2. Women’s Cultural Encounters

|

Women were on the Mayflower when it landed in North America. They were sent to Jamestown as Tobacco Wives. Even the first European born in the English colonies was a woman: Virginia Dare... named after the Virgin Queen. Women were also leaders in Indigenous communities, like Pocahontas and Weetamoo. Some indigenous women resisted the encroaching Europeans, others allied or married with them. The first enslaved Africans who were brought to the continent included a woman named Angela. Wherever cultural interactions occurred in the Americas so were women.

|

Queen Elizabeth I of England, Wikimedia Commons

Queen Elizabeth I of England, Wikimedia Commons

England’s Queen Elizabeth I needed to secure colonies in the Americas to compete with her Catholic, Spanish rivals. As Spain claimed territory in South and Central America in the 16th century, Elizabeth focused her attention on North America. The English made several failed attempts to create permanent settlements in the 1570s and 80s. Even though these early colonies did not result in permanent settlements, they nevertheless provided the English with valuable maps and information about climate. Finally, in July 1587 150 men, women and children, set off for the English colony called Virginia, named for the Virgin Queen, Elizabeth.

But despite the name, these weren’t virgin, untouched lands. They were inhabited by hundreds of thousands of Indigenous peoples living in diverse communities and established nations up and down the coasts. The encounters between the sometimes matrilineal, more egalitarian, Indigenous peoples and the patriarchal English arrivals were complicated and interesting due to these distinct gendered dynamics.

The English are not the only models of colonization we can explore in North America. The Dutch settled at the same time between the English settlements at Jamestown and Plymouth.

The cultural encounters continued as migrants and merchants from Latin America traveled north. Then, in 1619, the first enslaved Africans were brought to the English colonies. The effects of these merging peoples and cultures defined and shaped early English colonialism in the Americas. Effecting these encounters at every turn were important female figures.

But despite the name, these weren’t virgin, untouched lands. They were inhabited by hundreds of thousands of Indigenous peoples living in diverse communities and established nations up and down the coasts. The encounters between the sometimes matrilineal, more egalitarian, Indigenous peoples and the patriarchal English arrivals were complicated and interesting due to these distinct gendered dynamics.

The English are not the only models of colonization we can explore in North America. The Dutch settled at the same time between the English settlements at Jamestown and Plymouth.

The cultural encounters continued as migrants and merchants from Latin America traveled north. Then, in 1619, the first enslaved Africans were brought to the English colonies. The effects of these merging peoples and cultures defined and shaped early English colonialism in the Americas. Effecting these encounters at every turn were important female figures.

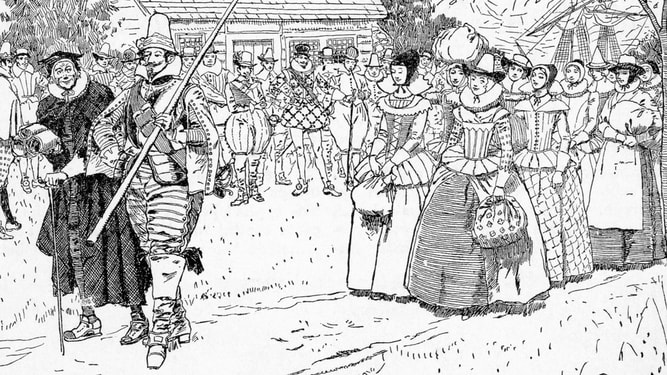

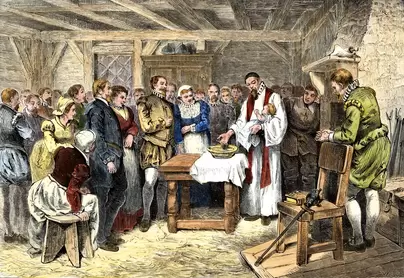

Christening of Virginia Dare, Public Domain

Christening of Virginia Dare, Public Domain

Roanoke:

The first English child born in the Americas was a girl named Virginia Dare, the granddaughter of the man leading the 1587 Roanoke expedition, one of England's first attempts to colonize North America. Her mother, Eleanor, had made the entire sea journey while she was pregnant and encountered the New World under conditions impossible to imagine. The settlers had arrived too late for a sufficient growing season to last the winter, so the leaders returned to England for more supplies. But war broke out between Protestant England and Catholic Spain, delaying the return voyage. After Elizabeth defeated the Spanish Armada in a naval battle of epic proportions, the expedition leaders were able to return with supplies, but they found the settlement abandoned with no trace of its inhabitants. What happened to this “Lost Colony” and little Virginia? Were they killed? Did they starve? Were they absorbed into the local Indigenous tribes? Theories abound, but no one knows for certain.

For some, this lost colony may have signaled a bad omen about further colonization, but for the English, it wasn’t. In 1607, the English settlement in Jamestown, Virginia was established. No women were among this initial group of Jamestown settlers because they were not seen as necessary in what was intended as a military and commercial colony. The failure at Roanoke led the English to seek success and stability before bringing women to settle.

Because no English women joined the journey, this early period of cultural encounters is marked for its tolerance of interracial marriages. English men had long been exposed to evocative ideas about Indigenous women and their sexuality. For the last century, European explorers had returned with tales and sketches of the scantily clad and sensual Indigenous women. Some saw these marriages as a means of establishing peace and permanence in the Americas, while others saw them as morally wrong. We know the marriages were common enough because by 1691, Virginia passed a law banning them. This law also suggests that by the time it passed, there were enough English women in the colony to make it reasonable and feasible.

The first English child born in the Americas was a girl named Virginia Dare, the granddaughter of the man leading the 1587 Roanoke expedition, one of England's first attempts to colonize North America. Her mother, Eleanor, had made the entire sea journey while she was pregnant and encountered the New World under conditions impossible to imagine. The settlers had arrived too late for a sufficient growing season to last the winter, so the leaders returned to England for more supplies. But war broke out between Protestant England and Catholic Spain, delaying the return voyage. After Elizabeth defeated the Spanish Armada in a naval battle of epic proportions, the expedition leaders were able to return with supplies, but they found the settlement abandoned with no trace of its inhabitants. What happened to this “Lost Colony” and little Virginia? Were they killed? Did they starve? Were they absorbed into the local Indigenous tribes? Theories abound, but no one knows for certain.

For some, this lost colony may have signaled a bad omen about further colonization, but for the English, it wasn’t. In 1607, the English settlement in Jamestown, Virginia was established. No women were among this initial group of Jamestown settlers because they were not seen as necessary in what was intended as a military and commercial colony. The failure at Roanoke led the English to seek success and stability before bringing women to settle.

Because no English women joined the journey, this early period of cultural encounters is marked for its tolerance of interracial marriages. English men had long been exposed to evocative ideas about Indigenous women and their sexuality. For the last century, European explorers had returned with tales and sketches of the scantily clad and sensual Indigenous women. Some saw these marriages as a means of establishing peace and permanence in the Americas, while others saw them as morally wrong. We know the marriages were common enough because by 1691, Virginia passed a law banning them. This law also suggests that by the time it passed, there were enough English women in the colony to make it reasonable and feasible.

Pocahontas, Library of Congress

Pocahontas, Library of Congress

Pocahontas:

How did Indigenous women view their encounters with the English? What did they think and feel at the sight of these strange men, with different customs, dress, and beliefs? It's hard to know. So many of their stories can only be interpreted through the lens of English, male settlers and the documents they left behind.

The most famous interracial marriage was that of the native Amonute and the settler John Rolfe. Amonute is, of course, better known by her nickname Pocahontas, or “ill-behaved child.” She was the daughter of Chief Powhatan, the powerful leader of the Powhatan Confederacy, a collection of 30 Algonquian-speaking tribes near Jamestown. So much of her life is known and yet so much of what is popularly known is incorrect.

When John Smith met Powhatan and Pocahontas, he established a degree of peace between the encroaching settlers and the Confederacy. A trading relationship was established and Powhatan would often send Pocahontas with these shipments. She became well known to the English and therefore was a useful negotiator in times of tension. Eventually, relations between the two cultures deteriorated and Powhatan became sick of the ineptitude of the English planters and their constant need to trade for food. He moved his tribe further inland and Pocahontas was not allowed to visit Jamestown anymore.

Eventually Pocahontas was captured in the midst of increasing tensions. She was tricked on board an English ship by the captain's wife. In captivity, Pocahontas learned English and converted to Christianity, taking the Christian name Rebecca. When Powhatan learned of his daughter's capture, he complied with the ransom demands.

After her capture, she met John Rolfe, a widower who had introduced the cash crop tobacco to the colony. The couple married and soon traveled to England where they toured the country. John Smith saw her again and had clearly not forgotten Pocahontas and had even written a letter to Queen Anne describing all she had done to help the English in Jamestown's early years. As they were about to embark on the voyage back to Virginia, Pocahontas fell ill and died.

Pocahontas was a complicated Indigenous figure– one who adopted English customs and arguably abandoned her people, yet she is an important figure as she helped to establish a semblance of peace for a time. Within the year, her father Powhatan died and the "Peace of Pocahontas" disintegrated. Perhaps through these marriages, but certainly through more political and economic relations, the colony survived. One English councilman noted, "When a plantation grows to strength, then it is time to plant with women as well as with men."

How did Indigenous women view their encounters with the English? What did they think and feel at the sight of these strange men, with different customs, dress, and beliefs? It's hard to know. So many of their stories can only be interpreted through the lens of English, male settlers and the documents they left behind.

The most famous interracial marriage was that of the native Amonute and the settler John Rolfe. Amonute is, of course, better known by her nickname Pocahontas, or “ill-behaved child.” She was the daughter of Chief Powhatan, the powerful leader of the Powhatan Confederacy, a collection of 30 Algonquian-speaking tribes near Jamestown. So much of her life is known and yet so much of what is popularly known is incorrect.

When John Smith met Powhatan and Pocahontas, he established a degree of peace between the encroaching settlers and the Confederacy. A trading relationship was established and Powhatan would often send Pocahontas with these shipments. She became well known to the English and therefore was a useful negotiator in times of tension. Eventually, relations between the two cultures deteriorated and Powhatan became sick of the ineptitude of the English planters and their constant need to trade for food. He moved his tribe further inland and Pocahontas was not allowed to visit Jamestown anymore.

Eventually Pocahontas was captured in the midst of increasing tensions. She was tricked on board an English ship by the captain's wife. In captivity, Pocahontas learned English and converted to Christianity, taking the Christian name Rebecca. When Powhatan learned of his daughter's capture, he complied with the ransom demands.

After her capture, she met John Rolfe, a widower who had introduced the cash crop tobacco to the colony. The couple married and soon traveled to England where they toured the country. John Smith saw her again and had clearly not forgotten Pocahontas and had even written a letter to Queen Anne describing all she had done to help the English in Jamestown's early years. As they were about to embark on the voyage back to Virginia, Pocahontas fell ill and died.

Pocahontas was a complicated Indigenous figure– one who adopted English customs and arguably abandoned her people, yet she is an important figure as she helped to establish a semblance of peace for a time. Within the year, her father Powhatan died and the "Peace of Pocahontas" disintegrated. Perhaps through these marriages, but certainly through more political and economic relations, the colony survived. One English councilman noted, "When a plantation grows to strength, then it is time to plant with women as well as with men."

Colonial Home, Public Domain

Colonial Home, Public Domain

English Women in Jamestown:

Native women were not the only women to experience the cultural encounters. The first English women to arrive in Jamestown came in 1608 and were known as “tobacco brides,” women whose transportation across the ocean was paid for by men who made their living growing the cash crop tobacco. The Virginia Company offered substantial incentives to the women including a dowry of clothing, linens, and other furnishings, free transportation to the colony, and even a plot of land. They were also promised their pick of wealthy husbands and provided with food and shelter while they made their decision. These women journeyed across the ocean not knowing a thing about the men that they were about to meet, but the opportunity would have certainly been appealing to poor European women.

Anne Burras came to Virginia as the personal maid of Mistress Forrest in 1608. Mistress Forrest’s fate remains uncertain, but Anne Burras is well known. She married John Laydon three months after she arrived and had the first Jamestown wedding. Anne and John had four daughters who would help to stabilize the colony's growth.

Temperance Flowerdew's encounters in the new world were dark. She arrived in the fall of 1609 only to experience the "Starving Time," which led to an 80 percent death rate of Jamestown’s English population. People ate whatever they could to survive; rats, snakes– and we know of at least one man who ate his wife.Those who survived did so with the aid of local tribes like the Powhatan Confederacy. Temperance survived and married several times. Life expectancy was so low in the colonies that many women became very wealthy through their marriages.

Some English arrivals in the new world were forced. In 1615, the governor's request for more colonists was answered with a shipment of a hundred male felons to the colony. Incentives were increased and private individuals began kidnapping men and women for the colonies. There were dozens of advertisements in English newspapers from parents looking for their lost daughters who were later discovered in the Americas. But the consequences were low. In 1684, a couple was fined only 12 pence for kidnapping and selling a 16-year-old girl– A horse thief would have been hanged. This oddly shows how valuable women were to the English colony’s success.

Not every encounter in the New World was bad. Because women were so few, they were able to be more selective in their choice of male partner. Consequently, men frequently complained about the perceived power imbalance. The English followed laws of coverture. A married woman was “covered” by her husband. Legally and financially she had little rights. But these laws were relaxed to attract women to the colony. Women who inherited land at the deaths of their husbands could keep it in production. Women like Sarah Harrison refused to say “obey” in her marriage vows. Other women would court and be engaged to multiple men at a time– testing out her prospects. Women used their scarcity to their advantage.

Despite the social power and freedoms women experienced in the new world, women were denied the vote and other property rights. Margaret Brent of Maryland became the first woman to demand the right to vote in the colonies. She was a land owner herself and Lord Baltimore had appointed her his estate representative. She was denied on account of her gender. Gender it seems was strictly binary.

But yet that binary was challenged in Virginia when the reality that gender binary was not so black and white became public. Thomasine Hall, was raised as a woman, in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, England. When Thomasine was about 24 years old, her brother joined the English Army, and she decided to accompany him. To join the Army, Thomasine cut her hair, wore men's clothing, and adopted the name Thomas. Upon arriving in the Virginia colony, Thomas started working for John Tyos on a small tobacco plantation as an indentured servant. Initially, Thomas continued dressing and performing tasks as a man, but at some point switched to doing more feminine labor. Although John Tyos accepted this change and affirmed Thomasine's female identity to the community, other members of the community were less comfortable.

Thomas(ine)'s body was inspected by three married women who concluded that they were indeed male. However, John Tyos, Thomas(ine)'s master, disagreed. The situation became more complex when another community member, John Atkins, considered buying Thomas(ine)'s indenture contract from John Tyos. John Atkins felt uncertain about making the purchase without knowing Thomas(ine)'s gender. He needed to determine what kind of work Thomas(ine) could perform and how much to pay for the contract because gender defined these jobs and male indentures were worth more. Thomas(ine) confessed to having a small vaginal opening but no functional male genitalia. Those involved kept changing their view on what clothes they should wear.

Eventually the entire community became aware of Thomas(ine)’s story, and they were harassed on the street and assaulted by two men who lifted their skirts to inspect their body. The men concluded Thomas was definitively male and they were forced to assume male clothing. In 1629, Thomas Hall was tried in court for pretending to be a woman in front of the Quarter Court of Virginia. This public display challenged the conventional gender roles in the colony. After hearing Thomas's account, the governor delivered an extraordinary verdict: Thomas(ine) was declared to be both a man and a woman. As a result, Thomas(ine) was mandated to wear clothing representing both genders: men's breeches and shirt, along with a woman's cap and apron. The new clothing prevented Thomas(ine) from blending in with colonial society ever again. Although this might have been perceived as the community's desired punishment, the court failed to address the questions regarding Thomas(ine)'s future work capabilities. Thomas(ine) disappeared, but this case shows how gender was understood and controlled in the English colonies.

Native women were not the only women to experience the cultural encounters. The first English women to arrive in Jamestown came in 1608 and were known as “tobacco brides,” women whose transportation across the ocean was paid for by men who made their living growing the cash crop tobacco. The Virginia Company offered substantial incentives to the women including a dowry of clothing, linens, and other furnishings, free transportation to the colony, and even a plot of land. They were also promised their pick of wealthy husbands and provided with food and shelter while they made their decision. These women journeyed across the ocean not knowing a thing about the men that they were about to meet, but the opportunity would have certainly been appealing to poor European women.

Anne Burras came to Virginia as the personal maid of Mistress Forrest in 1608. Mistress Forrest’s fate remains uncertain, but Anne Burras is well known. She married John Laydon three months after she arrived and had the first Jamestown wedding. Anne and John had four daughters who would help to stabilize the colony's growth.

Temperance Flowerdew's encounters in the new world were dark. She arrived in the fall of 1609 only to experience the "Starving Time," which led to an 80 percent death rate of Jamestown’s English population. People ate whatever they could to survive; rats, snakes– and we know of at least one man who ate his wife.Those who survived did so with the aid of local tribes like the Powhatan Confederacy. Temperance survived and married several times. Life expectancy was so low in the colonies that many women became very wealthy through their marriages.

Some English arrivals in the new world were forced. In 1615, the governor's request for more colonists was answered with a shipment of a hundred male felons to the colony. Incentives were increased and private individuals began kidnapping men and women for the colonies. There were dozens of advertisements in English newspapers from parents looking for their lost daughters who were later discovered in the Americas. But the consequences were low. In 1684, a couple was fined only 12 pence for kidnapping and selling a 16-year-old girl– A horse thief would have been hanged. This oddly shows how valuable women were to the English colony’s success.

Not every encounter in the New World was bad. Because women were so few, they were able to be more selective in their choice of male partner. Consequently, men frequently complained about the perceived power imbalance. The English followed laws of coverture. A married woman was “covered” by her husband. Legally and financially she had little rights. But these laws were relaxed to attract women to the colony. Women who inherited land at the deaths of their husbands could keep it in production. Women like Sarah Harrison refused to say “obey” in her marriage vows. Other women would court and be engaged to multiple men at a time– testing out her prospects. Women used their scarcity to their advantage.

Despite the social power and freedoms women experienced in the new world, women were denied the vote and other property rights. Margaret Brent of Maryland became the first woman to demand the right to vote in the colonies. She was a land owner herself and Lord Baltimore had appointed her his estate representative. She was denied on account of her gender. Gender it seems was strictly binary.

But yet that binary was challenged in Virginia when the reality that gender binary was not so black and white became public. Thomasine Hall, was raised as a woman, in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, England. When Thomasine was about 24 years old, her brother joined the English Army, and she decided to accompany him. To join the Army, Thomasine cut her hair, wore men's clothing, and adopted the name Thomas. Upon arriving in the Virginia colony, Thomas started working for John Tyos on a small tobacco plantation as an indentured servant. Initially, Thomas continued dressing and performing tasks as a man, but at some point switched to doing more feminine labor. Although John Tyos accepted this change and affirmed Thomasine's female identity to the community, other members of the community were less comfortable.

Thomas(ine)'s body was inspected by three married women who concluded that they were indeed male. However, John Tyos, Thomas(ine)'s master, disagreed. The situation became more complex when another community member, John Atkins, considered buying Thomas(ine)'s indenture contract from John Tyos. John Atkins felt uncertain about making the purchase without knowing Thomas(ine)'s gender. He needed to determine what kind of work Thomas(ine) could perform and how much to pay for the contract because gender defined these jobs and male indentures were worth more. Thomas(ine) confessed to having a small vaginal opening but no functional male genitalia. Those involved kept changing their view on what clothes they should wear.

Eventually the entire community became aware of Thomas(ine)’s story, and they were harassed on the street and assaulted by two men who lifted their skirts to inspect their body. The men concluded Thomas was definitively male and they were forced to assume male clothing. In 1629, Thomas Hall was tried in court for pretending to be a woman in front of the Quarter Court of Virginia. This public display challenged the conventional gender roles in the colony. After hearing Thomas's account, the governor delivered an extraordinary verdict: Thomas(ine) was declared to be both a man and a woman. As a result, Thomas(ine) was mandated to wear clothing representing both genders: men's breeches and shirt, along with a woman's cap and apron. The new clothing prevented Thomas(ine) from blending in with colonial society ever again. Although this might have been perceived as the community's desired punishment, the court failed to address the questions regarding Thomas(ine)'s future work capabilities. Thomas(ine) disappeared, but this case shows how gender was understood and controlled in the English colonies.

Public Domain

Public Domain

Enslaved Women:

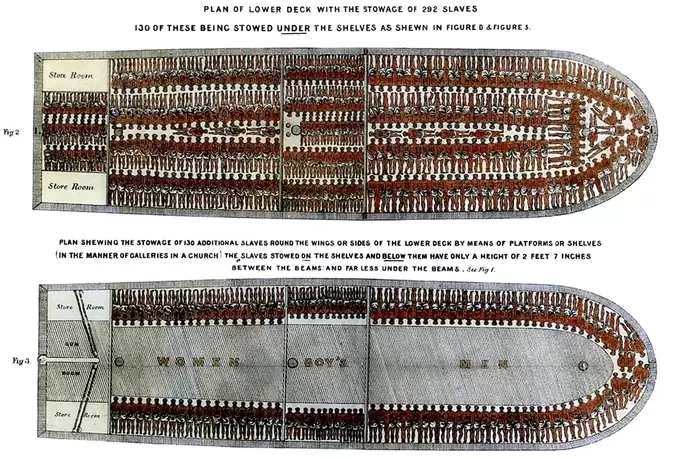

As the English battled nature to "settle" and tame these new lands, they required human labor. Native Americans died from European diseases at unimaginable rates. So, to keep the supply of cheap laborers coming, the colonists turned to the already thriving slave trade.

On August 20, 1619, a ship carrying “20 and odd” Angolans kidnapped by Portuguese traders was privateered by the English and landed in Jamestown. The arrival of these enslaved Africans marks the beginning of African slavery in North America. Between 150 of the 350 people onboard the ship died during the crossing due to the horrendous conditions and exposure to new diseases. The ship had been attacked by two privateer ships, and crews from the two ships kidnapped up to 60 of the enslaved people separating them from those they may have known. Although slavery was not yet contingent on race in Virginia– racism toward Africans was not new to the English. In England Africans had become the scapegoat for society's problems and even Queen Elizabeth declared "blackamoors" to be driven from the land.

Almost all the enslaved passengers in 1619 are nameless in history. Angela was named and listed. She disappears from the record in 1625 for unknown reasons. Isabela and her partner Anthony remained in Virginia and eventually had a son.

Given the horrors of the middle passage, it is no wonder the enslaved rebelled and despite the power differences, did so in large numbers. Quantitative historians have found that one in ten of the more than 36,000 ships that crossed the middle passage in a four year period had a slave insurrection on board. What empowered these people to rebel? The only relevant correlation they could find for why these rebellions occurred, was that the more women, the more likely a rebellion.

Women were treated differently during transport. Sometimes they were spared the cramped, disease ridden spaces below deck in order to entertain the European enslavers above deck. There, though experiencing unmentionable crimes, they were sometimes left unchained and within proximity of weapons. Their enslavers may have underestimated them, or may have assumed they were less likely to rebel than their male counterparts.

The ship log for a much later ship, the Thomas, in 1797 stated, “two or three of the female slaves have they discovered that the armorer had incautiously left the arms chest open… conveyed all the arms, which they could find, threw the ball kids to the male slaves, about 200 of them immediately ran up the force cuddles and put to death all the crew who had came in their way.”

Others weren’t so unwise. In 1776, one enslaver aboard the Thames noted, “For your safety as well as mine… You’ll have the needful guard over your Slaves, and put not too much confidence in the Women nor Children lest they happen to be instrumental in your being surprised which may be fatal.”

As the English battled nature to "settle" and tame these new lands, they required human labor. Native Americans died from European diseases at unimaginable rates. So, to keep the supply of cheap laborers coming, the colonists turned to the already thriving slave trade.

On August 20, 1619, a ship carrying “20 and odd” Angolans kidnapped by Portuguese traders was privateered by the English and landed in Jamestown. The arrival of these enslaved Africans marks the beginning of African slavery in North America. Between 150 of the 350 people onboard the ship died during the crossing due to the horrendous conditions and exposure to new diseases. The ship had been attacked by two privateer ships, and crews from the two ships kidnapped up to 60 of the enslaved people separating them from those they may have known. Although slavery was not yet contingent on race in Virginia– racism toward Africans was not new to the English. In England Africans had become the scapegoat for society's problems and even Queen Elizabeth declared "blackamoors" to be driven from the land.

Almost all the enslaved passengers in 1619 are nameless in history. Angela was named and listed. She disappears from the record in 1625 for unknown reasons. Isabela and her partner Anthony remained in Virginia and eventually had a son.

Given the horrors of the middle passage, it is no wonder the enslaved rebelled and despite the power differences, did so in large numbers. Quantitative historians have found that one in ten of the more than 36,000 ships that crossed the middle passage in a four year period had a slave insurrection on board. What empowered these people to rebel? The only relevant correlation they could find for why these rebellions occurred, was that the more women, the more likely a rebellion.

Women were treated differently during transport. Sometimes they were spared the cramped, disease ridden spaces below deck in order to entertain the European enslavers above deck. There, though experiencing unmentionable crimes, they were sometimes left unchained and within proximity of weapons. Their enslavers may have underestimated them, or may have assumed they were less likely to rebel than their male counterparts.

The ship log for a much later ship, the Thomas, in 1797 stated, “two or three of the female slaves have they discovered that the armorer had incautiously left the arms chest open… conveyed all the arms, which they could find, threw the ball kids to the male slaves, about 200 of them immediately ran up the force cuddles and put to death all the crew who had came in their way.”

Others weren’t so unwise. In 1776, one enslaver aboard the Thames noted, “For your safety as well as mine… You’ll have the needful guard over your Slaves, and put not too much confidence in the Women nor Children lest they happen to be instrumental in your being surprised which may be fatal.”

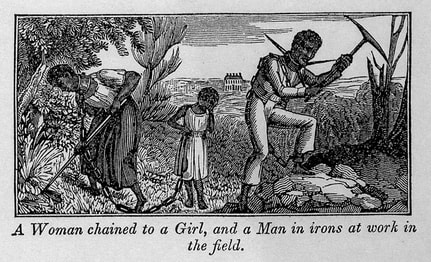

Later anti-slavery sketch, Library of Congress

Later anti-slavery sketch, Library of Congress

Mary Johnson arrived before 1620 as the indentured maid of a planter. Free Black people were common in these early years. In the south, Black women used their talents to become prominent business women– white merchants complained endlessly about them. Trading women were bold and unafraid to speak up. One man said that the “insolent and abusive manner [of these women made him] afraid to say or do anything.”

In 1662, Virginia instituted a law that would become common wherever slavery existed in the US. It stated: “Be it therefore enacted and declared… that all children borne in this country shalbe held bond or free only according to the condition of the mother, And that if any christian shall committ fornication with a negro man or woman, hee or shee soe offending shall pay double the fines imposed by the former act.”

In just about every other western civilization, a person’s status was defined by their father. Your status as free, enslaved, aristocrat, wealthy, poor, was determined by your father’s status in life (and, potentially, whether he recognized you as his offspring). But this law indicates that a child’s status in Virginia would be based on the mother. Why would a British colony basically turn its back on years of custom and common law? What effect did this law have? The answer is mostly practical. While paternity could be questioned, maternity could not. A child’s status in colonial society would be immediately apparent and unmistakable.

In practice, this law gave enslavers free reign to sexually assault their female slaves in order to produce more slaves, as the children of enslaved women would be slaves for life regardless of who their father was. Not all enslavers assaulted enslaved women on their plantations, others chose to breed the enslaved people like animals. Male slaves, as well as females, had limited–if any–agency in who they could engage in sexual relations with.

In 1662, Virginia instituted a law that would become common wherever slavery existed in the US. It stated: “Be it therefore enacted and declared… that all children borne in this country shalbe held bond or free only according to the condition of the mother, And that if any christian shall committ fornication with a negro man or woman, hee or shee soe offending shall pay double the fines imposed by the former act.”

In just about every other western civilization, a person’s status was defined by their father. Your status as free, enslaved, aristocrat, wealthy, poor, was determined by your father’s status in life (and, potentially, whether he recognized you as his offspring). But this law indicates that a child’s status in Virginia would be based on the mother. Why would a British colony basically turn its back on years of custom and common law? What effect did this law have? The answer is mostly practical. While paternity could be questioned, maternity could not. A child’s status in colonial society would be immediately apparent and unmistakable.

In practice, this law gave enslavers free reign to sexually assault their female slaves in order to produce more slaves, as the children of enslaved women would be slaves for life regardless of who their father was. Not all enslavers assaulted enslaved women on their plantations, others chose to breed the enslaved people like animals. Male slaves, as well as females, had limited–if any–agency in who they could engage in sexual relations with.

Enslaved women at work, Wikimedia Commons

Enslaved women at work, Wikimedia Commons

Racist ideas about African people, especially women contributed to their different treatment. Black women were eroticized and deemed exotic by European men. They were believed to be the enduring, lustful Jezebel whose sexuality needed to be controlled. For as long as these laws and slavery reigned, enslaved women would be denied reproductive justice and control over their bodies.

These notions about African women were increasingly opposite to the views held for white women. Enslaved women did every imaginable job alongside men. They labored in fields, served in domestic roles, and became master seamstresses, weavers, some earning money in the markets.

One job specific to enslaved women was wet nursing, when enslaved women were forced to provide sustenance to the offspring of their enslavers. Wealthy Englishwomen were accustomed to the practice of hiring a poor woman to breastfeed her babies. In the colonies, both poor white mothers and enslaved Black mothers were both used for this purpose. But for enslaved women, this was forced on them. Often separated from their own children, who were weaned from breast milk far too young, Black mothers were exploited for their milk.

Not all Black people in the Americas were enslaved, in fact, many of the original “20 and odd” Africans brought to North America were treated as indentured servants. But gradually as more people came and more laws were passed to protect slavery by dividing groups that had similar interests (like poor white people, indentured servants, etc), American slavery became synonymous with race as well as a life sentence. Slavery spread throughout the colonies, so that no colony could claim to be innocent of it. Even in the north.

These notions about African women were increasingly opposite to the views held for white women. Enslaved women did every imaginable job alongside men. They labored in fields, served in domestic roles, and became master seamstresses, weavers, some earning money in the markets.

One job specific to enslaved women was wet nursing, when enslaved women were forced to provide sustenance to the offspring of their enslavers. Wealthy Englishwomen were accustomed to the practice of hiring a poor woman to breastfeed her babies. In the colonies, both poor white mothers and enslaved Black mothers were both used for this purpose. But for enslaved women, this was forced on them. Often separated from their own children, who were weaned from breast milk far too young, Black mothers were exploited for their milk.

Not all Black people in the Americas were enslaved, in fact, many of the original “20 and odd” Africans brought to North America were treated as indentured servants. But gradually as more people came and more laws were passed to protect slavery by dividing groups that had similar interests (like poor white people, indentured servants, etc), American slavery became synonymous with race as well as a life sentence. Slavery spread throughout the colonies, so that no colony could claim to be innocent of it. Even in the north.

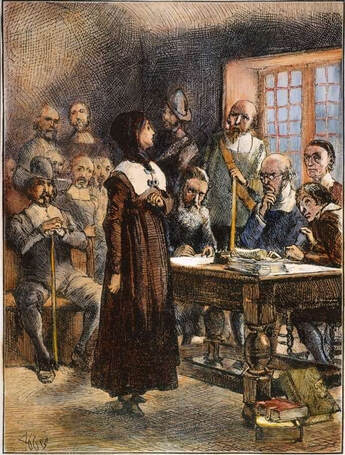

Anne Hutchinson on trial, Public Domain

Anne Hutchinson on trial, Public Domain

Massachusetts:

When the Massachusetts Bay Colony was settled, the types of people that came were mostly families. 17 women were aboard the Mayflower that landed at an abandoned Wompanoag village on Cape Cod in 1620. We do not know their thoughts upon landing. But we do know that Dorothy Bradford, the Governor’s wife, fell overboard in the calm waters of the bay while the men went ashore and drowned. Bradford barely recorded his wife’s death, writing “Death. Dec. 7. Dorothy, Wife to Mr. William Bradford.” Was she so distraught from the journey? Was she horrified at the cold New England scene? Was she longing for her life back home and the son she left behind? Did she commit suicide? Historians may never know. We do know that Mary Chilton, a 13-year old, was the first English woman to disembark.

In what would become the Massachusetts Bay colony, the first settlers were a mix of religious separatists and Puritans. The colony functioned largely like a Puritan theocracy. Women, daughters of the biblical Eve who “corrupted Adam” into eating the apple, did not have the right to question their male heads of house.

Nevertheless, women had to eschew traditional gender roles and ideals in order for the colony to survive. They worked the land, did construction, and ran businesses– things their sisters in England would have been appalled by. 10 percent of people involved in trade in Boston were women– mostly widows. Elizabeth Poole purchased land from the Wompanoag and was a stockholder in the ironworks. Many businesses that were “run by men” were actually run by their wives, while they traveled.

Some women did not take kindly to the Puritan leadership’s treatment of women and began standing against the government. Perhaps most notable was Anne Hutchinson. Like many women of her time, Hutchinson gave birth to over a dozen children. She was not formally educated, but learned to read and write. Hutchinson was forty-three years old when she arrived in Boston in 1634 from England. As a midwife, Hutchinson developed strong ties to local women and began holding meetings in her home. She became a spiritual leader and stood against the all-male authority, which was a challenge to acceptable gender roles. She gained a following of both men and women by questioning Puritan teachings about salvation.

When church and community leaders became aware of her popularity and the content of her preaching she was put on trial for heresy. Oddly, the trial did not condemn her for her religious ideas, but rather, took issue with the fact that those ideas were coming from a woman.

In the trial, Governor Winthrop said, “Mrs. Hutchinson, you are called here as one of those that have troubled the peace of the commonwealth… you are known to be a woman that hath had a great share in the promoting and divulging of those opinions that are the cause of this trouble… and you have maintained a meeting and an assembly in your house that hath been condemned by the general assembly as a thing not tolerable… in the sight of God nor fitting for your sex.”

At a time when men ruled and women were expected to remain silent, Hutchinson asserted her right to preach and overstepped her presumed place “as a woman.” Hutchinson’s husband supported her, but her former mentor, Reverend John Cotton, turned on her, describing her meetings as a “promiscuous and filthy coming together of men and women…” Hutchinson was excommunicated and their family was banished from the colony–forced to move away. Eventually, she and her children were killed in a raid by Native Americans, which some people think was provoked by the Puritans.

When the Massachusetts Bay Colony was settled, the types of people that came were mostly families. 17 women were aboard the Mayflower that landed at an abandoned Wompanoag village on Cape Cod in 1620. We do not know their thoughts upon landing. But we do know that Dorothy Bradford, the Governor’s wife, fell overboard in the calm waters of the bay while the men went ashore and drowned. Bradford barely recorded his wife’s death, writing “Death. Dec. 7. Dorothy, Wife to Mr. William Bradford.” Was she so distraught from the journey? Was she horrified at the cold New England scene? Was she longing for her life back home and the son she left behind? Did she commit suicide? Historians may never know. We do know that Mary Chilton, a 13-year old, was the first English woman to disembark.

In what would become the Massachusetts Bay colony, the first settlers were a mix of religious separatists and Puritans. The colony functioned largely like a Puritan theocracy. Women, daughters of the biblical Eve who “corrupted Adam” into eating the apple, did not have the right to question their male heads of house.

Nevertheless, women had to eschew traditional gender roles and ideals in order for the colony to survive. They worked the land, did construction, and ran businesses– things their sisters in England would have been appalled by. 10 percent of people involved in trade in Boston were women– mostly widows. Elizabeth Poole purchased land from the Wompanoag and was a stockholder in the ironworks. Many businesses that were “run by men” were actually run by their wives, while they traveled.

Some women did not take kindly to the Puritan leadership’s treatment of women and began standing against the government. Perhaps most notable was Anne Hutchinson. Like many women of her time, Hutchinson gave birth to over a dozen children. She was not formally educated, but learned to read and write. Hutchinson was forty-three years old when she arrived in Boston in 1634 from England. As a midwife, Hutchinson developed strong ties to local women and began holding meetings in her home. She became a spiritual leader and stood against the all-male authority, which was a challenge to acceptable gender roles. She gained a following of both men and women by questioning Puritan teachings about salvation.

When church and community leaders became aware of her popularity and the content of her preaching she was put on trial for heresy. Oddly, the trial did not condemn her for her religious ideas, but rather, took issue with the fact that those ideas were coming from a woman.

In the trial, Governor Winthrop said, “Mrs. Hutchinson, you are called here as one of those that have troubled the peace of the commonwealth… you are known to be a woman that hath had a great share in the promoting and divulging of those opinions that are the cause of this trouble… and you have maintained a meeting and an assembly in your house that hath been condemned by the general assembly as a thing not tolerable… in the sight of God nor fitting for your sex.”

At a time when men ruled and women were expected to remain silent, Hutchinson asserted her right to preach and overstepped her presumed place “as a woman.” Hutchinson’s husband supported her, but her former mentor, Reverend John Cotton, turned on her, describing her meetings as a “promiscuous and filthy coming together of men and women…” Hutchinson was excommunicated and their family was banished from the colony–forced to move away. Eventually, she and her children were killed in a raid by Native Americans, which some people think was provoked by the Puritans.

Mary Dyer, Wikimedia Commons

Mary Dyer, Wikimedia Commons

Hutchinson was a popular figure and many notable women were moved to her cause, including Mary Dyer. Dyer joined with Hutchinson and was thus expelled with her. Prior to expulsion, Dyer had given birth to a stillborn baby in Massachusetts. After she left, Winthrop had the baby’s body exhumed and examined. He wrote a description of the baby’s deformed body and had it sent around the English world as evidence of God’s punishment for Hutchinson and Dyer’s heresy. At the time, many Puritans believed in the idea that “monstrous births,”or the births of children with varying levels of deformity or defect such as to label them “monstrous,” were manifestations of the mother’s “sickness”--in this case, Dyer’s heretical behavior.

Dyer left New England and converted to Quakerism. She became a preacher, which was allowed within the Quaker faith, and returned to New England to protest a new law that banned Quakers in 1657. She traveled

"The Dukes Plan," by Robert Holmes, British Library. A decorative map showing the English fleet sailing into New Amsterdam in 1664.

Through New England preaching and was eventually arrested. She would go on to be arrested, tried, and banished numerous times. Once, two Quakers were hung next to her and she was spared because she was a woman. She was banished from Massachusetts, but Dyer was unrelenting. Despite pleas from her husband and family, she traveled again to Massachusetts, was arrested and hung for her religious beliefs and actions. Her last words were, “Nay, I came to keep bloodguiltiness from you, desiring you to repeal the unrighteous and unjust law made against the innocent servants of the Lord. Nay, man, I am not now to repent."

Dyer left New England and converted to Quakerism. She became a preacher, which was allowed within the Quaker faith, and returned to New England to protest a new law that banned Quakers in 1657. She traveled

"The Dukes Plan," by Robert Holmes, British Library. A decorative map showing the English fleet sailing into New Amsterdam in 1664.

Through New England preaching and was eventually arrested. She would go on to be arrested, tried, and banished numerous times. Once, two Quakers were hung next to her and she was spared because she was a woman. She was banished from Massachusetts, but Dyer was unrelenting. Despite pleas from her husband and family, she traveled again to Massachusetts, was arrested and hung for her religious beliefs and actions. Her last words were, “Nay, I came to keep bloodguiltiness from you, desiring you to repeal the unrighteous and unjust law made against the innocent servants of the Lord. Nay, man, I am not now to repent."

Purchase of Manhattan, for visual representation only, Public Domain

Purchase of Manhattan, for visual representation only, Public Domain

New Netherlands:

The English were not the only ones interested in North America; the Dutch, too, established settlements in “New Netherland,” an area encompassing parts of modern day Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Delaware, Pennsylvania and Maryland. Dutch explorers mapped out the major waterways and drew remarkably accurate maps in the early 1600s. They established an intricate three-way trade between the Pequots and the Mohawks and built forts to secure their trade. But by mid-century, few Dutch settlers came and tensions with both the Lenape and their English neighbors were rising.

Despite protest, English migrants, unhappy in Puritan Massachusetts, increasingly settled in Dutch territories. In 1637, tensions between the various groups resulted in one of the worst massacres of Indigenous peoples. Mystic, Connecticut was home to the Pequot tribe, whose reduced territory lay east of the Fresh River. The new English settlers disrupted an otherwise peaceful and mutually beneficial trade. Tensions increased following a series of murders. Ultimately, the crisis ended with an inconceivably horrible massacre led by Englishman, Captain John Mason on May 26, 1637. He burned the Pequot village, killing as many as 700 people, including women and children. The Pequot who survived attempted to hunt down the English on their return to Massachusetts, but failed. Surviving Pequot who were captured were enslaved by the English, but they did not submit. As a result, the Massachusetts colonists shipped the Pequot to Bermuda where they were traded for African slaves. In 1638, the first Africans were forcibly imported to Massachusetts on a cargo ship, including two African women.

English lust for control did not end and was not just directed against people of color. In 1664, the English invaded Long Island, seizing the heart of Dutch territories in the Americas. The two European powers were in a standoff that the Dutch knew they would lose without reinforcements. Instead of fighting or committing treason by negotiating, the Dutch navigated this complicated situation by sending in the wives of two councilmen to negotiate a peace: Lydia de Meyer and Hillegond van Ruyven. Both women had status in the fort and were thus respected as negotiators by the English. The women deescalated the situation and protected their people. Hillegond’s account to the Dutch investigators was scathing, “Now these dirty dogs want to fight, now that they’ve got nothing to lose. And we have our property here, which we would lose if we fought.” For her the human life in New Amsterdam was more important than the pride of the Dutch government.

The hostile English invaders then turned to secure peace with the Indigenous communities in the region by signing new contracts and treaties with their neighbors. In 1670, they purchased Staten Island from the Lenni-Lenape. The contract was signed by ten young people to reflect what they hoped would last generations. No English girls were present, but three Lenni-Lenape girls signed, reflecting the stark differences in women’s rights and powers in the two cultures.

The English were not the only ones interested in North America; the Dutch, too, established settlements in “New Netherland,” an area encompassing parts of modern day Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Delaware, Pennsylvania and Maryland. Dutch explorers mapped out the major waterways and drew remarkably accurate maps in the early 1600s. They established an intricate three-way trade between the Pequots and the Mohawks and built forts to secure their trade. But by mid-century, few Dutch settlers came and tensions with both the Lenape and their English neighbors were rising.

Despite protest, English migrants, unhappy in Puritan Massachusetts, increasingly settled in Dutch territories. In 1637, tensions between the various groups resulted in one of the worst massacres of Indigenous peoples. Mystic, Connecticut was home to the Pequot tribe, whose reduced territory lay east of the Fresh River. The new English settlers disrupted an otherwise peaceful and mutually beneficial trade. Tensions increased following a series of murders. Ultimately, the crisis ended with an inconceivably horrible massacre led by Englishman, Captain John Mason on May 26, 1637. He burned the Pequot village, killing as many as 700 people, including women and children. The Pequot who survived attempted to hunt down the English on their return to Massachusetts, but failed. Surviving Pequot who were captured were enslaved by the English, but they did not submit. As a result, the Massachusetts colonists shipped the Pequot to Bermuda where they were traded for African slaves. In 1638, the first Africans were forcibly imported to Massachusetts on a cargo ship, including two African women.

English lust for control did not end and was not just directed against people of color. In 1664, the English invaded Long Island, seizing the heart of Dutch territories in the Americas. The two European powers were in a standoff that the Dutch knew they would lose without reinforcements. Instead of fighting or committing treason by negotiating, the Dutch navigated this complicated situation by sending in the wives of two councilmen to negotiate a peace: Lydia de Meyer and Hillegond van Ruyven. Both women had status in the fort and were thus respected as negotiators by the English. The women deescalated the situation and protected their people. Hillegond’s account to the Dutch investigators was scathing, “Now these dirty dogs want to fight, now that they’ve got nothing to lose. And we have our property here, which we would lose if we fought.” For her the human life in New Amsterdam was more important than the pride of the Dutch government.

The hostile English invaders then turned to secure peace with the Indigenous communities in the region by signing new contracts and treaties with their neighbors. In 1670, they purchased Staten Island from the Lenni-Lenape. The contract was signed by ten young people to reflect what they hoped would last generations. No English girls were present, but three Lenni-Lenape girls signed, reflecting the stark differences in women’s rights and powers in the two cultures.

Sarah Grendon, Public Domain

Sarah Grendon, Public Domain

Bacon’s Rebellion:

Back in Virginia, tensions collided between cultures, classes, and the Indigenous people on the frontier and came to a head by the 1670s. Virginian society was highly unequal and the poor frontier person's most bitter complaint was that the governor of Virginia traded furs with the Natives and got rich, but would not come protect them from raids on their lands.

It was white frontier wives who were perhaps the most enthusiastic about genocidal war against the natives because they were often home alone while their spouses traded. When Nathanial Bacon decided to overthrow the government, women were some of his most ardent supports. Sarah Grendon’s enthusiasm came out when she said, “I fear the power of England no more than a broken straw.”

When Bacon attacked Jamestown he rounded up the wives of the wealthy powerful men and strapped them to the ramparts.If the leaders of Jamestown wanted to get to Bacon and suppress the rebellion, they would have to go through their own wives first. Nevertheless, Lady Frances Berkley, the wife of the governor, fled for London and returned with a thousand troops.

After Bacon’s defeat, his followers, including the women, were rounded up. Sarah Grendon escaped the death penalty by pleading that she was simply an “ignorant woman.”

Back in Virginia, tensions collided between cultures, classes, and the Indigenous people on the frontier and came to a head by the 1670s. Virginian society was highly unequal and the poor frontier person's most bitter complaint was that the governor of Virginia traded furs with the Natives and got rich, but would not come protect them from raids on their lands.

It was white frontier wives who were perhaps the most enthusiastic about genocidal war against the natives because they were often home alone while their spouses traded. When Nathanial Bacon decided to overthrow the government, women were some of his most ardent supports. Sarah Grendon’s enthusiasm came out when she said, “I fear the power of England no more than a broken straw.”

When Bacon attacked Jamestown he rounded up the wives of the wealthy powerful men and strapped them to the ramparts.If the leaders of Jamestown wanted to get to Bacon and suppress the rebellion, they would have to go through their own wives first. Nevertheless, Lady Frances Berkley, the wife of the governor, fled for London and returned with a thousand troops.

After Bacon’s defeat, his followers, including the women, were rounded up. Sarah Grendon escaped the death penalty by pleading that she was simply an “ignorant woman.”

Mary Rowlandson, Public Domain

Mary Rowlandson, Public Domain

King Philip's War:

The women of New England were not much better than Virginia women in terms of their treatment of the Indigenous populations. By 1675, colonists in New England were engaged in the bloodiest war in US History (as a percentage of the population) with the Wampanoag Confederacy.

From the time of English arrival in Massachusetts, the Wompanoag had seen much of their world change, and European diseases had killed 90% of the tribes in New England. The Wompanaog were a matrilineal people, passing inheritance through female lines. Weetamoo was the leader of one of the tribes in the Wampanoag Confederacy and sister-in-law to the Great Sachem. In her lifetime, she married many times to form alliances that held the Confederacy together. When her husband died in English custody, she called foul. Time passed and she remarried, but eventually things between the Wampanoag and the English became too tense and her sister’s husband, Metacom, called Philip by the English, went to war. Weetamoo’s various marriages throughout her life meant that she commanded the allegiance of every major tribe in the Confederacy. Weetamoo had to decide whether to lead her people to war or try to negotiate. She had witnessed, and actively resisted through land deeds, the encroachment of the English on land supposedly belonging to her people. While her husband sided with the English, she sided with Metacom. She dissolved the political marriage and turned those allied with her against the English.

During the war, a colonist named Mary Rowlandson was captured and brought to Weetamoo. She was held for 11 weeks. Years later she published a book about her experience that we can read as a primary account. Rowlandson complained that Weetamoo didn’t give her enough to eat. In reality, Weetamoo was in charge of a massive war effort in a time of scarcity. Rowlandson was ransomed home, while Weetamoo was killed [?] during the war. Her decapitated head was brought back as a trophy and when the imprisoned Wampanoag saw it, they wailed in agony over the death of their leader.

After the war, so much changed in New England. The indigenous people who were still living there were sold into slavery or pushed further west. Some fled and joined with neighboring tribes on the outskirts of the region. Many natives, like the Abeneki Nation of northern New England, resorted to raiding English villages for supplies, sometimes killing or capturing settlers, and ransoming captives back to their families.

Hannah Emerson Duston lived in Haverhill, Massachusetts and was a victim of these political tensions. She was 40-years old when the Abeneki raided her town capturing some of the women. Duston had given birth about a week before. Cotton Mather, who provided the only account of the event, wrote that the raiders smashed her baby against a tree, killing it. The Abenaki brought the women up the Merrimack River deep into modern day New Hampshire, making camp on a small island in the river. Duston got hold of a hatchet and massacred her captors. She was then able to load the other women in the canoes and paddle home to Massachusetts. Duston’s massacre and the political tensions that surround it unfortunately represent how many of these initial cultural encounters took shape.

The women of New England were not much better than Virginia women in terms of their treatment of the Indigenous populations. By 1675, colonists in New England were engaged in the bloodiest war in US History (as a percentage of the population) with the Wampanoag Confederacy.

From the time of English arrival in Massachusetts, the Wompanoag had seen much of their world change, and European diseases had killed 90% of the tribes in New England. The Wompanaog were a matrilineal people, passing inheritance through female lines. Weetamoo was the leader of one of the tribes in the Wampanoag Confederacy and sister-in-law to the Great Sachem. In her lifetime, she married many times to form alliances that held the Confederacy together. When her husband died in English custody, she called foul. Time passed and she remarried, but eventually things between the Wampanoag and the English became too tense and her sister’s husband, Metacom, called Philip by the English, went to war. Weetamoo’s various marriages throughout her life meant that she commanded the allegiance of every major tribe in the Confederacy. Weetamoo had to decide whether to lead her people to war or try to negotiate. She had witnessed, and actively resisted through land deeds, the encroachment of the English on land supposedly belonging to her people. While her husband sided with the English, she sided with Metacom. She dissolved the political marriage and turned those allied with her against the English.

During the war, a colonist named Mary Rowlandson was captured and brought to Weetamoo. She was held for 11 weeks. Years later she published a book about her experience that we can read as a primary account. Rowlandson complained that Weetamoo didn’t give her enough to eat. In reality, Weetamoo was in charge of a massive war effort in a time of scarcity. Rowlandson was ransomed home, while Weetamoo was killed [?] during the war. Her decapitated head was brought back as a trophy and when the imprisoned Wampanoag saw it, they wailed in agony over the death of their leader.

After the war, so much changed in New England. The indigenous people who were still living there were sold into slavery or pushed further west. Some fled and joined with neighboring tribes on the outskirts of the region. Many natives, like the Abeneki Nation of northern New England, resorted to raiding English villages for supplies, sometimes killing or capturing settlers, and ransoming captives back to their families.

Hannah Emerson Duston lived in Haverhill, Massachusetts and was a victim of these political tensions. She was 40-years old when the Abeneki raided her town capturing some of the women. Duston had given birth about a week before. Cotton Mather, who provided the only account of the event, wrote that the raiders smashed her baby against a tree, killing it. The Abenaki brought the women up the Merrimack River deep into modern day New Hampshire, making camp on a small island in the river. Duston got hold of a hatchet and massacred her captors. She was then able to load the other women in the canoes and paddle home to Massachusetts. Duston’s massacre and the political tensions that surround it unfortunately represent how many of these initial cultural encounters took shape.

A 1685 Map of the English Colonies

A 1685 Map of the English Colonies

Conclusion:

What is there to make of all of this? The English and the Dutch sought colonies in the New World, but approached those goals in different ways. The Dutch sought to trade with their Indigenous neighbors, while the English encroached on their land and expelled them from it. These examples show us that, in history, individuals make choices..

African peoples were brought to the Americas by force and it was their labor that ensured the success of the colonies. But both they and the Indigenous peoples resisted against the European colonists at every opportunity.

Violent encounters between cultures in British North America occurred because of the choices that people made, and English women and their Dutch, Powhatan, Lenni-Lenape, Wampanoag, and African counterparts were central to the stories that defined this period.

By the end of this era, so much remained in question. Was it possible for Native Americans and the English to find peace after such a horrible beginning? Would women be able to use the challenges of frontier life to forge greater freedoms for themselves? And how would the treatment of enslaved women shape the evolution of American slavery and history?

What is there to make of all of this? The English and the Dutch sought colonies in the New World, but approached those goals in different ways. The Dutch sought to trade with their Indigenous neighbors, while the English encroached on their land and expelled them from it. These examples show us that, in history, individuals make choices..

African peoples were brought to the Americas by force and it was their labor that ensured the success of the colonies. But both they and the Indigenous peoples resisted against the European colonists at every opportunity.

Violent encounters between cultures in British North America occurred because of the choices that people made, and English women and their Dutch, Powhatan, Lenni-Lenape, Wampanoag, and African counterparts were central to the stories that defined this period.

By the end of this era, so much remained in question. Was it possible for Native Americans and the English to find peace after such a horrible beginning? Would women be able to use the challenges of frontier life to forge greater freedoms for themselves? And how would the treatment of enslaved women shape the evolution of American slavery and history?

Draw your own conclusions

|

Learn how to teach with inquiry.

Many of these lesson plans were sponsored in part by the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources Eastern Region Program, coordinated by Waynesburg University, the History and Social Studies Education Faculty at Plymouth State University, and the Patrons of the Remedial Herstory Project. |

Lesson Plans from Other Organizations

- The National Women's History Museum has lesson plans on women's history.

- The Gilder Lehrman Institute for American History has lesson plans on women's history.

- The NY Historical Society has articles and classroom activities for teaching women's history.

- Unladylike 2020, in partnership with PBS, has primary sources to explore with students and outstanding videos on women from the Progressive era.

- The Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media has produced recommendations for teaching women's history with primary sources and provided a collection of sources for world history. Check them out!

- The Stanford History Education Group has a number of lesson plans about women in US History.

Period Specific Lesson Plans from Other Organizations

- First Encounters:

- Gilder Lehrman: The conclusion that encounters between European settlers and Native Americans changed the lives of both groups has been central to many historical accounts of colonial history. While the arguments made are convincing, the discussions do not directly address the lives of women. It is possible that this omission is a result of a paucity of sources. Regardless of the problems with sources, the question may still be asked: Does this assumption hold up when we look at the encounter of women of both cultures? If not, why not? Before we can consider questions such as these, we need to look at the available primary sources for seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century women and gather as much useful information as we can. Because there is not a wealth of primary sources available on the Internet on these women, we need to read what we do have carefully and learn as much as we can. Hopefully, this will enable us to analyze and write this history. In this lesson, students will use primary and secondary sources to research and understand the lives of women (both Native American and European) in North America in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

- NY Historical Society: Women were an integral part of the daily life and success of New Netherland. They served as translators between the Dutch government and the local Native tribes, and acted as liaisons during negotiations with enemy forces. Women were at the center of the colony’s struggle to define the terms of slavery and freedom for the black colonials who lived in the territory. Dutch women actively participated in the bustling trade in the colony, while Native women manipulated imperial power structures to ensure their own survival. And all women in New Netherland contributed to the survival of the colony while still carrying out the responsibilities of home and child care.

- NY Historical Society: The traditional role of women in English society was one of subordination or second-class status. Women were expected to answer to their fathers, their husbands, and their religious and political leaders. The English common law practice of coverture made it so married women did not legally or economically exist, so they could not be free. But women were hard at work affecting the colonies in many ways, from enslaved women bringing agricultural knowledge that made colonies flourish to housewives inventing new ways to perform basic tasks. Women took part in the armed resistance to European invasion, and challenged the gender norms they were forced to live under. The power of women was well recognized by English colonial governments, who made laws to govern their reproduction, tried them for heresy and witchcraft, and severely punished their crimes, even when the women themselves were not at fault. The very first published poet of the English colonies was a woman. Even though the odds were against them, the women of the early English colonies were important to the development of the New World.

- NY Historical Society: King Philip’s War proved disastrous for Weetamoo and her people. After a strong start, vicious English counterattacks wore away at the tribal alliance. Wampanoag society was destroyed. At least 750 Wampanoag were killed during the war, and all the Wampanoag who were captured were sold into slavery. Weetamoo drowned while crossing a river on her way to battle. Her body was found by English soldiers on August 3, 1676. She was so feared that the soldiers mounted her head on a pole outside an English settlement as proof that she had been defeated. The sight of her head sent captive Native warriors into a frenzy of grief, proof of the love she inspired in her people. Her endeavors may have failed, but her life story stands as a testament to the ways women in Native communities fought back against the aggression of European settlers.

- Stanford History Education Group: Examining Passenger Lists: What can passenger lists from ships arriving in North American colonies tell us about those who immigrated? And what can those characteristics tell us about life in the colonies themselves? In this lesson, students critically examine the passenger lists of ships headed to New England and Virginia to better understand English colonial life in the 1630s.

- Stanford History Education Group: Pocahontas: Thanks to the Disney film, most students know the legend of Pocahontas. But is the story told in the 1995 movie accurate? In this lesson, students use evidence to explore whether Pocahontas actually saved John Smith’s life and practice the ability to source, corroborate, and contextualize historical documents.

- Gilder Lehrman: The early seventeenth century was punctuated by a series of small wars between Native Americans and colonists. Many colonists were captured and taken prisoner, but two women, whose ordeals were published as books, stand out. Mary Rowlandson wrote an account of her 1675 capture and escape, The Narrative of the Captivity and the Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson, in which she described her captivity and treatment by the Native Americans during King Phillip’s War. Hannah Dustin was captured in 1675, during King William’s War, and fought her way to freedom. Her story was written by Cotton Mather in Magnalia Christi Americana. The stories of these two women were read widely both in America and in England.

- Anne Hutchinson:

- National History Day: Why was Anne Marbury Hutchinson expelled from Massachusetts? She was a Puritan immigrant to the Massachusetts Bay Colony from England. Her family, including her husband and 11 children, left their home in 1634 in support of their minister, John Cotton, who had assumed a position in the Church of Boston. Upon arriving, Hutchinson quickly gained a reputation as a “a woman of haughty and fierce carriage, of a nimble wit and active spirit, and a very voluble tongue, more bold than a man.” In the next three years, Hutchinson challenged two Puritan precepts. First, she was concerned with local ministers’ emphasis on a “covenant of works” opposed to a “covenant of grace” in their sermons. Secondly, she challenged the Puritan mores for women in attracting both men and women to her local religious gatherings in which she was critical of these ministers. By 1637, the Antinomian Controversy, sometimes referred to the Free Grace Controversy, erupted. Hutchinson was tried in civil and religious courts, banished from Boston, and excommunicated from the Puritan church. She relocated her family to Portsmouth (modern-day Rhode Island). In 1643, her family was massacred in an attack by the Siwanoy natives in New Netherland.

- National Women’s History Museum: Anne Hutchinson, in the 1630s, dared to demand that women have equal status in the Massachusetts Bay colony. This demand led to her leading mass meetings, then two court trials, banishment, and, finally her death. This lesson discusses Anne Hutchinson’s life and defying the misogyny of her times.

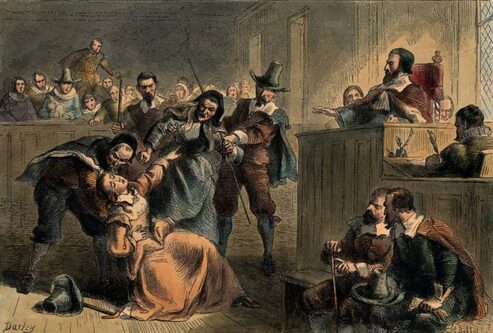

- Salem Witch Trials:

- Stanford History Education Group: Students are often captivated by the story of the Salem witch trials. But do they understand the deeper causes of the crisis? And do they see what the crisis reveals about life in Massachusetts at the end of the 17th century? In this lesson, students use four historical sources to build a more textured understanding of both the causes and historical context of these dramatic events.

Robert Beverly: On Bacon's Rebellion

Four things may … have been the main ingredients towards this ... commotion, ... First, The extreme low price of tobacco, and the ill [poor] usage of the planters in the exchange of goods for it, which the country, with all their earnest endeavors [efforts], could not remedy [set right]. Secondly, The splitting of the colony into proprieties, contrary to the original charters; and the extravagant [unreasonable] taxes they were forced to undergo, to relieve themselves from those grants. Thirdly, The heavy restraints and burdens laid upon their trade by act of Parliament in England. Fourthly, The disturbance given by the Indians. Of all which in their order.

As soon as General Bacon had marched to such a convenient distance from Jamestown that the assembly thought they might deliberate [plan] with safety, the governor, by their advice, issued a proclamation [announcement] of rebellion against him, commanding his followers to surrender him, and forthwith disperse themselves [immediately scatter], giving orders at the same time for raising the militia [military] of the country against him.

The people being much exasperated [frustrated], and General Bacon by his ... having gained an absolute dominion [control] over their hearts, they unanimously resolved [united agreement] that not a hair of his head should be touched, much less that they should surrender him as a rebel. Therefore they kept to their arms, and instead of proceeding against the Indians they marched back to Jamestown, directing their fury against such of their friends and countrymen as should dare to oppose them. . . .

It pleased God, after some months' confusion, to put an end to their misfortunes, as well as to Bacon's designs, by his natural death. He died at Dr. Green's in Gloucester county. But where he was buried was never yet discovered, though afterward there was great inquiry made, with design expose his bones to public infamy [dishonor]. …

The malcontents [rebels] being thus disunited by the loss of their general, in whom they all confided, they began to squabble among themselves, and every man's business was, how to make the best terms he could for himself.

Lieutenant General Ingram and Major General Walklate, surrendered, condition of pardon for themselves and their followers though they were both forced to submit to an incapacity[inability] of bearing office [position of authority] in that country for the future.

Peace being thus restored, Sir William Berkeley returned to his former seat of government, and every man to his several habitation [regular life]. . . .

Beverly, Robert. “An Account of Bacon’s Rebellion.” Digital History. Last modified 1704. https://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_textbook.cfm?smtID=3&psid=3998.

Questions:

As soon as General Bacon had marched to such a convenient distance from Jamestown that the assembly thought they might deliberate [plan] with safety, the governor, by their advice, issued a proclamation [announcement] of rebellion against him, commanding his followers to surrender him, and forthwith disperse themselves [immediately scatter], giving orders at the same time for raising the militia [military] of the country against him.

The people being much exasperated [frustrated], and General Bacon by his ... having gained an absolute dominion [control] over their hearts, they unanimously resolved [united agreement] that not a hair of his head should be touched, much less that they should surrender him as a rebel. Therefore they kept to their arms, and instead of proceeding against the Indians they marched back to Jamestown, directing their fury against such of their friends and countrymen as should dare to oppose them. . . .

It pleased God, after some months' confusion, to put an end to their misfortunes, as well as to Bacon's designs, by his natural death. He died at Dr. Green's in Gloucester county. But where he was buried was never yet discovered, though afterward there was great inquiry made, with design expose his bones to public infamy [dishonor]. …

The malcontents [rebels] being thus disunited by the loss of their general, in whom they all confided, they began to squabble among themselves, and every man's business was, how to make the best terms he could for himself.