9. Women in the Civil War

|

The role of women throughout the American Civil War was diverse and widespread. Regardless of whether one was black or white, southern or northern, women were vital in the war efforts. Some were soldiers, nurses, or took control over their farms and families stations that the men usually would.

|

Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of Uncle Tom's Cabin

Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of Uncle Tom's Cabin

When one thinks about war, what comes to mind first? Usually, it is soldiers and the political leaders of the time who in the 1860s were all men. As always we ask, “Where are the women?” During the American Civil War, the answer was: everywhere.

The Civil War was fought from April 1861 to April 1865 and began because the United States could no longer remain “half slave and half free” as Lincoln suggested. Southerners were threatened by Lincoln’s election and Northerners were not going to let them undermine a democratic election by seceding.

Women from both the North and the South were important actors in the war. As soon as the first shots rang out at Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina, women were active on the homefront and the front lines. They immediately assumed the roles of soldiers, couriers, nurses, spies, and caretakers of their homes, farms, and families in the face of severe danger and deprivation.

Leading up to the war, women influenced public opinion on the primary political issues of the time: ending slavery. Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel was the closest thing to a national bestseller and riled up the north leading to the war. The book, Uncle Tom’s Cabin touched the hearts of readers throughout the North and as far away as London. Queen Victoria is even said to have wept on reading the novel. There’s a famous story that, when he was introduced to Stowe, President Lincoln commented that she was "the little woman who wrote the book that started this great war."

The most memorable song of the Civil War was Julia Ward Howe’s “Battle Hymn of the Republic.” Howe heard Union soldiers draft new words onto an old Methodist hymn to create “John Brown’s Body.” She adapted the hymn with words of her own intended to cast the war in moral and religious terms. The song was a popular and invigorating anthem among Union soldiers not only toward victory, but the moral imperative to end slavery.

She said:

“Let the Hero, born of woman, crush the serpent with His heel,

Since God is marching on. As He died to make men holy, let us die to make men free;

While God is marching on.

He is coming like the glory of the morning on the wave.”

The Civil War was fought from April 1861 to April 1865 and began because the United States could no longer remain “half slave and half free” as Lincoln suggested. Southerners were threatened by Lincoln’s election and Northerners were not going to let them undermine a democratic election by seceding.

Women from both the North and the South were important actors in the war. As soon as the first shots rang out at Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina, women were active on the homefront and the front lines. They immediately assumed the roles of soldiers, couriers, nurses, spies, and caretakers of their homes, farms, and families in the face of severe danger and deprivation.

Leading up to the war, women influenced public opinion on the primary political issues of the time: ending slavery. Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel was the closest thing to a national bestseller and riled up the north leading to the war. The book, Uncle Tom’s Cabin touched the hearts of readers throughout the North and as far away as London. Queen Victoria is even said to have wept on reading the novel. There’s a famous story that, when he was introduced to Stowe, President Lincoln commented that she was "the little woman who wrote the book that started this great war."

The most memorable song of the Civil War was Julia Ward Howe’s “Battle Hymn of the Republic.” Howe heard Union soldiers draft new words onto an old Methodist hymn to create “John Brown’s Body.” She adapted the hymn with words of her own intended to cast the war in moral and religious terms. The song was a popular and invigorating anthem among Union soldiers not only toward victory, but the moral imperative to end slavery.

She said:

“Let the Hero, born of woman, crush the serpent with His heel,

Since God is marching on. As He died to make men holy, let us die to make men free;

While God is marching on.

He is coming like the glory of the morning on the wave.”

Loreta Jareta Velazquez

Loreta Jareta Velazquez

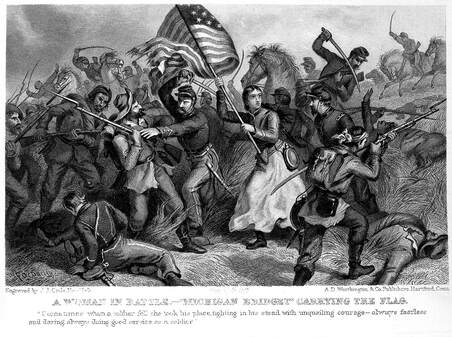

Women Soldiers:

Once the war began, women from both the North and the South sought to find their place in the war effort.

Neither the Union nor the Confederate military kept adequate records of women who served on the battlefield. This is likely because both sides actually forbade women from enlisting. In 1909, journalist Ida Tarbell inquired about women soldiers and was informed by the Army’s Adjutant General’, C. F. Ainsworth, that no women had fought in the Civil War; however, we know this was not true. Recent estimates indicate that anywhere from 400 to 1,000 women answered the call to arms for either the Union or the Confederacy.

Why did women join the fight? They went to war for the same reason as men. Some believed in the cause of their side, such as Loreta Janeta Velazquez, who revealed in her 1876 memoir that she had served as Lieutenant Harry T. Buford in the Confederate Army for eighteen months. She may have been able to obscure her gender identity because she was an independent soldier not attached to any regiment. She saw herself as a soldier, a spy, and a secret-service agent, dedicated to the cause of the Confederacy.

A few women went to war to be with their loved ones. Florina Budwin enlisted with her husband. They were captured together by Confederate forces and were sent to the horrific prison at Andersonville at the same time. He died there in 1862, and she succumbed to an unspecified illness after being discovered as female and sent to a more humane prison in 1865. Budwin was one of a very few women who were prisoners of war.

Frances Clalin Clayton was a mother of three from Illinois. She enlisted as “Jack Williams” in order to join her husband in the Union Army. They fought side-by-side until he was killed, then, supposedly, she stepped over his body to continue fighting. She was honored as a veteran.

Once the war began, women from both the North and the South sought to find their place in the war effort.

Neither the Union nor the Confederate military kept adequate records of women who served on the battlefield. This is likely because both sides actually forbade women from enlisting. In 1909, journalist Ida Tarbell inquired about women soldiers and was informed by the Army’s Adjutant General’, C. F. Ainsworth, that no women had fought in the Civil War; however, we know this was not true. Recent estimates indicate that anywhere from 400 to 1,000 women answered the call to arms for either the Union or the Confederacy.

Why did women join the fight? They went to war for the same reason as men. Some believed in the cause of their side, such as Loreta Janeta Velazquez, who revealed in her 1876 memoir that she had served as Lieutenant Harry T. Buford in the Confederate Army for eighteen months. She may have been able to obscure her gender identity because she was an independent soldier not attached to any regiment. She saw herself as a soldier, a spy, and a secret-service agent, dedicated to the cause of the Confederacy.

A few women went to war to be with their loved ones. Florina Budwin enlisted with her husband. They were captured together by Confederate forces and were sent to the horrific prison at Andersonville at the same time. He died there in 1862, and she succumbed to an unspecified illness after being discovered as female and sent to a more humane prison in 1865. Budwin was one of a very few women who were prisoners of war.

Frances Clalin Clayton was a mother of three from Illinois. She enlisted as “Jack Williams” in order to join her husband in the Union Army. They fought side-by-side until he was killed, then, supposedly, she stepped over his body to continue fighting. She was honored as a veteran.

An image depicting a woman battling in the American Civil War

An image depicting a woman battling in the American Civil War

Some women sought adventure and wanted to do their part by serving their country. Sarah Emma Edmonds enlisted as “Franklin Flint Thompson” and served in the 2nd Michigan infantry regiment. When she first joined the army as Franklin Thompson, she was a male field nurse. In March of 1862, she was assigned to the role of mail carrier. This position allowed her to be involved in several battles without having to be on the battlefield. In August of 1862, during the Battle of Second Manassas, she was forced to ride a mule to deliver messages once her horse was killed. The mule threw her off, causing her to break her leg and suffer internal injuries which plagued her for the rest of her life. However, by Spring of 1863 Edmonds contracted malaria. After being denied furlough “Franklin Thompson” deserted and she resumed life as Emma. She spent the rest of the war volunteering with the United States Christian Commission as a nurse. She wanted to be fully involved in the war effort to serve the Union and was grateful for the chance to fight and not be compelled “to stay home and weep.” After the war she recorded her story as an epic adventure in an autobiographical novel that in some cases seems far-fetched. She wrote, “I was highly commended by the commanding general for my coolness throughout the whole affair, and was told kindly and candidly that I would not be permitted to go out again… I would consequently be hung up to the nearest tree. Not having any particular fancy for such an exalted position… I turned my attention to more quiet and less dangerous duties.”

A small number of people with female genitalia who enlisted in the war continued to live as men after the surrender at Appomattox. Jennie Hodgers enlisted in the 95th Illinois infantry regiment as Albert Cashier. Their identity was not discovered during the war, and they lived the remainder of their life as a man. Cashier received a military pension and spent their final years in a veterans’ home, where the staff found out about their biological gender, and forced them to wear a dress. Cashier was buried in their Union uniform, the casket was draped with the American flag, and was given a full military funeral. The tombstone has both their given name and the name that they chose for themself, Albert Cashier.

A small number of people with female genitalia who enlisted in the war continued to live as men after the surrender at Appomattox. Jennie Hodgers enlisted in the 95th Illinois infantry regiment as Albert Cashier. Their identity was not discovered during the war, and they lived the remainder of their life as a man. Cashier received a military pension and spent their final years in a veterans’ home, where the staff found out about their biological gender, and forced them to wear a dress. Cashier was buried in their Union uniform, the casket was draped with the American flag, and was given a full military funeral. The tombstone has both their given name and the name that they chose for themself, Albert Cashier.

Harriet Tubman

Harriet Tubman

Free Women Soldiers:

Harriet Tubman served as a nurse, cook and laundress at Union occupied Fort Monroe in Virginia that houses refugee slaves. In June of 1863, Harriet Tubman became the first and only woman to lead a military expedition during the Civil War. She led 150 soldiers on three federal gunboats up the Combahee River in South Carolina to help free slaves from several prominent plantations. Altogether approximately 700 enslaved people were free on this expedition. Throughout the Civil War Tubman served the Union cause as a cook, a nurse, and a spy.

Tubman was paid only $200 for her years of service to the United States. She lived out her life in near poverty but is now remembered as a prominent abolitionist and crusader for women’s rights. Frederick Douglass, perhaps the most well known Black man of the time, wrote this of Tubman’s years on the underground railroad and the war, “Most that I have done and suffered in the service of our cause has been in public, and I have received much encouragement at every step of the way. You, on the other hand, have labored in a private way. I have wrought in the day – you in the night. I have had the applause of the crowd and the satisfaction that comes of being approved by the multitude, while the most that you have done has been witnessed by a few trembling, scarred, and foot-sore bondmen and women, whom you have led out of the house of bondage, and whose heartfelt, ‘God bless you’ has been your only reward.” She was incredible.

Only a small number of women served in the military as soldiers. Instead, many chose to help through other means such as becoming nurses, teachers, or volunteers with ladies’ aid societies to help support the war effort.

Susie King Taylor, like Harriet Tubman, was previously enslaved. She, like many other African Americans, found herself seeking safety behind Union lines in South Carolina during the early years of the Civil War. She attached herself to the First South Carolina Volunteers, the first Black regiment in the US Army. While she was with them, she acted as laundress and cook, however, she also taught several members of the regiment how to read. Her ability to read and teach others how to read was an invaluable asset to the unit and per Thomas Wentworth Higginson helped create a “love of the spelling book [that] is perfectly inexhaustible".

Nurses and Doctors:

Women such as Harriet Tubman in the North and Phoebe Yates Pember, Louisa McCord, and Ada Bacot in the South accepted employment in hospitals to help care for those wounded on the battlefield. Before the war began and depleted the amount of men available, men were the primary people involved in the field of nursing. During the war though a shift occurred placing women in the role of primary caregivers for wounded and dying soldiers. In the North, white and free Black women brought food, knitted socks, and homemade bandages. They also helped the soldiers write letters, and tended to the wounded, mainly as volunteers. In the Confederacy, enslaved women were required to perform nursing duties while their owners received compensation.

Harriet Tubman served as a nurse, cook and laundress at Union occupied Fort Monroe in Virginia that houses refugee slaves. In June of 1863, Harriet Tubman became the first and only woman to lead a military expedition during the Civil War. She led 150 soldiers on three federal gunboats up the Combahee River in South Carolina to help free slaves from several prominent plantations. Altogether approximately 700 enslaved people were free on this expedition. Throughout the Civil War Tubman served the Union cause as a cook, a nurse, and a spy.

Tubman was paid only $200 for her years of service to the United States. She lived out her life in near poverty but is now remembered as a prominent abolitionist and crusader for women’s rights. Frederick Douglass, perhaps the most well known Black man of the time, wrote this of Tubman’s years on the underground railroad and the war, “Most that I have done and suffered in the service of our cause has been in public, and I have received much encouragement at every step of the way. You, on the other hand, have labored in a private way. I have wrought in the day – you in the night. I have had the applause of the crowd and the satisfaction that comes of being approved by the multitude, while the most that you have done has been witnessed by a few trembling, scarred, and foot-sore bondmen and women, whom you have led out of the house of bondage, and whose heartfelt, ‘God bless you’ has been your only reward.” She was incredible.

Only a small number of women served in the military as soldiers. Instead, many chose to help through other means such as becoming nurses, teachers, or volunteers with ladies’ aid societies to help support the war effort.

Susie King Taylor, like Harriet Tubman, was previously enslaved. She, like many other African Americans, found herself seeking safety behind Union lines in South Carolina during the early years of the Civil War. She attached herself to the First South Carolina Volunteers, the first Black regiment in the US Army. While she was with them, she acted as laundress and cook, however, she also taught several members of the regiment how to read. Her ability to read and teach others how to read was an invaluable asset to the unit and per Thomas Wentworth Higginson helped create a “love of the spelling book [that] is perfectly inexhaustible".

Nurses and Doctors:

Women such as Harriet Tubman in the North and Phoebe Yates Pember, Louisa McCord, and Ada Bacot in the South accepted employment in hospitals to help care for those wounded on the battlefield. Before the war began and depleted the amount of men available, men were the primary people involved in the field of nursing. During the war though a shift occurred placing women in the role of primary caregivers for wounded and dying soldiers. In the North, white and free Black women brought food, knitted socks, and homemade bandages. They also helped the soldiers write letters, and tended to the wounded, mainly as volunteers. In the Confederacy, enslaved women were required to perform nursing duties while their owners received compensation.

Rose O'Neal Greenhow

Rose O'Neal Greenhow

The medical needs in the wake of the outbreak of the civil war also opened up the medical profession to more women than ever before. Rebecca Lee Crumpler was a nurse in Charleston, Massachusetts before the war began, during which she studied at the New England Female Medical College. She graduated in February 1864 as the country’s first female African American trained physician. Throughout the course of her career she focused on the health of poor women and children, but also worked for the Freedmen's Bureau in Virginia, where she treated recently enslaved people. Later in life she published A Book of Medical Discourses, one of the first medical treatises written by an African American.

While most women served as nurses, a notable exception was Dr. Mary Edwards Walker. Walker acquired her medical degree in 1855 from Syracuse Medical College. She married another medical student and they ended up opening their own medical practice. The practice and their marriage would both fail–the public had trouble accepting a woman doctor, and Walker refused to say “obey” in their marriage vows.

When the Civil War began, offered her services to the Union Army. Walker was initially denied a formal commission and served as an unpaid volunteer at first. She treated troops on the frontlines near Fredericksburg and Chattanooga. Eventually, in 1863, she would gain an official title: “Contract Acting Assistant Surgeon (Civilian)”--thus making her the first female US Army surgeon in the United States. While attending to her patients, Walker refused to wear the traditionally long dresses that most women wore at the time. She found them cumbersome and instead wore shorter dresses with pants underneath. In 1864, she was captured by Confederate troops and held for four months.

After the War, President Andrew Johnson awarded Walker the Congressional Medal of Honor–making her the first and only woman to receive the award. Walker would go on to become an activist for women’s rights. She, on several occasions, was arrested for wearing “men’s clothes.” Her choice of dress–pants, jackets, and top hats–sometimes drew criticism from other women’s rights activists. Of her wardrobe she said: “I don’t wear men’s clothes, I wear my clothes.” At the beginning of the 20th century, she became quite vocal in the fight for women’s suffrage, and even testified before the US House of Representatives in support of women’s suffrage. It is perhaps because of this activism that she was among those who had their awards revoked when Congress established the Medal of Honor Review Board in 1916.

Spies:

Women were effective couriers of military messages, and they were very good spies, in part because most men, and many women, did not think women were capable of such dangerous activity. Rose O’Neal Greenhow was a wealthy Washington D. C. socialite whose social circle included Union officers. She listened as they discussed military operations and forwarded information to Confederate generals, using a network of volunteers, including her own daughter.

When Greenhow learned of Union plans to attack at Manassas in July of 1861, she sent courier Belle Duvall to General P. T. E. Beauregard with valuable information, helping the Confederates to thwart the attack in the first Battle of Bull Run. Greenhow was arrested and sent to prison later in 1861 but was still able to send messages to Confederate officers. She was released in 1862 and traveled to Europe on a diplomatic mission to raise funds for the Confederacy.

Isabella “Belle” Boyd was an effective Confederate spy. She gained notoriety by killing a drunken Union soldier who invaded her Virginia home in July of 1861. Boyd eavesdropped on a conversation among Union officers in May of 1862 and conveyed valuable strategic information to General Stonewall Jackson at considerable personal risk. A few months later, she was incarcerated but quickly released. Like “Wild Rose” Greenhow, Boyd served as a Confederate emissary to England in 1864.

The Union also had its share of female spies. Born in Richmond, Elizabeth Van Lew held strong abolitionist views, convincing her brother to free the family’s slaves in 1843. Elizabeth and her mother visited Union captives in Richmond’s Libby Prison, bringing food and medicine. The women also helped Union soldiers escape. Van Lew developed a web of spies who sent messages to Union officers revealing Confederate battle plans. She got past Confederate troops by hiding messages in hollowed-out eggs or by sewing them into the hem of her skirts. After the war, President Grant appointed Van Lew Postmaster of Richmond.

Freedwomen were some of the best informants. Southerners thought so little of their enslaved women that they would openly discuss strategy and leave maps laying about. Women would soak in that knowledge and flee to the Union lines full of rich intelligence.

Probably the most fascinating Black woman spy was an unnamed woman who served the Confederates as a laundress in Virginia just across the way from where Union soldiers were stationed. She would hang the literal dirty laundry of Confederate soldiers in such a way to provide a code that her husband on the other side would interpret.

While most women served as nurses, a notable exception was Dr. Mary Edwards Walker. Walker acquired her medical degree in 1855 from Syracuse Medical College. She married another medical student and they ended up opening their own medical practice. The practice and their marriage would both fail–the public had trouble accepting a woman doctor, and Walker refused to say “obey” in their marriage vows.

When the Civil War began, offered her services to the Union Army. Walker was initially denied a formal commission and served as an unpaid volunteer at first. She treated troops on the frontlines near Fredericksburg and Chattanooga. Eventually, in 1863, she would gain an official title: “Contract Acting Assistant Surgeon (Civilian)”--thus making her the first female US Army surgeon in the United States. While attending to her patients, Walker refused to wear the traditionally long dresses that most women wore at the time. She found them cumbersome and instead wore shorter dresses with pants underneath. In 1864, she was captured by Confederate troops and held for four months.

After the War, President Andrew Johnson awarded Walker the Congressional Medal of Honor–making her the first and only woman to receive the award. Walker would go on to become an activist for women’s rights. She, on several occasions, was arrested for wearing “men’s clothes.” Her choice of dress–pants, jackets, and top hats–sometimes drew criticism from other women’s rights activists. Of her wardrobe she said: “I don’t wear men’s clothes, I wear my clothes.” At the beginning of the 20th century, she became quite vocal in the fight for women’s suffrage, and even testified before the US House of Representatives in support of women’s suffrage. It is perhaps because of this activism that she was among those who had their awards revoked when Congress established the Medal of Honor Review Board in 1916.

Spies:

Women were effective couriers of military messages, and they were very good spies, in part because most men, and many women, did not think women were capable of such dangerous activity. Rose O’Neal Greenhow was a wealthy Washington D. C. socialite whose social circle included Union officers. She listened as they discussed military operations and forwarded information to Confederate generals, using a network of volunteers, including her own daughter.

When Greenhow learned of Union plans to attack at Manassas in July of 1861, she sent courier Belle Duvall to General P. T. E. Beauregard with valuable information, helping the Confederates to thwart the attack in the first Battle of Bull Run. Greenhow was arrested and sent to prison later in 1861 but was still able to send messages to Confederate officers. She was released in 1862 and traveled to Europe on a diplomatic mission to raise funds for the Confederacy.

Isabella “Belle” Boyd was an effective Confederate spy. She gained notoriety by killing a drunken Union soldier who invaded her Virginia home in July of 1861. Boyd eavesdropped on a conversation among Union officers in May of 1862 and conveyed valuable strategic information to General Stonewall Jackson at considerable personal risk. A few months later, she was incarcerated but quickly released. Like “Wild Rose” Greenhow, Boyd served as a Confederate emissary to England in 1864.

The Union also had its share of female spies. Born in Richmond, Elizabeth Van Lew held strong abolitionist views, convincing her brother to free the family’s slaves in 1843. Elizabeth and her mother visited Union captives in Richmond’s Libby Prison, bringing food and medicine. The women also helped Union soldiers escape. Van Lew developed a web of spies who sent messages to Union officers revealing Confederate battle plans. She got past Confederate troops by hiding messages in hollowed-out eggs or by sewing them into the hem of her skirts. After the war, President Grant appointed Van Lew Postmaster of Richmond.

Freedwomen were some of the best informants. Southerners thought so little of their enslaved women that they would openly discuss strategy and leave maps laying about. Women would soak in that knowledge and flee to the Union lines full of rich intelligence.

Probably the most fascinating Black woman spy was an unnamed woman who served the Confederates as a laundress in Virginia just across the way from where Union soldiers were stationed. She would hang the literal dirty laundry of Confederate soldiers in such a way to provide a code that her husband on the other side would interpret.

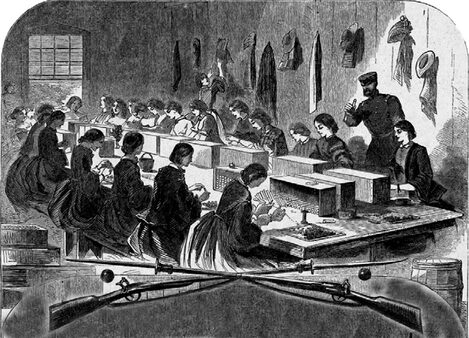

Drawing depicting women refilling cartridges during the Civil War.

Drawing depicting women refilling cartridges during the Civil War.

On the home front, women stepped into new roles as proprietors of farms, businesses, and plantations in the absence of their husbands and other male relatives. In the North, women supervised the planting, tending, and harvesting of crops with the aid of their children and elderly relatives. They completed these tasks in addition to their regular jobs as cooks, seamstresses, and mothers. Many helped to supply the Union Army with food.

Impact of War on Southern White Women:

In the South, where the majority of battles were fought, cities, towns and plantations were devastated. After enslaved people gained their freedom because of the Emancipation Proclamation, plantation mistresses experienced poverty for the first time. Many Union regiments salted the fields so they could not nourish crops, making it all the more difficult for southern women to run their farms.

Women were active in the physical and emotional care of battlefield wounded. Most nursing activity had previously been performed by male “stewards.” During the War, women became the primary caregivers for wounded and dying soldiers. In the North, white and free black women brought food, knitted socks, made bandages, wrote letters, and tended to the wounded, mainly as volunteers. In the Confederacy, enslaved women were required to perform nursing duties while their owners received compensation.

In the South, as the men went to fight, women assumed the duties of managing entire farms and plantations and the slaves that worked them. They often became the primary financial provider for their families, a responsibility that obliged them to procure jobs as nurses, matrons, treasury workers, teachers, and seamstresses. For the first time, elite women in South Carolina negotiated financial hardships, shifting cultural norms, political activities, and a radically altered perception of what it meant to be a Southern woman.

Phoebe Yates Pember, a Confederate nurse at the Chimborazo Hospital in Richmond, Virginia confided in her diary in the summer of 1864, that the confederate money was worthless, and that the weak Congress refused to raise the hospital fund to meet the depreciation of Confederate money. Inflation and Union blockades, alongside the destruction left behind after battles severely hindered the South’s ability to cloth and feed themselves.

Conclusion:

Whether working as soldiers, spies, volunteers, nurses, or staying home and maintaining the house women were active in the war effort. These ladies showed tremendous amounts of courage and strength as they supported either the Union or the Confederacy. Women in the North helped support the Union and its mission to abolish slavery. Women in the South supported their men in the fight to support states rights, specifically the right to own slaves.

Women were important actors in America’s most devastating war. On both sides of the conflict, as Unionist or Confederates, they supported the efforts of their troops, maintained life at home in the worst of circumstances, and cared for wounded and dying men on both sides of the conflict.

By the end of this era, so much remained in question. How would the nation come together again? What rights would be afforded to the formerly enslaved and the women who worked tirelessly in service of the nation? How would Southern women honor their lost loved ones and how does this create the image of the Confederacy that we see today?

Impact of War on Southern White Women:

In the South, where the majority of battles were fought, cities, towns and plantations were devastated. After enslaved people gained their freedom because of the Emancipation Proclamation, plantation mistresses experienced poverty for the first time. Many Union regiments salted the fields so they could not nourish crops, making it all the more difficult for southern women to run their farms.

Women were active in the physical and emotional care of battlefield wounded. Most nursing activity had previously been performed by male “stewards.” During the War, women became the primary caregivers for wounded and dying soldiers. In the North, white and free black women brought food, knitted socks, made bandages, wrote letters, and tended to the wounded, mainly as volunteers. In the Confederacy, enslaved women were required to perform nursing duties while their owners received compensation.

In the South, as the men went to fight, women assumed the duties of managing entire farms and plantations and the slaves that worked them. They often became the primary financial provider for their families, a responsibility that obliged them to procure jobs as nurses, matrons, treasury workers, teachers, and seamstresses. For the first time, elite women in South Carolina negotiated financial hardships, shifting cultural norms, political activities, and a radically altered perception of what it meant to be a Southern woman.

Phoebe Yates Pember, a Confederate nurse at the Chimborazo Hospital in Richmond, Virginia confided in her diary in the summer of 1864, that the confederate money was worthless, and that the weak Congress refused to raise the hospital fund to meet the depreciation of Confederate money. Inflation and Union blockades, alongside the destruction left behind after battles severely hindered the South’s ability to cloth and feed themselves.

Conclusion:

Whether working as soldiers, spies, volunteers, nurses, or staying home and maintaining the house women were active in the war effort. These ladies showed tremendous amounts of courage and strength as they supported either the Union or the Confederacy. Women in the North helped support the Union and its mission to abolish slavery. Women in the South supported their men in the fight to support states rights, specifically the right to own slaves.

Women were important actors in America’s most devastating war. On both sides of the conflict, as Unionist or Confederates, they supported the efforts of their troops, maintained life at home in the worst of circumstances, and cared for wounded and dying men on both sides of the conflict.

By the end of this era, so much remained in question. How would the nation come together again? What rights would be afforded to the formerly enslaved and the women who worked tirelessly in service of the nation? How would Southern women honor their lost loved ones and how does this create the image of the Confederacy that we see today?

Draw your own conclusions

|

Learn how to teach with inquiry.

Many of these lesson plans were sponsored in part by the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources Eastern Region Program, coordinated by Waynesburg University, the History and Social Studies Education Faculty at Plymouth State University, and the Patrons of the Remedial Herstory Project. |

Lesson Plans from Other Organizations

- The National Women's History Museum has lesson plans on women's history.

- The Gilder Lehrman Institute for American History has lesson plans on women's history.

- The NY Historical Society has articles and classroom activities for teaching women's history.

- Unladylike 2020, in partnership with PBS, has primary sources to explore with students and outstanding videos on women from the Progressive era.

- The Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media has produced recommendations for teaching women's history with primary sources and provided a collection of sources for world history. Check them out!

- The Stanford History Education Group has a number of lesson plans about women in World History.

Period Specific Lesson Plans from Other Organizations

- Library of Congress: Students will explore records from the U.S. House of Representatives to discover the story of Harriet Tubman’s Civil War service to the government and her petition to Congress for compensation. Although her service as a nurse, cook, and spy for the federal government is less well known than her work on the Underground Railroad, it was on that basis that she requested a federal pension after the War. Using historical thinking skills, students will examine the evidence of Tubman’s service and assess Congress’s decision to grant her a pension. Despite the endorsements of a number of highly ranked Civil War officials indicating the breadth of her service, Tubman ultimately secured a pension only as a widow of a Civil War veteran, not on the basis of her own service.

- National History Day: Clara Barton (1821-1912) grew up in North Oxford, Massachusetts. She began her career as a teacher at age 15. She moved to Washington, D.C. to work as a clerk at the U.S. Patent Office. As the Civil War broke out, she collected supplies for soldiers. In 1862, the U.S. Army granted her permission to bring food and medical supplies to field hospitals on the front without government support, earning her the nickname, “Angel of the Battlefield.” In 1864, General Benjamin Butler appointed her superintendent of the nurses. Following the war, she established the Bureau of Records of Missing Men of the Armies of the United States, locating over 22,000 missing men and reuniting them with families. In 1869 she traveled to Geneva, Switzerland as member of the the International Committee of the Red Cross. She returned to the United States and founded the American Red Cross in 1881. She remained president of the organization until 1904.

- PBS and DPLA: This collection uses primary sources to explore women in the Civil War. Digital Public Library of America Primary Source Sets are designed to help students develop their critical thinking skills and draw diverse material from libraries, archives, and museums across the United States. Each set includes an overview, ten to fifteen primary sources, links to related resources, and a teaching guide. These sets were created and reviewed by the teachers on the DPLA's Education Advisory Committee.

Hale: Letter To Lincoln

Permit me, as Editress of the "Lady's Book", to request a few minutes of your precious time, while laying before you a subject of deep interest to myself and -- as I trust -- even to the President of our Republic, of some importance. This subject is to have the day of our annual Thanksgiving made a National and fixed Union Festival.

You may have observed that, for some years past, there has been an increasing interest felt in our land to have the Thanksgiving held on the same day, in all the States; it now needs National recognition and authoritive fixation, only, to become permanently, an American custom and institution...

For the last fifteen years I have set forth this idea in the "Lady's Book", and placed the papers before the Governors of all the States and Territories... From the recipients I have received, uniformly the most kind approval...

But I find there are obstacles not possible to be overcome without legislative aid... it has ocurred to me that a proclamation from the President of the United States would be the best, surest and most fitting method of National appointment.

I have written to my friend, Hon. Wm. H. Seward, and requested him to confer with President Lincoln on this subject. As the President of the United States has the power... as well as duty, issue his proclamation for a Day of National Thanksgiving for all the above classes of persons? And would it not be fitting and patriotic for him to appeal to the Governors of all the States, inviting and commending these to unite in issuing proclamations for the last Thursday in November as the Day of Thanksgiving for the people of each State? Thus the great Union Festival of America would be established.

Now the purpose of this letter is to entreat President Lincoln to put forth his Proclamation, appointing the last Thursday in November (which falls this year on the 26th) as the National Thanksgiving...

An immediate proclamation would be necessary, so as to reach all the States in season for State appointments, also to anticipate the early appointments by Governors. Excuse the liberty I have taken

With profound respect

Yrs truly Sarah Josepha Hale,

Lincoln, Abraham. Abraham Lincoln papers: Series 1. General Correspondence. 1833 to 1916:

Sarah J. Hale to Abraham Lincoln, Monday,Thanksgiving. 1863. Manuscript/Mixed Material. https://www.loc.gov/item/mal2669900/.

Questions:

You may have observed that, for some years past, there has been an increasing interest felt in our land to have the Thanksgiving held on the same day, in all the States; it now needs National recognition and authoritive fixation, only, to become permanently, an American custom and institution...

For the last fifteen years I have set forth this idea in the "Lady's Book", and placed the papers before the Governors of all the States and Territories... From the recipients I have received, uniformly the most kind approval...

But I find there are obstacles not possible to be overcome without legislative aid... it has ocurred to me that a proclamation from the President of the United States would be the best, surest and most fitting method of National appointment.

I have written to my friend, Hon. Wm. H. Seward, and requested him to confer with President Lincoln on this subject. As the President of the United States has the power... as well as duty, issue his proclamation for a Day of National Thanksgiving for all the above classes of persons? And would it not be fitting and patriotic for him to appeal to the Governors of all the States, inviting and commending these to unite in issuing proclamations for the last Thursday in November as the Day of Thanksgiving for the people of each State? Thus the great Union Festival of America would be established.

Now the purpose of this letter is to entreat President Lincoln to put forth his Proclamation, appointing the last Thursday in November (which falls this year on the 26th) as the National Thanksgiving...

An immediate proclamation would be necessary, so as to reach all the States in season for State appointments, also to anticipate the early appointments by Governors. Excuse the liberty I have taken

With profound respect

Yrs truly Sarah Josepha Hale,

Lincoln, Abraham. Abraham Lincoln papers: Series 1. General Correspondence. 1833 to 1916:

Sarah J. Hale to Abraham Lincoln, Monday,Thanksgiving. 1863. Manuscript/Mixed Material. https://www.loc.gov/item/mal2669900/.

Questions:

- What is she requesting from Lincoln?

- Why do you think the idea of a National holiday might be popular during Lincoln's time?

Phoebe Yates Pember: Interview

“A preliminary interview with the surgeon-in-chief gave necessary confidence...Wisely

he decided to have an educated and efficient woman at the head of his hospital, and having

succeeded, never allowed himself to forget that fact... The day after my decision was made

found me at ‘headquarters,’ ... He had not yet made his appearance that morning, and while

waiting him, many of his corps, who had expected in horror the advent of female supervision,

walked in and out, evidently inspecting me. There was at that time a general ignorance on all

sides, except among the hospital officers, of the decided objection [of] “petticoat government;”

but there was no mistaking the stage-whisper which reached my ears from the open door of the

office that morning, as the little contract surgeon passed out and informed her friend he had met,

and it turned of ill concealed disgust, that ‘one of them had come.’”

Pember, P.Y. A Southern Woman's Story. New York: G. W. Carleton & Co., Publishers, 1879.

Questions:

he decided to have an educated and efficient woman at the head of his hospital, and having

succeeded, never allowed himself to forget that fact... The day after my decision was made

found me at ‘headquarters,’ ... He had not yet made his appearance that morning, and while

waiting him, many of his corps, who had expected in horror the advent of female supervision,

walked in and out, evidently inspecting me. There was at that time a general ignorance on all

sides, except among the hospital officers, of the decided objection [of] “petticoat government;”

but there was no mistaking the stage-whisper which reached my ears from the open door of the

office that morning, as the little contract surgeon passed out and informed her friend he had met,

and it turned of ill concealed disgust, that ‘one of them had come.’”

Pember, P.Y. A Southern Woman's Story. New York: G. W. Carleton & Co., Publishers, 1879.

Questions:

- What role did women play in the Civil War?

Clara Maclean: Quote

Teaching was one of the first waged jobs that women entered because it seemed to fit within the traditional woman’s sphere. Since it called on what had always been considered women’s natural maternal instincts and gifts as nurturers and instructors of the young. Additionally, it seemed only natural that as the supply of male teachers diminished due to their service in the Confederate army, the void should be filled by women entering a field that was both noble and befitting of their sex.

“I wish at times I could get entirely out of hearing of every child on earth... my lot is no harder than that which falls to the lot of every teacher. Since I have entered the list, the heart burning‘s, the tears, the bitterness always attending that occupation have become ‘household- words’ to me.”

Clara D. MacLean Diary, August 11, 1861.

Questions:

“I wish at times I could get entirely out of hearing of every child on earth... my lot is no harder than that which falls to the lot of every teacher. Since I have entered the list, the heart burning‘s, the tears, the bitterness always attending that occupation have become ‘household- words’ to me.”

Clara D. MacLean Diary, August 11, 1861.

Questions:

- What role did women play in the Civil War?

The Somerset Herald: She Was A Soldier

Massillow, O., May 31.-One of the red, white, and blue stakes of the G.A.R. is the only mark to show where lies the body of Mary Owens Jenkins in the village graveyard of West Brookfield, and it was developed yesterday by the veterans with honors equal to those bestowed upon any other of the grass grown mounds. Mrs. Jenkins, so far as is known at least, was the only woman soldier whose body sleeps in Ohio soil. At the breaking out of the war she was a Pennsylvania school girl, and being infatuated with a young man who had gone into the service, made up her mind to follow him. She cut her hair, put on a man’s clothing, and succeeded in passing the mustering officer. For two years she marched by this young man, shouldering her musket, and performing every duty required of men. In some manner they were separated, but she served out her time, was wounded in several places, and came up to Mahoning county, where she married Abraham Jenkins, who subsequently moved to the present home near Massillon. She died about fifteen years ago.

"She was a Soldier." The Somerset Herald (Somerset, Pa.), June 3, 1896.

Questions:

"She was a Soldier." The Somerset Herald (Somerset, Pa.), June 3, 1896.

Questions:

- Describe her role in the war.

- How did her life differ post serving?

Sarah E. E. Scelye: Explanation For Posing As A Soldier

“I had no other motive in enlisting than love to God and love for suffering humanity. I felt called to go and do what I could for the defense of the right; if I could not fight I could take the place of some one who could and thus add more soldiers to the ranks. I had no desire to be promoted to any office;I went with no other ambition than to nurse the sick and care for the wounded. I had inherited from my mother a rare gift of nursing, and when not too weary and exhausted, there was a magnetic power in my hands to soothe delirium.”

Steele, John L. "Disguised Her Sex To Go to War." The Washington Times, May 26, 1895.

Questions:

Steele, John L. "Disguised Her Sex To Go to War." The Washington Times, May 26, 1895.

Questions:

- Does religion play a role in her decision to go to war?

Maria Clark: Excerpt From Her Testimony

“On the Clark plantation in Hinds Co., until the battle of Vicksburg ended in [July] 1863, which

was the first time we knew we were free, all the slaves in the surrounding country was gathered

into a camp on a plantation about five miles from Vicksburg. We remained in this camp until

October 1863. My husband with others were sent up to Vicksburg to enlist. I went with him; he

was examined, pronounced sound and was accepted and went immediately into camps with the

troops, he was made a cook for the company. I followed and for several week I assisted him in

cooking....”

[ Maria Clark was a slave and the wife of Henry Clark, also a former slave, who

served in the Third Cavalry, United States Colored Troops]

Widow's Pension File, Henry Clark, United States Colored Troops, Cavalry, A Company, 3rd. Regiment, National Archives and Records Administration, (NARA), Washington, DC.

Questions:

was the first time we knew we were free, all the slaves in the surrounding country was gathered

into a camp on a plantation about five miles from Vicksburg. We remained in this camp until

October 1863. My husband with others were sent up to Vicksburg to enlist. I went with him; he

was examined, pronounced sound and was accepted and went immediately into camps with the

troops, he was made a cook for the company. I followed and for several week I assisted him in

cooking....”

[ Maria Clark was a slave and the wife of Henry Clark, also a former slave, who

served in the Third Cavalry, United States Colored Troops]

Widow's Pension File, Henry Clark, United States Colored Troops, Cavalry, A Company, 3rd. Regiment, National Archives and Records Administration, (NARA), Washington, DC.

Questions:

- How did black woman play a role in the Civil war?

Meta Morris Grimball: Account of Daily Activities

“A plantation life is a very active one. This morning I got up late having been disturbed in the night, hurried down to have some things arranged for breakfast, Ham and eggs; wrote a letter to Charles...Had prayers, got off the boys to town....Had work cut out, gave orders about dinner, had the horse feed fixed in hot water, had the bin filled with corn;--went to see about the carpenters working...and now I have to cut out flannel, jackets, and alter some work.”

Marli F. Weiner, Mistresses and Slaves: Plantation Women in South Carolina, 1830 to 1880 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1998), 25.

Questions:

Marli F. Weiner, Mistresses and Slaves: Plantation Women in South Carolina, 1830 to 1880 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1998), 25.

Questions:

- Describe the experience of white women during the Civil war?

Mary Chesnut: on Grief and the Loss of Loved Ones during the War

“A telegram reaches you, and you leave it on your lap. You are pale with fright. You handle it, or you dread to touch it, as you would a rattlesnake; worse, worse, a snake could only strike you. How many. Many will this scrap of paper tell you have gone to their death? “

“Grief and constant anxiety kill nearly as many women at home as men are killed on the battle- field.”

“Are our women losing the capacity to weep?”

Mary Boykin Chesnut, Mary Chesnut's Diary (New York: Penguin Books, 2011), 155-156,173.

Questions:

“Grief and constant anxiety kill nearly as many women at home as men are killed on the battle- field.”

“Are our women losing the capacity to weep?”

Mary Boykin Chesnut, Mary Chesnut's Diary (New York: Penguin Books, 2011), 155-156,173.

Questions:

- What issues were white women facing during the Civil War?

Grace Elmore: on the Flipping of the Gender Roles

“One thing they insist upon and that is to get away from the Yankee if possible. They do depend on us a great deal, and in fact their thoughts and time are so much occupied that they cannot attend to private matters. They belong to the country, that is all who are worth anything, and their private concerns have in a great measure ceased to engage much thought when thinking will do no good.”

Grace Brown Elmore, A Heritage of Woe: The Civil War Diary of Grace Brown Elmore, 1861-1868 ed. by Marli F. Weiner (Athens: The University of Georgia Press, 1997), 97.

Questions:

Grace Brown Elmore, A Heritage of Woe: The Civil War Diary of Grace Brown Elmore, 1861-1868 ed. by Marli F. Weiner (Athens: The University of Georgia Press, 1997), 97.

Questions:

- Summarize this source.

Sarah Edmonds: Book Excerpt

I was becoming dissatisfied with my situation as nurse, and was determined to leave the hospital; but before doing so I thought it best to call a council of three, Mr. and Mrs. B. and I, to decide what was the best course to pursue. After an hour’s conference together the matter was decided in my mind. Chaplain B. told me that he knew of a situation he could get for me if I had sufficient moral courage to undertake its duties; and, said he, “it is a situation of great danger and of vast responsibility.”

That morning a detachment of the Thirty-seventh New York had been sent out as scouts, and had returned bringing in several prisoners, who stated that one of the Federal spies had been captured at Richmond and was to be executed. This information proved to be correct, and we lost a valuable soldier from the secret service of the United States. Now it was necessary for that vacancy to be supplied, and, as the Chaplain had said with reference to it, it was a situation of great danger and vast responsibility, and this was the one which Mr. B. could procure for me. But was I capable of filling it with honor to myself and advantage to the Federal Government? This was an important question for me to consider ere I proceeded further. I did consider it thoroughly, and made up my mind to accept it with all its fearful responsibilities. The subject of life and death was not weighed in the balance; I left that in the hands of my Creator, feeling assured that I was just as safe in passing the picket lines of the enemy, if it was God’s will that I should go there, as I would be in the Federal camp. And if not, then His will be done: Then welcome death, the end of fears.

My name was sent in to headquarters, and I was soon summoned to appear there myself. Mr. and Mrs. B. accompanied me. We were ushered into the presence of Generals Mc., M. and H., where I was questioned and cross-questioned with regard to my views of the rebellion and my motive in wishing to engage in so perilous an undertaking. My views were freely given, my object briefly stated, and I had passed trial number one. Next I was examined with regard to my knowledge of the use of firearms, and in that department I sustained my character in a manner worthy of a veteran. Then I was again cross-questioned, but this time by a new committee of military stars.

Next came a phrenological examination, and finding that my organs of secretiveness, combativeness, etc., were largely developed, the oath of allegiance was administered, and I was dismissed with a few complimentary remarks which made the good Mr. B. feel quite proud of his protege. This was the third time that I had taken the oath of allegiance to the United States, and I began to think, as many of our soldiers do, that profanity had become a military necessity. I had three days in which to prepare for my debut into rebeldom, and I commenced at once to remodel, transform and metamorphose for the occasion. Early next morning I started for Fortress Monroe, where I procured a number of articles indispensably necessary to a complete disguise. In the first place I purchased a suit of contraband clothing, real plantation style, and then I went to a barber and had my hair sheared close to my head. Next came the coloring process—head, face, neck, hands and arms were colored black as any African, and then, to complete my contraband costume, I required a wig of real negro wool. But how or where was it to be found? There was no such thing at the Fortress, and none short of Washington. Happily I found the mail-boat was about to start, and hastened on board, and finding a Postmaster with whom I was acquainted, I stepped forward to speak to him, forgetting my contraband appearance, and was saluted with—“Well, Massa Cuff— what will you have?” Said I: “Massa send me to you wid dis yere money for you to fotch him a darkie wig from Washington.” “What the —— does he want of a darkie wig?” asked the Postmaster. “No matter, dat’s my orders; guess it’s for some ’noiterin’ business.” “Oh, for reconnoitering you mean; all right old fellow, I will bring it, tell him.” I remained at Fortress Monroe until the Postmaster returned with the article which was to complete my disguise, and then returned to camp near Yorktown.

On my return, I found myself without friends--a striking illustration of the frailty of human friendship--I had been forgotten in those three short days. I went to Mrs. B.’s tent and inquired if she wanted to hire a boy to take care of her horse. She was very civil to me, asked if I came from Fortress Monroe, and whether I could cook. She did not want to hire me, but she thought she could find some one who did require a boy. Off she went to Dr. E. and told him that there was a smart little contraband there who was in search of work. Dr. E. came along, looking as important as two year old doctors generally do. “Well, my boy, how much work can you do in a day?” “Oh, I reckon I kin work right smart; kin do heaps o’ work. Will you hire me, Massa?” “Don’t know but I may; can you cook?” “Yes, Massa, kin cook anything I ebber seen.” “How much do you think you can earn a month?” “Guess I kin earn ten dollars easy nuff.” Turning to Mrs. B. he said in an undertone: “That darkie understands his business.” “Yes indeed, I would hire him by all means, Doctor,” said Mrs. B. “Well, if you wish, you can stay with me a month, and by that time I will be a better judge how much you can earn.”

So saying Dr. E. proceeded to give a synopsis of a contraband’s duty toward a master of whom he expected ten dollars per month, especially emphasizing the last clause. Then I was introduced to the culinary department, which comprised flour, pork, beans, a small portable stove, a spider, and a medicine chest. It was now supper time, and I was supposed to understand my business sufficiently to prepare supper without asking any questions whatever, and also to display some of my boasted talents by making warm biscuit for supper. But how was I to make biscuit with my colored hands? and how dare I wash them for fear the color would wash off? All this trouble was soon put to an end, however, by Jack’s making his appearance while I was stirring up the biscuit with a stick, and in his bustling, officious, negro style, he said: “See here nig— you don’t know nuffin bout makin bisket. Jis let me show you once, and dat ar will save you heaps o’ trouble wid Massa doct’r for time to come.” I very willingly accepted of this proffered assistance, for I had all the necessary ingredients in the dish, with pork fat for shortening, and soda and cream-tartar, which I found in the medicine chest, ready for kneading and rolling out. After washing his hands and rolling up his sleeves, Jack went to work with a flourish and a grin of satisfaction at being “boss” over the new cook. Tea made, biscuit baked, and the medicine chest set off with tin cups, plates, etc., supper was announced. Dr. E. was much pleased with the general appearance of things, and was evidently beginning to think that he had found rather an intelligent contraband for a cook. [....]

I took the cars the next day and went to Lebanon--dressed in one of the rebel prisoner’s clothes—and thus disguised, made another trip to rebeldom. My business purported to be buying up butter and eggs, at the farmhouses, for the rebel army. I passed through the lines somewhere, without knowing it; for on coming to a little village toward evening, I found it occupied by a strong force of rebel cavalry. The first house I went to was filled with officers and citizens. I had stumbled upon a wedding party, unawares. Captain Logan, a recruiting officer, had been married that afternoon to a brilliant young widow whose husband had been killed in the rebel army a few months before. She had discovered that widow’s weeds were not becoming to her style of beauty, so had decided to appear once more in bridal costume, for a change.

I was questioned pretty sharply by the handsome captain in regard to the nature of my business in that locality, but finding me an innocent, straightforward Kentuckian, he came to the conclusion that I was all right. But he also arrived at the conclusion that I was old enough to be in the army, and bantered me considerably upon my want of patriotism.

The rebel soldier’s clothes which I wore did not indicate any thing more than that I was a Kentuckian--for their cavalry do not dress in any particular uniform, for scarcely two of them dress alike--the only uniformity being that they most generally dress in butternut color.

I tried to make my escape from that village as soon as possible, but just as I was beginning to congratulate myself upon my good fortune, who should confront me but Captain Logan. Said he: “See here, my lad; I think the best thing you can do is to enlist, and join a company which is just forming here in the village, and will leave in the morning. We are giving a bounty to all who freely enlist, and are conscripting those who refuse. Which do you propose to do, enlist and get the bounty, or refuse, and be obliged to go without anything?” I replied, “I think I shall wait a few days before I decide.” “But we can’t wait for you to decide,” said the captain; “the Yankees may be upon us any moment, for we are not far from their lines, and we will leave here either to-night or in the morning early. I will give you two hours to decide this question, and in the mean time you must be put under guard.” So saying, he marched me back with him, and gave me in charge of the guards. In two or three hours he came for my decision, and I told him that I had concluded to wait until I was conscripted. “Well,” said he, “you will not have long to wait for that, so you may consider yourself a soldier of the Confederacy from this hour, and subject to military discipline.”

This seemed to me like pretty serious business, especially as I would be required to take the oath of allegiance to the Confederate Government. However, I did not despair, but trusted in Providence and my own ingenuity [creativity] to escape from this dilemma [problem] also; and as I was not required to take the oath until the company was filled up, I was determined to be among the missing ere it became necessary for me to make any professions of loyalty to the rebel cause. I knew that if I should refuse to be sworn into the service after I was conscripted [enlisted], that in all probability my true character would be suspected, and I would have to suffer the penalty of death--and that, too, in the most barbarous manner.

I was glad to find that it was a company of cavalry that was being organized, for if I could once get on a good horse there would be some hope of my escape. There was no time to be lost, as the captain remarked, for the Yankees might make a dash upon us at any moment; consequently a horse and saddle was furnished me, and everything was made ready for a start immediately. Ten o’clock came, and we had not yet started. The captain finally concluded that, as everything seemed quiet, we would not start until daylight.

Music and dancing was kept up all night, and it was some time after daylight when the captain made his appearance. A few moments more and we were trotting briskly over the country, the captain complimenting me upon my horsemanship, and telling me how grateful I would be to him when the war was over and the South had gained her independence, and that I would be proud that I had been one of the soldiers of the Southern confederacy, who had steeped my saber in Yankee blood, and driven the vandals from our soil. “Then,” said he, “you will thank me for the interest which I have taken in you, and for the gentle persuasives which I made use of to stir up your patriotism and remind you of your duty to your country.”

In this manner we had traveled about half an hour, when we suddenly encountered a reconnoitering [scouting] party of the Federals, cavalry in advance, and infantry in the rear. A contest soon commenced; we were ordered to advance in line, which we did, until we came within a few yards of the Yankees.

The company advanced, but my horse suddenly became unmanageable, and it required a second or two to bring him right again; and before I could overtake the company and get in line the contending parties had met in a hand to hand fight.

All were engaged, so that when I, by accident, got on the Federal side of the line, none observed me for several minutes, except the Federal officer, who had recognized me and signed to me to fall in next to him. That brought me face to face with my rebel captain, to whom I owed such a debt of gratitude. Thinking this would be a good time to cancel all obligations in that direction, I discharged the contents of my pistol in his face.

This act made me the center of attraction. Every rebel seemed determined to have the pleasure of killing me first, and a simultaneous dash was made toward me and numerous saber strokes aimed at my head. Our men with one accord rushed between me and the enemy, and warded off the blows with their sabers, and attacked them with such fury that they were driven back several rods.

The infantry now came up and deployed as skirmishers, and succeeded in getting a position where they had a complete cross-fire on the rebels, and poured in volley after volley until nearly half their number lay upon the ground. Finding it useless to fight longer at such a disadvantage they turned and fled, leaving behind them eleven killed, twenty-nine wounded, and seventeen prisoners.

The confederate captain was wounded badly but not mortally; his handsome face was very much disfigured, a part of his nose and nearly half of his upper lip being shot away. I was sorry, for the graceful curve of his mustache was sadly spoiled, and the happy bride of the previous morning would no longer rejoice in the beauty of that manly face and exquisite mustache of which she seemed so proud, and which had captivated her heart ere she had been three months a widow.

Our men suffered considerable loss before the infantry came up, but afterward scarcely lost a man. I escaped without receiving a scratch, but my horse was badly cut across the neck with a saber, but which did not injure him materially, only for a short time.

After burying the dead, Federal and rebel, we returned to camp with our prisoners and wounded, and I rejoiced at having once more escaped from the confederate lines.

I was highly commended by the commanding general for my coolness throughout the whole affair, and was told kindly and candidly that I would not be permitted to go out again in that vicinity, in the capacity of spy, as I would most assuredly meet with some of those who had seen me desert their ranks, and I would consequently be hung up to the nearest tree.

Not having any particular fancy for such an exalted position, and not at all ambitious of having my name handed down to posterity among the list of those who “expiated their crimes upon the gallows,” I turned my attention to more quiet and less dangerous duties.

Edmonds, Sarah Emma. Nurse and Spy in the Union Army: The Adventures and Experiences of a Woman in Hospitals, Camps, and Battle-Fields. Hartford: W. S. Williams & Co., 1865.

Questions:

That morning a detachment of the Thirty-seventh New York had been sent out as scouts, and had returned bringing in several prisoners, who stated that one of the Federal spies had been captured at Richmond and was to be executed. This information proved to be correct, and we lost a valuable soldier from the secret service of the United States. Now it was necessary for that vacancy to be supplied, and, as the Chaplain had said with reference to it, it was a situation of great danger and vast responsibility, and this was the one which Mr. B. could procure for me. But was I capable of filling it with honor to myself and advantage to the Federal Government? This was an important question for me to consider ere I proceeded further. I did consider it thoroughly, and made up my mind to accept it with all its fearful responsibilities. The subject of life and death was not weighed in the balance; I left that in the hands of my Creator, feeling assured that I was just as safe in passing the picket lines of the enemy, if it was God’s will that I should go there, as I would be in the Federal camp. And if not, then His will be done: Then welcome death, the end of fears.

My name was sent in to headquarters, and I was soon summoned to appear there myself. Mr. and Mrs. B. accompanied me. We were ushered into the presence of Generals Mc., M. and H., where I was questioned and cross-questioned with regard to my views of the rebellion and my motive in wishing to engage in so perilous an undertaking. My views were freely given, my object briefly stated, and I had passed trial number one. Next I was examined with regard to my knowledge of the use of firearms, and in that department I sustained my character in a manner worthy of a veteran. Then I was again cross-questioned, but this time by a new committee of military stars.

Next came a phrenological examination, and finding that my organs of secretiveness, combativeness, etc., were largely developed, the oath of allegiance was administered, and I was dismissed with a few complimentary remarks which made the good Mr. B. feel quite proud of his protege. This was the third time that I had taken the oath of allegiance to the United States, and I began to think, as many of our soldiers do, that profanity had become a military necessity. I had three days in which to prepare for my debut into rebeldom, and I commenced at once to remodel, transform and metamorphose for the occasion. Early next morning I started for Fortress Monroe, where I procured a number of articles indispensably necessary to a complete disguise. In the first place I purchased a suit of contraband clothing, real plantation style, and then I went to a barber and had my hair sheared close to my head. Next came the coloring process—head, face, neck, hands and arms were colored black as any African, and then, to complete my contraband costume, I required a wig of real negro wool. But how or where was it to be found? There was no such thing at the Fortress, and none short of Washington. Happily I found the mail-boat was about to start, and hastened on board, and finding a Postmaster with whom I was acquainted, I stepped forward to speak to him, forgetting my contraband appearance, and was saluted with—“Well, Massa Cuff— what will you have?” Said I: “Massa send me to you wid dis yere money for you to fotch him a darkie wig from Washington.” “What the —— does he want of a darkie wig?” asked the Postmaster. “No matter, dat’s my orders; guess it’s for some ’noiterin’ business.” “Oh, for reconnoitering you mean; all right old fellow, I will bring it, tell him.” I remained at Fortress Monroe until the Postmaster returned with the article which was to complete my disguise, and then returned to camp near Yorktown.

On my return, I found myself without friends--a striking illustration of the frailty of human friendship--I had been forgotten in those three short days. I went to Mrs. B.’s tent and inquired if she wanted to hire a boy to take care of her horse. She was very civil to me, asked if I came from Fortress Monroe, and whether I could cook. She did not want to hire me, but she thought she could find some one who did require a boy. Off she went to Dr. E. and told him that there was a smart little contraband there who was in search of work. Dr. E. came along, looking as important as two year old doctors generally do. “Well, my boy, how much work can you do in a day?” “Oh, I reckon I kin work right smart; kin do heaps o’ work. Will you hire me, Massa?” “Don’t know but I may; can you cook?” “Yes, Massa, kin cook anything I ebber seen.” “How much do you think you can earn a month?” “Guess I kin earn ten dollars easy nuff.” Turning to Mrs. B. he said in an undertone: “That darkie understands his business.” “Yes indeed, I would hire him by all means, Doctor,” said Mrs. B. “Well, if you wish, you can stay with me a month, and by that time I will be a better judge how much you can earn.”

So saying Dr. E. proceeded to give a synopsis of a contraband’s duty toward a master of whom he expected ten dollars per month, especially emphasizing the last clause. Then I was introduced to the culinary department, which comprised flour, pork, beans, a small portable stove, a spider, and a medicine chest. It was now supper time, and I was supposed to understand my business sufficiently to prepare supper without asking any questions whatever, and also to display some of my boasted talents by making warm biscuit for supper. But how was I to make biscuit with my colored hands? and how dare I wash them for fear the color would wash off? All this trouble was soon put to an end, however, by Jack’s making his appearance while I was stirring up the biscuit with a stick, and in his bustling, officious, negro style, he said: “See here nig— you don’t know nuffin bout makin bisket. Jis let me show you once, and dat ar will save you heaps o’ trouble wid Massa doct’r for time to come.” I very willingly accepted of this proffered assistance, for I had all the necessary ingredients in the dish, with pork fat for shortening, and soda and cream-tartar, which I found in the medicine chest, ready for kneading and rolling out. After washing his hands and rolling up his sleeves, Jack went to work with a flourish and a grin of satisfaction at being “boss” over the new cook. Tea made, biscuit baked, and the medicine chest set off with tin cups, plates, etc., supper was announced. Dr. E. was much pleased with the general appearance of things, and was evidently beginning to think that he had found rather an intelligent contraband for a cook. [....]

I took the cars the next day and went to Lebanon--dressed in one of the rebel prisoner’s clothes—and thus disguised, made another trip to rebeldom. My business purported to be buying up butter and eggs, at the farmhouses, for the rebel army. I passed through the lines somewhere, without knowing it; for on coming to a little village toward evening, I found it occupied by a strong force of rebel cavalry. The first house I went to was filled with officers and citizens. I had stumbled upon a wedding party, unawares. Captain Logan, a recruiting officer, had been married that afternoon to a brilliant young widow whose husband had been killed in the rebel army a few months before. She had discovered that widow’s weeds were not becoming to her style of beauty, so had decided to appear once more in bridal costume, for a change.

I was questioned pretty sharply by the handsome captain in regard to the nature of my business in that locality, but finding me an innocent, straightforward Kentuckian, he came to the conclusion that I was all right. But he also arrived at the conclusion that I was old enough to be in the army, and bantered me considerably upon my want of patriotism.

The rebel soldier’s clothes which I wore did not indicate any thing more than that I was a Kentuckian--for their cavalry do not dress in any particular uniform, for scarcely two of them dress alike--the only uniformity being that they most generally dress in butternut color.

I tried to make my escape from that village as soon as possible, but just as I was beginning to congratulate myself upon my good fortune, who should confront me but Captain Logan. Said he: “See here, my lad; I think the best thing you can do is to enlist, and join a company which is just forming here in the village, and will leave in the morning. We are giving a bounty to all who freely enlist, and are conscripting those who refuse. Which do you propose to do, enlist and get the bounty, or refuse, and be obliged to go without anything?” I replied, “I think I shall wait a few days before I decide.” “But we can’t wait for you to decide,” said the captain; “the Yankees may be upon us any moment, for we are not far from their lines, and we will leave here either to-night or in the morning early. I will give you two hours to decide this question, and in the mean time you must be put under guard.” So saying, he marched me back with him, and gave me in charge of the guards. In two or three hours he came for my decision, and I told him that I had concluded to wait until I was conscripted. “Well,” said he, “you will not have long to wait for that, so you may consider yourself a soldier of the Confederacy from this hour, and subject to military discipline.”

This seemed to me like pretty serious business, especially as I would be required to take the oath of allegiance to the Confederate Government. However, I did not despair, but trusted in Providence and my own ingenuity [creativity] to escape from this dilemma [problem] also; and as I was not required to take the oath until the company was filled up, I was determined to be among the missing ere it became necessary for me to make any professions of loyalty to the rebel cause. I knew that if I should refuse to be sworn into the service after I was conscripted [enlisted], that in all probability my true character would be suspected, and I would have to suffer the penalty of death--and that, too, in the most barbarous manner.

I was glad to find that it was a company of cavalry that was being organized, for if I could once get on a good horse there would be some hope of my escape. There was no time to be lost, as the captain remarked, for the Yankees might make a dash upon us at any moment; consequently a horse and saddle was furnished me, and everything was made ready for a start immediately. Ten o’clock came, and we had not yet started. The captain finally concluded that, as everything seemed quiet, we would not start until daylight.

Music and dancing was kept up all night, and it was some time after daylight when the captain made his appearance. A few moments more and we were trotting briskly over the country, the captain complimenting me upon my horsemanship, and telling me how grateful I would be to him when the war was over and the South had gained her independence, and that I would be proud that I had been one of the soldiers of the Southern confederacy, who had steeped my saber in Yankee blood, and driven the vandals from our soil. “Then,” said he, “you will thank me for the interest which I have taken in you, and for the gentle persuasives which I made use of to stir up your patriotism and remind you of your duty to your country.”