13. 1000-1500 Women and Feudalism in Europe and Japan

|

In Europe and Japan, women labored in cottage industries and were an integral part of rigid caste systems. Lower class women had few rights, while upper class women had a small degree of freedom. In both cases, women found peace in nunneries and a few rose to positions of power.

|

Feudalism was the dominant social, political, and economic system in the Middle Ages in Europe and Japan. In this system, the nobility was gifted lands by the Monarch in exchange for military service as knights. Vassals rented and worked lands as tenants of the nobles. Peasants, also known as Serfs in some places, were given protection of sorts, but they basically lived as slaves on the land, paid homage to the nobles, labored hard, and had to give up portions of their crops. Women in Europe and Japan lived similar lives under feudalism.

In both regions, the lord of the land was responsible for and rigidly controlled all aspects of the lower class serf's life, including his wife and daughters. The lord chose brides for men, and the daughter of a serf was essentially property of the lord, as were her parents.

Married women were controlled under a system of coverture, where her interests and behavior were the responsibility of her husband. In legal battles, women are barely mentioned. A husband would be sued when a wife broke the law.

In both cultures, higher-class women were given more opportunities, but they were still held to strict sexual behaviors and expected to be mothers. There are exceptions to this "rule," but they were very rare. What was life like for poor and middle tier women?

Feudal Labor

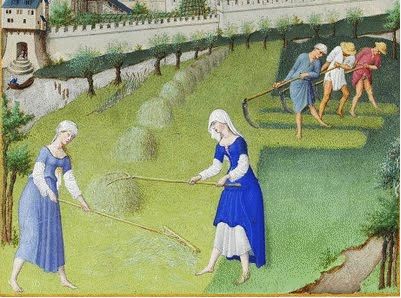

In the Middle Ages, women in Europe entered a period of great change. The planet warmed a bit, allowing for longer growing seasons, and this phenomenon led to a push to clear and settle more lands. The stability of the period also led to population growth. European cities reached the tens to hundred thousands. Population growth had an impact on women’s roles in society, and forced them into greater domestic responsibilities.

The majority lived in small rural farming societies. Peasant women had many domestic responsibilities, including caring for children, preparing food, and tending livestock. During the harvest, women worked in the fields too. Women labored in their communities, tending their children, their farms, their homes, and their family businesses. Working women were the fabric that held communities together, yet farm records only recorded the output of the farmer, ignoring the labor of his wife. This calculation is lost to history and we can find only glimpses in court records regarding defiant women.

In both regions, the lord of the land was responsible for and rigidly controlled all aspects of the lower class serf's life, including his wife and daughters. The lord chose brides for men, and the daughter of a serf was essentially property of the lord, as were her parents.

Married women were controlled under a system of coverture, where her interests and behavior were the responsibility of her husband. In legal battles, women are barely mentioned. A husband would be sued when a wife broke the law.

In both cultures, higher-class women were given more opportunities, but they were still held to strict sexual behaviors and expected to be mothers. There are exceptions to this "rule," but they were very rare. What was life like for poor and middle tier women?

Feudal Labor

In the Middle Ages, women in Europe entered a period of great change. The planet warmed a bit, allowing for longer growing seasons, and this phenomenon led to a push to clear and settle more lands. The stability of the period also led to population growth. European cities reached the tens to hundred thousands. Population growth had an impact on women’s roles in society, and forced them into greater domestic responsibilities.

The majority lived in small rural farming societies. Peasant women had many domestic responsibilities, including caring for children, preparing food, and tending livestock. During the harvest, women worked in the fields too. Women labored in their communities, tending their children, their farms, their homes, and their family businesses. Working women were the fabric that held communities together, yet farm records only recorded the output of the farmer, ignoring the labor of his wife. This calculation is lost to history and we can find only glimpses in court records regarding defiant women.

Cottage Industries, Public Domain

Cottage Industries, Public Domain

Women worked in vital cottage industries; brewing beer, baking, and weaving or manufacturing textiles. There were few jobs working women were excluded from when they needed to be done. Women and their families worked in unison for the success of the family. Women’s work was under compensated. Records show them earning around three-quarters what men earned.

Women were active in urban professions like milling grain, midwifery, laundering, spinning, and prostitution. Estimates vary depending on the location, but between one third and almost half of merchants in European urban areas were female.Widows in particular continued their husband's businesses and used their wealth to support wars.

Women's guilds were disappearing and even brothels were run mainly by male owners. In places like England regulations outlawed women’s participation in lucrative fields, thus keeping wealth in the hands of men. Weaving had long been an occupation of women, but larger looms and mills powered by animals or water made production more efficient and provided thicker cloth. Thus men took over these profitable businesses. Sons were trained as apprentices, blocking women from entering the profession.

Women’s labor was often multifaceted, menial, and constant. Men’s work by contrast was dangerous and exhausting. While men were singularly focused, women balanced many tasks.

An English poem made this point plain, “For man’s work ends at setting sun, Yet woman’s work is never done.” Wherever they labored, and no matter how hard women worked, they were paid less than men. Cecelia Penifader was an unmarried woman of the lower class whose family's prosperity allowed her to lead an independent life. She earned one-third less than men doing unskilled labor.

Women were active in urban professions like milling grain, midwifery, laundering, spinning, and prostitution. Estimates vary depending on the location, but between one third and almost half of merchants in European urban areas were female.Widows in particular continued their husband's businesses and used their wealth to support wars.

Women's guilds were disappearing and even brothels were run mainly by male owners. In places like England regulations outlawed women’s participation in lucrative fields, thus keeping wealth in the hands of men. Weaving had long been an occupation of women, but larger looms and mills powered by animals or water made production more efficient and provided thicker cloth. Thus men took over these profitable businesses. Sons were trained as apprentices, blocking women from entering the profession.

Women’s labor was often multifaceted, menial, and constant. Men’s work by contrast was dangerous and exhausting. While men were singularly focused, women balanced many tasks.

An English poem made this point plain, “For man’s work ends at setting sun, Yet woman’s work is never done.” Wherever they labored, and no matter how hard women worked, they were paid less than men. Cecelia Penifader was an unmarried woman of the lower class whose family's prosperity allowed her to lead an independent life. She earned one-third less than men doing unskilled labor.

Abbess Hilda, Wikimedia Commons

Abbess Hilda, Wikimedia Commons

Feudal England

In pre-feudal England, Anglo-Saxon society had well defined codes of laws, diverse trade, talented artisans, and connections to learning on the continent. The Anglo-Saxons were converted to Christianity in 597, by Augustine whose mission was commissioned by Pope Gregory and sponsored by Queen Brunhild in Francia.

The Celtic Christian Church maintained a number of practices that diverged from those of the Roman Catholic Church. In 644, the Abbess Hilda hosted a meeting at Whitby to reconcile the churches. The result was a unified church with Roman authority superseding the Celtic church. Hilda’s accomplishment left her venerated on statues, crosses, and in Stained Glass windows within churches. A homily to Hilda captured her spirit: “Bend your minds to holy learning that you may escape the fretting moth of littleness of mind that would wear out your souls. Train your hearts and lips to song which gives courage to the soul.”

By 900 the English were unquestioningly Christian, but pagan traditions were integrated in the daily lives of the working class. Eostre, for example, the Anglo-Saxon goddess of spring, merged into the Christian celebration of Easter, which is why flowers and eggs became part of celebrating the resurrection.

Women in England had more independence than their feudal counterparts. Germanic tribes had long held power in the hands of priestesses and queens. And in many ways they were seen as equal. This is exemplified by women’s wergild, or “blood price” paid if they were murdered, which was equal to men’s. Married women were expected to be active partners. Husbands brought property and gifts for their brides, rather than the brides bringing dowries.Women had the right to divorce, and could take with them half of the family wealth. They also had relative control over their finances, including the right to hold land in their own name and to defend themselves in court.

In pre-feudal England, Anglo-Saxon society had well defined codes of laws, diverse trade, talented artisans, and connections to learning on the continent. The Anglo-Saxons were converted to Christianity in 597, by Augustine whose mission was commissioned by Pope Gregory and sponsored by Queen Brunhild in Francia.

The Celtic Christian Church maintained a number of practices that diverged from those of the Roman Catholic Church. In 644, the Abbess Hilda hosted a meeting at Whitby to reconcile the churches. The result was a unified church with Roman authority superseding the Celtic church. Hilda’s accomplishment left her venerated on statues, crosses, and in Stained Glass windows within churches. A homily to Hilda captured her spirit: “Bend your minds to holy learning that you may escape the fretting moth of littleness of mind that would wear out your souls. Train your hearts and lips to song which gives courage to the soul.”

By 900 the English were unquestioningly Christian, but pagan traditions were integrated in the daily lives of the working class. Eostre, for example, the Anglo-Saxon goddess of spring, merged into the Christian celebration of Easter, which is why flowers and eggs became part of celebrating the resurrection.

Women in England had more independence than their feudal counterparts. Germanic tribes had long held power in the hands of priestesses and queens. And in many ways they were seen as equal. This is exemplified by women’s wergild, or “blood price” paid if they were murdered, which was equal to men’s. Married women were expected to be active partners. Husbands brought property and gifts for their brides, rather than the brides bringing dowries.Women had the right to divorce, and could take with them half of the family wealth. They also had relative control over their finances, including the right to hold land in their own name and to defend themselves in court.

Aethelflaed, Wikimedia Commons

Aethelflaed, Wikimedia Commons

But of course there were class differences here. Upper class women had more freedom. They received an education and managed their estates and finances. Nevertheless, women were barred from learning Latin, perhaps as a way of keeping them away from Church policy and administration.

Aethelflaed, Lady of the Mercians

The best example of a powerful elite woman is Aethelflaed, the daughter of Alfred the Great and one of the greatest military commanders in medieval England. She received an elaborate education for a girl of her time which included political and military training. She was eventually married to Aethelred of Mercia in a political alliance to unite the two kingdoms. The two held equal power. When he died, she took sole control of the kingdom of Mercia titling herself, “Lady of the Mercians” instead of queen.

When her younger brother, Edward, ascended to the throne, this brother-sister duo proved to be a formidable team. They fought against Danish Vikings who ruled nearby kingdoms, which is where her military strategy shone and earned her the respect of her peers. In 917, her brother distracted the Danes elsewhere while she took control of the heart of Danish fortifications by surprise. She also invested in fortresses, providing effective defenses against the Danes. Together Aethelflaed and her brother helped secure England from the Vikings.

In 918, at the peak of her power, Aethelflaed became sick and died. In many ways, her death was more significant to the lives of English people than that of her father or her brother. In a history written two centuries later, William of Malmesbury, described Aethelflaed as a “powerful member of king Edward’s party, the delight of her subjects, and the dread of his enemies. She was a spirited heroine who assisted her brother greatly with her advice. She was of equal service in building cities, and, whether through fortune or her own efforts, was a woman who protected men at home and intimidated them abroad.”

Aethelflaed, Lady of the Mercians

The best example of a powerful elite woman is Aethelflaed, the daughter of Alfred the Great and one of the greatest military commanders in medieval England. She received an elaborate education for a girl of her time which included political and military training. She was eventually married to Aethelred of Mercia in a political alliance to unite the two kingdoms. The two held equal power. When he died, she took sole control of the kingdom of Mercia titling herself, “Lady of the Mercians” instead of queen.

When her younger brother, Edward, ascended to the throne, this brother-sister duo proved to be a formidable team. They fought against Danish Vikings who ruled nearby kingdoms, which is where her military strategy shone and earned her the respect of her peers. In 917, her brother distracted the Danes elsewhere while she took control of the heart of Danish fortifications by surprise. She also invested in fortresses, providing effective defenses against the Danes. Together Aethelflaed and her brother helped secure England from the Vikings.

In 918, at the peak of her power, Aethelflaed became sick and died. In many ways, her death was more significant to the lives of English people than that of her father or her brother. In a history written two centuries later, William of Malmesbury, described Aethelflaed as a “powerful member of king Edward’s party, the delight of her subjects, and the dread of his enemies. She was a spirited heroine who assisted her brother greatly with her advice. She was of equal service in building cities, and, whether through fortune or her own efforts, was a woman who protected men at home and intimidated them abroad.”

Medieval Nuns, Public Domain

Medieval Nuns, Public Domain

Nunneries

In the early Middle Ages, nunneries provided opportunity and sanctuary for women of all classes generally outside the control of men. Women in these nunneries wielded enormous power and had lasting influence on scholarship of the time. Abbesses ruled over land, commanded armies, used their own coins, and even had their own courts. Abbesses heard confession, gave absolution and benediction, and some even went by the title “majesty.”

A woman from the aristocracy had two life paths: marry into financial security or become a nun. Being some of the few women with education and the resources for a dowry to the Church, nuns were recruited almost exclusively from the aristocracy. But certainly women of lower classes found themselves in convents as well. Women joined nunneries for piety, but there were also more practical reasons such as self-preservation. Medieval women in nunneries lived longer than their married sisters because of the high-risk in childbirth. Some women retired to nunneries in widowhood. Incoming nuns paid dowries of land or coin to the church. The standard of living was pretty high. Nuns worked in the Scriptorium, did domestic labor, and worked in Shops.

Convents provided intellectual opportunity for women denied to them elsewhere. Historian Rosalind Miles suggested marriage was the “enemy of any woman’s intellectual development” and Historian Joshua J. Mark stated, “The nunnery was a refuge of female intellectuals.” Nonconforming women, queer women, women who didn’t want to get married, and women who found the prospects of housekeeping and childrearing abhorrent, sought the covenant with enthusiasm. There is abundant correspondence from this time that highlights the daily lives of the nuns and shows that they did serious scholarship equal to that created by monks. The nun Lioba claimed she only put her books down to sleep. Hroswitha of Gandersheim wrote seven Latin plays in the 900s making her the world's first humanist for her abundant love of classical literature.

But by the 900s and 1000s, there was a major decline in the opportunities available to nuns. The church was overwhelmingly masculine in its power structure and became increasingly concerned about women and the time-honored-tradition of silencing them. Therefore, their public activity, status in church, and educational opportunities all declined in the mid and late Middle Ages. Double houses disappeared and nuns were forced to live in strict enclosures or in seclusion, completely separated from the male monks. Nuns were forced to rely on male priests for all sacraments, including confessions. The contributions of nuns to scholarship and learning declined. Phillippe of Navarre, writing in 1300, reflected the general sentiment about learned women: “One should not teach a woman letters or writing unless she is a nun, because a woman’s reading and writing leads to great evil.” Even in all-female covenants, all the opportunities for status and advancement available to male scholars were denied to them.

The increasing hostility toward the essence of womanhood saw a parallel rise in the adoration of the Virgin Mary. There was a thriving religious mysticism around her that the church saw as basically heresy. Although honoring the mother of Christ could be seen as a net win for Womankind. In reality, it only led to their subordination. Proponents felt that the essence of a woman was her innocence. To educate her would be to pollute her. The rationale to deprive women of an education deepened.

In the early Middle Ages, nunneries provided opportunity and sanctuary for women of all classes generally outside the control of men. Women in these nunneries wielded enormous power and had lasting influence on scholarship of the time. Abbesses ruled over land, commanded armies, used their own coins, and even had their own courts. Abbesses heard confession, gave absolution and benediction, and some even went by the title “majesty.”

A woman from the aristocracy had two life paths: marry into financial security or become a nun. Being some of the few women with education and the resources for a dowry to the Church, nuns were recruited almost exclusively from the aristocracy. But certainly women of lower classes found themselves in convents as well. Women joined nunneries for piety, but there were also more practical reasons such as self-preservation. Medieval women in nunneries lived longer than their married sisters because of the high-risk in childbirth. Some women retired to nunneries in widowhood. Incoming nuns paid dowries of land or coin to the church. The standard of living was pretty high. Nuns worked in the Scriptorium, did domestic labor, and worked in Shops.

Convents provided intellectual opportunity for women denied to them elsewhere. Historian Rosalind Miles suggested marriage was the “enemy of any woman’s intellectual development” and Historian Joshua J. Mark stated, “The nunnery was a refuge of female intellectuals.” Nonconforming women, queer women, women who didn’t want to get married, and women who found the prospects of housekeeping and childrearing abhorrent, sought the covenant with enthusiasm. There is abundant correspondence from this time that highlights the daily lives of the nuns and shows that they did serious scholarship equal to that created by monks. The nun Lioba claimed she only put her books down to sleep. Hroswitha of Gandersheim wrote seven Latin plays in the 900s making her the world's first humanist for her abundant love of classical literature.

But by the 900s and 1000s, there was a major decline in the opportunities available to nuns. The church was overwhelmingly masculine in its power structure and became increasingly concerned about women and the time-honored-tradition of silencing them. Therefore, their public activity, status in church, and educational opportunities all declined in the mid and late Middle Ages. Double houses disappeared and nuns were forced to live in strict enclosures or in seclusion, completely separated from the male monks. Nuns were forced to rely on male priests for all sacraments, including confessions. The contributions of nuns to scholarship and learning declined. Phillippe of Navarre, writing in 1300, reflected the general sentiment about learned women: “One should not teach a woman letters or writing unless she is a nun, because a woman’s reading and writing leads to great evil.” Even in all-female covenants, all the opportunities for status and advancement available to male scholars were denied to them.

The increasing hostility toward the essence of womanhood saw a parallel rise in the adoration of the Virgin Mary. There was a thriving religious mysticism around her that the church saw as basically heresy. Although honoring the mother of Christ could be seen as a net win for Womankind. In reality, it only led to their subordination. Proponents felt that the essence of a woman was her innocence. To educate her would be to pollute her. The rationale to deprive women of an education deepened.

Hroswitha of Gandersheim, Public Domain

Hroswitha of Gandersheim, Public Domain

Hroswitha Gandersheim

Hroswitha of Gandersheim was a canoness, working in the scriptorium to record documents in the 900s in Saxony. She was a noblewoman given to the nunnery as a child to acquire an education. The Gandersheim nunnery was the center of intellectual activity in Germany. Hroswitha became an Abbess and negotiated with the German Holy Roman Emperor to hold her own court and coin money. She was called the “strong voice of Gandersheim.”

She was the first female German historian to write a long poem about Otto I’s rule, documenting the struggle between paganism and Christianity. She wrote legends about the Saints and was the first known playwright of Christianity, having written six plays! She took a stand for women. The characters and plots in her plays countered the religious dogma that suggested women were corruptible and weak.

She said, “Sometimes I compose with great effort, again I destroyed what I had poorly written...[so that] the slight talent...given me by Heaven should not lie idle in the dark recesses of the mind and thus be destroyed by the rush of neglect.”

Hroswitha of Gandersheim was a canoness, working in the scriptorium to record documents in the 900s in Saxony. She was a noblewoman given to the nunnery as a child to acquire an education. The Gandersheim nunnery was the center of intellectual activity in Germany. Hroswitha became an Abbess and negotiated with the German Holy Roman Emperor to hold her own court and coin money. She was called the “strong voice of Gandersheim.”

She was the first female German historian to write a long poem about Otto I’s rule, documenting the struggle between paganism and Christianity. She wrote legends about the Saints and was the first known playwright of Christianity, having written six plays! She took a stand for women. The characters and plots in her plays countered the religious dogma that suggested women were corruptible and weak.

She said, “Sometimes I compose with great effort, again I destroyed what I had poorly written...[so that] the slight talent...given me by Heaven should not lie idle in the dark recesses of the mind and thus be destroyed by the rush of neglect.”

Hildegard of Bingen, Public Domain

Hildegard of Bingen, Public Domain

Hildegard of Bingen

Some medieval women were able to bypass misogyny and forge meaningful careers through the church. One of the more notable of these women was Hildegard de Bingen in Germany. She was a nun turned abbess, turned scholar, and Christian mystic. She was brilliant, and her research and written works touched many fields, from philosophy to musical composition, herbology to medieval literature, cosmology to medicine. In one of her books she identified almost 300 herbs. In another, she listed and suggested causes and remedies for 47 different illnesses. She was also interested in understanding the female reproductive system.

She had visions that she believed, as was common at the time, foretold the future. She, a woman, wrote interpretations of those visions. Popes, emperors, and kings accepted her writings.She regularly defied the patriarchal hierarchy of her profession and pushed boundaries for women. She was unanimously selected as abbess after growing the reputation and wealth of the convent for many years. She requested permission to build her own content away from patriarchal influences. She was denied but persisted and eventually founded the convent at Rupertsberg c. 1150 CE. There, Hildegard was free to explore her spiritual and intellectual ideas.

She corresponded with extraordinary women of her time, including Eleanor of Aquitaine. She lamented bad leadership and corrupt governments stating, “You neglect Justice….you permit her to lie prostrate on the earth.”

She fell in love with another nun whose wealthy family later separated them. Their letters reveal their painful heartbreak. Her love died from illness a short time later, leaving her stunned.

Her theology emphasized the feminine, and she thought women had just as important roles to play as men. She was widely popular and went on four speaking tours in defiance of prescriptions that women should stay silent in churches and in public.

Reflecting on her life, she claimed she was a “poor uneducated woman.” But she justified her work as her contribution to posterity. She wrote that she was asked to write, “for the benefit of mankind.”

Some medieval women were able to bypass misogyny and forge meaningful careers through the church. One of the more notable of these women was Hildegard de Bingen in Germany. She was a nun turned abbess, turned scholar, and Christian mystic. She was brilliant, and her research and written works touched many fields, from philosophy to musical composition, herbology to medieval literature, cosmology to medicine. In one of her books she identified almost 300 herbs. In another, she listed and suggested causes and remedies for 47 different illnesses. She was also interested in understanding the female reproductive system.

She had visions that she believed, as was common at the time, foretold the future. She, a woman, wrote interpretations of those visions. Popes, emperors, and kings accepted her writings.She regularly defied the patriarchal hierarchy of her profession and pushed boundaries for women. She was unanimously selected as abbess after growing the reputation and wealth of the convent for many years. She requested permission to build her own content away from patriarchal influences. She was denied but persisted and eventually founded the convent at Rupertsberg c. 1150 CE. There, Hildegard was free to explore her spiritual and intellectual ideas.

She corresponded with extraordinary women of her time, including Eleanor of Aquitaine. She lamented bad leadership and corrupt governments stating, “You neglect Justice….you permit her to lie prostrate on the earth.”

She fell in love with another nun whose wealthy family later separated them. Their letters reveal their painful heartbreak. Her love died from illness a short time later, leaving her stunned.

Her theology emphasized the feminine, and she thought women had just as important roles to play as men. She was widely popular and went on four speaking tours in defiance of prescriptions that women should stay silent in churches and in public.

Reflecting on her life, she claimed she was a “poor uneducated woman.” But she justified her work as her contribution to posterity. She wrote that she was asked to write, “for the benefit of mankind.”

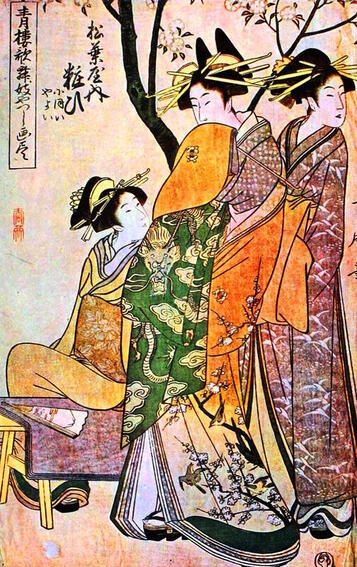

Japanese Women, Public Domain

Japanese Women, Public Domain

Feudal Japan

Across the world, a strikingly similar society existed on the islands of Japan. Japan adopted feudalism in 1192 with the rise of the first Shogun, Yoritomo. A shogun was an emperor by title but was more like a military ruler in practice. The shogun’s goal was to use his military prowess to prevent the return of civil war among the 260 daimyo, or feudal lords, each of whom had his own band of samurai soldiers.

Prior to the Shogunate, women in Japan had numerous privileges. They were allowed to own and inherit, unmarried women lived alone, and wife- beating was forbidden by law. Aristocrats were polygamous, but women lived with and were protected by their families. Their husbands would visit them. While this allowed women some independence, it also meant their spouse could easily desert them.

Before and after the rise of the shogunate, the idea of chivalry, which was important in Europe, did not exist. While women could influence affairs at court, they did so in a cloistered setting behind sliding screens. Unlike in Europe, women were given more sexual freedoms and would accept male visitors at night. Divorces were somewhat common and easy to obtain.

Aristocratic ladies lived lives of luxury, engaged in artistic pursuits, and had scandalous love affairs. Women writers were abundant in Japanese courts, and they developed a uniquely female style of writing as they were barred from learning Chinese, the official legal language in Japan. This was similar to the European custom that prohibited women from learning Latin. They wrote in everyday Japanese language in their diaries, novels, and poetry, making it widely readable and popular.

Across the world, a strikingly similar society existed on the islands of Japan. Japan adopted feudalism in 1192 with the rise of the first Shogun, Yoritomo. A shogun was an emperor by title but was more like a military ruler in practice. The shogun’s goal was to use his military prowess to prevent the return of civil war among the 260 daimyo, or feudal lords, each of whom had his own band of samurai soldiers.

Prior to the Shogunate, women in Japan had numerous privileges. They were allowed to own and inherit, unmarried women lived alone, and wife- beating was forbidden by law. Aristocrats were polygamous, but women lived with and were protected by their families. Their husbands would visit them. While this allowed women some independence, it also meant their spouse could easily desert them.

Before and after the rise of the shogunate, the idea of chivalry, which was important in Europe, did not exist. While women could influence affairs at court, they did so in a cloistered setting behind sliding screens. Unlike in Europe, women were given more sexual freedoms and would accept male visitors at night. Divorces were somewhat common and easy to obtain.

Aristocratic ladies lived lives of luxury, engaged in artistic pursuits, and had scandalous love affairs. Women writers were abundant in Japanese courts, and they developed a uniquely female style of writing as they were barred from learning Chinese, the official legal language in Japan. This was similar to the European custom that prohibited women from learning Latin. They wrote in everyday Japanese language in their diaries, novels, and poetry, making it widely readable and popular.

Lady Murasaki, Wikimedia Commons

Lady Murasaki, Wikimedia Commons

Japanese Writers

Showing how smart you were was important in Japanese courts, and people were regularly challenged to prove their intellect. Aristocrats would have poetry contests that men and women would enter. To misquote or be proven wrong was equivalent to being socially humiliated.

Women writers were not only present, but prominent in Japan. Lady Murasaki wrote the world's first novel, The Tale of the Genji. The story is as long as an epic and follows the journey of a fictional prince. In the story, she wrote: “Without the novel what should we know of how people lived in the past from the age of the Gods down to the present day? For history books...show us only one corner of life; whereas the diaries and romances contain...the most minute information about people’s private affairs.”

Sei Shonagon wrote a collection of her vivid observations at court known as Pillow Book. She divided what she saw into categories like, “Annoying Things” and “Things Which Distract in Moments of Boredom.” In a detached way, she ranked and classified the people, events, and objects around her.

Showing how smart you were was important in Japanese courts, and people were regularly challenged to prove their intellect. Aristocrats would have poetry contests that men and women would enter. To misquote or be proven wrong was equivalent to being socially humiliated.

Women writers were not only present, but prominent in Japan. Lady Murasaki wrote the world's first novel, The Tale of the Genji. The story is as long as an epic and follows the journey of a fictional prince. In the story, she wrote: “Without the novel what should we know of how people lived in the past from the age of the Gods down to the present day? For history books...show us only one corner of life; whereas the diaries and romances contain...the most minute information about people’s private affairs.”

Sei Shonagon wrote a collection of her vivid observations at court known as Pillow Book. She divided what she saw into categories like, “Annoying Things” and “Things Which Distract in Moments of Boredom.” In a detached way, she ranked and classified the people, events, and objects around her.

Izumi was Japan’s most illustrious female poet. Her writings were erotic and anguished, and they reinforced the impermanence of life. She was born around 975 and grew up in the imperial court, where her father was a mid-level government official. There, girls of her status earned an education in poetry and the arts. She was married to a provincial governor but began an affair with the son of the emperor. When the emperor died the scandal reached its climax and she was divorced from her husband and estranged from her family. She then started a relationship with the emperor's brother and was invited to the prince's compound, much to the distress of his principal wife. Her life was marred by scandal. Lady Murasaki, a contemporary, wrote “how interestingly she writes. What a disgraceful person she is.” The irony is that all of the men had many concubines, but relations with a handful of men in her lifetime made her disgraced. She wrote her most famous poem while she was just a teenager: “from utter darkness/I must embark upon an/even darker Road/oh distant moon, cast your light/from the rim of the mountains.”

Convents in Japan

The Japanese worshiped the Goddess Amaterasu, known as “the great divinity illuminating heaven.” She was the sun goddess of Shintoism in Japan, which morphed with Buddhism as it spread throughout Asia. Amaterasu was the daughter of Izanami and Izanagi from the Japanese creation story, who made her ruler of the sky.

Women were religious leaders known as shamans in Shintoism. They were called upon in crisis to provide wisdom. Women participated equally in religious celebrations, some of which were designed specifically for women, such as the Maid Star.

Like wealthy European women, upper-class women in Japan found Buddhist convents appealing. Nunneries offered women leadership opportunities, intellectual pursuits, and an alternative to marriage. But Buddhism also lessened women’s status with its teachings that emphasized female deceitfulness and dishonesty.

Convents in Japan

The Japanese worshiped the Goddess Amaterasu, known as “the great divinity illuminating heaven.” She was the sun goddess of Shintoism in Japan, which morphed with Buddhism as it spread throughout Asia. Amaterasu was the daughter of Izanami and Izanagi from the Japanese creation story, who made her ruler of the sky.

Women were religious leaders known as shamans in Shintoism. They were called upon in crisis to provide wisdom. Women participated equally in religious celebrations, some of which were designed specifically for women, such as the Maid Star.

Like wealthy European women, upper-class women in Japan found Buddhist convents appealing. Nunneries offered women leadership opportunities, intellectual pursuits, and an alternative to marriage. But Buddhism also lessened women’s status with its teachings that emphasized female deceitfulness and dishonesty.

Masa-ko, Wikimedia Commons

Masa-ko, Wikimedia Commons

Masa-ko

The Shogunate brought centuries of peace, which allowed for economic growth, commercialization, and urban development. Women's status declined a bit, more with the rise of the Shogun than the encroachment of Confucian ideas from China.

When Yoritomo died, his widow Masa-ko was left to hold the Shogunate together for her son Yoriye, but he was killed in battle. Go-Toba brought his armies against her. Grieving, Masa-ko rallied her army and crushed him. Masa-ko became known as “Mother Shogun” and her clan ruled as regents over the successive shoguns for a century and a half.

Women under the Shogun samurai culture were expected to be brave and loyal wives and daughters. They had very important duties at home providing food and supplies for their warrior husbands. Women managed all of the servants, finances, and business affairs. Because the father was so often absent, women’s ideas and opinions were honored. Women were also responsible for providing education for their children, emphasizing physical activity, strength, and samurai ideals.

Poor women worked alongside men relatively equally. They had some property and divorce rights but were not allowed to remarry. Peasant women had short hair, while aristocrats grew it long. Peasant farmers only had one wife. Aristocratic women married young.

The later samurai ideal of the obedient, submissive woman was accepted by the common people and peasant women lost much of their earlier independence.

But it was also not uncommon for women to fight. Women were trained in weaponry and carried a curved dagger called a “naginata”which they threw with remarkable precision. Women sometimes fought alongside their husbands in battle and played pivotal roles in encouraging troop loyalty. All samurai were expected to commit suicide if they were dishonored or lost in war, and women were no exception. Women would even use suicide as a form of protest against domestic abuse.

But the powerful Samurai women were eventually pushed into domestic servitude as the culture became more peaceful. The ideal samurai woman was obedient, controlled, and subservient. Women's access to property ownership and inheritance disappeared.

The Shogunate brought centuries of peace, which allowed for economic growth, commercialization, and urban development. Women's status declined a bit, more with the rise of the Shogun than the encroachment of Confucian ideas from China.

When Yoritomo died, his widow Masa-ko was left to hold the Shogunate together for her son Yoriye, but he was killed in battle. Go-Toba brought his armies against her. Grieving, Masa-ko rallied her army and crushed him. Masa-ko became known as “Mother Shogun” and her clan ruled as regents over the successive shoguns for a century and a half.

Women under the Shogun samurai culture were expected to be brave and loyal wives and daughters. They had very important duties at home providing food and supplies for their warrior husbands. Women managed all of the servants, finances, and business affairs. Because the father was so often absent, women’s ideas and opinions were honored. Women were also responsible for providing education for their children, emphasizing physical activity, strength, and samurai ideals.

Poor women worked alongside men relatively equally. They had some property and divorce rights but were not allowed to remarry. Peasant women had short hair, while aristocrats grew it long. Peasant farmers only had one wife. Aristocratic women married young.

The later samurai ideal of the obedient, submissive woman was accepted by the common people and peasant women lost much of their earlier independence.

But it was also not uncommon for women to fight. Women were trained in weaponry and carried a curved dagger called a “naginata”which they threw with remarkable precision. Women sometimes fought alongside their husbands in battle and played pivotal roles in encouraging troop loyalty. All samurai were expected to commit suicide if they were dishonored or lost in war, and women were no exception. Women would even use suicide as a form of protest against domestic abuse.

But the powerful Samurai women were eventually pushed into domestic servitude as the culture became more peaceful. The ideal samurai woman was obedient, controlled, and subservient. Women's access to property ownership and inheritance disappeared.

By the 1400s, Confucian ideas spread to Japan and solidified what the Shogun had begun. Women were subjected to the teachings of the “Three Obediences” emphasized in China. Women continued to be subordinate to their fathers, husbands, and sons.

Conclusion

As in Europe, the feudal period in Japan was a mixed bag for women, and the effect varied significantly by class. Women were leaders, thinkers, and workers who helped lay the groundwork for the rise in capitalism.

By the end of this period, so much remained in question. Did peace in Japan outweigh the decline in rights? Would women be able to circumvent the confines of cloistered life and have more public lives? Would women regain their rights lost? Was chivalry in Europe helpful to women?

Conclusion

As in Europe, the feudal period in Japan was a mixed bag for women, and the effect varied significantly by class. Women were leaders, thinkers, and workers who helped lay the groundwork for the rise in capitalism.

By the end of this period, so much remained in question. Did peace in Japan outweigh the decline in rights? Would women be able to circumvent the confines of cloistered life and have more public lives? Would women regain their rights lost? Was chivalry in Europe helpful to women?

Draw your own conclusions

|

Learn how to teach with inquiry.

Many of these lesson plans were sponsored in part by the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources Eastern Region Program, coordinated by Waynesburg University, the History and Social Studies Education Faculty at Plymouth State University, and the Patrons of the Remedial Herstory Project. |

|

OTHERS: Feudalism

Women in World History has two inquiries on women in England and Japan exploring primary material. Get the inquiry on England! Get the inquiry on Japan! |

Lesson Plans from Other Organizations

- This website, Women in World History has primary source based lesson plans on women's history in a whole range of topics. Some are free while others have a cost.

- The Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media has produced recommendations for teaching women's history with primary sources and provided a collection of sources for world history. Check them out!

- The Stanford History Education Group has a number of lesson plans about women in World History.

William Malmesbury: Chronicle of the Kings of England

William of Malmesbury was a 12th century monk and historian best known for writing chronicles on early English history. Below is an extract from pages 482-483 and discusses King Henry’s choice to pick his daughter, Matilda, as his heir and the reaction of the court.

In the twenty-seventh year of his reign, in the month of September, king Henry

came to England, bringing his daughter with him. But, at the ensuing Christmas,

convening a great number of the clergy and nobility at London, he gave the county of

Salop to his wife, the daughter of the earl of Louvain, whom he had married after the

death of Matilda. Distressed that this lady had no issue, and fearing lest she should be

perpetually childless, with well-founded anxiety, he turned his thoughts on a successor

to the kingdom. On which subject, having held much previous and long-continued

deliberation, he now at this council compelled all the nobility of England, as well as the

bishops and abbots, to make oath, that, if he should die without male issue, they would,

without delay or hesitation, accept his daughter Matilda, the late empress, as their

sovereign: observing, how prejudicially to the country fate had snatched away his son

William, to whom the kingdom by right had pertained: and, that his daughter still

survived, to whom alone the legitimate succession belonged, from her grandfather,

uncle, and father, who were kings; as well as from her maternal descent for many ages

back...

Thus all being bound by fealty and by oath, they, at that time, departed to their

homes; but after Pentecost, the king sent his daughter into Normandy, ordering her to

be betrothed, by the archbishop of Rouen, to the son of Fulco aforesaid, a youth of high

nobility and noted courage. Nor did he himself delay setting sail for Normandy, for the

purpose of uniting them in wedlock. Which being completed, all declared prophetically,

as it were, that, after his death, they would break their plighted oath. I have frequently

heard Roger, bishop of Salisbury, say, that he was freed from the oath he had taken to

the empress: for that he had sworn conditionally, that the king should not marry his

daughter to any one out of the kingdom without his consent, or that of the rest of the

nobility: that none of them advised the match, or indeed knew of it, except Robert, earl

of Gloucester, and Brian Fitzcount, and the bishop of Louviers. Nor do I relate this

merely because I believe the assertion of a man who knew how to accommodate himself

to every varying time, as fortune ordered it; but, as an historian of veracity, I write the

general belief of the people.

Malmesbury, W. and J.A. Giles. “William of Malmesbury’s Chronicle of the Kings of England.” Gutenberg.org [online] Available at https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/50778/pg50778-images.html#Page_531.

Questions:

In the twenty-seventh year of his reign, in the month of September, king Henry

came to England, bringing his daughter with him. But, at the ensuing Christmas,

convening a great number of the clergy and nobility at London, he gave the county of

Salop to his wife, the daughter of the earl of Louvain, whom he had married after the

death of Matilda. Distressed that this lady had no issue, and fearing lest she should be

perpetually childless, with well-founded anxiety, he turned his thoughts on a successor

to the kingdom. On which subject, having held much previous and long-continued

deliberation, he now at this council compelled all the nobility of England, as well as the

bishops and abbots, to make oath, that, if he should die without male issue, they would,

without delay or hesitation, accept his daughter Matilda, the late empress, as their

sovereign: observing, how prejudicially to the country fate had snatched away his son

William, to whom the kingdom by right had pertained: and, that his daughter still

survived, to whom alone the legitimate succession belonged, from her grandfather,

uncle, and father, who were kings; as well as from her maternal descent for many ages

back...

Thus all being bound by fealty and by oath, they, at that time, departed to their

homes; but after Pentecost, the king sent his daughter into Normandy, ordering her to

be betrothed, by the archbishop of Rouen, to the son of Fulco aforesaid, a youth of high

nobility and noted courage. Nor did he himself delay setting sail for Normandy, for the

purpose of uniting them in wedlock. Which being completed, all declared prophetically,

as it were, that, after his death, they would break their plighted oath. I have frequently

heard Roger, bishop of Salisbury, say, that he was freed from the oath he had taken to

the empress: for that he had sworn conditionally, that the king should not marry his

daughter to any one out of the kingdom without his consent, or that of the rest of the

nobility: that none of them advised the match, or indeed knew of it, except Robert, earl

of Gloucester, and Brian Fitzcount, and the bishop of Louviers. Nor do I relate this

merely because I believe the assertion of a man who knew how to accommodate himself

to every varying time, as fortune ordered it; but, as an historian of veracity, I write the

general belief of the people.

Malmesbury, W. and J.A. Giles. “William of Malmesbury’s Chronicle of the Kings of England.” Gutenberg.org [online] Available at https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/50778/pg50778-images.html#Page_531.

Questions:

- What can we learn from this source about the public opinion of Matilda?

Queen Mary 1: Act Concerning the Regal Power

An act declared by Queen Mary I of England, which made it legal for women to have sole ruling power as

the Queen. Mary began her rule in 1553 after the death of her brother, Edward VI, left no male heir to the

English throne. Female rule was considered with suspicion, and Mary’s marriage also caused concern.

Shortly after her accession, she married Prince Philip of Spain (later Philip II). Women were considered

submissive to their husbands; did that mean the Queen would be submissive to her husband in politics,

too? The English government and people became concerned that Philip would seize power, and therefore

Mary was moved to declare her intention to retain the English throne for herself. In this, Mary declares

her right to rule as a woman, and her unwillingness to relinquish her crown to a man, even her husband.

[B]e it declared and enacted by the authority of this present parliament that the law of

this realm is and ever hath been, and ought to be understood, that the kingly or regal office of

the realm, and all dignities [etc.] ... thereunto annexed, united, or belonging, being invested

either in male or female, are and be and ought to be as fully, wholly, absolutely, and entirely

deemed, judged, accepted, invested, and taken in the one as in the other; so that what or

whensoever statute or law doth limit and appoint that the king of this realm may or shall have,

execute, and do anything as king, or doth give any profit or commodity to the king, or doth limit

or appoint any pains or punishment for the correction of offenders or transgressors against the

regality and dignity of the king or of the crown, the same the queen ... may by the same authority

and power likewise have, exercise, execute, punish, correct, and do, to all intents, constructions,

and purposes, without doubt, ambiguity, scruple, or question — any custom, use, or scruple, or

any other thing whatsoever to be made to the contrary notwithstanding.

Queen Mary I, Act Concerning the Regal Power (1554) § (n.d.). https://constitution.org/1-

History/sech/sech_078.htm.

Questions:

the Queen. Mary began her rule in 1553 after the death of her brother, Edward VI, left no male heir to the

English throne. Female rule was considered with suspicion, and Mary’s marriage also caused concern.

Shortly after her accession, she married Prince Philip of Spain (later Philip II). Women were considered

submissive to their husbands; did that mean the Queen would be submissive to her husband in politics,

too? The English government and people became concerned that Philip would seize power, and therefore

Mary was moved to declare her intention to retain the English throne for herself. In this, Mary declares

her right to rule as a woman, and her unwillingness to relinquish her crown to a man, even her husband.

[B]e it declared and enacted by the authority of this present parliament that the law of

this realm is and ever hath been, and ought to be understood, that the kingly or regal office of

the realm, and all dignities [etc.] ... thereunto annexed, united, or belonging, being invested

either in male or female, are and be and ought to be as fully, wholly, absolutely, and entirely

deemed, judged, accepted, invested, and taken in the one as in the other; so that what or

whensoever statute or law doth limit and appoint that the king of this realm may or shall have,

execute, and do anything as king, or doth give any profit or commodity to the king, or doth limit

or appoint any pains or punishment for the correction of offenders or transgressors against the

regality and dignity of the king or of the crown, the same the queen ... may by the same authority

and power likewise have, exercise, execute, punish, correct, and do, to all intents, constructions,

and purposes, without doubt, ambiguity, scruple, or question — any custom, use, or scruple, or

any other thing whatsoever to be made to the contrary notwithstanding.

Queen Mary I, Act Concerning the Regal Power (1554) § (n.d.). https://constitution.org/1-

History/sech/sech_078.htm.

Questions:

- What power did this act give Queen Mary I?

- How did this act work against ideas of the time regarding a woman’s role in marriage?

Henry VIII: Letter to Anne Boleyn after she returned to Hever Castle Kent (mAY 1527)

“...I have put myself into great agony...beseeching you earnestly to let me know expressly your whole mind as to the love between us two. It is absolutely necessary for me to obtain this answer, having been for above a whole year stricken with the dart of love, and not yet sure whether I shall fail of finding a place in your heart and affection, which last point has prevented me for some time past from calling you my mistress; because, if you only love me with an ordinary love, that name is not suitable for you, because it denotes a singular love, which is far from common. But if you please to do the office of a true loyal mistress and friend, and to give up yourself body and heart to me, who will be, and have been, your most loyal servant, (if your rigour does not forbid me) I promise you that not only the name shall be given you, but also that I will take you for my only mistress, casting off all others besides you out of my thoughts and affections, and serve you only. I beseech you to give an entire answer to this my rude letter, that I may know on what and how far I may depend. And if it does not please you to answer me in writing, appoint some place where I may have it by word of mouth, and I will go thither with all my heart. No more, for fear of tiring you. Written by the hand of him who would willingly remain yours, H. R’

“Love Letter 1”, The Anne Boleyn Files. Available: https://www.theanneboleynfiles.com/resources/anne-boleyn-words/henry-viiis-love- letters-to-anne-boleyn/love-letter-1/

Questions:

“Love Letter 1”, The Anne Boleyn Files. Available: https://www.theanneboleynfiles.com/resources/anne-boleyn-words/henry-viiis-love- letters-to-anne-boleyn/love-letter-1/

Questions:

- What is significant about the context of this letter?

- What is King Henry VIII asking Anne to agree to?

- What does he promise her in return?

- What does this suggest about their relationship at the time?

Henry VIII: Letter to Anne Boleyn (August 1528)

‘Mine own sweetheart...I ensure you methinketh the time longer since our departing now last, than I was wont to do a whole fortnight. I think your kindness and my fervency of love auseth it ; for, otherwise, I would not have thought it possible that for so little a while it should have grieved me. But now that I am coming towards you, methinketh my pains behalf removed ; and also I am right well comforted in so much that my book maketh substantially for my matter; in looking whereof I have spent above four hours this day, which causeth me now to write the shorter letter to you at this time, because of some pain in my head; wishing myself (especially an evening) in my sweethearts arms, whose pretty dukkys (breasts) I trust shortly to kiss. Written by the hand of him that was, is, and shall be yours by his own will, H.R.’

Rebecca Larson, ‘Love Letters from Henry VIII to Anne Boleyn’. Tudors Dynasty. Available: https://tudorsdynasty.com/love-letter-henry-anne/

Questions:

1. How long after SOURCE A was this letter written?

2. What might this letter suggest has changed about the nature of their relationship since then?

Rebecca Larson, ‘Love Letters from Henry VIII to Anne Boleyn’. Tudors Dynasty. Available: https://tudorsdynasty.com/love-letter-henry-anne/

Questions:

1. How long after SOURCE A was this letter written?

2. What might this letter suggest has changed about the nature of their relationship since then?

The Spanish Chronicle: (30th April 1586)

Description of the alleged torture of Mark Smeaton, one of those accused of being Anne’s lover.

[Cromwell] called two stout young fellows of his, and asked for a rope and a cudgel, and ordered them to put the rope, which was full of knots, round Mark’s head, and twisted it with the cudgel until Mark cried out, “Sir Secretary, no more, I will tell the truth, ” and then he said, “The Queen gave me the money. ” “Ah, Mark, ” said Cromwell, “I know the Queen gave you a hundred nobles, but what you have bought has cost over a thousand, and that is a great gift even for a Queen to a servant of low degree such as you. If you do not tell me all the truth I swear by the life of the King I will torture you till you do. ” Mark replied, “Sir, I tell you truly that she gave it to me.” Then Cromwell ordered him a few more twists of the cord, and poor Mark, overcome by the torment, cried out, “No more, Sir, I will tell you everything that has happened.” And then he confessed all, and told everything as we have related it, and how it came to pass.”

‘Mark Smeaton with the Marmalade in the Cupboard’, The Anne Boleyn Files. Available:

https://www.theanneboleynfiles.com/mark-smeaton-with-the-marmalade-in-the- cupboard/

Questions:

[Cromwell] called two stout young fellows of his, and asked for a rope and a cudgel, and ordered them to put the rope, which was full of knots, round Mark’s head, and twisted it with the cudgel until Mark cried out, “Sir Secretary, no more, I will tell the truth, ” and then he said, “The Queen gave me the money. ” “Ah, Mark, ” said Cromwell, “I know the Queen gave you a hundred nobles, but what you have bought has cost over a thousand, and that is a great gift even for a Queen to a servant of low degree such as you. If you do not tell me all the truth I swear by the life of the King I will torture you till you do. ” Mark replied, “Sir, I tell you truly that she gave it to me.” Then Cromwell ordered him a few more twists of the cord, and poor Mark, overcome by the torment, cried out, “No more, Sir, I will tell you everything that has happened.” And then he confessed all, and told everything as we have related it, and how it came to pass.”

‘Mark Smeaton with the Marmalade in the Cupboard’, The Anne Boleyn Files. Available:

https://www.theanneboleynfiles.com/mark-smeaton-with-the-marmalade-in-the- cupboard/

Questions:

- Is evidence given under torture reliable? Explain.

- What does this suggest happened to Mark upon his arrest?

- What does Mark confess to?

- Do you think he committed adultery with the Queen? Why?

Anne Boleyn: Alleged Statement to Henry Norris

An alleged statement made by Queen Anne Boleyn to Henry Norris, one of the men later accused of being her lover (c.2nd May 1536). p151

‘You look for dead man’s shoes for if aught should come to the King but good, you would look to have me.’

Alison Weir (2010). The Lady in the Tower: The Fall of Anne Boleyn. London: Vintage, p151.

Questions:

1. Why would this statement have been considered shocking and treasonous at the time?

2. Should this be considered proof that Henry Noris and Anne were lovers?

‘You look for dead man’s shoes for if aught should come to the King but good, you would look to have me.’

Alison Weir (2010). The Lady in the Tower: The Fall of Anne Boleyn. London: Vintage, p151.

Questions:

1. Why would this statement have been considered shocking and treasonous at the time?

2. Should this be considered proof that Henry Noris and Anne were lovers?

Thomas Cramner: Letter to Henry VIII

“If what has been reported openly of the Queen be true, it is only to her dishonour, not yours. My mind is clean amazed, for I never had better opinion of a woman, but I think your Highness would not have gone so far if she had not been culpable. Next unto your Grace, I was most bound unto her of all creatures living, which her kindness bindeth me unto, and therefore beg that I may with your Grace’s favour wish and pray or her, that she may declare herself inculpable and innocent.’

Alison Weir (2010). The Lady in the Tower: The Fall of Anne Boleyn. London: Vintage, p187-8 Source

Questions:

1. Who wrote this letter and why is this significant?

2. What sentiments does the author express about the charges laid against the Queen?

3. Does the author think Queen Anne Boleyn is guilty?

Alison Weir (2010). The Lady in the Tower: The Fall of Anne Boleyn. London: Vintage, p187-8 Source

Questions:

1. Who wrote this letter and why is this significant?

2. What sentiments does the author express about the charges laid against the Queen?

3. Does the author think Queen Anne Boleyn is guilty?

The Grandy Jury Of Middlesex: The Middlesex Indictment against Queen Anne Boleyn

“Indictment found at Westminster on Wednesday next after three weeks of Easter, 28 Hen. VIII... queen Anne has been the wife of Henry VIII. for three years and more, she, despising her marriage, and entertaining malice against the King, and following daily her frail and carnal lust, did falsely and traitorously procure by base conversations and kisses, touchings, gifts, and other infamous incitations, divers of the King’s daily and familiar servants to be her adulterers and concubines, so that several of the King’s servants yielded to her vile provocations; viz., on 6th Oct. 25 Hen. VIII., at Westminster, and divers days before and after, she procured, by sweet words, kisses, touches, and otherwise, Hen. Noreys, of Westminster, gentle man of the privy chamber, to violate her, by reason whereof he did so at Westminster on the 12th Oct. 25 Hen. VIII.; and they had illicit intercourse at various other times, both before and after, sometimes by his procurement, and sometimes by that of the Queen.

Also the Queen, 2 Nov. 27 Hen. VIII. and several times before and after, at Westminster, procured and incited her own natural brother, Geo. Boleyn, lord Rocheford, gentleman of the privy chamber, to violate her, alluring him with her tongue in the said George’s mouth, and the said George’s tongue in hers, and also with kisses, presents, and jewels; whereby he, despising the commands of God, and all human laws, 5 Nov. 27 Hen. VIII., violated and carnally knew the said Queen, his own sister, at Westminster; which he also did on divers other days before and after at the same place, sometimes by his own procurement and sometimes by the Queen’s.

Also the Queen, 3 Dec. 25 Hen. VIII., and divers days before and after, at Westminster, procured one Will. Bryerton, late of Westminster, gentleman of the privy chamber, to violate her, whereby he did so on 8 Dec. 25 Hen. VIII., at Hampton Court, in the parish of Lytel Hampton, and on several other days before and after, sometimes by his own procurement and sometimes by the Queen’s.

Also the Queen, 8 May 26 Hen. VIII., and at other times before and since, procured Sir Fras. Weston, of Westminster, gentleman of the privy chamber, &c., whereby he did so on the 20 May, &c. Also the Queen, 12 April 26 Hen. VIII., and divers days before and since, at Westminster, procured Mark Smeton, groom of the privy chamber, to violate her, whereby he did so at Westminster, 26 April 27 Hen. VIII. Moreover, the said lord Rocheford, Norreys, Bryerton, Weston, and Smeton, being thus inflamed with carnal love of the Queen, and having become very jealous of each other, gave her secret gifts and pledges while carrying on this illicit intercourse; and the Queen, on her part, could not endure any of them to converse with any other woman, without showing great displeasure; and on the 27 Nov. 27 Hen. VIII., and other days before and after, at Westminster, she gave them great gifts to encourage them in their crimes. And further the said Queen and these other traitors, 31 Oct. 27 Hen. VIII., at Westminster, conspired the death and destruction of the King, the Queen often saying she would marry one of them as soon as the King died, and affirming that she would never love the King in her heart. And the King having a short time since become aware of the said abominable crimes and treasons against himself, took such inward displeasure and heaviness, especially from his said Queen’s malice and adultery, that certain harms and perils have befallen his royal body.

‘10 May 1536 - The Middlesex Indictment’, The Anne Boleyn Files. Available: https://www.theanneboleynfiles.com/10-may-1536-the-middlesex-indictment/.

Questions:

Also the Queen, 2 Nov. 27 Hen. VIII. and several times before and after, at Westminster, procured and incited her own natural brother, Geo. Boleyn, lord Rocheford, gentleman of the privy chamber, to violate her, alluring him with her tongue in the said George’s mouth, and the said George’s tongue in hers, and also with kisses, presents, and jewels; whereby he, despising the commands of God, and all human laws, 5 Nov. 27 Hen. VIII., violated and carnally knew the said Queen, his own sister, at Westminster; which he also did on divers other days before and after at the same place, sometimes by his own procurement and sometimes by the Queen’s.

Also the Queen, 3 Dec. 25 Hen. VIII., and divers days before and after, at Westminster, procured one Will. Bryerton, late of Westminster, gentleman of the privy chamber, to violate her, whereby he did so on 8 Dec. 25 Hen. VIII., at Hampton Court, in the parish of Lytel Hampton, and on several other days before and after, sometimes by his own procurement and sometimes by the Queen’s.

Also the Queen, 8 May 26 Hen. VIII., and at other times before and since, procured Sir Fras. Weston, of Westminster, gentleman of the privy chamber, &c., whereby he did so on the 20 May, &c. Also the Queen, 12 April 26 Hen. VIII., and divers days before and since, at Westminster, procured Mark Smeton, groom of the privy chamber, to violate her, whereby he did so at Westminster, 26 April 27 Hen. VIII. Moreover, the said lord Rocheford, Norreys, Bryerton, Weston, and Smeton, being thus inflamed with carnal love of the Queen, and having become very jealous of each other, gave her secret gifts and pledges while carrying on this illicit intercourse; and the Queen, on her part, could not endure any of them to converse with any other woman, without showing great displeasure; and on the 27 Nov. 27 Hen. VIII., and other days before and after, at Westminster, she gave them great gifts to encourage them in their crimes. And further the said Queen and these other traitors, 31 Oct. 27 Hen. VIII., at Westminster, conspired the death and destruction of the King, the Queen often saying she would marry one of them as soon as the King died, and affirming that she would never love the King in her heart. And the King having a short time since become aware of the said abominable crimes and treasons against himself, took such inward displeasure and heaviness, especially from his said Queen’s malice and adultery, that certain harms and perils have befallen his royal body.

‘10 May 1536 - The Middlesex Indictment’, The Anne Boleyn Files. Available: https://www.theanneboleynfiles.com/10-may-1536-the-middlesex-indictment/.

Questions:

- What is an indictment?

- What crimes is the Queen accused of within this indictment?

- How many men is she accused of having adultery with?

- What effect would these charges have had on the public and her jurors at the time?

- What impression does this give on Anne?

- Does the indictment give evidence to support its claims?

Anne Boleyn: Speech At Her Trial For Adultery And Treason

My lords, I will not say your sentence is unjust...I am willing to believe that you have sufficient reasons for what you have done; but then they must be other than those which have been produced in court, for I am clear of all the offences which you then laid to my charge. I have ever been a faithful wife to the King, though I do not say I have always shown him that humility which his goodness to me, and the honours to which he raised me, merited. I confess I have had jealous fancies and suspicions of him, which I had not discretion enough, and wisdom, to conceal at all times. But God knows, and is my witness, that I have not sinned against him in any other way....As for my brother and those others who are unjustly condemned, I would willingly suffer many deaths to deliver them, but since I see it so pleases the King, I shall willingly accompany them in death, with this assurance, that I shall lead an endless life with them in peace and joy, where I will pray to God for the King and for you, my lords.’

Alison Weir (2010). The Lady in the Tower: The Fall of Anne Boleyn. London: Vintage, p279. Document

Questions:

1. What does Anne confess to in this speech?

2. Why would this have still been perceived as negative behaviour for a queen?

Alison Weir (2010). The Lady in the Tower: The Fall of Anne Boleyn. London: Vintage, p279. Document

Questions:

1. What does Anne confess to in this speech?

2. Why would this have still been perceived as negative behaviour for a queen?

Eustace Chapuyus: Relaying Intel From Queen Anne’s Lady-In-Waiting Detailing Her Last Confession

‘The lady who had charge of her has sent to tell me in great secrecy, that the Concubine, before and after receiving the Sacrament, affirmed to her, on the damnation of her soul, that she had never offended with her body against the King.’

Alison Weir (2010). The Lady in the Tower: The Fall of Anne Boleyn. London: Vintage, p320. Source

Questions:

1. Who wrote this and why would that be significant?

2. What words are particularly significant in this source?

3. What makes this particularly compelling evidence for Anne’s innocence given the context in which it was given?

Alison Weir (2010). The Lady in the Tower: The Fall of Anne Boleyn. London: Vintage, p320. Source

Questions:

1. Who wrote this and why would that be significant?

2. What words are particularly significant in this source?

3. What makes this particularly compelling evidence for Anne’s innocence given the context in which it was given?

THéodore Godefroy: Le Ceremonial Français

The following is an extract from ‘Le Ceremonial Français... a manuscript for Théodore Godefroy. Godefroy was a 16th century French scholar. In the document, Charles IX highlights Catherine’s political status. Charles removed his hat as he approached his mother as a sign of respect that was usually only accorded to kings.

[T]he queen [mother] rose and went toward the king on his royal seat to declare that she

remitted into his majesty's hands the administration of his realm which had been given by the

estates assembled at Orleans. And as a sign of this, the said lady went toward the said lord and

he descended three or four steps from his throne to come before her with his hat in his hand.

And he made a great reverence to this woman and kissed her, and the king said to her that she

would govern and command more than ever.

Crawford. K (2000) ‘Catherine de Medicis and the Performance of Political Motherhood’ In The Sixteenth Century Journal, Vol. 31, No. 2. pp.643-673. Kirksville: Truman State University.

Questions:

[T]he queen [mother] rose and went toward the king on his royal seat to declare that she

remitted into his majesty's hands the administration of his realm which had been given by the

estates assembled at Orleans. And as a sign of this, the said lady went toward the said lord and

he descended three or four steps from his throne to come before her with his hat in his hand.

And he made a great reverence to this woman and kissed her, and the king said to her that she

would govern and command more than ever.

Crawford. K (2000) ‘Catherine de Medicis and the Performance of Political Motherhood’ In The Sixteenth Century Journal, Vol. 31, No. 2. pp.643-673. Kirksville: Truman State University.

Questions:

- What kind of source is this?

- When was it written?

- What does this document tell us about Catherine’s power in the court and her relationship with Charles IX?

Michel de L’Hospital: Oeuvres Completes

Michel de L’Hospital was a catholic lawyer who worked for the French government in the 16th century. Catherine de Medici named him chancellor in 1560 hoping he might reconcile the conflict between Catholics and Protestants. In this short extract he refers to the reign of her second son, Charles IX, and emphasizes Catherine’s special status and power.

He is in his majority, and I do not hesitate to say in the presence of his majesty ... that he

strength, except towards the queen his mother, to whom he reserves the power to command.

Michel de L’Hospital, Oeuvres Completes, 16th century. Translation by Dufey. P. J. S (1824) Paris.

Questions:

He is in his majority, and I do not hesitate to say in the presence of his majesty ... that he

strength, except towards the queen his mother, to whom he reserves the power to command.

Michel de L’Hospital, Oeuvres Completes, 16th century. Translation by Dufey. P. J. S (1824) Paris.

Questions:

- What kind of source is this?

- When was it painted?

- Why might the young King reserve power for his mother?

Pierre de l’Estoile: Excerpt from His Journal

The following extract is a verse transcribed in the 1575 journal of Pierre de l’Estoile. The verses refer to Catherine’s extreme passion for power. Note the violent language used.

You marvel how a woman, after annulling the Salic law, boldly presses Gallic necks to her authority. Alas! She unmans cocks, tearing off their crests and testicles; a virago holds sway over the French. An unbridled woman dines on [men], and as she devours this food, she smacks her lips and says, “Thus I castrate Gallic courage, thus I unman the French, thus I subdue them!”

Murphy. S (1992) ‘Catherine, Cybele and Ronsard’s Witnesses’ In Long. K (Ed) High Anxiety: Masculinity in Crisis in Early Modern France. Kirksville: Truman State University.

Questions:

You marvel how a woman, after annulling the Salic law, boldly presses Gallic necks to her authority. Alas! She unmans cocks, tearing off their crests and testicles; a virago holds sway over the French. An unbridled woman dines on [men], and as she devours this food, she smacks her lips and says, “Thus I castrate Gallic courage, thus I unman the French, thus I subdue them!”

Murphy. S (1992) ‘Catherine, Cybele and Ronsard’s Witnesses’ In Long. K (Ed) High Anxiety: Masculinity in Crisis in Early Modern France. Kirksville: Truman State University.

Questions:

- What kind of source is this?

- When was it written?

- How did this primary source interpret Catherine’s power?

Marguerite De Valois: Memoirs

Marguerite de Valois was the daughter of Catherine de Medici and the sister of the French King Charles IX. In this letter she describes the Massacre of St. Bartholomew, which took place during the celebrations of her wedding to King Henry of Navarre, the protestant. She states her knowledge of the events and any role her mother may have played in it.

King Charles, a prince of great prudence... went to the apartments of the Queen his mother, and sending for... all the Princes and Catholic officers, the "Massacre of St. Bartholomew" was that night resolved upon.

Immediately every hand was at work; chains were drawn across the streets, the alarm- bells were sounded, and every man repaired to his post, according to the orders he had received, whether it was to attack the Admiral's quarters, or those of the other Huguenots [Protestants].

I was perfectly ignorant of what was going forward. I observed everyone to be in motion: the Huguenots, driven to despair by the attack upon the Admiral's life, and the Guises, fearing they should not have justice done them, whispering all they met in the ear.

The Huguenots were suspicious of me because I was a Catholic, and the Catholics because I was married to the King of Navarre, who was a Huguenot. This being the case, no one spoke a syllable of the matter to me.