16. Final Push for Woman Suffrage

|

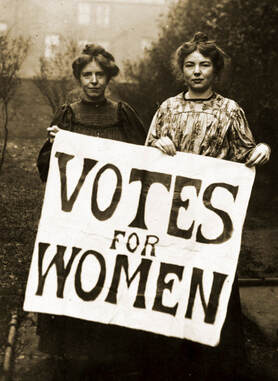

The first wave of suffragists were gone. It was up to a new, educated, and persistent generation of women to earn the right to vote. This final push for women's suffrage saw pageants, parades, marches, boycotts, silent sentinels, hunger strikes, in addition to all the tactics used before. When World War I broke out, women did not back down as they had during the Civil War, escalating the attention to the movement. Women's suffrage eventually passed as a war measure.

|

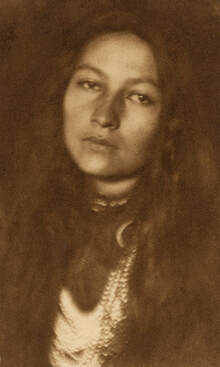

Zitkala Sa, Wikimedia Commons

Zitkala Sa, Wikimedia Commons

As the women’s suffrage movement in the United States entered a new century, most of its original leaders were now gone. Elizabeth caddy Stanton, Susan B Anthony, Lucretia Mott, and the other white women who were instrumental in the founding of the national American women’s suffrage Association were dead. It was up to a new generation of young college educated women to navigate the tricky dynamic of advocating for political reforms without having an official voice in politics. New leaders emerged like Carrie Catt, Ida B Wells Barnett, Alice Paul, and Lucy Burns. Although their advocacy and focus may have varied, these women lead the national movement in its final push to gain women’s suffrage. State to state suffrage leaders emerged and helped advocate for reform on a state level. There are also leaders like Zitkala Sa and Mabel Ping-Hua Lee who advocated for groups that were yet to be even recognized as citizens, like Native Americans and Chinese Americans.

What were these women and their allies after? A democracy that recognized them as full citizens. Named after Susan B. Anthony who first introduced in 1878, the amendment stated simply: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.”

That one sentence took decades of work, sweat, tears, and violence to pass.

What were these women and their allies after? A democracy that recognized them as full citizens. Named after Susan B. Anthony who first introduced in 1878, the amendment stated simply: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.”

That one sentence took decades of work, sweat, tears, and violence to pass.

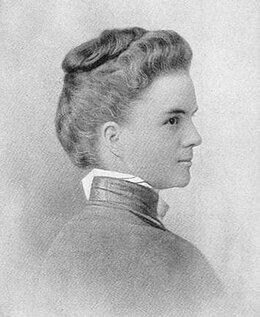

Lucy Stanton

Lucy Stanton

College Degrees:

To discuss women’s suffrage in this period, it would be impossible to ignore the role that educational reforms played in the lives of the new generation of women leading the charge. Young women at the turn of the century were attending college at rates never before seen. These women entered into college classrooms where no women have done before. Most often they were not greeted with open arms. In fact they were greeted with hostility. They were often seen as taking a seat from a young man, “who would actually use his degree.“ Young female college students were ridiculed, jeered, bullied, and sexually harassed. That harassment was not only from their peers, but also from their professors. In some cases women were allowed to attend classes, but not earn degrees. Oberlin college, which was one of the first to admit women, was still incredibly discriminatory towards them. For example, on Mondays female students were released early from class so that they could do the laundry for the male students. In other places, their male professors refused to teach them. Or in one instance, as women sat for an exam, their male peers rioted in protest.

Colleges for women were treated like a dangerous experiment: what might these women possibly learn? Colleges that were designed for men who are modeled on the idea of an “academic village.“ Boys would cross from their dormitory to the academic buildings where they attended classes. Colleges designed for women however reinforced traditional ideas of modesty. There was no quad for them. Girls attended classes in buildings modeled after seminaries, or religious buildings.

Yet, across every field, women were joining the ranks of those college educated. Higher education for women was relatively new in the United States. Mississippi college became the first institute for higher education to actually grant a degree to women in 1831: Alice Robinson and Catherine Hall. Then in 1839, Wesleyan College opened and exclusively granted bachelors degrees for women. A decade later, Elizabeth Blackwell, who was born in England, became the first woman to earn a medical degree at an American institution. She had received 10 rejection letters from various colleges. One person even told her that if she really wanted a college degree, she should dress like a man. She did not cross-dress, instead writing, "It was to my mind a moral crusade. It must be pursued in the light of day, and with public sanction, in order to accomplish its end." In 1850, Lucy Stanton became the first Black woman to earn a degree in the US, from Oberlin College. Mary Fellows was the first woman to receive a degree from west of the Mississippi River. It wasn’t until 1873, that California declared that girls should have equal access to higher education. It would take years before that same philosophy was applied across the country.

Between 1880 and 1930, 50 years, colleges of higher education went from about 50% being coed to 75%. The Ivy Leagues were some of the last holdouts, with some exception: Cornell began admitting women in 1870. But most opted for having sister colleges, like the Radcliffe to Harvard. Radcliffe contracted with Harvard professors to teach classes to the female students. But others resisted women’s education like it was the plague. Most Ivy League institutions did not give women equal access until the 1960s and 70s under the women’s movement. And even then there was much resistance. One Dartmouth alumni wrote: "For God's sake, for Dartmouth's sake, and for everyone's sake, keep the damned women out,"

At Princeton, outright misogyny ruled the day: “What is all this nonsense about admitting women to Princeton? A good old-fashioned whore-house would be considerably more efficient, and much, much cheaper."

Eventually, pragmatically, the Ivy Leagues, too, began to accept women into their institutions. Unfortunately it wasn’t because they suddenly embraced women’s liberation. It was because male undergraduates were opting to go to coed institutions rather than male-only institutions. In order to stay competitive and get the best male intellectuals in their doors they admitted women as a “perk” for male students.

To discuss women’s suffrage in this period, it would be impossible to ignore the role that educational reforms played in the lives of the new generation of women leading the charge. Young women at the turn of the century were attending college at rates never before seen. These women entered into college classrooms where no women have done before. Most often they were not greeted with open arms. In fact they were greeted with hostility. They were often seen as taking a seat from a young man, “who would actually use his degree.“ Young female college students were ridiculed, jeered, bullied, and sexually harassed. That harassment was not only from their peers, but also from their professors. In some cases women were allowed to attend classes, but not earn degrees. Oberlin college, which was one of the first to admit women, was still incredibly discriminatory towards them. For example, on Mondays female students were released early from class so that they could do the laundry for the male students. In other places, their male professors refused to teach them. Or in one instance, as women sat for an exam, their male peers rioted in protest.

Colleges for women were treated like a dangerous experiment: what might these women possibly learn? Colleges that were designed for men who are modeled on the idea of an “academic village.“ Boys would cross from their dormitory to the academic buildings where they attended classes. Colleges designed for women however reinforced traditional ideas of modesty. There was no quad for them. Girls attended classes in buildings modeled after seminaries, or religious buildings.

Yet, across every field, women were joining the ranks of those college educated. Higher education for women was relatively new in the United States. Mississippi college became the first institute for higher education to actually grant a degree to women in 1831: Alice Robinson and Catherine Hall. Then in 1839, Wesleyan College opened and exclusively granted bachelors degrees for women. A decade later, Elizabeth Blackwell, who was born in England, became the first woman to earn a medical degree at an American institution. She had received 10 rejection letters from various colleges. One person even told her that if she really wanted a college degree, she should dress like a man. She did not cross-dress, instead writing, "It was to my mind a moral crusade. It must be pursued in the light of day, and with public sanction, in order to accomplish its end." In 1850, Lucy Stanton became the first Black woman to earn a degree in the US, from Oberlin College. Mary Fellows was the first woman to receive a degree from west of the Mississippi River. It wasn’t until 1873, that California declared that girls should have equal access to higher education. It would take years before that same philosophy was applied across the country.

Between 1880 and 1930, 50 years, colleges of higher education went from about 50% being coed to 75%. The Ivy Leagues were some of the last holdouts, with some exception: Cornell began admitting women in 1870. But most opted for having sister colleges, like the Radcliffe to Harvard. Radcliffe contracted with Harvard professors to teach classes to the female students. But others resisted women’s education like it was the plague. Most Ivy League institutions did not give women equal access until the 1960s and 70s under the women’s movement. And even then there was much resistance. One Dartmouth alumni wrote: "For God's sake, for Dartmouth's sake, and for everyone's sake, keep the damned women out,"

At Princeton, outright misogyny ruled the day: “What is all this nonsense about admitting women to Princeton? A good old-fashioned whore-house would be considerably more efficient, and much, much cheaper."

Eventually, pragmatically, the Ivy Leagues, too, began to accept women into their institutions. Unfortunately it wasn’t because they suddenly embraced women’s liberation. It was because male undergraduates were opting to go to coed institutions rather than male-only institutions. In order to stay competitive and get the best male intellectuals in their doors they admitted women as a “perk” for male students.

Carrie Chapman Catt, Britannica

Carrie Chapman Catt, Britannica

Doldrums:

But what did all of this education have to do with suffrage? Everything. One of the best anti-suffrage arguments was not granting women the vote would introduce yet another largely uneducated, potentially illiterate, group of people into the voting population. Remember it wasn’t too long ago, and was still within recent memory of most in power that men of color were also granted suffrage. How could women, who don’t work in industry, possibly vote in any informed way on issues of economics or politics? The growing numbers of women graduating with college degrees was proving that narrative false. Women can be informed voters.

Among the first wave of undergraduates with bachelor's degrees was Carrie Chapman Catt who was selected as the president of NAWSA, to succeed Susan B. Anthony. Catt was a formidable choice. She dedicated her entire life to suffrage. Her first husband died shortly after their marriage from typhoid fever, and she married her second husband, who she knew from college at Iowa State. In 1887, after a short career as a legal clerk and teacher, she joined the women’s crusade. George Catt supported his wife. He viewed their gendered roles as this: his job was to provide, hers was to improve the world. They never had kids and after he died, she worked alongside her female housemate and partner, Mary Garret Hay, for the cause of women. Many many years later, when she died, she chose to be buried under a loving inscription next to Hay.

From 1900 to 1904, Catt led NAWSA, but at the end of her tenure, her husband, Susan B Anthony, and her mother all passed away leaving Catt grief stricken. Without her at the helm, NAWSA struggled. Anna Howard Shaw, who held a degree in ministry and a doctoral degree in medicine, took charge. Shaw was a fierce advocate for working class women, but not a champion for all women. She frequently spoke about nativist views, championed white women’s causes, and created a hostile environment for African-Americans within the movement. But while hostile to some, Shaw is a striking example of the importance of suffrage to queer women. After all, queer women often did not have a man providing for them and all the privileges wives had did not necessarily extend to them. Shaw, like many suffragists, lived with a longtime female partner, Lucy Elmina Anthony, the niece of Susan B. Anthony. There was no man to provide for them, so women in these partnerships lived on the often pitiful and discriminatory salaries granted to women.

All over the country they led marches and were successful in getting some states to grant women the right to vote. California gave women the right to vote in 1911 and Tye Leung Schulze made history as the first Chinese-American woman, if not the first Asian woman in the world, to vote in a democratic election. Of the event she said, “I thought long over that. I studied; I read about all your men who wished to be president. I learned about the new laws. I wanted to KNOW what was right, not to act blindly...I think it is right we should all try to learn, not vote blindly, since we have been given this right to say which man we think is the greatest...I think too that we women are more careful than the men. We want to do our whole duty more. I do not think it is just the newness that makes use like that. It is conscience.”

Across the country, women in eastern states battled against long standing traditions and well-established patriarchal norms. Under Shaw’s leadership women’s suffrage stalled out. They’d been going state by state for decades working to get change and in those decades only nine states had granted women the right to vote: 70 years nine states. Something had to give and the women knew it. Perhaps the strategy was wrong? Between women suffragists, great debate broke out. There were the old-school NAWSA women who advocated for the tried and true continued effort in the state to state campaigns. State campaigns were growing and more and more women were joining the movement at the local level. But a young, animated, and educated generation of women were joining the movement.

But what did all of this education have to do with suffrage? Everything. One of the best anti-suffrage arguments was not granting women the vote would introduce yet another largely uneducated, potentially illiterate, group of people into the voting population. Remember it wasn’t too long ago, and was still within recent memory of most in power that men of color were also granted suffrage. How could women, who don’t work in industry, possibly vote in any informed way on issues of economics or politics? The growing numbers of women graduating with college degrees was proving that narrative false. Women can be informed voters.

Among the first wave of undergraduates with bachelor's degrees was Carrie Chapman Catt who was selected as the president of NAWSA, to succeed Susan B. Anthony. Catt was a formidable choice. She dedicated her entire life to suffrage. Her first husband died shortly after their marriage from typhoid fever, and she married her second husband, who she knew from college at Iowa State. In 1887, after a short career as a legal clerk and teacher, she joined the women’s crusade. George Catt supported his wife. He viewed their gendered roles as this: his job was to provide, hers was to improve the world. They never had kids and after he died, she worked alongside her female housemate and partner, Mary Garret Hay, for the cause of women. Many many years later, when she died, she chose to be buried under a loving inscription next to Hay.

From 1900 to 1904, Catt led NAWSA, but at the end of her tenure, her husband, Susan B Anthony, and her mother all passed away leaving Catt grief stricken. Without her at the helm, NAWSA struggled. Anna Howard Shaw, who held a degree in ministry and a doctoral degree in medicine, took charge. Shaw was a fierce advocate for working class women, but not a champion for all women. She frequently spoke about nativist views, championed white women’s causes, and created a hostile environment for African-Americans within the movement. But while hostile to some, Shaw is a striking example of the importance of suffrage to queer women. After all, queer women often did not have a man providing for them and all the privileges wives had did not necessarily extend to them. Shaw, like many suffragists, lived with a longtime female partner, Lucy Elmina Anthony, the niece of Susan B. Anthony. There was no man to provide for them, so women in these partnerships lived on the often pitiful and discriminatory salaries granted to women.

All over the country they led marches and were successful in getting some states to grant women the right to vote. California gave women the right to vote in 1911 and Tye Leung Schulze made history as the first Chinese-American woman, if not the first Asian woman in the world, to vote in a democratic election. Of the event she said, “I thought long over that. I studied; I read about all your men who wished to be president. I learned about the new laws. I wanted to KNOW what was right, not to act blindly...I think it is right we should all try to learn, not vote blindly, since we have been given this right to say which man we think is the greatest...I think too that we women are more careful than the men. We want to do our whole duty more. I do not think it is just the newness that makes use like that. It is conscience.”

Across the country, women in eastern states battled against long standing traditions and well-established patriarchal norms. Under Shaw’s leadership women’s suffrage stalled out. They’d been going state by state for decades working to get change and in those decades only nine states had granted women the right to vote: 70 years nine states. Something had to give and the women knew it. Perhaps the strategy was wrong? Between women suffragists, great debate broke out. There were the old-school NAWSA women who advocated for the tried and true continued effort in the state to state campaigns. State campaigns were growing and more and more women were joining the movement at the local level. But a young, animated, and educated generation of women were joining the movement.

Alice Paul, Library of Congress

Alice Paul, Library of Congress

Paul and Burns:

Two of the most notable women in this group were Lucy Burns and Alice Paul. Both of these women not only had college degrees, but had multiple college degrees. Burns studied at Vassar College and Yale University and later at the University of Berlin in Germany and Oxford College abroad. There, Burns witnessed the militancy of the British suffrage movement.

In 1909 she joined Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst's Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) where she became an expert orator, and was arrested on numerous occasions. She met Alice Paul in a London police station after both were arrested during a suffrage demonstration outside Parliament.

Paul graduated with a degree in biology from Swarthmore College (1905), and earned graduate degrees in sociology at the University of Pennsylvania (M.A., 1907; Ph.D., 1912). Years after suffrage she would also earn two law degrees.

When they came home from England in 1910, Paul and Burns were disheartened at the state of women’s suffrage in the United States. They pressed NAWSA to take harder positions on suffrage and advocate for a federal amendment. The leaders in NAWSA gave Paul control over the Congressional Committee whose job was to press for a Federal Amendment to the constitution, not just a state by state approach. Between 1912 and 1913, Paul and Burns worked to organize the congressional committee and build it into a robust political force.

Baldwin:

Another one of these women was Marie Louise Bottineau Baldwin—a Chippewa. Baldwin had been born on Ojibwe land but was educated in American society and went on to become the first Indigenous woman to graduate from the Washington College of Law in Washington D.C. Despite this, she was an outspoken advocate of Indigenous communities and also a suffragette. In fact, on the day of her graduation from law school, Baldwin was asked by a reporter if she considered herself a suffragette; in response, she laughed and stated: “Did you ever know that the Indian women were among the first suffragists and that they exercised the right of recall?” In chiding the reporter, Baldwin highlights the fact that Indigenous women—especially those from matrilineal communities—often held and exercised political power amongst their peoples. Still, as demonstrated by her track record as a suffragette, Baldwin clearly believed that women more broadly deserved the right to vote.

Two of the most notable women in this group were Lucy Burns and Alice Paul. Both of these women not only had college degrees, but had multiple college degrees. Burns studied at Vassar College and Yale University and later at the University of Berlin in Germany and Oxford College abroad. There, Burns witnessed the militancy of the British suffrage movement.

In 1909 she joined Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst's Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) where she became an expert orator, and was arrested on numerous occasions. She met Alice Paul in a London police station after both were arrested during a suffrage demonstration outside Parliament.

Paul graduated with a degree in biology from Swarthmore College (1905), and earned graduate degrees in sociology at the University of Pennsylvania (M.A., 1907; Ph.D., 1912). Years after suffrage she would also earn two law degrees.

When they came home from England in 1910, Paul and Burns were disheartened at the state of women’s suffrage in the United States. They pressed NAWSA to take harder positions on suffrage and advocate for a federal amendment. The leaders in NAWSA gave Paul control over the Congressional Committee whose job was to press for a Federal Amendment to the constitution, not just a state by state approach. Between 1912 and 1913, Paul and Burns worked to organize the congressional committee and build it into a robust political force.

Baldwin:

Another one of these women was Marie Louise Bottineau Baldwin—a Chippewa. Baldwin had been born on Ojibwe land but was educated in American society and went on to become the first Indigenous woman to graduate from the Washington College of Law in Washington D.C. Despite this, she was an outspoken advocate of Indigenous communities and also a suffragette. In fact, on the day of her graduation from law school, Baldwin was asked by a reporter if she considered herself a suffragette; in response, she laughed and stated: “Did you ever know that the Indian women were among the first suffragists and that they exercised the right of recall?” In chiding the reporter, Baldwin highlights the fact that Indigenous women—especially those from matrilineal communities—often held and exercised political power amongst their peoples. Still, as demonstrated by her track record as a suffragette, Baldwin clearly believed that women more broadly deserved the right to vote.

Woman at the Women's Suffrage Parade, The Atlantic

Woman at the Women's Suffrage Parade, The Atlantic

Suffrage Parade:

On March 3, 1913, they held a women’s suffrage parade in Washington DC the day before Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration. Paul has begun planning this since well before she was even granted a title in the women’s movement. Her planning was meticulous, she tapped every resource and connection she had in DC and in the Taft administration that was exiting, and her expert use of public relations kept suffrage and the parade in the media so frequently that people associated the parade with Wilson’s inauguration. Women were led down Pennsylvania Avenue by Inez Milholland atop a horse representing Columbia, a symbol of the United States. Following her women were grouped by alma mater demonstrating their expertise and education levels, women were then grouped by state showing that women in every state wanted the right to vote, women were also grouped by profession with various industries given somatic outfits to wear, showing the depth of the suffrage movement and how intersected so many women’s lives.

Baldwin also marched in the National Woman Suffrage Procession, though on her own terms. At first, the parade’s organizers had apparently asked her to create a float that paid tribute to Indigenous women quite broadly. Baldwin, however, refused to homogenize Indigenous women into a monolithic, stereotypical figure. Instead, she chose to march as a “modern Indigenous woman” and joined the ranks of other attorneys likely from the North Carolina delegation.

Planning for the parade was not, however, perfect. Paul had many factions within the suffrage movement to appease and made concessions to Southern suffragists at the expense of Black suffragists. Black leaders like Ida B Wells Barnett as well as Delta Sigma Theta, a black sorority from nearby Howard University, were left off of the program, and told that they could march in the back. Constrained by all the demands thrown at her, Paul said, “As far as I can see, we must have a white procession, or a Negro procession, or no procession at all.”

On March 3, 1913, they held a women’s suffrage parade in Washington DC the day before Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration. Paul has begun planning this since well before she was even granted a title in the women’s movement. Her planning was meticulous, she tapped every resource and connection she had in DC and in the Taft administration that was exiting, and her expert use of public relations kept suffrage and the parade in the media so frequently that people associated the parade with Wilson’s inauguration. Women were led down Pennsylvania Avenue by Inez Milholland atop a horse representing Columbia, a symbol of the United States. Following her women were grouped by alma mater demonstrating their expertise and education levels, women were then grouped by state showing that women in every state wanted the right to vote, women were also grouped by profession with various industries given somatic outfits to wear, showing the depth of the suffrage movement and how intersected so many women’s lives.

Baldwin also marched in the National Woman Suffrage Procession, though on her own terms. At first, the parade’s organizers had apparently asked her to create a float that paid tribute to Indigenous women quite broadly. Baldwin, however, refused to homogenize Indigenous women into a monolithic, stereotypical figure. Instead, she chose to march as a “modern Indigenous woman” and joined the ranks of other attorneys likely from the North Carolina delegation.

Planning for the parade was not, however, perfect. Paul had many factions within the suffrage movement to appease and made concessions to Southern suffragists at the expense of Black suffragists. Black leaders like Ida B Wells Barnett as well as Delta Sigma Theta, a black sorority from nearby Howard University, were left off of the program, and told that they could march in the back. Constrained by all the demands thrown at her, Paul said, “As far as I can see, we must have a white procession, or a Negro procession, or no procession at all.”

Mary Church Terrell, Wikimedia Commons

Mary Church Terrell, Wikimedia Commons

After being told that they would have to march in the back, Wells addressed the marchers the night before. Full of tears and trembling, she stated, “if they did not take a stand now in this great democratic parade then the colored women are lost.” Grace Trout, the leader of the Illinois contingent to which Wells belonged, sided with Paul and the segregationists. Wells left the room vowing not to march at all.

Of course, she would march. Wells stood on the sideline as the march began the next morning. And when the Illinois delegation walked past her, she calmly and collectively stepped into the street and joined them. This was a women's march, not a white women’s march. And women were going to get the right to vote together, not parceled off by race and class.

Mary Church Terrell, founder of the National Association of Colored Women marched with the all-Black delegation at the back. She later stated that she believed Paul and other white suffrage leaders would sacrifice Black women in order to get white women the vote. Paul of course denied that, but didn’t stop catering to racists within the movement.

Of course, she would march. Wells stood on the sideline as the march began the next morning. And when the Illinois delegation walked past her, she calmly and collectively stepped into the street and joined them. This was a women's march, not a white women’s march. And women were going to get the right to vote together, not parceled off by race and class.

Mary Church Terrell, founder of the National Association of Colored Women marched with the all-Black delegation at the back. She later stated that she believed Paul and other white suffrage leaders would sacrifice Black women in order to get white women the vote. Paul of course denied that, but didn’t stop catering to racists within the movement.

Woodrow Wilson, Library of Congress

Woodrow Wilson, Library of Congress

As the marchers made their way down Pennsylvania Avenue things seemed to be going well. Paul had planned ahead because the DC police had threatened not to protect her and asked for a regiment to be standing by. Thankfully she had.

What started as jeers from the crowd turned into a riot. Over 100 people ended up in the hospital as the DC police abandoned their positions along the parade route and let misogynists attack the women on the street. Newspapers blamed the DC police. Women’s suffrage was on the front page! Woodrow Wilson, the new president, was not the top story. If he wanted to have a successful presidency, women’s suffrage would have to pass.

1916 Election:

But Woodrow Wilson was not easy to break. While he said he supported women’s suffrage, he didn’t think that it was politically possible to pass it. We should also mention that he was formerly the president of Princeton, one of the Ivy League schools that didn’t support women getting degrees. Wilson came to suffrage events and gave speeches where he supported their work, but refused to take a policy position on it. So when he was up for reelection, Paul and Burns refused to endorse him.

What started as jeers from the crowd turned into a riot. Over 100 people ended up in the hospital as the DC police abandoned their positions along the parade route and let misogynists attack the women on the street. Newspapers blamed the DC police. Women’s suffrage was on the front page! Woodrow Wilson, the new president, was not the top story. If he wanted to have a successful presidency, women’s suffrage would have to pass.

1916 Election:

But Woodrow Wilson was not easy to break. While he said he supported women’s suffrage, he didn’t think that it was politically possible to pass it. We should also mention that he was formerly the president of Princeton, one of the Ivy League schools that didn’t support women getting degrees. Wilson came to suffrage events and gave speeches where he supported their work, but refused to take a policy position on it. So when he was up for reelection, Paul and Burns refused to endorse him.

National Women's Party, Library of Congress

National Women's Party, Library of Congress

The suffrage parade was not all good for women’s suffrage. Paul and Burns his true colors were beginning to show and their radical tactics for achieving women’s suffrage were not supported by other women in the movement. By February 1914 Paul and Burns were ousted from NAWSA and all of the funds they had raised for the congressional committee stripped from them. They rebranded as the National Women’s Party, a rival organization with more aggressive and radical positions than Shaw’s NAWSA.

As suffrage was fracturing and dividing over tactics, Carrie Chapman Catt returned to steer NAWSA through its final push for suffrage. In 1915, she returned as president of NAWSA. Catt proposed her “Winning Plan” which compromised between the factions to simultaneously fight for suffrage at the state and federal levels. She also received a 1 million dollar bequest from New York City magazine editor and publisher Miriam Folline Leslie “for the cause of woman suffrage.”

During the election year, the NWP traveled state to state to urge people to vote against Wilson and instead endorse a candidate who would support women’s suffrage… though none emerged. Wilson and his Republican opponent Charles Evan Hughes endorsed the state by state approach to women’s suffrage. Paul met with Hughes on behalf of her members and women who could vote in various, mostly western states. After the meeting she was disappointed, she said:

“Voting women will not accept a mere endorsement of the principle of suffrage. They are solely interested in the best method of protecting their own political rights and of emancipating the rest of their sex. The Republican Party wants the women’s votes. They are essential to the success of the party next fall. But it will not receive them by default.”

As suffrage was fracturing and dividing over tactics, Carrie Chapman Catt returned to steer NAWSA through its final push for suffrage. In 1915, she returned as president of NAWSA. Catt proposed her “Winning Plan” which compromised between the factions to simultaneously fight for suffrage at the state and federal levels. She also received a 1 million dollar bequest from New York City magazine editor and publisher Miriam Folline Leslie “for the cause of woman suffrage.”

During the election year, the NWP traveled state to state to urge people to vote against Wilson and instead endorse a candidate who would support women’s suffrage… though none emerged. Wilson and his Republican opponent Charles Evan Hughes endorsed the state by state approach to women’s suffrage. Paul met with Hughes on behalf of her members and women who could vote in various, mostly western states. After the meeting she was disappointed, she said:

“Voting women will not accept a mere endorsement of the principle of suffrage. They are solely interested in the best method of protecting their own political rights and of emancipating the rest of their sex. The Republican Party wants the women’s votes. They are essential to the success of the party next fall. But it will not receive them by default.”

Silent Sentinels Outside the White House, Wikimedia Commons

Silent Sentinels Outside the White House, Wikimedia Commons

The fact that a presidential candidate met with her, just shows how powerful politicking had become.

The NWP was narrowly focused, willing to endorse whichever candidate would support national suffrage. NAWSA on the other hand, backed Woodrow Wilson because of his continued effort to keep America out of World War I. Wilson won the election and within a month took the United States to war. For women on both issues, the reelection of Woodrow Wilson was a disappointment. Like in the Civil War decades before, many women became engrossed in the war movement. They served as nurses, within the new branch of the Marines for women, rolling bandages, volunteering, building victory gardens, and whatever needed to be done to support the country in war.

Silent Sentinels:

But unlike most women, the National Women’s Party did not relent. Starting on January 10, 1917, the women’s party began sending “silent sentinels” as they were referred to, to picket outside of the White House and keep relentless pressure on Woodrow Wilson to pass the amendment. They held "watchfires," where they burned copies of Wilson's speeches, and called him a hypocrite. They picketed six days a week, rain or shine. When the United States joined the war effort, what little support they had from onlookers in DC diminished. The suffragists were seen as unpatriotic, belittling a president while he was at war. For many, the president’s focus should have been solely on bringing American boys home, but Paul and Burns did not back down, they doubled down. They pointed out the hypocrisy of fighting for democracy abroad while American women could not fight at home. Insultingly, they used Wilson’s words against him:

The NWP was narrowly focused, willing to endorse whichever candidate would support national suffrage. NAWSA on the other hand, backed Woodrow Wilson because of his continued effort to keep America out of World War I. Wilson won the election and within a month took the United States to war. For women on both issues, the reelection of Woodrow Wilson was a disappointment. Like in the Civil War decades before, many women became engrossed in the war movement. They served as nurses, within the new branch of the Marines for women, rolling bandages, volunteering, building victory gardens, and whatever needed to be done to support the country in war.

Silent Sentinels:

But unlike most women, the National Women’s Party did not relent. Starting on January 10, 1917, the women’s party began sending “silent sentinels” as they were referred to, to picket outside of the White House and keep relentless pressure on Woodrow Wilson to pass the amendment. They held "watchfires," where they burned copies of Wilson's speeches, and called him a hypocrite. They picketed six days a week, rain or shine. When the United States joined the war effort, what little support they had from onlookers in DC diminished. The suffragists were seen as unpatriotic, belittling a president while he was at war. For many, the president’s focus should have been solely on bringing American boys home, but Paul and Burns did not back down, they doubled down. They pointed out the hypocrisy of fighting for democracy abroad while American women could not fight at home. Insultingly, they used Wilson’s words against him:

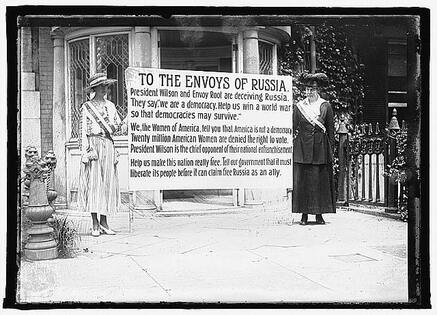

Women Protesting, Teaching American History

Women Protesting, Teaching American History

“WE SHALL FIGHT FOR THE THINGS WE HAVE ALWAYS HELD NEAREST TO OUR HEARTS.”

When the United States’ ally, Russia sent a delegation to meet with Wilson and discuss their mutual role in preserving democracy, Lucy Burns and Dora Lewis held a banner that read:

“We, the Women of America, tell you that America is not a democracy. Twenty million American Women are denied the right to vote. President Wilson is the chief opponent of their national enfranchisement.”

For mothers the connection between war and suffrage was obvious: the president was drafting their sons to go to war and they had no say in it. For many women suffrage became a symbol of anti-war sentiments.

But things eventually became tense. As women picketed outside the White House, onlookers became increasingly hostile and agitated. Soldiers harassed the women. In June of 1917, police tried to confiscate the women’s banner, which obviously violated free-speech. Women resisted. They were arrested. Eventually the government came up with a scheme to charge them with blocking traffic because they were attracting so much attention. The women argued their case in court claiming that they were “political prisoners.“ And that they were arrested because they disagreed with the ruling political party. Arrested day after day, at least 150 different women were imprisoned during this period. They refused to pay their fines and were taken to the Occoquan Workhouse prison in Virginia to work off their debts. Once released, they would be back out on the picket line the next day.

When the United States’ ally, Russia sent a delegation to meet with Wilson and discuss their mutual role in preserving democracy, Lucy Burns and Dora Lewis held a banner that read:

“We, the Women of America, tell you that America is not a democracy. Twenty million American Women are denied the right to vote. President Wilson is the chief opponent of their national enfranchisement.”

For mothers the connection between war and suffrage was obvious: the president was drafting their sons to go to war and they had no say in it. For many women suffrage became a symbol of anti-war sentiments.

But things eventually became tense. As women picketed outside the White House, onlookers became increasingly hostile and agitated. Soldiers harassed the women. In June of 1917, police tried to confiscate the women’s banner, which obviously violated free-speech. Women resisted. They were arrested. Eventually the government came up with a scheme to charge them with blocking traffic because they were attracting so much attention. The women argued their case in court claiming that they were “political prisoners.“ And that they were arrested because they disagreed with the ruling political party. Arrested day after day, at least 150 different women were imprisoned during this period. They refused to pay their fines and were taken to the Occoquan Workhouse prison in Virginia to work off their debts. Once released, they would be back out on the picket line the next day.

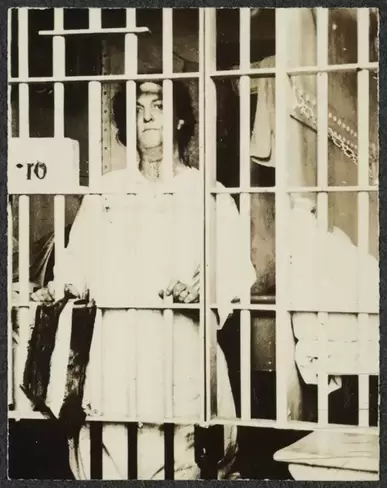

Suffragettes at Occoquan Workhouse, Richmond Public Library

Suffragettes at Occoquan Workhouse, Richmond Public Library

Night of Terror and Hunger Strike:

Resistance to suffragists became violent and hostile. Paul and Burns were also arrested. Paul was sentenced to 7 months in Occoquan in October 1917. She began a hunger strike. The prison guards responded by force feeding her: forcing a tube down her throat and dropping raw eggs into her mouth twice a day. Then they tried to say she was insane and took her to a psychiatric hospital. The superintendent, William Alanson White, refused to admit her, stating that she was "perfectly calm, yet determined."

Outside the prison, suffragists rallied behind her. Many went to picket the White House for suffrage and also picket on behalf of Paul.

Resistance to suffragists became violent and hostile. Paul and Burns were also arrested. Paul was sentenced to 7 months in Occoquan in October 1917. She began a hunger strike. The prison guards responded by force feeding her: forcing a tube down her throat and dropping raw eggs into her mouth twice a day. Then they tried to say she was insane and took her to a psychiatric hospital. The superintendent, William Alanson White, refused to admit her, stating that she was "perfectly calm, yet determined."

Outside the prison, suffragists rallied behind her. Many went to picket the White House for suffrage and also picket on behalf of Paul.

Suffragette Helena Hill in Jail, NPS.Gov

Suffragette Helena Hill in Jail, NPS.Gov

On November 14, 1917, 33 suffragists from the NWP were brutally beaten and tortured by 40 male prison guards, to “teach them a lesson.” This night went down in history as the “Night of Terror.” Testimony shared in a later investigation proved that the suffragists were dragged, beaten, choked, slammed, pinched, and kicked. Dora Lewis' arm was twisted behind her back. They twice slammed her into an iron bed where she fell unconscious and bleeding. Alice Cosu thought Lewis was dead and the panic caused her to suffer a heart attack. She was denied medical treatment until the next morning. Burns tried to check in with everyone and make sure they were ok. She started a roll call, which led her to be identified as the leader. The guards handcuffed her arms to the cell bars above her head, leaving her bleeding on tiptoe until they took her down. Burns and the other suffragists went on hunger strike for three days following the Night of Terror. Burns was removed and taken to a different prison where she too was force-fed by putting a tube through her nostril, a process that caused horrible nose bleeds. Burns spent more time in prison than other American suffragists. While all of this was going on, it was not public knowledge. The press had yet to find out this information, and American support of the NWP remained low.

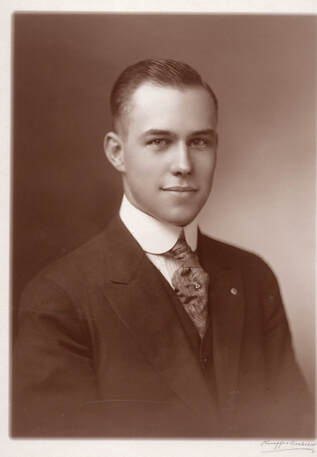

Dudley Field Malone, worked as an attorney and campaign adviser to Wilson. He resigned to represent the Silent Sentinels in court. He also took letters that the suffragist had written in prison and secretly released them to the NWP newspaper, The Suffragist. The night of terror, Paul and Burns’s treatment, and the unjust arrests of the picketers was major news across the country And helped bring support for the suffrage cause. Not only did he help get all of the women released from prison, he also had their wrongful arrests overturned by the unanimous vote. Malone would go on to marry Doris Stevens, an important and active silent sentinel imprisoned at Occoquan.

Dudley Field Malone, worked as an attorney and campaign adviser to Wilson. He resigned to represent the Silent Sentinels in court. He also took letters that the suffragist had written in prison and secretly released them to the NWP newspaper, The Suffragist. The night of terror, Paul and Burns’s treatment, and the unjust arrests of the picketers was major news across the country And helped bring support for the suffrage cause. Not only did he help get all of the women released from prison, he also had their wrongful arrests overturned by the unanimous vote. Malone would go on to marry Doris Stevens, an important and active silent sentinel imprisoned at Occoquan.

Mary B. Talbet, Wikimedia Commons

Mary B. Talbet, Wikimedia Commons

Paul wrote: "Seems almost unthinkable now, doesn't it? It was shocking that a government of men could look with such extreme contempt on a movement that was asking nothing except such a simple little thing as the right to vote."

African American Women:

Meanwhile, NAWSA was busy fighting for Catt’s Winning Plan. Catt’s leadership secured several key states: New York, Michigan, Oklahoma, and South Dakota in 1917 and 1918. Catt was winning in one respect and losing in another. She consistently catered to racists within the movement.

Mary B. Talbert was a member of the NACW and NAACP. In 1915 she wrote in The Crisis, “with us as colored women, this struggle becomes two-fold, first, because we are women and second, because we are colored women.”

African American Women:

Meanwhile, NAWSA was busy fighting for Catt’s Winning Plan. Catt’s leadership secured several key states: New York, Michigan, Oklahoma, and South Dakota in 1917 and 1918. Catt was winning in one respect and losing in another. She consistently catered to racists within the movement.

Mary B. Talbert was a member of the NACW and NAACP. In 1915 she wrote in The Crisis, “with us as colored women, this struggle becomes two-fold, first, because we are women and second, because we are colored women.”

Adella Logan Hunt, Wikimedia Commons

Adella Logan Hunt, Wikimedia Commons

Black women were often belittled in how they might use the vote. Nannie Helen Burroughs aptly retorted, “What can she do without it?” Burroughs and other Black women made clear that Black women “needs the ballot, to reckon with men who place no value upon her virtue, and to mould [sic] healthy sentiment in favor of her own protection.”

Adella Hunt Logan concurred, adding: “If white American women, with all their natural and acquired advantages, need the ballot, that right protective of all other rights; if Anglo Saxons have been helped by it... how much more do black Americans, male and female need the strong defense of a vote to help secure them their right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness?”

Racism, discrimination, and racial violence forced Black women toward civil rights activism, in addition to suffrage. Perhaps overly optimistic, Angelina Weld Grimké, the great niece of abolitionist and suffragist Angelina Grimké Weld, stated, “injustices will end [between the sexes when woman] gains the ballot.”

Adella Hunt Logan concurred, adding: “If white American women, with all their natural and acquired advantages, need the ballot, that right protective of all other rights; if Anglo Saxons have been helped by it... how much more do black Americans, male and female need the strong defense of a vote to help secure them their right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness?”

Racism, discrimination, and racial violence forced Black women toward civil rights activism, in addition to suffrage. Perhaps overly optimistic, Angelina Weld Grimké, the great niece of abolitionist and suffragist Angelina Grimké Weld, stated, “injustices will end [between the sexes when woman] gains the ballot.”

Suffragettes, Wikimedia Commons

Suffragettes, Wikimedia Commons

Ratification:

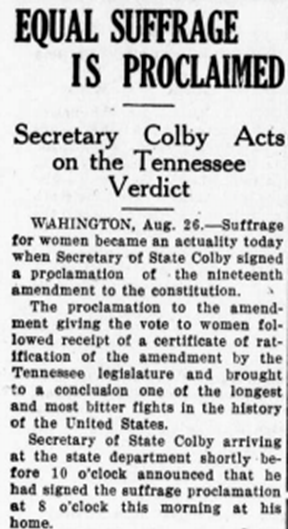

Then finally, in 1918, Wilson put the weight of his presidency behind the cause of suffrage and supported a national constitutional amendment. But why the sudden change of heart? Was it the public pressure from the torture of Paul and Burns? Or was it pragmatic given how many states Catt was able to secure? We may never know. Wilson claimed he was not swayed by the “radicals” in the NWP, and stated that the amendment's purpose was to help win World War I.

The amendment passed Congress the next year on August 26, 1920. It thus began a long ratification process.

Ratification in Tennessee:

To ratify an amendment to the Constitution, it needs to be approved by three quarters of the states— a very high bar. Suffragists at the state level fought to have the amendment ratified. It took a year, but finally the 36th state came to ratify the amendment: Tennessee.

Then finally, in 1918, Wilson put the weight of his presidency behind the cause of suffrage and supported a national constitutional amendment. But why the sudden change of heart? Was it the public pressure from the torture of Paul and Burns? Or was it pragmatic given how many states Catt was able to secure? We may never know. Wilson claimed he was not swayed by the “radicals” in the NWP, and stated that the amendment's purpose was to help win World War I.

The amendment passed Congress the next year on August 26, 1920. It thus began a long ratification process.

Ratification in Tennessee:

To ratify an amendment to the Constitution, it needs to be approved by three quarters of the states— a very high bar. Suffragists at the state level fought to have the amendment ratified. It took a year, but finally the 36th state came to ratify the amendment: Tennessee.

Harry T. Burns, Wikimedia Commons

Harry T. Burns, Wikimedia Commons

Tennessee was the last possible hope that the Amendment would get ratified. Like elsewhere in the country, the all male legislature met to discuss the Amendment and, yet again, debate women’s status as citizens. Harry T. Burn was one of these state representatives. He supported suffrage, but the men in his district did not. Debate in Tennessee raged on in what became known as the War of the Roses. Pro-suffrage legislators wore yellow roses, while anti-suffragists wore red. There were accounts of bribery, negotiations, and lots of drinking. Legislators would be seen wearing a yellow flower one day and a red one the next.

In this context Febb Burn, Harry’s mom wrote him a letter. She said, “Hurrah, and vote for suffrage, and don’t keep them in doubt… Don’t forget to be a good boy and help Mrs. ‘Thomas Catt’ with her ‘rats.’ Is she the one that put rat in ratification? Ha! No more from Mama this time. With lots of love.”

Her son, wearing the red anti-suffrage flower, and with his mothers letter in his pocket, dramatically changed his vote in favor of suffrage. Pandemonium followed.

In this context Febb Burn, Harry’s mom wrote him a letter. She said, “Hurrah, and vote for suffrage, and don’t keep them in doubt… Don’t forget to be a good boy and help Mrs. ‘Thomas Catt’ with her ‘rats.’ Is she the one that put rat in ratification? Ha! No more from Mama this time. With lots of love.”

Her son, wearing the red anti-suffrage flower, and with his mothers letter in his pocket, dramatically changed his vote in favor of suffrage. Pandemonium followed.

Banks Turner, Wikimedia Commons

Banks Turner, Wikimedia Commons

When things calmed, the roll call resumed. Anti-suffragists appeared to be winning. Then, after sitting silently through his turn, Banks Turner broke his silence as the antis were clearly winning and cast a vote: “Mr. Speaker, I wish to be recorded as voting Aye.”

Women’s suffrage passed by ONE vote at the very last second. The chamber was in uproar, but the vote was won.

By the end of this era, so much remained in question. What would happen for these newly enfranchised women? Would there emerge a women’s voting block? Would women of color be granted full access to the vote, or would they too be subjected to discrimination at the polls? How long would it take for noncitizens, Chinese and indigenous women to gain the vote? What would the next battles for women’s liberation look like?

Women’s suffrage passed by ONE vote at the very last second. The chamber was in uproar, but the vote was won.

By the end of this era, so much remained in question. What would happen for these newly enfranchised women? Would there emerge a women’s voting block? Would women of color be granted full access to the vote, or would they too be subjected to discrimination at the polls? How long would it take for noncitizens, Chinese and indigenous women to gain the vote? What would the next battles for women’s liberation look like?

Draw your own conclusions

|

Learn how to teach with inquiry.

Many of these lesson plans were sponsored in part by the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources Eastern Region Program, coordinated by Waynesburg University, the History and Social Studies Education Faculty at Plymouth State University, and the Patrons of the Remedial Herstory Project. |

Lesson Plans from Other Organizations

- The National Women's History Museum has lesson plans on women's history.

- The Guilder Lehrman Institute for American History has lesson plans on women's history.

- The NY Historical Society has articles and classroom activities for teaching women's history.

- Unladylike 2020, in partnership with PBS, has primary sources to explore with students and outstanding videos on women from the Progressive era.

- The Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media has produced recommendations for teaching women's history with primary sources and provided a collection of sources for world history. Check them out!

- The Stanford History Education Group has a number of lesson plans about women in US History.

Period Specific Lesson Plans from Other Organizations

- Stanford History Education Group: The 19th Amendment was passed seventy-two years after the Seneca Falls Convention. This fact demonstrates the strong opposition that women’s suffrage faced. In this lesson, students study a speech and anti-suffrage literature to explore the reasons why so many Americans, including many women, opposed women's suffrage.

- C3 Teachers: This inquiry leads students through an investigation of voting rights in America. By investigating the compelling question “Was the vote enough?” students evaluate both sides of the early twentieth century quest to expand suffrage to women. The formative performance tasks build on knowledge and skills through the course of the inquiry and help students determine if getting the vote was enough to give women full social and political equality. Students create an evidence-based argument about whether or not the vote is enough.

- C3 Teachrs: This inquiry examines the emergence of the women’s suffrage movement in the 19th century as an effort to expand women’s political and economic rights, and it extends that investigation into the present. The compelling question “What does it mean to be equal?” provides students with an opportunity to examine the nature of equality and the changing conditions for women in American society from the 19th century to today. Each supporting question begins by asking about 19th-century women’s rights and then asks about contemporary gender equality. The relationship between women’s rights and gender equality is a central focus of this inquiry. Students begin the inquiry by exploring the legal limits placed on women in the 19th century and how efforts to gain rights were undertaken by women at the Seneca Falls Convention.

- C3 Teachers: This inquiry leads students through an investigation of the women’s suffrage movement in New York State as an example of how different groups of people have gained equal rights and freedoms over time. Through examining the role women played in society before the 20th century and the efforts made by women to gain the right to vote, students will be prepared to develop arguments supported by evidence that answer the compelling question “What did it take for women to be considered ‘equal’ to men in New York?” Subsequent inquiries could be developed around other groups who have struggled to gain rights and freedoms, including, but not limited to, Native Americans and African Americans.

- Gilder Lehrman: Over the course of two lessons, students will analyze primary source documents in order to examine the factors that contributed to the exclusion of American women from the right to vote and the battle for full enfranchisement. They will read and interpret complex documents, engage in discussions, and, in order to demonstrate comprehension, answer critical thinking questions.

- National Women’s History Museum: Was the woman suffrage movement inclusive? This lesson seeks to explore the role of Black women in the Women’s Suffrage Movement and their exclusion from the generally accepted Women’s Suffrage narrative. Students will examine primary and secondary sources to explore some of the unsung heroes of the Women’s Suffrage Movement and the contributions of these unsung heroes to the movement. As a summative assessment, students will create an exhibit detailing the contributions of a Black Suffragist.

- Gilder Lehrman: The American women’s suffrage movement has always been identified with its two founders, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, whose strong, enthusiastic leadership defined the movement. When they retired from active participation in the cause, the loss of that personal connection naturally affected the movement’s future. The transition was not an easy one. As the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), the organization that Stanton and Anthony had led, headed into the twentieth century, it lost the dynamism and direction of the nineteenth-century association. Successors had difficulty measuring up to Stanton and Anthony, and the organization was unable to develop a focused plan for its difficult campaign. Alice Paul joined the fray in 1910. Did she pick up where Stanton and Anthony left off? The answer to that question is not obvious. Almost anyone familiar with the suffrage movement has a notion of Stanton and Anthony’s leadership, but most people know far less about Alice Paul, whose contributions are not often remembered in the movement’s history. Investigation into Paul’s life and contributions reveals that she had a very different approach to the battle for the vote; that she was a radical compared to the NAWSA leaders who succeeded Stanton and Anthony; and that she devoted her life to winning the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment and, later, to the effort to secure the enactment of the Equal Rights Amendment. Any history of the women’s suffrage movement that fails to take into account Alice Paul and her organization, the National Woman’s Party, is incomplete. Using the classroom as a historical laboratory, students can use primary and secondary sources to research the history of Alice Paul, her associates, and the NWP. The students can be historians; they can discover the history of Alice Paul and her fight for women’s suffrage.

- Edcitement: An article originally published in the 1991 Session Weekly of the Minnesota House of Representatives recalls the arguments put forth in objection to the Minnesota Equal Suffrage Association's decision, early in the 20th century, to push for the right of women to vote in presidential elections. One lawmaker declared that all-male voting was "designed by our forefathers." Later, Rep. Thomas Girling argued that "women shouldn't be dragged into the dirty pool of politics." Approving such a measure, he said, would "cause irreparable damage at great expense to the state." When the Senate took up the bill, one member asserted that "disaster and ruin would overtake the nation." Suffrage would lead inevitably to "government by females" because "men could never resist the blandishments of women." Instead, he recommended that women "attach themselves to some man who will represent them in public affairs." Though such arguments may now sound rather ridiculous to some, they are closely related to entrenched views of women that took more than a century to overcome (assuming one agrees they have been overcome). Understanding the positions of the suffrage and anti-suffrage movements—as expressed in archival broadsides, speeches, pamphlets, and political cartoons—will help your students better appreciate the struggle for women's rights and the vestiges of the anti-suffrage positions that lasted at least through the 1960s and, perhaps, to the present day.

- PBS and DPLA: This collection uses primary sources to explore the campaign for women's suffrage through the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment. Digital Public Library of America Primary Source Sets are designed to help students develop their critical thinking skills and draw diverse material from libraries, archives, and museums across the United States. Each set includes an overview, ten to fifteen primary sources, links to related resources, and a teaching guide. These sets were created and reviewed by the teachers on the DPLA's Education Advisory Committee.

- National History Day: Ida B. Wells (1862-1931) was born to slave parents in Holly Springs, Mississippi, on July 16, 1862, two months before President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. As a young girl, Wells watched her parents work as political activists during Reconstruction. In 1878, tragedy struck as Wells lost both of her parents and a younger brother in a yellow fever epidemic. To support her younger siblings, Wells became a teacher, eventually moving to Memphis, Tennessee. In 1884, Wells found herself in the middle of a heated lawsuit. After purchasing a first-class train ticket, Wells was ordered to move to a segregated car. She refused to give up her seat and was forcibly removed from the train. Wells filed suit against the railroad and won. This victory was short lived, however, as the Tennessee Supreme Court overturned the lower court ruling in 1887. In 1892, Wells became editor and co-owner of The Memphis Free Speech and Headlight. Here, she used her skills as a journalist to champion the causes for African American and women’s rights. Among her most known works were those on behalf of anti-lynching legislation. Until her death in 1931, Ida B. Wells dedicated her life to what she referred to as a “crusade for justice.”

- Unladylike: Learn about Mary Church Terrell, daughter of former slaves and one of the first African American women to earn both a Bachelor and a Master’s degree, who became a national leader for civil rights and women’s suffrage, in this video from Unladylike2020. Terrell was one of the earliest anti-lynching advocates and joined the suffrage movement, focusing her life’s work on racial uplift—the belief that blacks would end racial discrimination and advance themselves through education, work, and community activism. She helped found the National Association of Colored Women (NACW) and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Support materials include discussion questions and teaching tips for research projects. Primary source analysis activities emphasize how the content connects to racial justice issues that continue today, including a close reading of the Emmett Till Antilynching Bill of 2020. Sensitive: This resource contains material that may be sensitive for some students. Teachers should exercise discretion in evaluating whether this resource is suitable for their class.

Suffragettes and Racism

Sojourner Truth: Aint I a Woman

Truth was an escaped slave and consistent women’s rights advocate. She gave voice to the feelings of many Black women that they were abandoned by both Black and women’s groups—when the issues each addressed both had adverse effects on her.

”Well, children, where there is so much racket there must be something out of kilter. I think that 'twixt the negroes of the South and the women at the North, all talking about rights, the white men will be in a fix pretty soon. But what's all this here talking about?

That man over there says that women need to be helped into carriages, and lifted over ditches, and to have the best place everywhere. Nobody ever helps me into carriages, or over mud-puddles, or gives me any best place! And ain't I a woman? Look at me! Look at my arm! I have ploughed and planted, and gathered into barns, and no man could head me! And ain't I a woman? I could work as much and eat as much as a man - when I could get it - and bear the lash as well! And ain't I a woman? I have borne thirteen children, and seen most all sold off to slavery, and when I cried out with my mother's grief, none but Jesus heard me! And ain't I a woman?

Then they talk about this thing in the head; what's this they call it? [member of audience whispers, "intellect"] That's it, honey. What's that got to do with women's rights or negroes' rights? If my cup won't hold but a pint, and yours holds a quart, wouldn't you be mean not to let me have my little half measure full?

Then that little man in black there, he says women can't have as much rights as men, 'cause Christ wasn't a woman! Where did your Christ come from? Where did your Christ come from? From God and a woman! Man had nothing to do with Him.

If the first woman God ever made was strong enough to turn the world upside down all alone, these women together ought to be able to turn it back , and get it right side up again! And now they is asking to do it, the men better let them.

Obliged to you for hearing me, and now old Sojourner ain't got nothing more to say.

Truth, Sojourner. "Ain't I a Woman?” Women's Convention, Akron, Ohio. December, 1851. Retrieved from https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/mod/sojtruth-woman.asp.

”Well, children, where there is so much racket there must be something out of kilter. I think that 'twixt the negroes of the South and the women at the North, all talking about rights, the white men will be in a fix pretty soon. But what's all this here talking about?

That man over there says that women need to be helped into carriages, and lifted over ditches, and to have the best place everywhere. Nobody ever helps me into carriages, or over mud-puddles, or gives me any best place! And ain't I a woman? Look at me! Look at my arm! I have ploughed and planted, and gathered into barns, and no man could head me! And ain't I a woman? I could work as much and eat as much as a man - when I could get it - and bear the lash as well! And ain't I a woman? I have borne thirteen children, and seen most all sold off to slavery, and when I cried out with my mother's grief, none but Jesus heard me! And ain't I a woman?

Then they talk about this thing in the head; what's this they call it? [member of audience whispers, "intellect"] That's it, honey. What's that got to do with women's rights or negroes' rights? If my cup won't hold but a pint, and yours holds a quart, wouldn't you be mean not to let me have my little half measure full?

Then that little man in black there, he says women can't have as much rights as men, 'cause Christ wasn't a woman! Where did your Christ come from? Where did your Christ come from? From God and a woman! Man had nothing to do with Him.

If the first woman God ever made was strong enough to turn the world upside down all alone, these women together ought to be able to turn it back , and get it right side up again! And now they is asking to do it, the men better let them.

Obliged to you for hearing me, and now old Sojourner ain't got nothing more to say.

Truth, Sojourner. "Ain't I a Woman?” Women's Convention, Akron, Ohio. December, 1851. Retrieved from https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/mod/sojtruth-woman.asp.

Susan B Anthony: The Revolution

Anthony was a founding member of NWSA and of NAWSA. She was furious at the possibility that all men would get the vote and not also all women, a concept called universal suffrage. She stated she would cut off her arm before working for Negro rights before women’s rights. In 1869, Anthony defended her position in favor of woman suffrage in her suffrage newspaper The Revolution.

The Revolution criticizes, ‘opposes’ the fifteenth amendment, not for what it is, but for what it is not. Not because it enfranchises black men, but because it does not enfranchise all women, black and white. It is not the little good it proposes, but the greater evil it perpetuates that we deprecate. It is not that in the abstract we do not rejoice that black men are to become equals of white men, but that we deplore the fact that two million (sic) black women, hitherto the political and social equals of the men by their side, are to become subjects, slaves of these men. Our protest is not that all men are lifted out of the degradation of disfranchisement, but that all women are left in. The Revolution and the National Women’s Suffrage Association make women’s suffrage their test of loyalty, not Negro suffrage, not Maine law or prohibition. Do you believe women should vote? Is the one and only question in our catechism.

Anthony, Susan B. The Revolution. October 7, 1869. Retrieved from Susan B. Anthony Birthplace Museum. http://www.susanbanthonybirthplace.com/racism.html.

The Revolution criticizes, ‘opposes’ the fifteenth amendment, not for what it is, but for what it is not. Not because it enfranchises black men, but because it does not enfranchise all women, black and white. It is not the little good it proposes, but the greater evil it perpetuates that we deprecate. It is not that in the abstract we do not rejoice that black men are to become equals of white men, but that we deplore the fact that two million (sic) black women, hitherto the political and social equals of the men by their side, are to become subjects, slaves of these men. Our protest is not that all men are lifted out of the degradation of disfranchisement, but that all women are left in. The Revolution and the National Women’s Suffrage Association make women’s suffrage their test of loyalty, not Negro suffrage, not Maine law or prohibition. Do you believe women should vote? Is the one and only question in our catechism.

Anthony, Susan B. The Revolution. October 7, 1869. Retrieved from Susan B. Anthony Birthplace Museum. http://www.susanbanthonybirthplace.com/racism.html.

Susan B. Anthony: to Booker T. Washington

This letter was written by Anthony to Booker T. Washington, the founder of the Tuskeegee Institute, who, along with his wife, Margaret Murray, educated free men and women in industrial work, among other initiatives. Anthony was a founding member of NWSA and of NAWSA.

N.Y. [City] Jan. 23, 1900

My Dear Friend: I received yours of the 16th. Certainly whenever I go to Atlanta again, it is my intention to visit Tuskegee. I am, however, hoping that my time of going will be postponed to next Autumn, when the legislatures of several of the Southern States will be in session. I think then would be a much better time for us to be in the South, and to speak perchance before every one of the legislatures, and thus send at least a representative from every district in the state, home to his constituents with a little idea of what this woman's rights movement means.

It is one of my dreams to visit Tuskegee, and to see you and Mrs. Washington and Mrs. [Adella Hunt] Logan, and all of the good men and women engaged in the splendid work of that institute. Wishing you the best of success, I am, Very sincerely yours,

Susan B. Anthony

Anthony, Susan B. “Letter from Susan Brownell Anthony to Booker T. Washington.” New York City. January, 23 1900. The Booker T. Washington Papers, Library of Congress. Published in Louis R. Harlan and Raymond W. Smock, eds., The Booker T. Washington Papers. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1976, 5:419. Retrieved from http://www.nzdl.org.

N.Y. [City] Jan. 23, 1900

My Dear Friend: I received yours of the 16th. Certainly whenever I go to Atlanta again, it is my intention to visit Tuskegee. I am, however, hoping that my time of going will be postponed to next Autumn, when the legislatures of several of the Southern States will be in session. I think then would be a much better time for us to be in the South, and to speak perchance before every one of the legislatures, and thus send at least a representative from every district in the state, home to his constituents with a little idea of what this woman's rights movement means.

It is one of my dreams to visit Tuskegee, and to see you and Mrs. Washington and Mrs. [Adella Hunt] Logan, and all of the good men and women engaged in the splendid work of that institute. Wishing you the best of success, I am, Very sincerely yours,

Susan B. Anthony

Anthony, Susan B. “Letter from Susan Brownell Anthony to Booker T. Washington.” New York City. January, 23 1900. The Booker T. Washington Papers, Library of Congress. Published in Louis R. Harlan and Raymond W. Smock, eds., The Booker T. Washington Papers. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1976, 5:419. Retrieved from http://www.nzdl.org.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton: Manhood Suffrage

During the debates over the 15th Amendment, Stanton published these comments in the suffrage newspaper The Revolution. Some historians have argued that she was attempting to use male logic against them. Stanton was a founding member of NWSA and later NAWSA.

“Think of Patrick and Sambo [derogatory, meaning mixed-race] and Hans and Yung Tung who do not know the difference between a Monarchy and a Republic, who never read the Declaration of Independence or Webster’s spelling book, making laws for Lydia Maria Child, Lucretia Mott or Fanny Kemble. Think of jurors drawn from these ranks to try young girls for the crime of infanticide.”

Stanton, Elizabeth Cady. “Manhood Suffrage.” The Revolution. Retrieved from Susan B. Anthony Birthplace Museum. http://www.susanbanthonybirthplace.com/racism.html.

“Think of Patrick and Sambo [derogatory, meaning mixed-race] and Hans and Yung Tung who do not know the difference between a Monarchy and a Republic, who never read the Declaration of Independence or Webster’s spelling book, making laws for Lydia Maria Child, Lucretia Mott or Fanny Kemble. Think of jurors drawn from these ranks to try young girls for the crime of infanticide.”

Stanton, Elizabeth Cady. “Manhood Suffrage.” The Revolution. Retrieved from Susan B. Anthony Birthplace Museum. http://www.susanbanthonybirthplace.com/racism.html.

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper: Speech at Women's Rights Convention

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper was an active abolitionist made famous in the North for her abolition speeches and open letter to John Brown. This speech comes from the Eleventh National Women’s Rights Convention in New York City in May of 1866.

I feel I am something of a novice upon this platform. Born of a race whose inheritance has been outrage and wrong, most of my life had been spent in battling against those wrongs. But I did not feel as keenly as others, that I had these rights, in common with other women, which are now demanded. About two years ago, I stood within the shadows of my home. A great sorrow had fallen upon my life. My husband had died suddenly, leaving me a widow, with four children, one my own, and the others stepchildren. I tried to keep my children together. But my husband died in debt; and before he had been in his grave three months, the administrator had swept the very milk-crocks and wash tubs from my hands. I was a farmer’s wife and made butter for the Columbus market; but what could I do, when they had swept all away? They left me one thing-and that was a looking glass! Had I died instead of my husband, how different would have been the result! By this time he would have had another wife, it is likely; and no administrator would have gone into his house, broken up his home, and sold his bed, and taken away his means of support…

I do not believe that giving the woman the ballot is immediately going to cure all the ills of life. I do not believe that white women are dew-drops just exhaled from the skies. I think that like men they may be divided into three classes, the good, the bad, and the indifferent. The good would vote according to their convictions and principles; the bad, as dictated by preju[d]ice or malice; and the indifferent will vote on the strongest side of the question, with the winning party.

You white women speak here of rights. I speak of wrongs. I, as a colored woman, have had in this country an education which has made me feel… against every man, and every man’s hand against me. Let me go to-morrow morning and take my seat in one of your street cars-I do not know that they will do it in New York, but they will in Philadelphia-and the conductor will put up his hand and stop the car rather than let me ride… Have women nothing to do with this?...

Talk of giving women the ballot-box? Go on. It is a normal school, and the white women of this country need it. While there exists this brutal element in society which tramples upon the feeble and treads down the weak, I tell you that if there is any class of people who need to be lifted out of their airy nothings and selfishness, it is the white women of America.