17. 1000-1600 Gender Dynamics in New Worlds

|

The “New World” was what those in the Afro-Eurasian nations used to describe the Americas “discovered” or, rather, rediscovered by Columbus in 1492. Even before that, Europeans explored south along the west coast of Africa looking for a sea route to India. Before the arrival of European explorers, the people living in Mesoamerica, Oceania, and Africa had rich cultures and empires with their own gendered dynamics and attitudes.

|

traditional Polynesian mat, wikimedia commons

traditional Polynesian mat, wikimedia commons

Across great swaths of ocean from the Afro-Eurasia world, entire civilizations were thriving in what today we know as Mesoamerica, Oceania, and Africa. The civilizations were isolated from one another and the rest of the world, so cultural diffusion did not play a major role. Cultural developments that existed in the "Old World" were also in evidence in Mesoamerica and Oceania. For those in the "Old World'' these territories were unknown, but technology was developing at a rate that would allow for exploration and sustained connection to far away places.

Oceania

People of Pacific Oceania created enduring cultures that didn't have large cities, states, or empires. They settled in the islands of southeast Asia, Micronesia, and Melanesia as late as 50 thousand years ago. Polynesia, which goes further into the Pacific was likely unsettled until about 3,500 years ago. Societies in general were arranged around patriarchal chiefdoms ruled by councils, so chiefs didn’t have an elevated status. Some islands, such as the Hawaiians, had powerful patriarchal rulers with thousands of warriors at their disposal.

Melanesian women saw strict gender stratification, where Polynesian women, further out at sea had greater political influence. Women in Oceania were, like the rest of the world, considered dangerous and foul, especially during menstruation. The word “taboo” is derived from the Polynesian word for menstruation or, “tapu,” which means a holy prohibition, something not to be touched. Whether this was intended as a condemnation or an elevation, is lost to the history of colonization.

Oceania

People of Pacific Oceania created enduring cultures that didn't have large cities, states, or empires. They settled in the islands of southeast Asia, Micronesia, and Melanesia as late as 50 thousand years ago. Polynesia, which goes further into the Pacific was likely unsettled until about 3,500 years ago. Societies in general were arranged around patriarchal chiefdoms ruled by councils, so chiefs didn’t have an elevated status. Some islands, such as the Hawaiians, had powerful patriarchal rulers with thousands of warriors at their disposal.

Melanesian women saw strict gender stratification, where Polynesian women, further out at sea had greater political influence. Women in Oceania were, like the rest of the world, considered dangerous and foul, especially during menstruation. The word “taboo” is derived from the Polynesian word for menstruation or, “tapu,” which means a holy prohibition, something not to be touched. Whether this was intended as a condemnation or an elevation, is lost to the history of colonization.

Depiction of the goddess Hina, Bridgeman Images

Depiction of the goddess Hina, Bridgeman Images

As in most of the world, Oceania peoples idealized motherhood as nurturing, sheltering, cleansing, fertile, and chaste. They simultaneously displayed a sense of terror toward the dangerous, mystical, and carnal feminine qualities. One scholar observed, "Sensualism, eroticism, and a high level of sexual activity are actively cultivated throughout the area. Homosexuality is unstigmatized. Relations between men and women are relatively harmonious and mutually respectful.”

Polynesian women were heavily involved in productive labor, including food production and making mats and clothes. Agricultural labor was divided between the sexes. In some places, men cleared land and women planted. In other locales,, crops were divided by gender, with men maintaining cash crops like bananas and women tending staple crops for sustenance. Aboriginal women labored in the water all day, fishing and gathering underwater roots. On the islands of Hawaii, for example, women built offshore dams to trap fish by the shore and provide their community a consistent food supply. They labored daily in their canoes and on the beaches all while caring for babies.

Religious life in Oceania was polytheistic. Gods and goddesses had intricate relationships that affected human life. One common tale throughout Polynesian cultures was about a woman named Hina. She established women's work. In the story, she falls in love with a handsome chief from faraway lands and swims to him across the ocean, abandoning her family. In another version, she is seduced by an eel while bathing. The demi-God Maui intervenes by killing the eel. She buries her lover and a coconut tree grew from the grave. The Maori in New Zealand have a similar story where the eel is chopped into so many pieces, it turns into the various species of eel. In her grief, Hina fled to the moon where she remained. A common Oceanic belief is that the moon is the true husband of all women.

Polynesian peoples traveled as far as the west coast of South America and brought back sweet potatoes and other goods, but it would be for later people from distant lands to create a sustained connection across these cultures.

Polynesian women were heavily involved in productive labor, including food production and making mats and clothes. Agricultural labor was divided between the sexes. In some places, men cleared land and women planted. In other locales,, crops were divided by gender, with men maintaining cash crops like bananas and women tending staple crops for sustenance. Aboriginal women labored in the water all day, fishing and gathering underwater roots. On the islands of Hawaii, for example, women built offshore dams to trap fish by the shore and provide their community a consistent food supply. They labored daily in their canoes and on the beaches all while caring for babies.

Religious life in Oceania was polytheistic. Gods and goddesses had intricate relationships that affected human life. One common tale throughout Polynesian cultures was about a woman named Hina. She established women's work. In the story, she falls in love with a handsome chief from faraway lands and swims to him across the ocean, abandoning her family. In another version, she is seduced by an eel while bathing. The demi-God Maui intervenes by killing the eel. She buries her lover and a coconut tree grew from the grave. The Maori in New Zealand have a similar story where the eel is chopped into so many pieces, it turns into the various species of eel. In her grief, Hina fled to the moon where she remained. A common Oceanic belief is that the moon is the true husband of all women.

Polynesian peoples traveled as far as the west coast of South America and brought back sweet potatoes and other goods, but it would be for later people from distant lands to create a sustained connection across these cultures.

Teotihuacan city-state, wikimedia commons

Teotihuacan city-state, wikimedia commons

Mesoamerican Cultures

The Americas have been settled by humans for tens of thousands of years. After likely prehistoric crossings on a land bridge, city-states and empires thrived as early as 2000 CE under the Maya, Olmecs, Chavin, and the Norte Chico– preceding the Aztecs and the Incas by a millennia.

Without the large domesticated animals found in the Old World, labor and production functioned differently here. As in much of the ancient Old World, Indigenous people practiced polytheistic religions featuring male and female gods and goddesses. These societies had writing, a robust calendar, social structures, systems of exchange, and imposing pyramids and city centers. Wherever these standards of “civilization” exist, so did expectations for women.

While much is known about Aztec and Incan gender dynamics, less is known about some of the major empires and city states that preceded them such as the Maya, Teotihuacan, Chavin, Olmec, and Moche.

The Mayan people constructed city-states as early as 2000 BCE that were home to as many as 50 thousand people. built as far back as 2000 BCE in present-day Guatemala and the Yucatán region of Mexico. They thrived until 900 CE making important discoveries in math and navigation and recording historic events in writing.

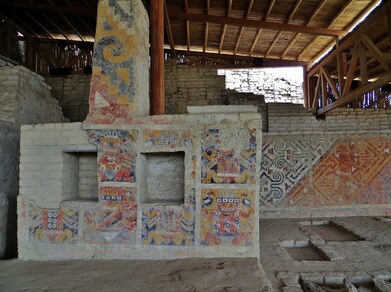

Teotihuacan was the largest city-state in Mesoamerica, located in modern-day Mexico. It was home to as many as 10,100 thousand people and boasted massive temples, including the Pyramid of the Sun, believed to be the site of creation itself. Very little is known about how the city was governed because the culture did not have the dynastic art and writing of the Maya. This great city got its name from the Aztec empire, calling it "the city of the gods."

The Americas have been settled by humans for tens of thousands of years. After likely prehistoric crossings on a land bridge, city-states and empires thrived as early as 2000 CE under the Maya, Olmecs, Chavin, and the Norte Chico– preceding the Aztecs and the Incas by a millennia.

Without the large domesticated animals found in the Old World, labor and production functioned differently here. As in much of the ancient Old World, Indigenous people practiced polytheistic religions featuring male and female gods and goddesses. These societies had writing, a robust calendar, social structures, systems of exchange, and imposing pyramids and city centers. Wherever these standards of “civilization” exist, so did expectations for women.

While much is known about Aztec and Incan gender dynamics, less is known about some of the major empires and city states that preceded them such as the Maya, Teotihuacan, Chavin, Olmec, and Moche.

The Mayan people constructed city-states as early as 2000 BCE that were home to as many as 50 thousand people. built as far back as 2000 BCE in present-day Guatemala and the Yucatán region of Mexico. They thrived until 900 CE making important discoveries in math and navigation and recording historic events in writing.

Teotihuacan was the largest city-state in Mesoamerica, located in modern-day Mexico. It was home to as many as 10,100 thousand people and boasted massive temples, including the Pyramid of the Sun, believed to be the site of creation itself. Very little is known about how the city was governed because the culture did not have the dynastic art and writing of the Maya. This great city got its name from the Aztec empire, calling it "the city of the gods."

Lady Cao's Tomb, Public Domain

Lady Cao's Tomb, Public Domain

In the Andes mountains, several distinct cultures emerged: the Chavin, Tiwanaku, Wari, and Moche civilizations. The Chavin didn’t develop an empire but left a ritualistic cult that used hallucinations. They left us some epic paintings of jaguar-humans. The Tiwanaku and Wari lived near each other in the interior but didn’t interact. They left impressive agricultural and irrigation systems as well as highways that the Inca would later expand.

A little more is known about gender dynamics in Moche civilization, which flourished between 100 and 800 CE. The Moche had complex irrigation systems that supported crops such as maize, beans, squash, and cotton. They also used hallucinogens in their religious practice. They had elaborate rituals where shaman-rulers would mediate between the world of humankind and that of the gods. They practiced human sacrifice, with victims usually drawn from prisoners of war. There's an absence of written text, so a lot of what we know about the Moche people comes from grave sites for the elite, which boasted jewels and goods to rival the Ancient Egyptian burial sites. Their ceramic pottery had portraits of lords and rulers, as well as images of the lives of common people. These included erotic or sexual encounters between men and women, as well as between gods and humans.

“Lady Cao” as she was known, was a remarkable woman whose gravesite was uncovered in 2005. She was clearly of the elite. In her tomb, she was ornamented in tattoos, nose rings, and other jewels and had grave goods including jewels, weaving tools, and a vessel depicting a nursing mother. She died in her twenties in childbirth and was carefully wrapped in hundreds of yards of cotton strips. Scholars believe she was a ruler because she had the same “masculine” images of war, staffs that were symbols of authority, along with many weapons to accompany her in the afterlife. The case for her being a ruler in her own right was supported by the discovery of other sites also featuring elite Moche women. Experts believe that society was relatively decentralized and that this supported the existence of female leaders.

A little more is known about gender dynamics in Moche civilization, which flourished between 100 and 800 CE. The Moche had complex irrigation systems that supported crops such as maize, beans, squash, and cotton. They also used hallucinogens in their religious practice. They had elaborate rituals where shaman-rulers would mediate between the world of humankind and that of the gods. They practiced human sacrifice, with victims usually drawn from prisoners of war. There's an absence of written text, so a lot of what we know about the Moche people comes from grave sites for the elite, which boasted jewels and goods to rival the Ancient Egyptian burial sites. Their ceramic pottery had portraits of lords and rulers, as well as images of the lives of common people. These included erotic or sexual encounters between men and women, as well as between gods and humans.

“Lady Cao” as she was known, was a remarkable woman whose gravesite was uncovered in 2005. She was clearly of the elite. In her tomb, she was ornamented in tattoos, nose rings, and other jewels and had grave goods including jewels, weaving tools, and a vessel depicting a nursing mother. She died in her twenties in childbirth and was carefully wrapped in hundreds of yards of cotton strips. Scholars believe she was a ruler because she had the same “masculine” images of war, staffs that were symbols of authority, along with many weapons to accompany her in the afterlife. The case for her being a ruler in her own right was supported by the discovery of other sites also featuring elite Moche women. Experts believe that society was relatively decentralized and that this supported the existence of female leaders.

Depiction of Mama Huaco, Wikimedia Commons

Depiction of Mama Huaco, Wikimedia Commons

Inca

Women held power in Inca society as queen consorts and some wielded power in their own right. The Incan empire traces its roots to a woman, Mama Huaco, the first Quoya or Queen. She ruled the empire outright. Other Quoyas who followed held varying degrees of power as the primary wife of the king with the title “Queen of all women.” Quoyas presided over the kingdom in their husbands’ absence and acted as tiebreaker when the leadership was stalemated. Outside the heart of the empire, women became “Kurakas,” or tribal leaders.

But noble women having power does not mean equality of the sexes. Quite the contrary.The Incan Empire had a strict hierarchy for women. The queen was at the top, followed by the king's secondary wives.

Next were noblewomen. Following them was a group of religious women called the Quechua Aclla Cuna, or “Virgins of the Sun.” They were a strictly female religious order that worshiped the moon goddess. These temple convents drew thousands of beautiful and talented young girls from 8-10 years old. They prepared food for rituals, maintained the sacred fire, and wove. The convents were managed by matrons known as “Mama Cuna.” The Coya Pasca was a noblewoman who ruled over them all and was believed to be the earthly consort of the Sun God. The girls served for almost a decade before they were sent off to one of three paths: became victims of sacrifice, concubines, or wives of noblemen.

Outside the convents, women could inherit land and manage their finances. Concubinage and polygamy waere common, but even secondary wives could manage their own finances and households. One secondary wife had 4,000 homes and over 300 servants to manage. But most women were commoners and labored as farmers, weavers, and housewives. Cloth was key to the economy, and thus women’s work was essential. Woven cloths recorded the

historic chronicles of the empire– and thus women were the primary authors of Incan history.

Women held power in Inca society as queen consorts and some wielded power in their own right. The Incan empire traces its roots to a woman, Mama Huaco, the first Quoya or Queen. She ruled the empire outright. Other Quoyas who followed held varying degrees of power as the primary wife of the king with the title “Queen of all women.” Quoyas presided over the kingdom in their husbands’ absence and acted as tiebreaker when the leadership was stalemated. Outside the heart of the empire, women became “Kurakas,” or tribal leaders.

But noble women having power does not mean equality of the sexes. Quite the contrary.The Incan Empire had a strict hierarchy for women. The queen was at the top, followed by the king's secondary wives.

Next were noblewomen. Following them was a group of religious women called the Quechua Aclla Cuna, or “Virgins of the Sun.” They were a strictly female religious order that worshiped the moon goddess. These temple convents drew thousands of beautiful and talented young girls from 8-10 years old. They prepared food for rituals, maintained the sacred fire, and wove. The convents were managed by matrons known as “Mama Cuna.” The Coya Pasca was a noblewoman who ruled over them all and was believed to be the earthly consort of the Sun God. The girls served for almost a decade before they were sent off to one of three paths: became victims of sacrifice, concubines, or wives of noblemen.

Outside the convents, women could inherit land and manage their finances. Concubinage and polygamy waere common, but even secondary wives could manage their own finances and households. One secondary wife had 4,000 homes and over 300 servants to manage. But most women were commoners and labored as farmers, weavers, and housewives. Cloth was key to the economy, and thus women’s work was essential. Woven cloths recorded the

historic chronicles of the empire– and thus women were the primary authors of Incan history.

Statue of the Goddess Cihuateto, wikimedia commons

Statue of the Goddess Cihuateto, wikimedia commons

Aztecs

The Aztec empire was loosely connected and unstable. The empire had massive cities with temples almost 200 feet high. In the domestic sphere, Aztec women cooked, cleaned, spun, wove cloth, and participated in ritualistic activities. Outside the home, they served in palaces, as priestesses in temples, traders, and craftswomen in markets, and teachers in schools.

Religion for the Aztec was bloody, involving the human sacrifice of conquered peoples. The Aztec believed that their patron deity required human blood to keep the world from catastrophe. While there was an emphasis on gender parallelism, men occupied the highest ranks of Aztec religious life. Interestingly, some rituals involved “rebirth” of priests who covered themselves in blood and emerged from a sort of vagina. Women played a secondary role in these public religious rituals.

Despite the patriarchal nature of the growing empire, almost half of the spiritual calendar was dedicated to goddesses, perhaps harkening back to their more egalitarian past. The Aztecs had many goddesses identified with fertility, nourishment, and agriculture, reflections, perhaps because these symbols had held a more elevated status in the past. Interestingly, in Aztec mythology, the Earth Mother’s son killed his sister the Moon Goddess. In his obsession for power the son scattered her children.

Female Aztec deities such as Coyolxauhqui, Coatlicue, and Cihuateteo were tended only by women. Priestesses conducted all rituals, from collecting offerings to developing complex practices. Cihuateteo had an essential role as the goddess of women who died birthing, the equivalent of men dying on battlefields and known as “Women’s War.” Midwives had a crucial role in Mesoamerican societies. Fertility and birthing were highly appreciated and revered . The process demanded complex religious rituals conducted only by priestesses.

The Aztec empire was loosely connected and unstable. The empire had massive cities with temples almost 200 feet high. In the domestic sphere, Aztec women cooked, cleaned, spun, wove cloth, and participated in ritualistic activities. Outside the home, they served in palaces, as priestesses in temples, traders, and craftswomen in markets, and teachers in schools.

Religion for the Aztec was bloody, involving the human sacrifice of conquered peoples. The Aztec believed that their patron deity required human blood to keep the world from catastrophe. While there was an emphasis on gender parallelism, men occupied the highest ranks of Aztec religious life. Interestingly, some rituals involved “rebirth” of priests who covered themselves in blood and emerged from a sort of vagina. Women played a secondary role in these public religious rituals.

Despite the patriarchal nature of the growing empire, almost half of the spiritual calendar was dedicated to goddesses, perhaps harkening back to their more egalitarian past. The Aztecs had many goddesses identified with fertility, nourishment, and agriculture, reflections, perhaps because these symbols had held a more elevated status in the past. Interestingly, in Aztec mythology, the Earth Mother’s son killed his sister the Moon Goddess. In his obsession for power the son scattered her children.

Female Aztec deities such as Coyolxauhqui, Coatlicue, and Cihuateteo were tended only by women. Priestesses conducted all rituals, from collecting offerings to developing complex practices. Cihuateteo had an essential role as the goddess of women who died birthing, the equivalent of men dying on battlefields and known as “Women’s War.” Midwives had a crucial role in Mesoamerican societies. Fertility and birthing were highly appreciated and revered . The process demanded complex religious rituals conducted only by priestesses.

Bantu Migrations, Wikimedia Commons

Bantu Migrations, Wikimedia Commons

Women were routinely sacrificed in Aztec rituals. For example, every December, a woman was dressed as the Earth goddess and decapitated. Her head was presented to a priest. In June, a woman dressed as the Goddess of Corn was sacrificed. In August, a woman chosen to represent the Mother of the Gods was decapitated and her skin was then ripped from her and worn by a priest.

Despite these horrors, women's roles were essential for the empire. Some were emperors' mothers who significantly influenced political and religious spheres. Others were central to consummate alliances. Fixed marriages were the norm for noble women who had no saying in their unions.

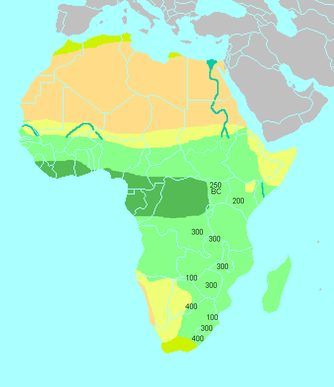

Bantu Migrations

Across the ocean in Africa, long-connected to Eurasian trade, 5,500 years ago West Africans who spoke a variety of languages designated as “Bantu” moved southward in what has been termed the Bantu Migrations. speaking Bantu languages) southward. Among these societies, gender relations varied greatly, but generally there was some equity and shared burdens within relationships.

Africa was underpopulated, so birthing and rearing healthy children was essential to society's success. The effect of the value placed on birth was that women who birthed and cared for children were given a great deal of respect. Families centered around grandmothers, who provided the counsel and support to help the family succeed.

The Bantu were matrilineal, passing wealth through the mother’s line. Society was organized as a heterarchy with leaders having shorter reach and councils governing. In other words, a heterarchy distributes privilege and decision-making across a variety of roles, while a hierarchy assigns more power and privilege to people with "higher" privilege and status in the structure. Some societies were ruled by queens. In some cases they were so powerful they had the authority to condemn the King to death, even when the king managed the government. Africa’s earliest empires, such as Ghana, Mali, and Songha commonly functioned matrilineally. In the Congo and Cameroons, women managed the market places. In Nigeria, a women’s council advised the Queen.

Women in early modern Africa played a significant role in the political sphere. In the Kingdom of Dahomey, for example, women were trained as soldiers and served in the royal army. They also held positions of power, serving as advisors to the king. In the Kingdom of Buganda, in east Africa, women were involved in the selection of the king and played a key role in the political process.

A notable woman leader and queen of this era is Njinga Ana da Sousa Mbande (1583-1663) who lived and ruled in what is now northern Angola in West Central Africa. She was ruler of the Ambundu Kingdoms of Ndongo (1624–1663) and Matamba (1631–1663), and became the Queen of Ndongo. She battled the Portuguese, who attempted to establish the slave trade in what is now Angpola in East Africa in the seventeenth century. Coming to power after the suicide of her brother who feared the Portuguese, she negotiated a peace treaty with the Portuguese who wanted to expand their transatlantic slave trade in what is now Angola in West Africa. Nzinga resisted their attempts to enslave her society and instead made them sign a peace treaty that gave her command over the interior trade. She did this by fighting neighboring societies and sending captives to the Portuguese as slaves. It was mandated that she fight neighboring tribes in order to capture slaves for Portugal. In return the Portugue agreed not to enslave Nzinga’s people, theMbundu Mbundsu. However, over time, Portugal did not keep its word, and Nzinga fought her European adversary for many years, often leading troop[s into battle herself. Despite being engaged in the slave trade, she is remembered as an iconic and heroic leaders who She protected her people, fought off the Portuguese, and eluded capture. She is remembered as a heroic leader.

Women in early modern Africa were active participants in trade. They engaged in both local and long-distance trade, and some women even held monopolies in certain markets. Women were also involved in the production of goods, such as textiles and pottery, which they sold in local markets. In the Swahili city-states of East Africa, women were involved in the Indian Ocean trade, owning their own ships and participating in long-distance trade.

Women in early modern Africa played a significant role in the spread of religion. Women in many societies were the primary religious practitioners who played an important role in the transmission of religious knowledge. For example, in the Kingdom of Kongo, women served as priests and had the authority to perform religious rituals. In the Islamic kingdoms of West Africa, women were involved in the dissemination of Islamic knowledge and played an important role in the spread of Islam.

The existence of queens does not mean society was egalitarian. In some cases, African queens kept male concubines and killed them after sexual relations. The last Queen of the Ashanti, Nana Yaa Asantewaa, (1`840-1921) who ruled on the Gold Coast of Africa in modern day Ghana, was known to eliminate her entire male harem every once and a while.

Empire creation and diffusion of Islam and Christianity into Africa led to more hierarchies and less heterarchy, placing influence on male supremacy. Elite women kept their status, while poorer women lost respect within their clans.

Conclusion

Gender dynamics in these places were complex and varied. At the point of contact, as Europeans moved through trade of various sorts including slave trades, ultimately founding colonial settlements in the Americas, Oceania, Africa gender dynamics became disrupted and new gendered cultures emerged.

By the end of this era, so much remained in question. What parts of indigenous culture would survive contact? How would women navigate the sometimes less egalitarian gender expectations of European cultures?

Despite these horrors, women's roles were essential for the empire. Some were emperors' mothers who significantly influenced political and religious spheres. Others were central to consummate alliances. Fixed marriages were the norm for noble women who had no saying in their unions.

Bantu Migrations

Across the ocean in Africa, long-connected to Eurasian trade, 5,500 years ago West Africans who spoke a variety of languages designated as “Bantu” moved southward in what has been termed the Bantu Migrations. speaking Bantu languages) southward. Among these societies, gender relations varied greatly, but generally there was some equity and shared burdens within relationships.

Africa was underpopulated, so birthing and rearing healthy children was essential to society's success. The effect of the value placed on birth was that women who birthed and cared for children were given a great deal of respect. Families centered around grandmothers, who provided the counsel and support to help the family succeed.

The Bantu were matrilineal, passing wealth through the mother’s line. Society was organized as a heterarchy with leaders having shorter reach and councils governing. In other words, a heterarchy distributes privilege and decision-making across a variety of roles, while a hierarchy assigns more power and privilege to people with "higher" privilege and status in the structure. Some societies were ruled by queens. In some cases they were so powerful they had the authority to condemn the King to death, even when the king managed the government. Africa’s earliest empires, such as Ghana, Mali, and Songha commonly functioned matrilineally. In the Congo and Cameroons, women managed the market places. In Nigeria, a women’s council advised the Queen.

Women in early modern Africa played a significant role in the political sphere. In the Kingdom of Dahomey, for example, women were trained as soldiers and served in the royal army. They also held positions of power, serving as advisors to the king. In the Kingdom of Buganda, in east Africa, women were involved in the selection of the king and played a key role in the political process.

A notable woman leader and queen of this era is Njinga Ana da Sousa Mbande (1583-1663) who lived and ruled in what is now northern Angola in West Central Africa. She was ruler of the Ambundu Kingdoms of Ndongo (1624–1663) and Matamba (1631–1663), and became the Queen of Ndongo. She battled the Portuguese, who attempted to establish the slave trade in what is now Angpola in East Africa in the seventeenth century. Coming to power after the suicide of her brother who feared the Portuguese, she negotiated a peace treaty with the Portuguese who wanted to expand their transatlantic slave trade in what is now Angola in West Africa. Nzinga resisted their attempts to enslave her society and instead made them sign a peace treaty that gave her command over the interior trade. She did this by fighting neighboring societies and sending captives to the Portuguese as slaves. It was mandated that she fight neighboring tribes in order to capture slaves for Portugal. In return the Portugue agreed not to enslave Nzinga’s people, theMbundu Mbundsu. However, over time, Portugal did not keep its word, and Nzinga fought her European adversary for many years, often leading troop[s into battle herself. Despite being engaged in the slave trade, she is remembered as an iconic and heroic leaders who She protected her people, fought off the Portuguese, and eluded capture. She is remembered as a heroic leader.

Women in early modern Africa were active participants in trade. They engaged in both local and long-distance trade, and some women even held monopolies in certain markets. Women were also involved in the production of goods, such as textiles and pottery, which they sold in local markets. In the Swahili city-states of East Africa, women were involved in the Indian Ocean trade, owning their own ships and participating in long-distance trade.

Women in early modern Africa played a significant role in the spread of religion. Women in many societies were the primary religious practitioners who played an important role in the transmission of religious knowledge. For example, in the Kingdom of Kongo, women served as priests and had the authority to perform religious rituals. In the Islamic kingdoms of West Africa, women were involved in the dissemination of Islamic knowledge and played an important role in the spread of Islam.

The existence of queens does not mean society was egalitarian. In some cases, African queens kept male concubines and killed them after sexual relations. The last Queen of the Ashanti, Nana Yaa Asantewaa, (1`840-1921) who ruled on the Gold Coast of Africa in modern day Ghana, was known to eliminate her entire male harem every once and a while.

Empire creation and diffusion of Islam and Christianity into Africa led to more hierarchies and less heterarchy, placing influence on male supremacy. Elite women kept their status, while poorer women lost respect within their clans.

Conclusion

Gender dynamics in these places were complex and varied. At the point of contact, as Europeans moved through trade of various sorts including slave trades, ultimately founding colonial settlements in the Americas, Oceania, Africa gender dynamics became disrupted and new gendered cultures emerged.

By the end of this era, so much remained in question. What parts of indigenous culture would survive contact? How would women navigate the sometimes less egalitarian gender expectations of European cultures?

Draw your own conclusions

|

Learn how to teach with inquiry.

Many of these lesson plans were sponsored in part by the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources Eastern Region Program, coordinated by Waynesburg University, the History and Social Studies Education Faculty at Plymouth State University, and the Patrons of the Remedial Herstory Project. |

|

OTHER:

In this inquiry from Women in World History, students explore the life of Queen Amina in the 16th century and life in the African Songhay and Hausa Kingdoms. Check it out! In another inquiry, students examine life in pre-contact Guatemala. Check it out here! |

Lesson Plans from Other Organizations

- This website, Women in World History has primary source based lesson plans on women's history in a whole range of topics. Some are free while others have a cost.

- The Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media has produced recommendations for teaching women's history with primary sources and provided a collection of sources for world history. Check them out!

- The Stanford History Education Group has a number of lesson plans about women in World History.

Argula Von Grumbach: Letter of Protest to the University of Ingolstadt

Letter written by female Reformer Argula von Grumbach protesting against the arrest of Arsacius Seehofer for teaching Lutheran ideas. the faculty of Ingolstadt ignored von Grumbach's letter, and Seehofer remained imprisoned. She then had the letter published and, as Protestant works were popular reading at this time (because they challenged traditional authority), it became a bestseller. Perhaps, if they had not dismissed her as just a woman who had no business telling them what to do, the faculty would not have had to face the public embarrassment of a woman, who had never attended university, showing she knew scripture as well as they.

How in God's name can you and your university expect to prevail, when you deploy such foolish violence against the word of God; when you force someone to hold the holy Gospel in their hands for the very purpose of denying it, as you did in the case of Arsacius Seehofer? When you confront him with an oath and declaration such as this, and use imprisonment and even the threat of the stake to force him to deny Christ and his word?

Yes, when I reflect on this, my heart and all my limbs tremble. What do Luther or Melanchthon teach you but the word of God? You condemn them without having refuted them. Did Christ teach you so, or his apostles, prophets, or evangelists? Show me where this is written! You lofty experts, nowhere in the Bible do I find that Christ, or his apostles, or his prophets put people in prison, burnt or murdered them, or sent them into exile...Don't you know what the Lords says in Matthew 10? "Have no fear of him who can take your body but then his power is at an end. But fear him who has power to dispatch soul and body into the depths of hell."

... Have no doubt about this: God looks mercifully on Arsacius, or will do so in the future, just as he did on Peter, who denied the Lord three times. For each day the just person falls seven times and gets up on his feet again. God does not want the death of the sinner, but his conversion and life. Christ the Lord himself feared death; so much so that he sweated a bloody sweat. I trust that God will yet see much good from this young man. Just as Peter, too, did much good work later, after his denial of the Lord. And, unlike this man, he was still free, and did not suffer such lengthy imprisonment, or the threat of the stake...

Are you not ashamed that Seehofer had to deny all the writings of Martin, who put the New Testament into German, simply following the text? That means that the holy Gospel and the Epistles and the story of the Apostles and so on are all dismissed by you as heresy. It seems there is no hope of a proper discussion with you. And then there's the five books of Moses, which are being printed too. Is that nothing? I hear nothing about any of you refuting a single article of Arsacius from Scripture...

I beseech you for the sake of God, and exhort you by God's judgement and righteousness, to tell me in writing which of the articles written by Martin or Melanchthon you consider heretical. In German, not a single one seems heretical to me. And the fact is that a great deal has been published in German, and I've read it all. Spalatin sent me a list of all the titles. I have always wanted to find out the truth...My dear lord and father insisted on me reading [the Bible] when I was ten years old. Unfortunately, I did not obey him, being seduced by the afore-named clerics, especially the Observants who said that I would be led astray.

... I do not flinch from appearing before you, from listening to you, from discussing with you. For by the grace of God I, too, can ask questions, hear answers, and read in German. There are, of course, German Bibles which Martin has not translated. You yourselves have on which was printed forty-one years ago, when Luther’s was never even thought of.

If God had not ordained it, I might behave like the others, and write or say that he perverts Scripture; that is contrary to God's will. Although I have yet to read anyone who is his equal in translating it into German. May God, who works all this in him, be his reward here in time and in eternity. And even if it came to pass – which God forfend – that Luther were to revoke his views, that would not worry me. I do not build on his, mine, or any person's understanding, but on the true rock, Christ himself, which the builders have rejected. But he has been made the foundation stone and the head of the corner, as Paul says in I Corinthians 3: "No other base can be laid, than that which is laid, which is Christ..."

I have no Latin; but you have German, being born and brought up in this tongue. What I have written you is no woman's chit-chat, but the word of God; and I wrote as a member of the Christian Church, against which the gates of Hell cannot prevail. Against the Roman, however, they do prevail. Just look at that church! How is it to prevail against the gates of Hell? God give us his grace, that we all may be saved, and may God rule us according to His will. Now may his grace carry the day. Amen.

Dietfurt. Sunday after the exaltation of the holy Cross. The year of the Lord One thousand five hundred and in the twenty-third year.

My signature, Argula von Grumbach, von Stauff by birth.

To the reverent, honorable, well-born, most learned, noble and esteemed Rector and general council of the whole University of Ingolstadt.

Jordon, S.E. Additional Primary Readings for A Reformation Reader. Fortress Press, 2002. Retrieved from https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1971/argula-von-grumbachs-to-the-university-of-ingolsta/.

Questions:

How in God's name can you and your university expect to prevail, when you deploy such foolish violence against the word of God; when you force someone to hold the holy Gospel in their hands for the very purpose of denying it, as you did in the case of Arsacius Seehofer? When you confront him with an oath and declaration such as this, and use imprisonment and even the threat of the stake to force him to deny Christ and his word?

Yes, when I reflect on this, my heart and all my limbs tremble. What do Luther or Melanchthon teach you but the word of God? You condemn them without having refuted them. Did Christ teach you so, or his apostles, prophets, or evangelists? Show me where this is written! You lofty experts, nowhere in the Bible do I find that Christ, or his apostles, or his prophets put people in prison, burnt or murdered them, or sent them into exile...Don't you know what the Lords says in Matthew 10? "Have no fear of him who can take your body but then his power is at an end. But fear him who has power to dispatch soul and body into the depths of hell."

... Have no doubt about this: God looks mercifully on Arsacius, or will do so in the future, just as he did on Peter, who denied the Lord three times. For each day the just person falls seven times and gets up on his feet again. God does not want the death of the sinner, but his conversion and life. Christ the Lord himself feared death; so much so that he sweated a bloody sweat. I trust that God will yet see much good from this young man. Just as Peter, too, did much good work later, after his denial of the Lord. And, unlike this man, he was still free, and did not suffer such lengthy imprisonment, or the threat of the stake...

Are you not ashamed that Seehofer had to deny all the writings of Martin, who put the New Testament into German, simply following the text? That means that the holy Gospel and the Epistles and the story of the Apostles and so on are all dismissed by you as heresy. It seems there is no hope of a proper discussion with you. And then there's the five books of Moses, which are being printed too. Is that nothing? I hear nothing about any of you refuting a single article of Arsacius from Scripture...

I beseech you for the sake of God, and exhort you by God's judgement and righteousness, to tell me in writing which of the articles written by Martin or Melanchthon you consider heretical. In German, not a single one seems heretical to me. And the fact is that a great deal has been published in German, and I've read it all. Spalatin sent me a list of all the titles. I have always wanted to find out the truth...My dear lord and father insisted on me reading [the Bible] when I was ten years old. Unfortunately, I did not obey him, being seduced by the afore-named clerics, especially the Observants who said that I would be led astray.

... I do not flinch from appearing before you, from listening to you, from discussing with you. For by the grace of God I, too, can ask questions, hear answers, and read in German. There are, of course, German Bibles which Martin has not translated. You yourselves have on which was printed forty-one years ago, when Luther’s was never even thought of.

If God had not ordained it, I might behave like the others, and write or say that he perverts Scripture; that is contrary to God's will. Although I have yet to read anyone who is his equal in translating it into German. May God, who works all this in him, be his reward here in time and in eternity. And even if it came to pass – which God forfend – that Luther were to revoke his views, that would not worry me. I do not build on his, mine, or any person's understanding, but on the true rock, Christ himself, which the builders have rejected. But he has been made the foundation stone and the head of the corner, as Paul says in I Corinthians 3: "No other base can be laid, than that which is laid, which is Christ..."

I have no Latin; but you have German, being born and brought up in this tongue. What I have written you is no woman's chit-chat, but the word of God; and I wrote as a member of the Christian Church, against which the gates of Hell cannot prevail. Against the Roman, however, they do prevail. Just look at that church! How is it to prevail against the gates of Hell? God give us his grace, that we all may be saved, and may God rule us according to His will. Now may his grace carry the day. Amen.

Dietfurt. Sunday after the exaltation of the holy Cross. The year of the Lord One thousand five hundred and in the twenty-third year.

My signature, Argula von Grumbach, von Stauff by birth.

To the reverent, honorable, well-born, most learned, noble and esteemed Rector and general council of the whole University of Ingolstadt.

Jordon, S.E. Additional Primary Readings for A Reformation Reader. Fortress Press, 2002. Retrieved from https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1971/argula-von-grumbachs-to-the-university-of-ingolsta/.

Questions:

- How does she compare Lutheran beliefs and actions to those of the Catholics?

- How does she defend Martin Luther?

- What does she say about women?

- Why does she end with a long list of descriptions of the faculty member’s status?

- What does this say about her fear of Catholics?

Katharina Schütz Zell: Defending Clerical Marriage

Katharina Schütz Zell was a female Reformer whose letters were infamous for deeming the Catholic clergy as hypocrites. Her letters were printed and distributed around Strasbourg.

They [the Catholic clergy] also reject the marriage of priests, although it is taught in Holy Scripture, in both the Old and New Testaments, in clear, plain language, so that even children and fools could read and understand it, as I have shown.

Why, speaking of marriage, do they stand so firmly against it, as though they intended to spite God and suppress it by force? There are two reasons. The first is that the members of the clergy would not get so much whoring tax from married couples as from whores and rascals. If a priest has a wife, he behaves like any burgher, and he pays the bishop no tax for it, since God has allowed him to be free. If they have whores, however, they become bondsmen to the popes and bishops. Whoever wants one, must ask and get the bishop's permission and pay a tax for it. So the latter have devised an annual payment which, poor or rich, the priest must pay, just like one who leases land from another and pays an annual rent for it, that's what they do.

God, however, established marriage for all men in the initial act of creation, and no one has been exempted from it and it is also expressly recommended for priests. What God thus desires, they wish to condemn, punish, and forbid for all of those who come under their power. But the whoredom, they do not punish, and have never punished it but rather protected it. Yes, clergymen and laymen have formed an alliance to struggle violently against God. Oh, the blindness of the rulers, how do you look to one another, [you] who should be dedicated to everything honorable?

The second reason is that if the priests have wives, they cannot exchange them among themselves, as they do with the whores. If the priests could honorably marry, they could preach from the pulpit more effectively against adultery. Otherwise, how can they condemn that in which they themselves are stuck. If, however, a priest had a wife, and if he did something bad, people would know how to punish him.

“Defending Clerical Marriage.” GHDI. Accessed November 16, 2022. https://ghdi.ghi- dc.org/sub_document.cfm?document_id=4332.

Questions:

They [the Catholic clergy] also reject the marriage of priests, although it is taught in Holy Scripture, in both the Old and New Testaments, in clear, plain language, so that even children and fools could read and understand it, as I have shown.

Why, speaking of marriage, do they stand so firmly against it, as though they intended to spite God and suppress it by force? There are two reasons. The first is that the members of the clergy would not get so much whoring tax from married couples as from whores and rascals. If a priest has a wife, he behaves like any burgher, and he pays the bishop no tax for it, since God has allowed him to be free. If they have whores, however, they become bondsmen to the popes and bishops. Whoever wants one, must ask and get the bishop's permission and pay a tax for it. So the latter have devised an annual payment which, poor or rich, the priest must pay, just like one who leases land from another and pays an annual rent for it, that's what they do.

God, however, established marriage for all men in the initial act of creation, and no one has been exempted from it and it is also expressly recommended for priests. What God thus desires, they wish to condemn, punish, and forbid for all of those who come under their power. But the whoredom, they do not punish, and have never punished it but rather protected it. Yes, clergymen and laymen have formed an alliance to struggle violently against God. Oh, the blindness of the rulers, how do you look to one another, [you] who should be dedicated to everything honorable?

The second reason is that if the priests have wives, they cannot exchange them among themselves, as they do with the whores. If the priests could honorably marry, they could preach from the pulpit more effectively against adultery. Otherwise, how can they condemn that in which they themselves are stuck. If, however, a priest had a wife, and if he did something bad, people would know how to punish him.

“Defending Clerical Marriage.” GHDI. Accessed November 16, 2022. https://ghdi.ghi- dc.org/sub_document.cfm?document_id=4332.

Questions:

- How does the clergy view marriage according to Zell?

- Does the idea of a tax seem hypocritical? Why?

- What is Zell’s main argument?

Marie Dentière: A Very Useful Epistle by a Christian Woman of Tournai

Written by Marie Dentière, a Genevan Reformer, this letter addressed to Marguerite de Navarre called for women to be included in the church.

For what God has given you and revealed to us women, no more than men should we hide it and bury it in the earth. And even though we are not permitted to preach in public in congregations and churches, we are not forbidden to write and admonish one another in all charity. Not only for you, my Lady, did I wish to write this letter, but also to give courage to other women detained in captivity, so that they might not fear being expelled from their homelands, away from their relatives and friends, as I was, for the word of God. And principally for the poor little women wanting to know and understand the truth, who do not know what path, what way to take, in order that from now on they be not internally tormented and afflicted, but rather that they be joyful, consoled, and led to follow the truth, which is the Gospel of Jesus Christ...For until now scripture has been so hidden from them. No one dared to say a word about it, and it seemed that women should not read or hear anything in the holy scriptures. That is the main reason, my Lady, that has moved me to write to you, hoping in God that henceforth women will not be scorned as in the past.

Epistle to Marguerite de Navarre & Preface to a Sermon by John Calvin, ed. & trans. Mary McKinley. University of Chicago Press, 2004, 6.

Questions:

For what God has given you and revealed to us women, no more than men should we hide it and bury it in the earth. And even though we are not permitted to preach in public in congregations and churches, we are not forbidden to write and admonish one another in all charity. Not only for you, my Lady, did I wish to write this letter, but also to give courage to other women detained in captivity, so that they might not fear being expelled from their homelands, away from their relatives and friends, as I was, for the word of God. And principally for the poor little women wanting to know and understand the truth, who do not know what path, what way to take, in order that from now on they be not internally tormented and afflicted, but rather that they be joyful, consoled, and led to follow the truth, which is the Gospel of Jesus Christ...For until now scripture has been so hidden from them. No one dared to say a word about it, and it seemed that women should not read or hear anything in the holy scriptures. That is the main reason, my Lady, that has moved me to write to you, hoping in God that henceforth women will not be scorned as in the past.

Epistle to Marguerite de Navarre & Preface to a Sermon by John Calvin, ed. & trans. Mary McKinley. University of Chicago Press, 2004, 6.

Questions:

- What is the tone of this letter?

- What does she hope for women?

- Does she blame women? Does she blame men?

Marie Dentière: A Letter Addressing Women

“Therefore, if God has given grace to some good women, revealing to them by His Holy Scriptures something holy and good, should they hesitate to write, speak, and declare it to one another because of the defamers of truth? Ah, it would be too bold to try to stop them, and it would be too foolish for us to hide the talent that God has given us, God who will give us the grace to persevere to the end. Some might be upset because this is said by a woman, believing that this is not appropriate for her, since women are made for pleasure. But I pray you to not be offended; you must not think that I do this from hatred or from rancor. I do this only to edify my neighbor, seeing him in such great, horrible darkness... No man could be able to expose it enough. How, therefore, will a woman do it?”

Lafbwad. “Marie Dentiere-the Woman on the Reformation Wall.” Beautiful Womanhood, October 30, 2017. https://ladiesagainstfeminism.com/2017/10/29/marie-dentiere-the-woman-on-the- reformation-wall/.

Questions:

Lafbwad. “Marie Dentiere-the Woman on the Reformation Wall.” Beautiful Womanhood, October 30, 2017. https://ladiesagainstfeminism.com/2017/10/29/marie-dentiere-the-woman-on-the- reformation-wall/.

Questions:

- Briefly summarize her letter to get a better understanding of what she wrote.

- Is she angry at men or seemingly sympathetic?

- How does Marie view God?

Anne Askew: Poem

Anne Askew was a Reformer jailed and tortured for her Luthean beliefs and teachings. She wrote this poem while in jail. She would be executed in 1546.

Like as the armed knight Appointed to the field,

With this world will I fight And Faith shall be my shield.

Faith is that weapon strong Which will not fail at need. My foes, therefore, among Therewith will I proceed.

As it is had in strength

And force of Christes way

It will prevail at length Though all the devils say nay

I now rejoice in heart

And Hope bid me do so For Christ will take my part And ease me of my woe.

More enemies now I have Then hairs upon my head. Let them not me deprave But fight thou in my stead.

On thee my care I cast. For all their cruel spight I set not by their haste For thou art my delight.

I saw a rial throne

Where Justice should have sit But in her stead was one

Of moody cruel wit.

Absorpt was righteousness As of the raging flood

Sathan in his excess

Suct up the guiltless blood.

Then thought I, Jesus lord, When thou shalt judge us all Hard is it to record

On these men what will fall. Yet lord, I thee desire

For that they do to me

Let them not taste the hire Of their iniquity.

Crowther, David. The history of england, May 27, 2020. https://thehistoryofengland.co.uk/resource/anne-askew-martyr-and-author/.

Questions:

Like as the armed knight Appointed to the field,

With this world will I fight And Faith shall be my shield.

Faith is that weapon strong Which will not fail at need. My foes, therefore, among Therewith will I proceed.

As it is had in strength

And force of Christes way

It will prevail at length Though all the devils say nay

I now rejoice in heart

And Hope bid me do so For Christ will take my part And ease me of my woe.

More enemies now I have Then hairs upon my head. Let them not me deprave But fight thou in my stead.

On thee my care I cast. For all their cruel spight I set not by their haste For thou art my delight.

I saw a rial throne

Where Justice should have sit But in her stead was one

Of moody cruel wit.

Absorpt was righteousness As of the raging flood

Sathan in his excess

Suct up the guiltless blood.

Then thought I, Jesus lord, When thou shalt judge us all Hard is it to record

On these men what will fall. Yet lord, I thee desire

For that they do to me

Let them not taste the hire Of their iniquity.

Crowther, David. The history of england, May 27, 2020. https://thehistoryofengland.co.uk/resource/anne-askew-martyr-and-author/.

Questions:

- What is the overall message and tone of her poem?

- Is she hopeful for her cause?

- Were women integral to the Protestant Reformation?

Remedial Herstory Editors. "17. 1000-1600 GENDER DYNAMICS IN NEW WORLDS" The Remedial Herstory Project. November 1, 2022. www.remedialherstory.com.

AUTHOR: |

Kelsie Brook Eckert and Jacqui Nelson

|

Consulting Team |

Editors |

|

Kelsie Brook Eckert, Project Director

Coordinator of Social Studies Education at Plymouth State University Dr. Nancy Locklin-Sofer, Consultant Professor of History at Maryville College. Chloe Gardner, Consultant PhD Candidate in Religious Studies at Edinburgh University Dr. Whitney Howarth, Consultant Former Professor of History at Plymouth State University Jacqui Nelson, Consultant Teaching Lecturer of Military History at Plymouth State University Maria Concepcion Marquez Sandoval PhD Candidate in History at Arizona University |

Amy Flanders

Humanities Teacher, Moultonborough Academy ReviewersAncient:

Dr. Kristin Heineman Professor of History at Colorado State University Dr. Bonnie Rock-McCutcheon Professor of History at Wilson College Sarah Stone PhD Candidate in Religious Studies at Edinburgh University Medieval: Dr. Katherine Koh Professor of History at La Sierra University Dr. Jonathan Couser Professor of History at Plymouth State University Dr. Shahla Haeri Professor of History at Boston University Lauren Cole PhD Candidate in History at Northwestern University Modern: Dr. Jack Gronau Professor of History at Northeastern University Dr. Barbara Tischler Supervisor for Hunter College Dr. Pamela Scully Professor of Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies and African Studies at Emory University |

|

Aztec Women and Goddesses explores the various stages of the Mexica woman’s life. Miriam López analyzes the mythology, the archaeological discoveries, and the codices and sixteenth-century chronicles with perfect ease as she describes the conduct expected of women and the possibilities for their lives according to Mexica norms and ideals. This insightful work rescues the contributions of Mexica women from oblivion—contributions which, though they may not have been deemed worthy of recognition and prestige in their own day, played an essential part in shaping and consolidating the social structures of the Mexica Empire.

The few works looking at the knowledge of women in Mesoamerica generally examine only the written—even academic—world, accessible only to the most elite segments of (customarily male) society. These works have consistently excluded the essential repertoire and performed knowledge of women who think and work in ways other than the textual. And while two of the book’s chapters critique contemporary novels, Martinez-Cruz also calls for the exploration of non-textual knowledge transmission. In this regard, the book's goals and methods are close to those of performance scholarship and anthropology, and these methods reveal Mesoamerican women to be public intellectuals. In Women and Knowledge in Mesoamerica, fieldwork and ethnography combine to reveal women healers as models of agency.

Acts of remembering offer a path to decolonization for Indigenous peoples forcibly dislocated from their culture, knowledge, and land. Susy J. Zepeda highlights the often overlooked yet intertwined legacies of Chicana feminisms and queer decolonial theory through the work of select queer Indígena cultural producers and thinkers. By tracing the ancestries and silences of gender-nonconforming people of color, she addresses colonial forms of epistemic violence and methods of transformation, in particular spirit research.

|

|

|

When black women were brought from Africa to the New World as slave laborers, their value was determined by their ability to work as well as their potential to bear children, who by law would become the enslaved property of the mother's master. In Laboring Women: Reproduction and Gender in New World Slavery, Jennifer L. Morgan examines for the first time how African women's labor in both senses became intertwined in the English colonies. Beginning with the ideological foundations of racial slavery in early modern Europe, Laboring Women traverses the Atlantic, exploring the social and cultural lives of women in West Africa, slaveowners' expectations for reproductive labor, and women's lives as workers and mothers under colonial slavery.

Women, Witchcraft, and the Inquisition in Spain and the New World investigates the mystery and unease surrounding the issue of women called before the Inquisition in Spain and its colonial territories in the Americas, including Mexico and Cartagena de Indias. Edited by María Jesús Zamora Calvo, this collection gathers innovative scholarship that considers how the Holy Office of the Inquisition functioned as a closed, secret world defined by patriarchal hierarchy and grounded in misogynistic standards.

Women in Early America: Struggle, Survival, and Freedom in a New World provides insight into an era in American history when women had immense responsibilities and unusual freedoms. These women worked in a range of occupations such as tavernkeeping, printing, spiritual leadership, trading, and shopkeeping. Pipe smoking, beer drinking, and premarital sex were widespread. One of every eight people traveling with the British Army during the American Revolution was a woman.

Through powerful stories that place the reader on the ground in plantation-era Jamaica, Contested Bodies reveals enslaved women's contrasting ideas about maternity and raising children, which put them at odds not only with their owners but sometimes with abolitionists and enslaved men. Turner argues that, as the source of new labor, these women created rituals, customs, and relationships around pregnancy, childbirth, and childrearing that enabled them at times to dictate the nature and pace of their work as well as their value.

|

|

|

A political marriage is arranged between the thirty-three-year-old king of Xukpip and Princess Green Jay, the thirteen-year-old daughter of the king of Lakamha. The two are paired because of similar horoscopes -- and Green Jay possesses skills that will be valuable to her husband-to-be: She can read and write. Author Anna Kirwan relates fascinating aspects of ancient Mayan culture as she shares the young princess's physical and emotional state from the betrothal, with its distressing rituals, through her arduous journey to a foreign land and people, and a husband who is a complete stranger.

|

A terrible crime occurs. Qing, who has already shown an aptitude for solving mysteries, is ordered by his captain to work with the village shaman, an elderly, rather cynical, woman named Xmucane to discover who perpetrated the crime. They are successful, but in the process, uncover a conspiracy against the Tarascan empire. They are ordered to the capital, to pursue justice and solve mysteries large and small in the service of the Tarascan court. The two detectives and their comrades discover truths, not only about the conspiracy but about themselves.

|

Born in the Wayeb, Book One of The Mayan Chronicles, introduced Na'om, a young Mayan woman with the ability to foresee the future through her dreams, and her archenemy, Satal, the black witch of Mayapán, who wants to absorb Na'om's magical powers. Rise of the Jaguar Woman, Book Two of The Mayan Chronicles, plunges Na'om and her black jaguar companion, Ek' Balam, into the Underworld where they face numerous dangers and deprivations concocted by the gods. The pair must use their magical abilities to overcome their fears and return to the land of the living where Satal plots her revenge, amassing an army like no other to use against everyone Na'om knows and loves.

|

|

Sixteen-year-old Kit Tyler is marked by suspicion and disapproval from the moment she arrives on the unfamiliar shores of colonial Connecticut in 1687. Alone and desperate, she has been forced to leave her beloved home on the island of Barbados and join a family she has never met. Torn between her quest for belonging and her desire to be true to herself, Kit struggles to survive in a hostile place. Just when it seems she must give up, she finds a kindred spirit. But Kit’s friendship with Hannah Tupper, believed by the colonists to be a witch, proves more taboo than she could have imagined and ultimately forces Kit to choose between her heart and her duty.

Stuart Stirling tells the history of the Inca princesses and of their conquistador lovers and descendants. The story begins with the early days of Pizarro's conquest at Cajamarca in the 1530s, when the emperor Atahualpa gifted his young sister wife Quispe Sis Huaylas to Pizarro. This was the beginning of the distribution and rape of the princesses among the conquistadors - a practice which was in many ways a distillation of the tragedy of the Spanish colonization of the Americas. The detailed human stories of the princesses bring to life the world of the Incas and their conquerors and shed new light on the darker corners of colonial history.

|

|

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Akyeampong, Emmanuel, and Henry Louis Gates Jr. "Africa in the Colonial Ages." In The Dictionary of African Biography, edited by Emmanuel Akyeampong and Henry Louis Gates Jr., 1:14-16. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Alwan, Christine, "Dependence on or the Subordination of Women? Examining the Political, Domestic, and Religious Roles of Women in Mesoamerican, Andean, and Spanish Societies in the 15th Century" (2013). Joyce Durham Essay Contest in Women's and Gender Studies. 18.

https://ecommons.udayton.edu/wgs_essay/18.

Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. "Chosen Women." Encyclopedia Britannica, February 15, 2016. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Chosen-Women.

Cooper, Frederick. "Women, Citizenship, and the Making of the African Subject." In Women in African Colonial Histories, edited by Jean Allman, Susan Geiger, and Nakanyike Musisi, 27-50. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2002.

"Gender and Religion: Gender and Oceanic Religions ." Encyclopedia of Religion. . Encyclopedia.com. (June 22, 2022). https://www.encyclopedia.com/environment/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/gender-and-religion-gender-and-oceanic-religions.

Groeneveld, Emma. "Women in the Viking Age." World History Encyclopedia. Last modified July 11, 2018. https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1251/women-in-the-viking-age/.

Heywood, Linda M., Njinga of Angola: Africa's Warrior Queen. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2018.

Hunt, Sarah A., "Women of the Incan Empire: Before and After the Conquest of Peru" (2016). Student Research. 5.

https://knowledge.e.southern.edu/hist_studentresearch/5.

Martins, Kim. "Polynesian Navigation & Settlement of the Pacific." World History Encyclopedia. Last modified August 07, 2020. https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1586/polynesian-navigation--settlement-of-the-pacific/.

Mba, Nwando A. "African Women's History." In Africa and the Americas: Culture, Politics, and History, edited by Kevin Shillington, 163-166. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2008.

Miles, Rosalind. The Women’s History of the World. London, UK: Harper Collins Publishers, 1988.

Saidi, Christine. "Women in Precolonial Africa." Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History. 27 Oct. 2020; Accessed 29 Jul. 2022. https://oxfordre.com/africanhistory/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.001.0001/acrefore-9780190277734-e-259.

Strayer, R. and Nelson, E., Ways Of The World. 3rd ed. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2016.

Alwan, Christine, "Dependence on or the Subordination of Women? Examining the Political, Domestic, and Religious Roles of Women in Mesoamerican, Andean, and Spanish Societies in the 15th Century" (2013). Joyce Durham Essay Contest in Women's and Gender Studies. 18.

https://ecommons.udayton.edu/wgs_essay/18.

Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. "Chosen Women." Encyclopedia Britannica, February 15, 2016. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Chosen-Women.

Cooper, Frederick. "Women, Citizenship, and the Making of the African Subject." In Women in African Colonial Histories, edited by Jean Allman, Susan Geiger, and Nakanyike Musisi, 27-50. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2002.

"Gender and Religion: Gender and Oceanic Religions ." Encyclopedia of Religion. . Encyclopedia.com. (June 22, 2022). https://www.encyclopedia.com/environment/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/gender-and-religion-gender-and-oceanic-religions.

Groeneveld, Emma. "Women in the Viking Age." World History Encyclopedia. Last modified July 11, 2018. https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1251/women-in-the-viking-age/.

Heywood, Linda M., Njinga of Angola: Africa's Warrior Queen. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2018.

Hunt, Sarah A., "Women of the Incan Empire: Before and After the Conquest of Peru" (2016). Student Research. 5.

https://knowledge.e.southern.edu/hist_studentresearch/5.

Martins, Kim. "Polynesian Navigation & Settlement of the Pacific." World History Encyclopedia. Last modified August 07, 2020. https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1586/polynesian-navigation--settlement-of-the-pacific/.

Mba, Nwando A. "African Women's History." In Africa and the Americas: Culture, Politics, and History, edited by Kevin Shillington, 163-166. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2008.

Miles, Rosalind. The Women’s History of the World. London, UK: Harper Collins Publishers, 1988.

Saidi, Christine. "Women in Precolonial Africa." Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History. 27 Oct. 2020; Accessed 29 Jul. 2022. https://oxfordre.com/africanhistory/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.001.0001/acrefore-9780190277734-e-259.

Strayer, R. and Nelson, E., Ways Of The World. 3rd ed. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2016.