22. 1700-1850 The Enlightenment and Women

|

The Enlightenment is well-known for the philosophical and societal changes it brought to the modern world, and women found their place in this period of rapid change. Great female leaders such as Catherine the Great and Olympe de Gouges inspired women of future suffrage movements and women today. Defying male and societal expectations was a recurring theme during this time.

|

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

The Enlightenment was a time of social upheaval and restructuring of western societies. Monarchs were overthrown in favor of democracies. Men previously bound to live lives similar to their fathers now found opportunities in government and commerce. While these changes catapulted the world forward into the modern era, it would be more than a century before the same concept of human agency would be extended to women. In kingdoms and empires where female monarchs had been relatively routine, women were barred from the politics of the democracies that replaced them. It’s important that we ask, enlightened for whom?

The Bad

The Protestant Reformation in Europe had inspired a degree of progress for women in terms of their access to education, but the general view by men of women’s intellect and need for education remained negative. Although change did not seem apparent, there was a small social revolution taking place in the political climate of the Enlightenment.

Across the western world, the rise in state-sponsored schools was motivated by the Protestant belief that it was the duty of the family, church, and state to educate every child, male and female to gain spiritual understanding. Boys were first and girls followed. Nevertheless, male attitudes toward women’s intellectual promise remained steadfast. Even profound thinkers of the time could not fathom the need for women’s education. For example...

The Bad

The Protestant Reformation in Europe had inspired a degree of progress for women in terms of their access to education, but the general view by men of women’s intellect and need for education remained negative. Although change did not seem apparent, there was a small social revolution taking place in the political climate of the Enlightenment.

Across the western world, the rise in state-sponsored schools was motivated by the Protestant belief that it was the duty of the family, church, and state to educate every child, male and female to gain spiritual understanding. Boys were first and girls followed. Nevertheless, male attitudes toward women’s intellectual promise remained steadfast. Even profound thinkers of the time could not fathom the need for women’s education. For example...

Ideal Role of Women in Enlightenment, Public Domain

Ideal Role of Women in Enlightenment, Public Domain

Immanuel Kant felt women were like incomplete men, stating, “[M]an should become more perfect as a man, and the woman as a wife.” To belittle women further, he added, “[Women] need to know nothing more of the cosmos than is necessary to make the appearance of the heavens on a beautiful evening a stimulating sight to them.” He continued, “Even if a woman excels in arduous learning and painstaking thinking, they will exterminate the merits of her sex.”

Another intellectual, Johann Gottlieb Fichte, wrote, “[A woman’s] dignity requires that she should give herself entirely as she is [to her husband] and . . . utterly lose herself in him. The least consequence is that she should renounce to him all her property and her rights. Henceforth, she has life and activity only under his eyes and in his business. She has ceased to live the life of an individual; her life has become a part of the life of her lover… Woman . . . cannot and shall not go beyond the limits of her feeling.”

The ideas of these men were rooted in Ancient thinking, but the world was moving fast toward a politics of individualism, and women were bound to have a place in Europe’s movement or social, economic, and political change.

Another intellectual, Johann Gottlieb Fichte, wrote, “[A woman’s] dignity requires that she should give herself entirely as she is [to her husband] and . . . utterly lose herself in him. The least consequence is that she should renounce to him all her property and her rights. Henceforth, she has life and activity only under his eyes and in his business. She has ceased to live the life of an individual; her life has become a part of the life of her lover… Woman . . . cannot and shall not go beyond the limits of her feeling.”

The ideas of these men were rooted in Ancient thinking, but the world was moving fast toward a politics of individualism, and women were bound to have a place in Europe’s movement or social, economic, and political change.

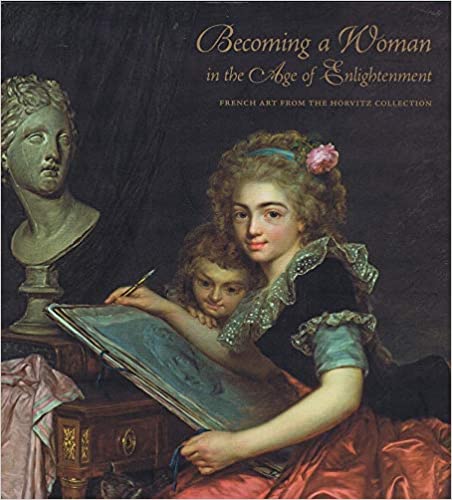

Salons and Coffeehouses

Women found their place in intellectualism. In France, laws barred the gathering of intellectuals and political criticism, and women of the aristocracy became increasingly involved in welcoming thinkers in “Salons.” Madame Rambouillet’s salon, known as “la Chambre Bleue,” opened in 1618 as an escape from the shallow and rigid court life. There, great minds sang, recited poetry, and exchanged ideas. Her model was quickly copied by other hostesses around Paris.

The women who managed salons could share their ideas with their patrons. They were educated, literate, versed in mediation, and wealthy. They selected their patrons with care, sometimes requiring a letter of recommendation for entrance. The salons established a haven for French intellectuals to discuss ideas freely and women had a front seat. These Salonierre’s managed conversations with ease. Madame de Tencin and Mademoiselle Lespinasse had more liberal approaches to their guests diving into divisive topics like politics. Whereas Madame Geoffrin and Madame de Rambouillet, strictly managed the topics. If conversation waned or became uncomfortably dangerous, Geoffrin would put an end to the discussion with her famous simple phrase “Voilà qui est bien,” or “That’s enough.” Intellectuals from around Europe came to participate.

Even the King’s official mistress was a participant. Jeanne Antionnette Poisson, better known as Madame Pompadour, used her position and wealth to host thinkers like Voltaire and Diderot. She also lobbied for the publication of France's first encyclopedia as a means to disseminate knowledge to anyone who could read. Pompadour has perhaps been mistreated in history for using sex to influence the King, but in the sheltered court at Versailles, everyone was involved in intrigue. The King relied on her as an advisor, sometimes de facto prime minister, but she was also patron of the arts and intellectuals.

Women found their place in intellectualism. In France, laws barred the gathering of intellectuals and political criticism, and women of the aristocracy became increasingly involved in welcoming thinkers in “Salons.” Madame Rambouillet’s salon, known as “la Chambre Bleue,” opened in 1618 as an escape from the shallow and rigid court life. There, great minds sang, recited poetry, and exchanged ideas. Her model was quickly copied by other hostesses around Paris.

The women who managed salons could share their ideas with their patrons. They were educated, literate, versed in mediation, and wealthy. They selected their patrons with care, sometimes requiring a letter of recommendation for entrance. The salons established a haven for French intellectuals to discuss ideas freely and women had a front seat. These Salonierre’s managed conversations with ease. Madame de Tencin and Mademoiselle Lespinasse had more liberal approaches to their guests diving into divisive topics like politics. Whereas Madame Geoffrin and Madame de Rambouillet, strictly managed the topics. If conversation waned or became uncomfortably dangerous, Geoffrin would put an end to the discussion with her famous simple phrase “Voilà qui est bien,” or “That’s enough.” Intellectuals from around Europe came to participate.

Even the King’s official mistress was a participant. Jeanne Antionnette Poisson, better known as Madame Pompadour, used her position and wealth to host thinkers like Voltaire and Diderot. She also lobbied for the publication of France's first encyclopedia as a means to disseminate knowledge to anyone who could read. Pompadour has perhaps been mistreated in history for using sex to influence the King, but in the sheltered court at Versailles, everyone was involved in intrigue. The King relied on her as an advisor, sometimes de facto prime minister, but she was also patron of the arts and intellectuals.

Jeanne Antionnette Poisson, better known as Madame Pompadour, Wikimedia Commons

Jeanne Antionnette Poisson, better known as Madame Pompadour, Wikimedia Commons

Not all intellectuals enjoyed the salons. Jean-Jacques Rousseau felt that women’s presence in the salons degraded serious conversation among men. He also resented women micromanaging the conversation. He said, “they talk about everything so everyone will have something to say; they do not explore questions deeply, for fear of becoming tedious, they propose them as if in passing, deal with them rapidly, precision leads to elegance; each states his opinion and supports it in few words; no one vehemently attacks someone else’s, no one tenaciously defends his own; they discuss for enlightenment, stop before the dispute begins; everyone is instructed, everyone is entertained, all go away contented.”

Across the channel, the coffee houses of the Islamic world could be found in Oxford as early as 1652. Thinkers came to the coffee houses to discuss ideas, science, and chatter. Each coffee house had a particular clientele, defined by scholarly interests, politics, or occupation. The coffeehouses created a sense of meritocracy and leveled the playing field to allow for the sharing of ideas.

Women frequently attended coffeehouses to take part in “sober” discourse. Famous male intellectuals wrote accounts describing conversing with women at the coffee house.

Almost half the coffeehouses were owned and operated by women. Most women at these houses were there to work in some capacity. Women owned, managed, labored and served in coffeehouses across the United Kingdom. Coffee house debates could become rowdy.

Women were not merely the hostesses, they also thought and wrote extensively on enlightenment ideas. Their works and theories were widely read by their male peers and became staples of Enlightenment thinking.

Across the channel, the coffee houses of the Islamic world could be found in Oxford as early as 1652. Thinkers came to the coffee houses to discuss ideas, science, and chatter. Each coffee house had a particular clientele, defined by scholarly interests, politics, or occupation. The coffeehouses created a sense of meritocracy and leveled the playing field to allow for the sharing of ideas.

Women frequently attended coffeehouses to take part in “sober” discourse. Famous male intellectuals wrote accounts describing conversing with women at the coffee house.

Almost half the coffeehouses were owned and operated by women. Most women at these houses were there to work in some capacity. Women owned, managed, labored and served in coffeehouses across the United Kingdom. Coffee house debates could become rowdy.

Women were not merely the hostesses, they also thought and wrote extensively on enlightenment ideas. Their works and theories were widely read by their male peers and became staples of Enlightenment thinking.

Maria Theresa, Wikimedia Commons

Maria Theresa, Wikimedia Commons

Maria Theresa

Some monarchs chose to embrace Enlightenment thinking. Maria Theresa, the Habsburg queen considered the grandmother of Europe because so many of her children were married to European royalty, ruled in her own right as Empress of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, a position she inherited. Initially her legitimacy was challenged by invading armies when she was just a young pregnant mother. After successfully winning these military engagements, Maria Theresa sought to stabilize her empire and bring it into a period of growth. She was a vocal opponent of Enlightenment thinking, but she nevertheless embraced many Enlightenment ideas. She expanded access to education, improved meritocracy in government positions, and initiated a number of social reforms to help the poor. She promoted schools and women’s education. Her goal was, “to make both sexes good Christians, and industrious, intelligent, and obedient subjects in the different orders of society.”

Some monarchs chose to embrace Enlightenment thinking. Maria Theresa, the Habsburg queen considered the grandmother of Europe because so many of her children were married to European royalty, ruled in her own right as Empress of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, a position she inherited. Initially her legitimacy was challenged by invading armies when she was just a young pregnant mother. After successfully winning these military engagements, Maria Theresa sought to stabilize her empire and bring it into a period of growth. She was a vocal opponent of Enlightenment thinking, but she nevertheless embraced many Enlightenment ideas. She expanded access to education, improved meritocracy in government positions, and initiated a number of social reforms to help the poor. She promoted schools and women’s education. Her goal was, “to make both sexes good Christians, and industrious, intelligent, and obedient subjects in the different orders of society.”

Catherine the Great, Wikimedia Commons

Catherine the Great, Wikimedia Commons

Catherine the Great

In Russia, another monarch dodged political revolution by adopting Enlightenment ideas. Following the westernization reforms of Peter the Great, in the 1760s, Catherine the Great further shifted the cultural and intellectual Russian world.

Catherine was born in 1729, the well-educated eldest daughter of an impoverished Prussian prince. She was sought by the Russian Empress Elizabeth as a wife for Elizabeth’s nephew, Peter, a descendant of Peter the Great.

A product of the Enlightenment, Catherine and Peter were married for eight years in what was a rocky and childless marriage. They both had extra-marital affairs at court, she with Sergei Saltykov, a Russian military officer whom the Empress Elizabeth preferred over her own nephew.

Soon after, Catherine became pregnant. This led to wild scandal that perhaps Peter was either sterile or incapable of consummating their marriage. Her son Paul was deemed a legitimate heir, but there was no question that her subsequent three children were fathered by other men.

When Elizabeth died in 1762, Peter's inability to lead was quickly evident. Catherine plotted a bloodless coup to arrest and overthrow her own husband. In custody for only eight days, having ruled for less than six months, Peter died, possibly at the hands of Catherine’s new lover, though there is no evidence that she knew of the plans for his murder.

Catherine’s reign was marked by vast territorial expansion and governmental reforms. Catherine considered herself to be one of Europe’s most enlightened rulers, and historians agree. She wrote numerous books, pamphlets, and educational materials aimed at improving Russia’s education system. She was a champion of the arts, maintaining a lifelong correspondence with Voltaire and other prominent minds of the era. She was also one of those rare elite women who used their position to help other women, establishing the first higher education institution for women in Russia.

Historians and contemporaries loved to gossip about Catherine’s love life, which included a lot of lovers whom she was incredibly loyal to throughout and after their love affairs. Had she been male, these love affairs probably would have hardly been mentioned in chronicles. She bestowed upon her lovers indentured servants, land, and titles. When Catherine died, her unconventional and apparently “lustful life” was an open secret.

In Russia, another monarch dodged political revolution by adopting Enlightenment ideas. Following the westernization reforms of Peter the Great, in the 1760s, Catherine the Great further shifted the cultural and intellectual Russian world.

Catherine was born in 1729, the well-educated eldest daughter of an impoverished Prussian prince. She was sought by the Russian Empress Elizabeth as a wife for Elizabeth’s nephew, Peter, a descendant of Peter the Great.

A product of the Enlightenment, Catherine and Peter were married for eight years in what was a rocky and childless marriage. They both had extra-marital affairs at court, she with Sergei Saltykov, a Russian military officer whom the Empress Elizabeth preferred over her own nephew.

Soon after, Catherine became pregnant. This led to wild scandal that perhaps Peter was either sterile or incapable of consummating their marriage. Her son Paul was deemed a legitimate heir, but there was no question that her subsequent three children were fathered by other men.

When Elizabeth died in 1762, Peter's inability to lead was quickly evident. Catherine plotted a bloodless coup to arrest and overthrow her own husband. In custody for only eight days, having ruled for less than six months, Peter died, possibly at the hands of Catherine’s new lover, though there is no evidence that she knew of the plans for his murder.

Catherine’s reign was marked by vast territorial expansion and governmental reforms. Catherine considered herself to be one of Europe’s most enlightened rulers, and historians agree. She wrote numerous books, pamphlets, and educational materials aimed at improving Russia’s education system. She was a champion of the arts, maintaining a lifelong correspondence with Voltaire and other prominent minds of the era. She was also one of those rare elite women who used their position to help other women, establishing the first higher education institution for women in Russia.

Historians and contemporaries loved to gossip about Catherine’s love life, which included a lot of lovers whom she was incredibly loyal to throughout and after their love affairs. Had she been male, these love affairs probably would have hardly been mentioned in chronicles. She bestowed upon her lovers indentured servants, land, and titles. When Catherine died, her unconventional and apparently “lustful life” was an open secret.

Theroigne de Mericourt, Wikimedia Commons

Theroigne de Mericourt, Wikimedia Commons

American Revolution

But not all monarchs embraced Enlightenment thinking, and they paid dearly for it. The American Revolution was the first political revolution as a result of Enlightenment thought. Women were foundational in rallying support for the war and imagining the government that would replace the English rule they found increasingly taxing.

French Revolution

Across the ocean, inspired by the American Revolution, French revolutionaries saw an opportunity to overthrow the corrupt King Louis and his unscrupulous wife, Marie Antoinette, the daughter of Maria Teresa. France was divided into three estates: the first was the nobility who represented about 1% of the population, the second was the church which again represented 1% of the population, and the other 98% of the population was the commoners who lived in abject poverty. Marie Antoinette lived at the palace of Versailles, a hugely expensive and elaborate estate built by previous Kings. Here she hosted elaborate parties and bought gowns to the envy of the world although the people were starving for basic necessities, like bread.

For years the commoners tried to negotiate. They asked for greater representation in the legislature. When the nobility refused, they broke off forming their own legislature. In May 1789 the commoners declared themselves a National Assembly, which operated outside the monarchy’s supervision. In response, King Louis XVI shut down the spaces where they were meeting, so the men gathered in an indoor tennis court and pledged their unity until France had a new constitution. Women were excluded from these events. They routinely asked for a seat at the table and were routinely denied.

Rebellion in France began on July 14, 1789, when a Paris mob stormed the Bastille prison in search of arms and ammunition. At the time, over 30,000 pounds of gunpowder was stored. there. The Bastille, was to them, a symbol of the monarchy's tyranny. Women were not just in the crowd, they were at the front. A woman, dressed like an Amazon, led the attack. She was a 26-year-old Belgian named Theroigne de Mericourt. She had only recently moved to Paris to escape a painful past as a prostitute. She had dressed in men’s clothes and embraced the revolutionary spirit of France. Royalists called her the “patriots’ whore“ and the hideous “war chief“ of the revolution. Her background as a prostitute didn’t help when they accused her of having sex with all 576 members of the National Assembly.

But not all monarchs embraced Enlightenment thinking, and they paid dearly for it. The American Revolution was the first political revolution as a result of Enlightenment thought. Women were foundational in rallying support for the war and imagining the government that would replace the English rule they found increasingly taxing.

French Revolution

Across the ocean, inspired by the American Revolution, French revolutionaries saw an opportunity to overthrow the corrupt King Louis and his unscrupulous wife, Marie Antoinette, the daughter of Maria Teresa. France was divided into three estates: the first was the nobility who represented about 1% of the population, the second was the church which again represented 1% of the population, and the other 98% of the population was the commoners who lived in abject poverty. Marie Antoinette lived at the palace of Versailles, a hugely expensive and elaborate estate built by previous Kings. Here she hosted elaborate parties and bought gowns to the envy of the world although the people were starving for basic necessities, like bread.

For years the commoners tried to negotiate. They asked for greater representation in the legislature. When the nobility refused, they broke off forming their own legislature. In May 1789 the commoners declared themselves a National Assembly, which operated outside the monarchy’s supervision. In response, King Louis XVI shut down the spaces where they were meeting, so the men gathered in an indoor tennis court and pledged their unity until France had a new constitution. Women were excluded from these events. They routinely asked for a seat at the table and were routinely denied.

Rebellion in France began on July 14, 1789, when a Paris mob stormed the Bastille prison in search of arms and ammunition. At the time, over 30,000 pounds of gunpowder was stored. there. The Bastille, was to them, a symbol of the monarchy's tyranny. Women were not just in the crowd, they were at the front. A woman, dressed like an Amazon, led the attack. She was a 26-year-old Belgian named Theroigne de Mericourt. She had only recently moved to Paris to escape a painful past as a prostitute. She had dressed in men’s clothes and embraced the revolutionary spirit of France. Royalists called her the “patriots’ whore“ and the hideous “war chief“ of the revolution. Her background as a prostitute didn’t help when they accused her of having sex with all 576 members of the National Assembly.

Women's March on Versailles, Wikimedia Commons

Women's March on Versailles, Wikimedia Commons

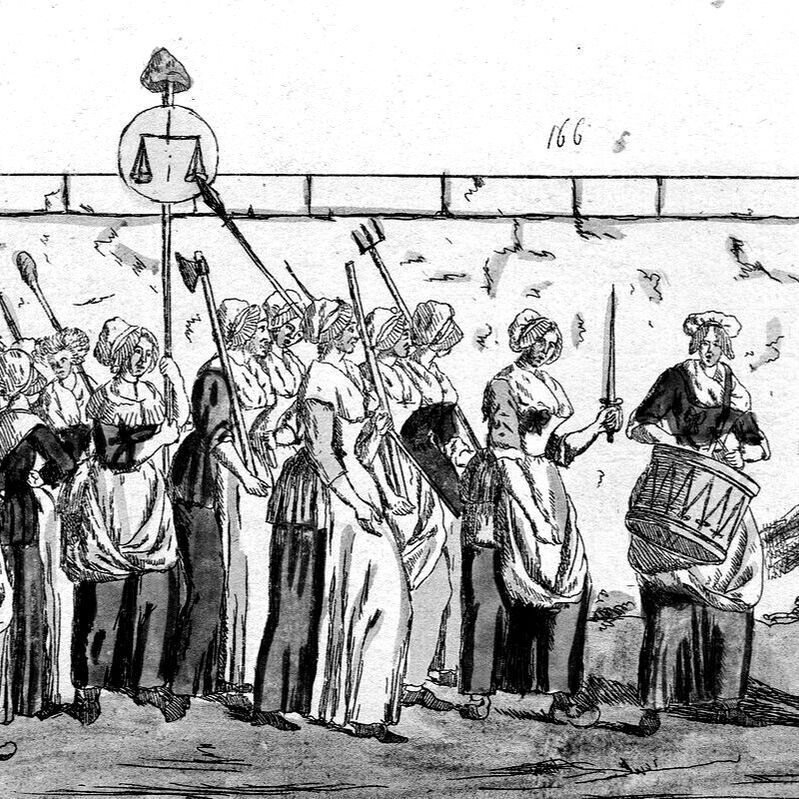

Women’s March on Versaille

Three months later, Theroigne again led the charge again in the Women’s March on Versailles. Why were women leading the charge? Because women were suffering. As caregivers, they often fed their families before they fed themselves. They were hungrier and angrier as they watched their own children deteriorate because they lacked bread, while women in the aristocracy thrived in elegant gowns and at extravagant dinner parties.

On October 5, 1789, a young woman marched through the streets of Paris beating a drum. She was joined by about seven thousand of her fellow countrywomen, some wielding makeshift weapons. They seized a church and began ringing the bells to wake their countrymen, all the while chanting “When will we have bread?” A group of fishwives, who were perhaps the rowdiest of the marchers and famously vulgar, began shouting, “The old order? We don’t give a f*** for your order!”

The mob was only dissuaded from engaging in more violence when officials steered their anger toward the Man in charge, King Louis. The mob marched for six hours to the Palace of Versailles, where they were greeted with refreshments. Women shouted proclamations of outrage and asserted that they had come to overthrow those who were not serving the will of the people. Women began chanting anti-clerical slogans. One woman slapped a priest who offered his hand in greeting, stating, "I am not made to kiss the paw of a dog.”

Three months later, Theroigne again led the charge again in the Women’s March on Versailles. Why were women leading the charge? Because women were suffering. As caregivers, they often fed their families before they fed themselves. They were hungrier and angrier as they watched their own children deteriorate because they lacked bread, while women in the aristocracy thrived in elegant gowns and at extravagant dinner parties.

On October 5, 1789, a young woman marched through the streets of Paris beating a drum. She was joined by about seven thousand of her fellow countrywomen, some wielding makeshift weapons. They seized a church and began ringing the bells to wake their countrymen, all the while chanting “When will we have bread?” A group of fishwives, who were perhaps the rowdiest of the marchers and famously vulgar, began shouting, “The old order? We don’t give a f*** for your order!”

The mob was only dissuaded from engaging in more violence when officials steered their anger toward the Man in charge, King Louis. The mob marched for six hours to the Palace of Versailles, where they were greeted with refreshments. Women shouted proclamations of outrage and asserted that they had come to overthrow those who were not serving the will of the people. Women began chanting anti-clerical slogans. One woman slapped a priest who offered his hand in greeting, stating, "I am not made to kiss the paw of a dog.”

Queen Marie Antoinette, Wikimedia Commons

Queen Marie Antoinette, Wikimedia Commons

It took a while to calm the crowd and elect a delegation of six women to see the King. One of the selected, Pierrette Chabry, was only seventeen, and fainted when she saw the King. Louis promised them that food would be sent to Paris to feed the hungry.

Early the next morning, an armed group of people broke into the royal apartments screaming that they intended to "tear out [the Queen Marie Antoinette’s] heart…cut off her head, fricassee her liver.” Two guards were murdered in the process. Marie Antoinette ran barefoot from her room shouting for someone to save her children. The intruders were stopped by National Guardsmen who whisked the Queen and her children away.

Just hours later, the Queen appeared on a balcony in front of the wild crowd of 60 thousand or more people as a show of faith. Their home surrounded, the royal family had no choice but to go to Paris. The King announced, "My friends, I shall go to Paris with my wife and my children…it is to the love of my good and faithful subjects that I entrust all that is most precious to me!"

The crowd followed the royal family and wagons full of flour and bread to Paris. Women celebrated their victory, singing that they were bringing "the baker, the baker's wife, and the baker's lad to Paris!"

Early the next morning, an armed group of people broke into the royal apartments screaming that they intended to "tear out [the Queen Marie Antoinette’s] heart…cut off her head, fricassee her liver.” Two guards were murdered in the process. Marie Antoinette ran barefoot from her room shouting for someone to save her children. The intruders were stopped by National Guardsmen who whisked the Queen and her children away.

Just hours later, the Queen appeared on a balcony in front of the wild crowd of 60 thousand or more people as a show of faith. Their home surrounded, the royal family had no choice but to go to Paris. The King announced, "My friends, I shall go to Paris with my wife and my children…it is to the love of my good and faithful subjects that I entrust all that is most precious to me!"

The crowd followed the royal family and wagons full of flour and bread to Paris. Women celebrated their victory, singing that they were bringing "the baker, the baker's wife, and the baker's lad to Paris!"

Pauline Leon, Library of Congress

Pauline Leon, Library of Congress

Political Involvement

By 1790, women remained excluded from the political clubs formed to discuss political ideas and envision a post-revolution world. The Fraternal Society of Patriots of Both Sexes allowed women to take active roles, hold offices, and mix with male intellectuals. Women also founded their own political clubs such as the Patriotic and Charitable Society of the Women Friends of Truth, the Society of Revolutionary Republican Women, and the Republican Revolutionary Women Citizens Club. These clubs provided a safe haven where women could challenge not only the monarchy, but the patriarchy, which these women grew to see as intertwined.

Almost every one of the women who had thrown herself into the revolutionary spirit was struggling with a challenging past, a failed love affair, abandonment, and the general failures of the patriarchy to do what it, in theory, intended to do, “protect women.“ The women of France matched or out matched their male partners in the uprisings. Women saw the fall of the male monarch as the fall of the patriarchy and took up the revolutionary spirit with fervor.

Pauline Leon hoped women could become equal in every aspect of society, including involvement in the Armed Forces. She advocated for an all-female national guard to defend Paris and themselves from possible invasion by Austria or Prussia. Her initiative was struck down repeatedly by the men in the movement.

By 1790, women remained excluded from the political clubs formed to discuss political ideas and envision a post-revolution world. The Fraternal Society of Patriots of Both Sexes allowed women to take active roles, hold offices, and mix with male intellectuals. Women also founded their own political clubs such as the Patriotic and Charitable Society of the Women Friends of Truth, the Society of Revolutionary Republican Women, and the Republican Revolutionary Women Citizens Club. These clubs provided a safe haven where women could challenge not only the monarchy, but the patriarchy, which these women grew to see as intertwined.

Almost every one of the women who had thrown herself into the revolutionary spirit was struggling with a challenging past, a failed love affair, abandonment, and the general failures of the patriarchy to do what it, in theory, intended to do, “protect women.“ The women of France matched or out matched their male partners in the uprisings. Women saw the fall of the male monarch as the fall of the patriarchy and took up the revolutionary spirit with fervor.

Pauline Leon hoped women could become equal in every aspect of society, including involvement in the Armed Forces. She advocated for an all-female national guard to defend Paris and themselves from possible invasion by Austria or Prussia. Her initiative was struck down repeatedly by the men in the movement.

Olympe de Gouge, Wikimedia Commons

Olympe de Gouge, Wikimedia Commons

Olympe de Gouges

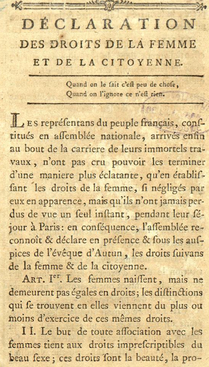

Beyond taking to the streets or joining an intellectual political club, women were also powerful leaders and voices of Enlightenment thinking. Olympe de Gouges emulated the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen but added, “and woman.” She advocated the emancipation of women and freedom for the enslaved people throughout the French empire. She pointed out, by copying the language used by men, the hypocrisy of not extending these same privileges and rights to government and property to women.

De Gouges lived an unconventional life. At 17, she was forced into marriage with an older man she despised. She gave birth to a son named Pierre, and shortly after, her husband died.A year later, she fell in love with a rich man, whose family wouldn’t let her marry him; so, she and her son moved into an apartment near him in Paris, where he paid for her lodgings and provided for her welfare for the rest of her life. Living an independent life for a woman in her time, Olympe was free to pursue her passions. She joined a salon where she met “the father of economics“ Adam Smith and the American Thomas Jefferson.

Olympe was impressive. With a little formal education, she pointedly saw that female inferiority was not necessarily inherent, but ordained by rules promulgated by men.. It was the systems of government and society that degraded women’s lives. She noticed that everyday power, the decision over finances, and many more, were in the hands of men and men alone. Her writings were a direct attack on the principles of male supremacy.

She wrote, “Women, wake up… recognize your rights! Oh women, women, when will you cease to be blind? What advantages have you gathered in the revolution? A scorn more marked at a stain more conspicuous… Whatever the barrier set up against you, it is in your power to overcome them; you only have to want it!”

Beyond taking to the streets or joining an intellectual political club, women were also powerful leaders and voices of Enlightenment thinking. Olympe de Gouges emulated the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen but added, “and woman.” She advocated the emancipation of women and freedom for the enslaved people throughout the French empire. She pointed out, by copying the language used by men, the hypocrisy of not extending these same privileges and rights to government and property to women.

De Gouges lived an unconventional life. At 17, she was forced into marriage with an older man she despised. She gave birth to a son named Pierre, and shortly after, her husband died.A year later, she fell in love with a rich man, whose family wouldn’t let her marry him; so, she and her son moved into an apartment near him in Paris, where he paid for her lodgings and provided for her welfare for the rest of her life. Living an independent life for a woman in her time, Olympe was free to pursue her passions. She joined a salon where she met “the father of economics“ Adam Smith and the American Thomas Jefferson.

Olympe was impressive. With a little formal education, she pointedly saw that female inferiority was not necessarily inherent, but ordained by rules promulgated by men.. It was the systems of government and society that degraded women’s lives. She noticed that everyday power, the decision over finances, and many more, were in the hands of men and men alone. Her writings were a direct attack on the principles of male supremacy.

She wrote, “Women, wake up… recognize your rights! Oh women, women, when will you cease to be blind? What advantages have you gathered in the revolution? A scorn more marked at a stain more conspicuous… Whatever the barrier set up against you, it is in your power to overcome them; you only have to want it!”

Execution of Olympe de Gouges, Wikimedia Commons

Execution of Olympe de Gouges, Wikimedia Commons

She dedicated the piece to Queen Marie Antoinette, hoping to bring these hypocrisies to the queen's attention and gain support from the most famous woman in the empire. The dedication would prove to be her undoing. Tying peace to the monarchy led many male radicals to accuse her of having monarchist sympathies.. She was far from a monarchist. She merely took what the men were saying and extended it to the other 50% of the population! She wanted democracy, and she wanted it for everybody

As tensions in Paris mounted, Olympe left the city to be with her son who had been wounded in battle, but she was arrested in July 1793. In October, Marie Antoinnette was dragged to the scaffold in a public spectacle and executed by the guillotine, as the French revolutionaries sought to show the public that the power was truly back in the people’s hand. On October 30, the National Convention issued the decree excluding women from all political activity. All of the women’s political clubs were closed, their leaders were arrested, and the revolutionary engagement that women had experienced trickled to a halt. The president of the Paris Revolutionary Council, Pierre Chalmette, wrote, “impudent women who want to turn themselves into men, don’t you have enough already?”

As the reign of terror began in Paris that saw the purging of anyone considered loyal to the monarchy tried where the verdict was all but predetermined. Olympe was in prison for treason, her life threatened, and yet she did not back down. She wrote bold statements from her prison cell.

In her trial she was ironically named, “the widow Aubrey,” after her old and long dead husband. The authorities stripped her of her chosen name and gave her the name the patriarchy demanded. In a desperate attempt to save her life, she claimed to be pregnant. She was subsequently inspected by a physician who found that she was not pregnant. She was beheaded unceremoniously. On the platform she cried out, “Children of the mother country, you will avenge my death!” Five days later, another woman was executed for engaging in politics while being female.

Did the Enlightenment include women? Not in France. Women’s Enlightenment and enfranchisement were stopped dead by a sharp blade. The French Revolution moved the scale forward a little bit for men, but women would remain domesticated.

As tensions in Paris mounted, Olympe left the city to be with her son who had been wounded in battle, but she was arrested in July 1793. In October, Marie Antoinnette was dragged to the scaffold in a public spectacle and executed by the guillotine, as the French revolutionaries sought to show the public that the power was truly back in the people’s hand. On October 30, the National Convention issued the decree excluding women from all political activity. All of the women’s political clubs were closed, their leaders were arrested, and the revolutionary engagement that women had experienced trickled to a halt. The president of the Paris Revolutionary Council, Pierre Chalmette, wrote, “impudent women who want to turn themselves into men, don’t you have enough already?”

As the reign of terror began in Paris that saw the purging of anyone considered loyal to the monarchy tried where the verdict was all but predetermined. Olympe was in prison for treason, her life threatened, and yet she did not back down. She wrote bold statements from her prison cell.

In her trial she was ironically named, “the widow Aubrey,” after her old and long dead husband. The authorities stripped her of her chosen name and gave her the name the patriarchy demanded. In a desperate attempt to save her life, she claimed to be pregnant. She was subsequently inspected by a physician who found that she was not pregnant. She was beheaded unceremoniously. On the platform she cried out, “Children of the mother country, you will avenge my death!” Five days later, another woman was executed for engaging in politics while being female.

Did the Enlightenment include women? Not in France. Women’s Enlightenment and enfranchisement were stopped dead by a sharp blade. The French Revolution moved the scale forward a little bit for men, but women would remain domesticated.

Mary Wollstonecraft, Wikimedia Commons

Mary Wollstonecraft, Wikimedia Commons

Mary Wollstonecraft

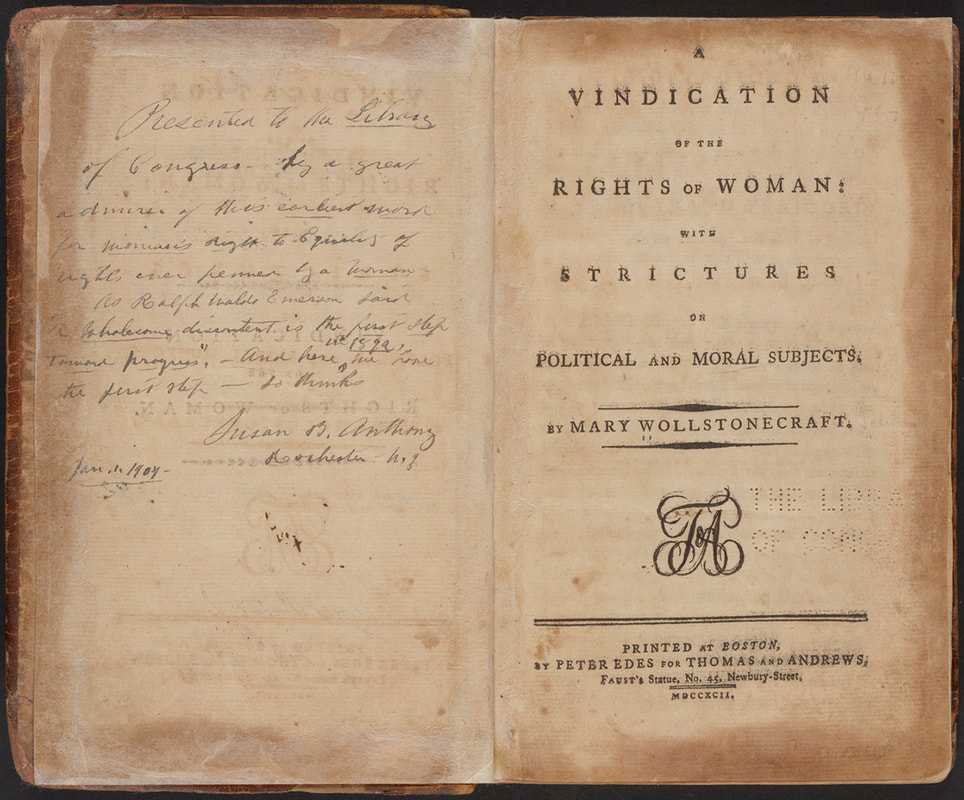

Mary Wollstonecraft, an Enlightenment thinker and writer, was in Paris at the time of the Revolution. Wollstonecraft had been inspired by the French revolutionary ideals and had long been corresponding with other Enlightenment thinkers in Europe. She was a well-known and respected writer inspired by de Gouges and horrified when de Gouges was executed. She promptly fled France and began an exploration of her own ideas concerning the rights of women in society. Her book, the Vindication of the Rights of Woman, eventually became one of the most well-known pieces of feminist literature in world history.

Her writing was in direct response to a drafted plan for a robust public education system produced by male Revolutionaries in France. The system only barely included women, who as they saw it, only needed a “domestic education” for service in the paternal home. Itn response to the plan, Mary Wollstonecraft wrote her now-famous treatise on women’s rights.. Mary was furious and tired of girls being raised solely for domestic service and the whims of men. She believed, like Olympe, that women deserved to be involved in every aspect of society but could not if they did not receive an education. She noted that women were intentionally and systematically held back by men and then ridiculed by men for then having limitations. She demanded that women deserved an education.

Wolstoncraft also led an unconventional life. Her father had been an abuser, and she spent her childhood protecting her mother and younger sisters. But in her thirties she fell madly in love with a 51-year-old Swiss artist who was, unfortunately, married. He rejected her and returned with his wife. She moved to Paris where she again fell in love with an American schemer and philanderer. With him, she had a daughter. Only months after her birth he left to go to England. Following him there, Mary found he had taken up with another woman. In despair, she even attempted to commit suicide twice, once throwing herself into the Thames river. But soon after, she met a writer and philosopher William Goodwin who gave her the love and partnership she had long desired. Together they had a daughter named Mary, but just days later adult Mary died from a ruptured placenta.

After her death, her lover published her biography, unintentionally exposing some of the more scandalous aspects of her life. Those who had previously supported her ideas now rejected her fully. It’s one thing to envision women voting, it’s another to envision women being “sexually promiscuous,” as they saw it.

Mary Wollstonecraft, an Enlightenment thinker and writer, was in Paris at the time of the Revolution. Wollstonecraft had been inspired by the French revolutionary ideals and had long been corresponding with other Enlightenment thinkers in Europe. She was a well-known and respected writer inspired by de Gouges and horrified when de Gouges was executed. She promptly fled France and began an exploration of her own ideas concerning the rights of women in society. Her book, the Vindication of the Rights of Woman, eventually became one of the most well-known pieces of feminist literature in world history.

Her writing was in direct response to a drafted plan for a robust public education system produced by male Revolutionaries in France. The system only barely included women, who as they saw it, only needed a “domestic education” for service in the paternal home. Itn response to the plan, Mary Wollstonecraft wrote her now-famous treatise on women’s rights.. Mary was furious and tired of girls being raised solely for domestic service and the whims of men. She believed, like Olympe, that women deserved to be involved in every aspect of society but could not if they did not receive an education. She noted that women were intentionally and systematically held back by men and then ridiculed by men for then having limitations. She demanded that women deserved an education.

Wolstoncraft also led an unconventional life. Her father had been an abuser, and she spent her childhood protecting her mother and younger sisters. But in her thirties she fell madly in love with a 51-year-old Swiss artist who was, unfortunately, married. He rejected her and returned with his wife. She moved to Paris where she again fell in love with an American schemer and philanderer. With him, she had a daughter. Only months after her birth he left to go to England. Following him there, Mary found he had taken up with another woman. In despair, she even attempted to commit suicide twice, once throwing herself into the Thames river. But soon after, she met a writer and philosopher William Goodwin who gave her the love and partnership she had long desired. Together they had a daughter named Mary, but just days later adult Mary died from a ruptured placenta.

After her death, her lover published her biography, unintentionally exposing some of the more scandalous aspects of her life. Those who had previously supported her ideas now rejected her fully. It’s one thing to envision women voting, it’s another to envision women being “sexually promiscuous,” as they saw it.

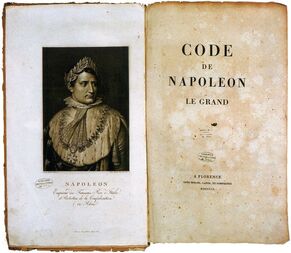

Code de Napoleon, Boston University

Code de Napoleon, Boston University

Napoleon

The French Revolution failed to establish a lasting democracy.. Soon after the Reign of Terror, Napoleon rose to power and imposed himself as an Emperor. His rule involved the conquest of most of Europe, but it was short-lived. He was eventually exiled. But his lasting legacy on the world was his code for women no less.

While still in power, Napoleon introduced “The Code of Napoleon,'' which included a list of the husband’s rights as the head of household and officially extended men’s power over women. It itemized the financial, political, and social ways women had to defer to their husbands' express will. The Code made feminist visions almost impossible to realize for French women for generations to come. Freedoms women had held under the monarchy disappeared. The Napoleonic Code spread across Europe and became the model in the colonies and territories held by European countries.

The French Revolution failed to establish a lasting democracy.. Soon after the Reign of Terror, Napoleon rose to power and imposed himself as an Emperor. His rule involved the conquest of most of Europe, but it was short-lived. He was eventually exiled. But his lasting legacy on the world was his code for women no less.

While still in power, Napoleon introduced “The Code of Napoleon,'' which included a list of the husband’s rights as the head of household and officially extended men’s power over women. It itemized the financial, political, and social ways women had to defer to their husbands' express will. The Code made feminist visions almost impossible to realize for French women for generations to come. Freedoms women had held under the monarchy disappeared. The Napoleonic Code spread across Europe and became the model in the colonies and territories held by European countries.

Liberty Leads Revolutionaries, Public Domain

Liberty Leads Revolutionaries, Public Domain

Conclusion

One has to remember the ironic slogan of the male French revolutionaries: “Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity” or brotherhood. In the case of the French Revolution, Society was not inclusive. Despite women playing a central role in the Revolution itself, the men of the revolutionary era maintained a negative view of women. The Marquis de Sade, for example, wrote, “Our so-called chivalry, derives from the fear of witches that once plagued our endurant ancestors. Their terror was transmuted… into respect but… such respect is fundamentally unnatural since nature nowhere gives a single instance of it. The natural inferiority of women to men is universally evident, and nothing intrinsic to the female sex naturally inspires respect.”

Historian Rosalind Miles asked, “Whose revolution was it anyway?” Her answer? “So what if the women of France had marched with them and even ahead of them, had fought and died with them from the start? The revolution was men’s business, and always would be.” Despite all of the political clubs, freethinking, and enlightened minds, The male vision of equality stopped short of sexual equality. Instead, real women were passed over for the ideal woman.

Delacroix’s painting, “Liberty Leading the People” was completed in 1831. It’s not a product of the French Revolution but of the Revolution of 1830.

But women were able to be read around the world. American suffragists led by Elizabeth Cady Stanton adopted the model of de Gouges and Wollstonecraft in crafting their own document, the Declaration of Sentiments, whose template was copied from the Declaration of Independence in a nod to de Gouges.

By 1900, almost every country in the Americas and Oceania had been liberated from their European colonizer using the justification of Enlightenment thinking and representation. But not one of these countries ensured female suffrage. And many of these countries have yet to see a female head of state or government

To their credit, western nations were some of the first to extend the right to vote to women. One of the biggest reasons was the Enlightenment emphasis on critical thinking. Confucian countries, in the same time period saw a resurgence of Confucian thinking, putting emphasis on teaching ancient texts rather than new ideas. Similarly, in Muslim countries emphasis on Quranic studies limited the spawning of new ideas, as well as women’s opportunities.

By the end of the revolutionary era, so much remained in question. When would male views of women change substantially? Could they be changed? Would women remain in a constant cycle of revolutions that relied on female leadership and ultimately denied them liberty?

One has to remember the ironic slogan of the male French revolutionaries: “Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity” or brotherhood. In the case of the French Revolution, Society was not inclusive. Despite women playing a central role in the Revolution itself, the men of the revolutionary era maintained a negative view of women. The Marquis de Sade, for example, wrote, “Our so-called chivalry, derives from the fear of witches that once plagued our endurant ancestors. Their terror was transmuted… into respect but… such respect is fundamentally unnatural since nature nowhere gives a single instance of it. The natural inferiority of women to men is universally evident, and nothing intrinsic to the female sex naturally inspires respect.”

Historian Rosalind Miles asked, “Whose revolution was it anyway?” Her answer? “So what if the women of France had marched with them and even ahead of them, had fought and died with them from the start? The revolution was men’s business, and always would be.” Despite all of the political clubs, freethinking, and enlightened minds, The male vision of equality stopped short of sexual equality. Instead, real women were passed over for the ideal woman.

Delacroix’s painting, “Liberty Leading the People” was completed in 1831. It’s not a product of the French Revolution but of the Revolution of 1830.

But women were able to be read around the world. American suffragists led by Elizabeth Cady Stanton adopted the model of de Gouges and Wollstonecraft in crafting their own document, the Declaration of Sentiments, whose template was copied from the Declaration of Independence in a nod to de Gouges.

By 1900, almost every country in the Americas and Oceania had been liberated from their European colonizer using the justification of Enlightenment thinking and representation. But not one of these countries ensured female suffrage. And many of these countries have yet to see a female head of state or government

To their credit, western nations were some of the first to extend the right to vote to women. One of the biggest reasons was the Enlightenment emphasis on critical thinking. Confucian countries, in the same time period saw a resurgence of Confucian thinking, putting emphasis on teaching ancient texts rather than new ideas. Similarly, in Muslim countries emphasis on Quranic studies limited the spawning of new ideas, as well as women’s opportunities.

By the end of the revolutionary era, so much remained in question. When would male views of women change substantially? Could they be changed? Would women remain in a constant cycle of revolutions that relied on female leadership and ultimately denied them liberty?

Draw your own conclusions

|

Learn how to teach with inquiry.

Many of these lesson plans were sponsored in part by the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources Eastern Region Program, coordinated by Waynesburg University, the History and Social Studies Education Faculty at Plymouth State University, and the Patrons of the Remedial Herstory Project. |

|

How were women Enlightenment thinkers received in their time? What are the western woman's "Founding Documents"? What issues remain problems for women?

In this lesson, students examine writings from Olympe de Gouge, Mary Wollstonecraft, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton as well as primary source responses and secondary source explanations of how these documents were received to draw conclusions about Enlightenment perspectives on women's rights.

| |||

Lesson Plans from Other Organizations

- This website, Women in World History has primary source based lesson plans on women's history in a whole range of topics. Some are free while others have a cost.

- The Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media has produced recommendations for teaching women's history with primary sources and provided a collection of sources for world history. Check them out!

- The Stanford History Education Group has a number of lesson plans about women in World History.

Olympe De Gouges: Excerpt from "Declaration of the Rights of Woman and Citizen"

Mothers, daughters, sisters, female representatives of the nation ask to be constituted [established] as a national assembly. Considering that ignorance, neglect, or contempt for the rights of woman are the sole causes of public misfortunes and governmental corruption, they have resolved to set forth in a solemn declaration [a serious statement that] the natural, inalienable [absolute], and sacred rights of woman: so that by being constantly present to all the members of the social body this declaration [announcement] may always remind them of their rights and duties; so that by being liable [responsible] at every moment to comparison with the aim of any and all political institutions the acts of women’s and men’s powers may be the more fully respected; and so that by being founded henceforward [going forward] on simple and incontestable [undeniable] principles the demands of the citizenesses may always tend toward maintaining the constitution, good morals, and the general welfare. In consequence, the sex that is superior in beauty as in courage, needed in maternal sufferings, recognizes and declares, in the presence and under the auspices [with the support] of the Supreme Being, the following rights of woman and the citizeness.

1. Woman is born free and remains equal to man in rights. Social distinctions may be based only on common utility.

2. The purpose of all political association is the preservation of the natural and imprescriptible [unable to be taken away] rights of woman and man. These rights are liberty, property, security, and especially resistance to oppression.

3. The principle of all sovereignty [power] rests essentially in the nation, which is but the reuniting of woman and man. No body and no individual may exercise authority which does not emanate [come] expressly from the nation.

4. Liberty and justice consist in restoring all that belongs to another; hence the exercise of the natural rights of woman has no other limits than those that the perpetual tyranny [complete authority] of man opposes to them; these limits must be reformed according to the laws of nature and reason.

5. The laws of nature and reason prohibit [forbid] all actions which are injurious [harmful] to society. No hindrance [barrier] should be put in the way of anything not prohibited by these wise and divine laws, nor may anyone be forced to do what they do not require.

6. The law should be the expression of the general will. All citizenesses and citizens should take part, in person or by their representatives, in its formation. It must be the same for everyone. All citizenesses and citizens, being equal in its eyes, should be equally admissible to all public dignities, offices and employments, according to their ability, and with no other distinction than that of their virtues and talents.

7. No woman is exempted; she is indicted, arrested, and detained in the cases determined by the law. Women like men obey this rigorous law.

8. Only strictly and obviously necessary punishments should be established by the law, and no one may be punished except by virtue of a law established and promulgated [made public] before the time of the offense, and legally applied to women.

9. Any woman being declared guilty, all rigor [strictness] is exercised by the law.

10. No one should be disturbed for his fundamental opinions; woman has the right to mount the scaffold, so she should have the right equally to mount the rostrum [platform], provided that these manifestations [actions] do not trouble public order as established by law.

11. The free communication of thoughts and opinions is one of the most precious of the rights of woman, since this liberty [freedom] assures the recognition of children by their fathers. Every citizeness may therefore say freely, I am the mother of your child; a barbarous prejudice [against unmarried women having children] should not force her to hide the truth, so long as responsibility is accepted for any abuse of this liberty in cases determined by the law [women are not allowed to lie about the paternity of their children].

12. The safeguard of the rights of woman and the citizeness requires public powers. These powers are instituted for the advantage of all and not for the private benefit of those to whom they are entrusted.

13. For maintenance of public authority and for expenses of administration, taxation of women and men is equal; she takes part in all forced labor service, in all painful tasks; she must therefore have the same proportion in the distribution of places, employments, offices, dignities, and in industry.

14. The citizenesses and citizens have the right, by themselves or through their representatives, to have demonstrated to them the necessity of public taxes. The citizenesses can only agree to them upon admission of an equal division, not only in wealth, but also in the public administration, and to determine the means of apportionment, assessment, and collection, and the duration of the taxes.

15. The mass of women, joining with men in paying taxes, have the right to hold accountable every public agent of the administration.

16. Any society in which the guarantee of rights is not assured or the separation of powers not settled has no constitution. The constitution is null and void if the majority of individuals composing the nation has not cooperated in its drafting.

17. Property belongs to both sexes whether united or separated; it is for each of them an inviolable and sacred right, and no one may be deprived of it as a true patrimony of nature, except when public necessity, certified by law, obviously requires it, and then on condition of a just compensation in advance.

Women, wake up; the tocsin [signal] of reason sounds throughout the universe; recognize your rights. The powerful empire of nature is no longer surrounded by prejudice [prejudgement], fanaticism [extremeness/madness]], superstition, and lies. The torch of truth has dispersed [scattered] all the clouds of folly and usurpation [wrongful possession of authority]. Enslaved man has multiplied his force and needs yours to break his chains. Having become free, he has become unjust toward his companion. Oh women! Women, when will you cease to be blind? What advantages have you gathered in the Revolution? A scorn more marked, a disdain more conspicuous [clear]. During the centuries of corruption you only reigned over the weakness of men. Your empire is destroyed; what is left to you then? Firm belief in the injustices of men. The reclaiming of your patrimony [father’s inheritance] founded on the wise decrees of nature; why should you fear such a beautiful enterprise? … Whatever the barriers set up against you, it is in your power to overcome them; you only have to want it. Let us pass now to the appalling [horrifying] account of what you have been in society; and since national education is an issue at this moment, let us see if our wise legislators will think sanely about the education of women….

Hunt, Lynn. The French Revolution and human rights: a brief documentary history. Boston: Bedford Books of St. Martin's Press, 1996.

Questions:

1. What are three rights she demands that stand out to you?

2. Is there any language in the text that would rally women?

3. Is there any language in the text that appears anti-men?

4. Why might someone deem this as unpatriotic?

1. Woman is born free and remains equal to man in rights. Social distinctions may be based only on common utility.

2. The purpose of all political association is the preservation of the natural and imprescriptible [unable to be taken away] rights of woman and man. These rights are liberty, property, security, and especially resistance to oppression.

3. The principle of all sovereignty [power] rests essentially in the nation, which is but the reuniting of woman and man. No body and no individual may exercise authority which does not emanate [come] expressly from the nation.

4. Liberty and justice consist in restoring all that belongs to another; hence the exercise of the natural rights of woman has no other limits than those that the perpetual tyranny [complete authority] of man opposes to them; these limits must be reformed according to the laws of nature and reason.

5. The laws of nature and reason prohibit [forbid] all actions which are injurious [harmful] to society. No hindrance [barrier] should be put in the way of anything not prohibited by these wise and divine laws, nor may anyone be forced to do what they do not require.

6. The law should be the expression of the general will. All citizenesses and citizens should take part, in person or by their representatives, in its formation. It must be the same for everyone. All citizenesses and citizens, being equal in its eyes, should be equally admissible to all public dignities, offices and employments, according to their ability, and with no other distinction than that of their virtues and talents.

7. No woman is exempted; she is indicted, arrested, and detained in the cases determined by the law. Women like men obey this rigorous law.

8. Only strictly and obviously necessary punishments should be established by the law, and no one may be punished except by virtue of a law established and promulgated [made public] before the time of the offense, and legally applied to women.

9. Any woman being declared guilty, all rigor [strictness] is exercised by the law.

10. No one should be disturbed for his fundamental opinions; woman has the right to mount the scaffold, so she should have the right equally to mount the rostrum [platform], provided that these manifestations [actions] do not trouble public order as established by law.

11. The free communication of thoughts and opinions is one of the most precious of the rights of woman, since this liberty [freedom] assures the recognition of children by their fathers. Every citizeness may therefore say freely, I am the mother of your child; a barbarous prejudice [against unmarried women having children] should not force her to hide the truth, so long as responsibility is accepted for any abuse of this liberty in cases determined by the law [women are not allowed to lie about the paternity of their children].

12. The safeguard of the rights of woman and the citizeness requires public powers. These powers are instituted for the advantage of all and not for the private benefit of those to whom they are entrusted.

13. For maintenance of public authority and for expenses of administration, taxation of women and men is equal; she takes part in all forced labor service, in all painful tasks; she must therefore have the same proportion in the distribution of places, employments, offices, dignities, and in industry.

14. The citizenesses and citizens have the right, by themselves or through their representatives, to have demonstrated to them the necessity of public taxes. The citizenesses can only agree to them upon admission of an equal division, not only in wealth, but also in the public administration, and to determine the means of apportionment, assessment, and collection, and the duration of the taxes.

15. The mass of women, joining with men in paying taxes, have the right to hold accountable every public agent of the administration.

16. Any society in which the guarantee of rights is not assured or the separation of powers not settled has no constitution. The constitution is null and void if the majority of individuals composing the nation has not cooperated in its drafting.

17. Property belongs to both sexes whether united or separated; it is for each of them an inviolable and sacred right, and no one may be deprived of it as a true patrimony of nature, except when public necessity, certified by law, obviously requires it, and then on condition of a just compensation in advance.

Women, wake up; the tocsin [signal] of reason sounds throughout the universe; recognize your rights. The powerful empire of nature is no longer surrounded by prejudice [prejudgement], fanaticism [extremeness/madness]], superstition, and lies. The torch of truth has dispersed [scattered] all the clouds of folly and usurpation [wrongful possession of authority]. Enslaved man has multiplied his force and needs yours to break his chains. Having become free, he has become unjust toward his companion. Oh women! Women, when will you cease to be blind? What advantages have you gathered in the Revolution? A scorn more marked, a disdain more conspicuous [clear]. During the centuries of corruption you only reigned over the weakness of men. Your empire is destroyed; what is left to you then? Firm belief in the injustices of men. The reclaiming of your patrimony [father’s inheritance] founded on the wise decrees of nature; why should you fear such a beautiful enterprise? … Whatever the barriers set up against you, it is in your power to overcome them; you only have to want it. Let us pass now to the appalling [horrifying] account of what you have been in society; and since national education is an issue at this moment, let us see if our wise legislators will think sanely about the education of women….

Hunt, Lynn. The French Revolution and human rights: a brief documentary history. Boston: Bedford Books of St. Martin's Press, 1996.

Questions:

1. What are three rights she demands that stand out to you?

2. Is there any language in the text that would rally women?

3. Is there any language in the text that appears anti-men?

4. Why might someone deem this as unpatriotic?

Olympe De Gouges: Transcript From Her Trial

The clerk read the act of accusation... “Antoine-Quentin Fouquier-Tinville, public prosecutor before the Revolutionary Tribunal, etc.

States that, by an order of the administrators of police, dated last July 25th, signed Louvet and Baudrais, it was ordered that Marie Olympe de Gouges, widow of Aubry, charged with having composed [written] a work contrary [differing] to the expressed desire of the entire nation, and directed against whoever might propose a form of government other than that of a republic, one and indivisible, be brought to the prison…

From the examination of the documents deposited [put], together with the interrogation of the accused, it follows that… Olympe de Gouges composed [written] and had printed works which can only be considered as an attack on the sovereignty [supreme power] of the people… . . .

The public prosecutor stated next that it is with the most violent indignation [offense] that one hears the de Gouges woman say to men who for the past four years have not stopped making the greatest sacrifices for liberty [freedom]…

There can be no mistaking the perfidious [untrustworthy] intentions of this criminal woman, and her hidden motives, when one observes her in all the works to which, at the very least, she lends her name, calumniating [falsifying/defaming] and spewing out bile [nastiness] in large doses…

When the accused was questioned sharply about when she composed this writing, she replied that it was some time last May, adding that what motivated her was that seeing the storms arising in a large number of départements, and notably in Bordeaux, Lyons, Marseilles, etc., she had the idea of bringing all parties together by leaving them all free in the choice of the kind of government which would be most suitable for them; that furthermore, her intentions had proven that she had in view only the happiness of her country.

Questioned about how it was that she, the accused, who believed herself to be such a good patriot, had been able to develop, in the month of June, means which she called conciliatory [peacebuilding] concerning a fact which could no longer be in question because the people, at that period, had formally pronounced for republican government, one and indivisible, she replied that this was also the [form of government] she had voted for as the preferable one; that for a long while she had professed [declared] only republican sentiments {point of view], as the jurors would be able to convince themselves from her work entitled De l'ésclavage des noirs.

Asked to speak concerning various phrases in the placard [public notice]… she responded… in saying that she was and always had been a good citoyenne [citizen]…

During the resume of the charge brought by the public prosecutor, the accused, with respect to the facts she was hearing articulated against her, never stopped her smirking. Sometimes she shrugged her shoulders; then she clasped her hands and raised her eyes towards the ceiling of the room; then, suddenly, she moved on to an expressive gesture, showing astonishment; then gazing next at the court, she smiled at the spectators, etc.

Here is the judgment rendered against her.

The Tribunal, based on the unanimous declaration of the jury, stating that:

(1) it is a fact that there exist in the case writings tending towards the reestablishment of a power attacking the sovereignty of the people; [and]

(2) that Marie Olympe de Gouges… is proven guilty… condemn[ed] to the punishment of death… and declares the goods of the aforementioned Marie Olympe de Gouges seized for the benefit of the republic. . . .

[G]iven the public declaration made by the aforementioned Marie Olympe de Gouges that she was pregnant, the Tribunal, following the indictment of the public prosecutor, orders that the aforementioned Marie Olympe de Gouges will be seen and visited by the sworn surgeons… to determine the sincerity of her declaration.

[S]he replied: "My enemies will not have the glory of seeing my blood flow. I am pregnant and will bear a citizen or citoyenne for the Republic."

The same day… the health officer, having visited the condemned, recognized that her declaration was false. . . .

The execution took place the next day [13 Brumaire] towards 4 P.M.; while mounting the scaffold [platform], the condemned, looking at the people, cried out: "Children of the Fatherland, you will avenge my death." Universal cries of "Vive la République" were heard among the spectators waving hats in the air.

Levy, Darlene Gay, Harriet Branson Applewhite, and Mary Durham Johnson, Ed and Trans. Women in Revolutionary Paris, 1789–1795, Chicago: University of Illinois, 1979. p.254- 259.

Questions:

1. What crimes did Olympe de Gouges commit?

2. Does it surprise you that her feminism in a time of democratic revolution resulted in her death? Why or why not?

States that, by an order of the administrators of police, dated last July 25th, signed Louvet and Baudrais, it was ordered that Marie Olympe de Gouges, widow of Aubry, charged with having composed [written] a work contrary [differing] to the expressed desire of the entire nation, and directed against whoever might propose a form of government other than that of a republic, one and indivisible, be brought to the prison…

From the examination of the documents deposited [put], together with the interrogation of the accused, it follows that… Olympe de Gouges composed [written] and had printed works which can only be considered as an attack on the sovereignty [supreme power] of the people… . . .

The public prosecutor stated next that it is with the most violent indignation [offense] that one hears the de Gouges woman say to men who for the past four years have not stopped making the greatest sacrifices for liberty [freedom]…

There can be no mistaking the perfidious [untrustworthy] intentions of this criminal woman, and her hidden motives, when one observes her in all the works to which, at the very least, she lends her name, calumniating [falsifying/defaming] and spewing out bile [nastiness] in large doses…

When the accused was questioned sharply about when she composed this writing, she replied that it was some time last May, adding that what motivated her was that seeing the storms arising in a large number of départements, and notably in Bordeaux, Lyons, Marseilles, etc., she had the idea of bringing all parties together by leaving them all free in the choice of the kind of government which would be most suitable for them; that furthermore, her intentions had proven that she had in view only the happiness of her country.

Questioned about how it was that she, the accused, who believed herself to be such a good patriot, had been able to develop, in the month of June, means which she called conciliatory [peacebuilding] concerning a fact which could no longer be in question because the people, at that period, had formally pronounced for republican government, one and indivisible, she replied that this was also the [form of government] she had voted for as the preferable one; that for a long while she had professed [declared] only republican sentiments {point of view], as the jurors would be able to convince themselves from her work entitled De l'ésclavage des noirs.

Asked to speak concerning various phrases in the placard [public notice]… she responded… in saying that she was and always had been a good citoyenne [citizen]…

During the resume of the charge brought by the public prosecutor, the accused, with respect to the facts she was hearing articulated against her, never stopped her smirking. Sometimes she shrugged her shoulders; then she clasped her hands and raised her eyes towards the ceiling of the room; then, suddenly, she moved on to an expressive gesture, showing astonishment; then gazing next at the court, she smiled at the spectators, etc.

Here is the judgment rendered against her.

The Tribunal, based on the unanimous declaration of the jury, stating that:

(1) it is a fact that there exist in the case writings tending towards the reestablishment of a power attacking the sovereignty of the people; [and]

(2) that Marie Olympe de Gouges… is proven guilty… condemn[ed] to the punishment of death… and declares the goods of the aforementioned Marie Olympe de Gouges seized for the benefit of the republic. . . .

[G]iven the public declaration made by the aforementioned Marie Olympe de Gouges that she was pregnant, the Tribunal, following the indictment of the public prosecutor, orders that the aforementioned Marie Olympe de Gouges will be seen and visited by the sworn surgeons… to determine the sincerity of her declaration.

[S]he replied: "My enemies will not have the glory of seeing my blood flow. I am pregnant and will bear a citizen or citoyenne for the Republic."

The same day… the health officer, having visited the condemned, recognized that her declaration was false. . . .

The execution took place the next day [13 Brumaire] towards 4 P.M.; while mounting the scaffold [platform], the condemned, looking at the people, cried out: "Children of the Fatherland, you will avenge my death." Universal cries of "Vive la République" were heard among the spectators waving hats in the air.

Levy, Darlene Gay, Harriet Branson Applewhite, and Mary Durham Johnson, Ed and Trans. Women in Revolutionary Paris, 1789–1795, Chicago: University of Illinois, 1979. p.254- 259.

Questions:

1. What crimes did Olympe de Gouges commit?

2. Does it surprise you that her feminism in a time of democratic revolution resulted in her death? Why or why not?

Mary Wollstonecraft: Vindication of the Rights of Women

If the abstract rights of man will bear discussion and explanation, those of woman ... will not shrink from the same test…

My own sex, I hope, will excuse me, if I treat them like rational creatures…

It is of great importance to observe that the character of every man is, in some degree, formed by his profession…Women are not allowed to have sufficient strength of mind to acquire what really deserves the name of virtue…

The divine right of husbands, like the divine right of kings, may, it is to be hoped, in this enlightened age, be contested without danger…

I very much doubt whether any knowledge can be attained without labor and sorrow. Society is not properly organized which does not compel men and women to discharge their respective duties…

Women ought to have representatives, instead of being arbitrarily [randomly] governed without having any direct share allowed them in the deliberations [discussions] of government. How much more respectable is the woman who earns her own bread by fulfilling any duty, than the most accomplished beauty…

The irregular exercise of parental authority ... injures the mind, and to these irregularities girls are more subject than boys…

If marriage be the cement of society, mankind should all be educated after the same model...

Make women rational creatures, and free citizens, and they will quickly become good wives, and mothers…

From the tyranny of man, I firmly believe, the greater number of female follies [foolishness] proceed. When the mind is not sufficiently opened to take pleasure in reflection, the body will be adorned [enhanced] with sedulous [thorough] care…