3. 10,000 BCE The Agricultural Revolution: A great mistake?

The Agricultural Revolution allowed humanity to evolve from hunter gather societies to societies capable of building advanced and enormous civilizations, but did we lose more than we gained? Maybe. Women became slaves to the grind stone, health declined, and hierarchies established gender norms that lasted millennia. Birth rates improved, surpluses of food, and everything considered modern evolved from the agricultural revolution. Weighing it all-- it's hard to say whether this was revolutionary for women.

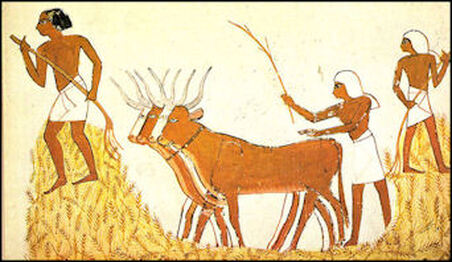

Wikimedia Commons

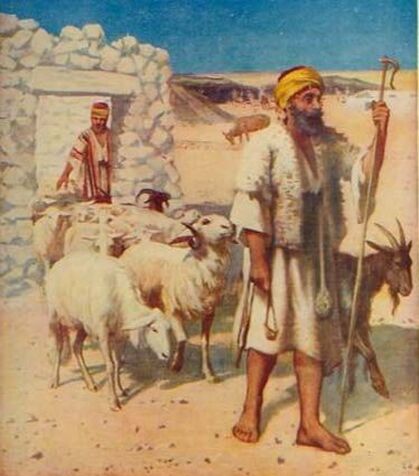

Wikimedia Commons

It is hard to say whether the agricultural revolution was revolutionary for women. What we do know is that gender hierarchies were established that lasted for millennia, while birth rates increased along with the agricultural revolution. Between 10,500 and 8,500 BCE, humans began to switch from hunting and gathering to farming, a change that led to larger populations in permanent settlements in many parts of the world. This development is known as the first Agricultural Revolution or the Neolithic Revolution. Over many generations, the shift to agriculture led to the creation of cities, the emergence of organized religions and political structures, and trade between people in different localities. But as we learn more and more about how humans lived before the Agricultural Revolution it seems like we might have lost more than we gained.

The Agricultural Revolution took place at different times in different parts of the world, but the first one began in what we call the Fertile Crescent, the land between the Tigris and Euphrates River Valleys in Mesopotamia to the Nile River valley in Egypt. It is here that archeologists have found the earliest evidence of the beginning of agriculture. That is where we will take our closest look at the evidence, focusing on bones and artifacts from two cultures in the Fertile Crescent, the Neolithic farming settlement at Abu Hureyra and the settled hunter-gatherers of the Natufian culture prior to the Neolithic Revolution. We will also consider evidence anthropologists have gathered from foraging societies that exist today.

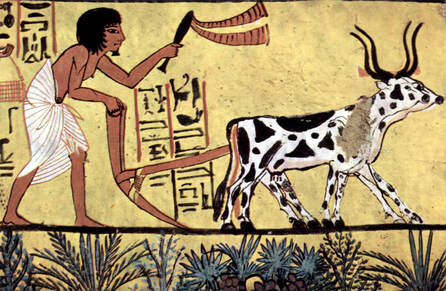

Prehistoric women were at the heart of the transition to farming from hunting and gathering. Hunting was generally the task assigned to the most able-bodied people of the community, usually men in their prime. Women, children, and the elderly worked together to gather grains, fruit, and legumes from the wild. It is possible that women were the ones who observed the connection between fallen seeds and a richer harvest when they returned to a certain spot later. The earliest version of farming predated the Bronze Age, so it did not involve a plow. The farmer would use a stick to poke a hole in which the seed was dropped. After harvest, women would do much, if not all, of the food preparation, a task that called for grinding the grain on a stone pallet. There is evidence that women in the earliest farming communities were physically very strong. An analysis of prehistoric women’s arm bone fragments reveals that ancient women had bone strength that measured 9% stronger than modern athletic women.

That strength came with a cost. When Theya Molleson of the British Museum looked at the remains of women from Abu Hureyra, a site occupied for 6000 years in what is now Syria, she found evidence that women spent hours kneeling over their grinding stones, resulting in deformed toes, curved thigh bones, and arthritic knees and backs. Pre-agriculture skeletons revealed none of those issues. Furthermore, the teeth of Neolithic farming people first showed more wear and tear as tiny bits of stone ended up in the grain, and later showed more cavities and gum disease as the soft porridge they ate left a build-up of sugar and carbohydrates on the tooth enamel. Farming peoples worked harder and were far less healthy overall.

The Agricultural Revolution took place at different times in different parts of the world, but the first one began in what we call the Fertile Crescent, the land between the Tigris and Euphrates River Valleys in Mesopotamia to the Nile River valley in Egypt. It is here that archeologists have found the earliest evidence of the beginning of agriculture. That is where we will take our closest look at the evidence, focusing on bones and artifacts from two cultures in the Fertile Crescent, the Neolithic farming settlement at Abu Hureyra and the settled hunter-gatherers of the Natufian culture prior to the Neolithic Revolution. We will also consider evidence anthropologists have gathered from foraging societies that exist today.

Prehistoric women were at the heart of the transition to farming from hunting and gathering. Hunting was generally the task assigned to the most able-bodied people of the community, usually men in their prime. Women, children, and the elderly worked together to gather grains, fruit, and legumes from the wild. It is possible that women were the ones who observed the connection between fallen seeds and a richer harvest when they returned to a certain spot later. The earliest version of farming predated the Bronze Age, so it did not involve a plow. The farmer would use a stick to poke a hole in which the seed was dropped. After harvest, women would do much, if not all, of the food preparation, a task that called for grinding the grain on a stone pallet. There is evidence that women in the earliest farming communities were physically very strong. An analysis of prehistoric women’s arm bone fragments reveals that ancient women had bone strength that measured 9% stronger than modern athletic women.

That strength came with a cost. When Theya Molleson of the British Museum looked at the remains of women from Abu Hureyra, a site occupied for 6000 years in what is now Syria, she found evidence that women spent hours kneeling over their grinding stones, resulting in deformed toes, curved thigh bones, and arthritic knees and backs. Pre-agriculture skeletons revealed none of those issues. Furthermore, the teeth of Neolithic farming people first showed more wear and tear as tiny bits of stone ended up in the grain, and later showed more cavities and gum disease as the soft porridge they ate left a build-up of sugar and carbohydrates on the tooth enamel. Farming peoples worked harder and were far less healthy overall.

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

Farming peoples had a less nutritious diet based on only a few crops compared to a diet based on a variety of gathered foods. Ancient farmers likely developed heart conditions and digestive difficulties, among other conditions.

Humans lost their connection to nature along the way. Modern-day foragers, who live much like our hunter gatherer ancestors did, still experience this deep sense of connection with the natural world. When a forager arrives at a new place, she will spend time observing and absorbing the sights and smells around her. Many wild animals do the same thing.

How do we know that the diet of the earliest farmers was deficient when compared to that of hunter gatherers? We can’t be certain if this was true of all prehistoric peoples, but evidence from Natufian sites tell us that their diets were rich, and people did not have to work hard to get enough to eat. Although we used to assume that life before farming was brutal, archeologists have unearthed evidence that dramatically alters what we thought we knew about life before the Neolithic Revolution. One site, Ohalo II, was inhabited continuously for many generations almost 23,000 years ago. These humans were hunter gatherers, but they were not migratory. They live in small villages near forests and waterways and let the food come to them. They survived on a rich array of resources without having to travel to find them.

Archeologists have found the remains of food such as almonds, pistachios, olives, grapes, and many other edible plants. Among these is a fruit known as the Rubus, which is similar to a blackberry. That’s something that had to be eaten fresh. Animal remains included a wide variety of fish, turtles, waterfowl, and several breeds of mammal ranging from rabbit to gazelles. Archaeologists found grinding stones that still held fragments of barley, wheat, and oats. There were even sickle blades, showing us the residents of this tiny village had figured out how to harvest, although the evidence suggests they engaged only in small-scale planting. Archeologists have found very little wear and tear on the sickle blades, supporting the idea that they were only used occasionally. Residents in this settlement were likely well fed but probably not overworked. Men’s and women’s skeletons were very similar in terms of wear and tear and overall health. It was only after humans took up farming that women’s bodies bore the mark of physical labor from activities such as bending over a grindstone. Farming people were also shorter than earlier humans, due to their limited diet.

Humans lost their connection to nature along the way. Modern-day foragers, who live much like our hunter gatherer ancestors did, still experience this deep sense of connection with the natural world. When a forager arrives at a new place, she will spend time observing and absorbing the sights and smells around her. Many wild animals do the same thing.

How do we know that the diet of the earliest farmers was deficient when compared to that of hunter gatherers? We can’t be certain if this was true of all prehistoric peoples, but evidence from Natufian sites tell us that their diets were rich, and people did not have to work hard to get enough to eat. Although we used to assume that life before farming was brutal, archeologists have unearthed evidence that dramatically alters what we thought we knew about life before the Neolithic Revolution. One site, Ohalo II, was inhabited continuously for many generations almost 23,000 years ago. These humans were hunter gatherers, but they were not migratory. They live in small villages near forests and waterways and let the food come to them. They survived on a rich array of resources without having to travel to find them.

Archeologists have found the remains of food such as almonds, pistachios, olives, grapes, and many other edible plants. Among these is a fruit known as the Rubus, which is similar to a blackberry. That’s something that had to be eaten fresh. Animal remains included a wide variety of fish, turtles, waterfowl, and several breeds of mammal ranging from rabbit to gazelles. Archaeologists found grinding stones that still held fragments of barley, wheat, and oats. There were even sickle blades, showing us the residents of this tiny village had figured out how to harvest, although the evidence suggests they engaged only in small-scale planting. Archeologists have found very little wear and tear on the sickle blades, supporting the idea that they were only used occasionally. Residents in this settlement were likely well fed but probably not overworked. Men’s and women’s skeletons were very similar in terms of wear and tear and overall health. It was only after humans took up farming that women’s bodies bore the mark of physical labor from activities such as bending over a grindstone. Farming people were also shorter than earlier humans, due to their limited diet.

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

Historian, Jared Diamond, argues, “Farming may have encouraged inequality between the sexes, as well. Freed from the need to transport their babies during a nomadic existence,and under pressure to produce more hands to till the fields, farming women tended to have more frequent pregnancies than their hunter-gatherer counterparts- with consequent drains on their health. Among the Chilean mummies, for example, more women than men had bone lesions from infectious disease.”

The Agricultural Revolution represents a move away from tiny settlements like those at Ohalo II and toward massive populations laboring to farm larger and larger territories. The process shows its first dramatic changes in the Fertile Crescent between 9,500 and 8,500 BCE. Humans sought to increase production of wheat, originally a wild grass, but one which grew easily if properly protected. Doing so meant not just plowing the soil and sowing the seeds. It meant draining the land if the weather was too wet and building irrigation ditches if it was too dry. Wheat had to be protected with fences from pests like rabbits. Just as we saw with the activities surrounding the preparation of grains— regular kneeling to grind grain for hours—the labor that went into the planting and protection of the fields left its traces on human bones. Spines, knees, necks, and feet showed increasing damage with every generation of farmers.

Furthermore, settling so many people in one place led to a build-up of human and animal waste, spreading diseases such as parasites, infections, and viruses. Pests too small to block out with fences, such as rats and mice, were attracted to stored food. The growth of rodent populations attracted predators such as wild cats and dogs, leading to the domestication of those animals.

Fields also had to be protected from human rivals. Although scholars have claimed since the Renaissance that prehistoric humans were violent brutes, their lives were calm compared to the violence that accompanied competition for scarce resources. When a hunter-gatherer group felt the pressure of a stronger bunch of foragers, it could simply move elsewhere. That was no longer an option. The cultivated land had to be protected from scavengers and neighbors or the community would starve. Even the simplest farmer had to be prepared to defend the land.

The Agricultural Revolution represents a move away from tiny settlements like those at Ohalo II and toward massive populations laboring to farm larger and larger territories. The process shows its first dramatic changes in the Fertile Crescent between 9,500 and 8,500 BCE. Humans sought to increase production of wheat, originally a wild grass, but one which grew easily if properly protected. Doing so meant not just plowing the soil and sowing the seeds. It meant draining the land if the weather was too wet and building irrigation ditches if it was too dry. Wheat had to be protected with fences from pests like rabbits. Just as we saw with the activities surrounding the preparation of grains— regular kneeling to grind grain for hours—the labor that went into the planting and protection of the fields left its traces on human bones. Spines, knees, necks, and feet showed increasing damage with every generation of farmers.

Furthermore, settling so many people in one place led to a build-up of human and animal waste, spreading diseases such as parasites, infections, and viruses. Pests too small to block out with fences, such as rats and mice, were attracted to stored food. The growth of rodent populations attracted predators such as wild cats and dogs, leading to the domestication of those animals.

Fields also had to be protected from human rivals. Although scholars have claimed since the Renaissance that prehistoric humans were violent brutes, their lives were calm compared to the violence that accompanied competition for scarce resources. When a hunter-gatherer group felt the pressure of a stronger bunch of foragers, it could simply move elsewhere. That was no longer an option. The cultivated land had to be protected from scavengers and neighbors or the community would starve. Even the simplest farmer had to be prepared to defend the land.

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

This competition and need to protect the harvest contributed to a growing hierarchy in society. Just as farming might have been advanced by a clever individual who could direct projects and rise in status in the group, the need for protection introduced dedicated warriors to guard the boundaries. The next logical step, of course, was that dedicated warriors and community leaders were increasingly excused from the actual labor and were fed by the work of others. Hierarchies emerged, leaders became entrenched, and over thousands of years, division of labor extended to specialized occupations that served those in power at the expense of those who worked the hardest.

Burial practices reflected the change in social order. In pre-farming burial sites, the graves of men and women are all roughly the same. People were buried with a few items that seemed to link each person to a particular clan or place. The dead were often buried very near to the homes of descendants, linking the living to the ancestors. After the agricultural revolution, graves began to show enormous differences in wealth and status. Poor laborers were buried with almost nothing, while warrior graves contained weapons, and the graves of the wealthy and powerful people contained treasures and food offerings. Just as agriculture created wealth for some, it also created poverty for others.

All territories were now under someone’s control. Even if someone chose to leave life in the settled city, there was not much “free territory” available. If you did find an unclaimed piece of land, it usually required even more hard labor because you and your family had to clear the land in order to survive.

What made humans settle down and take up farming, if it made life harder and damaged our overall health? One possibility is that humans simply had no choice. At the end of the last great Ice Age, the climate was changing dramatically. Parts of Mesopotamia that we tend to think of purely as desert were actually once very wet.

Landscape archeologist Jennifer Pournelle mapped out the elaborate waterways and wetlands that used to cover all of Southern Mesopotamia. The land was lush, and food was plentiful. However, as the land began to dry up, the great diversity of plants and animals disappeared. Humans were left with the task of encouraging a few edible plants to grow on as much land as possible. The early phases of farming might not have required backbreaking labor, since it was still possible to throw seeds on fertile land that was exposed as waters receded. As the climate became even drier, though, humans had to adapt their work again to make crops grow.

During and after the Agricultural Revolution, when enormous cities emerged in Mesopotamia, some semi-migratory groups continued to thrive. They were not foragers, however. They tended to be pastoralists who largely lived off herding goats, sheep, and cattle. These groups continued to enjoy relatively egalitarian social relations. However, life was difficult in early agricultural societies.

Burial practices reflected the change in social order. In pre-farming burial sites, the graves of men and women are all roughly the same. People were buried with a few items that seemed to link each person to a particular clan or place. The dead were often buried very near to the homes of descendants, linking the living to the ancestors. After the agricultural revolution, graves began to show enormous differences in wealth and status. Poor laborers were buried with almost nothing, while warrior graves contained weapons, and the graves of the wealthy and powerful people contained treasures and food offerings. Just as agriculture created wealth for some, it also created poverty for others.

All territories were now under someone’s control. Even if someone chose to leave life in the settled city, there was not much “free territory” available. If you did find an unclaimed piece of land, it usually required even more hard labor because you and your family had to clear the land in order to survive.

What made humans settle down and take up farming, if it made life harder and damaged our overall health? One possibility is that humans simply had no choice. At the end of the last great Ice Age, the climate was changing dramatically. Parts of Mesopotamia that we tend to think of purely as desert were actually once very wet.

Landscape archeologist Jennifer Pournelle mapped out the elaborate waterways and wetlands that used to cover all of Southern Mesopotamia. The land was lush, and food was plentiful. However, as the land began to dry up, the great diversity of plants and animals disappeared. Humans were left with the task of encouraging a few edible plants to grow on as much land as possible. The early phases of farming might not have required backbreaking labor, since it was still possible to throw seeds on fertile land that was exposed as waters receded. As the climate became even drier, though, humans had to adapt their work again to make crops grow.

During and after the Agricultural Revolution, when enormous cities emerged in Mesopotamia, some semi-migratory groups continued to thrive. They were not foragers, however. They tended to be pastoralists who largely lived off herding goats, sheep, and cattle. These groups continued to enjoy relatively egalitarian social relations. However, life was difficult in early agricultural societies.

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

A hunter will take any animal he finds, but the farmer will carefully select more easily controlled animals. He will eat male animals and female livestock too old to breed, but spare young female animals to ensure a bigger herd through their young. The movement of animals had to be limited to keep them from wandering off, and pastoralists had to stay on the move to find enough food for the herd while fending off predators. Sheep, goats, pigs, and cattle as we know them today are almost completely dependent on human care. They would not survive in the wild.

Apart from climate change, another possible explanation for the move towards agriculture has to do with religion. In Turkey, there is an ancient religious complex at Göbekli Tepe, dating back to 9500 BCE. There were no dwellings or fortifications there, and evidence points to this religious site predating widespread farming. There are traces of feasts, in the form of ancient bread and beer, all made from grains collected in the wild. There are large carved sculptures of humans and wild animals. There are a few a huge stone monoliths as well. For most of history, we have assumed that large buildings emerged only after the rise of agriculture. But something moved these foragers to cooperate in the creation of something majestic in honor of the gods.

Some mysterious spiritual calling led hunter-gatherers to gather at Göbekli Tepe to build, worship, and then return to their nomadic or semi-settled lives. Ideas about the cosmos and worship of deities may have indicated a growing sense that humans were not like other animals. Some scholars believe that our growing disconnection from nature led to farming rather than farming leading us away from nature.

Why did humans not reverse course when they realized that life had become so much harder? The simplest explanation is that when you see how everything has changed, it’s usually too late to reverse course. Change is gradual, and even if we are aware that society is changing, it is very difficult to figure out how to improve your situation. For example, a serious downside to hunter-gatherer life created the absolute need to limit the size of the population even if that meant committing infanticide to keep numbers low. After the Agricultural Revolution, when surplus food was available, families could feed more people, making it possible to have bigger families. It is difficult after generations of population growth to simply go back to being hunter-gatherers.

There is still some debate regarding the impact of humans having bigger families. Historian Yuval Noah Harari reminds us that humans no longer practiced infanticide after the advent of settled farming, but infant mortalityincreased all the same. Many farming mothers fed their babies porridge in order to stop nursing and return to heavy labor. The lack of mother’s milk contributed to illness and weaknesses among children.

By the end of this era, so much remained in question. Did the benefits of settled life outweigh the loss of free time and a more equal society where men and women shared responsibilities and roles were less gendered? Could ancient humans have made any other choice? It is possible that the life of a forager is better in terms of balance, connection to nature, a varied diet, and mutual respect for all members of the community. But, for all its cost, agriculture has led over time to amazing advances in the arts, science, language, and literature. Once humans began to engage in settled agriculture, everything we enjoy in modern life became possible.

Was it worth it, or was the Agricultural Revolution a huge mistake?

Apart from climate change, another possible explanation for the move towards agriculture has to do with religion. In Turkey, there is an ancient religious complex at Göbekli Tepe, dating back to 9500 BCE. There were no dwellings or fortifications there, and evidence points to this religious site predating widespread farming. There are traces of feasts, in the form of ancient bread and beer, all made from grains collected in the wild. There are large carved sculptures of humans and wild animals. There are a few a huge stone monoliths as well. For most of history, we have assumed that large buildings emerged only after the rise of agriculture. But something moved these foragers to cooperate in the creation of something majestic in honor of the gods.

Some mysterious spiritual calling led hunter-gatherers to gather at Göbekli Tepe to build, worship, and then return to their nomadic or semi-settled lives. Ideas about the cosmos and worship of deities may have indicated a growing sense that humans were not like other animals. Some scholars believe that our growing disconnection from nature led to farming rather than farming leading us away from nature.

Why did humans not reverse course when they realized that life had become so much harder? The simplest explanation is that when you see how everything has changed, it’s usually too late to reverse course. Change is gradual, and even if we are aware that society is changing, it is very difficult to figure out how to improve your situation. For example, a serious downside to hunter-gatherer life created the absolute need to limit the size of the population even if that meant committing infanticide to keep numbers low. After the Agricultural Revolution, when surplus food was available, families could feed more people, making it possible to have bigger families. It is difficult after generations of population growth to simply go back to being hunter-gatherers.

There is still some debate regarding the impact of humans having bigger families. Historian Yuval Noah Harari reminds us that humans no longer practiced infanticide after the advent of settled farming, but infant mortalityincreased all the same. Many farming mothers fed their babies porridge in order to stop nursing and return to heavy labor. The lack of mother’s milk contributed to illness and weaknesses among children.

By the end of this era, so much remained in question. Did the benefits of settled life outweigh the loss of free time and a more equal society where men and women shared responsibilities and roles were less gendered? Could ancient humans have made any other choice? It is possible that the life of a forager is better in terms of balance, connection to nature, a varied diet, and mutual respect for all members of the community. But, for all its cost, agriculture has led over time to amazing advances in the arts, science, language, and literature. Once humans began to engage in settled agriculture, everything we enjoy in modern life became possible.

Was it worth it, or was the Agricultural Revolution a huge mistake?

Draw your own conclusions

|

Learn how to teach with inquiry.

Many of these lesson plans were sponsored in part by the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources Eastern Region Program, coordinated by Waynesburg University, the History and Social Studies Education Faculty at Plymouth State University, and the Patrons of the Remedial Herstory Project. |

Lesson Plans from Other Organizations

- This website, Women in World History has primary source based lesson plans on women's history in a whole range of topics. Some are free while others have a cost.

- The Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media has produced recommendations for teaching women's history with primary sources and provided a collection of sources for world history. Check them out!

- The Stanford History Education Group has a number of lesson plans about women in World History.

Kojiki: Record of Ancient Things

This story is from the Kojiki, the Japanese "Record of Ancient Things". This story was among many that were recorded between 500-700CE to preserve the ancient traditions. The following story is the closest to a creation story there is in this text.

When heaven and earth began, three deities came into being, The Spirit Master of the Center of Heaven, The August Wondrously Producing Spirit, and the Divine Wondrously Producing Ancestor. These three were invisible. The earth was young then, and land floated like oil, and from it reed shoots sprouted. From these reeds came two more deities. After them, five or six pairs of deities came into being, and the last of these were Izanagi and Izanami, whose names mean "The Male Who Invites" and "The Female who Invites".

The first five deities commanded Izanagi and Izanami to make and solidify the land of Japan, and they gave the young pair a jeweled spear. Standing on the Floating Bridge of Heaven, they dipped it in the ocean brine and stirred. They pulled out the spear, and the brine that dripped of it formed an island to which they descended. On this island they built a palace for their wedding and a great column to the heavens.

Izanami examined her body and found that one place had not grown, and she told this to Izanagi, who replied that his body was well-formed but that one place had grown to excess. He proposed that he place his excess in her place that was not complete and that in doing so they would make new land. They agreed to walk around the pillar and meet behind it to do this. When they arrive behind the pillar, she greeted him by saying "What a fine young man", and he responded by greeting her with "What a fine young woman". They procreated and gave birth to a leech-child, which they put in a basket and let float away. Then they gave birth to a floating island, which likewise they did not recognize as one of their children.

Disappointed by their failures in procreation, they returned to Heaven and consulted the deities there. The deities explained that the cause of their difficulties was that the female had spoken first when they met to procreate. Izanagi and Izanami returned to their island and again met behind the heavenly pillar. When they met, he said, "What a fine young woman," and she said "What a fine young man". They mated and gave birth to the eight main islands of Japan and six minor islands. Then they gave birth to a variety of deities to inhabit those islands, including the sea deity, the deity of the sea-straits, and the deities of the rivers, winds, trees, and mountains. Last, Izanami gave birth to the fire deity, and her genitals were so burned that she died.

Donald L. Philippi, trans., 1969, Kojiki: Princeton, Princeton University Press, 655, and Joseph M. Campbell, 1962, The Masks of God: Oriental Mythology: New York, Viking Press, 561.

Questions:

When heaven and earth began, three deities came into being, The Spirit Master of the Center of Heaven, The August Wondrously Producing Spirit, and the Divine Wondrously Producing Ancestor. These three were invisible. The earth was young then, and land floated like oil, and from it reed shoots sprouted. From these reeds came two more deities. After them, five or six pairs of deities came into being, and the last of these were Izanagi and Izanami, whose names mean "The Male Who Invites" and "The Female who Invites".

The first five deities commanded Izanagi and Izanami to make and solidify the land of Japan, and they gave the young pair a jeweled spear. Standing on the Floating Bridge of Heaven, they dipped it in the ocean brine and stirred. They pulled out the spear, and the brine that dripped of it formed an island to which they descended. On this island they built a palace for their wedding and a great column to the heavens.

Izanami examined her body and found that one place had not grown, and she told this to Izanagi, who replied that his body was well-formed but that one place had grown to excess. He proposed that he place his excess in her place that was not complete and that in doing so they would make new land. They agreed to walk around the pillar and meet behind it to do this. When they arrive behind the pillar, she greeted him by saying "What a fine young man", and he responded by greeting her with "What a fine young woman". They procreated and gave birth to a leech-child, which they put in a basket and let float away. Then they gave birth to a floating island, which likewise they did not recognize as one of their children.

Disappointed by their failures in procreation, they returned to Heaven and consulted the deities there. The deities explained that the cause of their difficulties was that the female had spoken first when they met to procreate. Izanagi and Izanami returned to their island and again met behind the heavenly pillar. When they met, he said, "What a fine young woman," and she said "What a fine young man". They mated and gave birth to the eight main islands of Japan and six minor islands. Then they gave birth to a variety of deities to inhabit those islands, including the sea deity, the deity of the sea-straits, and the deities of the rivers, winds, trees, and mountains. Last, Izanami gave birth to the fire deity, and her genitals were so burned that she died.

Donald L. Philippi, trans., 1969, Kojiki: Princeton, Princeton University Press, 655, and Joseph M. Campbell, 1962, The Masks of God: Oriental Mythology: New York, Viking Press, 561.

Questions:

- Is there one god, goddess, or many? Name the characters.

- Who is responsible for creating humans?

- Is anyone asked to be silent in this story? Who?

- What happens to the female characters?

Livius: The Weidner Chronicle

The Weidner Chronicle is a religious ancient Babylonian text that acted as propaganda to illustrate the Mesopotamian rulers who insulted the god Marduk. In the text, Kubaba convinces a fisherman to offer his catch to Esagila (a temple dedicated to Marduk). In return, Marduk gives Kubaba her kingship.

In the reign of Puzur-Nirah, king of Akšak, the freshwater fishermen of Esagila were catching fish for the meal of the great lord Marduk; the officers of the king took away the fish.The fisherman was fishing when 7 (or 8) days had passed [...] in the house of Kubaba, the tavern-keeper [...] they brought to Esagila…Kubaba gave bread to the fisherman and gave water, she made him offer the fish to Esagila. Marduk, [a god] the king, the prince of the Apsû, favored her and said: "Let it be so!" He entrusted to Kubaba, the tavern-keeper, sovereignty over the whole world.

Weidner Chronicle, Livius. https://www.livius.org/sources/content/mesopotamian-chronicles-content/abc-19-weidner-chronicle/.

In the reign of Puzur-Nirah, king of Akšak, the freshwater fishermen of Esagila were catching fish for the meal of the great lord Marduk; the officers of the king took away the fish.The fisherman was fishing when 7 (or 8) days had passed [...] in the house of Kubaba, the tavern-keeper [...] they brought to Esagila…Kubaba gave bread to the fisherman and gave water, she made him offer the fish to Esagila. Marduk, [a god] the king, the prince of the Apsû, favored her and said: "Let it be so!" He entrusted to Kubaba, the tavern-keeper, sovereignty over the whole world.

Weidner Chronicle, Livius. https://www.livius.org/sources/content/mesopotamian-chronicles-content/abc-19-weidner-chronicle/.

Sîn-Lēqi-Unninni: The Epic of Gilgamesh Excerpt 1

This document, from Tablet I of the epic, introduces us to Gilgamesh’s mother, Ninsun. In the extract, Gilgamesh consults his mother for advice after having vivid dreams. Note the repetitive description of Ninsun as wise and all-knowing.

Gilgamesh got up and revealed the dream, saying to his mother:

"Mother, I had a dream last night. Stars of the sky appeared, and some kind of meteorite of Anu fell next to me. I tried to lift it but it was too mighty for me, I tried to turn it over but I could not budge it. The Land of Uruk was standing around it, the whole land had assembled about it, the populace was thronging around it, the Men clustered about it,and kissed its feet as if it were a little baby (!). I loved it and embraced it as a wife. I laid it down at your feet, and you made it compete with me."

The mother of Gilgamesh, the wise, all-knowing, said to her Lord; Rimat-Ninsun, the wise, all-knowing, said to Gilgamesh:

"As for the stars of the sky that appeared and the meteorite of Anu which fell next to you, you tried to lift but it was too mighty for you, you tried to turn it over but were unable to budge it, you laid it down at my feet, and I made it compete with you, and you loved and embraced it as a wife."

"There will come to you a mighty man, a comrade who saves his friend--he is the mightiest in the land, he is strongest, his strength is mighty as the meteorite of Anu! You loved him and embraced him as a wife; and it is he who will repeatedly save you. Your dream is good and propitious!"

A second time Gilgamesh said to his mother:

"Mother, I have had another dream: At the gate of my marital chamber there lay an axe, and people had collected about it.The Land of Uruk was standing around it, the whole land had assembled about it, the populace was thronging around it. I laid it down at your feet, I loved it and embraced it as a wife, and you made it compete with me."

The mother of Gilgamesh, the wise, all-knowing, said to her son; Rimat-Ninsun, the wise, all-knowing, said to Gilgamesh:

"The axe that you saw (is) a man."... (that) you love him and embrace as a wife, "but (that) I have compete with you. There will come to you a mighty man, a comrade who saves his friend– he is the mightiest in the land, he is strongest, he is as mighty as the meteorite(!) of Anu!"

Gilgamesh spoke to his mother saying:

"By the command of Enlil, the Great Counselor, so may it to pass!"

May I have a friend and adviser, a friend and adviser may I have!

"You have interpreted for me the dreams about him!"

After the harlot recounted the dreams of Gilgamesh to Enkidu the two of them made love.

The Epic of Gilgamesh, Retrieved from http://www.ancienttexts.org/library/mesopotamian/gilgamesh/.

Gilgamesh got up and revealed the dream, saying to his mother:

"Mother, I had a dream last night. Stars of the sky appeared, and some kind of meteorite of Anu fell next to me. I tried to lift it but it was too mighty for me, I tried to turn it over but I could not budge it. The Land of Uruk was standing around it, the whole land had assembled about it, the populace was thronging around it, the Men clustered about it,and kissed its feet as if it were a little baby (!). I loved it and embraced it as a wife. I laid it down at your feet, and you made it compete with me."

The mother of Gilgamesh, the wise, all-knowing, said to her Lord; Rimat-Ninsun, the wise, all-knowing, said to Gilgamesh:

"As for the stars of the sky that appeared and the meteorite of Anu which fell next to you, you tried to lift but it was too mighty for you, you tried to turn it over but were unable to budge it, you laid it down at my feet, and I made it compete with you, and you loved and embraced it as a wife."

"There will come to you a mighty man, a comrade who saves his friend--he is the mightiest in the land, he is strongest, his strength is mighty as the meteorite of Anu! You loved him and embraced him as a wife; and it is he who will repeatedly save you. Your dream is good and propitious!"

A second time Gilgamesh said to his mother:

"Mother, I have had another dream: At the gate of my marital chamber there lay an axe, and people had collected about it.The Land of Uruk was standing around it, the whole land had assembled about it, the populace was thronging around it. I laid it down at your feet, I loved it and embraced it as a wife, and you made it compete with me."

The mother of Gilgamesh, the wise, all-knowing, said to her son; Rimat-Ninsun, the wise, all-knowing, said to Gilgamesh:

"The axe that you saw (is) a man."... (that) you love him and embrace as a wife, "but (that) I have compete with you. There will come to you a mighty man, a comrade who saves his friend– he is the mightiest in the land, he is strongest, he is as mighty as the meteorite(!) of Anu!"

Gilgamesh spoke to his mother saying:

"By the command of Enlil, the Great Counselor, so may it to pass!"

May I have a friend and adviser, a friend and adviser may I have!

"You have interpreted for me the dreams about him!"

After the harlot recounted the dreams of Gilgamesh to Enkidu the two of them made love.

The Epic of Gilgamesh, Retrieved from http://www.ancienttexts.org/library/mesopotamian/gilgamesh/.

Sîn-Lēqi-Unninni: The Epic Of Gilgamesh Excerpt 2

This section introduces Shamhat. Shamhat is the prostitute who transformed Enkidu into a civilized being in the Epic.

Gilgamesh said to the trapper:

"Go, trapper, bring the harlot, Shamhat, with you. When the animals are drinking at the watering place have her take off her robe and expose her sex. When he sees her he will draw near to her, and his animals, who grew up in his wilderness, will be alien to him."

The trapper went, bringing the harlot, Shamhat, with him. They set off on the journey, making direct way. On the third day they arrived at the appointed place, and the trapper and the harlot sat down at their posts(?). A first day and a second they sat opposite the watering hole. The animals arrived and drank at the watering hole, the wild beasts arrived and slaked their thirst with water. Then he, Enkidu, offspring of the mountains, who eats grasses with the gazelles, came to drink at the watering hole with the animals, with the wild beasts he slaked his thirst with water. Then Shamhat saw him--a primitive, a savage fellow from the depths of the wilderness!

"That is he, Shamhat! Release your clenched arms, expose your sex so he can take in your voluptuousness. Do not be restrained--take his energy! When he sees you he will draw near to you. Spread out your robe so he can lie upon you, and perform for this primitive the task of womankind! His animals, who grew up in his wilderness, will become alien to him, and his lust will groan over you."

Shamhat unclutched her bosom, exposed her sex, and he took in her voluptuousness. She was not restrained, but took his energy. She spread out her robe and he lay upon her, she performed for the primitive the task of womankind. His lust groaned over her; for six days and seven nights Enkidu stayed aroused, and had intercourse with the harlot until he was sated with her charms. But when he turned his attention to his animals, the gazelles saw Enkidu and darted off, the wild animals distanced themselves from his body. Enkidu ... his utterly depleted body, his knees that wanted to go off with his animals went rigid; Enkidu was diminished, his running was not as before. But then he drew himself up, for his understanding had broadened. Turning around, he sat down at the harlot's feet, gazing into her face, his ears attentive as the harlot spoke.

The harlot said to Enkidu:

"You are beautiful," Enkidu, you are become like a god. Why do you gallop around the wilderness with the wild beasts? Come, let me bring you into Uruk-Haven, to the Holy Temple, the residence of Anu and Ishtar, the place of Gilgamesh, who is wise to perfection, but who struts his power over the people like a wild bull."

What she kept saying found favor with him. Becoming aware of himself, he sought a friend. Enkidu spoke to the harlot:

"Come, Shamhat, take me away with you to the sacred Holy Temple, the residence of Anu and Ishtar, the place of Gilgamesh, who is wise to perfection, but who struts his power over the people like a wild bull. I will challenge him … Let me shout out in Uruk: I am the mighty one!' Lead me in and I will change the order of things; he whose strength is mightiest is the one born in the wilderness!"

[Shamhat to Enkidu:] "Come, let us go, so he may see your face. I will lead you to Gilgamesh…a man of extreme feelings (!). Look at him, gaze at his face– he is a handsome youth, with freshness(!)... It is Gilgamesh whom Shamhat loves, and Anu, Enlil, and La have enlarged his mind."

The Epic of Gilgamesh, Retrieved from http://www.ancienttexts.org/library/mesopotamian/gilgamesh/.

Gilgamesh said to the trapper:

"Go, trapper, bring the harlot, Shamhat, with you. When the animals are drinking at the watering place have her take off her robe and expose her sex. When he sees her he will draw near to her, and his animals, who grew up in his wilderness, will be alien to him."

The trapper went, bringing the harlot, Shamhat, with him. They set off on the journey, making direct way. On the third day they arrived at the appointed place, and the trapper and the harlot sat down at their posts(?). A first day and a second they sat opposite the watering hole. The animals arrived and drank at the watering hole, the wild beasts arrived and slaked their thirst with water. Then he, Enkidu, offspring of the mountains, who eats grasses with the gazelles, came to drink at the watering hole with the animals, with the wild beasts he slaked his thirst with water. Then Shamhat saw him--a primitive, a savage fellow from the depths of the wilderness!

"That is he, Shamhat! Release your clenched arms, expose your sex so he can take in your voluptuousness. Do not be restrained--take his energy! When he sees you he will draw near to you. Spread out your robe so he can lie upon you, and perform for this primitive the task of womankind! His animals, who grew up in his wilderness, will become alien to him, and his lust will groan over you."

Shamhat unclutched her bosom, exposed her sex, and he took in her voluptuousness. She was not restrained, but took his energy. She spread out her robe and he lay upon her, she performed for the primitive the task of womankind. His lust groaned over her; for six days and seven nights Enkidu stayed aroused, and had intercourse with the harlot until he was sated with her charms. But when he turned his attention to his animals, the gazelles saw Enkidu and darted off, the wild animals distanced themselves from his body. Enkidu ... his utterly depleted body, his knees that wanted to go off with his animals went rigid; Enkidu was diminished, his running was not as before. But then he drew himself up, for his understanding had broadened. Turning around, he sat down at the harlot's feet, gazing into her face, his ears attentive as the harlot spoke.

The harlot said to Enkidu:

"You are beautiful," Enkidu, you are become like a god. Why do you gallop around the wilderness with the wild beasts? Come, let me bring you into Uruk-Haven, to the Holy Temple, the residence of Anu and Ishtar, the place of Gilgamesh, who is wise to perfection, but who struts his power over the people like a wild bull."

What she kept saying found favor with him. Becoming aware of himself, he sought a friend. Enkidu spoke to the harlot:

"Come, Shamhat, take me away with you to the sacred Holy Temple, the residence of Anu and Ishtar, the place of Gilgamesh, who is wise to perfection, but who struts his power over the people like a wild bull. I will challenge him … Let me shout out in Uruk: I am the mighty one!' Lead me in and I will change the order of things; he whose strength is mightiest is the one born in the wilderness!"

[Shamhat to Enkidu:] "Come, let us go, so he may see your face. I will lead you to Gilgamesh…a man of extreme feelings (!). Look at him, gaze at his face– he is a handsome youth, with freshness(!)... It is Gilgamesh whom Shamhat loves, and Anu, Enlil, and La have enlarged his mind."

The Epic of Gilgamesh, Retrieved from http://www.ancienttexts.org/library/mesopotamian/gilgamesh/.

Remedial Herstory Editors. "3. 10,000 BCE THE AGRICULTURAL REVOLUTION: A GREAT MISTAKE? " The Remedial Herstory Project. November 1, 2022. www.remedialherstory.com.

AUTHOR: |

Dr. Nancy Locklin-Sofer

|

Consulting Team |

Editors |

|

Kelsie Brook Eckert, Project Director

Coordinator of Social Studies Education at Plymouth State University Dr. Nancy Locklin-Sofer, Consultant Professor of History at Maryville College. Chloe Gardner, Consultant PhD Candidate in Religious Studies at Edinburgh University Dr. Whitney Howarth, Consultant Former Professor of History at Plymouth State University Jacqui Nelson, Consultant Teaching Lecturer of Military History at Plymouth State University Maria Concepcion Marquez Sandoval PhD Candidate in History at Arizona University |

Ron Kaiser

Humanities Teacher, Moultonborough Academy ReviewersAncient:

Dr. Kristin Heineman Professor of History at Colorado State University Dr. Bonnie Rock-McCutcheon Professor of History at Wilson College Sarah Stone PhD Candidate in Religious Studies at Edinburgh University Medieval: Dr. Katherine Koh Professor of History at La Sierra University Dr. Jonathan Couser Professor of History at Plymouth State University Dr. Shahla Haeri Professor of History at Boston University Lauren Cole PhD Candidate in History at Northwestern University Modern: Dr. Jack Gronau Professor of History at Northeastern University Dr. Barbara Tischler Supervisor for Hunter College Dr. Pamela Scully Professor of Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies and African Studies at Emory University |

|

According to the myth of matriarchal prehistory, men and women lived together peacefully before recorded history. Society was centered around women, with their mysterious life-giving powers, and they were honored as incarnations and priestesses of the Great Goddess. Then a transformation occurred, and men thereafter dominated society.

Women of Babylon is a much-needed historical/art historical study that investigates the concepts of femininity which prevailed in Assyro-Babylonian society. Zainab Bahrani's detailed analysis of how the culture of ancient Mesopotamia defined sexuality and gender roles both in, and through, representation is enhanced by a rich selection of visual material extending from 6500 BC - 1891 AD. Professor Bahrani also investigates the ways in which women of the ancient Near East have been perceived in classical scholarship up to the nineteenth century.

|

Lucy is a 3.2-million-year-old skeleton who has become the spokeswoman for human evolution. She is perhaps the best known and most studied fossil hominid of the twentieth century, the benchmark by which other discoveries of human ancestors are judged.”–From Lucy’s Legacy

Women in Prehistory challenges and undertakes an examination of the archaeological record informed by insights into the cultural construction of gender that have emerged from scholarship in history, anthropology, biology, and related disciplines.

|

The Chalice and the Blade tells a new story of our cultural origins. It shows that warfare and the war of the sexes are neither divinely nor biologically ordained. It provides verification that a better future is possible—and is in fact firmly rooted in the haunting dramas of what happened in our past.

This first comprehensive work on women in pre-Columbian American cultures describes gender roles and relationships in North, Central, and South America from 12,000 B.C. to the A.D. 1500s. Utilizing many key archaeological works, Karen Olsen Bruhns and Karen E. Stothert redress some of the long-standing male bias in writing about ancient Native American lifeways.

|

|

They live in caves and huddle around fires, but they are fully human, though they belong to our most ancient history. Risa the Arbiter has now spent years in her role and is known and respected throughout the area. Her children are half-grown and exhibiting traits of independence, both of thought and action. Her tribe has grown along with her and now needs more than one Arbiter can provide alone. Risa struggles with how best to organize her duties and establishes acolytes in each village to screen petitioners.

|

How to teach with Films:

Remember, teachers want the student to be the historian. What do historians do when they watch films?

- Before they watch, ask students to research the director and producers. These are the source of the information. How will their background and experience likely bias this film?

- Also, ask students to consider the context the film was created in. The film may be about history, but it was made recently. What was going on the year the film was made that could bias the film? In particular, how do you think the gains of feminism will impact the portrayal of the female characters?

- As they watch, ask students to research the historical accuracy of the film. What do online sources say about what the film gets right or wrong?

- Afterward, ask students to describe how the female characters were portrayed and what lessons they got from the film.

- Then, ask students to evaluate this film as a learning tool. Was it helpful to better understand this topic? Did the historical inaccuracies make it unhelpful? Make it clear any informed opinion is valid.

Bibliography

Belfer-Cohen, Anna, & A. Nigel Goring-Morris, “Becoming Farmers: The Inside Story,”Current Anthropology v. 52, No. S4, (October 2011)

Christ, Carol. “Women and Men in Egalitarian Matriarchy,” Feminism and Religion (2018)

Diamond, Jared. “The Worst Mistake in Human History.” Discover Magazine, 1987. http://public.gettysburg.edu/~dperry/Class%20Readings%20Scanned%20Documents/Intro/Diamond.PDF.

Harari, Yuval Noah. “Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind” (2015)

Manning, Richard. “Against the Grain: How Agriculture has Hijacked Civilization” (2004)

Scott, James C. “Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States” (2017)

Strayer, R. and Nelson, E., Ways Of The World. 3rd ed. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2016.

Ungar, Peter S. “Evolutions Bite: A Story of Teeth, Diet, and Human Origins” (2017)

Christ, Carol. “Women and Men in Egalitarian Matriarchy,” Feminism and Religion (2018)

Diamond, Jared. “The Worst Mistake in Human History.” Discover Magazine, 1987. http://public.gettysburg.edu/~dperry/Class%20Readings%20Scanned%20Documents/Intro/Diamond.PDF.

Harari, Yuval Noah. “Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind” (2015)

Manning, Richard. “Against the Grain: How Agriculture has Hijacked Civilization” (2004)

Scott, James C. “Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States” (2017)

Strayer, R. and Nelson, E., Ways Of The World. 3rd ed. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2016.

Ungar, Peter S. “Evolutions Bite: A Story of Teeth, Diet, and Human Origins” (2017)