2. To 15,000 Mother Earth and Great Goddesses?

Female goddesses in all their sexualized glory can be found across the globe in the ancient world. What can these goddesses tell us about pre-historic and ancient faiths, and what can they tell us about gender dynamics? Quite a lot. Was there ever a great goddess-- more powerful than the male gods? Probably not.

During the Paleolithic Era, (3.3 million to about 12,000 years ago) people lived in caves, huts, or tepees. They gathered and hunted for food, used basic stone and bone tools, as well as crude stone axes for hunting birds and wild animals. Women and men shared responsibilities and were mutually reliant on one another, but this relationship shifted with the advent of settled agriculture. Everywhere around the world, female goddesses or feminine beings appeared in the religions that formed during this period. Who were these goddesses? And where did they go?

Religion

Religions during the Paleolithic era were distinctly different from modern religions. They were heavily influenced by nature, were usually polytheistic, and, importantly, they honored almost as many female goddesses as male gods. Some also made little distinction between male and female or did not have gendered characteristics. Goddesses and gods were thought to have power over many aspects of human life, and worshipers would pray to a particular god or goddess to address a particular need or problem. Worship was ritualistic, spiritual, and varied from society to society, region to region. Sexuality was evidently important as images of gods and goddesses showed extenuated genitalia, and many of the early myths included details of procreation.

Religion

Religions during the Paleolithic era were distinctly different from modern religions. They were heavily influenced by nature, were usually polytheistic, and, importantly, they honored almost as many female goddesses as male gods. Some also made little distinction between male and female or did not have gendered characteristics. Goddesses and gods were thought to have power over many aspects of human life, and worshipers would pray to a particular god or goddess to address a particular need or problem. Worship was ritualistic, spiritual, and varied from society to society, region to region. Sexuality was evidently important as images of gods and goddesses showed extenuated genitalia, and many of the early myths included details of procreation.

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

The historical record is sprinkled with textual evidence of a matriarchal or divine feminine past that would have been passed down for centuries by oral tradition and later recorded. One ancient Indian saying stated, “Woman is the Creator of the Universe, the Universe is her form. Woman is the foundation of the world. There is no prayer equal to a woman, there is not, nor has been, nor will there be any yoga to compare with a woman, no mystical formula nor asceticism to match a woman.”

The historical record is sprinkled with textual evidence of a matriarchal or divine feminine past that was passed down for centuries by oral tradition and later recorded. One ancient Indian proverb stated, “Woman is the Creator of the Universe, the Universe is her form. Woman is the foundation of the world.There is no prayer equal to a woman, there is not, nor has been, nor will there be anyyoga to compare with a woman, no mystical formula nor asceticism to match a woman.”

Mesopotamia was among the first civilizations with recorded history. At first, gods and goddesses were represented as gender fluid. Later, gods and goddesses exemplified characteristics later associated with one gender or another. None demonstrates this more than Inanna. She was the goddess of love, beauty, sex, war, justice, and political power.

A Mesopotamian hymn from the Sumerian city states describes Ianna as a virgin who wanted to know more about sex. She asks her brother to take her to the underworld where she could taste the fruit of a tree that grows there and thus learn about sex. This story was passed down over centuries and was eventually transformed into the Adam and Eve tale recorded in the Torah, or Old Testament by authors in the 6th century BCE.

Inanna begins a courtship and eventually chooses the God of Shepherds. There are several versions of their relationship. In one, she goes on an epic journey to save him from the underworld. As she ventures into the underworld, she passes through seven gates, at each she must strip off a layer of her clothing. This is intended to humiliate and destroy her power. When she arrives, she is completely naked. Eventually, the God of Shepherds is permitted to visit Ianna for half the year but must stay in the underworld the other half. In other versions, Inanna killed him.

Inanna evolved into the character of Ishtar by 2500 BCE. Some Mesopotamian empires elevated her to the highest deity in their pantheon–-even over their national gods. Ishtar’s strength and fearsomeness is featured in the oldest story in the world, The Epic of Gilgamesh, written between 2900 BCE and 2350 BCE. The epic includes fantastic adventure tales and tales of women taming men, but it also holds warnings about female power and sexuality. In one tale, Ishtar falls in love with the King, Gilgamesh, but he rejects her because she had killed her previous lovers. Gilgamesh asked her, “Which of your lovers did you love forever? What shepherd of yours pleased you for all time?... And if you and I should be lovers, should not I be served in the same fashion as all these others whom you loved once?”

Facing rejection, Ishtar got a demonic bull to terrorize Uruk and cause widespread devastation. The bull lowered the level of the Euphrates river, and dried up the marshes. It opened up huge pits that swallowed 300 men. Without any divine assistance, Enkidu and Gilgamesh were able to kill it. Ishtar mourned with the courtesans and harlots, while Gilgamesh celebrated with the craftsmen switching loyalty to the Sun God.

Later in the Epic of Gilgamesh, we read of the Great Flood, which resembles the story of Noah’s ark in the Old Testament. According to the epic, when the flood came, Ishtar mourned the destruction of humanity and swore to stop future floods. Archeologists have found hundreds of clay cylinders depicting scenes from the epic that were used to help generations learn and remember these important tales.

Temples were devoted to Ishtar through different empires in Mesopotamia, and the lion icon most associated with her is displayed prominently in the region. Ishtar continued to thrive long after the Greek and Romans conquered the region. She likely influenced the development of the Greek goddess Aphrodite. A cult to her continued to flourish until its gradual decline between the first and sixth centuries CE in the wake of Christianity.

The historical record is sprinkled with textual evidence of a matriarchal or divine feminine past that was passed down for centuries by oral tradition and later recorded. One ancient Indian proverb stated, “Woman is the Creator of the Universe, the Universe is her form. Woman is the foundation of the world.There is no prayer equal to a woman, there is not, nor has been, nor will there be anyyoga to compare with a woman, no mystical formula nor asceticism to match a woman.”

Mesopotamia was among the first civilizations with recorded history. At first, gods and goddesses were represented as gender fluid. Later, gods and goddesses exemplified characteristics later associated with one gender or another. None demonstrates this more than Inanna. She was the goddess of love, beauty, sex, war, justice, and political power.

A Mesopotamian hymn from the Sumerian city states describes Ianna as a virgin who wanted to know more about sex. She asks her brother to take her to the underworld where she could taste the fruit of a tree that grows there and thus learn about sex. This story was passed down over centuries and was eventually transformed into the Adam and Eve tale recorded in the Torah, or Old Testament by authors in the 6th century BCE.

Inanna begins a courtship and eventually chooses the God of Shepherds. There are several versions of their relationship. In one, she goes on an epic journey to save him from the underworld. As she ventures into the underworld, she passes through seven gates, at each she must strip off a layer of her clothing. This is intended to humiliate and destroy her power. When she arrives, she is completely naked. Eventually, the God of Shepherds is permitted to visit Ianna for half the year but must stay in the underworld the other half. In other versions, Inanna killed him.

Inanna evolved into the character of Ishtar by 2500 BCE. Some Mesopotamian empires elevated her to the highest deity in their pantheon–-even over their national gods. Ishtar’s strength and fearsomeness is featured in the oldest story in the world, The Epic of Gilgamesh, written between 2900 BCE and 2350 BCE. The epic includes fantastic adventure tales and tales of women taming men, but it also holds warnings about female power and sexuality. In one tale, Ishtar falls in love with the King, Gilgamesh, but he rejects her because she had killed her previous lovers. Gilgamesh asked her, “Which of your lovers did you love forever? What shepherd of yours pleased you for all time?... And if you and I should be lovers, should not I be served in the same fashion as all these others whom you loved once?”

Facing rejection, Ishtar got a demonic bull to terrorize Uruk and cause widespread devastation. The bull lowered the level of the Euphrates river, and dried up the marshes. It opened up huge pits that swallowed 300 men. Without any divine assistance, Enkidu and Gilgamesh were able to kill it. Ishtar mourned with the courtesans and harlots, while Gilgamesh celebrated with the craftsmen switching loyalty to the Sun God.

Later in the Epic of Gilgamesh, we read of the Great Flood, which resembles the story of Noah’s ark in the Old Testament. According to the epic, when the flood came, Ishtar mourned the destruction of humanity and swore to stop future floods. Archeologists have found hundreds of clay cylinders depicting scenes from the epic that were used to help generations learn and remember these important tales.

Temples were devoted to Ishtar through different empires in Mesopotamia, and the lion icon most associated with her is displayed prominently in the region. Ishtar continued to thrive long after the Greek and Romans conquered the region. She likely influenced the development of the Greek goddess Aphrodite. A cult to her continued to flourish until its gradual decline between the first and sixth centuries CE in the wake of Christianity.

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

In Hinduism, the world’s oldest religion still practiced today, there is a long tradition of Goddess worship. This divine feminine is known as Devi, the Goddess, or “‘Great Mother.” She is the embodiment of Shakti, the “creative power of the universe.” While this power is eternal and formless, all other Hindu goddesses are considered to be manifestations of Devi. Devi is not the consort of a male deity– she is independent. In some traditions Devi is even regarded as superior to male deities. Shaktism acknowledges the creative potential of women who maintain familial and social order. Shakti is also considered the counterpart of the masculine Purusha (spirit), but neither can survive without the other, suggesting a model for gender equality.

Many Aztec gods were genderless or exhibited dual gender characteristics. The Aztec goddess Coatlicue was considered the mother of all gods who embodied opposites: life and death, light and dark, male and female. Almost all representations of Coatilcue depict her deadly side because Earth is a loving mother as well as an insatiable monster that consumes everything that lives. She represents the devouring mother, in whom both the womb and the grave exist.

Creation Stories

Creation stories were recorded in almost every world culture and give us great insight into the oral traditions passed down for millennia.

This is the story of the Chinese goddess Nuwa: in the beginning, surrounded by chaos was a sleeping giant named Pángǔ. The hairy horned giant woke up and, upon standing, split the heavens and the earth. After thousands of years, he died and his body became the sun, moon, stars, mountains, rivers and forests and all else in creation. From this primordial creation, the goddess Nǚwā arrived and found that the four pillars holding heaven and earth apart were broken, so she repaired them. She then fashioned mankind from clay.

In some narratives, creation stories seem disjointed, as if combining different myths. The book of Genesis is clearly a combination of a variety of oral myths recorded. The first chapter God creates the earth from a void in six days, but in the second chapter, a heavenly garden appears out of nowhere and God creates a man in his image and creates a woman from his rib. At another point in the narrative, God is said to have created man and woman in his image, thus contradicting the story of Adam’s rib. The woman convinces the man to eat from the tree of knowledge, and both are doomed to a life of labor and trouble. Linguists studying the ancient texts have noted that different authors recorded these two stories because the Hebrew words they use for God changed from story to story (in the King James Version this is represented by using the words God and Lord). In the case of the flood, the parallels with Ishtar’s story are obvious.

Many Aztec gods were genderless or exhibited dual gender characteristics. The Aztec goddess Coatlicue was considered the mother of all gods who embodied opposites: life and death, light and dark, male and female. Almost all representations of Coatilcue depict her deadly side because Earth is a loving mother as well as an insatiable monster that consumes everything that lives. She represents the devouring mother, in whom both the womb and the grave exist.

Creation Stories

Creation stories were recorded in almost every world culture and give us great insight into the oral traditions passed down for millennia.

This is the story of the Chinese goddess Nuwa: in the beginning, surrounded by chaos was a sleeping giant named Pángǔ. The hairy horned giant woke up and, upon standing, split the heavens and the earth. After thousands of years, he died and his body became the sun, moon, stars, mountains, rivers and forests and all else in creation. From this primordial creation, the goddess Nǚwā arrived and found that the four pillars holding heaven and earth apart were broken, so she repaired them. She then fashioned mankind from clay.

In some narratives, creation stories seem disjointed, as if combining different myths. The book of Genesis is clearly a combination of a variety of oral myths recorded. The first chapter God creates the earth from a void in six days, but in the second chapter, a heavenly garden appears out of nowhere and God creates a man in his image and creates a woman from his rib. At another point in the narrative, God is said to have created man and woman in his image, thus contradicting the story of Adam’s rib. The woman convinces the man to eat from the tree of knowledge, and both are doomed to a life of labor and trouble. Linguists studying the ancient texts have noted that different authors recorded these two stories because the Hebrew words they use for God changed from story to story (in the King James Version this is represented by using the words God and Lord). In the case of the flood, the parallels with Ishtar’s story are obvious.

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

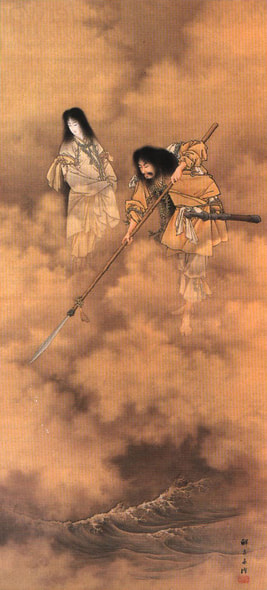

In Japan, ancient origin stories were recorded in a text called The Kojiki between 500-700 CE. As in the common rendition of Genesis, the earth is created from nothing by a few deities. The story goes, “Izanami examined her body and found that one place had not grown, and she told this to Izanagi, who replied that his body was well-formed but that one place had grown to excess. He proposed that he place his excess in her place that was not complete and that in doing so they would make new land. She greeted him by saying "What a fine young man". They procreated and gave birth to a leech-child, which they put in a basket and let float away for they did not recognize it as one of their children. Disappointed by their failures in procreation, they consulted the deities who explained that the cause of their difficulties was that the female had spoken first when they met to procreate. Izanagi and Izanami returned to their island and again met behind the heavenly pillar. When they met, he said, "What a fine young woman," and they mated and gave birth to the eight main islands of Japan and six minor islands.”

Many aboriginal myths attempt to explain the superiority of men but also suggest that there was once a time when women dominated. In one of the aboriginal myths, the “man eater,” is outwitted by the local men. It begins, “In the dream time, in the land of the Murinbata people, a great river floats from the hills through a wide plane to the Sea where lived an old woman named Mutujinga, A woman of power, she could speak with the spirits. Because she had this power, she could do many things which the men could not. She could send their spirits to frighten game away or cause a child to be born without life. The men feared the power of Mutujinga and did not consort with her. Mutujinga found no satisfaction in food, for she craved the flesh of men!” She created an elaborate trap for unsuspecting men and after one went missing, the men folk came to investigate. They forced her and her daughter to reveal their secrets and took control of what had once been mystical.

A Great Goddess?

One historian explained: “The prevalence of the Venus figurines and other symbols all across Europe has convinced some, but not all, scholars the Paleolithic religious thought had a strongly feminine dimension, embodied in a great goddess and concerned with the regeneration and renewal of life.” Was it possible there was a time when a goddess reigned supreme?

There is some evidence that goddesses were honored above the male gods. The most compelling part of this theory is our evolutionary ancestors’ inability to perceive cause and effect, thereby their inability to understand birth. To them, women were magical, capable of producing offspring out of nowhere. Every month, in sync with the moon cycle, women bled and didn’t die. Women produced life-sustaining milk.

When Sir Arthur Evans revealed the existence of the lost Minoans civilization to Europeans in the 20th century, he believed the goddess figurines he found represented the Great Mother, worshiped under various names and titles. This Great Goddess was the creation mother and in full control of all other gods.

Many aboriginal myths attempt to explain the superiority of men but also suggest that there was once a time when women dominated. In one of the aboriginal myths, the “man eater,” is outwitted by the local men. It begins, “In the dream time, in the land of the Murinbata people, a great river floats from the hills through a wide plane to the Sea where lived an old woman named Mutujinga, A woman of power, she could speak with the spirits. Because she had this power, she could do many things which the men could not. She could send their spirits to frighten game away or cause a child to be born without life. The men feared the power of Mutujinga and did not consort with her. Mutujinga found no satisfaction in food, for she craved the flesh of men!” She created an elaborate trap for unsuspecting men and after one went missing, the men folk came to investigate. They forced her and her daughter to reveal their secrets and took control of what had once been mystical.

A Great Goddess?

One historian explained: “The prevalence of the Venus figurines and other symbols all across Europe has convinced some, but not all, scholars the Paleolithic religious thought had a strongly feminine dimension, embodied in a great goddess and concerned with the regeneration and renewal of life.” Was it possible there was a time when a goddess reigned supreme?

There is some evidence that goddesses were honored above the male gods. The most compelling part of this theory is our evolutionary ancestors’ inability to perceive cause and effect, thereby their inability to understand birth. To them, women were magical, capable of producing offspring out of nowhere. Every month, in sync with the moon cycle, women bled and didn’t die. Women produced life-sustaining milk.

When Sir Arthur Evans revealed the existence of the lost Minoans civilization to Europeans in the 20th century, he believed the goddess figurines he found represented the Great Mother, worshiped under various names and titles. This Great Goddess was the creation mother and in full control of all other gods.

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

The divine feminine is present in nearly all early mythology, and she represents creation. Ishtar is considered the cosmic uterus. The Roman mother earth Gaea and the Norse Ymir emerged from a birth canal. In Egypt, the goddess Nut makes an even stronger claim for power in an engraving, “I am what is, what will be, and what has been. No man has uncovered my nakedness, and the fruit of my birthing was the sun.”

Many scholars take issue with the theory that these goddesses ever served as a Great Goddess. In Gentlemen and Amazons: The Myth of Matriarchal Prehistory, 1861–1900, Historian Cynthia Eller explained how attractive this theory is to her as a woman and yet how improbable it is. She dismisses the theory as wishful fantasy of a utopia. Eller adds, “The myth of matriarchal prehistory is not a feminist creation, in spite of the aggressively feminist spin it has carried over the past 25 years. The majority of men who champion the myth of matriarchal prehistory during its first century (and have mostly been men) have regarded patriarchy as an evolutionary advance over prehistoric matriarchies. If the myth now functions in a feminist way, its anti-feminist past can become merely a curious historical footnote.”

Whether or not a Great Goddess existed, these stories tell us how human development was similar across the globe and that, at one point, feminine attributes were considered divine. Eventually, feminine attributes were replaced in most of the world by a single male God with male prophets or messengers. It also shows us how important nature, procreation, and mystery were to early people.

By the end of this era, so much remained in question. Can we know for sure if there ever was a Great Goddess? How reliable are oral traditions recorded centuries or millennia after they were first told as evidence of prehistoric culture? What happened to these goddesses as communities settled and adapted agriculture?

Many scholars take issue with the theory that these goddesses ever served as a Great Goddess. In Gentlemen and Amazons: The Myth of Matriarchal Prehistory, 1861–1900, Historian Cynthia Eller explained how attractive this theory is to her as a woman and yet how improbable it is. She dismisses the theory as wishful fantasy of a utopia. Eller adds, “The myth of matriarchal prehistory is not a feminist creation, in spite of the aggressively feminist spin it has carried over the past 25 years. The majority of men who champion the myth of matriarchal prehistory during its first century (and have mostly been men) have regarded patriarchy as an evolutionary advance over prehistoric matriarchies. If the myth now functions in a feminist way, its anti-feminist past can become merely a curious historical footnote.”

Whether or not a Great Goddess existed, these stories tell us how human development was similar across the globe and that, at one point, feminine attributes were considered divine. Eventually, feminine attributes were replaced in most of the world by a single male God with male prophets or messengers. It also shows us how important nature, procreation, and mystery were to early people.

By the end of this era, so much remained in question. Can we know for sure if there ever was a Great Goddess? How reliable are oral traditions recorded centuries or millennia after they were first told as evidence of prehistoric culture? What happened to these goddesses as communities settled and adapted agriculture?

Draw your own conclusions

|

Learn how to teach with inquiry.

Many of these lesson plans were sponsored in part by the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources Eastern Region Program, coordinated by Waynesburg University, the History and Social Studies Education Faculty at Plymouth State University, and the Patrons of the Remedial Herstory Project. |

Lesson Plans from Other Organizations

- This website, Women in World History has primary source based lesson plans on women's history in a whole range of topics. Some are free while others have a cost.

- The Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media has produced recommendations for teaching women's history with primary sources and provided a collection of sources for world history. Check them out!

- The Stanford History Education Group has a number of lesson plans about women in World History.

Kojiki: Record of Ancient Things

This story is from the Kojiki, the Japanese "Record of Ancient Things". This story was among many that were recorded between 500-700CE to preserve the ancient traditions. The following story is the closest to a creation story there is in this text.

When heaven and earth began, three deities came into being, The Spirit Master of the Center of Heaven, The August Wondrously Producing Spirit, and the Divine Wondrously Producing Ancestor. These three were invisible. The earth was young then, and land floated like oil, and from it reed shoots sprouted. From these reeds came two more deities. After them, five or six pairs of deities came into being, and the last of these were Izanagi and Izanami, whose names mean "The Male Who Invites" and "The Female who Invites".

The first five deities commanded Izanagi and Izanami to make and solidify the land of Japan, and they gave the young pair a jeweled spear. Standing on the Floating Bridge of Heaven, they dipped it in the ocean brine and stirred. They pulled out the spear, and the brine that dripped of it formed an island to which they descended. On this island they built a palace for their wedding and a great column to the heavens.

Izanami examined her body and found that one place had not grown, and she told this to Izanagi, who replied that his body was well-formed but that one place had grown to excess. He proposed that he place his excess in her place that was not complete and that in doing so they would make new land. They agreed to walk around the pillar and meet behind it to do this. When they arrive behind the pillar, she greeted him by saying "What a fine young man", and he responded by greeting her with "What a fine young woman". They procreated and gave birth to a leech-child, which they put in a basket and let float away. Then they gave birth to a floating island, which likewise they did not recognize as one of their children.

Disappointed by their failures in procreation, they returned to Heaven and consulted the deities there. The deities explained that the cause of their difficulties was that the female had spoken first when they met to procreate. Izanagi and Izanami returned to their island and again met behind the heavenly pillar. When they met, he said, "What a fine young woman," and she said "What a fine young man". They mated and gave birth to the eight main islands of Japan and six minor islands. Then they gave birth to a variety of deities to inhabit those islands, including the sea deity, the deity of the sea-straits, and the deities of the rivers, winds, trees, and mountains. Last, Izanami gave birth to the fire deity, and her genitals were so burned that she died.

Donald L. Philippi, trans., 1969, Kojiki: Princeton, Princeton University Press, 655, and Joseph M. Campbell, 1962, The Masks of God: Oriental Mythology: New York, Viking Press, 561.

Questions:

When heaven and earth began, three deities came into being, The Spirit Master of the Center of Heaven, The August Wondrously Producing Spirit, and the Divine Wondrously Producing Ancestor. These three were invisible. The earth was young then, and land floated like oil, and from it reed shoots sprouted. From these reeds came two more deities. After them, five or six pairs of deities came into being, and the last of these were Izanagi and Izanami, whose names mean "The Male Who Invites" and "The Female who Invites".

The first five deities commanded Izanagi and Izanami to make and solidify the land of Japan, and they gave the young pair a jeweled spear. Standing on the Floating Bridge of Heaven, they dipped it in the ocean brine and stirred. They pulled out the spear, and the brine that dripped of it formed an island to which they descended. On this island they built a palace for their wedding and a great column to the heavens.

Izanami examined her body and found that one place had not grown, and she told this to Izanagi, who replied that his body was well-formed but that one place had grown to excess. He proposed that he place his excess in her place that was not complete and that in doing so they would make new land. They agreed to walk around the pillar and meet behind it to do this. When they arrive behind the pillar, she greeted him by saying "What a fine young man", and he responded by greeting her with "What a fine young woman". They procreated and gave birth to a leech-child, which they put in a basket and let float away. Then they gave birth to a floating island, which likewise they did not recognize as one of their children.

Disappointed by their failures in procreation, they returned to Heaven and consulted the deities there. The deities explained that the cause of their difficulties was that the female had spoken first when they met to procreate. Izanagi and Izanami returned to their island and again met behind the heavenly pillar. When they met, he said, "What a fine young woman," and she said "What a fine young man". They mated and gave birth to the eight main islands of Japan and six minor islands. Then they gave birth to a variety of deities to inhabit those islands, including the sea deity, the deity of the sea-straits, and the deities of the rivers, winds, trees, and mountains. Last, Izanami gave birth to the fire deity, and her genitals were so burned that she died.

Donald L. Philippi, trans., 1969, Kojiki: Princeton, Princeton University Press, 655, and Joseph M. Campbell, 1962, The Masks of God: Oriental Mythology: New York, Viking Press, 561.

Questions:

- Is there one god, goddess, or many? Name the characters.

- Who is responsible for creating humans?

- Is anyone asked to be silent in this story? Who?

- What happens to the female characters?

Livius: The Weidner Chronicle

The Weidner Chronicle is a religious ancient Babylonian text that acted as propaganda to illustrate the Mesopotamian rulers who insulted the god Marduk. In the text, Kubaba convinces a fisherman to offer his catch to Esagila (a temple dedicated to Marduk). In return, Marduk gives Kubaba her kingship.

In the reign of Puzur-Nirah, king of Akšak, the freshwater fishermen of Esagila were catching fish for the meal of the great lord Marduk; the officers of the king took away the fish.The fisherman was fishing when 7 (or 8) days had passed [...] in the house of Kubaba, the tavern-keeper [...] they brought to Esagila…Kubaba gave bread to the fisherman and gave water, she made him offer the fish to Esagila. Marduk, [a god] the king, the prince of the Apsû, favored her and said: "Let it be so!" He entrusted to Kubaba, the tavern-keeper, sovereignty over the whole world.

Weidner Chronicle, Livius. https://www.livius.org/sources/content/mesopotamian-chronicles-content/abc-19-weidner-chronicle/.

Questions:

In the reign of Puzur-Nirah, king of Akšak, the freshwater fishermen of Esagila were catching fish for the meal of the great lord Marduk; the officers of the king took away the fish.The fisherman was fishing when 7 (or 8) days had passed [...] in the house of Kubaba, the tavern-keeper [...] they brought to Esagila…Kubaba gave bread to the fisherman and gave water, she made him offer the fish to Esagila. Marduk, [a god] the king, the prince of the Apsû, favored her and said: "Let it be so!" He entrusted to Kubaba, the tavern-keeper, sovereignty over the whole world.

Weidner Chronicle, Livius. https://www.livius.org/sources/content/mesopotamian-chronicles-content/abc-19-weidner-chronicle/.

Questions:

- Isolate the fact from the fiction and discuss why myth and exaggeration may have been used to secure Kubaba’s power.

Remedial Herstory Editors. "2. TO 15,000 MOTHER EARTH AND GREAT GODDESSES?" The Remedial Herstory Project. November 1, 2022. www.remedialherstory.com.

Consulting Team |

Editors |

|

Kelsie Brook Eckert, Project Director

Coordinator of Social Studies Education at Plymouth State University Dr. Nancy Locklin-Sofer, Consultant Professor of History at Maryville College. Chloe Gardner, Consultant PhD Candidate in Religious Studies at Edinburgh University Dr. Whitney Howarth, Consultant Former Professor of History at Plymouth State University Jacqui Nelson, Consultant Teaching Lecturer of Military History at Plymouth State University Maria Concepcion Marquez Sandoval PhD Candidate in History at Arizona University |

Ron Kaiser

Humanities Teacher, Moultonborough Academy ReviewersAncient:

Dr. Kristin Heineman Professor of History at Colorado State University Dr. Bonnie Rock-McCutcheon Professor of History at Wilson College Sarah Stone PhD Candidate in Religious Studies at Edinburgh University Medieval: Dr. Katherine Koh Professor of History at La Sierra University Dr. Jonathan Couser Professor of History at Plymouth State University Dr. Shahla Haeri Professor of History at Boston University Lauren Cole PhD Candidate in History at Northwestern University Modern: Dr. Jack Gronau Professor of History at Northeastern University Dr. Barbara Tischler Supervisor for Hunter College Dr. Pamela Scully Professor of Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies and African Studies at Emory University |

|

According to the myth of matriarchal prehistory, men and women lived together peacefully before recorded history. Society was centered around women, with their mysterious life-giving powers, and they were honored as incarnations and priestesses of the Great Goddess. Then a transformation occurred, and men thereafter dominated society.

|

Lucy is a 3.2-million-year-old skeleton who has become the spokeswoman for human evolution. She is perhaps the best known and most studied fossil hominid of the twentieth century, the benchmark by which other discoveries of human ancestors are judged.”–From Lucy’s Legacy

|

The Chalice and the Blade tells a new story of our cultural origins. It shows that warfare and the war of the sexes are neither divinely nor biologically ordained. It provides verification that a better future is possible—and is in fact firmly rooted in the haunting dramas of what happened in our past.

|

|

From the beginning of recorded history, goddesses reigned alongside their male counterparts as figures of inspiration and awe. Drawing on anthropology, folklore, literature, and psychology, Monaghan’s vibrant and accessible encyclopedia covers female deities from Africa, the eastern Mediterranean, Asia and Oceania, Europe, and the Americas, as well as every major religious tradition

An inspiring exploration of the goddesses of the West African spiritual traditions and their role in shaping Yoruba (Ifa), Santeria, Haitian vodoun, and New Orleans voodoo.

From the cave painting of southern France to ancient Irish tombs, from shamanic rituals to Arthurian legends, the divine feminine plays an essential role in understanding where we have come from and where we are going. Comparative examples from other native cultures, and quotes from spiritual leaders around the world, set European religions in context with other indigenous cultures.

|

In these stories a mysterious and invisible realm of gods and spirits exists alongside and sometimes crosses over into our own human world; fierce women warriors battle with kings and heroes, and even the rules of time and space can be suspended. Captured in vivid prose these shadowy figures - gods, goddesses, and heroes - come to life for the modern listener.

Aztec Women and Goddesses explores the various stages of the Mexica woman’s life. Miriam López analyzes the mythology, the archaeological discoveries, and the codices and sixteenth-century chronicles with perfect ease as she describes the conduct expected of women and the possibilities for their lives according to Mexica norms and ideals.

|

Campbell traces the evolution of the feminine divine from one Great Goddess to many, from Neolithic Old Europe to the Renaissance. He sheds new light on classical motifs and reveals how the feminine divine symbolizes the archetypal energies of transformation, initiation, and inspiration.

Collectively, the essays consider the role of the festival's contextual specificity and continental ubiquity as a central component for understanding South Asian religious life, as well as how it shapes and is shaped by political patronage, economic development, and social status.

|

PREHISTORY (3,300,000-3000 BC)

They live in caves and huddle around fires, but they are fully human, though they belong to our most ancient history. Risa the Arbiter has now spent years in her role and is known and respected throughout the area. Her children are half-grown and exhibiting traits of independence, both of thought and action. Her tribe has grown along with her and now needs more than one Arbiter can provide alone. Risa struggles with how best to organize her duties and establishes acolytes in each village to screen petitioners.

Goddesses

|

Last in a centuries-old lineage of healing women, Dora Idesová was raised by her aunt Surmena in the White Carpathians. Resistant to superstition, Dora grew up hearing stories of the “goddesses” who were said to conjure love and curses and, through divine connection, cure the spirit and the body. Now an academic, Dora is researching the tales that for generations spellbound the hillside where she grew up. As the mysteries become truths, they reveal a stunning discovery that reaches back from the witch trials of the seventeenth century through Nazi-occupied Germany. Embarking on an emotional journey, Dora is about to find out how deeply and fatefully she is entwined with secret tradition.

|

To save her mother, Xingyin embarks on a perilous quest, confronting legendary creatures and vicious enemies across the earth and skies. When treachery looms and forbidden magic threatens the kingdom, however, she must challenge the ruthless Celestial Emperor for her dream - striking a dangerous bargain in which she is torn between losing all she loves or plunging the realm into chaos.

|

When the sea god Poseidon assaults Medusa in Athene’s temple, the goddess is enraged. Furious by the violation of her sacred space, Athene takes revenge—on the young woman. Punished for Poseidon’s actions, Medusa is forever transformed. Writhing snakes replace her hair, and her gaze will turn any living creature to stone. Cursed with the power to destroy all she loves with one look; Medusa condemns herself to a life of solitude. Until Perseus embarks upon a fateful quest to fetch the head of a Gorgon . . .

|

How to teach with Films:

Remember, teachers want the student to be the historian. What do historians do when they watch films?

- Before they watch, ask students to research the director and producers. These are the source of the information. How will their background and experience likely bias this film?

- Also, ask students to consider the context the film was created in. The film may be about history, but it was made recently. What was going on the year the film was made that could bias the film? In particular, how do you think the gains of feminism will impact the portrayal of the female characters?

- As they watch, ask students to research the historical accuracy of the film. What do online sources say about what the film gets right or wrong?

- Afterward, ask students to describe how the female characters were portrayed and what lessons they got from the film.

- Then, ask students to evaluate this film as a learning tool. Was it helpful to better understand this topic? Did the historical inaccuracies make it unhelpful? Make it clear any informed opinion is valid.

Bibliography

Diamond, Jared. “The Worst Mistake in Human History.” Discover Magazine, 1987. http://public.gettysburg.edu/~dperry/Class%20Readings%20Scanned%20Documents/Intro/

Eller, Cynthia, Gentlemen and Amazons: The Myth of Matriarchal Prehistory, 1861–1900 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 201).

Gruss, Laura Tobias, and Daniel Schmitt. “The evolution of the human pelvis: changing adaptations to bipedalism, obstetrics and thermoregulation.” Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences vol. 370,1663 (2015): 20140063. doi:10.1098/rstb.2014.0063

Landau, Elizabeth. "How Much Did Grandmothers Influence Human Evolution? Scientists debate the evolutionary benefits of menopause." Smithsonian Magazine. January 4, 2021. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/how-much-did-grandmothers-influence-human-evolution-180976665/.

Pollard, Elizabeth and Clifford Rosenberg, Ed. World Together Worlds Apart: A Companion Reader, 2nd Edition, Volume 1. New York: Norton & Company, Inc, 2016.

Schrein, Caitlin. "Lucy: A marvelous specimen." Nature Education Knowledge 6(7):2, 2015. https://www.nature.com/scitable/knowledge/library/lucy-a-marvelous-specimen-135716086/.

Strayer, R. and Nelson, E., Ways Of The World. 3rd ed. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2016.

Swaminathan, Nikhil. "Naia—the 13,000-Year-Old Native American." Archaeology. January/February 2015. https://www.archaeology.org/issues/161-1501/features/2793-mexico-cave-clovis-dna-naia.

Eller, Cynthia, Gentlemen and Amazons: The Myth of Matriarchal Prehistory, 1861–1900 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 201).

Gruss, Laura Tobias, and Daniel Schmitt. “The evolution of the human pelvis: changing adaptations to bipedalism, obstetrics and thermoregulation.” Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences vol. 370,1663 (2015): 20140063. doi:10.1098/rstb.2014.0063

Landau, Elizabeth. "How Much Did Grandmothers Influence Human Evolution? Scientists debate the evolutionary benefits of menopause." Smithsonian Magazine. January 4, 2021. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/how-much-did-grandmothers-influence-human-evolution-180976665/.

Pollard, Elizabeth and Clifford Rosenberg, Ed. World Together Worlds Apart: A Companion Reader, 2nd Edition, Volume 1. New York: Norton & Company, Inc, 2016.

Schrein, Caitlin. "Lucy: A marvelous specimen." Nature Education Knowledge 6(7):2, 2015. https://www.nature.com/scitable/knowledge/library/lucy-a-marvelous-specimen-135716086/.

Strayer, R. and Nelson, E., Ways Of The World. 3rd ed. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2016.

Swaminathan, Nikhil. "Naia—the 13,000-Year-Old Native American." Archaeology. January/February 2015. https://www.archaeology.org/issues/161-1501/features/2793-mexico-cave-clovis-dna-naia.