15. 1200-1400 Pastoral and Mongol Women

|

Despite the great Chinggis Khan being the focus of past historians of the Mongol Empires between 1200-1400, women played a vital role in the empire’s success. Daughters and Wives of the Khan governed the largest swath of land in world history. Wherever women were, their lives were impacted by the Mongol conquests.

Trigger Warning: for rape and sexual assault. |

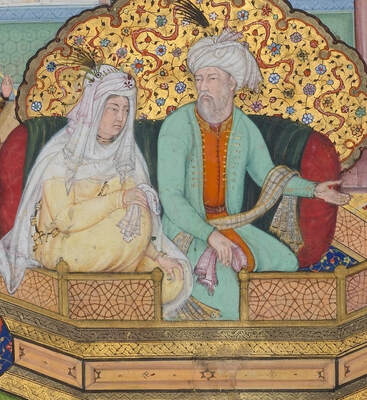

Börte and Ghengis Khan, Wikimedia Commons

Börte and Ghengis Khan, Wikimedia Commons

It is a bit mythical to suggest that with the arrival of agriculture, pastoralists just disappeared. No. In fact they lived and thrived away from the river valleys and co-existed alongside agriculture societies for millennia– even today. In the early middle ages, trade thrived throughout the booming Islamic and Chinese golden ages. Trade flourished not only on the old Silk Roads, but along sea roads between Africa and India made possible by monsoons. Across the Sahara desert, vast caravans of 5,000 camels and hundreds of people would bring goods to West Africa and back. It is these trade networks that brought the violent arrival of the Mongols– pastoral peoples who again and again defeated their enemies on land.

Where were women in this history? Everywhere. Never before the rise of the Mongol Empire or since have individual women held so much power over land and people. Chinggis Khan believed that if women could keep a home in order, they could keep a territory in order, so he gave the women closest to him the power to govern the majority of conquered territories.

Pastoral Women

Pastoral women often held a higher status compared to their settled peers. They had fewer restrictions on their role in public life and were involved in productive as well as reproductive labor. Mongol women frequently acted as political advisors. Misogyny was absolutely present, but pastoral communities’ religious sermons showed some individual focus on women’s spiritual needs, as well as some authentic depictions of the complexity in women’s lives. The presence of such ideas and understanding in a religious context is significant, given the long history of preferential treatment toward men.

The pastoral roles of women can be seen most explicitly in the Mongol Empire (1206-1368), an initially small pastoral empire from the steppes of Mongolia. This empire was founded by Chinggis Khan, born Teujin, who united the feuding and volatile Mongol clans with his charisma and reliance on friends over kin. Khan was raised by his resourceful mother, Hoelun, when their family was forced into exile. They reduced their reliance on pastoralism and ascribed to a hunter-gatherer like life. This was an enormous drop in social standing because they were poor. Before and during the unification, the Mongols herded horses for their prolific cavalry, sheep, goats, yaks, and more. When a European visitor to Mongolia described Mongol women. He wrote, “Girls and women ride in Gallup as skillfully as men. We even saw them carrying quivers and bows, And the women can ride horses for as long as the man; they have shorter stirrups, handle horses very well, and mind all the property. [Mongol] Women make everything: skin clothes, shoes, leggings, and everything made of leather. They drive carts and repair them, they load camels, and our quick and vigorous in all their tasks. They all wear trousers, and some of them shoot just like men.”

Börte was the first and favored wife of Khan. She and Temujin were betrothed at a young age and married at 17. At some point she was captured by a rival clan and he decided to rescue her. This decision may have launched him on his path toward conquering the world. Little is known about her life, but she and Chinggis Khan had nine children, whose bloodline would help the expanding empire.

Mongol women owned property, served in religious roles, rode horseback as the men did, at times fought in battle, and served as regents. They made camps and transport supplies for the army. Raising children was the responsibility of both parents, and marriages were arranged by both families. However, men could practice polygamy, though the first wife was given special status, and thus she and her children would inherit his property. Most widows did remarry, usually to a male relative of their husbands to keep wealth in the family.

In ancient nomadic societies, some scholars suggested that wealthy men with multiple wives treated them equally. However, if that fantasy was every possible, this was certainly not the case in terms of status among the Mongol wives. Even though each wife had her own dwelling, servants, income, and received attention from the husband, there was a clear hierarchy. The senior wife, often the first one married, held the most importance and controlled the largest and wealthiest camp. The arrangement of wifely dwellings within each camp followed a strict hierarchy, with the managing wife at the westernmost position and the most junior wife at the eastern end.

Children lived with their respective mothers, and older children had their own tents behind her. Servants had smaller quarters behind the family they served. Concubines were positioned behind the wives but in front of the guards and officials. When multiple camp-managing wives were together, the camps were arranged by the status of the mistresses. Despite the apparent gender roles, nomadic men were able to specialize in warfare because nomadic women efficiently managed the camps.

It would be a big mistake to assume that because women had more freedoms that they were equal or even protected members of society. Some historians argue that the nomadic stress on bride-wealth degraded women to chattel, and they were effectively purchased by husbands like property. Mongol women both before and after the unification of the tribes were often subject to rape and kidnapping during times of war.

Where were women in this history? Everywhere. Never before the rise of the Mongol Empire or since have individual women held so much power over land and people. Chinggis Khan believed that if women could keep a home in order, they could keep a territory in order, so he gave the women closest to him the power to govern the majority of conquered territories.

Pastoral Women

Pastoral women often held a higher status compared to their settled peers. They had fewer restrictions on their role in public life and were involved in productive as well as reproductive labor. Mongol women frequently acted as political advisors. Misogyny was absolutely present, but pastoral communities’ religious sermons showed some individual focus on women’s spiritual needs, as well as some authentic depictions of the complexity in women’s lives. The presence of such ideas and understanding in a religious context is significant, given the long history of preferential treatment toward men.

The pastoral roles of women can be seen most explicitly in the Mongol Empire (1206-1368), an initially small pastoral empire from the steppes of Mongolia. This empire was founded by Chinggis Khan, born Teujin, who united the feuding and volatile Mongol clans with his charisma and reliance on friends over kin. Khan was raised by his resourceful mother, Hoelun, when their family was forced into exile. They reduced their reliance on pastoralism and ascribed to a hunter-gatherer like life. This was an enormous drop in social standing because they were poor. Before and during the unification, the Mongols herded horses for their prolific cavalry, sheep, goats, yaks, and more. When a European visitor to Mongolia described Mongol women. He wrote, “Girls and women ride in Gallup as skillfully as men. We even saw them carrying quivers and bows, And the women can ride horses for as long as the man; they have shorter stirrups, handle horses very well, and mind all the property. [Mongol] Women make everything: skin clothes, shoes, leggings, and everything made of leather. They drive carts and repair them, they load camels, and our quick and vigorous in all their tasks. They all wear trousers, and some of them shoot just like men.”

Börte was the first and favored wife of Khan. She and Temujin were betrothed at a young age and married at 17. At some point she was captured by a rival clan and he decided to rescue her. This decision may have launched him on his path toward conquering the world. Little is known about her life, but she and Chinggis Khan had nine children, whose bloodline would help the expanding empire.

Mongol women owned property, served in religious roles, rode horseback as the men did, at times fought in battle, and served as regents. They made camps and transport supplies for the army. Raising children was the responsibility of both parents, and marriages were arranged by both families. However, men could practice polygamy, though the first wife was given special status, and thus she and her children would inherit his property. Most widows did remarry, usually to a male relative of their husbands to keep wealth in the family.

In ancient nomadic societies, some scholars suggested that wealthy men with multiple wives treated them equally. However, if that fantasy was every possible, this was certainly not the case in terms of status among the Mongol wives. Even though each wife had her own dwelling, servants, income, and received attention from the husband, there was a clear hierarchy. The senior wife, often the first one married, held the most importance and controlled the largest and wealthiest camp. The arrangement of wifely dwellings within each camp followed a strict hierarchy, with the managing wife at the westernmost position and the most junior wife at the eastern end.

Children lived with their respective mothers, and older children had their own tents behind her. Servants had smaller quarters behind the family they served. Concubines were positioned behind the wives but in front of the guards and officials. When multiple camp-managing wives were together, the camps were arranged by the status of the mistresses. Despite the apparent gender roles, nomadic men were able to specialize in warfare because nomadic women efficiently managed the camps.

It would be a big mistake to assume that because women had more freedoms that they were equal or even protected members of society. Some historians argue that the nomadic stress on bride-wealth degraded women to chattel, and they were effectively purchased by husbands like property. Mongol women both before and after the unification of the tribes were often subject to rape and kidnapping during times of war.

Song China

By comparison, the Chinese under the Song Dynasty were in a “Golden Age” for men… and a horrifying age for women.

The Song Dynasty reunified China and ruled from the late 900s into the 1300s. The decreasing influence of steppe nomads whose women had less restricted lives, and the return to fundamentalist Confucianism led to the Song Chinese keeping women separate in almost every domain in life. They emphasized women’s weakness, delicacy, and sexuality. Oh, Song, why’d you have to do us wrong?

The best example of increasing restrictions for women was a new practice of foot binding. Foot binding involved breaking and strapping a young girl's feet to a mold so that her feet would remain perpetually small even into adulthood. Foot binding was commonly accepted among elite families and later became widespread in China. It served to distinguish Chinese women from barbarians and peasants. It reinforced female frailty and emphasized their small size. Mothers imposed this painful procedure on their daughters in order to improve their marriage prospects and help their daughters compete with concubines for the attention of men. Foot binding became a rite of passage and was usually accompanied by beautiful gifted slippers.

The Song Dynasty did, however, witness some positive trends for women. Women continued to work in textiles spinning silk threads and weaving silk fabrics. In cities women had businesses in restaurants, as maids, and dressmakers. Property rights for women expanded when some officials began urging the education of women so they could teach their sons economics.

By comparison, the Chinese under the Song Dynasty were in a “Golden Age” for men… and a horrifying age for women.

The Song Dynasty reunified China and ruled from the late 900s into the 1300s. The decreasing influence of steppe nomads whose women had less restricted lives, and the return to fundamentalist Confucianism led to the Song Chinese keeping women separate in almost every domain in life. They emphasized women’s weakness, delicacy, and sexuality. Oh, Song, why’d you have to do us wrong?

The best example of increasing restrictions for women was a new practice of foot binding. Foot binding involved breaking and strapping a young girl's feet to a mold so that her feet would remain perpetually small even into adulthood. Foot binding was commonly accepted among elite families and later became widespread in China. It served to distinguish Chinese women from barbarians and peasants. It reinforced female frailty and emphasized their small size. Mothers imposed this painful procedure on their daughters in order to improve their marriage prospects and help their daughters compete with concubines for the attention of men. Foot binding became a rite of passage and was usually accompanied by beautiful gifted slippers.

The Song Dynasty did, however, witness some positive trends for women. Women continued to work in textiles spinning silk threads and weaving silk fabrics. In cities women had businesses in restaurants, as maids, and dressmakers. Property rights for women expanded when some officials began urging the education of women so they could teach their sons economics.

Korea

Further northeast, the expansion of Chinese influence in Korea led to the expansion of Confucianism there. This included Chinese models of family life and female behavior. Korean women, accustomed to raising their children in their parents' homes, were now expected to live with their husband’s families who owned them. Women lost their rights to inheritance, divorce, and men were no longer buried in the wife’s family plot. Elite women, especially wealthy widows, were heavily restricted… because women’s money needed to be controlled. But on the upside, the practice of plural marriages ended. By 1413 men had to determine which wife was primary in which was secondary, and the first wife had special privileges and status.

So by comparison, pastoral life with the Mongols might seem appealing… but the path to becoming Mongol involved conquest, and few fared well on the losing end of a battle with Mongols.

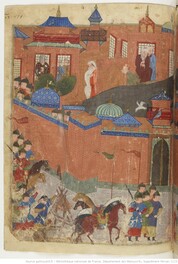

Mongol Army sacks Baghdad, Public Domain

Mongol Army sacks Baghdad, Public Domain

Rape Culture in War

The Mongol Empire grew rapidly out of Mongolia and into China and the rest of Eurasia. They sacked Baghdad, marking the end of the Abbasid Caliphate and destroying scrolls on science and theology. They proved vastly superior in war, especially on horseback compared to their Eurasian peers. They were better led, organized, and disciplined. As the Mongols marched on cities, they were known to be ruthless and unnecessarily violent. Women were on the front lines of conquests and helped manage the spoils of war. Conquered soldiers were scattered and redistributed into new units, so the army perpetually grew and created a sort of social revolution as tribe loyalty was replaced by loyalty to one's unit and commander. Commanders rode in the front and dressed in the same attire. Khan declared, “Whoever submits shall be spared, but those who resist, they shall be destroyed with their wives, children and dependents.” Thousands of enemy families who refused to surrender were executed in mass.

Conquered women were often enslaved. Because this episode involves war and conquest, this section is about to get pretty heavy, as women have always been subjected to rape and assault during war. So trigger warning for sexual assault. Pause now, or anytime, if you need to.

Chinggis Khan's own armies had undoubtedly inflicted such “punishments” on the women in the regions they conquered, but Kahn imposed orders against it. He wrote detailed laws about the treatment of women, including that even married women would not engage in sex until age sixteen, and they would need to be the one to initiate this with their husband. As his own mother and wife had been kidnapped and raped, he also enacted laws throughout the empire against rape, kidnapping, and enslavement, even though he later engaged in these horrors himself.

Unironically, Khan himself would often have women lined up in order ranked by their beauty. Only the most beautiful women were entered into his harem, while the apparently “less beautiful” were given to his sons and commanders. He used sexual violence as a deterrent for future enemies and to terrorize conquered women– prefering to sleep with the wives and daughters of the defeated enemy rulers. Today 16% of men can trace their lineage back to Khan– evidence of how many conquered women were subjected to rape at the hands of him and his descendents.

There are several stories of how he died. The most commonly accepted was that he died of injuries from a fall off a horse in 1227. One of the more questionable accounts, and the one I really hope is true, claims he was castrated and murdered while trying to rape a Tangut princess, a nomadic ethnic group that ruled the Xi-Xia Empire in northwestern China.

After he died, sexual terrorism remained a part of the empire he created and got worse.

Governance Under Khan’s Daughters

The Mongol Empire spread quickly and then fractured, stretching from China to Eastern Europe. Geography proved limiting for them. They tried to invade Japan but failed– seafaring was not their forte. They went for India, but the Himalayas were tall. They invaded Europe, but abandoned it as a backwater region with inadequate grass for their horses. While conquest was brutal, the empire itself was tolerant of various religions and established a sophisticated structure of governance for such a large empire.

In Chinggis Khan’s lifetime, he arranged the empire to have nine parts with his piece at the center surrounded by the conquered territories governed by his and Börte’s daughters. Then the less stable territories controlled by his sons. His vision was that men went to war, women ruled.

He executed this vision in the way he and Börte arranged the marriages of their daughters. His daughters with Börte inherited a Khan-like title which translates to "Princess Who Runs the State.” Their husbands, if they were mentioned in legal documents, were given the title gurugen, or son-in-law, and sent to war with the Mongol armies.

The daughters of Chinggis Khan played pivotal roles in his diplomatic and military endeavors. They strategically married leaders of influential tribes and nations neighboring the Mongols, such as the Ongud, Uyghurs, and Oirats. By doing so, they became diplomatic safeguards in various directions, solidifying alliances for Chinggis Khan.

Khan and Börte’s daughter, Alakhai Bekhi for example, was set up in a political marriage to secure the region south of Mongolia called the Gobi Desert. At some point the people revolted against their Mongol rulers. Her husband was killed, but she escaped back to the Mongol army. She married her step-son and regained stable control of the region.

Another daughter Checheyikhen was sent to govern the Oirat people who lived near Kazakhstan today. Collectively, Börte’s daughters took control of the Silk Route and actively contributed to their father's campaigns in China and Persia. Mongol women showcased their administrative skills in managing territories and demonstrated their combat prowess alongside men during foreign conquests.

However, after Chinggis Khan's death in 1227, his son Ögedei rejected his father’s preference for his daughters in governance. Ögedei tried to consolidate his power by killing female relatives. In 1237, after the death of his sister, he ordered the mass rape of four thousand Oirat girls to subjugate the Oirat people under his rule. How many women were raped is likely an exaggeration, but the The women who survived were left on the field to be doled others out to be sex slaves throughout his occupied lands and many others into his own personal harem. He used this monstrous act to not only seize his sibling’s lands, but picked off the lands of his other siblings and his father’s other wives.

There are also allegations of Ögedei orchestrating the assassination of Chinggis Khan's favorite daughter, Altalun, who ruled over the Uyghur territory. These actions marked a departure from Chinggis Khan's legacy and leadership style.

The Mongol Empire grew rapidly out of Mongolia and into China and the rest of Eurasia. They sacked Baghdad, marking the end of the Abbasid Caliphate and destroying scrolls on science and theology. They proved vastly superior in war, especially on horseback compared to their Eurasian peers. They were better led, organized, and disciplined. As the Mongols marched on cities, they were known to be ruthless and unnecessarily violent. Women were on the front lines of conquests and helped manage the spoils of war. Conquered soldiers were scattered and redistributed into new units, so the army perpetually grew and created a sort of social revolution as tribe loyalty was replaced by loyalty to one's unit and commander. Commanders rode in the front and dressed in the same attire. Khan declared, “Whoever submits shall be spared, but those who resist, they shall be destroyed with their wives, children and dependents.” Thousands of enemy families who refused to surrender were executed in mass.

Conquered women were often enslaved. Because this episode involves war and conquest, this section is about to get pretty heavy, as women have always been subjected to rape and assault during war. So trigger warning for sexual assault. Pause now, or anytime, if you need to.

Chinggis Khan's own armies had undoubtedly inflicted such “punishments” on the women in the regions they conquered, but Kahn imposed orders against it. He wrote detailed laws about the treatment of women, including that even married women would not engage in sex until age sixteen, and they would need to be the one to initiate this with their husband. As his own mother and wife had been kidnapped and raped, he also enacted laws throughout the empire against rape, kidnapping, and enslavement, even though he later engaged in these horrors himself.

Unironically, Khan himself would often have women lined up in order ranked by their beauty. Only the most beautiful women were entered into his harem, while the apparently “less beautiful” were given to his sons and commanders. He used sexual violence as a deterrent for future enemies and to terrorize conquered women– prefering to sleep with the wives and daughters of the defeated enemy rulers. Today 16% of men can trace their lineage back to Khan– evidence of how many conquered women were subjected to rape at the hands of him and his descendents.

There are several stories of how he died. The most commonly accepted was that he died of injuries from a fall off a horse in 1227. One of the more questionable accounts, and the one I really hope is true, claims he was castrated and murdered while trying to rape a Tangut princess, a nomadic ethnic group that ruled the Xi-Xia Empire in northwestern China.

After he died, sexual terrorism remained a part of the empire he created and got worse.

Governance Under Khan’s Daughters

The Mongol Empire spread quickly and then fractured, stretching from China to Eastern Europe. Geography proved limiting for them. They tried to invade Japan but failed– seafaring was not their forte. They went for India, but the Himalayas were tall. They invaded Europe, but abandoned it as a backwater region with inadequate grass for their horses. While conquest was brutal, the empire itself was tolerant of various religions and established a sophisticated structure of governance for such a large empire.

In Chinggis Khan’s lifetime, he arranged the empire to have nine parts with his piece at the center surrounded by the conquered territories governed by his and Börte’s daughters. Then the less stable territories controlled by his sons. His vision was that men went to war, women ruled.

He executed this vision in the way he and Börte arranged the marriages of their daughters. His daughters with Börte inherited a Khan-like title which translates to "Princess Who Runs the State.” Their husbands, if they were mentioned in legal documents, were given the title gurugen, or son-in-law, and sent to war with the Mongol armies.

The daughters of Chinggis Khan played pivotal roles in his diplomatic and military endeavors. They strategically married leaders of influential tribes and nations neighboring the Mongols, such as the Ongud, Uyghurs, and Oirats. By doing so, they became diplomatic safeguards in various directions, solidifying alliances for Chinggis Khan.

Khan and Börte’s daughter, Alakhai Bekhi for example, was set up in a political marriage to secure the region south of Mongolia called the Gobi Desert. At some point the people revolted against their Mongol rulers. Her husband was killed, but she escaped back to the Mongol army. She married her step-son and regained stable control of the region.

Another daughter Checheyikhen was sent to govern the Oirat people who lived near Kazakhstan today. Collectively, Börte’s daughters took control of the Silk Route and actively contributed to their father's campaigns in China and Persia. Mongol women showcased their administrative skills in managing territories and demonstrated their combat prowess alongside men during foreign conquests.

However, after Chinggis Khan's death in 1227, his son Ögedei rejected his father’s preference for his daughters in governance. Ögedei tried to consolidate his power by killing female relatives. In 1237, after the death of his sister, he ordered the mass rape of four thousand Oirat girls to subjugate the Oirat people under his rule. How many women were raped is likely an exaggeration, but the The women who survived were left on the field to be doled others out to be sex slaves throughout his occupied lands and many others into his own personal harem. He used this monstrous act to not only seize his sibling’s lands, but picked off the lands of his other siblings and his father’s other wives.

There are also allegations of Ögedei orchestrating the assassination of Chinggis Khan's favorite daughter, Altalun, who ruled over the Uyghur territory. These actions marked a departure from Chinggis Khan's legacy and leadership style.

Borte, Wikimedia Commons

Borte, Wikimedia Commons

Women Successors of Empire

Women shone most in the aftermath of Chinggis Khan’s death. Khan’s eldest sons were at odds jockeying for control of the empire. Because of an established military culture where men fought and women governed, the daughters of conquered kingdoms who had been married off to Khan’s descendants were poised to undo the empire. Known as “widow queens,” many conquered women assumed control when the governors of different parts of the empire died. Four queens in particular ripped apart Khan’s empire: Töregene, Oghul-Qaimish, and Sorqoqtani, were all conquered wives who had witnessed their fathers and brothers murdered by the Mongols and the deteriorated status of their people. Their trauma was not documented, but certainly their loyalty was not to their new husbands. Chabi, a relative of Borte, was also a contender for power in the post-Khan decades. They used their status within the new government to subvert and control the empire.

Women shone most in the aftermath of Chinggis Khan’s death. Khan’s eldest sons were at odds jockeying for control of the empire. Because of an established military culture where men fought and women governed, the daughters of conquered kingdoms who had been married off to Khan’s descendants were poised to undo the empire. Known as “widow queens,” many conquered women assumed control when the governors of different parts of the empire died. Four queens in particular ripped apart Khan’s empire: Töregene, Oghul-Qaimish, and Sorqoqtani, were all conquered wives who had witnessed their fathers and brothers murdered by the Mongols and the deteriorated status of their people. Their trauma was not documented, but certainly their loyalty was not to their new husbands. Chabi, a relative of Borte, was also a contender for power in the post-Khan decades. They used their status within the new government to subvert and control the empire.

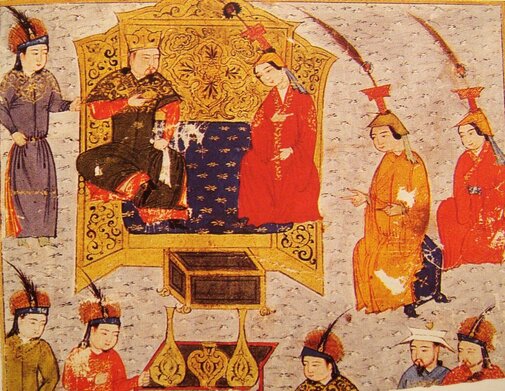

Sorkhogtani and Tolui, Public Domain

Sorkhogtani and Tolui, Public Domain

Töregene

Töregene selected Khan’s son, Ogedei, from a line up and married him. She ruled at his death as regent for their son. She replaced all of her husband's advisors and brought in her own, including a Persian woman named Fatima. Despite her help, when her eldest son, Guyuk, took power, he battled with his mother claiming Fatima was a witch. Fatima was raped and tortured for days, then all her orifices were covered and she was drowned in the river. Töregene died in unknown circumstances– murder?

But ladies will get their revenge.

Sorkhogtani

Across the empire, Sorkhogtani was the wife of Chinggis’s youngest son, Tolui. Sorkogtani was an Eastern Christian from steppe near Mongol territory. Tolui was a reckless drunk, and she was basically ruling in his name until he died of poisoning– wonder who was behind that? As Mongol society dictated, she became the head of household and inherited his property. Guyuk tried to marry her to expand his power, but she refused claiming “loyalty” to her deceased husband and a desire to properly raise her sons. This was significant, because Mongol women were expected to remarry. Her status as a single widow went against Mongol custom, but gave her power to try and maneuver politics to favor her sons.

She became regent for her sons in northern China. She insisted that her sons be well educated to properly run the empire. She hand-selected their senior wives. She encouraged those women to cooperate and work together to govern, and was less than successful. She also ensured that each learned the languages of the people they would rule, and encouraged religious tolerance. She even donated to both Christian churches and Muslim mosques and schools. During her time in northern China leading her own territory, she helped with opening trade, encouraged the exchange of ideas throughout the empire, and advised Ogodei and other leaders about the dangers of exploiting their conquered people, which often meant greater tolerance and security for the people under the Khans.

In a particularly fiery episode, she collaborated with her nephew, Batu, the leader of the Golden Horde, in a plot against Guyuk’s control. Following Guyuk's death from alcoholism, she and Batu orchestrated a strategic maneuvering of succession within the family to secure dominance for her sons. Her eldest son, Mongke, ultimately ascended as the next influential Khan. To solidify their control, she and Batu carried out brutal purges against opposing branches of the family, specifically the Ogedeyids and Chagatayids, ensuring they would never pose a threat again. Consequently, her family maintained control over the Great Khanate until its existence concluded in 1368.

Sorghaghtani fell ill and died in February or March 1252. At that point, her sons controlled most of Chinggis Khan's empire at its extent. As one of the most powerful people in the Mongol Empire she helped to ensure its longevity and transition into the future. She was one of those rare figures that was well regarded in a number of different historical sources, and her importance may be rivaled only by Chinggis Khan himself.

Töregene selected Khan’s son, Ogedei, from a line up and married him. She ruled at his death as regent for their son. She replaced all of her husband's advisors and brought in her own, including a Persian woman named Fatima. Despite her help, when her eldest son, Guyuk, took power, he battled with his mother claiming Fatima was a witch. Fatima was raped and tortured for days, then all her orifices were covered and she was drowned in the river. Töregene died in unknown circumstances– murder?

But ladies will get their revenge.

Sorkhogtani

Across the empire, Sorkhogtani was the wife of Chinggis’s youngest son, Tolui. Sorkogtani was an Eastern Christian from steppe near Mongol territory. Tolui was a reckless drunk, and she was basically ruling in his name until he died of poisoning– wonder who was behind that? As Mongol society dictated, she became the head of household and inherited his property. Guyuk tried to marry her to expand his power, but she refused claiming “loyalty” to her deceased husband and a desire to properly raise her sons. This was significant, because Mongol women were expected to remarry. Her status as a single widow went against Mongol custom, but gave her power to try and maneuver politics to favor her sons.

She became regent for her sons in northern China. She insisted that her sons be well educated to properly run the empire. She hand-selected their senior wives. She encouraged those women to cooperate and work together to govern, and was less than successful. She also ensured that each learned the languages of the people they would rule, and encouraged religious tolerance. She even donated to both Christian churches and Muslim mosques and schools. During her time in northern China leading her own territory, she helped with opening trade, encouraged the exchange of ideas throughout the empire, and advised Ogodei and other leaders about the dangers of exploiting their conquered people, which often meant greater tolerance and security for the people under the Khans.

In a particularly fiery episode, she collaborated with her nephew, Batu, the leader of the Golden Horde, in a plot against Guyuk’s control. Following Guyuk's death from alcoholism, she and Batu orchestrated a strategic maneuvering of succession within the family to secure dominance for her sons. Her eldest son, Mongke, ultimately ascended as the next influential Khan. To solidify their control, she and Batu carried out brutal purges against opposing branches of the family, specifically the Ogedeyids and Chagatayids, ensuring they would never pose a threat again. Consequently, her family maintained control over the Great Khanate until its existence concluded in 1368.

Sorghaghtani fell ill and died in February or March 1252. At that point, her sons controlled most of Chinggis Khan's empire at its extent. As one of the most powerful people in the Mongol Empire she helped to ensure its longevity and transition into the future. She was one of those rare figures that was well regarded in a number of different historical sources, and her importance may be rivaled only by Chinggis Khan himself.

Portrait of Chabi, Wikimedia Commons

Portrait of Chabi, Wikimedia Commons

Chabi

Chabi was the wife of Kublai Khan, Chinggis Khan’s grandson and ruler of conquered China. Unlike the other women, she was not a conquered wife, but an arranged one. Per custom, she was selected from within Borte’s family. She arranged the lifelong care of the Empress and royal women of the Song Dynasty once they were captured.

In China, Chabi mixed freely with men at social gatherings, rejected foot binding, and forced Khan into treating the Chinese better. She designed new hats with brims to shade Mongol soldiers' eyes, patronized Tibetan Buddhism, and was notorious frugal. Khan relied heavily on female advisors.

In China, intermarriages between Mongols and the Chinese were forbidden. The Mongols lived in “ger cities,” a type of yurt, outside major Chinese cities and maintained their lifestyle not imposing it on their Chinese subjects.

Khutulun

The Mongol empire declined slowly and the power and respect given to Mongol queens also declined. A strong example of this was Khutulun(1260 – 1306), a prominent Mongol noblewoman and the renowned daughter of Kaidu, a cousin to Kublai Khan. Among Kaidu's offspring, Khutulun was the favored one, sought after for advice and political support. Some accounts suggest that Kaidu attempted to designate her as his successor to the khanate before his death in 1301. However, her male relatives rejected this choice. Following Kaidu's demise, Khutulun safeguarded his tomb alongside her brother Orus. She faced challenges from other brothers, like Chapar and relative Duwa, who sought succession.

This is especially remarkable because of how formidable and strong Khutulun was reported to be. Both Marco Polo and Rashid al-Din Hamadani documented their encounters with her. She was actively involved in Mongol military expeditions in Central Asia. She was trained in archery, wrestling, and horsemanship from her early years. As she matured, her wrestling prowess became so remarkable that she defeated elite male warriors in traditional competitions. One suitor challenged her to a match and she so humiliated him that no marriage was arranged.

Japan

The Mongols under Khan and Chabi tried to invade Japan by sea, but failed. This allowed for continuity, stability, and the growth of the arts in Japanese culture.

Chabi was the wife of Kublai Khan, Chinggis Khan’s grandson and ruler of conquered China. Unlike the other women, she was not a conquered wife, but an arranged one. Per custom, she was selected from within Borte’s family. She arranged the lifelong care of the Empress and royal women of the Song Dynasty once they were captured.

In China, Chabi mixed freely with men at social gatherings, rejected foot binding, and forced Khan into treating the Chinese better. She designed new hats with brims to shade Mongol soldiers' eyes, patronized Tibetan Buddhism, and was notorious frugal. Khan relied heavily on female advisors.

In China, intermarriages between Mongols and the Chinese were forbidden. The Mongols lived in “ger cities,” a type of yurt, outside major Chinese cities and maintained their lifestyle not imposing it on their Chinese subjects.

Khutulun

The Mongol empire declined slowly and the power and respect given to Mongol queens also declined. A strong example of this was Khutulun(1260 – 1306), a prominent Mongol noblewoman and the renowned daughter of Kaidu, a cousin to Kublai Khan. Among Kaidu's offspring, Khutulun was the favored one, sought after for advice and political support. Some accounts suggest that Kaidu attempted to designate her as his successor to the khanate before his death in 1301. However, her male relatives rejected this choice. Following Kaidu's demise, Khutulun safeguarded his tomb alongside her brother Orus. She faced challenges from other brothers, like Chapar and relative Duwa, who sought succession.

This is especially remarkable because of how formidable and strong Khutulun was reported to be. Both Marco Polo and Rashid al-Din Hamadani documented their encounters with her. She was actively involved in Mongol military expeditions in Central Asia. She was trained in archery, wrestling, and horsemanship from her early years. As she matured, her wrestling prowess became so remarkable that she defeated elite male warriors in traditional competitions. One suitor challenged her to a match and she so humiliated him that no marriage was arranged.

Japan

The Mongols under Khan and Chabi tried to invade Japan by sea, but failed. This allowed for continuity, stability, and the growth of the arts in Japanese culture.

Delhi Sultanate

Safe from Mongol conquest on the other side of the himalayan mountains, in the 1200s Century, northern India saw the rise of the Delhi Sultanate. There Razia Sultana became the first female Muslim leader of the region. She began her political career under her father, Iltutmish, tending to the administrative needs of their people while he was away at war. He put his trust in her because he believed his sons were all too selfish and focused on having fun to properly manage the state affairs while he was gone, and even after his death. Thus, when he returned, he named her as his heir, telling his nobles that she was the most capable of his children.

The nobles didn’t quite buy it, however, and appointed her half-brother after their father’s death. In response, she successfully led a rebellion to claim power. It was not only an anomaly to have a woman as a political leader, but further, her rebellion was one based on public support. She galvanized the people and they would be the ones to drive her to the throne. Despite her meteoric rise, when she claimed the throne in 1236, many of her political allies and enemies alike still expected her to serve in a ceremonial role while they pulled the strings behind the scenes, but she refused to relinquish her power. She even began to create a new class of nobles from her supporters to temper their power.

Thus, she ran afoul of the aristocracy, who ultimately launched their own rebellion to depose her. She led an army out of Delhi to meet them, and after a few key victories, some of the rebels began to defect to her and the other leaders were caught and executed. From there, the nobles were forced to accept her authority, though she continued to face conflict throughout her reign including civil conflicts between Sunnis and Shias, as well as incursions by the Mongols. Still, despite these other threats, the nobles continued to be her greatest hurdle.

She increasingly broke from tradition to assert her authority and better connect with the people. She dressed as a man in public, and rode through the streets atop an elephant as the sultans of the past had. She regularly made connections and appearances among the people, rather than catering to the nobility. She even elevated formerly enslaved people to elite positions within her administration. Shy of four years after her reign had begun, enough of her nobles had joined forces to overthrow her and began unraveling the vision she had for Delhi. She would try once again to launch a rebellion, but failed, and was killed in the process.

Conclusion

Eventually the Mongols were expelled from China in a rebellion and declined elsewhere over time. Part of this decline was due to a backlash against female leadership and a rejection of Chinggis Khan’s reverence for female advisors and governance of conquered territories. Another part was because conquered women rulers worked to install non-Mongols in positions of power within government. Everywhere women survive rape and sexual terrorism, there is a resilient force working for revenge.

One of the Mongols' achievements in unifying trade across the vast network of Silk Roads also led to the mixing of peoples– and this helped spread the Black Death from central Asia westward. By some estimates 50-90% of various populations died.

A unified Mongolian Empire did not survive. The Mongol Empire remains the most influential world empire about which so little is known. Religions and cultures that existed before them remained throughout and in their wake. In its place, in China, the Middle East, and Europe, parts of Africa, would see a rebirth. But would women?

Little is known about the Mongol Empire because they kept their chronicles secret. The Secret History of the Mongols was a treasured document. At some point, an unknown chronicler tore out a section of it in order to hide the contributions of Mongol women. Only a tiny piece of that text recorded by Chinggis Khan in 1206 remains, “Let us reward our female offspring.”

If it weren’t for chroniclers from other nations and territories, including Marco Polo and others, the stories of these women may have been lost. Why the chronicler wanted to cover up their stories is unknown.

By the end of this era, so much remained in question. What legacy would Mongolians leave in their wake? How would the Eurasian world rebuild after the Mongols? What role would women play in that effort?

Safe from Mongol conquest on the other side of the himalayan mountains, in the 1200s Century, northern India saw the rise of the Delhi Sultanate. There Razia Sultana became the first female Muslim leader of the region. She began her political career under her father, Iltutmish, tending to the administrative needs of their people while he was away at war. He put his trust in her because he believed his sons were all too selfish and focused on having fun to properly manage the state affairs while he was gone, and even after his death. Thus, when he returned, he named her as his heir, telling his nobles that she was the most capable of his children.

The nobles didn’t quite buy it, however, and appointed her half-brother after their father’s death. In response, she successfully led a rebellion to claim power. It was not only an anomaly to have a woman as a political leader, but further, her rebellion was one based on public support. She galvanized the people and they would be the ones to drive her to the throne. Despite her meteoric rise, when she claimed the throne in 1236, many of her political allies and enemies alike still expected her to serve in a ceremonial role while they pulled the strings behind the scenes, but she refused to relinquish her power. She even began to create a new class of nobles from her supporters to temper their power.

Thus, she ran afoul of the aristocracy, who ultimately launched their own rebellion to depose her. She led an army out of Delhi to meet them, and after a few key victories, some of the rebels began to defect to her and the other leaders were caught and executed. From there, the nobles were forced to accept her authority, though she continued to face conflict throughout her reign including civil conflicts between Sunnis and Shias, as well as incursions by the Mongols. Still, despite these other threats, the nobles continued to be her greatest hurdle.

She increasingly broke from tradition to assert her authority and better connect with the people. She dressed as a man in public, and rode through the streets atop an elephant as the sultans of the past had. She regularly made connections and appearances among the people, rather than catering to the nobility. She even elevated formerly enslaved people to elite positions within her administration. Shy of four years after her reign had begun, enough of her nobles had joined forces to overthrow her and began unraveling the vision she had for Delhi. She would try once again to launch a rebellion, but failed, and was killed in the process.

Conclusion

Eventually the Mongols were expelled from China in a rebellion and declined elsewhere over time. Part of this decline was due to a backlash against female leadership and a rejection of Chinggis Khan’s reverence for female advisors and governance of conquered territories. Another part was because conquered women rulers worked to install non-Mongols in positions of power within government. Everywhere women survive rape and sexual terrorism, there is a resilient force working for revenge.

One of the Mongols' achievements in unifying trade across the vast network of Silk Roads also led to the mixing of peoples– and this helped spread the Black Death from central Asia westward. By some estimates 50-90% of various populations died.

A unified Mongolian Empire did not survive. The Mongol Empire remains the most influential world empire about which so little is known. Religions and cultures that existed before them remained throughout and in their wake. In its place, in China, the Middle East, and Europe, parts of Africa, would see a rebirth. But would women?

Little is known about the Mongol Empire because they kept their chronicles secret. The Secret History of the Mongols was a treasured document. At some point, an unknown chronicler tore out a section of it in order to hide the contributions of Mongol women. Only a tiny piece of that text recorded by Chinggis Khan in 1206 remains, “Let us reward our female offspring.”

If it weren’t for chroniclers from other nations and territories, including Marco Polo and others, the stories of these women may have been lost. Why the chronicler wanted to cover up their stories is unknown.

By the end of this era, so much remained in question. What legacy would Mongolians leave in their wake? How would the Eurasian world rebuild after the Mongols? What role would women play in that effort?

Draw your own conclusions

|

Learn how to teach with inquiry.

Many of these lesson plans were sponsored in part by the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources Eastern Region Program, coordinated by Waynesburg University, the History and Social Studies Education Faculty at Plymouth State University, and the Patrons of the Remedial Herstory Project. |

|

How did elite wives to Mongol conquerors resist?

Married to the men who slaughtered their people, women across the Mongol empire survived. How did they preserve their cultures and resist Mongol rule? Coming soon! What is Genghis Khan's legacy with women?

Respectful to his first wife, brutal to his conquered victims. How do remember this complex legacy? Coming soon! |

Lesson Plans from Other Organizations

- This website, Women in World History has primary source based lesson plans on women's history in a whole range of topics. Some are free while others have a cost.

- The Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media has produced recommendations for teaching women's history with primary sources and provided a collection of sources for world history. Check them out!

- The Stanford History Education Group has a number of lesson plans about women in World History.

Coming soon!

Remedial Herstory Editors. "15. 1200-1400 PASTORAL AND MONGOL WOMEN." The Remedial Herstory Project. November 1, 2022. www.remedialherstory.com.

AUTHOR: |

Kelsie Brook Eckert and Jacqui Nelson

|

Consulting Team |

Editors |

|

Kelsie Brook Eckert, Project Director

Coordinator of Social Studies Education at Plymouth State University Dr. Nancy Locklin-Sofer, Consultant Professor of History at Maryville College. Chloe Gardner, Consultant PhD Candidate in Religious Studies at Edinburgh University Dr. Whitney Howarth, Consultant Former Professor of History at Plymouth State University Jacqui Nelson, Consultant Teaching Lecturer of Military History at Plymouth State University Maria Concepcion Marquez Sandoval PhD Candidate in History at Arizona University |

Amy Flanders

Humanities Teacher at Moultonborough Academy ReviewersAncient:

Dr. Kristin Heineman Professor of History at Colorado State University Dr. Bonnie Rock-McCutcheon Professor of History at Wilson College Sarah Stone PhD Candidate in Religious Studies at Edinburgh University Dr. Anne Broadbridge Professor of History at the University of Massachusetts Medieval: Dr. Katherine Koh Professor of History at La Sierra University Dr. Jonathan Couser Professor of History at Plymouth State University Dr. Shahla Haeri Professor of History at Boston University Lauren Cole PhD Candidate in History at Northwestern University Modern: Dr. Barbara Tischler Supervisor for Hunter College Dr. Pamela Scully Professor of Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies and African Studies at Emory University |

|

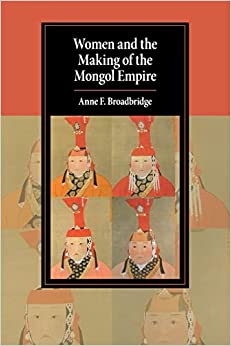

Examining the best-known women of Mongol society, such as Chinggis Khan's mother, Hö'elün, and senior wife, Börte, as well as those who were less famous but equally influential, including his daughters and his conquered wives, we see the systematic and essential participation of women in empire, politics and war.

An essay comparing the roles of Mongol and Chinese women in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.

|

|

|

Genghis Khan united a nation and created a vast empire for his heirs. But after 200 years of civil war, his empire has fallen into the dark ages. Mandukhai dreams of being a fierce warrior woman, but her dreams are shattered when she is forced to become the second wife to the Great Khan. Unebolod spent his life in the Great Khan's shadow, preparing for a day when he can seize control of the empire. But when he forms a dangerous alliance with Mandukhai, it swiftly transforms into a passion that could destroy them both. Daughter of the Yellow Dragon is the first book in a gripping, gritty historical fiction series based on the epic life of one of the most underrated women in history. The series draws you into a world of brutal Mongol steppe life, deadly political games, and supernatural beliefs.

During their battle with the King of Georgia, Hujaur and Soqatai are taken prisoner and subjected to mind-numbing humiliation, assault and raw brutality before they are turned over to the largest tribe of the western steppe, the Polovtsi. Using diplomacy and "bribes", Subotei wins passage from the Polotvsi who return the sisters; now near death. In the following weeks, the Polovtsi seek an alliance with the Rus to drive the barbarians from their steppe homelands; while the sisters recover and vow vengeance on those who brutalized them. For nine days in the month of May, a coalition force of Rus and Polovtsi pursue the Mongols east, culminating on the ninth day in one of the great battles of military history at the River Kalka. It is here Hujaur and Soqatai hope to satiate their hunger for vengeance and redeem themselves and their honor.

|

|

Bibliography

Broadbridge, Anne. Women and the Making of the Mongol Empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

"Chinggis Khan and his wife Börte in The Secret History of the Mongols," in World History Commons, https://worldhistorycommons.org/chinggis-khan-and-his-wife-borte-secret-history-mongols.

History Editors. “10 Things You May Not Know About Chinggis Khan.” History. https://www.history.com/news/10-things-you-may-not-know-about-Chinggis-khan#:~:text=The%20traditional%20narrative%20says%20he,himself%20on%20a%20Chinese%20princess.

Mayell, Hillary. “Chinggis Khan a Prolific Lover, DNA Data Implies.” National Geographic. February 14, 2003. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/mongolia-Chinggis-khan-dna.

Scharping, Nathaniel. “The Life of Chinggis Khan, the Ruthless Warlord Who Created the World’s Largest Empire: 800 years ago, a young man rose to power in Mongolia. The world would never be the same.” Discover. October 17, 2020. https://www.discovermagazine.com/planet-earth/the-life-of-Chinggis-khan-the-ruthless-warlord-who-created-the-worlds-largest.

Weatherford, Jack. The Secret History of the Mongol Queens: How the daughters of Chinggis Khan rescued his empire. New York: Broadway Paperbacks, 2010.

"Chinggis Khan and his wife Börte in The Secret History of the Mongols," in World History Commons, https://worldhistorycommons.org/chinggis-khan-and-his-wife-borte-secret-history-mongols.

History Editors. “10 Things You May Not Know About Chinggis Khan.” History. https://www.history.com/news/10-things-you-may-not-know-about-Chinggis-khan#:~:text=The%20traditional%20narrative%20says%20he,himself%20on%20a%20Chinese%20princess.

Mayell, Hillary. “Chinggis Khan a Prolific Lover, DNA Data Implies.” National Geographic. February 14, 2003. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/mongolia-Chinggis-khan-dna.

Scharping, Nathaniel. “The Life of Chinggis Khan, the Ruthless Warlord Who Created the World’s Largest Empire: 800 years ago, a young man rose to power in Mongolia. The world would never be the same.” Discover. October 17, 2020. https://www.discovermagazine.com/planet-earth/the-life-of-Chinggis-khan-the-ruthless-warlord-who-created-the-worlds-largest.

Weatherford, Jack. The Secret History of the Mongol Queens: How the daughters of Chinggis Khan rescued his empire. New York: Broadway Paperbacks, 2010.