15. Women and World War I

|

The significant roles women played during World War I implored Americans to take a hard look at gender equality. The contributions and sacrifices made by women during this time ignited the demand for social change, which ultimately led to the ratification of the 19th Amendment.

|

World War I was named “The Great War” or more epically, “The War to End All Wars”. Trench warfare and mass casualties would soon define the era, but the actions of women here at home would define a generation, and shape women’s roles in America forever.

WWI began as a series of chain reactions to growing nationalism, industrialism, and complex alliances throughout Europe. Many nations would dive headlong into a conflict that would leave far too many dead, and the earth itself carved up by trenches and heavy artillery.

While each nation had varying reasons for joining and staying in the war, what each nation had in common were deep societal issues that bubbled at the surface before, during, and after the war. America was no different. Nationalism, nativism, racism, and sexism were alive and well in the land of the free, even as she went to Europe on a mission to “make the world safe for democracy”.

Women’s Peace Party:

At the start of the war in Europe, America declared its neutrality, intending to stay safe on its side of the Atlantic. As media outlets reported the high casualties, many Americans supported this decision; some aggressively so, like the Woman’s Peace Party.

Earlier peace efforts and organizations had often underrepresented women or kept them from leadership roles. Yet, within a month of the start of WWI in 1914, the Women's Peace Parade featured 1,500 women marching down NYC’s 5th Avenue. They marched silently, wearing all black, as a reminder of the mourning women nationwide would face if their country involved their sons, husbands, or fathers in this war.

After the march, seventy-year-old veteran of the Women’s Suffrage Movement, Fanny Garrison Villard, organized the group into a permanent organization. She also linked the group with key figures of women’s organizations like Carrie Chapman Catt, president of NAWSA, to prove to American women across the board that war should be avoided. They would also send delegates to the 1915 Congress of Women in Europe who sought their own resolution to the war.

Despite the best efforts of this group and others like it, peace did not come right away, nor could American neutrality last forever. By the end of 1916, it was clear that America was edging closer to war.

Thousands of Americans joined the American Preparedness Movement in preparation for America’s eventual entry for the war, with many of America’s women supporting them. At the same time, anti-war groups met regularly with President Wilson to continue to convince him that America had her own issues to tend to.

This division continued throughout America’s participation in the war.

Gold Star Mothers:

Despite many not agreeing with their stance of peace, the women-led peace organizations were correct in their depiction of mourning that Americans would soon face. European families had been facing losses for years and now American families were feeling that pain as the casualty lists began to grow.

Families recognized the service of their loved ones by displaying a blue banner out of their windows, and if that soldier lost their life, a gold star was added. President Wilson greatly opposed the public reminder that American men were dying in the service giving the division in the country but did approve the wearing of black armbands with a gold star by mothers and wives who had a family member who died in the military service to the United States.

It was Grace Darling Seribold in the decade after the war that united the Gold Star Mothers and convinced the federal government to finance their trips to Europe to visit their sons’ graves. The Gold Star Mothers organization still exists today to support families whose sons and daughters are lost in the military service.

Women Volunteer Corps:

It would not only be men who made families worry and mourn. Even while America was still neutral, many Americans made their way to Europe as volunteers. Men joined the armies of Europe, and hundreds of American women served in military hospitals, attempting to tackle the horror of industrial war. Within a month of America declaring war, American nurses and doctors would be the first servicemembers to arrive in Europe. Over 20,000 American women would serve in foreign hospitals, though that number would have been significantly higher if African American and immigrant women were not rejected. Surprisingly, however, Indigenous women were allowed to serve as nurses. For instance, Edith Monture, pictured below on the right, volunteered with the U.S. Army Nurse Corps and served in France. Additionally, the Red Cross’s number of volunteers who remained mostly stateside, rose over eight million.

WWI began as a series of chain reactions to growing nationalism, industrialism, and complex alliances throughout Europe. Many nations would dive headlong into a conflict that would leave far too many dead, and the earth itself carved up by trenches and heavy artillery.

While each nation had varying reasons for joining and staying in the war, what each nation had in common were deep societal issues that bubbled at the surface before, during, and after the war. America was no different. Nationalism, nativism, racism, and sexism were alive and well in the land of the free, even as she went to Europe on a mission to “make the world safe for democracy”.

Women’s Peace Party:

At the start of the war in Europe, America declared its neutrality, intending to stay safe on its side of the Atlantic. As media outlets reported the high casualties, many Americans supported this decision; some aggressively so, like the Woman’s Peace Party.

Earlier peace efforts and organizations had often underrepresented women or kept them from leadership roles. Yet, within a month of the start of WWI in 1914, the Women's Peace Parade featured 1,500 women marching down NYC’s 5th Avenue. They marched silently, wearing all black, as a reminder of the mourning women nationwide would face if their country involved their sons, husbands, or fathers in this war.

After the march, seventy-year-old veteran of the Women’s Suffrage Movement, Fanny Garrison Villard, organized the group into a permanent organization. She also linked the group with key figures of women’s organizations like Carrie Chapman Catt, president of NAWSA, to prove to American women across the board that war should be avoided. They would also send delegates to the 1915 Congress of Women in Europe who sought their own resolution to the war.

Despite the best efforts of this group and others like it, peace did not come right away, nor could American neutrality last forever. By the end of 1916, it was clear that America was edging closer to war.

Thousands of Americans joined the American Preparedness Movement in preparation for America’s eventual entry for the war, with many of America’s women supporting them. At the same time, anti-war groups met regularly with President Wilson to continue to convince him that America had her own issues to tend to.

This division continued throughout America’s participation in the war.

Gold Star Mothers:

Despite many not agreeing with their stance of peace, the women-led peace organizations were correct in their depiction of mourning that Americans would soon face. European families had been facing losses for years and now American families were feeling that pain as the casualty lists began to grow.

Families recognized the service of their loved ones by displaying a blue banner out of their windows, and if that soldier lost their life, a gold star was added. President Wilson greatly opposed the public reminder that American men were dying in the service giving the division in the country but did approve the wearing of black armbands with a gold star by mothers and wives who had a family member who died in the military service to the United States.

It was Grace Darling Seribold in the decade after the war that united the Gold Star Mothers and convinced the federal government to finance their trips to Europe to visit their sons’ graves. The Gold Star Mothers organization still exists today to support families whose sons and daughters are lost in the military service.

Women Volunteer Corps:

It would not only be men who made families worry and mourn. Even while America was still neutral, many Americans made their way to Europe as volunteers. Men joined the armies of Europe, and hundreds of American women served in military hospitals, attempting to tackle the horror of industrial war. Within a month of America declaring war, American nurses and doctors would be the first servicemembers to arrive in Europe. Over 20,000 American women would serve in foreign hospitals, though that number would have been significantly higher if African American and immigrant women were not rejected. Surprisingly, however, Indigenous women were allowed to serve as nurses. For instance, Edith Monture, pictured below on the right, volunteered with the U.S. Army Nurse Corps and served in France. Additionally, the Red Cross’s number of volunteers who remained mostly stateside, rose over eight million.

Nurses serving in the war were meant to be safe from the horrors of combat, but in an effort to save as many lives as possible, many agreed to work closer and closer to the front lines. One American woman, Beatrice MacDonald, was so close to the front lines that she took shrapnel from an artillery blast that left her with only one eye. She refused to go home, and served until the very end of the war, earning herself the Distinguished Service Cross.

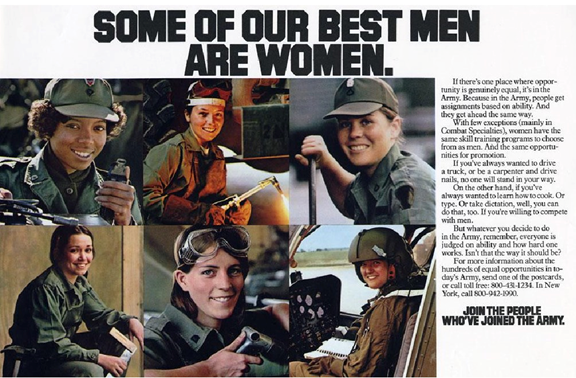

Women were also recruited into the military in order to free men up for the battlefield. This would include some nurses, but women joined the Army, Navy, and Marine Corps as drivers, telephone and radio operators, clerical workers, laborers, and more. By the end of the war, 11,000 women had joined the Navy, over 7,000 women applied to the Army, and over two hundred were sent overseas as radio and telephone operators, and over 300 women would join the Marine Corps. Some left the war highly decorated, including Lenah Sutcliffe Higbee, who was chief of the Navy Nursing Corps and was the first woman awarded the Navy Cross. This award is only surpassed by the Medal of Honor in its esteem.

As with nurses, women were kept from combat, but not from risk. Six hundred women lost their lives serving in World War I.

The Rise of Home Economics:

During WWI, women were also found in the burgeoning field of Home Economics. Home economics was a field of vocational study that focused on applying scientific principles to the running of a household. Initially developed by scientists and activists in the late 1800s, home economics shifted over the decades from an educational movement that sought to professionalize women’s labor in the household to a consumer education program during the heyday of American post-war consumerism after WWII.

As a field, home economics has a long history. It was initially championed by suffragists such as Catherine Beecher (sister of Harriet Beecher Stowe) and Mary Beaumont Welsh in the late 1800s. However, it is Ellen Swallow Richards who takes the title of the founder of Home Economics. Born in Massachusetts in 1842,Richards was an engineer and a chemist. She had studied at Vassar and received her B.A. and M.A. there before being the first woman admitted to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where she graduated with a M.Sc. in 1873. She became MIT’s first female instructor when she accepted the job of (unpaid) chemistry lecturer.

In her professional life, she was interested in applying scientific principles to the home, such as considering the chemistry that underlies nutritional science. You can see the basis of home economics in the natural sciences in the definition that she and her colleagues settled on in the 4th Lake Placid Conference for home economics:

1. Home economics in its most comprehensive sense is the study of the laws, conditions, principles and ideals which are concerned on one hand with man's immediate physical environment and on the other hand with his nature as a social being, and is the study especially of the relation between those two factors;

2. In a narrow sense the term is given to the study of the empirical sciences with special reference to the practical problems of housework, cooking, etc.

Subsequently Richards would go on to found the American Home Economics Association and take the role of its first President. Home economics would prove to be a professional field almost exclusively available to women, where their presumed expertise over the home helped legitimize their scholarly and vocational pursuits.

By WWI, home economics was a field on the brink of expansion. In 1914 and 1917, acknowledging the need for greater vocational training, the U.S. Congress passed the Smith-Lever Act and the Smith-Hughes Act, which allocated federal funds for education in agriculture, trades and industry – including homemaking. These funds were used to expand home economics courses across the country. It is notable that of all the vocational fields listed, only homemaking was singled out for women and girls.

After WWI, the fate of home economics would rise and fall. In the 1930s and 40s young women home economists were recruited into public service under F.D.R.’s New Deal programming. Especially during the Great Depression and WWII, home economists traveled through rural America to teach farm women how the latest science and technologies could improve their lives. However, at this time, corporations also saw the appeal of home economics. Home economists working in the public interest focused on consumer education while home economists hired by corporations helped companies market their products to homemakers. By the 1960s home economics courses were taught to both boys and girls, as second-wave feminism focused on equality in the workforce.

Impact of War on Suffrage:

The National Parks Service may have articulated this best when they wrote: “The Service of American women at war cost them more than just the burden of putting their lives on hold, deferring marriage and children, or pursuing higher education. The sacrifice of these women went far beyond that; in all more than six-hundred of these patriotic women lost their lives in service to their nation. The question was, how would the nation return that debt?”

This question is fitting, as America still denied women basic rights of citizenship, like the right to vote. The matter of women’s suffrage would be at the forefront despite the war, and President Wilson was not happy about it. Wilson thought it was a distraction from larger matters, and would even imprison women protesting for this right amidst the war.

The Women’s Suffrage Movement has been ongoing since America’s earliest colonial roots, but formally began in 1848. By the time World War I came around, women were not only sick of waiting, but Suffragists were also at war with themselves, as the major parties and feminists within the movement divided over opinions on goals, methods, and the extremes they were willing to take to reach their goals.

By 1890, the movement was mainly under the leadership of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, with Elizabeth Cady Stanton serving as their first president.

Several Western states soon started to extend the vote to women, and by 1916, Jeanette Rankin became the first American woman to hold federal office as a representative of Montana. However, the states in the East and South were holding firm against suffrage. NAWSA’s president Carrie Chapman Catt called for a national push. Women in states that already had the vote should push for a federal amendment, women in states without it should continue to work on the state level.

For some, these methods were simply too slow. NAWSA saw a splinter organization form, called the National Woman’s Party. This group, led by Alice Paul, Lucy Burns, Gail Laughlin, and more, decided that asking for the vote had long proven ineffective, and it was time to demand it. Paul proclaimed that, “There will never be a new world order until women are a part of it.”

The NWP protested at the White House, held parades, published more militant literature, and even used hunger strikes to make their point known. Paul and a number of her followers would be arrested and spend time in jail for their tactics, but their message was clear: It was time for women to be recognized politically!

Paul would also address the elephant in the room, being the international crisis of war. She said, “The world crisis came about without women having anything to do with it. If the women of the world had not been excluded from world affairs, things today might have been different.”

President Wilson, who had never been a big supporter of women’s rights, was even compelled to call upon Congress for suffrage. When he asked them to pass the 19th Amendment, he said, “I regard the concurrence of the Senate in the constitutional amendment proposing the extension of the suffrage to women as vitally essential to the successful prosecution of the great war of humanity in which we are engaged. The tasks of the women lie at the very heart of the war, and I know how much stronger that heart will beat if you do this just thing and show our women that you trust them as much as you in fact and of necessity depend upon them.”

In the end, the work of women in the war effort, the sacrifices made by American women during this time, the protests and demands of women’s organizations helped them to achieve a goal more than 150 years in the making.

By the end of this era, so much remained in question. President Wilson proclaimed America’s participation in the war was to make the world safe for democracy, but was America itself safe for democracy when half of its population was barred from voting based on their gender alone? To what extent did environment and timing make catalysts for social change?

Women were also recruited into the military in order to free men up for the battlefield. This would include some nurses, but women joined the Army, Navy, and Marine Corps as drivers, telephone and radio operators, clerical workers, laborers, and more. By the end of the war, 11,000 women had joined the Navy, over 7,000 women applied to the Army, and over two hundred were sent overseas as radio and telephone operators, and over 300 women would join the Marine Corps. Some left the war highly decorated, including Lenah Sutcliffe Higbee, who was chief of the Navy Nursing Corps and was the first woman awarded the Navy Cross. This award is only surpassed by the Medal of Honor in its esteem.

As with nurses, women were kept from combat, but not from risk. Six hundred women lost their lives serving in World War I.

The Rise of Home Economics:

During WWI, women were also found in the burgeoning field of Home Economics. Home economics was a field of vocational study that focused on applying scientific principles to the running of a household. Initially developed by scientists and activists in the late 1800s, home economics shifted over the decades from an educational movement that sought to professionalize women’s labor in the household to a consumer education program during the heyday of American post-war consumerism after WWII.

As a field, home economics has a long history. It was initially championed by suffragists such as Catherine Beecher (sister of Harriet Beecher Stowe) and Mary Beaumont Welsh in the late 1800s. However, it is Ellen Swallow Richards who takes the title of the founder of Home Economics. Born in Massachusetts in 1842,Richards was an engineer and a chemist. She had studied at Vassar and received her B.A. and M.A. there before being the first woman admitted to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where she graduated with a M.Sc. in 1873. She became MIT’s first female instructor when she accepted the job of (unpaid) chemistry lecturer.

In her professional life, she was interested in applying scientific principles to the home, such as considering the chemistry that underlies nutritional science. You can see the basis of home economics in the natural sciences in the definition that she and her colleagues settled on in the 4th Lake Placid Conference for home economics:

1. Home economics in its most comprehensive sense is the study of the laws, conditions, principles and ideals which are concerned on one hand with man's immediate physical environment and on the other hand with his nature as a social being, and is the study especially of the relation between those two factors;

2. In a narrow sense the term is given to the study of the empirical sciences with special reference to the practical problems of housework, cooking, etc.

Subsequently Richards would go on to found the American Home Economics Association and take the role of its first President. Home economics would prove to be a professional field almost exclusively available to women, where their presumed expertise over the home helped legitimize their scholarly and vocational pursuits.

By WWI, home economics was a field on the brink of expansion. In 1914 and 1917, acknowledging the need for greater vocational training, the U.S. Congress passed the Smith-Lever Act and the Smith-Hughes Act, which allocated federal funds for education in agriculture, trades and industry – including homemaking. These funds were used to expand home economics courses across the country. It is notable that of all the vocational fields listed, only homemaking was singled out for women and girls.

After WWI, the fate of home economics would rise and fall. In the 1930s and 40s young women home economists were recruited into public service under F.D.R.’s New Deal programming. Especially during the Great Depression and WWII, home economists traveled through rural America to teach farm women how the latest science and technologies could improve their lives. However, at this time, corporations also saw the appeal of home economics. Home economists working in the public interest focused on consumer education while home economists hired by corporations helped companies market their products to homemakers. By the 1960s home economics courses were taught to both boys and girls, as second-wave feminism focused on equality in the workforce.

Impact of War on Suffrage:

The National Parks Service may have articulated this best when they wrote: “The Service of American women at war cost them more than just the burden of putting their lives on hold, deferring marriage and children, or pursuing higher education. The sacrifice of these women went far beyond that; in all more than six-hundred of these patriotic women lost their lives in service to their nation. The question was, how would the nation return that debt?”

This question is fitting, as America still denied women basic rights of citizenship, like the right to vote. The matter of women’s suffrage would be at the forefront despite the war, and President Wilson was not happy about it. Wilson thought it was a distraction from larger matters, and would even imprison women protesting for this right amidst the war.

The Women’s Suffrage Movement has been ongoing since America’s earliest colonial roots, but formally began in 1848. By the time World War I came around, women were not only sick of waiting, but Suffragists were also at war with themselves, as the major parties and feminists within the movement divided over opinions on goals, methods, and the extremes they were willing to take to reach their goals.

By 1890, the movement was mainly under the leadership of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, with Elizabeth Cady Stanton serving as their first president.

Several Western states soon started to extend the vote to women, and by 1916, Jeanette Rankin became the first American woman to hold federal office as a representative of Montana. However, the states in the East and South were holding firm against suffrage. NAWSA’s president Carrie Chapman Catt called for a national push. Women in states that already had the vote should push for a federal amendment, women in states without it should continue to work on the state level.

For some, these methods were simply too slow. NAWSA saw a splinter organization form, called the National Woman’s Party. This group, led by Alice Paul, Lucy Burns, Gail Laughlin, and more, decided that asking for the vote had long proven ineffective, and it was time to demand it. Paul proclaimed that, “There will never be a new world order until women are a part of it.”

The NWP protested at the White House, held parades, published more militant literature, and even used hunger strikes to make their point known. Paul and a number of her followers would be arrested and spend time in jail for their tactics, but their message was clear: It was time for women to be recognized politically!

Paul would also address the elephant in the room, being the international crisis of war. She said, “The world crisis came about without women having anything to do with it. If the women of the world had not been excluded from world affairs, things today might have been different.”

President Wilson, who had never been a big supporter of women’s rights, was even compelled to call upon Congress for suffrage. When he asked them to pass the 19th Amendment, he said, “I regard the concurrence of the Senate in the constitutional amendment proposing the extension of the suffrage to women as vitally essential to the successful prosecution of the great war of humanity in which we are engaged. The tasks of the women lie at the very heart of the war, and I know how much stronger that heart will beat if you do this just thing and show our women that you trust them as much as you in fact and of necessity depend upon them.”

In the end, the work of women in the war effort, the sacrifices made by American women during this time, the protests and demands of women’s organizations helped them to achieve a goal more than 150 years in the making.

By the end of this era, so much remained in question. President Wilson proclaimed America’s participation in the war was to make the world safe for democracy, but was America itself safe for democracy when half of its population was barred from voting based on their gender alone? To what extent did environment and timing make catalysts for social change?

Draw your own conclusions

|

Learn how to teach with inquiry.

Many of these lesson plans were sponsored in part by the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources Eastern Region Program, coordinated by Waynesburg University, the History and Social Studies Education Faculty at Plymouth State University, and the Patrons of the Remedial Herstory Project. |

Lesson Plans from Other Organizations

- The National Women's History Museum has lesson plans on women's history.

- The Guilder Lehrman Institute for American History has lesson plans on women's history.

- The NY Historical Society has articles and classroom activities for teaching women's history.

- Unladylike 2020, in partnership with PBS, has primary sources to explore with students and outstanding videos on women from the Progressive era.

- The Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media has produced recommendations for teaching women's history with primary sources and provided a collection of sources for world history. Check them out!

- The Stanford History Education Group has a number of lesson plans about women in US History.

Period Specific Lesson Plans from Other Organizations

- Gilder Lehrman: This unit examines the complexity of women’s contributions to World War I. Together, these resources shed light on World War I in a compelling and very human way. The students will demonstrate what they have learned through their analysis of the various primary sources by writing a response to an essential questions posed for the unit.

- National History Day: Juliette Gordon Low (1860-1927) was nicknamed “Daisy” as an infant and the moniker stuck; her friends and family used it her whole life. Low’s childhood was marred by the outbreak of the Civil War; her mother’s family fought for the Union while her father served as a Confederate soldier. She enjoyed adventures in the Georgia countryside and her love of nature, wildlife, and sports shaped the organization she founded. A series of childhood ear infections and a botched operation left her with significant hearing loss. She married William Low in 1886 and set up homes in Georgia and England. Searching for purpose after her husband’s 1905 death, a chance 1911 meeting with Sir Robert Baden-Powell in London changed her life. Baden-Powell, the founder of Boy Scouts, recommended that Low become involved with the Girl Guides, the female equivalent of his organization. After working with female troops in England and Scotland, Low returned to Georgia to replicate the organization in America. On March 12, 1912, Low hosted the inaugural meeting of Girl Scouts of the USA. Low spent the rest of her life leading the organization, stressing leadership, community involvement, and outdoor activities. The Girl Scouts thrive today, boasting 2.6 million participants in 92 countries and an alumnae network of over 50 million women.

- National History Day: Jeannette Rankin (1880-1973) was born and raised in Montana. While studying social work at the University of Washington, she joined the woman suffrage movement. Soon after, she became a field secretary for the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). She traveled across the United States, advocating for suffrage. In 1916, she was elected as the first woman in the U.S. House of Representatives. Just three days after being sworn in, she cast one of two votes that would define public memory of her service - a vote against the American declaration of war on Germany in World War I. Rankin introduced a voting rights amendment that passed the House in 1918, and was the only woman in Congress to cast a vote for woman suffrage. She unsuccessfully ran for U.S. Senate in 1918, and spent the next two decades advocating for peace and social welfare. In 1940, she was again elected to the House, and in 1941, cast the only vote against the declaration of war on Japan. She left Congress in 1942, and remained active in anti-war movements and the philosophy of nonviolent protest for the rest of her life. She died in California in 1973.

- Unladylike: Learn how Jeannette Rankin became the first woman in United States history elected to the U.S. Congress, representing the state of Montana in the U.S. House of Representatives, in this video from Unladylike2020. As a suffragist and life-long pacifist, Rankin fought tirelessly for women’s right to vote, and voted against United States entry into WWI and WWII. Utilizing video, discussion questions, vocabulary, and teaching tips, students learn about Rankin’s role in securing women the vote nationally, and her enduring commitment to ending war.

William C. Morris: Political Cartoon

William C. Morris, “If you are good enough for war, you are good enough to vote.” Brooklyn Magazine. November 10, 1917. Illustration. https://www.army.mil/article/192727/how_world_war_i_helped_give_us_women_the_right_to_vote.

Questions for Analysis:

Questions for Analysis:

- What is the message of this illustration?

- Why do you think this image connects women’s voting rights to women’s work supporting World War I?

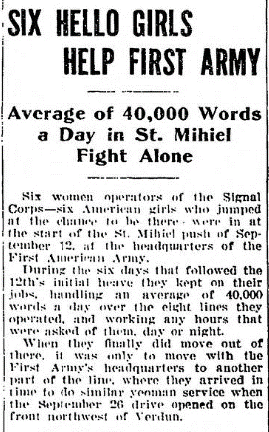

Stars and Stripes: Six Hello Girls

SIX HELLO GIRLS HELP FIRST ARMY

Average of 40,000 Words a Day in St. Mihiel Fight Alone

Six women operators of the Signal Corps-six American girls who jumped at the chance to be there were in at the start of the St. Mihiel push of Sep- tember 12. at the headquarters of the First American Army.

During the six days that followed the 12th's initial heave they kept on their jobs, handling an average of 40,000 words a day over the eight lines they operated, and working any hours that were asked of them, day or night.

When they finally did move out of there, it was only to move with the First Army's headquarters to another part of the line, where they arrived in time to do similar yeoman service when the September 26 drive opened on the front northwest of Verdun.

To Give Everyone Chance

The lucky half-dozen-Chief Operator Grace 1. Banker and Operators Esther V. Fresnel. Helen E. Hill. Berthe M. Hunt. Marie Large, and Suzanne Pre- vot--were chosen out of a total of 225 girl operators all just dying for the chance to go up forward. It was a hard job to pick out the ones who were to go. so anxious was the whole force to get a ernek at the big show at close

range.

In fact, the only way that peace could be kept in the Signal Corps family was to promise the girls who weren't picked for the headquarters Job on the two big shows that the up-front work would be rotated as often as possible, so that every one might know what it was like to be handling the calls on which the success or failure of the operation might depend.

The six American girls, while up front, rough it with the best of the Army, billetted, to be sure, but subject to all the discomforts and dangers that come with being billetted in the forward area over which the Roche avions fly when they can.

According to their superior officers. both in the Signal Corps and on the General Staff, they have shown remark- able spirit and utter absence of nerves. And, needless to say, they have filled every one of the 500-odd male soldier operators in the A.E F., toiling away further down the line and answering the calls of the Telephona Sextette, with a green and rankling envy.

“Six Hello Girls Help First Army,” The Stars and Stripes. (Paris County, France), Oct. 4 1918. https://www.loc.gov/item/20001931/1918-10-04/ed-1/.

Questions for Analysis:

Average of 40,000 Words a Day in St. Mihiel Fight Alone

Six women operators of the Signal Corps-six American girls who jumped at the chance to be there were in at the start of the St. Mihiel push of Sep- tember 12. at the headquarters of the First American Army.

During the six days that followed the 12th's initial heave they kept on their jobs, handling an average of 40,000 words a day over the eight lines they operated, and working any hours that were asked of them, day or night.

When they finally did move out of there, it was only to move with the First Army's headquarters to another part of the line, where they arrived in time to do similar yeoman service when the September 26 drive opened on the front northwest of Verdun.

To Give Everyone Chance

The lucky half-dozen-Chief Operator Grace 1. Banker and Operators Esther V. Fresnel. Helen E. Hill. Berthe M. Hunt. Marie Large, and Suzanne Pre- vot--were chosen out of a total of 225 girl operators all just dying for the chance to go up forward. It was a hard job to pick out the ones who were to go. so anxious was the whole force to get a ernek at the big show at close

range.

In fact, the only way that peace could be kept in the Signal Corps family was to promise the girls who weren't picked for the headquarters Job on the two big shows that the up-front work would be rotated as often as possible, so that every one might know what it was like to be handling the calls on which the success or failure of the operation might depend.

The six American girls, while up front, rough it with the best of the Army, billetted, to be sure, but subject to all the discomforts and dangers that come with being billetted in the forward area over which the Roche avions fly when they can.

According to their superior officers. both in the Signal Corps and on the General Staff, they have shown remark- able spirit and utter absence of nerves. And, needless to say, they have filled every one of the 500-odd male soldier operators in the A.E F., toiling away further down the line and answering the calls of the Telephona Sextette, with a green and rankling envy.

“Six Hello Girls Help First Army,” The Stars and Stripes. (Paris County, France), Oct. 4 1918. https://www.loc.gov/item/20001931/1918-10-04/ed-1/.

Questions for Analysis:

- What were the Hello Girls doing to support the war effort?

- According to this article, why were these women taken to France?

Nina Macdonald: Sing a Song of Wartime

Sing a song of War-Time,

Soldiers marching by,

Crowds of people standing,

Waving them 'Good-bye'.

When the crowds are over,

Home we go to tea,

Bread and margarine to eat,

War economy!...

Mummie does the house-work,

Can't get any maid,

Gone to make munitions,

'Cause they're better paid,

Nurse is always busy,

Never time to play,

Sewing shirts for soldiers,

Nearly ev'ry day.

Ev'ry body's doing

Something for the War,

Girls are doing things

They've never done before,

Go as 'bus conductors,

Drive a car or van,

All the world is topsy-turvy

Since the War began.

Nina MacDonald, “Sing a Song of War-Time,” https://allpoetry.com/poem/8620641-Sing-A-Song-of-War-Time-by-Nina-Macdonald.

Questions for Analysis:

Soldiers marching by,

Crowds of people standing,

Waving them 'Good-bye'.

When the crowds are over,

Home we go to tea,

Bread and margarine to eat,

War economy!...

Mummie does the house-work,

Can't get any maid,

Gone to make munitions,

'Cause they're better paid,

Nurse is always busy,

Never time to play,

Sewing shirts for soldiers,

Nearly ev'ry day.

Ev'ry body's doing

Something for the War,

Girls are doing things

They've never done before,

Go as 'bus conductors,

Drive a car or van,

All the world is topsy-turvy

Since the War began.

Nina MacDonald, “Sing a Song of War-Time,” https://allpoetry.com/poem/8620641-Sing-A-Song-of-War-Time-by-Nina-Macdonald.

Questions for Analysis:

- What were some of the things women were doing to support World War I?

- According to this poem, why were women supporting the WWI effort?

U.S. Food Administration Poster

Heroic Women of France toiling to produce food

"Does it be within the heart of the American people to hold to every convenience of our life and thus add an additional burden to the women of France?" -Alonso Taylor

"If we produce all we can, if we eat no more than our health demands, and if we waste nothing we will greatly lighten the load these noble women are carrying." -Herbert Hoover

"It means (food conservation) the utmost economy, even to the point where the pinch comes. It means the kind of concentration and self-sacrifice which is involved in the field of battle itself, where the object always looms greater than the individual." -Woodrow Wilson

Are you doing your part?

UNITED STATES FOOD ADMINISTRATION

Heroic women of France toiling to produce food Are you doing your part? United States, France, None. [New york: wynkoop hallenbeck crawford co., between 1917 and 1918] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/00652165/.

Questions for Analysis:

"Does it be within the heart of the American people to hold to every convenience of our life and thus add an additional burden to the women of France?" -Alonso Taylor

"If we produce all we can, if we eat no more than our health demands, and if we waste nothing we will greatly lighten the load these noble women are carrying." -Herbert Hoover

"It means (food conservation) the utmost economy, even to the point where the pinch comes. It means the kind of concentration and self-sacrifice which is involved in the field of battle itself, where the object always looms greater than the individual." -Woodrow Wilson

Are you doing your part?

UNITED STATES FOOD ADMINISTRATION

Heroic women of France toiling to produce food Are you doing your part? United States, France, None. [New york: wynkoop hallenbeck crawford co., between 1917 and 1918] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/00652165/.

Questions for Analysis:

- Why should women support the World War I effort, according to this image?

- How might this image have convinced women to join the World War I effort?

Christy Howard Chandler: Navy Recruitment Poster

Christy, Howard Chandler, Artist. Gee!! I wish I were a man, I'd join the Navy Be a man and do it - United States Navy recruiting station / / Howard Chandler Christy. United States, 1917. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2002712088/.

Questions for Analysis:

Questions for Analysis:

- According to this image, why might women have wanted to join the war effort?

- Although this advertisement was intended for men, how might it have helped women decide to join the war effort?

Frances Perkins: Speech

Frances Perkins was the first woman ever appointed to the President’s cabinet in US history. She was appointed Secretary of Labor, which was especially shocking considering the employment crisis that came along with the Great Depression. Perkins was one of the main reasons that the Social Security Administration was sustained through economic hardship and below is a speech regarding its success.

I must say I feel very much at home even though I just arrived. I feel at home because the Social Security Administration has, ever since it was established, been a sort of special concern of mine, although by the chicanery of politics it was not placed in the Department of Labor. I, of course, thought it should be.

As a matter of fact, one of the reasons I feel so deeply involved with the Social Security Administration is that even though it was not in the Department of Labor when it was first established, the Department of Labor had to carry it the way you carry a dependent child. It didn't have any money. That was so unfortunate. And we didn't have very much either. but we did, however, was to provide the Social Security Administration with offices in the Department of Labor Building. I even gave to the Chairman of the Social Security Board (as it was called in those days) the large, handsome, red-upholstered, high-back chair out of my own office so that he could look like a king. I didn't have to keep on looking like a queen. I found the chair somewhat uncomfortable so I made the sacrifice.

The whole Department did the same kind of thing. We gave them our best statisticians. We gave them the best of everything including Arthur Altmeyer, who was the Assistant Secretary of Labor and my real right hand, and without whom I felt very lost. It showed that we put our best people in there on loan, and we carried it for the first year and made it look like a going concern. In fact, it became a going concern in an extraordinarily short time.

When I asked what I was to speak about today, the suggestion was made I talk about the roots, or beginnings, of the Social Security Act. So I have thought about the roots. I suppose the roots--the idea that we ought to have a systematic method of taking care of the material needs of the aged--really springs from that deep well of charitableness which resides in the American people, and the efforts and the struggles of charity workers and social workers to handle the problems of people who were growing old and had no adequate means of support. Out of this impulse to be kind to the poor sprang, I suppose, a mulling of ideas about social insurance for the aged. But those people who were doing it didn't know that it was social insurance. They just kept thinking that something definite, something that people could look forward to, would be a great asset and a great assistance to them in their work. De Tocqueville, in his memoirs of his visit to America, mentioned what he thought was a unique state of mind of the American people: That they were so honestly concerned about their poor and did so much for them personally. It was not an organization; it was not a national action; it was not a State action; it was not Government. It was a personal action that De Tocqueville mentioned as being characteristic of the American people. They were so generous, so kind, so charitably disposed.

Well, I don't know anything about the times in which De Tocqueville visited America. That was long ago, and I know little about the psychological state of mind of the people of this country at that time. But I do know that at the time I came into the field of social work, these feelings were real. It was surprising what we were able to do through volunteer work--by the volunteer support of organizations who help the poor; and particularly the aged poor. Just look over the country At the old ladies' homes and the old couples' homes and the old members' homes that sprang up because aged people had necessities that had to be met. In each case, somebody got money together and established these homes. And life went on for the aged, after a fashion, as recipients of a kind of charity. These things have been going on for years.

Perkins, Frances. Speech. The Roots of Social Security. October 1963.

https://www.ssa.gov/history/perkins5.html.

Questions for Analysis:

I must say I feel very much at home even though I just arrived. I feel at home because the Social Security Administration has, ever since it was established, been a sort of special concern of mine, although by the chicanery of politics it was not placed in the Department of Labor. I, of course, thought it should be.

As a matter of fact, one of the reasons I feel so deeply involved with the Social Security Administration is that even though it was not in the Department of Labor when it was first established, the Department of Labor had to carry it the way you carry a dependent child. It didn't have any money. That was so unfortunate. And we didn't have very much either. but we did, however, was to provide the Social Security Administration with offices in the Department of Labor Building. I even gave to the Chairman of the Social Security Board (as it was called in those days) the large, handsome, red-upholstered, high-back chair out of my own office so that he could look like a king. I didn't have to keep on looking like a queen. I found the chair somewhat uncomfortable so I made the sacrifice.

The whole Department did the same kind of thing. We gave them our best statisticians. We gave them the best of everything including Arthur Altmeyer, who was the Assistant Secretary of Labor and my real right hand, and without whom I felt very lost. It showed that we put our best people in there on loan, and we carried it for the first year and made it look like a going concern. In fact, it became a going concern in an extraordinarily short time.

When I asked what I was to speak about today, the suggestion was made I talk about the roots, or beginnings, of the Social Security Act. So I have thought about the roots. I suppose the roots--the idea that we ought to have a systematic method of taking care of the material needs of the aged--really springs from that deep well of charitableness which resides in the American people, and the efforts and the struggles of charity workers and social workers to handle the problems of people who were growing old and had no adequate means of support. Out of this impulse to be kind to the poor sprang, I suppose, a mulling of ideas about social insurance for the aged. But those people who were doing it didn't know that it was social insurance. They just kept thinking that something definite, something that people could look forward to, would be a great asset and a great assistance to them in their work. De Tocqueville, in his memoirs of his visit to America, mentioned what he thought was a unique state of mind of the American people: That they were so honestly concerned about their poor and did so much for them personally. It was not an organization; it was not a national action; it was not a State action; it was not Government. It was a personal action that De Tocqueville mentioned as being characteristic of the American people. They were so generous, so kind, so charitably disposed.

Well, I don't know anything about the times in which De Tocqueville visited America. That was long ago, and I know little about the psychological state of mind of the people of this country at that time. But I do know that at the time I came into the field of social work, these feelings were real. It was surprising what we were able to do through volunteer work--by the volunteer support of organizations who help the poor; and particularly the aged poor. Just look over the country At the old ladies' homes and the old couples' homes and the old members' homes that sprang up because aged people had necessities that had to be met. In each case, somebody got money together and established these homes. And life went on for the aged, after a fashion, as recipients of a kind of charity. These things have been going on for years.

Perkins, Frances. Speech. The Roots of Social Security. October 1963.

https://www.ssa.gov/history/perkins5.html.

Questions for Analysis:

- What role does Frances Perkins take credit for in the founding and continuation of the administration?

- What does Perkins view the role of the Administration to be?

Remedial Herstory Editors. "15. WOMEN AND WORLD WAR I." The Remedial Herstory Project. November 20, 2022. www.remedialherstory.com.

Primary AUTHOR: |

Jacqui Nelson

|

Primary ReviewerS: |

Kelsie Brook Eckert

|

Consulting TeamKelsie Brook Eckert, Project Director

Coordinator of Social Studies Education at Plymouth State University Dr. Barbara Tischler, Consultant Professor of History Hunter College and Columbia University Dr. Alicia Gutierrez-Romine, Consultant Assistant Professor of History at La Sierra University Jacqui Nelson, Consultant Teaching Lecturer of Military History at Plymouth State University Dr. Deanna Beachley Professor of History and Women's Studies at College of Southern Nevada |

EditorsReviewersColonial

Dr. Margaret Huettl Hannah Dutton Dr. John Krueckeberg 19th Century Dr. Rebecca Noel Michelle Stonis, MA Annabelle L. Blevins Pifer, MA Cony Marquez, PhD Candidate 20th Century Dr. Tanya Roth Dr. Jessica Frazier Mary Bezbatchenko, MA Dr. Alicia Gutierrez-Romine Matthew Cerjak |

|

Into the Breach uses excerpts from diaries, memoirs, letters, and newspaper accounts to depict the experiences of wartime nurses, entertainers, canteen workers, interpreters, and journalists

|

The Curies’ newly discovered element of radium makes gleaming headlines across the nation as the fresh face of beauty, and wonder drug of the medical community. From body lotion to tonic water, the popular new element shines bright in the otherwise dark years of the First World War.

|

In 1916, at the height of World War I, brilliant Shakespeare expert Elizebeth Smith went to work for an eccentric tycoon on his estate outside Chicago. The tycoon had close ties to the U.S. government, and he soon asked Elizebeth to apply her language skills to an exciting new venture: code-breaking. Fagone unveils America’s code-breaking history through the prism of Smith’s life, bringing into focus the unforgettable events and colorful personalities that would help shape modern intelligence.

|

When World War I began, war reporting was a thoroughly masculine bastion of journalism. But that did not stop dozens of women reporters from stepping into the breach, defying gender norms and official restrictions to establish roles for themselves—and to write new kinds of narratives about women and war.

|

|

Inspired by real women, this powerful novel tells the story of two unconventional American sisters who volunteer at the front during World War I.

|

A group of young women from Smith College risk their lives in France at the height of World War I in this sweeping novel based on a true story—a skillful blend of Call the Midwife and The Alice Network—from New York Times bestselling author Lauren Willig.

|

December 1917. As World War I rages in Europe, twenty-four-year-old Ruby Wagner, the jewel in a prominent Philadelphia family, prepares for her upcoming wedding to a society scion. Like her life so far, it’s all been carefully arranged. But when her beloved older brother is killed in combat, Ruby follows her heart and answers the Army Signal Corps’ call for women operators to help overseas.

|

How to teach with Films:

Remember, teachers want the student to be the historian. What do historians do when they watch films?

- Before they watch, ask students to research the director and producers. These are the source of the information. How will their background and experience likely bias this film?

- Also, ask students to consider the context the film was created in. The film may be about history, but it was made recently. What was going on the year the film was made that could bias the film? In particular, how do you think the gains of feminism will impact the portrayal of the female characters?

- As they watch, ask students to research the historical accuracy of the film. What do online sources say about what the film gets right or wrong?

- Afterward, ask students to describe how the female characters were portrayed and what lessons they got from the film.

- Then, ask students to evaluate this film as a learning tool. Was it helpful to better understand this topic? Did the historical inaccuracies make it unhelpful? Make it clear any informed opinion is valid.

|

The Crimson Field (2014) takes place during the First World War as Kitty Trevelyan tries to put the past troubles behind her as she joins two other girls to volunteer at one of the busy war hospitals in northern France.

IMDB |

|

|

|

Bibliography

Alice Paul | Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University. (n.d.). Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University. https://www.radcliffe.harvard.edu/schlesinger-library/collections/alice-paul#:~:text=%E2%80%9CThere%20will%20never%20be%20a,Civil%20Rights%20Act%20of%201964.

Collins, Gail, America's Women: Four Hundred Years of Dolls, Drudges, Helpmates, and Heroines. New York, William Morrow, 2003.

DuBois, Ellen Carol, 1947-. Through Women's Eyes : an American History with Documents. Boston :Bedford/St. Martin's, 2005.Indians Editors. “NATIVE AMERICAN WOMEN.” Indians. N.D. http://indians.org/articles/Native-american-women.html.

Ware, Susan. American Women’s History: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

Wilson, W. (n.d.). Address to the Senate on the Nineteenth Amendment | The American Presidency Project. https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/address-the-senate-the-nineteenth-amendment

Women in World War I (U.S. National Park Service). (n.d.). https://www.nps.gov/articles/women-in-world-war-i.htm

Collins, Gail, America's Women: Four Hundred Years of Dolls, Drudges, Helpmates, and Heroines. New York, William Morrow, 2003.

DuBois, Ellen Carol, 1947-. Through Women's Eyes : an American History with Documents. Boston :Bedford/St. Martin's, 2005.Indians Editors. “NATIVE AMERICAN WOMEN.” Indians. N.D. http://indians.org/articles/Native-american-women.html.

Ware, Susan. American Women’s History: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

Wilson, W. (n.d.). Address to the Senate on the Nineteenth Amendment | The American Presidency Project. https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/address-the-senate-the-nineteenth-amendment

Women in World War I (U.S. National Park Service). (n.d.). https://www.nps.gov/articles/women-in-world-war-i.htm