18. Women and the Great Depression

|

The Great Depression brought a new era of economic reform headed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Although these reforms mainly helped men who were dispositioned, leaving women to fight for themselves. Women entered new job forces and faced struggles men didn't have. They were expected to maintain their houses and families but also work in offices, while also not taking away from a man's chance to provide for his family.

|

|

Frances Perkins

Library Of Congress

Frances Perkins

Library Of Congress

In the years between World War I and World War II, the entire world suffered through one of the greatest economic disasters of the 20th century: The Great Depression. In the United States, this period of uncertainty would prompt some of the greatest attempts on the part of the federal government to provide economic relief to its citizens. However, gender ideologies deeply impacted how that relief was carried out.

On October 29, 1929, later referred to as “Black Tuesday,” the Stock Market crashed. Within hours, billions of dollars of market value disappeared. The US, and the rest of the world, found itself in the midst of one of the greatest economic catastrophes in modern history. After Black Tuesday came years of hard times for the United States, but the country hit its low point between 1932 and 1933. Unemployment had reached 25%. President Hoover’s inaction and philosophy of pulling oneself up from their bootstraps, led to Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s landslide victory in the 1932 election. Struggling Americans were about to see more federal action.

Roosevelt’s Brain Trust:

President Roosevelt did not have a plan to tackle the Depression when he was elected to office, but he filled his cabinet with a variety of progressives--also known as FDR’s “Brain Trust”--who he believed would help shape an effective policy--including the first woman ever to serve in a presidential cabinet: Frances Perkins, Secretary of Labor.

Perkins was a labor rights activist who had previously volunteered at Chicago’s Hull House and served as head of the New York office of the National Consumers’ League. The Depression’s impact on Americans’ everyday lives cannot be overstated. Because of the ultra-high unemployment rates, most Americans found themselves out of work or underemployed. But for women? The Depression’s effects were compounded by existing gender ideologies.

On October 29, 1929, later referred to as “Black Tuesday,” the Stock Market crashed. Within hours, billions of dollars of market value disappeared. The US, and the rest of the world, found itself in the midst of one of the greatest economic catastrophes in modern history. After Black Tuesday came years of hard times for the United States, but the country hit its low point between 1932 and 1933. Unemployment had reached 25%. President Hoover’s inaction and philosophy of pulling oneself up from their bootstraps, led to Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s landslide victory in the 1932 election. Struggling Americans were about to see more federal action.

Roosevelt’s Brain Trust:

President Roosevelt did not have a plan to tackle the Depression when he was elected to office, but he filled his cabinet with a variety of progressives--also known as FDR’s “Brain Trust”--who he believed would help shape an effective policy--including the first woman ever to serve in a presidential cabinet: Frances Perkins, Secretary of Labor.

Perkins was a labor rights activist who had previously volunteered at Chicago’s Hull House and served as head of the New York office of the National Consumers’ League. The Depression’s impact on Americans’ everyday lives cannot be overstated. Because of the ultra-high unemployment rates, most Americans found themselves out of work or underemployed. But for women? The Depression’s effects were compounded by existing gender ideologies.

Women Working, Living New Deal

Women Working, Living New Deal

Most women felt increased family pressures as they tried to make due with reduced income. Furthermore, many women who were immigrants, Black, or simply lower class, already worked for wages outside the home. Aside from that, most women still had their childrearing household obligations, and many of the opportunities that the federal government offered to aid American citizens were closed off to them. Regardless, many women’s ability to earn a wage--in whatever capacity they could--was often essential to helping their families get through this challenging time.

In his first 100 days in office, FDR’s priority was to confront the banking crisis. But his actions in this arena weren’t enough. Congress had to pass laws and create agencies to stimulate the economy, build up infrastructure, put Americans to work, and boost morale. His critics were scathing in their reviews.

New Deal or Raw Deal:

Most Americans are familiar with some of these “Alphabet Agencies,” like the CCC (Civilian Conservation Corps), the PWA (Public Works Administration), and the WPA (Works Progress Administration). These agencies were critically important to stabilizing the economy, but many explicitly excluded women.

The CCC, one of the most well-known, and well-studied agencies of the New Deal, only hired young men between the ages of 17 and 23. The Civil Works Administration (CWA) was a little more lax--but they still almost exclusively hired men. Because of existing gender ideologies, women’s roles were mostly limited to those of housewife and mother. Consequently, those in positions of power didn’t really consider women in an economic recovery package, and many of the New Deal programs were not initially directed at them.

This ‘raw deal’ also extended to Indigenous women as, when the US Department of the Interior created the Indian Division of the Civilian Conservation Corps, women were again excluded. Moreover, while the Indian Division of the CCC was unique insofar as it employed both single and married men over the age of eighteen without any upper limit—it employed more than 85,000 by some estimates—women were disregarded despite the fact that amongst many Indigenous cultures, they traditionally worked in the fields whilst farming and/or gathering, joined men on hunts, etc. In short, the exclusion of Indigenous women was a continuation of the American government’s policy of both explicit and implicit gendered assimilation.

In his first 100 days in office, FDR’s priority was to confront the banking crisis. But his actions in this arena weren’t enough. Congress had to pass laws and create agencies to stimulate the economy, build up infrastructure, put Americans to work, and boost morale. His critics were scathing in their reviews.

New Deal or Raw Deal:

Most Americans are familiar with some of these “Alphabet Agencies,” like the CCC (Civilian Conservation Corps), the PWA (Public Works Administration), and the WPA (Works Progress Administration). These agencies were critically important to stabilizing the economy, but many explicitly excluded women.

The CCC, one of the most well-known, and well-studied agencies of the New Deal, only hired young men between the ages of 17 and 23. The Civil Works Administration (CWA) was a little more lax--but they still almost exclusively hired men. Because of existing gender ideologies, women’s roles were mostly limited to those of housewife and mother. Consequently, those in positions of power didn’t really consider women in an economic recovery package, and many of the New Deal programs were not initially directed at them.

This ‘raw deal’ also extended to Indigenous women as, when the US Department of the Interior created the Indian Division of the Civilian Conservation Corps, women were again excluded. Moreover, while the Indian Division of the CCC was unique insofar as it employed both single and married men over the age of eighteen without any upper limit—it employed more than 85,000 by some estimates—women were disregarded despite the fact that amongst many Indigenous cultures, they traditionally worked in the fields whilst farming and/or gathering, joined men on hunts, etc. In short, the exclusion of Indigenous women was a continuation of the American government’s policy of both explicit and implicit gendered assimilation.

FERA Camp, History.com

FERA Camp, History.com

Some women did get to take advantage of New Deal programs--mostly via the Works Progress Administration. Some of the best-known WPA projects were federal artistic projects like theater, music, dance, murals, and historical or tourist guidebooks. However, even at the program’s peak, women only represented about 14% of WPA employees.

Generally, women were limited to jobs that fit within existing gender ideologies. They were considered unsuitable for physically-demanding jobs like heavy construction. In Federal Emergency Relief Administration (or FERA) Camps, women’s work included canning foods, sewing, producing clothes and mattresses, or working as housekeeping aides for families in need of additional help. Of course, these gender limitations on women were compounded with racial stereotypes. For example, most of the FERA employees who worked as housekeeping aides were African American women.

It’s difficult to measure the New Deal’s impact on women, when--essentially--the New Deal wasn’t written for them, or with them in mind. Between 1932 and 1937, there were laws against more than one person per married couple working for the federal civil service. Since the National Recovery Administration set lower minimum wages for women than men performing the same jobs it rarely made sense for women to keep their jobs over their husbands’ higher paying work.

Generally, women were limited to jobs that fit within existing gender ideologies. They were considered unsuitable for physically-demanding jobs like heavy construction. In Federal Emergency Relief Administration (or FERA) Camps, women’s work included canning foods, sewing, producing clothes and mattresses, or working as housekeeping aides for families in need of additional help. Of course, these gender limitations on women were compounded with racial stereotypes. For example, most of the FERA employees who worked as housekeeping aides were African American women.

It’s difficult to measure the New Deal’s impact on women, when--essentially--the New Deal wasn’t written for them, or with them in mind. Between 1932 and 1937, there were laws against more than one person per married couple working for the federal civil service. Since the National Recovery Administration set lower minimum wages for women than men performing the same jobs it rarely made sense for women to keep their jobs over their husbands’ higher paying work.

Frances Perkins, Library of Congress

Frances Perkins, Library of Congress

“Pin-Money” Workers:

How did the first female presidential cabinet member, Frances Perkins, feel about this?

Well, it’s complicated. Surprisingly, Perkins shared some of the same anti-work for women views as many of her male colleagues--particularly for married women. At one point, she even said:

“the woman ‘pin-money worker’ who competes with the necessity worker is a menace to society, a selfish, shortsighted creature, who ought to be ashamed of herself.”

While Perkins’ statement might sound like an indictment against women workers, she was mostly opposed to married women who held jobs. Perkins also said:

“I am not willing to encourage those who are under no economic necessities to compete with their charm and education, their superior advantages, against the working girl who has only her two hands.”

Basically Perkins believed if women were married, ideally, they wouldn’t need to work. Their husbands should provide for them. However, if women were alone, they needed the ability to earn a decent living to protect themselves.

Perkins certainly wasn’t the only one displeased with working women. The targeting of women workers was broad scapegoating. Traditionally “women’s jobs” were less connected to the stock market, and less affected by its crash, than, say: coal mining or manufacturing. So while many men were losing their jobs, women in some “women’s industries” simply weren’t! This point was lost on many, though. Journalist Norman Cousins once wrote, “Simply fire the women, who shouldn’t be working anyway, and hire the men. Presto! No unemployment. No relief rolls. No Depression.” Cousins’ short-sighted comment ignored that a coal miner or steel worker couldn’t (or wouldn’t) exactly fit the job requirements of a clerical worker or nurse.

How did the first female presidential cabinet member, Frances Perkins, feel about this?

Well, it’s complicated. Surprisingly, Perkins shared some of the same anti-work for women views as many of her male colleagues--particularly for married women. At one point, she even said:

“the woman ‘pin-money worker’ who competes with the necessity worker is a menace to society, a selfish, shortsighted creature, who ought to be ashamed of herself.”

While Perkins’ statement might sound like an indictment against women workers, she was mostly opposed to married women who held jobs. Perkins also said:

“I am not willing to encourage those who are under no economic necessities to compete with their charm and education, their superior advantages, against the working girl who has only her two hands.”

Basically Perkins believed if women were married, ideally, they wouldn’t need to work. Their husbands should provide for them. However, if women were alone, they needed the ability to earn a decent living to protect themselves.

Perkins certainly wasn’t the only one displeased with working women. The targeting of women workers was broad scapegoating. Traditionally “women’s jobs” were less connected to the stock market, and less affected by its crash, than, say: coal mining or manufacturing. So while many men were losing their jobs, women in some “women’s industries” simply weren’t! This point was lost on many, though. Journalist Norman Cousins once wrote, “Simply fire the women, who shouldn’t be working anyway, and hire the men. Presto! No unemployment. No relief rolls. No Depression.” Cousins’ short-sighted comment ignored that a coal miner or steel worker couldn’t (or wouldn’t) exactly fit the job requirements of a clerical worker or nurse.

Eleanor Roosevelt, Library of Congress

Eleanor Roosevelt, Library of Congress

The New Deal’s effect on women cannot just be determined by job quotas or gendered minimum wages. The Social Security Act--one of the landmark pieces of New Deal legislation--and the Fair Labor Standards Act did not initially even cover sectors of employment where women were disproportionately represented: agricultural work and domestic service. Furthermore, women who were not dependent on men got fewer Social Security benefits. This weird program structure seemed to suggest women deserved economic rights only in relation to men. They were often forced to take on more central roles within their homes and families--playing unrecognized roles in helping the country through the Great Depression. Or, they were working for less money than male peers and possibly being despised just for having jobs at all. Although the Depression was a time for many strong women to step up to the plate in their homes and workplaces, ultimately, the Depression did not subvert traditional gender roles--it reinforced them.

It’s Up to Women:

However, in 1933, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt wrote It’s Up to the Women. This was really the first time a first lady took action to speak on a current crisis. Women were rarely in positions of power to speak out, so Eleanor Roosevelt’s actions were quite modern and reshaped our expectations for White House First Ladies.

In It’s Up to the Women, Roosevelt provided a handbook for women during the Great Depression. It was inspirational at times, but mostly, it was practical. It provided inexpensive meal plans, recipes, instructions, and most importantly put forward the idea that women did have power to shape their homes and their destinies. She believed these trying times would just help women forge strong characters. She wrote, “The women know that life must go on and that the needs of life must be met and it is their courage and determination which, time and again, have pulled us through worse crises than the present one.”

It’s important to remember, as we’ve already touched on, women’s experiences of this hard time varied greatly based on many factors. Women’s age, marital status, geographic location, race, and ethnicity all affected how complicated a woman’s chance at surviving difficult Depression circumstances were. For example, an urban housewife with electricity and running water might have been struggling, but she arguably still had an easier time than a similarly struggling rural woman...who also had to deal with the lack of these conveniences.

It’s Up to Women:

However, in 1933, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt wrote It’s Up to the Women. This was really the first time a first lady took action to speak on a current crisis. Women were rarely in positions of power to speak out, so Eleanor Roosevelt’s actions were quite modern and reshaped our expectations for White House First Ladies.

In It’s Up to the Women, Roosevelt provided a handbook for women during the Great Depression. It was inspirational at times, but mostly, it was practical. It provided inexpensive meal plans, recipes, instructions, and most importantly put forward the idea that women did have power to shape their homes and their destinies. She believed these trying times would just help women forge strong characters. She wrote, “The women know that life must go on and that the needs of life must be met and it is their courage and determination which, time and again, have pulled us through worse crises than the present one.”

It’s important to remember, as we’ve already touched on, women’s experiences of this hard time varied greatly based on many factors. Women’s age, marital status, geographic location, race, and ethnicity all affected how complicated a woman’s chance at surviving difficult Depression circumstances were. For example, an urban housewife with electricity and running water might have been struggling, but she arguably still had an easier time than a similarly struggling rural woman...who also had to deal with the lack of these conveniences.

Charlotta Bass, Wikimedia Commons

Charlotta Bass, Wikimedia Commons

The typical married woman in the 1930s had a husband who was still employed, but who likely took a pay cut or reduced hours to keep his job. If he had lost his job, often the family had enough resources to survive without going on relief or losing all their possessions. Nearly every woman, rich or poor, faced a reduction in income.

Women and the Black Economy:

For some women, though, this reduction of income and the effects of the Depression were more extreme than others. Many Black Americans obviously experienced the Depression differently than white people. Many of them were already struggling under the yoke of discrimination and prejudice. Even before Black Tuesday, Black Americans had way fewer job options than white people. Many Black men worked in service industries that were particularly susceptible to difficult economic times. Chauffeurs, gardeners, and Pullman Porters were often some of the first to lose their jobs when their employers faced a reduction in income. Times were already hard, but then they became harder.

Charlotta Bass was born in Sumter, South Carolina in 1874. In 1910, she moved to Los Angeles, California where she became the owner of the California Eagle, a Los Angeles-based newspaper for L.A.’s growing African American community. She became a prominent figure in the community and organized a campaign to promote Black employment. By urging her readers to only shop at places that hire Black employees, she sought to reinvigorate the insular Black economy in Los Angeles.

Her efforts were mirrored in other communities with large African American populations. These movements did make change, but overall, Black Americans still had an unemployment rate that was twice that of white Americans, while simultaneously benefiting less from government relief and public works projects than their white counterparts–many of the alphabet agencies we discussed implemented racial quotas that mirrored the racial proportions of the population. The CCC, for example, limited Black workers to a maximum of 10% of the labor force.

Meanwhile, President Roosevelt was at least attempting to improve Black rights in the US. He himself hired Black Americans and placed critics of segregation, disenfranchisement, and lynching in key positions in his administration. One of these additions was Mary McLeoud Bethune. Bethune was born in South Carolina to former enslaved persons and eventually became one of the most well known educators and civil rights leaders of the 20th century. Bethune may have been Roosevelt’s advisor on minority affairs, but her appointment was a major step for Black women.

Women and the Black Economy:

For some women, though, this reduction of income and the effects of the Depression were more extreme than others. Many Black Americans obviously experienced the Depression differently than white people. Many of them were already struggling under the yoke of discrimination and prejudice. Even before Black Tuesday, Black Americans had way fewer job options than white people. Many Black men worked in service industries that were particularly susceptible to difficult economic times. Chauffeurs, gardeners, and Pullman Porters were often some of the first to lose their jobs when their employers faced a reduction in income. Times were already hard, but then they became harder.

Charlotta Bass was born in Sumter, South Carolina in 1874. In 1910, she moved to Los Angeles, California where she became the owner of the California Eagle, a Los Angeles-based newspaper for L.A.’s growing African American community. She became a prominent figure in the community and organized a campaign to promote Black employment. By urging her readers to only shop at places that hire Black employees, she sought to reinvigorate the insular Black economy in Los Angeles.

Her efforts were mirrored in other communities with large African American populations. These movements did make change, but overall, Black Americans still had an unemployment rate that was twice that of white Americans, while simultaneously benefiting less from government relief and public works projects than their white counterparts–many of the alphabet agencies we discussed implemented racial quotas that mirrored the racial proportions of the population. The CCC, for example, limited Black workers to a maximum of 10% of the labor force.

Meanwhile, President Roosevelt was at least attempting to improve Black rights in the US. He himself hired Black Americans and placed critics of segregation, disenfranchisement, and lynching in key positions in his administration. One of these additions was Mary McLeoud Bethune. Bethune was born in South Carolina to former enslaved persons and eventually became one of the most well known educators and civil rights leaders of the 20th century. Bethune may have been Roosevelt’s advisor on minority affairs, but her appointment was a major step for Black women.

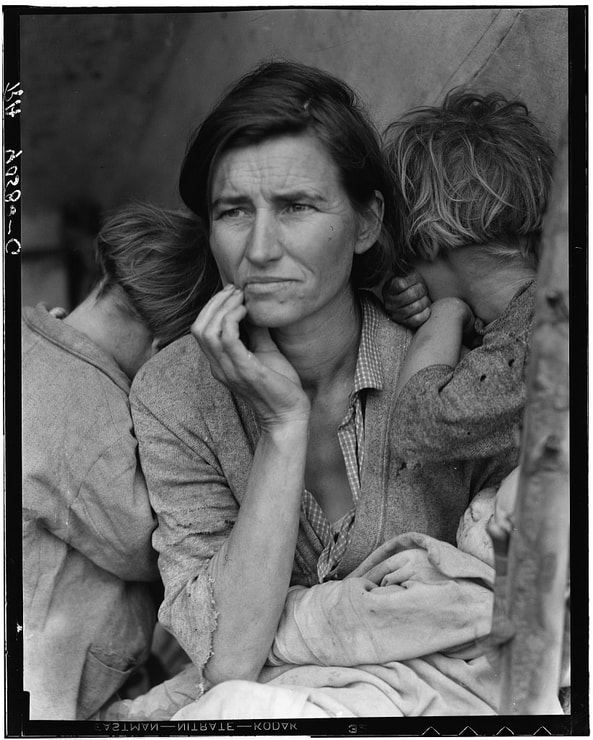

The Migrant Mother, Library of Congress

The Migrant Mother, Library of Congress

The Migrant Mother:

Farm families also struggled beyond the typical American family with declining agricultural prices, foreclosures, and drought. Their plight became visible to the rest of Americans through photographer Dorothea Lange’s “Migrant Mother”. In 1936, Lange was hired by the Farm Security Administration (FSA) to photograph migrant workers to raise awareness and urge the federal government to provide them with aid. Lange went to Nipomo, California where she encountered Florence Owens Thompson, the subject of the notorious photograph.

While Roosevelt envisioned the New Deal as a broad support package to help as many Americans as possible, there were limits. Ultimately, cultural norms about race and gender shaped legislation. The ideal of a male-headed household certainly shaped policy and resulted in few women being covered by things like Social Security on their own.

However, the New Deal brought some progress to women. More women earned government positions than in any previous administration, and the First Lady used her power to push for reform in civil rights and labor laws. But on the flip side, there was no organized feminist movement in the 1930s, and the many calls for women--particularly married women--to exit the work force were anti-feminist.

Farm families also struggled beyond the typical American family with declining agricultural prices, foreclosures, and drought. Their plight became visible to the rest of Americans through photographer Dorothea Lange’s “Migrant Mother”. In 1936, Lange was hired by the Farm Security Administration (FSA) to photograph migrant workers to raise awareness and urge the federal government to provide them with aid. Lange went to Nipomo, California where she encountered Florence Owens Thompson, the subject of the notorious photograph.

While Roosevelt envisioned the New Deal as a broad support package to help as many Americans as possible, there were limits. Ultimately, cultural norms about race and gender shaped legislation. The ideal of a male-headed household certainly shaped policy and resulted in few women being covered by things like Social Security on their own.

However, the New Deal brought some progress to women. More women earned government positions than in any previous administration, and the First Lady used her power to push for reform in civil rights and labor laws. But on the flip side, there was no organized feminist movement in the 1930s, and the many calls for women--particularly married women--to exit the work force were anti-feminist.

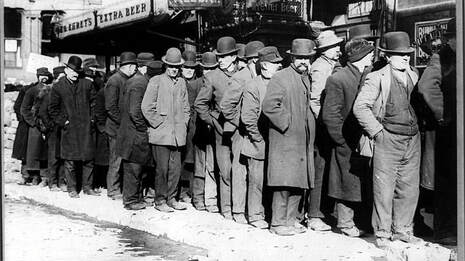

Men in a Breadline, SWHP

Men in a Breadline, SWHP

Aside from Lange’s “Migrant Mother”, another iconic image from the Depression is the newly unemployed, downwardly mobile, breadline-waiting “Forgotten Man.” In hindsight it’s difficult to understand how most folks could look at this photo and feel empathy, but many would look at a photo of a woman in the same situation, desperately looking for work, and find her greedy or entitled. Nevertheless, women’s wages were crucial to families’ survival during the Depression, so the realities of the economy continued to pressure women to find paid work whenever, and wherever, they could. Once again, the Depression proved, despite cultural stereotypes, women work.

Conclusion:

By the end of this era, so much remained in question. How did gender roles ultimately shape public policy? How did racial ideologies impact the roll out of the New Deal? What did the federal government’s neglect of women say about their status as citizens? While social factors were demanding that married women leave the workforce, economic factors were compelling them to work.How did federal programs fail to see the role that women played in the economy?

Conclusion:

By the end of this era, so much remained in question. How did gender roles ultimately shape public policy? How did racial ideologies impact the roll out of the New Deal? What did the federal government’s neglect of women say about their status as citizens? While social factors were demanding that married women leave the workforce, economic factors were compelling them to work.How did federal programs fail to see the role that women played in the economy?

Draw your own conclusions

|

Learn how to teach with inquiry.

Many of these lesson plans were sponsored in part by the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources Eastern Region Program, coordinated by Waynesburg University, the History and Social Studies Education Faculty at Plymouth State University, and the Patrons of the Remedial Herstory Project. |

Lesson Plans from Other Organizations

- The National Women's History Museum has lesson plans on women's history.

- The Guilder Lehrman Institute for American History has lesson plans on women's history.

- The NY Historical Society has articles and classroom activities for teaching women's history.

- Unladylike 2020, in partnership with PBS, has primary sources to explore with students and outstanding videos on women from the Progressive era.

- The Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media has produced recommendations for teaching women's history with primary sources and provided a collection of sources for world history. Check them out!

- The Stanford History Education Group has a number of lesson plans about women in World History.

Period Specific Lesson Plans from Other Organizations

- National History Day: Jeannette Rankin (1880-1973) was born and raised in Montana. While studying social work at the University of Washington, she joined the woman suffrage movement. Soon after, she became a field secretary for the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). She traveled across the United States, advocating for suffrage. In 1916, she was elected as the first woman in the U.S. House of Representatives. Just three days after being sworn in, she cast one of two votes that would define public memory of her service - a vote against the American declaration of war on Germany in World War I. Rankin introduced a voting rights amendment that passed the House in 1918, and was the only woman in Congress to cast a vote for woman suffrage. She unsuccessfully ran for U.S. Senate in 1918, and spent the next two decades advocating for peace and social welfare. In 1940, she was again elected to the House, and in 1941, cast the only vote against the declaration of war on Japan. She left Congress in 1942, and remained active in anti-war movements and the philosophy of nonviolent protest for the rest of her life. She died in California in 1973.

- Unladylike: Learn how Jeannette Rankin became the first woman in United States history elected to the U.S. Congress, representing the state of Montana in the U.S. House of Representatives, in this video from Unladylike2020. As a suffragist and life-long pacifist, Rankin fought tirelessly for women’s right to vote, and voted against United States entry into WWI and WWII. Utilizing video, discussion questions, vocabulary, and teaching tips, students learn about Rankin’s role in securing women the vote nationally, and her enduring commitment to ending war.

- Great Depression:

- Gilder Lehrman: The greatest economic calamity in the history of the United States occurred in the third decade of the twentieth century. When the stock market crashed in 1929 and the economy plummeted over the next few years, the nation sunk into the most pervasive depression in American history. No one escaped the suffering that the Great Depression produced. The ranks of the suffering went well beyond those who lost everything as a direct result of the stock market crash. While millions lost their fortunes in investments on and after October of 1929, many more lost their savings when banks collapsed and their livelihoods when whole industries failed and businesses closed their doors. The drought that hit the Midwest produced additional suffering. By 1932, every economic sector and geographic region in the country was in dire condition. Few persons escaped the disastrous effects of the depression. The hardship of unemployment, the loss of homes and farms, and the lack of institutions that could provide adequate assistance were central to the pain caused by the economic crisis. The personal cost was perhaps greatest to the part of the population on the margin of economic activity. Though women were often faced with caring for families without income from employment or traditional support, the vast majority of the government’s recovery efforts were directed at bringing life to the economy, and men were the primary recipients of these efforts. In this lesson, we will consider the lives of the millions of women in need during the depression. In order to understand the impact of the Great Depression on women, we will read accounts, look at images, and evaluate programs directed toward some of those women. Finally we will analyze society’s expectations of women before, during, and after the Great Depression.

- Stanford History Education Group: Dorothea Lange’s iconic “Migrant Mother” photograph is often used to illustrate the toll of the Great Depression, but many neglect to examine the photograph as historical evidence. This lesson asks students to think carefully about the strengths and weaknesses of the photo as evidence of the conditions facing migrant workers during the Great Depression.

- Eleanor Roosevelt:

- Gilder Lehrman: Students will be asked to read and analyze primary and secondary sources about Eleanor Roosevelt and the work she did to support social justice issues both in the United States and around the world. They will look at the role of first lady and see how Mrs. Roosevelt expanded that role to influence the political, social, and economic issues of the twentieth century. Students will increase their literacy skills as outlined in the Common Core Standards as they explore the social justice actions taken by Eleanor Roosevelt, which at times changed the course of world events.

- Edcitement: This lesson asks students to explore the various roles that Eleanor Roosevelt took on, among them: First Lady, political activist for civil rights, newspaper columnist and author, and representative to the United Nations. Students will read and analyze materials written by and about Eleanor Roosevelt to understand the changing roles of women in politics. They will look at Eleanor Roosevelt's role during and after the New Deal as well as examine the lives and works of influential women who were part of her political network. They will also examine the contributions of women in Roosevelt's network who played critical roles in shaping and administering New Deal policies.

- National Womens History Museum: The purpose of this lesson is to learn about Eleanor Roosevelt as an agent of social change as the First Lady of the United States and later as a representative to the United Nations. Moreover, students will learn how Mrs. Roosevelt used her position as the First Lady to become a champion of human rights which extended after her time in the White House. Students will read primary sources to better understand the legacy of Mrs. Roosevelt.

- Mary McLeod Bethune:

- Teaching Tolerance: In this lesson, students will read an excerpt of an interview given by Mary McLeod Bethune and will learn that she founded the Daytona National and Industrial School for Negro Girls (now Bethune-Cookman College) in 1904. Through close reading, they will explore and discuss connections between events from Bethune’s life experiences and their own lives, and connections between past and current events.

- National History Day: Mary McLeod Bethune (1875-1955) was born in South Carolina to parents who were former slaves. From childhood Bethune realized that education held the key for African American advancement. In 1904, she founded the Daytona Literary and Industrial Training School for Negro Girls. Her school grew rapidly, and in the 1920s merged with the all-male Cookman Institute; Mary McLeod Bethune served as the first president of the new Bethune-Cookman College. Bethune worked tirelessly for civil rights, women’s rights, and social justice. She served on commissions under Presidents Coolidge and Hoover, and in 1936 Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed her the Director of the Division of Negro Affairs, part of the National Youth Administration, a New Deal program designed to help young people find jobs. Bethune became the first African American woman to serve as head of a federal agency and used her position to persistently lobby for African American issues. She founded the National Council for Negro Women in 1935, co-founded the United Negro College Fund in 1944, and attended the founding conference of the United Nations in 1949. Before her death in 1955, Bethune wrote a last will and testament that expressed her hope for a “world of Peace, Progress, Brotherhood, and Love.”

WOmen and the Depression

Interview with Mrs. Marie Haggerty, A Maid

Q: "When you worked as a maid, did you mainly do housework?"

A: "But my dear, it wasn't housework I did...I was a nurse maid or a second girl--never just an ordinary girl out to service...You got hired by your looks and even if you looked honest, they would test you out. Why, once I was making up a bed, and right beside the bed was a five dollar bill. I knowed nobody dropped that for nuthin', so I didn't know if I should pick it up and tell them, or what, but my face burnt like fire, for I knowed I was gettin' tested."

Library of Congress. "Women and Work: Mrs. Marie Haggerty, Maid."

https://www.loc.gov/collections/federal-writers-project/articles-and-essays/women-and-work/.

Guiding Questions

A: "But my dear, it wasn't housework I did...I was a nurse maid or a second girl--never just an ordinary girl out to service...You got hired by your looks and even if you looked honest, they would test you out. Why, once I was making up a bed, and right beside the bed was a five dollar bill. I knowed nobody dropped that for nuthin', so I didn't know if I should pick it up and tell them, or what, but my face burnt like fire, for I knowed I was gettin' tested."

Library of Congress. "Women and Work: Mrs. Marie Haggerty, Maid."

https://www.loc.gov/collections/federal-writers-project/articles-and-essays/women-and-work/.

Guiding Questions

- How does Haggerty’s work reflect the idea of “women’s work”?

- How does she describe herself and her work?

- Why does she correct the interviewer when they refer to her work as “housework”?

The Women's Bureau: High Spots in Legislation Affecting Women

The outlook for 1938 is the brighter for women at work because of the impressive number of new laws on subjects affecting working women that were passed in the 46 legislatures in session in the past year. The new laws enacted deal with the important subjects of minimum wage, hours, home work, and night work, which past experience has shown as having notable effect in raising the working standards for employed women. They also include other subjects of great import to employed women, as unemployment compensation (all 48 States now have legislation on this subject), old-age assistance, workmen’s compensation, wage payments, safety, health and sanitation, occupational diseases, and collective bargaining.

Probably the most comprehensive legislation along these lines was enacted in Pennsylvania and Illinois, the former having passed, among other bills, a minimum-wage act and a new hour law with wide coverage, and the latter a new hour law (weekly hours being fixed for the first time), each State putting the enforcement of these laws in a special branch of the labor department….

In estimating what progress for employed women has been made in States during the past year, it is certain that the administration of laws is of importance equal to their enactment. This year significant steps have been taken to insure more adequate enforcement. Outstanding among the recent measures is the action in two States that have established new divisions for women and minors, Illinois and Utah. Equally important to employed women are the minimum-wage bureaus created this year in Colorado, Connecticut, and the District of Columbia; and Pennsylvania reorganized its department of labor so as to include a separate bureau for law enforcement on wages and hours.

Of very great help to employed women will be the complete reorganization of the labor-law administrative bodies that has taken place this year in Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, and Indiana, where the administrative functions are now so unified as to establish a more effective central agency.

The Women's Bureau. "High Spots in Legislation Affecting Women." The Woman Worker, January 1938.

https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/files/docs/publications/women/newsletter/dolwb_womanworker_193801.pdf?utm_source=direct_download.

Questions

Probably the most comprehensive legislation along these lines was enacted in Pennsylvania and Illinois, the former having passed, among other bills, a minimum-wage act and a new hour law with wide coverage, and the latter a new hour law (weekly hours being fixed for the first time), each State putting the enforcement of these laws in a special branch of the labor department….

In estimating what progress for employed women has been made in States during the past year, it is certain that the administration of laws is of importance equal to their enactment. This year significant steps have been taken to insure more adequate enforcement. Outstanding among the recent measures is the action in two States that have established new divisions for women and minors, Illinois and Utah. Equally important to employed women are the minimum-wage bureaus created this year in Colorado, Connecticut, and the District of Columbia; and Pennsylvania reorganized its department of labor so as to include a separate bureau for law enforcement on wages and hours.

Of very great help to employed women will be the complete reorganization of the labor-law administrative bodies that has taken place this year in Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, and Indiana, where the administrative functions are now so unified as to establish a more effective central agency.

The Women's Bureau. "High Spots in Legislation Affecting Women." The Woman Worker, January 1938.

https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/files/docs/publications/women/newsletter/dolwb_womanworker_193801.pdf?utm_source=direct_download.

Questions

- Why were labor laws created just for women?

- How might distinctions based on gender help women?

- How might distinctions based on gender harm women?

- How do these new laws show how women were either disregarded or mistreated in the past in the workplace?

The NEw Deal

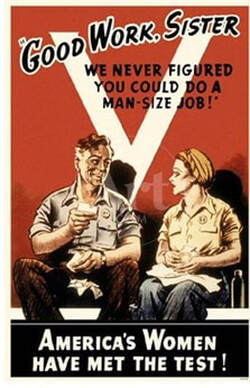

Bressler Editorial Cartoons: Good Work, Sister

Guiding Questions

New York : Bressler Editorial Cartoons, Inc. "Good work, sister: we never figured you could do a man-size job!" America's women have met the test! 1944. Illustration. https://www.loc.gov/item/97515638/.

- How does this image portray the relationship between America and working women going into the New Deal era?

New York : Bressler Editorial Cartoons, Inc. "Good work, sister: we never figured you could do a man-size job!" America's women have met the test! 1944. Illustration. https://www.loc.gov/item/97515638/.

Jack Delano: Women Workers

Questions:

Delano, Jack. Women workers employed as wipers in the roundhouse having lunch in their restroom, C. &

N.W. R.R., Clinton, Iowa. April 1943. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/resource/fsac.1a34808/

- How does this image speak to the growing acceptance of women workers in this time?

Delano, Jack. Women workers employed as wipers in the roundhouse having lunch in their restroom, C. &

N.W. R.R., Clinton, Iowa. April 1943. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/resource/fsac.1a34808/

Mary McLeod Bethune: Letter to FDR

Mary McLeod Bethune was and African-American activist, educator, and federal appointee. In the 1930s she served as director of the National Youth Administration’s Negro Division, part of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal.

June 4, 1940

My Dear Mr. President:

At a time like this… I approach you as one of a vast army of Negro women who recognize that we must face the dangers that confront us with a united patriotism.

We, as a race, have been fighting for a more equitable share of those opportunities which are fundamental to every American citizen who would enjoy the economic and family security which a true democracy guarantees. Now we come as a group of loyal, self-sacrificing women who feel they have a right and a solemn duty to serve their nation.

In the ranks of Negro womanhood in America are to be found ability and capacity for leadership, for administrative as well as routine tasks, for the types of service so necessary in a program of national defense. These are citizens whose past records at home and in war service abroad, whose unquestioned loyalty to their country and Its ideals, and whose sincere and enthusiastic desire to serve you and the nation indicate how deeply they are concerned that a more realistic American democracy, as visioned by those not blinded by racial prejudices, shall be maintained and perpetuated.

I offer my own services without reservation, and urge you: In the planning and work which lies ahead, to make such use of the services of qualified Negro women as will assure the thirteen and a half million Negroes In America that they, too, have earned the right to be numbered among the active forces who are working towards the protection of our democratic stronghold.

Faithfully yours,

Mary McLeod Bethune

McLeod Bethune, Mary. Letter to Theodore Roosevelt, June 4, 1940.

https://bcc-cuny.digication.com/ushistoryreader/Mary_McLeod_Bethune_Letter_to_Roosevelt.

Questions

June 4, 1940

My Dear Mr. President:

At a time like this… I approach you as one of a vast army of Negro women who recognize that we must face the dangers that confront us with a united patriotism.

We, as a race, have been fighting for a more equitable share of those opportunities which are fundamental to every American citizen who would enjoy the economic and family security which a true democracy guarantees. Now we come as a group of loyal, self-sacrificing women who feel they have a right and a solemn duty to serve their nation.

In the ranks of Negro womanhood in America are to be found ability and capacity for leadership, for administrative as well as routine tasks, for the types of service so necessary in a program of national defense. These are citizens whose past records at home and in war service abroad, whose unquestioned loyalty to their country and Its ideals, and whose sincere and enthusiastic desire to serve you and the nation indicate how deeply they are concerned that a more realistic American democracy, as visioned by those not blinded by racial prejudices, shall be maintained and perpetuated.

I offer my own services without reservation, and urge you: In the planning and work which lies ahead, to make such use of the services of qualified Negro women as will assure the thirteen and a half million Negroes In America that they, too, have earned the right to be numbered among the active forces who are working towards the protection of our democratic stronghold.

Faithfully yours,

Mary McLeod Bethune

McLeod Bethune, Mary. Letter to Theodore Roosevelt, June 4, 1940.

https://bcc-cuny.digication.com/ushistoryreader/Mary_McLeod_Bethune_Letter_to_Roosevelt.

Questions

- How does Mary McLeod Bethune argue that Black people have been systematically disadvantaged in the Great Depression?

- What are some qualities listed by McLeod Bethune that she feels justify the equal treatment of Black workers, particularly Black women, in the New Deal Era?

Frances Perkins: Speech

Frances Perkins was the first woman ever appointed to the President’s cabinet in US history and was the vocal, sometimes unpopular force behind New Deal policies. She was appointed Secretary of Labor, which was especially shocking considering the employment crisis that came along with the Great Depression. She began her career working in the Chicago Hull House in the early 1900s. She then served as head of the Philadelphia Research and Protective Association fighting against the abduction of newly arrived immigrant and Black women into prostitution. She led the New York Consumers’ League, and witnessed the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire. Perkins would later note that March 25, 1911—the day of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire—was “the day the New Deal was born.” Perkins was one of the main reasons that the Social Security Administration survived. Yet, she was not always friendly to women workers. In this passage she laments married women who held jobs– even though she herself was a married working woman. There was a prevailing belief that married women should be homemakers.

The ‘woman pin-money worker’ who competes with the necessity worker is a menace to society, a selfish, shortsighted creature, who ought to be ashamed of herself… Until we have every woman in this community earning a living wage…I am not willing to encourage those who are under no economic necessities to compete with their charm and education, their superior advantages, against the working girl who has only her two hands.

*refers to the small amounts of money women spent on fancy items, the term was shorthand for women’s earnings in an effort to diminish its importance and contrast it with “bread winning.”

In Blakemore, Erin. “Why Many Married Women Were Banned From Working During the Great Depression: With millions of Americans unable to find employment, working wives became scapegoats.” November 8, 2021. https://www.history.com/news/great-depression-married-women-employment.

Questions

The ‘woman pin-money worker’ who competes with the necessity worker is a menace to society, a selfish, shortsighted creature, who ought to be ashamed of herself… Until we have every woman in this community earning a living wage…I am not willing to encourage those who are under no economic necessities to compete with their charm and education, their superior advantages, against the working girl who has only her two hands.

*refers to the small amounts of money women spent on fancy items, the term was shorthand for women’s earnings in an effort to diminish its importance and contrast it with “bread winning.”

In Blakemore, Erin. “Why Many Married Women Were Banned From Working During the Great Depression: With millions of Americans unable to find employment, working wives became scapegoats.” November 8, 2021. https://www.history.com/news/great-depression-married-women-employment.

Questions

- Why was Perkins concerned about married women working?

- Which women was she advocating for?

Congress: Economy Act 1932 Section 213

This document discusses a law passed just before President Roosevelt came into office, but reflective of the sentiments of the time.

Probably one of the most tragic cases ever encountered by the National Woman's Party, was -

Section 213, Married Persons Clause, Economy Act of 1932.

The purpose of this Act was to reduce existing personnel where a husband and wife were both in the service, to create positions for those unemployed. The Act read:

"In any reduction of personnel in any branch of the service of the United States Government or the District of Columbia, married persons (living with husband or wife), employed in the class to be reduced shall be dismissed before any other person employed in such class is dismissed, if such husband or wife is also in the service of the United States or the District of Columbia."

Perhaps this would have been a solution of the unemployment problem, except, it should be remembered, these were the Depression Years… "I was there" and a witness to the tragedy which befell some of my friends and I suffered for them. I knew young women who had come to Washington and entered the Government service because it was necessary to help their families who were victims of the Depression. I knew young women receiving $100 a month who sent from $25 to $50 a month to their families and lived on the balance. Some were married when they came to Washington with husbands in the Combat services, others married later, but in so many cases both husbands and wives had to contribute to the support of their families "back home."

The Government Workers Council of the National Woman's Party, headed by Mrs. Edwina Avery, a lawyer and a Government worker, were given an office on the ground floor of our Page Eight Headquarters, from which they conducted a long and strenuous campaign to repeal Section 213… Before the end of the fight many other women's organizations had joined us in protest against Section 213.

Finally, after a vigorous struggle lasting five years, a Bill to repeal Section 213 was passed by the House on June 5, 1937, by a vote of 206 and 128; was unanimously passed by the Senate on July 23, 1937 and signed by President Franklin Roosevelt on July 26, 1937 - thus removing from the statute books Section 213 - the nightmare of Government employees who lived through the harrowing experience.

“National Women’s Party Bulletin.” National Women’s Party. September - October, 1966, Vol. 1. No. 6. http://fedora.dlib.indiana.edu/fedora/get/iudl:2522378/OVERVIEW.

Questions

Probably one of the most tragic cases ever encountered by the National Woman's Party, was -

Section 213, Married Persons Clause, Economy Act of 1932.

The purpose of this Act was to reduce existing personnel where a husband and wife were both in the service, to create positions for those unemployed. The Act read:

"In any reduction of personnel in any branch of the service of the United States Government or the District of Columbia, married persons (living with husband or wife), employed in the class to be reduced shall be dismissed before any other person employed in such class is dismissed, if such husband or wife is also in the service of the United States or the District of Columbia."

Perhaps this would have been a solution of the unemployment problem, except, it should be remembered, these were the Depression Years… "I was there" and a witness to the tragedy which befell some of my friends and I suffered for them. I knew young women who had come to Washington and entered the Government service because it was necessary to help their families who were victims of the Depression. I knew young women receiving $100 a month who sent from $25 to $50 a month to their families and lived on the balance. Some were married when they came to Washington with husbands in the Combat services, others married later, but in so many cases both husbands and wives had to contribute to the support of their families "back home."

The Government Workers Council of the National Woman's Party, headed by Mrs. Edwina Avery, a lawyer and a Government worker, were given an office on the ground floor of our Page Eight Headquarters, from which they conducted a long and strenuous campaign to repeal Section 213… Before the end of the fight many other women's organizations had joined us in protest against Section 213.

Finally, after a vigorous struggle lasting five years, a Bill to repeal Section 213 was passed by the House on June 5, 1937, by a vote of 206 and 128; was unanimously passed by the Senate on July 23, 1937 and signed by President Franklin Roosevelt on July 26, 1937 - thus removing from the statute books Section 213 - the nightmare of Government employees who lived through the harrowing experience.

“National Women’s Party Bulletin.” National Women’s Party. September - October, 1966, Vol. 1. No. 6. http://fedora.dlib.indiana.edu/fedora/get/iudl:2522378/OVERVIEW.

Questions

- What was Section 213 of the Economy Act and whom did it discriminate against?

- How does this source reflect enduring gendered expectations in the era?

Remedial Herstory Editors. "18. WOMEN AND THE GREAT DEPRESSION." The Remedial Herstory Project. November 20, 2022. www.remedialherstory.com.

Primary AUTHOR: |

Dr. Alicia Gutierrez-Romine

|

Primary ReviewerS: |

Dr. Barbara Tischler

|

Consulting TeamKelsie Brook Eckert, Project Director

Coordinator of Social Studies Education at Plymouth State University Dr. Barbara Tischler, Consultant Professor of History Hunter College and Columbia University Dr. Alicia Gutierrez-Romine, Consultant Assistant Professor of History at La Sierra University Jacqui Nelson, Consultant Teaching Lecturer of Military History at Plymouth State University Dr. Deanna Beachley Professor of History and Women's Studies at College of Southern Nevada |

EditorsAlice Stanley

ReviewersColonial

Dr. Margaret Huettl Hannah Dutton Dr. John Krueckeberg 19th Century Dr. Rebecca Noel Michelle Stonis, MA Annabelle L. Blevins Pifer, MA Cony Marquez, PhD Candidate 20th Century Dr. Tanya Roth Dr. Jessica Frazier Mary Bezbatchenko, MA Dr. Alicia Gutierrez-Romine Matthew Cerjak |

|

Macy offers a rare and fascinating glimpse into the journey of women's rights through the lens of women in sports during the pivotal decade of the 1920s. With elegant prose, poignant wit, and fascinating primary sources, Macy explores the many hurdles presented to female athletes as they stormed the field, stepped up to bat, and won the right to compete in sports.

|

By the 1920s, women were on the verge of something huge. Jazz, racy fashions, eyebrowraising new attitudes about art and sex—all of this pointed to a sleek, modern world, one that could shake off the grimness of the Great War and stride into the future in one deft, stylized gesture.

|

The passage of the 18th Amendment (banning the sale of alcohol) and the 19th (women's suffrage) in the same year is no coincidence. These two Constitutional Amendments enabled women to redefine themselves and their place in society in a way historians have neglected to explore. Liberated Spirits describes how the fight both to pass and later to repeal Prohibition was driven by women, as exemplified by two remarkable women in particular.

|

|

In this first study of Black radicalism in midwestern cities before the civil rights movement, Melissa Ford connects the activism of Black women who championed justice during the Great Depression to those involved in the Ferguson Uprising and the Black Lives Matter movement.

|

Daughters of the Great Depression is a reinterpretation of more than fifty well-known and rediscovered works of Depression-era fiction that illuminate one of the decade's central conflicts: whether to include women in the hard-pressed workforce or relegate them to a literal or figurative home sphere.

|

Making Choices, Making Do is a comparative study of Black and white working-class women’s survival strategies during the Great Depression. Based on analysis of employment histories and Depression-era interviews of 1,340 women in Chicago, Cleveland, Philadelphia, and South Bend and letters from domestic workers.

|

|

In 1923, fifteen-year-old Hattie Shepherd, swept up by the tides of the Great Migration, flees Georgia and heads north. Full of hope, she settles in Philadelphia to build a better life. Instead she marries a man who will bring her nothing but disappointment, and watches helplessly as her firstborn twins are lost to an illness that a few pennies could have prevented. Hattie gives birth to nine more children, whom she raises with grit, mettle, and not an ounce of the tenderness they crave. She vows to prepare them to meet a world that will not be kind. Their lives, captured here in twelve luminous threads, tell the story of a mother’s monumental courage—and a nation's tumultuous journey.

|

In 1935, Dottie Krasinsky is the epitome of the modern girl. A bookkeeper in Midtown Manhattan, Dottie steals kisses from her steady beau, meets her girlfriends for drinks, and eyes the latest fashions. Yet at heart, she is a dutiful daughter, living with her Yiddish-speaking parents on the Lower East Side. So when, after a single careless night, she finds herself in a family way by a charismatic but unsuitable man, she is desperate: unwed, unsure, and running out of options. After the birth of five children—and twenty years as a housewife—Dottie’s immigrant mother, Rose, is itching to return to the social activism she embraced as a young woman. With strikes and breadlines at home and National Socialism rising in Europe, there is much more important work to do than cooking and cleaning. So when she realizes that she, too, is pregnant, she struggles to reconcile her longings with her faith.

|

Harlem, 1926. Young Black women like Louise Lloyd are ending up dead. Following a harrowing kidnapping ordeal when she was in her teens, Louise is doing everything she can to maintain a normal life. She’s succeeding, too. She spends her days working at Maggie’s Café and her nights at the Zodiac, Harlem’s hottest speakeasy. Louise’s friends, especially her girlfriend, Rosa Maria Moreno, might say she’s running from her past and the notoriety that still stalks her, but don’t tell her that.

|

How to teach with Films:

Remember, teachers want the student to be the historian. What do historians do when they watch films?

- Before they watch, ask students to research the director and producers. These are the source of the information. How will their background and experience likely bias this film?

- Also, ask students to consider the context the film was created in. The film may be about history, but it was made recently. What was going on the year the film was made that could bias the film? In particular, how do you think the gains of feminism will impact the portrayal of the female characters?

- As they watch, ask students to research the historical accuracy of the film. What do online sources say about what the film gets right or wrong?

- Afterward, ask students to describe how the female characters were portrayed and what lessons they got from the film.

- Then, ask students to evaluate this film as a learning tool. Was it helpful to better understand this topic? Did the historical inaccuracies make it unhelpful? Make it clear any informed opinion is valid.

|

Places In The Heart

In central Texas in the 1930s, a widow with two small children tries to save her small 40-acre farm with the help of a blind boarder and an itinerant black handyman. |

|

Bibliography

“Biography: Mary McLeod Bethune.” n.d. National Women’s History Museum. https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/mary-mcleod-bethune.

Collins, Gail, America's Women: Four Hundred Years of Dolls, Drudges, Helpmates, and Heroines. New York, William Morrow, 2003.

DuBois, Ellen Carol, 1947-. Through Women's Eyes : an American History with Documents. Boston :Bedford/St. Martin's, 2005.Indians Editors. “NATIVE AMERICAN WOMEN.” Indians. N.D. http://indians.org/articles/Native-american-women.html.

“" LIFE IN THE THIRTIES " 1930s DOCUMENTARY FILM GREAT DEPRESSION, NEW DEAL, DUST BOWL, FDR 91964 : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive.” 2020. Internet Archive. November 11, 2020. https://archive.org/details/91964-life-in-the-thirties-vwr.

“MOMA | Dorothea Lange. Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California. 1936.” n.d. https://www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning/dorothea-lange-migrant-mother-nipomo-california-1936/.

“Norman Cousins, ‘Will Women Lose Their Jobs?’ (1939).” In Voices of Freedom: A Documentary History, 177-178. New York: Norton 2011.

“Reel America ‘Let’s Go America!’ - 1936 : CSPAN2 : July 24, 2021 10:51am-11:03am EDT : Free Borrow & Streaming : Internet Archive.” 2021. Internet Archive. July 24, 2021. https://archive.org/details/CSPAN2_20210724_145100_Reel_America_Lets_Go_America_-_1936/start/480/end/540.

“Reel America ‘My Trip Abroad by Eleanor Roosevelt’ - 1950 : CSPAN3 : March 29, 2021 11:41am-11:54am EDT : Free Borrow & Streaming : Internet Archive.” 2021. Internet Archive. March 29, 2021. https://archive.org/details/CSPAN3_20210329_154100_Reel_America_My_Trip_Abroad_by_Eleanor_Roosevelt_-_1950/start/60/end/120.

“Should Women Earn Pin Money,” US Press, April 1, 1930.

“Surviving the Dust Bowl: The Works Progress Administration,” PBS, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/surviving-the-dust-bowl-works-progress-administration-wpa/.

Ware, Susan. American Women’s History: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

Collins, Gail, America's Women: Four Hundred Years of Dolls, Drudges, Helpmates, and Heroines. New York, William Morrow, 2003.

DuBois, Ellen Carol, 1947-. Through Women's Eyes : an American History with Documents. Boston :Bedford/St. Martin's, 2005.Indians Editors. “NATIVE AMERICAN WOMEN.” Indians. N.D. http://indians.org/articles/Native-american-women.html.

“" LIFE IN THE THIRTIES " 1930s DOCUMENTARY FILM GREAT DEPRESSION, NEW DEAL, DUST BOWL, FDR 91964 : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive.” 2020. Internet Archive. November 11, 2020. https://archive.org/details/91964-life-in-the-thirties-vwr.

“MOMA | Dorothea Lange. Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California. 1936.” n.d. https://www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning/dorothea-lange-migrant-mother-nipomo-california-1936/.

“Norman Cousins, ‘Will Women Lose Their Jobs?’ (1939).” In Voices of Freedom: A Documentary History, 177-178. New York: Norton 2011.

“Reel America ‘Let’s Go America!’ - 1936 : CSPAN2 : July 24, 2021 10:51am-11:03am EDT : Free Borrow & Streaming : Internet Archive.” 2021. Internet Archive. July 24, 2021. https://archive.org/details/CSPAN2_20210724_145100_Reel_America_Lets_Go_America_-_1936/start/480/end/540.

“Reel America ‘My Trip Abroad by Eleanor Roosevelt’ - 1950 : CSPAN3 : March 29, 2021 11:41am-11:54am EDT : Free Borrow & Streaming : Internet Archive.” 2021. Internet Archive. March 29, 2021. https://archive.org/details/CSPAN3_20210329_154100_Reel_America_My_Trip_Abroad_by_Eleanor_Roosevelt_-_1950/start/60/end/120.

“Should Women Earn Pin Money,” US Press, April 1, 1930.

“Surviving the Dust Bowl: The Works Progress Administration,” PBS, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/surviving-the-dust-bowl-works-progress-administration-wpa/.

Ware, Susan. American Women’s History: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.