5. Republican MotherHood

|

Following the American Revolution, there were many changes in American culture and society. . Women in this new republic found new roles and opportunities. However, many of these were shrouded by their societal expectations, particularly as mothers. In order for democracy to work in this new nation, its citizens needed to be educated and virtuous. If that was going to happen, mothers needed to be the ones to do it. The ideal of a Republican Mother emerged in this context but it did not define all the women of this era.

|

Following the American Revolution, American women’s worlds reverted into the home where education became increasingly important to support the new republic’s young citizens. Women knew significantly more than their grandmothers did about the world outside their home town and domestic comforts were becoming a new priority. While at the same time, women were increasingly finding work in “suitable” professions like teaching and writing.

In the aftermath of the Revolution, new Americans learned how to realize their rights to life, liberty, and the ability to acquire and maintain property in dramatically different ways, based on their gender, race, class, and geographic location. Women in particular had to develop their own ways to achieve those lofty revolutionary goals as women lost their official voice in American politics for the next century. The Constitution and the Bill of Rights were written by men and did not include a single acknowledgement, privilege, or protection for women. But women, in a variety of locations and environments were successful in finding a voice.

Loyalist Families:

Many families who did not support separation from England left the United States to live in a more politically and socially hospitable environment. Those who possessed considerable wealth were able to escape to England. Others, who found their limited property confiscated and who witnessed their Loyalists neighbors hanged for treason, traveled to new territories to start new lives.

In the aftermath of the Revolution, new Americans learned how to realize their rights to life, liberty, and the ability to acquire and maintain property in dramatically different ways, based on their gender, race, class, and geographic location. Women in particular had to develop their own ways to achieve those lofty revolutionary goals as women lost their official voice in American politics for the next century. The Constitution and the Bill of Rights were written by men and did not include a single acknowledgement, privilege, or protection for women. But women, in a variety of locations and environments were successful in finding a voice.

Loyalist Families:

Many families who did not support separation from England left the United States to live in a more politically and socially hospitable environment. Those who possessed considerable wealth were able to escape to England. Others, who found their limited property confiscated and who witnessed their Loyalists neighbors hanged for treason, traveled to new territories to start new lives.

One such family, that of Ephriam and Martha Ballard, traveled to the frontier region of Hallowell, Maine. There, Martha established herself as a midwife and healer, delivering more than 800 babies in a long career. She was a trusted member of her community who saw families through childbirth, epidemics, and deaths.

Martha’s work as a midwife allowed her to travel throughout the region. She knew the members of every family in Hallowell and the surrounding area. She was paid for her work, sometimes in coins, and frequently in food or rum.

On her family’s farm, she did the same work as a man, planting and harvesting food and herbs and chopping wood. Indeed, all members of the family, including young children, contributed to the growth of the farm. It was a matter of survival. On the frontier, boundaries between men’s and women’s work hardly existed. Martha could be independent because her community needed her skills. Martha’s professional career is known because she left a diary that was discovered decades after her death.

Martha’s work as a midwife allowed her to travel throughout the region. She knew the members of every family in Hallowell and the surrounding area. She was paid for her work, sometimes in coins, and frequently in food or rum.

On her family’s farm, she did the same work as a man, planting and harvesting food and herbs and chopping wood. Indeed, all members of the family, including young children, contributed to the growth of the farm. It was a matter of survival. On the frontier, boundaries between men’s and women’s work hardly existed. Martha could be independent because her community needed her skills. Martha’s professional career is known because she left a diary that was discovered decades after her death.

Martha Washington, Mount Vernon

Martha Washington, Mount Vernon

Despite the many thousands of women who performed as midwives and medical practitioners throughout the centuries, it would not be until 1849 when the first woman, Elizabeth Blackwell, would receive a medical degree in the United States. Blackwell was born in 1821 and well-educated, along with her sisters, allowing them to open a school together. While teaching was originally Blackwell’s calling, a painful incident in her young adulthood shifted her course. When a close friend lay dying, she told Blackwell that she believed she would have been spared her worst suffering if she had had a woman physician. At the time, no such thing existed, but Blackwell was determined to correct that.

In a humorous episode during her struggle to attain a medical degree, she applied to Geneva Medical College in New York state. As a cruel joke, the faculty allowed the all-male student population to vote on her application. In a twist of fate, the students unanimously voted ‘yes’ as a joke of their own. In this bizarre way, Elizabeth Blackwell became the first woman to undertake formal medical training and to earn an M.D. at an American Institution. In 1957, she would go on to found the New York Infirmary for Women and Children along with Dr. Emily Blackwell and Dr. Marie Zakrzewska, which also provided training for women doctors.

Defining the First Lady:

Further south, another woman named Martha established precedents for a woman’s supportive role. Martha Dandrige Custis Washington, a wealthy woman from Virginia, served as the hostess of the “Republican Court,” the social circle around President George Washington. A reluctant “first lady,” Martha nevertheless presided over the social affairs of the Washington administration in the temporary capitals of Philadelphia and New York. Martha Washington came from upper class Virginia society in which enslaved people served the needs of those who held title to their bodies and their labor. Nevertheless, after George Washington’s death in 1800, Martha freed the family’s slaves on January 1, 1801.

The role of America’s First Lady as a political confidante of the president took shape over time. Dolley Madison, wife of the country’s fourth president, abandoned her Quaker background to become a dominant force in the social scene of the country’s new capital of Washington, D.C..

During her husband’s tenure as Secretary of State, she hosted social events at the White House for President Jefferson and helped to raise funds for the Lewis and Clark expedition to the west. As First Lady, Dolley brought together Federalists and members of her husband’s Democratic-Republican party in social situations that facilitated occasional compromise between warring political factions.

In a humorous episode during her struggle to attain a medical degree, she applied to Geneva Medical College in New York state. As a cruel joke, the faculty allowed the all-male student population to vote on her application. In a twist of fate, the students unanimously voted ‘yes’ as a joke of their own. In this bizarre way, Elizabeth Blackwell became the first woman to undertake formal medical training and to earn an M.D. at an American Institution. In 1957, she would go on to found the New York Infirmary for Women and Children along with Dr. Emily Blackwell and Dr. Marie Zakrzewska, which also provided training for women doctors.

Defining the First Lady:

Further south, another woman named Martha established precedents for a woman’s supportive role. Martha Dandrige Custis Washington, a wealthy woman from Virginia, served as the hostess of the “Republican Court,” the social circle around President George Washington. A reluctant “first lady,” Martha nevertheless presided over the social affairs of the Washington administration in the temporary capitals of Philadelphia and New York. Martha Washington came from upper class Virginia society in which enslaved people served the needs of those who held title to their bodies and their labor. Nevertheless, after George Washington’s death in 1800, Martha freed the family’s slaves on January 1, 1801.

The role of America’s First Lady as a political confidante of the president took shape over time. Dolley Madison, wife of the country’s fourth president, abandoned her Quaker background to become a dominant force in the social scene of the country’s new capital of Washington, D.C..

During her husband’s tenure as Secretary of State, she hosted social events at the White House for President Jefferson and helped to raise funds for the Lewis and Clark expedition to the west. As First Lady, Dolley brought together Federalists and members of her husband’s Democratic-Republican party in social situations that facilitated occasional compromise between warring political factions.

Public Domain

Public Domain

When the capital was under British attack during the War of 1812, Dolley escaped the White House, saving a prized portrait of George Washington, although some think she is given too much credit, as slaves likely saved it.

Republican Mothers:

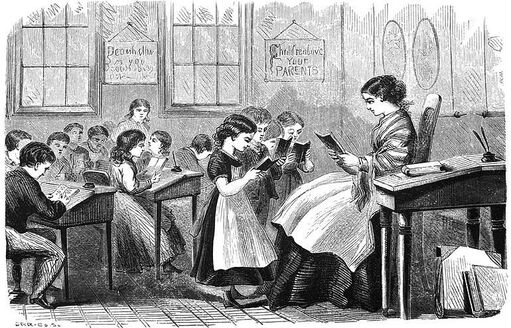

As American cities grew in the early nineteenth century, middle class women were expected to take responsibility for life at home, including raising children and maintaining religious and moral piety. Women and girls learned to read and write en masse and became the nation’s first consumer’s of books for light reading. Professional men were expected to compete in the world of work outside the home while their wives presided over the household. Some women who sought meaningful societal change outside the home became involved in social crusades to improve the lives of others, especially poor women and their children.

Magazines and books were designed with the female audience in mind, recommending fashion, etiquette, and lists of the “true” qualities of a woman: beautiful, unassuming, chaste, submissive, and domestic. It is ironic that many of the women writing these recommendations themselves actually spent much of their life in professions outside the home. It is of note that some men also championed women’s education and ideals of Republican Motherhood. In 1787, one advocate, Benjamin Rush, gave a speech called “Thoughts upon Female Education.” While many of Rush’s comments do not hide the fact that he sees women as subordinate to men, he does explain how the ability for men to pursue “different occupations for the advacement of their fortunes'' would be impossible “without the assistance of the female members of the community. They must be the stewards of their husbands’ property. That education, therefore, will be most proper for our women which teaches them to discharge the duties of those offices with the most success and reputation.” American women, Rush would later go on to say, needed knowledge of the English language, good handwriting, basic math and bookkeeping, and familiarity with geography and history. These skills in particular speak to the fact that even while women were often seen as belonging within the home, many men recognized the reality that many women would support and help their husbands in running their businesses.

Inspired by the religious fervor of the Great Awakening, these women helped to found alms houses and institutions to provide aid to women whose husbands had abandoned them to alcohol. Women raised money for charity and crusaded against the evils of “demon rum.” These women were able to succeed outside the home, even as they remained firmly within the women’s sphere of action.

Middle class urban women were expected to perform “women’s work” at home while women on the frontier could leverage agency and respect in their communities because of their skills and the need for their labor.

Fanny Wright was an English heiress who immigrated to the United States in 1825. She was passionate about social reform, especially abolition, and among her many accomplishments, became one of the first female American lecturers. When she began touring, crowds of people came to see her, one historian explained, “simply to have a look at the lecturing lady. It was a phenomenon only slightly less surprising than a talking dog.”

Republican Mothers:

As American cities grew in the early nineteenth century, middle class women were expected to take responsibility for life at home, including raising children and maintaining religious and moral piety. Women and girls learned to read and write en masse and became the nation’s first consumer’s of books for light reading. Professional men were expected to compete in the world of work outside the home while their wives presided over the household. Some women who sought meaningful societal change outside the home became involved in social crusades to improve the lives of others, especially poor women and their children.

Magazines and books were designed with the female audience in mind, recommending fashion, etiquette, and lists of the “true” qualities of a woman: beautiful, unassuming, chaste, submissive, and domestic. It is ironic that many of the women writing these recommendations themselves actually spent much of their life in professions outside the home. It is of note that some men also championed women’s education and ideals of Republican Motherhood. In 1787, one advocate, Benjamin Rush, gave a speech called “Thoughts upon Female Education.” While many of Rush’s comments do not hide the fact that he sees women as subordinate to men, he does explain how the ability for men to pursue “different occupations for the advacement of their fortunes'' would be impossible “without the assistance of the female members of the community. They must be the stewards of their husbands’ property. That education, therefore, will be most proper for our women which teaches them to discharge the duties of those offices with the most success and reputation.” American women, Rush would later go on to say, needed knowledge of the English language, good handwriting, basic math and bookkeeping, and familiarity with geography and history. These skills in particular speak to the fact that even while women were often seen as belonging within the home, many men recognized the reality that many women would support and help their husbands in running their businesses.

Inspired by the religious fervor of the Great Awakening, these women helped to found alms houses and institutions to provide aid to women whose husbands had abandoned them to alcohol. Women raised money for charity and crusaded against the evils of “demon rum.” These women were able to succeed outside the home, even as they remained firmly within the women’s sphere of action.

Middle class urban women were expected to perform “women’s work” at home while women on the frontier could leverage agency and respect in their communities because of their skills and the need for their labor.

Fanny Wright was an English heiress who immigrated to the United States in 1825. She was passionate about social reform, especially abolition, and among her many accomplishments, became one of the first female American lecturers. When she began touring, crowds of people came to see her, one historian explained, “simply to have a look at the lecturing lady. It was a phenomenon only slightly less surprising than a talking dog.”

Public Domain

Public Domain

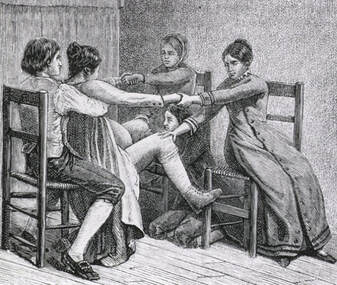

In the early 1800s the demand for public schools was incredibly high and there simply weren’t enough educated men to fill the positions. Because corporal punishment was so heavily applied in schools, educated, middle class women were looked at reluctantly to take up these posts believing that women would be unable to punish effectively. Gail Collins explained that “gender roles gave way to necessity. There simply weren’t enough men available to staff the public schools, while the pool of available educated women was huge. And the price was right. In 1838, Connecticut paid $14.50 a month to male teachers and $5.75 a month to women.” Superintendents around the country openly bragged about the productivity of the female teachers, who worked for less than half the income of the men.

Enslaved Women and Sally Hemmings:

The qualities of the “true” women or Republican Mothers, however, did not extend to enslaved women. Slaves were defined as real property. When coupled with laws that stated that children of enslaved women would also become the property of their masters, masters were essentially given a carte blanche to rape and sexually assault their female slaves. There would be no legal recourse as they could do what they wanted with their property, and they would further profit from that assault with the birth of a new slave. All this was further complicated by the horrifying reality that at any moment enslaved mothers could be torn from their children in sales and wives of masters could also potentially lash out at pregnant female slaves who they believed may be carrying their husband’s child. In short, enslaved women were denied the privilege of being Republican Mothers.

Women of color had to work hard to establish spaces in which they could assert their right to life and liberty. Women on the plantation often did the same work as men in the fields. In the house, women who served as cooks or seamstresses could inhabit positions of respect. Women also served as leaders in the community of enslaved people as they taught survival skills to their children and helped to maintain families in spite of the ever-present threat of punishment and sale.

We know precious little about Sally Hemmings, who was the “property” of Thomas Jefferson, author of the “Declaration of Independence” and the third President of the United States. Hemmings was the half sister of Jefferson’s deceased wife, Martha. We have no paintings of her, but descriptions of Sally explain that she looked similar to Martha and had a fair complexion. Historians suspect that Jefferson began a sexual relationship with Hemmings when she was approximately 15 or 16 years old–Jefferson was about 30 years her senior. Over the course of their relations, Sally bore Jefferson six children, four of whom survived childhood.

While in France, Hemmings had the opportunity to acquire her freedom; but instead, she opted to return with Jefferson to Virginia. To some, her decision to return to Virginia might seem incredulous; however, it is important to consider Hemmings age, her prior relationship with Jefferson and whatever trust or familiarity that afforded, and the fact that she would essentially be left on her own and required to abandon everything and everyone that she had known in Virginia. In short, it might appear that Hemmings chose the devil she knew rather than the devil she didn’t. Upon her return to Virginia, and through her intimate relationship with Jefferson, Hemmings was able to negotiate an easier life, even as she and her children remained enslaved. Two of her children, Beverly and Harriert, left Monticello in the 1820s and were able to pass and live as white persons, while Madison and Eston gained their freedom in Jefferson’s will on his death in 1826 due to Hemmings negotiations and were listed as free white people in the 1830 census. Jefferson did not free any other slaves–only the children of Sally Hemmings. Rumors of Jefferson’s relationship with Hemmings had been made public in the early 19th century. In the mid and late 19th century, Hemmings' children also indicated that Jefferson had fathered them. Despite these persistent rumors, the Thomas Jefferson Foundation and prominent Jefferson scholars repeatedly denied that he would have fathered children with Hemmings or had an intimate relationship with her. It was only in the 1990s that a DNA analysis matched Jefferson and a descendant of Eston Hemings, proving Jefferson’s paternity beyond a doubt; and in 2000, the Thomas Jefferson Foundation issued a report where they concluded that Thomas Jefferson was most likely the father of Sally Hemmings’ children.

Sally Hemmings established her identity beyond her status as the property of a president. But whether there was love in this relationship is difficult to know because of her young age when the relationship began, the power differential between slave and master, and her inability to provide true and free consent.

The qualities of the “true” women or Republican Mothers, however, did not extend to enslaved women. Slaves were defined as real property. When coupled with laws that stated that children of enslaved women would also become the property of their masters, masters were essentially given a carte blanche to rape and sexually assault their female slaves. There would be no legal recourse as they could do what they wanted with their property, and they would further profit from that assault with the birth of a new slave. All this was further complicated by the horrifying reality that at any moment enslaved mothers could be torn from their children in sales and wives of masters could also potentially lash out at pregnant female slaves who they believed may be carrying their husband’s child. In short, enslaved women were denied the privilege of being Republican Mothers.

Women of color had to work hard to establish spaces in which they could assert their right to life and liberty. Women on the plantation often did the same work as men in the fields. In the house, women who served as cooks or seamstresses could inhabit positions of respect. Women also served as leaders in the community of enslaved people as they taught survival skills to their children and helped to maintain families in spite of the ever-present threat of punishment and sale.

We know precious little about Sally Hemmings, who was the “property” of Thomas Jefferson, author of the “Declaration of Independence” and the third President of the United States. Hemmings was the half sister of Jefferson’s deceased wife, Martha. We have no paintings of her, but descriptions of Sally explain that she looked similar to Martha and had a fair complexion. Historians suspect that Jefferson began a sexual relationship with Hemmings when she was approximately 15 or 16 years old–Jefferson was about 30 years her senior. Over the course of their relations, Sally bore Jefferson six children, four of whom survived childhood.

While in France, Hemmings had the opportunity to acquire her freedom; but instead, she opted to return with Jefferson to Virginia. To some, her decision to return to Virginia might seem incredulous; however, it is important to consider Hemmings age, her prior relationship with Jefferson and whatever trust or familiarity that afforded, and the fact that she would essentially be left on her own and required to abandon everything and everyone that she had known in Virginia. In short, it might appear that Hemmings chose the devil she knew rather than the devil she didn’t. Upon her return to Virginia, and through her intimate relationship with Jefferson, Hemmings was able to negotiate an easier life, even as she and her children remained enslaved. Two of her children, Beverly and Harriert, left Monticello in the 1820s and were able to pass and live as white persons, while Madison and Eston gained their freedom in Jefferson’s will on his death in 1826 due to Hemmings negotiations and were listed as free white people in the 1830 census. Jefferson did not free any other slaves–only the children of Sally Hemmings. Rumors of Jefferson’s relationship with Hemmings had been made public in the early 19th century. In the mid and late 19th century, Hemmings' children also indicated that Jefferson had fathered them. Despite these persistent rumors, the Thomas Jefferson Foundation and prominent Jefferson scholars repeatedly denied that he would have fathered children with Hemmings or had an intimate relationship with her. It was only in the 1990s that a DNA analysis matched Jefferson and a descendant of Eston Hemings, proving Jefferson’s paternity beyond a doubt; and in 2000, the Thomas Jefferson Foundation issued a report where they concluded that Thomas Jefferson was most likely the father of Sally Hemmings’ children.

Sally Hemmings established her identity beyond her status as the property of a president. But whether there was love in this relationship is difficult to know because of her young age when the relationship began, the power differential between slave and master, and her inability to provide true and free consent.

Lewis, Clark, and Sacagawea, Wikimedia Commons

Lewis, Clark, and Sacagawea, Wikimedia Commons

Sacagawea and the Corps of Discovery:

One of President Jefferson’s major accomplishments in his first term was the purchase of the Louisiana Territory from France in 1803. With this bold move, Jefferson nearly doubled the land area of the United States. But neither Jefferson nor anyone in Washington, D. C. had an idea of who or what lay in the new territory beyond the Mississippi River. In August of 1803, Jefferson issued a proclamation giving Merriwether Lewis and William Clark the authority to lead the Corps of Discovery to explore and document their findings in the new territory. But Lewis and Clark could not succeed on their own. They needed the assistance of Sacagawea, a Lemhi Shoshone woman.

Sacagawea had been captured by a rival tribe in her youth and forced into a marriage with a French trader who abused her. This experience however exposed her to a variety of native and European languages which made her all the more invaluable to the mission. She was already pregnant when she and her husband met Lewis and Clark, but eventually–with her son in tow–they became part of the Corps of Discovery. At only sixteen years of age she would have likely been hopeful to serve as a guide and translator for the Lewis and Clark Expedition navigating unfamiliar rivers and encountering villages of unfamiliar tribes, as well as reuniting with her own tribe. Sacagawea was the only woman who was part of the permanent members of the discovery group. Her role was primarily translator, but also symbol of peace. Native groups they encountered along the way were unlikely to see them as hostile because of the presence of a woman with her child. But Sacagawea also dug for roots, collected plants, and picked berries. When one of their canoes capsized, Sacagawea had the presence of mind to salvage the papers and supplies that were on board. Although many of the interactions were peaceful, some were hostile and Sacagewea served as the chief negotiator. Chiefs would sometimes offer native women for sex to Lewis and Clark’s team to convey peaceful intentions. When they reached the Pacific coast, she insisted on leaving the camp to do the final stretch to see the Pacific Ocean. Sacagawea was an invaluable guide and her vote counted equally with the men’s when votes were taken. But once the mission was over, Sacagawea received nothing. Her husband, however, was paid and given land.

When she and her husband died young, her child was raised by Clark. She became a symbol of friendship between the Corps of Discovery and native people.

One of President Jefferson’s major accomplishments in his first term was the purchase of the Louisiana Territory from France in 1803. With this bold move, Jefferson nearly doubled the land area of the United States. But neither Jefferson nor anyone in Washington, D. C. had an idea of who or what lay in the new territory beyond the Mississippi River. In August of 1803, Jefferson issued a proclamation giving Merriwether Lewis and William Clark the authority to lead the Corps of Discovery to explore and document their findings in the new territory. But Lewis and Clark could not succeed on their own. They needed the assistance of Sacagawea, a Lemhi Shoshone woman.

Sacagawea had been captured by a rival tribe in her youth and forced into a marriage with a French trader who abused her. This experience however exposed her to a variety of native and European languages which made her all the more invaluable to the mission. She was already pregnant when she and her husband met Lewis and Clark, but eventually–with her son in tow–they became part of the Corps of Discovery. At only sixteen years of age she would have likely been hopeful to serve as a guide and translator for the Lewis and Clark Expedition navigating unfamiliar rivers and encountering villages of unfamiliar tribes, as well as reuniting with her own tribe. Sacagawea was the only woman who was part of the permanent members of the discovery group. Her role was primarily translator, but also symbol of peace. Native groups they encountered along the way were unlikely to see them as hostile because of the presence of a woman with her child. But Sacagawea also dug for roots, collected plants, and picked berries. When one of their canoes capsized, Sacagawea had the presence of mind to salvage the papers and supplies that were on board. Although many of the interactions were peaceful, some were hostile and Sacagewea served as the chief negotiator. Chiefs would sometimes offer native women for sex to Lewis and Clark’s team to convey peaceful intentions. When they reached the Pacific coast, she insisted on leaving the camp to do the final stretch to see the Pacific Ocean. Sacagawea was an invaluable guide and her vote counted equally with the men’s when votes were taken. But once the mission was over, Sacagawea received nothing. Her husband, however, was paid and given land.

When she and her husband died young, her child was raised by Clark. She became a symbol of friendship between the Corps of Discovery and native people.

But friendly interactions between natives who had lived in settled communities in the west for centuries and white explorers would not define western expansion of the 19th century. Instead many Americans would come to believe that the territories beyond the Mississippi River were “empty” and ripe for taking and “civilizing.” The concept of “Manifest Destiny,” the idea that the conquest of new lands was part of America’s destiny, inspired a rhetoric of conquest. The visual representation of Manifest Destiny was a female figure who led white Americans west to their prosperous future. It is notable that in this famous painting few women are portrayed as moving west, when in reality, so many women did.

When settlers moved west, bringing farms, schools, churches, telegraph wires, and railroads, women once again found ways to establish agency in their communities. Women and men were needed to work the land, and there was less separation between work and home, men’s work and women’s work. Once again, whatever the social or class context, women found ways to assert their value in society.

By the end of this era, so much remained in question. How would the emerging role of a Republican mother impact family dynamics? Why was it important for these women to have roles outside of their homes? Consider also the power of race in de-valuing the talents and accomplishments of enslaved women of color. How did these women fulfill roles as mothers and leaders in their communities within the horrifying limits of plantation life? To what extent does the history of American women, their herstory, needs more research to be told more completely?

When settlers moved west, bringing farms, schools, churches, telegraph wires, and railroads, women once again found ways to establish agency in their communities. Women and men were needed to work the land, and there was less separation between work and home, men’s work and women’s work. Once again, whatever the social or class context, women found ways to assert their value in society.

By the end of this era, so much remained in question. How would the emerging role of a Republican mother impact family dynamics? Why was it important for these women to have roles outside of their homes? Consider also the power of race in de-valuing the talents and accomplishments of enslaved women of color. How did these women fulfill roles as mothers and leaders in their communities within the horrifying limits of plantation life? To what extent does the history of American women, their herstory, needs more research to be told more completely?

Draw your own conclusions

|

Learn how to teach with inquiry.

Many of these lesson plans were sponsored in part by the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources Eastern Region Program, coordinated by Waynesburg University, the History and Social Studies Education Faculty at Plymouth State University, and the Patrons of the Remedial Herstory Project. |

Lesson Plans from Other Organizations

- The National Women's History Museum has lesson plans on women's history.

- The Gilder Lehrman Institute for American History has lesson plans on women's history.

- The NY Historical Society has articles and classroom activities for teaching women's history.

- Unladylike 2020, in partnership with PBS, has primary sources to explore with students and outstanding videos on women from the Progressive era.

- The Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media has produced recommendations for teaching women's history with primary sources and provided a collection of sources for world history. Check them out!

- The Stanford History Education Group has a number of lesson plans about women in World History.

Period Specific Lesson Plans from Other Organizations

- Women and Slavery:

- C3 Teachers: In November of 1815, an enslaved woman known only as Anna jumped out of a third floor window in Washington DC in what was assumed to be a suicide attempt. Presumed dead, abolitionists used her story to expose the harsh realities of slavery and advocate for better treatment of slaves. In 2015, the Oh Say Can You See research project uncovered an 1828 petition for freedom from an Ann Williams for herself and three children. This woman was the same “Anna” who had leapt from the window, still alive but severely injured from her fall, a contrast to the widely held belief that she had died in the fall. In 1832, a jury ruled in her favor, granting Ann and her three children freedom from master George Williams. Ann and her children went on to live free in Washington, subsisting on the weekly $1.50 that Ann’s still enslaved husband was able to provide for his family. This inquiry and the compelling question seeks to address the autonomy that enslaved African Americans had, and the question of what freedom meant to Anna.

- Stanford History Education Group: In 1937, the Federal Writers' Project began collecting what would become the largest archive of interviews with former slaves. Few firsthand accounts exist from those who suffered in slavery, making this an exceptional resource for students of history. However, as with all historical documents, there are important considerations for students to bear in mind when reading these sources. In this lesson, students examine three of these accounts to answer the question: What can we learn about slavery from interviews with former slaves?

- Gilder Lehrman: Women always played a significant role in the struggle against slavery and discrimination. White and black Quaker women and female slaves took a strong moral stand against slavery. As abolitionists, they circulated petitions, wrote letters and poems, and published articles in the leading anti-slavery periodicals such as the Liberator. Some of these women educated blacks, both free and enslaved, and some of them joined the American Anti-Slavery Society and founded their own biracial organization, the Philadelphia Women’s Anti-Slavery Society. The little-known history of most of these women is a fragmented one. While several of the most well-known activists are mentioned in accounts of the abolitionist movement, there is scant reference to most other female abolitionists. Some brief biographies make reference to the births and deaths of the lesser-known women but offer only limited mention of their work. Through research and analysis in the classroom, students will learn about the diversity of women who participated in anti-slavery activities, the variety of activities and goals they pursued, and the barriers they faced as women.

- National History Day: Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811-1896) was born in Litchfield, Connecticut, the daughter of Lyman and Roxanna Beecher. Harriet grew up in a household that held equality and service to others in the highest regard. Her father and all seven of her brothers became ministers, while her sisters, Catherine and Isabella, were champions of women’s education and suffrage. Harriet received a formal education at Sarah Pierce’s Academy, one of the first institutions focused on educating young women. There she discovered her talent for writing. Harriet became a teacher and author, proving to be an outspoken woman in a time when female voices often went unheard. Following in her family’s tradition of service, she became a passionate abolitionist. She published more than thirty works in her lifetime, the most famous of which was Uncle Tom’s Cabin, a novel that exposed the evils of slavery. Through her writings and speaking engagements, Harriet Beecher Stowe effectively helped to open the eyes of the world to the urgent problem of slavery in the United States. Did Stowe misrepresent slavery?

- Gilder Lehrman: The accounts of African American slavery in textbooks routinely conflate the story of male and female slaves into one history. Textbooks rarely enable students to grapple with the lives and challenges of women constrained by the institution of slavery. The collections of letters and autobiographies of slave women in the nineteenth century now available on the Internet open a window onto the lives of these women and allow teachers and students to explore this history. Using the classroom as a historical laboratory, students can use these primary sources to research, read, evaluate, and interpret the words of African American slave women. The students can be historians; they can discover the history of African American slave women and write their history.

- Gilder Lehrman: Children’s Attitudes about Slavery and Women’s Abolitionism as Seen through Anti-slavery Fairs: Over two days, students will examine the attitudes that children from northern states had about slavery during the 1830s to 1860s and how abolitionists tried to change their way of thinking. They will also explore how woman abolitionists used anti-slavery fairs to generate support for the anti-slavery cause.

- Edcitement: Elizabeth Keckly was born into slavery in 1818 near Petersburg, Virginia. She learned to sew from her mother, an expert seamstress enslaved in the Burwell family. After thirty years as a Burwell slave, Keckly purchased her and her only son's freedom. Later, when Keckly moved to Washington, D. C., she became an exclusive dress designer whose most famous client was First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln. Keckly’s enduring fame results from her close relationship with Mrs. Lincoln, documented in her memoir, Behind the Scenes, or Thirty Years a Slave and Four Years in the White House (1868). In this lesson, students learn firsthand about the childhoods of Jacobs and Keckly from reading excerpts from their autobiographies. They practice reading for both factual information and making inferences from these two primary sources. They will also learn from a secondary source about commonalities among those who experienced their childhood in slavery. By putting all this information together and evaluating it, students get the chance to "be" historians and experience what goes into making sound judgments about a certain problem—in this case, how did child slaves live?

- PBS and DPLA: This collection uses primary sources to explore women in the antebellum reform movement. Digital Public Library of America Primary Source Sets are designed to help students develop their critical thinking skills and draw diverse material from libraries, archives, and museums across the United States. Each set includes an overview, ten to fifteen primary sources, links to related resources, and a teaching guide. These sets were created and reviewed by the teachers on the DPLA's Education Advisory Committee.

- PBS and DPLA: This collection uses primary sources to explore Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl by Harriet Jacobs. Digital Public Library of America Primary Source Sets are designed to help students develop their critical thinking skills and draw diverse material from libraries, archives, and museums across the United States. Each set includes an overview, ten to fifteen primary sources, links to related resources, and a teaching guide. These sets were created and reviewed by the teachers on the DPLA's Education Advisory Committee.

- PBS and DPLA: This collection uses primary sources to explore Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin. Digital Public Library of America Primary Source Sets are designed to help students develop their critical thinking skills and draw diverse material from libraries, archives, and museums across the United States. Each set includes an overview, ten to fifteen primary sources, links to related resources, and a teaching guide. These sets were created and reviewed by the teachers on the DPLA's Education Advisory Committee.

Theodore Weld: Letter to Sarah and Angelina Grimké

Theodore Weld was a fellow abolitionist and later married Angelina Grimké. He wrote this letter to the sisters while they were out on speaking tour. He was doubtful that they would be effective.

My dear sisters

I had it in my heart to make a suggestion to you in my last letter about your course touching the “rights of women”, but it was crowded out by other matters perhaps of less importance...

As to the rights and wrongs of women, it is an old theme with me. It was the first subject I ever discussed. In a little debating society when a boy, I took the ground that sex neither qualified nor disqualified for the discharge of any functions mental, moral or spiritual; that there is no reason why woman should not make laws, administer justice, sit in the chair of state, plead at the bar or in the pulpit, if she has the qualifications, just as much as tho she belonged to the other sex... Now as I have never found man, woman or child who agreed with me in the “ultraism” of woman’s rights... What I advocated in boyhood I advocate now, that woman in EVERY particular shares equally with man rights and responsibilities... Now notwithstanding this, I do most deeply regret that you have begun a series of articles in the Papers on the rights of woman. Why, my dear sisters, the best possible advocacy which you can make is just what you are making day by day. Thousands hear you every week who have all their lives held that woman must not speak in public. Such a practical refutation of the dogma as your speaking furnishes has already converted multitudes... Besides you are Southerners, have been slaveholders; your dearest friends are all in the sin and shame and peril. All these things give you great access to northern mind, great sway over it...You can do more at convincing the north than twenty northern females, tho’ they could speak as well as you. Now this peculiar advantage you lose the moment you take another subject...

Let us all first wake up the nation to lift millions of slaves of both sexes from the dust, and turn them into MEN and then when we all have our hand in, it will be an easy matter to take millions of females from their knees and set them on their feet, or in other words transform them from babies into women... I pray our dear Lord to give you wisdom and grace and help and bless you forever.

Your brother T. D. Weld

*ultraism: holding of extreme opinions

Weld, Theodore. “The Letters of Theodore Weld, Angelina Grimké Weld and Sarah M. Grimké, 1822−1844.” New York: Da Capo Press, 1970. 425−432.

Questions:

My dear sisters

I had it in my heart to make a suggestion to you in my last letter about your course touching the “rights of women”, but it was crowded out by other matters perhaps of less importance...

As to the rights and wrongs of women, it is an old theme with me. It was the first subject I ever discussed. In a little debating society when a boy, I took the ground that sex neither qualified nor disqualified for the discharge of any functions mental, moral or spiritual; that there is no reason why woman should not make laws, administer justice, sit in the chair of state, plead at the bar or in the pulpit, if she has the qualifications, just as much as tho she belonged to the other sex... Now as I have never found man, woman or child who agreed with me in the “ultraism” of woman’s rights... What I advocated in boyhood I advocate now, that woman in EVERY particular shares equally with man rights and responsibilities... Now notwithstanding this, I do most deeply regret that you have begun a series of articles in the Papers on the rights of woman. Why, my dear sisters, the best possible advocacy which you can make is just what you are making day by day. Thousands hear you every week who have all their lives held that woman must not speak in public. Such a practical refutation of the dogma as your speaking furnishes has already converted multitudes... Besides you are Southerners, have been slaveholders; your dearest friends are all in the sin and shame and peril. All these things give you great access to northern mind, great sway over it...You can do more at convincing the north than twenty northern females, tho’ they could speak as well as you. Now this peculiar advantage you lose the moment you take another subject...

Let us all first wake up the nation to lift millions of slaves of both sexes from the dust, and turn them into MEN and then when we all have our hand in, it will be an easy matter to take millions of females from their knees and set them on their feet, or in other words transform them from babies into women... I pray our dear Lord to give you wisdom and grace and help and bless you forever.

Your brother T. D. Weld

*ultraism: holding of extreme opinions

Weld, Theodore. “The Letters of Theodore Weld, Angelina Grimké Weld and Sarah M. Grimké, 1822−1844.” New York: Da Capo Press, 1970. 425−432.

Questions:

- What is Weld most concerned with? See the underlined line. Why?

Sarah and Angelina Grimké: Letter to Weld and Whittier

*ultraism: holding of extreme opinions

Brethren beloved in the Lord.

As your letters came to hand at the same time and both are devoted mainly to the same subject we have concluded to answer them on one sheet and jointly. You seem greatly alarmed at the idea of our advocating the rights of woman ...These letters have not been the means of arousing the public attention to the subject of Womans rights, it was the Pastoral Letter which did the mischief... This Letter then roused the attention of the whole country to enquire what right we had to open our mouths for the dumb; the people were continually told “it is a shame for a woman to speak in the churches.” Paul suffered not a woman to teach but commanded her to be in silence. The pulpit is too sacred a place for woman’s foot etc. Now my dear brothers this invasion of our rights was just such an attack upon us, as that made upon Abolitionists generally when they were told a few years ago that they had no right to discuss the subject of Slavery. Did you take no notice of this assertion? Why no! With one heart and one voice you said, We will settle this right before we go one step further. The time to assert a right is the time when that right is denied. We must establish this right for if we do not, it will be impossible for us to go on with the work of Emancipation ...

And can you not see that women could do, and would do a hundred times more for the slave if she were not fettered? Why! we are gravely told that we are out of our sphere even when we circulate petitions; out of our “appropriate sphere” when we speak to women only; and out of them when we sing in the churches. Silence is our province, submission our duty. If then we “give no reason for the hope that is in us”, that we have equal rights with our brethren, how can we expect to be permitted much longer to exercise those rights?... If we are to do any good in the Anti Slavery cause, our right to labor in it must be firmly established...What then can woman do for the slave when she is herself under the feet of man and shamed into silence? ...

With regard to brother Welds ultraism on the subject of marriage, he is quite mistaken if he fancies he has got far ahead of us in the human rights reform. We do not think his doctrine at all shocking: it is altogether right...

May the Lord bless you my dear brothers...

A. E. G.

[P.S.] We never mention women’s rights in our lectures except so far as is necessary to urge them to meet their responsibilities...

Weld, Theodore. “The Letters of Theodore Weld, Angelina Grimké Weld and Sarah M. Grimké, 1822−1844.” New York: Da Capo Press, 1970. 425−432.

Questions:

Brethren beloved in the Lord.

As your letters came to hand at the same time and both are devoted mainly to the same subject we have concluded to answer them on one sheet and jointly. You seem greatly alarmed at the idea of our advocating the rights of woman ...These letters have not been the means of arousing the public attention to the subject of Womans rights, it was the Pastoral Letter which did the mischief... This Letter then roused the attention of the whole country to enquire what right we had to open our mouths for the dumb; the people were continually told “it is a shame for a woman to speak in the churches.” Paul suffered not a woman to teach but commanded her to be in silence. The pulpit is too sacred a place for woman’s foot etc. Now my dear brothers this invasion of our rights was just such an attack upon us, as that made upon Abolitionists generally when they were told a few years ago that they had no right to discuss the subject of Slavery. Did you take no notice of this assertion? Why no! With one heart and one voice you said, We will settle this right before we go one step further. The time to assert a right is the time when that right is denied. We must establish this right for if we do not, it will be impossible for us to go on with the work of Emancipation ...

And can you not see that women could do, and would do a hundred times more for the slave if she were not fettered? Why! we are gravely told that we are out of our sphere even when we circulate petitions; out of our “appropriate sphere” when we speak to women only; and out of them when we sing in the churches. Silence is our province, submission our duty. If then we “give no reason for the hope that is in us”, that we have equal rights with our brethren, how can we expect to be permitted much longer to exercise those rights?... If we are to do any good in the Anti Slavery cause, our right to labor in it must be firmly established...What then can woman do for the slave when she is herself under the feet of man and shamed into silence? ...

With regard to brother Welds ultraism on the subject of marriage, he is quite mistaken if he fancies he has got far ahead of us in the human rights reform. We do not think his doctrine at all shocking: it is altogether right...

May the Lord bless you my dear brothers...

A. E. G.

[P.S.] We never mention women’s rights in our lectures except so far as is necessary to urge them to meet their responsibilities...

Weld, Theodore. “The Letters of Theodore Weld, Angelina Grimké Weld and Sarah M. Grimké, 1822−1844.” New York: Da Capo Press, 1970. 425−432.

Questions:

- Why does Grimké feel the need to speak on women's rights first?

Catherine Beecher: Memoir

Catharine Beecher, the older sister of Harriet Beecher Stowe, was an avid writer and reformer. She opposed the Grimke sisters' public speaking efforts.

My Dear Friend ...

It is the grand feature of the Divine economy, that there should be different stations of superiority and subordination, and it is impossible to annihilate this beneficent and immutable law... In this arrangement of the duties of life, Heaven has appointed to one sex the superior, and to the other the subordinate station, and this without any reference to the character or conduct of either. It is therefore as much for the dignity as it is for the interest of females, in all respects to conform to the duties of this relation. And it is as much a duty as it is for the child to fulfil [sic] similar relations to parents, or subjects to rulers. But while woman holds a subordinate relation in society to the other sex, it is not because it was designed that her duties or her influence should be any the less important, or all−pervading...

Woman is to win every thing by peace and love; by making herself so much respected, esteemed and loved, that to yield to her opinions and to gratify her wishes will be the free−will offering of the heart... But the moment woman begins to feel the promptings of ambition, or the thirst for power, her [protection] is gone...

Whatever... throws a woman into the attitude of a combatant... throws her out of her appropriate sphere. If these general principles are correct, they are entirely opposed to the plan of arraying females in any Abolition movement: because it enlists them in an effort... it brings them forward as partisans in a conflict that has been begun and carried forward by measures that are any thing rather than peaceful in their tendencies; because it draws them forth from their appropriate retirement, to expose themselves to the ungoverned violence of mobs, and to sneers and ridicule in public places; because it leads them into the arena of political collision, not as peaceful mediators to hush the opposing elements, but as combatants...

If petitions from females will operate to exasperate... if they will increase, rather than diminish the evil which it is wished to remove; if they will be the opening wedge, that will tend eventually to bring females as petitioners and partisans into every political measure that may tend to injure and oppress their sex... then it is neither appropriate nor wise, nor right, for a woman to petition for the relief of oppressed females...

In this country, petitions to congress, in reference to the official duties of legislators, seem, IN ALL CASES, to fall entirely[outside] the sphere of female duty.

Beecher, Catherine. "An Essay on Slavery and Abolitionism, in Reference to the Duty of American Females." Philadelphia: Henry Perkins, 1837. 96−107.

Questions:

My Dear Friend ...

It is the grand feature of the Divine economy, that there should be different stations of superiority and subordination, and it is impossible to annihilate this beneficent and immutable law... In this arrangement of the duties of life, Heaven has appointed to one sex the superior, and to the other the subordinate station, and this without any reference to the character or conduct of either. It is therefore as much for the dignity as it is for the interest of females, in all respects to conform to the duties of this relation. And it is as much a duty as it is for the child to fulfil [sic] similar relations to parents, or subjects to rulers. But while woman holds a subordinate relation in society to the other sex, it is not because it was designed that her duties or her influence should be any the less important, or all−pervading...

Woman is to win every thing by peace and love; by making herself so much respected, esteemed and loved, that to yield to her opinions and to gratify her wishes will be the free−will offering of the heart... But the moment woman begins to feel the promptings of ambition, or the thirst for power, her [protection] is gone...

Whatever... throws a woman into the attitude of a combatant... throws her out of her appropriate sphere. If these general principles are correct, they are entirely opposed to the plan of arraying females in any Abolition movement: because it enlists them in an effort... it brings them forward as partisans in a conflict that has been begun and carried forward by measures that are any thing rather than peaceful in their tendencies; because it draws them forth from their appropriate retirement, to expose themselves to the ungoverned violence of mobs, and to sneers and ridicule in public places; because it leads them into the arena of political collision, not as peaceful mediators to hush the opposing elements, but as combatants...

If petitions from females will operate to exasperate... if they will increase, rather than diminish the evil which it is wished to remove; if they will be the opening wedge, that will tend eventually to bring females as petitioners and partisans into every political measure that may tend to injure and oppress their sex... then it is neither appropriate nor wise, nor right, for a woman to petition for the relief of oppressed females...

In this country, petitions to congress, in reference to the official duties of legislators, seem, IN ALL CASES, to fall entirely[outside] the sphere of female duty.

Beecher, Catherine. "An Essay on Slavery and Abolitionism, in Reference to the Duty of American Females." Philadelphia: Henry Perkins, 1837. 96−107.

Questions:

- Why does Beecher feel that women's rights are special?

- What concerns her with public speaking and women's rights?

Sarah Moore Grimke: Excerpts From Letters

Sarah Grimke published the following series of letters in 1837 in order to further promote her ideas.

LETTER III. THE PASTORAL LETTER OF THE GENERAL ASSOCIATION OF CONGREGATIONAL MINISTERS OF MASSACHUSETTS. No one can desire more earnestly than I do, that woman may move exactly in the sphere which her Creator has assigned her; and I believe her having been displaced from that sphere has introduced confusion into the world... The New Testament has been referred to [as justifying the inferiority of women], and I am willing to abide by its decision, but must enter my protest against the false translation of some passages by the MEN who did that work...

‘Her influence is the source of mighty power.’ This has ever been the flattering language of man since he laid aside the whip as a means to keep woman in subjection. He spares her body; but the war he has waged against her mind, her heart, and her soul, has been no less destructive to her as a moral being. How monstrous, how anti-christian, is the doctrine that woman is to be dependent on man! Where, in all the sacred Scriptures, is this taught? Alas, she has too well learned the lesson which MAN has labored to teach her. She has surrendered her dearest RIGHTS, and been satisfied with the privileges which man has assumed to grant her...

LETTER X. INTELLECT OF WOMAN. It will scarcely be denied, I presume, that, as a general rule, men do not desire the improvement of women. There are few instances of men who are magnanimous enough to be entirely willing that women should know more than themselves, on any subjects except dress and cookery; and, indeed, this necessarily flows from their assumption of superiority...

LETTER XII. LEGAL DISABILITIES OF WOMEN. Woman has no political existence... That the laws which have been generally adopted in the United States, for the government of women, have been framed almost entirely for the exclusive benefit of men, and with a design to oppress women, by depriving them of all control over their property... Men frame the laws, and, with few exceptions, claim to execute them on both sexes... Although looked upon as an inferior, when considered as an intellectual being, woman is punished with the same severity as man, when she is guilty of moral offences...

Thine in the bonds of womanhood, SARAH M. GRIMKÉ

Sarah M. Grimké, Letters on the Equality of the Sexes, and the Condition of Woman (Boston: Isaac Knapp, 1838), 12, 15-17, 23, 27, 33, 40-41, 45, 54-55, 61, 74, 81, 83, 86- 87, 121-123.

Questions:

LETTER III. THE PASTORAL LETTER OF THE GENERAL ASSOCIATION OF CONGREGATIONAL MINISTERS OF MASSACHUSETTS. No one can desire more earnestly than I do, that woman may move exactly in the sphere which her Creator has assigned her; and I believe her having been displaced from that sphere has introduced confusion into the world... The New Testament has been referred to [as justifying the inferiority of women], and I am willing to abide by its decision, but must enter my protest against the false translation of some passages by the MEN who did that work...

‘Her influence is the source of mighty power.’ This has ever been the flattering language of man since he laid aside the whip as a means to keep woman in subjection. He spares her body; but the war he has waged against her mind, her heart, and her soul, has been no less destructive to her as a moral being. How monstrous, how anti-christian, is the doctrine that woman is to be dependent on man! Where, in all the sacred Scriptures, is this taught? Alas, she has too well learned the lesson which MAN has labored to teach her. She has surrendered her dearest RIGHTS, and been satisfied with the privileges which man has assumed to grant her...

LETTER X. INTELLECT OF WOMAN. It will scarcely be denied, I presume, that, as a general rule, men do not desire the improvement of women. There are few instances of men who are magnanimous enough to be entirely willing that women should know more than themselves, on any subjects except dress and cookery; and, indeed, this necessarily flows from their assumption of superiority...

LETTER XII. LEGAL DISABILITIES OF WOMEN. Woman has no political existence... That the laws which have been generally adopted in the United States, for the government of women, have been framed almost entirely for the exclusive benefit of men, and with a design to oppress women, by depriving them of all control over their property... Men frame the laws, and, with few exceptions, claim to execute them on both sexes... Although looked upon as an inferior, when considered as an intellectual being, woman is punished with the same severity as man, when she is guilty of moral offences...

Thine in the bonds of womanhood, SARAH M. GRIMKÉ

Sarah M. Grimké, Letters on the Equality of the Sexes, and the Condition of Woman (Boston: Isaac Knapp, 1838), 12, 15-17, 23, 27, 33, 40-41, 45, 54-55, 61, 74, 81, 83, 86- 87, 121-123.

Questions:

- What topics on women's rights does Grimké tackle?

Margarett Fuller: Women In The Nineteenth Century

Margarett Fuller was a writer and an editor. In the 1840’s she was an editor for the Transcendentalist journal, Dial. In the July 1843 issue she wrote an article titled "The Great Lawsuit: Man Versus Men: Woman Versus Women." This piece is considered a classic among feminist literature. The larger version discusses controversial topics such as prostitution and slavery, marriage, employment, and reform.

Much has been written about woman's keeping within her sphere, which is defined as the domestic sphere. As a little girl she is to learn the lighter family duties, while she acquires that limited acquaintance with the realm of literature and science that will enable her to superintend the instruction of children in their earliest years. It is not generally proposed that she should be sufficiently instructed and developed to understand the pursuits or aims of her future husband; she is not to be a help-meet to him in the way of companionship and counsel, except in the care of his house and children. Her youth is to be passed partly in learning to keep house and the use of the needle, partly in the social circle, where her manners may be formed, ornamental accomplishments perfected and displayed, and the husband found who shall give her the domestic sphere for which she is exclusively to be prepared.

Were the destiny of Woman thus exactly marked out; did she invariably retain the shelter of a parent's or guardian's roof till she married; did marriage give her a sure home and protector; were she never liable to remain a widow, or, if so, sure of finding immediate protection of a brother or new husband, so that she might never be forced to stand alone one moment; and were her mind given for this world only, with no faculties capable of eternal growth and infinite improvement; we would still demand for her a far wider and more generous culture, than is proposed by those who so anxiously define her sphere.

Margaret Fuller, Woman in the Nineteenth Century. New York: Greeley & McElrath, 160 Nassau Street, 1845.

Questions:

Much has been written about woman's keeping within her sphere, which is defined as the domestic sphere. As a little girl she is to learn the lighter family duties, while she acquires that limited acquaintance with the realm of literature and science that will enable her to superintend the instruction of children in their earliest years. It is not generally proposed that she should be sufficiently instructed and developed to understand the pursuits or aims of her future husband; she is not to be a help-meet to him in the way of companionship and counsel, except in the care of his house and children. Her youth is to be passed partly in learning to keep house and the use of the needle, partly in the social circle, where her manners may be formed, ornamental accomplishments perfected and displayed, and the husband found who shall give her the domestic sphere for which she is exclusively to be prepared.

Were the destiny of Woman thus exactly marked out; did she invariably retain the shelter of a parent's or guardian's roof till she married; did marriage give her a sure home and protector; were she never liable to remain a widow, or, if so, sure of finding immediate protection of a brother or new husband, so that she might never be forced to stand alone one moment; and were her mind given for this world only, with no faculties capable of eternal growth and infinite improvement; we would still demand for her a far wider and more generous culture, than is proposed by those who so anxiously define her sphere.

Margaret Fuller, Woman in the Nineteenth Century. New York: Greeley & McElrath, 160 Nassau Street, 1845.

Questions:

- What concerns Fuller about the idea that women need male protection?

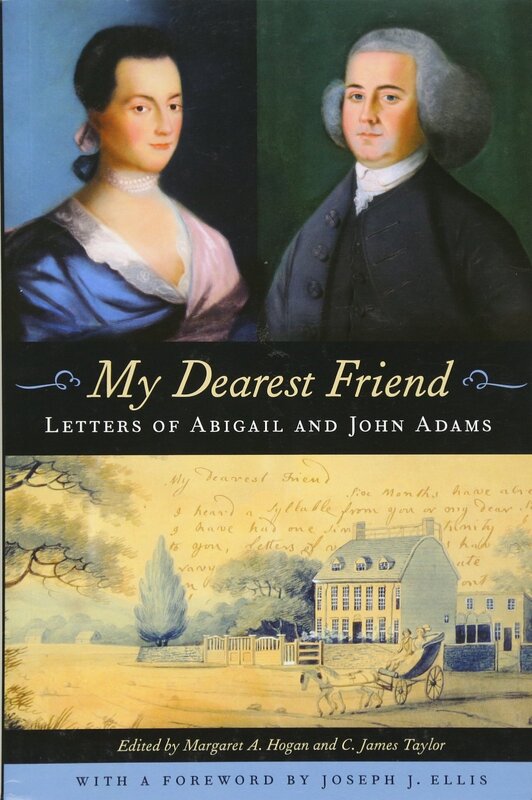

Abigail Adams: Telling Her Husband To "Remember The Ladies"

I long to hear that you have declared an independancy—and by the way in the new Code of Laws which I suppose it will be necessary for you to make I desire you would Remember the Ladies, and be more generous and favourable to them than your ancestors. Do not put such unlimited power into the hands of the Husbands. Remember all Men would be tyrants if they could. If perticuliar care and attention is not paid to the Laidies we are determined to foment a Rebelion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any Laws in which we have no voice, or Representation.

That your Sex are Naturally Tyrannical is a Truth so thoroughly established as to admit of no dispute, but such of you as wish to be happy willingly give up the harsh title of Master for the more tender and endearing one of Friend. Why then, not put it out of the power of the vicious and the Lawless to use us with cruelty and indignity with impunity. Men of Sense in all Ages abhor those customs which treat us only as the vassals of your Sex. Regard us then as Beings placed by providence under your protection and in immitation of the Supreem Being make use of that power only for our happiness.

“Abigail Adams to John Adams, 31 March 1776,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/04-01-02-0241. [Original source: The Adams Papers, Adams Family Correspondence, vol. 1, December 1761 – May 1776, ed. Lyman H. Butterfield. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1963, pp. 369–371.]

Questions:

That your Sex are Naturally Tyrannical is a Truth so thoroughly established as to admit of no dispute, but such of you as wish to be happy willingly give up the harsh title of Master for the more tender and endearing one of Friend. Why then, not put it out of the power of the vicious and the Lawless to use us with cruelty and indignity with impunity. Men of Sense in all Ages abhor those customs which treat us only as the vassals of your Sex. Regard us then as Beings placed by providence under your protection and in immitation of the Supreem Being make use of that power only for our happiness.

“Abigail Adams to John Adams, 31 March 1776,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/04-01-02-0241. [Original source: The Adams Papers, Adams Family Correspondence, vol. 1, December 1761 – May 1776, ed. Lyman H. Butterfield. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1963, pp. 369–371.]

Questions:

- What does Abigail Adams tell her husband John? Why does she say “Remember the Ladies”?

John Adams: Response To Abigail Adams "Remember The Ladies"

As to your extraordinary Code of Laws, I cannot but laugh. We have been told that our Struggle has loosened the bands of Government every where. That Children and Apprentices were disobedient—that schools and Colledges were grown turbulent— that Indians slighted their Guardians and Negroes grew insolent to their Masters. But your Letter was the first Intimation that another Tribe more numerous and powerfull than all the rest were grown discontented.—This is rather too coarse a Compliment but you are so saucy, I wont blot it out.

Depend upon it, We know better than to repeal our Masculine systems. Altho they are in full Force, you know they are little more than Theory. We dare not exert our Power in its full Latitude. We are obliged to go fair, and softly, and in Practice you know We are the subjects. We have only the Name of Masters, and rather than give up this, which would compleatly subject Us to the Despotism of the Peticoat, I hope General Washington, and all our brave Heroes would fight.

“John Adams to Abigail Adams, 14 April 1776,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/04-01-02-0248. [Original source: The Adams Papers, Adams Family Correspondence, vol. 1, December 1761 – May 1776, ed. Lyman H. Butterfield. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1963, pp. 381–383.]

Questions:

Depend upon it, We know better than to repeal our Masculine systems. Altho they are in full Force, you know they are little more than Theory. We dare not exert our Power in its full Latitude. We are obliged to go fair, and softly, and in Practice you know We are the subjects. We have only the Name of Masters, and rather than give up this, which would compleatly subject Us to the Despotism of the Peticoat, I hope General Washington, and all our brave Heroes would fight.

“John Adams to Abigail Adams, 14 April 1776,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/04-01-02-0248. [Original source: The Adams Papers, Adams Family Correspondence, vol. 1, December 1761 – May 1776, ed. Lyman H. Butterfield. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1963, pp. 381–383.]

Questions:

- What is John’s reaction to Abigail’s?

- What does John Adams compare women to? Why is that significant?

John Adams: The Danger Of Democracy

Our worthy Friend, Mr. Gerry has put into my Hand, a Letter from you, of the Sixth of May, in which you consider the Principles of Representation and Legislation, and give us Hints of Some Alterations, which you Seem to think necessary, in the Qualification of Voters. . . .

What Reason Should there be, for excluding a Man of Twenty years, Eleven Months and twenty-seven days old, from a Vote when you admit one, who is twenty one? The Reason is, you must fix upon Some Period in Life, when the Understanding and Will of Men in general is fit to be trusted by the Public. Will not the Same Reason justify the State in fixing upon Some certain Quantity of Property, as a Qualification.

The Same Reasoning, which will induce you to admit all Men, who have no Property, to vote, with those who have, for those Laws, which affect the Person will prove that you ought to admit Women and Children . . . .

Society can be governed only by general Rules. Government cannot accommodate itself to every particular Case, as it happens, nor to the Circumstances of particular Persons. It must establish general, comprehensive Regulations for Cases and Persons. The only Question is, which general Rule, will accommodate most Cases and most Persons.

Depend upon it, sir, it is dangerous to open So fruitfull a Source of Controversy and Altercation, as would be opened by attempting to alter the Qualifications of Voters. There will be no End of it. New Claims will arise. Women will demand a Vote. Lads from 12 to 21 will think their Rights not enough attended to, and every Man, who has not a Farthing, will demand an equal Voice with any other in all Acts of State. It tends to confound and destroy all Distinctions, and prostrate all Ranks, to one common Levell.

“From John Adams to James Sullivan, 26 May 1776,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/06-04-02-0091. [Original source: The Adams Papers, Papers of John Adams, vol. 4, February–August 1776, ed. Robert J. Taylor. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1979, pp. 208–213.]

Questions:

What Reason Should there be, for excluding a Man of Twenty years, Eleven Months and twenty-seven days old, from a Vote when you admit one, who is twenty one? The Reason is, you must fix upon Some Period in Life, when the Understanding and Will of Men in general is fit to be trusted by the Public. Will not the Same Reason justify the State in fixing upon Some certain Quantity of Property, as a Qualification.

The Same Reasoning, which will induce you to admit all Men, who have no Property, to vote, with those who have, for those Laws, which affect the Person will prove that you ought to admit Women and Children . . . .

Society can be governed only by general Rules. Government cannot accommodate itself to every particular Case, as it happens, nor to the Circumstances of particular Persons. It must establish general, comprehensive Regulations for Cases and Persons. The only Question is, which general Rule, will accommodate most Cases and most Persons.

Depend upon it, sir, it is dangerous to open So fruitfull a Source of Controversy and Altercation, as would be opened by attempting to alter the Qualifications of Voters. There will be no End of it. New Claims will arise. Women will demand a Vote. Lads from 12 to 21 will think their Rights not enough attended to, and every Man, who has not a Farthing, will demand an equal Voice with any other in all Acts of State. It tends to confound and destroy all Distinctions, and prostrate all Ranks, to one common Levell.

“From John Adams to James Sullivan, 26 May 1776,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/06-04-02-0091. [Original source: The Adams Papers, Papers of John Adams, vol. 4, February–August 1776, ed. Robert J. Taylor. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1979, pp. 208–213.]

Questions:

- Who does John Adams believe should have the right to vote?

- Why does John Adams believe women are unfit to vote?

Phillis Wheatley: His Excellency George Washington

One century scarce perform'd its destined round, When Gallic powers Columbia's fury found; And so may you, whoever dares disgrace The land of freedom's heaven-defended race! Fix'd are the eyes of nations on the scales, For in their hopes Columbia's arm prevails.

Wheatley, Phillis. “His Excellency General Washington,” 1776. https://poets.org/poem/his- excellency-general-washington.

Questions:

Wheatley, Phillis. “His Excellency General Washington,” 1776. https://poets.org/poem/his- excellency-general-washington.

Questions:

- How does Phillis Wheatley, a formerly enslaved African woman, describe Washington and the Americans fight for freedom?

George Washington: Response To Poem

Mrs Phillis,

Your favour of the 26th of October did not reach my hands ’till the middle of December. Time enough, you will say, to have given an answer ere this. Granted. But a variety of important occurrences, continually interposing to distract the mind and withdraw the attention, I hope will apologize for the delay, and plead my excuse for the seeming, but not real, neglect.

I thank you most sincerely for your polite notice of me, in the elegant Lines you enclosed; and however undeserving I may be of such encomium and panegyrick, the style and manner exhibit a striking proof of your great poetical Talents. In honour of which, and as a tribute justly due to you, I would have published the Poem, had I not been apprehensive, that, while I only meant to give the World this new instance of your genius, I might have incurred the imputation of Vanity. This, and nothing else, determined me not to give it place in the public Prints.1

If you should ever come to Cambridge, or near Head Quarters, I shall be happy to see a person so favourd by the Muses, and to whom nature has been so liberal and beneficent in her dispensations. I am, with great Respect, Your obedt humble servant,

G. Washington

The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 3, 1 January 1776 – 31 March 1776, ed. Philander D. Chase. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1988, p. 387.

Questions:

Your favour of the 26th of October did not reach my hands ’till the middle of December. Time enough, you will say, to have given an answer ere this. Granted. But a variety of important occurrences, continually interposing to distract the mind and withdraw the attention, I hope will apologize for the delay, and plead my excuse for the seeming, but not real, neglect.