20. Post-War Women

|

After World War II, women returned home, or at least that’s what society hoped. The reality was a bit more complicated than that. The 1950s is remembered as the good old days, when gender roles were clear, families were united, and everything was “normal.” But to what extent was that true? And at whose expense was this normalcy achieved?

|

Give Up the Blues:

This was the Cold War, a conflict with the USSR that didn’t result in a direct hot war between those two nations. Society shifted as a result of the political conflict and government propaganda that sought to show the superiority of US capitalism and democracy over Soviet communism and authoritarianism. Americans highlighted the perceived superiority of the “nuclear family” of two parents and two kids living together in a home in contrast to families of Russia and the conditions in which women lived there. Propaganda depicted Russian women continuing to labor long hours in factories while their children were placed in horrible day care centers. American women were portrayed in a positive light, with feminine hairdos and delicate dresses, taking care of their homes and families, and enjoying the benefits of capitalism, democracy, and the freedom to be home with their children.

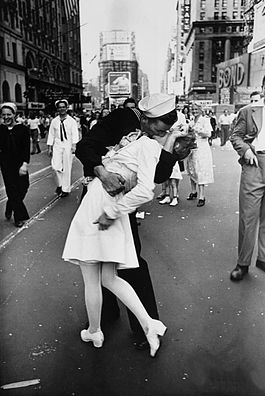

Propaganda, however, isn’t reality. In reality many women had to be pushed off of the factory floor and away from good paying jobs. Women who had worked in the defense industry, the “Rosie the Riveters” during WWII, were expected to return to their lives before the war. Women were told to “Give up the Blues” the jumpsuits they wore in industrial factories, to accept lower paying jobs, find a spouse, and settle down. For many this was an appealing alternative to the anxiety and stress of the war years. Goods that had been rationed or disappeared during war were available again and things seemed “normal.” But were they?

Class and racial differences impacted women's choices after the war. Poor women needed to keep their jobs and continued to battle sexism and racism. Other women loved serving in the military and stayed on through the Cold War. They battled sexism in the military and worked their way up in rank. Most white, middle class women accepted the fact that their wartime jobs were temporary and that their training and education was to help them raise a good family, not have a career. Most women, regardless of class and race, valued their domestic roles but felt miserable being “just a wife” because they were treated terribly by both their spouse and society.

During this era, most married women tied the knot at a young age and started families immediately. Large families were typical, with many couples having three or more children. The media promoted the image of the "happy homemaker," encouraging women to stay at home if possible. Those who chose to work without financial necessity were often criticized for prioritizing themselves over family needs or their husbands were shamed for not being strong enough providers. The pressure to engage in sexual activity within marriage also increased, leading to nearly three decades of childbearing potential for young wives without effective contraceptives.

The prevailing stereotype was that women went to college primarily to find a husband, earning them the mockingly referred to "M.R.S." degree. Although women had other aspirations, the culture and media emphasized the importance of marriage over education and employment. Being single and pregnant was deemed completely unacceptable, leading to many quick marriages or girls being shamed and isolated during their pregnancies–often placed in unwed mothers’ homes and forced to give up their child for adoption. Despite societal pressures to remain virgins, premarital sex was happening, driving the need for reliable female-controlled contraceptives.

This was the Cold War, a conflict with the USSR that didn’t result in a direct hot war between those two nations. Society shifted as a result of the political conflict and government propaganda that sought to show the superiority of US capitalism and democracy over Soviet communism and authoritarianism. Americans highlighted the perceived superiority of the “nuclear family” of two parents and two kids living together in a home in contrast to families of Russia and the conditions in which women lived there. Propaganda depicted Russian women continuing to labor long hours in factories while their children were placed in horrible day care centers. American women were portrayed in a positive light, with feminine hairdos and delicate dresses, taking care of their homes and families, and enjoying the benefits of capitalism, democracy, and the freedom to be home with their children.

Propaganda, however, isn’t reality. In reality many women had to be pushed off of the factory floor and away from good paying jobs. Women who had worked in the defense industry, the “Rosie the Riveters” during WWII, were expected to return to their lives before the war. Women were told to “Give up the Blues” the jumpsuits they wore in industrial factories, to accept lower paying jobs, find a spouse, and settle down. For many this was an appealing alternative to the anxiety and stress of the war years. Goods that had been rationed or disappeared during war were available again and things seemed “normal.” But were they?

Class and racial differences impacted women's choices after the war. Poor women needed to keep their jobs and continued to battle sexism and racism. Other women loved serving in the military and stayed on through the Cold War. They battled sexism in the military and worked their way up in rank. Most white, middle class women accepted the fact that their wartime jobs were temporary and that their training and education was to help them raise a good family, not have a career. Most women, regardless of class and race, valued their domestic roles but felt miserable being “just a wife” because they were treated terribly by both their spouse and society.

During this era, most married women tied the knot at a young age and started families immediately. Large families were typical, with many couples having three or more children. The media promoted the image of the "happy homemaker," encouraging women to stay at home if possible. Those who chose to work without financial necessity were often criticized for prioritizing themselves over family needs or their husbands were shamed for not being strong enough providers. The pressure to engage in sexual activity within marriage also increased, leading to nearly three decades of childbearing potential for young wives without effective contraceptives.

The prevailing stereotype was that women went to college primarily to find a husband, earning them the mockingly referred to "M.R.S." degree. Although women had other aspirations, the culture and media emphasized the importance of marriage over education and employment. Being single and pregnant was deemed completely unacceptable, leading to many quick marriages or girls being shamed and isolated during their pregnancies–often placed in unwed mothers’ homes and forced to give up their child for adoption. Despite societal pressures to remain virgins, premarital sex was happening, driving the need for reliable female-controlled contraceptives.

Suburban Conformity:

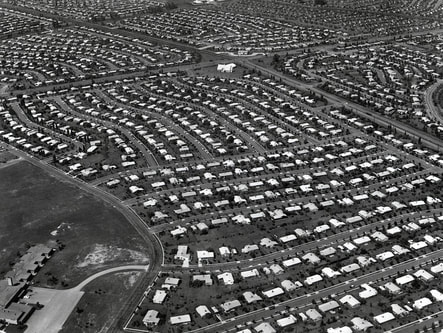

As post-war families grew they needed housing. The GI Bill offered service members support in settling down after the war, but where? William J. Levitt had the answer. Starting in 1947, he created entire communities of “starter houses” for young families on an assembly line in New Jersey. Over time, families would build additions, landscape their yards, and remodel kitchens to individualize each suburban house. But when they were built, they were called “little boxes” because they all looked simple and identical.

Levittown, as it came to be known, refused to sell homes to Black people for nearly twenty years. Levitt believed that if even one house was sold to a Black family, it would deter white customers, thus leading to de facto segregation. This discriminatory practice was not limited to Levittown as many suburban communities in the 1950s engaged in similar covert practices to maintain racial segregation.

Despite efforts by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) to challenge this discrimination in court, federal mortgaging agencies, such as the Federal Housing Administration and the Veterans Administration, were not mandated by Congress to prevent such discrimination in home sales.

It was only in late 1959, when the State Court of Pennsylvania threatened to hold public hearings about the issue, that Levitt finally decided to desegregate. Fearing negative press and public scrutiny, Levitt promised to end the discriminatory practices to avoid damaging his reputation. Levittown is an example of the enduring problem of segregation in suburban America. Today's most segregated states have large suburban populations, like New Jersey.

As post-war families grew they needed housing. The GI Bill offered service members support in settling down after the war, but where? William J. Levitt had the answer. Starting in 1947, he created entire communities of “starter houses” for young families on an assembly line in New Jersey. Over time, families would build additions, landscape their yards, and remodel kitchens to individualize each suburban house. But when they were built, they were called “little boxes” because they all looked simple and identical.

Levittown, as it came to be known, refused to sell homes to Black people for nearly twenty years. Levitt believed that if even one house was sold to a Black family, it would deter white customers, thus leading to de facto segregation. This discriminatory practice was not limited to Levittown as many suburban communities in the 1950s engaged in similar covert practices to maintain racial segregation.

Despite efforts by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) to challenge this discrimination in court, federal mortgaging agencies, such as the Federal Housing Administration and the Veterans Administration, were not mandated by Congress to prevent such discrimination in home sales.

It was only in late 1959, when the State Court of Pennsylvania threatened to hold public hearings about the issue, that Levitt finally decided to desegregate. Fearing negative press and public scrutiny, Levitt promised to end the discriminatory practices to avoid damaging his reputation. Levittown is an example of the enduring problem of segregation in suburban America. Today's most segregated states have large suburban populations, like New Jersey.

Images of white, middle-class conformity were presented to suburban families through the new, widespread medium of television. Families in the 1930s had listened to the news, comedy shows, baseball games, and FDR’s “Fireside Chats” on their new radios; post-war families learned about the world through television. Situation comedies, or sit-coms, and westerns dominated the evening fare. Boys learned how to be real men from Davy Crockett and Paladin, the Hero of “Have Gun, Will Travel,”and girls learned lessons of domestic life from “Leave it To Beaver” and “The Donna Reed Show,” among many others. Anyone could enjoy the antics of Jackie Gleason on “The Honeymooners” and Lucille Ball on “I Love Lucy.” On TV, Lucy’s attempts to have an independent life were thwarted by the expectations of 1950s domesticity. There were no female TV news anchors, but you might get a forecast from a “Weather Girl,” who was pretty but often not trained in the science of meteorology.

Despite the onscreen appeal, women who lived in suburbia expressed feelings of boredom and loneliness. When asked whom they missed the most, many responded, "My mother." Suburbs like Levittown changed American society by distancing families from their relatives and reducing multigenerational living. As women became mothers themselves, pregnancy humorously became known as the "Levittown look." The move to the suburbs isolated women from one another inside their homes.

Housing issues in the 1950s didn’t only impact Black and White Americans. Perhaps the most significant national policy affecting Native Americans occurred in the 1950s and had lasting impacts into modern history. Reservations had been impoverished since their establishment in the mid-1800s, and subsequent federal policies worsened their conditions. The Dawes Act of 1887 divided reservations into homesteads and opened surplus land to settlers, resulting in fragmented and unproductive parcels for Native people. Boarding schools forced Native children to assimilate, and the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) controlled their lives with insufficient funding and competence.

To address this, the Hoover Commission suggested encouraging young, employable Native individuals and cultured families to move from reservations to cities. The Navajo and Hopi reservations faced dire conditions in the late 1940s, leading Congress to allocate funds for improvements. In 1950, the Navajo-Hopi Rehabilitation Act appropriated money for these reservations but also aimed to relocate people from "overpopulated" reservations to cities.

Dillon S. Myer, who led the Japanese-American internment program, became the new BIA commissioner and initiated urban relocation. He saw reservations as inadequate and aimed to move Native Americans to cities. In 1951, BIA officers recruited individuals, preferably English-speaking, job-trained men, offering transportation, a stipend, and family support for a month. The initiative was designed to encourage Native people to leave reservations for urban areas.

In 1953, a year after launching the relocation program, the United States intensified its assimilation efforts towards Native Americans through a policy called termination. This involved dissolving treaties, dismantling tribal governance, and eliminating reservations. Historian Donald Fixico views termination as the most perilous policy, posing a significant threat to Native communities. The decision was formalized in House Concurrent Resolution 108, which, while seemingly benign, aimed to terminate all Native tribes, requiring approval from the president and Congress for each termination. This strategy aimed to eradicate reservations and Native identity over years through relocation and termination.

The rationale behind termination was multifaceted. Some believed it would free up Native lands for resource extraction like oil, uranium, and timber. Senator Arthur Watkins saw it as a means to promote self-sufficiency and integration into mainstream society. However, Native Americans opposed termination, fearing loss of sovereignty and heritage. They emphasized the importance of tribal governments and the spiritual significance of their land.

Termination led to significant changes in Native communities, impacting education, employment, healthcare, and well-being. The emergence of the American Indian Movement (AIM) in response to these challenges advocated for Indigenous rights, organizing protests, advocating for treaty rights, and establishing community programs. AIM's efforts, alongside other activists and policy changes, eventually contributed to the end of termination policies in the 1970s. Nonetheless, the consequences of termination continue to affect Native communities, spurring ongoing efforts to heal, revitalize culture, and overcome its enduring impact.

Despite the onscreen appeal, women who lived in suburbia expressed feelings of boredom and loneliness. When asked whom they missed the most, many responded, "My mother." Suburbs like Levittown changed American society by distancing families from their relatives and reducing multigenerational living. As women became mothers themselves, pregnancy humorously became known as the "Levittown look." The move to the suburbs isolated women from one another inside their homes.

Housing issues in the 1950s didn’t only impact Black and White Americans. Perhaps the most significant national policy affecting Native Americans occurred in the 1950s and had lasting impacts into modern history. Reservations had been impoverished since their establishment in the mid-1800s, and subsequent federal policies worsened their conditions. The Dawes Act of 1887 divided reservations into homesteads and opened surplus land to settlers, resulting in fragmented and unproductive parcels for Native people. Boarding schools forced Native children to assimilate, and the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) controlled their lives with insufficient funding and competence.

To address this, the Hoover Commission suggested encouraging young, employable Native individuals and cultured families to move from reservations to cities. The Navajo and Hopi reservations faced dire conditions in the late 1940s, leading Congress to allocate funds for improvements. In 1950, the Navajo-Hopi Rehabilitation Act appropriated money for these reservations but also aimed to relocate people from "overpopulated" reservations to cities.

Dillon S. Myer, who led the Japanese-American internment program, became the new BIA commissioner and initiated urban relocation. He saw reservations as inadequate and aimed to move Native Americans to cities. In 1951, BIA officers recruited individuals, preferably English-speaking, job-trained men, offering transportation, a stipend, and family support for a month. The initiative was designed to encourage Native people to leave reservations for urban areas.

In 1953, a year after launching the relocation program, the United States intensified its assimilation efforts towards Native Americans through a policy called termination. This involved dissolving treaties, dismantling tribal governance, and eliminating reservations. Historian Donald Fixico views termination as the most perilous policy, posing a significant threat to Native communities. The decision was formalized in House Concurrent Resolution 108, which, while seemingly benign, aimed to terminate all Native tribes, requiring approval from the president and Congress for each termination. This strategy aimed to eradicate reservations and Native identity over years through relocation and termination.

The rationale behind termination was multifaceted. Some believed it would free up Native lands for resource extraction like oil, uranium, and timber. Senator Arthur Watkins saw it as a means to promote self-sufficiency and integration into mainstream society. However, Native Americans opposed termination, fearing loss of sovereignty and heritage. They emphasized the importance of tribal governments and the spiritual significance of their land.

Termination led to significant changes in Native communities, impacting education, employment, healthcare, and well-being. The emergence of the American Indian Movement (AIM) in response to these challenges advocated for Indigenous rights, organizing protests, advocating for treaty rights, and establishing community programs. AIM's efforts, alongside other activists and policy changes, eventually contributed to the end of termination policies in the 1970s. Nonetheless, the consequences of termination continue to affect Native communities, spurring ongoing efforts to heal, revitalize culture, and overcome its enduring impact.

Polio Vaccine:

One of the worst aspects of life for mothers and children in the 1950s was the presence of the polio virus. Highly contagious, poliomyelitis caused paralysis and death and was most dangerous to young children. The polio vaccine development exemplifies the collaborative effort of a network of women, both scientists and non-scientists, whose contributions were crucial to its success. Polio outbreaks were a major public health concern in the first half of the 20th century US, affecting thousands of children and adults each year.

The number of Black children suffering from polio was significantly lower. Thus, polio was perceived as a “white disease” that didn’t affect Black children, which was certainly not the case. Segregation plagued every aspect of US society, including healthcare and made it difficult for the Black patients to get the care they needed.

Former president Franklin Roosevelt suffered from polio contracted as an adult and purchased the Warm Springs resort in Georgia which became a whites only rehabilitation center for elite polio patients. He also founded the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis (NFIP). NFIP launched campaigns to raise funds for polio research and patient care. The Million Mothers March mobilized women to march or participate in fundraising events across the country to raise awareness about polio and gather donations to aid in vaccine development. The money raised through the Million Mothers March led to the eventual development of effective vaccines against the disease. The Girl Scouts also participated in these efforts.

One of the worst aspects of life for mothers and children in the 1950s was the presence of the polio virus. Highly contagious, poliomyelitis caused paralysis and death and was most dangerous to young children. The polio vaccine development exemplifies the collaborative effort of a network of women, both scientists and non-scientists, whose contributions were crucial to its success. Polio outbreaks were a major public health concern in the first half of the 20th century US, affecting thousands of children and adults each year.

The number of Black children suffering from polio was significantly lower. Thus, polio was perceived as a “white disease” that didn’t affect Black children, which was certainly not the case. Segregation plagued every aspect of US society, including healthcare and made it difficult for the Black patients to get the care they needed.

Former president Franklin Roosevelt suffered from polio contracted as an adult and purchased the Warm Springs resort in Georgia which became a whites only rehabilitation center for elite polio patients. He also founded the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis (NFIP). NFIP launched campaigns to raise funds for polio research and patient care. The Million Mothers March mobilized women to march or participate in fundraising events across the country to raise awareness about polio and gather donations to aid in vaccine development. The money raised through the Million Mothers March led to the eventual development of effective vaccines against the disease. The Girl Scouts also participated in these efforts.

In 1939, the NFIP announced $161,350 to help address the discrimination facing Black polio patients. The funds established a polio center at the Tuskegee Institute. The purpose of this center was to provide modern treatment for Black infants affected by polio. Additionally, it aimed to train Black doctors, surgeons, orthopedic nurses, and physical therapists to help with polio treatments in segregated hospitals. The center had limited facilities and could only help a small fraction of Black patients who needed care. This highlighted the unequal access to medical care and resources for Black communities, and the burden for closing the gaps in care often fell on Black mothers.

Still the vaccine was far away. Dr. Isabel Morgan's breakthrough with a killed-virus vaccine in monkeys laid the foundation for a successful vaccine. Tragically, societal pressures led her to quit her research career after marriage. Famously in 1953, Dr. Jonas Salk revealed that he had produced a vaccine to prevent polio, and parents eagerly had their children vaccinated by injection. Elise Ward, a zoologist, supported this effort when she identified the best material for growing polioviruses, expediting vaccine research.

Vaccines began to roll out and were distributed in public spaces, often schools. Black children had to suffer the indignity of receiving the vaccine at white schools and being unable to use the restrooms during the process.

Despite women’s central roles in the vaccine development, sexism plagued the process to everyone’s detriment. Virologist Bernice Eddy worked in the lab testing vaccines before they were administered to the public in clinical trials. She noted a flawed vaccine batch that had live poliovirus in them. She reported her findings to William Workman, the head of the Laboratory of Biologics Control, but he failed to relay them to the vaccine licensing advisory committee. Despite being informed, William Sebrell, the director of the National Institutes of Health, also disregarded Eddy's findings and granted the vaccine license for public use. This led to the infection of tens of thousands of children and spread fear that vaccines were harmful. Around forty thousand developed a less aggressive type of polio, only 51 developed the fatal version of polio. Infected children also spread the virus to others. Five more children died and 113 developed a version of polio called paralytic poliomyelitis.

In 1957, Dr. Albert B. Sabin introduced a polio vaccine that could be administered in syrup. This increased the number of children who were protected against polio. The threat of the disease was considerably diminished and mothers could rest more easily. Today, there are no cases of polio in the US.

Dr. Isabel Morgan, Elise Ward, and Bernice Eddy were just a few of the women fighting for public health after the war. Dr. Hattie Elizabeth Alexander was also a professor and microbiologist who developed a serum for a vaccine for influenzal meningitis. Likewise, Sarah Elizabeth Stewart was instrumental to the development of the HPV vaccine through her work on viruses that cause cancer. Around the same time, Helen Murray Free and her husband developed the Multistix – a stick with chemical coatings that contained 10 different clinical tests, which could be performed on a single urine sample. These women revolutionized their fields of health and medicine, saving countless lives.

Still the vaccine was far away. Dr. Isabel Morgan's breakthrough with a killed-virus vaccine in monkeys laid the foundation for a successful vaccine. Tragically, societal pressures led her to quit her research career after marriage. Famously in 1953, Dr. Jonas Salk revealed that he had produced a vaccine to prevent polio, and parents eagerly had their children vaccinated by injection. Elise Ward, a zoologist, supported this effort when she identified the best material for growing polioviruses, expediting vaccine research.

Vaccines began to roll out and were distributed in public spaces, often schools. Black children had to suffer the indignity of receiving the vaccine at white schools and being unable to use the restrooms during the process.

Despite women’s central roles in the vaccine development, sexism plagued the process to everyone’s detriment. Virologist Bernice Eddy worked in the lab testing vaccines before they were administered to the public in clinical trials. She noted a flawed vaccine batch that had live poliovirus in them. She reported her findings to William Workman, the head of the Laboratory of Biologics Control, but he failed to relay them to the vaccine licensing advisory committee. Despite being informed, William Sebrell, the director of the National Institutes of Health, also disregarded Eddy's findings and granted the vaccine license for public use. This led to the infection of tens of thousands of children and spread fear that vaccines were harmful. Around forty thousand developed a less aggressive type of polio, only 51 developed the fatal version of polio. Infected children also spread the virus to others. Five more children died and 113 developed a version of polio called paralytic poliomyelitis.

In 1957, Dr. Albert B. Sabin introduced a polio vaccine that could be administered in syrup. This increased the number of children who were protected against polio. The threat of the disease was considerably diminished and mothers could rest more easily. Today, there are no cases of polio in the US.

Dr. Isabel Morgan, Elise Ward, and Bernice Eddy were just a few of the women fighting for public health after the war. Dr. Hattie Elizabeth Alexander was also a professor and microbiologist who developed a serum for a vaccine for influenzal meningitis. Likewise, Sarah Elizabeth Stewart was instrumental to the development of the HPV vaccine through her work on viruses that cause cancer. Around the same time, Helen Murray Free and her husband developed the Multistix – a stick with chemical coatings that contained 10 different clinical tests, which could be performed on a single urine sample. These women revolutionized their fields of health and medicine, saving countless lives.

Ecofeminism:

Women’s connection to nature has always been noted in literature, philosophy, even science. The “Earth Mother” was an embodiment of womanhood and women’s connections to the moon cycle were noted as far back as history can be traced. Real or imagined, this connection to nature became mainstream in the emerging ecofeminist movement. Ecofeminism is a philosophical and social movement that explores the intersections between feminism and environmentalism, aiming to address and challenge the interconnected systems of oppression and exploitation of both women and the natural world. It seeks to highlight the ways in which patriarchal and capitalist structures contribute to the degradation of both women and the environment, and it advocates for a more holistic and sustainable approach to social and ecological issues.

Rachel Carson was an American marine biologist, writer, and environmentalist best known for her groundbreaking work in raising awareness about the environmental impacts of pesticides and advocating for the preservation of nature. Her most influential book, "Silent Spring," was researched throughout the 1950s and final published in 1962, played a pivotal role in sparking the modern environmental movement and shaping the public's understanding of the harmful effects of chemical pesticides, particularly DDT (dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane), on ecosystems, wildlife, and human health.

Carson’s work stirred up a lot of trouble for the agriculture and chemical industries and thus received a lot of gendered pushback and hostility. Carson was an independent scholar who, being a woman, existed outside the conventional scientific knowledge framework due to her lack of institutional affiliations. Well-trained women scientists like Carson were sidelined and not given the recognition they deserved. Carson, in her own right, possessed impressive scientific credentials, having studied biology at Johns Hopkins University and made considerable progress toward her PhD. Her experiences during the Great Depression led her to work with the Fish and Wildlife Service, a respected research institution. She then transitioned to writing influential books about ocean life and critiquing the adverse effects of pesticides. Carson's approach towards understanding the natural world diverged from the prevailing mechanistic perspective of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, which viewed the world as an organic entity. She advocated an organic model that perceived nature as a living, feminine entity, necessitating a unique form of stewardship involving reciprocal interactions between humans and nature.

Carson sparked an environmental movement as well as brought ecofeminism out of the realm of literature and soft sciences and into the hard sciences. Building on works like Carson’s, ecofeminists argued that a lost world characterized by reciprocal relationships between men and women has been compromised due to male domination and science, resulting in the subjugation of both women and nature. Carson's writing not only exposed the dangers of pesticides but also criticized the lack of regulatory oversight and corporate influence in the use of these chemicals. Her work prompted public concern and policy changes, leading to the eventual banning of DDT in the United States and the establishment of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 1970.

But the work of environmentalism was far from over. With Cold War politics and fast, profit driven, capitalist markets, efforts to protect people from harmful toxins and dangerous company policies were constant. Perhaps the most notable example was Love Canal, a canal near Niagara Falls, NY which was used as a toxic waste dump. The canal ran through the surrounding working class communities and posed a threat to child development and overall human health. Lois Gibbs was a mother of an elementary schooler in that area and launched herself into activism. Along with her neighbors, they started the Love Canal Homeowners Association. For years they fought with the New York Department of Health to evacuate the region and begin a clean up of the toxic material. The EPA then instituted a program to cleanse other sites in the country.

Yet regardless of how engaged, educated, and serious women’s efforts to improve the world were, they were viewed by society at large through very gendered lenses.

Views on Women in Culture:

Pop culture and Hollywood shaped women’s perceptions of how they should behave. Elizabeth Taylor projected the image of the perfect woman, always put together, even while doing housework. Popular women’s magazines reinforced these images of the ideal woman. Women’s magazines and local newspapers featured advice columns. Twin sisters and rivals Ann Landers and Abigail Van Buren answered questions about life and love, children, and nosy neighbors. And they told women to be sure to iron bed sheets after they were washed. Women were advised that any problems in their marriages were their responsibilities to fix. In 1947, Ferdinand Lundberg and Marinya Farnham published Modern Woman, The Lost Sex. They argued that it was unnatural for women to compete with men in the workforce. This echoed Sigmund Freud’s idea that working women suffered from “penis envy.”

For women of color, cultural influences often reinforced racial stereotypes or were found in Black presses. Hattie McDaniel was an American actress and singer, best known for her groundbreaking role as Mammy in the 1939 film "Gone with the Wind." She won the Oscar for Best Supporting Actress, a significant achievement during a time of racial segregation. But that role and others epitomized the challenges facing Black stars and role models for young Black girls. McDaniel often played stereotypical roles of maids and other domestic workers.

Dorothy Dandridge, a multi-talented actress, singer, and dancer, gained fame during the 1950s. She started her career with small roles in short films and performing in nightclubs across the United States. Ebony magazine dubbed her "Hollywood's Newest Glamour Queen" in 1951, and she became one of the few African American actresses of that era to grace the cover of Life magazine. Her most notable role was in the musical Carmen Jones (1954), where she portrayed a spirited titular character. This performance earned her an Academy Award nomination for Best Actress, making her the first African American woman to receive such recognition in this Oscar category. Despite her talent, Dandridge faced racial discrimination, which limited her opportunities for significant roles in Hollywood. Moreover, she encountered various personal struggles that led to her unfortunate death at the age of 42. Nevertheless, her memory lives on, inspiring future generations of African American actresses.

Women’s connection to nature has always been noted in literature, philosophy, even science. The “Earth Mother” was an embodiment of womanhood and women’s connections to the moon cycle were noted as far back as history can be traced. Real or imagined, this connection to nature became mainstream in the emerging ecofeminist movement. Ecofeminism is a philosophical and social movement that explores the intersections between feminism and environmentalism, aiming to address and challenge the interconnected systems of oppression and exploitation of both women and the natural world. It seeks to highlight the ways in which patriarchal and capitalist structures contribute to the degradation of both women and the environment, and it advocates for a more holistic and sustainable approach to social and ecological issues.

Rachel Carson was an American marine biologist, writer, and environmentalist best known for her groundbreaking work in raising awareness about the environmental impacts of pesticides and advocating for the preservation of nature. Her most influential book, "Silent Spring," was researched throughout the 1950s and final published in 1962, played a pivotal role in sparking the modern environmental movement and shaping the public's understanding of the harmful effects of chemical pesticides, particularly DDT (dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane), on ecosystems, wildlife, and human health.

Carson’s work stirred up a lot of trouble for the agriculture and chemical industries and thus received a lot of gendered pushback and hostility. Carson was an independent scholar who, being a woman, existed outside the conventional scientific knowledge framework due to her lack of institutional affiliations. Well-trained women scientists like Carson were sidelined and not given the recognition they deserved. Carson, in her own right, possessed impressive scientific credentials, having studied biology at Johns Hopkins University and made considerable progress toward her PhD. Her experiences during the Great Depression led her to work with the Fish and Wildlife Service, a respected research institution. She then transitioned to writing influential books about ocean life and critiquing the adverse effects of pesticides. Carson's approach towards understanding the natural world diverged from the prevailing mechanistic perspective of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, which viewed the world as an organic entity. She advocated an organic model that perceived nature as a living, feminine entity, necessitating a unique form of stewardship involving reciprocal interactions between humans and nature.

Carson sparked an environmental movement as well as brought ecofeminism out of the realm of literature and soft sciences and into the hard sciences. Building on works like Carson’s, ecofeminists argued that a lost world characterized by reciprocal relationships between men and women has been compromised due to male domination and science, resulting in the subjugation of both women and nature. Carson's writing not only exposed the dangers of pesticides but also criticized the lack of regulatory oversight and corporate influence in the use of these chemicals. Her work prompted public concern and policy changes, leading to the eventual banning of DDT in the United States and the establishment of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 1970.

But the work of environmentalism was far from over. With Cold War politics and fast, profit driven, capitalist markets, efforts to protect people from harmful toxins and dangerous company policies were constant. Perhaps the most notable example was Love Canal, a canal near Niagara Falls, NY which was used as a toxic waste dump. The canal ran through the surrounding working class communities and posed a threat to child development and overall human health. Lois Gibbs was a mother of an elementary schooler in that area and launched herself into activism. Along with her neighbors, they started the Love Canal Homeowners Association. For years they fought with the New York Department of Health to evacuate the region and begin a clean up of the toxic material. The EPA then instituted a program to cleanse other sites in the country.

Yet regardless of how engaged, educated, and serious women’s efforts to improve the world were, they were viewed by society at large through very gendered lenses.

Views on Women in Culture:

Pop culture and Hollywood shaped women’s perceptions of how they should behave. Elizabeth Taylor projected the image of the perfect woman, always put together, even while doing housework. Popular women’s magazines reinforced these images of the ideal woman. Women’s magazines and local newspapers featured advice columns. Twin sisters and rivals Ann Landers and Abigail Van Buren answered questions about life and love, children, and nosy neighbors. And they told women to be sure to iron bed sheets after they were washed. Women were advised that any problems in their marriages were their responsibilities to fix. In 1947, Ferdinand Lundberg and Marinya Farnham published Modern Woman, The Lost Sex. They argued that it was unnatural for women to compete with men in the workforce. This echoed Sigmund Freud’s idea that working women suffered from “penis envy.”

For women of color, cultural influences often reinforced racial stereotypes or were found in Black presses. Hattie McDaniel was an American actress and singer, best known for her groundbreaking role as Mammy in the 1939 film "Gone with the Wind." She won the Oscar for Best Supporting Actress, a significant achievement during a time of racial segregation. But that role and others epitomized the challenges facing Black stars and role models for young Black girls. McDaniel often played stereotypical roles of maids and other domestic workers.

Dorothy Dandridge, a multi-talented actress, singer, and dancer, gained fame during the 1950s. She started her career with small roles in short films and performing in nightclubs across the United States. Ebony magazine dubbed her "Hollywood's Newest Glamour Queen" in 1951, and she became one of the few African American actresses of that era to grace the cover of Life magazine. Her most notable role was in the musical Carmen Jones (1954), where she portrayed a spirited titular character. This performance earned her an Academy Award nomination for Best Actress, making her the first African American woman to receive such recognition in this Oscar category. Despite her talent, Dandridge faced racial discrimination, which limited her opportunities for significant roles in Hollywood. Moreover, she encountered various personal struggles that led to her unfortunate death at the age of 42. Nevertheless, her memory lives on, inspiring future generations of African American actresses.

White women had greater freedom to push back against sexist stereotypes. Katherine Hepburn was one of the most popular actresses of the time. Hepburn was known for her unique fashion choices that often deviated from traditional feminine styles of her time. She preferred to wear pants and loose-fitting, comfortable clothing, which challenged the societal norms of the era. Hepburn frequently portrayed strong, assertive, and independent women. These characters were intelligent, self-reliant, and unafraid to express their opinions. By embodying such roles, she shattered the stereotype of women as passive and dependent on men, offering audiences alternative representations of femininity. She had an unconventional personal life and had a successful career in an industry defined by male views and power.

Women scientists also worked to negate these perspectives on women and prove that they were socially driven, not natural. Margaret Mead was known for her groundbreaking research and writings on various cultures, focusing particularly on the study of human behavior, gender roles, and sexuality. Her ideas about women and gender challenged prevailing notions about whether gender roles were defined by biology or culture. Her most famous research occurred in her 1928 "Coming of Age in Samoa," Mead found that women's roles and responsibilities varied significantly across cultures. She continued her research through mainstream channels into the 1950s. By studying societies where women held positions of power, authority, and influence, she challenged traditional patriarchal views that confined women to limited roles within society. She became curator of the American Museum of Natural History, was elected to the presidency of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1972.

Women scientists also worked to negate these perspectives on women and prove that they were socially driven, not natural. Margaret Mead was known for her groundbreaking research and writings on various cultures, focusing particularly on the study of human behavior, gender roles, and sexuality. Her ideas about women and gender challenged prevailing notions about whether gender roles were defined by biology or culture. Her most famous research occurred in her 1928 "Coming of Age in Samoa," Mead found that women's roles and responsibilities varied significantly across cultures. She continued her research through mainstream channels into the 1950s. By studying societies where women held positions of power, authority, and influence, she challenged traditional patriarchal views that confined women to limited roles within society. She became curator of the American Museum of Natural History, was elected to the presidency of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1972.

Hugh Hefner founded Playboy magazine in 1953 as a lifestyle and entertainment publication for men. The magazine included articles, advertisements for expensive shoes, alcoholic beverages, and tobacco products, as well as jokes that many men claimed were the main reason they subscribed to Playboy. The most prominent feature of Playboy magazine and the clubs Hefner created as part of the “Playboy Lifestyle” was scantily clad or nude women. The “Playboy Lifestyle” purported to allow men to have exposure to sexual images and content without social risk and upheld the idea that “boys will be boys.” Women felt pressured to accept these aspects of manhood that threatened their marital security and respect of women generally.

Yet women resisted. In 1963, a young Gloria Steinem, under the pseudonym "Bunny St. Marie," went undercover as a Playboy Bunny to write an exposé about her experience working at the Playboy Club in New York City. Her article, titled "A Bunny's Tale," was published in Show magazine and later became a book. Steinem shed light on the objectification and exploitation of women who worked as Playboy Bunnies. She criticized the sexist and demeaning treatment they endured, the strict grooming and appearance requirements they had to follow, and the overall degrading nature of their work environment. Steinem aimed to highlight the larger societal issues surrounding women's roles and treatment in the 1960s. The exposé was an important early work in her career as a feminist activist and writer, and it contributed to the growing feminist movement of that era.

Yet women resisted. In 1963, a young Gloria Steinem, under the pseudonym "Bunny St. Marie," went undercover as a Playboy Bunny to write an exposé about her experience working at the Playboy Club in New York City. Her article, titled "A Bunny's Tale," was published in Show magazine and later became a book. Steinem shed light on the objectification and exploitation of women who worked as Playboy Bunnies. She criticized the sexist and demeaning treatment they endured, the strict grooming and appearance requirements they had to follow, and the overall degrading nature of their work environment. Steinem aimed to highlight the larger societal issues surrounding women's roles and treatment in the 1960s. The exposé was an important early work in her career as a feminist activist and writer, and it contributed to the growing feminist movement of that era.

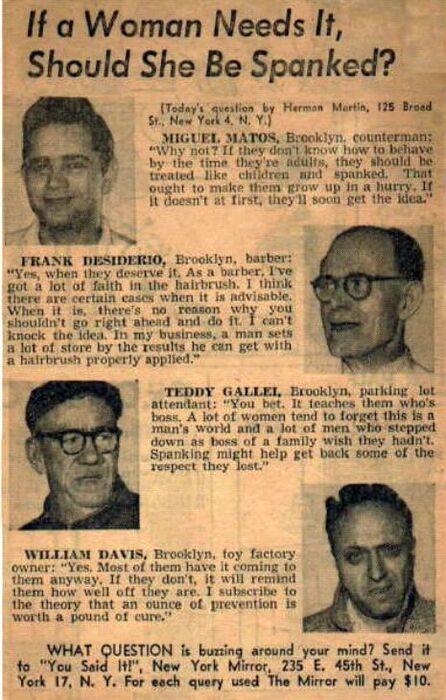

1950s advertisements for everything–from clothing and cigars to perfume and vacuum cleaners– were highly sexualized and encouraged stereotypes of women that belittled and demeaned them. They promoted and also echoed stereotypes of women that were already out in society. They spoke to readers as if women were the main consumers and men the breadwinners. Advertisements on everything sexualized women, even when sex had little to do with the product. Worse, these advertisements promoted sexualized violence. In one, men were told to beat their wives if they didn’t buy the right brand of coffee.

How much did this sexualized violence translate to the real world? In New York, a man was paid $10 to interview men on the question, “If a woman needs it, should she be spanked?” What “needs it” refers to is unclear. All four men featured in the interview agreed that it was an acceptable method of promoting the gender hierarchy. The alarming aspect of the interview is how openly they discuss male dominance and sadistic dehumanizing views of women. One said, “It teaches them who's boss. A lot of women seem to forget this is a man's world.” Another said, “Most of them have it coming to them anyway. If they don't, it will remind them how well off they are."

How much did this sexualized violence translate to the real world? In New York, a man was paid $10 to interview men on the question, “If a woman needs it, should she be spanked?” What “needs it” refers to is unclear. All four men featured in the interview agreed that it was an acceptable method of promoting the gender hierarchy. The alarming aspect of the interview is how openly they discuss male dominance and sadistic dehumanizing views of women. One said, “It teaches them who's boss. A lot of women seem to forget this is a man's world.” Another said, “Most of them have it coming to them anyway. If they don't, it will remind them how well off they are."

Laws Rigged Against Women:

Fighting against cultural norms was not easy because the laws and policies were built in favor of men. Women in various jobs were dismissed or fired when they got married or did not meet beauty standards for the role, standards men did not also have to meet. Flight attendants, known as stewardesses at the time, were fired if they gained weight. Teachers lost their contracts after marriage. This practice was rooted in discriminatory and sexist beliefs, it was commonly assumed that a married woman's primary role was to be a wife and mother, and that her commitment to these roles would hinder her ability to fulfill her professional duties effectively. This belief was particularly strong in the education sector, where teaching was considered an extension of a woman's domestic responsibilities.

In 1953, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in the case of Madden v. Kentucky that the state's marriage bar for women teachers was unconstitutional, marking a significant step towards ending this discriminatory policy. Gradually, as attitudes towards gender roles evolved and women's rights gained recognition, many school districts and governments eliminated marriage bars and other discriminatory practices. By the late 1960s and early 1970s, with the passage of federal legislation like Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Women's Educational Equity Act of 1974, such discriminatory practices were formally prohibited, ensuring that women teachers were no longer subjected to contract termination solely based on marriage.

This sort of economic discrimination hindered women in other ways too. Banks would not allow women to open a bank account or get a loan without a male co-signer such as a father, brother, or husband. When women sought credit cards or loans, they were subjected to numerous personal questions related to their marital status. Regardless of their financial capacity to repay, banks frequently discriminated against women with jobs or independent sources of money based on irrelevant factors. Without a male co-signer, women faced significant barriers in obtaining loans, severely limiting their financial, and personal, freedom and economic prospects.

Fighting against cultural norms was not easy because the laws and policies were built in favor of men. Women in various jobs were dismissed or fired when they got married or did not meet beauty standards for the role, standards men did not also have to meet. Flight attendants, known as stewardesses at the time, were fired if they gained weight. Teachers lost their contracts after marriage. This practice was rooted in discriminatory and sexist beliefs, it was commonly assumed that a married woman's primary role was to be a wife and mother, and that her commitment to these roles would hinder her ability to fulfill her professional duties effectively. This belief was particularly strong in the education sector, where teaching was considered an extension of a woman's domestic responsibilities.

In 1953, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in the case of Madden v. Kentucky that the state's marriage bar for women teachers was unconstitutional, marking a significant step towards ending this discriminatory policy. Gradually, as attitudes towards gender roles evolved and women's rights gained recognition, many school districts and governments eliminated marriage bars and other discriminatory practices. By the late 1960s and early 1970s, with the passage of federal legislation like Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Women's Educational Equity Act of 1974, such discriminatory practices were formally prohibited, ensuring that women teachers were no longer subjected to contract termination solely based on marriage.

This sort of economic discrimination hindered women in other ways too. Banks would not allow women to open a bank account or get a loan without a male co-signer such as a father, brother, or husband. When women sought credit cards or loans, they were subjected to numerous personal questions related to their marital status. Regardless of their financial capacity to repay, banks frequently discriminated against women with jobs or independent sources of money based on irrelevant factors. Without a male co-signer, women faced significant barriers in obtaining loans, severely limiting their financial, and personal, freedom and economic prospects.

Promoting sexualized violence in ads and culture is horrible, but it was even endorsed in the law. Before 1970, marital rape did not exist. According to coverture, the idea that a woman was her husband’s property, it was his right as a husband to have sexual access to her. This was exemplified in 1957 when Rollin M. Perkins wrote a treatise on criminal law where he claimed: “A man does not commit rape by having sexual intercourse with his lawful wife, even if he does so by force and against her will.” This attitude put women in a dangerous and vulnerable position in their homes with abusive spouses, especially when the surrounding culture endorses domestic violence. Upholding the exemption for marital rape through this period, provided a legal basis on which Playboy, sexist advertisers, and many others felt justified in sexualizing women for, by their logic, women’s bodies were for the possession of men.

After women won the vote, their independence as citizens grew in respect in other areas under law. Increasingly marriage became less about unifying a woman with a man and more about a partnership between two consenting people. But in the 1950s, by law in marriage women surrendered their bodies to a male right to sex. Then in 1954, an article in the Stanford Law Review, a journal where scholars of law discuss ideas, recognized a wife’s right to say no to sex. This was a big shift away from the idea of a wifely “duty” implied and imposed in law for centuries. It did however assume that rape in marriage was less bad than rape outside of marriage.

These shifts continued. Beginning in the 1950s and ending in 1962, the American Law Institute reviewed the state penal codes to remove outdated language and update terms. In the final version, The Model Penal Code, lawyers decided that husbands and wives were separate individuals under law. This was an incredibly progressive idea, but still the courts could not imagine prosecuting a husband for forcing his wife to have sex with him. Griswold v. Connecticut, while progressive in allowing spouses to use contraceptives, justified their argument using the idea that marriage was a private matter and that married couples had a right to sex, upholding the protections for husbands in marriage.

After women won the vote, their independence as citizens grew in respect in other areas under law. Increasingly marriage became less about unifying a woman with a man and more about a partnership between two consenting people. But in the 1950s, by law in marriage women surrendered their bodies to a male right to sex. Then in 1954, an article in the Stanford Law Review, a journal where scholars of law discuss ideas, recognized a wife’s right to say no to sex. This was a big shift away from the idea of a wifely “duty” implied and imposed in law for centuries. It did however assume that rape in marriage was less bad than rape outside of marriage.

These shifts continued. Beginning in the 1950s and ending in 1962, the American Law Institute reviewed the state penal codes to remove outdated language and update terms. In the final version, The Model Penal Code, lawyers decided that husbands and wives were separate individuals under law. This was an incredibly progressive idea, but still the courts could not imagine prosecuting a husband for forcing his wife to have sex with him. Griswold v. Connecticut, while progressive in allowing spouses to use contraceptives, justified their argument using the idea that marriage was a private matter and that married couples had a right to sex, upholding the protections for husbands in marriage.

Feminism?:

In 1963, Betty Fridan published her book, The Feminine Mystique. Friedan had been interviewing fellow Smith College alumni throughout the 1950s, asking them about their lives and the ways they were putting their high-powered liberal arts education to use. She found that white, middle-class women felt they had lost their purpose beyond their homes and families. They articulated what Friedan called “the problem that has no name.” Friedan argued that women needed to establish independent lives and that their intellect was good for something beyond their children’s fourth grade math homework. She uncovered widespread use of drugs, tranquilizers to help these smart women cope with boredom. Fridan’s book sold 1.4 million copies in its first printing and shaped feminist dialogs of the emerging movement.

Other research in the period has found that the cause of women’s frustrations during the period was their separation from extended families, the devaluing of the homemaker role by society and husbands, and the limited resources women had available to deal with problematic husbands. Some women used antidepressants and other medications not to cope with boredom, but to help them think clearly and gain perspective in stressful marriages.

In 1970, around one hundred women stormed the male-run magazine Ladies' Home Journal because of how it portrayed women. They refused to leave for almost 11 hours until their demands were met, including but not limited to an all-female editorial staff. The then-editor refused to resign, but eventually, Lenore Hershey took over as the first female editor in chief of the magazine. Change was in the air.

In 1971, future Supreme Court Justice, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, co-wrote a legal brief for the case Reed v. Reed, challenging an Idaho state law that favored men over women as administrators of estates. The court's unanimous ruling in favor of Ginsburg and her colleagues established that treating men and women differently based on sex was unconstitutional, applying the Constitution's 14th Amendment and Equal Protection Clause to gender discrimination cases.

In 1963, Betty Fridan published her book, The Feminine Mystique. Friedan had been interviewing fellow Smith College alumni throughout the 1950s, asking them about their lives and the ways they were putting their high-powered liberal arts education to use. She found that white, middle-class women felt they had lost their purpose beyond their homes and families. They articulated what Friedan called “the problem that has no name.” Friedan argued that women needed to establish independent lives and that their intellect was good for something beyond their children’s fourth grade math homework. She uncovered widespread use of drugs, tranquilizers to help these smart women cope with boredom. Fridan’s book sold 1.4 million copies in its first printing and shaped feminist dialogs of the emerging movement.

Other research in the period has found that the cause of women’s frustrations during the period was their separation from extended families, the devaluing of the homemaker role by society and husbands, and the limited resources women had available to deal with problematic husbands. Some women used antidepressants and other medications not to cope with boredom, but to help them think clearly and gain perspective in stressful marriages.

In 1970, around one hundred women stormed the male-run magazine Ladies' Home Journal because of how it portrayed women. They refused to leave for almost 11 hours until their demands were met, including but not limited to an all-female editorial staff. The then-editor refused to resign, but eventually, Lenore Hershey took over as the first female editor in chief of the magazine. Change was in the air.

In 1971, future Supreme Court Justice, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, co-wrote a legal brief for the case Reed v. Reed, challenging an Idaho state law that favored men over women as administrators of estates. The court's unanimous ruling in favor of Ginsburg and her colleagues established that treating men and women differently based on sex was unconstitutional, applying the Constitution's 14th Amendment and Equal Protection Clause to gender discrimination cases.

Three years later, amidst increasing activism, Congress passed the Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA) in 1974, explicitly prohibiting discrimination against borrowers based on sex or marital status. This landmark legislation marked a crucial step towards ending gender-based discrimination in financial matters.

The feminist movement of the 1960s and and 1970s helped to liberate women’s sexuality and resurface discussions about their consent to sex, even in marriage. Much of this movement from a legal basis was fueled by a dramatically increasing number of women graduating law school. Kate Millet’s 1969 thesis titled “Sexual Politics” built on arguments women suffragists had made connecting their oppression to race. She defined rape as an extension of the patriarchy, not an isolated incident of sexual violence. Feminist writer, Susan Griffin, wrote "The Politics of Rape" in which she said “rape is not an isolated act that can be rooted out from patriarchy without ending patriarchy itself” (Susan Griffin, "The Politics of Rape," Ramparts Mag., Sept. 1971). These cultural shifts in ideas and feminization of the legal profession radically changed views on the legality of marital rape.

Liberalizing divorce and contraceptive laws in the 1960s actually laid the groundwork to dismantle male protections in marriage. It used to be that men had more rights to divorce than women. They had many options to pursue a divorce. Women were left with only two neglect or abuse, which had to be proven in all male courts with all male juries. But as the laws changed to accept “no fault” divorce where there doesn’t have to be a specific reason to get a divorce, male rights to their marriage crumbled. Additionally, other court cases expanded the rights to contraception outside of marriage and this also showed that the right to privacy didn’t just apply to marriage but everywhere. No lawyer was willing to say rape was acceptable everywhere, so with that the marital exemption for rape dissintegrated.

Between 1974 and 1980, feminism joined with the battered women's movement to battle the legal challenges so visible in the 1950s. Women argued there wasn’t a difference between marital and nonmarital relationships in terms of a person’s right to bodily autonomy. These movements resulted in more women’s shelters to give women an escape from abusive husbands and provided the framework through which women transformed their "personal" problems into political issues.

The feminist movement of the 1960s and and 1970s helped to liberate women’s sexuality and resurface discussions about their consent to sex, even in marriage. Much of this movement from a legal basis was fueled by a dramatically increasing number of women graduating law school. Kate Millet’s 1969 thesis titled “Sexual Politics” built on arguments women suffragists had made connecting their oppression to race. She defined rape as an extension of the patriarchy, not an isolated incident of sexual violence. Feminist writer, Susan Griffin, wrote "The Politics of Rape" in which she said “rape is not an isolated act that can be rooted out from patriarchy without ending patriarchy itself” (Susan Griffin, "The Politics of Rape," Ramparts Mag., Sept. 1971). These cultural shifts in ideas and feminization of the legal profession radically changed views on the legality of marital rape.

Liberalizing divorce and contraceptive laws in the 1960s actually laid the groundwork to dismantle male protections in marriage. It used to be that men had more rights to divorce than women. They had many options to pursue a divorce. Women were left with only two neglect or abuse, which had to be proven in all male courts with all male juries. But as the laws changed to accept “no fault” divorce where there doesn’t have to be a specific reason to get a divorce, male rights to their marriage crumbled. Additionally, other court cases expanded the rights to contraception outside of marriage and this also showed that the right to privacy didn’t just apply to marriage but everywhere. No lawyer was willing to say rape was acceptable everywhere, so with that the marital exemption for rape dissintegrated.

Between 1974 and 1980, feminism joined with the battered women's movement to battle the legal challenges so visible in the 1950s. Women argued there wasn’t a difference between marital and nonmarital relationships in terms of a person’s right to bodily autonomy. These movements resulted in more women’s shelters to give women an escape from abusive husbands and provided the framework through which women transformed their "personal" problems into political issues.

Conclusion:

The immediate post-World War II period was characterized by comfort and conformity, challenge and change. Deeper exploration of this important decade shows that women continued to act as agents for change, first on behalf of their families, and then on their own behalf. Yet women like Margaret Mead, Katherine Hepburn, and others helped model a world that was different from the social, cultural, and government propaganda that aimed to limit women to the home rather than the full human experience. Feminism was present throughout this period, just as conservative attitudes prevailed. Rampant sexism and racism were obvious and a reckoning was coming, but how long would it take?

By the end of this era so much remained in question. How would the layers of race and class impact the reckoning to come? What issues would women choose to tackle first? What role would men play in supporting them? Who would be the main opponents to women’s liberation? And why?

The immediate post-World War II period was characterized by comfort and conformity, challenge and change. Deeper exploration of this important decade shows that women continued to act as agents for change, first on behalf of their families, and then on their own behalf. Yet women like Margaret Mead, Katherine Hepburn, and others helped model a world that was different from the social, cultural, and government propaganda that aimed to limit women to the home rather than the full human experience. Feminism was present throughout this period, just as conservative attitudes prevailed. Rampant sexism and racism were obvious and a reckoning was coming, but how long would it take?

By the end of this era so much remained in question. How would the layers of race and class impact the reckoning to come? What issues would women choose to tackle first? What role would men play in supporting them? Who would be the main opponents to women’s liberation? And why?

Draw your own conclusions

|

Learn how to teach with inquiry.

Many of these lesson plans were sponsored in part by the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources Eastern Region Program, coordinated by Waynesburg University, the History and Social Studies Education Faculty at Plymouth State University, and the Patrons of the Remedial Herstory Project. |

Lesson Plans from Other Organizations

- The National Women's History Museum has lesson plans on women's history.

- The Guilder Lehrman Institute for American History has lesson plans on women's history.

- The NY Historical Society has articles and classroom activities for teaching women's history.

- Unladylike 2020, in partnership with PBS, has primary sources to explore with students and outstanding videos on women from the Progressive era.

- The Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media has produced recommendations for teaching women's history with primary sources and provided a collection of sources for world history. Check them out!

- The Stanford History Education Group has a number of lesson plans about women in US History.

Period Specific Lesson Plans from Other Organizations

- Stanford History Education Group: The happy housewife is a common image of the 1950s. The lives of most women at this time, however, did not resemble this image because of economic and racial barriers. For those who were housewives, was this ideal a fulfilling reality? In this lesson plan, students consider economic and social conditions in the 1950s and question the happy housewife stereotype.

- Gilder Lehrman: This lesson explores the Feminine Mystique by Betty Friedan and asks What roles were women expected to play during the 1950s?

- Unladylike: Learn how Louise Arner Boyd defied expectations and gender roles to become a world famous Arctic explorer in this video from Unladylike2020. Boyd mapped unexplored regions of Greenland, studied and photographed topography, sea ice, glacial features, land formations and ocean depths, and made dozens of botanical discoveries. One of her innovations was the use of a heavy aerial mapping camera to document the glacial landscape at ground level, which served as the basis for new and more detailed maps of the region. Her photographs of glaciers provide critical information to climate change researchers today. Using video, discussion questions, vocabulary, and classroom activities, students learn about Boyd's contributions to science, geography, and our collective imagination about exploring new worlds.

- Gilder Lehrman: Students will be asked to read and analyze primary and secondary sources about Eleanor Roosevelt and the work she did to support social justice issues both in the United States and around the world. They will look at the role of first lady and see how Mrs. Roosevelt expanded that role to influence the political, social, and economic issues of the twentieth century. Students will increase their literacy skills as outlined in the Common Core Standards as they explore the social justice actions taken by Eleanor Roosevelt, which at times changed the course of world events.

Carol

|

An aspiring photographer develops an intimate relationship with an older woman in 1950s New York

|

|

LEsbian Bars

Dr. Marie Cartier: Baby, You Are My Religion

Prior to 1973, as many of you know, gay people were considered the nation’s largest security risk; more of us were let go of our jobs because of McCarthy than because we were homosexual rather than communist. The question was more often are you or have you ever been a homosexual than are you or have you ever been a communist? We were considered mentally ill until 1973, and there was no major or minor religion that considered us anything other than sinners. So to have any place that we could have community was not rare, it was impossible outside of the one public space that was available, which was the gay bar. So… for people pre-Stonewall, the gay bars operated as an alternate church space.

Cartier, Marie. “Dr. Marie Cartier presents ‘Baby You Are My Religion’ at ALMS 2011 Hosted by Mazer.” Keynote Address at ALMS. YouTube. 2011. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9kaS_pGyxmg&t=3s.

Cartier, Marie. “Dr. Marie Cartier presents ‘Baby You Are My Religion’ at ALMS 2011 Hosted by Mazer.” Keynote Address at ALMS. YouTube. 2011. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9kaS_pGyxmg&t=3s.

Dr. Marie Cartier: Myrna's Story

I came out as gay in 1945, the year that the war ended[…]I was dating a softball player than I met at the gay bar. I met her at Mona's, or as it was the Paper Pony. My first night in a gay bar was freedom. I had a gay male friend and he took me there. Burner was in the gay bars for eight years; She showed me her treasure from the 40s— a gold softball on a necklace chain from her first lover, inscribed with the initials from the professional softball league, to which women belong to, while the men were in the war. We went to the bar all the time. My entire social life was there, there was no other place.[…]I had insomnia— I used to phone up all the gay bars just to hear them answer the phone; just to hear the noise, oh yes. [I would call] just hear [to] the noise and the laughter in the background. I just wanted to be there me.

Cartier, Marie. “Dr. Marie Cartier presents ‘Marie Cartier reads Myrna's Story.” Presented at WeHo Lesbian Speaker Series. YouTube. September 2016. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FmURQ0iwhAM&t=5s.

Cartier, Marie. “Dr. Marie Cartier presents ‘Marie Cartier reads Myrna's Story.” Presented at WeHo Lesbian Speaker Series. YouTube. September 2016. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FmURQ0iwhAM&t=5s.

Dr. Marie Cartier: Theresa's Story

This woman had separated with her husband and was working as a migratory farmer with her new girlfriend when her ex-husband tracked them down. This is how she described that encounter.

“We went to Beaumont to pick cherries and we made like 50 cents an hour. And yes my ex-husband tracked me down, had a gun. She ran out of the trailer. He hit me in the face with the gun and I still have a scar, but that didn't stop me.”

Anonymous. “Marie Cartier Introduction to Informants for her book Baby, You Are My Religion.” YouTube. June L. Mazer Lesbian Archives. November 3, 2013. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EI-yYkKFdx8.

“We went to Beaumont to pick cherries and we made like 50 cents an hour. And yes my ex-husband tracked me down, had a gun. She ran out of the trailer. He hit me in the face with the gun and I still have a scar, but that didn't stop me.”

Anonymous. “Marie Cartier Introduction to Informants for her book Baby, You Are My Religion.” YouTube. June L. Mazer Lesbian Archives. November 3, 2013. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EI-yYkKFdx8.

Anonymous: Introduction

“[It] was sort of in a funny place, and [...] it was a nice bar, it was a nice good-looking bar. We had a lot of people, a lot of teachers, a lot of airline hostesses… Barbara had a really good time in the bar. Very religious… I sort of walked out of the convent door in 1967 and more or less walked into the door of a lesbian bar in 1968. They weren't that different— except–except for the lighting. One was stained glass and one with a little grittier. And the first time I ever went to bed with a woman was in the convent. The morning after we woke up and she said to me, something like I don't remember the exact words because it was ‘68 she said, the morning after we done it she said, ‘Wasn't that a remarkable religious experience we had?’ … I knew the difference between being a lesbian and being a nun and that I couldn't stay.”

Anonymous. “Marie Cartier Introduction to Informants for her book Baby, You Are My Religion.” YouTube. June L. Mazer Lesbian Archives. November 3, 2013. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EI-yYkKFdx8.

Anonymous. “Marie Cartier Introduction to Informants for her book Baby, You Are My Religion.” YouTube. June L. Mazer Lesbian Archives. November 3, 2013. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EI-yYkKFdx8.

Remedial Herstory Editors. "20. POST WAR WOMEN." The Remedial Herstory Project. November 20, 2022. www.remedialherstory.com.

Primary AUTHOR: |

Dr. Barbara Tischler

|

Primary ReviewerS: |

Kelsie Brook Eckert

|

Consulting TeamKelsie Brook Eckert, Project Director

Coordinator of Social Studies Education at Plymouth State University Dr. Barbara Tischler, Consultant Professor of History Hunter College and Columbia University Dr. Alicia Gutierrez-Romine, Consultant Assistant Professor of History at La Sierra University Jacqui Nelson, Consultant Teaching Lecturer of Military History at Plymouth State University Dr. Deanna Beachley Professor of History and Women's Studies at College of Southern Nevada |

EditorsReviewersColonial

Dr. Margaret Huettl Hannah Dutton Dr. John Krueckeberg 19th Century Dr. Rebecca Noel Michelle Stonis, MA Annabelle L. Blevins Pifer, MA Cony Marquez, PhD Candidate 20th Century Dr. Tanya Roth Dr. Jessica Frazier Mary Bezbatchenko, MA Dr. Alicia Gutierrez-Romine Matthew Cerjak |

|

Using evidence from primary sources as well as over seven years of interviews with sixteen women, Yamaguchi provides a feminist, intergenerational, and historical study of how unequal the justice system has been to this group of people and how it has affected their quality of life, sense of identity, and relationship with future generations.

|

In the popular stereotype of post-World War II America, women abandoned their wartime jobs and contentedly retreated to the home. These mythical women were like the 1950s TV character June Cleaver, white, middle-class, suburban housewives. Not June Cleaver unveils the diversity of postwar women, showing how far women departed form this one-dimensional image.

|

Homeward Bound tells the story of domestic containment - how it emerged, how it affected the lives of those who tried to conform to it, and how it unraveled in the wake of the Vietnam era's assault on Cold War culture, when unwed mothers, feminists, and "secular humanists" became the new "enemy."

|

|

The Montgomery Bus Boycott, which ignited the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s, has always been vitally important in southern and black history. With the publication of this book, the boycott becomes a milestone in the history of American women as well.

|