13. Women and Industrialization

|

The backbone of every economy is the labor of women, both paid and unpaid. It was the Industrial Revolution, however, that first made this distinction and created a value system that favored "salary" work over unpaid domestic labor. Women's labors varied by class, but women everywhere worked and their work fueled industrialization.

|

Factory Girls, Wikimedia Commons

Factory Girls, Wikimedia Commons

The Second Industrial Revolution began before the Civil War and continued into the 20th century. Women were involved as laborers and investors from the very beginning. Women's jobs varied considerably by race and class. Respectable work was really only available to educated middle class women, which included teaching, writing, and nursing. American women from working class families found gainful employment in factories, thanks to technological innovations that allowed for mass production, especially in the food and textile industries. Factory work sometimes offered higher wages than domestic work, so young women sought factory jobs. This wasn’t always the case though. Some factories paid women very little, so their entire family had to work to survive. Some cities offered better paid jobs as domestics compared to other southern cities, so women did the math and did domestic work. Women of color found limited opportunities for work in the factories, thus they primarily worked in domestic service or owned their own businesses. Although essential to the mills, women were paid less, worked long hours, and efforts to improve their condition were thwarted not only by their bosses and the male dominated government, but also by other male unions that worked to protect their wages at the expense of women workers. But women, of course, fought back.

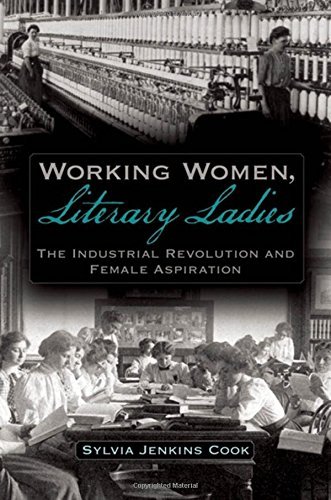

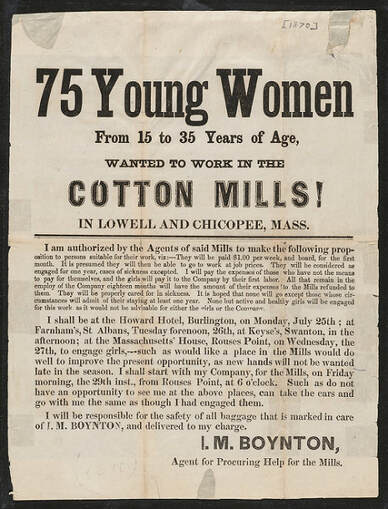

Female Teacher, Public Domain

Female Teacher, Public Domain

Respectable Jobs:

Coming out of the early republic, it was clear that a democracy required women’s labor to raise and educate the electorate. Mothers took on the responsibility of raising smart and moral boys, who would make good decisions for the country. They raise their daughters to be teachers and morally pure.

Therefore, one of the best ways women could earn a wage in the first half of the 19th century was as a teacher and writer, especially on topics of moral importance. Female teachers were held to strict moral standards and expected to maintain a respectable image. They were often subjected to moral scrutiny and faced societal pressures regarding their appearance, conduct, and personal relationships. Any behavior deemed inappropriate or deviating from expected norms could result in criticism or dismissal. Female teachers received significantly lower salaries compared to their male counterparts. They were often paid less for performing the same job, reflecting the prevalent gender-based wage discrimination of the time. This wage disparity persisted despite women's qualifications and experience. Men typically occupied administrative roles and held higher-paying positions, while women were predominantly employed as lower-paid teachers in primary schools (this remains true today).

Teaching was often viewed as a temporary occupation for unmarried women, seen as a way to acquire some income or secure future marriage prospects. Female teachers were required to sign contracts that included "marriage clauses" which stipulated that they must resign if they got married. Such restrictions were intended to ensure that married women would prioritize their domestic duties and conform to societal expectations. Once married, it was expected that female teachers would leave the profession to focus on their roles as wives and mothers. This perception reinforced the notion that teaching was not a long-term career path for women and justified their lower pay. As a result, their authority was sometimes questioned or undermined due to societal beliefs about women's perceived weaknesses and inability to exert control over students, particularly older boys.

Coming out of the early republic, it was clear that a democracy required women’s labor to raise and educate the electorate. Mothers took on the responsibility of raising smart and moral boys, who would make good decisions for the country. They raise their daughters to be teachers and morally pure.

Therefore, one of the best ways women could earn a wage in the first half of the 19th century was as a teacher and writer, especially on topics of moral importance. Female teachers were held to strict moral standards and expected to maintain a respectable image. They were often subjected to moral scrutiny and faced societal pressures regarding their appearance, conduct, and personal relationships. Any behavior deemed inappropriate or deviating from expected norms could result in criticism or dismissal. Female teachers received significantly lower salaries compared to their male counterparts. They were often paid less for performing the same job, reflecting the prevalent gender-based wage discrimination of the time. This wage disparity persisted despite women's qualifications and experience. Men typically occupied administrative roles and held higher-paying positions, while women were predominantly employed as lower-paid teachers in primary schools (this remains true today).

Teaching was often viewed as a temporary occupation for unmarried women, seen as a way to acquire some income or secure future marriage prospects. Female teachers were required to sign contracts that included "marriage clauses" which stipulated that they must resign if they got married. Such restrictions were intended to ensure that married women would prioritize their domestic duties and conform to societal expectations. Once married, it was expected that female teachers would leave the profession to focus on their roles as wives and mothers. This perception reinforced the notion that teaching was not a long-term career path for women and justified their lower pay. As a result, their authority was sometimes questioned or undermined due to societal beliefs about women's perceived weaknesses and inability to exert control over students, particularly older boys.

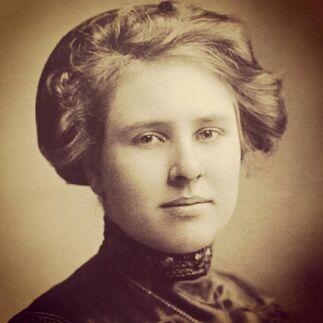

Sarah Josepha Hale, Wikimedia Commons

Sarah Josepha Hale, Wikimedia Commons

Women writers emerged to provide poetry, children’s stories, advice, columns, for other women, and novels. New Hampshire’s Sarah Josepha Hale became the editor of Godey's Lady's Book after her husband died in order to provide for her children. She was famous for authoring "Mary had a Little Lamb," and writing an advice column to women, in which she ironically told them not to have ambition and to keep to the home. Of course, she herself wrote widely, and had a very public life. In fact, many of these women who became published, are noted for their enthusiasm behind a proper woman’s place. Catherine Beecher, who is a palm at abolitionist, who spoke publicly on behalf of Black people. While she supported abolition, she didn’t think women should step outside their spear in order to achieve it.

But then, of course, there was Fanny Wright, also known as the "talking lady" in a time before it was respectable for women to speak in public. She did not care about what was proper. Not only was she a prolific writer, but she traveled around the country giving speeches. Throngs of people came to hear her talk, although mostly to see the spectacle. Wright believed in equality for all people and was an outspoken critic of social injustices. She advocated for women's suffrage, advocating for equal rights and opportunities for women in both the political and social spheres. Wright also strongly opposed slavery and was actively involved in the abolitionist movement before the Civil War. She promoted labor reform, arguing for fair wages, improved working conditions, and shorter workdays. Wright believed in the importance of education and sought to establish educational institutions that provided equal opportunities for both men and women. Wright shaped cultural conversations before the Civil War and pushed the needle for women.

In the middle of the century women also became journalists and reported on everything from society to war. One of the most famous American journalists of the period was Margaret Fuller. Fuller wrote about abolition, and it was a War correspondent. Fuller sought to challenge traditional gender roles and expand opportunities for women. She emphasized the importance of women's education and their active participation in society. In her influential book, "Woman in the Nineteenth Century," published in 1845, Fuller examined the social, political, and cultural constraints placed on women and called for their liberation and equality. Tragically, Margaret Fuller's life was cut short when she, along with her husband and young child, died in a shipwreck in 1850. However, her contributions to literature, feminism, and social reform left a lasting impact. Fuller's writings and ideas continue to be studied and celebrated, highlighting her significance as a pioneering feminist and intellectual of her time.

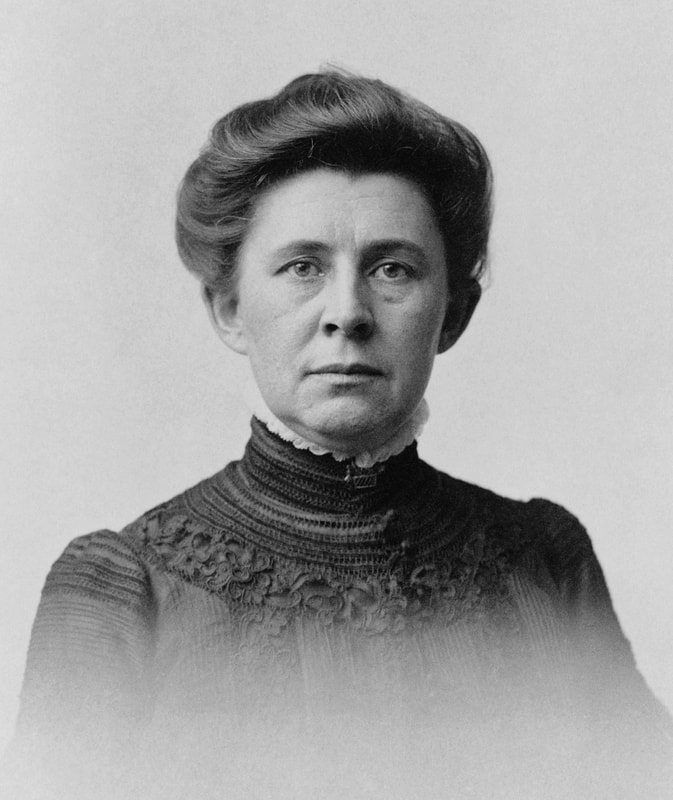

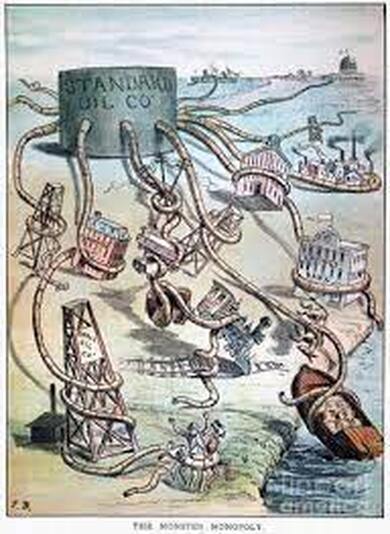

The world of business was rapidly changing and the haves were getting far ahead of the have-nots. It became deeply important to ensure the economy was competitive and that a few industrial leaders didn't dominate everyone by forming monopolies and setting prices. At the end of the century, Ida Tarbell became the first investigative journalist, well known for her exposé of John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company. Published in a number of installments for McClure’s Magazine, this meticulously researched piece revealed the brutal policies that Standard Oil used to force rivals out of business, including her father. Tarbell later compiled those pieces into a two volume book in 1904. As a result of her investigative reporting, the federal government brought a case against Standard Oil for violating the Sherman Antitrust Act which prevented the formation of Monopolies and the Supreme Court ordered the break-up of the oil company into 34 separate companies. Rockefeller hated Tarbell whom he dismissed as an angry lady, but she won and protected the US from being overrun by monopolies. Tarbell continued to write and worked for American Magazine, penning a series of articles against the women’s movement and especially suffrage, in an apparent contradiction of her own public career. These articles were also later made into a book in 1912.

But of course, most of these women were middle class. And the bulk of the industrial revolution was built on the back of lower class women.

But then, of course, there was Fanny Wright, also known as the "talking lady" in a time before it was respectable for women to speak in public. She did not care about what was proper. Not only was she a prolific writer, but she traveled around the country giving speeches. Throngs of people came to hear her talk, although mostly to see the spectacle. Wright believed in equality for all people and was an outspoken critic of social injustices. She advocated for women's suffrage, advocating for equal rights and opportunities for women in both the political and social spheres. Wright also strongly opposed slavery and was actively involved in the abolitionist movement before the Civil War. She promoted labor reform, arguing for fair wages, improved working conditions, and shorter workdays. Wright believed in the importance of education and sought to establish educational institutions that provided equal opportunities for both men and women. Wright shaped cultural conversations before the Civil War and pushed the needle for women.

In the middle of the century women also became journalists and reported on everything from society to war. One of the most famous American journalists of the period was Margaret Fuller. Fuller wrote about abolition, and it was a War correspondent. Fuller sought to challenge traditional gender roles and expand opportunities for women. She emphasized the importance of women's education and their active participation in society. In her influential book, "Woman in the Nineteenth Century," published in 1845, Fuller examined the social, political, and cultural constraints placed on women and called for their liberation and equality. Tragically, Margaret Fuller's life was cut short when she, along with her husband and young child, died in a shipwreck in 1850. However, her contributions to literature, feminism, and social reform left a lasting impact. Fuller's writings and ideas continue to be studied and celebrated, highlighting her significance as a pioneering feminist and intellectual of her time.

The world of business was rapidly changing and the haves were getting far ahead of the have-nots. It became deeply important to ensure the economy was competitive and that a few industrial leaders didn't dominate everyone by forming monopolies and setting prices. At the end of the century, Ida Tarbell became the first investigative journalist, well known for her exposé of John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company. Published in a number of installments for McClure’s Magazine, this meticulously researched piece revealed the brutal policies that Standard Oil used to force rivals out of business, including her father. Tarbell later compiled those pieces into a two volume book in 1904. As a result of her investigative reporting, the federal government brought a case against Standard Oil for violating the Sherman Antitrust Act which prevented the formation of Monopolies and the Supreme Court ordered the break-up of the oil company into 34 separate companies. Rockefeller hated Tarbell whom he dismissed as an angry lady, but she won and protected the US from being overrun by monopolies. Tarbell continued to write and worked for American Magazine, penning a series of articles against the women’s movement and especially suffrage, in an apparent contradiction of her own public career. These articles were also later made into a book in 1912.

But of course, most of these women were middle class. And the bulk of the industrial revolution was built on the back of lower class women.

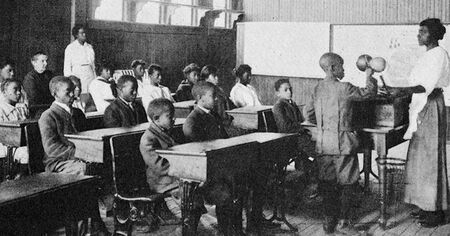

Lowell Mill Ad, Public Domain

Lowell Mill Ad, Public Domain

Lowell Mill Girls:

Most people point to the Lowell Mills as a major turning point both for labor in general, and for women. Millwork popped up along rivers all throughout New England. The mills attracted women from poor farms in the region. As industrialization led to mechanized farm equipment, it essentially freed up the labor of daughters on a farm. Thus, girls left home for a wage and to support their families. In this time, departing from the protection and oversight of their families and doing less respectable work for women could hinder their reputations as "good" women. The promise of a wage was persuasive however and the mills worked to counter the negative narratives about the reputations of their women.

In reality, discussion of their reputation was less important than how overworked these women were. A bell schedule managed their entire lives. Girls wore plain and practical garments that wouldn't catch in the machines. Mill girls worked an average of almost 13 hours per day. Girls despised the confinement in their dormitories, the constant noise from machines, the lint-filled air, and regretted the lost opportunities for education.

The mills promoted themselves to parents and young women with promises that they would have engaging cultural experiences at the boarding houses. The women also began publishing The Lowell Offering from 1840 to 1845. It contained the work produced by some women, including poems and autobiographical sketches, published anonymously or acknowledged only by their initials. The mill owners controlled what appeared in the magazine, so the articles highlighted the girls femininity and tended to be positive. The Lowell Offering stopped being published when women began to strike in 1845.

The danger of mill work was readily known to the girls, they saw it. One girl who worked at the Lowell Mills wrote home, "Last Thursday one girl fell down and broke her neck which caused instant death. She was going in or coming out of the mill and slipped down it being very icy. The same day a man was killed by the [railroad] cars... Last Tuesday we were paid. In all I had six dollars and sixty cents paid $4.68 for board. With the rest I got me a pair of rubbers and a pair of 50.cts shoes…"

In 1834, the Lowell Mill owners decided to reduce the wages of the mill girls and they finally reached their breaking point. They organized to push back against the wage cuts. The mill girls went on strike, marching to various mills to encourage others to join their cause. They congregated at an outdoor rally and signed a petition stating their refusal to return to work unless their wages were maintained. The strikers sang:

"Oh! isn't it a pity, such a pretty girl as I Should be sent to the factory to pine away and die?

Oh ! I cannot be a slave,

I will not be a slave,

For I'm so fond of liberty

That I cannot be a slave."

In their first attempt at strike, the bosses emerged victorious. The management possessed enough power and financial resources to quash the strike. Within a week, the mills were operating almost at full capacity. Things seemed to calm until they cut wages again in 1836. The second strike was better organized and caused more disruption to mill operations. Nonetheless, the bosses maintained control.

Although these were significant setbacks, the mill girls refused to surrender. In the 1840s, they adopted a different strategy—political action. They established the Lowell Female Labor Reform Association to advocate for a shorter workday of ten hours. Despite women's inability to vote in Massachusetts or anywhere else in the country, the mill girls persisted. They conducted extensive petition campaigns, gathering over 2,000 signatures on a petition in 1845, and more than double that number the following year, urging the Massachusetts state legislature to pass a law limiting the workday in mills to ten hours.

Their efforts did not cease. They established chapters in other mill towns in Massachusetts and New Hampshire, published "Factory Tracts" to expose the deplorable conditions in the mills, and provided testimony before a state legislative committee. Furthermore, they actively campaigned against a state representative who staunchly opposed their cause and soundly defeated him. In 1847, New Hampshire became the first state to pass a law mandating a ten-hour workday, but its enforcement was not effective.

Most people point to the Lowell Mills as a major turning point both for labor in general, and for women. Millwork popped up along rivers all throughout New England. The mills attracted women from poor farms in the region. As industrialization led to mechanized farm equipment, it essentially freed up the labor of daughters on a farm. Thus, girls left home for a wage and to support their families. In this time, departing from the protection and oversight of their families and doing less respectable work for women could hinder their reputations as "good" women. The promise of a wage was persuasive however and the mills worked to counter the negative narratives about the reputations of their women.

In reality, discussion of their reputation was less important than how overworked these women were. A bell schedule managed their entire lives. Girls wore plain and practical garments that wouldn't catch in the machines. Mill girls worked an average of almost 13 hours per day. Girls despised the confinement in their dormitories, the constant noise from machines, the lint-filled air, and regretted the lost opportunities for education.

The mills promoted themselves to parents and young women with promises that they would have engaging cultural experiences at the boarding houses. The women also began publishing The Lowell Offering from 1840 to 1845. It contained the work produced by some women, including poems and autobiographical sketches, published anonymously or acknowledged only by their initials. The mill owners controlled what appeared in the magazine, so the articles highlighted the girls femininity and tended to be positive. The Lowell Offering stopped being published when women began to strike in 1845.

The danger of mill work was readily known to the girls, they saw it. One girl who worked at the Lowell Mills wrote home, "Last Thursday one girl fell down and broke her neck which caused instant death. She was going in or coming out of the mill and slipped down it being very icy. The same day a man was killed by the [railroad] cars... Last Tuesday we were paid. In all I had six dollars and sixty cents paid $4.68 for board. With the rest I got me a pair of rubbers and a pair of 50.cts shoes…"

In 1834, the Lowell Mill owners decided to reduce the wages of the mill girls and they finally reached their breaking point. They organized to push back against the wage cuts. The mill girls went on strike, marching to various mills to encourage others to join their cause. They congregated at an outdoor rally and signed a petition stating their refusal to return to work unless their wages were maintained. The strikers sang:

"Oh! isn't it a pity, such a pretty girl as I Should be sent to the factory to pine away and die?

Oh ! I cannot be a slave,

I will not be a slave,

For I'm so fond of liberty

That I cannot be a slave."

In their first attempt at strike, the bosses emerged victorious. The management possessed enough power and financial resources to quash the strike. Within a week, the mills were operating almost at full capacity. Things seemed to calm until they cut wages again in 1836. The second strike was better organized and caused more disruption to mill operations. Nonetheless, the bosses maintained control.

Although these were significant setbacks, the mill girls refused to surrender. In the 1840s, they adopted a different strategy—political action. They established the Lowell Female Labor Reform Association to advocate for a shorter workday of ten hours. Despite women's inability to vote in Massachusetts or anywhere else in the country, the mill girls persisted. They conducted extensive petition campaigns, gathering over 2,000 signatures on a petition in 1845, and more than double that number the following year, urging the Massachusetts state legislature to pass a law limiting the workday in mills to ten hours.

Their efforts did not cease. They established chapters in other mill towns in Massachusetts and New Hampshire, published "Factory Tracts" to expose the deplorable conditions in the mills, and provided testimony before a state legislative committee. Furthermore, they actively campaigned against a state representative who staunchly opposed their cause and soundly defeated him. In 1847, New Hampshire became the first state to pass a law mandating a ten-hour workday, but its enforcement was not effective.

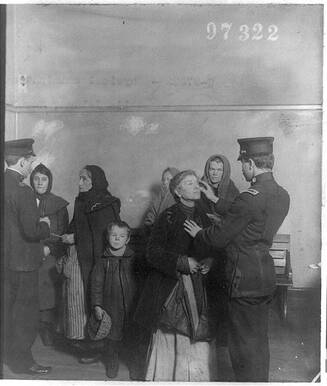

Immigrant Inspections, Library of Congress

Immigrant Inspections, Library of Congress

Migration:

In the late 1800s, the American population grew enormously from both internal migration and external immigration. The internal movement of peoples resulted from demographic shifts as Americans moved from poor rural regions in the south and midwest to find jobs in the industrialized cities in the north. New immigrants made even more competitive the battle over jobs and further put power in the hands of factory owners.

Most immigrants arrived at Ellis Island in New York or Angel Island in California. Upon arrival, female immigrants, like their male counterparts, underwent the rigorous process of immigration inspection and documentation. They were subjected to medical examinations, interviews, and screenings to determine they were healthy and eligible to enter the US. This process aimed to ensure public health and safety, but it could be overwhelming and intimidating for many women, especially if they faced language barriers.

Female immigrants often sought employment in the factories. They worked in sweatshops and domestic service, among other sectors. These jobs provided economic opportunities, but the working conditions were frequently harsh, with long hours, low wages, and unsafe environments. Immigrant women faced exploitation and discrimination, often receiving lower wages than their male counterparts or native-born workers. Female immigrants had to navigate the process of cultural adaptation in a new country. They had to learn a new language, adjust to different social norms, and adapt to unfamiliar customs and practices. This transition could be challenging and isolating, particularly for those who faced discrimination or prejudice based on their ethnicity or nationality. Female immigrants often settled in neighborhoods with other people from their home country. They relied on social support and help in navigating the challenges of life in a new country.

In the late 1800s, the American population grew enormously from both internal migration and external immigration. The internal movement of peoples resulted from demographic shifts as Americans moved from poor rural regions in the south and midwest to find jobs in the industrialized cities in the north. New immigrants made even more competitive the battle over jobs and further put power in the hands of factory owners.

Most immigrants arrived at Ellis Island in New York or Angel Island in California. Upon arrival, female immigrants, like their male counterparts, underwent the rigorous process of immigration inspection and documentation. They were subjected to medical examinations, interviews, and screenings to determine they were healthy and eligible to enter the US. This process aimed to ensure public health and safety, but it could be overwhelming and intimidating for many women, especially if they faced language barriers.

Female immigrants often sought employment in the factories. They worked in sweatshops and domestic service, among other sectors. These jobs provided economic opportunities, but the working conditions were frequently harsh, with long hours, low wages, and unsafe environments. Immigrant women faced exploitation and discrimination, often receiving lower wages than their male counterparts or native-born workers. Female immigrants had to navigate the process of cultural adaptation in a new country. They had to learn a new language, adjust to different social norms, and adapt to unfamiliar customs and practices. This transition could be challenging and isolating, particularly for those who faced discrimination or prejudice based on their ethnicity or nationality. Female immigrants often settled in neighborhoods with other people from their home country. They relied on social support and help in navigating the challenges of life in a new country.

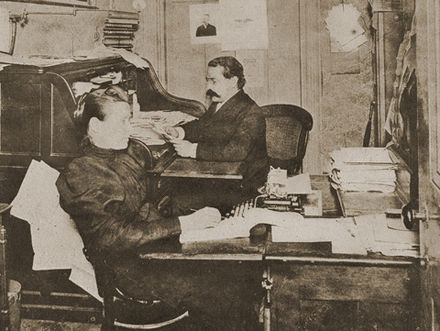

Samuel Gompers, AFL Leadership, Wikimedia Commons

Samuel Gompers, AFL Leadership, Wikimedia Commons

Male Unions:

Sadly male union leaders were not great allies to their sisters in the labor movement. The shift from agrarian economy to factory based systems caused laborers to fight to protect their status and worth in the industrial system. Laborers were categorized by “skilled” and “unskilled” labor. Skilled work required apprenticeships and years of experience. Unskilled jobs could be learned when you got the job and usually required a lot of manual labor. For women, these categories existed, but they were also relegated to “women’s work." This category of work that females could do had not really existed until the industrial revolution and stuck around for a really long time. What genitalia had to do with the ability to do these jobs remains unclear. Male union leaders worked to keep their wages high at the expense of women’s wages. Under served by male leadership, women activists were forced to create their own union, specifically advocated for their interests.

For example, the American Federation of Labor (AFL), founded in 1886, has a dark history of discrimination against women. The AFL had a policy of excluding women from membership in affiliated trade unions. Even within industries where women were allowed to work, the AFL often supported and maintained wage differentials between male and female workers. This practice perpetuated gender-based wage discrimination, with women typically receiving lower wages than their male counterparts for performing the same or similar work.

The AFL did not actively support or prioritize organizing efforts among female workers. Its focus was primarily on organizing male-dominated industries and trades, often neglecting the organizing needs and concerns of women in sectors where they predominated, such as garment manufacturing or domestic service. The AFL's policies and campaigns often prioritized the interests and concerns of male workers, focusing primarily on issues such as higher wages, shorter work hours, and workplace safety. While these were important goals for all workers, the specific challenges and needs of women, such as maternity leave, child labor, and workplace harassment, were often overlooked or given less attention.

The AFL leadership resisted calls for gender equality within the labor movement. Some leaders held traditional views that regarded women as "homemakers" or "helpmates" rather than full participants in the workforce. They wrongly viewed women’s work as "extra," or less essential to the income of the family. This was just not the case in most lower class homes. Women’s labor allowed meals to be put on the table, and every penny counted.

It is worth noting that the AFL's discriminatory practices were not universal among all affiliated unions or individual union members. Some unions within the AFL did admit women as members, and there were instances of successful organizing efforts among women workers, often led by women themselves or in collaboration with sympathetic male unionists. However, these efforts were often met with resistance and opposition from the AFL's leadership and certain union factions.

Sadly male union leaders were not great allies to their sisters in the labor movement. The shift from agrarian economy to factory based systems caused laborers to fight to protect their status and worth in the industrial system. Laborers were categorized by “skilled” and “unskilled” labor. Skilled work required apprenticeships and years of experience. Unskilled jobs could be learned when you got the job and usually required a lot of manual labor. For women, these categories existed, but they were also relegated to “women’s work." This category of work that females could do had not really existed until the industrial revolution and stuck around for a really long time. What genitalia had to do with the ability to do these jobs remains unclear. Male union leaders worked to keep their wages high at the expense of women’s wages. Under served by male leadership, women activists were forced to create their own union, specifically advocated for their interests.

For example, the American Federation of Labor (AFL), founded in 1886, has a dark history of discrimination against women. The AFL had a policy of excluding women from membership in affiliated trade unions. Even within industries where women were allowed to work, the AFL often supported and maintained wage differentials between male and female workers. This practice perpetuated gender-based wage discrimination, with women typically receiving lower wages than their male counterparts for performing the same or similar work.

The AFL did not actively support or prioritize organizing efforts among female workers. Its focus was primarily on organizing male-dominated industries and trades, often neglecting the organizing needs and concerns of women in sectors where they predominated, such as garment manufacturing or domestic service. The AFL's policies and campaigns often prioritized the interests and concerns of male workers, focusing primarily on issues such as higher wages, shorter work hours, and workplace safety. While these were important goals for all workers, the specific challenges and needs of women, such as maternity leave, child labor, and workplace harassment, were often overlooked or given less attention.

The AFL leadership resisted calls for gender equality within the labor movement. Some leaders held traditional views that regarded women as "homemakers" or "helpmates" rather than full participants in the workforce. They wrongly viewed women’s work as "extra," or less essential to the income of the family. This was just not the case in most lower class homes. Women’s labor allowed meals to be put on the table, and every penny counted.

It is worth noting that the AFL's discriminatory practices were not universal among all affiliated unions or individual union members. Some unions within the AFL did admit women as members, and there were instances of successful organizing efforts among women workers, often led by women themselves or in collaboration with sympathetic male unionists. However, these efforts were often met with resistance and opposition from the AFL's leadership and certain union factions.

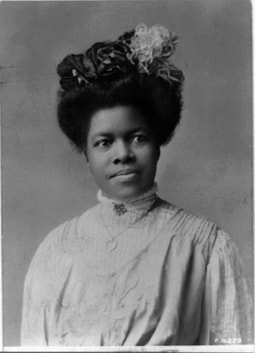

Nannie Helen Burroughs, Library of Congress

Nannie Helen Burroughs, Library of Congress

Nannie Helen Burroughs:

The Lowell mill girls strikes were only the beginning for women's unionization and resistance to industrial greed. In the city of Atlanta, Black washerwomen successfully went on strike in 1881 for better wages, they also created a network among white laundry workers as well to stabilize costs and to notify others about harsh or unfair employers.

In the early 20th century, Nannie Helen Burroughs established the National Trade School for Women and Girls, which was the largest school for Black women and girls in Washington, DC, in 1909. The city of Washington, DC offered a number of better paid domestic jobs, but Burroughs wanted her school to prepare Black women for careers outside of domestic service. The educational program at the National Trade School offered general education, as well as vocational training in domestic service, dressmaking, and business and social service. In 1917, Burroughs co-founded the National Association of Women Wage Earners (NAWE) to organize Black domestic workers into a national union for better wages and conditions. The organization sought recognition from the AFL and soon opened up membership to Black female business owners in the DC area. The organization recognized that other labor groups did not actively recruit and help Black workers, so they did so for themselves. There were 23 chapters in the states of VA, FLA, CT, MA, KY, NY, and PA with a membership of 5-10,000 members. This was a short-lived organization, but demonstrated that it was possible to organize domestic workers when it was widely believed impossible to do so.

The Lowell mill girls strikes were only the beginning for women's unionization and resistance to industrial greed. In the city of Atlanta, Black washerwomen successfully went on strike in 1881 for better wages, they also created a network among white laundry workers as well to stabilize costs and to notify others about harsh or unfair employers.

In the early 20th century, Nannie Helen Burroughs established the National Trade School for Women and Girls, which was the largest school for Black women and girls in Washington, DC, in 1909. The city of Washington, DC offered a number of better paid domestic jobs, but Burroughs wanted her school to prepare Black women for careers outside of domestic service. The educational program at the National Trade School offered general education, as well as vocational training in domestic service, dressmaking, and business and social service. In 1917, Burroughs co-founded the National Association of Women Wage Earners (NAWE) to organize Black domestic workers into a national union for better wages and conditions. The organization sought recognition from the AFL and soon opened up membership to Black female business owners in the DC area. The organization recognized that other labor groups did not actively recruit and help Black workers, so they did so for themselves. There were 23 chapters in the states of VA, FLA, CT, MA, KY, NY, and PA with a membership of 5-10,000 members. This was a short-lived organization, but demonstrated that it was possible to organize domestic workers when it was widely believed impossible to do so.

Knights of Labor Women Delegates, Library of Congress

Knights of Labor Women Delegates, Library of Congress

Mother Jones:

The radical Mary Harris “Mother” Jones proved to be a champion for workers and human rights with her activism from the late 19th to early 20th century. Born into a poor family in Ireland in the 1830s, Harris faced a tragic early life. She witnessed her grandfather’s execution, soldiers destroying her childhood, and brutal treatment of Irish rebels by British soldiers. Tragedy followed her into adulthood in the US, when her husband and four children perished from yellow fever and then she lost her home and livelihood and possessions in the Great Chicago fire. Soon after, she got involved as an organizer for the Knights of Labor and the United Mine Workers. She co-founded the IWW, hoping that all workers would be unified to fight together. She became known as the “most dangerous woman in America,” for her ability to organize and recruit new members to the union cause, and for organizing walkouts and sustaining strikes. Harris captivated audiences for her “motherly” approach from her dress to the speeches she delivered. She urged workers to exercise independence, and to fight for themselves and others. When workers rallied and engaged in strikes, “Mother” Jones was there to boost morale, tend to the sick and injured, to take a turn on the picket line. “Pray for the dead, but fight like hell for the living,” she was noted for saying. Jones was arrested numerous times for her participation in strikes. She traveled thousands of miles for her work and spent her 60s-80s on the road, often at the center of labor actions, from the mining camps in the west and in Pennsylvania and West Virginia, garment workers, and steel workers.

The radical Mary Harris “Mother” Jones proved to be a champion for workers and human rights with her activism from the late 19th to early 20th century. Born into a poor family in Ireland in the 1830s, Harris faced a tragic early life. She witnessed her grandfather’s execution, soldiers destroying her childhood, and brutal treatment of Irish rebels by British soldiers. Tragedy followed her into adulthood in the US, when her husband and four children perished from yellow fever and then she lost her home and livelihood and possessions in the Great Chicago fire. Soon after, she got involved as an organizer for the Knights of Labor and the United Mine Workers. She co-founded the IWW, hoping that all workers would be unified to fight together. She became known as the “most dangerous woman in America,” for her ability to organize and recruit new members to the union cause, and for organizing walkouts and sustaining strikes. Harris captivated audiences for her “motherly” approach from her dress to the speeches she delivered. She urged workers to exercise independence, and to fight for themselves and others. When workers rallied and engaged in strikes, “Mother” Jones was there to boost morale, tend to the sick and injured, to take a turn on the picket line. “Pray for the dead, but fight like hell for the living,” she was noted for saying. Jones was arrested numerous times for her participation in strikes. She traveled thousands of miles for her work and spent her 60s-80s on the road, often at the center of labor actions, from the mining camps in the west and in Pennsylvania and West Virginia, garment workers, and steel workers.

Muller Vs. Oregon, Britannica

Muller Vs. Oregon, Britannica

Muller v. Oregon:

The Muller v. Oregon (1908) case firmly established the legal precedence for protective legislation. In 1903, the state of Orgeon passed a law that made it illegal for employers to keep female factory and laundry workers on the job for more than ten hours a day. Laundry owner Curt Muller, convicted of violating the Oregon law, challenged its constitutionality, and claimed that it violated his right to freedom of contract under the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The Supreme Court heard the case in January 1908. Louis Brandeis, representing the state of Oregon, prepared a lengthy brief, arguing that the state could curb the freedom of contract to protect the health and welfare of its citizens. The Brandeis Brief used “facts” to demonstrate that women had “special physical organization” (anatomical and physiological differences) and were “fundamentally weaker” than men (according to physicians at that time). According to Brandeis, long hours were not only dangerous to the physical health of women, who could suffer from “pelvic disorders” that would jeopardize their ability to give birth; but they might also succumb to lax moral behavior as well. The argument ends with the reasonableness of the ten-hour day for working women as good for the welfare of the country. Six weeks later, the Supreme Court upheld the Oregon law, making women wards of the state. Many states already had some protective laws on the books, and more would do so after the Muller decision. By 1914, twenty-seven states regulated some aspect of women’s work, from how many hours, to night work, limits on carrying weights, and working in dangerous or morally hazardous places (bars/saloons, meter readers for the gas and electric companies, streetcar conductors, and elevator operators for instance). By 1920, fifteen states passed minimum wage laws to protect the moral health of working women. Most male union officials supported protective legislation for women because it limited women's competitiveness in the labor market.

One of the unintended consequences of the protective laws played a role in the garment strikes in Lawrence, MA in 1912. Massachusetts legislators, in response to reformers and the AFL, successfully lobbied for the maximum work week to be reduced from 56 to 54 hours for women and children. When the law went into effect on January 1, 1912, thousands of workers at the American Woolen Company, many of whom were women, walked off the job in protest of losing money from their paychecks on January 11.

The Muller v. Oregon (1908) case firmly established the legal precedence for protective legislation. In 1903, the state of Orgeon passed a law that made it illegal for employers to keep female factory and laundry workers on the job for more than ten hours a day. Laundry owner Curt Muller, convicted of violating the Oregon law, challenged its constitutionality, and claimed that it violated his right to freedom of contract under the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The Supreme Court heard the case in January 1908. Louis Brandeis, representing the state of Oregon, prepared a lengthy brief, arguing that the state could curb the freedom of contract to protect the health and welfare of its citizens. The Brandeis Brief used “facts” to demonstrate that women had “special physical organization” (anatomical and physiological differences) and were “fundamentally weaker” than men (according to physicians at that time). According to Brandeis, long hours were not only dangerous to the physical health of women, who could suffer from “pelvic disorders” that would jeopardize their ability to give birth; but they might also succumb to lax moral behavior as well. The argument ends with the reasonableness of the ten-hour day for working women as good for the welfare of the country. Six weeks later, the Supreme Court upheld the Oregon law, making women wards of the state. Many states already had some protective laws on the books, and more would do so after the Muller decision. By 1914, twenty-seven states regulated some aspect of women’s work, from how many hours, to night work, limits on carrying weights, and working in dangerous or morally hazardous places (bars/saloons, meter readers for the gas and electric companies, streetcar conductors, and elevator operators for instance). By 1920, fifteen states passed minimum wage laws to protect the moral health of working women. Most male union officials supported protective legislation for women because it limited women's competitiveness in the labor market.

One of the unintended consequences of the protective laws played a role in the garment strikes in Lawrence, MA in 1912. Massachusetts legislators, in response to reformers and the AFL, successfully lobbied for the maximum work week to be reduced from 56 to 54 hours for women and children. When the law went into effect on January 1, 1912, thousands of workers at the American Woolen Company, many of whom were women, walked off the job in protest of losing money from their paychecks on January 11.

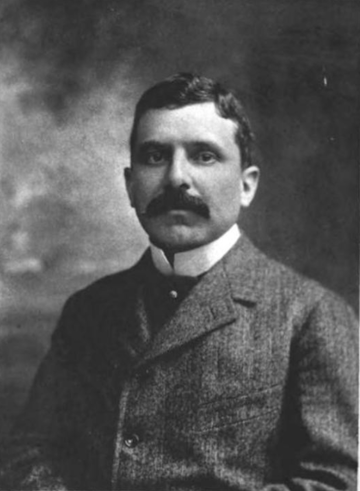

William Wood, Wikimedia Commons

William Wood, Wikimedia Commons

Wage-earners at American Woolen could not afford to lose any of their pay, since they lived in dire circumstances in the company town controlled by the company’s president, William Wood. Workers lived in crowded dingy company tenements and their workplace conditions proved not to be any better. Workers had to pay for drinking water, and were docked pay for being a minute late to work. Infant mortality rates were high in the company tenements and the accident rate on the job was high as well. The work pace increased and in spite of a $3 million profit margin in 1911, Wood refused to raise worker’s wages for two fewer hours of work. While the difference in the pay amount seemed small, thirty to forty cents, for the workers that was the equivalent to four loaves of bread, which was significant to these workers who lived paycheck to paycheck.

Like the earlier shirtwaist strikes, the strike in Lawrence received a lot of attention due to the cooperation of the Polish, Italian, German, Lithuanian, and Syrian workers, and the presence and support from the IWW. Many IWW activists were present in the town during the strike. "It was the spirit of the workers that was dangerous," wrote labor reporter Mary Heaton Vorse. "They are always marching and singing. The crowds flowing perpetually into the mills had waked and opened their months to sing."

Publicity came when the striking workers sent their children to sympathetic families in New York City and Vermont, when the strike conditions worsened. American Woolen used their own security force and relied on the local police to battle with the workers.

Like the earlier shirtwaist strikes, the strike in Lawrence received a lot of attention due to the cooperation of the Polish, Italian, German, Lithuanian, and Syrian workers, and the presence and support from the IWW. Many IWW activists were present in the town during the strike. "It was the spirit of the workers that was dangerous," wrote labor reporter Mary Heaton Vorse. "They are always marching and singing. The crowds flowing perpetually into the mills had waked and opened their months to sing."

Publicity came when the striking workers sent their children to sympathetic families in New York City and Vermont, when the strike conditions worsened. American Woolen used their own security force and relied on the local police to battle with the workers.

Pearl McGill

Pearl McGill

The first group of children to leave on the “children’s exodus” paraded in the streets of NYC with pro-strike banners. When the next group of children and mothers arrived at the train station on Feb. 24th, many of them were beaten and taken into custody. They tore children from their parents, threw women and children into a patrol wagon, and detained 30. One woman testified: "The children, two by two in an orderly procession with the parents near, were about to make their way to the train when the police...closed in on us with their clubs, beating with no thought of the children who were in desperate danger of being trampled to death. The mothers and the children were thus hurled in a mass and bodily dragged to a military truck and even then clubbed, irrespective of the cries of the mothers and children."

Pearl McGill, went to Lawrence after the strike began, through her position as a speaker for the WTUL. McGill, who first gained recognition for her activism in the button workers strike in Muscatine, Iowa in 1911. Congress ended up investigating the strike because of the publicity received in early March 1912. Faced with negative publicity, the American Woolen Company negotiated a settlement with the strikers. Employees received a pay increase between 5 to 25 percent depending on the job, the bonus system put in place for fast work pace changed to minimize the impact of sickness or absence. Those who participated in the strike faced no reprisals from the company as well. The strike lasted nine weeks.

Pearl McGill, went to Lawrence after the strike began, through her position as a speaker for the WTUL. McGill, who first gained recognition for her activism in the button workers strike in Muscatine, Iowa in 1911. Congress ended up investigating the strike because of the publicity received in early March 1912. Faced with negative publicity, the American Woolen Company negotiated a settlement with the strikers. Employees received a pay increase between 5 to 25 percent depending on the job, the bonus system put in place for fast work pace changed to minimize the impact of sickness or absence. Those who participated in the strike faced no reprisals from the company as well. The strike lasted nine weeks.

Women's Trade Union League with Eleanor Roosevelt, Wikimedia Commons

Women's Trade Union League with Eleanor Roosevelt, Wikimedia Commons

Garment Workers Strikes:

Between 1909 and 1919, hundreds of thousands of young women in the garment industry from large and smaller cities in New York, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Illinois organized, struck, raised their wages, and in many shops won the right to unionize. Better machines and innovations in the garment trades meant work sped up at the same time that foremen engaged in humiliating practices on the job. Manufacturers did not keep large inventories, so they rushed workers to complete orders when they arrived, which meant there were slack periods when more than a third of the workers were laid-off. The subcontracting or “sweating” system also played a role in creating poor working conditions and low wages. Large manufacturers hired contractors, who provided sewing machines and a physical location for work, often in crowded warehouses with inadequate or safe partitions. The garment workers’ anger built up and led them to band together to fight against these practices. These workers also needed enforceable labor laws to protect them. At the time, the men who ran most of the existing labor unions did not believe it was possible to organize these un- and semiskilled workers. The young women proved that wrong.

The “Uprising of the 20,000” (or more) was one in a series of crucial struggles of working class women to gain better work conditions and pay increases. New industrial unions emerged to support them, such as the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU) and the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America (ACWA). The International Workers of the World (IWW also known as the Wobblies), also competed with the AFL for the allegiance of industrial workers. Working class militancy, of which women played a huge role, spread from the textile industry to other sectors of the US economy. Garment activists such as Rose Schneiderman, Clara Lemlich, Pauline Newman, and Pearl McGill all played a role in organizing, striking, and speaking in support of striking workers. These young women embraced what has been called “industrial feminism,” where workplace issues created anger and a bond between the garment workers that aided in organizing and working together to resist their employers.

The working women found support from the Women’s Trade Union League. Founded in 1903 by a coalition of female trade unionists, settlement house residents, and social reformers. The WTUL wanted to improve the situation of women workers through organizing them into trade unions, lobbying for legislation to control hours and work conditions, and educating the workers of the special problems of women workers. Rose Schneiderman developed a close relationship with the wealthier women who led the WTUL. This organization began investigating conditions in the garment factories and realized that there were safety issues and concerns about factory practices. The League had a number of chapters in industrial cities and tried to steer the young women from the radical influence, such as from the Socialist Party or the IWW.

Between 1909 and 1919, hundreds of thousands of young women in the garment industry from large and smaller cities in New York, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Illinois organized, struck, raised their wages, and in many shops won the right to unionize. Better machines and innovations in the garment trades meant work sped up at the same time that foremen engaged in humiliating practices on the job. Manufacturers did not keep large inventories, so they rushed workers to complete orders when they arrived, which meant there were slack periods when more than a third of the workers were laid-off. The subcontracting or “sweating” system also played a role in creating poor working conditions and low wages. Large manufacturers hired contractors, who provided sewing machines and a physical location for work, often in crowded warehouses with inadequate or safe partitions. The garment workers’ anger built up and led them to band together to fight against these practices. These workers also needed enforceable labor laws to protect them. At the time, the men who ran most of the existing labor unions did not believe it was possible to organize these un- and semiskilled workers. The young women proved that wrong.

The “Uprising of the 20,000” (or more) was one in a series of crucial struggles of working class women to gain better work conditions and pay increases. New industrial unions emerged to support them, such as the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU) and the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America (ACWA). The International Workers of the World (IWW also known as the Wobblies), also competed with the AFL for the allegiance of industrial workers. Working class militancy, of which women played a huge role, spread from the textile industry to other sectors of the US economy. Garment activists such as Rose Schneiderman, Clara Lemlich, Pauline Newman, and Pearl McGill all played a role in organizing, striking, and speaking in support of striking workers. These young women embraced what has been called “industrial feminism,” where workplace issues created anger and a bond between the garment workers that aided in organizing and working together to resist their employers.

The working women found support from the Women’s Trade Union League. Founded in 1903 by a coalition of female trade unionists, settlement house residents, and social reformers. The WTUL wanted to improve the situation of women workers through organizing them into trade unions, lobbying for legislation to control hours and work conditions, and educating the workers of the special problems of women workers. Rose Schneiderman developed a close relationship with the wealthier women who led the WTUL. This organization began investigating conditions in the garment factories and realized that there were safety issues and concerns about factory practices. The League had a number of chapters in industrial cities and tried to steer the young women from the radical influence, such as from the Socialist Party or the IWW.

Clara Lemlich, National Park Services

Clara Lemlich, National Park Services

Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire:

Clara Lemlich, a Ukrainian immigrant, had been working to organize the shirtwaist workers for several years before she called for a general strike in New York City Nov. 22, 1909. In her extemporaneous speech she said, “The working woman needs bread, but she needs roses, too.” The following day, thousands of garment workers took to the streets in protest.

Employers tried to divide the workforce along ethnic lines, but it largely failed due to a collective identity and increased militancy among the young women. These young women led the strike, were responsible for the size of the strike, and the spirit of the strike. They faced beatings from company guards, the local police, and the company trying to besmirch their image by hiring prostitutes to walk on the picket line. The ILGWU and the WTUL helped support the workers, raising funds for bail when the strikers were arrested and serving on the picket lines. One journalist commented that he could not tell the difference between the workers and the women of the WTUL. The Socialist Party also helped, walking the picket lines and providing mentors, publicity, and funds to help the striking workers.

Clara Lemlich, a Ukrainian immigrant, had been working to organize the shirtwaist workers for several years before she called for a general strike in New York City Nov. 22, 1909. In her extemporaneous speech she said, “The working woman needs bread, but she needs roses, too.” The following day, thousands of garment workers took to the streets in protest.

Employers tried to divide the workforce along ethnic lines, but it largely failed due to a collective identity and increased militancy among the young women. These young women led the strike, were responsible for the size of the strike, and the spirit of the strike. They faced beatings from company guards, the local police, and the company trying to besmirch their image by hiring prostitutes to walk on the picket line. The ILGWU and the WTUL helped support the workers, raising funds for bail when the strikers were arrested and serving on the picket lines. One journalist commented that he could not tell the difference between the workers and the women of the WTUL. The Socialist Party also helped, walking the picket lines and providing mentors, publicity, and funds to help the striking workers.

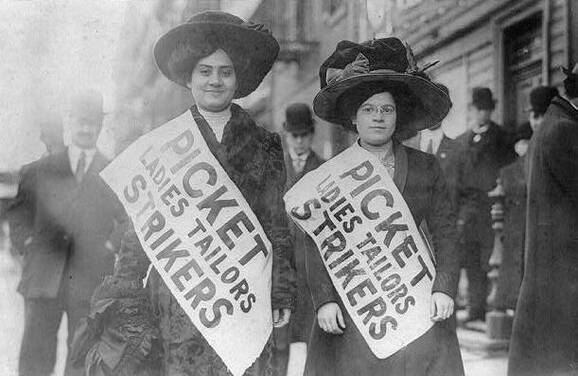

Tailors on Strike, Wikimedia Commons

Tailors on Strike, Wikimedia Commons

The shirtwaist strike was not just in NYC. When Philadelphia garment workers found out that New York manufacturers sent their work for the Philadelphia shirtwaist factories to complete, the young immigrant women walked off the job in their own strike against this action, and their own grievances against the garment factory owners. The Philadelphia strike doesn’t get the same attention now as the New York uprising, but in 1909 and 1910 it did. The ILGWU and the WTUL also played a big part in helping the striking PA garment workers. Rose Schneiderman spoke in Philadelphia in her role at the WTUL, and Margaret Dreier Robins, the president of the WTUL arrived to help four days after the strike in Philadelphia began. The WTUL set up a headquarters near the largest factory and raised money and awareness to provide daily lunches for the strikers and general funds to help the workers. The radical labor agitator, Mary Harris “Mother” Jones also came to Philadelphia to boost morale among the strikers as well. She implored the young women to rely on themselves and not wealthy women, like Alva Belmont, widow of Oliver Hazard Perry Belmont, or Anne Morgan, daughter of J.P. Morgan. Both women used their considerable fortunes to aid the working women through the WTUL, but both women thought that many of the strike actions were too radical and didn't like their connections to socialism.

The NYC shirtwaist strike lasted about eleven weeks and a majority of the shirtwaist factories settled with the workers, particularly in the small shops. The women gained better pay, union recognition, a 52 hour work week, and provision of tools and materials without fees. The ILGWU ranks swelled as about 85% of the shirtwaist workers joined the union. The Philadelphia strikers made similar demands and the smaller shops settled with the garment workers sooner than the large manufacturers as well. The Philadelphia strike lasted about seven weeks.

These strikes did not resolve all of the issues faced by the garment workers. Then, as a result of the failure to effectively bargain with the bosses, on March 25, 1911 a fire broke out at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory and 146 workers lost their lives, most of whom were young Italian and Jewish immigrant women. Within a short span of time, the fire engulfed the entire eighth floor of the ten-story building, but the women were trapped because the doors to the stairs were locked by the bosses to prevent them from taking frequent bathroom breaks, and the elevator couldn't hold everyone so they had to wait while it went up and down. The bosses on the upper floors escaped to another building without alerting people on other floors. Women fled to the fire escape outside, but it collapsed under the weight of so many women trying to evacuate. Two dozen women died from the fall. Bystanders, attracted by the rising smoke and the commotion of fire trucks rushing to the scene, watched with helpless horror as numerous workers cried out for help from the windows on the ninth floor. Desperate firefighters operated a rescue ladder, which ascended slowly towards the sky, but it was too short! It only made it to the sixth floor. With the fire rapidly advancing, the workers, driven by fear, started jumping and falling to their deaths on the sidewalk below. Some workers perished in the inferno, while others tragically fell down the open elevator shaft.

The NYC shirtwaist strike lasted about eleven weeks and a majority of the shirtwaist factories settled with the workers, particularly in the small shops. The women gained better pay, union recognition, a 52 hour work week, and provision of tools and materials without fees. The ILGWU ranks swelled as about 85% of the shirtwaist workers joined the union. The Philadelphia strikers made similar demands and the smaller shops settled with the garment workers sooner than the large manufacturers as well. The Philadelphia strike lasted about seven weeks.

These strikes did not resolve all of the issues faced by the garment workers. Then, as a result of the failure to effectively bargain with the bosses, on March 25, 1911 a fire broke out at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory and 146 workers lost their lives, most of whom were young Italian and Jewish immigrant women. Within a short span of time, the fire engulfed the entire eighth floor of the ten-story building, but the women were trapped because the doors to the stairs were locked by the bosses to prevent them from taking frequent bathroom breaks, and the elevator couldn't hold everyone so they had to wait while it went up and down. The bosses on the upper floors escaped to another building without alerting people on other floors. Women fled to the fire escape outside, but it collapsed under the weight of so many women trying to evacuate. Two dozen women died from the fall. Bystanders, attracted by the rising smoke and the commotion of fire trucks rushing to the scene, watched with helpless horror as numerous workers cried out for help from the windows on the ninth floor. Desperate firefighters operated a rescue ladder, which ascended slowly towards the sky, but it was too short! It only made it to the sixth floor. With the fire rapidly advancing, the workers, driven by fear, started jumping and falling to their deaths on the sidewalk below. Some workers perished in the inferno, while others tragically fell down the open elevator shaft.

Frances Perkins, Wikimedia Commons

Frances Perkins, Wikimedia Commons

This devastating incident remained New York's deadliest workplace disaster for a period of 90 years. In the long term, the fire resulted in massive public demonstrations and calls for factory inspections and improved safety standards for the workers. One of the results of the strikes and factory fires included state protective legislation. The Women’s Trade Union League and the National Consumers’ League both sought legislative redress for workplace issues, when it appeared that they could not halt the exclusions of women from organized labor leadership, even with the successes of the garment strikes of 1909-1910. The wealthier women involved in these organizations did not adequately understand the appeal that radicalism had among the working women. The working women often resented the savior role that the wealthier women projected in their efforts, as “allies” knew better than the workers what they needed. The WTUL and Consumers’ League sought societal support for establishing maximum hours, minimum wages, limits on night work or work in morally dangerous places, as well as weight and height restrictions.

Also, Frances Perkins was present at the scene of the tragic fire and personally witnessed the horrific events and the devastating loss of life. This experience deeply affected her and played a pivotal role in shaping her future advocacy for workers' rights and safety. In the aftermath of the fire, Perkins became increasingly involved in labor and reform movements. She dedicated her career to advocating for workers' rights, improved workplace conditions, and labor legislation. Her commitment eventually led her to serve as the U.S. Secretary of Labor under President Franklin D. Roosevelt, making her the first woman to hold a cabinet position in the United States.

Conclusion:

Working women faced challenges from every direction. Laws that might improve their workplace situation limited their competitive edge in the market with men. Women from other classes weren't always allies and this limited their financial and political bargaining.

By the end of this era so much remained in question. Could women find equity in the labor market? What could be done to improve working conditions? Would the vote improve women's ability to advocate for better wages? Would wealthy women join them in the battle? Would women's labor continue to be devalued?

Also, Frances Perkins was present at the scene of the tragic fire and personally witnessed the horrific events and the devastating loss of life. This experience deeply affected her and played a pivotal role in shaping her future advocacy for workers' rights and safety. In the aftermath of the fire, Perkins became increasingly involved in labor and reform movements. She dedicated her career to advocating for workers' rights, improved workplace conditions, and labor legislation. Her commitment eventually led her to serve as the U.S. Secretary of Labor under President Franklin D. Roosevelt, making her the first woman to hold a cabinet position in the United States.

Conclusion:

Working women faced challenges from every direction. Laws that might improve their workplace situation limited their competitive edge in the market with men. Women from other classes weren't always allies and this limited their financial and political bargaining.

By the end of this era so much remained in question. Could women find equity in the labor market? What could be done to improve working conditions? Would the vote improve women's ability to advocate for better wages? Would wealthy women join them in the battle? Would women's labor continue to be devalued?

Draw your own conclusions

|

Learn how to teach with inquiry.

Many of these lesson plans were sponsored in part by the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources Eastern Region Program, coordinated by Waynesburg University, the History and Social Studies Education Faculty at Plymouth State University, and the Patrons of the Remedial Herstory Project. |

Lesson Plans from Other Organizations

- The National Women's History Museum has lesson plans on women's history.

- The Guilder Lehrman Institute for American History has lesson plans on women's history.

- The NY Historical Society has articles and classroom activities for teaching women's history.

- Unladylike 2020, in partnership with PBS, has primary sources to explore with students and outstanding videos on women from the Progressive era.

- The Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media has produced recommendations for teaching women's history with primary sources and provided a collection of sources for world history. Check them out!

- The Stanford History Education Group has a number of lesson plans about women in US History.

Period Specific Lesson Plans from Other Organizations

- National Women’s History Museum: On the Eve of the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire, what were the conditions in the sweatshops of Manhattan in 1911 and how were individuals seeking change? The story of the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire is multidimensional. The tragedy, which caused the death of 146 garment workers, highlighted many of the issues that defined urban life in turn-of-the-century America. These topics include, but are not limited to labor unions, immigration, industrialization, and factory girls working in sweatshop conditions in Manhattan’s garment district. March 25, 1911 became a benchmark moment in the Progressive Era that ultimately resulted in drastic changes in labor standards for factories across New York City, and later the nation. However, with the horrifying death toll, mostly young immigrant women, it is a story that highlights early 20th century labor activism, the power of big business, and the emerging voice of women, still silenced at the voting booths. Through this tragic event, we can learn about not only the women who died but the movement that they provoked and the conditions of labor that they forever changed.

- Gilder Lehrman: How did the Industrial Revolution impact the lives of women and what were the causes and effects of the fire? Dramatic change characterized the rapid industrialization of nineteenth-century America. The economy, politics, society and specifically women were all affected. In the early stages of this economic revolution, manufacturing was moved to factories in newly developing urban areas. Young women began working in the textile industry as early as 1820. Later on as goods were increasingly produced by machines run by unskilled labor, the number of women in the industrial workforce grew. Women entered the ranks of industrial workforce as seamstresses who produced ready-made clothing in the city sweatshops. One event, the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, helps us to understand the experience of these women.

- Unladylike: Learn about the pioneering industrial engineer and psychologist, Lillian Moller Gilbreth, in this digital short from Unladylike2020. Using video, vocabulary and discussion questions, students learn about how her innovations improved American’s lives in both factories and the home.

- Unladylike: Learn about Susan La Flesche Picotte, the first American Indian physician and the first to found a private hospital on an American Indian reservation, in this video from the Unladylike2020 series. Susan La Flesche Picotte grew up on the Omaha Reservation in Nebraska against the backdrop of the Dawes Act of 1887 which sought to force indigenous tribes onto reservations and foster their assimilation into white society. Neither of her parents spoke English, but they encouraged her pursuit of an Anglo-American education. Picotte graduated from Women’s Medical College in 1889 and returned to the Omaha reservation to spend her career making house calls on foot, horse, and horse-drawn buggy across its 1,350 square miles. Also a fierce community leader, Picotte worked tirelessly to help her tribe combat the theft of American Indian land and public health crises including the spread of tuberculosis and alcoholism. Support materials include discussion questions, research project ideas, and primary source analysis.

- Unladylike: Learn about Annie Smith Peck, one of the first women in America to become a college professor and who took up mountain climbing in her forties, in this video from Unladylike2020. Peck gained international fame in 1895 when she first climbed the Matterhorn in the Swiss Alps -- not for her daring ascent, but because she undertook the climb wearing pants rather than a cumbersome skirt. Fifteen years later, at age 58, Peck was the first mountaineer ever to conquer Mount Huascarán in Peru, one of the highest peaks in the Western Hemisphere. Support materials include discussion questions, vocabulary, and teaching tips for extending learning through research projects.

- Voices of Democracy: There is a chasm in history classes between the Civil War and World War I in which it is difficult to engage students. If the Progressive Era is taught strictly through the historical facts—of unions, poor working conditions, Theodore Roosevelt’s reforms, and so on—students may have a difficult time envisioning the era’s importance to American history. This speech by Mary Harris ‘Mother’ Jones helps draw students into the Progressive Era in two ways. First, Jones’s vivid and cantankerous personality certainly draws students’ attention. She represents an important female voice during an era before women had the right to vote. Secondly, Jones’s speech provides an illustrative entry point to help students understand the working conditions that triggered the Progressive Movement, the intensity of the disputes between workers and their employers, and the formation of labor unions in the United States.

- National Womens History Museum: This lesson sees to explore the multifaceted and nuanced ways in which Helen Keller is remembered. By starting with an entry level text, students will be exposed to the way in which Keller is taught to elementary and middle school students. From there, students will seek to rewrite the story on Helen Keller using primary sources via a jigsaw activity to generate meaning. Students will consider the role of historical memory and consider the ways in which some of the ideas and beliefs of historical actors are ignored by history.

- Stanford History Education Group: Some historians have characterized Progressive reformers as generous and helpful. Others describe the reformers as condescending elitists who tried to force immigrants to accept Christianity and American identities. In this structured academic controversy, students read documents written by reformers and by an immigrant to investigate American attitudes during the Progressive Era.

- National History Day: Dorothea Lynde Dix (1802-1887) was born in Hampden, Maine, to a poor family. At age 12 she went to live with her grandmother in Boston. When she was only 14, Dix founded a school in Worcester, Massachusetts. After a 20-year career as a teacher and writer, in 1841 Dix visited a jail in East Cambridge, Massachusetts, and was appalled by the conditions. Many of the prisoners were mentally ill, and they were treated terribly by being ill-fed and abused. Dix took it upon herself to report these condition to the Massachusetts Legislature in 1843, documenting the poor conditions faced by hundreds of mentally ill men and women. Her action led to the successful passage of a bill to reform the way the state treated prisoners and people with mental illness. Dix canvassed the country working for prison reform and improved conditions for the mentally ill. Eventually her crusade became international. She even lobbied the pope in person about conditions in Italy. During the Civil War Dix served without pay as superintendent of nurses for the Union Army in the U.S. Sanitary Commission. She died on July 17, 1887, in a Trenton, New Jersey, hospital that she had founded.

- National History Day: Ida B. Wells (1862-1931) was born to slave parents in Holly Springs, Mississippi, on July 16, 1862, two months before President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. As a young girl, Wells watched her parents work as political activists during Reconstruction. In 1878, tragedy struck as Wells lost both of her parents and a younger brother in a yellow fever epidemic. To support her younger siblings, Wells became a teacher, eventually moving to Memphis, Tennessee. In 1884, Wells found herself in the middle of a heated lawsuit. After purchasing a first-class train ticket, Wells was ordered to move to a segregated car. She refused to give up her seat and was forcibly removed from the train. Wells filed suit against the railroad and won. This victory was short lived, however, as the Tennessee Supreme Court overturned the lower court ruling in 1887. In 1892, Wells became editor and co-owner of The Memphis Free Speech and Headlight. Here, she used her skills as a journalist to champion the causes for African American and women’s rights. Among her most known works were those on behalf of anti-lynching legislation. Until her death in 1931, Ida B. Wells dedicated her life to what she referred to as a “crusade for justice.”

- Unladylike: Examine the life and legacy of the health, labor, and immigrant rights reformer Grace Abbott in this resource from Unladylike2020. Born into a progressive family of abolitionists and suffragettes in Nebraska, Abbott made it her life’s work to help those in need—focusing on fighting for the rights of children, recent immigrants, and new mothers and their babies. Support materials include a digital short, vocabulary and discussion questions.

- PBS and DPLA: This collection uses primary sources to explore settlement houses during the Progressive Era. Digital Public Library of America Primary Source Sets are designed to help students develop their critical thinking skills and draw diverse material from libraries, archives, and museums across the United States. Each set includes an overview, ten to fifteen primary sources, links to related resources, and a teaching guide. These sets were created and reviewed by the teachers on the DPLA's Education Advisory Committee.

- Unladylike: Learn about Martha “Mattie” Hughes Cannon, an accomplished physician, suffragist, and the first woman state senator in the United States, elected in 1896 in the state of Utah. This digital short from Unladylike2020 features the story of an immigrant child from Wales, UK, who moved with her family at age 2 to Utah, became a physician, opened her own medical practice, married into a plural marriage, fled the country in exile, returned and then ran for state office—and won—when most women in the United States did not have the right to vote. In this resource, students explore the life and times of Hughes Cannon using video, discussion questions, and analysis of primary sources and informational texts to learn more about the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and how women’s roles evolved throughout its history.