%20man).

Ward, Kathleen A. “Before and After the White Man: Indian Women, Property, Progress, and Power.” CONNECTICUT PUBLIC INTEREST LAW JOURNAL. Vol. 6:2. https://cpilj.law.uconn.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/2515/2018/10/6.2-Before-and-After-the-White-Man-Indian-Women-Property-Progress-and-Power-by-Kathleen-A.-Ward.pdf.

Ware, Susan. American Women’s History: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

DuBois, Ellen Carol, 1947-. Through Women's Eyes : an American History with Documents. Boston :Bedford/St. Martin's, 2005.Indians Editors. “NATIVE AMERICAN WOMEN.” Indians. N.D. http://indians.org/articles/Native-american-women.html.

“Letter from Cherokee Indian Woman to Benjamin Franklin, Governor of the State of Pennsylvania,” Paul Lauter et al., eds, The Heath Anthology of American Literature, Volume A: Beginnings to 1800, 6th ed. New York: 2009.

Megalopensis, John. “A Dutch Minister Describes the Iroquois.” Albert Bushnell Hart, ed., American History Told by Contemporaries, vol. I. New York: 1898.

Petitions of the Women’s Councils, Petition, May 2, 1817 in Presidential Papers Microfilm: Andrew Jackson. Library of Congress, series 1, reel 22.

Sanchez, Casey. "Book Review: Asegi Stories: Cherokee Queer and Two-Spirit Memory by Qwo-Li Driskill." Pasatiempo. August 19, 2016. https://www.santafenewmexican.com/pasatiempo/books/book_reviews/asegi-stories-cherokee-queer-and-two-spirit-memory-by-qwo-li-driskill/article_846a2910-9ae8-5d06-956d-234b68ea4b7e.html.

Teaching History Editors. “American Indian Women.” Teaching History. N.D. https://teachinghistory.org/history-content/ask-a-historian/23931.

Yazzie, Jolene. “Why are Diné LGBTQ+ and Two Spirit people being denied access to ceremony? We should not be discriminated against when our gender roles don’t match our sex.” High Country News. January 7, 2020. https://www.hcn.org/issues/52.2/indigenous-affairs-why-are-dine-lgbtq-and-two-spirit-people-being-denied-access-to-ceremony#:~:text=In%20the%20Din%C3%A9%20language%2C%20there,N%C3%A1dleeh%20Hastii%20(gay%20man).

Ward, Kathleen A. “Before and After the White Man: Indian Women, Property, Progress, and Power.” CONNECTICUT PUBLIC INTEREST LAW JOURNAL. Vol. 6:2. https://cpilj.law.uconn.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/2515/2018/10/6.2-Before-and-After-the-White-Man-Indian-Women-Property-Progress-and-Power-by-Kathleen-A.-Ward.pdf.

Ware, Susan. American Women’s History: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.