21. Women and the Civil Rights Movement

|

The bold actions and sacrifices made by many women involved with the Civil Right Movement are frequently overlooked or overshadowed by the contributions of their male counterparts. The pivotal impacts made by notable women like Rosa Parks and JoAnn Robinson were credited to the achievements by figures such as Martin Luther King Jr. Female civil rights activists were subjected to unlawful detainment, assault, torture, and murder. These heroic women, and their stories, generated momentum for the cause, often with little to no acknowledgement.

|

Recy Taylor, Public Domain

Recy Taylor, Public Domain

When we think about the American Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 60s, names of prominent Black men often come to mind. And they’re great! But! Alongside those men--or other times off on their own initiatives--were women of color. Black women were a fearless force to be reckoned with in the Civil Rights Movement, and their work for social justice began well before the white press began paying attention.

Black people had been working for Civil Rights since the Civil War ended--through Reconstruction, after the Supreme Court upheld segregation in the Plessy v. Ferguson case, and through the Great Migration surrounding WWI. But it was the aftermath of WWII that finally pushed Civil Rights to bold national, white, awareness. Black folks found the American rhetoric about the mistreatment of European Jews deeply hypocritical. Many could clearly see parallels between the ghettos of Europe and the redlined cities of the US. Americans and the American government were obsessed with condemning prejudice overseas, but were often reluctant or indifferent to the prejudice in their own backyard.

Black women especially had been dealing with horrifying prejudice for generations, and some of the earliest civil rights activists were fighting for legal protections in the aftermath of sexual assaults against Black women.

Rapes of Recy Taylor and Gertrude Perkins:

Rape and sexual assault of Black women has a long history in the United States. Enslaved women were often terrorized sexually while working on plantations. That trauma persisted for decades. In the South, most states developed laws that incentivized the rape and sexual assault of their female slaves, by defining the children of enslaved women as the property of their white owners. With a foundation of race and gender relations like that, many white men simply didn’t see women of color as equal human beings. They saw these women as bodies that could give birth to greater wealth. Specifically, many white men didn’t understand Black women had rights to their own bodies--a concept called bodily integrity.

The predominant perpetrators of rape in southern communities were white men. But for some reason, a fear of Black male sexuality grew in the public dialogue during the Reconstruction era. Black men were regularly and often falsely accused of sexual assault of white women, usually resulting in convictions and the death penalty, or vigilante justice by lynching. Meanwhile white men, accused of the same crime, might never see the inside of a jail cell–or might argue that the rape was actually consensual sex. This double standard in southern courts led women of color to often staying silent in the face of sexual harassment and assault. However, as it became more clear Black men were unable to defend “their women” because of white terrorism, Black women eventually realized they would need to use their own voices.

Although not the first and certainly not the last, Recy Taylor stands out as a woman undeterred by white male aggression. On September 3rd, 1944, when she was 24-years-old, she was walking home from church in Abbeville, Alabama, with her friend and her friend’s teenage son when she was abducted and raped by six white men. Dumped from the car blindfolded, she was miraculously able to stumble home, bloodied and terrified, and turned that fear into action. She reported the account to her family and the Sheriff investigated. Taylor couldn’t identify the assailants but could describe the car–and only one man in town had a car fitting the description. The driver named names and all the men stated that it wasn’t rape. They claimed to have paid her for sex.

During the fallout, white terrorists set Taylor’s porch on fire to intimidate her. Her family moved in with her parents and the Black community set up a guard in a nearby tree at night.

Of the encounter, Taylor said, “The peoples there — they seemed like they wasn’t concerned about what happened to me, and they didn’t try and do nothing about it. I can’t help but tell the truth of what they done to me.” Even though she worried pushing for justice was putting her family in danger, she couldn’t help but tell the truth.

The NAACP sent a young female activist from Montgomery, Alabama to investigate the case. She was also a sexual assault survivor, and her name was Rosa Parks. The story was published in the Black press and African Americans around the country demanded that the men be prosecuted. The police attempted to intimidate Parks and threatened her in order to get her to leave town, but Parks–who, later, will become more well known for once again staying where she wants–didn’t leave.

Taylor’s case resulted in a Grand Jury procedure, but none of the white men were arrested or indicted. Eugene Gordon, a Black writer for The Daily Worker, said, “The raping of Mrs. Recy Taylor was a fascist-like brutal violation of her personal rights as a woman and as a citizen of democracy.”

Soon famous leaders of Black liberation and suffrage like Mary Church Terrell worked for Taylor’s case too, but a second grand jury resulted in the same inaction. Although Taylor never got the justice she deserved, her fierce boldness was an inspiring piece of the collective movement. Taylor’s case would not be the last of this sort. As a result, Black women couldn’t just move on. Their assault continued, and, in many ways, continues to this day.

Black people had been working for Civil Rights since the Civil War ended--through Reconstruction, after the Supreme Court upheld segregation in the Plessy v. Ferguson case, and through the Great Migration surrounding WWI. But it was the aftermath of WWII that finally pushed Civil Rights to bold national, white, awareness. Black folks found the American rhetoric about the mistreatment of European Jews deeply hypocritical. Many could clearly see parallels between the ghettos of Europe and the redlined cities of the US. Americans and the American government were obsessed with condemning prejudice overseas, but were often reluctant or indifferent to the prejudice in their own backyard.

Black women especially had been dealing with horrifying prejudice for generations, and some of the earliest civil rights activists were fighting for legal protections in the aftermath of sexual assaults against Black women.

Rapes of Recy Taylor and Gertrude Perkins:

Rape and sexual assault of Black women has a long history in the United States. Enslaved women were often terrorized sexually while working on plantations. That trauma persisted for decades. In the South, most states developed laws that incentivized the rape and sexual assault of their female slaves, by defining the children of enslaved women as the property of their white owners. With a foundation of race and gender relations like that, many white men simply didn’t see women of color as equal human beings. They saw these women as bodies that could give birth to greater wealth. Specifically, many white men didn’t understand Black women had rights to their own bodies--a concept called bodily integrity.

The predominant perpetrators of rape in southern communities were white men. But for some reason, a fear of Black male sexuality grew in the public dialogue during the Reconstruction era. Black men were regularly and often falsely accused of sexual assault of white women, usually resulting in convictions and the death penalty, or vigilante justice by lynching. Meanwhile white men, accused of the same crime, might never see the inside of a jail cell–or might argue that the rape was actually consensual sex. This double standard in southern courts led women of color to often staying silent in the face of sexual harassment and assault. However, as it became more clear Black men were unable to defend “their women” because of white terrorism, Black women eventually realized they would need to use their own voices.

Although not the first and certainly not the last, Recy Taylor stands out as a woman undeterred by white male aggression. On September 3rd, 1944, when she was 24-years-old, she was walking home from church in Abbeville, Alabama, with her friend and her friend’s teenage son when she was abducted and raped by six white men. Dumped from the car blindfolded, she was miraculously able to stumble home, bloodied and terrified, and turned that fear into action. She reported the account to her family and the Sheriff investigated. Taylor couldn’t identify the assailants but could describe the car–and only one man in town had a car fitting the description. The driver named names and all the men stated that it wasn’t rape. They claimed to have paid her for sex.

During the fallout, white terrorists set Taylor’s porch on fire to intimidate her. Her family moved in with her parents and the Black community set up a guard in a nearby tree at night.

Of the encounter, Taylor said, “The peoples there — they seemed like they wasn’t concerned about what happened to me, and they didn’t try and do nothing about it. I can’t help but tell the truth of what they done to me.” Even though she worried pushing for justice was putting her family in danger, she couldn’t help but tell the truth.

The NAACP sent a young female activist from Montgomery, Alabama to investigate the case. She was also a sexual assault survivor, and her name was Rosa Parks. The story was published in the Black press and African Americans around the country demanded that the men be prosecuted. The police attempted to intimidate Parks and threatened her in order to get her to leave town, but Parks–who, later, will become more well known for once again staying where she wants–didn’t leave.

Taylor’s case resulted in a Grand Jury procedure, but none of the white men were arrested or indicted. Eugene Gordon, a Black writer for The Daily Worker, said, “The raping of Mrs. Recy Taylor was a fascist-like brutal violation of her personal rights as a woman and as a citizen of democracy.”

Soon famous leaders of Black liberation and suffrage like Mary Church Terrell worked for Taylor’s case too, but a second grand jury resulted in the same inaction. Although Taylor never got the justice she deserved, her fierce boldness was an inspiring piece of the collective movement. Taylor’s case would not be the last of this sort. As a result, Black women couldn’t just move on. Their assault continued, and, in many ways, continues to this day.

Rosa Parks, Wikimedia Commons

Rosa Parks, Wikimedia Commons

On March 27, 1949, Gertrude Perkins was walking home when two white Montgomery police officers arrested her for “public drunkenness.” They threw her in the squad car, drove to a secluded spot, and raped her at gunpoint. Perkins first reported the crime to a Reverend who wisely had her account notarized. “We didn’t go to bed that morning…I kept her at my house, carefully wrote down what she said” he reported. Perkins then bravely, with supportive escorts, reported the crime to the all white police. The police chief flat out refused to investigate claiming, “my policemen would not do a thing like that.”

Again, Rosa Parks was called in. It seemed like case after case of assault on the bodies of Black women, but little was done by the white establishment. Black women did not benefit from gendered assumptions about sexual virtue and purity because of white supremacy.

Women’s Political Council:

Finally, the women of Montgomery, Alabama had enough. They organized the Women’s Political Council under the leadership of JoAnn Robinson. They decided to direct their anger aagainstt racist bus drivers--white men who threatened or harassed Black women daily, as they headed to and from work. Plus, drivers had police authority back then, so they carried weapons--obviously making it difficult to confront them. One specific driver would expose himself to Black women as he pulled up to their stop. Clearly many of these drivers felt untouchable.

It was dangerous to file a complaint against one of these drivers. And yet! In 1953 alone, Black citizens of Montgomery filed over thirty formal complaints of abuse and mistreatment on the buses.

As early as 1954 Robinson threatened a boycott of the city buses. She wrote in a letter to the mayor, “Mayor Gayle, three-fourths of the riders of these public conveyances are Negroes. If Negroes did not patronize them, they could not possibly operate. More and more of our people are already arranging with neighbors and friends to ride to keep from being insulted and humiliated by bus drivers… Please consider this plea, and if possible, act favorably upon it, for even now plans are being made to ride less, or not at all, on our buses.”

Colvin and Parks Protest:

But, of course, the situation continued. On March 2, 1955, Claudette Colvin, a teenager from Montgomery, Alabama, refused to give up her seat on a segregated bus. She was removed from the bus by two police officers and kept in a jail cell until her mother and pastor posted her bail. She hoped word of her experience would help elevate the cause of integration, but she became pregnant. Because most people had negative attitudes toward unmarried mothers, her actions did not receive public attention.

Again, Rosa Parks was called in. It seemed like case after case of assault on the bodies of Black women, but little was done by the white establishment. Black women did not benefit from gendered assumptions about sexual virtue and purity because of white supremacy.

Women’s Political Council:

Finally, the women of Montgomery, Alabama had enough. They organized the Women’s Political Council under the leadership of JoAnn Robinson. They decided to direct their anger aagainstt racist bus drivers--white men who threatened or harassed Black women daily, as they headed to and from work. Plus, drivers had police authority back then, so they carried weapons--obviously making it difficult to confront them. One specific driver would expose himself to Black women as he pulled up to their stop. Clearly many of these drivers felt untouchable.

It was dangerous to file a complaint against one of these drivers. And yet! In 1953 alone, Black citizens of Montgomery filed over thirty formal complaints of abuse and mistreatment on the buses.

As early as 1954 Robinson threatened a boycott of the city buses. She wrote in a letter to the mayor, “Mayor Gayle, three-fourths of the riders of these public conveyances are Negroes. If Negroes did not patronize them, they could not possibly operate. More and more of our people are already arranging with neighbors and friends to ride to keep from being insulted and humiliated by bus drivers… Please consider this plea, and if possible, act favorably upon it, for even now plans are being made to ride less, or not at all, on our buses.”

Colvin and Parks Protest:

But, of course, the situation continued. On March 2, 1955, Claudette Colvin, a teenager from Montgomery, Alabama, refused to give up her seat on a segregated bus. She was removed from the bus by two police officers and kept in a jail cell until her mother and pastor posted her bail. She hoped word of her experience would help elevate the cause of integration, but she became pregnant. Because most people had negative attitudes toward unmarried mothers, her actions did not receive public attention.

JoAnn Robinson, Public Domain

JoAnn Robinson, Public Domain

Meanwhile, the NAACP geared up for direct action against segregation in Montgomery. However, the local male chapter leadership did not feel that the community was ready. So it was actually the actions of individual women--like Lucille Times--that pushed Montgomery’s Black community to the soon to be historical bus boycott. On June 15, 1955, Mrs. Times was driving to her local dry cleaners when the driver of a city bus tried to force her off the road. She and the driver exchanged angry words and even punches. When the police were called she was lucky not to have been arrested or beaten. When her complaints about the driver’s actions were ignored, Lucille Times mounted a one-woman boycott of city buses. She used her own car to offer rides to people waiting at bus stops, explaining why it was important to strike an economic blow against segregation.

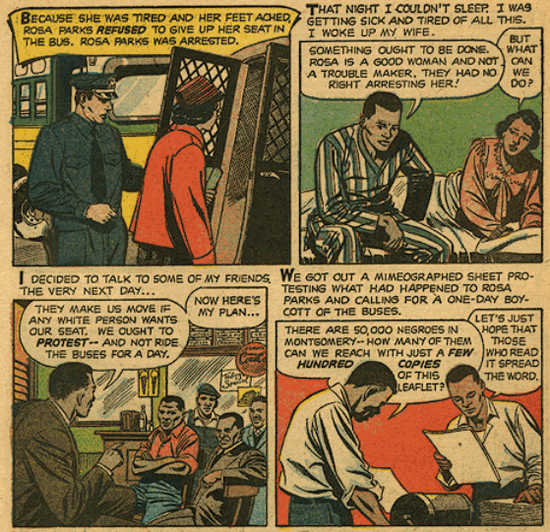

Six months later, the Black community in Montgomery was up and ready for action. On December 1, 1955, Rosa Parks, now a veteran in the struggle for bodily integrity, refused to give up her seat. She was arrested.

Overnight JoAnn Robinson threw the community into action. She wrote and distributed with the help of the Women’s Political Council 35 thousand copies of this leaflet:

“Another Negro woman has been arrested and thrown in jail because she refused to get up out of her seat on the bus for a white person to sit down. It is the second time since the Claudette Colvin case that a Negro woman has been arrested for the same thing. This has to be stopped. Negroes have rights, too, for its Negroes did not ride the buses, they could not operate.” Translation: you think we’re bluffing? Try us.

Six months later, the Black community in Montgomery was up and ready for action. On December 1, 1955, Rosa Parks, now a veteran in the struggle for bodily integrity, refused to give up her seat. She was arrested.

Overnight JoAnn Robinson threw the community into action. She wrote and distributed with the help of the Women’s Political Council 35 thousand copies of this leaflet:

“Another Negro woman has been arrested and thrown in jail because she refused to get up out of her seat on the bus for a white person to sit down. It is the second time since the Claudette Colvin case that a Negro woman has been arrested for the same thing. This has to be stopped. Negroes have rights, too, for its Negroes did not ride the buses, they could not operate.” Translation: you think we’re bluffing? Try us.

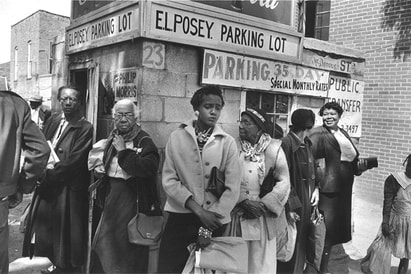

Montgomery Bus Boycott, Public Domain

Montgomery Bus Boycott, Public Domain

The next day women and men walked to work. Historian Danielle McGuire comments on how the root of the bus boycott came from the earlier assault on Black women’s bodies. She says, “These experiences propelled African American women into every conceivable aspect of the boycott. Women were the chief strategists and negotiators of the boycott and ran its day-to-day operation. Women helped staff the elaborate carpool system, raised most of the local money for the movement, and filled the majority of the pews at the mass meetings, where they testified publicly about physical and sexual abuse on the buses.” While those initial assault losses were brutal, they set the scene and propelled the Black community toward the most well-known event of the Civil Rights era.

Scenes from the Montgomery Bus Boycott were broadcast throughout the nation. Images of people walking to work inspired activists throughout the south to continue challenging segregation, but the women who started the movement were pushed to the side when the male leaders and reverends in the community took over the boycott and became their figureheads.. Names like the then 26-year-old Martin Luther King overshadowed the women, and in some cases took credit for their efforts.

Scenes from the Montgomery Bus Boycott were broadcast throughout the nation. Images of people walking to work inspired activists throughout the south to continue challenging segregation, but the women who started the movement were pushed to the side when the male leaders and reverends in the community took over the boycott and became their figureheads.. Names like the then 26-year-old Martin Luther King overshadowed the women, and in some cases took credit for their efforts.

Linda Brown, Little Rock Nine, and Ruby Bridges:

Of course, Montgomery was only the beginning of the movement. Quietly in the courts a little girl named Linda Brown was fighting a battle for equal education. In 1951 she was denied entrance to Topeka’s all-white elementary schools. She recalled being a “very young child when I started walking to school. I remember the walk as being very long at that time… it was very frightening to me…I remember walking, tears freezing up on my face, because I began to cry because it was so cold.”

The NAACP was seeking a case to challenge segregated schools and hers was the ticket. They sent their best, Thurgood Marshall, to argue the case. In 1954 the Supreme Court adjudicated Brown v. Topeka Board of Education. Marshall argued against decades of standing legal precedent from Plessy v. Ferguson, stating that separate was inherently unequal.

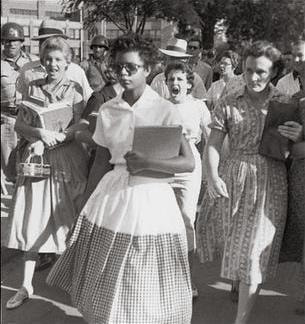

Marshall’s victory in the Supreme Court led to schools across the country desegregating. However, states in the south refused. Daisy Bates, the president of the Arkansas NAACP chapter, led the NAACP to sue the Little Rock school board after recruiting 9 students to integrate into the high school. In 1957, the Little Rock Nine were met with white violence and threats of lynching. Bates guided and prepared the students to face resistance and taunts, but the situation escalated to the point of real danger.

In the wake of the violence, President Dwight Eisenhower sent the famous 101st Airborne division to Little Rock. Soldiers occupied the school and protected the students for the entire school year.

Of course, Montgomery was only the beginning of the movement. Quietly in the courts a little girl named Linda Brown was fighting a battle for equal education. In 1951 she was denied entrance to Topeka’s all-white elementary schools. She recalled being a “very young child when I started walking to school. I remember the walk as being very long at that time… it was very frightening to me…I remember walking, tears freezing up on my face, because I began to cry because it was so cold.”

The NAACP was seeking a case to challenge segregated schools and hers was the ticket. They sent their best, Thurgood Marshall, to argue the case. In 1954 the Supreme Court adjudicated Brown v. Topeka Board of Education. Marshall argued against decades of standing legal precedent from Plessy v. Ferguson, stating that separate was inherently unequal.

Marshall’s victory in the Supreme Court led to schools across the country desegregating. However, states in the south refused. Daisy Bates, the president of the Arkansas NAACP chapter, led the NAACP to sue the Little Rock school board after recruiting 9 students to integrate into the high school. In 1957, the Little Rock Nine were met with white violence and threats of lynching. Bates guided and prepared the students to face resistance and taunts, but the situation escalated to the point of real danger.

In the wake of the violence, President Dwight Eisenhower sent the famous 101st Airborne division to Little Rock. Soldiers occupied the school and protected the students for the entire school year.

Ruby Bridges, Wikimedia Commons

Ruby Bridges, Wikimedia Commons

In 1960, Ruby Bridges was just six years old when she became the first Black student to integrate an elementary school. Ruby and her mother were escorted by four federal marshals to the school every day that year because of the violent mobs who would appear to protest the education of a child. Bridges later said she once saw a woman holding a black baby doll in a coffin.

The choice to integrate was hard on Ruby and her family. She spent her first day in the principal’s office, whites withdrew their children permanently, and only one teacher, Barbara Henry, a white Boston native, was willing to teach Ruby. Northerners sent money to support the family, but it was tough. Her dad lost his job and whites refused to do business with the family. Still, Ruby never missed a day of school.

Sit Ins and Freedom Rides:

In February 1960, college men and women staged sit-ins at Woolworth store lunch counters. Students sat peacefully for hours as they were refused service by nervous waitresses. Diane Nash Bevel was a leader within the student movement at Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee. Her family was horrified, and she was nervous, not wanting to go to jail, but she said, “When the time came, I went.”

Women, including Nash, were also active participants in the Freedom Rides. They rode interstate buses and attempted to integrate local restrooms, waiting areas, and restaurants. The Freedom Riders were brutally beaten and one of their buses was set afire. Riders were also imprisoned at Mississippi’s Parchman Prison, where they were subjected to brutal treatment. Nash knew that if they let the violence stop them the cause would be lost. She said, “We recognized that if the Freedom Ride was ended right then after all that violence, southern white racists would think that they could stop a project by inflicting enough violence on it… we wouldn’t have been able to have any kind of movement for voting rights, for buses, public accommodations or anything after that, without getting a lot of people killed first.”

The choice to integrate was hard on Ruby and her family. She spent her first day in the principal’s office, whites withdrew their children permanently, and only one teacher, Barbara Henry, a white Boston native, was willing to teach Ruby. Northerners sent money to support the family, but it was tough. Her dad lost his job and whites refused to do business with the family. Still, Ruby never missed a day of school.

Sit Ins and Freedom Rides:

In February 1960, college men and women staged sit-ins at Woolworth store lunch counters. Students sat peacefully for hours as they were refused service by nervous waitresses. Diane Nash Bevel was a leader within the student movement at Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee. Her family was horrified, and she was nervous, not wanting to go to jail, but she said, “When the time came, I went.”

Women, including Nash, were also active participants in the Freedom Rides. They rode interstate buses and attempted to integrate local restrooms, waiting areas, and restaurants. The Freedom Riders were brutally beaten and one of their buses was set afire. Riders were also imprisoned at Mississippi’s Parchman Prison, where they were subjected to brutal treatment. Nash knew that if they let the violence stop them the cause would be lost. She said, “We recognized that if the Freedom Ride was ended right then after all that violence, southern white racists would think that they could stop a project by inflicting enough violence on it… we wouldn’t have been able to have any kind of movement for voting rights, for buses, public accommodations or anything after that, without getting a lot of people killed first.”

Public Domain

Public Domain

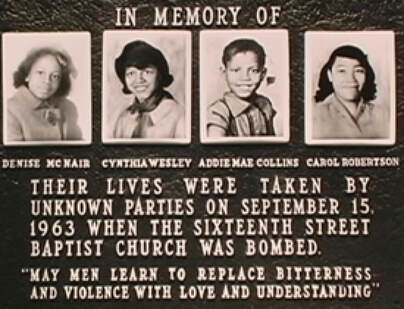

As we saw with Ruby Bridges, age was not a deterrent for white violence. In 1963, the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama was bombed by terrorists. The only victims were five young girls who had been in the basement, two of them sisters, gathered in the ladies room in their best dresses, happily chatting. One of the girls survived but lost her eye. Their deaths took Civil Rights international--with people all over the world arguing for the end of racism in America. The girls became martyrs to the movement, and the grief galvanized the movement, which at last solidified the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. But of course, though the Civil Rights Act was an important victory, it did not magically end prejudice in the US.

Viola Liuzzo, Wikimedia Commons

Viola Liuzzo, Wikimedia Commons

In the summer of 1964, students from northern colleges joined civil rights activists to organize voter registration drives in Mississippi. In spite of their efforts to register Black voters, white primaries and intimidation made it difficult for Black people to exercise political power. In response, Fannie Lou Hamer and others established the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party that challenged the regular party for seats at the 1964 Democratic Convention in Atlantic City. Unfortunately, the challengers lost their battle for representation and returned to Mississippi frustrated. In the process, many people were arrested. In one incident, white police officers forced two Black prisoners to savagely beat Hamer with loaded Blackjacks, and she almost died.

The violence and intimidation clearly continued. Women civil rights workers of all races were not immune from beatings, or murder. Viola Liuzzo, a white housewife from Detroit, joined Dr. King after witnessing the brutal “Bloody Sunday” march across the Edmund Pettus bridge on television. She attended the later completion of the march. Afterwards, as she shuttled other marchers back, she was ambushed and shot from a passing vehicle by members of the Ku Klux Klan. Civil Rights Activists considered her yet another martyr for their cause. Racists denigrated her–describing her as a sexually promiscuous woman who abandoned her family. If she had just stayed home, they argued, she would still be alive.

The violence and intimidation clearly continued. Women civil rights workers of all races were not immune from beatings, or murder. Viola Liuzzo, a white housewife from Detroit, joined Dr. King after witnessing the brutal “Bloody Sunday” march across the Edmund Pettus bridge on television. She attended the later completion of the march. Afterwards, as she shuttled other marchers back, she was ambushed and shot from a passing vehicle by members of the Ku Klux Klan. Civil Rights Activists considered her yet another martyr for their cause. Racists denigrated her–describing her as a sexually promiscuous woman who abandoned her family. If she had just stayed home, they argued, she would still be alive.

Corretta Scott King, Public Domain

Corretta Scott King, Public Domain

In 1967, the federal government intervened with Civil Rights again in the Supreme Court case Loving v. Virginia. Richard and Mildred Loving challenged Virginia’s Racial Integrity Act. The Act, which dated back to 1924, banned interracial marriage. The Lovings won in a unanimous ruling–the Court finding laws against interracial marriage unconstitutional–thus overturning all race-based marriage restrictions across the country.

Black Power and Nonviolence:

Many participants in the civil rights movement expressed frustration at the slow progress of the peaceful demonstrations. SNCC expelled its white members, asserting that it was time for Black rights to come from Black action. Stokley Carmichel articulated the idea of Black Power in 1966, and the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense was founded in the same year in reaction to the Assassination of Malcolm X. By the time Martin Luther King was assassinated in 1968 the Black panthers had roughly 2000 members around the country and were growing. However, not all Black people, including women, were convinced to depart from nonviolence.

Coretta Scott King was one such contrarian--even though peaceful protest had obviously been very hard on her family. When her husband Dr. King was attacked or hospitalized, she was the one in the hospital caring for and supporting him. Coretta was in the house when it was bombed in 1956 along with their children. She was often stuck between her father, who was concerned about her safety, and her husband who wanted her to be with him. She personally came under attack when the FBI mailed her tapes alleging her husband's affairs, intending to dismantle King's support system underneath him. Man, racists are desperate. In the aftermath of King’s assassination, she doubled down on nonviolence and became heavily involved in the civil rights movement. She founded the King Center for nonviolent social change and led as president and CEO.

But back to the Black Power movement. It did grow, despite being sometimes polarizing. Clearly, the violence against Black people topped the movement’s list of priorities. In 1968 the average age of a Panther was 19 and half were women. Female Panthers often worked 18-hour days to actualize the party vision. Women didn’t dominate headlines or get media sound bites, but they were the soul of daily operations and the community survival programs–particularly their medical programs (their clinics and sickle cell blood testing programs) and their breakfast programs.

Black Power and Nonviolence:

Many participants in the civil rights movement expressed frustration at the slow progress of the peaceful demonstrations. SNCC expelled its white members, asserting that it was time for Black rights to come from Black action. Stokley Carmichel articulated the idea of Black Power in 1966, and the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense was founded in the same year in reaction to the Assassination of Malcolm X. By the time Martin Luther King was assassinated in 1968 the Black panthers had roughly 2000 members around the country and were growing. However, not all Black people, including women, were convinced to depart from nonviolence.

Coretta Scott King was one such contrarian--even though peaceful protest had obviously been very hard on her family. When her husband Dr. King was attacked or hospitalized, she was the one in the hospital caring for and supporting him. Coretta was in the house when it was bombed in 1956 along with their children. She was often stuck between her father, who was concerned about her safety, and her husband who wanted her to be with him. She personally came under attack when the FBI mailed her tapes alleging her husband's affairs, intending to dismantle King's support system underneath him. Man, racists are desperate. In the aftermath of King’s assassination, she doubled down on nonviolence and became heavily involved in the civil rights movement. She founded the King Center for nonviolent social change and led as president and CEO.

But back to the Black Power movement. It did grow, despite being sometimes polarizing. Clearly, the violence against Black people topped the movement’s list of priorities. In 1968 the average age of a Panther was 19 and half were women. Female Panthers often worked 18-hour days to actualize the party vision. Women didn’t dominate headlines or get media sound bites, but they were the soul of daily operations and the community survival programs–particularly their medical programs (their clinics and sickle cell blood testing programs) and their breakfast programs.

Although the party had community building aims, it was not portrayed that way in the press. It was also under constant surveillance and attack by the police and FBI. On June 15, 1969, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover declared that “the Black Panther Party, without question, represents the greatest threat to internal security of the country.” By 1970, many of the party’s leaders had been imprisoned or killed in gun battles with police.

Angela Davis, a respected scholar and professor, was very active in Black Power. In 1970, she was accused of supplying guns to a group that staged an armed takeover of a California courtroom. She was kept in prison for more than a year, and then acquitted of all charges in 1972. Davis’s struggle against the legal system was a symbol of the continuing efforts by the government to repress unpopular views, especially when such views were held by Black women.

Angela Davis, a respected scholar and professor, was very active in Black Power. In 1970, she was accused of supplying guns to a group that staged an armed takeover of a California courtroom. She was kept in prison for more than a year, and then acquitted of all charges in 1972. Davis’s struggle against the legal system was a symbol of the continuing efforts by the government to repress unpopular views, especially when such views were held by Black women.

A Panther named Akua Njeri, then 19, was engaged to the charismatic Fred Hampton, the leader of the powerful Chicago chapter. On December 4, 1969, she was nine months pregnant when a group of police stormed into their apartment on Chicago’s West Side to execute a search warrant for illegal guns. They came in shooting and instantly killed one of the Panther men. Njeri woke to bullets flying past her and Hampton, but he was somehow still asleep. We now know he was drugged by an FBI informant within the Panther ranks. She recalled straddling Hampton’s body to protect him from the barrage of bullets, which only momentarily stopped when another person in the apartment yelled, “Stop shooting, stop shooting, we have a pregnant woman, pregnant sister in here!" By several accounts the officers then entered the bedroom and shot Hampton dead, point-blank. Njeri was jailed, supporters paid her bail, and she gave birth under extreme stress to her son Fred Hampton, Jr.

Sexism in the Panthers:

Despite being active in social reform and civil rights, the Panthers, like many other civil rights groups, were not immune to sexism. Party leaders favored promoting men members, sexualized women members, and had double standards. While in general the party adopted the free love movement and embraced diverse sexualities, some heterosexual male Panthers expected and demanded sexual favors from women. And some women definitely resented that.

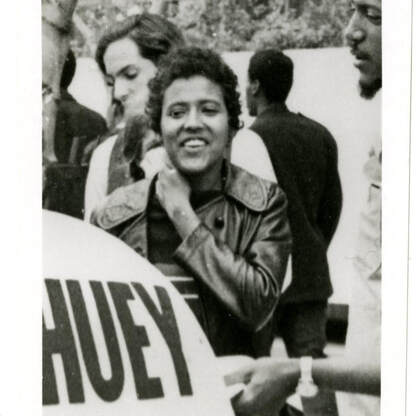

Only one woman became leader of the organization in its history, Elaine Brown in 1974. Her statement to the organization made her dominance clear, “I have all the guns and the money. I can withstand challenges from without and from within. ” Brown put women in key administrative positions, which made some men in the party upset. After a short service Brown left the party when a female administrator, Regina Davis, was beaten and hospitalized by members of the party at the approval of Huey Newton. “The beating of Regina would be taken as a clear signal that the words ‘Panther’ and ‘comrade’ had taken on gender connotations, denoting an inferiority in the female half of us.”

Conclusion:

The inequities both in the Panthers and the wider civil rights movement drove many women toward intersectional feminism. The Civil Rights Movement was an empowering but incredibly difficult time for Black women. The work of activists and countless protesters of all races brought about new legislation to end segregation, voter suppression, discriminatory employment, and housing practices. Yet today, so much still remains to be done.

By the end of this era, so much remained in question. How can social equality for people of color be achieved in this country? What effect did Black women have on improving sexism within Civil Rights ranks? Did women’s participation in the civil rights movement contribute to the emergence of second wave feminism?

Despite being active in social reform and civil rights, the Panthers, like many other civil rights groups, were not immune to sexism. Party leaders favored promoting men members, sexualized women members, and had double standards. While in general the party adopted the free love movement and embraced diverse sexualities, some heterosexual male Panthers expected and demanded sexual favors from women. And some women definitely resented that.

Only one woman became leader of the organization in its history, Elaine Brown in 1974. Her statement to the organization made her dominance clear, “I have all the guns and the money. I can withstand challenges from without and from within. ” Brown put women in key administrative positions, which made some men in the party upset. After a short service Brown left the party when a female administrator, Regina Davis, was beaten and hospitalized by members of the party at the approval of Huey Newton. “The beating of Regina would be taken as a clear signal that the words ‘Panther’ and ‘comrade’ had taken on gender connotations, denoting an inferiority in the female half of us.”

Conclusion:

The inequities both in the Panthers and the wider civil rights movement drove many women toward intersectional feminism. The Civil Rights Movement was an empowering but incredibly difficult time for Black women. The work of activists and countless protesters of all races brought about new legislation to end segregation, voter suppression, discriminatory employment, and housing practices. Yet today, so much still remains to be done.

By the end of this era, so much remained in question. How can social equality for people of color be achieved in this country? What effect did Black women have on improving sexism within Civil Rights ranks? Did women’s participation in the civil rights movement contribute to the emergence of second wave feminism?

Draw your own conclusions

|

Learn how to teach with inquiry.

Many of these lesson plans were sponsored in part by the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources Eastern Region Program, coordinated by Waynesburg University, the History and Social Studies Education Faculty at Plymouth State University, and the Patrons of the Remedial Herstory Project. |

Lesson Plans from Other Organizations

- The National Women's History Museum has lesson plans on women's history.

- The Guilder Lehrman Institute for American History has lesson plans on women's history.

- The NY Historical Society has articles and classroom activities for teaching women's history.

- Unladylike 2020, in partnership with PBS, has primary sources to explore with students and outstanding videos on women from the Progressive era.

- The Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media has produced recommendations for teaching women's history with primary sources and provided a collection of sources for world history. Check them out!

- The Stanford History Education Group has a number of lesson plans about women in US History.

Period Specific Lesson Plans from Other Organizations

- Rosa Parks:

- Teaching Tolerance: Most history textbooks include a section about Rosa Parks in the chapter on the modern civil rights movement. However, Parks is only one among many African-American women who have worked for equal rights and social justice. This series introduces four of those activists who may be unfamiliar to students.

- Lesson 1, Maya Angelou, focuses on questions of identity as students read and analyze Angelou’s inspirational poem “Still I Rise” and apply its message to their own lives. Students learn how Maya Angelou overcame hardship and discrimination to find her own voice and to influence others to believe in themselves and use their voices for positive change.

- Lesson 2, Mary Church Terrell, focuses on questions of diversity among turn of the 20th century African Americans. Students read and analyze an 1898 speech by the founding president of the National Association of Colored Women about the class differences within African-American communities and the NACW’s philosophy of “lifting as we climb.”

- Lesson 3, Mary McLeod Bethune, focuses on questions of justice. Students read an interview with this prominent African-American educator and learn about how her personal experience of discrimination motivated her to open a school for African-American students in Florida and to devote her life to the struggle for equality.

- Lesson 4, Marian Wright Edelman, focuses on questions of activism. Students read a commencement speech given by this well-known founder of the Children’s Defense Fund and learn how Edelman has dedicated her life to "paying it forward" and rising above circumstances to make lives better for others. They are then encouraged to apply lessons from the speech to their own lives as they identify and implement opportunities to help improve the lives of those in their school or community.

- Each lesson includes a central text and provides strategies for reading and understanding that text. Students are encouraged to make connections between the texts and their own experiences and to take action against the inequities they identify.

- PBS: After the Civil War and through the Civil Rights era of the 1950s, racial segregation laws made life for many African Americans extremely difficult. Rosa Parks—long-standing civil rights activist and author—is best known for her refusal to give up her seat to a white bus passenger, sparking the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Through two primary source activities and a short video, students will learn about Parks’ lifelong commitment to the Civil Rights Movement.

- Scholastic: This unique activity introduces Rosa Parks and provides an opportunity for students to respond to her experience in writing. As students learn about "the Mother of the Modern-Day Civil Rights Movement," they see how individuals have shaped American history.

- National Women’s History Museum: How has the activism of Native American women contributed to fights for the liberation of Native people and communities? Is a lesson plan by the NWHM that helps students reconsider the role of women in native history, the central role they played in challenging how indigenous history was taught, and their activism in the 1960s.

- Zinn History Education Group: In this lesson plan students assume the roles of characters working in and against the Black panther party. Many of the roles are female, showing the integral role women played in the movement.

- C3 Teachers: This inquiry leads students through an investigation of the education system in the United States, focusing on the extent to which systemic racism continues to plague modern schooling. Students investigate schooling before and after the Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court case in order to evaluate the impact and effectiveness, or “success,” of school desegregation.

- National History Day: Fannie Lou Hamer (1917-1977) was born Fannie Lou Townsend on October 6, 1917, in Montgomery County, Mississippi. She later moved to Sunflower County where she began sharecropping at the age of six. She married Perry Hammer in 1944 and moved to a plantation in Ruleville, Mississippi. Due to her eighth grade education, she was asked by the plantation owner to serve as the timekeeper, which she did for 18 years. Hamer traveled, unsuccessfully, to Indianola to attempt to vote in 1962. Upon returning to the plantation, she lost her job, forcing her family to find somewhere else to live and work. In 1963, Hamer was named field secretary of the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). That fall, while traveling back from a training session, she was arrested and brutally beaten in jail. Through her tireless efforts, Hamer was appointed vice-chair of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP). The following year, the 1965 Voting Rights Act was passed. This pivotal legislation would not have been possible were it not for the efforts of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party.

- National History Day: Marian Anderson (1897-1993) discovered the power of her voice at a young age. The Philadelphia native possessed a unique contralto range that helped her become an internationally acclaimed talent. Despite being denied entry into several conservatories because of her race, Anderson’s private training with top vocal instructors led her to performances from New York’s Carnegie Hall to Paris. She entertained several European monarchs and was the first African American to sing at the White House when she accepted an invitation from Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt in 1936. Throughout her career she dealt with segregation in America, and in 1939 the Daughters of the American Revolution refused to allow her to perform at Constitution Hall in Washington, D.C. A national backlash to this decision, spearheaded by Eleanor Roosevelt’s resignation from the DAR in protest, led to Anderson singing for 75,000 people on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial on Easter Sunday 1939. After this key moment for civil rights, she continued her groundbreaking career, along the way becoming the first African American to perform at the New York Metropolitan Opera in 1955. In 1963, she sang at the March on Washington and received the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

- Teaching Tolerance: Most history textbooks include a section about Rosa Parks in the chapter on the modern civil rights movement. However, Parks is only one among many African-American women who have worked for equal rights and social justice. This series introduces four of those activists who may be unfamiliar to students.

- LGBTQ+ Rights:

- National Women’s History Museum: Should LGBTQ history be required by all states? This lesson seeks to explore the Stonewall Riots, the media interpretation of them, and inclusion and exclusion in the LGBTQ movement through the life of Marsha P. Johnson, including the connections to the present day. Students will examine news articles from the time, reflections from trans activists, and explore the ways the impacts of intersectionality on the LGBTQ community. Through a set of activities, students will explore how Stonewall has been understood and some of the unsung heroes, ultimately seeking to ask why they were unsung. As a summative assessment, students will complete a writing exercise in which they seek to connect the debate over the film Stonewall to what they have learned in class and reflect on what they have learned.

- Teaching Tolerance: Most history textbooks lack inclusion of the significant contributions LGBT African-Americans made to the civil rights movement. This series introduces students to four LGBT people of African descent with whom they may not be familiar, yet who were indispensable to the ideas, strategies and activities that made the civil rights movement a successful political and social revolution.

- Stanford History Education Group: In the early hours of June 28, 1969, a police raid of the Stonewall Inn exploded into a riot when patrons of the LGBT bar resisted arrest and clashed with police. The Stonewall Riots are widely considered to be the start of the LGBT rights movement in the United States. In this lesson, students analyze four documents to answer the question: What caused the Stonewall Riots?

Jo Ann Robinson: to the Mayor of Montgomery, Alabama

This letter from the Women's Political Council to the Mayor of Montgomery, Alabama, threatens a bus boycott by the city's African Americans if demands for fair treatment are not met.

Dear Sir:

The Women’s Political Council is very grateful to you and the City Commissioners for the hearing you allowed our representative during the month of March, 1954, when the “city-bus-fare-increase case” was being reviewed. There were several things the Council asked for:

However, the same practices in seating and boarding the bus continue. Mayor Gayle, three-fourths of the riders of these public conveyances are Negroes. If Negroes did not patronize them, they could not possibly operate. More and more of our people are already arranging with neighbors and friends to ride to keep from being insulted and humiliated by bus drivers… Please consider this plea, and if possible, act favorably upon it, for even now plans are being made to ride less, or not at all, on our busses. We do not want this.

Respectfully yours,

The Women’s Political Council, Jo Ann Robinson, President

Robinson, Jo Ann. “African-American Women Threaten a Bus Boycott in Montgomery.” HERB: Resources for Teachers. Last modified https://herb.ashp.cuny.edu/items/show/693.

Questions:

1. Who is Jo Ann Robinson?

2. Why does she want to boycott the busses?

3. Why is the date of this document significant?

Dear Sir:

The Women’s Political Council is very grateful to you and the City Commissioners for the hearing you allowed our representative during the month of March, 1954, when the “city-bus-fare-increase case” was being reviewed. There were several things the Council asked for:

- A city law that would make it possible for Negroes to sit from back toward front, and whites from front toward back until all the seats are taken.

- That Negroes not be asked or forced to pay fare at front and go to the rear of the bus to enter.

- That busses stop at every corner in residential sections occupied by Negroes as they do in communities where whites reside.

However, the same practices in seating and boarding the bus continue. Mayor Gayle, three-fourths of the riders of these public conveyances are Negroes. If Negroes did not patronize them, they could not possibly operate. More and more of our people are already arranging with neighbors and friends to ride to keep from being insulted and humiliated by bus drivers… Please consider this plea, and if possible, act favorably upon it, for even now plans are being made to ride less, or not at all, on our busses. We do not want this.

Respectfully yours,

The Women’s Political Council, Jo Ann Robinson, President

Robinson, Jo Ann. “African-American Women Threaten a Bus Boycott in Montgomery.” HERB: Resources for Teachers. Last modified https://herb.ashp.cuny.edu/items/show/693.

Questions:

1. Who is Jo Ann Robinson?

2. Why does she want to boycott the busses?

3. Why is the date of this document significant?

Remedial Herstory Editors. "21. WOMEN AND THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT." The Remedial Herstory Project. November 20, 2022. www.remedialherstory.com.

Primary AUTHOR: |

Kelsie Brook Eckert

|

Primary ReviewerS: |

Dr. Barbara Tischler

|

Consulting TeamKelsie Brook Eckert, Project Director

Coordinator of Social Studies Education at Plymouth State University Dr. Barbara Tischler, Consultant Professor of History Hunter College and Columbia University Dr. Alicia Gutierrez-Romine, Consultant Assistant Professor of History at La Sierra University Jacqui Nelson, Consultant Teaching Lecturer of Military History at Plymouth State University Dr. Deanna Beachley Professor of History and Women's Studies at College of Southern Nevada |

EditorsAlice Stanley

ReviewersColonial

Dr. Margaret Huettl Hannah Dutton Dr. John Krueckeberg 19th Century Dr. Rebecca Noel Michelle Stonis, MA Annabelle L. Blevins Pifer, MA Cony Marquez, PhD Candidate 20th Century Dr. Tanya Roth Dr. Jessica Frazier Mary Bezbatchenko, MA Dr. Alicia Gutierrez-Romine Matthew Cerjak |

|

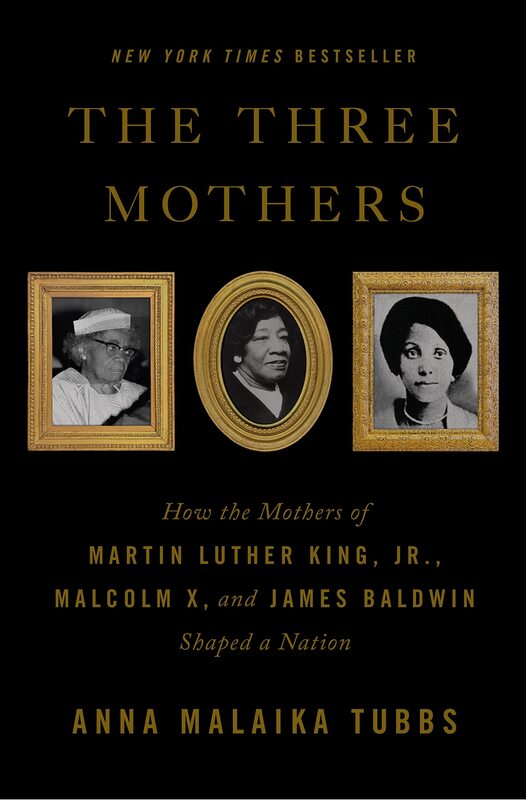

Berdis Baldwin, Alberta King, and Louise Little were all born at the beginning of the 20th century and forced to contend with the prejudices of Jim Crow as Black women. These women used their strength and motherhood to push their children toward greatness, all with a conviction that every human being deserves dignity and respect despite the rampant discrimination they faced.

|

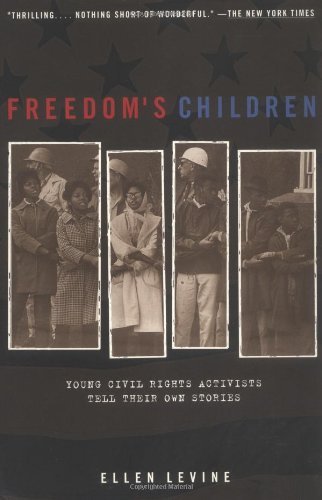

In this inspiring collection of true stories, thirty African-Americans who were children or teenagers in the 1950s and 1960s talk about what it was like for them to fight segregation in the South-to sit in an all-white restaurant and demand to be served, to refuse to give up a seat at the front of the bus, to be among the first to integrate the public schools, and to face violence, arrest, and even death for the cause of freedom.

|

In this groundbreaking and important book, Danielle McGuire writes about the rape in 1944 of a twenty-four-year-old mother and sharecropper, Recy Taylor, who strolled toward home after an evening of singing and praying at the Rock Hill Holiness Church in Abbeville, Alabama. Seven white men, armed with knives and shotguns, ordered the young woman into their green Chevrolet, raped her, and left her for dead. The president of the local NAACP branch office sent his best investigator and organizer—Rosa Parks—to Abbeville. In taking on this case, Parks launched a movement that exposed a ritualized history of sexual assault against Black women and added fire to the growing call for change.

|

|

Organized around a rich blend of oral histories, Going South follows a group of Jewish women―come of age in the shadow of the Holocaust and deeply committed to social justice―who put their bodies and lives on the line to fight racism. Actively rejecting the post-war idyll of suburban, Jewish, middle-class life, these women were deeply influenced by Jewish notions of morality and social justice. Many thus perceived the call of the movement as positively irresistible.

|

In Lighting the Fires of Freedom Janet Dewart Bell shines a light on women's all-too-often overlooked achievements in the Movement. Through wide-ranging conversations with nine women, several now in their nineties with decades of untold stories, we hear what ignited and fueled their activism, as Bell vividly captures their inspiring voices. Lighting the Fires of Freedom offers these deeply personal and intimate accounts of extraordinary struggles for justice that resulted in profound social change, stories that are vital and relevant today.

|

Unbought and Unbossed is Shirley Chisholm's account of her remarkable rise from young girl in Brooklyn to America's first African-American Congresswoman. She shares how she took on an entrenched system, gave a public voice to millions, and sets the stage for her trailblazing bid to be the first woman and first African-American President of the United States.

|

|

On June 28, 1969, the Stonewall Inn, a gay bar in New York's Greenwich Village, was raided by police. But instead of responding with the typical compliance the NYPD expected, patrons and a growing crowd decided to fight back. The five days of rioting that ensued changed forever the face of gay and lesbian life.

|

Before John Glenn orbited the earth, or Neil Armstrong walked on the moon, a group of dedicated female mathematicians known as “human computers” used pencils, slide rules and adding machines to calculate the numbers that would launch rockets, and astronauts, into space.

|

Norman tells the dramatic story of fifty women—members of the Army, Navy, and Air Force Nurse Corps—who went to war, working in military hospitals, aboard ships, and with air evacuation squadrons during the Vietnam War. Here, in a moving narrative, the women talk about why they went to war, the experiences they had while they were there, and how war affected them physically, emotionally, and spiritually.

|

|

At the end of a sweltering summer shaped by the tragic assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr., and Bobby Kennedy, race riots, political protests, and the birth of Black power, three coeds from New York City—Zelda Livingston, Veronica Cook, and Daphne Brooks—pack into Veronica’s new Ford Fairlane convertible, bound for Atlanta and their last year at Spelman College.

|

It is the summer of 1964. In Tupelo, Mississippi, the town of Elvis’s birth, tensions are mounting over civil-rights demonstrations occurring ever more frequently–and violently–across the state. But in Paige Dunn’s small, ramshackle house, there are more immediate concerns. Challenged by the effects of the polio, Paige is determined to live as normal a life as possible and to raise her daughter, Diana.

|

Montgomery, Alabama, 1973. Fresh out of nursing school, Civil Townsend intends to make a difference, especially in her African American community. At the Montgomery Family Planning Clinic, she hopes to help women shape their destinies, to make their own choices for their lives and bodies.

|

How to teach with Films:

Remember, teachers want the student to be the historian. What do historians do when they watch films?

- Before they watch, ask students to research the director and producers. These are the source of the information. How will their background and experience likely bias this film?

- Also, ask students to consider the context the film was created in. The film may be about history, but it was made recently. What was going on the year the film was made that could bias the film? In particular, how do you think the gains of feminism will impact the portrayal of the female characters?

- As they watch, ask students to research the historical accuracy of the film. What do online sources say about what the film gets right or wrong?

- Afterward, ask students to describe how the female characters were portrayed and what lessons they got from the film.

- Then, ask students to evaluate this film as a learning tool. Was it helpful to better understand this topic? Did the historical inaccuracies make it unhelpful? Make it clear any informed opinion is valid.

|

|

|

Till tells the story of Emmett Till from the perspective of his mother, who made the controversial choice to publicly display his body in Chicago after he was brutally lynched in Mississippi. She fought to secure his legacy and ensure he did not die in vain.

IMDB |

|

|

Jackie is a biopic about Jackie Kennedy's experience after the assassination of her husband as she shaped his legacy.

IMDB |

|

|

|

Bibliography

Brown, Deneen L. “The first and only woman to lead the Black Panther Party: ‘I have all the guns and money’.” The Lily News. Last modified January 12, 2018. https://www.thelily.com/the-first-and-only-woman-to-lead-the-black-panther-party/.

Collins, Gail, America's Women: Four Hundred Years of Dolls, Drudges, Helpmates, and Heroines. New York, William Morrow, 2003.

DuBois, Ellen Carol, 1947-. Through Women's Eyes : an American History with Documents. Boston :Bedford/St. Martin's, 2005.Indians Editors. “NATIVE AMERICAN WOMEN.” Indians. N.D. http://indians.org/articles/Native-american-women.html.

Darville, Sarah. “In her own words: Remembering Linda Brown, who was at the center of America’s school segregation battles.” Chalk Beat. March 27, 2018. https://www.chalkbeat.org/2018/3/27/21104642/in-her-own-words-remembering-linda-brown-who-was-at-the-center-of-america-s-school-segregation-battle.

Dixon, Janelle Harris. “The Rank and File Women of the Black Panther Party and Their Powerful Influence.” Smithsonian Magazine. Last modified MARCH 4, 2019.

Dolak, Kevin. “What Happened To Deborah Johnson After The Killing of Black Panther Party Leader Fred Hampton?” True Crime Buzz. Last modified February 11, 2021. https://www.oxygen.com/true-crime-buzz/akua-njeri-nee-deborah-johnson-carried-on-fred-hamptons-legacy.

History Editors. “Brown v. Board of Education.” History. January 11, 2022. https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/brown-v-board-of-education-of-topeka.

National Archives Editors. “Women in Black Power.” National Archives. N.D. https://www.archives.gov/research/african-americans/black-power/women.

People’s History Podcast. “Women in the Black Panther Party.” https://anchor.fm/zinn-ed-project/episodes/Women-in-the-Black-Panther-Party-egek69/a-a2l7p92.

Robinson, Jo Ann. “Local Activists Call for a Bus Boycott in Montgomery,” SHEC: Resources for Teachers, accessed January 26, 2022, https://shec.ashp.cuny.edu/items/show/1140.

Sewell, Chan. “Recy Taylor, Who Fought for Justice After a 1944 Rape, Dies at 97.” New York Times. December 29, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/29/obituaries/recy-taylor-alabama-rape-victim-dead.html.

Spencer, Robyn Ceanne. “Engendering the Black Freedom Struggle: Revolutionary Black Womanhood and the Black Panther Party in the Bay Area, California.” Journal of Women's History 20, no. 1 (2008): 90–113. doi:10.1353/JOWH.2008.0006.

Zinn, Howard. A People’s History of the United States. Harper Collins Publishing: New York, NY, 1999.

Ware, Susan. American Women’s History: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

Collins, Gail, America's Women: Four Hundred Years of Dolls, Drudges, Helpmates, and Heroines. New York, William Morrow, 2003.

DuBois, Ellen Carol, 1947-. Through Women's Eyes : an American History with Documents. Boston :Bedford/St. Martin's, 2005.Indians Editors. “NATIVE AMERICAN WOMEN.” Indians. N.D. http://indians.org/articles/Native-american-women.html.

Darville, Sarah. “In her own words: Remembering Linda Brown, who was at the center of America’s school segregation battles.” Chalk Beat. March 27, 2018. https://www.chalkbeat.org/2018/3/27/21104642/in-her-own-words-remembering-linda-brown-who-was-at-the-center-of-america-s-school-segregation-battle.

Dixon, Janelle Harris. “The Rank and File Women of the Black Panther Party and Their Powerful Influence.” Smithsonian Magazine. Last modified MARCH 4, 2019.

Dolak, Kevin. “What Happened To Deborah Johnson After The Killing of Black Panther Party Leader Fred Hampton?” True Crime Buzz. Last modified February 11, 2021. https://www.oxygen.com/true-crime-buzz/akua-njeri-nee-deborah-johnson-carried-on-fred-hamptons-legacy.

History Editors. “Brown v. Board of Education.” History. January 11, 2022. https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/brown-v-board-of-education-of-topeka.

National Archives Editors. “Women in Black Power.” National Archives. N.D. https://www.archives.gov/research/african-americans/black-power/women.

People’s History Podcast. “Women in the Black Panther Party.” https://anchor.fm/zinn-ed-project/episodes/Women-in-the-Black-Panther-Party-egek69/a-a2l7p92.

Robinson, Jo Ann. “Local Activists Call for a Bus Boycott in Montgomery,” SHEC: Resources for Teachers, accessed January 26, 2022, https://shec.ashp.cuny.edu/items/show/1140.

Sewell, Chan. “Recy Taylor, Who Fought for Justice After a 1944 Rape, Dies at 97.” New York Times. December 29, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/29/obituaries/recy-taylor-alabama-rape-victim-dead.html.

Spencer, Robyn Ceanne. “Engendering the Black Freedom Struggle: Revolutionary Black Womanhood and the Black Panther Party in the Bay Area, California.” Journal of Women's History 20, no. 1 (2008): 90–113. doi:10.1353/JOWH.2008.0006.

Zinn, Howard. A People’s History of the United States. Harper Collins Publishing: New York, NY, 1999.

Ware, Susan. American Women’s History: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.