16. 1300-1500 Renaissance and Ottoman Women Artists and Thinkers

|

The term “Renaissance Man” brings to mind male artists, musicians, and scientists However, no names of women painters or sculptors are as widely or well known by the public, despite their talents and influence on the cultural landscape of Europe. This section seeks to showcase women's artistic contributions to the renaissance from all over the world.

|

Between 1380 and 1580 in Europe, after the plagues and the Mongols had wreaked havoc on Eurasia, societies across the continent experienced a period of rebirth. In Europe, this period has been called a Renaissance. In the Middle East, the period also saw an Islamic Golden Age under the Ottoman Empire. Building on earlier exchanges with the Silk Road, the Islamic world, African cultures, and Europeans turned their attention to their classical past and sought to rebuild it. Women were eager to take part in this endeavor, battling against long-held cultural norms that tried to hold them back.

Europe

The term “Renaissance Man” usually refers to a self-made man or a man who has mastered skills in everything from academic work to swordplay. In truth, the Renaissance Woman was more likely to be a patron of the arts in this period. This was a result of the lack of opportunities for women to get an education or training. Erasmus of Rotterdam, the most famous proponent of new learning in this time, made the prevailing view of women’s education clear when he wrote, “I do not know the reason, but just as a saddle is not suitable for an ox, so learning is unsuitable for a woman.”

Renaissance society preferred women chaste and in their traditional roles, and laws were established to keep women bound to domesticity. Even women’s clothing choices were taxed in a way to limit their sexual expression, “All women and girls, whether married or not, whether betrothed or not, of whatever age, rank, and condition...who wear or wear in future any gold, silver, pearls, precious stones, bells, ribbons of gold or silver, or cloth of silk brocade on their bodies or head for the ornamentation of the bodies...will be required to pay each year...the sum of 50 [coins].”

As society opened to innovation, the new academies and workshops were reserved for men. Wealthy women or the daughters of scholars and artists enjoyed more freedom to learn and to express themselves, but this happened mainly at an individual level. The best-known women of the era were women of influence who used their positions to influence and support the artists of their choosing.

Europe

The term “Renaissance Man” usually refers to a self-made man or a man who has mastered skills in everything from academic work to swordplay. In truth, the Renaissance Woman was more likely to be a patron of the arts in this period. This was a result of the lack of opportunities for women to get an education or training. Erasmus of Rotterdam, the most famous proponent of new learning in this time, made the prevailing view of women’s education clear when he wrote, “I do not know the reason, but just as a saddle is not suitable for an ox, so learning is unsuitable for a woman.”

Renaissance society preferred women chaste and in their traditional roles, and laws were established to keep women bound to domesticity. Even women’s clothing choices were taxed in a way to limit their sexual expression, “All women and girls, whether married or not, whether betrothed or not, of whatever age, rank, and condition...who wear or wear in future any gold, silver, pearls, precious stones, bells, ribbons of gold or silver, or cloth of silk brocade on their bodies or head for the ornamentation of the bodies...will be required to pay each year...the sum of 50 [coins].”

As society opened to innovation, the new academies and workshops were reserved for men. Wealthy women or the daughters of scholars and artists enjoyed more freedom to learn and to express themselves, but this happened mainly at an individual level. The best-known women of the era were women of influence who used their positions to influence and support the artists of their choosing.

Portrait of Lucrezia Borgia, Bridgeman Images

Portrait of Lucrezia Borgia, Bridgeman Images

Lucrezia Borgia

One of the most famous of these is also one of the most controversial. Lucrezia Borgia is sometimes described as the “Mafia Princess” of the Renaissance, and there’s no denying that her corrupt, politically powerful family used her to make the most of opportunities for alliances. Lucrezia’s father was the Catholic Pope, a position that was at that time more king-like than a religious calling. Rodrigo Borgia had seen to his daughter’s education. By the age of 12, she could speak six languages and had been tutored by some of Europe’s leading Humanist scholars. Lucrezia’s father lost no time in arranging her first marriage when she was just 13, but he had that annulled as soon as a better match presented itself. Lucrezia was said to have loved her second husband, but her father attempted to annul that marriage as well, and she resisted. Not long after, her young husband died mysteriously. Fortunately for Lucrezia, her third marriage to Alfonso d’Este, the Duke of Ferrara, lasted. When Lucrezia’s father died in 1503, the political intrigue ended, and she was free to create the courtly society she had always dreamed of. As Duchess of Ferrara, Lucrezia supported poets and musicians, made pious and charitable donations to the community, and even oversaw administrative duties when her husband was away.

Portrait of Catherine de Medici, Art UK

Portrait of Catherine de Medici, Art UK

Catherine de Medici

Catherine de Medici was similarly controversial, but she had a more political power and influence than Lucrezia Borgia.. Like the Borgias, the Medici were no strangers to political intrigue, and Catherine was destined to add to their legacy. She spent part of her youth at the Vatican because her uncle was Pope at that time. As it had been during the days of the Borgia, Rome was a thriving Renaissance hub. In 1533, Catherine was married to the French king, Henry II, in order to solidify an important alliance. Only 14 at the time of her marriage, Catherine spent her time at the French court expanding her education and bonding with the ladies of the palace. Although Henry is said to have ignored her for much of their marriage, Catherine tried to ingratiate herself to the king and his entourage. Once she began to have the crown-prince’s children, her position was more secure. Although Catherine frequently had to compete with Henry’s mistress to get attention at court, she was gradually able to assert her position. When Henry was killed in a jousting tournament in 1559, Catherine was ready to take over.

Women in France could not legally rule in their own names, so Catherine influenced political affairs as the Queen Mother while her sons were still young. One of her biggest concerns was maintaining order between factions divided between Catholic and Protestant forces. Catherine sought a moderate policy towards Protestants, who were considered heretics in France at the time. When her son Francis died at the age of 16, Catherine served as regent because the next prince in line for the throne, Charles, was only 10 years old. She remained in power when Charles inherited at age 14, and they planned a Grand Tour of the kingdom to celebrate a new era. The tour featured a Renaissance festival at every stop during which plays, artistic exhibits, and parades allowed locals to interact with dazzling court culture. A series of tapestries depict the processions, complete with exotic beasts performing stunts. Catherine used the arts and entertainment of the day to celebrate her family, and especially her son, and reassure the people that everything would be fine in spite of religious and political threats. The tour lasted two and a half years and brought the splendors of the Renaissance to every corner of the kingdom. For Catherine, the Renaissance was not only a way to display her wealth and taste but to solidify her family’s political power. The typical Renaissance patron, however, was not necessarily vying for power.

Catherine de Medici was similarly controversial, but she had a more political power and influence than Lucrezia Borgia.. Like the Borgias, the Medici were no strangers to political intrigue, and Catherine was destined to add to their legacy. She spent part of her youth at the Vatican because her uncle was Pope at that time. As it had been during the days of the Borgia, Rome was a thriving Renaissance hub. In 1533, Catherine was married to the French king, Henry II, in order to solidify an important alliance. Only 14 at the time of her marriage, Catherine spent her time at the French court expanding her education and bonding with the ladies of the palace. Although Henry is said to have ignored her for much of their marriage, Catherine tried to ingratiate herself to the king and his entourage. Once she began to have the crown-prince’s children, her position was more secure. Although Catherine frequently had to compete with Henry’s mistress to get attention at court, she was gradually able to assert her position. When Henry was killed in a jousting tournament in 1559, Catherine was ready to take over.

Women in France could not legally rule in their own names, so Catherine influenced political affairs as the Queen Mother while her sons were still young. One of her biggest concerns was maintaining order between factions divided between Catholic and Protestant forces. Catherine sought a moderate policy towards Protestants, who were considered heretics in France at the time. When her son Francis died at the age of 16, Catherine served as regent because the next prince in line for the throne, Charles, was only 10 years old. She remained in power when Charles inherited at age 14, and they planned a Grand Tour of the kingdom to celebrate a new era. The tour featured a Renaissance festival at every stop during which plays, artistic exhibits, and parades allowed locals to interact with dazzling court culture. A series of tapestries depict the processions, complete with exotic beasts performing stunts. Catherine used the arts and entertainment of the day to celebrate her family, and especially her son, and reassure the people that everything would be fine in spite of religious and political threats. The tour lasted two and a half years and brought the splendors of the Renaissance to every corner of the kingdom. For Catherine, the Renaissance was not only a way to display her wealth and taste but to solidify her family’s political power. The typical Renaissance patron, however, was not necessarily vying for power.

Portrait of Isabella d’Este, Wikimedia Commons

Portrait of Isabella d’Este, Wikimedia Commons

Isabella d’Este

Isabella d’Este, the Marchioness of Mantua and Lucrezia Borgia’s sister-in-law, devoted herself to the arts, fashion, and education. Her extensive correspondence with family, artists, leaders, and religious figures leaves a comprehensive record of her far-reaching interests. D’Este supported a wide range of artists, including painters Leonardo da Vinci and Raphael and sculptors such as Michelangelo. Poets, musicians, even architects graced her court at Mantua. By the end of her life, she had founded a school for girls and turned her home into a museum.

Anna Bijns

Not everyone appreciated the role played by patrons of the arts. Dutch poet Anna Bijns lamented how creative work had been diminished by its trendiness in her poem, “’Tis a Waste to Cast Before Swine.” She considered the ability to craft words to be a gift from the Holy Spirit and lamented the fact that so many poets were willing to work on commission for ignorant patrons.

“When Rhetoric I see on sale for money,

Like snow for sun my joy melts away,

And thus I repeat my initial remark:

‘Tis a waste to cast pearls before swine.”

[1528]

Bijns, sometimes referred to as “the Germanic Sappho,” never hesitated to speak her mind. She wrote another controversial poem, “Unyoked is Best! Happy the Woman Without a Man.” In it, she warned maidens not to rush into marriage and to consider all their options before they commit to a husband.

Louise Labé

Other women writers of the day promoted education for girls, even as they faced challenges. The French poet and adventurer Louise Labé went to war dressed as a man before settling down to write sonnets. Llate in her life, she regretted that she had not devoted more time to studying music, philosophy, and history. She wrote to a friend in 1555, “Study differs from other recreations, of which all one can say after enjoying them that one has passed the time. But study gives a more enduring sense of satisfaction. . . for the past delights and serves us more than the present.”

Isabella d’Este, the Marchioness of Mantua and Lucrezia Borgia’s sister-in-law, devoted herself to the arts, fashion, and education. Her extensive correspondence with family, artists, leaders, and religious figures leaves a comprehensive record of her far-reaching interests. D’Este supported a wide range of artists, including painters Leonardo da Vinci and Raphael and sculptors such as Michelangelo. Poets, musicians, even architects graced her court at Mantua. By the end of her life, she had founded a school for girls and turned her home into a museum.

Anna Bijns

Not everyone appreciated the role played by patrons of the arts. Dutch poet Anna Bijns lamented how creative work had been diminished by its trendiness in her poem, “’Tis a Waste to Cast Before Swine.” She considered the ability to craft words to be a gift from the Holy Spirit and lamented the fact that so many poets were willing to work on commission for ignorant patrons.

“When Rhetoric I see on sale for money,

Like snow for sun my joy melts away,

And thus I repeat my initial remark:

‘Tis a waste to cast pearls before swine.”

[1528]

Bijns, sometimes referred to as “the Germanic Sappho,” never hesitated to speak her mind. She wrote another controversial poem, “Unyoked is Best! Happy the Woman Without a Man.” In it, she warned maidens not to rush into marriage and to consider all their options before they commit to a husband.

Louise Labé

Other women writers of the day promoted education for girls, even as they faced challenges. The French poet and adventurer Louise Labé went to war dressed as a man before settling down to write sonnets. Llate in her life, she regretted that she had not devoted more time to studying music, philosophy, and history. She wrote to a friend in 1555, “Study differs from other recreations, of which all one can say after enjoying them that one has passed the time. But study gives a more enduring sense of satisfaction. . . for the past delights and serves us more than the present.”

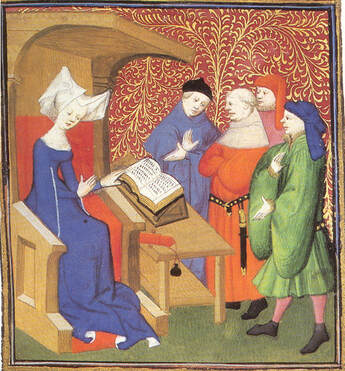

Portrait of Christine de Pizan, Wikimedia Commons

Portrait of Christine de Pizan, Wikimedia Commons

Christine de Pizan

Many of the women writers of the Renaissance expressed hopeful ambitions for women at the time. The way was paved by Christine de Pizan, who is sometimes considered the first feminist. De Pizan was born in Venice in 1364 but grew up in the French court where her father was the king’s astrologer. Although not noble herself, her participation in the French court gave her contacts and support. She was married and then widowed quite young and was able to write for a living while her children grew up. She depended on patrons and tended to write whatever they hired her to write, from love ballads to military strategy handbooks. Once her career was established, Christine de Pizan wrote works designed to elevate women in society. One work, The Book of the City of Ladies, recounted the histories of intellectual women or great leaders and heroes who were women. She wrote this to offset the hateful images of women that were common in the literature of the day. A second book, The Treasure of the City of Ladies’, was written as an advice manual for a French princess. Along with advice for princesses and nobles, Christine de Pizan included sections on advice for women of each rank and role in society. She made it clear that all women were essential and that the expectations of a baroness or an artisan’s wife were just as important as those of a leader. She wrote, “No matter which way I looked at it, I could find no evidence from my own experience to bear out such a negative view of the female nature and habits. Even so… I could scarcely find a moral work by any man you please author which didn't vote some chapter of paragraph two attacking the female sex."

In the visual arts, women made an impact, even though they were usually not permitted to enroll in arts academies. Women artists tended to be the daughters of artists who learned the techniques at home. They were also limited in their subject matter in many cases because it was not appropriate for a woman to work with nude models. Thus, the greatest women artists of the Renaissance got their start doing portraits—portraying their subjects at home was a fitting, domestic theme for a respectable woman.

Many of the women writers of the Renaissance expressed hopeful ambitions for women at the time. The way was paved by Christine de Pizan, who is sometimes considered the first feminist. De Pizan was born in Venice in 1364 but grew up in the French court where her father was the king’s astrologer. Although not noble herself, her participation in the French court gave her contacts and support. She was married and then widowed quite young and was able to write for a living while her children grew up. She depended on patrons and tended to write whatever they hired her to write, from love ballads to military strategy handbooks. Once her career was established, Christine de Pizan wrote works designed to elevate women in society. One work, The Book of the City of Ladies, recounted the histories of intellectual women or great leaders and heroes who were women. She wrote this to offset the hateful images of women that were common in the literature of the day. A second book, The Treasure of the City of Ladies’, was written as an advice manual for a French princess. Along with advice for princesses and nobles, Christine de Pizan included sections on advice for women of each rank and role in society. She made it clear that all women were essential and that the expectations of a baroness or an artisan’s wife were just as important as those of a leader. She wrote, “No matter which way I looked at it, I could find no evidence from my own experience to bear out such a negative view of the female nature and habits. Even so… I could scarcely find a moral work by any man you please author which didn't vote some chapter of paragraph two attacking the female sex."

In the visual arts, women made an impact, even though they were usually not permitted to enroll in arts academies. Women artists tended to be the daughters of artists who learned the techniques at home. They were also limited in their subject matter in many cases because it was not appropriate for a woman to work with nude models. Thus, the greatest women artists of the Renaissance got their start doing portraits—portraying their subjects at home was a fitting, domestic theme for a respectable woman.

Portrait of Sofonisba Anguissola, flickr

Portrait of Sofonisba Anguissola, flickr

Levina Teerling

Levina Teerling (1510-1575) was an artist in Bruges. Like her father, she specialized in miniatures of exquisite detail. After her marriage, Teerling traveled to England, where she attracted the attention of the royal family. Teerling became a court artist under Henry VIII and stayed in that position through the reign of Elizabeth I. Very little of her work survives today. Accounts written during her career, however, were especially enthusiastic about a miniature of the Holy Trinity she had presented to Queen Mary and a portrait and a decorated box she made for Elizabeth.

Sofonisba Anguissola

Sofonisba Anguissola (1532-1625) was not the daughter of an artist but of an Italian nobleman of modest rank. He was impressed with the literature of the day that promoted education for girls, and he made sure his daughters had every opportunity open to them. Sofonisba was the oldest and her talent was obvious, even when she was a teenager. A visitor to their home saw her portrait of her sisters playing chess, one of her most famous paintings, and wrote that the girls looked almost alive on the canvas. After her marriage, Anguissola moved to Spain and continued painting portraits. Word of her skill King Phillip II, and he invited her to join his court. Once there, she expanded her portraits to adopt a formal style appropriate to the high status of her subjects. Sofonisba Anguissola had such a grand reputation across Europe that other women were inspired to emulate her.

Levina Teerling (1510-1575) was an artist in Bruges. Like her father, she specialized in miniatures of exquisite detail. After her marriage, Teerling traveled to England, where she attracted the attention of the royal family. Teerling became a court artist under Henry VIII and stayed in that position through the reign of Elizabeth I. Very little of her work survives today. Accounts written during her career, however, were especially enthusiastic about a miniature of the Holy Trinity she had presented to Queen Mary and a portrait and a decorated box she made for Elizabeth.

Sofonisba Anguissola

Sofonisba Anguissola (1532-1625) was not the daughter of an artist but of an Italian nobleman of modest rank. He was impressed with the literature of the day that promoted education for girls, and he made sure his daughters had every opportunity open to them. Sofonisba was the oldest and her talent was obvious, even when she was a teenager. A visitor to their home saw her portrait of her sisters playing chess, one of her most famous paintings, and wrote that the girls looked almost alive on the canvas. After her marriage, Anguissola moved to Spain and continued painting portraits. Word of her skill King Phillip II, and he invited her to join his court. Once there, she expanded her portraits to adopt a formal style appropriate to the high status of her subjects. Sofonisba Anguissola had such a grand reputation across Europe that other women were inspired to emulate her.

Painting of Judith decapitating Holofernes by Galizia,

Wikimedia Commons

Painting of Judith decapitating Holofernes by Galizia,

Wikimedia Commons

Lavina Fontana

Lavinia Fontana (1552-1614) was the daughter of a painter. She sought to emulate the work of Sofonisba Anguissola, but she also benefited from the unique opportunities available in Bologna, where women were permitted to attend university in certain subjects. Fontana earned a doctorate at the university. She was also unique in that she managed to launch a career outside a court or a convent. Fontana worked privately for commissions, just like the male artists of the day. Fontana did portraits but also took on large projects with mythical or religious themes. She was very popular, and the noble women of Bologna competed for her attention. Many patrons of high status employed her, including one who would go on to become Pope. Lavinia Fontana was so successful that her commissions served as her dowry in marriage. Her husband worked as her agent and assistant. With the expansion of opportunities and the growing success of female artists, the next generation took the next big steps towards Renaissance greatness.

Fede Galizia

Fede Galizia (1577-1630) was the daughter of a painter, but he did not intend to train her until he learned of Sofonisba Anguissola’s career. Galizia is best known for her still lifes, and she was considered a pioneer for her delicate touch in that art form. She also painted portraits and religious works. Like Fontana, worked on commission. Galizia was even hired to create altar pieces for a church in Milan. One of the most interesting things about Galizia is that she was first in a series of women artists to focus on the portrayal of heroic women in the Bible. Judith decapitating Holofernes was a favorite theme, and Galizia, like the women who emulated her, depicted subjects like Judith as strong and dignified, with none of the suggested sexualization that male artists tended to use.

Lavinia Fontana (1552-1614) was the daughter of a painter. She sought to emulate the work of Sofonisba Anguissola, but she also benefited from the unique opportunities available in Bologna, where women were permitted to attend university in certain subjects. Fontana earned a doctorate at the university. She was also unique in that she managed to launch a career outside a court or a convent. Fontana worked privately for commissions, just like the male artists of the day. Fontana did portraits but also took on large projects with mythical or religious themes. She was very popular, and the noble women of Bologna competed for her attention. Many patrons of high status employed her, including one who would go on to become Pope. Lavinia Fontana was so successful that her commissions served as her dowry in marriage. Her husband worked as her agent and assistant. With the expansion of opportunities and the growing success of female artists, the next generation took the next big steps towards Renaissance greatness.

Fede Galizia

Fede Galizia (1577-1630) was the daughter of a painter, but he did not intend to train her until he learned of Sofonisba Anguissola’s career. Galizia is best known for her still lifes, and she was considered a pioneer for her delicate touch in that art form. She also painted portraits and religious works. Like Fontana, worked on commission. Galizia was even hired to create altar pieces for a church in Milan. One of the most interesting things about Galizia is that she was first in a series of women artists to focus on the portrayal of heroic women in the Bible. Judith decapitating Holofernes was a favorite theme, and Galizia, like the women who emulated her, depicted subjects like Judith as strong and dignified, with none of the suggested sexualization that male artists tended to use.

“The Allegory of Inclination”, Wikimedia commons

“The Allegory of Inclination”, Wikimedia commons

Artemisia Gentileschi

Artemisia Gentileschi (1593-1652) was one of most famous artists of her age. She was painting professionally in Venice by the time she was 15. She was raised by her father, who was also a painter. Gentileschi became a member of the Academy of Arts and Drawing in Florence. She worked on commissions and briefly served as a court painter, especially for the Medici family. Some of the greatest houses in Italy, such as the family of Michaelangelo, hired her to create a ceiling panel. Gentileschi also corresponded with great thinkers across Italy, including Galileo Galilei, who may have been the inspiration for the work she did on that ceiling. It features a nude holding a compass, and is entitled “The Allegory of Inclination.” Artemisia, created a series of paintings of the biblical Judith, as well as other strong women such as Esther, Mary Magdalene, Cleopatra, and Saint Cecilia.

Elisabeth Sirani

Elisabetta Sirani (1638-1665) had an amazing career in Bologna, but her life was cut short by a mysterious illness when she was only 27. Her father was a painter and an art dealer who took over the school of his own master and trained Elisabetta himself at first. As Bologna offered opportunities for women, she was able to move on to other academies and eventually opened an art academy for girls. Sirani did not hesitate to tackle grand historical or religious subjects in her paintings. More than 200 works of hers survive, and she signed just about every piece. Sirani also painted a few versions of Judith and a variety of saints, but she might be best known for Timoclea killing Captain Alexander the Great. According to the ancient historian Plutarch, Timoclea was a noble woman in Thebes who was assaulted by one of Alexander’s officers. In revenge, she pretended to lead him to her hidden wealth at the bottom of a well. When he stooped to look in, Timoclea pushed him to his death. Though other artists did survive assaults at the hands of male artists, Sirani seems to have simply been making a statement about strong women.

Artemisia Gentileschi (1593-1652) was one of most famous artists of her age. She was painting professionally in Venice by the time she was 15. She was raised by her father, who was also a painter. Gentileschi became a member of the Academy of Arts and Drawing in Florence. She worked on commissions and briefly served as a court painter, especially for the Medici family. Some of the greatest houses in Italy, such as the family of Michaelangelo, hired her to create a ceiling panel. Gentileschi also corresponded with great thinkers across Italy, including Galileo Galilei, who may have been the inspiration for the work she did on that ceiling. It features a nude holding a compass, and is entitled “The Allegory of Inclination.” Artemisia, created a series of paintings of the biblical Judith, as well as other strong women such as Esther, Mary Magdalene, Cleopatra, and Saint Cecilia.

Elisabeth Sirani

Elisabetta Sirani (1638-1665) had an amazing career in Bologna, but her life was cut short by a mysterious illness when she was only 27. Her father was a painter and an art dealer who took over the school of his own master and trained Elisabetta himself at first. As Bologna offered opportunities for women, she was able to move on to other academies and eventually opened an art academy for girls. Sirani did not hesitate to tackle grand historical or religious subjects in her paintings. More than 200 works of hers survive, and she signed just about every piece. Sirani also painted a few versions of Judith and a variety of saints, but she might be best known for Timoclea killing Captain Alexander the Great. According to the ancient historian Plutarch, Timoclea was a noble woman in Thebes who was assaulted by one of Alexander’s officers. In revenge, she pretended to lead him to her hidden wealth at the bottom of a well. When he stooped to look in, Timoclea pushed him to his death. Though other artists did survive assaults at the hands of male artists, Sirani seems to have simply been making a statement about strong women.

|

Sirani was, by all accounts, a dazzling artist. Some observers said she painted with such speed and perfection it was almost like she was “laughing” instead of working. Male critics who refused to believe a young woman could have produced such amazing work challenged her to paint a prince’s portrait in front of an audience to prove it was her own skill. She did so. She had such a loyal following that, upon her sudden death, contributions poured in to cover an elaborate funeral. Musicians composed works for the event and poets outdid one another with their heartfelt eulogies. But the experience and rights of European women was still emerging. Elsewhere in the Muslim world, women’s rights and freedoms looked considerably different.

|

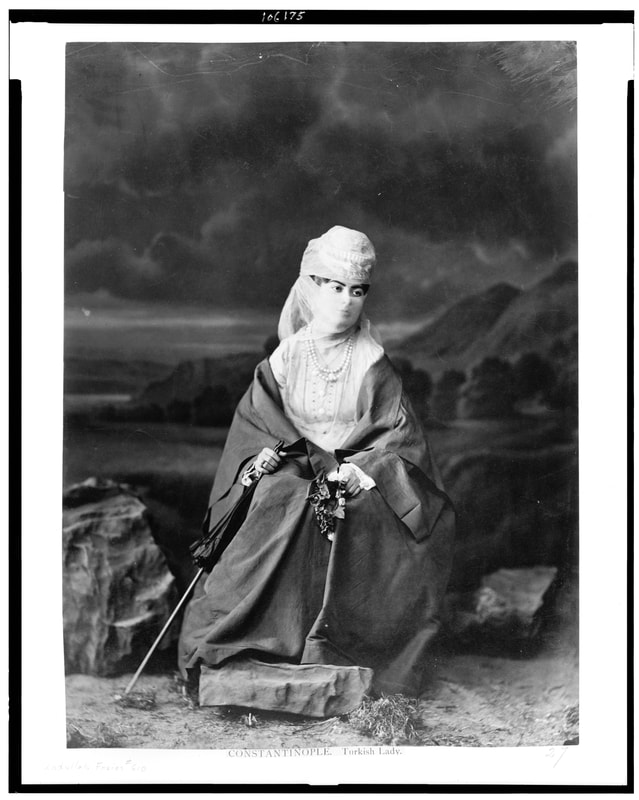

Harem woman, Wikimedia commons

Harem woman, Wikimedia commons

Ottomans

After the Mongols sacked Baghdad, destroying the riches of the Islamic Empire, the Muslim world was in disarray. Eventually, the Ottoman Empire emerged out of Turkey in the 1300s. There, the role and position of women shifted from the more public roles they had played in Turkish tribes to the more segregated lives they lived in a thriving empire. At this point, Islam was well-established.

The status of women in Islam had certainly declined. One Ottoman writer explained, “The responsible officials [have] the great desire to restrain the barbarous and irrepressible bestiality of women who...with that reprobate [morally damned] and diabolical nature, force their men, with their honeyed poison, to submit to them.”

When the Ottomans successfully conquered Constantinople in 1453, the empire was poised to control the Mediterranean economy. The Ottoman patriarchy set about doing what all major empires had done: telling women what they could and could not do. Women were socially removed from society, a custom called “cloistering.” This was a social convention more than any dictate in Islamic law.

One of the most enduring images of Ottoman women's segregation is the harem. The exotic and eroticized image of the harem is a Western obsession that overlooks the much more complex functioning of this important institution.

The harem represented a contrast between European and Ottoman societies. Ottoman harems were much different from Chinese harems, and both were eroticized in the Western imagination. In Ottoman society, the harem served to exclude women, but also to grant them freedom of expression. One contemporary observer wrote:

"the women dress themselves very richly in silk. They wear cloaks down to the ground, lined just like those of the men. They wear closed-up boots but fitting tighter on the ankle and more arched than those of the men...They are fond of black hair, and if any women by nature does not possess it, she accuses it by artificial means...They decorate their hair with small bands of ribbon and leave them spread over their shoulders and falling over their dress. Covering their hair they have a colored strip of thin silk...On the head they also have a small round cap, neat and close fitting, embroidered with satin, damask, or silk and colored.”

After the Mongols sacked Baghdad, destroying the riches of the Islamic Empire, the Muslim world was in disarray. Eventually, the Ottoman Empire emerged out of Turkey in the 1300s. There, the role and position of women shifted from the more public roles they had played in Turkish tribes to the more segregated lives they lived in a thriving empire. At this point, Islam was well-established.

The status of women in Islam had certainly declined. One Ottoman writer explained, “The responsible officials [have] the great desire to restrain the barbarous and irrepressible bestiality of women who...with that reprobate [morally damned] and diabolical nature, force their men, with their honeyed poison, to submit to them.”

When the Ottomans successfully conquered Constantinople in 1453, the empire was poised to control the Mediterranean economy. The Ottoman patriarchy set about doing what all major empires had done: telling women what they could and could not do. Women were socially removed from society, a custom called “cloistering.” This was a social convention more than any dictate in Islamic law.

One of the most enduring images of Ottoman women's segregation is the harem. The exotic and eroticized image of the harem is a Western obsession that overlooks the much more complex functioning of this important institution.

The harem represented a contrast between European and Ottoman societies. Ottoman harems were much different from Chinese harems, and both were eroticized in the Western imagination. In Ottoman society, the harem served to exclude women, but also to grant them freedom of expression. One contemporary observer wrote:

"the women dress themselves very richly in silk. They wear cloaks down to the ground, lined just like those of the men. They wear closed-up boots but fitting tighter on the ankle and more arched than those of the men...They are fond of black hair, and if any women by nature does not possess it, she accuses it by artificial means...They decorate their hair with small bands of ribbon and leave them spread over their shoulders and falling over their dress. Covering their hair they have a colored strip of thin silk...On the head they also have a small round cap, neat and close fitting, embroidered with satin, damask, or silk and colored.”

Ottoman Women, Wikimedia Commons

Ottoman Women, Wikimedia Commons

Mothers and other relatives of sultans living cloistered lives became powerful and influential. Women of the harem used their wealth to support important projects and charities such as schools, hospitals, caravansaries, baths, fountains, soup kitchens, hostels, and mosques. Some estimate that about a quarter of Ottoman charitable foundations were started by

royal women! This shows that women who owned land in Ottoman society were able to manage their wealth reasonably easily.

Women of all social levels had the right to manage their property without patriarchal interference. They used the courts to defend their financial control, and it seems in most instances judges upheld these rights. Women were borrowers and lenders and had their own private businesses. During festivals, women were allowed to appear in public. But old concerns about women’s public morality created a backlash that forced them away again.

Lower class women lived different lives from their wealthy peers. They intermingled with men because they ran businesses, performed domestic errands, and did other work that necessitated such conduct. Women monopolized work in textile production, winding silk and spinning cotton. But women also sold food, were traders, operated public baths, brokered slave trades, and were entertainers. In the rural areas, women worked in agriculture and animal husbandry.

Ottoman law created a marriage system that favored men in numerous ways. Muslim men could marry non-Muslim women, but women could not marry outside the faith.. Men were permitted absolute authority over as many of four spouses, but women were not. Men could divorce with relative ease, but women could not. But outside of the law, marriages were a bit more egalitarian than meets the eye. Marriages were arranged, but women obtained prenuptial agreements and had the right to refuse a match. Even though the law allowed up to four wives, in the Ottoman empire, 95 percent of husbands had only one wife. Muslim women had, in reality, a much easier time getting divorced from neglectful and abusive husbands than their non-Muslim peers within the empire. So much so, that some women would convert to Islam in order to get divorced.

Ottoman women's status was probably equal to that of European women. Lady Elizabeth Craven traveled through Crimea to Constantinople, and observed, “I think I never saw a country where women may enjoy so much freedom from all reproach, as in Turkey…. The Turks in their conduct towards our sex are an example to all other nations.”

The Renaissance was a rebirth of art and culture, but it was in many ways a rebirth of the patriarchy. Women did not see widespread access to education or a major change in their status.

How many more women would we know about today if only they had had the chance to try? How would women find greater access to education and other means of self improvement? And what would bring about that shift?

royal women! This shows that women who owned land in Ottoman society were able to manage their wealth reasonably easily.

Women of all social levels had the right to manage their property without patriarchal interference. They used the courts to defend their financial control, and it seems in most instances judges upheld these rights. Women were borrowers and lenders and had their own private businesses. During festivals, women were allowed to appear in public. But old concerns about women’s public morality created a backlash that forced them away again.

Lower class women lived different lives from their wealthy peers. They intermingled with men because they ran businesses, performed domestic errands, and did other work that necessitated such conduct. Women monopolized work in textile production, winding silk and spinning cotton. But women also sold food, were traders, operated public baths, brokered slave trades, and were entertainers. In the rural areas, women worked in agriculture and animal husbandry.

Ottoman law created a marriage system that favored men in numerous ways. Muslim men could marry non-Muslim women, but women could not marry outside the faith.. Men were permitted absolute authority over as many of four spouses, but women were not. Men could divorce with relative ease, but women could not. But outside of the law, marriages were a bit more egalitarian than meets the eye. Marriages were arranged, but women obtained prenuptial agreements and had the right to refuse a match. Even though the law allowed up to four wives, in the Ottoman empire, 95 percent of husbands had only one wife. Muslim women had, in reality, a much easier time getting divorced from neglectful and abusive husbands than their non-Muslim peers within the empire. So much so, that some women would convert to Islam in order to get divorced.

Ottoman women's status was probably equal to that of European women. Lady Elizabeth Craven traveled through Crimea to Constantinople, and observed, “I think I never saw a country where women may enjoy so much freedom from all reproach, as in Turkey…. The Turks in their conduct towards our sex are an example to all other nations.”

The Renaissance was a rebirth of art and culture, but it was in many ways a rebirth of the patriarchy. Women did not see widespread access to education or a major change in their status.

How many more women would we know about today if only they had had the chance to try? How would women find greater access to education and other means of self improvement? And what would bring about that shift?

Draw your own conclusions

|

Learn how to teach with inquiry.

Many of these lesson plans were sponsored in part by the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources Eastern Region Program, coordinated by Waynesburg University, the History and Social Studies Education Faculty at Plymouth State University, and the Patrons of the Remedial Herstory Project. |

|

OTHER: Renaissance and Ottomans

In this inquiry from Women in World History students examine primary sources from the lives of women in Renaissance Europe. Check it out! In this inquiry from Women in World History, read first person accounts and take the perspective of women to understand issues such as the harem, clothing, and use of slaves in the Ottoman world. Check it out! |

Lesson Plans from Other Organizations

- This website, Women in World History has primary source based lesson plans on women's history in a whole range of topics. Some are free while others have a cost.

- The Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media has produced recommendations for teaching women's history with primary sources and provided a collection of sources for world history. Check them out!

- The Stanford History Education Group has a number of lesson plans about women in World History.

Unknown: Florentine Document

All women and girls, whether married or not, whether betrothed or not, of whatever age, rank, and condition...who wear - or wear in future - any gold, silver, pearls, precious stones, bells, ribbons of gold or silver, or cloth of silk brocade on their bodies or head for the ornamentation of the bodies...will be required to pay each year...the sum of 50 [coins] ...exceptions to this prohibition are that every married woman may wear on her hand or hands as many as two rings and every married woman or girl who is betrothed may wear a silver belt which does not exceed fourteen ounces in weight.

Florentine Brucker, Gene. The Society of Renaissance Florence Harper & Row: New York, 1971, 46-47.

Questions:

Florentine Brucker, Gene. The Society of Renaissance Florence Harper & Row: New York, 1971, 46-47.

Questions:

- Summarize this source?

- What is the difference for married women and single women?

Unknown: Regulation To Restrain Female Ornaments And Dress

After diligent examination and mature deliberation, the responsible officials [have] the great desire to restrain the barbarous and irrepressible bestiality of women who...with that reprobate [morally damned] and diabolical nature, force their men, with their honeyed poison, to submit to them. But it is not in accordance with nature for women to be burdened with so many expensive ornaments, and on account of these unbearable expenses, men are avoiding matrimony.

"Regulation to restrain female ornaments and dress, [1413]." Ibid.

Questions:

"Regulation to restrain female ornaments and dress, [1413]." Ibid.

Questions:

- Is this source from an Ottoman or Florentine?

Unkown: From The Deliberations Of The Officials Of The Curfew And The Convents

The trumpet of the lord and the voice of the highest shall call out on the day of judgment: "You who are worthy; come; and you who are unworthy, o'accursed ones, go into the eternal fire.”...Natural law has ordained that the human species should multiply and that man and woman be joined together by matrimony...nothing is more displeasing to God than its violation. There are many who have failed. As a result, divine providence is disturbed and has afflicted the world with evils of wars, disorders, epidemics and other calamities and troubles. A heavy penalty must be meted out to delinquents, especially those women who continue to sin.

Ottoman "from the deliberations of the officials of the curfew and the convents." Ibid.

Questions:

Ottoman "from the deliberations of the officials of the curfew and the convents." Ibid.

Questions:

- Is this source from an Ottoman or a Florentine?

Zara Da Bassano: The Harem

...the women dress themselves very richly in silk. They wear cloaks down to the ground, lined just like those of the men. They wear closed-up boots but fitting tighter on the ankle and more arched than those of the men...They are fond of black hair, and if any women by nature does not posses it, she accuses it by artificial means...They decorate their hair with small bands of ribbon and leave them spread over their shoulders and falling over their dress. Covering their hair they have a colored strip of thin silk...On the head they also have a small round cap, neat and close fitting, embroidered with satin, damask, or silk and colored.

Bassano da Zara, quoted in N. M. Penzer. The Harem: an account of the institution as it existed in the Palace of the Turkish sultans with a history of the grand Seraglio from its foundation to modern times. Spring Books: London, 1936, p. 163- 165.

Questions:

Bassano da Zara, quoted in N. M. Penzer. The Harem: an account of the institution as it existed in the Palace of the Turkish sultans with a history of the grand Seraglio from its foundation to modern times. Spring Books: London, 1936, p. 163- 165.

Questions:

- Summarize this source?

Francis Petrarch: Letters Of Old Age

[To her husband] she replied, “I have said and will repeat: I can not want anything except what you want, and in these children is nothing of mine but the birth pangs. You are my lord and theirs, use your right over your property, and do no seek my consent. From the moment I entered your house, as I laid aside my clothes, I laid aside my wishes and feelings, and put on yours; therefore, in anything, whatever you want, I too want.”

Francis Petrarch, Letters of Old Age [Rerum senilium Libri, I- VIII], Vol. II, translated by Aldo S. Bernardo, et al. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, 1992, p. 663.

Questions:

Francis Petrarch, Letters of Old Age [Rerum senilium Libri, I- VIII], Vol. II, translated by Aldo S. Bernardo, et al. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, 1992, p. 663.

Questions:

- Is this source from an Ottoman or a Florentine?

Madeline: Excerpt

Night and day immoral individuals openly consume intoxicating beverages to an excessive degree and commit all kinds of transgressions against women.

Imperial order 1585, Ankara, cited in Madeline c. Zilfi, Ed. Women in the Ottoman Empire: Middle Eastern. Women in the Early Modern Era. Leiden: Brill, 1997, p. 185.

Questions:

Imperial order 1585, Ankara, cited in Madeline c. Zilfi, Ed. Women in the Ottoman Empire: Middle Eastern. Women in the Early Modern Era. Leiden: Brill, 1997, p. 185.

Questions:

- Summarize this source.

Alessandro Strozzi: Quote

A husband who is promised a dowry by his brother-in-law that is not paid can send his wife back to her brother’s house and even deny her basic necessities.

Alessandro Strozzi, Florentine jurist, quoted in William J. Connell, Ed. Society and Individual in Renaissance Florence. University of California Press: Berkley, 2002, p. 99-100.

Questions:

Alessandro Strozzi, Florentine jurist, quoted in William J. Connell, Ed. Society and Individual in Renaissance Florence. University of California Press: Berkley, 2002, p. 99-100.

Questions:

- Is this source from an Ottoman or a Florentine?

Ebu Suud: Quote

Rights must not be allowed to languish. If she [a wife] does not come [to the court] in person, the legal authority must obtain a proxy for her by ordering that one be appointed.

Ebu Suud, 16th century, quoted in Lesley Pierne, Morality Tales: Law and Gender in the Ottoman Court of Aintab. University of California Press: Berkley, 2003, p. 153.

Questions:

Ebu Suud, 16th century, quoted in Lesley Pierne, Morality Tales: Law and Gender in the Ottoman Court of Aintab. University of California Press: Berkley, 2003, p. 153.

Questions:

- Summarize this source.

Giovanni Domenici: Quote

Now as a bride receiving the rich casket from that husband whom she never saw, she feels much beloved when she is so richly rewarded and she creates a noble image of him who so nobly sent, and not seeing, his love.

Giovanni Domenici, Florentine friar, quoted in Connell, op cit., p. 95.

Questions:

Giovanni Domenici, Florentine friar, quoted in Connell, op cit., p. 95.

Questions:

- What is this source describing?

lucienne Thys-Senocak: Excerpt

To achieve her desire of acquiring merit in God’s sight...and in genuine and sincere dedication devoid of all hypocrisy and deceit, only with the purest of intentions, she ordered [the construction of] a great many magnificent edifices of charity.

Lucienne Thys-Senocak, Ottoman Women Builders: The Architectural Patronage of Hadice Turban Sultan, Ashgate 2006, p. 85.

Questions:

Lucienne Thys-Senocak, Ottoman Women Builders: The Architectural Patronage of Hadice Turban Sultan, Ashgate 2006, p. 85.

Questions:

- Is this source Ottoman or Florentine?

Kosem Sultan: Inscription

She built a school...for which let God grant her fame and benevolence. Oh God, take her into the eternal Paradise.

Inscription, referring to Kosem Sultan. Ibid, p. 89

Questions:

Inscription, referring to Kosem Sultan. Ibid, p. 89

Questions:

- Summarize this source?

- Why might this be significant?

Antonio Roselli: Quote

In those matters no one can rule the wills of wives except their husbands to whom God wished females to be subordinate.

Antonio Roselli of Arezzo, University of Florence, quoted in Connell, op cit, p. 93.

Questions:

Antonio Roselli of Arezzo, University of Florence, quoted in Connell, op cit, p. 93.

Questions:

- How does this affect women?

Baldassare Castiglione: Excerpt

Women are imperfect creatures, and consequently have less dignity than men, and that they are not capable of the virtues that men are capable of... Very learned men have written that, since nature always intends and plans to make things most perfect, she would constantly bring forth men if she could; and that when a woman is born, it is a defect or mistake of nature, and contrary to what she would wish to do...Thus, a woman can be said to be a creature produced by chance and accident. Nevertheless, since these defects in women are the fault of nature that made them so, we ought not on that account to despise them, or fail to show them the respect which is their due. But to esteem them to be more than what they are seems a manifest error.

Castiglione, Baldassare. The Book of the Courtier, George Bull, translator. Penguin: Baltimore, 1967.

Questions:

Castiglione, Baldassare. The Book of the Courtier, George Bull, translator. Penguin: Baltimore, 1967.

Questions:

- Summarize this source.

Théodore Godefroy: Manuscript

The following is an extract from ‘Le Ceremonial Français... a manuscript for Théodore Godefroy. Godefroy was a 16th century French scholar. In the document, Charles IX highlights Catherine’s political status. Charles removed his hat as he approached his mother as a sign of respect that was usually only accorded to kings.

[T]he queen [mother] rose and went toward the king on his royal seat to declare that she

remitted into his majesty's hands the administration of his realm which had been given by the

estates assembled at Orleans. And as a sign of this, the said lady went toward the said lord and

he descended three or four steps from his throne to come before her with his hat in his hand.

And he made a great reverence to this woman and kissed her, and the king said to her that she

would govern and command more than ever.

Crawford. K (2000) ‘Catherine de Medicis and the Performance of Political Motherhood’ In The Sixteenth Century Journal, Vol. 31, No. 2. pp.643-673. Kirksville: Truman State University.

Questions:

[T]he queen [mother] rose and went toward the king on his royal seat to declare that she

remitted into his majesty's hands the administration of his realm which had been given by the

estates assembled at Orleans. And as a sign of this, the said lady went toward the said lord and

he descended three or four steps from his throne to come before her with his hat in his hand.

And he made a great reverence to this woman and kissed her, and the king said to her that she

would govern and command more than ever.

Crawford. K (2000) ‘Catherine de Medicis and the Performance of Political Motherhood’ In The Sixteenth Century Journal, Vol. 31, No. 2. pp.643-673. Kirksville: Truman State University.

Questions:

- What kind of source is this?

- When was it written?

- What does this document tell us about Catherine’s power in the court and her relationship with Charles IX?

Michel de L’Hospital: Oeuvres Completes

Michel de L’Hospital was a catholic lawyer who worked for the French government in the 16th century. Catherine de Medici named him chancellor in 1560 hoping he might reconcile the conflict between Catholics and Protestants. In this short extract he refers to the reign of her second son, Charles IX, and emphasizes Catherine’s special status and power.

He is in his majority, and I do not hesitate to say in the presence of his majesty ... that he

wants to be regarded as an adult in all things and everywhere, and in every place as having

strength, except towards the queen his mother, to whom he reserves the power to command.

Michel de L’Hospital, Oeuvres Completes, 16th century. Translation by Dufey. P. J. S (1824) Paris.

Questions:

He is in his majority, and I do not hesitate to say in the presence of his majesty ... that he

wants to be regarded as an adult in all things and everywhere, and in every place as having

strength, except towards the queen his mother, to whom he reserves the power to command.

Michel de L’Hospital, Oeuvres Completes, 16th century. Translation by Dufey. P. J. S (1824) Paris.

Questions:

- What kind of source is this?

- When was it written?

- Why might the young King reserve power for his mother?

Pierre de l’Estoile: Journal

The following extract is a verse transcribed in the 1575 journal of Pierre de l’Estoile. The verses refer to Catherine’s extreme passion for power. Note the violent language used.

You marvel how a woman, after annulling the Salic law, boldly presses Gallic necks to her authority. Alas! She unmans cocks, tearing off their crests and testicles; a virago holds sway over the French. An unbridled woman dines on [men], and as she devours this food, she smacks her lips and says, “Thus I castrate Gallic courage, thus I unman the French, thus I subdue them!”

Murphy. S (1992) ‘Catherine, Cybele and Ronsard’s Witnesses’ In Long. K (Ed) High Anxiety: Masculinity in Crisis in Early Modern France. Kirksville: Truman State University.

Questions:

You marvel how a woman, after annulling the Salic law, boldly presses Gallic necks to her authority. Alas! She unmans cocks, tearing off their crests and testicles; a virago holds sway over the French. An unbridled woman dines on [men], and as she devours this food, she smacks her lips and says, “Thus I castrate Gallic courage, thus I unman the French, thus I subdue them!”

Murphy. S (1992) ‘Catherine, Cybele and Ronsard’s Witnesses’ In Long. K (Ed) High Anxiety: Masculinity in Crisis in Early Modern France. Kirksville: Truman State University.

Questions:

- What kind of source is this?

- When was it written?

- How did this primary source interpret Catherine’s power?

Marguerite De Valois: Memoirs

Marguerite de Valois was the daughter of Catherine de Medici and the sister of the French King Charles IX. In this letter she describes the Massacre of St. Bartholomew, which took place during the celebrations of her wedding to King Henry of Navarre, the protestant. She states her knowledge of the events and any role her mother may have played in it.

King Charles, a prince of great prudence... went to the apartments of the Queen his mother, and sending for... all the Princes and Catholic officers, the "Massacre of St. Bartholomew" was that night resolved upon.

Immediately every hand was at work; chains were drawn across the streets, the alarm- bells were sounded, and every man repaired to his post, according to the orders he had received, whether it was to attack the Admiral's quarters, or those of the other Huguenots [Protestants].

I was perfectly ignorant of what was going forward. I observed everyone to be in motion: the Huguenots, driven to despair by the attack upon the Admiral's life, and the Guises, fearing they should not have justice done them, whispering all they met in the ear.

The Huguenots were suspicious of me because I was a Catholic, and the Catholics because I was married to the King of Navarre, who was a Huguenot. This being the case, no one spoke a syllable of the matter to me.

At night, when I went into the bedchamber of the Queen my mother, I placed myself on a coffer, next my sister Lorraine, who, I could not but remark, appeared greatly cast down. The Queen my mother was in conversation with some one, but, as soon as she espied me, she bade me go to bed. As I was taking leave, my sister seized me by the hand and stopped me, at the same time shedding a flood of tears: "For the love of God," cried she, "do not stir out of this chamber!" I was greatly alarmed at this exclamation; perceiving which, the Queen my mother called my sister to her, and chid her very severely. My sister replied it was sending me away to be sacrificed; for, if any discovery should be made, I should be the first victim of their revenge. The Queen my mother made answer that, if it pleased God, I should receive no hurt, but it was necessary I should go, to prevent the suspicion that might arise from my staying.

I perceived there was something on foot which I was not to know, but what it was I could not make out from anything they said...

As soon as I beheld it was broad day, I apprehended all the danger my sister had spoken of was over; and being inclined to sleep, I bade my nurse make the door fast, and I applied myself to take some repose. In about an hour I was awakened by a violent noise at the door, made with both hands and feet, and a voice calling out, "Navarre! Navarre!" My nurse, supposing the King my husband to be at the door, hastened to open it, when a gentleman... threw himself immediately upon my bed... pursued by four archers, who followed him into the bedchamber... In this situation I screamed aloud... [The] captain of the guard, came into the bedchamber, and, seeing me thus surrounded... reprimanded the archers very severely for their indiscretion, and drove them out of the chamber. [He assured] me that the King my husband was safe...

Five or six days afterwards, those who were engaged in this plot, considering that it was incomplete whilst the King my husband... remained alive... and knowing that no attempt could be made on my husband whilst I continued to be his wife, devised a scheme which they suggested to the Queen my mother for divorcing me from him.

Valois, Marguerite De. “Letter V.” The Memoirs Of Marguerite De Valois. Project Guttenberg. N.D. Retrieved from https://www.gutenberg.org/files/12967/12967-h/12967-h.htm.

Questions:

King Charles, a prince of great prudence... went to the apartments of the Queen his mother, and sending for... all the Princes and Catholic officers, the "Massacre of St. Bartholomew" was that night resolved upon.

Immediately every hand was at work; chains were drawn across the streets, the alarm- bells were sounded, and every man repaired to his post, according to the orders he had received, whether it was to attack the Admiral's quarters, or those of the other Huguenots [Protestants].

I was perfectly ignorant of what was going forward. I observed everyone to be in motion: the Huguenots, driven to despair by the attack upon the Admiral's life, and the Guises, fearing they should not have justice done them, whispering all they met in the ear.

The Huguenots were suspicious of me because I was a Catholic, and the Catholics because I was married to the King of Navarre, who was a Huguenot. This being the case, no one spoke a syllable of the matter to me.

At night, when I went into the bedchamber of the Queen my mother, I placed myself on a coffer, next my sister Lorraine, who, I could not but remark, appeared greatly cast down. The Queen my mother was in conversation with some one, but, as soon as she espied me, she bade me go to bed. As I was taking leave, my sister seized me by the hand and stopped me, at the same time shedding a flood of tears: "For the love of God," cried she, "do not stir out of this chamber!" I was greatly alarmed at this exclamation; perceiving which, the Queen my mother called my sister to her, and chid her very severely. My sister replied it was sending me away to be sacrificed; for, if any discovery should be made, I should be the first victim of their revenge. The Queen my mother made answer that, if it pleased God, I should receive no hurt, but it was necessary I should go, to prevent the suspicion that might arise from my staying.

I perceived there was something on foot which I was not to know, but what it was I could not make out from anything they said...

As soon as I beheld it was broad day, I apprehended all the danger my sister had spoken of was over; and being inclined to sleep, I bade my nurse make the door fast, and I applied myself to take some repose. In about an hour I was awakened by a violent noise at the door, made with both hands and feet, and a voice calling out, "Navarre! Navarre!" My nurse, supposing the King my husband to be at the door, hastened to open it, when a gentleman... threw himself immediately upon my bed... pursued by four archers, who followed him into the bedchamber... In this situation I screamed aloud... [The] captain of the guard, came into the bedchamber, and, seeing me thus surrounded... reprimanded the archers very severely for their indiscretion, and drove them out of the chamber. [He assured] me that the King my husband was safe...

Five or six days afterwards, those who were engaged in this plot, considering that it was incomplete whilst the King my husband... remained alive... and knowing that no attempt could be made on my husband whilst I continued to be his wife, devised a scheme which they suggested to the Queen my mother for divorcing me from him.

Valois, Marguerite De. “Letter V.” The Memoirs Of Marguerite De Valois. Project Guttenberg. N.D. Retrieved from https://www.gutenberg.org/files/12967/12967-h/12967-h.htm.

Questions:

- What kind of source is this?

- When was it written?

- Does Marguerite blame her mother for the massacre? Explain.

Master Fitzherbert: Book of Husbandry, "What Works a Wife Should Do in General"

This selection comes from a reprint of the 1534 edition of The Book of Husbandry, written by one “Master

Fitzherbert.” The book (likely) first appeared in the 1520’s, and the identity of the author is debated. In this

text, “husbandry” refers to farming and other agricultural activities at this time, but the book also

considers religion and social etiquette. The extract below considers some of the roles women played in the

life of a Tudor farm, as well as demonstrates the male author’s opinion on what a woman should be doing.

Please note that the English language here has been modernized.

It is convenient for a husband to have sheep of his own, for many causes, and then may his wife

have part of the wool, to make her husband and her-selfe some clothes. And at the least way, she may

have the locks of the sheep, either to make clothes or blankets or coverlets, or both. And if she have not

wool of her own, she may take wool to spin of clothmakers, and by that means she may have a convenient

living, and many times to do other works. It is a wife’s occupation, to winnow all manner of corn, to make

malt, to wash and wringe, to make hay, shear corn, and in time of need to help her husband to fill the

muck wagon or dung cart, drive the plough, to load hay, corn, and such other. And to go or ride to the

market, to sell butter, cheese, milk, eggs, chickens, capons [a type of poultry], hens, pigs, geese, and all

manner of corn. And also to buy all manner of necessary things belonging to household...

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Book of Husbandry by Master Fitzherbert (1534)

Questions:

Fitzherbert.” The book (likely) first appeared in the 1520’s, and the identity of the author is debated. In this

text, “husbandry” refers to farming and other agricultural activities at this time, but the book also

considers religion and social etiquette. The extract below considers some of the roles women played in the

life of a Tudor farm, as well as demonstrates the male author’s opinion on what a woman should be doing.

Please note that the English language here has been modernized.

It is convenient for a husband to have sheep of his own, for many causes, and then may his wife

have part of the wool, to make her husband and her-selfe some clothes. And at the least way, she may

have the locks of the sheep, either to make clothes or blankets or coverlets, or both. And if she have not

wool of her own, she may take wool to spin of clothmakers, and by that means she may have a convenient

living, and many times to do other works. It is a wife’s occupation, to winnow all manner of corn, to make

malt, to wash and wringe, to make hay, shear corn, and in time of need to help her husband to fill the

muck wagon or dung cart, drive the plough, to load hay, corn, and such other. And to go or ride to the

market, to sell butter, cheese, milk, eggs, chickens, capons [a type of poultry], hens, pigs, geese, and all

manner of corn. And also to buy all manner of necessary things belonging to household...

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Book of Husbandry by Master Fitzherbert (1534)

Questions:

- Describe a woman's role in society?

- Does this seem like a fair amount of work?

Christine De Pizan: The City Of Ladies

Christine de Pizan was an Italian writer and poet during the Medieval Ages. Her most notable works

include “The City of Ladies” and “Three Virtues,” in which she describes and defends the role of women in

society.

One day I was surrounded by books of all kinds... my mind dwelt at length on the

opinions of various authors whom I had studied... It made me wonder how it happened that so

many different men - and learned men among them - have been and are so inclined to express...

so many wicked insults about women and their behavior... it seems that they all speak from one

and the same mouth... Thinking deeply about these matters, I began to examine my character

and conduct as a woman and, similarly, I considered other women whose company I frequently

kept, princesses, great ladies, women of the middle and lower classes, who had told me of their

most private and intimate thoughts... No matter how long I studied the problem, I could not see

or realize how their (male writers) claims could be true when compared to the natural behavior

and character of women.

I know a woman today, named Anastasia who is so learned and skilled in painting

manuscript borders and miniature backgrounds that one cannot find an artisan in all the city of

Paris... who can surpass her... People cannot stop talking about her. And I know this from

experience, for she has executed several things for me which stand out among the paintings of

the great masters.

I am amazed by the opinion of some men who claim that they do not want their

daughters or wives to be educated because they would be ruined as a result... Not all men (and

especially the wisest) share the opinion that it is bad for women to be educated. But it is very

true that many foolish men have claimed this because it upset them that women knew more than

they did.

“The Book of the City of Ladies.” Christine de Pisan. 1405.

Questions:

include “The City of Ladies” and “Three Virtues,” in which she describes and defends the role of women in

society.

One day I was surrounded by books of all kinds... my mind dwelt at length on the

opinions of various authors whom I had studied... It made me wonder how it happened that so

many different men - and learned men among them - have been and are so inclined to express...

so many wicked insults about women and their behavior... it seems that they all speak from one

and the same mouth... Thinking deeply about these matters, I began to examine my character

and conduct as a woman and, similarly, I considered other women whose company I frequently

kept, princesses, great ladies, women of the middle and lower classes, who had told me of their

most private and intimate thoughts... No matter how long I studied the problem, I could not see

or realize how their (male writers) claims could be true when compared to the natural behavior

and character of women.

I know a woman today, named Anastasia who is so learned and skilled in painting

manuscript borders and miniature backgrounds that one cannot find an artisan in all the city of

Paris... who can surpass her... People cannot stop talking about her. And I know this from

experience, for she has executed several things for me which stand out among the paintings of

the great masters.

I am amazed by the opinion of some men who claim that they do not want their

daughters or wives to be educated because they would be ruined as a result... Not all men (and

especially the wisest) share the opinion that it is bad for women to be educated. But it is very

true that many foolish men have claimed this because it upset them that women knew more than

they did.

“The Book of the City of Ladies.” Christine de Pisan. 1405.

Questions:

- Why did Christine believe women weren’t educated in 1405 in Italy?

- What talents has she witnessed in other women?

- What role did women play in business at this time?

Christine de Pizan: Three Virtues

Christine de Pizan was an Italian writer and poet during the Medieval Ages. Her most notable works

include “The City of Ladies” and “Three Virtues,” in which she describes and defends the role of women in

society.

She (the lady of the manor) should be a good manager, knowledgeable about farming, knowing

in what weather and in what season the fields should be worked... She should often take her

recreation in the fields in order to see how the work is progressing, for there are many who

would willingly stop raking the ground beyond the surface if they thought nobody would

notice.

“Three Virtues.” Christine de Pisan. 1406.

Questions:

include “The City of Ladies” and “Three Virtues,” in which she describes and defends the role of women in

society.

She (the lady of the manor) should be a good manager, knowledgeable about farming, knowing

in what weather and in what season the fields should be worked... She should often take her

recreation in the fields in order to see how the work is progressing, for there are many who

would willingly stop raking the ground beyond the surface if they thought nobody would

notice.

“Three Virtues.” Christine de Pisan. 1406.

Questions:

- Why did Christine believe women weren’t educated in 1405 in Italy?

- What talents has she witnessed in other women?

- What role did women play in business at this time?

Queen Mary I: Act Concerning the Regal Power

An act declared by Queen Mary I of England, which made it legal for women to have sole ruling power as

the Queen. Mary began her rule in 1553 after the death of her brother, Edward VI, left no male heir to the

English throne. Female rule was considered with suspicion, and Mary’s marriage also caused concern.

Shortly after her accession, she married Prince Philip of Spain (later Philip II). Women were considered

submissive to their husbands; did that mean the Queen would be submissive to her husband in politics,

too? The English government and people became concerned that Philip would seize power, and therefore

Mary was moved to declare her intention to retain the English throne for herself. In this, Mary declares

her right to rule as a woman, and her unwillingness to relinquish her crown to a man, even her husband.

[B]e it declared and enacted by the authority of this present parliament that the law of

this realm is and ever hath been, and ought to be understood, that the kingly or regal office of

the realm, and all dignities [etc.] ... thereunto annexed, united, or belonging, being invested

either in male or female, are and be and ought to be as fully, wholly, absolutely, and entirely

deemed, judged, accepted, invested, and taken in the one as in the other; so that what or

whensoever statute or law doth limit and appoint that the king of this realm may or shall have,

execute, and do anything as king, or doth give any profit or commodity to the king, or doth limit

or appoint any pains or punishment for the correction of offenders or transgressors against the

regality and dignity of the king or of the crown, the same the queen ... may by the same authority

and power likewise have, exercise, execute, punish, correct, and do, to all intents, constructions,

and purposes, without doubt, ambiguity, scruple, or question — any custom, use, or scruple, or

any other thing whatsoever to be made to the contrary notwithstanding.

Queen Mary I, Act Concerning the Regal Power (1554) § (n.d.). https://constitution.org/1-

History/sech/sech_078.htm.

Questions:

the Queen. Mary began her rule in 1553 after the death of her brother, Edward VI, left no male heir to the

English throne. Female rule was considered with suspicion, and Mary’s marriage also caused concern.

Shortly after her accession, she married Prince Philip of Spain (later Philip II). Women were considered

submissive to their husbands; did that mean the Queen would be submissive to her husband in politics,

too? The English government and people became concerned that Philip would seize power, and therefore

Mary was moved to declare her intention to retain the English throne for herself. In this, Mary declares

her right to rule as a woman, and her unwillingness to relinquish her crown to a man, even her husband.

[B]e it declared and enacted by the authority of this present parliament that the law of

this realm is and ever hath been, and ought to be understood, that the kingly or regal office of

the realm, and all dignities [etc.] ... thereunto annexed, united, or belonging, being invested

either in male or female, are and be and ought to be as fully, wholly, absolutely, and entirely

deemed, judged, accepted, invested, and taken in the one as in the other; so that what or

whensoever statute or law doth limit and appoint that the king of this realm may or shall have,

execute, and do anything as king, or doth give any profit or commodity to the king, or doth limit

or appoint any pains or punishment for the correction of offenders or transgressors against the

regality and dignity of the king or of the crown, the same the queen ... may by the same authority

and power likewise have, exercise, execute, punish, correct, and do, to all intents, constructions,

and purposes, without doubt, ambiguity, scruple, or question — any custom, use, or scruple, or

any other thing whatsoever to be made to the contrary notwithstanding.

Queen Mary I, Act Concerning the Regal Power (1554) § (n.d.). https://constitution.org/1-

History/sech/sech_078.htm.

Questions:

- What power did this act give Queen Mary I?

- How did this act work against ideas of the time regarding a woman’s role in marriage?

Maria Theresa: General School Regulations

This order by Maria Theresa, Empress of the Holy Roman Empire, l aimed to reform education within

Austria and her territories. Under these regulations, children of both sexes were required to attend school

between the ages of six and twelve. Although women could be educated before this, requiring girls to go to

school was radical at the time.

We have realized that the education of young people , both sexes, as the most important

basis of the true happiness of the nations, however, demands a more precise level.

This subject attracted our attention all the more, the more certain of a good upbringing,

and leadership in the early years, the whole future way of life of all people, and the education of