4. Women's American Revolution

|

Women of all classes and races were not only supporters and opponents of the American Revolution, they actively promoted, engaged, wrote about, fought, and were deeply impacted by the outcome of the American Revolution. Their experiences were and perspectives were about as diverse as the women themselves.

Trigger Warning: for discussion of rape and sexual assault. |

|

Public Domain

Public Domain

Mention of the American Revolution evokes images of George Washington, Samuel Adams and the Sons of Liberty, Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and even Benedict Arnold long before it conjures up images of Deborah Sampson, Abigail Adams, or Mercy Otis Warren. While the leading figures of the Revolution became known as the Founding Fathers, history tends to ignore the Founding Mothers who fought right alongside them.

The American Revolution began in the wake of the Seven Years War, which ended in 1763. After 150 years of colonial growth, distance started to drive a wedge between the colonies and their mother country. Despite ample raw materials, increasing wealth, and a growing healthy population the English continued to treat Americans as second-class citizens. Though the colonists had been treated as equals during the Seven Years War, and had even felt more connected to their English roots because of the war, once the war ended, the English reverted to regarding the American colonists as subordinate and secondary. This was soon exacerbated by British efforts to control American trade, implement restrictions on settling Native lands, and taxation without representation in Parliament. As the various male-centric dissenters around the colonies slowly congregated into groups like the Sons of Liberty, and organized resistance, history seems to suggest that women retreated into the shadows.

The American Revolution began in the wake of the Seven Years War, which ended in 1763. After 150 years of colonial growth, distance started to drive a wedge between the colonies and their mother country. Despite ample raw materials, increasing wealth, and a growing healthy population the English continued to treat Americans as second-class citizens. Though the colonists had been treated as equals during the Seven Years War, and had even felt more connected to their English roots because of the war, once the war ended, the English reverted to regarding the American colonists as subordinate and secondary. This was soon exacerbated by British efforts to control American trade, implement restrictions on settling Native lands, and taxation without representation in Parliament. As the various male-centric dissenters around the colonies slowly congregated into groups like the Sons of Liberty, and organized resistance, history seems to suggest that women retreated into the shadows.

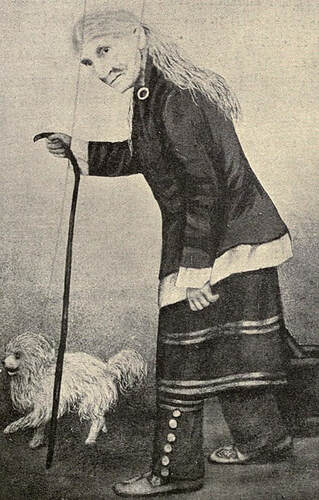

1892 Depiction of Jemison, Wikimedia Commons

1892 Depiction of Jemison, Wikimedia Commons

French and Indian War:

The American Revolution has its origins in the French and Indian War, also known as the Seven Years war in Europe. This war began over efforts to control the Ohio River Valley, the “frontier” at the time. West of the English colonies was a multicultural continent of French, Dutch, and English settlers and the Indigenous people whose ancestors had long inhabited these lands. The region was home to various Indigenous groups such as the Haudenosaunee, Wendat, Myaamia, Ho Chunk, Odawa, Potawatomi, Illinois, Meskwaki, Sauk, and others, each with distinct cultures and lifestyles. The mix of people from such diverse backgrounds, all claiming parts of the land in the Ohio River Valley for themselves, was bound to lead to tension. Some people, many times women, were caught bridging the gap between the French and Native communities, sometimes by force.

Women played a crucial role in the development and survival of frontier communities, often taking on multiple responsibilities. Women on the frontier were expected to contribute to the physical labor necessary for survival. They helped clear land, build houses and shelters, tend livestock, plant and harvest crops, fetch water, and gather firewood. These tasks required significant physical strength and endurance.

Frontier communities were closely-knit, and women played a crucial role in providing support to one another. They formed networks and cooperated with other women to share resources, knowledge, and childcare responsibilities. These relationships provided a sense of community and mutual assistance in the face of hardships.

In 1703, Esther Wheelwright lived with her family on the border of New France in a small Puritan, fur trading village. Esther was captured by Wabanaki and French forces retaliating for English encroachment on their land. In captivity, she was adopted by a Wabanaki family before being introduced to Catholicism by some French priests and eventually became a nun.

Marguerite Faffart was a métis, or mixed race, woman who lived in modern day Detroit. She was the daughter of a French trader and a French-Algonquin mother. Faffart was married to an abusive man who beat her and their young child. She fled to Pennsylvania where she was able to reconnect with her Algonquin family. Known as "French Margaret" among her British neighbors, she utilized her kinship and trade networks to sustain herself and her son through fur trading. At some point before 1735, she married Katarioniecha, a Mohawk man from Caughnawaga, thereby becoming part of another Native community and expanding her networks into the New York colony. Marguerite and Katarioniecha had four children.

In 1737, Faffart’s first husband died, leaving her a huge inheritance. She never returned to claim it, but her sister and brother-in-law fought for her in the Detroit courts. They won based on numerous witnesses to her husband's abuse– a rare court victory for women.

Tensions between powers on the frontier came to a head in the French and Indian war which officially began in 1756. The British wanted to secure control of the frontier. Indigenous people wanted their lands back, and the French wanted more control of the fur trade without British intervention.

During the French and Indian War, women played a crucial role in supporting the war effort and maintaining daily life on the homefront. They were responsible for managing households, ensuring the well-being of their families, and providing sustenance for both civilians and soldiers. Women worked tirelessly to maintain farms, produce essential goods, and care for the wounded. Their contributions to the logistical aspects of the war often went unrecognized, yet they played a vital role in sustaining the colonial forces.

Many women accompanied their husbands or male relatives to the front lines, providing nursing care, cooking, and even participating in combat when necessary. Some women took up arms themselves, disguising their gender to join the fight. These brave individuals defied societal norms and risked their lives for their cause, showing that gender did not restrict their dedication and bravery.

Women had access to critical information through their social networks and were able to gather intelligence and relay it to military leaders. Their abilities to navigate social circles and gather valuable data often proved instrumental in shaping military strategies and securing victories. Mary Jemison was a woman who profoundly influenced the course of the French and Indian War. Born in 1743 in Pennsylvania, Jemison was captured by a Shawnee war party during the conflict. Renamed Dehgewanus by the Seneca tribe, Jemison chose to assimilate into their society, learning their language, adopting their customs, and eventually marrying a Seneca man. Her intimate knowledge of both Native American and European cultures made her an invaluable resource for the Seneca tribe and the British forces.

Jemison's unique position allowed her to act as a mediator between the Seneca and the British, facilitating communication and negotiation. Her insights into the tactics, strategies, and intentions of the Native American tribes, as well as her familiarity with European military practices, proved invaluable to British military leaders. Jemison's efforts helped to establish trust, foster alliances, and ultimately shape the outcome of the war in favor of the British.

So why did a British victory lead the British colonists to rebel? There are a few reasons. The conclusion of the war coincided with a Proclamation that barred the settlers from further expansion west in an attempt to pacify indigenous people who faced encroachment. Since the English were able to oust the French from the disputed territory in the Ohio River Valley, the proclamation line alienated the English colonists who wanted to continue moving west. The French and Indian War was also incredibly expensive. Because the war cost the English lots of money and King George felt the colonists should be forced to pay for it. Colonists were taxed first through the Sugar Act of 1764. Its primary purpose was to raise revenue by imposing duties on sugar and other goods imported into the American colonies. The act replaced the earlier Molasses Act of 1733, which had been largely ineffective in curbing smuggling.

Under the Sugar Act, the duties on molasses were lowered, but stricter enforcement measures were implemented to crack down on smuggling. In other words, even though, on paper, the tax was lowered, enhanced anti-smuggling provisions meant that colonists were essentially paying this (lower) tax for the first time. Additionally, new duties were imposed on other goods like wine, coffee, textiles, and indigo. Collectively, these new taxes directly impacted the homes of women trying to provide for their families.

Additionally, the Stamp Act was passed by the British Parliament in March 1765. It was an internal tax that required the purchase of stamps for a wide range of paper goods, including legal documents, newspapers, pamphlets, playing cards, and even dice. The stamps had to be affixed to the designated items as proof of payment.

The Stamp Act was particularly controversial as it directly affected many colonists, including lawyers, printers, merchants, and the general public–particularly in areas where literacy rates were high. The act was met with widespread resistance in the American colonies, as it was seen as a direct infringement on their rights, without proper representation in the British government. The opposition eventually led to organized protests, boycotts, and the formation of the Stamp Act Congress, which called for the repeal of the Act.

The American Revolution has its origins in the French and Indian War, also known as the Seven Years war in Europe. This war began over efforts to control the Ohio River Valley, the “frontier” at the time. West of the English colonies was a multicultural continent of French, Dutch, and English settlers and the Indigenous people whose ancestors had long inhabited these lands. The region was home to various Indigenous groups such as the Haudenosaunee, Wendat, Myaamia, Ho Chunk, Odawa, Potawatomi, Illinois, Meskwaki, Sauk, and others, each with distinct cultures and lifestyles. The mix of people from such diverse backgrounds, all claiming parts of the land in the Ohio River Valley for themselves, was bound to lead to tension. Some people, many times women, were caught bridging the gap between the French and Native communities, sometimes by force.

Women played a crucial role in the development and survival of frontier communities, often taking on multiple responsibilities. Women on the frontier were expected to contribute to the physical labor necessary for survival. They helped clear land, build houses and shelters, tend livestock, plant and harvest crops, fetch water, and gather firewood. These tasks required significant physical strength and endurance.

Frontier communities were closely-knit, and women played a crucial role in providing support to one another. They formed networks and cooperated with other women to share resources, knowledge, and childcare responsibilities. These relationships provided a sense of community and mutual assistance in the face of hardships.

In 1703, Esther Wheelwright lived with her family on the border of New France in a small Puritan, fur trading village. Esther was captured by Wabanaki and French forces retaliating for English encroachment on their land. In captivity, she was adopted by a Wabanaki family before being introduced to Catholicism by some French priests and eventually became a nun.

Marguerite Faffart was a métis, or mixed race, woman who lived in modern day Detroit. She was the daughter of a French trader and a French-Algonquin mother. Faffart was married to an abusive man who beat her and their young child. She fled to Pennsylvania where she was able to reconnect with her Algonquin family. Known as "French Margaret" among her British neighbors, she utilized her kinship and trade networks to sustain herself and her son through fur trading. At some point before 1735, she married Katarioniecha, a Mohawk man from Caughnawaga, thereby becoming part of another Native community and expanding her networks into the New York colony. Marguerite and Katarioniecha had four children.

In 1737, Faffart’s first husband died, leaving her a huge inheritance. She never returned to claim it, but her sister and brother-in-law fought for her in the Detroit courts. They won based on numerous witnesses to her husband's abuse– a rare court victory for women.

Tensions between powers on the frontier came to a head in the French and Indian war which officially began in 1756. The British wanted to secure control of the frontier. Indigenous people wanted their lands back, and the French wanted more control of the fur trade without British intervention.

During the French and Indian War, women played a crucial role in supporting the war effort and maintaining daily life on the homefront. They were responsible for managing households, ensuring the well-being of their families, and providing sustenance for both civilians and soldiers. Women worked tirelessly to maintain farms, produce essential goods, and care for the wounded. Their contributions to the logistical aspects of the war often went unrecognized, yet they played a vital role in sustaining the colonial forces.

Many women accompanied their husbands or male relatives to the front lines, providing nursing care, cooking, and even participating in combat when necessary. Some women took up arms themselves, disguising their gender to join the fight. These brave individuals defied societal norms and risked their lives for their cause, showing that gender did not restrict their dedication and bravery.

Women had access to critical information through their social networks and were able to gather intelligence and relay it to military leaders. Their abilities to navigate social circles and gather valuable data often proved instrumental in shaping military strategies and securing victories. Mary Jemison was a woman who profoundly influenced the course of the French and Indian War. Born in 1743 in Pennsylvania, Jemison was captured by a Shawnee war party during the conflict. Renamed Dehgewanus by the Seneca tribe, Jemison chose to assimilate into their society, learning their language, adopting their customs, and eventually marrying a Seneca man. Her intimate knowledge of both Native American and European cultures made her an invaluable resource for the Seneca tribe and the British forces.

Jemison's unique position allowed her to act as a mediator between the Seneca and the British, facilitating communication and negotiation. Her insights into the tactics, strategies, and intentions of the Native American tribes, as well as her familiarity with European military practices, proved invaluable to British military leaders. Jemison's efforts helped to establish trust, foster alliances, and ultimately shape the outcome of the war in favor of the British.

So why did a British victory lead the British colonists to rebel? There are a few reasons. The conclusion of the war coincided with a Proclamation that barred the settlers from further expansion west in an attempt to pacify indigenous people who faced encroachment. Since the English were able to oust the French from the disputed territory in the Ohio River Valley, the proclamation line alienated the English colonists who wanted to continue moving west. The French and Indian War was also incredibly expensive. Because the war cost the English lots of money and King George felt the colonists should be forced to pay for it. Colonists were taxed first through the Sugar Act of 1764. Its primary purpose was to raise revenue by imposing duties on sugar and other goods imported into the American colonies. The act replaced the earlier Molasses Act of 1733, which had been largely ineffective in curbing smuggling.

Under the Sugar Act, the duties on molasses were lowered, but stricter enforcement measures were implemented to crack down on smuggling. In other words, even though, on paper, the tax was lowered, enhanced anti-smuggling provisions meant that colonists were essentially paying this (lower) tax for the first time. Additionally, new duties were imposed on other goods like wine, coffee, textiles, and indigo. Collectively, these new taxes directly impacted the homes of women trying to provide for their families.

Additionally, the Stamp Act was passed by the British Parliament in March 1765. It was an internal tax that required the purchase of stamps for a wide range of paper goods, including legal documents, newspapers, pamphlets, playing cards, and even dice. The stamps had to be affixed to the designated items as proof of payment.

The Stamp Act was particularly controversial as it directly affected many colonists, including lawyers, printers, merchants, and the general public–particularly in areas where literacy rates were high. The act was met with widespread resistance in the American colonies, as it was seen as a direct infringement on their rights, without proper representation in the British government. The opposition eventually led to organized protests, boycotts, and the formation of the Stamp Act Congress, which called for the repeal of the Act.

Phyllis Wheatley, Library of Congress

Phyllis Wheatley, Library of Congress

Women were involved in resistance from the very beginning. Women ran taverns which provided a safe place for rebels to meet, discuss ideas, and plan their protests. Women were also immediately recruited by the Sons of Liberty and others to serve as spies as tensions mounted closer to war. Seamstresses, servants, laundresses, and caregivers in the homes of loyalists and British officials were called on to provide information that proved critical to protecting rebels from the earliest protests through the greatest battles of the war.

We also cannot deny that many Americans opposed the rebellion, and many loyalist women sought to support the war effort on the British side as well. Women were at the forefront of defining what America was, and what it meant to be included among her people. Phillis Wheatley became the first African American author of published poetry in 1773, which eventually led to her emancipation from slavery. She would write controversial poems challenging the system of slavery, poems commending George Washington, and during the rebellion, described the dissolving relationship between mother country and her colonies:

“A certain lady had an only son

He grew up daily virtuous as he grew

Fearing his Strength which she undoubted knew

She laid some taxes on her darling son

And would have laid another act there on

Amend your manners I’ll the task remove

Was said with seeming Sympathy and Love

By many Scourges she his goodness try’d”

In other words, Britain was saying “I’m doing this for you,” but deep down, she was continuing to test American’s good nature.

We also cannot deny that many Americans opposed the rebellion, and many loyalist women sought to support the war effort on the British side as well. Women were at the forefront of defining what America was, and what it meant to be included among her people. Phillis Wheatley became the first African American author of published poetry in 1773, which eventually led to her emancipation from slavery. She would write controversial poems challenging the system of slavery, poems commending George Washington, and during the rebellion, described the dissolving relationship between mother country and her colonies:

“A certain lady had an only son

He grew up daily virtuous as he grew

Fearing his Strength which she undoubted knew

She laid some taxes on her darling son

And would have laid another act there on

Amend your manners I’ll the task remove

Was said with seeming Sympathy and Love

By many Scourges she his goodness try’d”

In other words, Britain was saying “I’m doing this for you,” but deep down, she was continuing to test American’s good nature.

Mercy Otis Warren, Library of Congress

Mercy Otis Warren, Library of Congress

Likewise, Mercy Otis Warren was an outspoken patriot. Having been surrounded by politics her whole life, she regularly debated political leaders and wrote several plays calling out the wrongdoings of Britain and their royal officials years before the war broke out. She was willing to say “independence” far before the male representatives of her time and was brazen in her literary assault on the King. She was also unafraid to criticize military officers and the Continental Congress during the war. She seemed unafraid to take on anyone, as she wrote, “Great advantages are often attended with great inconveniences, and great minds called to severe trials.” She would also go on to write and publish the first history of the Revolution, the first nonfiction book published by a woman in America.

The intellectual pursuits of these women and the ideas they presented were not only important leading up to the war and throughout the conflict, but they also raised questions about women’s rights.

The intellectual pursuits of these women and the ideas they presented were not only important leading up to the war and throughout the conflict, but they also raised questions about women’s rights.

A Society of Patriotic Ladies (notice the dog), Library of Congress

A Society of Patriotic Ladies (notice the dog), Library of Congress

Some women bonded together to match their written words with action. Society at the time did not expect, or often allow, women to play a prominent role in these more direct forms of protest. Instead, they were called on to take more dignified paths. Penelope Barker and over fifty women from the city of Edenton, North Carolina, would do exactly that. They would mail a letter signed by each of their party indicating that they would boycott British tea and cloth until a resolution was reached between Parliament and the newly formed Continental Congress.

The British press had a good laugh at these patriotic ladies, but the Virginia Gazette heaped on the praise. While this event would not receive the historic attention of the Boston Tea Party, these women gathered to voice their concerns to Parliament.

When Americans were called upon to start boycotting British goods, women stepped in to produce these goods.. Daughters of Liberty groups gathered to spin wool to make their own textiles (where we get the term “home-spun”). They learned to make tea with American herbs, which they called Liberty Tea. Also, doing the majority of the shopping for their home, they held up the mantle of boycotting British manufactured goods as well. Even popular culture at the time understood women’s vital role in economic boycotts. A popular song before the American Revolution was improvised to explain the importance of homespun–not imported–textiles and goods. Several versions of the song exist, but most of them highlight how it was patriotic for women to wear homespun goods. It’s a bit ironic that the song would say “No more ribbands wear, nor in rich dress appear/Love your country much better than fine things.” On one hand, the song is appealing to women’s sense of patriotism in America–a place where they are not considered citizens. At the same time, the song later reassures women that they will still be found attractive–which also suggests perhaps that the songwriter believes American women are apolitical and only interested in fashion and beauty. Either way, what is clear is that women’s participation in these boycotts constituted political action.

We also can’t forget that women were used as pawns in war too. Namely, they became propaganda. This happens regularly throughout periods of war, where societies paint a message of men needing to protect women from their enemy.

The British press had a good laugh at these patriotic ladies, but the Virginia Gazette heaped on the praise. While this event would not receive the historic attention of the Boston Tea Party, these women gathered to voice their concerns to Parliament.

When Americans were called upon to start boycotting British goods, women stepped in to produce these goods.. Daughters of Liberty groups gathered to spin wool to make their own textiles (where we get the term “home-spun”). They learned to make tea with American herbs, which they called Liberty Tea. Also, doing the majority of the shopping for their home, they held up the mantle of boycotting British manufactured goods as well. Even popular culture at the time understood women’s vital role in economic boycotts. A popular song before the American Revolution was improvised to explain the importance of homespun–not imported–textiles and goods. Several versions of the song exist, but most of them highlight how it was patriotic for women to wear homespun goods. It’s a bit ironic that the song would say “No more ribbands wear, nor in rich dress appear/Love your country much better than fine things.” On one hand, the song is appealing to women’s sense of patriotism in America–a place where they are not considered citizens. At the same time, the song later reassures women that they will still be found attractive–which also suggests perhaps that the songwriter believes American women are apolitical and only interested in fashion and beauty. Either way, what is clear is that women’s participation in these boycotts constituted political action.

We also can’t forget that women were used as pawns in war too. Namely, they became propaganda. This happens regularly throughout periods of war, where societies paint a message of men needing to protect women from their enemy.

Paul Revere's propaganda using women to gain sympathy, Library of Congress

Paul Revere's propaganda using women to gain sympathy, Library of Congress

We can see this early in the Revolution. In the days after the Boston Massacre in 1770, Paul Revere and Henry Pelham’s engraving of the event spread far and wide through colonial newspapers. There are many, many inaccuracies of the image, each was hand-picked to spread a message about America’s innocence in the event.

The British soldiers appear to be firing into a completely unassuming crowd. The figure of the woman standing clearly in the midst of the crowd was not meant to show that women were involved in the scuffle that made the Revolution inevitable, but rather to make America seem to be the undeniable victims. Presumably, the presence of a woman in the protest would have ensured that it was peaceful and respectful, while her presence also suggested that the British’s actions were especially depraved.

Fighting eventually broke out at Lexington and Concord and around the English colonies. Sybil Ludington, a sixteen year old girl, took a ride just as daring as Paul Revere’s and more than double the distance, to warn the militias of New York and Connecticut that British invaders were on their way. After the war, General George Washington personally thanked her for her service.

The British soldiers appear to be firing into a completely unassuming crowd. The figure of the woman standing clearly in the midst of the crowd was not meant to show that women were involved in the scuffle that made the Revolution inevitable, but rather to make America seem to be the undeniable victims. Presumably, the presence of a woman in the protest would have ensured that it was peaceful and respectful, while her presence also suggested that the British’s actions were especially depraved.

Fighting eventually broke out at Lexington and Concord and around the English colonies. Sybil Ludington, a sixteen year old girl, took a ride just as daring as Paul Revere’s and more than double the distance, to warn the militias of New York and Connecticut that British invaders were on their way. After the war, General George Washington personally thanked her for her service.

As men joined militias and headed off to war, gender norms were disrupted and women assumed responsibilities managing businesses and farms. This also left some women vulnerable. A South Carolina woman, Eliza Pickney, described her situation, “my property pulled into pieces, burnt and destroyed; my money of no value, my Children sick and prisoners.” Women were also attacked and raped at home by Tory and British soldiers as they came through.

The home front was dangerous for women, but many women did not despair. Abigail Adams wrote, “We possess a spirit that will not be conquered. If our Men are drawn off and we should be attacked, you will find a Race of Amazons in America.” She turned her home into a hospital during the war and did whatever she could to keep up morale at home.

The home front was dangerous for women, but many women did not despair. Abigail Adams wrote, “We possess a spirit that will not be conquered. If our Men are drawn off and we should be attacked, you will find a Race of Amazons in America.” She turned her home into a hospital during the war and did whatever she could to keep up morale at home.

Jane McCrea's Death, Public Domain

Jane McCrea's Death, Public Domain

Martha Washington was a wealthy woman, inheriting a great deal of money from her first husband. During the war, she maintained her elaborate estates and bankrolled the war effort. Every winter, when the war was stalemated, she would travel, like a lot of wives would, to be with Washington in the camps. Washington and other prominent women began a campaign to America's women to collect direct aid for soldiers in the Continental Army. Mount Vernon records show that Martha herself donated $20,000.

As the British stomped their way through upstate New York, young Jane McCrea, met her untimely end. Engaged to a loyalist officer who had rushed off to serve, McCrea was making her way toward him when she was abducted and killed. While there is much debate about her killers, the blame was placed on General John Burgoyne’s Native scouts. Jane became a tool for the Patriots.

The message was spread among the communities that Jane had been one of their own. If Burgoyne would allow that to happen and let her killers go unpunished, to a loyalist woman, moreover one of his own officer’s fiancés, what would he do to your wife, fiancé, daughter, or sister, when he came through?

This takes a political war into the realm of a moral or ethical one. The women needed protection from the British brute!

As the British stomped their way through upstate New York, young Jane McCrea, met her untimely end. Engaged to a loyalist officer who had rushed off to serve, McCrea was making her way toward him when she was abducted and killed. While there is much debate about her killers, the blame was placed on General John Burgoyne’s Native scouts. Jane became a tool for the Patriots.

The message was spread among the communities that Jane had been one of their own. If Burgoyne would allow that to happen and let her killers go unpunished, to a loyalist woman, moreover one of his own officer’s fiancés, what would he do to your wife, fiancé, daughter, or sister, when he came through?

This takes a political war into the realm of a moral or ethical one. The women needed protection from the British brute!

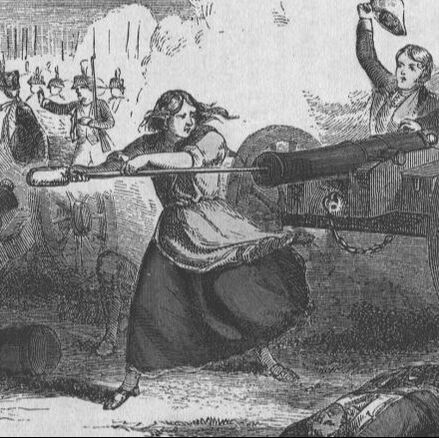

Molly Pitcher, Library of Congress

Molly Pitcher, Library of Congress

Molly Pitcher:

Let’s also remember that women were certainly not absent from the war itself. We’ve already discussed their roles as spies, and very often, the wives of officers and some women looking for work traveled with the army, known as “camp followers”. They cooked, cleaned, and cared for the men. They were often kept far to the rear to protect them from the battlefield, but this doesn’t mean they always stayed there.

Molly Pitcher was one such camp follower who is famed for having operated a cannon in the place of her husband, who was killed in the line of duty.

Some mystery sounds the story of Molly Pitcher. Many claim it was Mary Hays, who was a camp follower of her husband William. She stayed with him at Valley Forge, and in the summer after, was with him at the Battle of Monmouth Courthouse. When he died, she had been delivering pitchers of water to the men, and immediately jumped in his place. She took on the role of swabbing and reloading the cannon, supposedly even earning Washington’s attention.

Others claim this was really Molly Corbin at Fort Washington, where she, like Hays, stepped into her husband’s place fighting against the attacking Hessians until she was wounded in the arm. She was awarded a monthly pension from the state of Pennsylvania for her heroism; the first American woman to be awarded such a military honor.

As to who the real “Molly Pitcher” is, we can only guess. These two women are the best recognized, but likely dozens of women took on similar positions at some point in the war. The legend really became a composite of all of them. Thus, Molly Pitcher is just a singular figure that is meant to represent multiple women who took on the British in the heat of battle.

Let’s also remember that women were certainly not absent from the war itself. We’ve already discussed their roles as spies, and very often, the wives of officers and some women looking for work traveled with the army, known as “camp followers”. They cooked, cleaned, and cared for the men. They were often kept far to the rear to protect them from the battlefield, but this doesn’t mean they always stayed there.

Molly Pitcher was one such camp follower who is famed for having operated a cannon in the place of her husband, who was killed in the line of duty.

Some mystery sounds the story of Molly Pitcher. Many claim it was Mary Hays, who was a camp follower of her husband William. She stayed with him at Valley Forge, and in the summer after, was with him at the Battle of Monmouth Courthouse. When he died, she had been delivering pitchers of water to the men, and immediately jumped in his place. She took on the role of swabbing and reloading the cannon, supposedly even earning Washington’s attention.

Others claim this was really Molly Corbin at Fort Washington, where she, like Hays, stepped into her husband’s place fighting against the attacking Hessians until she was wounded in the arm. She was awarded a monthly pension from the state of Pennsylvania for her heroism; the first American woman to be awarded such a military honor.

As to who the real “Molly Pitcher” is, we can only guess. These two women are the best recognized, but likely dozens of women took on similar positions at some point in the war. The legend really became a composite of all of them. Thus, Molly Pitcher is just a singular figure that is meant to represent multiple women who took on the British in the heat of battle.

Molly Pitcher, Library of Congress

Molly Pitcher, Library of Congress

Mammy Kate was an enslaved woman who worked on Stephen Heard’s, the future Governor of Georgia, plantation. When he was captured and held prisoner during the American Revolution, Mammy Kate infiltrated and smuggled him out. She was the first Black woman to be honored as a patriot of the American Revolution in the state of Georgia.

Then, there is Deborah Sampson Gannett.

Sampson was born into poverty, and struggled through most of her early life, serving as an indentured servant, teacher, weaver, and more. The Revolutionary War raged through her late teens, and at twenty-one, in the war’s waning years, she jumped at the opportunity for regular pay. She joined a Massachusetts regiment under the alias of Robert Shurtleff, not only a scandalous move, but an illegal one given Massachusetts laws against women dressing as men.

She was ushered off to West Point where she served in the light infantry, constantly on the move, scouting, and skirmishing. In one nasty engagement, she was slashed across the forehead with a saber, and shot twice in the leg. She let her forehead wound be tended to at a field hospital, and then ran back to her tent to dig out the two iron balls and stitch up her wounds herself to avoid being caught. She served for over a year and half before she was finally caught at the very end of the war. She would eventually successfully lobby for a federal soldier’s pension in return for her service.

Then, there is Deborah Sampson Gannett.

Sampson was born into poverty, and struggled through most of her early life, serving as an indentured servant, teacher, weaver, and more. The Revolutionary War raged through her late teens, and at twenty-one, in the war’s waning years, she jumped at the opportunity for regular pay. She joined a Massachusetts regiment under the alias of Robert Shurtleff, not only a scandalous move, but an illegal one given Massachusetts laws against women dressing as men.

She was ushered off to West Point where she served in the light infantry, constantly on the move, scouting, and skirmishing. In one nasty engagement, she was slashed across the forehead with a saber, and shot twice in the leg. She let her forehead wound be tended to at a field hospital, and then ran back to her tent to dig out the two iron balls and stitch up her wounds herself to avoid being caught. She served for over a year and half before she was finally caught at the very end of the war. She would eventually successfully lobby for a federal soldier’s pension in return for her service.

Madam Sacho, Public Domain

Madam Sacho, Public Domain

Native Americans:

For Native Americans the war was incredibly complicated. They had to hedge their bets on which side they believed would have favorable policies towards them following the war. The British had an advantage as their policies limiting white encroachment on Native lands were one of the catalysts for war. But some nations did side with the Patriots.

The war split up the Iroquois, or Haudenosaunee , Confederacy. Haudenosaunee women played a deciding role in issues of war, peace, captivity, and death. One French man declared, “it is the women who really make up the Nation. . . . All the real authority rests in the women.”

Most of the Confederacy sided with the British but had little interest in joining what they saw as a family affair between Europeans. Konwat-sits-ia-ienni, or Molly Brant urged her nation to support the British cause, resulting in a series of raids in New York that hurt the Patriots. Haudenosaunee warriors attacked settlements, killing men, women and children, in retaliation for ill treatment. One Patriot captain wrote, “Such a shocking sight my eyes never held before of savage and brutal barbarity; to see the husband mourning over his dead wife and four dead children lying by her side, mangled, scalpt.”

In retaliation, General Washington planned to raid Native villages stealing away the women and luring the warriors out. They employed scorched earth warfare tactics setting afire crops, fruit trees, and longhouses. Women, children, and the elderly were murdered.

But when they came to one village they found it abandoned save for an old woman known as Madam Sacho. The woman reported to them that her people had debated whether to surrender, and decided not to. It’s possible her age garnered some of the soldiers’ sympathy. It’s also possible she was incredibly wise, but the soldiers left her alive. When they came back through, another Native woman was found dead, shot and probably raped by Patriot soldiers.

Why was Madam Sacho left alone in her village when the rest of the community departed? Where did the rest of her village go? Soldiers couldn’t track them. Did Madam Sacho give him bad information to give her people more time to get away? And why was the young woman who returned to care for Madam Sacho murdered?

For Native Americans the war was incredibly complicated. They had to hedge their bets on which side they believed would have favorable policies towards them following the war. The British had an advantage as their policies limiting white encroachment on Native lands were one of the catalysts for war. But some nations did side with the Patriots.

The war split up the Iroquois, or Haudenosaunee , Confederacy. Haudenosaunee women played a deciding role in issues of war, peace, captivity, and death. One French man declared, “it is the women who really make up the Nation. . . . All the real authority rests in the women.”

Most of the Confederacy sided with the British but had little interest in joining what they saw as a family affair between Europeans. Konwat-sits-ia-ienni, or Molly Brant urged her nation to support the British cause, resulting in a series of raids in New York that hurt the Patriots. Haudenosaunee warriors attacked settlements, killing men, women and children, in retaliation for ill treatment. One Patriot captain wrote, “Such a shocking sight my eyes never held before of savage and brutal barbarity; to see the husband mourning over his dead wife and four dead children lying by her side, mangled, scalpt.”

In retaliation, General Washington planned to raid Native villages stealing away the women and luring the warriors out. They employed scorched earth warfare tactics setting afire crops, fruit trees, and longhouses. Women, children, and the elderly were murdered.

But when they came to one village they found it abandoned save for an old woman known as Madam Sacho. The woman reported to them that her people had debated whether to surrender, and decided not to. It’s possible her age garnered some of the soldiers’ sympathy. It’s also possible she was incredibly wise, but the soldiers left her alive. When they came back through, another Native woman was found dead, shot and probably raped by Patriot soldiers.

Why was Madam Sacho left alone in her village when the rest of the community departed? Where did the rest of her village go? Soldiers couldn’t track them. Did Madam Sacho give him bad information to give her people more time to get away? And why was the young woman who returned to care for Madam Sacho murdered?

Enslaved women with their children, Public Domain

Enslaved women with their children, Public Domain

Enslaved Women:

For enslaved Americans the Revolution presented a potential opportunity and they took advantage of it. They fought for both sides, whichever would ensure their freedom. The Virginia Governor issued Dunmore’s Proclamation guaranteeing freedom to any enslaved person who abandoned their Patriot owners and aided the British cause. Although the proclamation only applied to Virginia, it was printed throughout the colonies. In 1777, Vermont became the first colony to abolish slavery, providing safe haven for fugitive slaves.

Enslaved women’s desire for freedom for themselves and their children propelled them to flee from slavery during the Revolutionary War. The war disrupted the normal routine on plantations and lack of oversight allowed enslaved people to discuss freedom more seriously. One-third of all fugitives were enslaved women.

Margaret, Sarah, and Jenny were all enslaved women who fled bondage during the war. They knew they were worth more than the dollar amount put to them, what some referred to as their “Soul Value.”

Sarah was pregnant and ran away with her six-year old son. Her husband had joined the British Army and she intended to try and “pass” as free to join him. Jenny fled at eight months pregnant. Her enslaver advertised widely for her return. But Jenny had heard of Dunmore’s Proclamation and had spent months planning her escape. Enslaved women also made similar claims about their husbands being in the Continental Army. In a Runaway Slave advertisement in The New Jersey Gazette, one enslaver in 1778 offered compensation for the return of his runaway “Sarah.” He claimed the “mulatto” woman now called herself Rachael, and that she was “big with child” and had run off with her son, “a Mulatto boy named Bob, about six years old.” According to the advertisement, she had been last seen near “the first Maryland regiment, where she pretends to have a husband, with whom she has been the principal part of this compaign, and passed herself as a free woman.” These women knew that whatever the outcome of the war, their newborns would be enslaved and they couldn’t let that happen.

Elizabeth Freeman, or Mum Bett, was an enslaved woman in Massachusetts. Her husband died fighting the war. Throughout the war she had listened to the wealthy white people she served discuss concepts of freedom and liberty and decided this Enlightened philosophy should apply to her too. One day she was beaten by her mistress, which proved to be a catalyst to make demands. She fled, finding refuge with a white lawyer who helped her sue for her freedom.

For enslaved Americans the Revolution presented a potential opportunity and they took advantage of it. They fought for both sides, whichever would ensure their freedom. The Virginia Governor issued Dunmore’s Proclamation guaranteeing freedom to any enslaved person who abandoned their Patriot owners and aided the British cause. Although the proclamation only applied to Virginia, it was printed throughout the colonies. In 1777, Vermont became the first colony to abolish slavery, providing safe haven for fugitive slaves.

Enslaved women’s desire for freedom for themselves and their children propelled them to flee from slavery during the Revolutionary War. The war disrupted the normal routine on plantations and lack of oversight allowed enslaved people to discuss freedom more seriously. One-third of all fugitives were enslaved women.

Margaret, Sarah, and Jenny were all enslaved women who fled bondage during the war. They knew they were worth more than the dollar amount put to them, what some referred to as their “Soul Value.”

Sarah was pregnant and ran away with her six-year old son. Her husband had joined the British Army and she intended to try and “pass” as free to join him. Jenny fled at eight months pregnant. Her enslaver advertised widely for her return. But Jenny had heard of Dunmore’s Proclamation and had spent months planning her escape. Enslaved women also made similar claims about their husbands being in the Continental Army. In a Runaway Slave advertisement in The New Jersey Gazette, one enslaver in 1778 offered compensation for the return of his runaway “Sarah.” He claimed the “mulatto” woman now called herself Rachael, and that she was “big with child” and had run off with her son, “a Mulatto boy named Bob, about six years old.” According to the advertisement, she had been last seen near “the first Maryland regiment, where she pretends to have a husband, with whom she has been the principal part of this compaign, and passed herself as a free woman.” These women knew that whatever the outcome of the war, their newborns would be enslaved and they couldn’t let that happen.

Elizabeth Freeman, or Mum Bett, was an enslaved woman in Massachusetts. Her husband died fighting the war. Throughout the war she had listened to the wealthy white people she served discuss concepts of freedom and liberty and decided this Enlightened philosophy should apply to her too. One day she was beaten by her mistress, which proved to be a catalyst to make demands. She fled, finding refuge with a white lawyer who helped her sue for her freedom.

Elizabeth Freeman (Mum Bett), Library of Congress

Elizabeth Freeman (Mum Bett), Library of Congress

In Brom & Bett v. Ashley the jury ruled in her favor and ordered her former owners to pay her. Her case ultimately led to the abolition of slavery in Massachusetts just before the close of the American Revolution. Soon every northern state would abolish slavery; however, the abolition of slavery in the North was slow and gradual in order to mitigate the effects of the loss of property for the enslavers. As a result, the Revolution left a complicated legacy for Black people, as slavery still existed and persisted for decades in the North as it did in the South. Black women’s freedom cannot be disentangled from the story of American independence. These women monitored the war and were heavily affected by the outcome.

Revolutionary debates among white men about freedom and liberty absolutely included discussions of abolition, but they tabled the discussion for another generation – preferring union over freedom. How different might that discussion have been if women, all women, were included?

At least when Mum Bett died in 1829, she was a free woman. Her inspirational story didn’t end with her, though. One of her great-grandchildren was W.E.B. DuBois, the first Black man to graduate from Harvard and a founder of the NAACP.

Revolutionary debates among white men about freedom and liberty absolutely included discussions of abolition, but they tabled the discussion for another generation – preferring union over freedom. How different might that discussion have been if women, all women, were included?

At least when Mum Bett died in 1829, she was a free woman. Her inspirational story didn’t end with her, though. One of her great-grandchildren was W.E.B. DuBois, the first Black man to graduate from Harvard and a founder of the NAACP.

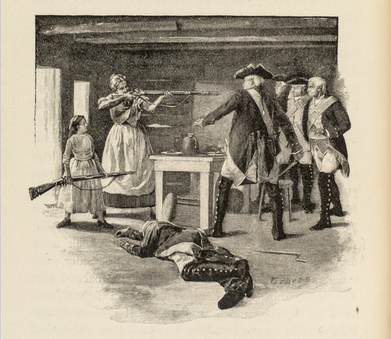

Nancy Hart, Library of Congress

Nancy Hart, Library of Congress

Revolutionary?:

Was the American Revolution truly revolutionary? Even white women were let down by limits of the Revolution’s revolutionary rhetoric. Maybe the most famous of Revolutionary women, Abigail Adams, wife of John Adams, was not only his closest advisor, but also one of the few women who became known as a founder of the nation. The letters they exchanged during his time in Congress, serving as a diplomat overseas, and even during the Constitutional Convention show his reliance on her advice and her contributions to major affairs. Most famously, during the Constitutional Convention, she would ask her husband and the other delegates to "remember the ladies, and be more generous and favorable to them than your ancestors. Do not put such unlimited power into the hands of the Husbands. Remember all Men would be tyrants if they could. If particular care and attention is not paid to the Ladies we are determined to foment a Rebellion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any Laws in which we have no voice, or Representation." In other words, she encouraged her husband to not create a government where women were ruled by their husbands as the patriots had been ruled by the King. Otherwise, the ladies will stand up for themselves, just the way Americans did against a government that didn’t represent them. John’s response was, “I cannot but laugh.” She would take her time in writing back and it would take over a century for her warned rebellion to happen, but the women of America held true to Abigail’s warning.

Was the American Revolution truly revolutionary? Even white women were let down by limits of the Revolution’s revolutionary rhetoric. Maybe the most famous of Revolutionary women, Abigail Adams, wife of John Adams, was not only his closest advisor, but also one of the few women who became known as a founder of the nation. The letters they exchanged during his time in Congress, serving as a diplomat overseas, and even during the Constitutional Convention show his reliance on her advice and her contributions to major affairs. Most famously, during the Constitutional Convention, she would ask her husband and the other delegates to "remember the ladies, and be more generous and favorable to them than your ancestors. Do not put such unlimited power into the hands of the Husbands. Remember all Men would be tyrants if they could. If particular care and attention is not paid to the Ladies we are determined to foment a Rebellion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any Laws in which we have no voice, or Representation." In other words, she encouraged her husband to not create a government where women were ruled by their husbands as the patriots had been ruled by the King. Otherwise, the ladies will stand up for themselves, just the way Americans did against a government that didn’t represent them. John’s response was, “I cannot but laugh.” She would take her time in writing back and it would take over a century for her warned rebellion to happen, but the women of America held true to Abigail’s warning.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

The Revolutionary War spread far beyond the battlefields, affecting the American people, their economy, and their lives in many unanticipated ways. The war would come to an end in the fall of 1783. While the men would be lauded for their efforts to bring America its independence, history quickly forgot the diverse women who also made that possible. The Sampsons and Pitchers on the battlefield; the Otis’, Adams’, and Wheatleys using their intellect, and the thousands of unnamed Native, Black, and rebel women serving as Daughters of Liberty, working behind the scenes as spies and soldiers, or those many uncelebrated women who kept their family farms, businesses, and trades alive while their husbands, fathers, and sons left for war.

This period is such an important part of American History, but women’s roles are often underrepresented in lieu of the images of tradesmen and farmers dropping the tools of the trade to fix bayonets and fight England. There is so much room for growth.What ways did women contribute to the rebellion and war effort? How are women’s contributions rewarded or ignored after the war’s conclusion? How did women’s roles inspire future generations in their pursuit of greater rights and recognition from the government they helped form?

This period is such an important part of American History, but women’s roles are often underrepresented in lieu of the images of tradesmen and farmers dropping the tools of the trade to fix bayonets and fight England. There is so much room for growth.What ways did women contribute to the rebellion and war effort? How are women’s contributions rewarded or ignored after the war’s conclusion? How did women’s roles inspire future generations in their pursuit of greater rights and recognition from the government they helped form?

Draw your own conclusions

|

Learn how to teach with inquiry.

Many of these lesson plans were sponsored in part by the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources Eastern Region Program, coordinated by Waynesburg University, the History and Social Studies Education Faculty at Plymouth State University, and the Patrons of the Remedial Herstory Project. |

Lesson Plans from Other Organizations

- The National Women's History Museum has lesson plans on women's history.

- The Gilder Lehrman Institute for American History has lesson plans on women's history.

- The NY Historical Society has articles and classroom activities for teaching women's history.

- Unladylike 2020, in partnership with PBS, has primary sources to explore with students and outstanding videos on women from the Progressive era.

- The Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media has produced recommendations for teaching women's history with primary sources and provided a collection of sources for world history. Check them out!

- The Stanford History Education Group has a number of lesson plans about women in US History.

Period Specific Lesson Plans from Other Organizations

- Gilder Lehrman: The concept of "Liberty" is one that many hold dear. However, what liberty means to each individual may vary depending on his or her situation. During the American Revolutionary War period, many saw opportunity to speak out and test the waters of liberty. With the issuance of the Declaration of Independence and its promises of "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness," many became convinced that this "American Experiment" would change the world. In this lesson students will be asked to explore several perspectives of liberty during this period. Including Mary Wollstonecraft.

- Edcitement: Paul Revere's ride is the most famous event of its kind in American history. But other Americans made similar rides during the American Revolution. Who were these men and women? Why were their rides important? Do they deserve to be better known?

- Gilder Lehrman: The American Revolution, a byproduct of events both on the North American continent and abroad, unleashed a movement that focused on egalitarianism in ways that had never been seen before. Even John Adams commented on these changes in a letter to his wife Abigail. He wrote, "We have been told that that our Struggle has loosened the bands of Government everywhere. That Children and Apprentices were disobedient—that schools and Colledges were grown turbulent—that Indians slighted their Guardians and Negroes grew insolent to the Masters. But your Letter was the first Intimation that another Tribe more numerous and powerfull than all the rest were grown discontented." His wife had prompted him to address a new tribe–women who were eager to challenge long-held assumptions about their role in the eighteenth-century world. Although most American students are familiar with the words of Abigail Adams, they are less familiar with the work and contributions of Catharine Macaulay, Phillis Wheatley, Hannah Adams, and Mercy Otis Warren, each of whom took up the "female pen" to record history and to share their views on politics and society. This lesson provides students with the opportunity to explore the varied talents and thoughts of these early advocates of women’s rights and their views on liberty.

- Gilder Lehrman: Labeling an era in history as revolutionary implies that research of the period in question exposed substantial change. Indeed significant change did occur during the American Revolutionary era—a colonial power lost a vital piece of its empire, a unified nation emerged, and a new republic was created. These are the major transformations of the Revolution but certainly not the only shifts that took place before the war or after and as a result of the war. It is the more subtle adjustments, the ones that sometimes are overlooked, that provide an interesting and challenging opportunity to practitioners and students of history. Historians of white women in early America have not agreed on a single conceptualization of women’s history. Often the analyses propose a comparison or an evaluation of women’s status. These historians conclude that the first two centuries for white women in North America were a kind of golden age. They hold that the status of women who immigrated to North America was better than that of the women they left behind in England and that of women in America in the nineteenth century. This kind of analysis may be valid but it is also rather narrow in scope and overshadows some aspects of women’s experiences. In this lesson the class will not seek to reach an evaluative conclusion—better or worse—but will instead look more broadly at change over time and all the subtleties that contribute to the differences in women’s responses to the changes that took place in this period in American History.

- Edcitement: In the absence of official power, women had to find other ways to shape the world in which they lived. The First Ladies of the United States were among the women who were able to play "a significant role in shaping the political and social history of our country, impacting virtually every topic that has been debated" (Mary Regula, Founding Chair and President, National Board of Directors for The First Ladies' Library). Through the lessons in this unit, you will explore with your students the ways in which First Ladies were able to shape the world while dealing with the expectations placed on them as women and as partners of powerful men.

- National Women’s History Museum: How did Sally Hemings shape life at Monticello? As an enslaved person, Sally Hemings struggled to improve her family’s prospects as she labored under the institution of slavery. By dividing her life into four major stages, students will encounter the difficult choices forced upon enslaved women by an evil institution.

Olympe De Gouges: Excerpt From The Declarations Of The Rights Of Woman And Citizen

Mothers, daughters, sisters, female representatives of the nation ask to be constituted [established] as a national assembly. Considering that ignorance, neglect, or contempt for the rights of woman are the sole causes of public misfortunes and governmental corruption, they have resolved to set forth in a solemn declaration [a serious statement that] the natural, inalienable [absolute], and sacred rights of woman: so that by being constantly present to all the members of the social body this declaration [announcement] may always remind them of their rights and duties; so that by being liable [responsible] at every moment to comparison with the aim of any and all political institutions the acts of women’s and men’s powers may be the more fully respected; and so that by being founded henceforward [going forward] on simple and incontestable [undeniable] principles the demands of the citizenesses may always tend toward maintaining the constitution, good morals, and the general welfare. In consequence, the sex that is superior in beauty as in courage, needed in maternal sufferings, recognizes and declares, in the presence and under the auspices [with the support] of the Supreme Being, the following rights of woman and the citizeness.

1. Woman is born free and remains equal to man in rights. Social distinctions may be based only on common utility.

2. The purpose of all political association is the preservation of the natural and imprescriptible [unable to be taken away] rights of woman and man. These rights are liberty, property, security, and especially resistance to oppression.

3. The principle of all sovereignty [power] rests essentially in the nation, which is but the reuniting of woman and man. No body and no individual may exercise authority which does not emanate [come] expressly from the nation.

4. Liberty and justice consist in restoring all that belongs to another; hence the exercise of the natural rights of woman has no other limits than those that the perpetual tyranny [complete authority] of man opposes to them; these limits must be reformed according to the laws of nature and reason.

5. The laws of nature and reason prohibit [forbid] all actions which are injurious [harmful] to society. No hindrance [barrier] should be put in the way of anything not prohibited by these wise and divine laws, nor may anyone be forced to do what they do not require.

6. The law should be the expression of the general will. All citizenesses and citizens should take part, in person or by their representatives, in its formation. It must be the same for everyone. All citizenesses and citizens, being equal in its eyes, should be equally admissible to all public dignities, offices and employments, according to their ability, and with no other distinction than that of their virtues and talents.

7. No woman is exempted; she is indicted, arrested, and detained in the cases determined by the law. Women like men obey this rigorous law. 8. Only strictly and obviously necessary punishments should be established by the law, and no one may be punished except by virtue of a law established and promulgated [made public] before the time of the offense, and legally applied to women.

9. Any woman being declared guilty, all rigor [strictness] is exercised by the law.

10. No one should be disturbed for his fundamental opinions; woman has the right to mount the scaffold, so she should have the right equally to mount the rostrum [platform], provided that these manifestations [actions] do not trouble public order as established by law.

11. The free communication of thoughts and opinions is one of the most precious of the rights of woman, since this liberty [freedom] assures the recognition of children by their fathers. Every citizeness may therefore say freely, I am the mother of your child; a barbarous prejudice [against unmarried women having children] should not force her to hide the truth, so long as responsibility is accepted for any abuse of this liberty in cases determined by the law [women are not allowed to lie about the paternity of their children].

12. The safeguard of the rights of woman and the citizeness requires public powers. These powers are instituted for the advantage of all and not for the private benefit of those to whom they are entrusted.

13. For maintenance of public authority and for expenses of administration, taxation of women and men is equal; she takes part in all forced labor service, in all painful tasks; she must therefore have the same proportion in the distribution of places, employments, offices, dignities, and in industry.

14. The citizenesses and citizens have the right, by themselves or through their representatives, to have demonstrated to them the necessity of public taxes. The citizenesses can only agree to them upon admission of an equal division, not only in wealth, but also in the public administration, and to determine the means of apportionment, assessment, and collection, and the duration of the taxes.

15. The mass of women, joining with men in paying taxes, have the right to hold accountable every public agent of the administration.

16. Any society in which the guarantee of rights is not assured or the separation of powers not settled has no constitution. The constitution is null and void if the majority of individuals composing the nation has not cooperated in its drafting.

17. Property belongs to both sexes whether united or separated; it is for each of them an inviolable and sacred right, and no one may be deprived of it as a true patrimony of nature, except when public necessity, certified by law, obviously requires it, and then on condition of a just compensation in advance.

Women, wake up; the tocsin [signal] of reason sounds throughout the universe; recognize your rights. The powerful empire of nature is no longer surrounded by prejudice [prejudgement], fanaticism [extremeness/madness]], superstition, and lies. The torch of truth has dispersed [scattered] all the clouds of folly and usurpation [wrongful possession of authority]. Enslaved man has multiplied his force and needs yours to break his chains. Having become free, he has become unjust toward his companion. Oh women! Women, when will you cease to be blind? What advantages have you gathered in the Revolution? A scorn more marked, a disdain more conspicuous [clear]. During the centuries of corruption you only reigned over the weakness of men. Your empire is destroyed; what is left to you then? Firm belief in the injustices of men. The reclaiming of your patrimony [father’s inheritance] founded on the wise decrees of nature; why should you fear such a beautiful enterprise? … Whatever the barriers set up against you, it is in your power to overcome them; you only have to want it. Let us pass now to the appalling [horrifying] account of what you have been in society; and since national education is an issue at this moment, let us see if our wise legislators will think sanely about the education of women….

Hunt, Lynn. The French Revolution and human rights: a brief documentary history. Boston: Bedford Books of St. Martin's Press, 1996.

Questions:

1. What are three rights she demands that stand out to you?

2. Is there any language in the text that would rally women?

3. Is there any language in the text that appears anti-men?

4. Why might someone deem this as unpatriotic?

1. Woman is born free and remains equal to man in rights. Social distinctions may be based only on common utility.

2. The purpose of all political association is the preservation of the natural and imprescriptible [unable to be taken away] rights of woman and man. These rights are liberty, property, security, and especially resistance to oppression.

3. The principle of all sovereignty [power] rests essentially in the nation, which is but the reuniting of woman and man. No body and no individual may exercise authority which does not emanate [come] expressly from the nation.

4. Liberty and justice consist in restoring all that belongs to another; hence the exercise of the natural rights of woman has no other limits than those that the perpetual tyranny [complete authority] of man opposes to them; these limits must be reformed according to the laws of nature and reason.

5. The laws of nature and reason prohibit [forbid] all actions which are injurious [harmful] to society. No hindrance [barrier] should be put in the way of anything not prohibited by these wise and divine laws, nor may anyone be forced to do what they do not require.

6. The law should be the expression of the general will. All citizenesses and citizens should take part, in person or by their representatives, in its formation. It must be the same for everyone. All citizenesses and citizens, being equal in its eyes, should be equally admissible to all public dignities, offices and employments, according to their ability, and with no other distinction than that of their virtues and talents.

7. No woman is exempted; she is indicted, arrested, and detained in the cases determined by the law. Women like men obey this rigorous law. 8. Only strictly and obviously necessary punishments should be established by the law, and no one may be punished except by virtue of a law established and promulgated [made public] before the time of the offense, and legally applied to women.

9. Any woman being declared guilty, all rigor [strictness] is exercised by the law.

10. No one should be disturbed for his fundamental opinions; woman has the right to mount the scaffold, so she should have the right equally to mount the rostrum [platform], provided that these manifestations [actions] do not trouble public order as established by law.

11. The free communication of thoughts and opinions is one of the most precious of the rights of woman, since this liberty [freedom] assures the recognition of children by their fathers. Every citizeness may therefore say freely, I am the mother of your child; a barbarous prejudice [against unmarried women having children] should not force her to hide the truth, so long as responsibility is accepted for any abuse of this liberty in cases determined by the law [women are not allowed to lie about the paternity of their children].

12. The safeguard of the rights of woman and the citizeness requires public powers. These powers are instituted for the advantage of all and not for the private benefit of those to whom they are entrusted.

13. For maintenance of public authority and for expenses of administration, taxation of women and men is equal; she takes part in all forced labor service, in all painful tasks; she must therefore have the same proportion in the distribution of places, employments, offices, dignities, and in industry.

14. The citizenesses and citizens have the right, by themselves or through their representatives, to have demonstrated to them the necessity of public taxes. The citizenesses can only agree to them upon admission of an equal division, not only in wealth, but also in the public administration, and to determine the means of apportionment, assessment, and collection, and the duration of the taxes.

15. The mass of women, joining with men in paying taxes, have the right to hold accountable every public agent of the administration.

16. Any society in which the guarantee of rights is not assured or the separation of powers not settled has no constitution. The constitution is null and void if the majority of individuals composing the nation has not cooperated in its drafting.

17. Property belongs to both sexes whether united or separated; it is for each of them an inviolable and sacred right, and no one may be deprived of it as a true patrimony of nature, except when public necessity, certified by law, obviously requires it, and then on condition of a just compensation in advance.

Women, wake up; the tocsin [signal] of reason sounds throughout the universe; recognize your rights. The powerful empire of nature is no longer surrounded by prejudice [prejudgement], fanaticism [extremeness/madness]], superstition, and lies. The torch of truth has dispersed [scattered] all the clouds of folly and usurpation [wrongful possession of authority]. Enslaved man has multiplied his force and needs yours to break his chains. Having become free, he has become unjust toward his companion. Oh women! Women, when will you cease to be blind? What advantages have you gathered in the Revolution? A scorn more marked, a disdain more conspicuous [clear]. During the centuries of corruption you only reigned over the weakness of men. Your empire is destroyed; what is left to you then? Firm belief in the injustices of men. The reclaiming of your patrimony [father’s inheritance] founded on the wise decrees of nature; why should you fear such a beautiful enterprise? … Whatever the barriers set up against you, it is in your power to overcome them; you only have to want it. Let us pass now to the appalling [horrifying] account of what you have been in society; and since national education is an issue at this moment, let us see if our wise legislators will think sanely about the education of women….

Hunt, Lynn. The French Revolution and human rights: a brief documentary history. Boston: Bedford Books of St. Martin's Press, 1996.

Questions:

1. What are three rights she demands that stand out to you?

2. Is there any language in the text that would rally women?

3. Is there any language in the text that appears anti-men?

4. Why might someone deem this as unpatriotic?

Olympe De Gouges: Transcript Of Her Trial

The clerk read the act of accusation...

“Antoine-Quentin Fouquier-Tinville, public prosecutor before the Revolutionary

Tribunal, etc.

States that, by an order of the administrators of police, dated last July 25th,

signed Louvet and Baudrais, it was ordered that Marie Olympe de Gouges, widow of

Aubry, charged with having composed [written] a work contrary [differing] to the

expressed desire of the entire nation, and directed against whoever might propose a

form of government other than that of a republic, one and indivisible, be brought to the

prison…

From the examination of the documents deposited [put], together with the

interrogation of the accused, it follows that… Olympe de Gouges composed [written]

and had printed works which can only be considered as an attack on the sovereignty

[supreme power] of the people…

. . . The public prosecutor stated next that it is with the most violent indignation

[offense] that one hears the de Gouges woman say to men who for the past four years

have not stopped making the greatest sacrifices for liberty [freedom]…

There can be no mistaking the perfidious [untrustworthy] intentions of this

criminal woman, and her hidden motives, when one observes her in all the works to

which, at the very least, she lends her name, calumniating [falsifying/defaming] and

spewing out bile [nastiness] in large doses…

When the accused was questioned sharply about when she composed this

writing, she replied that it was some time last May, adding that what motivated her was

that seeing the storms arising in a large number of départements, and notably in

Bordeaux, Lyons, Marseilles, etc., she had the idea of bringing all parties together by

leaving them all free in the choice of the kind of government which would be most

suitable for them; that furthermore, her intentions had proven that she had in view only

the happiness of her country.

Questioned about how it was that she, the accused, who believed herself to be

such a good patriot, had been able to develop, in the month of June, means which she

called conciliatory [peacebuilding] concerning a fact which could no longer be in

question because the people, at that period, had formally pronounced for republican

government, one and indivisible, she replied that this was also the [form of government]

she had voted for as the preferable one; that for a long while she had professed

[declared] only republican sentiments {point of view], as the jurors would be able to

convince themselves from her work entitled De l'ésclavage des noirs.

Asked to speak concerning various phrases in the placard [public notice]… she

responded… in saying that she was and always had been a good citoyenne [citizen]…

During the resume of the charge brought by the public prosecutor, the accused,

with respect to the facts she was hearing articulated against her, never stopped her

smirking. Sometimes she shrugged her shoulders; then she clasped her hands and raised

her eyes towards the ceiling of the room; then, suddenly, she moved on to an expressive

gesture, showing astonishment; then gazing next at the court, she smiled at the

spectators, etc.

Here is the judgment rendered against her.

The Tribunal, based on the unanimous declaration of the jury, stating that:

(1) it is a fact that there exist in the case writings tending towards the

reestablishment of a power attacking the sovereignty of the people; [and]

(2) that Marie Olympe de Gouges… is proven guilty… condemn[ed] to

the punishment of death… and declares the goods of the aforementioned

Marie Olympe de Gouges seized for the benefit of the republic. . . .

[G]iven the public declaration made by the aforementioned Marie Olympe de

Gouges that she was pregnant, the Tribunal, following the indictment of the public

prosecutor, orders that the aforementioned Marie Olympe de Gouges will be seen and