10. 100-500 Women Travelers and Merchants on the Silk Roads

|

The Silk Roads connected people, spread ideas, religions, and commerce, and created empires for those able to control the roads. Women were integral to every aspect of the Roads. Women served as primary producers of crucial items sold and transported along the roads, not withstanding their name sake: Silk. Women literally made it! Women were also sold as brides along the roads to help establish peace between governments.

|

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

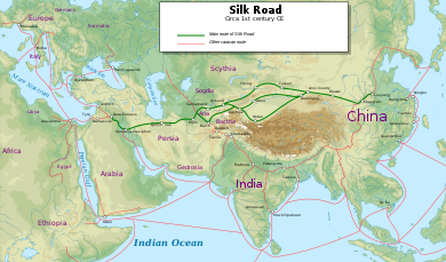

Between the first century BCE and the third century CE, a vast network of trade routes emerged from smaller regional trading zones and ultimately connected markets from China to the Mediterranean. The world became more culturally diverse than we have been taught to expect in ancient history. The trade network is known as the Silk Road, but it was never just one road, and silk was far from the only trade item. Ideas, belief systems, arts, and disease accompanied the caravans as they crossed the continent. Many of the merchants and migrants on these trade routes were men, but women played lead roles every step of the way.

Han Dynasty China serves as the foundational state in the growth in trade during this era, although there were many other players, notably because the silk, which gave the roads their name, came from China. As far back as 3000 BCE the Chinese established a monopoly over silk production. Women were important in the trade as producers and consumers of this precious commodity. The emergence of large, stable empires made long distance trade across Afro-Eurasia possible.

Large states offered a number of advantages that made trade possible. There were fortified cities and armies to offer protection. There were several established roads as well as infrastructure such as bridges and canals. Market towns dotted the route, and in the desert these towns emerged at oases where water was available. Trae route towns boasted more than marketplaces—the weary traveler could find inns, stables, temples, and entertainment in towns such as Turfan and Dunhuang. People tended to travel in great caravans including dozens or even hundreds of people—sometimes entire families migrated in this way. At the height of Silk Road traffic, it was possible to join a new caravan if you found one heading to a different city. One Sogdian woman awaiting family in Dunhuang in the 4th century wrote to a friend that at least five caravans had departed in one day.

Han Dynasty China serves as the foundational state in the growth in trade during this era, although there were many other players, notably because the silk, which gave the roads their name, came from China. As far back as 3000 BCE the Chinese established a monopoly over silk production. Women were important in the trade as producers and consumers of this precious commodity. The emergence of large, stable empires made long distance trade across Afro-Eurasia possible.

Large states offered a number of advantages that made trade possible. There were fortified cities and armies to offer protection. There were several established roads as well as infrastructure such as bridges and canals. Market towns dotted the route, and in the desert these towns emerged at oases where water was available. Trae route towns boasted more than marketplaces—the weary traveler could find inns, stables, temples, and entertainment in towns such as Turfan and Dunhuang. People tended to travel in great caravans including dozens or even hundreds of people—sometimes entire families migrated in this way. At the height of Silk Road traffic, it was possible to join a new caravan if you found one heading to a different city. One Sogdian woman awaiting family in Dunhuang in the 4th century wrote to a friend that at least five caravans had departed in one day.

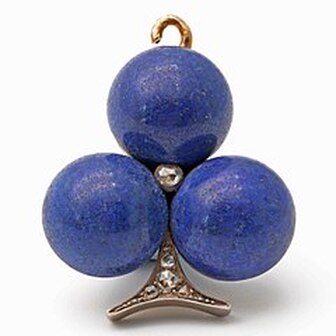

Persian Gold and Lapis Lazuli, Wikimedia Commons

Persian Gold and Lapis Lazuli, Wikimedia Commons

The Han emperors of China wanted to trade with the distant Parthian Empire of Persia (247 BCE-244 CE), especially because of their desire for horses that could help Chinese armies defend outlying towns from Xiongnu raids. Merchants traveling to the west had to pass through uncontrolled areas in the steppe and also had to deal with the Kushan Empire (30-334 CE) to the north of India. The Kushan were descended from another nomadic group called the Yuezhi. Beyond Persia, trade routes extended into the Roman Empire and the Mediterranean Sea. Silky Sea routes linked Indian Ocean trade (400 BCE-350 CE) to the Mediterranean via the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf. There were times when silk and jade from China passed through the markets of five different empires and countless independent towns. Roman glass and olive oil made the return journey, traded from merchant to merchant, town to town–Containers of Chinese goods fill our harbors, and we send them debt? Persian gold and lapis lazuli adorned wealthy homes in every direction. Ivory and gold carried northward along the eastern coast of Africa were popular items everywhere. Indian cottons, coral, pearls, and spices rounded out the offerings.

China gradually built its military defenses, but force alone was never enough to ensure peace in central Asia. Diplomacy was also essential, and the easiest way to seal a treaty with a Xiongnu or Mongolian chieftain was to offer a Chinese princess as a bride. The term ‘princess’ in this context did not necessarily mean the daughter of the emperor but might refer to any other lady of the palace. The first recorded princess bride was Liu Xijun, sent to marry the king of the Wusan tribe at the end of the second century CE. She was not thrilled with her fate, writing in a poem, “My family sent me off in marriage to the end of the world. All day my heart aches with pains of home: Were only I a brown goose and could fly home!”

Wang Zhaojun, Wikimedia Commons

Wang Zhaojun, Wikimedia Commons

Among the most famous such princesses was Wang Zhaojun, who married the Khan of the Southern Xiongnu in 33 BCE. There are many stories about Wang Zhaojun, praising her great beauty and sharp wit. It is said the Chinese emperor had never actually met her when he assigned her to marry the Khan, and that he regretted his choice when he met her, but the treaty was too important to go back on his word. Wang Zhaojun had a son with the Khan and, after her first husband’s death, asked if she could return to China. But Xiongnu custom was for the Khan’s widow to marry his successor, and Chinese Confucian ideals dictated that she stay with her late husband’s family. That is what Wang Zhaojun had to do. She stayed and had additional children with the new Khan. Her children went on to help maintain friendly ties between the Chinese and the Xiongnu. Wang Zhaojun became such a legend in Chinese culture that poetry, art, and even operas were produced to honor her memory for centuries. To many Chinese people, Wang Zhaojun’s acceptance of her role represented a huge personal sacrifice.

Wencheng Gongzhu was another princess who was sent to marry the emperor of Tibet in 641 CE. Her marriage actually brought an immediate end to war between Tibet and the Tang Dynasty in China. Like other princesses before her, Wencheng became a legend in later China because she was said to have been the one to introduce many Chinese innovations to Tibet, thus enlarging the cultural impact of China on much of the Asian continent. In any case, she must have brought a great deal of wealth to her new husband. Her entourage included servants, educators, and inventors. A diplomatic caravan took months to make the journey from the Imperial capital of China to the home of the royal bridegroom. Royal caravans were well-guarded and stopped for days at a time to make sure the bride was not too taxed.

Wencheng Gongzhu was another princess who was sent to marry the emperor of Tibet in 641 CE. Her marriage actually brought an immediate end to war between Tibet and the Tang Dynasty in China. Like other princesses before her, Wencheng became a legend in later China because she was said to have been the one to introduce many Chinese innovations to Tibet, thus enlarging the cultural impact of China on much of the Asian continent. In any case, she must have brought a great deal of wealth to her new husband. Her entourage included servants, educators, and inventors. A diplomatic caravan took months to make the journey from the Imperial capital of China to the home of the royal bridegroom. Royal caravans were well-guarded and stopped for days at a time to make sure the bride was not too taxed.

Bodhisattva from Kucha, 500-700 CE, Wikimedia Commons

Bodhisattva from Kucha, 500-700 CE, Wikimedia Commons

The market towns and oases of the Silk Road were home to hundreds of sedentary peoples who ran the town and catered to the caravans. There would have been women running the inns and selling goods in the market. Buddhism flourished along the Silk Road, and nuns were less likely to travel than Buddhist monks, so the towns were home to women who had taken vows–mostly princesses avoiding arranged marriages. Dunhuang alone was home to five nunneries by the 9th century, the largest of which was home to 200 nuns. Devout Buddhist women who had not taken vows were still able to support the stupa shrines and nunneries with donations.

Some women served as entertainers and courtesans. A steady traffic of travelers created eager audiences, and the art of the Sogdian people was very popular in the oasis towns. The Sogdians occupied what is now Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan. The trademark dance of the 3rd and 4th centuries was a swirling dance in which the dancer whirled inside of a circle to mesmerizing music. Enterprising entertainers also offered Indian-style operas and Chinese drumming.

Larishka is the best-known example of a Silk Road entertainer, although she lived in the 9th century CE, when much of the long distance trade was temporarily interrupted. Regional markets were still thriving and Larishka started out as a singer and dancer in the town of Kucha. As Uyghur armies passed through, however, Larishka caught the eye of a general who took her under his protection. With other servants and enslaved people, she traveled with the army’s caravan. In Dunhuang, she was left behind by her patron but soon picked up by a Chinese general. Later in life, her fortunes changed again and for a time she ran a school in Chang ‘an, where she trained girls to dance and sing. After a violent rebellion took the city, Larishka was forced to flee, and she ended her days as a refugee, arriving back in Kucha with only the clothes on her back.

Whatever else shaped life on the Silk Road, the trade goods themselves deserve a closer look. Silk itself dates back to the Neolithic era in China. According to legend, the princess Xi Lengshi discovered silk fibers when a silk cocoon dropped into her teacup as she relaxed under a mulberry bush. As she watched the cocoon unravel in the warm water, she realized that it was a delicate but strong fiber. For many centuries, China had a monopoly on silk production, and the country profited handsomely. Silk can be easily dyed to almost any color and it can be woven into simple, light fabric or heavy, intricate patterns.

Some women served as entertainers and courtesans. A steady traffic of travelers created eager audiences, and the art of the Sogdian people was very popular in the oasis towns. The Sogdians occupied what is now Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan. The trademark dance of the 3rd and 4th centuries was a swirling dance in which the dancer whirled inside of a circle to mesmerizing music. Enterprising entertainers also offered Indian-style operas and Chinese drumming.

Larishka is the best-known example of a Silk Road entertainer, although she lived in the 9th century CE, when much of the long distance trade was temporarily interrupted. Regional markets were still thriving and Larishka started out as a singer and dancer in the town of Kucha. As Uyghur armies passed through, however, Larishka caught the eye of a general who took her under his protection. With other servants and enslaved people, she traveled with the army’s caravan. In Dunhuang, she was left behind by her patron but soon picked up by a Chinese general. Later in life, her fortunes changed again and for a time she ran a school in Chang ‘an, where she trained girls to dance and sing. After a violent rebellion took the city, Larishka was forced to flee, and she ended her days as a refugee, arriving back in Kucha with only the clothes on her back.

Whatever else shaped life on the Silk Road, the trade goods themselves deserve a closer look. Silk itself dates back to the Neolithic era in China. According to legend, the princess Xi Lengshi discovered silk fibers when a silk cocoon dropped into her teacup as she relaxed under a mulberry bush. As she watched the cocoon unravel in the warm water, she realized that it was a delicate but strong fiber. For many centuries, China had a monopoly on silk production, and the country profited handsomely. Silk can be easily dyed to almost any color and it can be woven into simple, light fabric or heavy, intricate patterns.

Women Making Silk, Wikimedia Commons

Women Making Silk, Wikimedia Commons

Women were usually entrusted with caring for silkworms, processing of the fiber, and weaving the cloth. China was so invested in supporting this industry that families willing to dedicate even a small plot of land to mulberry bushes and silkworm farming earned tax exemptions and other benefits. Thus, the work women did helped to support their families.

Silk was an ideal trade product. It was as valuable as gold but was far lighter, so it was easy to carry. In many cases, wages were paid in bolts of silk fabric. Silk was also among the sapta vatna, or the “Seven Treasures” of Buddhism. Silk was central to Buddhist worship and the veneration of the Buddha. In Persian and Roman elite families, wearing silk was a mark of status and wealth. Romans loved the fabric so much that

they often unwound heavier cloth to make sheer fabrics and increase their profit Conservative Romans were scandalized at the almost transparent outfits of the rich and famous women of the city. Pliny the Elder complained further that the eastern trade in luxury goods was bankrupting the great Roman families. Romans had no idea what silk was made of—they thought it was a plant. Persians were among the first to learn the secrets of silk, and some stories suggest that a resentful princess bride hid silk cocoons in her elaborate headdress as a gift to her Persian husband.

A pearl is formed when a microscopic irritant gets stuck inside a bivalve like a clam or an oyster. The bivalve will naturally protect itself by developing a smooth layer around the irritant. This layer is made of the same smooth and shiny layer that lines the shell as the creature grows. For thousands of years, natural pearls were harvested from the Persian Gulf, the Red Sea, the Indian Ocean and the Gulf of Mannar in Sri Lanka. During the Han Dynasty, a pearl industry emerged in the South China Sea.

Silk was an ideal trade product. It was as valuable as gold but was far lighter, so it was easy to carry. In many cases, wages were paid in bolts of silk fabric. Silk was also among the sapta vatna, or the “Seven Treasures” of Buddhism. Silk was central to Buddhist worship and the veneration of the Buddha. In Persian and Roman elite families, wearing silk was a mark of status and wealth. Romans loved the fabric so much that

they often unwound heavier cloth to make sheer fabrics and increase their profit Conservative Romans were scandalized at the almost transparent outfits of the rich and famous women of the city. Pliny the Elder complained further that the eastern trade in luxury goods was bankrupting the great Roman families. Romans had no idea what silk was made of—they thought it was a plant. Persians were among the first to learn the secrets of silk, and some stories suggest that a resentful princess bride hid silk cocoons in her elaborate headdress as a gift to her Persian husband.

A pearl is formed when a microscopic irritant gets stuck inside a bivalve like a clam or an oyster. The bivalve will naturally protect itself by developing a smooth layer around the irritant. This layer is made of the same smooth and shiny layer that lines the shell as the creature grows. For thousands of years, natural pearls were harvested from the Persian Gulf, the Red Sea, the Indian Ocean and the Gulf of Mannar in Sri Lanka. During the Han Dynasty, a pearl industry emerged in the South China Sea.

Silk Road Market Place, Public Domain

Silk Road Market Place, Public Domain

n India, the pearl industry employed both men and women. Though the pearl trade was highly profitable, the danger of pearl diving and the tedium of shucking oysters meant that the real labor was carried out by low-ranking people who rarely got rich from the pearl industry.

Finally, the impact of women on the Silk Road resided in their activities as consumers. In many cases, women bought the trade goods that made life sweet—silks to wear, art to decorate their homes, and spices to flavor their food. A 1st century Roman cookbook by Apicius includes pepper, ginger, turmeric, and other eastern ingredients in just about every recipe. While all elites could enjoy fine dining and beautiful clothing, Pliny the Elder blamed the expensive tastes of women for the money Romans wasted on eastern goods. He himself lived in a splendid oceanside estate but it was the pearls, gems, and silk worn by women that offended him. At the same time, Roman sources reveal that eastern trade goods appealed to many women for reasons deeper than vanity or decadence.

As in Buddhist traditions further east, the traditional religions and mystery cults of the Roman Empire placed a high value on the incense and spices used in prayer. Spices were also used in medicine.

The Silk Road trade routes have shifted along with every political and economic change over time. Some parts of the network still exist today or are in the midst of being recreated. But for centuries, the great empires of Europe, Africa, and Asia did business with each other in ports and markets run by regular folk.

Finally, the impact of women on the Silk Road resided in their activities as consumers. In many cases, women bought the trade goods that made life sweet—silks to wear, art to decorate their homes, and spices to flavor their food. A 1st century Roman cookbook by Apicius includes pepper, ginger, turmeric, and other eastern ingredients in just about every recipe. While all elites could enjoy fine dining and beautiful clothing, Pliny the Elder blamed the expensive tastes of women for the money Romans wasted on eastern goods. He himself lived in a splendid oceanside estate but it was the pearls, gems, and silk worn by women that offended him. At the same time, Roman sources reveal that eastern trade goods appealed to many women for reasons deeper than vanity or decadence.

As in Buddhist traditions further east, the traditional religions and mystery cults of the Roman Empire placed a high value on the incense and spices used in prayer. Spices were also used in medicine.

The Silk Road trade routes have shifted along with every political and economic change over time. Some parts of the network still exist today or are in the midst of being recreated. But for centuries, the great empires of Europe, Africa, and Asia did business with each other in ports and markets run by regular folk.

Draw your own conclusions

|

Learn how to teach with inquiry.

Many of these lesson plans were sponsored in part by the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources Eastern Region Program, coordinated by Waynesburg University, the History and Social Studies Education Faculty at Plymouth State University, and the Patrons of the Remedial Herstory Project. |

Lesson Plans from Other Organizations

- This website, Women in World History has primary source based lesson plans on women's history in a whole range of topics. Some are free while others have a cost.

- The Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media has produced recommendations for teaching women's history with primary sources and provided a collection of sources for world history. Check them out!

- The Stanford History Education Group has a number of lesson plans about women in World History.

Princess Xijun: Poem

Xijun was sent to marry the king of the Wusun people to create a political alliance. She did not even speak the language of her husband and his culture was very different from the Chinese royal court.

My people have married me

In a far corner of Earth:

Sent me away to a strange land,

To the king of the Wu-sun.

A tent is my house,

Of felt are my walls;

Raw flesh my food

With mare's milk to drink.

Always thinking of my own country,

My heart sad within.

Would I were a yellow stork

And could fly to my old home!

Waley, Arthur. Trans. A Hundred and Seventy Chinese Poems. New York: Knopf, 1918.

Questions:

My people have married me

In a far corner of Earth:

Sent me away to a strange land,

To the king of the Wu-sun.

A tent is my house,

Of felt are my walls;

Raw flesh my food

With mare's milk to drink.

Always thinking of my own country,

My heart sad within.

Would I were a yellow stork

And could fly to my old home!

Waley, Arthur. Trans. A Hundred and Seventy Chinese Poems. New York: Knopf, 1918.

Questions:

- What are the circumstances that lead to Princess Xijun writing this poem?

- What feelings are Princess Xijun trying to portray in her writing?

Miwnay: Sogdian Letter No.3

Miwnay was a Sogdian woman left in Dunhuang, China, by her husband Nanai-dhat, who had not paid his debts. She wrote to him and in a separate letter to her mother, asking for their support in leaving the market town to go home.

To my noble lord and husband Nanai-dhat, blessing and homage on bended knee, as is offered to the gods. And it would be a good day for him who might see you healthy, happy and free from illness, together with everyone; and, sir, when I hear news of your good health, I consider myself immortal!

Behold, I am living ..., badly, not well, wretchedly, and I consider myself dead. Again and again, I send you a letter, but I do not receive a single letter from you, and I have become without hope towards you. My misfortune is this, that I have been in Dunhuang for three years thanks to you, and there was a way out a first, a second, even a fifth time*, but he refused to bring me out. I requested the leaders that support should be given to Farnkhund for me, so that he may take me to my husband and I would not be stuck in Dunhuang, for Farnkhund says: I am not Nanai-dhat’s servant, nor do I hold his capital. . . And you write your bidding to me about everything . . . then you write to me so that I should know how to serve the Chinese. . .I obeyed your command and came to Dunhuang and I did not observe my mother’s bidding nor my brothers’. Surely the gods were angry with me on the day when I did your bidding! I would rather be a dog’s or a pig’s wife than yours!

Sent by (your) servant Miwnay. This letter was written in the third month on the tenth day.

[Added in the margin] From his daughter Shayn to the noble lord Nanai-dhat, blessing and homage. And it would be a good day for him who might see you healthy, rested and happy. ... I watch over a flock of domestic animals. . . I know that you do not lack twenty staters to send. It is necessary to consider the whole matter. Farnkhund has run away; the Chinese seek him but do not find him. Because of Farnkhund’s debts we have become the servants of the Chinese, I together with my mother.

* She lists their chances to leave by joining a caravan, but they did not have the money to do so.

Whitfield, Susan, and Ursula Sims-Williams, eds. The Silk Road: Trade, Travel, War, and Faith. Chicago: Serindia Publications, 2004. Pp. 248-9.

To my noble lord and husband Nanai-dhat, blessing and homage on bended knee, as is offered to the gods. And it would be a good day for him who might see you healthy, happy and free from illness, together with everyone; and, sir, when I hear news of your good health, I consider myself immortal!

Behold, I am living ..., badly, not well, wretchedly, and I consider myself dead. Again and again, I send you a letter, but I do not receive a single letter from you, and I have become without hope towards you. My misfortune is this, that I have been in Dunhuang for three years thanks to you, and there was a way out a first, a second, even a fifth time*, but he refused to bring me out. I requested the leaders that support should be given to Farnkhund for me, so that he may take me to my husband and I would not be stuck in Dunhuang, for Farnkhund says: I am not Nanai-dhat’s servant, nor do I hold his capital. . . And you write your bidding to me about everything . . . then you write to me so that I should know how to serve the Chinese. . .I obeyed your command and came to Dunhuang and I did not observe my mother’s bidding nor my brothers’. Surely the gods were angry with me on the day when I did your bidding! I would rather be a dog’s or a pig’s wife than yours!

Sent by (your) servant Miwnay. This letter was written in the third month on the tenth day.

[Added in the margin] From his daughter Shayn to the noble lord Nanai-dhat, blessing and homage. And it would be a good day for him who might see you healthy, rested and happy. ... I watch over a flock of domestic animals. . . I know that you do not lack twenty staters to send. It is necessary to consider the whole matter. Farnkhund has run away; the Chinese seek him but do not find him. Because of Farnkhund’s debts we have become the servants of the Chinese, I together with my mother.

* She lists their chances to leave by joining a caravan, but they did not have the money to do so.

Whitfield, Susan, and Ursula Sims-Williams, eds. The Silk Road: Trade, Travel, War, and Faith. Chicago: Serindia Publications, 2004. Pp. 248-9.

Excerpt From the Debate on Salt and Iron

In 81 BCE, the Han emperor called together a meeting of scholars to debate the success of various economic policies. In this excerpt, the officials defend the previous emperor’s program to regulate prices by buying up goods and selling them only after the prices have gone up. The scholars reply by pointing out the program created extra hardships for the people who make the goods.

His Lordship stated: In former times the peers residing in the provinces sent in their respective products as tribute, but there was much confusion and trouble in transporting them and the goods were often of such poor quality that they were not worth the cost of transportation. For this reason, transportation offices have been set up in each district to handle delivery and shipping and to facilitate the presentation of tribute from outlying areas. Therefore, the system is called “equitable marketing.” Warehouses have been opened in the capital for the storing of goods, buying when prices are low and selling when they are high. Thereby the government suffers no loss, and the merchants cannot speculate for profit. Therefore, this is called the “balanced level” [stabilization]. With the balanced level the people are protected from unemployment, and with equitable marketing the burden of labor service is equalized. Thus, these measures are designed to ensure an equal distribution of goods and to benefit the people and are not intended to open the way to profit or provide the people with a ladder to crime.

The Confucian literati replied: In ancient times taxes and levies took from the people what they were skilled in producing and did not demand what they were poor at. Thus, the husbandmen sent in their harvests and the weaving women their goods. Nowadays the government disregards what people have and requires of them what they have not, so that they are forced to sell their goods at a cheap price in order to meet the demands from above. …The farmers suffer double hardships and the weaving women are taxed twice. We have not seen that this kind of marketing is “equitable.” The government officials go about recklessly opening closed doors and buying everything at will so they can corner all the goods. With goods cornered prices soar, and when prices soar the merchants make their own deals for profit. The officials wink at powerful racketeers, and the rich merchants hoard commodities and wait for an emergency. With slick merchants and corrupt officials buying cheap and selling dear we have not seen that your level is “balanced.” The system of equitable marketing of ancient times was designed to equalize the burden of labor upon the people and facilitate the transporting of tribute. It did not mean dealing in all kinds of commodities for the sake of profit.

From Sources of Chinese Tradition, compiled by Wm. Theodore de Bary and Irene Bloom, 2nd ed., vol. 1 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999), 360-363.

Questions:

This text outlines the impact of state policy and regular subjects of a large state. What are the Confucian scholars recommending to the court officials and why?

His Lordship stated: In former times the peers residing in the provinces sent in their respective products as tribute, but there was much confusion and trouble in transporting them and the goods were often of such poor quality that they were not worth the cost of transportation. For this reason, transportation offices have been set up in each district to handle delivery and shipping and to facilitate the presentation of tribute from outlying areas. Therefore, the system is called “equitable marketing.” Warehouses have been opened in the capital for the storing of goods, buying when prices are low and selling when they are high. Thereby the government suffers no loss, and the merchants cannot speculate for profit. Therefore, this is called the “balanced level” [stabilization]. With the balanced level the people are protected from unemployment, and with equitable marketing the burden of labor service is equalized. Thus, these measures are designed to ensure an equal distribution of goods and to benefit the people and are not intended to open the way to profit or provide the people with a ladder to crime.

The Confucian literati replied: In ancient times taxes and levies took from the people what they were skilled in producing and did not demand what they were poor at. Thus, the husbandmen sent in their harvests and the weaving women their goods. Nowadays the government disregards what people have and requires of them what they have not, so that they are forced to sell their goods at a cheap price in order to meet the demands from above. …The farmers suffer double hardships and the weaving women are taxed twice. We have not seen that this kind of marketing is “equitable.” The government officials go about recklessly opening closed doors and buying everything at will so they can corner all the goods. With goods cornered prices soar, and when prices soar the merchants make their own deals for profit. The officials wink at powerful racketeers, and the rich merchants hoard commodities and wait for an emergency. With slick merchants and corrupt officials buying cheap and selling dear we have not seen that your level is “balanced.” The system of equitable marketing of ancient times was designed to equalize the burden of labor upon the people and facilitate the transporting of tribute. It did not mean dealing in all kinds of commodities for the sake of profit.

From Sources of Chinese Tradition, compiled by Wm. Theodore de Bary and Irene Bloom, 2nd ed., vol. 1 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999), 360-363.

Questions:

This text outlines the impact of state policy and regular subjects of a large state. What are the Confucian scholars recommending to the court officials and why?

Pliny the Elder: Natural History

Pliny the Elder was a Roman author and naturalist who dedicated his “Natural History,” a kind of encyclopedia, to the Emperor Titus in 77 CE. He attributes the discovery of silk to a Greek woman but also uses the entry to criticize the flimsy fashions favored by the women of Rome.

CHAP. 26.—THE LARVÆ OF THE SILK-WORM-WHO FIRST INVENTED SILK CLOTHS.

There is another class also of these insects produced in quite a different manner. These last spring from a grub of larger size, with two horns of very peculiar appearance. The larva then becomes a caterpillar, after which it assumes the state in which it is known as bombylis, then that called necy- dalus, and after that, in six months, it becomes a silk-worm. These insects weave webs similar to those of the spider, the material of which is used for making the more costly and luxurious garments of females, known as " bombycina." Pamphile, a woman of Cos, the daughter of Platea, was the first person who discovered the art of unravelling these webs and spinning a tissue therefrom; indeed, she ought not to be deprived of the glory of having discovered the art of making vestments which, while they cover a woman, at the same moment reveal her naked charms.

CHAP. 27. (23.)—THE SILK-WORM OF COS—HOW THE COAN VESTMENTS ARE MADE.

The silk-worm, too, is said to be a native of the isle of Cos, where the vapours of the earth give new life to the flowers of the cypress, the terebinth, the ash, and the oak which have been beaten down by the showers. At first they assume the appearance of small butterflies with naked bodies, but soon after, being unable to endure the cold, they throw out bristly hairs, and assume quite a thick coat against the winter, by rubbing off the down that covers the leaves, by the aid of the roughness of their feet. This they compress into balls by carding it with their claws, and then draw it out and hang it between the branches of the trees, making it fine by combing it out as it were: last of all, they take and roll it round their body, thus forming a nest in which they are enveloped. It is in this state that they are taken; after which they are placed in earthen vessels in a warm place, and fed upon bran. A peculiar sort of down soon shoots forth upon the body, on being clothed with which they are sent to work upon another task. The cocoons which they have begun to form are rendered soft and pliable by the aid of water, and are then drawn out into threads by means of a spindle made of a reed. Nor, in fact, have the men even felt ashamed to make use of garments formed of this material, in consequence of their extreme lightness in summer: for, so greatly have manners degenerated in our day, that, so far from wearing a cuirass, a garment even is found to be too heavy. The produce of the Assyrian silk-worm, however, we have till now left to the women only.

The Natural History. Pliny the Elder. John Bostock, M.D., F.R.S. H.T. Riley, Esq., B.A. London. Taylor and Francis, Red Lion Court, Fleet Street. 1855. Book XI, pp 25-6.

CHAP. 26.—THE LARVÆ OF THE SILK-WORM-WHO FIRST INVENTED SILK CLOTHS.

There is another class also of these insects produced in quite a different manner. These last spring from a grub of larger size, with two horns of very peculiar appearance. The larva then becomes a caterpillar, after which it assumes the state in which it is known as bombylis, then that called necy- dalus, and after that, in six months, it becomes a silk-worm. These insects weave webs similar to those of the spider, the material of which is used for making the more costly and luxurious garments of females, known as " bombycina." Pamphile, a woman of Cos, the daughter of Platea, was the first person who discovered the art of unravelling these webs and spinning a tissue therefrom; indeed, she ought not to be deprived of the glory of having discovered the art of making vestments which, while they cover a woman, at the same moment reveal her naked charms.

CHAP. 27. (23.)—THE SILK-WORM OF COS—HOW THE COAN VESTMENTS ARE MADE.

The silk-worm, too, is said to be a native of the isle of Cos, where the vapours of the earth give new life to the flowers of the cypress, the terebinth, the ash, and the oak which have been beaten down by the showers. At first they assume the appearance of small butterflies with naked bodies, but soon after, being unable to endure the cold, they throw out bristly hairs, and assume quite a thick coat against the winter, by rubbing off the down that covers the leaves, by the aid of the roughness of their feet. This they compress into balls by carding it with their claws, and then draw it out and hang it between the branches of the trees, making it fine by combing it out as it were: last of all, they take and roll it round their body, thus forming a nest in which they are enveloped. It is in this state that they are taken; after which they are placed in earthen vessels in a warm place, and fed upon bran. A peculiar sort of down soon shoots forth upon the body, on being clothed with which they are sent to work upon another task. The cocoons which they have begun to form are rendered soft and pliable by the aid of water, and are then drawn out into threads by means of a spindle made of a reed. Nor, in fact, have the men even felt ashamed to make use of garments formed of this material, in consequence of their extreme lightness in summer: for, so greatly have manners degenerated in our day, that, so far from wearing a cuirass, a garment even is found to be too heavy. The produce of the Assyrian silk-worm, however, we have till now left to the women only.

The Natural History. Pliny the Elder. John Bostock, M.D., F.R.S. H.T. Riley, Esq., B.A. London. Taylor and Francis, Red Lion Court, Fleet Street. 1855. Book XI, pp 25-6.

Remedial Herstory Editors. "10. 100-500 WOMEN TRAVELERS AND MERCHANTS ON THE SILK ROADS." The Remedial Herstory Project. November 1, 2022. www.remedialherstory.com.

AUTHOR: |

Dr. Nancy Locklin-Sofer

|

Primary Reviewer: |

Kelsie Brook Eckert

|

Consulting Team |

Editors |

|

Kelsie Brook Eckert, Project Director

Coordinator of Social Studies Education at Plymouth State University Dr. Nancy Locklin-Sofer, Consultant Professor of History at Maryville College. Chloe Gardner, Consultant PhD Candidate in Religious Studies at Edinburgh University Dr. Whitney Howarth, Consultant Former Professor of History at Plymouth State University Jacqui Nelson, Consultant Teaching Lecturer of Military History at Plymouth State University Maria Concepcion Marquez Sandoval PhD Candidate in History at Arizona University |

Chris Canfield

Humanities Teacher, Moultonborough Academy ReviewersAncient:

Dr. Kristin Heineman Professor of History at Colorado State University Dr. Bonnie Rock-McCutcheon Professor of History at Wilson College Sarah Stone PhD Candidate in Religious Studies at Edinburgh University Medieval: Dr. Katherine Koh Professor of History at La Sierra University Dr. Jonathan Couser Professor of History at Plymouth State University Dr. Shahla Haeri Professor of History at Boston University Lauren Cole PhD Candidate in History at Northwestern University Modern: Dr. Barbara Tischler Supervisor for Hunter College Dr. Pamela Scully Professor of Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies and African Studies at Emory University |

|

Empress Wu Zetian (624-705 AD) was the only woman to be the sovereign ruler of imperial China. She ruled in the name of her husband and two eldest sons, presiding over the pinnacle of the Silk Road, before proclaiming herself the founder of a new dynasty. So charismatic that she could rise from nothing to the height of medieval power, so hated that her own children left her tombstone blank.

Fascinating stories of four legendary women of ancient China, all in one volume - reflecting the culture and tumultuous events of those times, where intelligence and creative talent emerged through strength of character. Ancient China was a "man's world", and so for a woman to excel was like throwing a stone into the air and expecting it to remain. These four women are brought to life by the author, showing their character; their intelligence; their capacity to love; and most important their resilience. At the end of the book, each will be your sister, where you will weep or celebrate as they did.

|

|

|

Daughters of the Silk Road follows the journey of a family of merchant explorers who return to Venice from China with a Ming Vase. The book again straddles two time zones.

|

|

Bibliography

Brown, Peter. “The Silk Road in Late Antiquity” in Reconfiguring the Silk Road, ed. By Victor H. Mair & Jane Hickman. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014.

Fitzpatrick, Matthew P. “Provincializing Rome: The Indian Ocean Trade Network and Roman Imperialism.” The Journal of World History, Vol. 22, No. 1 (March 2011), pp. 27-54.

Hansen, Valerie. The Silk Road: A New History. Oxford University Press, 2015.

Holmgren, Jennifer. “A Question of Strength: Military Capability and Princess-Bestowal in Imperial China’s Foreign Relations (Han to Ch’ing).” Monumenta Serica, Vol. 39 (1990-1991), pp. 31-85.

Miles, Rosalind. The Women’s History of the World. London, UK: Harper Collins Publishers, 1988.

Pi-Wei Lei, Daphne. “Wang Zhaojun on the Border: Gender and Intercultural Conflicts in Premodern Chinese Drama.” Asian Theatre Journal, Vol. 13, No. 2 (Autumn, 1996), pp. 229-237.

Pollard, Elizabeth Ann. “Indian Spices and Roman ‘Magic’ in Imperial and Late Antique Indo Mediterranea.” The Journal of World History, Vol. 24, No. 1 (March 2013), pp. 1-23.

Strayer, R. and Nelson, E., Ways Of The World. 3rd ed. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2016.

Whitfield, Susan. Life along the Silk Road. University of California Press, 2015.

Wright, David Curtis. “A Chinese Princess Bride’s Life and Activism among the Eastern Turks, 580-593 CE.” Journal of Asian History, Vol. 45, No. ½ (2011), pp. 39-48.

Fitzpatrick, Matthew P. “Provincializing Rome: The Indian Ocean Trade Network and Roman Imperialism.” The Journal of World History, Vol. 22, No. 1 (March 2011), pp. 27-54.

Hansen, Valerie. The Silk Road: A New History. Oxford University Press, 2015.

Holmgren, Jennifer. “A Question of Strength: Military Capability and Princess-Bestowal in Imperial China’s Foreign Relations (Han to Ch’ing).” Monumenta Serica, Vol. 39 (1990-1991), pp. 31-85.

Miles, Rosalind. The Women’s History of the World. London, UK: Harper Collins Publishers, 1988.

Pi-Wei Lei, Daphne. “Wang Zhaojun on the Border: Gender and Intercultural Conflicts in Premodern Chinese Drama.” Asian Theatre Journal, Vol. 13, No. 2 (Autumn, 1996), pp. 229-237.

Pollard, Elizabeth Ann. “Indian Spices and Roman ‘Magic’ in Imperial and Late Antique Indo Mediterranea.” The Journal of World History, Vol. 24, No. 1 (March 2013), pp. 1-23.

Strayer, R. and Nelson, E., Ways Of The World. 3rd ed. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2016.

Whitfield, Susan. Life along the Silk Road. University of California Press, 2015.

Wright, David Curtis. “A Chinese Princess Bride’s Life and Activism among the Eastern Turks, 580-593 CE.” Journal of Asian History, Vol. 45, No. ½ (2011), pp. 39-48.