19. 1450-1600 Women and the Reformation

|

The Reformation was a time of great change in Europe for both men and women. While men were at the forefront of change, many women also held positions of power and were influential in the changes taking place during this period. While some women were well-respected, respect was difficult to earn and maintain. Women were often persecuted for speaking out. Needless to say, it was not an easy time to be a woman.

|

Audience at Martin Luther's Sermon, Wikimedia Commons

Audience at Martin Luther's Sermon, Wikimedia Commons

In 1429, a country girl of no notable background led the French armies toward the end of the One-Hundred Years War. She believed and convinced others that God compelled her to liberate France from the English. Armies rallied behind her. Eventually she was captured and given the option to recant; she did not. IN 1431, she was burned at the stake, not for leading armies against the English, but for treason and for dressing in men’s clothing. Her name was Joan of Arc, and her story symbolizes the way women facilitated great change, only to be beaten back.

Nearly a century later, in 1517,, the Protestant Reformation began in Europe, attempting to reform what they saw as the corrupt Roman Catholic Church. The result was a new branch of Christianity called Protestantism, a name used to describe many religious groups that separated in “protest” from Rome. The movement resulted in wars, persecution of converts, and major shifts in political power.

Martin Luther was a German monk and Professor of Theology at the University of Wittenberg who posted his 95 Theses, complaints against the church, on the door of a church in Germany. Women were deeply affected by this movement. Women were wives of reformers, writers, protectors of the persecuted, and queens active in religious politics. The Reformation was arguably the most significant shift for women’s status because it finally opened doors, however reluctantly to more widespread education for women.

Education

Martin Luther was no champion of women’s rights. He echoed all the misogyny that church leaders had said before him. He wrote, women “are chiefly created to bear children and be the pleasure, joy, and solace of their husbands.” Noting women’s broad hips, he said, “to the end that they should remain at home, sit still, keep house, and bear and bring up children.”

However, Luther’s philosophy was based on the revolutionary idea that the salvation of every human soul relied on their ability to read the Bible. He thus believed in the full education of boys and girls. Luther wrote, “Were there neither soul, heaven, nor hell, it would still be necessary to have schools here below. The world has need of educated men and women, to the end that they may govern the country properly, and that the women may properly bring up their children, care for their domestics, and direct the affairs of their households.”

Luther certainly locked women in the domestic sphere, but he was adamant that their educations were necessary for establishing a new social order for trade, commerce, and urbanization. At least for the west, this trajectory of this change would plateau at times, but women’s access to literacy was here to stay.

Female Reformers

Women were needed to realize the aims of the Reformation. Male reformers like Luther directed their energy to the theology and politics of the Reformation while female reformers worked to establish a ‘Protestant culture’ throughout Europe. This included Bible instruction in homes and charity work. The Protestant churches struggled to balance their need for female support with their inherent distrust of women being too involved in church life. Women were encouraged, but with caution.

During the Reformation, many women left convents after reading the works of Luther and John Calvin, founder of the Calvinist movement. Leaving the security of convent life, these women sought refuge with reformers across the continent. Ursula of Münsterberg was one of them. The granddaughter of a King, her story was well documented and gives us a glimpse into the lives of women–those who left the convent and those who stayed.

More records survive about the royal and noblewomen of the Reformation. Their lives paint a detailed picture of the persecution women faced when they defied male authority to support the Reformation. These were women who used their unique positions of power to support the Reformation, often in isolation. Despite the limitations placed on them by their gender, the role of the Pastor’s wife became a position of prestige in Protestant communities.

Nearly a century later, in 1517,, the Protestant Reformation began in Europe, attempting to reform what they saw as the corrupt Roman Catholic Church. The result was a new branch of Christianity called Protestantism, a name used to describe many religious groups that separated in “protest” from Rome. The movement resulted in wars, persecution of converts, and major shifts in political power.

Martin Luther was a German monk and Professor of Theology at the University of Wittenberg who posted his 95 Theses, complaints against the church, on the door of a church in Germany. Women were deeply affected by this movement. Women were wives of reformers, writers, protectors of the persecuted, and queens active in religious politics. The Reformation was arguably the most significant shift for women’s status because it finally opened doors, however reluctantly to more widespread education for women.

Education

Martin Luther was no champion of women’s rights. He echoed all the misogyny that church leaders had said before him. He wrote, women “are chiefly created to bear children and be the pleasure, joy, and solace of their husbands.” Noting women’s broad hips, he said, “to the end that they should remain at home, sit still, keep house, and bear and bring up children.”

However, Luther’s philosophy was based on the revolutionary idea that the salvation of every human soul relied on their ability to read the Bible. He thus believed in the full education of boys and girls. Luther wrote, “Were there neither soul, heaven, nor hell, it would still be necessary to have schools here below. The world has need of educated men and women, to the end that they may govern the country properly, and that the women may properly bring up their children, care for their domestics, and direct the affairs of their households.”

Luther certainly locked women in the domestic sphere, but he was adamant that their educations were necessary for establishing a new social order for trade, commerce, and urbanization. At least for the west, this trajectory of this change would plateau at times, but women’s access to literacy was here to stay.

Female Reformers

Women were needed to realize the aims of the Reformation. Male reformers like Luther directed their energy to the theology and politics of the Reformation while female reformers worked to establish a ‘Protestant culture’ throughout Europe. This included Bible instruction in homes and charity work. The Protestant churches struggled to balance their need for female support with their inherent distrust of women being too involved in church life. Women were encouraged, but with caution.

During the Reformation, many women left convents after reading the works of Luther and John Calvin, founder of the Calvinist movement. Leaving the security of convent life, these women sought refuge with reformers across the continent. Ursula of Münsterberg was one of them. The granddaughter of a King, her story was well documented and gives us a glimpse into the lives of women–those who left the convent and those who stayed.

More records survive about the royal and noblewomen of the Reformation. Their lives paint a detailed picture of the persecution women faced when they defied male authority to support the Reformation. These were women who used their unique positions of power to support the Reformation, often in isolation. Despite the limitations placed on them by their gender, the role of the Pastor’s wife became a position of prestige in Protestant communities.

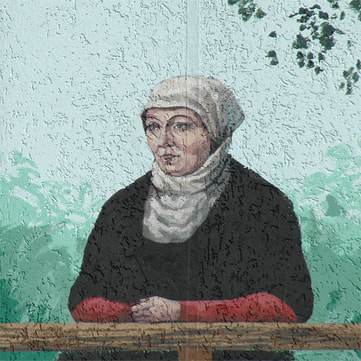

Katharina Zell, Public Domain

Katharina Zell, Public Domain

Katharina Schütz Zell

Women were involved in the Reformation through their marriages and relationships with men in the movement. Katharina Schutz Zell’s education allowed her to take up her pen and record a theological justification of her actions when faced with criticism.

In 1523, Katharina married Matthias Zell, another prominent reformer who had been excommunicated from the Catholic church because of his marriage. A year later, Katharina published her first work, “Apologia,” a defense of clerical marriage in general and hers in particular. Katharina understood the political undercurrents of the time, and she knew her biblical texts and her calling as a clerical wife. For a wife to publish a theological defense of the marriage was a risky move. Had the marriage failed or been shrouded in scandal, this would have provided perfect evidence of the ‘evil’ clerical marriage created. Her work demonstrated that a woman could use her gifts, combine them with theological and biblical knowledge, and create a place for her in the movement.

Strasbourg, Germany, was a ‘free city’ that provided refuge to supporters of Luther who fled from surrounding villages and towns. Whenever refugees arrived, Katharina filled the parsonage with 80 beds and fed 60 every day for 3 weeks. Katharina petitioned the local council to intervene, recruiting others to care for refugees, and writing letters of encouragement to wives left behind when their husbands were forced to flee. In 1525, the male leadership in the church grew tired of her petitions stating, “she is a trifle imperious.”

Despite Zell being twenty years Katharina’s senior, people saw Matthias as being “led by Katharina’s apron strings.” One wrote that, “Matthias lagged because Katherine dragged”. Her marriage of equals, a partnership, was presented as a woman controlling her husband to the detriment of the church.

Luther became a friend of Katharina’s. In the correspondence between them, one would expect to find Luther administering pastoral care and advice to Katharina in accordance with his teaching on gender roles. Instead, we see advice being exchanged between the two equally. Luther wrote to Katharina, not her husband, and asked her to “entreat both your lord and other friends, that (if it please God) peace and union may be preserved.”

Katharina continued her charity work after her husband’s death until the city council insisted she leave her home and allow her husband’s successor to move in. Katharina’s social position was more restricted, so she changed her focus and created a hymn book.

Like most female Reformers, Katharina was criticized by her male colleagues, not so much because of what she did, but because she was a woman. In her lifetime, Katharina witnessed and was victim of a shift in the new Protestant churches and saw herself being pushed out of the sect she helped to establish. She wrote, “In my younger days, I was so dear to the fine old learned men and the architects of the church of Christ.”

Women were involved in the Reformation through their marriages and relationships with men in the movement. Katharina Schutz Zell’s education allowed her to take up her pen and record a theological justification of her actions when faced with criticism.

In 1523, Katharina married Matthias Zell, another prominent reformer who had been excommunicated from the Catholic church because of his marriage. A year later, Katharina published her first work, “Apologia,” a defense of clerical marriage in general and hers in particular. Katharina understood the political undercurrents of the time, and she knew her biblical texts and her calling as a clerical wife. For a wife to publish a theological defense of the marriage was a risky move. Had the marriage failed or been shrouded in scandal, this would have provided perfect evidence of the ‘evil’ clerical marriage created. Her work demonstrated that a woman could use her gifts, combine them with theological and biblical knowledge, and create a place for her in the movement.

Strasbourg, Germany, was a ‘free city’ that provided refuge to supporters of Luther who fled from surrounding villages and towns. Whenever refugees arrived, Katharina filled the parsonage with 80 beds and fed 60 every day for 3 weeks. Katharina petitioned the local council to intervene, recruiting others to care for refugees, and writing letters of encouragement to wives left behind when their husbands were forced to flee. In 1525, the male leadership in the church grew tired of her petitions stating, “she is a trifle imperious.”

Despite Zell being twenty years Katharina’s senior, people saw Matthias as being “led by Katharina’s apron strings.” One wrote that, “Matthias lagged because Katherine dragged”. Her marriage of equals, a partnership, was presented as a woman controlling her husband to the detriment of the church.

Luther became a friend of Katharina’s. In the correspondence between them, one would expect to find Luther administering pastoral care and advice to Katharina in accordance with his teaching on gender roles. Instead, we see advice being exchanged between the two equally. Luther wrote to Katharina, not her husband, and asked her to “entreat both your lord and other friends, that (if it please God) peace and union may be preserved.”

Katharina continued her charity work after her husband’s death until the city council insisted she leave her home and allow her husband’s successor to move in. Katharina’s social position was more restricted, so she changed her focus and created a hymn book.

Like most female Reformers, Katharina was criticized by her male colleagues, not so much because of what she did, but because she was a woman. In her lifetime, Katharina witnessed and was victim of a shift in the new Protestant churches and saw herself being pushed out of the sect she helped to establish. She wrote, “In my younger days, I was so dear to the fine old learned men and the architects of the church of Christ.”

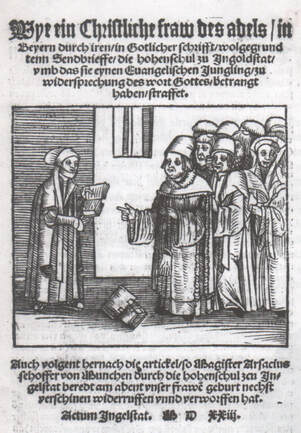

pamphlet of Argula von Grumbach, wikimedia commons

pamphlet of Argula von Grumbach, wikimedia commons

Argula von Grumbach

Argula von Grumbach was a noble woman and avid reader of Protestant literature. When a man at the university in Bavaria where she lived was arrested and facing execution for promoting his Protestant views, Argula wrote to the university, defending him and the teachings of Luther.. She wrote, “I send you not a woman’s ranting, but the Word of God. I write as a member of the Church of Christ against which the gates of hell shall not prevail, as they will against the Church of Rome. God give us grace that we may all be blessed. Amen.”

Argula received no formal reply to her letters. Was this because she was a reformer? Or because she was a woman? The contemporary inscription at the bottom of one of her letters in Munich answers these questions: “Born a Lutheran whore and gate of hell. 13 December, 1523”

A local professor at the university preached against “daughters of Eve” like Arugula before insulting her directly calling her a: “female desperado”, “arrogant devil”, “heretical bitch”, and “shameless whore.”

When her opponents wrote an insulting poem about her, Arugula responded in kind with 240 lines of rhyming couplets which directly referred to her right to speak on religious affairs despite her gender. She wrote, “He tells me to mind my knitting. To obey my man indeed is fitting, but if he drives me from God’s word…Home and child we must forsake, when God’s honor is at stake.”

Arugula continued to plead the Protestant case, both in the public domain and through her writing, for the next seven years. While her letter-writing career spanned only a year, an estimated 29,000 copies of her pamphlets were in circulation in 1524, meaning she was, “the most famous female Lutheran and bestselling pamphleteer.” In later life, living in her inherited estates in Bohemia, she continued her reform efforts, inviting converts to her home and bothering the authorities.

Argula von Grumbach was a noble woman and avid reader of Protestant literature. When a man at the university in Bavaria where she lived was arrested and facing execution for promoting his Protestant views, Argula wrote to the university, defending him and the teachings of Luther.. She wrote, “I send you not a woman’s ranting, but the Word of God. I write as a member of the Church of Christ against which the gates of hell shall not prevail, as they will against the Church of Rome. God give us grace that we may all be blessed. Amen.”

Argula received no formal reply to her letters. Was this because she was a reformer? Or because she was a woman? The contemporary inscription at the bottom of one of her letters in Munich answers these questions: “Born a Lutheran whore and gate of hell. 13 December, 1523”

A local professor at the university preached against “daughters of Eve” like Arugula before insulting her directly calling her a: “female desperado”, “arrogant devil”, “heretical bitch”, and “shameless whore.”

When her opponents wrote an insulting poem about her, Arugula responded in kind with 240 lines of rhyming couplets which directly referred to her right to speak on religious affairs despite her gender. She wrote, “He tells me to mind my knitting. To obey my man indeed is fitting, but if he drives me from God’s word…Home and child we must forsake, when God’s honor is at stake.”

Arugula continued to plead the Protestant case, both in the public domain and through her writing, for the next seven years. While her letter-writing career spanned only a year, an estimated 29,000 copies of her pamphlets were in circulation in 1524, meaning she was, “the most famous female Lutheran and bestselling pamphleteer.” In later life, living in her inherited estates in Bohemia, she continued her reform efforts, inviting converts to her home and bothering the authorities.

Marie Dentière

Marie Dentière, also used her education and position to write. As was common for girls of her social status, Marie entered the convent when she was around 13 years old At the age of 26, Marie was elected Abbess of her Augustinian nunnery but soon fled for her safety.

As the Reformation swept Europe, Marie fled to Strasbourg, and later Geneva, when the victory of Protestant armies declared it a Protestant city. It was then that Marie began her writing career and advocacy for women. She wrote, “If God has given graces to some good women, revealing to them something holy and good through His Holy Scripture, should they, for the sake of the defamers of the truth, refrain from writing down, speaking, or declaring it to each other? Ah! It would be too impudent to hide the talent which God has given to us, we who ought to have the grace to persevere to the end. Amen!”

In Geneva 1,500 copies were printed under a pseudonym, but pastors in Geneva seized the remaining copies and arrested the publisher. The publisher was given a fine, and he and Marie’s husband had to appear before the council and argue that the books were not heretical. The books were never released, and the council quickly passed legislation banning the publication of books which they had not approved. Marie’s husband remarked that this reaction was only because the council had been so, “wounded, piqued and dishonored by a woman.”

The suppression of Marie’s writing generated conversation among Reformers. In 1539, the Council of Bern asked Béat Comte whether they should allow the work to be translated. After reading the book, Comte replied, saying that, while he could find nothing in it contrary to Scripture, because it was written by a woman and should be suppressed. Marie’s voice was silenced, not by Catholic authorities, but by her fellow Reformers.

Marie posed an important question in a letter to Queen Marguerite of Navarre: “Do we have two Gospels, one for men and the other for women?”

Marie Dentière, also used her education and position to write. As was common for girls of her social status, Marie entered the convent when she was around 13 years old At the age of 26, Marie was elected Abbess of her Augustinian nunnery but soon fled for her safety.

As the Reformation swept Europe, Marie fled to Strasbourg, and later Geneva, when the victory of Protestant armies declared it a Protestant city. It was then that Marie began her writing career and advocacy for women. She wrote, “If God has given graces to some good women, revealing to them something holy and good through His Holy Scripture, should they, for the sake of the defamers of the truth, refrain from writing down, speaking, or declaring it to each other? Ah! It would be too impudent to hide the talent which God has given to us, we who ought to have the grace to persevere to the end. Amen!”

In Geneva 1,500 copies were printed under a pseudonym, but pastors in Geneva seized the remaining copies and arrested the publisher. The publisher was given a fine, and he and Marie’s husband had to appear before the council and argue that the books were not heretical. The books were never released, and the council quickly passed legislation banning the publication of books which they had not approved. Marie’s husband remarked that this reaction was only because the council had been so, “wounded, piqued and dishonored by a woman.”

The suppression of Marie’s writing generated conversation among Reformers. In 1539, the Council of Bern asked Béat Comte whether they should allow the work to be translated. After reading the book, Comte replied, saying that, while he could find nothing in it contrary to Scripture, because it was written by a woman and should be suppressed. Marie’s voice was silenced, not by Catholic authorities, but by her fellow Reformers.

Marie posed an important question in a letter to Queen Marguerite of Navarre: “Do we have two Gospels, one for men and the other for women?”

Marguerite of Navarre, Wikimedia Commons

Marguerite of Navarre, Wikimedia Commons

Queens of Navarre

In France, the Protestant Reformation looked more like a civil conflict, and women in the nobility were at the center of it. Marguerite was royalty in France and came to Protestantism gradually. Her brother, Francis, was the King of France who had a deep affection for his sister, which was the only thing protecting her as Marguerite wrote and published extensively.

The situation in France intensified, and by 1525, most of Marguerite’s friends were in exile or hiding. It was then, two years after the death of her first husband, that Marguerite married Henri d’Albert, King of Navarre, with whom she had one daughter, Jeanna d’Albert.

The religious and political situation in France remained tense until 17th October 1534, when a group of zealous reformers took to the streets of Paris, putting up anti-Catholic posters in what was called “The Affair of the Placards.” The signs openly questioned the King’s authority and Francis was forced into action. The ringleaders were arrested and burnt in the Place Maubert, while others fled.

In France, the Protestant Reformation looked more like a civil conflict, and women in the nobility were at the center of it. Marguerite was royalty in France and came to Protestantism gradually. Her brother, Francis, was the King of France who had a deep affection for his sister, which was the only thing protecting her as Marguerite wrote and published extensively.

The situation in France intensified, and by 1525, most of Marguerite’s friends were in exile or hiding. It was then, two years after the death of her first husband, that Marguerite married Henri d’Albert, King of Navarre, with whom she had one daughter, Jeanna d’Albert.

The religious and political situation in France remained tense until 17th October 1534, when a group of zealous reformers took to the streets of Paris, putting up anti-Catholic posters in what was called “The Affair of the Placards.” The signs openly questioned the King’s authority and Francis was forced into action. The ringleaders were arrested and burnt in the Place Maubert, while others fled.

portrait of Jeanne of Navarre, wikimedia commons

portrait of Jeanne of Navarre, wikimedia commons

Risking sibling rivalry, Marguerite opened her home to Protestant refugees. With all of these religious fugitives living in Navarre, Marguerite encouraged religious growth within her domain. Seeing herself as a spiritual mother to her people, Marguerite set about writing manuals on doctrine and worship, the likes never seen in the church before.

But this came at a cost. Calvin, despite benefitting from Marguerite’s dedication to the Reformation, remained critical of her behavior. He continued to argue that she was too generous to the wrong people and not generous enough to the right ones. Calvin summarized her usefulness to the Reformation by stating that: “we cannot place on her too great an alliance.”

When Marguerite and her husband died, their daughter Jeanne ascended to their political post. Jeanne was no stranger to defying the patriarchy, having successfully annulled an undesirable marriage at age twelve by kicking and screaming her way up the aisle, thoroughly documenting her lack of consent to the match and refusing to consummate the marriage. She remarried at age nineteen, presumably for love.

One of her first actions was to convene the Protestant ministers from the Calvinist sect. She became the most powerful female Protestant in Europe and an enemy of the Pope and the rest of her French (and very Catholic) family. In 1562, Catherine de Medici, now Queen regent of France, imposed an edict to try and keep the peace between the Protestant and Catholic factions at court.

Tension mounted between Jeanne and her Catholic husband when she failed to stop the invasion of her husband’s land by a Protestant army of 400 men. Seeing this as a purposeful failure, he put out an order for her arrest with the plan of sending her to a convent. But Jeanne made it to safety. Her husband died in November 1562, leaving her as sole regent of Navarre until her son Henry came of age.

But this came at a cost. Calvin, despite benefitting from Marguerite’s dedication to the Reformation, remained critical of her behavior. He continued to argue that she was too generous to the wrong people and not generous enough to the right ones. Calvin summarized her usefulness to the Reformation by stating that: “we cannot place on her too great an alliance.”

When Marguerite and her husband died, their daughter Jeanne ascended to their political post. Jeanne was no stranger to defying the patriarchy, having successfully annulled an undesirable marriage at age twelve by kicking and screaming her way up the aisle, thoroughly documenting her lack of consent to the match and refusing to consummate the marriage. She remarried at age nineteen, presumably for love.

One of her first actions was to convene the Protestant ministers from the Calvinist sect. She became the most powerful female Protestant in Europe and an enemy of the Pope and the rest of her French (and very Catholic) family. In 1562, Catherine de Medici, now Queen regent of France, imposed an edict to try and keep the peace between the Protestant and Catholic factions at court.

Tension mounted between Jeanne and her Catholic husband when she failed to stop the invasion of her husband’s land by a Protestant army of 400 men. Seeing this as a purposeful failure, he put out an order for her arrest with the plan of sending her to a convent. But Jeanne made it to safety. Her husband died in November 1562, leaving her as sole regent of Navarre until her son Henry came of age.

illustration from Malleus Maleficarum, alamy

illustration from Malleus Maleficarum, alamy

With Navarre stuck between Catholic Spain and Catholic France, things were not easy for Jeanne. The Pope threatened to excommunicate and confiscate her lands. Jeanne replied by stating that she did not recognize his authority. Meanwhile, Philip of Spain made plans to either marry her into a Catholic family or kidnap her and allow France and Spain to invade her lands. None of the threats made against her materialized, but, as a young widow and mother with no close alliances, the emotional strain must have been awful In her memoirs, Jeanne remembered how she expected daily to be assassinated.

In 1568, the Spanish Dutch War began. This time, retreat was not an option for Jeanne. She and her son Henry moved to the city of La Rochelle, where they could be better protected. They established a Protestant headquarters. Jeanne sent manifestos to anyone she thought would help. She oversaw the safety of refugees arriving in La Rochelle, setting up a seminary there for them. She assumed control of the city’s fortifications, even going to the battles to assess the damage and rally the forces. Later, she sold her jewelry to finance the fighting.

Jeanne continued to negotiate for peace. In August 1570, when the Catholic forces ran out of money, the Peace of Saint-Germain-en-Laye was achieved. Without hiding her distaste for the French court and her distrust of Catherine de Medici, Jeanne reluctantly agreed to the marriage of her son and King Charles IX’s sister Marguerite. The wedding that inspired violence in the form of the Saint Bartholomew’s Day Massacre.

Jeanne passed away two months before the wedding, in 1572 at the age of 43. The Pope’s envoy to the French court described her passing as, “an event happy beyond my highest hopes…her death, a great work of God’s own hand, has put an end to this wicked woman, who daily perpetrated the greatest possible evil.”

Despite Jeanne’s efforts to secure a Protestant future through her son, Henry later converted to Catholicism to solidify his political situation. His sister, however, ruled on his mother’s lands for thirty years, continuing to provide a relatively safe haven for Protestants.

Witches

People in many societies worldwide, through many eras, have attributed misfortunes like disease, poor harvests, bad weather, or just bad luck, to malicious magic. People of many societies have also, likewise, turned to spells, charms, amulets, and the like, to try to secure advantages for themselves, to tell the future, or to try to ward off harm. Occasionally, a person in the community might actually get blamed for misfortune, as a “witch” or the local culture’s equivalent. This is common.

What is not common is the mass witch hunt; large-scale, sustained efforts to persecute people on charges of malicious magic. In Europe, however, such hunts became a recurring feature of life between about 1400 and 1700 AD. Somewhere between 50,000 and 100,000 people were killed across Europe over these three centuries. About 80-85% of them were women.

In 1568, the Spanish Dutch War began. This time, retreat was not an option for Jeanne. She and her son Henry moved to the city of La Rochelle, where they could be better protected. They established a Protestant headquarters. Jeanne sent manifestos to anyone she thought would help. She oversaw the safety of refugees arriving in La Rochelle, setting up a seminary there for them. She assumed control of the city’s fortifications, even going to the battles to assess the damage and rally the forces. Later, she sold her jewelry to finance the fighting.

Jeanne continued to negotiate for peace. In August 1570, when the Catholic forces ran out of money, the Peace of Saint-Germain-en-Laye was achieved. Without hiding her distaste for the French court and her distrust of Catherine de Medici, Jeanne reluctantly agreed to the marriage of her son and King Charles IX’s sister Marguerite. The wedding that inspired violence in the form of the Saint Bartholomew’s Day Massacre.

Jeanne passed away two months before the wedding, in 1572 at the age of 43. The Pope’s envoy to the French court described her passing as, “an event happy beyond my highest hopes…her death, a great work of God’s own hand, has put an end to this wicked woman, who daily perpetrated the greatest possible evil.”

Despite Jeanne’s efforts to secure a Protestant future through her son, Henry later converted to Catholicism to solidify his political situation. His sister, however, ruled on his mother’s lands for thirty years, continuing to provide a relatively safe haven for Protestants.

Witches

People in many societies worldwide, through many eras, have attributed misfortunes like disease, poor harvests, bad weather, or just bad luck, to malicious magic. People of many societies have also, likewise, turned to spells, charms, amulets, and the like, to try to secure advantages for themselves, to tell the future, or to try to ward off harm. Occasionally, a person in the community might actually get blamed for misfortune, as a “witch” or the local culture’s equivalent. This is common.

What is not common is the mass witch hunt; large-scale, sustained efforts to persecute people on charges of malicious magic. In Europe, however, such hunts became a recurring feature of life between about 1400 and 1700 AD. Somewhere between 50,000 and 100,000 people were killed across Europe over these three centuries. About 80-85% of them were women.

example of a "witch" being burned at the stake, history extra

example of a "witch" being burned at the stake, history extra

In previous centuries, medieval Christian authorities held that magic was a trick of the Devil, but that the Devil could not control physical reality, because that was God’s role. Magic was therefore a temptation and a delusion but not a mortal threat. Churchmen would preach against it and require penances for it, but they would not execute people for it. In fact, in the 8th century, when he conquered the pagan Saxons, Charlemagne decreed the death penalty for anyone who burned a woman on an accusation of witchcraft, because he saw that as a pagan thing to do. Christians were supposed to know better.

Around 1300 AD, this began to change. Christian authorities in both church and state strove for a more purified, holy society, but the failures of this ideal led to increased paranoia in some. Pessimism, bred by increased famine and plague and destructive wars among kings, added to the anxiety. Maybe God was letting the Devil have more of a role in the world than they thought! Various rumors and fears that had originally been separate, such as anti-Semitic legends and the outrageous accusations against the Knights Templar, wove together into a new myth, the “Witches’ Sabbath.”

According to this myth, “witches” traveled by night to gather at a kind of feast presided over by the Devil. They cursed Christ and swore loyalty to Satan, committed various blasphemies and sexual offenses, killed babies to eat or to boil down into ointments and potions, and promised to wreak as much havoc as they could in Christian society, spreading disease, destroying crops, and so on. Witches were thus imagined to form a kind of dangerous anti-Christian cult or conspiracy.

Witches could be either male or female (gendering the word “witch” feminine and contrasting it to other words like “warlock” or “sorcerer” is a modern usage, not used at the time). As the trials arose, however, women were far more likely to be accused and executed, usually by burning but sometimes by other means (in England, for instance, execution was usually by hanging). Scholars have debated exactly why this was the case. Some have interpreted the trials as “femicide,” an overt misogynistic project to destroy women. However, this interpretation is unlikely; many accusers were themselves women, some witch trials actually targeted more men than women (such as in Normandy and Russia), and while some of the demonology treatises that theorized witchcraft singled out women as especially sinister, others did not. It's also hard to say why this particular era would have initiated a "femicide" when past centuries had been no less misogynistic. Anecdotes from the time suggest stereotypes of witches as marginal, difficult, or assertive women, but actual trial records don't provide solid support that these stereotypes were really driving accusations.

One text that did single out women was the Malleus Maleficarum, or “Hammer of Witches,” published in 1486. In it, drawing on the ancient philosopher Aristotle’s ideas and giving them a Christian slant, Heinrich Kramer argued that because women were “softer” than men, they were more susceptible to spiritual influences. If those influences were holy, then women could become greater saints than men. But if those influences were demonic, they became horrible witches, worse than any man. However, the theology faculty at the University of Cologne condemned Kramer’s book and later witchcraft treatises rarely repeated the claim.

An alternative explanation to the “femicide” hypothesis would be that in the patriarchal structures of European society, women were less likely to have the social prestige, political influence, education, or material resources, to be able to defend themselves. As a result, they were more likely to find themselves accused, and having been accused, less likely to escape the death penalty.

The distribution of witchcraft trials was not uniform across Europe through this period, but varied in time and place. Interestingly, they actually slowed down between 1520 and 1570, the decades of the Protestant Reformation. This is probably because, in the midst of struggles between Protestants and Catholics, social conflict was more likely to result in people accusing each other of belonging to the other religion, rather than of being witches. Once the Reformation settled into a permanent establishment, witch trials picked up again (among both Catholics and Protestants), and were at their peak between 1570 and 1630, before gradually fading out by the early 1700s. People in these later generations still believed in witchcraft, and feared it. But as modern states formed more centralized legal systems, with stricter standards of evidence and more opportunity for oversight and appeals, judges were less likely to accept accusations that a particular defendant in front of them actually was a witch.

Geographically, about half of all victims of witch hunts were in Germany alone. Other countries had far less. England, for instance, had far fewer trials, especially in proportion to its population, than Scotland. In fact, across this entire period, England only had one true “witch hunt,” with perhaps 300 persons accused, as opposed to scattered trials of individuals (and that one was during England’s Civil War in the 1640s, when central authority had broken down. A man named Matthew Hopkins claimed that Parliament had appointed him “Witch Finder General” - it hadn’t - and traveled around the country spreading accusations before being shut down). Again, it’s probably because kingdoms with strong central governments tended to limit the spread of accusations, as legal procedures were more strictly enforced. Places like Germany and Scotland lacked such strong central courts, so local authorities were on their own to deal with accusations, which could thus spin out of control.

Around 1300 AD, this began to change. Christian authorities in both church and state strove for a more purified, holy society, but the failures of this ideal led to increased paranoia in some. Pessimism, bred by increased famine and plague and destructive wars among kings, added to the anxiety. Maybe God was letting the Devil have more of a role in the world than they thought! Various rumors and fears that had originally been separate, such as anti-Semitic legends and the outrageous accusations against the Knights Templar, wove together into a new myth, the “Witches’ Sabbath.”

According to this myth, “witches” traveled by night to gather at a kind of feast presided over by the Devil. They cursed Christ and swore loyalty to Satan, committed various blasphemies and sexual offenses, killed babies to eat or to boil down into ointments and potions, and promised to wreak as much havoc as they could in Christian society, spreading disease, destroying crops, and so on. Witches were thus imagined to form a kind of dangerous anti-Christian cult or conspiracy.

Witches could be either male or female (gendering the word “witch” feminine and contrasting it to other words like “warlock” or “sorcerer” is a modern usage, not used at the time). As the trials arose, however, women were far more likely to be accused and executed, usually by burning but sometimes by other means (in England, for instance, execution was usually by hanging). Scholars have debated exactly why this was the case. Some have interpreted the trials as “femicide,” an overt misogynistic project to destroy women. However, this interpretation is unlikely; many accusers were themselves women, some witch trials actually targeted more men than women (such as in Normandy and Russia), and while some of the demonology treatises that theorized witchcraft singled out women as especially sinister, others did not. It's also hard to say why this particular era would have initiated a "femicide" when past centuries had been no less misogynistic. Anecdotes from the time suggest stereotypes of witches as marginal, difficult, or assertive women, but actual trial records don't provide solid support that these stereotypes were really driving accusations.

One text that did single out women was the Malleus Maleficarum, or “Hammer of Witches,” published in 1486. In it, drawing on the ancient philosopher Aristotle’s ideas and giving them a Christian slant, Heinrich Kramer argued that because women were “softer” than men, they were more susceptible to spiritual influences. If those influences were holy, then women could become greater saints than men. But if those influences were demonic, they became horrible witches, worse than any man. However, the theology faculty at the University of Cologne condemned Kramer’s book and later witchcraft treatises rarely repeated the claim.

An alternative explanation to the “femicide” hypothesis would be that in the patriarchal structures of European society, women were less likely to have the social prestige, political influence, education, or material resources, to be able to defend themselves. As a result, they were more likely to find themselves accused, and having been accused, less likely to escape the death penalty.

The distribution of witchcraft trials was not uniform across Europe through this period, but varied in time and place. Interestingly, they actually slowed down between 1520 and 1570, the decades of the Protestant Reformation. This is probably because, in the midst of struggles between Protestants and Catholics, social conflict was more likely to result in people accusing each other of belonging to the other religion, rather than of being witches. Once the Reformation settled into a permanent establishment, witch trials picked up again (among both Catholics and Protestants), and were at their peak between 1570 and 1630, before gradually fading out by the early 1700s. People in these later generations still believed in witchcraft, and feared it. But as modern states formed more centralized legal systems, with stricter standards of evidence and more opportunity for oversight and appeals, judges were less likely to accept accusations that a particular defendant in front of them actually was a witch.

Geographically, about half of all victims of witch hunts were in Germany alone. Other countries had far less. England, for instance, had far fewer trials, especially in proportion to its population, than Scotland. In fact, across this entire period, England only had one true “witch hunt,” with perhaps 300 persons accused, as opposed to scattered trials of individuals (and that one was during England’s Civil War in the 1640s, when central authority had broken down. A man named Matthew Hopkins claimed that Parliament had appointed him “Witch Finder General” - it hadn’t - and traveled around the country spreading accusations before being shut down). Again, it’s probably because kingdoms with strong central governments tended to limit the spread of accusations, as legal procedures were more strictly enforced. Places like Germany and Scotland lacked such strong central courts, so local authorities were on their own to deal with accusations, which could thus spin out of control.

Anne Boleyn, Wikimedia Commons

Anne Boleyn, Wikimedia Commons

Queen Elizabeth I

The Reformation in England presented quite differently than on the continent. The Catholic King Henry VIII had long been married to Catherine of Aragon, daughter of Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand,. They had many pregnancies, but only one daughter, Mary, survived.

Known for his many affairs at court, Henry VIII fell in love with Anne Boleyn, one of his wife's ladies. His passion is evident in letters he wrote– 17 of which survive, "If you... give yourself up, heart, body and soul to me... I will take you for my only mistress, rejecting from thought and affection all others save yourself, to serve only you."

But she boldly said no. "Your wife I cannot be, both in respect of mine own unworthiness, and also because you have a queen already. Your mistress I will not be." Their liaison dragged on, and eventually after over twenty years of marriage, Henry asked the Pope to annul his marriage on the grounds that Catherine had been previously married to his older brother who died just six months after they married. Catherine insisted to her dying day that the marriage to his brother was never consummated and the Pope rejected Henry’s request. In response, Henry broke from Rome. He declared himself the head of the new Church of England; divorced his wife and sent her into isolation. He delegitimize his daughter and heir, and banned Mary from seeing her mother. Henry soon thereafter married his lover, Anne Boleyn.

Although Anne had been raised Catholic, she advocated for reform. She read banned anti-clerical books and supported reformists. Anne's reformist leanings alienated the people of England. The Spanish were furious at the insult to their Princess. An ambassador insulted Anne by calling her "more Lutheran than Luther himself," though this was likely hyperbole. The public hated Anne not just because they viewed her as an adulteress, but because they considered her a heretic.

The Reformation in England presented quite differently than on the continent. The Catholic King Henry VIII had long been married to Catherine of Aragon, daughter of Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand,. They had many pregnancies, but only one daughter, Mary, survived.

Known for his many affairs at court, Henry VIII fell in love with Anne Boleyn, one of his wife's ladies. His passion is evident in letters he wrote– 17 of which survive, "If you... give yourself up, heart, body and soul to me... I will take you for my only mistress, rejecting from thought and affection all others save yourself, to serve only you."

But she boldly said no. "Your wife I cannot be, both in respect of mine own unworthiness, and also because you have a queen already. Your mistress I will not be." Their liaison dragged on, and eventually after over twenty years of marriage, Henry asked the Pope to annul his marriage on the grounds that Catherine had been previously married to his older brother who died just six months after they married. Catherine insisted to her dying day that the marriage to his brother was never consummated and the Pope rejected Henry’s request. In response, Henry broke from Rome. He declared himself the head of the new Church of England; divorced his wife and sent her into isolation. He delegitimize his daughter and heir, and banned Mary from seeing her mother. Henry soon thereafter married his lover, Anne Boleyn.

Although Anne had been raised Catholic, she advocated for reform. She read banned anti-clerical books and supported reformists. Anne's reformist leanings alienated the people of England. The Spanish were furious at the insult to their Princess. An ambassador insulted Anne by calling her "more Lutheran than Luther himself," though this was likely hyperbole. The public hated Anne not just because they viewed her as an adulteress, but because they considered her a heretic.

Elizabeth I, Wikimedia Commons

Elizabeth I, Wikimedia Commons

Desperate to secure a male heir, Henry was increasingly frustrated when Anne gave birth to a daughter, Elizabeth. Future pregnancies resulted in miscarriages. He began an affair with Jane Seymour. Anne was furious and Henry was tired of her. He accused her of adultery and incest with her brother. She and her brother were beheaded.

Later, Jane died in childbirth to his only legitimate son. He married again, only for ithe union to end in divorce. His next marriage ended in beheading. When he finally died, leaving his sixth wife alive and well, his weak son ascended to the throne, only to die as a teen. Mary, Henry’s daughter from his first marriage, seized the throne, returning the Catholics to power in what has inaccurately been called a reign of terror earning her the derogatory nickname, Bloody Mary. When Mary died, likely of ovarian cancer, her half sister Elizabeth claimed the throne as Elizabeth I. Elizabeth killed more Catholics than her sister did Protestants, but Elizabeth ruled longer and got to write the history. When she became queen, writers of the period would extol her mother Anne for her Protestant views and credited her with "banishing the beast of Rome with all his beggarly baggage."

Elizabeth’s throne was never secure. Catholics on the continent were constantly looking to usurp the Protestant Queen. Her cousin, Mary Queen of Scots, tried to assassinate her with support fromCatholics in France. But it was Catholic Spain that held the real hatred for Elizabeth, as it was her mother who had replaced their princess, Catherine.

Later, Jane died in childbirth to his only legitimate son. He married again, only for ithe union to end in divorce. His next marriage ended in beheading. When he finally died, leaving his sixth wife alive and well, his weak son ascended to the throne, only to die as a teen. Mary, Henry’s daughter from his first marriage, seized the throne, returning the Catholics to power in what has inaccurately been called a reign of terror earning her the derogatory nickname, Bloody Mary. When Mary died, likely of ovarian cancer, her half sister Elizabeth claimed the throne as Elizabeth I. Elizabeth killed more Catholics than her sister did Protestants, but Elizabeth ruled longer and got to write the history. When she became queen, writers of the period would extol her mother Anne for her Protestant views and credited her with "banishing the beast of Rome with all his beggarly baggage."

Elizabeth’s throne was never secure. Catholics on the continent were constantly looking to usurp the Protestant Queen. Her cousin, Mary Queen of Scots, tried to assassinate her with support fromCatholics in France. But it was Catholic Spain that held the real hatred for Elizabeth, as it was her mother who had replaced their princess, Catherine.

All this came to a head in the late 1580s, when King Philip II of Spain planned the conquest of England. The Pope, Sixtus V, gave his blessing, hoping to secure England as a Catholic kingdom again. At the time, the Spanish had the largest Armada of ships in Europe and had already sailed them across the Atlantic. A giant Spanish invasion fleet was built, but the English attacked early by lighting some of their own ships on fire and sending them afloat into the Spanish fleet. In the confusion, the Spanish sailed right into English guns. Others fled to the open seas where it appeared to the faithful that God himself intervened, as a storm sank the majority of the remaining fleet.

Elizabeth’s defeat of the Spanish Armada was the beginning of the decline of the Spanish Empire and a pivotal victory for Protestantism. This victory for the woman who claimed to have “the heart of a man” was also seen as divine proof of her position as queen.

End of the Reformation

As Protestantism became more established on the continent, the need for female support diminished and tighter restrictions were placed on women’s activities. When it came to women in the ministry and church life, the male reformers found themselves caught between what they thought theologically and what they wanted practically. For male reformers, like their Catholic counterparts, it was theologically unsound and even heretical to have women actively involved in the church. What these men thought about women was in contrast to their need for female support. This confusion was never adequately resolved. Protestant churches established by the Reformation were left with a culture of female involvement coexisting with a theology of female exclusion.

Conclusion

The Protestant Reformation took different shapes in different parts of Europe. In France, it resulted in the persecution of the Huguenots, in Germany wars, in England political drama. Everywhere women were integral to the story.

The result was not only the rise of Protestantism, but the Catholic Counter-Reformation, both largely acknowledged the importance of educating the masses–including women. Women’s access to education, the Bible, and the roles they played in the movement set the stage for the modern era.

By the end of this era, so much remained in question. How much would access to education improve women’s status? How would future women intellectuals be received? And how long would the status sought by reformers take to be realized?

Elizabeth’s defeat of the Spanish Armada was the beginning of the decline of the Spanish Empire and a pivotal victory for Protestantism. This victory for the woman who claimed to have “the heart of a man” was also seen as divine proof of her position as queen.

End of the Reformation

As Protestantism became more established on the continent, the need for female support diminished and tighter restrictions were placed on women’s activities. When it came to women in the ministry and church life, the male reformers found themselves caught between what they thought theologically and what they wanted practically. For male reformers, like their Catholic counterparts, it was theologically unsound and even heretical to have women actively involved in the church. What these men thought about women was in contrast to their need for female support. This confusion was never adequately resolved. Protestant churches established by the Reformation were left with a culture of female involvement coexisting with a theology of female exclusion.

Conclusion

The Protestant Reformation took different shapes in different parts of Europe. In France, it resulted in the persecution of the Huguenots, in Germany wars, in England political drama. Everywhere women were integral to the story.

The result was not only the rise of Protestantism, but the Catholic Counter-Reformation, both largely acknowledged the importance of educating the masses–including women. Women’s access to education, the Bible, and the roles they played in the movement set the stage for the modern era.

By the end of this era, so much remained in question. How much would access to education improve women’s status? How would future women intellectuals be received? And how long would the status sought by reformers take to be realized?

Draw your own conclusions

|

Learn how to teach with inquiry.

Many of these lesson plans were sponsored in part by the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources Eastern Region Program, coordinated by Waynesburg University, the History and Social Studies Education Faculty at Plymouth State University, and the Patrons of the Remedial Herstory Project. |

Lesson Plans from Other Organizations

- This website, Women in World History has primary source based lesson plans on women's history in a whole range of topics. Some are free while others have a cost.

- The Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media has produced recommendations for teaching women's history with primary sources and provided a collection of sources for world history. Check them out!

- The Stanford History Education Group has a number of lesson plans about women in World History.

Joan of Arc: Hear the Words of God and the Maid!

This is a letter to the King of England from Joan of Arc. In the letter, Joan refers to herself as “the maid.”

King of England, render account to the King of Heaven of your royal blood. Return the keys of all the good cities which you have seized, to the Maid. She is sent by God to reclaim the royal blood, and is fully prepared to make peace, if you will give her satisfaction; that is, you must render justice, and pay back all that you have taken.

King of England, if you do not do these things, I am the commander of the military; and in whatever place I shall find your men in France, I will make them flee the country, whether they wish to or not; and if they will not obey, the Maid will have them all killed. She comes sent by the King of Heaven, body for body, to take you out of France, and the Maid promises and certifies to you that if you do not leave France she and her troops will raise a mighty outcry as has not been heard in France in a thousand years. And believe that the King of Heaven has sent her so much power that you will not be able to harm her or her brave army.

To you, archers, noble companions in arms, and all people who are before Orleans, I say to you in God's name, go home to your own country; if you do not do so, beware of the Maid, and of the damages you will suffer. Do not attempt to remain, for you have no rights in France from God, the King of Heaven, and the Son of the Virgin Mary. It is Charles, the rightful heir, to whom God has given France, who will shortly enter Paris in a grand company. If you do not believe the news written of God and the Maid, then in whatever place we may find you, we will soon see who has the better right, God or you.

Duke of Bedford, who call yourself regent of France for the King of England, the Maid asks you not to make her destroy you. If you do not render her satisfaction, she and the French will perform the greatest feat ever done in the name of Christianity.

Translated by Belle Tuten from M. Vallet de Vireville, ed. Chronique de la Pucelle, ou Chronique de Cousinot. Paris: Adolphe Delahaye, 1859, pp. 281-283.

Questions:

King of England, render account to the King of Heaven of your royal blood. Return the keys of all the good cities which you have seized, to the Maid. She is sent by God to reclaim the royal blood, and is fully prepared to make peace, if you will give her satisfaction; that is, you must render justice, and pay back all that you have taken.

King of England, if you do not do these things, I am the commander of the military; and in whatever place I shall find your men in France, I will make them flee the country, whether they wish to or not; and if they will not obey, the Maid will have them all killed. She comes sent by the King of Heaven, body for body, to take you out of France, and the Maid promises and certifies to you that if you do not leave France she and her troops will raise a mighty outcry as has not been heard in France in a thousand years. And believe that the King of Heaven has sent her so much power that you will not be able to harm her or her brave army.

To you, archers, noble companions in arms, and all people who are before Orleans, I say to you in God's name, go home to your own country; if you do not do so, beware of the Maid, and of the damages you will suffer. Do not attempt to remain, for you have no rights in France from God, the King of Heaven, and the Son of the Virgin Mary. It is Charles, the rightful heir, to whom God has given France, who will shortly enter Paris in a grand company. If you do not believe the news written of God and the Maid, then in whatever place we may find you, we will soon see who has the better right, God or you.

Duke of Bedford, who call yourself regent of France for the King of England, the Maid asks you not to make her destroy you. If you do not render her satisfaction, she and the French will perform the greatest feat ever done in the name of Christianity.

Translated by Belle Tuten from M. Vallet de Vireville, ed. Chronique de la Pucelle, ou Chronique de Cousinot. Paris: Adolphe Delahaye, 1859, pp. 281-283.

Questions:

- Based on this source, was. Joan of Arc a heretic?

Catherine de Pizan: The Song of Joan of Arc

A poem by Catherine de Pizan, France's first woman of letters.

And you, Charles, now the king of France, The seventh king of that great name, Who earlier suffered such mischance; You thought the future held more shame. But by God's grace, now look how Joan Has raised your fame on high, oh see! Your enemies before you bow--

This is a welcome novelty!--

Most quickly worked; one would have thought, That such a deed could not be done,

That all your efforts were for nought,

That France was gone; now it is won. Although you took tremendous harm,

You have your country back in tow,

Won back by wise Joan's mighty arm. Thanks be to God, it happened so!

Translated from the French text in Christine de Pisan, Ditié de Jeanne d'Arc, ed. Angus J. Kennedy and Kenneth Varty (Oxford: Society for the Study of Medieval Languages and Literature, 1977), trans. L. Shopkow.

Questions:

And you, Charles, now the king of France, The seventh king of that great name, Who earlier suffered such mischance; You thought the future held more shame. But by God's grace, now look how Joan Has raised your fame on high, oh see! Your enemies before you bow--

This is a welcome novelty!--

Most quickly worked; one would have thought, That such a deed could not be done,

That all your efforts were for nought,

That France was gone; now it is won. Although you took tremendous harm,

You have your country back in tow,

Won back by wise Joan's mighty arm. Thanks be to God, it happened so!

Translated from the French text in Christine de Pisan, Ditié de Jeanne d'Arc, ed. Angus J. Kennedy and Kenneth Varty (Oxford: Society for the Study of Medieval Languages and Literature, 1977), trans. L. Shopkow.

Questions:

- Was Joan of Arc a heretic?

Clergyman: The First Trial Of Joan Of Arc

“We, the judges, say and decree: that you, Joan, have deeply sinned in pretending untruthfully that your revelations and apparitions are of God; in seducing others; in believing lightly and rashly; in making superstitious divinations; in blaspheming God and the Saints; in prevaricating as to the law, Holy Scripture, and the Canonical sanctions; in despising God in His Sacraments; in fomenting seditions and revolts; in apostatizing; in encouraging the crime of heresy; in erring on numerous points in the Catholic Faith.

But because that, after being many times charitably admonished and long waited for, you have at last, with the help of God, returned into the bosom of the Church, your Holy Mother, with contrite heart, and have openly revoked your errors; because, having solemnly and publicly cast these far from you, you have abjured them by the words of your own mouth, together with the heresy with which you were charged: We declare you set free by these presents, according to the form appointed by Ecclesiastical sanction, from the bonds of excommunications which held you enchained, charging you to return to the Church with a true heart and sincere faith, and to observe what has been already enjoined you and what shall yet be enjoined you by us.

But because you have sinned rashly against God and Holy Church, We condemn you, finally, definitely and for salutary penance, saving Our grace and moderation, to perpetual imprisonment, with the bread of sorrow and the water of affliction, in order that you may bewail your faults, and that you may no more commit [acts] which you shall have to bewail hereafter.”

T. Douglas Murray, Jeanne d'Arc (New York: McClure, Phillips & Co, 1902).

Questions:

But because that, after being many times charitably admonished and long waited for, you have at last, with the help of God, returned into the bosom of the Church, your Holy Mother, with contrite heart, and have openly revoked your errors; because, having solemnly and publicly cast these far from you, you have abjured them by the words of your own mouth, together with the heresy with which you were charged: We declare you set free by these presents, according to the form appointed by Ecclesiastical sanction, from the bonds of excommunications which held you enchained, charging you to return to the Church with a true heart and sincere faith, and to observe what has been already enjoined you and what shall yet be enjoined you by us.

But because you have sinned rashly against God and Holy Church, We condemn you, finally, definitely and for salutary penance, saving Our grace and moderation, to perpetual imprisonment, with the bread of sorrow and the water of affliction, in order that you may bewail your faults, and that you may no more commit [acts] which you shall have to bewail hereafter.”

T. Douglas Murray, Jeanne d'Arc (New York: McClure, Phillips & Co, 1902).

Questions:

- How did the Church of England view Joan of Arc?

- Were they justified in their ruling?

Joan Of Arc: A Letter Written During Her Trial

"For this cause, I, Joan, commonly called the Maid, a miserable sinner, after that I had recognized the snares of error in the which I was held, and [after] that, by the grace of God, I had returned to our Holy Mother Church, in order that it may be seen that, not feigningly but with a good heart and good will, I have returned thereto; I confess that I have most grievously sinned, in pretending untruthfully to have had revelations and apparitions from God... in wearing a dissolute habit, misshapen and immodest and against the propriety of nature, and hair clipped 'en ronde' in the style of a man, against all the modesty of the feminine sex; also, in bearing arms in great presumption; in cruelly desiring the effusion of human blood; in saying that all these things I did by the command of God... I confess also that I have been schismatic and in many ways have erred from the Faith... (Signed thus): Jehanne †."

T. Douglas Murray, Jeanne d'Arc (New York: McClure, Phillips & Co, 1902).

Questions:

T. Douglas Murray, Jeanne d'Arc (New York: McClure, Phillips & Co, 1902).

Questions:

- What is the tone?

- Does Joan of Arc believe she has sinned?

Clergyman: Final Trial Of Joan Of Arc

Afterwards, We, the Bishop and Vicar aforesaid, having regard to all that has gone before, in which it is shown that this woman had never truly abandoned her errors... diabolical obstinacy...

WE DECREE THAT YOU ART A RELAPSED HERETIC... we denounce thee as a rotten member, and that you may not vitiate others, as cast out from the unity of the Church... Here follows the Sentence of Excommunication. . . that you have been on the subject of thy pretended divine revelations and apparitions lying, seducing, and blasphemy towards God and the Saints... WE DECLARE THEE OF RIGHT EXCOMMUNICATE AND HERETIC... We do abandon thee to the secular authority, as a member of Satan.

T. Douglas Murray, Jeanne d'Arc (New York: McClure, Phillips & Co, 1902.

Questions:

WE DECREE THAT YOU ART A RELAPSED HERETIC... we denounce thee as a rotten member, and that you may not vitiate others, as cast out from the unity of the Church... Here follows the Sentence of Excommunication. . . that you have been on the subject of thy pretended divine revelations and apparitions lying, seducing, and blasphemy towards God and the Saints... WE DECLARE THEE OF RIGHT EXCOMMUNICATE AND HERETIC... We do abandon thee to the secular authority, as a member of Satan.

T. Douglas Murray, Jeanne d'Arc (New York: McClure, Phillips & Co, 1902.

Questions:

- Was Joan of Arc decreed a heretic?

Brother Seguin de Seguin: Testimony From the Rehabilitation Trials

Church officials worried that the original charges of heresy were politically, not religiously motivated. With the support of Joan’s surviving family, Bishops were open to revisit the original trials. The transcripts of the original hearing at Poitiers had been lost so clergy who had been present came to testify.

From the testimony of Brother Seguin de Seguin, Professor of Theology at Poitiers:

"Do you believe in God ?" I asked her. " In truth, more than yourself!" she answered. "But God wills that you should not be believed unless there appear some sign to prove that you ought to be believed; and we shall not advise the King to trust in you, and to risk an army on your simple statement." "In God's Name! " she replied, "I am not come to Poitiers to show signs: but send me to Orleans, where I shall show you the signs by which I am sent: and she added: "Send me men in such numbers as may seem good, and I will go to Orleans."

And then she foretold to us - to me and to all the others who were with me - these four things which should happen, and which did afterwards come to pass: first, that the English would be destroyed, the siege of Orleans raised, and the town delivered from the English; secondly, that the King would be crowned at Reims; thirdly, that Paris would be restored to his dominion; and fourthly, that the Duke d'Orleans should be brought back from England. And I who speak, I have in truth seen these four things accomplished.

We reported all this to the Council of the King; and we were of opinion that, considering the extreme necessity and the great peril of the town, the King might make use of her help and send her to Orleans. Besides this, we inquired into her life and morals; and found that she was a good Christian, living as a Catholic, never idle. In order that her manner of living might be better known, women were placed with her who were commissioned to report to the Council her actions and ways.

“Trial at Poiters.” Saint Joan of Arc's Trials. Accessed November 4, 2022. http://www.stjoan- center.com/Trials/index.html#nullification.

Questions:

From the testimony of Brother Seguin de Seguin, Professor of Theology at Poitiers:

"Do you believe in God ?" I asked her. " In truth, more than yourself!" she answered. "But God wills that you should not be believed unless there appear some sign to prove that you ought to be believed; and we shall not advise the King to trust in you, and to risk an army on your simple statement." "In God's Name! " she replied, "I am not come to Poitiers to show signs: but send me to Orleans, where I shall show you the signs by which I am sent: and she added: "Send me men in such numbers as may seem good, and I will go to Orleans."

And then she foretold to us - to me and to all the others who were with me - these four things which should happen, and which did afterwards come to pass: first, that the English would be destroyed, the siege of Orleans raised, and the town delivered from the English; secondly, that the King would be crowned at Reims; thirdly, that Paris would be restored to his dominion; and fourthly, that the Duke d'Orleans should be brought back from England. And I who speak, I have in truth seen these four things accomplished.

We reported all this to the Council of the King; and we were of opinion that, considering the extreme necessity and the great peril of the town, the King might make use of her help and send her to Orleans. Besides this, we inquired into her life and morals; and found that she was a good Christian, living as a Catholic, never idle. In order that her manner of living might be better known, women were placed with her who were commissioned to report to the Council her actions and ways.

“Trial at Poiters.” Saint Joan of Arc's Trials. Accessed November 4, 2022. http://www.stjoan- center.com/Trials/index.html#nullification.

Questions:

- Was Joan of Arc a heretic?

Martin Luther: Table Talk

These are conversations Luther had had with students, colleagues, and friends.

CXCV .

The history of the resurrection of Christ, teaching that which human wit and wisdom of itself cannot believe, that “Christ is risen from the dead,” was declared to the weaker and sillier creatures, women, and such as were perplexed and troubled. Silly, indeed, before God, and before the world: first, before God, in that they “sought the living among the dead;” second, before the world, for they forgot the “great stone which lay at the mouth of the sepulchre,” and prepared spices to anoint Christ, which was all in vain. But spiritually is hereby signified this: if the “great stone,” namely, the law and human traditions, whereby the consciences are bound and snared, be not rolled away from the heart, then we cannot find Christ, or believe that he is risen from the dead. For through him we are delivered from the power of sin and death, Rom. viii., so that the hand-writing of the conscience can hurt us no more.

CCCXCIX.

Luther’s wife said to him: Sir, I heard your cousin, John Palmer, preach this afternoon in the parish church, whom I understood better than Dr. Palmer, though the Doctor is held to be a very excellent preacher. Luther answered: John Palmer preaches as ye women use to talk; for what comes into your minds, ye speak. A preacher ought to remain by the text, and deliver that which he has before him, to the end people may well understand it. But a preacher that will speak every thing that comes in his mind, is like a maid that goes to market, and meeting another maid, makes a stand, and they hold together a goods-market.

“Table Talk with Luther.” Work info: Table Talk - Christian Classics Ethereal Library. Accessed November 8, 2022. https://www.ccel.org/ccel/luther/tabletalk.

Questions:

CXCV .

The history of the resurrection of Christ, teaching that which human wit and wisdom of itself cannot believe, that “Christ is risen from the dead,” was declared to the weaker and sillier creatures, women, and such as were perplexed and troubled. Silly, indeed, before God, and before the world: first, before God, in that they “sought the living among the dead;” second, before the world, for they forgot the “great stone which lay at the mouth of the sepulchre,” and prepared spices to anoint Christ, which was all in vain. But spiritually is hereby signified this: if the “great stone,” namely, the law and human traditions, whereby the consciences are bound and snared, be not rolled away from the heart, then we cannot find Christ, or believe that he is risen from the dead. For through him we are delivered from the power of sin and death, Rom. viii., so that the hand-writing of the conscience can hurt us no more.

CCCXCIX.

Luther’s wife said to him: Sir, I heard your cousin, John Palmer, preach this afternoon in the parish church, whom I understood better than Dr. Palmer, though the Doctor is held to be a very excellent preacher. Luther answered: John Palmer preaches as ye women use to talk; for what comes into your minds, ye speak. A preacher ought to remain by the text, and deliver that which he has before him, to the end people may well understand it. But a preacher that will speak every thing that comes in his mind, is like a maid that goes to market, and meeting another maid, makes a stand, and they hold together a goods-market.

“Table Talk with Luther.” Work info: Table Talk - Christian Classics Ethereal Library. Accessed November 8, 2022. https://www.ccel.org/ccel/luther/tabletalk.

Questions:

- How does Luther describe women in CXCV? Is that what he believes or what he thinks the church believes?

- How does Luther describe women in CCCXCIX?

Martin Luther: Table Talk II

This is a pair of conversations between Luther and another, most likely a colleague or peer.

CCCCLXXXVIII.

The state of celibacy is great hypocrisy and wickedness. Augustine, though he lived in a good and acceptable time, was deceived through the exaltation of nuns. And although he gave them leave to marry, yet he said they did wrong to marry, and sinned against God. Afterwards, when the time of wrath and blindness came, and the truth was hunted away, and lying got the upper hand, the generation of poor women was condemned, under the color of great holiness, but which, in truth, was mere hypocrisy. Christ with one sentence confutes all their arguments: God created them male and female.

“Table Talk with Luther.” Work info: Table Talk - Christian Classics Ethereal Library. Accessed November 8, 2022. https://www.ccel.org/ccel/luther/tabletalk.

Questions:

CCCCLXXXVIII.

The state of celibacy is great hypocrisy and wickedness. Augustine, though he lived in a good and acceptable time, was deceived through the exaltation of nuns. And although he gave them leave to marry, yet he said they did wrong to marry, and sinned against God. Afterwards, when the time of wrath and blindness came, and the truth was hunted away, and lying got the upper hand, the generation of poor women was condemned, under the color of great holiness, but which, in truth, was mere hypocrisy. Christ with one sentence confutes all their arguments: God created them male and female.

“Table Talk with Luther.” Work info: Table Talk - Christian Classics Ethereal Library. Accessed November 8, 2022. https://www.ccel.org/ccel/luther/tabletalk.

Questions:

- How does Luther view celibacy?

- Was Luther supportive of nuns?

- Was Martin Luther a sexist?

Jeanne De Jussie: Excerpts From The Short Chronicle

Jeanne De Jussie was a nun living in Geneva at the time of the Reformation. She kept a journal detailing her and her sister's experience as nuns facing persecution from Protestant Reformers.

"For in no way do we wish for any innovation of faith or law, or to abandon the divine office, but are determined to live and die in our holy vocation here in your convent praying to our Lord for the peace and preservation of your noble city"

“The poor sisters all as one took refuge in the church, their heads bowed down to the ground, and they prayed to God with a great many tears and in anguish"