8. Women and the west

|

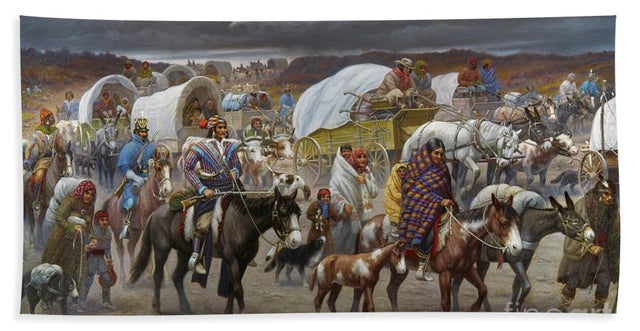

The west was a crossroads, and a place where we can see the intersection of so many different women. Mexican women, gold rush women, Chinese immigrants, American homesteaders, cowgirls, and Native Americans all staked claim in these territories. Their interactions created a diverse, tense, and fascinating culture that led to freedoms and restrictions for women.

|

Women on the U.S Frontier, National Park Services

Women on the U.S Frontier, National Park Services

As debates over slavery raged throughout the country, life on the western frontier was a whole different experience. Unfettered by traditional gender norms, diverse in culture and people, and full of the challenge of frontier life, women seemingly had more opportunities in the west to be what they couldn’t in the east. While all women in the 1800s had their struggles, life in the west had some unique dimensions that varied distinctly by race and class.

At the time of westward expansion there were few opportunities for women in the east. Some women were bound by traditional gender ideology which limited their options to marriage and domestic life, while poor women were making inroads at some of the nation’s first factories. New western lands acquired in the Louisiana Purchase, and later through war with Mexico, created an opportunity for poor and adventurous Americans to pursue the American Dream. Men often went in advance of their wives and families to establish a property and income. Women are commonly portrayed as having been dragged along on these adventures– but this characterization isn’t entirely accurate.

In some respects, the west was an equalizer. The women who made the journey were not marginalized in their own time, but their stories have been obscured. To uncover this rich history, we have to reconsider the types of work that women did–they did everything that was necessary to grow crops, raise animals, and bear and raise children in the isolation of the plains and prairies. Life was hard, and women had to be tough.

At the time of westward expansion there were few opportunities for women in the east. Some women were bound by traditional gender ideology which limited their options to marriage and domestic life, while poor women were making inroads at some of the nation’s first factories. New western lands acquired in the Louisiana Purchase, and later through war with Mexico, created an opportunity for poor and adventurous Americans to pursue the American Dream. Men often went in advance of their wives and families to establish a property and income. Women are commonly portrayed as having been dragged along on these adventures– but this characterization isn’t entirely accurate.

In some respects, the west was an equalizer. The women who made the journey were not marginalized in their own time, but their stories have been obscured. To uncover this rich history, we have to reconsider the types of work that women did–they did everything that was necessary to grow crops, raise animals, and bear and raise children in the isolation of the plains and prairies. Life was hard, and women had to be tough.

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

In the former Spanish colonies of newly independent Mexico, married women living in the American Southwest had certain legal advantages not afforded their European-American peers. Under English common law, women, when they married, became femmes covert (effectively dead in the eyes of the legal system) and thus unable to own property separately from their husbands. Spanish-Mexican women retained control of their land after marriage and held one-half interest in the community property they shared with their spouses. Historians have noted that intermarriage with Hispano women in the Mexican era provided foreigners with access to land and trade networks. While this made Spanish-Mexican women attractive marriage partners for white American men who moved into the region, the laws regarding land ownership that emerged in that context–and that remained after U.S. annexation–benefitted white women, too.

The West gave women special opportunities as authors and entertainers. Aspiring writers saw literary “material” in the stuff of their daily lives in frontier, rural,and urban western spaces. They shaped that material into letters, journals, sketches, essays, and stories for eastern magazines and presses—and received popular acclaim. Furthermore, women like Lola Montez were able to become fixtures of the western entertainment world–while earning a living for themselves.

The West gave women special opportunities as authors and entertainers. Aspiring writers saw literary “material” in the stuff of their daily lives in frontier, rural,and urban western spaces. They shaped that material into letters, journals, sketches, essays, and stories for eastern magazines and presses—and received popular acclaim. Furthermore, women like Lola Montez were able to become fixtures of the western entertainment world–while earning a living for themselves.

Juana Gertrudis Navarro Alsbury, The Alamo

Juana Gertrudis Navarro Alsbury, The Alamo

Texas Independence:

Many Americans settled in the region of Texas, a state within the Mexican nation. There they were subjected to Mexican laws which required their conversion to Catholicism and outlawed the institution of slavery. Many Americans came to the region despite those restrictions; but over time, the ratio of Americans to Mexicans became 10 to 1 in the sparsely populated region of Northern Mexico As Mexican leaders saw Texas slipping away from their grasp–particularly as many Americans in Texas were migrants from the American South who brought slaves with them and openly defied Mexican law ,revolution seemed inevitable.

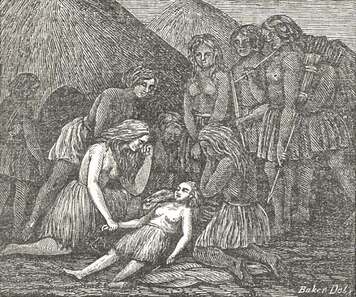

In 1835, war began. As Mexico attempted to regain control over the region, Texans refused to submit to the Mexican military. After a small battle, the Texans took control of the Alamo where they settled in for the real fight. Women were among those inside the fort. Susanna Dickinson was one of them, along with her infant daughter. Her husband was a captain in charge of artillery at the Alamo. It was a decisive Mexican victory in which only about 14 Texans survived out of almost 200. Dickinson was one of the survivors. She hid in a dark room inside the mission during the assault, and later told her story, “A few days before the final assault three Texans entered the fort during the night and inspired us with sanguine hopes of speedy relief, and thus animated the men to contend to the last. A Mexican woman deserted us one night, and going over to the enemy informed them of our very inferior numbers, which Col. Travis said made them confident of success and emboldened them to make the final assault, which they did at early dawn on the morning.”

Two sisters, Juana Gertrudis Navarro Alsbury and Maria Gertrudis Navarro, were also at the Alamo and survived. They recalled the deaths of many people during the month-long assault and said that defenders were shot right in front of them in the final hours of the battle.

Many Americans settled in the region of Texas, a state within the Mexican nation. There they were subjected to Mexican laws which required their conversion to Catholicism and outlawed the institution of slavery. Many Americans came to the region despite those restrictions; but over time, the ratio of Americans to Mexicans became 10 to 1 in the sparsely populated region of Northern Mexico As Mexican leaders saw Texas slipping away from their grasp–particularly as many Americans in Texas were migrants from the American South who brought slaves with them and openly defied Mexican law ,revolution seemed inevitable.

In 1835, war began. As Mexico attempted to regain control over the region, Texans refused to submit to the Mexican military. After a small battle, the Texans took control of the Alamo where they settled in for the real fight. Women were among those inside the fort. Susanna Dickinson was one of them, along with her infant daughter. Her husband was a captain in charge of artillery at the Alamo. It was a decisive Mexican victory in which only about 14 Texans survived out of almost 200. Dickinson was one of the survivors. She hid in a dark room inside the mission during the assault, and later told her story, “A few days before the final assault three Texans entered the fort during the night and inspired us with sanguine hopes of speedy relief, and thus animated the men to contend to the last. A Mexican woman deserted us one night, and going over to the enemy informed them of our very inferior numbers, which Col. Travis said made them confident of success and emboldened them to make the final assault, which they did at early dawn on the morning.”

Two sisters, Juana Gertrudis Navarro Alsbury and Maria Gertrudis Navarro, were also at the Alamo and survived. They recalled the deaths of many people during the month-long assault and said that defenders were shot right in front of them in the final hours of the battle.

Santa Anna, Britannica

Santa Anna, Britannica

Following the Alamo battle, Dickinson and the other surviving women were brought before Mexican General Santa Anna. He allowed her to be released on the condition that she delivered a letter to Sam Houston, stating that the treatment given to the rebels at the Alamo would be extended to the rest of the country.

In return for her release, she was provided with a horse and two enslaved people. They were forced to travel to Gonzalez. She eventually joined the large-scale migration known as the Runaway Scrape. As a widow, Susanna had limited means to support herself and, as a result, remarried multiple times. Finally, in 1857, she settled in Austin with her fifth husband, Joseph William Hannig, where the family thrived.

The struggle for Texan independence ramped up after the Alamo, with soldiers joining the cause. Santa Anna began an inhumane policy of executing Texas prisoners and burning their bodies rather than burying them which was Christian custom. Peggy McCormick owned land on the San Jacinto river where the final battle of Texas Independence occurred. As the battle raged, Peggy and her sons fled their property and returned to find their corn crop and more than 230 livestock had been taken by both the Mexican and Texan armies. Moreover, the bodies of numerous Mexican soldiers were left to rot. Distraught by the state of her home, Peggy confronted Houston at his camp, urging him to remove the rotting corpses. He refused and encouraged her to appreciate the historic significance of her land. She was unimpressed and responded defiantly, “To the devil with your glorious history! Take off your stinking Mexicans."

In return for her release, she was provided with a horse and two enslaved people. They were forced to travel to Gonzalez. She eventually joined the large-scale migration known as the Runaway Scrape. As a widow, Susanna had limited means to support herself and, as a result, remarried multiple times. Finally, in 1857, she settled in Austin with her fifth husband, Joseph William Hannig, where the family thrived.

The struggle for Texan independence ramped up after the Alamo, with soldiers joining the cause. Santa Anna began an inhumane policy of executing Texas prisoners and burning their bodies rather than burying them which was Christian custom. Peggy McCormick owned land on the San Jacinto river where the final battle of Texas Independence occurred. As the battle raged, Peggy and her sons fled their property and returned to find their corn crop and more than 230 livestock had been taken by both the Mexican and Texan armies. Moreover, the bodies of numerous Mexican soldiers were left to rot. Distraught by the state of her home, Peggy confronted Houston at his camp, urging him to remove the rotting corpses. He refused and encouraged her to appreciate the historic significance of her land. She was unimpressed and responded defiantly, “To the devil with your glorious history! Take off your stinking Mexicans."

Peggy McCormick

Peggy McCormick

Left with no alternative, Peggy McCormick and her two sons took it upon themselves to bury the bodies–continuing a tradition of women being the primary caretakers for the dead after battle.

Despite the hardships she faced, Peggy persevered and transformed her property into one of the largest cattle operations in Harris County. Regrettably, a considerable portion of her land was stolen from her due to an unethical land resurvey, a discovery made only after Peggy's passing in 1854.

Though Texas offered itself up for US annexation immediately upon receiving its independence from Mexico in 1836, it would not be until 1845 that this officially took place. Several factors contributed to this delay. Though American expansionists were driven by Manifest Destiny and hoped to acquire not just Texas, but all the territory to the west, Mexico threatened war with the United States should they annex Texas immediately. Furthermore, concern over what the annexation of Texas would mean in the post-Missouri Compromise and pre-Civil War era was another factor. Though many expansionists believed in the strength of American values and institutions which justified moral claims of hemispheric leadership, the political reality was that few wanted to battle over the potential admission of another slave state. As a result, from 1836-1845, Texas existed as its own independent republic.

Once the US took over the government for the Republic of Texas, they changed the legal system to English common law instead of the Spanish and Mexican legal systems that had been in place for years. The legal systems that had been in place in Texas provided women with rights that were unheard of to their Eastern counterpart. According to English law, "a married woman could not make a contract, could not own property, could not write a will, could sue or be sued, could not even fight for the custody of her own children because she did not have a legal identity separate from that of her husband." In Texas, women had been able to do all of those things. Fortunately, some of the Spanish systems were brought back when the statehood constitution was written in 1845. Tejano women suffered the most from the change in the legal system. By the time some of the Spanish systems came back, most of the Tejano women had lost all of their land to violence or fraud.

Despite the hardships she faced, Peggy persevered and transformed her property into one of the largest cattle operations in Harris County. Regrettably, a considerable portion of her land was stolen from her due to an unethical land resurvey, a discovery made only after Peggy's passing in 1854.

Though Texas offered itself up for US annexation immediately upon receiving its independence from Mexico in 1836, it would not be until 1845 that this officially took place. Several factors contributed to this delay. Though American expansionists were driven by Manifest Destiny and hoped to acquire not just Texas, but all the territory to the west, Mexico threatened war with the United States should they annex Texas immediately. Furthermore, concern over what the annexation of Texas would mean in the post-Missouri Compromise and pre-Civil War era was another factor. Though many expansionists believed in the strength of American values and institutions which justified moral claims of hemispheric leadership, the political reality was that few wanted to battle over the potential admission of another slave state. As a result, from 1836-1845, Texas existed as its own independent republic.

Once the US took over the government for the Republic of Texas, they changed the legal system to English common law instead of the Spanish and Mexican legal systems that had been in place for years. The legal systems that had been in place in Texas provided women with rights that were unheard of to their Eastern counterpart. According to English law, "a married woman could not make a contract, could not own property, could not write a will, could sue or be sued, could not even fight for the custody of her own children because she did not have a legal identity separate from that of her husband." In Texas, women had been able to do all of those things. Fortunately, some of the Spanish systems were brought back when the statehood constitution was written in 1845. Tejano women suffered the most from the change in the legal system. By the time some of the Spanish systems came back, most of the Tejano women had lost all of their land to violence or fraud.

Mexican-American War, Britannica

Mexican-American War, Britannica

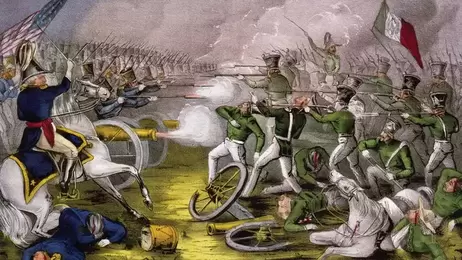

Mexican-American War:

The war in Texas for independence foreshadowed events that would take place in other parts of Northern Mexico. It’s difficult to generalize what happened since many of the Northern territories of Mexico had their own regional identities and power structures. However, for the most part, many citizens of the northern regions of Mexico either favored independence or American annexation. Few Nuevomexicanos or Californios saw a benefit in remaining part of the newly formed nation of Mexico–that had only barely acquired independence from Spain in 1821. Distant from the seat of Spanish-turned-Mexican power (in present-day Mexico City), elite families in these northern regions had essentially been isolated from the centralized government since the late 18th century. Thus, their allegiance to this new country of Mexico was perhaps as strong as their willingness to become part of the United States. They were more inclined to join whatever nation benefited their own economic interests.

In the 1840’s, just two decades after its Independence from Spain, Mexico was divided. The Mexican economy was dire and political upheavals were constant. As US soldiers marched through Mexico and established military bases, the Mexican president Santa Anna organized an army. However, given many of the growing pains associated with nation-building, this army was easily overcome by the US military. Some Mexicans supported the US invasion and others fought with all their means against the US.

Thousands of young men, some barely older than boys, took up arms and served on fields of battle. Women had very little say in the whole affair, but sewed regimental flags and sent their sons off to war. Sometimes enthusiastically. One self proclaimed “Spartan” mother wrote to her son that she would, “Sacrifice him at the cannon’s mouth, rather than find he had deserted… return with [your shield] or return upon it– with it or upon it.”

On the home front and on the battlefront, women from the US and Mexico had an impact on the war and its outcome. Women from both countries accompanied soldiers to war, sometimes in official capacity but often by their own choice. Whether serving as cooks, laundresses, nurses, or maids, these women were usually referred to simply as "camp followers.”

The war in Texas for independence foreshadowed events that would take place in other parts of Northern Mexico. It’s difficult to generalize what happened since many of the Northern territories of Mexico had their own regional identities and power structures. However, for the most part, many citizens of the northern regions of Mexico either favored independence or American annexation. Few Nuevomexicanos or Californios saw a benefit in remaining part of the newly formed nation of Mexico–that had only barely acquired independence from Spain in 1821. Distant from the seat of Spanish-turned-Mexican power (in present-day Mexico City), elite families in these northern regions had essentially been isolated from the centralized government since the late 18th century. Thus, their allegiance to this new country of Mexico was perhaps as strong as their willingness to become part of the United States. They were more inclined to join whatever nation benefited their own economic interests.

In the 1840’s, just two decades after its Independence from Spain, Mexico was divided. The Mexican economy was dire and political upheavals were constant. As US soldiers marched through Mexico and established military bases, the Mexican president Santa Anna organized an army. However, given many of the growing pains associated with nation-building, this army was easily overcome by the US military. Some Mexicans supported the US invasion and others fought with all their means against the US.

Thousands of young men, some barely older than boys, took up arms and served on fields of battle. Women had very little say in the whole affair, but sewed regimental flags and sent their sons off to war. Sometimes enthusiastically. One self proclaimed “Spartan” mother wrote to her son that she would, “Sacrifice him at the cannon’s mouth, rather than find he had deserted… return with [your shield] or return upon it– with it or upon it.”

On the home front and on the battlefront, women from the US and Mexico had an impact on the war and its outcome. Women from both countries accompanied soldiers to war, sometimes in official capacity but often by their own choice. Whether serving as cooks, laundresses, nurses, or maids, these women were usually referred to simply as "camp followers.”

María Josefa Zozaya

María Josefa Zozaya

Laundresses received one food ration a day and were paid based on the amount of clothing they washed. These women kept the soldiers clean, fed, and healthy. More importantly, camp followers raised troop morale and brought a bit of home to the monotony of daily camp life.

Mexican women frequently accompanied loved ones serving in the Mexican Army. A U.S. soldier noted seeing "a woman of 60 or more, a mother with an infant wrapped in her rebozo (shawl), a youthful Señorita frisking along with her lover's sombrero on her head, and a prattling girl who had followed father and mother to the war.”

During the Battle of Monterrey, María Josefa Zozaya worked tirelessly to bring food and water to all, regardless of nationality. While gently lifting a soldier's head into her lap and binding his wounds with her own handkerchief, she was struck and killed by gunfire. US soldiers buried her body "amid showers of grape and round shot." Deeply moved, soldiers on both sides praised her humanity in the midst of war. Songs and poems were written to commemorate the compassion of the "Maid of Monterrey."

Mexican women frequently accompanied loved ones serving in the Mexican Army. A U.S. soldier noted seeing "a woman of 60 or more, a mother with an infant wrapped in her rebozo (shawl), a youthful Señorita frisking along with her lover's sombrero on her head, and a prattling girl who had followed father and mother to the war.”

During the Battle of Monterrey, María Josefa Zozaya worked tirelessly to bring food and water to all, regardless of nationality. While gently lifting a soldier's head into her lap and binding his wounds with her own handkerchief, she was struck and killed by gunfire. US soldiers buried her body "amid showers of grape and round shot." Deeply moved, soldiers on both sides praised her humanity in the midst of war. Songs and poems were written to commemorate the compassion of the "Maid of Monterrey."

Sarah Bowman, Wikimedia Commons

Sarah Bowman, Wikimedia Commons

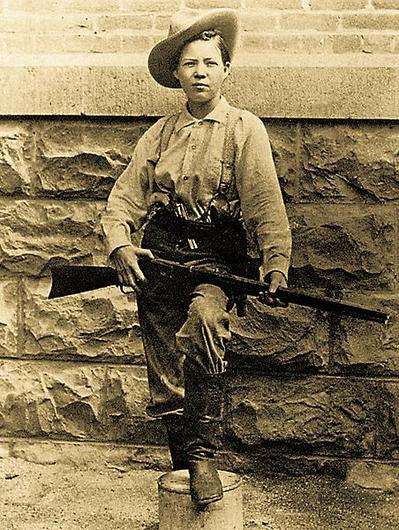

American women also were in harm's way. Sarah Bowman, was an entrepreneur and camp follower during the Mexican American War. She was nicknamed, “The Great Western.” She was a large woman, standing 6 feet tall, and was fluent in Spanish. She refused to take shelter and served food and water to the troops during a siege at Fort Texas. Even though a bullet went through her sunbonnet. Elizabeth Newcome, of Missouri, participated in the conquest of New Mexico by disguising herself as a man as countless women had done in every war before. Women fought for patriotism, a pension, and for adventure. Under the name "Bill" Newcome, she served as a Private for 10 months before her true identity was discovered by a doctor and she was forced to leave. She was discharged from duty, but still received a veteran's land bounty after the war.

Maria Gertrudis Barceló was a wealthy businesswoman operating in Santa Fe, New Mexico in the nineteenth century. She preferred to be called Madame La Tulas. She ran a saloon and gambling house. She also owned several rental properties. She used the money she earned to support her adopted children, as her two biological children had passed away as infants. She was a well known and respected woman in town.

Maria Gertrudis Barceló was a wealthy businesswoman operating in Santa Fe, New Mexico in the nineteenth century. She preferred to be called Madame La Tulas. She ran a saloon and gambling house. She also owned several rental properties. She used the money she earned to support her adopted children, as her two biological children had passed away as infants. She was a well known and respected woman in town.

“The Heroine of Tampico.”

“The Heroine of Tampico.”

American women also served as spies in the war. Ann McClarmonda Chase was married to Franklin Chase, the US Consul in Mexico. The information that she gathered led to the bloodless capture of Tampico by the United States Navy. She was given the nickname, “The Heroine of Tampico.”

Women also protested this war–believing it to be an unjust war for imperial land acquisition and, arguably, the expansion of American slavery. Most of the opposition came from the staunchly anti-slavery New England. Caroline Healy Dall wrote for a women’s rights magazine Una. She wrote a blistering piece entitled “The War” claiming, “No man with the least spark of true patriotism in his soul can look at the present condition of this country without shame, fear and foreboding… this is a great national crime.” In another piece she wrote, “American Woman! What think you of the horrid crimes, inseparable from war, committed by husbands, brothers, whom you and I have loved in the Mexican campaign? Can you offer your flushed cheeks in affectionate welcome of brutes and ravishers from their abandoned life?”

She had a point. American soldiers, on several occasions raped and pillaged Mexican cities– and women. An infantry lieutenant wrote home to his parents, “General Lane… told us to avenge the death of the gallant Walker, to… take all we could lay hands on… Old women and girls were stripped of their clothing— and many suffered still greater outrages.”

Margarett Fuller, a prominent well connected journalist who was abroad in Europe during the war decried, “this horrible cancer of slavery, and the wicked war that has grown out of it.”

Women also protested this war–believing it to be an unjust war for imperial land acquisition and, arguably, the expansion of American slavery. Most of the opposition came from the staunchly anti-slavery New England. Caroline Healy Dall wrote for a women’s rights magazine Una. She wrote a blistering piece entitled “The War” claiming, “No man with the least spark of true patriotism in his soul can look at the present condition of this country without shame, fear and foreboding… this is a great national crime.” In another piece she wrote, “American Woman! What think you of the horrid crimes, inseparable from war, committed by husbands, brothers, whom you and I have loved in the Mexican campaign? Can you offer your flushed cheeks in affectionate welcome of brutes and ravishers from their abandoned life?”

She had a point. American soldiers, on several occasions raped and pillaged Mexican cities– and women. An infantry lieutenant wrote home to his parents, “General Lane… told us to avenge the death of the gallant Walker, to… take all we could lay hands on… Old women and girls were stripped of their clothing— and many suffered still greater outrages.”

Margarett Fuller, a prominent well connected journalist who was abroad in Europe during the war decried, “this horrible cancer of slavery, and the wicked war that has grown out of it.”

Women on the California Trail

Women on the California Trail

Gold Rush:

While the government seized land westward as part of America’s Manifest Destiny, it relied on individual Americans to move west and populate it. This process was initially slow, but then accelerated with the discovery of Gold in California. Starting in 1848, at Sutter’s Mill in the California territory, the Gold Rush attracted Americans and foreigners. Boom towns rose and fell as settlers moved west in search of quick riches. The Gold Rushes and the subsequent expansion westward led to significant gender imbalances in many frontier towns and mining camps. The influx of predominantly male prospectors and settlers disrupted the traditional balance of men and women in the population.

Families in the east began preparing to move west and seek their fortune. The journey took over six months and required them to hunt, defend themselves against scavengers, and indigenous people they encountered, who likely weren’t thrilled by the thousands of new settlers in their territory. Women served wagon trains as nurses, cooks, and by performing other domestic services. Women traveled with their children, an added anxiety. Women sometimes traveled pregnant, which left them more susceptible to disease and death along the journey. Catherine Haun recalled that the only death on her voyage west was a mother who gave birth and died on the trail.

While the government seized land westward as part of America’s Manifest Destiny, it relied on individual Americans to move west and populate it. This process was initially slow, but then accelerated with the discovery of Gold in California. Starting in 1848, at Sutter’s Mill in the California territory, the Gold Rush attracted Americans and foreigners. Boom towns rose and fell as settlers moved west in search of quick riches. The Gold Rushes and the subsequent expansion westward led to significant gender imbalances in many frontier towns and mining camps. The influx of predominantly male prospectors and settlers disrupted the traditional balance of men and women in the population.

Families in the east began preparing to move west and seek their fortune. The journey took over six months and required them to hunt, defend themselves against scavengers, and indigenous people they encountered, who likely weren’t thrilled by the thousands of new settlers in their territory. Women served wagon trains as nurses, cooks, and by performing other domestic services. Women traveled with their children, an added anxiety. Women sometimes traveled pregnant, which left them more susceptible to disease and death along the journey. Catherine Haun recalled that the only death on her voyage west was a mother who gave birth and died on the trail.

Olive Oatman

Olive Oatman

Olive Oatman was taken into captivity when her family was traveling to California. Their brother survived and spent the next several years trying to find his sisters. Eventually, the Yavapai sold the Oatman sisters to the Mohave. The girls appear to have liked living among the Mohave. Tragically, a drought struck and Mary Ann didn’t survive. A few years after her capture, word got back to her brother that she was alive. Oatman was allowed to return to her brother. She eventually recounted her story to Rev. Royal B. Stratton who wrote the book Being an Interesting Narrative of the Captivity of the Oatman Girls (1857). She lived the remainder of her life in Sherman, Texas.

Luzena Stanley Wilson, her husband, and two young sons also packed their wagon and moved west to California. The journey was long and difficult and many people didn’t make it. One day, a miner approached her and offered to pay her $10 for a biscuit that was cooked by a woman. There weren’t many women in California. She thought he was crazy but accepted his offer and gave him a biscuit. Once in Sacramento, she learned that her skills were worth gold. The Wilsons bought into a small hotel and Luzena began cooking. Due to the gender imbalances in the area, Luzena’s domestic skills were valuable and she was able to charge exorbitant rates. Luzena became the bread winner of her household. Luzena said that she was treated like a “queen” because she reminded so many of the miners of their families back home.

Luzena Stanley Wilson, her husband, and two young sons also packed their wagon and moved west to California. The journey was long and difficult and many people didn’t make it. One day, a miner approached her and offered to pay her $10 for a biscuit that was cooked by a woman. There weren’t many women in California. She thought he was crazy but accepted his offer and gave him a biscuit. Once in Sacramento, she learned that her skills were worth gold. The Wilsons bought into a small hotel and Luzena began cooking. Due to the gender imbalances in the area, Luzena’s domestic skills were valuable and she was able to charge exorbitant rates. Luzena became the bread winner of her household. Luzena said that she was treated like a “queen” because she reminded so many of the miners of their families back home.

Bridget Biddy Mason

Bridget Biddy Mason

The scarcity of women gave those who migrated greater social and economic opportunities. Divorce laws were relaxed in many instances and became more socially acceptable. Women found themselves in high demand as domestic partners and workers in establishments like saloons, hotels, and restaurants. Some women used their relative scarcity to negotiate for higher wages or greater independence. Augusta Tabor gained wealth by investing in real estate in both Colorado and New Mexico, money she then funneled into her philanthropic pursuits such as the charitable Pioneer Ladies’ Aid Society that she co-founded in 1860. A more “respectable” profession for women was teaching. In a one room schoolhouse, the frontier town teacher instructed all the grades at once. Attendance at school was spotty at best, as children were needed to work on the farm or in the mines.

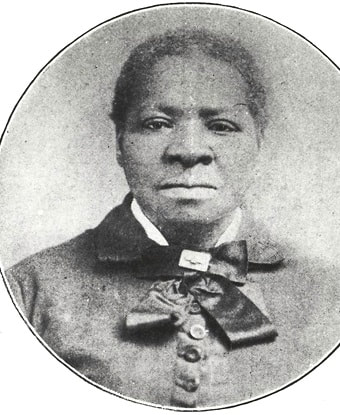

Black women also migrated west during the Gold Rush seeking better economic opportunities and a chance for social mobility. For enslaved Black women, the opportunity to escape the oppressive system of slavery was a significant motivation for migrating west. The western states, particularly California, had more favorable laws regarding the status of enslaved individuals, or were able to negotiate more leniency and flexibility within their enslaved condition because of the new locale. Either way, some saw the Gold Rush as an opportunity to gain freedom and independence. This became known as the “Great Exodus.” They experienced greater freedoms in the west than in the South, but life was still difficult.

Bridget Biddy Mason was an entrepreneur in California who was brought to the state as an enslaved woman and who ended up becoming a wealthy land-owning philanthropist in Los Angeles. Her 1856 court case challenging her enslavement won both her own freedom and that of thirteen of her family members. She saved the money she earned as a midwife and nurse to support her family. Eventually she purchased land in downtown Los Angeles–becoming one of the first Black women to do so. Biddy founded the First AME Church in 1872, which is the oldest African American church in the city. She was a well-known philanthropist and donated millions of dollars to different causes in LA, such as helping the poor and founding an elementary school for Black children. When she died in 1891, her estate was valued at more than $300,000–millions of dollars today.

Black women also migrated west during the Gold Rush seeking better economic opportunities and a chance for social mobility. For enslaved Black women, the opportunity to escape the oppressive system of slavery was a significant motivation for migrating west. The western states, particularly California, had more favorable laws regarding the status of enslaved individuals, or were able to negotiate more leniency and flexibility within their enslaved condition because of the new locale. Either way, some saw the Gold Rush as an opportunity to gain freedom and independence. This became known as the “Great Exodus.” They experienced greater freedoms in the west than in the South, but life was still difficult.

Bridget Biddy Mason was an entrepreneur in California who was brought to the state as an enslaved woman and who ended up becoming a wealthy land-owning philanthropist in Los Angeles. Her 1856 court case challenging her enslavement won both her own freedom and that of thirteen of her family members. She saved the money she earned as a midwife and nurse to support her family. Eventually she purchased land in downtown Los Angeles–becoming one of the first Black women to do so. Biddy founded the First AME Church in 1872, which is the oldest African American church in the city. She was a well-known philanthropist and donated millions of dollars to different causes in LA, such as helping the poor and founding an elementary school for Black children. When she died in 1891, her estate was valued at more than $300,000–millions of dollars today.

Mary Ellen Pleasant

Mary Ellen Pleasant

Black women recognized that the booming Gold Rush towns presented various business prospects. They engaged in entrepreneurial activities such as opening boarding houses, restaurants, laundries, and other services that catered to the needs of the growing population.

Mary Ellen Pleasant was a Black woman involved in abolitionist work who moved to San Francisco in 1852. She obtained shrewd financial advice from her male business customers as she was working as a housekeeper. Her investments in real estate and mining paid richly and she was a generous philanthropist to the local Black community, such as financing the early library in San Francisco.

Free-born, Mary Ellen Pleasant operated boarding houses in San Francisco for elite white men. She used her amassed wealth to invest in the homes and became a self-made millionaire. She used her wealth to further support the abolitionist movement in California.

Mary Ellen Pleasant was a Black woman involved in abolitionist work who moved to San Francisco in 1852. She obtained shrewd financial advice from her male business customers as she was working as a housekeeper. Her investments in real estate and mining paid richly and she was a generous philanthropist to the local Black community, such as financing the early library in San Francisco.

Free-born, Mary Ellen Pleasant operated boarding houses in San Francisco for elite white men. She used her amassed wealth to invest in the homes and became a self-made millionaire. She used her wealth to further support the abolitionist movement in California.

Chinese immigrants also came in the thousands to seek their fortunes. Chinese women, though few in number in the middle of the 19th century, were often subjected to discrimination and disapproval from Anglo Americans but were tolerated, as they provided a very much needed working force. Lai Wah Howe in Sacramento and Yee Shee Tsoong in Nevada City ran successful businesses.

Mormons:

Many early migrants were Mormon pilgrims driven from their homes in Missouri and Illinois. Latter-day Saints saw migrating westward as the start to new lives where they could freely practice their religion. They were pioneers, but also refugees.

Mormons:

Many early migrants were Mormon pilgrims driven from their homes in Missouri and Illinois. Latter-day Saints saw migrating westward as the start to new lives where they could freely practice their religion. They were pioneers, but also refugees.

Patty Bartlett Sessions

Patty Bartlett Sessions

Like many Mormon women, Patty Bartlett Sessions gained her place in history by practicing midwifery. She participated in the westward movement of eastern Americans, ending her life in the Rocky Mountains valleys, two thousand miles from Maine, her native town. Her diary gives us an account of Mormon women who dedicated their lives to their communities, particularly to the formation of western Zion. Thanks to her letters we can get a glimpse of the lives of the women and their involvement in commerce, education, government, and the court system. We also see how Mormon women grappled with religious and domestic affairs, such as dealing with other wives.

As a midwife, Patty Bartlett Sessions was a central figure in the community and she delivered nearly 4,000 babies–one of the highest documented case loads among pioneering women.

She was an active member of her community presiding the Relief Society, a philanthropic and educational women’s organization founded in 1842 to address the physical and spiritual needs of the LDS community. Female benevolent societies became clearinghouses for employment, safe housing, informal economies, and socially-acceptable political action for women.

As a midwife, Patty Bartlett Sessions was a central figure in the community and she delivered nearly 4,000 babies–one of the highest documented case loads among pioneering women.

She was an active member of her community presiding the Relief Society, a philanthropic and educational women’s organization founded in 1842 to address the physical and spiritual needs of the LDS community. Female benevolent societies became clearinghouses for employment, safe housing, informal economies, and socially-acceptable political action for women.

Martha Hughes Cannon

Martha Hughes Cannon

However despite moving west to Utah, Mormonism remained controversial especially due to its tolerance of polygamous marriages, where one man has multiple wives. According to historian Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, plural marriage was a complicated lot for women. She said, “Plural marriage empowered women in very complicated ways, and to put it most simply, it added to the complexity and the adversity they experienced… It also reinforced an already well developed community of women to share work, to share childcare, to share religious faith, to share care in childbirth and in illness, in some sense strengthened bonds that were already very much present in their lives.”

This complicated nature is illustrated in the life of Martha Hughes Cannon, a doctor who became the fourth of eventually six wives in a polygamous marriage. After giving birth to her first child, proof that her relationship was sexual, she had to flee to England using the 'Mormon Underground' network to avoid testifying against her husband in court during a period of government crackdowns on polygamy.

Utah was the first to grant women the right to vote on an equal footing with men in 1869. Many Mormons supported women’s suffrage, and primary sources from the women’s meetings show that it was Mormon women who asked for the vote. While other suffragists were advocating for voting rights for other reasons, many Mormon women in polygamous marriages wanted political power and voting rights to protect the institution of polygamy–the “right to choose my own husband” as historian Laurel Thatcher Ulrich describes it. As a prominent figure in Utah's women's suffrage movement, Cannon played a crucial role in enshrining women's suffrage in the state's constitution.

This complicated nature is illustrated in the life of Martha Hughes Cannon, a doctor who became the fourth of eventually six wives in a polygamous marriage. After giving birth to her first child, proof that her relationship was sexual, she had to flee to England using the 'Mormon Underground' network to avoid testifying against her husband in court during a period of government crackdowns on polygamy.

Utah was the first to grant women the right to vote on an equal footing with men in 1869. Many Mormons supported women’s suffrage, and primary sources from the women’s meetings show that it was Mormon women who asked for the vote. While other suffragists were advocating for voting rights for other reasons, many Mormon women in polygamous marriages wanted political power and voting rights to protect the institution of polygamy–the “right to choose my own husband” as historian Laurel Thatcher Ulrich describes it. As a prominent figure in Utah's women's suffrage movement, Cannon played a crucial role in enshrining women's suffrage in the state's constitution.

Early in life, as the LDS Church was encouraging women into medicine, Cannon decided to train as a doctor. In 1878, she graduated from University of Deseret with a degree in Chemistry, before being selected by the Church to study at the University of Michigan and become a doctor. Upon her return to Utah, she worked at Deseret Hospital, where she met her future husband, Angus Munn Cannon. She was his fourth wife.

After getting married in 1884, suspicions of polygamy brought federal officers, who sought Martha Hughes Cannon in order that she testify in court. In 1890, the US Supreme Court had ruled that laws prohibiting polygamy were legal. Mormons officially practiced polygamy until September 1890 when religious leaders reluctantly issued the “Mormon Manifesto” stating that the LDS Church would abide by the anti-polygamy laws of the US. Cannon was forced to flee, eventually returning to the U.S. and establishing Utah's inaugural nurse's training school in 1888. Additionally, Cannon was instrumental in setting up Utah's first board of health and establishing a school for the deaf and blind.

Then in 1896, Cannon became the first female state senator in the country after defeating her own husband. She said, “Women will purify politics. Women are better than men and will do the world of politics good.”

Then, in her first term, she became pregnant with her third child, again evidence of a sexual marriage. Her husband was arrested. Her career in politics was over. She said, “Life is made up of profit and loss, and loss seems to be the prevailing element in my career at present.” Hughes relocated to California with her children and continued her career as a physician.

After getting married in 1884, suspicions of polygamy brought federal officers, who sought Martha Hughes Cannon in order that she testify in court. In 1890, the US Supreme Court had ruled that laws prohibiting polygamy were legal. Mormons officially practiced polygamy until September 1890 when religious leaders reluctantly issued the “Mormon Manifesto” stating that the LDS Church would abide by the anti-polygamy laws of the US. Cannon was forced to flee, eventually returning to the U.S. and establishing Utah's inaugural nurse's training school in 1888. Additionally, Cannon was instrumental in setting up Utah's first board of health and establishing a school for the deaf and blind.

Then in 1896, Cannon became the first female state senator in the country after defeating her own husband. She said, “Women will purify politics. Women are better than men and will do the world of politics good.”

Then, in her first term, she became pregnant with her third child, again evidence of a sexual marriage. Her husband was arrested. Her career in politics was over. She said, “Life is made up of profit and loss, and loss seems to be the prevailing element in my career at present.” Hughes relocated to California with her children and continued her career as a physician.

Gender Fluidity:

The Western Frontier during the early 19th century provided an emerging unique and fairly lawless environment, offering a blank canvas for individuals seeking a fresh start on the fringes of society. In the absence of stringent laws and federal enforcement, the West became a haven where one could redefine not only their life but also their notions of gender and sexuality. As historian Peter Boag observed, this vast frontier was more than just uncharted territory; it was a space where individuals could freely express themselves and find a measure of private safety. While societal acceptance may not have been universal, the West provided a pioneering backdrop for the exploration and redefinition of identity, including the nuanced history of cross-dressing and the expression of diverse gender identities.

The reasons for crossing-dressing and many probable transgender identities in the West are numerous. Some adopted cross-dressing to evade the law, less as an expression of gender, but as a tool to ensure freedom and evasion from authorities. As the West was fairly lawless, danger was prevalent in the travel across the new frontier. Women obviously faced danger, not only because of the nature of the emerging West but also the everyday dangers women all over the U.S. and the world faced. To combat these threats and unpredictable dangers, cross-dressing provided a practical strategy for safe travel through hazardous areas, offering a layer of anonymity and protection. Moreover, seeking employment in a region marked by opportunities but also by limited resources and unconventional occupations, individuals found that cross-dressing could be a pragmatic choice. Importantly, for many, this expression of gender identity did not function as only a temporary disguise but a fundamental aspect of who they were. The motivations behind cross-dressing in the Western Frontier are uncovered through various historical sources, including public records, newspapers documenting the peculiarities of frontier life, and oral traditions passed down through word of mouth. However, it's crucial to acknowledge that many of these individuals remain elusive to historical documentation, leaving gaps in our understanding of their experiences and identities.

Understanding cases of transwomen in the West is complex, nuanced, and information can be scarce. Importantly, the concept of transgender identity as we understand it today did not exist during the 1800s. Consequently, it becomes challenging to definitively label individuals as transgender. However, exploration by queer historians often reveals instances of men or women living for extended periods within the gender opposite to that assigned at birth, only to be discovered as trans or cross-dressing after death or by accident. In the vast expanses of the American West, the lived experiences of trans women remain notably absent from historical records, primarily attributed to the lack of safety and comfort for individuals choosing to live openly as women. Historian Peter Boag, in his extensive research, encountered far fewer stories of trans women in comparison to other narratives from the era. The scarcity of such accounts is not indicative of the absence of transgender individuals but rather underscores the challenging circumstances that discouraged the open expression of gender identity.

One example of the few likely trans women found in the West is the case of Mrs. Nash. Born in Mexico and initially assigned male at birth, Mrs. Nash had a significant role as a laundress for the Seventh Cavalry in Montana for over a decade during the 1800s. During this period, she not only fulfilled her professional duties but also forged personal connections by marrying three different enlisted men. After her death in 1878 due to appendicitis, Mrs. Nash’s male appendage was discovered when her body was being prepared for burial. Subsequent coverage in national papers portrayed Nash as an outsider with a suspect gender, contrary to the firsthand accounts documented in the Bismarck Tribune. According to eyewitnesses, Nash was a respected woman known for her skills as an interior decorator, midwife, and particularly as a celebrated tamale cook. However, racialized descriptions that, were common during the era, were employed to cast doubt open her character, underscoring the intersectionality of gender and race in shaping perceptions of individuals like Mrs. Nash within society. Mrs. Nash’s experience was indicative of a larger trend that faced queer people within the West. Despite the freedom the Western frontier provided, it still held deeply repressive views of queer individuals.

The Western Frontier of the 19th century served as a dynamic and lawless backdrop that allowed individuals to redefine their lives and identities. The exploration of cross-dressing and diverse gender expressions in this environment unveils a complex tapestry of motivations, from evading the law to ensuring safety in hazardous travels and seeking pragmatic employment opportunities. The West, while pioneering in its acceptance of diverse identities, still grappled with societal challenges and repressive views toward queer individuals. The nuanced history of trans women in the West remains elusive, given the lack of safety and comfort for those openly embracing their gender identities. Despite the challenges, the Western Frontier stands as a pivotal space where individuals could explore and redefine their identities, leaving a legacy that is both intricate and, at times, shrouded in historical obscurity.

The Western Frontier during the early 19th century provided an emerging unique and fairly lawless environment, offering a blank canvas for individuals seeking a fresh start on the fringes of society. In the absence of stringent laws and federal enforcement, the West became a haven where one could redefine not only their life but also their notions of gender and sexuality. As historian Peter Boag observed, this vast frontier was more than just uncharted territory; it was a space where individuals could freely express themselves and find a measure of private safety. While societal acceptance may not have been universal, the West provided a pioneering backdrop for the exploration and redefinition of identity, including the nuanced history of cross-dressing and the expression of diverse gender identities.

The reasons for crossing-dressing and many probable transgender identities in the West are numerous. Some adopted cross-dressing to evade the law, less as an expression of gender, but as a tool to ensure freedom and evasion from authorities. As the West was fairly lawless, danger was prevalent in the travel across the new frontier. Women obviously faced danger, not only because of the nature of the emerging West but also the everyday dangers women all over the U.S. and the world faced. To combat these threats and unpredictable dangers, cross-dressing provided a practical strategy for safe travel through hazardous areas, offering a layer of anonymity and protection. Moreover, seeking employment in a region marked by opportunities but also by limited resources and unconventional occupations, individuals found that cross-dressing could be a pragmatic choice. Importantly, for many, this expression of gender identity did not function as only a temporary disguise but a fundamental aspect of who they were. The motivations behind cross-dressing in the Western Frontier are uncovered through various historical sources, including public records, newspapers documenting the peculiarities of frontier life, and oral traditions passed down through word of mouth. However, it's crucial to acknowledge that many of these individuals remain elusive to historical documentation, leaving gaps in our understanding of their experiences and identities.

Understanding cases of transwomen in the West is complex, nuanced, and information can be scarce. Importantly, the concept of transgender identity as we understand it today did not exist during the 1800s. Consequently, it becomes challenging to definitively label individuals as transgender. However, exploration by queer historians often reveals instances of men or women living for extended periods within the gender opposite to that assigned at birth, only to be discovered as trans or cross-dressing after death or by accident. In the vast expanses of the American West, the lived experiences of trans women remain notably absent from historical records, primarily attributed to the lack of safety and comfort for individuals choosing to live openly as women. Historian Peter Boag, in his extensive research, encountered far fewer stories of trans women in comparison to other narratives from the era. The scarcity of such accounts is not indicative of the absence of transgender individuals but rather underscores the challenging circumstances that discouraged the open expression of gender identity.

One example of the few likely trans women found in the West is the case of Mrs. Nash. Born in Mexico and initially assigned male at birth, Mrs. Nash had a significant role as a laundress for the Seventh Cavalry in Montana for over a decade during the 1800s. During this period, she not only fulfilled her professional duties but also forged personal connections by marrying three different enlisted men. After her death in 1878 due to appendicitis, Mrs. Nash’s male appendage was discovered when her body was being prepared for burial. Subsequent coverage in national papers portrayed Nash as an outsider with a suspect gender, contrary to the firsthand accounts documented in the Bismarck Tribune. According to eyewitnesses, Nash was a respected woman known for her skills as an interior decorator, midwife, and particularly as a celebrated tamale cook. However, racialized descriptions that, were common during the era, were employed to cast doubt open her character, underscoring the intersectionality of gender and race in shaping perceptions of individuals like Mrs. Nash within society. Mrs. Nash’s experience was indicative of a larger trend that faced queer people within the West. Despite the freedom the Western frontier provided, it still held deeply repressive views of queer individuals.

The Western Frontier of the 19th century served as a dynamic and lawless backdrop that allowed individuals to redefine their lives and identities. The exploration of cross-dressing and diverse gender expressions in this environment unveils a complex tapestry of motivations, from evading the law to ensuring safety in hazardous travels and seeking pragmatic employment opportunities. The West, while pioneering in its acceptance of diverse identities, still grappled with societal challenges and repressive views toward queer individuals. The nuanced history of trans women in the West remains elusive, given the lack of safety and comfort for those openly embracing their gender identities. Despite the challenges, the Western Frontier stands as a pivotal space where individuals could explore and redefine their identities, leaving a legacy that is both intricate and, at times, shrouded in historical obscurity.

Prostitution:

In areas heavily impacted by the Gold Rushes, such as California, Nevada, Colorado, and later the Klondike region of the Yukon in northwestern Canada, the sex ratios were often highly skewed, with a significantly higher number of men compared to women. The ratio could be as extreme as 9 or 10 men for every woman in some mining communities. This created a scarcity of women and a competitive environment among men for their attention and companionship.

The gender imbalance led to the development of unique social practices such as dance halls, matchmaking events, and mail-order bride systems, which facilitated the formation of relationships between men and women. With fewer women available, the competition among men for marriage and relationships increased. Interestingly, in history where there are fewer women, there are also higher rates of violent crime– the west was no exception.

The imbalanced sex ratio and the high concentration of men in frontier towns created a demand for commercial sex. Prostitution became prevalent, with brothels and red-light districts emerging as part of the social fabric of many Wild West communities. While sex work comes with notable risks, for some women, it provided a means of economic independence–not unlike other gendered, domestic labor like cooking and laundry.

Pearl DeVere, also known as Pearl Dabney, was a famous madam and businesswoman in Cripple Creek, Colorado. She established and operated a high-class brothel in the booming mining town. Her establishment, known as "The Old Homestead," was reputed for its opulence and luxury, catering to wealthy and influential clients, including prominent politicians and businessmen. She was refined, stylish, and became a notable and respected figure who participated in charity work. DeVere was, however, the exception, not the rule for the profession of prostitution which often was exploitative and dangerous for women, especially women of color.

In areas heavily impacted by the Gold Rushes, such as California, Nevada, Colorado, and later the Klondike region of the Yukon in northwestern Canada, the sex ratios were often highly skewed, with a significantly higher number of men compared to women. The ratio could be as extreme as 9 or 10 men for every woman in some mining communities. This created a scarcity of women and a competitive environment among men for their attention and companionship.

The gender imbalance led to the development of unique social practices such as dance halls, matchmaking events, and mail-order bride systems, which facilitated the formation of relationships between men and women. With fewer women available, the competition among men for marriage and relationships increased. Interestingly, in history where there are fewer women, there are also higher rates of violent crime– the west was no exception.

The imbalanced sex ratio and the high concentration of men in frontier towns created a demand for commercial sex. Prostitution became prevalent, with brothels and red-light districts emerging as part of the social fabric of many Wild West communities. While sex work comes with notable risks, for some women, it provided a means of economic independence–not unlike other gendered, domestic labor like cooking and laundry.

Pearl DeVere, also known as Pearl Dabney, was a famous madam and businesswoman in Cripple Creek, Colorado. She established and operated a high-class brothel in the booming mining town. Her establishment, known as "The Old Homestead," was reputed for its opulence and luxury, catering to wealthy and influential clients, including prominent politicians and businessmen. She was refined, stylish, and became a notable and respected figure who participated in charity work. DeVere was, however, the exception, not the rule for the profession of prostitution which often was exploitative and dangerous for women, especially women of color.

Polly Bemis

Polly Bemis

Ah Tou, also known as Polly Bemis, is considered the first Chinese woman immigrant who became famous for her story of resilience and survival. She was sold into slavery in China and brought to the United States, where she worked as a domestic servant and later married a Chinese miner in Idaho. Despite her somewhat happy ending, prostitution was horrible for Chinese women. At the time, Chinese women were a rarity in the west, as most Chinese men had come to seek their fortunes during the California Gold Rush and left their families behind in China. Cultural norms in China also prevented many women from emmigrating. When coupled with laws like the Page Act of 1875 that would limit the immigration of Chinese women to the United states, this gender imbalance created a demand for female companionship–thus making sex work lucrative.

Prostitution in San Francisco's Chinatown was orchestrated by secretive Chinese societies known as "tongs." These tongs, while providing protection and opportunities for new immigrants, were also notorious criminal enterprises. They kidnapped and purchased Chinese women and girls to meet the growing demand for the sex trade. The lucrative profits from this business allowed the tongs to expand their influence, dominate immigrant neighborhoods, and engage in other criminal activities.

While some girls were kidnapped during political upheavals in China, such as the Opium Wars and the Taiping Rebellion, others were sold into bondage by their own families. Daughters were deemed inferior to sons in Chinese society, as they were unable to provide physical labor or carry on the ancestral name. Their inferior status made them expendable, and it was considered acceptable to dispose of them when circumstances dictated.

When coupled with laws like the Page Act of 1875 that would limit the immigration of Chinese women to the United states, this gender imbalance created a demand for female companionship–thus making sex work lucrative.

Prostitution in San Francisco's Chinatown was orchestrated by secretive Chinese societies known as "tongs." These tongs, while providing protection and opportunities for new immigrants, were also notorious criminal enterprises. They kidnapped and purchased Chinese women and girls to meet the growing demand for the sex trade. The lucrative profits from this business allowed the tongs to expand their influence, dominate immigrant neighborhoods, and engage in other criminal activities.

While some girls were kidnapped during political upheavals in China, such as the Opium Wars and the Taiping Rebellion, others were sold into bondage by their own families. Daughters were deemed inferior to sons in Chinese society, as they were unable to provide physical labor or carry on the ancestral name. Their inferior status made them expendable, and it was considered acceptable to dispose of them when circumstances dictated.

Prostitution in San Francisco's Chinatown was orchestrated by secretive Chinese societies known as "tongs." These tongs, while providing protection and opportunities for new immigrants, were also notorious criminal enterprises. They kidnapped and purchased Chinese women and girls to meet the growing demand for the sex trade. The lucrative profits from this business allowed the tongs to expand their influence, dominate immigrant neighborhoods, and engage in other criminal activities.

While some girls were kidnapped during political upheavals in China, such as the Opium Wars and the Taiping Rebellion, others were sold into bondage by their own families. Daughters were deemed inferior to sons in Chinese society, as they were unable to provide physical labor or carry on the ancestral name. Their inferior status made them expendable, and it was considered acceptable to dispose of them when circumstances dictated.

When coupled with laws like the Page Act of 1875 that would limit the immigration of Chinese women to the United states, this gender imbalance created a demand for female companionship–thus making sex work lucrative.

Prostitution in San Francisco's Chinatown was orchestrated by secretive Chinese societies known as "tongs." These tongs, while providing protection and opportunities for new immigrants, were also notorious criminal enterprises. They kidnapped and purchased Chinese women and girls to meet the growing demand for the sex trade. The lucrative profits from this business allowed the tongs to expand their influence, dominate immigrant neighborhoods, and engage in other criminal activities.

While some girls were kidnapped during political upheavals in China, such as the Opium Wars and the Taiping Rebellion, others were sold into bondage by their own families. Daughters were deemed inferior to sons in Chinese society, as they were unable to provide physical labor or carry on the ancestral name. Their inferior status made them expendable, and it was considered acceptable to dispose of them when circumstances dictated.

Group of Prostitutes

Group of Prostitutes

The value of a girl sold into prostitution overseas far exceeded that of one sold within China. Families facing economic hardship often made the heartbreaking decision to sell their daughters abroad in the hopes of giving them a better life. Most girls, out of filial loyalty, accepted their family's decision and allowed themselves to be sold to "labor contractors" in China. Sing Kum, sold into slavery as a child, recalled, “My father came to see me once… He seemed very sad, and when he went away he gave me some cash and wished me prosperity. That was the last time I saw him. I was sold four times. I came to California about five years ago. My last mistress was very cruel to me. She used to whip me, pull my hair, and pinch the inside of my cheeks. A friend of mine told me about this place and that night I ran away… I was afraid my mistress was coming after me. I rang the bell twice, and when the door was opened I ran in quickly. I thank God that he led me to this place….”

Upon arrival in San Francisco, these young women were confined in barracoons, reminiscent of the African slave trade. Those purchased for tong brothels were handed over to their owners, while those still unsold were put up for auction.

Upon meeting their owners, the Chinese women, despite their often illiteracy, were coerced into signing contracts binding them as prostitutes for several years. Some of the more attractive girls became concubines of wealthy owners, who might treat them relatively decently. However, if they failed to please their masters, they could be returned to the auction block. Most of the girls ended up in "cribs," shacks frequented by sailors, laborers, and drunkards, both Chinese and white, who paid meager fees for their services.

Upon arrival in San Francisco, these young women were confined in barracoons, reminiscent of the African slave trade. Those purchased for tong brothels were handed over to their owners, while those still unsold were put up for auction.

Upon meeting their owners, the Chinese women, despite their often illiteracy, were coerced into signing contracts binding them as prostitutes for several years. Some of the more attractive girls became concubines of wealthy owners, who might treat them relatively decently. However, if they failed to please their masters, they could be returned to the auction block. Most of the girls ended up in "cribs," shacks frequented by sailors, laborers, and drunkards, both Chinese and white, who paid meager fees for their services.

Ah Toy

Ah Toy

Ah Toy was one of the most famous Chinese women in San Francisco during the Gold Rush. She arrived in California in the 1850s and became a successful businesswoman, running a brothel and becoming a prominent figure in the city's Chinese community. Chinese brothel owners fared better than other Chinese businessmen, making substantial profits and exerting control over prostitution, gambling, and the opium trade, this also made them a target.

In 1855, Ah Toy sued a man named Charles P. Duane for assault and battery. Duane had attacked her in her own residence, causing her physical harm. Ah Toy pursued legal action against him, seeking compensation for the damages inflicted upon her.

The court case was significant because it highlighted the challenges faced by Chinese immigrants in the legal system, as well as the resilience and determination of Ah Toy to protect her rights. Ultimately, Ah Toy was successful in her lawsuit, with the court ruling in her favor and awarding her damages. This case showcased Ah Toy's courage and contributed to her reputation as a strong and independent woman in the Chinese community during that time.

The conditions in California brothels, primarily concentrated in San Francisco and Los Angeles, were deplorable. The indentured girls were mistreated by customers, received minimal care, and were denied medical attention. Homesick and untreated for venereal diseases or other illnesses, most women endured physical and emotional breakdowns, rarely surviving more than five or six years in bondage. Some girls, who entered the trade at the tender age of 14, died before reaching the age of 20.

In 1855, Ah Toy sued a man named Charles P. Duane for assault and battery. Duane had attacked her in her own residence, causing her physical harm. Ah Toy pursued legal action against him, seeking compensation for the damages inflicted upon her.

The court case was significant because it highlighted the challenges faced by Chinese immigrants in the legal system, as well as the resilience and determination of Ah Toy to protect her rights. Ultimately, Ah Toy was successful in her lawsuit, with the court ruling in her favor and awarding her damages. This case showcased Ah Toy's courage and contributed to her reputation as a strong and independent woman in the Chinese community during that time.

The conditions in California brothels, primarily concentrated in San Francisco and Los Angeles, were deplorable. The indentured girls were mistreated by customers, received minimal care, and were denied medical attention. Homesick and untreated for venereal diseases or other illnesses, most women endured physical and emotional breakdowns, rarely surviving more than five or six years in bondage. Some girls, who entered the trade at the tender age of 14, died before reaching the age of 20.

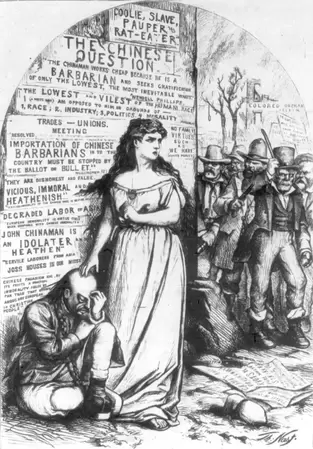

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882

When a Chinese prostitute could no longer earn her keep, a harrowing ritual ensued (. The prostitute would be informed that she must die and locked in a dingy, windowless room with meager provisions. Days later, when the lamp had burned out, her executioners would enter to remove the woman, who was usually dead from starvation or suicide. In other cases, the ailing prostitute would be simply cast out onto the street to die. The streets of Chinatown in 1870 were strewn with the bodies of deceased prostitutes. Some chose to end their lives by consuming raw opium or jumping into the bay.

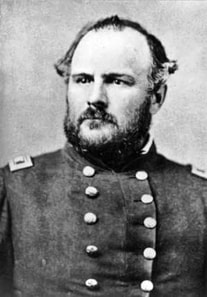

Despite the abhorrent and inhumane nature of the situation, local officials took no action to address the issue. Chinese immigrants were treated as inferior by other settlers, so their mistreatment was seemingly not a concern. The girls from China kept coming. In 1869, a significant number of 369 contracted Chinese slave girls arrived in San Francisco on a Pacific Mail steamer. Captain William Douglas of the San Francisco Police, accompanied by 18 officers, created a spectacle of apprehending them at the Brannan Street docks and promptly delivered them to the Chinatown brothels. Eight months later, Douglas and his men repeated this process with another group of 246 girls who had landed in San Francisco. As Chinese immigration increased, the proportion of prostitutes among Chinese women decreased to 71 percent by 1870 and further dropped to 21 percent by 1880. Despite the federal Page Act of 1875 aiming to prevent the immigration of women suspected of prostitution from "China, Japan, or any East Asian country," the tongs and their accomplices largely disregarded its provisions. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 went even further by banning the immigration of all Chinese laborers. Nevertheless, Chinese women continued to enter the country illegally, aided by corrupt politicians and police officers, resulting in a subsequent surge of prostitution across the state.

Despite the abhorrent and inhumane nature of the situation, local officials took no action to address the issue. Chinese immigrants were treated as inferior by other settlers, so their mistreatment was seemingly not a concern. The girls from China kept coming. In 1869, a significant number of 369 contracted Chinese slave girls arrived in San Francisco on a Pacific Mail steamer. Captain William Douglas of the San Francisco Police, accompanied by 18 officers, created a spectacle of apprehending them at the Brannan Street docks and promptly delivered them to the Chinatown brothels. Eight months later, Douglas and his men repeated this process with another group of 246 girls who had landed in San Francisco. As Chinese immigration increased, the proportion of prostitutes among Chinese women decreased to 71 percent by 1870 and further dropped to 21 percent by 1880. Despite the federal Page Act of 1875 aiming to prevent the immigration of women suspected of prostitution from "China, Japan, or any East Asian country," the tongs and their accomplices largely disregarded its provisions. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 went even further by banning the immigration of all Chinese laborers. Nevertheless, Chinese women continued to enter the country illegally, aided by corrupt politicians and police officers, resulting in a subsequent surge of prostitution across the state.

Tye Leung

Tye Leung

These laws were not inspired by a desire to help Chinese women, but were fueled by growing anti-Chinese sentiment in the United States, by economic competition, racial prejudices, and fears of cultural differences. Some Americans believed that Chinese immigrants were taking jobs away from native-born workers and undermining wages. There was a prevailing perception among certain segments of American society that Chinese immigrants were morally inferior and posed a threat to American society. This sentiment was particularly focused on Chinese women, who were often stereotyped as prostitutes or potential carriers of disease. Policymakers and lawmakers feared that the Chinese population in the United States would rapidly grow if not regulated.

Over time, the circumstances for some Chinese women in San Francisco began to improve. Tye Leung, for example, was born in San Francisco in 1887 to working-class Chinese parents. She volunteered at a shelter for rescued Chinese prostitutes and later became the first Chinese American to pass civil service exams. She worked as an assistant at Angel Island Immigration Station and made history by casting her ballot in the 1912 presidential election, becoming the first Chinese woman worldwide to exercise the electoral franchise.

Despite the dire situation in San Francisco, the experiences of Chinese women varied in other Western locations. In Oregon, few Chinese women were owned by tongs and engaged in prostitution. In Nevada, many Chinese women worked as prostitutes in opium dens, some voluntarily and others under coercion. Chinese prostitutes in Idaho Territory attempted to escape, often with the help of lovers, but were typically arrested and released once their owners posted bail.

Over time, the circumstances for some Chinese women in San Francisco began to improve. Tye Leung, for example, was born in San Francisco in 1887 to working-class Chinese parents. She volunteered at a shelter for rescued Chinese prostitutes and later became the first Chinese American to pass civil service exams. She worked as an assistant at Angel Island Immigration Station and made history by casting her ballot in the 1912 presidential election, becoming the first Chinese woman worldwide to exercise the electoral franchise.

Despite the dire situation in San Francisco, the experiences of Chinese women varied in other Western locations. In Oregon, few Chinese women were owned by tongs and engaged in prostitution. In Nevada, many Chinese women worked as prostitutes in opium dens, some voluntarily and others under coercion. Chinese prostitutes in Idaho Territory attempted to escape, often with the help of lovers, but were typically arrested and released once their owners posted bail.

"China Annie"

"China Annie"