6. 800-300 BCE Asian Philosophies and Women’s Place

|

In Asia, three religious philosophies emerged that would define human lives for millennia to come: Hinduism, Buddhism, and Confucianism. What do these philosophies have to say about women, and what roles did women play in their founding? This varied from faith to faith, although women feel a bit like an afterthought in each. But women are all over the founding stories and traditions.

|

|

Goddess Kali, Wikimedia Commons

Goddess Kali, Wikimedia Commons

In Asia, three of many religious philosophies have dominated the lives and experiences of women: Hinduism, Confucianism, and Buddhism. While different, these philosophies existed in tandem, merged, and prescribed the way women should be treated and the role they should play– nothing like some serious mansplaining to last millennia.

Hinduism

On the Indian subcontinent, a religion known today as Hinduism was spreading. The fundamental principle was that the human soul was part of a universal soul or deity and that the final goal of humankind was to be unified with that soul. From the religion’s origin, Hindus worshiped many gods, including female goddesses. Hindus believe that through the process of birth and reincarnation humans would eventually progress to an elevated state. Good actions resulted in a rebirth at a higher social position or caste. This caste system, which divided Hindus largely into five groups, legitimized gender differences: being female was somehow a punishment for poor behavior in a previous life, and each caste had different ideals of womanhood. Like other spiritual traditions around the world that viewed women with hostility, misogynistic Hindu laws embedded this patriarchy in tradition. The Laws of Manu for instance, composed in the early common era, stated that embryos were created male and female babies were mutilated males produced by weak semen. It advocated child marriage. One principle stated that, “a virtuous wife should constantly serve her husband like a God.” Hinduism prescribed a philosophy similar to the Three Obediences found in ancient China. It also argued that a woman could only achieve spiritual salvation through her husband, and also equated all women, especially during menstruation, with the polluted lower castes. Although many now consider the Laws of Manu outdated, much of the patriarchal ethos remains entrenched in Indian and other Hindu cultures today.

Many Hindu deities are female, unlike the male God of the Christian and Jewish faiths and female deities are considered pagan.goddesses. Some of these goddesses were powerful, fearsome, and destructive. Were these just stereotypes of powerful women, or were they feminist icons? One famous portrayal of the goddess Devi, in her incarnation as Kali, shows her standing with her foot on top of her husband‘s head. Powerhouse? Yes. Did it also legitimize male fear of women?

Entrenched in Hindu philosophy is the idea of shakti, or feminine power. It holds that the feminine power is greater than masculine power and is thus in need of creative control. Nonetheless, it is believed that shakti and the masculine energy, Shiva, are equally dependent, and thus Hinduism can also provide a model of equality at a spiritual level.

Hinduism

On the Indian subcontinent, a religion known today as Hinduism was spreading. The fundamental principle was that the human soul was part of a universal soul or deity and that the final goal of humankind was to be unified with that soul. From the religion’s origin, Hindus worshiped many gods, including female goddesses. Hindus believe that through the process of birth and reincarnation humans would eventually progress to an elevated state. Good actions resulted in a rebirth at a higher social position or caste. This caste system, which divided Hindus largely into five groups, legitimized gender differences: being female was somehow a punishment for poor behavior in a previous life, and each caste had different ideals of womanhood. Like other spiritual traditions around the world that viewed women with hostility, misogynistic Hindu laws embedded this patriarchy in tradition. The Laws of Manu for instance, composed in the early common era, stated that embryos were created male and female babies were mutilated males produced by weak semen. It advocated child marriage. One principle stated that, “a virtuous wife should constantly serve her husband like a God.” Hinduism prescribed a philosophy similar to the Three Obediences found in ancient China. It also argued that a woman could only achieve spiritual salvation through her husband, and also equated all women, especially during menstruation, with the polluted lower castes. Although many now consider the Laws of Manu outdated, much of the patriarchal ethos remains entrenched in Indian and other Hindu cultures today.

Many Hindu deities are female, unlike the male God of the Christian and Jewish faiths and female deities are considered pagan.goddesses. Some of these goddesses were powerful, fearsome, and destructive. Were these just stereotypes of powerful women, or were they feminist icons? One famous portrayal of the goddess Devi, in her incarnation as Kali, shows her standing with her foot on top of her husband‘s head. Powerhouse? Yes. Did it also legitimize male fear of women?

Entrenched in Hindu philosophy is the idea of shakti, or feminine power. It holds that the feminine power is greater than masculine power and is thus in need of creative control. Nonetheless, it is believed that shakti and the masculine energy, Shiva, are equally dependent, and thus Hinduism can also provide a model of equality at a spiritual level.

Confucius, Wikimedia Commons

Confucius, Wikimedia Commons

Confucianism

In China, the rise and eventual adoption of Confucianism by the Han Dynasty represented a birth of uniquely Chinese culture that lasted for millennia, but what was that like for women? Did the improved bureaucracies and emphasis on meritocracy extend to them as well?

No. Confucian ideology emphasized moderation, virtue, and filial piety and covered up the authoritarian policies of the regime. For women, Confucianism was, and remains, a problematic barrier to women’s rights and feminism and is deeply ingrained in Asian cultures.

So who was Confucius? He lived around 500 BCE and was considered one of the great Chinese sages. He was a bureaucrat, teacher, and philosopher. He lived in a time when leaders were corrupt and not working toward the needs of the empire and its people.

He wanted social harmony and political stability grounded in trust and mutual moral obligations for China.

Confucianism is often associated with oppressing women through subjugation to the male head of the household, even to their sons during widowhood. Whether Confucious intended this discrimination is hard to know, but Confucianism and sexism are intertwined.

Confucius basically ignored women in his writing. When 10 ministers came to see the King, Confucius stated that 9 came– one of them was a woman. Why he neglected her is unclear. Was he commenting on the unusual nature of a woman in that role? Or was he merely distinguishing men from women? There are only a few direct references to women in his writings, and one of them is hostile: “Women and servants are hard to deal with.”

It is from Confucius that we get the Yin Yang concept, that balances feminine qualities and male qualities as separate but equal. Feminists today reject this model as it has been used to justify women’s subordination and exclusion from life outside the home. Yin and Yang are starkly different, as men and women have different qualities. Yang is strong, but Yin is weak and yielding. A man is honored for his strength, yet a woman is glorified for her beauty.

Confucian philosophy demanded that women live controlled lives. A woman could not earn money outside the home and was expected to leave her family to join her spouse when she married. Many baby girls were abandoned shortly after birth, a practice called “infanticide” that was not restricted to China. Baby girls in every region of the world were vulnerable simply because they were female. Female infanticide happened everywhere and continues in many places today. One ancient Chinese man recalled, “even a poor man would bring up a son, but even a rich man will dispose of a daughter.” Girls in China who survived were given virtuous names like Chastity in hopes that they would live up to that label, Chinese women had no control over who they married and had to live with their spouse’s family. The old proverb went: “A boy is born facing in; a girl is born facing out.”

In China, the rise and eventual adoption of Confucianism by the Han Dynasty represented a birth of uniquely Chinese culture that lasted for millennia, but what was that like for women? Did the improved bureaucracies and emphasis on meritocracy extend to them as well?

No. Confucian ideology emphasized moderation, virtue, and filial piety and covered up the authoritarian policies of the regime. For women, Confucianism was, and remains, a problematic barrier to women’s rights and feminism and is deeply ingrained in Asian cultures.

So who was Confucius? He lived around 500 BCE and was considered one of the great Chinese sages. He was a bureaucrat, teacher, and philosopher. He lived in a time when leaders were corrupt and not working toward the needs of the empire and its people.

He wanted social harmony and political stability grounded in trust and mutual moral obligations for China.

Confucianism is often associated with oppressing women through subjugation to the male head of the household, even to their sons during widowhood. Whether Confucious intended this discrimination is hard to know, but Confucianism and sexism are intertwined.

Confucius basically ignored women in his writing. When 10 ministers came to see the King, Confucius stated that 9 came– one of them was a woman. Why he neglected her is unclear. Was he commenting on the unusual nature of a woman in that role? Or was he merely distinguishing men from women? There are only a few direct references to women in his writings, and one of them is hostile: “Women and servants are hard to deal with.”

It is from Confucius that we get the Yin Yang concept, that balances feminine qualities and male qualities as separate but equal. Feminists today reject this model as it has been used to justify women’s subordination and exclusion from life outside the home. Yin and Yang are starkly different, as men and women have different qualities. Yang is strong, but Yin is weak and yielding. A man is honored for his strength, yet a woman is glorified for her beauty.

Confucian philosophy demanded that women live controlled lives. A woman could not earn money outside the home and was expected to leave her family to join her spouse when she married. Many baby girls were abandoned shortly after birth, a practice called “infanticide” that was not restricted to China. Baby girls in every region of the world were vulnerable simply because they were female. Female infanticide happened everywhere and continues in many places today. One ancient Chinese man recalled, “even a poor man would bring up a son, but even a rich man will dispose of a daughter.” Girls in China who survived were given virtuous names like Chastity in hopes that they would live up to that label, Chinese women had no control over who they married and had to live with their spouse’s family. The old proverb went: “A boy is born facing in; a girl is born facing out.”

Yin Yang, Public Domain

Yin Yang, Public Domain

Confucianism solidified women’s second-class status and culturally secured the prohibition on women’s formal education. Women’s education improved when outsiders gained control of traditional Chinese regions, but the domination of Confucianism locked women into perpetual slavery to their families. One scholar wrote, “Few people teach their daughters to read and write nowadays for fear that they might become over ambitious.” Another wrote, “It is sufficient for women to know a glossary of a few hundred words such as fuel, rice, fish and meat for their daily use. To know more can do more harm than good.” Analects About Women, an early text, encouraged girls to be chaste and silent. It also provided guidance for parents:

“Keep your daughter indoors… she ought to be under your total command. You should scold her roundly if she is not quick to obey, remind her often of self-discipline and household duties. Ensure that she shows due deference towards guests and that she retires quietly once the tea has been served. Do not spoil your daughter for fear of her becoming unruly. Never encourage or tolerate self-destructive behaviour for fear of fostering in her a suicidal tendency. Do not teach her to sing for fear of corrupting her mind. Do not let her loiter for fear of evil-temptation.”

“Keep your daughter indoors… she ought to be under your total command. You should scold her roundly if she is not quick to obey, remind her often of self-discipline and household duties. Ensure that she shows due deference towards guests and that she retires quietly once the tea has been served. Do not spoil your daughter for fear of her becoming unruly. Never encourage or tolerate self-destructive behaviour for fear of fostering in her a suicidal tendency. Do not teach her to sing for fear of corrupting her mind. Do not let her loiter for fear of evil-temptation.”

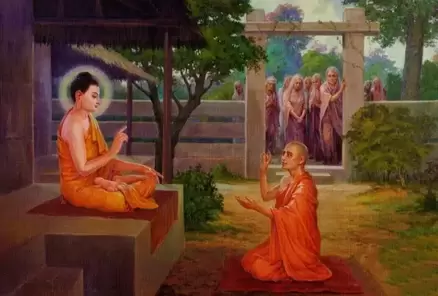

Gotami with Buddha, Wikimedia Commons

Gotami with Buddha, Wikimedia Commons

Buddhism

Gautama Buddha, the father of Buddhism, Lived and taught around the same time as Confucius. He too had a powerful philosophy that significantly affected women’s lives.

Buddhism focuses on personal development and attainment of deep knowledge. Buddhists seek to achieve enlightenment through meditation, spiritual learning, and practice. They believe in reincarnation, that life is full of suffering, and that the path to peace is through nirvana: a joyful state beyond human suffering.

In Buddha’s famous story, Mahapajapati Gotami and her sister Maya were princesses who married the king Súddhodona in ancient India. Maya gave birth to the boy who would go on to become the Buddha but she died only seven days after his birth. Her sister raised the boy along with her own children, even nursing him in infancy.

Buddha renounced his worldly wealth, living in poverty for six years. A wealthy woman offered him milky rice, enough fuel to allow him to meditate. Just before achieving enlightenment, the Buddha-to-be was overwhelmed by Mara, the God of Illusion. The Earth Mother washed Mara away with water from her hair. The Buddha is often pictured with a hand down to earth in gratitude for the Earth Mother.

Gautama Buddha, the father of Buddhism, Lived and taught around the same time as Confucius. He too had a powerful philosophy that significantly affected women’s lives.

Buddhism focuses on personal development and attainment of deep knowledge. Buddhists seek to achieve enlightenment through meditation, spiritual learning, and practice. They believe in reincarnation, that life is full of suffering, and that the path to peace is through nirvana: a joyful state beyond human suffering.

In Buddha’s famous story, Mahapajapati Gotami and her sister Maya were princesses who married the king Súddhodona in ancient India. Maya gave birth to the boy who would go on to become the Buddha but she died only seven days after his birth. Her sister raised the boy along with her own children, even nursing him in infancy.

Buddha renounced his worldly wealth, living in poverty for six years. A wealthy woman offered him milky rice, enough fuel to allow him to meditate. Just before achieving enlightenment, the Buddha-to-be was overwhelmed by Mara, the God of Illusion. The Earth Mother washed Mara away with water from her hair. The Buddha is often pictured with a hand down to earth in gratitude for the Earth Mother.

Anarka Speaks to Buddha on Gotami's behalf, Wikimedia Commons

Anarka Speaks to Buddha on Gotami's behalf, Wikimedia Commons

After the Buddha discovered the Middle Path and began to build a religious community, his aunt/adopted mother Gotami followed his teaching. Buddha improved women’s status by emphasizing man’s dependence on women, as woman is the mother of man, deserving of reverence and veneration. He also improved women’s opportunities in education and spirituality, by reluctantly allowing women into monastic life.

After the death of his father, Gotami approached the Buddha to ask if women could join the order as nuns. He refused her request. Disheartened, Gotami and her many women followers shaved their heads and put on the yellow robes worn by Buddhist monks, living as if they were already nuns, but still sought his blessing.

By tradition, the Buddha refused Gotami’s request three times. When at last one of the Buddha’s closest assistants, Ananda, offered to speak for the women, he was also at first refused. Buddha said, “women are stupid, Ananda. That is the reason, Ananda, that is the cause, why women have no place in public assemblies.” Ananda then asked the Buddha if women were capable of achieving sainthood. The Buddha agreed that they could but he still hesitated. Ananda then gently reminded the Buddha of the great love and service his aunt had rendered as his foster mother. Finally, the Buddha agreed that Gotami and the women who followed her could be ordained.

But, there was a catch. The Buddha said the women could be ordained only if they agreed to follow the “Eight Chief Rules”. The rules themselves applied only to nuns and they clearly dictated that, in every way, a nun would always be dependent upon monks and would occupy a more subservient role to the men of the order. Even a nun of “a hundred years standing”, said rule number one, should bow down to a monk even if he’d been ordained only a day earlier.

Gotami had a big choice to make. Her dedication to the Buddha and her advocacy on behalf of women like herself is undeniable. Most of the women who followed her were also widows with adult children—women who had very few opportunities for making their own way in the world. Gotami’s acceptance of the Eight Rules would cement the lower status of women within Buddhism for generations to come. Ultimately, she accepted the terms because doing so opened up new possibilities for women in India even if it came with serious limitations.

The nunnery itself was revolutionary for women. Most women in India were entirely dependent on the men in their lives. The nunnery offered something unprecedented: women living independent from their families in prayerful pursuits.

Confucianism and Buddhism spread throughout Asia and merged in some ways as the philosophies were not incompatible. In India for example, women’s status declined with the rise of organized and monotheistic faiths. The society had been patriarchal and had a strict caste system, but the abundance of powerful female goddesses and the existence of a female warrior class shows that women were regarded with high status and respect. There was a prayer for a scholarly daughter and admiring texts for female academics. Vedic texts reveal that women were honored and empowered both in traditional domestic spaces as well as in public spaces traditionally dominated by men. Yet as the Buddhist, Jainist, Brahmanist faiths expanded, child marriages became more common, and by 200 CE, women’s right to education, selection in marriage, and other observable measures of freedom were withdrawn. The introduction of Brahmanism was the final nail in the coffin of women’s ultimate subservient position. Brahmanism is the belief in one true God, or Brahman.

After the death of his father, Gotami approached the Buddha to ask if women could join the order as nuns. He refused her request. Disheartened, Gotami and her many women followers shaved their heads and put on the yellow robes worn by Buddhist monks, living as if they were already nuns, but still sought his blessing.

By tradition, the Buddha refused Gotami’s request three times. When at last one of the Buddha’s closest assistants, Ananda, offered to speak for the women, he was also at first refused. Buddha said, “women are stupid, Ananda. That is the reason, Ananda, that is the cause, why women have no place in public assemblies.” Ananda then asked the Buddha if women were capable of achieving sainthood. The Buddha agreed that they could but he still hesitated. Ananda then gently reminded the Buddha of the great love and service his aunt had rendered as his foster mother. Finally, the Buddha agreed that Gotami and the women who followed her could be ordained.

But, there was a catch. The Buddha said the women could be ordained only if they agreed to follow the “Eight Chief Rules”. The rules themselves applied only to nuns and they clearly dictated that, in every way, a nun would always be dependent upon monks and would occupy a more subservient role to the men of the order. Even a nun of “a hundred years standing”, said rule number one, should bow down to a monk even if he’d been ordained only a day earlier.

Gotami had a big choice to make. Her dedication to the Buddha and her advocacy on behalf of women like herself is undeniable. Most of the women who followed her were also widows with adult children—women who had very few opportunities for making their own way in the world. Gotami’s acceptance of the Eight Rules would cement the lower status of women within Buddhism for generations to come. Ultimately, she accepted the terms because doing so opened up new possibilities for women in India even if it came with serious limitations.

The nunnery itself was revolutionary for women. Most women in India were entirely dependent on the men in their lives. The nunnery offered something unprecedented: women living independent from their families in prayerful pursuits.

Confucianism and Buddhism spread throughout Asia and merged in some ways as the philosophies were not incompatible. In India for example, women’s status declined with the rise of organized and monotheistic faiths. The society had been patriarchal and had a strict caste system, but the abundance of powerful female goddesses and the existence of a female warrior class shows that women were regarded with high status and respect. There was a prayer for a scholarly daughter and admiring texts for female academics. Vedic texts reveal that women were honored and empowered both in traditional domestic spaces as well as in public spaces traditionally dominated by men. Yet as the Buddhist, Jainist, Brahmanist faiths expanded, child marriages became more common, and by 200 CE, women’s right to education, selection in marriage, and other observable measures of freedom were withdrawn. The introduction of Brahmanism was the final nail in the coffin of women’s ultimate subservient position. Brahmanism is the belief in one true God, or Brahman.

In every part of the world, culture enforced the idea that a woman’s sole purpose was the rearing of the children. Women who defied the norms did so at their own risk. Some were protected by class, others supported by men, and some found loopholes to exploit. But women who pushed the boundary too far or stood too strong were denounced as whores and met with violence in the form of domestic abuse, honor killings, or charges of witchcraft.

Widows in many parts of the world, no longer virgins, were expendable. Sometimes during famines, people would eat older women to survive. In India, it was common for widows to commit suicide to join their spouse in the afterlife. These women, often child brides married at 7, had never had any choice in their lives. On the death of their spouse, they were drugged and expected to join them on the burning pyre. We don't know how frequently this happened, but it remained the ideal death for a widow.

By the end of this era, so much remained in question. Why did these norms develop? Why would women submit to these norms? Why were they so universally accepted? Would women be able to circumvent these norms? Would means of women’s education and liberation become available, if not in the modern sense? Would men stop being ridiculous?

Widows in many parts of the world, no longer virgins, were expendable. Sometimes during famines, people would eat older women to survive. In India, it was common for widows to commit suicide to join their spouse in the afterlife. These women, often child brides married at 7, had never had any choice in their lives. On the death of their spouse, they were drugged and expected to join them on the burning pyre. We don't know how frequently this happened, but it remained the ideal death for a widow.

By the end of this era, so much remained in question. Why did these norms develop? Why would women submit to these norms? Why were they so universally accepted? Would women be able to circumvent these norms? Would means of women’s education and liberation become available, if not in the modern sense? Would men stop being ridiculous?

Draw your own conclusions

|

Learn how to teach with inquiry.

Many of these lesson plans were sponsored in part by the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources Eastern Region Program, coordinated by Waynesburg University, the History and Social Studies Education Faculty at Plymouth State University, and the Patrons of the Remedial Herstory Project. |

Lesson Plans from Other Organizations

- This website, Women in World History has primary source based lesson plans on women's history in a whole range of topics. Some are free while others have a cost.

- The Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media has produced recommendations for teaching women's history with primary sources and provided a collection of sources for world history. Check them out!

- The Stanford History Education Group has a number of lesson plans about women in World History.

Unknown: The Three Obediences

The Three Obediences were social, cultural guidance to women in ancient China, and present well before Confucius. They were the common expectations for women.

“Women should be obedient

Synthesis:

“Women should be obedient

- to father before marriage

- to husband after marriage

- and to son after the death of husband.”

Synthesis:

- Were the three obediences inherently sexist? Explain?

Confucian Writings: Part I

Confucius, or Kǒng Qiū 孔丘, lived around 500 BCE and was considered one of the great Chinese sages. He was a bureaucrat, teacher, and philosopher. He lived in a time when leaders were corrupt and not working toward the needs of the empire and its people. He wanted social harmony and political stability grounded in trust and mutual moral obligations for China. Confucius said very little about women. His ideas were recorded by his disciples. This is what they did say about women.

“A Confucian conception of woman is integrally related to a Confucian understanding of the cosmos. The genders female and male are placed within a cosmic harmony (he) that includes two opposite yet complementary forces, powers, or energies, namely, yin and yang… Kun is Earth, pure yin, and female: ‘Kun consists of fundamentality, and prevalence, and its fitness is that of the constancy of the mare. Here is the basic disposition of the Earth: this constitutes the image of Kun. In the same manner, the noble man with his generous virtue carries everything’ (Lynn: 142-144). The superior person is also guided by kun, the female, which is yielding, receptive, and directive of power and, like qian, productive of good. Qian initiates, whereas kun completes. Richard Wilhelm comments: ‘It is the perfect complement of THE CREATIVE [qian] -the complement, not the opposite, for the Receptive [kun] does not combat the Creative but completes it here, because there is a clearly defined hierarchic relationship between the two principles.’”

Clark, Kelly James, and Robin R. Wang. “A Confucian Defense of Gender Equity.” Journal of the American Academy of Religion 72, no. 2 (2004): 395–422. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40005811.

Questions:

“A Confucian conception of woman is integrally related to a Confucian understanding of the cosmos. The genders female and male are placed within a cosmic harmony (he) that includes two opposite yet complementary forces, powers, or energies, namely, yin and yang… Kun is Earth, pure yin, and female: ‘Kun consists of fundamentality, and prevalence, and its fitness is that of the constancy of the mare. Here is the basic disposition of the Earth: this constitutes the image of Kun. In the same manner, the noble man with his generous virtue carries everything’ (Lynn: 142-144). The superior person is also guided by kun, the female, which is yielding, receptive, and directive of power and, like qian, productive of good. Qian initiates, whereas kun completes. Richard Wilhelm comments: ‘It is the perfect complement of THE CREATIVE [qian] -the complement, not the opposite, for the Receptive [kun] does not combat the Creative but completes it here, because there is a clearly defined hierarchic relationship between the two principles.’”

Clark, Kelly James, and Robin R. Wang. “A Confucian Defense of Gender Equity.” Journal of the American Academy of Religion 72, no. 2 (2004): 395–422. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40005811.

Questions:

- Based on this text, what were Confucian ideals for women?

- What does this tell us about the gender roles in society around the time it was recorded?

Confucian Writings: Part II

Confucius, or Kǒng Qiū 孔丘, lived around 500 BCE and was considered one of the great Chinese sages. He was a bureaucrat, teacher, and philosopher. He lived in a time when leaders were corrupt and not working toward the needs of the empire and its people. He wanted social harmony and political stability grounded in trust and mutual moral obligations for China. Confucius said very little about women. His ideas were recorded by his disciples. This is what they did say about women.

"The Master said: Only women and small men seem difficult to look after. If

you keep them close, they become insubordinate; but if you keep them at a distance, they become resentful" (Analects 17:23).

“Keep your daughter indoors… she ought to be under your total command. You should scold her roundly if she is not quick to obey, remind her often of self-discipline and household duties. Ensure that she shows due deference towards guests and that she retires quietly once the tea has been served. Do not spoil your daughter for fear of her becoming unruly. Never encourage or tolerate self-destructive behaviour for fear of fostering in her a suicidal tendency. Do not teach her to sing for fear of corrupting her mind. Do not let her loiter for fear of evil-temptation.”

Goldin, Paul R. “Admonitions for Women”, Hawaii Reader in Traditional Chinese Culture (University of

Hawai’i Press, 2017).

Questions:

"The Master said: Only women and small men seem difficult to look after. If

you keep them close, they become insubordinate; but if you keep them at a distance, they become resentful" (Analects 17:23).

“Keep your daughter indoors… she ought to be under your total command. You should scold her roundly if she is not quick to obey, remind her often of self-discipline and household duties. Ensure that she shows due deference towards guests and that she retires quietly once the tea has been served. Do not spoil your daughter for fear of her becoming unruly. Never encourage or tolerate self-destructive behaviour for fear of fostering in her a suicidal tendency. Do not teach her to sing for fear of corrupting her mind. Do not let her loiter for fear of evil-temptation.”

Goldin, Paul R. “Admonitions for Women”, Hawaii Reader in Traditional Chinese Culture (University of

Hawai’i Press, 2017).

Questions:

- Based on this text, what were Confucian ideals for women?

- What does this tell us about the gender roles in society around the time it was recorded?

Ban Zhao: On Women

In China, the first historians did not emerge until the Later Han Empire (23-220) at which point there was stability and wealth, which usually led to opportunities for women intellectuals and leaders. And for the Han, this was certainly true. One of the first woman historians was Ban Zhao (45-117). It is not surprising Ban Zhao expanded on ideas about women. Ban Zhao was not immune to her time; her ideas were heavily influenced by the dominant Confucian thought.

“A woman (ought to) have four qualifications: (1) womanly virtue; (2) womanly words; (3) womanly bearing; and (4) womanly work. Now what is called womanly virtue need not be brilliant ability, exceptionally different from others. Womanly words need be neither clever in debate nor keen in conversation. Womanly appearance requires neither a pretty nor a perfect face and form. Womanly work need not be work done more skillfully than that of others.”

Yuen Ting Lee, “Ban Zhao: Scholar of Han Dynasty China,” World History Connected, last modified 2012, https://worldhistoryconnected.press.uillinois.edu/9.1/lee.html.

Questions:

- How did Zhao’s ideas for women differ from the Confucius’ that predated her?

- Is Confucianism sexist?

Sima Qian: On Empress Lü

Sima Qiuan is one of two well known early Chinese historians. He wrote histories which included Empress Lü. Sima Qian blames her actions on fear. It is to be noted Sima Qian wrote his history first and influenced later historians like Ban Gu.

The ages before the Qin are too far away and the material on them too scanty to permit a detailed account of them here. When the Han arose, Lü Exu became the official Empress of Gaozu and her son became heir apparent. Yet as she grew older and her beauty faded, the Emperor’s affection for her waned; Lady Qi was favored and her son Liu Ruyi had several times almost replaced the heir apparent. When Gaozu died, Empress Lü exterminated the Qi family and executed the King of Zhao [Liu Ruyi]. Of the women of the rear palaces, only those who had not enjoyed his favor and were far away managed to escape harm

Empress Lü’s eldest daughter was married to Zhang Ao, the marquis of Xuanping, and their daughter became the empress of Emperor Hui. Empress Dowager Lü, anxious to increase her ties [with the imperial family], hoped that this girl would give birth to a son, but though she resorted to every possible device, the young Empress remained childless. [Empress Lü] then secretly took the child of one of [Emperor Hui’s] concubines and pretended that he was the son of the Empress. When Emperor Hui passed away, it was still only a short while since the dynasty had been founded, and the question of who might succeed to the throne was unclear. Thereupon [Empress Dowager Lü] accorded great honor to the members of the outer family [Lü] and established the [male members] of the Lü as kings, so that they might act as aides. She also appointed the daughter of Lü Lu as Empress to the child Emperor. Thus she hoped to establish firm ties that would bind her own family securely to the source of power. But it was to no avail.3

Empress [Lü] as a female ruler announced [she would issue] the imperial decrees and managed to govern without going out of her chambers; and the world was peaceful, punishments and penalties were rarely employed, and those who had committed offenses then became rare. The people devoted themselves to planting and harvesting, and [as a result] clothing and food became increasingly abundant.

The ages before the Qin are too far away and the material on them too scanty to permit a detailed account of them here. When the Han arose, Lü Exu became the official Empress of Gaozu and her son became heir apparent. Yet as she grew older and her beauty faded, the Emperor’s affection for her waned; Lady Qi was favored and her son Liu Ruyi had several times almost replaced the heir apparent. When Gaozu died, Empress Lü exterminated the Qi family and executed the King of Zhao [Liu Ruyi]. Of the women of the rear palaces, only those who had not enjoyed his favor and were far away managed to escape harm

Empress Lü’s eldest daughter was married to Zhang Ao, the marquis of Xuanping, and their daughter became the empress of Emperor Hui. Empress Dowager Lü, anxious to increase her ties [with the imperial family], hoped that this girl would give birth to a son, but though she resorted to every possible device, the young Empress remained childless. [Empress Lü] then secretly took the child of one of [Emperor Hui’s] concubines and pretended that he was the son of the Empress. When Emperor Hui passed away, it was still only a short while since the dynasty had been founded, and the question of who might succeed to the throne was unclear. Thereupon [Empress Dowager Lü] accorded great honor to the members of the outer family [Lü] and established the [male members] of the Lü as kings, so that they might act as aides. She also appointed the daughter of Lü Lu as Empress to the child Emperor. Thus she hoped to establish firm ties that would bind her own family securely to the source of power. But it was to no avail.3

Empress [Lü] as a female ruler announced [she would issue] the imperial decrees and managed to govern without going out of her chambers; and the world was peaceful, punishments and penalties were rarely employed, and those who had committed offenses then became rare. The people devoted themselves to planting and harvesting, and [as a result] clothing and food became increasingly abundant.

Remedial Herstory Editors. "8. 100 BCE - 100 CE WOMEN AND THE HAN EMPIRE." The Remedial Herstory Project. November 1, 2022. www.remedialherstory.com.

AUTHOR: |

Kelsie Brook Eckert

|

Consulting Team |

Editors |

|

Kelsie Brook Eckert, Project Director

Coordinator of Social Studies Education at Plymouth State University Dr. Nancy Locklin-Sofer, Consultant Professor of History at Maryville College. Chloe Gardner, Consultant PhD Candidate in Religious Studies at Edinburgh University Dr. Whitney Howarth, Consultant Former Professor of History at Plymouth State University Jacqui Nelson, Consultant Teaching Lecturer of Military History at Plymouth State University Maria Concepcion Marquez Sandoval PhD Candidate in History at Arizona University |

Ron Kaiser

Humanities Teacher, Moultonborough Academy ReviewersAncient:

Dr. Kristin Heineman Professor of History at Colorado State University Dr. Bonnie Rock-McCutcheon Professor of History at Wilson College Sarah Stone PhD Candidate in Religious Studies at Edinburgh University Medieval: Dr. Katherine Koh Professor of History at La Sierra University Dr. Jonathan Couser Professor of History at Plymouth State University Dr. Shahla Haeri Professor of History at Boston University Lauren Cole PhD Candidate in History at Northwestern University Modern: Dr. Jack Gronau Professor of History at Northeastern University Dr. Barbara Tischler Supervisor for Hunter College Dr. Pamela Scully Professor of Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies and African Studies at Emory University |

|

Through the lenses of mysticism, naturalism, and ordinary life, the five dozen poems collected here express these women’s profound devotion to Daoist spiritual practice. Their interweaving of plain but poignant and revealing speech with a compelling and inventive use of imagery expresses their creative relationship to the myths, legends, and traditions of Daoist Goddess culture.

Challenges accepted beliefs that Confucianism is a cause of women’s oppression and explores Confucianism as an ethical system compatible with gender parity.

|

|

Bibliography

National Geographic Editors. “Chinese Religions and Philosophies.” National Geographic. N.D.https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/chinese-religions-and-philosophies

Goldin, Paul R. “Ban Zhao in Her Time and in Ours”, After Confucius: Studies in Early Chinese Philosophy (University of Hawai’i Press, 2005)

Goldin, Paul R. “Admonitions for Women”, Hawaii Reader in Traditional Chinese Culture (University of Hawai’i Press, 2017)

Ohnuma, Reiko. “The Debt to the Mother: A Neglected Aspect of the Founding of the Buddhist Nuns’ Order”, Journal of the American Academy of Religion, Dec. 2006, Vol. 74, No. 4, pp. 861-901.

Phongsai, Arree. “The Eight Chief Rules for Bhikkhunis”, The Tibet Journal, Summer 1984, Vol. 9, No. 10, pp. 35-37.

Willis, John E. “Ban Zhao”, Mountains of Fame: Portraits in Chinese History (Princeton University Press, 1994.

Goldin, Paul R. “Ban Zhao in Her Time and in Ours”, After Confucius: Studies in Early Chinese Philosophy (University of Hawai’i Press, 2005)

Goldin, Paul R. “Admonitions for Women”, Hawaii Reader in Traditional Chinese Culture (University of Hawai’i Press, 2017)

Ohnuma, Reiko. “The Debt to the Mother: A Neglected Aspect of the Founding of the Buddhist Nuns’ Order”, Journal of the American Academy of Religion, Dec. 2006, Vol. 74, No. 4, pp. 861-901.

Phongsai, Arree. “The Eight Chief Rules for Bhikkhunis”, The Tibet Journal, Summer 1984, Vol. 9, No. 10, pp. 35-37.

Willis, John E. “Ban Zhao”, Mountains of Fame: Portraits in Chinese History (Princeton University Press, 1994.