14. 900-1200 Women Crusaders and Stabilizers

|

During the Crusades, women took action on the battlefield alongside their male counterparts. In addition, they assumed power in various roles. Their impact on the Crusades was undeniable.

|

Threatened by the growing and vibrant Islamic Empire between 1095 and 1291 CE, the Latin Christian Church based in Rome joined the Eastern Orthodox Church in Constantinople to lead a series of religious wars known as the Crusades. Armies faced off in the Levant, home to many sites revered in the Jewish, Christian, and Islamic religions. There were nine Crusades to the Holy Land during this period, although most historians tend to highlight the first three or four because they were the most significant. As is typical in the study of wars, most scholars focus their attention on the actions of men in their roles as religious or political leaders and as soldiers. However, women took part in the Crusades in a variety of ways, including as leaders and even as soldiers.

The Crusades

In theory, when Pope Urban II issued a call to arms for the First Crusade in 1095, no one expected women to make the trip. Church leaders appealed to women with wealth to fund expeditions and new military orders. By the Second Crusade, some male authorities actively discouraged women from participating, saying that women would hinder the armies on the campaign. However, as going on Crusade offered distinct spiritual benefits, the experience had to be available to any devout Christian. In this respect, the Crusades were a super-pilgrimage, and women had been taking part in pilgrimage for centuries in Europe. Noblewomen looked to their ancestors for inspiration and hoped to leave a legacy to their descendants. Furthermore, medieval society was thought to be represented by three orders: Those who pray, meaning the clergy; those who fight, meaning the nobility; and those who work, meaning everyone else. If being noble meant being willing to fight, then noblewomen had to have a place in that order.

Dozens of women went on Crusades. Matilda of Tuscany never got to go on an official Crusade, but she paved the way for women who did. Matilda had a reputation for military leadership before the Crusades began. She had long been a loyal defender of Pope Gregory VII who had a conflict with the Holy Roman Emperor. Initially, church and civil law prohibited anyone but a secular male warrior from taking up arms. However, anyone could fight, and fighting monks emerged. Like many daughters of feudal lords, Matilda had been trained in strategy, even if she never personally wielded a weapon. Sources say she was a brilliant strategist and that she was passionate about defending holy causes. Matilda was prepared to lead forces against the Turks as early as 1074, when they defeated the Byzantine army at Manzikert. When the first Crusade was announced in 1095, Matilda was still wrangling with the Holy Roman Emperor and his supporters.

The Crusades

In theory, when Pope Urban II issued a call to arms for the First Crusade in 1095, no one expected women to make the trip. Church leaders appealed to women with wealth to fund expeditions and new military orders. By the Second Crusade, some male authorities actively discouraged women from participating, saying that women would hinder the armies on the campaign. However, as going on Crusade offered distinct spiritual benefits, the experience had to be available to any devout Christian. In this respect, the Crusades were a super-pilgrimage, and women had been taking part in pilgrimage for centuries in Europe. Noblewomen looked to their ancestors for inspiration and hoped to leave a legacy to their descendants. Furthermore, medieval society was thought to be represented by three orders: Those who pray, meaning the clergy; those who fight, meaning the nobility; and those who work, meaning everyone else. If being noble meant being willing to fight, then noblewomen had to have a place in that order.

Dozens of women went on Crusades. Matilda of Tuscany never got to go on an official Crusade, but she paved the way for women who did. Matilda had a reputation for military leadership before the Crusades began. She had long been a loyal defender of Pope Gregory VII who had a conflict with the Holy Roman Emperor. Initially, church and civil law prohibited anyone but a secular male warrior from taking up arms. However, anyone could fight, and fighting monks emerged. Like many daughters of feudal lords, Matilda had been trained in strategy, even if she never personally wielded a weapon. Sources say she was a brilliant strategist and that she was passionate about defending holy causes. Matilda was prepared to lead forces against the Turks as early as 1074, when they defeated the Byzantine army at Manzikert. When the first Crusade was announced in 1095, Matilda was still wrangling with the Holy Roman Emperor and his supporters.

Eleanor of Aquitaine, History Extra

Eleanor of Aquitaine, History Extra

Most of the crusaders traveling from Western Europe to the Holy Lands had to pass through the Byzantine capital, Constantinople. Although she was only a child during the First Crusade, Anna Comnena’s historical account is the only source from a Byzantine perspective.

Anna was the daughter of Emperor Alexios I Comnenos, and she wrote a history of his reign after she retired to a monastery in the 1140s. She based her history on eyewitness accounts from members of court and veterans, but she also had access to the Imperial archives. Her work, known as the Alexiad, describes the tension at court over the influx of heavily armed crusaders passing through Byzantine lands. She described both the Latins and the Turks as “barbarians.” She stated that her father did not trust the Turks very much even though he hoped the Franks and Latins would help keep his Empire intact.

One of the most famous women to go on Crusade is Eleanor of Aquitaine. She was the sole heiress to the territory of Aquitaine in southwestern France and was married to the French prince Louis when she was only thirteen or fourteen. In 1147, Eleanor and her husband, who was by then the king of France, together joined the Second Crusade. Louis knelt in the cathedral to “take the cross,” and inspire the faithful of France to join the fight. Eleanor then knelt beside him to take the cross in the name of Aquitaine and call on those loyal to her family. She also inspired numerous noblewomen to accompany their husbands and brothers. The entire entourage was said to be glorious.

However, as the army slowly made its way down the coast towards Antioch, disaster struck. Torrential rains swept away equipment, men, and horses. The terrain was brutal, and supplies ran low. Worse yet, the vanguard under the leadership of Eleanor and two of her noble vassals set up camp farther ahead than Louis and the rest of the army expected them to. The army was unable to catch up before night fell. Turkish forces took advantage of the gap between Eleanor and Louis’ forces, attacking the exhausted army when Eleanor’s guard was too far away to send supplies. After that defeat, the royal couple and what was left of their army returned to the coast to find ships to carry on with the Crusade. They eventually arrived at Antioch, which at the time was ruled by Eleanor’s uncle. Relieved to be among familiar faces and customs, Eleanor seemed happy to settle in for a while, but Louis became jealous and impatient. He forced her to come to Jerusalem with her troops. She did but refused to participate any longer in the war. The Second Crusade ended in humiliation for Louis, and they had their marriage annulled not long after they returned to France. Eleanor’s reputation after the Crusade was a poor one, as many blamed her leadership for the loss.

Anna was the daughter of Emperor Alexios I Comnenos, and she wrote a history of his reign after she retired to a monastery in the 1140s. She based her history on eyewitness accounts from members of court and veterans, but she also had access to the Imperial archives. Her work, known as the Alexiad, describes the tension at court over the influx of heavily armed crusaders passing through Byzantine lands. She described both the Latins and the Turks as “barbarians.” She stated that her father did not trust the Turks very much even though he hoped the Franks and Latins would help keep his Empire intact.

One of the most famous women to go on Crusade is Eleanor of Aquitaine. She was the sole heiress to the territory of Aquitaine in southwestern France and was married to the French prince Louis when she was only thirteen or fourteen. In 1147, Eleanor and her husband, who was by then the king of France, together joined the Second Crusade. Louis knelt in the cathedral to “take the cross,” and inspire the faithful of France to join the fight. Eleanor then knelt beside him to take the cross in the name of Aquitaine and call on those loyal to her family. She also inspired numerous noblewomen to accompany their husbands and brothers. The entire entourage was said to be glorious.

However, as the army slowly made its way down the coast towards Antioch, disaster struck. Torrential rains swept away equipment, men, and horses. The terrain was brutal, and supplies ran low. Worse yet, the vanguard under the leadership of Eleanor and two of her noble vassals set up camp farther ahead than Louis and the rest of the army expected them to. The army was unable to catch up before night fell. Turkish forces took advantage of the gap between Eleanor and Louis’ forces, attacking the exhausted army when Eleanor’s guard was too far away to send supplies. After that defeat, the royal couple and what was left of their army returned to the coast to find ships to carry on with the Crusade. They eventually arrived at Antioch, which at the time was ruled by Eleanor’s uncle. Relieved to be among familiar faces and customs, Eleanor seemed happy to settle in for a while, but Louis became jealous and impatient. He forced her to come to Jerusalem with her troops. She did but refused to participate any longer in the war. The Second Crusade ended in humiliation for Louis, and they had their marriage annulled not long after they returned to France. Eleanor’s reputation after the Crusade was a poor one, as many blamed her leadership for the loss.

Eleanor regained her lands and married the grandson of Henry I of England, Henry Plantagenet, count of Anjou and duke of Normandy. They had eight children all of whom would be entered into political marriages to secure peace and power. Eleanor earned the title “grandmother of Europe” as so many of her descendants ruled. Although they had many children, her new husband was not faithful to her. She instigated a revolt by her sons against her husband. The revolt failed and she was held in captivity until her husband died.

Eleanor’s son, Richard the Lionheart, became king, and Eleanor played a greater political role than ever before. When he led a Crusade to the Holy Land, she kept his kingdom running smoothly and defeated his brothers when they tried to take his crown. He was captured and Eleanor came to save him, collecting his ransom and personally returning him to England. Richard’s brother, John, succeeded him and almost all of his successes could be traced back to his mother. Other women described her as “beautiful and just, imposing and modest, humble and elegant… who surpassed almost all the queens of the world.”

Eleanor’s son, Richard the Lionheart, became king, and Eleanor played a greater political role than ever before. When he led a Crusade to the Holy Land, she kept his kingdom running smoothly and defeated his brothers when they tried to take his crown. He was captured and Eleanor came to save him, collecting his ransom and personally returning him to England. Richard’s brother, John, succeeded him and almost all of his successes could be traced back to his mother. Other women described her as “beautiful and just, imposing and modest, humble and elegant… who surpassed almost all the queens of the world.”

Melisende of Jerusalem's coronation, World History Encyclopedia

Melisende of Jerusalem's coronation, World History Encyclopedia

Women Crusaders

When it came to the crusades, did women actually participate in combat? It seems that some did. Christian male writers debated whether or not women should fight in the Crusades and very few of them broached the topic as it related to combat. One Greek historian from the First Crusade wrote of women among the warriors, noting that they rode on horseback “in the manner of men, not on coverlets side-saddle but unashamedly astride, and bearing lances and weapons as men do.” Islamic sources also confirmed that women were among the combatants. The twelfth century historians Imad ad-Din and Baha ad-Din reported that a noblewoman arrived by sea in 1189 with an escort of 500 knights. She led her army on raids against the Turkish camps. Both historians also wrote of women in armor, wielding weapons, who were not discovered until their armor was removed after death. Baha further commented on the women who would stand on the walls of the city, firing arrows down on their enemies. Perhaps the Christian writers had mixed feelings about women in combat and preferred to focus on their other activities while on Crusade.

Women, children, and men too old to fight accompanied the armies and sought to make themselves useful and worthy of the spiritual benefits that came with participation. They brought water and food to the warriors, offering encouragement and prayers.They dug ditches and cleared rubble. Albert of Aachen reported in 1099 that women helped weave the material needed to build a siege engine. There were also some prostitutes in the mix. But most women, whether Christian or Muslim-, were associated with the vital preparation of food, laundry, and care for the sick and wounded. During the Second Crusade, Louis of France relied on a woman named Hersenda who was identified in other sources as a medical practitioner in Paris. Much medical knowledge passed from Islamic practitioners to Christians, and European medicine expanded its range of knowledge. Trota of Salerno practiced medicine in the south of Italy in the twelfth century; she is often regarded as the first gynaecologist.

From the male Christian point of view, women who ruled were as dangerous a proposition as were women who fought. This led to mixed and contradictory accounts of the women who helped stabilize the Latin States. Alice of Antioch, for example, gained a reputation as an evil and greedy usurper for trying to take over the principality of Antioch. Her husband of four years was killed in 1130 when their daughter, his heir, was only an infant. Alice had support among her vassals, but her father, Baldwin II of Jerusalem, wanted a male regent to run Antioch until the baby Constance grew up. He sent forces to remove Alice from power. She retreated to Latakia and Jabala, cities she had received as dowry upon her marriage. From there, Alice consolidated support and went on to make two more attempts to take over Antioch. During all this time, Alice created the tools of government, appointing a constable and other offices, setting up a scriptorium to handle her decrees and alliances, and establishing a clear court culture. It was all for nothing. Alice finally admitted defeat when Raymond of Poitiers arrived and was chosen as Constance’s consort. Once the heir had a male partner to cement her claim to the principality, all of Alice’s supporters shifted to what seemed like a more stable option.

At the end of the First Crusade, victorious Christian leaders claimed rulership of the Kingdom of Jerusalem and surrounding territories. We call these the Crusader States or the Latin States. These states were regularly involved in continued fighting as the Latins tried to claim more territory and the Islamic leaders sought to reclaim what they had lost. Many male leaders on both sides died in this ongoing conflict, and women became essential for stability in the region. Even leaders from kingdoms that had never recognized a woman’s claim to rule, such as France, supported the right of daughters to inherit their father’s titles. The frequent loss of male guardians also meant that women needed to serve regents and feudal lords. Finally, marital alliances created ties between people from the West and Christian leaders among the Greeks, Syrians, and other areas within the Levant. The existence of stable Latin states made pilgrimage to the Holy Land easier and encouraged even more women to make the journey.

Melisende of Jerusalem, Alice’s sister, had a different fate and much more support for her claim to Jerusalem. Baldwin II had married Melisende to Fulk, the Count of Anjou. Upon Baldwin’s death, Fulk and Melisende ascended to the throne. Together, they resisted one of Alice’s attempts on Antioch and it was Fulk who chose Raymond to marry Constance. However, at Melisende’s request, Fulk agreed to stay out of Alice’s affairs in the future.

In 1143, Fulk died and Melisende remained on the throne. It was under her leadership that the Crusader state of Edessa fell. She sent word to the pope and inspired the call that launched the Second Crusade. In 1150, Melisende had to fight her own son, Baldwin III, to hold onto Jerusalem. She used many of the same tactics Alice had tried, and ultimately settled for serving as a regent while Baldwin was still young or away on campaign. Unlike Alice, Melisende is remembered fondly in the chronicles because of her involvement in the Second Crusade.

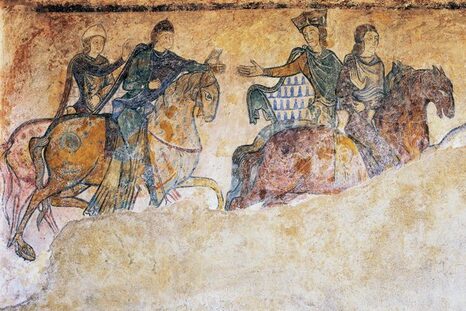

When it came to the crusades, did women actually participate in combat? It seems that some did. Christian male writers debated whether or not women should fight in the Crusades and very few of them broached the topic as it related to combat. One Greek historian from the First Crusade wrote of women among the warriors, noting that they rode on horseback “in the manner of men, not on coverlets side-saddle but unashamedly astride, and bearing lances and weapons as men do.” Islamic sources also confirmed that women were among the combatants. The twelfth century historians Imad ad-Din and Baha ad-Din reported that a noblewoman arrived by sea in 1189 with an escort of 500 knights. She led her army on raids against the Turkish camps. Both historians also wrote of women in armor, wielding weapons, who were not discovered until their armor was removed after death. Baha further commented on the women who would stand on the walls of the city, firing arrows down on their enemies. Perhaps the Christian writers had mixed feelings about women in combat and preferred to focus on their other activities while on Crusade.

Women, children, and men too old to fight accompanied the armies and sought to make themselves useful and worthy of the spiritual benefits that came with participation. They brought water and food to the warriors, offering encouragement and prayers.They dug ditches and cleared rubble. Albert of Aachen reported in 1099 that women helped weave the material needed to build a siege engine. There were also some prostitutes in the mix. But most women, whether Christian or Muslim-, were associated with the vital preparation of food, laundry, and care for the sick and wounded. During the Second Crusade, Louis of France relied on a woman named Hersenda who was identified in other sources as a medical practitioner in Paris. Much medical knowledge passed from Islamic practitioners to Christians, and European medicine expanded its range of knowledge. Trota of Salerno practiced medicine in the south of Italy in the twelfth century; she is often regarded as the first gynaecologist.

From the male Christian point of view, women who ruled were as dangerous a proposition as were women who fought. This led to mixed and contradictory accounts of the women who helped stabilize the Latin States. Alice of Antioch, for example, gained a reputation as an evil and greedy usurper for trying to take over the principality of Antioch. Her husband of four years was killed in 1130 when their daughter, his heir, was only an infant. Alice had support among her vassals, but her father, Baldwin II of Jerusalem, wanted a male regent to run Antioch until the baby Constance grew up. He sent forces to remove Alice from power. She retreated to Latakia and Jabala, cities she had received as dowry upon her marriage. From there, Alice consolidated support and went on to make two more attempts to take over Antioch. During all this time, Alice created the tools of government, appointing a constable and other offices, setting up a scriptorium to handle her decrees and alliances, and establishing a clear court culture. It was all for nothing. Alice finally admitted defeat when Raymond of Poitiers arrived and was chosen as Constance’s consort. Once the heir had a male partner to cement her claim to the principality, all of Alice’s supporters shifted to what seemed like a more stable option.

At the end of the First Crusade, victorious Christian leaders claimed rulership of the Kingdom of Jerusalem and surrounding territories. We call these the Crusader States or the Latin States. These states were regularly involved in continued fighting as the Latins tried to claim more territory and the Islamic leaders sought to reclaim what they had lost. Many male leaders on both sides died in this ongoing conflict, and women became essential for stability in the region. Even leaders from kingdoms that had never recognized a woman’s claim to rule, such as France, supported the right of daughters to inherit their father’s titles. The frequent loss of male guardians also meant that women needed to serve regents and feudal lords. Finally, marital alliances created ties between people from the West and Christian leaders among the Greeks, Syrians, and other areas within the Levant. The existence of stable Latin states made pilgrimage to the Holy Land easier and encouraged even more women to make the journey.

Melisende of Jerusalem, Alice’s sister, had a different fate and much more support for her claim to Jerusalem. Baldwin II had married Melisende to Fulk, the Count of Anjou. Upon Baldwin’s death, Fulk and Melisende ascended to the throne. Together, they resisted one of Alice’s attempts on Antioch and it was Fulk who chose Raymond to marry Constance. However, at Melisende’s request, Fulk agreed to stay out of Alice’s affairs in the future.

In 1143, Fulk died and Melisende remained on the throne. It was under her leadership that the Crusader state of Edessa fell. She sent word to the pope and inspired the call that launched the Second Crusade. In 1150, Melisende had to fight her own son, Baldwin III, to hold onto Jerusalem. She used many of the same tactics Alice had tried, and ultimately settled for serving as a regent while Baldwin was still young or away on campaign. Unlike Alice, Melisende is remembered fondly in the chronicles because of her involvement in the Second Crusade.

Sybyalla of Jerusalem, Getty Images

Sybyalla of Jerusalem, Getty Images

The family drama continued into the next generation of the royal family. Melisende’s son, Count Almaric of Jaffa, married Agnes of Courtenay, a Frankish Countess born in Edessa. Almaric was not initially meant to take the throne in Jerusalem, but after Baldwin III died, he became king. In 1161, the High Court of Jerusalem rejected Agnes as queen. Since Edessa had fallen to Turkish forces, Agnes was no longer politically useful. The High Court forced Alaric to annul their marriage, although they agreed to recognize Agnes’ children as legitimate heirs. The children, Baldwin the IV and Sibyalla, were raised in separate courts. When Baldwin took the throne, his mother joined him in Jerusalem and accompanied him on military campaigns. She did so in part because he had leprosy and was losing his eyesight. Baldwin trusted his mother and even appointed her to choose the Latin patriarch in Jerusalem. Since he had no heirs of his own, Baldwin oversaw the second marriage of his sister Sibyalla. A rival had paired her with someone else in order to undermine Baldwin, but Sibyalla’s first husband died when she was pregnant with her first child. She joined her brother and mother in Jerusalem.

Over time, Sibyalla’s brother, Baldwin, grew to distrust her and her husband. He named Sibyalla’s son as his heir and appointed a regent to rule while the child was young. Baldwin died and the child died soon after. Sibyalla swiftly claimed the throne for herself. She ruled Jerusalem alongside her husband. In theory, they ruled from 1186 to 1190. However, the Third Crusade began under their reign and they lost the city of Jerusalem in 1187. The chaos among the Latin rulers was not lost on Islamic leaders and Saladin, a Kurdish leader, took advantage. Sibyalla died of illness in Acre while it was under siege. Although the early queens of the Latin states had brought stability, the last generation was just as enmeshed in politics as the noblemen.

The women of the Islamic world in the age of the Crusades left a similarly impressive legacy. The Seljuk Turks and the later Ottomans were descended from a central Asian federation of Turkish tribes. Their pre-Islamic epic stories included many heroic women. Even after they accepted Islam, they maintained a tradition of unveiled women attending ceremonies with men. They were culturally very different from many Arabic and Persian Muslims who tended to keep women and men separate and expected women to remain veiled outside their homes. Nevertheless, when it came to defending their homes from invaders, Muslim women from across the cultural spectrum rose to the task. The Frankish writer Guibert noted in Antioch in 1097 that women rode onto the battlefield with the men, often carrying stores of arrows and quivers. Another chronicle reported that two women attempted to interfere with the crusaders’ siege machine but were crushed in the attempt.

Sadly, most accounts of the fate of Muslim and Jewish women in the Holy Lands are descriptions of the wholesale slaughter of women and men or of the enslavement of young women. War is cruel, and local women suffered tremendously. When the Latins stayed to occupy the territory after the First Crusade, non-noble men were said to have taken Syrian, Armenian, and even Muslim women as wives and the Latin church approved as long as those women agreed to convert to Christianity. Such marital alliances helped to stabilize the region as the royal and noble marriages had done in previous centuries..

There are fewer tales of women who ruled during this era of Islamic history, but there were certainly prominent women in the Levant. Zumurrud of Damascus was a noblewoman and a contemporary of Melisende of Jerusalem. She was the mother of the lord of Damascus, Isma’il. When her son proved to be a cruel and greedy ruler, she had him assassinated and put his corpse on display. Zumurrud already had a reputation for running the territory behind the scenes, and now she was the kingmaker. She placed another of her sons on the throne after ruling as regent for a couple of years. Zumurrud was one of the only Muslim women to have received an oath of loyalty from her people, and she ruled with the blessing of the Caliph. She went on to marry the Turkic atabeg Zengi, who himself was the bane of the Latin kings and queens of Jerusalem. Like Melisende, Zumurrud was a patron of the arts and religion. While Melisende had paid to expand the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, Zumurrud built the Madrasa Khatuniyya in Damascus. Other noblewomen among the Turks and Kurds were known to have played prominent roles, but sadly many of their names have been lost.

Did the women who went on the Crusades help to shape the Middle East after the wars were over? Did they break the rules, or did they fulfill their proper calling? Did their presence among the Crusaders help achieve success or cause more problems? And how did women in positions of authority compare to male rulers—were they forces of stability or just as likely as men were to start trouble?

Over time, Sibyalla’s brother, Baldwin, grew to distrust her and her husband. He named Sibyalla’s son as his heir and appointed a regent to rule while the child was young. Baldwin died and the child died soon after. Sibyalla swiftly claimed the throne for herself. She ruled Jerusalem alongside her husband. In theory, they ruled from 1186 to 1190. However, the Third Crusade began under their reign and they lost the city of Jerusalem in 1187. The chaos among the Latin rulers was not lost on Islamic leaders and Saladin, a Kurdish leader, took advantage. Sibyalla died of illness in Acre while it was under siege. Although the early queens of the Latin states had brought stability, the last generation was just as enmeshed in politics as the noblemen.

The women of the Islamic world in the age of the Crusades left a similarly impressive legacy. The Seljuk Turks and the later Ottomans were descended from a central Asian federation of Turkish tribes. Their pre-Islamic epic stories included many heroic women. Even after they accepted Islam, they maintained a tradition of unveiled women attending ceremonies with men. They were culturally very different from many Arabic and Persian Muslims who tended to keep women and men separate and expected women to remain veiled outside their homes. Nevertheless, when it came to defending their homes from invaders, Muslim women from across the cultural spectrum rose to the task. The Frankish writer Guibert noted in Antioch in 1097 that women rode onto the battlefield with the men, often carrying stores of arrows and quivers. Another chronicle reported that two women attempted to interfere with the crusaders’ siege machine but were crushed in the attempt.

Sadly, most accounts of the fate of Muslim and Jewish women in the Holy Lands are descriptions of the wholesale slaughter of women and men or of the enslavement of young women. War is cruel, and local women suffered tremendously. When the Latins stayed to occupy the territory after the First Crusade, non-noble men were said to have taken Syrian, Armenian, and even Muslim women as wives and the Latin church approved as long as those women agreed to convert to Christianity. Such marital alliances helped to stabilize the region as the royal and noble marriages had done in previous centuries..

There are fewer tales of women who ruled during this era of Islamic history, but there were certainly prominent women in the Levant. Zumurrud of Damascus was a noblewoman and a contemporary of Melisende of Jerusalem. She was the mother of the lord of Damascus, Isma’il. When her son proved to be a cruel and greedy ruler, she had him assassinated and put his corpse on display. Zumurrud already had a reputation for running the territory behind the scenes, and now she was the kingmaker. She placed another of her sons on the throne after ruling as regent for a couple of years. Zumurrud was one of the only Muslim women to have received an oath of loyalty from her people, and she ruled with the blessing of the Caliph. She went on to marry the Turkic atabeg Zengi, who himself was the bane of the Latin kings and queens of Jerusalem. Like Melisende, Zumurrud was a patron of the arts and religion. While Melisende had paid to expand the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, Zumurrud built the Madrasa Khatuniyya in Damascus. Other noblewomen among the Turks and Kurds were known to have played prominent roles, but sadly many of their names have been lost.

Did the women who went on the Crusades help to shape the Middle East after the wars were over? Did they break the rules, or did they fulfill their proper calling? Did their presence among the Crusaders help achieve success or cause more problems? And how did women in positions of authority compare to male rulers—were they forces of stability or just as likely as men were to start trouble?

Draw your own conclusions

|

Learn how to teach with inquiry.

Many of these lesson plans were sponsored in part by the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources Eastern Region Program, coordinated by Waynesburg University, the History and Social Studies Education Faculty at Plymouth State University, and the Patrons of the Remedial Herstory Project. |

Lesson Plans from Other Organizations

- This website, Women in World History has primary source based lesson plans on women's history in a whole range of topics. Some are free while others have a cost.

- The Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media has produced recommendations for teaching women's history with primary sources and provided a collection of sources for world history. Check them out!

- The Stanford History Education Group has a number of lesson plans about women in World History.

The Book of Husbandry: What Works a Wife Should Do in General

This selection comes from a reprint of the 1534 edition of The Book of Husbandry, written by one “Master

Fitzherbert.” The book (likely) first appeared in the 1520’s, and the identity of the author is debated. In this

text, “husbandry” refers to farming and other agricultural activities at this time, but the book also

considers religion and social etiquette. The extract below considers some of the roles women played in the

life of a Tudor farm, as well as demonstrates the male author’s opinion on what a woman should be doing.

Please note that the English language here has been modernized.

It is convenient for a husband to have sheep of his own, for many causes, and then may his wife

have part of the wool, to make her husband and her-selfe some clothes. And at the least way, she may

have the locks of the sheep, either to make clothes or blankets or coverlets, or both. And if she have not

wool of her own, she may take wool to spin of clothmakers, and by that means she may have a convenient

living, and many times to do other works. It is a wife’s occupation, to winnow all manner of corn, to make

malt, to wash and wringe, to make hay, shear corn, and in time of need to help her husband to fill the

muck wagon or dung cart, drive the plough, to load hay, corn, and such other. And to go or ride to the

market, to sell butter, cheese, milk, eggs, chickens, capons [a type of poultry], hens, pigs, geese, and all

manner of corn. And also to buy all manner of necessary things belonging to household...

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Book of Husbandry by Master Fitzherbert (1534)

Questions:

Fitzherbert.” The book (likely) first appeared in the 1520’s, and the identity of the author is debated. In this

text, “husbandry” refers to farming and other agricultural activities at this time, but the book also

considers religion and social etiquette. The extract below considers some of the roles women played in the

life of a Tudor farm, as well as demonstrates the male author’s opinion on what a woman should be doing.

Please note that the English language here has been modernized.

It is convenient for a husband to have sheep of his own, for many causes, and then may his wife

have part of the wool, to make her husband and her-selfe some clothes. And at the least way, she may

have the locks of the sheep, either to make clothes or blankets or coverlets, or both. And if she have not

wool of her own, she may take wool to spin of clothmakers, and by that means she may have a convenient

living, and many times to do other works. It is a wife’s occupation, to winnow all manner of corn, to make

malt, to wash and wringe, to make hay, shear corn, and in time of need to help her husband to fill the

muck wagon or dung cart, drive the plough, to load hay, corn, and such other. And to go or ride to the

market, to sell butter, cheese, milk, eggs, chickens, capons [a type of poultry], hens, pigs, geese, and all

manner of corn. And also to buy all manner of necessary things belonging to household...

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Book of Husbandry by Master Fitzherbert (1534)

Questions:

- What roles did women play on a farm?

- Is it different than what you had thought?

Christine de Pizan: Excerpts

Christine de Pizan was an Italian writer and poet during the Medieval Ages. Her most notable works

include “The City of Ladies” and “Three Virtues,” in which she describes and defends the role of women in

society.

One day I was surrounded by books of all kinds... my mind dwelt at length on the

opinions of various authors whom I had studied... It made me wonder how it happened that so

many different men - and learned men among them - have been and are so inclined to express...

so many wicked insults about women and their behavior... it seems that they all speak from one

and the same mouth... Thinking deeply about these matters, I began to examine my character

and conduct as a woman and, similarly, I considered other women whose company I frequently

kept, princesses, great ladies, women of the middle and lower classes, who had told me of their

most private and intimate thoughts... No matter how long I studied the problem, I could not see

or realize how their (male writers) claims could be true when compared to the natural behavior

and character of women.

I know a woman today, named Anastasia who is so learned and skilled in painting

manuscript borders and miniature backgrounds that one cannot find an artisan in all the city of

Paris... who can surpass her... People cannot stop talking about her. And I know this from

experience, for she has executed several things for me which stand out among the paintings of

the great masters.

I am amazed by the opinion of some men who claim that they do not want their

daughters or wives to be educated because they would be ruined as a result... Not all men (and

especially the wisest) share the opinion that it is bad for women to be educated. But it is very

true that many foolish men have claimed this because it upset them that women knew more than

they did.

“The Book of the City of Ladies.” Christine de Pisan. 1405.

She (the lady of the manor) should be a good manager, knowledgeable about farming, knowing

in what weather and in what season the fields should be worked... She should often take her

recreation in the fields in order to see how the work is progressing, for there are many who

would willingly stop raking the ground beyond the surface if they thought nobody would

notice.

“Three Virtues.” Christine de Pisan. 1406.

Questions:

include “The City of Ladies” and “Three Virtues,” in which she describes and defends the role of women in

society.

One day I was surrounded by books of all kinds... my mind dwelt at length on the

opinions of various authors whom I had studied... It made me wonder how it happened that so

many different men - and learned men among them - have been and are so inclined to express...

so many wicked insults about women and their behavior... it seems that they all speak from one

and the same mouth... Thinking deeply about these matters, I began to examine my character

and conduct as a woman and, similarly, I considered other women whose company I frequently

kept, princesses, great ladies, women of the middle and lower classes, who had told me of their

most private and intimate thoughts... No matter how long I studied the problem, I could not see

or realize how their (male writers) claims could be true when compared to the natural behavior

and character of women.

I know a woman today, named Anastasia who is so learned and skilled in painting

manuscript borders and miniature backgrounds that one cannot find an artisan in all the city of

Paris... who can surpass her... People cannot stop talking about her. And I know this from

experience, for she has executed several things for me which stand out among the paintings of

the great masters.

I am amazed by the opinion of some men who claim that they do not want their

daughters or wives to be educated because they would be ruined as a result... Not all men (and

especially the wisest) share the opinion that it is bad for women to be educated. But it is very

true that many foolish men have claimed this because it upset them that women knew more than

they did.

“The Book of the City of Ladies.” Christine de Pisan. 1405.

She (the lady of the manor) should be a good manager, knowledgeable about farming, knowing

in what weather and in what season the fields should be worked... She should often take her

recreation in the fields in order to see how the work is progressing, for there are many who

would willingly stop raking the ground beyond the surface if they thought nobody would

notice.

“Three Virtues.” Christine de Pisan. 1406.

Questions:

- Why did Christine believe women weren’t educated in 1405 in Italy?

- What talents has she witnessed in other women?

- What role did women play in business at this time?

Queen Mary I Of England: Act Concerning the Regal Power

An act declared by Queen Mary I of England, which made it legal for women to have sole ruling power as

the Queen. Mary began her rule in 1553 after the death of her brother, Edward VI, left no male heir to the

English throne. Female rule was considered with suspicion, and Mary’s marriage also caused concern.

Shortly after her accession, she married Prince Philip of Spain (later Philip II). Women were considered

submissive to their husbands; did that mean the Queen would be submissive to her husband in politics,

too? The English government and people became concerned that Philip would seize power, and therefore

Mary was moved to declare her intention to retain the English throne for herself. In this, Mary declares

her right to rule as a woman, and her unwillingness to relinquish her crown to a man, even her husband.

[B]e it declared and enacted by the authority of this present parliament that the law of

this realm is and ever hath been, and ought to be understood, that the kingly or regal office of

the realm, and all dignities [etc.] ... thereunto annexed, united, or belonging, being invested

either in male or female, are and be and ought to be as fully, wholly, absolutely, and entirely

deemed, judged, accepted, invested, and taken in the one as in the other; so that what or

whensoever statute or law doth limit and appoint that the king of this realm may or shall have,

execute, and do anything as king, or doth give any profit or commodity to the king, or doth limit

or appoint any pains or punishment for the correction of offenders or transgressors against the

regality and dignity of the king or of the crown, the same the queen ... may by the same authority

and power likewise have, exercise, execute, punish, correct, and do, to all intents, constructions,

and purposes, without doubt, ambiguity, scruple, or question — any custom, use, or scruple, or

any other thing whatsoever to be made to the contrary notwithstanding.

Queen Mary I, Act Concerning the Regal Power (1554) § (n.d.). https://constitution.org/1-

History/sech/sech_078.htm.

Questions:

the Queen. Mary began her rule in 1553 after the death of her brother, Edward VI, left no male heir to the

English throne. Female rule was considered with suspicion, and Mary’s marriage also caused concern.

Shortly after her accession, she married Prince Philip of Spain (later Philip II). Women were considered

submissive to their husbands; did that mean the Queen would be submissive to her husband in politics,

too? The English government and people became concerned that Philip would seize power, and therefore

Mary was moved to declare her intention to retain the English throne for herself. In this, Mary declares

her right to rule as a woman, and her unwillingness to relinquish her crown to a man, even her husband.

[B]e it declared and enacted by the authority of this present parliament that the law of

this realm is and ever hath been, and ought to be understood, that the kingly or regal office of

the realm, and all dignities [etc.] ... thereunto annexed, united, or belonging, being invested

either in male or female, are and be and ought to be as fully, wholly, absolutely, and entirely

deemed, judged, accepted, invested, and taken in the one as in the other; so that what or

whensoever statute or law doth limit and appoint that the king of this realm may or shall have,

execute, and do anything as king, or doth give any profit or commodity to the king, or doth limit

or appoint any pains or punishment for the correction of offenders or transgressors against the

regality and dignity of the king or of the crown, the same the queen ... may by the same authority

and power likewise have, exercise, execute, punish, correct, and do, to all intents, constructions,

and purposes, without doubt, ambiguity, scruple, or question — any custom, use, or scruple, or

any other thing whatsoever to be made to the contrary notwithstanding.

Queen Mary I, Act Concerning the Regal Power (1554) § (n.d.). https://constitution.org/1-

History/sech/sech_078.htm.

Questions:

- What power did this act give Queen Mary I?

- How did this act work against ideas of the time regarding a woman’s role in marriage?

Maria Theresa: General School Regulations

This order by Maria Theresa, Empress of the Holy Roman Empire, l aimed to reform education within

Austria and her territories. Under these regulations, children of both sexes were required to attend school

between the ages of six and twelve. Although women could be educated before this, requiring girls to go to

school was radical at the time.

We have realized that the education of young people , both sexes, as the most important

basis of the true happiness of the nations, however, demands a more precise level.

This subject attracted our attention all the more, the more certain of a good upbringing,

and leadership in the early years, the whole future way of life of all people, and the education of

genius, and the way of thinking of entire peoples depends, which can never be achieved if the

darkness of ignorance is not cleared up by well-chosen educational and teaching institutions,

and everyone who is given instruction appropriate to his or her status

In order to achieve this necessary, as a mutually beneficial decision, we have found the

current general lane of the Sculoronung to be fixed for all of our German hereditary kingdoms

and countries.

The right to hold schools and to instruct the youth also remains with all those of clerical

and secular status, male and female, who have hitherto been in the same regard; But the schools

have to go arranged altogether in the general established manner, as soon as possible, and in all

matters, without any exception, to depend on the school commission of the province in which

they are located.

Wherever there is opportunity to have their own schools for the maids, they attend them

and, if it is possible, are to be instructed in sewing, knitting and other things appropriate to their

sex; But where there are no separate girls' schools, they have to go to the common school, but not

among the boys, but on their own benches, separated from them, and are instructed with the

boys in the same class, with who at the same time learn everything that is appropriate for their

sex.

Theresa, Maria, General School Regulations for the German Normal, Secondary and Trivial Schools in all

Kaiserl § (n.d.).

Questions:

Austria and her territories. Under these regulations, children of both sexes were required to attend school

between the ages of six and twelve. Although women could be educated before this, requiring girls to go to

school was radical at the time.

We have realized that the education of young people , both sexes, as the most important

basis of the true happiness of the nations, however, demands a more precise level.

This subject attracted our attention all the more, the more certain of a good upbringing,

and leadership in the early years, the whole future way of life of all people, and the education of

genius, and the way of thinking of entire peoples depends, which can never be achieved if the

darkness of ignorance is not cleared up by well-chosen educational and teaching institutions,

and everyone who is given instruction appropriate to his or her status

In order to achieve this necessary, as a mutually beneficial decision, we have found the

current general lane of the Sculoronung to be fixed for all of our German hereditary kingdoms

and countries.

The right to hold schools and to instruct the youth also remains with all those of clerical

and secular status, male and female, who have hitherto been in the same regard; But the schools

have to go arranged altogether in the general established manner, as soon as possible, and in all

matters, without any exception, to depend on the school commission of the province in which

they are located.

Wherever there is opportunity to have their own schools for the maids, they attend them

and, if it is possible, are to be instructed in sewing, knitting and other things appropriate to their

sex; But where there are no separate girls' schools, they have to go to the common school, but not

among the boys, but on their own benches, separated from them, and are instructed with the

boys in the same class, with who at the same time learn everything that is appropriate for their

sex.

Theresa, Maria, General School Regulations for the German Normal, Secondary and Trivial Schools in all

Kaiserl § (n.d.).

Questions:

- What is the goal of the regulations?

- How does this affect women/girls?

- Is there a difference for how boys are to be taught in comparison to girls?

- According to this regulation, what are the long term effects of compulsory [required] education?

Queen Victoria: Excerpts From Letters

Queen Victoria of Great Britain and Ireland (1837-1901) wrote the following two extracts which give her

opinion on women’s “natural” interest and roles. Her husband, Prince Albert, acted as an unofficial co-

ruler during his short life, dying in 1861. Victoria went on to rule for forty years after her husband’s

death, but maintained her staunch beliefs that men were more natural rulers. At times, she expressed

frustration with gender roles, while at others (as viewed in the excerpts below) she accepted and embraced

her lesser position as a fact.

Excerpt #1

“Albert grows daily fonder and fonder of politics and business, and is so wonderfully fit

for both - such perspicacity and such courage - and I grow daily to dislike them more and more.

We women are not made for governing; and, if we were good women, we must dislike those

masculine occupations; but there are times which force one to take interest in them... and I do of

course, intensely.” (1852)

Excerpt #2

“The Queen is most anxious to enlist everyone who can speak or write to join in checking

this mad wicked folly of ‘women's rights’, with all its attendant hours, on which her poor sex is

bent, forgetting every sense of womanly feeling and propriety... God created men and women

different-then let them remain each in their own position.... Woman would become the most

hateful, heatless, and disgusting of human beings were she allowed to unsex herself; and where

would be the protection which man was intended to give the weaker sex?” (1870)

Chernock, Arianne. “Conclusion: Queen Victoria versus the Suffragettes: The Politics of Queenship in Edwardian Britain.” Chapter. In The Right to Rule and the Rights of Women: Queen Victoria and

the Women's Movement, 193–216. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

doi:10.1017/9781108652384.007.

Questions:

opinion on women’s “natural” interest and roles. Her husband, Prince Albert, acted as an unofficial co-

ruler during his short life, dying in 1861. Victoria went on to rule for forty years after her husband’s

death, but maintained her staunch beliefs that men were more natural rulers. At times, she expressed

frustration with gender roles, while at others (as viewed in the excerpts below) she accepted and embraced

her lesser position as a fact.

Excerpt #1

“Albert grows daily fonder and fonder of politics and business, and is so wonderfully fit

for both - such perspicacity and such courage - and I grow daily to dislike them more and more.

We women are not made for governing; and, if we were good women, we must dislike those

masculine occupations; but there are times which force one to take interest in them... and I do of

course, intensely.” (1852)

Excerpt #2

“The Queen is most anxious to enlist everyone who can speak or write to join in checking

this mad wicked folly of ‘women's rights’, with all its attendant hours, on which her poor sex is

bent, forgetting every sense of womanly feeling and propriety... God created men and women

different-then let them remain each in their own position.... Woman would become the most

hateful, heatless, and disgusting of human beings were she allowed to unsex herself; and where

would be the protection which man was intended to give the weaker sex?” (1870)

Chernock, Arianne. “Conclusion: Queen Victoria versus the Suffragettes: The Politics of Queenship in Edwardian Britain.” Chapter. In The Right to Rule and the Rights of Women: Queen Victoria and

the Women's Movement, 193–216. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

doi:10.1017/9781108652384.007.

Questions:

- Compare the tone of the first excerpt to the second.

- In the letter from 1852, what role does she believe women should play in politics?

- Why does Queen Victoria believe that the fight for women's right's is a "mad wicked folly"?

Der Ling: Two Years in the Forbidden City

For two years, Princess Der Ling was the favorite lady-in-waiting to the Empress Dowager Cixi in the imperial palace in Beijing. This book provides a unique and surprisingly intimate portrait of the Dragon Lady, who ruled China for 47 years, and brought the country to the brink of destruction. Der Ling refers to the larger political context on many occasions. But the best parts of the book are the small details. What emerges is an intimate portrait of the life and personality of the Empress Dowager, and a sense of the inner workings of the highly secretive world of the imperial palace.

When I informed Her Majesty of the arrival of the portrait she ordered that it should be

brought into her bedroom immediately. She scrutinized it very carefully for a while, even

touching the painting in her curiosity. Finally she burst out laughing and said: "What a funny

painting this is, it looks as though it had been painted with oil." (Of course it was an oil

painting.) "Such rough work I never saw in all my life. The picture itself is marvelously like you,

and I do not hesitate to say that none of our Chinese painters could get the expression which

appears on this picture. What a funny dress you are wearing in this picture. Why are your arms

and neck all bare? I have heard that foreign ladies wear their dresses without sleeves and

without collars, but I had no idea that it was so bad and ugly as the dress you are wearing here. I

cannot imagine how you could do it. I should have thought you would have been ashamed to

expose yourself in that manner. Don't wear any more such dresses, please. It has quite shocked

me. What a funny kind of civilization this is to be sure. Is this dress only worn on certain

occasions, or is it worn any time, even when gentlemen are present?" I explained to her that it

was the usual evening dress for ladies and was worn at dinners, balls, receptions, etc. Her

Majesty laughed and exclaimed: "This is getting worse and worse. Everything seems to go

backwards in foreign countries. Here we don't even expose our wrists when in the company of

gentlemen, but foreigners seem to have quite different ideas on the subject. The Emperor is

always talking about reform, but if this is a sample we had much better remain as we are. Tell

me, have you yet changed your opinion with regard to foreign customs? Don't you think that

our own customs are much nicer?" Of course I was obliged to say "yes" seeing that she herself

was so prejudiced.

Der Ling. Two Years in the Forbidden City. Project Gutenberg. 1911.

Questions:

When I informed Her Majesty of the arrival of the portrait she ordered that it should be

brought into her bedroom immediately. She scrutinized it very carefully for a while, even

touching the painting in her curiosity. Finally she burst out laughing and said: "What a funny

painting this is, it looks as though it had been painted with oil." (Of course it was an oil

painting.) "Such rough work I never saw in all my life. The picture itself is marvelously like you,

and I do not hesitate to say that none of our Chinese painters could get the expression which

appears on this picture. What a funny dress you are wearing in this picture. Why are your arms

and neck all bare? I have heard that foreign ladies wear their dresses without sleeves and

without collars, but I had no idea that it was so bad and ugly as the dress you are wearing here. I

cannot imagine how you could do it. I should have thought you would have been ashamed to

expose yourself in that manner. Don't wear any more such dresses, please. It has quite shocked

me. What a funny kind of civilization this is to be sure. Is this dress only worn on certain

occasions, or is it worn any time, even when gentlemen are present?" I explained to her that it

was the usual evening dress for ladies and was worn at dinners, balls, receptions, etc. Her

Majesty laughed and exclaimed: "This is getting worse and worse. Everything seems to go

backwards in foreign countries. Here we don't even expose our wrists when in the company of

gentlemen, but foreigners seem to have quite different ideas on the subject. The Emperor is

always talking about reform, but if this is a sample we had much better remain as we are. Tell

me, have you yet changed your opinion with regard to foreign customs? Don't you think that

our own customs are much nicer?" Of course I was obliged to say "yes" seeing that she herself

was so prejudiced.

Der Ling. Two Years in the Forbidden City. Project Gutenberg. 1911.

Questions:

- Who is writing and how does she know the Empress?

- Does the Queen seem open to reforms to women’s dress? Why or why not?

Joan of Arc: Hear the Words of God and the Maid!

This is a letter to the King of England from Joan of Arc. In the letter, Joan refers to herself as “the maid.”

King of England, render account to the King of Heaven of your royal blood. Return the keys of all the good cities which you have seized, to the Maid. She is sent by God to reclaim the royal blood, and is fully prepared to make peace, if you will give her satisfaction; that is, you must render justice, and pay back all that you have taken.

King of England, if you do not do these things, I am the commander of the military; and in whatever place I shall find your men in France, I will make them flee the country, whether they wish to or not; and if they will not obey, the Maid will have them all killed. She comes sent by the King of Heaven, body for body, to take you out of France, and the Maid promises and certifies to you that if you do not leave France she and her troops will raise a mighty outcry as has not been heard in France in a thousand years. And believe that the King of Heaven has sent her so much power that you will not be able to harm her or her brave army.

To you, archers, noble companions in arms, and all people who are before Orleans, I say to you in God's name, go home to your own country; if you do not do so, beware of the Maid, and of the damages you will suffer. Do not attempt to remain, for you have no rights in France from God, the King of Heaven, and the Son of the Virgin Mary. It is Charles, the rightful heir, to whom God has given France, who will shortly enter Paris in a grand company. If you do not believe the news written of God and the Maid, then in whatever place we may find you, we will soon see who has the better right, God or you.

Duke of Bedford, who call yourself regent of France for the King of England, the Maid asks you not to make her destroy you. If you do not render her satisfaction, she and the French will perform the greatest feat ever done in the name of Christianity.

Translated by Belle Tuten from M. Vallet de Vireville, ed. Chronique de la Pucelle, ou Chronique de Cousinot. Paris: Adolphe Delahaye, 1859, pp. 281-283.

Questions:

King of England, render account to the King of Heaven of your royal blood. Return the keys of all the good cities which you have seized, to the Maid. She is sent by God to reclaim the royal blood, and is fully prepared to make peace, if you will give her satisfaction; that is, you must render justice, and pay back all that you have taken.

King of England, if you do not do these things, I am the commander of the military; and in whatever place I shall find your men in France, I will make them flee the country, whether they wish to or not; and if they will not obey, the Maid will have them all killed. She comes sent by the King of Heaven, body for body, to take you out of France, and the Maid promises and certifies to you that if you do not leave France she and her troops will raise a mighty outcry as has not been heard in France in a thousand years. And believe that the King of Heaven has sent her so much power that you will not be able to harm her or her brave army.

To you, archers, noble companions in arms, and all people who are before Orleans, I say to you in God's name, go home to your own country; if you do not do so, beware of the Maid, and of the damages you will suffer. Do not attempt to remain, for you have no rights in France from God, the King of Heaven, and the Son of the Virgin Mary. It is Charles, the rightful heir, to whom God has given France, who will shortly enter Paris in a grand company. If you do not believe the news written of God and the Maid, then in whatever place we may find you, we will soon see who has the better right, God or you.

Duke of Bedford, who call yourself regent of France for the King of England, the Maid asks you not to make her destroy you. If you do not render her satisfaction, she and the French will perform the greatest feat ever done in the name of Christianity.

Translated by Belle Tuten from M. Vallet de Vireville, ed. Chronique de la Pucelle, ou Chronique de Cousinot. Paris: Adolphe Delahaye, 1859, pp. 281-283.

Questions:

- Was Joan of Arc a heretic?

Catherine de Pizan: The Song Of Joan Of Arc

A poem by Catherine de Pizan, France's first woman of letters.

And you, Charles, now the king of France, The seventh king of that great name, Who earlier suffered such mischance; You thought the future held more shame. But by God's grace, now look how Joan Has raised your fame on high, oh see! Your enemies before you bow--

This is a welcome novelty!--

Most quickly worked; one would have thought, That such a deed could not be done,

That all your efforts were for nought,

That France was gone; now it is won. Although you took tremendous harm,

You have your country back in tow,

Won back by wise Joan's mighty arm. Thanks be to God, it happened so!

Translated from the French text in Christine de Pisan, Ditié de Jeanne d'Arc, ed. Angus J. Kennedy and Kenneth Varty (Oxford: Society for the Study of Medieval Languages and Literature, 1977), trans. L. Shopkow.

Questions:

And you, Charles, now the king of France, The seventh king of that great name, Who earlier suffered such mischance; You thought the future held more shame. But by God's grace, now look how Joan Has raised your fame on high, oh see! Your enemies before you bow--

This is a welcome novelty!--

Most quickly worked; one would have thought, That such a deed could not be done,

That all your efforts were for nought,

That France was gone; now it is won. Although you took tremendous harm,

You have your country back in tow,

Won back by wise Joan's mighty arm. Thanks be to God, it happened so!

Translated from the French text in Christine de Pisan, Ditié de Jeanne d'Arc, ed. Angus J. Kennedy and Kenneth Varty (Oxford: Society for the Study of Medieval Languages and Literature, 1977), trans. L. Shopkow.

Questions:

- Was Joan of Arc a heretic?

The Church Of England: The First Trial of Joan of Arc

“We, the judges, say and decree: that you, Joan, have deeply sinned in pretending untruthfully that your revelations and apparitions are of God; in seducing others; in believing lightly and rashly; in making superstitious divinations; in blaspheming God and the Saints; in prevaricating as to the law, Holy Scripture, and the Canonical sanctions; in despising God in His Sacraments; in fomenting seditions and revolts; in apostatizing; in encouraging the crime of heresy; in erring on numerous points in the Catholic Faith.

But because that, after being many times charitably admonished and long waited for, you have at last, with the help of God, returned into the bosom of the Church, your Holy Mother, with contrite heart, and have openly revoked your errors; because, having solemnly and publicly cast these far from you, you have abjured them by the words of your own mouth, together with the heresy with which you were charged: We declare you set free by these presents, according to the form appointed by Ecclesiastical sanction, from the bonds of excommunications which held you enchained, charging you to return to the Church with a true heart and sincere faith, and to observe what has been already enjoined you and what shall yet be enjoined you by us.

But because you have sinned rashly against God and Holy Church, We condemn you, finally, definitely and for salutary penance, saving Our grace and moderation, to perpetual imprisonment, with the bread of sorrow and the water of affliction, in order that you may bewail your faults, and that you may no more commit [acts] which you shall have to bewail hereafter.”

T. Douglas Murray, Jeanne d'Arc (New York: McClure, Phillips & Co, 1902).

Questions:

But because that, after being many times charitably admonished and long waited for, you have at last, with the help of God, returned into the bosom of the Church, your Holy Mother, with contrite heart, and have openly revoked your errors; because, having solemnly and publicly cast these far from you, you have abjured them by the words of your own mouth, together with the heresy with which you were charged: We declare you set free by these presents, according to the form appointed by Ecclesiastical sanction, from the bonds of excommunications which held you enchained, charging you to return to the Church with a true heart and sincere faith, and to observe what has been already enjoined you and what shall yet be enjoined you by us.

But because you have sinned rashly against God and Holy Church, We condemn you, finally, definitely and for salutary penance, saving Our grace and moderation, to perpetual imprisonment, with the bread of sorrow and the water of affliction, in order that you may bewail your faults, and that you may no more commit [acts] which you shall have to bewail hereafter.”

T. Douglas Murray, Jeanne d'Arc (New York: McClure, Phillips & Co, 1902).

Questions:

- Was Joan of Arc deemed a heretic?

Joan of Arc: A Letter Written During her Trial

"For this cause, I, Joan, commonly called the Maid, a miserable sinner, after that I had recognized the snares of error in the which I was held, and [after] that, by the grace of God, I had returned to our Holy Mother Church, in order that it may be seen that, not feigningly but with a good heart and good will, I have returned thereto; I confess that I have most grievously sinned, in pretending untruthfully to have had revelations and apparitions from God... in wearing a dissolute habit, misshapen and immodest and against the propriety of nature, and hair clipped 'en ronde' in the style of a man, against all the modesty of the feminine sex; also, in bearing arms in great presumption; in cruelly desiring the effusion of human blood; in saying that all these things I did by the command of God... I confess also that I have been schismatic and in many ways have erred from the Faith... (Signed thus): Jehanne †."

T. Douglas Murray, Jeanne d'Arc (New York: McClure, Phillips & Co, 1902).

Questions:

T. Douglas Murray, Jeanne d'Arc (New York: McClure, Phillips & Co, 1902).

Questions:

- Does Joan regret her actions? Why might she?

Church of England: Final Trial of Joan of Arc

Afterwards, We, the Bishop and Vicar aforesaid, having regard to all that has gone before, in which it is shown that this woman had never truly abandoned her errors... diabolical obstinacy...

WE DECREE THAT YOU ART A RELAPSED HERETIC... we denounce thee as a rotten member, and that you may not vitiate others, as cast out from the unity of the Church... Here follows the Sentence of Excommunication. . . that you have been on the subject of thy pretended divine revelations and apparitions lying, seducing, and blasphemy towards God and the Saints... WE DECLARE THEE OF RIGHT EXCOMMUNICATE AND HERETIC... We do abandon thee to the secular authority, as a member of Satan.

T. Douglas Murray, Jeanne d'Arc (New York: McClure, Phillips & Co, 1902.

Questions:

WE DECREE THAT YOU ART A RELAPSED HERETIC... we denounce thee as a rotten member, and that you may not vitiate others, as cast out from the unity of the Church... Here follows the Sentence of Excommunication. . . that you have been on the subject of thy pretended divine revelations and apparitions lying, seducing, and blasphemy towards God and the Saints... WE DECLARE THEE OF RIGHT EXCOMMUNICATE AND HERETIC... We do abandon thee to the secular authority, as a member of Satan.

T. Douglas Murray, Jeanne d'Arc (New York: McClure, Phillips & Co, 1902.

Questions:

- Was Joan of Arc a heretic?

Remedial Herstory Editors. "14. 900-1200 WOMEN CRUSADERS AND STABILIZERS " The Remedial Herstory Project. November 1, 2022. www.remedialherstory.com.

Primary AUTHOR: |

Dr. Nancy Locklin-Sofer

|

Primary Reviewer: |

Dr. Katherine Koh

Sara Stone and Lauren Cole |

Consulting Team |

Editors |

|

Kelsie Brook Eckert, Project Director

Coordinator of Social Studies Education at Plymouth State University Dr. Nancy Locklin-Sofer, Consultant Professor of History at Maryville College. Chloe Gardner, Consultant PhD Candidate in Religious Studies at Edinburgh University Dr. Whitney Howarth, Consultant Former Professor of History at Plymouth State University Jacqui Nelson, Consultant Teaching Lecturer of Military History at Plymouth State University Maria Concepcion Marquez Sandoval PhD Candidate in History at Arizona University |

ReviewersAncient:

Dr. Kristin Heineman Professor of History at Colorado State University Dr. Bonnie Rock-McCutcheon Professor of History at Wilson College Sarah Stone PhD Candidate in Religious Studies at Edinburgh University Medieval: Dr. Katherine Koh Professor of History at La Sierra University Dr. Jonathan Couser Professor of History at Plymouth State University Dr. Shahla Haeri Professor of History at Boston University Lauren Cole PhD Candidate in History at Northwestern University Modern: Dr. Barbara Tischler Supervisor for Hunter College Dr. Pamela Scully Professor of Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies and African Studies at Emory University |

|

This book surveys women's involvement in medieval crusading between the second half of the eleventh century, when Pope Gregory VII first proposed a penitential military expedition to help the Christians of the East, and 1570, when the last crusader state, Cyprus, was captured by the Ottoman Turks. It considers women's actions not only on crusade battlefields but also in recruiting crusaders, supporting crusades through patronage, propaganda, and prayer, and as both defenders and aggressors.

Best known today as a fine composer, the twelfth-century German abbess Hildegard of Bingen was also a religious leader and visionary, a poet, naturalist and writer of medical treatises. Despite her cloistered life she had strong, often controversial views on sex, love and marriage too - a woman astonishing in her own age, whose book of apocalyptic visions, Scivias, would alone have been enough to ensure her lasting fame.

This study of the female members of the Order or Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem in the High Middle Ages analyses their presence in the context of female monasticism and compares their position to the position of women in other religious military orders. Introducing questions of gender into the history of the military orders.

|

Defending the City of God explores this fascinating and forgotten world, and how a group of sisters, daughters of the King of Jerusalem, whose supporters included Grand Masters of the Templars and Armenian clerics, held together the fragile treaties, understandings, and marriages that allowed for relative peace among the many different factions. As the crusaders fought to maintain their conquests, these relationships quickly unraveled, and the religious and cultural diversity was lost as hardline factions took over.

For centuries St. Clare of Assisi has been a lesser-known saint simply because she was overshadowed by the giant that is St. Francis. This biography not only tells the story of their intertwined lives, but more importantly highlights the extraordinary contributions Clare made to the Franciscan world following Francis’s death. This book is her story from birth until death in 1253.

In this landmark study, Shahla Haeri offers the extraordinary biographies of several Muslim women rulers and leaders who reached the apex of political systems of their times.

Beginning in seventh-century Mecca and Medina, A History of Islam in 21 Women takes us around the globe, through eleventh-century Yemen and Khorasan, and into sixteenth-century Spain, Istanbul and India. From there to nineteenth-century Persia and the African savannah, to twentieth-century Russia, Turkey, Egypt and Iraq, before reaching present day London.

|

Narratives of crusading have often been overlooked as a source for the history of women because of their focus on martial events, and perceptions about women inhibiting the recruitment and progress of crusading armies. Yet women consistently appeared in the histories of crusade and settlement, performing a variety of roles. While some were vilified as "useless mouths" or prostitutes, others undertook menial tasks for the army, went on crusade with retinuesof their own knights, and rose to political prominence in the Levant and and the West. This book compares perceptions of women from a wide range of historical narratives including those eyewitness accounts, lay histories andmonastic chronicles that pertained to major crusade expeditions and the settler society in the Holy Land.

This work has been selected by scholars as being culturally important and is part of the knowledge base of civilization as we know it. This work was reproduced from the original artifact and remains as true to the original work as possible. Therefore, you will see the original copyright references, library stamps (as most of these works have been housed in our most important libraries around the world), and other notations in the work.

|

|

In Salerno, Kingdom of Sicily, Rebecca pursues her dreams by attending medical school. Practicing her profession, she defies family pressure to marry Rafael, the man who loves her. But more pressing is the conquest of Sicily by the Hohenstaufens and the arrival of rogue crusaders, both of which threaten Salerno’s long-standing atmosphere of tolerance. When a rabbi is falsely accused of murdering a crusader, Rebecca and Rafael commit to pursuing justice and protecting the Jewish community.

|

Feisty and smart, Elvina is not your average twelve-year-old. She adores reading, writing, and studying, like the boys. And she detests silly girls' chores, like keeping chicken eggs warm until they hatch. But she is also skilled in the art of healing, a skill that ultimately gets her into trouble. It's the 11th Century in France, and the Crusaders are on a campaign to rid France of Jews. The Jews live in terror and are on high alert that danger is drawing near to their town. One night, while Elvina is alone in her house, she hears a rap on the door. Can her guardian angel keep her safe?

|

fate? She embarks on a perilous journey to the Holy Land in this enthralling historical epic.

Imprisoned in Damascus, Dragonetz suffers the mind games inflicted by his anonymous enemies, as he is forced to relive the traumatic events of the Second Crusade. His military prowess is as valuable and dangerous to the balance of power as the priceless Torah he has to deliver to Jerusalem, and the key players want Dragonetz riding with them - or dead. |

bibliography

Asbridge, Thomas. “Alice of Antioch: A Case Study of Female Power in the 12th c.” In The Experience of Crusading. Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Cassagnes-Bouquet, Sophie & Michèle Greer. “In the service of the Just War: Matilda of Tuscany.” Clio, No. 39, Gendered laws of war (2014)

Hodgson, Natasha R. Women, Crusading and the Holy Land in Historical Narrative. Boydell Press, 2007.

Kostick, Conor. The Social Structure of the First Crusade. Brill, 2008.

Miles, Rosalind. The Women’s History of the World. London, UK: HarperCollins Publishers, 1988.