5. 800-400 BCE European Founding Myths and Women’s Place

|

Ancient Rome and Greece established gender norms that would last millennia in the western world. These norms diminished women's rights and subjugated them to the domestic sphere. And yet, there was nuance and differences across the early western world.

Trigger Warning: for discussion of sexual assault and rape. |

|

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

The ancient world saw the rise of professional historians and thus more is known about the lives, stories, and experiences of people who lived then, even women. However, almost everything we know about them was recorded by men. While these ancient city states and budding empires are known for pretty amazing things like democracy, enduring philosophies, and uniting massive empires, very little of this “progress” was designed by or for women and often these ideologies laid the groundwork for millennia of oppression for women every settled place in the world. Not all women’s experience in the ancient past were positive, so this may be triggering for some related to discussion of sexual assault and rape.

Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece is one of the few places in the ancient world where we are able to learn about the experiences of women, from women writers themselves. Much of what women wrote about was love in the form of poetry, and they were pretty good at it. In the 5th century BCE, Korinna of Boeotia beat Theban poet Pindar in competition five times.

For the Greeks, love did not always exist in marriage. Sappho of the Greek island Lesbos, is perhaps the most famous poet of ancient Greece. Only one of her poems survives in complete form, while quotes and other fragments from her are referenced in other surviving literature. Sappho is known for her passionate poetry about her romantic love for another woman. She writes: “I would remind you… of all the loveliness that we have shared together… you wove around yourself by my side.”

But sex was another matter. Attitudes on sexual relations varied according to class and gender. Women’s role was to produce legitimate children, so therefore extramarital relations with other men were suspect. Men however could have concubines, hire prostitutes, or even patronize well- educated women called hetaira, not just for sex, but their skills in dance, music, and conversation.

Custom and tradition required that women give birth, an act that took the lives of countless women. To be married in most of world history was to triple your chances of premature death. A double standard applied to male and female sexuality and cost many women their lives. Women judged to be unchaste were murdered by their own families in every region of the world. These so-called “honor killings,” which should really be called “misogyny killings,” are still legal in some parts of the world. A prehistoric grave in Britain found the bodies of two women that had been buried naked and alive, the younger woman had been brutally raped, her assailant using a spear through the knee to pin her down. She was later killed by her own family for her loss of virginity to a rapist.

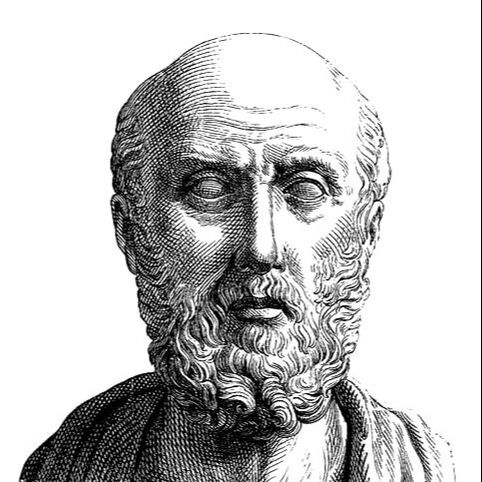

Because so much of a woman’s life revolved around her uterus, it’s no wonder medical writing of this time focused a lot on that. Hippocrates is known today for the Hippocratic oath that doctors take to do no harm. He was an ancient Greek physician whose ideas were recorded by other male physicians years later. The compilation of medical works attributed to Hippocrates, known as The Hippocratic Corpus, included treatises like Diseases of Women, Nature of Women, and Diseases of Young Girls. He looked for natural causes rather than godly retribution for disease and is the work from which almost all western medical thinking is derived even today. Keep in mind this was written before autopsies were done so they knew very little about internal organs.

Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece is one of the few places in the ancient world where we are able to learn about the experiences of women, from women writers themselves. Much of what women wrote about was love in the form of poetry, and they were pretty good at it. In the 5th century BCE, Korinna of Boeotia beat Theban poet Pindar in competition five times.

For the Greeks, love did not always exist in marriage. Sappho of the Greek island Lesbos, is perhaps the most famous poet of ancient Greece. Only one of her poems survives in complete form, while quotes and other fragments from her are referenced in other surviving literature. Sappho is known for her passionate poetry about her romantic love for another woman. She writes: “I would remind you… of all the loveliness that we have shared together… you wove around yourself by my side.”

But sex was another matter. Attitudes on sexual relations varied according to class and gender. Women’s role was to produce legitimate children, so therefore extramarital relations with other men were suspect. Men however could have concubines, hire prostitutes, or even patronize well- educated women called hetaira, not just for sex, but their skills in dance, music, and conversation.

Custom and tradition required that women give birth, an act that took the lives of countless women. To be married in most of world history was to triple your chances of premature death. A double standard applied to male and female sexuality and cost many women their lives. Women judged to be unchaste were murdered by their own families in every region of the world. These so-called “honor killings,” which should really be called “misogyny killings,” are still legal in some parts of the world. A prehistoric grave in Britain found the bodies of two women that had been buried naked and alive, the younger woman had been brutally raped, her assailant using a spear through the knee to pin her down. She was later killed by her own family for her loss of virginity to a rapist.

Because so much of a woman’s life revolved around her uterus, it’s no wonder medical writing of this time focused a lot on that. Hippocrates is known today for the Hippocratic oath that doctors take to do no harm. He was an ancient Greek physician whose ideas were recorded by other male physicians years later. The compilation of medical works attributed to Hippocrates, known as The Hippocratic Corpus, included treatises like Diseases of Women, Nature of Women, and Diseases of Young Girls. He looked for natural causes rather than godly retribution for disease and is the work from which almost all western medical thinking is derived even today. Keep in mind this was written before autopsies were done so they knew very little about internal organs.

Hippocrates, Wikimedia Commons

Hippocrates, Wikimedia Commons

Hippocrates believed women's bodies were different from men’s and therefore their illnesses needed to be dealt with differently.. He remarked that a lot of women died because physicians treated them like men. But he was definitely not championing women's rights. Every illness that afflicted a woman somehow was related to her uterus. Hippocratic physicians wrote extensively about female puberty, menstruation, conception, pregnancy, and menopause. And the cure for women’s ailments was for them to have more sex with men. He wrote, "I assert that a woman who has not borne children becomes ill from her menses more seriously and sooner than one who has borne children." Doctors believed that epileptic fits, visions, loss of breath, pain, and paralysis were all a result of the womb not getting enough sex. How did the womb impact so many different body parts? Doctors in Ancient Greece hypothesized that it wandered around a woman's body bumping into different organs as it went. Herbal remedies were used to send the uterus back to its rightful place. One physician went so far as to describe the wandering womb as "an animal within an animal."

With these views of the female body, it's no wonder that women physicians and midwives took matters into their own hands. Agnodice, for example, disguised herself as a man to study medicine and became a skilled gynaecologist. Rival doctors hoped to supersede her by claiming she was seducing her patients. She was charged with practicing medicine as a female. The practice of cross-dressing for personal or professional pursuits continued until women were allowed to pursue non-traditional occupations.

With these views of the female body, it's no wonder that women physicians and midwives took matters into their own hands. Agnodice, for example, disguised herself as a man to study medicine and became a skilled gynaecologist. Rival doctors hoped to supersede her by claiming she was seducing her patients. She was charged with practicing medicine as a female. The practice of cross-dressing for personal or professional pursuits continued until women were allowed to pursue non-traditional occupations.

Agondice, Wikimedia Commons

Agondice, Wikimedia Commons

Through men’s writing, we gain insights into Greek views of women. Ancient male authors demonstrated their fears of and desires for women through fantastic and mythical tales about monstrous females. One of the most famous pieces of Greek Literature, Homer’s Odyssey is full of these women. At one point, Odysseus must choose between fighting a six-headed, twelve-legged beast-woman or a female sea monster. One historian said female monsters represent “the bedtime stories patriarchy tells itself,” which were prevalent in Ancient Greece. In almost all these tales, the woman had somehow rejected her proper state of nurturing caregiver and met her end at the hands of a heroic male. The Odyssey states women’s role clearly, “Go inside the house, and attend to your work, the loom and distaff, and bid your handmaidens attend to their work also. Talking is men’s business.” But the city states of Greece were different from one another, and literature does not always reflect the realities of life in the past. It can be hard to view Odysseus as a hero when he ordered women to be mutilated and hanged.

Greek mythology did not shy away from the image of a strong, warrior woman. In fact, many Greek histories, epics, and folklore describe an entire race of warrior women known as the Amazons, who were supposed to be the daughters of the god of war, Ares, who had been denied their role as nurturing mothers. Their origins were unknown, described as existing at the far-reaches of known society (best described as being near the Black Sea), in a community of women. Men were allowed into their society only for breeding purposes, though some myths claim Ares was the father of them all. They are described as wearing hoplite armor, using a bow or spear, often on horseback, and being tall and muscular.

Greek mythology did not shy away from the image of a strong, warrior woman. In fact, many Greek histories, epics, and folklore describe an entire race of warrior women known as the Amazons, who were supposed to be the daughters of the god of war, Ares, who had been denied their role as nurturing mothers. Their origins were unknown, described as existing at the far-reaches of known society (best described as being near the Black Sea), in a community of women. Men were allowed into their society only for breeding purposes, though some myths claim Ares was the father of them all. They are described as wearing hoplite armor, using a bow or spear, often on horseback, and being tall and muscular.

Hippolyta in battle, Public Domain

Hippolyta in battle, Public Domain

These warrior women are also said to have stood toe-to-toe with the greatest of Greek warriors according to the mythology of the time. Hercules was challenged to the impossible task of stealing Queen Hippolyte’s girdle. He was ultimately successful, but according to some legends, it required a full army to overtake the Amazons. Hercules is also depicted in pottery fighting the Amazon Andromeda. Future ruler of Athens, Theseus, fell in love with Amazon Antiope and abducted her, only to lose her in battle as the Amazons fought to bring her home. Even the ultimate Greek warrior, Achilles, took on the Amazons. Toward the end of the Trojan War, the Trojans were calling in every favor they had in hopes of holding off the Greek alliance. The Amazons arrived from those far reaches of society and their best warrior, Penthesilea, was sent to duel with Achilles, who had already killed countless Trojan warriors and heroes. There are contradicting versions of the story from there. In one version, Achilles slays her as he did the best men of Troy. In another, he slays her, but falls in love with her as his one true equal just before she dies. In yet another, she kills him, only for the gods to resurrect him and have him defeat her.

Herodotus claims that the Amazons eventually combined with another traditional warrior people, the Scythians, and settled in southern Russia, becoming the Sarmatians.

However, proof that the Amazons existed is speculative at best. Yet, that doesn’t diminish what they can tell us about Greek society’s view of women. Amazons were used by the great to symbolize the horrors of what happens when women abandon their traditional mothering roles. If these women are entirely fictional, they were still purposefully created by the Greeks. The Greeks, who were enamored with perfection in every way, may have created a society of powerful, self-sufficient women who could tussle with the strongest men Greece had to offer. The woman who could challenge Hercules. The woman who could best Achilles.

Herodotus claims that the Amazons eventually combined with another traditional warrior people, the Scythians, and settled in southern Russia, becoming the Sarmatians.

However, proof that the Amazons existed is speculative at best. Yet, that doesn’t diminish what they can tell us about Greek society’s view of women. Amazons were used by the great to symbolize the horrors of what happens when women abandon their traditional mothering roles. If these women are entirely fictional, they were still purposefully created by the Greeks. The Greeks, who were enamored with perfection in every way, may have created a society of powerful, self-sufficient women who could tussle with the strongest men Greece had to offer. The woman who could challenge Hercules. The woman who could best Achilles.

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

Classicist historian Mary Beard explained that in the ancient tradition, female subordination was an important part of being a man and was deeply ingrained in the culture in accounts of the time both in the east and west. She wrote a gendered analysis of Homer’s The Odyssey using Penelope as an example. In the story, she said, “as Homer has it, an integral part of growing up, as a man, is learning to control the public utterance and to silence the female of the species.” Beard went on to explain that entire works were dedicated to the absurdity and inferiority of female power. Examining the stories about the mythical Amazon women, Beard concluded that, “The underlying point was that it was the duty of man to save civilization from the rule of women.” She elegantly showed that oratory and power in the west have always seemed to be a male sphere of influence.

In the real world however, women’s lives were far more restricted. Athens, for example, is viewed as a pillar of democracy and freedom, but Athenian women were basically slaves to the men around them and had no voice in business or politics so democracy for free men. Upper class women were pushed into the domestic sphere, not allowed to speak or even be seen in public. They lived inside their homes, preparing meals and tending to the house. Education for women was rare and only available to wealthy women. They didn’t have property rights or rights as widows. The only events that women were allowed to attend were religious ceremonies. Women were punished severely for adultery and did not have any sexual freedom outside of marriage. They were allowed to be citizens of Athens but what is citizenship without freedom?

In the real world however, women’s lives were far more restricted. Athens, for example, is viewed as a pillar of democracy and freedom, but Athenian women were basically slaves to the men around them and had no voice in business or politics so democracy for free men. Upper class women were pushed into the domestic sphere, not allowed to speak or even be seen in public. They lived inside their homes, preparing meals and tending to the house. Education for women was rare and only available to wealthy women. They didn’t have property rights or rights as widows. The only events that women were allowed to attend were religious ceremonies. Women were punished severely for adultery and did not have any sexual freedom outside of marriage. They were allowed to be citizens of Athens but what is citizenship without freedom?

Spartan Woman, Public Domain

Spartan Woman, Public Domain

Sparta was a world apart. Spartan women participated freely in almost every aspect of their city-state’s social life. Women were trained as athletes because Spartans believed women needed to be physically healthy to survive birth. They were seen outside the home, and girls educated within the home just like the boys, although the boys would go on to private school. Through liaisons with men other than their husbands, Spartan women could also acquire control of more than one home and surrounding lands, and many became wealthy landowners. The purpose of sex within marriage was to create strong, healthy children, but women were allowed to take male lovers to accomplish this same end. Same-sex relationships among men and women were for pleasure and personal fulfillment. These relationships were regarded as natural as long as both parties were of a certain age and had consented. There was a significant number of widows in Sparta who had lost husbands and sons in the wars but never had to worry about survival because they owned the land and knew how to make it profitable. However, we must not forget that Spartan society could only exist because it practiced slavery and was exceedingly brutal in order to maintain order.

Although some Athenian women were merchants, potters, or other professionals, they were routinely secluded from men (possibly even in the home) and had no legal recourse in the courts, limited economic power, and no political voice.

Although some Athenian women were merchants, potters, or other professionals, they were routinely secluded from men (possibly even in the home) and had no legal recourse in the courts, limited economic power, and no political voice.

Diotma, Wikimedia Commons

Diotma, Wikimedia Commons

For the Greeks, women’s lesser position and thus their lack of support for women’s education, was justified by the gods. Hesiod, a Greek thinker, wrote, “Zeus, who thundered on high, made women to be evil to mortal men, with the nature to do evil.” Another male thinker, Semonides, wrote, “the worst plague Zeus ever made, women.” Famous mathematician Pythagoras wrote, “there’s a good principle which created order, light, and man, and an evil principle which created chaos, darkness, and woman.“ Pythagoras of course was educated by Artistoclea, a female scholar, and possibly married to Theano, another female scholar and mathematician, who ran his school after he died. She wrote on mathematics and philosophy, and two anecdotes survive about her. First, someone once commented that she had a beautiful elbow. She responded, “Yes, but not a public one!” Someone else apparently asked her when a woman’s purity returned after sex and she supposedly answered, “With your husband, instantly, with somebody else, never.” Pythagoras’ daughter Dano championed women’s education.

Socrates, who was educated by Diotima, another female scholar, said, “all the pursuits of men are the pursuits of women also, but in all of them a woman is inferior to a man.” Plato’s teacher was Aspasia, another female scholar, but yet he placed women between man and beast. Aristotle wrote that women were, “mutilated males.” Menander stated, “he who teaches a woman letters feeds more poison to the frightful asp.” Perhaps his disdain for women was grounded in fear of their power.

These beliefs were nearly universal among Greek men and society. Women were regarded as inherently vicious, irrational, and untrustworthy, investment in their education was useless, counterproductive, and potentially dangerous. The flagrant disrespect and blindness to the hypocrisy that one could be educated by a woman and doubt her intellect is unbelievable and shows how pervasive misogyny was in Greek society. Women in this climate faced reprehensible misogyny, yet some persisted in their efforts to be educated and find fulfillment beyond the domestic sphere.

But the lives of Greek women were a bit better than those of women in other places. Women’s subjugation was so terrible that in many places they dominated the ranks of the enslaved. A horrified Greek historian wrote on his travels to Egypt, “they were continually without being allowed any rest by night or day. They have not a rag to cover their nakedness, and neither their weakness of age nor women’s infirmities or any plea to excuse them, but they are driven by blows until they drop dead.”

Socrates, who was educated by Diotima, another female scholar, said, “all the pursuits of men are the pursuits of women also, but in all of them a woman is inferior to a man.” Plato’s teacher was Aspasia, another female scholar, but yet he placed women between man and beast. Aristotle wrote that women were, “mutilated males.” Menander stated, “he who teaches a woman letters feeds more poison to the frightful asp.” Perhaps his disdain for women was grounded in fear of their power.

These beliefs were nearly universal among Greek men and society. Women were regarded as inherently vicious, irrational, and untrustworthy, investment in their education was useless, counterproductive, and potentially dangerous. The flagrant disrespect and blindness to the hypocrisy that one could be educated by a woman and doubt her intellect is unbelievable and shows how pervasive misogyny was in Greek society. Women in this climate faced reprehensible misogyny, yet some persisted in their efforts to be educated and find fulfillment beyond the domestic sphere.

But the lives of Greek women were a bit better than those of women in other places. Women’s subjugation was so terrible that in many places they dominated the ranks of the enslaved. A horrified Greek historian wrote on his travels to Egypt, “they were continually without being allowed any rest by night or day. They have not a rag to cover their nakedness, and neither their weakness of age nor women’s infirmities or any plea to excuse them, but they are driven by blows until they drop dead.”

Rhea Silvia, Wikimedia Commons

Rhea Silvia, Wikimedia Commons

Romulus and Remus

There are several stories of Rome’s founding, but perhaps the most popular is the story of Romulus and Remus. This is perhaps one of the most bizarre historical legends of any city's founding. First, the city has two male founders, brothers. Second, the brothers were born to a virgin priestess by the name of Rhea Silvia. According to the Roman writer Livy, she was raped by the god Mars when his disembodied phallus came out of the fire she was tending. She gave birth to twin brothers who were thrown into the nearby river to drown, but they survived and were nursed back to health by a conveniently lactating she-wolf. Interestingly, the Roman word for wolf was also a colloquial term for prostitute, and so it’s possible that, despite what the myth says, the boys were nursed to health by a real lower class woman. A shepherd finds the boys and it is possible that his wife was the prostitute. The boys are competitive and when they grow up, they fight over what parts of the hills that surround Rome belong to each of them. The details here are fuzzy, but what everybody agrees upon is that Romulus killed his brother and became the sole ruler of Rome.

There are several stories of Rome’s founding, but perhaps the most popular is the story of Romulus and Remus. This is perhaps one of the most bizarre historical legends of any city's founding. First, the city has two male founders, brothers. Second, the brothers were born to a virgin priestess by the name of Rhea Silvia. According to the Roman writer Livy, she was raped by the god Mars when his disembodied phallus came out of the fire she was tending. She gave birth to twin brothers who were thrown into the nearby river to drown, but they survived and were nursed back to health by a conveniently lactating she-wolf. Interestingly, the Roman word for wolf was also a colloquial term for prostitute, and so it’s possible that, despite what the myth says, the boys were nursed to health by a real lower class woman. A shepherd finds the boys and it is possible that his wife was the prostitute. The boys are competitive and when they grow up, they fight over what parts of the hills that surround Rome belong to each of them. The details here are fuzzy, but what everybody agrees upon is that Romulus killed his brother and became the sole ruler of Rome.

Rape of Sabine Women, Wikimedia Commons

Rape of Sabine Women, Wikimedia Commons

Many single men flocked to this new founded city. They included runaway slaves, convicted criminals, exiles, and refugees - mostly men. In order for civilizations to survive, they needed women, so Romulus resorted to abduction and rape ( both have the same meaning in Latin). He invited the neighboring villages to have a festival and in the middle of it, the men of Rome abducted the young women from the visiting families and carried them off as wives.

Where was the dividing line between abduction and rape? Livy defends the behavior of the early Roman males as the origin of marriage not adultery. He argued that this behavior was necessary for the future of the realm while others used this story to demonstrate the belligerence of Rome. Romulus’s father was of course Mars, the god of war.

The parents of the Sabine women did not find their abduction and rape innocent or flirtatious. The fathers went to war with Romulus and his men. Hostilities between the men were halted because women ran out onto the battlefield and begged the men in their life to stop fighting. Even in such dire circumstances, the women chose the path of peace.

Where was the dividing line between abduction and rape? Livy defends the behavior of the early Roman males as the origin of marriage not adultery. He argued that this behavior was necessary for the future of the realm while others used this story to demonstrate the belligerence of Rome. Romulus’s father was of course Mars, the god of war.

The parents of the Sabine women did not find their abduction and rape innocent or flirtatious. The fathers went to war with Romulus and his men. Hostilities between the men were halted because women ran out onto the battlefield and begged the men in their life to stop fighting. Even in such dire circumstances, the women chose the path of peace.

Rape of Lucretia, Wikimedia Commons

Rape of Lucretia, Wikimedia Commons

Romulus‘s reign occurred at the beginning of the Regal Period in Roman history. Interestingly, the end of the Regal Period was also marked by the story of rape. A young group of drunken Romans were trying to find a way to pass the time and began a debate about whose wife was best. To settle the debate, Lucius Tarquinius Collatinus suggested they ride home and see whether they had “good” wives. All the wives were found partying in the absence of their husbands, except for Lucius’ wife Lucretia, who was doing exactly what she “should” have been doing.

It was her purity, loyalty, and chastity that made her such a good wife, but that’s not the end of the story. After seeing such an amazing woman, Sextus Tarquinius became obsessed with Lucretia and came back to her house days later and raped her. She was mortified and after telling her husband what happened, she killed herself– because as the Romans saw it, her chastity was more valuable than her life.

Male Roman writers discussed Lucretia for centuries. Some honored her commitment to chastity, embodying the ideal woman. But others wondered was she really innocent? Maybe she asked for it and killed herself because she was guilty. Others wondered if a pure wife was not ideal. These are the same things we hear discussed today about rape victims.

Romans living after the initial period of Kings and during the time of the Republic used the rapes of Rhea Silvia, the Sabine Women, and Lucretia as evidence that he Kings did not serve society, as Rome’s early period started and ended with rape.

Rome is often identified in the public mind with public displays of masculinity by the gladiators, who would fight to the death for the entertainment of the ruler and the masses. We have learned that many gladiators were enslaved men. When the king and the crowd ruled that a fighter was to be killed, it was with the understanding that the owner of the winner of the fight would pay the owner of the slave to be killed. For this reason, many gladiatorial contests ended in a draw.

Two Roman gladiators whose names were Amazon and Archilla are depicted in sculpture whose accompanying plaque declares that they fought to a “noble draw.” On further study we find that these two fighters were women who fought for pure entertainment more than blood lust. Female gladiators, called gladiatrices, represented what we might consider a novelty in Ancient Rome. The women, like their male counterparts, were often slaves, but a few were of a higher class who were attracted to the excitement and danger of fighting before crowds of thousands. They were applauded but not necessarily held in high esteem as middle-class women were expected to play proper and chaste roles as wives and mothers. We know little about these women, except that they were few in number. Amazon and Archilla were exceptions, as their faces and their exploits were memorialized for the future.

It was her purity, loyalty, and chastity that made her such a good wife, but that’s not the end of the story. After seeing such an amazing woman, Sextus Tarquinius became obsessed with Lucretia and came back to her house days later and raped her. She was mortified and after telling her husband what happened, she killed herself– because as the Romans saw it, her chastity was more valuable than her life.

Male Roman writers discussed Lucretia for centuries. Some honored her commitment to chastity, embodying the ideal woman. But others wondered was she really innocent? Maybe she asked for it and killed herself because she was guilty. Others wondered if a pure wife was not ideal. These are the same things we hear discussed today about rape victims.

Romans living after the initial period of Kings and during the time of the Republic used the rapes of Rhea Silvia, the Sabine Women, and Lucretia as evidence that he Kings did not serve society, as Rome’s early period started and ended with rape.

Rome is often identified in the public mind with public displays of masculinity by the gladiators, who would fight to the death for the entertainment of the ruler and the masses. We have learned that many gladiators were enslaved men. When the king and the crowd ruled that a fighter was to be killed, it was with the understanding that the owner of the winner of the fight would pay the owner of the slave to be killed. For this reason, many gladiatorial contests ended in a draw.

Two Roman gladiators whose names were Amazon and Archilla are depicted in sculpture whose accompanying plaque declares that they fought to a “noble draw.” On further study we find that these two fighters were women who fought for pure entertainment more than blood lust. Female gladiators, called gladiatrices, represented what we might consider a novelty in Ancient Rome. The women, like their male counterparts, were often slaves, but a few were of a higher class who were attracted to the excitement and danger of fighting before crowds of thousands. They were applauded but not necessarily held in high esteem as middle-class women were expected to play proper and chaste roles as wives and mothers. We know little about these women, except that they were few in number. Amazon and Archilla were exceptions, as their faces and their exploits were memorialized for the future.

Conclusion

The experience of women in Greece and Rome was not unique. It was replicated around the world. Women, wherever they were, faced all the same challenges men did; war, famine, plague, and drought; but in addition they faced special challenges by being female.

By the end of this era, so much remained in question. Why did these norms develop? Why would women submit to these norms? Why were they so universally accepted? Would women be able to circumvent these norms? Would women’s education and liberation become available, if not in the modern sense.

The experience of women in Greece and Rome was not unique. It was replicated around the world. Women, wherever they were, faced all the same challenges men did; war, famine, plague, and drought; but in addition they faced special challenges by being female.

By the end of this era, so much remained in question. Why did these norms develop? Why would women submit to these norms? Why were they so universally accepted? Would women be able to circumvent these norms? Would women’s education and liberation become available, if not in the modern sense.

Draw your own conclusions

|

Learn how to teach with inquiry.

Many of these lesson plans were sponsored in part by the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources Eastern Region Program, coordinated by Waynesburg University, the History and Social Studies Education Faculty at Plymouth State University, and the Patrons of the Remedial Herstory Project. |

|

OTHER: Women in Pompei

In this inquiry from Women in World History students examine artifacts from Pompei to learn about women's lives in that time. Check it out! |

Lesson Plans from Other Organizations

- This website, Women in World History has primary source based lesson plans on women's history in a whole range of topics. Some are free while others have a cost.

- The Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media has produced recommendations for teaching women's history with primary sources and provided a collection of sources for world history. Check them out!

- The Stanford History Education Group has a number of lesson plans about women in World History.

Women in Myths

Livy: The Rape Of Rhea Silvia By Mars

This story is from the History of Rome, a text dating to around 29 BCE. The story follows Amulius’ attempts to secure his power after overthrowing his brother and the rescue of Romulus and Remus by a she-wolf.

Amulius drove out his brother and ruled in his stead. Adding crime to crime, he destroyed Numitor's male issue; and Rhea Silvia, his brother's daughter, he appointed a Vestal under pretense of honouring her, and by consigning her to perpetual virginity, deprived her of the hope of children. But the Fates were resolved, as I suppose, upon the founding of this great City, and the beginning of the mightiest of empires, next after that of Heaven. The Vestal was ravished, and having given birth to twin sons, named Mars as the father of her doubtful offspring, whether actually so believing, or because it seemed less wrong if a god were the author of her fault. But neither gods nor men protected the mother herself or her babes from the king's cruelty; the priestess he ordered to be manacled and cast into prison, the children to be committed to the river. It happened by singular good fortune that the Tiber having spread beyond its banks into stagnant pools afforded nowhere any access to the regular channel of the river, and the men who brought the twins were led to hope that being infants they might be drowned, no matter how sluggish the stream. So they made shift to discharge the king’s command, by exposing the babes at the nearest point of the overflow, where the fig-tree Ruminalis—formerly, they say, called Romularis—now stands. In those days this was a wild and uninhabited region. The story persists that when the floating basket in which the children had been exposed was left high and dry by the receding water, a she-wolf, coming down out of the surrounding hills to slake her thirst, turned her steps towards the cry of the infants, and with her teats gave them suck so gently, that the keeper of the royal flock found her licking them with her tongue.

Livy, History of Rome, Book 1. Chapter 4. Translation by Foster. B. O (1919) London: Loeb Classical Library.

Questions

Amulius drove out his brother and ruled in his stead. Adding crime to crime, he destroyed Numitor's male issue; and Rhea Silvia, his brother's daughter, he appointed a Vestal under pretense of honouring her, and by consigning her to perpetual virginity, deprived her of the hope of children. But the Fates were resolved, as I suppose, upon the founding of this great City, and the beginning of the mightiest of empires, next after that of Heaven. The Vestal was ravished, and having given birth to twin sons, named Mars as the father of her doubtful offspring, whether actually so believing, or because it seemed less wrong if a god were the author of her fault. But neither gods nor men protected the mother herself or her babes from the king's cruelty; the priestess he ordered to be manacled and cast into prison, the children to be committed to the river. It happened by singular good fortune that the Tiber having spread beyond its banks into stagnant pools afforded nowhere any access to the regular channel of the river, and the men who brought the twins were led to hope that being infants they might be drowned, no matter how sluggish the stream. So they made shift to discharge the king’s command, by exposing the babes at the nearest point of the overflow, where the fig-tree Ruminalis—formerly, they say, called Romularis—now stands. In those days this was a wild and uninhabited region. The story persists that when the floating basket in which the children had been exposed was left high and dry by the receding water, a she-wolf, coming down out of the surrounding hills to slake her thirst, turned her steps towards the cry of the infants, and with her teats gave them suck so gently, that the keeper of the royal flock found her licking them with her tongue.

Livy, History of Rome, Book 1. Chapter 4. Translation by Foster. B. O (1919) London: Loeb Classical Library.

Questions

- How are women depicted in this source?

- How is the rape of "the Vestal" portrayed?

Livy: The Abduction of The Sabine Women

Another story from Livy’s History of Rome, this text details the abduction of the Sabine women. Play close attention to the mention of marriage rites and the way women are described.

When the hour for the games had come, and their eyes and minds were alike riveted on the spectacle before them, the preconcerted signal was given and the Roman youth dashed in all directions to carry off the maidens who were present. The larger part were carried off indiscriminately, but some particularly beautiful girls who had been marked out for the leading patricians were carried to their houses by plebeians told off for the task. One, conspicuous amongst them all for grace and beauty, is reported to have been carried off by a group led by a certain Talassius, and to the many inquiries as to whom she was intended for, the invariable answer was given, ‘For Talassius.’ Hence the use of this word in the marriage rites. Alarm and consternation broke up the games, and the parents of the maidens fled, distracted with grief, uttering bitter reproaches on the violators of the laws of hospitality and appealing to the god to whose solemn games they had come, only to be the victims of impious perfidy.

The abducted maidens were quite as despondent and indignant. Romulus, however, went round in person, and pointed out to them that it was all owing to the pride of their parents in denying right of intermarriage to their neighbours. They would live in honourable wedlock, and share all their property and civil rights, and —dearest of all to human nature-would be the mothers of freemen. He begged them to lay aside their feelings of resentment and give their affections to those whom fortune had made masters of their persons. An injury had often led to reconciliation and love; they would find their husbands all the more affectionate because each would do his utmost, so far as in him lay to make up for the loss of parents and country. These arguments were reinforced by the endearments of their husbands who excused their conduct by pleading the irresistible force of their passion —a plea effective beyond all others in appealing to a woman's nature.

Livy, History of Rome, Book 1. Chapter 9. Translation by Foster. B. O (1919) London: Loeb Classical Library.

Questions

When the hour for the games had come, and their eyes and minds were alike riveted on the spectacle before them, the preconcerted signal was given and the Roman youth dashed in all directions to carry off the maidens who were present. The larger part were carried off indiscriminately, but some particularly beautiful girls who had been marked out for the leading patricians were carried to their houses by plebeians told off for the task. One, conspicuous amongst them all for grace and beauty, is reported to have been carried off by a group led by a certain Talassius, and to the many inquiries as to whom she was intended for, the invariable answer was given, ‘For Talassius.’ Hence the use of this word in the marriage rites. Alarm and consternation broke up the games, and the parents of the maidens fled, distracted with grief, uttering bitter reproaches on the violators of the laws of hospitality and appealing to the god to whose solemn games they had come, only to be the victims of impious perfidy.

The abducted maidens were quite as despondent and indignant. Romulus, however, went round in person, and pointed out to them that it was all owing to the pride of their parents in denying right of intermarriage to their neighbours. They would live in honourable wedlock, and share all their property and civil rights, and —dearest of all to human nature-would be the mothers of freemen. He begged them to lay aside their feelings of resentment and give their affections to those whom fortune had made masters of their persons. An injury had often led to reconciliation and love; they would find their husbands all the more affectionate because each would do his utmost, so far as in him lay to make up for the loss of parents and country. These arguments were reinforced by the endearments of their husbands who excused their conduct by pleading the irresistible force of their passion —a plea effective beyond all others in appealing to a woman's nature.

Livy, History of Rome, Book 1. Chapter 9. Translation by Foster. B. O (1919) London: Loeb Classical Library.

Questions

- How does this document describe the abduction of the Sabine women?

- Why is this description significant?

- What does this tell us about how this founding myth established gender norms?

Livy: The Intervention of The Sabine women

Our final extract from Livy’s History of Rome describes how the Sabine women intervened in the war and called for peace.

They went boldly into the midst of the flying missiles with disheveled hair and rent garments. Running across the space between the two armies they tried to stop any further fighting and calm the excited passions by appealing to their fathers in the one army and their husbands in the other not to bring upon themselves a curse by staining their hands with the blood of a father-in-law or a son-in-law, nor upon their posterity the taint of parricide. "If," they cried, "you are weary of these ties of kindred, these marriage-bonds, then turn your anger upon us; it is we who are the cause of the war, it is we who have wounded and slain our husbands and fathers. Better for us to perish rather than live without one or the other of you, as widows or as orphans."

Livy, History of Rome, Book 1. Chapter 13. Translation by Foster. B. O (1919) London: Loeb Classical Library.

Questions

They went boldly into the midst of the flying missiles with disheveled hair and rent garments. Running across the space between the two armies they tried to stop any further fighting and calm the excited passions by appealing to their fathers in the one army and their husbands in the other not to bring upon themselves a curse by staining their hands with the blood of a father-in-law or a son-in-law, nor upon their posterity the taint of parricide. "If," they cried, "you are weary of these ties of kindred, these marriage-bonds, then turn your anger upon us; it is we who are the cause of the war, it is we who have wounded and slain our husbands and fathers. Better for us to perish rather than live without one or the other of you, as widows or as orphans."

Livy, History of Rome, Book 1. Chapter 13. Translation by Foster. B. O (1919) London: Loeb Classical Library.

Questions

- Why was this speech important?

- How are women portrayed in this document?

Hesiod: Theogony (Pandora)

Greek mythology has a similar origin story for women as the Bible. Pandora in many ways is similar to Eve. In the story, Zeus, the head of the pantheon, creates Pandora, the first mortal woman in Greek mythology. Zeus wanted to punish Prometheus for stealing the fire from the gods and giving it to the humans, so he commands Hephaestus to mold her from clay and gives her gifts from the Olympian gods. One of these gifts was a jar, or box in some renditions, full of all the evils and diseases which exist in the world. After she married Epimetheus, she lifted the lid of this jar and set them all free, thus marking the end of the Golden Age of Humanity.

[545] So said Zeus whose wisdom is everlasting, rebuking him. But wily Prometheus answered him, smiling softly and not forgetting his cunning trick: “Zeus, most glorious and greatest of the eternal gods, take which ever of these portions your heart within you bids.” [550] So he said, thinking trickery. But Zeus, whose wisdom is everlasting, saw and failed not to perceive the trick, and in his heart he thought mischief against mortal men which also was to be fulfilled. With both hands he took up the white fat and was angry at heart, and wrath came to his spirit [555] when he saw the white ox-bones craftily tricked out: and because of this the tribes of men upon earth burn white bones to the deathless gods upon fragrant altars. But Zeus who drives the clouds was greatly vexed and said to him: “Son of Iapetus, clever above all! [560] So, sir, you have not yet forgotten your cunning arts!” So spake Zeus in anger, whose wisdom is everlasting; and from that time he was always mindful of the trick, and would not give the power of unwearying fire to the Melian1race of mortal men who live on the earth. [565] But the noble son of Iapetus outwitted him and stole the far-seen gleam of unwearying fire in a hollow fennel stalk. And Zeus who thunders on high was stung in spirit, and his dear heart was angered when he saw amongst men the far-seen ray of fire. [570] Forthwith he made an evil thing for men as the price of fire; for the very famous Limping God formed of earth the likeness of a shy maiden as the son of Cronos willed. And the goddess bright-eyed Athena girded and clothed her with silvery raiment, and down from her head [575] she spread with her hands an embroidered veil, a wonder to see; and she, Pallas Athena, put about her head lovely garlands, flowers of new-grown herbs. Also she put upon her head a crown of gold which the very famous Limping God made himself [580] and worked with his own hands as a favor to Zeus his father. On it was much curious work, wonderful to see; for of the many creatures which the land and sea rear up, he put most upon it, wonderful things, like living beings with voices: and great beauty shone out from it.

[585] But when he had made the beautiful evil to be the price for the blessing, he brought her out, delighting in the finery which the bright-eyed daughter of a mighty father had given her, to the place where the other gods and men were. And wonder took hold of the deathless gods and mortal men when they saw that which was sheer guile, not to be withstood by men. [590] For from her is the race of women and female kind: of her is the deadly race and tribe of women who live amongst mortal men to their great trouble, no helpmeets in hateful poverty, but only in wealth. And as in thatched hives bees [595] feed the drones whose nature is to do mischief—by day and throughout the day until the sun goes down the bees are busy and lay the white combs, while the drones stay at home in the covered hives and reap the toil of others into their own bellies— [600] even so Zeus who thunders on high made women to be an evil to mortal men, with a nature to do evil. And he gave them a second evil to be the price for the good they had: whoever avoids marriage and the sorrows that women cause, and will not wed, reaches deadly old age [605] without anyone to tend his years, and though he at least has no lack of livelihood while he lives, yet, when he is dead, his kinsfolk divide his possessions amongst them. And as for the man who chooses the lot of marriage and takes a good wife suited to his mind, evil continually contends with good; [610] for whoever happens to have mischievous children, lives always with unceasing grief in his spirit and heart within him; and this evil cannot be healed. So it is not possible to deceive or go beyond the will of Zeus: for not even the son of Iapetus, kindly Prometheus, [615] escaped his heavy anger, but of necessity strong bands confined him, although he knew many a wile.

Hesiod. The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White. Theogony. Cambridge, MA.,Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914.

Questions:

[545] So said Zeus whose wisdom is everlasting, rebuking him. But wily Prometheus answered him, smiling softly and not forgetting his cunning trick: “Zeus, most glorious and greatest of the eternal gods, take which ever of these portions your heart within you bids.” [550] So he said, thinking trickery. But Zeus, whose wisdom is everlasting, saw and failed not to perceive the trick, and in his heart he thought mischief against mortal men which also was to be fulfilled. With both hands he took up the white fat and was angry at heart, and wrath came to his spirit [555] when he saw the white ox-bones craftily tricked out: and because of this the tribes of men upon earth burn white bones to the deathless gods upon fragrant altars. But Zeus who drives the clouds was greatly vexed and said to him: “Son of Iapetus, clever above all! [560] So, sir, you have not yet forgotten your cunning arts!” So spake Zeus in anger, whose wisdom is everlasting; and from that time he was always mindful of the trick, and would not give the power of unwearying fire to the Melian1race of mortal men who live on the earth. [565] But the noble son of Iapetus outwitted him and stole the far-seen gleam of unwearying fire in a hollow fennel stalk. And Zeus who thunders on high was stung in spirit, and his dear heart was angered when he saw amongst men the far-seen ray of fire. [570] Forthwith he made an evil thing for men as the price of fire; for the very famous Limping God formed of earth the likeness of a shy maiden as the son of Cronos willed. And the goddess bright-eyed Athena girded and clothed her with silvery raiment, and down from her head [575] she spread with her hands an embroidered veil, a wonder to see; and she, Pallas Athena, put about her head lovely garlands, flowers of new-grown herbs. Also she put upon her head a crown of gold which the very famous Limping God made himself [580] and worked with his own hands as a favor to Zeus his father. On it was much curious work, wonderful to see; for of the many creatures which the land and sea rear up, he put most upon it, wonderful things, like living beings with voices: and great beauty shone out from it.

[585] But when he had made the beautiful evil to be the price for the blessing, he brought her out, delighting in the finery which the bright-eyed daughter of a mighty father had given her, to the place where the other gods and men were. And wonder took hold of the deathless gods and mortal men when they saw that which was sheer guile, not to be withstood by men. [590] For from her is the race of women and female kind: of her is the deadly race and tribe of women who live amongst mortal men to their great trouble, no helpmeets in hateful poverty, but only in wealth. And as in thatched hives bees [595] feed the drones whose nature is to do mischief—by day and throughout the day until the sun goes down the bees are busy and lay the white combs, while the drones stay at home in the covered hives and reap the toil of others into their own bellies— [600] even so Zeus who thunders on high made women to be an evil to mortal men, with a nature to do evil. And he gave them a second evil to be the price for the good they had: whoever avoids marriage and the sorrows that women cause, and will not wed, reaches deadly old age [605] without anyone to tend his years, and though he at least has no lack of livelihood while he lives, yet, when he is dead, his kinsfolk divide his possessions amongst them. And as for the man who chooses the lot of marriage and takes a good wife suited to his mind, evil continually contends with good; [610] for whoever happens to have mischievous children, lives always with unceasing grief in his spirit and heart within him; and this evil cannot be healed. So it is not possible to deceive or go beyond the will of Zeus: for not even the son of Iapetus, kindly Prometheus, [615] escaped his heavy anger, but of necessity strong bands confined him, although he knew many a wile.

Hesiod. The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White. Theogony. Cambridge, MA.,Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914.

Questions:

- What words are used in Hesiod's piece to describe women?

- Do you think Greek women would have described themselves differently? How so?

- What can Hesiod's work tell us about the lives of women in Ancient Greece?

Women and Healthcare

Hippocrates: Diseases of Women 1

Diseases of Women is a collection of writings by the classical Greek author, Hippocrates, on gynecology. Hippocrates is often regarded as the father of modern medicine. The document below describes the Hippocratic understanding of why women experienced a menstrual bleed and how a woman might avoid menstrual issues.

Since in a woman who has not given birth, the body is not accustomed to being filled up (sc. with blood), but is robust, solider and denser than if she had experienced the lochia, and her uterus has not been dilated, her menstrual flow will be accompanied by more pain, and more troubles will be present: i.e., her menses will be obstructed when she has not given birth. This is so for the reason I first indicated when I contended that a woman is more porous and softer than a man; this being so, a woman’s body draws what is being exhaled from her cavity more quickly and in a greater amount than does a man’s...

Also, because a woman’s flesh is softer, when her body fills up with blood, unless the blood is then discharged from her body, the filling and warming, of their tissues that ensue will provoke pain: for a woman has hotter blood, and for this reason she herself is hotter than a man; if, however, most the blood that was added is subsequently discharged, no pain will arise from it. A man, having solider flesh than a woman, will never overfill with so much blood that, unless some it is discharged each month, he feels pain, and besides he takes in only as much (sc. blood) as is necessary for the nourishment his body, and his body—lacking softness as it does—is never overstretched or heated by fullness as a woman’s is. A great amount this is also due in a man to his exerting himself physically more than a woman, which consumes a part of the exhalation (sc. rising from his food).

Now when, in a woman who has not given birth, the menses fail to appear and cannot find their way out, a disease arises, and this happens if the mouth the uterus is closed or folded over, or some part the vagina has become constricted; for if any these things happens, the menses will be unable to find their way out until the uterus returns to a natural healthy state. This disease generally occurs in whose uterus has a narrow mouth or neck lying further forward into the vagina. For if either these be the case, and the woman does not have intercourse with her husband, and her cavity is more empty than it should be as the result of some disease, the uterus turns aside. For it has no moistness of its own, since the woman is not having intercourse, and there is an open space for it since the cavity is too empty, so that it turns aside because it is drier and lighter than it should be. And sometimes as it turns aside its mouth becomes displaced too far to one side because its neck is lying too far into the vagina. For if the uterus is moist as the result of intercourse and the cavity is not empty, it is not likely to turn aside. This is why the uterus closes as the result of a woman not having intercourse.

Hippocrates, Diseases of Women, Book 1. Translation by Potter. P (2018) London: Loeb Classical Library.

Questions:

- Based off this document, what does Hippocrates believe the relationship between sex and menstruation to be?

- What misogynistic (fearful or hateful) ideas about women can you find in this document?

- What can you infer about Hippocrates perception of women and menstruation?

Soranus of Ephesus: Gynecology

Soranus of Ephesus was a Greek gynecologist who commented on women’s diseases and childbearing. His work also features a 2nd century BCE understanding of menstrual cycles and what is now known as amenorrhea (an absence of menstruation).

Now of those who do not menstruate, some have no ailment and it is physiological for them not to menstruate: either because of their age (as in those too young or on the contrary too old) or because they are pregnant, or mannish, or barren singers and athletes in whom nothing is left over for menstruation, everything being consumed by the exercises or changed into tissue. Others, however, do not menstruate because of a disease of the uterus, or of the rest of the body, or of both: “of the uterus” if the condition of so-called imperforation is present, or callosity, or scirrhus, or inflammation, or a scar has formed on a sore, or a closure of the orifice (from long widowhood among other causes).

Soranus of Ephesus, Gynecology. Translation by Temkin. O (1956) Baltimore: The John Hopkins Press

Questions:

- Based off this document, what does Soranus of Ephesus believe a lack of menstruation to be caused by? Do any of those reasons seem inaccurate? Why or why not?

- What misogynistic (fearful or hateful) ideas about women can you find in this document?

- What can you infer about Soranus of Ephesus's perception of women and menstruation?

Pliny the Elder: Natural History

Pliny the Elder was a Roman author and philosopher most notably known for his work ‘Natural History’. In the following text, Pliny discusses the dangers of menstrual blood.

“But it is not easy that anything should be discovered that is more monstrous than woman’s menstrual fluid. New wine turns sour by coming near it, crops that are touched become barren, grafts whither, seeds of the garden dry up, fruit of trees by which she sits falls off, the brightness of mirrors are dimmed by reflecting her, the edge of iron is dulled, the brightness of ivory, beehives die, bronze and even iron are seized by rust, and the air is seized by an awful smell. Dogs become rabid by tasting it and their bite is infected by an incurable poison. In fact, bitumen, too, which has an otherwise pliable and sticky nature and which floats at certain times of the year on the lake of Judaea, which is called Asphaltites, is not able to be divided up, as it sticks to everything it makes contact with, except a thread which is infected with this slime. Also ants, the tiniest animal, and sensitive to its presence, reject the tasty fruit which it was carrying never to return to it again.”

Coughlin, S. (2022). Aristotle on menstruating women and mirrors — Ancient Medicine. [online] Ancient Medicine. Available at: <https://www.ancientmedicine.org/home/2020/7/26/aristotle-on-menstruating-women-and-mirrors> [Accessed 14 October 2022].

Questions:

“But it is not easy that anything should be discovered that is more monstrous than woman’s menstrual fluid. New wine turns sour by coming near it, crops that are touched become barren, grafts whither, seeds of the garden dry up, fruit of trees by which she sits falls off, the brightness of mirrors are dimmed by reflecting her, the edge of iron is dulled, the brightness of ivory, beehives die, bronze and even iron are seized by rust, and the air is seized by an awful smell. Dogs become rabid by tasting it and their bite is infected by an incurable poison. In fact, bitumen, too, which has an otherwise pliable and sticky nature and which floats at certain times of the year on the lake of Judaea, which is called Asphaltites, is not able to be divided up, as it sticks to everything it makes contact with, except a thread which is infected with this slime. Also ants, the tiniest animal, and sensitive to its presence, reject the tasty fruit which it was carrying never to return to it again.”

Coughlin, S. (2022). Aristotle on menstruating women and mirrors — Ancient Medicine. [online] Ancient Medicine. Available at: <https://www.ancientmedicine.org/home/2020/7/26/aristotle-on-menstruating-women-and-mirrors> [Accessed 14 October 2022].

Questions:

- What does Pliny the Elder believe that menstruation blood does?

- What misogynistic (fearful or hateful) ideas about women can you find in this document?

- What can you infer about Pliny the Elder's perception of women and menstruation?

Sotira: Efficacy of Menstrual Fluid

Although little is known about Sotira, we believe she was a Roman midwife. Her work now only exists in small fragments. The following document discusses the magical properties of menstrual fluid.

“To anoint the soles of the patient's feet with menstrual fluid is the most efficacious cure for tertian and quartan malaria; it is much more effective if it is done by the woman herself without the patient's knowledge. The same remedy also awakens an epileptic.”

Tan. D. A, Haththotuwa. R, Fraser. I. S (2017) ‘Cultural aspects and mythologies surrounding menstruation and abnormal uterine bleeding’ In Best Practice and Research Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. Amsterdam: Elseiver

Questions:

“To anoint the soles of the patient's feet with menstrual fluid is the most efficacious cure for tertian and quartan malaria; it is much more effective if it is done by the woman herself without the patient's knowledge. The same remedy also awakens an epileptic.”

Tan. D. A, Haththotuwa. R, Fraser. I. S (2017) ‘Cultural aspects and mythologies surrounding menstruation and abnormal uterine bleeding’ In Best Practice and Research Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. Amsterdam: Elseiver

Questions:

- What does Sotira believe that menstruation blood does?

- What can you infer about Sotira's perception of women and menstruation?

Unknown: The Papyrus Ebers

The Papyrus ebers are a group of Egyptian medical texts containing herbal formulas and mythical remedies to cure an array of ailments.

‘If you examine a woman having pain in her stomach while hsmn (meaning menstruation) does not come for her, and you find (. . .), then you shall say concerning it: this is a case of obstruction of the blood in her uterus. If you examine a woman who has spent many years while hsmn does not come for her, she habitually spews up something like water, her stomach being like that which is under fire, but it stops when she has spewed up, then you shall say concerning it: this is an accumulation of blood in her uterus because she is bewitched. If you examine a woman having pain in one side of her vulva, you should say concerning it: this means that her hsmn has lost its regularity. When it (i.e., the hsmn) has started, you shall make for her: smashed garlic, cider and sawdust of fir tree. Her pubic region is to be bandaged with it’

This short text is also an extract from the Papyrus Ebers and discusses some medicinal use of menstrual blood.

“sagging breasts should be covered with menstrual blood, and the woman's belly and her thighs should be covered as well”

Frandsen. P. J (2007) ‘The Menstrual “Taboo” in Ancient Egypt’ In Journal of Near Eastern Studies, Vol. 66, No. 2, pp.81-206. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Questions:

‘If you examine a woman having pain in her stomach while hsmn (meaning menstruation) does not come for her, and you find (. . .), then you shall say concerning it: this is a case of obstruction of the blood in her uterus. If you examine a woman who has spent many years while hsmn does not come for her, she habitually spews up something like water, her stomach being like that which is under fire, but it stops when she has spewed up, then you shall say concerning it: this is an accumulation of blood in her uterus because she is bewitched. If you examine a woman having pain in one side of her vulva, you should say concerning it: this means that her hsmn has lost its regularity. When it (i.e., the hsmn) has started, you shall make for her: smashed garlic, cider and sawdust of fir tree. Her pubic region is to be bandaged with it’

This short text is also an extract from the Papyrus Ebers and discusses some medicinal use of menstrual blood.

“sagging breasts should be covered with menstrual blood, and the woman's belly and her thighs should be covered as well”

Frandsen. P. J (2007) ‘The Menstrual “Taboo” in Ancient Egypt’ In Journal of Near Eastern Studies, Vol. 66, No. 2, pp.81-206. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Questions:

- What does this text believe that menstruation blood does?

- What does this text believe about illness related to mensuration?

Hippocrates: Nature of Women

Nature of Women is a text compiled by Hippocratic authors, or students of Hippocrates, on gynecology. Hippocrates is often regarded as the father of modern medicine, which is strange because he wrote in ancient history. In ancient and classical Greece it was believed that the womb could move around freely in the women’s body resulting in medical problems. When we investigate it, this theory is rooted in misogyny with the womb becoming a weakness and procreation often becoming the solution.

Vocabulary:

This is my account of the nature and diseases of women: the most important factor in human affairs is the divine; then the natures of women, and their complexions: for very white women are moister and more subject to fluxes, and dark women are drier and more constricted, whereas wine-colored women have something of both.

The ages of life have the following significance: young women are generally moister and richer in blood, while old women are drier and have less blood: those between the two have something of both. A person who manages these matters correctly must begin from divine factors, and then distinguish the natures of women, their ages, the seasons, and the places where they happen to be; for cold places promote fluxes, while hot ones are drying and constipating.…

If a woman’s uterus moves against her liver, she will suddenly lose her speech, grind her teeth, and take on a livid [furious] coloring—these things befall her suddenly while she is in a healthy state. This happens to unmarried women, especially if they are advanced in age and widowed, but also if they are young and widowed after having had children.

When the case is such, push the uterus down away from the liver, and bind it with a band under the patient’s hypochondria [excessively and unnecessarily worried about being sick]. Open her mouth and pour in very fragrant wine, and hold evil-smelling fumigants under her nostrils and fragrant ones below her uterus. When the woman comes to her senses, have her:

If a woman’s uterus advances and moves outside [the 21st century medical term for this is a “prolapsed uterus,” which can occur after birth]... and irritates her. She suffers these things… after having given birth, she does not sleep with her husband. When the case is such:

If the uterus descends completely out of the genitalia, it hangs like a scrotum, pain occupies the lower abdomen and loins, and when the pain has set in, it (i.e., the uterus) is unwilling to return to its place. This condition comes on when after giving birth a woman strains her uterus, or sleeps with her husband during her lochial flow [bleeding after birth]. When the case is such, cooling compresses must be applied to the genitalia, and the part outside must be cleaned off; boil pomegranate in dark wine, and after washing with this replace the uterus inside, and then inject a mixture of honey and resin.

Hippocrates, Nature of Women, circa 440 and 360 BCE, Translation by Potter. P (Cambridge: Loeb Classical Library, 2012).

Questions

Vocabulary:

- hypochondria: In Hippocratic medicine the "hypochondria" was the part of the abdomen between the ribs and the navel. Hippocrates is saying to bind the patient there to prevent her uterus squeezing up against her liver. The meaning of this word has changed. Modern day it means excessively and unnecessarily worried about being sick.

- fumigate: use chemicals that produce good smelling fumes for cleansing

- genitalia: sexual organs, in women this includes the vulva, vagina, uterus, fillopian tubes, etc.

- lochia flow: the normal bleeding after giving birth, which usually lasts for six weeks

This is my account of the nature and diseases of women: the most important factor in human affairs is the divine; then the natures of women, and their complexions: for very white women are moister and more subject to fluxes, and dark women are drier and more constricted, whereas wine-colored women have something of both.

The ages of life have the following significance: young women are generally moister and richer in blood, while old women are drier and have less blood: those between the two have something of both. A person who manages these matters correctly must begin from divine factors, and then distinguish the natures of women, their ages, the seasons, and the places where they happen to be; for cold places promote fluxes, while hot ones are drying and constipating.…

If a woman’s uterus moves against her liver, she will suddenly lose her speech, grind her teeth, and take on a livid [furious] coloring—these things befall her suddenly while she is in a healthy state. This happens to unmarried women, especially if they are advanced in age and widowed, but also if they are young and widowed after having had children.

When the case is such, push the uterus down away from the liver, and bind it with a band under the patient’s hypochondria [excessively and unnecessarily worried about being sick]. Open her mouth and pour in very fragrant wine, and hold evil-smelling fumigants under her nostrils and fragrant ones below her uterus. When the woman comes to her senses, have her:

- drink a… medication

- and after that ass’s milk

- and then fumigate [use a chemical that produces fumes] her uterus with fragrant [good smelling] substances

- apply a preparation of buprestis

- and on the next day oil of bitter almonds

- leave two days free, and then flush her uterus with fragrant substances

- on the next day apply pennyroyal

- leave one day free and then fumigate with aromatic [good smelling] herbs.

If a woman’s uterus advances and moves outside [the 21st century medical term for this is a “prolapsed uterus,” which can occur after birth]... and irritates her. She suffers these things… after having given birth, she does not sleep with her husband. When the case is such:

- boil myrtle and the sawdust of nettle-tree wood in water

- set this out in the open air, and have the patient pour it as cold as possible onto her genitalia [vulva and vagina]

- also grind this fine and apply it as a plaster.

- Then have her vomit, by drinking lentil water, honey and vinegar, until her uterus is restored to its natural position.

- Positioning her bed with the foot end higher, fumigate beneath her genitalia with evil-smelling substances, and under her nostrils with fragrant ones.

- Have her employ foods that are very mild and cold, drink dilute white wine, and without having a bath sleep with her husband.

If the uterus descends completely out of the genitalia, it hangs like a scrotum, pain occupies the lower abdomen and loins, and when the pain has set in, it (i.e., the uterus) is unwilling to return to its place. This condition comes on when after giving birth a woman strains her uterus, or sleeps with her husband during her lochial flow [bleeding after birth]. When the case is such, cooling compresses must be applied to the genitalia, and the part outside must be cleaned off; boil pomegranate in dark wine, and after washing with this replace the uterus inside, and then inject a mixture of honey and resin.

Hippocrates, Nature of Women, circa 440 and 360 BCE, Translation by Potter. P (Cambridge: Loeb Classical Library, 2012).

Questions

- Based off this text, how is age believed to impact women's health?

- What do you think of some of the Hippocratic author’s prescribed solutions? Why?

- Examine the underlined text. Here the Hippocratic author blames women for having a prolapsed uterus, a rare, serious, and painful medical condition where the uterus falls out after birth. What does he accuse them of doing?

- Why might beliefs placing blame on women for their painful conditions be dangerous for women?

Hippocrates: Diseases of Young Girls

Yet another of Hippocrates works, Diseases of Young Girls focuses on the treatment of young girls after puberty. Again, we see this idea of women as the ‘weaker’ sex and the decision not to marry as the cause of their illnesses.

Vocabulary:

[C]oncerning terrors of the sort that people fear so strongly, that they are beside themselves and seem to see certain hostile spirits, sometimes by night, sometimes by day, and sometimes at both times… as a result of this kind of vision, many have already hanged themselves, more women than men, for female nature is weaker and more troublesome.

Young girls of an age for marriage, who remain unmarried, suffer this especially at the time of the descent of their menses [period]. Before puberty they were healthy. Afterwards blood is gathered into their wombs for evacuation. Yet, when the mouth of the exit is not opened and more blood flows in due to their nourishment and the increase of their body, then the blood, not having a way to flow out, rushes from the quantity towards the heart and the diaphragm. When these parts are filled, the heart becomes numb; then lethargy [laziness] seizes them after the numbness, then after the lethargy, madness seizes them… When these things occur in this way, the young girl is mad from the intensity of the inflammation; she turns murderous from the putrefaction; she feels fears and terrors from the darkness. From the pressure around the heart, these young girls long for nooses. Their spirit, distraught and sorely troubled by the foulness of their blood, attracts bad things, but names something else, even fearful things. They command the young girl to wander about, to cast herself into wells, and to hang herself, as if these actions were preferable and completely useful. Even when without visions, a certain pleasure exists, as a result of which she longs for death, as if something good.

When the female is recovering her senses, the women dedicate to Artemis many other things and especially expensive female clothing at the orders of the goddess's priests. But the women are being deceived. Release from this comes whenever there is no impediment for the flowing out of the blood. I urge, then whenever young girls suffer this kind of malady [sickness] they should as quickly as possible… become pregnant, they become healthy. If not, either at the same moment as puberty, or later, she will be caught by this sickness, if not by another

Hippocrates, Peri Parthenion (Diseases of Young Girls). Translated by Flemming. R, Hanson. A. E. (Leiden:Brill, 1998).

Guiding Questions

Vocabulary:

- menses: period

- womb: uterus

- diaphragm: part of their lungs

- lethargy: laziness

- malady: sickness

[C]oncerning terrors of the sort that people fear so strongly, that they are beside themselves and seem to see certain hostile spirits, sometimes by night, sometimes by day, and sometimes at both times… as a result of this kind of vision, many have already hanged themselves, more women than men, for female nature is weaker and more troublesome.