25. 1850-1950 Women’s Lives Under Imperialism

|

During the imperial era, women were both active agents and survivors of colonialism. European women spread imperial ideas and participated as missionaries, but also struggled against European imperialism. Colonized women also had diverse responses to colonialism, which varied depending on location, class, and local customs.

This section has some heavy moments, so trigger warning for sexual assault. |

"Civilization" Propaganda, Public Domain

"Civilization" Propaganda, Public Domain

In 1899, Rudyard Kipling looked back on four centuries of British imperialism and encouraged the rising American empire to do the same. He wrote:

“Take up the White Man’s burden--

Send forth the best ye breed--

Go send your sons to exile

To serve your captives' need”

His use of masculine pronouns is misleading, as women both took part in and were affected by imperialism.

Between the 16th and 19th centuries, a few European powers came to dominate and control large swathes of the Earth, including most of Africa, South Asia, Southeast Asia, the Americas, Siberia, and more. The British empire at its height, for example, ruled one quarter of the world’s land. Such imperialism transformed forever the countries and cultures that were colonized.. While the conquering and “civilizing” of people of color was labeled by Kipling a “White Man’s Burden,” imperialism also transformed the lives of women across the world.

“Take up the White Man’s burden--

Send forth the best ye breed--

Go send your sons to exile

To serve your captives' need”

His use of masculine pronouns is misleading, as women both took part in and were affected by imperialism.

Between the 16th and 19th centuries, a few European powers came to dominate and control large swathes of the Earth, including most of Africa, South Asia, Southeast Asia, the Americas, Siberia, and more. The British empire at its height, for example, ruled one quarter of the world’s land. Such imperialism transformed forever the countries and cultures that were colonized.. While the conquering and “civilizing” of people of color was labeled by Kipling a “White Man’s Burden,” imperialism also transformed the lives of women across the world.

Depiction of Sati, Public Domain

Depiction of Sati, Public Domain

The British in India

The lives of women under imperialism differed across the world, and we must be wary of generalizing the experiences of both colonizer and colonized women. India became known as “the jewel in the crown” of the British Empire. India became the archetypical colonized nation, and one whose freedom had particularly harsh consequences for women. How were women affected by imperialism?

Several European nations had tried to colonize India in prior centuries, but the dominant force that came to replace the weak Mughal Empire by the mid-19th century was the East India Company, a private joint stock company chartered by Queen Elizabeth I.

One way the British justified their colonizing across the globe, but especially in India, was by propagating the idea that they were saving native women from oppression and subjugation that they suffered at the hands of native men. The British claimed that by converting native populations to Christianity, ending traditional practices and teaching them the British way of life, they would drastically improve the lives of women. While many of these laws may seem progressive, they fed into the British colonial propaganda that Indians were evil savages and that colonialism was necessary to civilize them and save their souls. Thus, British officials and missionaries purposefully exaggerated the purpose and prevalence of such traditions for their own political ends. In India, for example, the British emphasized certain practices, including child marriage and sati as examples of these barbaric patriarchal traditions. Sati refers to the act of a widow voluntarily (or not, as the British claimed) throwing herself onto her late husband’s funeral pyre, being cremated alongside him. Sati was not widely practiced across India or condoned by all Hindus, but the British exaggerated its prominence and passed laws banning the practice in an attempt to prove their defense of native women. They also passed laws against child marriage and raised the age of consent in India from 12 to 16. In South India, the British also put an end to the devadasi tradition, in which young girls were donated to a temple to serve as servants of the Goddess, although often ended up serving as prostitutes for the priests and men of their villages.

The British ignored the hypocrisy of such laws. In Victorian Britain, laws such as the Contagious Diseases Act (which was also passed in India) demonized prostitutes and blamed women for the prevalence of sexually-transmitted diseases amongst British soldiers across the globe. Working-class British girls were forced to work from the age of seven or eight, or face life in the poor house.

The lives of women under imperialism differed across the world, and we must be wary of generalizing the experiences of both colonizer and colonized women. India became known as “the jewel in the crown” of the British Empire. India became the archetypical colonized nation, and one whose freedom had particularly harsh consequences for women. How were women affected by imperialism?

Several European nations had tried to colonize India in prior centuries, but the dominant force that came to replace the weak Mughal Empire by the mid-19th century was the East India Company, a private joint stock company chartered by Queen Elizabeth I.

One way the British justified their colonizing across the globe, but especially in India, was by propagating the idea that they were saving native women from oppression and subjugation that they suffered at the hands of native men. The British claimed that by converting native populations to Christianity, ending traditional practices and teaching them the British way of life, they would drastically improve the lives of women. While many of these laws may seem progressive, they fed into the British colonial propaganda that Indians were evil savages and that colonialism was necessary to civilize them and save their souls. Thus, British officials and missionaries purposefully exaggerated the purpose and prevalence of such traditions for their own political ends. In India, for example, the British emphasized certain practices, including child marriage and sati as examples of these barbaric patriarchal traditions. Sati refers to the act of a widow voluntarily (or not, as the British claimed) throwing herself onto her late husband’s funeral pyre, being cremated alongside him. Sati was not widely practiced across India or condoned by all Hindus, but the British exaggerated its prominence and passed laws banning the practice in an attempt to prove their defense of native women. They also passed laws against child marriage and raised the age of consent in India from 12 to 16. In South India, the British also put an end to the devadasi tradition, in which young girls were donated to a temple to serve as servants of the Goddess, although often ended up serving as prostitutes for the priests and men of their villages.

The British ignored the hypocrisy of such laws. In Victorian Britain, laws such as the Contagious Diseases Act (which was also passed in India) demonized prostitutes and blamed women for the prevalence of sexually-transmitted diseases amongst British soldiers across the globe. Working-class British girls were forced to work from the age of seven or eight, or face life in the poor house.

Queen Victoria, Wikimedia Commons

Queen Victoria, Wikimedia Commons

Upper class women were encouraged to serve only as mothers and wives and were discouraged from receiving an education beyond Bible study. While waging wars in the name of protecting Indian women, Britain attacked suffragettes and force fed them in British prisons for daring to ask for the right to vote. British women were considered property of their husbands and had limited legal rights of any kind, including custody of their children.

Even as they were attempting to ‘uplift’ and ‘liberate’ Hindu and Muslim women in India, British women felt little control or power over their own lives. This is ironic because one of the most powerful people in the world, Queen Victoria, sat on the throne of England between 1837-1901, for 63 years!

By 1877, Queen Victoria became Empress of India, sending a clear message to the world that British women had a key part to play in the expansion of the British Empire, the empire upon which the sun never set!

Even as they were attempting to ‘uplift’ and ‘liberate’ Hindu and Muslim women in India, British women felt little control or power over their own lives. This is ironic because one of the most powerful people in the world, Queen Victoria, sat on the throne of England between 1837-1901, for 63 years!

By 1877, Queen Victoria became Empress of India, sending a clear message to the world that British women had a key part to play in the expansion of the British Empire, the empire upon which the sun never set!

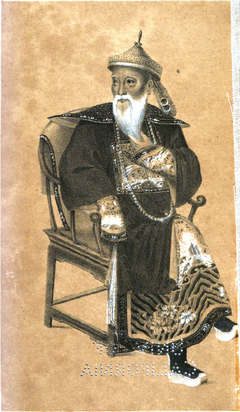

Lin Zexu, Wikimedia Commons

Lin Zexu, Wikimedia Commons

Imperialism in China

The British also had their eyes on carving up China, and they intended to use India to accomplish that goal. China remained untouched by imperialism. The Chinese had a vast market for Industrial goods and tea that the British economy desired. The Chinese were largely self-sufficient, forcing foreign nations to come to them for trade and doing little to engage beyond their borders. This balance of trade led to Britain pumping opium from India into China through the open port in Canton. The Chinese population grew increasingly addicted to opium, and Chinese authorities were frustrated with Britain for their illegal smuggling. In 1839, the emperor's son died of an opium overdose. He sent commissioner Lin Zexu’s to Canton to negotiate with the British East India trading company. He wrote a pleading letter to Queen Victoria, “By what right do they then in return use the poisonous drug to injure the Chinese people? … Let us ask, where is your conscience? I have heard that the smoking of opium is very strictly forbidden by your country; that is because the harm caused by opium is clearly understood. Since it is not permitted to do harm to your own country, then even less should you let it be passed on to the harm of other countries -- how much less to China!”

It is unclear whether Queen Victoria ever read this letter. The Chinese lost were forced to sign an unequal treaty. Britain was joined by other imperial nations and the conflict had an even more devastating impact on the Chinese.

Europeans who traveled to China were often single men who had left families behind. European women who were there were generally missionary wives coming to spread Christianity. Missionary societies set up schools for young British women to provide education to the local Chinese women. To Europeans, Confusion ideals that permeated Chinese society were oppressive.They began converting those values to Christianity in hopes of “civilizing” the Chinese. The education the British provided reinforced gender divisions and was heavily influenced by Victorian ideals back in Britain.

The British also had their eyes on carving up China, and they intended to use India to accomplish that goal. China remained untouched by imperialism. The Chinese had a vast market for Industrial goods and tea that the British economy desired. The Chinese were largely self-sufficient, forcing foreign nations to come to them for trade and doing little to engage beyond their borders. This balance of trade led to Britain pumping opium from India into China through the open port in Canton. The Chinese population grew increasingly addicted to opium, and Chinese authorities were frustrated with Britain for their illegal smuggling. In 1839, the emperor's son died of an opium overdose. He sent commissioner Lin Zexu’s to Canton to negotiate with the British East India trading company. He wrote a pleading letter to Queen Victoria, “By what right do they then in return use the poisonous drug to injure the Chinese people? … Let us ask, where is your conscience? I have heard that the smoking of opium is very strictly forbidden by your country; that is because the harm caused by opium is clearly understood. Since it is not permitted to do harm to your own country, then even less should you let it be passed on to the harm of other countries -- how much less to China!”

It is unclear whether Queen Victoria ever read this letter. The Chinese lost were forced to sign an unequal treaty. Britain was joined by other imperial nations and the conflict had an even more devastating impact on the Chinese.

Europeans who traveled to China were often single men who had left families behind. European women who were there were generally missionary wives coming to spread Christianity. Missionary societies set up schools for young British women to provide education to the local Chinese women. To Europeans, Confusion ideals that permeated Chinese society were oppressive.They began converting those values to Christianity in hopes of “civilizing” the Chinese. The education the British provided reinforced gender divisions and was heavily influenced by Victorian ideals back in Britain.

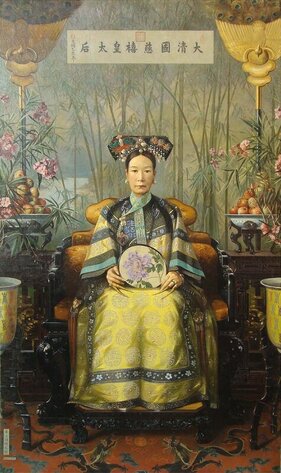

Empress Cixi, Wikimedia Commons

Empress Cixi, Wikimedia Commons

In the new British colony of Hong Kong, one of the major goals was to abolish the Mui Tsai system, which the British saw as a form of slavery that had supposedly been abolished throughout the empire. Mui tsai translates to “little sisters.” These little sisters were bondservants from poor families who were sold by their parents to richer homes where they worked their entire lives. Sometimes, they were loved like sisters, but at other times, they were taken advantage of and neglected. Sexual abuse was common. By adulthood the little sisters would sometimes be married off to poor men or sold by their new owners into prostitution.

The British had promised elites they wouldn’t interfere with traditions in Hong Kong, so authorities were reluctant to do anything about this sister tradition. The main argument in favor of this system was the well- established practice of female infanticide, or the killing of female babies. The Mui Tsai system at least ensured female babies survived to adulthood. British women and a few Chinese converts were appalled and began campaigning against the practice in the 1870s. Often, when white women try to “save” other women, they unintentionally misinterpret different cultures. There are also layers of unconscious racism and belittling present in their writings. Unfortunately, they rarely saw how poverty was a root cause of many of the issues that faced women.

Imperialism in China helped create the rise and fall of China’s second Empress, the last of the Chinese empire. Cixi came to power as the favored concubine of the emperor. When he died in 1861, Cixi's five-year-old son was his only male heir and became the emperor, making her regent as the “empress dowager.” Her son ruled independently for only two years before he died and Cixi became regent again for her three-year-old nephew.

The British had promised elites they wouldn’t interfere with traditions in Hong Kong, so authorities were reluctant to do anything about this sister tradition. The main argument in favor of this system was the well- established practice of female infanticide, or the killing of female babies. The Mui Tsai system at least ensured female babies survived to adulthood. British women and a few Chinese converts were appalled and began campaigning against the practice in the 1870s. Often, when white women try to “save” other women, they unintentionally misinterpret different cultures. There are also layers of unconscious racism and belittling present in their writings. Unfortunately, they rarely saw how poverty was a root cause of many of the issues that faced women.

Imperialism in China helped create the rise and fall of China’s second Empress, the last of the Chinese empire. Cixi came to power as the favored concubine of the emperor. When he died in 1861, Cixi's five-year-old son was his only male heir and became the emperor, making her regent as the “empress dowager.” Her son ruled independently for only two years before he died and Cixi became regent again for her three-year-old nephew.

Red Lanterns, Wikimedia Commons

Red Lanterns, Wikimedia Commons

Like every other powerful female empress and regent of China, Cixi was mired in controversy. She was described by some as the wicked witch of the east, murdering and whoring to keep her power. But most modern scholars see her as a complicated woman who had to navigate the challenges of female power while the empire was being attacked by imperial nations. Missionaries in China stood out and seemed to be everywhere. Some laws and taxes didn’t apply to them, which created animosity. They preached fundamentalist Christianity to a mostly hostile Chinese population. Their own records show that after 35 years they had secured only 13,000 converts. With so much tension, when the young emperor defied Cixi to introduce some ill-advised reforms; she quickly deposed him and, with the support of elites, took power.

In 1900, rebels known as “Boxers” murdered two German priests. Queen Victoria’s son-in-law Kaiser Wilhelm II, sent German troops to China, which exacerbated the problem. Boxers began rebelling against European imperial influence in China in a widespread movement. It began in rural areas and gradually moved toward trading capitals. Girls who joined the movement were called “Shining Red Lanterns” because of the bright red outfits that they wore. They trained at night to avoid being seen and sang songs against missionary imperialism. One went, “Learn to be a Boxer, Study Red Lantern. Kill all the foreign devils and make churches burn.”

Christian families in China were murdered as the Boxers swept through the countryside. Western armies moved quickly to defend the Europeans trapped in China. At first, Cixi sent the Chinese armies to fight the Boxers. When they closed in on Westerners in Peking, she switched sides, incorporating the Boxers into the armed forces. Eight imperial nations held out against the Chinese siege for two months until eventually they were reinforced. They swept to the Capital, raping Chinese women as they went. Cixi fled the palace disguised as a peasant with bullets flying around her. She was forced to accept humiliating terms that divided China into Spheres of Influence between imperial nations. She died of a stroke in 1908, claiming at the end of her life that she had never had a day without anxiety. She ruled China for almost 50 years, a formidable woman whose skills held together a bankrupt and declining empire. With her passing, imperial China fell apart.

In 1900, rebels known as “Boxers” murdered two German priests. Queen Victoria’s son-in-law Kaiser Wilhelm II, sent German troops to China, which exacerbated the problem. Boxers began rebelling against European imperial influence in China in a widespread movement. It began in rural areas and gradually moved toward trading capitals. Girls who joined the movement were called “Shining Red Lanterns” because of the bright red outfits that they wore. They trained at night to avoid being seen and sang songs against missionary imperialism. One went, “Learn to be a Boxer, Study Red Lantern. Kill all the foreign devils and make churches burn.”

Christian families in China were murdered as the Boxers swept through the countryside. Western armies moved quickly to defend the Europeans trapped in China. At first, Cixi sent the Chinese armies to fight the Boxers. When they closed in on Westerners in Peking, she switched sides, incorporating the Boxers into the armed forces. Eight imperial nations held out against the Chinese siege for two months until eventually they were reinforced. They swept to the Capital, raping Chinese women as they went. Cixi fled the palace disguised as a peasant with bullets flying around her. She was forced to accept humiliating terms that divided China into Spheres of Influence between imperial nations. She died of a stroke in 1908, claiming at the end of her life that she had never had a day without anxiety. She ruled China for almost 50 years, a formidable woman whose skills held together a bankrupt and declining empire. With her passing, imperial China fell apart.

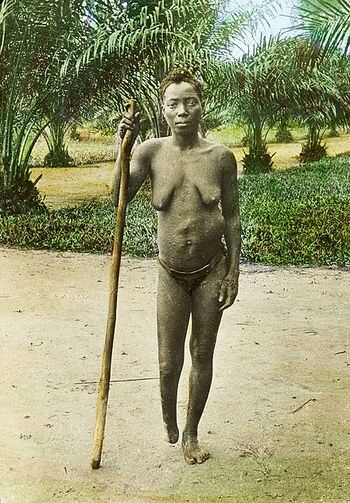

Maimed Woman in Congo, Wikimedia Commons

Maimed Woman in Congo, Wikimedia Commons

Imperialism in Africa

In 1884, not a single African leader was invited to a conference in Berlin where Europeans decided how to divide Africa between them and draw a new map of the continent. The contemporary map of Africa is still very similar to the colonial map of 1914. Only two of the delegates had even been to the continent, and none of them were women. What could possibly go wrong?

In search of raw materials which could fuel industrializing Europe, Britain and France in particular sought to control labor and land across much of Sub Saharan Africa. This had long- term environmental impacts, all the while massacring African people.

In West Africa, women farmed their own fields, participated in local trade and markets,, had economic independence, and had status as mothers and senior wives. Colonialists did not respect these gendered rights. . Under colonial rule, African men were forced into wage labor or cash-crop agriculture. Men and women began to live separate lives and develop different cultures, men working for a wage, women for sustenance. Women became heads of households.

Perhaps the most gruesome example of European treatment of African people was Queen Victoria’s cousin, King Leopold II of Belgium’s, treatment of the Congolese in the country he claimed as his personal possession: now known as the Democratic Republic of Congo. He used slave labor to extract rubber and other resources from the Congo. People who did not produce enough rubber were mutilated or killed. An estimated 10 million Congolese perished under his rule of the Congo Free State, which lasted from 1885-1908.

George Washington Williams, an African American journalist, writer, and member of the Ohio House of Assembly visited the Free State in the 1880s and also documented the abuses in an open letter to Leopold in 1890 which helped coin the term “crime against humanity.” Alice Seeley Harris, an English missionary and documentary photographer in the early 1900s took photos to document the atrocities. She sent her photos to anti-slavery publications. The political fall out resulted in Leopold relinquishing personal control over the situation.

In 1884, not a single African leader was invited to a conference in Berlin where Europeans decided how to divide Africa between them and draw a new map of the continent. The contemporary map of Africa is still very similar to the colonial map of 1914. Only two of the delegates had even been to the continent, and none of them were women. What could possibly go wrong?

In search of raw materials which could fuel industrializing Europe, Britain and France in particular sought to control labor and land across much of Sub Saharan Africa. This had long- term environmental impacts, all the while massacring African people.

In West Africa, women farmed their own fields, participated in local trade and markets,, had economic independence, and had status as mothers and senior wives. Colonialists did not respect these gendered rights. . Under colonial rule, African men were forced into wage labor or cash-crop agriculture. Men and women began to live separate lives and develop different cultures, men working for a wage, women for sustenance. Women became heads of households.

Perhaps the most gruesome example of European treatment of African people was Queen Victoria’s cousin, King Leopold II of Belgium’s, treatment of the Congolese in the country he claimed as his personal possession: now known as the Democratic Republic of Congo. He used slave labor to extract rubber and other resources from the Congo. People who did not produce enough rubber were mutilated or killed. An estimated 10 million Congolese perished under his rule of the Congo Free State, which lasted from 1885-1908.

George Washington Williams, an African American journalist, writer, and member of the Ohio House of Assembly visited the Free State in the 1880s and also documented the abuses in an open letter to Leopold in 1890 which helped coin the term “crime against humanity.” Alice Seeley Harris, an English missionary and documentary photographer in the early 1900s took photos to document the atrocities. She sent her photos to anti-slavery publications. The political fall out resulted in Leopold relinquishing personal control over the situation.

Missionaries in India

Women played a key role in the colonization in practical ways as missionaries and wives of merchants, mercenaries and civil servants. In India, in 1911, there were 1,236 European women in religious work throughout the country, compared to 1,943 men.

After the completion of the Suez Canal in 1869, an increase in Western women migrants and visitors to the subcontinent changed the nature of colonization, as more white male colonizers took fewer local indigenous women as wives and as more white women entered into the private domestic sphere as mistresses of native servants and as missionaries/teachers in the Indian spaces. This may have led to an increase in racial tension, as the boundary between colonizers and colonizers hardened. As in other colonial contexts, white imperialists’ racist fears were fueled by worries about miscegenation and the collapse of racial hierarchies in governance, commerce, and social status. White supremacists needed to maintain the false notion of racial superiority to maintain the social, political, and economic stratification that imperialism required.

British women often promoted and perpetuated imperialist propaganda that stated Indian women needed their help and liberation. Such women mobilized resources and networks to raise funds and spread literature about the benefits of expanding their empire. They also gave special lectures on the “oppressed women of India” in England to concerned subjects of the Empire.

Women played a key role in the colonization in practical ways as missionaries and wives of merchants, mercenaries and civil servants. In India, in 1911, there were 1,236 European women in religious work throughout the country, compared to 1,943 men.

After the completion of the Suez Canal in 1869, an increase in Western women migrants and visitors to the subcontinent changed the nature of colonization, as more white male colonizers took fewer local indigenous women as wives and as more white women entered into the private domestic sphere as mistresses of native servants and as missionaries/teachers in the Indian spaces. This may have led to an increase in racial tension, as the boundary between colonizers and colonizers hardened. As in other colonial contexts, white imperialists’ racist fears were fueled by worries about miscegenation and the collapse of racial hierarchies in governance, commerce, and social status. White supremacists needed to maintain the false notion of racial superiority to maintain the social, political, and economic stratification that imperialism required.

British women often promoted and perpetuated imperialist propaganda that stated Indian women needed their help and liberation. Such women mobilized resources and networks to raise funds and spread literature about the benefits of expanding their empire. They also gave special lectures on the “oppressed women of India” in England to concerned subjects of the Empire.

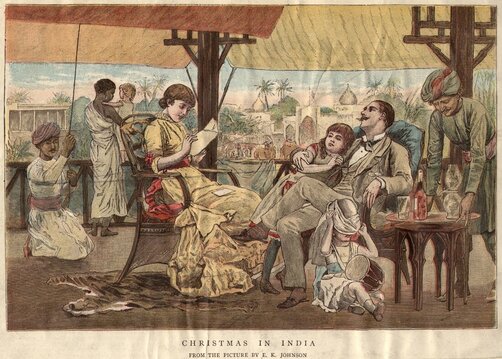

Notice Indian woman caring for the British baby in the background, New York Times

Notice Indian woman caring for the British baby in the background, New York Times

British women also traveled abroad in limited numbers to perform social work in India. Although initially, many went to India to accompany their husbands who were posted overseas, increasingly, British women went independently in the late 19th and early 20th century to work as nurses, teachers, social workers, or missionaries.

These women often held cultural and racial prejudices against the people of India and devoted themselves not only to evangelizing, converting, and civilizing native women, but also to westernizing Indian women by encouraging them to dress, speak, cook, eat, keep house, and carry themselves like ‘proper’ Victorian ladies. Some missionaries held motherhood camps so Indians could learn to bathe, feed, and diaper their babies like British mothers did.

British Women had limited access to the public sphere where men held control of commerce, governance, and formal education of native Indians. Most of their contact with native people was with servants who raised their children, cleaned their houses, and cooked their meals. Religious prejudices that deemed Islam and Hinduism as inferior faiths also caused the British to be less tolerant. They rarely learned Indian languages, went into Indian spaces such as markets, mosques, temples, weddings or festivals, or befriended native people.

Victorian women in India were held to high standards by the social rules of etiquette and the cultural norm of the day. Despite oppressive heat and humidity, British citizens were expected to dress formally and wear restricting corsets and heavy dresses that made the heat and humidity of India unbearable.

Many journals and letters from British women in this period were full of resentment and hostility towards a foreign and strange country, its people, customs, and culture. Often British women describe India as a dangerous country and its people as alien and incomprehensible.

Even women who tried their best to improve the lot of Indian women were often conservative in their approach to imperialism. For example, Josephine Butler, who worked tirelessly to repeal the Contagious Diseases Act in India and fight for women’s suffrage and education, did not join her friends in speaking out against British imperialism. She wrote that because of the work Britain had undertaken in making slavery illegal, "[w]ith all her faults, looked at from God's point of view, England is the best, and the least guilty of the nations.”

These women often held cultural and racial prejudices against the people of India and devoted themselves not only to evangelizing, converting, and civilizing native women, but also to westernizing Indian women by encouraging them to dress, speak, cook, eat, keep house, and carry themselves like ‘proper’ Victorian ladies. Some missionaries held motherhood camps so Indians could learn to bathe, feed, and diaper their babies like British mothers did.

British Women had limited access to the public sphere where men held control of commerce, governance, and formal education of native Indians. Most of their contact with native people was with servants who raised their children, cleaned their houses, and cooked their meals. Religious prejudices that deemed Islam and Hinduism as inferior faiths also caused the British to be less tolerant. They rarely learned Indian languages, went into Indian spaces such as markets, mosques, temples, weddings or festivals, or befriended native people.

Victorian women in India were held to high standards by the social rules of etiquette and the cultural norm of the day. Despite oppressive heat and humidity, British citizens were expected to dress formally and wear restricting corsets and heavy dresses that made the heat and humidity of India unbearable.

Many journals and letters from British women in this period were full of resentment and hostility towards a foreign and strange country, its people, customs, and culture. Often British women describe India as a dangerous country and its people as alien and incomprehensible.

Even women who tried their best to improve the lot of Indian women were often conservative in their approach to imperialism. For example, Josephine Butler, who worked tirelessly to repeal the Contagious Diseases Act in India and fight for women’s suffrage and education, did not join her friends in speaking out against British imperialism. She wrote that because of the work Britain had undertaken in making slavery illegal, "[w]ith all her faults, looked at from God's point of view, England is the best, and the least guilty of the nations.”

Jind Kaur, Wikimedia Commons

Jind Kaur, Wikimedia Commons

Active Participants

While colonialism subordinated all colonized women, the latter experienced colonialism in a variety of ways in part according to their class and status position. Some colonized women were active participants in imperialism as well as being subject to exploitation by colonial regimes of power. At other times, women were collaborators or beneficiaries. Some scholars have noted that elite women in colonial contexts sometimes benefitted from new educational models that promoted literacy, collectivization, and engagement with men. Women were often able to use their new skills to write petitions, create journals, publish opinions, and challenge authorities, both native and foreign. Elite colonial women sometimes took opportunities afforded to them by foreign intervention to organize political committees, social affinity groups, and/or auxiliaries of male organizations. Even though they could not vote or run for office, they could mobilize, organize, and educate one another as they sought solidarity and influence in their respective arenas. For many traditional women, the experience of having a voice in the public sphere, where male power was consolidated in commerce and formal politics, was revolutionary.

In India and Britain, women played a part in the nationalist movement and fought alongside their male counterparts for India’s freedom. From the earliest days of imperialism, Indian women such as Gulab Kaur led armies against invading forces. Jind Kaur, mother of the last Sikh emperor, became so troublesome for the British that they had her imprisoned. Her granddaughter Sophia Duleep Singh, who despite being raised in Britain at the court of Queen Victoria, spent her life fighting for Indian independence and the rights of women both in Britain and in India. In India, women such as Sarojini Naidu and Ismat Chughtai wrote pamphlets and poems advocating for an end to British rule. Others, such as Ruttie Jinnah and Kasturba Gandhi took to the political sphere to influence the eventual freedom that their husbands would get all the credit for.

Lakshmibai, the Rani of Jhansi, was a leader in the Indian Rebellion of 1857. In just her twenties, she was a widow to the late ruler and used her position to support the rebellion. The British overlords decided to annex her state and attempted to bribe her to leave with a chest of money. She joined and then led the Indian rebels. Lakshmibai's troops massacred a garrison of British soldiers, their wives, and children.

She fought for two years dressed as a man and wielding a saber, but her rebellion was defeated in 1858. She died in battle. After her death, her body was burned in a huge ceremony, and she is remembered as a hero of India.

While colonialism subordinated all colonized women, the latter experienced colonialism in a variety of ways in part according to their class and status position. Some colonized women were active participants in imperialism as well as being subject to exploitation by colonial regimes of power. At other times, women were collaborators or beneficiaries. Some scholars have noted that elite women in colonial contexts sometimes benefitted from new educational models that promoted literacy, collectivization, and engagement with men. Women were often able to use their new skills to write petitions, create journals, publish opinions, and challenge authorities, both native and foreign. Elite colonial women sometimes took opportunities afforded to them by foreign intervention to organize political committees, social affinity groups, and/or auxiliaries of male organizations. Even though they could not vote or run for office, they could mobilize, organize, and educate one another as they sought solidarity and influence in their respective arenas. For many traditional women, the experience of having a voice in the public sphere, where male power was consolidated in commerce and formal politics, was revolutionary.

In India and Britain, women played a part in the nationalist movement and fought alongside their male counterparts for India’s freedom. From the earliest days of imperialism, Indian women such as Gulab Kaur led armies against invading forces. Jind Kaur, mother of the last Sikh emperor, became so troublesome for the British that they had her imprisoned. Her granddaughter Sophia Duleep Singh, who despite being raised in Britain at the court of Queen Victoria, spent her life fighting for Indian independence and the rights of women both in Britain and in India. In India, women such as Sarojini Naidu and Ismat Chughtai wrote pamphlets and poems advocating for an end to British rule. Others, such as Ruttie Jinnah and Kasturba Gandhi took to the political sphere to influence the eventual freedom that their husbands would get all the credit for.

Lakshmibai, the Rani of Jhansi, was a leader in the Indian Rebellion of 1857. In just her twenties, she was a widow to the late ruler and used her position to support the rebellion. The British overlords decided to annex her state and attempted to bribe her to leave with a chest of money. She joined and then led the Indian rebels. Lakshmibai's troops massacred a garrison of British soldiers, their wives, and children.

She fought for two years dressed as a man and wielding a saber, but her rebellion was defeated in 1858. She died in battle. After her death, her body was burned in a huge ceremony, and she is remembered as a hero of India.

Some white British women traveled to India to provide support and solidarity to those fighting for independence. Perhaps the most well known of these was Annie Besant, who helped launch the Home Rule League to campaign for democracy in India and dominion status within the British Empire. This led to her election as president of the Indian National Congress in late 1917. She was not the only British woman to side with India against the Empire. Freida Bedi moved to India with her Indian husband and dedicated her life to writing and protesting against British rule, even being arrested several times for anti-English agitation. Madeline Slade, who became known as Merabehn, left her home in England to live and work alongside Mahatma Gandhi and has since been lost in his shadow along with myriad other female freedom fighters.

Independence

Despite the best efforts of those fighting for Home Rule, India did not gain its independence until 1947. The Partition of India and creation of Pakistan in that year resulted in the colony being divided and the population of India split into two countries, organized broadly into Hindu and Muslim groups.

This resulted in one of the biggest forced migrations in human history, with more than 10 million people moving between India and Pakistan. In this process, 1.5 million people died from inter-religious violence, disease, starvation, and exhaustion. Women bore the brunt of partition. Tens of thousands of women from all religious communities were kidnapped, murdered, mutilated, and raped by “enemy” communities. Many, including children, were forced into marriages and many committed suicide rather than face the prospect of rape or mutilation at the hands of men. The British launched a campaign to “recover” these stolen women, but many did not wish to return to communities that were likely to reject them if their honor had been compromised or if they had made a new home in their new country. Today, the plight of South Asian women during Partition remains virtually unknown beyond the Indian subcontinent, despite being one of the darkest examples of women’s lives under imperialism.

By the end of this era, so much remained in question. How would women in these colonial societies respond? And what role would they play in colonial resistance?

Independence

Despite the best efforts of those fighting for Home Rule, India did not gain its independence until 1947. The Partition of India and creation of Pakistan in that year resulted in the colony being divided and the population of India split into two countries, organized broadly into Hindu and Muslim groups.

This resulted in one of the biggest forced migrations in human history, with more than 10 million people moving between India and Pakistan. In this process, 1.5 million people died from inter-religious violence, disease, starvation, and exhaustion. Women bore the brunt of partition. Tens of thousands of women from all religious communities were kidnapped, murdered, mutilated, and raped by “enemy” communities. Many, including children, were forced into marriages and many committed suicide rather than face the prospect of rape or mutilation at the hands of men. The British launched a campaign to “recover” these stolen women, but many did not wish to return to communities that were likely to reject them if their honor had been compromised or if they had made a new home in their new country. Today, the plight of South Asian women during Partition remains virtually unknown beyond the Indian subcontinent, despite being one of the darkest examples of women’s lives under imperialism.

By the end of this era, so much remained in question. How would women in these colonial societies respond? And what role would they play in colonial resistance?

Draw your own conclusions

Lesson Plans from Other Organizations

- This website, Women in World History has primary source based lesson plans on women's history in a whole range of topics. Some are free while others have a cost.

- The Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media has produced recommendations for teaching women's history with primary sources and provided a collection of sources for world history. Check them out!

- The Stanford History Education Group has a number of lesson plans about women in World History.

Fredercick Forbes: Description Of Amazon People

Frederick Forbes traveled to West Africa as an officer for the British Royal Navy and published his journal in 1851. He was sent to the kingdom to convince the King to suppress Dahomey's involvement with the slave trade. As Britain had banned the slave trade, Forbes worked to bring to the public's attention the slave hunts practiced by the Dahomey. This is one of his sketches of a Mino or Amazon warrior next to his description of the Amazons.

The amazons are not supposed to marry, and, by their own statement, they have changed their sex. "We are men," say they, " not women." All dress alike, diet alike, and male and female emulate each other: what the males do, the amazons will endeavour to surpass. They all take great care of their arms, polish the bar- rels, and, except when on duty, keep them in covers. There is no duty at the palace, except when the king is in public, and then a guard of amazons protect the royal person, and, on review, he is guarded by the males ; but outside the palace is always a strong detachment of males ready for service. The amazons are in barracks within the palace enclosure, and under the care of the eunuchs and the camboodee or treasurer. In every action (with males and females), there is some reference to cutting off heads.

[T]he palace, or the grand Fetish houses…The royal wives and their slaves, I presume from the jealousy of their despotic lord, are considered too sacred for man to gaze upon ; and on meeting any of these sable beauties on the road, a bell warns the wayfarer to turn off, or stand against a wall while they pass. The king has thousands of wives… If one of the wives of the king, or a high officer's, commits adultery, the culprits are summarily beheaded ; and the skull of one of the Agaou's wives is at present exposed in the square of the palace of Agrimgomeh, in Abomey. But if adultery be committed by parties of lower rank, they are sold Marriages. If a uiau scduccs a girl, the law obliges marriage, and the payment of eighty heads of cowries to the parent or master, on pain of becoming himself a slave. In marriage there is no ceremony, except where the king confers the wife, in which instance the maiden presents her future lord with a glass of rum.

Forbes, Frederick. “Seh-Dong-Hong-Beh, leader of the en:Dahomey Amazons.” Dahomey of the Dahomans. 1851. (being the journals of two missions to the king of Dahomey, and residence at his capital), 23-24. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/dahomeydahomansb00forb/page/n41/mode/2up.

Questions:

The amazons are not supposed to marry, and, by their own statement, they have changed their sex. "We are men," say they, " not women." All dress alike, diet alike, and male and female emulate each other: what the males do, the amazons will endeavour to surpass. They all take great care of their arms, polish the bar- rels, and, except when on duty, keep them in covers. There is no duty at the palace, except when the king is in public, and then a guard of amazons protect the royal person, and, on review, he is guarded by the males ; but outside the palace is always a strong detachment of males ready for service. The amazons are in barracks within the palace enclosure, and under the care of the eunuchs and the camboodee or treasurer. In every action (with males and females), there is some reference to cutting off heads.

[T]he palace, or the grand Fetish houses…The royal wives and their slaves, I presume from the jealousy of their despotic lord, are considered too sacred for man to gaze upon ; and on meeting any of these sable beauties on the road, a bell warns the wayfarer to turn off, or stand against a wall while they pass. The king has thousands of wives… If one of the wives of the king, or a high officer's, commits adultery, the culprits are summarily beheaded ; and the skull of one of the Agaou's wives is at present exposed in the square of the palace of Agrimgomeh, in Abomey. But if adultery be committed by parties of lower rank, they are sold Marriages. If a uiau scduccs a girl, the law obliges marriage, and the payment of eighty heads of cowries to the parent or master, on pain of becoming himself a slave. In marriage there is no ceremony, except where the king confers the wife, in which instance the maiden presents her future lord with a glass of rum.

Forbes, Frederick. “Seh-Dong-Hong-Beh, leader of the en:Dahomey Amazons.” Dahomey of the Dahomans. 1851. (being the journals of two missions to the king of Dahomey, and residence at his capital), 23-24. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/dahomeydahomansb00forb/page/n41/mode/2up.

Questions:

- How does he describe the Amazon warrior women?

- Why might this British officer have a different perspective on the Amazons than the Dahomey themselves? How might that impact this account?

Alfred Skertchly: Dahomey As It Is

Alfred Skertchly left England in 1871 to collect zoological specimens West Coast of Africa. He traveled to Abomey, the capital of Dahomey, to train the King on the use of new weapons. He expected to stay for eight days but was held as an unwilling, yet well treated guest. This is his account of the Amazons.

One of the most singular institutions of Dahomey is the female army, or Amazons, as they have been called. When these soldieresses were first introduced into the country is unknown…

Who has not heard of the ferocious actions of a drunken woman; and do not the daily papers bear witness to the fact that, once roused, a woman will perpetrate far greater cruelty than a man? Did not the petroleuses of Paris wander about like she-demons of the nether world? What spectacle is more calculated to inspire horror than a savage and brutal woman in a passion? and when we imagine such to be besprinkled with the blood of the slain, and perhaps carrying the gory head of some decapitated victim, one may cease to wonder at the dread with which these female warriors were, and still are, looked upon by the surrounding nations…

[I]t would… be a happy release from their relatives if all the old maids could be enlisted, and trained to vent their feline spite and mischief-making propensities on the enemies of the country, instead of their neighbours. At any rate, they would be removed out of the way of the sycophantic parasites, who invariably hover round them, should they be possessed of any property, in the hope of cajoling them out of it. Instances are not by any means rare, of females who have donned the soldier's uniform, and fought bravely side by side, not taking into consideration such heroines as Joan of Arc, Margaret of Anjou, Boadicea, and a host of others… As for physical endurance, do not scores of charwomen and laundresses drag out a life of literal slavery…

Nevertheless, there can be no doubt that the Amazonian army of Dahomey is one of the causes of its slow decadence… Dahomey will have to be classed among the nations that have been.

Skertchly, J. Alfred. “Dahomey as it Is.” London: Legare Street Press, 2021. First published in 1884 by Chapman and Hall, 454-459.

Questions:

One of the most singular institutions of Dahomey is the female army, or Amazons, as they have been called. When these soldieresses were first introduced into the country is unknown…

Who has not heard of the ferocious actions of a drunken woman; and do not the daily papers bear witness to the fact that, once roused, a woman will perpetrate far greater cruelty than a man? Did not the petroleuses of Paris wander about like she-demons of the nether world? What spectacle is more calculated to inspire horror than a savage and brutal woman in a passion? and when we imagine such to be besprinkled with the blood of the slain, and perhaps carrying the gory head of some decapitated victim, one may cease to wonder at the dread with which these female warriors were, and still are, looked upon by the surrounding nations…

[I]t would… be a happy release from their relatives if all the old maids could be enlisted, and trained to vent their feline spite and mischief-making propensities on the enemies of the country, instead of their neighbours. At any rate, they would be removed out of the way of the sycophantic parasites, who invariably hover round them, should they be possessed of any property, in the hope of cajoling them out of it. Instances are not by any means rare, of females who have donned the soldier's uniform, and fought bravely side by side, not taking into consideration such heroines as Joan of Arc, Margaret of Anjou, Boadicea, and a host of others… As for physical endurance, do not scores of charwomen and laundresses drag out a life of literal slavery…

Nevertheless, there can be no doubt that the Amazonian army of Dahomey is one of the causes of its slow decadence… Dahomey will have to be classed among the nations that have been.

Skertchly, J. Alfred. “Dahomey as it Is.” London: Legare Street Press, 2021. First published in 1884 by Chapman and Hall, 454-459.

Questions:

- Underline words used to describe the Amazon warriors. Overall, how would you say they are viewed?

- How might differences in culture impact his account?

- Were the Dahomey women powerful?

Mrs. Crane: Letter About The Empress

Imperial rulers of China lived inside the Forbidden City, a palace city used by the Emperors of China. The city was “forbidden” to almost all subjects. Beginning during the Ming dynasty, the Forbidden City became the location of the imperial court. The city created a literal wall between the rulers and the lay people, clouding them in mystery and misunderstanding. Nothing in the historical record tells us more about Mrs. Crane, the author of this document, but her position on the empress is clear.

The sense of justice shown by England in her protest against the murderous cruelty of that human vampire, the Dowager of China, should be followed by all civilized and Christian folk [e]ndorsing these lines: ‘Rebellion to tyrants, obedience to God.” The tree of liberty only grows when watered by the blood of tyrants, and who more worthy of death than she who has connived at and urged on the murdering of our dear missionaries?

Mrs. William Halsted Crane, “Career of Chinese Dowager Empress,” New York Times, Aug. 8, 1903, 6.

Questions:

The sense of justice shown by England in her protest against the murderous cruelty of that human vampire, the Dowager of China, should be followed by all civilized and Christian folk [e]ndorsing these lines: ‘Rebellion to tyrants, obedience to God.” The tree of liberty only grows when watered by the blood of tyrants, and who more worthy of death than she who has connived at and urged on the murdering of our dear missionaries?

Mrs. William Halsted Crane, “Career of Chinese Dowager Empress,” New York Times, Aug. 8, 1903, 6.

Questions:

- Who is the source of this document? Is she Chinese? How well is she likely to know the Empress?

- What does the tone of this excerpt say about how Empress Cixi was viewed by some foreign sources?

- Empress Cixi is often described as power hungry and manipulative. Looking further than just her description, how might these descriptives affect her legacy, as well as the perceptions of women in power?

Empress Cixi: Reform Edict Of The Qing Imperial Government Issued

In the wake of the Boxer Uprising (1899-1901) and the catastrophic foreign intervention that that movement precipitated, the imperial government reconsidered the need for fundamental reforms. Government reform had already been attempted, and rejected, in 1898 when Kang Youwei (1858-1927) and his colleagues temporarily ran the imperial government, with the support of the Guangxu Emperor (1871-1908, r. 1875-1908), until the Empress Dowager Cixi (1835-1908) ousted them.

Certain principles of morality (changqing) are immutable, whereas methods of governance (zhifa) have always been mutable. The Classic of Changes states that “when a measure has lost effective force, the time has come to change it.” And the Analects states that “the Shang and Zhou dynasties took away and added to the regulations of their predecessors, as can readily be known.”

… We have now received Her Majesty’s decree to devote ourselves fully to China’s revitalization, to suppress vigorously the use of the terms new and old, and to blend together the best of what is Chinese and what is foreign. The root of China’s weakness lies in harmful habits too firmly entrenched, in rules and regulations too minutely drawn, in the overabundance of inept and mediorìcre officials and in the paucity of truly outstanding ones, in petty bureaus who hide behind the written word and in clerks and yamen runners who use the written word as talismans to acquire personal fortunes, in the mountains of correspondence between government offices that have no relationship to reality, and in the seniority system and associated practices that block the way of men of real talent…

The first essential, even more important than devising new systems of governance (zhifa) is to secure men who govern well (zhi ren). Without new systems, the corrupted old system cannot be salvaged; without men of ability, even good systems cannot be made to succeed.

‘Reform Edict of the Qing Imperial Government’. Columbia University Press, 29 January 1901. http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/ps/cup/qing_reform_edict_1901.pdf.

Questions:

Certain principles of morality (changqing) are immutable, whereas methods of governance (zhifa) have always been mutable. The Classic of Changes states that “when a measure has lost effective force, the time has come to change it.” And the Analects states that “the Shang and Zhou dynasties took away and added to the regulations of their predecessors, as can readily be known.”

… We have now received Her Majesty’s decree to devote ourselves fully to China’s revitalization, to suppress vigorously the use of the terms new and old, and to blend together the best of what is Chinese and what is foreign. The root of China’s weakness lies in harmful habits too firmly entrenched, in rules and regulations too minutely drawn, in the overabundance of inept and mediorìcre officials and in the paucity of truly outstanding ones, in petty bureaus who hide behind the written word and in clerks and yamen runners who use the written word as talismans to acquire personal fortunes, in the mountains of correspondence between government offices that have no relationship to reality, and in the seniority system and associated practices that block the way of men of real talent…

The first essential, even more important than devising new systems of governance (zhifa) is to secure men who govern well (zhi ren). Without new systems, the corrupted old system cannot be salvaged; without men of ability, even good systems cannot be made to succeed.

‘Reform Edict of the Qing Imperial Government’. Columbia University Press, 29 January 1901. http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/ps/cup/qing_reform_edict_1901.pdf.

Questions:

- Who is the author of this document?

- What are the problems outlined in the royal edict?

- In the final paragraph, why do they need to “secure men who govern well”? What does this imply about the real power Cixi has?

- Based on this edict, what kind of ruler was Empress Cixi?

Princess Der Ling: Two Years In The Forbidden City

For two years, Princess Der Ling was the favorite lady-in-waiting to the Empress Dowager Cixi in the imperial palace in Beijing. This book provides a unique and surprisingly intimate portrait of the Dragon Lady, who ruled China for 47 years, and brought the country to the brink of destruction. Der Ling refers to the larger political context on many occasions. But the best parts of the book are the small details. What emerges is an intimate portrait of the life and personality of the Empress Dowager, and a sense of the inner workings of the highly secretive world of the imperial palace.

[A]ccording to the Manchu custom, the daughters of all Manchu officials of the second rank and above, after reaching the age of fourteen years, should go to the Palace, in order that the Emperor may select them for secondary wives if he so desires, and my father had other plans and ambitions for us. It was in this way that the late Empress Dowager was selected by the Emperor Hsien Feng…

"Her Majesty has sent me to meet you," and was very sweet and polite, and had beautiful manners; but was not very pretty. Then we heard a loud voice from the hall saying, "Tell them to come in at once”... Her Majesty stood up when she saw us and shook hands with us. She had a most fascinating smile and was very much surprised that we knew the Court etiquette so well. After she had greeted us, she said to my mother: "Yu tai tai (Lady Yu), you are a wonder the wayyou have brought your daughters up. They speak Chinese just as well as I do, although I know they have been abroad for so many years, and how is it that they have such beautiful manners?" "Their father was always very strict with them," my mother replied… Her Majesty asked all sorts of questions about our Paris gowns and said we must wear them all the time, as she had very little chance to see them at the Court…

When we commenced to eat, Her Majesty ordered the eunuchs to place plates for us and give us silver chopsticks, spoons, etc., and said: "I am sorry you have to eat standing, but I cannot break the law of our great ancestors. Even the Young Empress cannot sit in my presence. I am sure the foreigners must think we are barbarians to treat our Court ladies in this way and I don't wish them to know anything about our customs. You will see how differently I act in their presence, so that they cannot see my true self.”

…”Do you think they, the foreigners, really like me? I don't think so; on the contrary I know they haven't forgotten the Boxer Rising in Kwang Hsu's 26th year. I don't mind owning up that I like our old ways the best, and I don't see any reason why we should adopt the foreign style. Did any of the foreign ladies ever tell you that I am a fierce-looking old woman?" I was very much surprised that she should… ask me such questions during her meal. She looked quite serious and it seemed to me she was quite annoyed. I assured her that no one ever said anything about Her Majesty but nice things. The foreigners told me how nice she was, and how graceful, etc. This seemed to please her, and she smiled and said: "Of course they have to tell you that, just to make you feel happy by saying that your sovereign is perfect, but I know better. I can't worry too much, but I hate to see China in such a poor condition… While she was saying this I noticed her worried expression. I did not know what to say, but tried to comfort her by saying that that time will come, and we are all looking forward to it.

Der Ling. Two Years in the Forbidden City. Project Gutenberg. 1911

Questions:

[A]ccording to the Manchu custom, the daughters of all Manchu officials of the second rank and above, after reaching the age of fourteen years, should go to the Palace, in order that the Emperor may select them for secondary wives if he so desires, and my father had other plans and ambitions for us. It was in this way that the late Empress Dowager was selected by the Emperor Hsien Feng…

"Her Majesty has sent me to meet you," and was very sweet and polite, and had beautiful manners; but was not very pretty. Then we heard a loud voice from the hall saying, "Tell them to come in at once”... Her Majesty stood up when she saw us and shook hands with us. She had a most fascinating smile and was very much surprised that we knew the Court etiquette so well. After she had greeted us, she said to my mother: "Yu tai tai (Lady Yu), you are a wonder the wayyou have brought your daughters up. They speak Chinese just as well as I do, although I know they have been abroad for so many years, and how is it that they have such beautiful manners?" "Their father was always very strict with them," my mother replied… Her Majesty asked all sorts of questions about our Paris gowns and said we must wear them all the time, as she had very little chance to see them at the Court…

When we commenced to eat, Her Majesty ordered the eunuchs to place plates for us and give us silver chopsticks, spoons, etc., and said: "I am sorry you have to eat standing, but I cannot break the law of our great ancestors. Even the Young Empress cannot sit in my presence. I am sure the foreigners must think we are barbarians to treat our Court ladies in this way and I don't wish them to know anything about our customs. You will see how differently I act in their presence, so that they cannot see my true self.”

…”Do you think they, the foreigners, really like me? I don't think so; on the contrary I know they haven't forgotten the Boxer Rising in Kwang Hsu's 26th year. I don't mind owning up that I like our old ways the best, and I don't see any reason why we should adopt the foreign style. Did any of the foreign ladies ever tell you that I am a fierce-looking old woman?" I was very much surprised that she should… ask me such questions during her meal. She looked quite serious and it seemed to me she was quite annoyed. I assured her that no one ever said anything about Her Majesty but nice things. The foreigners told me how nice she was, and how graceful, etc. This seemed to please her, and she smiled and said: "Of course they have to tell you that, just to make you feel happy by saying that your sovereign is perfect, but I know better. I can't worry too much, but I hate to see China in such a poor condition… While she was saying this I noticed her worried expression. I did not know what to say, but tried to comfort her by saying that that time will come, and we are all looking forward to it.

Der Ling. Two Years in the Forbidden City. Project Gutenberg. 1911

Questions:

- Who is the source of this document? Is she Chinese? How well is she likely to know the Empress?

- What does the tone of this excerpt say about how Empress Cixi was viewed by some foreign sources?

- Based on this book, what kind of ruler was Empress Cixi?

oRal Histories: The Red Lanterns

The following are excerpts from oral histories gathered through Shandong University in Jinan, China. The oral histories were recorded beginning in the 1960s.

Girls who joined the Boxers were called ‘Shining Red Lanterns.’ They dressed all in red. In one hand they had a little red lantern and in the other a little red fan. They carried a basket in the crook of their arm. When bullets were shot at them they waved their fans and the bullets were caught in the basket. You couldn’t hit them!... In every village there were girls who studied the Shining Red Lantern. In my village there were eight or ten of them…There was a song then that went:

‘Learn to be a Boxer, study the Red Lantern, Kill all the foreign devils and make the churches burn.’ Miss Han [Han Guniang] was from Long’gu in Zhili [Hebei]...[she] came to Long[gu on the big hemp marketing day…in 1900. She was riding a big horse and a dozen or so followers came with her. They entered Long’gu blowing bugles and many people ran to watch her. Her followers came from all over Long’gu; there were several thousand of them…It was said she was a Shining Red Lantern. She was very skillful; she could fight with spears or a sword. When she rode on a bench, it would turn into a horse; if she rode a rope, it would change into a dragon; if she sat on a mat it would become a cloud and she could ride the cloud and fly away.

Chen, Janet Y, Pei-kai Cheng, Michael Elliot Lestz, and Jonathan D Spence. The Search for Modern China: A Documentary Collection. Third ed. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2014 (184-185).

Questions:

Girls who joined the Boxers were called ‘Shining Red Lanterns.’ They dressed all in red. In one hand they had a little red lantern and in the other a little red fan. They carried a basket in the crook of their arm. When bullets were shot at them they waved their fans and the bullets were caught in the basket. You couldn’t hit them!... In every village there were girls who studied the Shining Red Lantern. In my village there were eight or ten of them…There was a song then that went:

‘Learn to be a Boxer, study the Red Lantern, Kill all the foreign devils and make the churches burn.’ Miss Han [Han Guniang] was from Long’gu in Zhili [Hebei]...[she] came to Long[gu on the big hemp marketing day…in 1900. She was riding a big horse and a dozen or so followers came with her. They entered Long’gu blowing bugles and many people ran to watch her. Her followers came from all over Long’gu; there were several thousand of them…It was said she was a Shining Red Lantern. She was very skillful; she could fight with spears or a sword. When she rode on a bench, it would turn into a horse; if she rode a rope, it would change into a dragon; if she sat on a mat it would become a cloud and she could ride the cloud and fly away.

Chen, Janet Y, Pei-kai Cheng, Michael Elliot Lestz, and Jonathan D Spence. The Search for Modern China: A Documentary Collection. Third ed. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2014 (184-185).

Questions:

- According to these interviews, how did women support and lead in the Boxer Rebellion?

- Descriptions of the Red Lanterns sometimes describe them as having magical powers. Whether they really had these powers or not, what might the idea of these powers tell us about how people viewed the Red Lanterns?

Unknown: A Symbol Of Chinese Women

The red lantern of the Red Lanterns is a symbol of the militancy of Chinese women; the daughters of the Red Lantern are the vanguard of the opposition of Chinese women to imperialism! Mountains may be leveled and the seas may be emptied, but the red lantern of revolution will never be extinguished!

Quoted in Liu Rong and Xu Fen. 1975. “Hongdeng nu’er song” [In praise of the daughters of the Red Lantern]. Tianjin shiyuan xuebao [Tianjin Teachers College journal] No. 2:78-82, 77.

Questions:

Quoted in Liu Rong and Xu Fen. 1975. “Hongdeng nu’er song” [In praise of the daughters of the Red Lantern]. Tianjin shiyuan xuebao [Tianjin Teachers College journal] No. 2:78-82, 77.

Questions:

- How does this document portray the Red Lanterns?

- According to this document, how were women important to the Boxer Rebellion?

Empress Cixi: The Empress Dowager Calls For Reform

The Empress Dowager Cixi was officially the regent, or the person ruling on behalf of the Guangxu Emperor. In 1898, the young emperor was removed from power and Cixi was effectively the ruler of China for another decade. During the Boxer Rebellion, she supported the Boxers and saw their efforts as a way to remove foreigners from China. In January 1901, she issued an edict that called for government reform in the aftermath of the Boxer Rebellion.

It was only by an appeal to the Empress Dowager to resume the reins of power that the court was saved from immediate peril and the evil rooted out in a single day… We have now received Her Majesty’s decree to devote ourselves fully to China’s revitalization, to suppress vigorously the use of the terms new and old, and to blend together the best of what is Chinese and what is foreign. The root of China’s weakness lies in harmful habits too firmly entrenched, in rules and regulations too minutely drawn…To sum up, administrative methods and regulations must be revised and abuses eradicated. If regeneration is truly desired, there must be quiet and reasoned deliberation…

We therefore call upon the members of the Grand Council, the Grand Secretaries, the Six Boards and Nine ministries, our ministers abroad, and the governors-general and governors of the provinces to reflect carefully on our present sad state of affairs and to scrutinize Chinese and Western governmental systems…Duly weigh what should be kept and what abolished, what new methods should be adopted and what old ones retained. By every available means of knowledge and observation, seek out how to renew our national strength, how to produce men of real talent, how to expand state revenues and how to revitalize the military…Without new systems, the corrupted old system cannot be salvaged…

The Empress Dowager and we have long pondered these matters. Now things are at a crisis point where change must occur, to transform weakness into strength. Everything depends upon how the change is effected.

Reform Edict of the Qing Imperial Government, January 29, 1901. Selections from Asia for Educators, Columbia University, http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/ps/cup/qing_reform_edict_1901.pdf.

Questions:

It was only by an appeal to the Empress Dowager to resume the reins of power that the court was saved from immediate peril and the evil rooted out in a single day… We have now received Her Majesty’s decree to devote ourselves fully to China’s revitalization, to suppress vigorously the use of the terms new and old, and to blend together the best of what is Chinese and what is foreign. The root of China’s weakness lies in harmful habits too firmly entrenched, in rules and regulations too minutely drawn…To sum up, administrative methods and regulations must be revised and abuses eradicated. If regeneration is truly desired, there must be quiet and reasoned deliberation…

We therefore call upon the members of the Grand Council, the Grand Secretaries, the Six Boards and Nine ministries, our ministers abroad, and the governors-general and governors of the provinces to reflect carefully on our present sad state of affairs and to scrutinize Chinese and Western governmental systems…Duly weigh what should be kept and what abolished, what new methods should be adopted and what old ones retained. By every available means of knowledge and observation, seek out how to renew our national strength, how to produce men of real talent, how to expand state revenues and how to revitalize the military…Without new systems, the corrupted old system cannot be salvaged…

The Empress Dowager and we have long pondered these matters. Now things are at a crisis point where change must occur, to transform weakness into strength. Everything depends upon how the change is effected.

Reform Edict of the Qing Imperial Government, January 29, 1901. Selections from Asia for Educators, Columbia University, http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/ps/cup/qing_reform_edict_1901.pdf.

Questions:

- What role did the Empress Dowager Cixi play in the Boxer Rebellion?

- What methods did Empress Dowager Cixi use to address the Boxer Rebellion, according to this document?

Princess Der Ling: Two Years In The Forbidden City, Excerpt

For two years, Princess Der Ling was the favorite lady-in-waiting to the Empress Dowager Cixi in the imperial palace in Beijing. This book provides a unique and surprisingly intimate portrait of the Dragon Lady, who ruled China for 47 years, and brought the country to the brink of destruction. Der Ling refers to the larger political context on many occasions. But the best parts of the book are the small details. What emerges is an intimate portrait of the life and personality of the Empress Dowager, and a sense of the inner workings of the highly secretive world of the imperial palace.

When I informed Her Majesty of the arrival of the portrait she ordered that it should be brought into her bedroom immediately. She scrutinized it very carefully for a while, even touching the painting in her curiosity. Finally she burst out laughing and said: "What a funny painting this is, it looks as though it had been painted with oil." (Of course it was an oil painting.) "Such rough work I never saw in all my life. The picture itself is marvellously like you, and I do not hesitate to say that none of our Chinese painters could get the expression which appears on this picture. What a funny dress you are wearing in this picture. Why are your arms and neck all bare? I have heard that foreign ladies wear their dresses without sleeves and without collars, but I had no idea that it was so bad and ugly as the dress you are wearing here. I cannot imagine how you could do it. I should have thought you would have been ashamed to expose yourself in that manner. Don't wear any more such dresses, please. It has quite shocked me. What a funny kind of civilization this is to be sure. Is this dress only worn on certain occasions, or is it worn any time, even when gentlemen are present?" I explained to her that it was the usual evening dress for ladies and was worn at dinners, balls, receptions, etc. Her Majesty laughed and exclaimed: "This is getting worse and worse. Everything seems to go backwards in foreign countries. Here we don't even expose our wrists when in the company of gentlemen, but foreigners seem to have quite different ideas on the subject. The Emperor is always talking about reform, but if this is a sample we had much better remain as we are. Tell me, have you yet changed your opinion with regard to foreign customs? Don't you think that our own customs are much nicer?" Of course I was obliged to say "yes" seeing that she herself was so prejudiced.

Der Ling. Two Years in the Forbidden City. Project Gutenberg. 1911.

Questions:

When I informed Her Majesty of the arrival of the portrait she ordered that it should be brought into her bedroom immediately. She scrutinized it very carefully for a while, even touching the painting in her curiosity. Finally she burst out laughing and said: "What a funny painting this is, it looks as though it had been painted with oil." (Of course it was an oil painting.) "Such rough work I never saw in all my life. The picture itself is marvellously like you, and I do not hesitate to say that none of our Chinese painters could get the expression which appears on this picture. What a funny dress you are wearing in this picture. Why are your arms and neck all bare? I have heard that foreign ladies wear their dresses without sleeves and without collars, but I had no idea that it was so bad and ugly as the dress you are wearing here. I cannot imagine how you could do it. I should have thought you would have been ashamed to expose yourself in that manner. Don't wear any more such dresses, please. It has quite shocked me. What a funny kind of civilization this is to be sure. Is this dress only worn on certain occasions, or is it worn any time, even when gentlemen are present?" I explained to her that it was the usual evening dress for ladies and was worn at dinners, balls, receptions, etc. Her Majesty laughed and exclaimed: "This is getting worse and worse. Everything seems to go backwards in foreign countries. Here we don't even expose our wrists when in the company of gentlemen, but foreigners seem to have quite different ideas on the subject. The Emperor is always talking about reform, but if this is a sample we had much better remain as we are. Tell me, have you yet changed your opinion with regard to foreign customs? Don't you think that our own customs are much nicer?" Of course I was obliged to say "yes" seeing that she herself was so prejudiced.

Der Ling. Two Years in the Forbidden City. Project Gutenberg. 1911.

Questions:

- Who is writing and how does she know the Empress?

- Does the Queen seem open to reforms to women’s dress? Why or why not?

Queen Victoria: Journal Entry

This is a short excerpt from one of Queen Victoria’s many journal entries in which she wrote about every aspect of her daily life and her reign as head of the world’s largest empire. In 1877, she was also granted the title of Empress of India, making her the imperial head of a country which Britain had slowly colonized over centuries both through trading alliances and through direct invasion and military defeat of independent Indian states. In this excerpt, the Queen writes of the defeat of a Sikh army in 1846. The Sikh empire was one of the last to submit to British rule.

Wednesday 1st April 1846