8. 100 BCE - 100 CE Women and the Han Empire

|

Women had a prominent role in leadership in Asia, mainly in China during the Han Dynasty. The spotlight is placed among a group of powerful women including the first female monarch, an empress, and a court historian. Learn about how each played a role in their place of power or lived within that environment and what their lives were like during the Han Dynasty.

|

|

Han Dynasty Statue, Wikimedia Commons

Han Dynasty Statue, Wikimedia Commons

While the Roman Empire thrived in Eurasia, the Han Dynasty came to power in China and solidified a Chinese Empire for centuries to come. The dynasty succeeded the short-lived Qin dynasty and a period of violent conflict. The empire was known for its civil service and government structure, the nationalization of the private salt and iron industries, inventions, and adoption of Confucianism. But did these advances improve the lives of women that lived there?

In many ways the Han Empire was similar to the Roman Empire. To understand the impact the Han had on women, it would also be helpful if you viewed Asian Philosophies and Women’s Place, because, as you will see, the philosophy of Confucianism had an adverse effect on women in China for centuries.

China

The Han leadership realized that philosophies can be powerful tools for solidifying an empire. Confucius’s writings became more accepted and eventually Emperor Wu Di (reigned 141–87 BCE) made Confucianism the official state philosophy. Confucian schools were established to teach Confucian ethics and spread the philosophy to the masses.

For women, this had a lasting effect on the structure and expectations of their lives. “Filial piety,” or devotion to family, is central to Confucian thinking. Devotion included ancestor worship, submission to parental, royal, or government authority.

Confucian philosophy required that women lived subjugated lives. Women could not earn money outside the home and were expected to leave their family to join their spouses when they married. Many baby girls were abandoned shortly after birth, a practice called “infanticide.” A woman had no path to divorce unless her husband mistreated her father, while a husband could divorce his wife if she failed to bear a son, was unfaithful, lacked filial piety to the husband's parents, suffered from a virulent or infectious disease, or even talked too much. The only protection given to a wife was that she could not be divorced if she had no family to return to. Consequently, in practice, divorce was not as common as these grounds might suggest. By tradition, widows were strongly advised not to remarry, leaving women’s options in life very limited.

In many ways the Han Empire was similar to the Roman Empire. To understand the impact the Han had on women, it would also be helpful if you viewed Asian Philosophies and Women’s Place, because, as you will see, the philosophy of Confucianism had an adverse effect on women in China for centuries.

China

The Han leadership realized that philosophies can be powerful tools for solidifying an empire. Confucius’s writings became more accepted and eventually Emperor Wu Di (reigned 141–87 BCE) made Confucianism the official state philosophy. Confucian schools were established to teach Confucian ethics and spread the philosophy to the masses.

For women, this had a lasting effect on the structure and expectations of their lives. “Filial piety,” or devotion to family, is central to Confucian thinking. Devotion included ancestor worship, submission to parental, royal, or government authority.

Confucian philosophy required that women lived subjugated lives. Women could not earn money outside the home and were expected to leave their family to join their spouses when they married. Many baby girls were abandoned shortly after birth, a practice called “infanticide.” A woman had no path to divorce unless her husband mistreated her father, while a husband could divorce his wife if she failed to bear a son, was unfaithful, lacked filial piety to the husband's parents, suffered from a virulent or infectious disease, or even talked too much. The only protection given to a wife was that she could not be divorced if she had no family to return to. Consequently, in practice, divorce was not as common as these grounds might suggest. By tradition, widows were strongly advised not to remarry, leaving women’s options in life very limited.

Confucius, Wikimedia Commons

Confucius, Wikimedia Commons

Confucianism solidified women’s second-class status and reinforced prohibition on women’s formal education. Confucianism locked women into perpetual slavery to their families. One scholar wrote, “Few people teach their daughters to read and write nowadays for fear that they might become over ambitious.”

Women of lower status, such as farmer's wives, spent significantly more time out of the home, as they were expected to work in the fields, especially in regions where rice was the major staple crop. Many farmers did not own their own land but worked it as tenants, and their wives were, on occasion, subject to abuse from landowners. Women wer

forced into prostitution in times of drought or crop failure. Prostitution was part of town and city life, with officials and merchants frequenting houses where prostitutes plied their trade for the purposes of their entertainment.

Women worked in the home weaving silk and caring for the silkworms that produced it. Textile work was valuable to the family’s income. Some were called upon, like men, to perform the labor service which served as a form of taxation in many periods in ancient China.

Women of lower status, such as farmer's wives, spent significantly more time out of the home, as they were expected to work in the fields, especially in regions where rice was the major staple crop. Many farmers did not own their own land but worked it as tenants, and their wives were, on occasion, subject to abuse from landowners. Women wer

forced into prostitution in times of drought or crop failure. Prostitution was part of town and city life, with officials and merchants frequenting houses where prostitutes plied their trade for the purposes of their entertainment.

Women worked in the home weaving silk and caring for the silkworms that produced it. Textile work was valuable to the family’s income. Some were called upon, like men, to perform the labor service which served as a form of taxation in many periods in ancient China.

Han Dynasty Statue of a Servant Girl, Wikimedia Commons

Han Dynasty Statue of a Servant Girl, Wikimedia Commons

Although Chinese men usually had only one wife, they openly made use of courtesans and invited concubines to live permanently in the family home. Concubines might also be used to provide a family with the all-important male heir when the wife only produced daughters. The concubine and her offspring did not have the same legal status of the wife and her children. The number of concubines in the household was limited by the husband's means. A wife was expected never to show any jealousy toward her husband's concubines, as that was grounds for divorce. The Han believed there was a particularly nasty corner of hell awaiting jealous wives. Concubines usually came from the lower classes and entered the households of the wealthier families in society. And while sexual activity was certainly present, concubines were more like servants. This Eastern Han funeral stele for a concubine presents an interesting record of their duties:

“When she entered the household, she was diligent in care and ordered our familial way, treating all our ancestors as lofty. She sought good fortune without straying, her conduct omitting or adding nothing. Keeping herself frugal, she spun thread, and planted profitable crops in the orchards and gardens. She respected the legal wife and instructed the children, rejecting arrogance, never boasting of her kindnesses. The three boys and two girls kept quiet within the women's apartments. She made the girls submissive to rituals, while giving the boys power. Her chastity exceeded that of ancient times, and her guidance was not oppressive. All our kin were harmonious and close, like leaves attached to the tree” (Lewis, 170-171).

“When she entered the household, she was diligent in care and ordered our familial way, treating all our ancestors as lofty. She sought good fortune without straying, her conduct omitting or adding nothing. Keeping herself frugal, she spun thread, and planted profitable crops in the orchards and gardens. She respected the legal wife and instructed the children, rejecting arrogance, never boasting of her kindnesses. The three boys and two girls kept quiet within the women's apartments. She made the girls submissive to rituals, while giving the boys power. Her chastity exceeded that of ancient times, and her guidance was not oppressive. All our kin were harmonious and close, like leaves attached to the tree” (Lewis, 170-171).

Han Women, Wikimedia Commons

Han Women, Wikimedia Commons

Upper-class women were more often found in urban areas than in the countryside. Like many other locations, upper-class women’s lives were more strictly controlled than those of any other social group. Expected to remain within the inner chambers of the family home, they had very limited freedom of movement. Within the home, women had significant responsibilities, which included management of the household finances and the education of her children, but this did not mean they were the head of the family. Elite women had large dowries that were considered her property and could be leveraged in family disputes.

Confucian-Han women distinguished themselves from the pastoralists and rural poor by remaining secluded and passive. One Confucian writer described the “backward” ways of the northern pastoralists stating, “In the north of the yellow river it is usually the wife who runs the household. She will not dispense with good clothing or expensive jewelry. Her husband has to settle for old horses and sickly servants. The traditional niceties between husband and wife are seldom observed, and from time to time he even has to put up with her insults."

It is from these women that we have the most specific details of their lives. Elite women had proximity to male authors so their stories were often recorded.

Confucian-Han women distinguished themselves from the pastoralists and rural poor by remaining secluded and passive. One Confucian writer described the “backward” ways of the northern pastoralists stating, “In the north of the yellow river it is usually the wife who runs the household. She will not dispense with good clothing or expensive jewelry. Her husband has to settle for old horses and sickly servants. The traditional niceties between husband and wife are seldom observed, and from time to time he even has to put up with her insults."

It is from these women that we have the most specific details of their lives. Elite women had proximity to male authors so their stories were often recorded.

Sri Lanka

The first recorded female monarch in Asia was Anula of Sri Lanka, who ruled well outside the influence of China. Her reign left important lessons about female leadership. Her rule was recorded in a negative light– as most female rulers were characterized.

She ruled an island kingdom south of India in modern day Sri Lanka. According to historical records, this kingdom was established around 500 BCE and lasted until 1000 CE. Everything we know about the kingdom and Anula was recorded in the Mahavamsa, a historical chronicle.

According to legend, the dynasty from which Anula rose was founded by an exiled Indian prince who stumbled on the island with his followers. In the first century one of his descendants, an “evildoer,” according to the chronicle, ruled for 12 years and was murdered with poison by his concubine: Anula. Anula then went on to murder the new king and replace him with a palace guard who was her lover as king… who… she also had murdered.

Anula went on to have a series of lovers whom she positioned as king, only to have them poisoned after a short rule. The chronicler, like most writers, emphasized Anula’s sexual promiscuity, common of male rulers, rather than the politics of the time and perhaps the ineptitude of these men. Eventually, she just took the throne. Anula ruled for just four months and was either killed and burned on a pyre, or burned alive in her palace in a military coup.

The first recorded female monarch in Asia was Anula of Sri Lanka, who ruled well outside the influence of China. Her reign left important lessons about female leadership. Her rule was recorded in a negative light– as most female rulers were characterized.

She ruled an island kingdom south of India in modern day Sri Lanka. According to historical records, this kingdom was established around 500 BCE and lasted until 1000 CE. Everything we know about the kingdom and Anula was recorded in the Mahavamsa, a historical chronicle.

According to legend, the dynasty from which Anula rose was founded by an exiled Indian prince who stumbled on the island with his followers. In the first century one of his descendants, an “evildoer,” according to the chronicle, ruled for 12 years and was murdered with poison by his concubine: Anula. Anula then went on to murder the new king and replace him with a palace guard who was her lover as king… who… she also had murdered.

Anula went on to have a series of lovers whom she positioned as king, only to have them poisoned after a short rule. The chronicler, like most writers, emphasized Anula’s sexual promiscuity, common of male rulers, rather than the politics of the time and perhaps the ineptitude of these men. Eventually, she just took the throne. Anula ruled for just four months and was either killed and burned on a pyre, or burned alive in her palace in a military coup.

Public Domain

Public Domain

Empress of Han

While not the first in Asia, Lü Zhi, was the first and most notable female Empress Consort of the Han Dynasty. By surviving accounts, she was, like Anula, a vicious woman. She and Emperor Gaozu were a formidable pair: he had a good eye for talent and recruited experts to guide him, she a ruthless defender of his rule. In the early years of the empire, she demonstrated skills as an administrator and established important political connections. After the empire was secured and enemies of the Han defeated, she assassinated two of the generals who had elevated her husband to his position.

Lü Zhi had two children, a daughter Yuan and a son, Huidi, but her position was still tenuous because she had a whole harem of her husband's concubines and their sons to contend with. At any moment, favor could shift. Her husband was particularly fond of his concubine, Lady Qi and their son Liu Ruyi, giving him lands and wealth. But the Emperor was convinced to maintain the line of succession. When Emperor Gaozu died, Huidi became the new emperor and Lü Zhi became Empress Dowager, a regent for her young son who wielded incredible power.

Lü Zhi controlled the Empire with harsh cruelty. She executed rivals of her son, including sons within her husband's former harem, in order to consolidate her power, but it took time to coax Liu Ruyi out of his estate. Finally he came to her palace where she promptly had him poisoned.

While terrible, the fate of his mother, Lady Qi was even worse. Lü Zhi ordered her soldiers to imprison Lady Qi in a pigsty, pull out her tongue, blind her, and then chop off all her limbs. Disgusted with his mother, Huidi withdrew from imperial management– leaving even more power in her hands. When he died, she put another infant in power, then another. She ruled the Han Empire as regent for about fifteen years. While Lü Zhi was ruthless in her ambition, she ushered in a time of stability and is said to have improved the lives of the poor.

While not the first in Asia, Lü Zhi, was the first and most notable female Empress Consort of the Han Dynasty. By surviving accounts, she was, like Anula, a vicious woman. She and Emperor Gaozu were a formidable pair: he had a good eye for talent and recruited experts to guide him, she a ruthless defender of his rule. In the early years of the empire, she demonstrated skills as an administrator and established important political connections. After the empire was secured and enemies of the Han defeated, she assassinated two of the generals who had elevated her husband to his position.

Lü Zhi had two children, a daughter Yuan and a son, Huidi, but her position was still tenuous because she had a whole harem of her husband's concubines and their sons to contend with. At any moment, favor could shift. Her husband was particularly fond of his concubine, Lady Qi and their son Liu Ruyi, giving him lands and wealth. But the Emperor was convinced to maintain the line of succession. When Emperor Gaozu died, Huidi became the new emperor and Lü Zhi became Empress Dowager, a regent for her young son who wielded incredible power.

Lü Zhi controlled the Empire with harsh cruelty. She executed rivals of her son, including sons within her husband's former harem, in order to consolidate her power, but it took time to coax Liu Ruyi out of his estate. Finally he came to her palace where she promptly had him poisoned.

While terrible, the fate of his mother, Lady Qi was even worse. Lü Zhi ordered her soldiers to imprison Lady Qi in a pigsty, pull out her tongue, blind her, and then chop off all her limbs. Disgusted with his mother, Huidi withdrew from imperial management– leaving even more power in her hands. When he died, she put another infant in power, then another. She ruled the Han Empire as regent for about fifteen years. While Lü Zhi was ruthless in her ambition, she ushered in a time of stability and is said to have improved the lives of the poor.

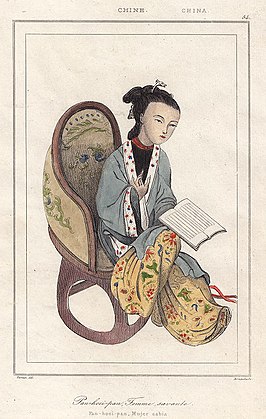

Ban Zhao, Wikimedia Commons

Ban Zhao, Wikimedia Commons

Ban Zhao

Ban Zhao’s brother, Ban Gu, occupied an elevated position at the imperial court. He invited her to rejoin her family at the palace. Her husband’s family saw what an advantage it would be for their heir to grow up at court. So, Ban Zhao returned to court with her child at her side. She worked as a historian with her brother, wrote poetry, and taught the children of the palace, boys as well as girls.

She taught the Classics, astronomy, and mathematics. Several members of the royal family also commissioned poetry from Ban Zhao to mark special occasions. She picked up the work her father and brother had left incomplete. She completed The History of the Han, using private imperial documents. Many historians regard this work as her most valuable contribution to the world.

Ban Zhao became so trusted by the Empress that she was able to advise the ruling family away from decisions that might reflect badly on them. At one memorable point, Empress Deng was reluctant to let a family member retire from his post in order to mourn his mother who had just died. The Empress and the men of her family were worried they might lose some political power if this man retired. Ban Zhao reminded the Empress that “yielding to others” was a Confucian virtue and the court would long remember her unwillingness to yield. As Deng wrote in her autobiography years later, “One word from Mother Ban and the great men withdrew.” Ban Zhao was so beloved that the royal family and everyone at court went into formal mourning when Ban Zhao died in 119 or 120.

Ban Zhao’s brother, Ban Gu, occupied an elevated position at the imperial court. He invited her to rejoin her family at the palace. Her husband’s family saw what an advantage it would be for their heir to grow up at court. So, Ban Zhao returned to court with her child at her side. She worked as a historian with her brother, wrote poetry, and taught the children of the palace, boys as well as girls.

She taught the Classics, astronomy, and mathematics. Several members of the royal family also commissioned poetry from Ban Zhao to mark special occasions. She picked up the work her father and brother had left incomplete. She completed The History of the Han, using private imperial documents. Many historians regard this work as her most valuable contribution to the world.

Ban Zhao became so trusted by the Empress that she was able to advise the ruling family away from decisions that might reflect badly on them. At one memorable point, Empress Deng was reluctant to let a family member retire from his post in order to mourn his mother who had just died. The Empress and the men of her family were worried they might lose some political power if this man retired. Ban Zhao reminded the Empress that “yielding to others” was a Confucian virtue and the court would long remember her unwillingness to yield. As Deng wrote in her autobiography years later, “One word from Mother Ban and the great men withdrew.” Ban Zhao was so beloved that the royal family and everyone at court went into formal mourning when Ban Zhao died in 119 or 120.

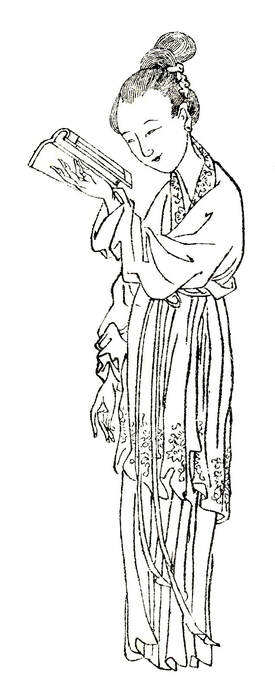

Ban Zhao, Wikimedia Commons

Ban Zhao, Wikimedia Commons

Why is there any question of Ban Zhao’s impact on women? She is best known for a book of advice called Admonitions for Women or Lessons for Women. In it, Ban Zhao makes a very persuasive case that all girls must be educated just as all boys were. The problem arises when we look at what she tells us girls and women should learn.

Confucian philosophy offered numerous paths for boys and men to achieve ren, or “humanity,” including respect, righteousness, altruism, and integrity. According to Ban Zhao, the chief aspects of ren for girls are remaining modest, practicing good hygiene, and staying focused on tasks such as weaving. A good wife should obey her husband and her mother-in-law without hesitation and without complaint.

Ban Zhao stated in the introduction to Admonitions for Women that she was inspired to write it after looking at her early life as a wife and mother. She had learned classical teaching well enough but had not understood her place in the world until she experienced it. She even scolded male scholars, saying, “Now look at the gentlemen of the present age. They only knew that wives must be controlled, and that the husband’s rule and precedence be established. . .but if one only teaches men and does not teach women, is that not ignoring the essential relation between them?”

Admonitions for Women highlights the need for balance and harmony in the home, especially between a husband and wife. She wrote: “The Way of Husband and Wife is associated with yin and yang and reaches to godliness; surely it is an expansive principle of Heaven and Earth and the greatest form of conjugation among human relationships.” For Ban Zhao, the yin and yang of marriage are expressed through the authority and control of the man and the righteous service of the woman. If either spouse is not fulfilling their role the home will fall into conflict and despair.

Preparation for her life as a wife and mother begins within a few days of a girl’s birth. A newborn girl should be placed under a bed—not on the bed—so she will always know her place. “It is a cardinal rule for her to be subordinate to others,” Ban Zhao wrote.

The baby girl should be given something to play with to emphasize the hard work that will be expected of her. In some translations the word for the toy is “tile,” or interpreted as broken pottery, representing a harsh life. But some scholars think that Ban Zhao was suggesting baby girls play with a ceramic whorl, something she would learn to use when spinning and weaving. The plaything emphasizes feminine domesticity and not necessarily a harsh life.

Finally, the girl’s birth should be marked with fasting and an announcement of her arrival to the ancestors she will grow up to honor. All of these practices establish a girl’s place in her family right from the start.

Ultimately, Ban Zhao summed up her lessons by advising women to be single-minded about everything, but especially about devotion to their husbands. That extends even to staying in an unhappy marriage and remaining unmarried after a husband’s death. The woman should not be too curious and should never challenge anything but dedicate herself to a life of perfect service.

Confucian philosophy offered numerous paths for boys and men to achieve ren, or “humanity,” including respect, righteousness, altruism, and integrity. According to Ban Zhao, the chief aspects of ren for girls are remaining modest, practicing good hygiene, and staying focused on tasks such as weaving. A good wife should obey her husband and her mother-in-law without hesitation and without complaint.

Ban Zhao stated in the introduction to Admonitions for Women that she was inspired to write it after looking at her early life as a wife and mother. She had learned classical teaching well enough but had not understood her place in the world until she experienced it. She even scolded male scholars, saying, “Now look at the gentlemen of the present age. They only knew that wives must be controlled, and that the husband’s rule and precedence be established. . .but if one only teaches men and does not teach women, is that not ignoring the essential relation between them?”

Admonitions for Women highlights the need for balance and harmony in the home, especially between a husband and wife. She wrote: “The Way of Husband and Wife is associated with yin and yang and reaches to godliness; surely it is an expansive principle of Heaven and Earth and the greatest form of conjugation among human relationships.” For Ban Zhao, the yin and yang of marriage are expressed through the authority and control of the man and the righteous service of the woman. If either spouse is not fulfilling their role the home will fall into conflict and despair.

Preparation for her life as a wife and mother begins within a few days of a girl’s birth. A newborn girl should be placed under a bed—not on the bed—so she will always know her place. “It is a cardinal rule for her to be subordinate to others,” Ban Zhao wrote.

The baby girl should be given something to play with to emphasize the hard work that will be expected of her. In some translations the word for the toy is “tile,” or interpreted as broken pottery, representing a harsh life. But some scholars think that Ban Zhao was suggesting baby girls play with a ceramic whorl, something she would learn to use when spinning and weaving. The plaything emphasizes feminine domesticity and not necessarily a harsh life.

Finally, the girl’s birth should be marked with fasting and an announcement of her arrival to the ancestors she will grow up to honor. All of these practices establish a girl’s place in her family right from the start.

Ultimately, Ban Zhao summed up her lessons by advising women to be single-minded about everything, but especially about devotion to their husbands. That extends even to staying in an unhappy marriage and remaining unmarried after a husband’s death. The woman should not be too curious and should never challenge anything but dedicate herself to a life of perfect service.

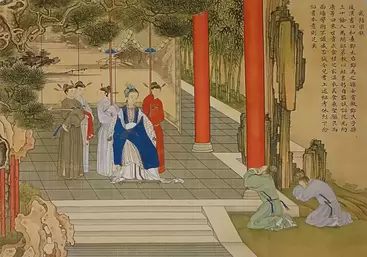

Empress Deng, Wikimedia Commons

Empress Deng, Wikimedia Commons

Ban Zhao was a woman who lived an unusual and amazing life. She fought for the equal education of girls. She even oversaw the education of the Empress Deng and supported that woman while she was at the height of her power. But she also decided the best preparation for a Chinese woman’s future was to remember her lowly place in the world and do her best to sacrifice herself for everyone around her.

As late as the 18th century, her work was counted as one of the Four Essential Books for Women. Ban Zhao was a pioneer for women who happened to live in a time and place in which women dared not reach for too much. At the same time, even the other women in her family did not share her views. A sister to Ban Zhao’s husband wrote a treatise disputing Admonitions for Women. Unfortunately, that work has been lost.

As late as the 18th century, her work was counted as one of the Four Essential Books for Women. Ban Zhao was a pioneer for women who happened to live in a time and place in which women dared not reach for too much. At the same time, even the other women in her family did not share her views. A sister to Ban Zhao’s husband wrote a treatise disputing Admonitions for Women. Unfortunately, that work has been lost.

Trung Sisters on Elephant Back, Wikimedia Commons

Trung Sisters on Elephant Back, Wikimedia Commons

Vietnam

While the Han Dynasty expanded its control over the provinces of China, it also sought to expand China’s

borders. But they found that some of the greatest opposition to their expansion came from women.

Sisters Trung Trac and Trung Nhi were the daughters of a prominent general and politician who had become a vassal for the Chinese when they first invaded Vietnam and who pushed back against the Chinese when it became necessary to protect the Vietnamese people. The sisters were well-educated and even studied martial arts with their father, as Vietnamese society was far more progressive in their views of women than their Chinese counterparts. Women had social positions, could inherit property of their husbands or fathers, and had more rights in their marriages.

Increased efforts of control by the Chinese inspired additional resistance from the Vietnamese vassals and the population. Trung Trac had married a general from a neighboring district, Thi Sach, and fomented a rebellion among the upper classes. He was soon captured and executed by the Chinese. Trung Trac, alongside her sister Trung Nhi, began to mobilize local people of all classes to rise up against Chinese rule. They spearheaded a force of 80,000 soldiers, and they decided to lead from the front.

The two sisters and even their elderly mother were among the 36 female generals leading this army against the Chinese. The Trung sisters and their army stormed several dozen Chinese-run citadels and the governor’s home, successfully forcing him out of the region. Trung Trac was then named queen, and reigned alongside her sister. Unfortunately, the Han overthrew the sisters a few years later, and they threw themselves into a river to avoid torture and execution by the Chinese.

The two sisters remain a symbol of not only feminine power, but of freedom and Vietnam’s ability to rise above oppression. They drove the mighty Chinese out of their lands with a massive army willing to follow them and their female leadership within the army where their male predecessors had failed. Their reign was short, but their memory has been preserved even into the 20th century struggles against Japanese encroachment, French imperialism, and American involvement in the Vietnam War.

Conclusion

Despite devastatingly low opinions of women, limited rights, and a horrible status for women in China, there are notable women who defied patriarchal structures, secured power, and became the subject of history. While these outliers are known, many women’s stories have been lost to time.

Why did these women stand the test of time, and how are they symbolic of their time or region? How can their stories be applied to modern female leadership? What stories have we lost? What were the likely experiences of average women? And how would they have viewed these brave women?

While the Han Dynasty expanded its control over the provinces of China, it also sought to expand China’s

borders. But they found that some of the greatest opposition to their expansion came from women.

Sisters Trung Trac and Trung Nhi were the daughters of a prominent general and politician who had become a vassal for the Chinese when they first invaded Vietnam and who pushed back against the Chinese when it became necessary to protect the Vietnamese people. The sisters were well-educated and even studied martial arts with their father, as Vietnamese society was far more progressive in their views of women than their Chinese counterparts. Women had social positions, could inherit property of their husbands or fathers, and had more rights in their marriages.

Increased efforts of control by the Chinese inspired additional resistance from the Vietnamese vassals and the population. Trung Trac had married a general from a neighboring district, Thi Sach, and fomented a rebellion among the upper classes. He was soon captured and executed by the Chinese. Trung Trac, alongside her sister Trung Nhi, began to mobilize local people of all classes to rise up against Chinese rule. They spearheaded a force of 80,000 soldiers, and they decided to lead from the front.

The two sisters and even their elderly mother were among the 36 female generals leading this army against the Chinese. The Trung sisters and their army stormed several dozen Chinese-run citadels and the governor’s home, successfully forcing him out of the region. Trung Trac was then named queen, and reigned alongside her sister. Unfortunately, the Han overthrew the sisters a few years later, and they threw themselves into a river to avoid torture and execution by the Chinese.

The two sisters remain a symbol of not only feminine power, but of freedom and Vietnam’s ability to rise above oppression. They drove the mighty Chinese out of their lands with a massive army willing to follow them and their female leadership within the army where their male predecessors had failed. Their reign was short, but their memory has been preserved even into the 20th century struggles against Japanese encroachment, French imperialism, and American involvement in the Vietnam War.

Conclusion

Despite devastatingly low opinions of women, limited rights, and a horrible status for women in China, there are notable women who defied patriarchal structures, secured power, and became the subject of history. While these outliers are known, many women’s stories have been lost to time.

Why did these women stand the test of time, and how are they symbolic of their time or region? How can their stories be applied to modern female leadership? What stories have we lost? What were the likely experiences of average women? And how would they have viewed these brave women?

Draw your own conclusions

|

Learn how to teach with inquiry.

Many of these lesson plans were sponsored in part by the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources Eastern Region Program, coordinated by Waynesburg University, the History and Social Studies Education Faculty at Plymouth State University, and the Patrons of the Remedial Herstory Project. |

Lesson Plans from Other Organizations

- This website, Women in World History has primary source based lesson plans on women's history in a whole range of topics. Some are free while others have a cost.

- The Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media has produced recommendations for teaching women's history with primary sources and provided a collection of sources for world history. Check them out!

- The Stanford History Education Group has a number of lesson plans about women in World History.

Unknown: The Three Obediences

The Three Obediences were social, cultural guidance to women in ancient China, and present well before Confucius. They were the common expectations for women.

“Women should be obedient

Synthesis:

“Women should be obedient

- to father before marriage

- to husband after marriage

- and to son after the death of husband.”

Synthesis:

- Were the three obediences inherently sexist? Explain?

Confucian Writings: Part I

Confucius, or Kǒng Qiū 孔丘, lived around 500 BCE and was considered one of the great Chinese sages. He was a bureaucrat, teacher, and philosopher. He lived in a time when leaders were corrupt and not working toward the needs of the empire and its people. He wanted social harmony and political stability grounded in trust and mutual moral obligations for China. Confucius said very little about women. His ideas were recorded by his disciples. This is what they did say about women.

“A Confucian conception of woman is integrally related to a Confucian understanding of the cosmos. The genders female and male are placed within a cosmic harmony (he) that includes two opposite yet complementary forces, powers, or energies, namely, yin and yang… Kun is Earth, pure yin, and female: ‘Kun consists of fundamentality, and prevalence, and its fitness is that of the constancy of the mare. Here is the basic disposition of the Earth: this constitutes the image of Kun. In the same manner, the noble man with his generous virtue carries everything’ (Lynn: 142-144). The superior person is also guided by kun, the female, which is yielding, receptive, and directive of power and, like qian, productive of good. Qian initiates, whereas kun completes. Richard Wilhelm comments: ‘It is the perfect complement of THE CREATIVE [qian] -the complement, not the opposite, for the Receptive [kun] does not combat the Creative but completes it here, because there is a clearly defined hierarchic relationship between the two principles.’”

Clark, Kelly James, and Robin R. Wang. “A Confucian Defense of Gender Equity.” Journal of the American Academy of Religion 72, no. 2 (2004): 395–422. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40005811.

Questions:

“A Confucian conception of woman is integrally related to a Confucian understanding of the cosmos. The genders female and male are placed within a cosmic harmony (he) that includes two opposite yet complementary forces, powers, or energies, namely, yin and yang… Kun is Earth, pure yin, and female: ‘Kun consists of fundamentality, and prevalence, and its fitness is that of the constancy of the mare. Here is the basic disposition of the Earth: this constitutes the image of Kun. In the same manner, the noble man with his generous virtue carries everything’ (Lynn: 142-144). The superior person is also guided by kun, the female, which is yielding, receptive, and directive of power and, like qian, productive of good. Qian initiates, whereas kun completes. Richard Wilhelm comments: ‘It is the perfect complement of THE CREATIVE [qian] -the complement, not the opposite, for the Receptive [kun] does not combat the Creative but completes it here, because there is a clearly defined hierarchic relationship between the two principles.’”

Clark, Kelly James, and Robin R. Wang. “A Confucian Defense of Gender Equity.” Journal of the American Academy of Religion 72, no. 2 (2004): 395–422. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40005811.

Questions:

- Based on this text, what were Confucian ideals for women?

- What does this tell us about the gender roles in society around the time it was recorded?

Confucian Writings: Part II

Confucius, or Kǒng Qiū 孔丘, lived around 500 BCE and was considered one of the great Chinese sages. He was a bureaucrat, teacher, and philosopher. He lived in a time when leaders were corrupt and not working toward the needs of the empire and its people. He wanted social harmony and political stability grounded in trust and mutual moral obligations for China. Confucius said very little about women. His ideas were recorded by his disciples. This is what they did say about women.

"The Master said: Only women and small men seem difficult to look after. If

you keep them close, they become insubordinate; but if you keep them at a distance, they become resentful" (Analects 17:23).

“Keep your daughter indoors… she ought to be under your total command. You should scold her roundly if she is not quick to obey, remind her often of self-discipline and household duties. Ensure that she shows due deference towards guests and that she retires quietly once the tea has been served. Do not spoil your daughter for fear of her becoming unruly. Never encourage or tolerate self-destructive behaviour for fear of fostering in her a suicidal tendency. Do not teach her to sing for fear of corrupting her mind. Do not let her loiter for fear of evil-temptation.”

Goldin, Paul R. “Admonitions for Women”, Hawaii Reader in Traditional Chinese Culture (University of

Hawai’i Press, 2017).

Questions:

"The Master said: Only women and small men seem difficult to look after. If

you keep them close, they become insubordinate; but if you keep them at a distance, they become resentful" (Analects 17:23).

“Keep your daughter indoors… she ought to be under your total command. You should scold her roundly if she is not quick to obey, remind her often of self-discipline and household duties. Ensure that she shows due deference towards guests and that she retires quietly once the tea has been served. Do not spoil your daughter for fear of her becoming unruly. Never encourage or tolerate self-destructive behaviour for fear of fostering in her a suicidal tendency. Do not teach her to sing for fear of corrupting her mind. Do not let her loiter for fear of evil-temptation.”

Goldin, Paul R. “Admonitions for Women”, Hawaii Reader in Traditional Chinese Culture (University of

Hawai’i Press, 2017).

Questions:

- Based on this text, what were Confucian ideals for women?

- What does this tell us about the gender roles in society around the time it was recorded?

Ban Zhao: On Women

In China, the first historians did not emerge until the Later Han Empire (23-220) at which point there was stability and wealth, which usually led to opportunities for women intellectuals and leaders. And for the Han, this was certainly true. One of the first woman historians was Ban Zhao (45-117). It is not surprising Ban Zhao expanded on ideas about women. Ban Zhao was not immune to her time; her ideas were heavily influenced by the dominant Confucian thought.

“A woman (ought to) have four qualifications: (1) womanly virtue; (2) womanly words; (3) womanly bearing; and (4) womanly work. Now what is called womanly virtue need not be brilliant ability, exceptionally different from others. Womanly words need be neither clever in debate nor keen in conversation. Womanly appearance requires neither a pretty nor a perfect face and form. Womanly work need not be work done more skillfully than that of others.”

Yuen Ting Lee, “Ban Zhao: Scholar of Han Dynasty China,” World History Connected, last modified 2012, https://worldhistoryconnected.press.uillinois.edu/9.1/lee.html.

Questions:

- How did Zhao’s ideas for women differ from the Confucius’ that predated her?

- Is Confucianism sexist?

Sima Qian: On Empress Lü

Sima Qiuan is one of two well known early Chinese historians. He wrote histories which included Empress Lü. Sima Qian blames her actions on fear. It is to be noted Sima Qian wrote his history first and influenced later historians like Ban Gu.

The ages before the Qin are too far away and the material on them too scanty to permit a detailed account of them here. When the Han arose, Lü Exu became the official Empress of Gaozu and her son became heir apparent. Yet as she grew older and her beauty faded, the Emperor’s affection for her waned; Lady Qi was favored and her son Liu Ruyi had several times almost replaced the heir apparent. When Gaozu died, Empress Lü exterminated the Qi family and executed the King of Zhao [Liu Ruyi]. Of the women of the rear palaces, only those who had not enjoyed his favor and were far away managed to escape harm

Empress Lü’s eldest daughter was married to Zhang Ao, the marquis of Xuanping, and their daughter became the empress of Emperor Hui. Empress Dowager Lü, anxious to increase her ties [with the imperial family], hoped that this girl would give birth to a son, but though she resorted to every possible device, the young Empress remained childless. [Empress Lü] then secretly took the child of one of [Emperor Hui’s] concubines and pretended that he was the son of the Empress. When Emperor Hui passed away, it was still only a short while since the dynasty had been founded, and the question of who might succeed to the throne was unclear. Thereupon [Empress Dowager Lü] accorded great honor to the members of the outer family [Lü] and established the [male members] of the Lü as kings, so that they might act as aides. She also appointed the daughter of Lü Lu as Empress to the child Emperor. Thus she hoped to establish firm ties that would bind her own family securely to the source of power. But it was to no avail.3

Empress [Lü] as a female ruler announced [she would issue] the imperial decrees and managed to govern without going out of her chambers; and the world was peaceful, punishments and penalties were rarely employed, and those who had committed offenses then became rare. The people devoted themselves to planting and harvesting, and [as a result] clothing and food became increasingly abundant.

The ages before the Qin are too far away and the material on them too scanty to permit a detailed account of them here. When the Han arose, Lü Exu became the official Empress of Gaozu and her son became heir apparent. Yet as she grew older and her beauty faded, the Emperor’s affection for her waned; Lady Qi was favored and her son Liu Ruyi had several times almost replaced the heir apparent. When Gaozu died, Empress Lü exterminated the Qi family and executed the King of Zhao [Liu Ruyi]. Of the women of the rear palaces, only those who had not enjoyed his favor and were far away managed to escape harm

Empress Lü’s eldest daughter was married to Zhang Ao, the marquis of Xuanping, and their daughter became the empress of Emperor Hui. Empress Dowager Lü, anxious to increase her ties [with the imperial family], hoped that this girl would give birth to a son, but though she resorted to every possible device, the young Empress remained childless. [Empress Lü] then secretly took the child of one of [Emperor Hui’s] concubines and pretended that he was the son of the Empress. When Emperor Hui passed away, it was still only a short while since the dynasty had been founded, and the question of who might succeed to the throne was unclear. Thereupon [Empress Dowager Lü] accorded great honor to the members of the outer family [Lü] and established the [male members] of the Lü as kings, so that they might act as aides. She also appointed the daughter of Lü Lu as Empress to the child Emperor. Thus she hoped to establish firm ties that would bind her own family securely to the source of power. But it was to no avail.3

Empress [Lü] as a female ruler announced [she would issue] the imperial decrees and managed to govern without going out of her chambers; and the world was peaceful, punishments and penalties were rarely employed, and those who had committed offenses then became rare. The people devoted themselves to planting and harvesting, and [as a result] clothing and food became increasingly abundant.

Ban Gu: On empress Lü

Ban Gu is the other prominent Chinese historian to write about Empress Lü. Ban Gu blames her nature for her treatment of Lady Qi.

Emperor Gao died, Emperor Hui was established, and Empress Lu was the Empress Dowager. She ordered Yongxiang to imprison Mrs. Qi, clasping her clothes and ochre clothes, and ordering them to pound. Mrs. Qi sang and sang: "The son is the king, the mother is the captive, all day long at dusk, always with the dead! Three thousand miles away, who should tell the daughter?" Evil women?" He called the King of Zhao to execute him. The messenger had three rebellions, but Zhou Chang, the prime minister of Zhao, did not send him. The Empress Dowager summoned Zhao Xiang to march to Chang'an. Let people summon the king of Zhao again, and the king will come. Emperor Hui was merciful, knowing that the queen mother was angry, she welcomed the king of Zhao, entered the palace, and lived and dined with him. A few months later, when the emperor shot out in the morning, the king of Zhao could not get up, and the queen mother waited for him to live alone, and had people drink it with poison. Emperor Chi returned, and King Zhao died. The Empress Dowager cut off Madam Qi's hands and feet, removed her eyes and smoked her ears, and drank herbal medicine, so she lived in the Ju domain and was called "Ren She". After staying for several months, he called Emperor Hui to see "Ren She". The emperor looked up and asked his wife Qi, but she cried a lot. They asked the queen mother to say, "This is not what people did. The minister is the son of the queen mother, and I will never be able to govern the world again!"

The queen mother was mourning, crying and weeping. Zhang Biqiang, the son of the marquis, was left as a servant, and when he was fifteen years old, he asked the prime minister, Chen Ping, and said: "The empress dowager has only the emperor. Today, I cry and not feel sad. Do you know the solution?" Chen Ping said, "What is the solution?" Piqiang said, "The emperor There are no strong sons, the queen mother is afraid of the king, etc. Now please worship Lu Tai and Lu Chan as generals, the soldiers will be in the northern and southern armies, and all Lu are officials, and they are in the middle. Piqiang plans to invite him, the queen mother said, the cry is mourning. Lu Shiquan started from this. He established Xiaohui Empress Gongzi as the emperor, and the Empress Dowager was called the emperor.

Van Ess, Hans. “Praise and Slander: The Evocation of Empress Lü in the Shiji and the Hanshu.” NAN NU -- Men, Women & Gender in Early & Imperial China 8, no. 2 (September 2006): 221–54. doi:10.1163/156852606779969824.

Emperor Gao died, Emperor Hui was established, and Empress Lu was the Empress Dowager. She ordered Yongxiang to imprison Mrs. Qi, clasping her clothes and ochre clothes, and ordering them to pound. Mrs. Qi sang and sang: "The son is the king, the mother is the captive, all day long at dusk, always with the dead! Three thousand miles away, who should tell the daughter?" Evil women?" He called the King of Zhao to execute him. The messenger had three rebellions, but Zhou Chang, the prime minister of Zhao, did not send him. The Empress Dowager summoned Zhao Xiang to march to Chang'an. Let people summon the king of Zhao again, and the king will come. Emperor Hui was merciful, knowing that the queen mother was angry, she welcomed the king of Zhao, entered the palace, and lived and dined with him. A few months later, when the emperor shot out in the morning, the king of Zhao could not get up, and the queen mother waited for him to live alone, and had people drink it with poison. Emperor Chi returned, and King Zhao died. The Empress Dowager cut off Madam Qi's hands and feet, removed her eyes and smoked her ears, and drank herbal medicine, so she lived in the Ju domain and was called "Ren She". After staying for several months, he called Emperor Hui to see "Ren She". The emperor looked up and asked his wife Qi, but she cried a lot. They asked the queen mother to say, "This is not what people did. The minister is the son of the queen mother, and I will never be able to govern the world again!"

The queen mother was mourning, crying and weeping. Zhang Biqiang, the son of the marquis, was left as a servant, and when he was fifteen years old, he asked the prime minister, Chen Ping, and said: "The empress dowager has only the emperor. Today, I cry and not feel sad. Do you know the solution?" Chen Ping said, "What is the solution?" Piqiang said, "The emperor There are no strong sons, the queen mother is afraid of the king, etc. Now please worship Lu Tai and Lu Chan as generals, the soldiers will be in the northern and southern armies, and all Lu are officials, and they are in the middle. Piqiang plans to invite him, the queen mother said, the cry is mourning. Lu Shiquan started from this. He established Xiaohui Empress Gongzi as the emperor, and the Empress Dowager was called the emperor.

Van Ess, Hans. “Praise and Slander: The Evocation of Empress Lü in the Shiji and the Hanshu.” NAN NU -- Men, Women & Gender in Early & Imperial China 8, no. 2 (September 2006): 221–54. doi:10.1163/156852606779969824.

Remedial Herstory Editors. "8. 100 BCE - 100 CE WOMEN AND THE HAN EMPIRE." The Remedial Herstory Project. November 1, 2022. www.remedialherstory.com.

AUTHOR: |

Kelsie Brook Eckert

|

Consulting Team |

Editors |

|

Kelsie Brook Eckert, Project Director

Coordinator of Social Studies Education at Plymouth State University Dr. Nancy Locklin-Sofer, Consultant Professor of History at Maryville College. Chloe Gardner, Consultant PhD Candidate in Religious Studies at Edinburgh University Dr. Whitney Howarth, Consultant Former Professor of History at Plymouth State University Jacqui Nelson, Consultant Teaching Lecturer of Military History at Plymouth State University Maria Concepcion Marquez Sandoval PhD Candidate in History at Arizona University |

Ron Kaiser

Humanities Teacher, Moultonborough Academy ReviewersAncient:

Dr. Kristin Heineman Professor of History at Colorado State University Dr. Bonnie Rock-McCutcheon Professor of History at Wilson College Sarah Stone PhD Candidate in Religious Studies at Edinburgh University Medieval: Dr. Katherine Koh Professor of History at La Sierra University Dr. Jonathan Couser Professor of History at Plymouth State University Dr. Shahla Haeri Professor of History at Boston University Lauren Cole PhD Candidate in History at Northwestern University Modern: Dr. Jack Gronau Professor of History at Northeastern University Dr. Barbara Tischler Supervisor for Hunter College Dr. Pamela Scully Professor of Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies and African Studies at Emory University |

|

In early China, was it correct for a woman to disobey her father, contradict her husband, or shape the public policy of a son who ruled over a dynasty or state? According to the Lienü zhuan, or Categorized Biographies of Women, it was not only appropriate but necessary for women to step in with wise counsel when fathers, husbands, or rulers strayed from the path of virtue.

|

Explores historical and philosophical shifts in the depiction of women and virtue in the early years of the Chinese state. Includes an examination of the history of yin-yang theories.

|

Through the lenses of mysticism, naturalism, and ordinary life, the five dozen poems collected here express these women’s profound devotion to Daoist spiritual practice. Their interweaving of plain but poignant and revealing speech with a compelling and inventive use of imagery expresses their creative relationship to the myths, legends, and traditions of Daoist Goddess culture.

|

Bibliography

Beard, Mary. Women & Power: A Manifesto. Liveright Publishing Corporation: New York, NY, 2017.

Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. "Gaohou." Encyclopedia Britannica, October 19, 2015. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Gaohou.

Hinsch, Bret. “The Criticism of Powerful Women by Western Han Dynasty Portent Experts.” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 49, no. 1 (2006): 96–121. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25165130.

The Records of the Grand Historian (Shi ji) by Sima Qian, translated by Burton Watson. New York: Columbia University Press, 1993.

Strayer, R. and Nelson, E., Ways Of The World. 3rd ed. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2016.

Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. "Gaohou." Encyclopedia Britannica, October 19, 2015. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Gaohou.

Hinsch, Bret. “The Criticism of Powerful Women by Western Han Dynasty Portent Experts.” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 49, no. 1 (2006): 96–121. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25165130.

The Records of the Grand Historian (Shi ji) by Sima Qian, translated by Burton Watson. New York: Columbia University Press, 1993.

Strayer, R. and Nelson, E., Ways Of The World. 3rd ed. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2016.