10. Women and Reconstruction

|

During the Reconstruction Era, which followed the American Civil War, women faced many new challenges. Freedwomen struggled to find their place in society due to separated families, mistreatment from former masters, racism, and lack of assistance or resources. Some white Northern women worked with the Freedmen's Bureau and helped African Americans where they could. Whereas, white Southern women worked to pick up the pieces of their society while honoring their dead and mythologizing the Confederacy.

|

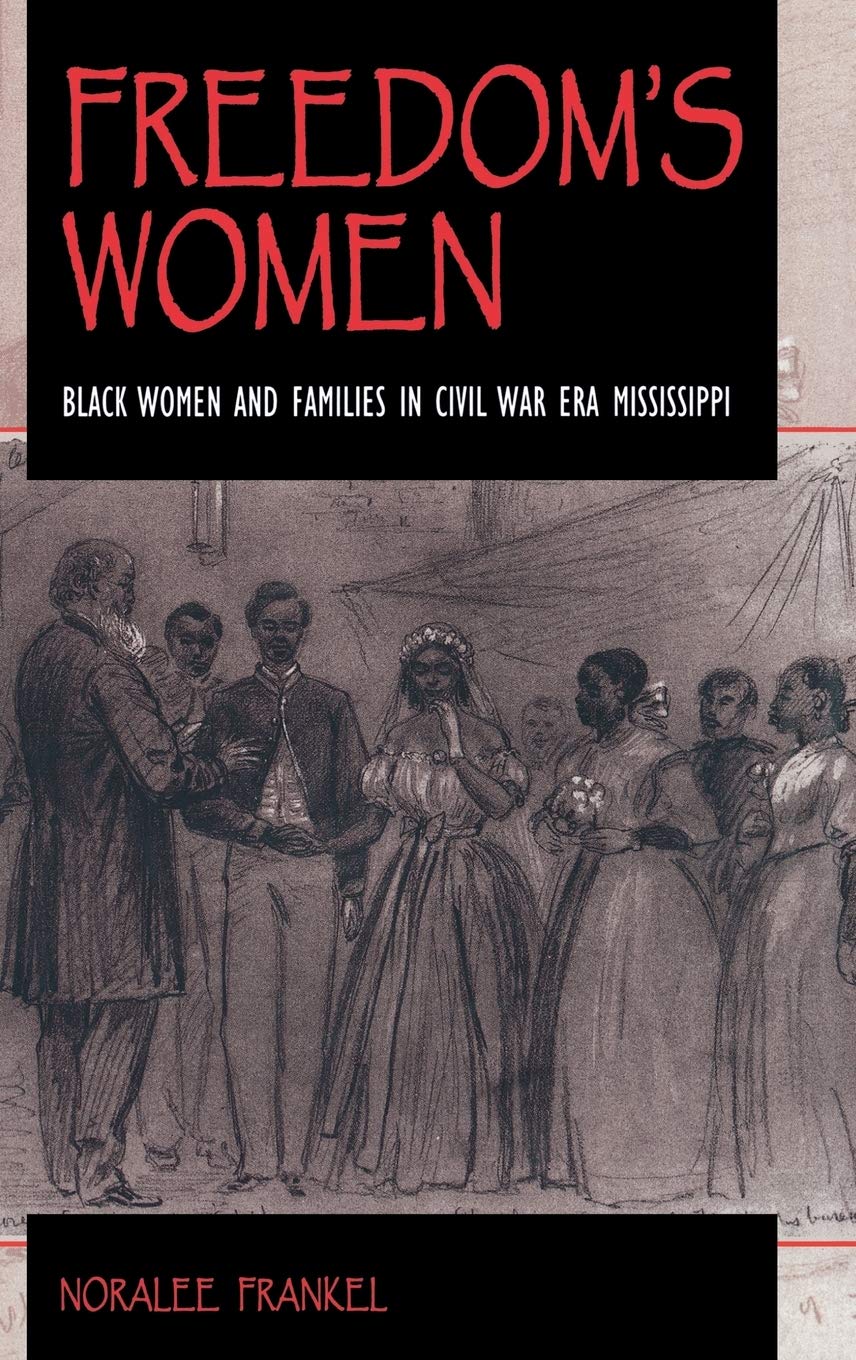

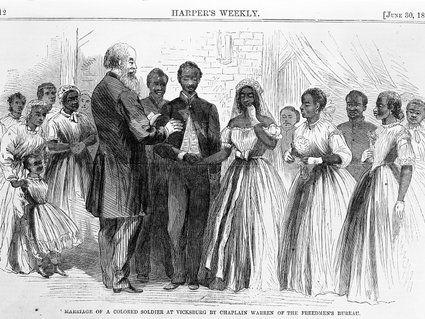

Artwork depicted showing how Freedmen and women gained the ability to be legally recognized as married.

Artwork depicted showing how Freedmen and women gained the ability to be legally recognized as married.

After the Civil War, the struggle to truly emancipate African Americans in the US began. Slavery was a complex and dynamic system of oppression and so was the period of Reconstruction that followed it. To combat rising white terror in the South the Federal Government created the Freedmen's Bureau which supplied food, built schools, and enforced peace in Southern states.

Northern and Southern women also found themselves trying to figure out their place in the aftermath of the Civil War. Black women tested the limits of their newfound freedoms and worked to reconnect with family. Northern white women moved towards helping in the Freedman’s Bureau and teaching African Americans. Whereas, Southern white women began their memorial efforts through Ladies Memorials Associations, which eventually transitioned into a national organization known as the United Daughters of the Confederacy. Southern women are responsible for helping create the Lost Cause and mythologizing the efforts of the Confederacy.

Freedmen's Bureau:

From its beginning, the Freedmen's Bureau attempted to bring the free labor society and culture of the Antebellum North to the post-Emancipation South. Executing these ideals proved very difficult. The bureau, which oversaw 14 states throughout the South and Washington, D.C. had less than 1,000 officers to help newly freed black people build hospitals and schools, negotiate labor contracts, and legalize marriages, alongside any other issues that ex-slaves faced. The officers were housed in small buildings with a desk, a bed, and stove, and saw a nearly- constant line of Blacks and whites knock on the door and ask for assistance. They also face harassment from disgruntled whites, including receiving threats for organizations such as the Ku Klux Klan.

Northern and Southern women also found themselves trying to figure out their place in the aftermath of the Civil War. Black women tested the limits of their newfound freedoms and worked to reconnect with family. Northern white women moved towards helping in the Freedman’s Bureau and teaching African Americans. Whereas, Southern white women began their memorial efforts through Ladies Memorials Associations, which eventually transitioned into a national organization known as the United Daughters of the Confederacy. Southern women are responsible for helping create the Lost Cause and mythologizing the efforts of the Confederacy.

Freedmen's Bureau:

From its beginning, the Freedmen's Bureau attempted to bring the free labor society and culture of the Antebellum North to the post-Emancipation South. Executing these ideals proved very difficult. The bureau, which oversaw 14 states throughout the South and Washington, D.C. had less than 1,000 officers to help newly freed black people build hospitals and schools, negotiate labor contracts, and legalize marriages, alongside any other issues that ex-slaves faced. The officers were housed in small buildings with a desk, a bed, and stove, and saw a nearly- constant line of Blacks and whites knock on the door and ask for assistance. They also face harassment from disgruntled whites, including receiving threats for organizations such as the Ku Klux Klan.

A multitude of newly freed Black women asked the Bureau for help to find food and shelter, what we considered to be the necessities. These women were largely illiterate and most of them were mothers. They spent most of their energy trying to find information on their children, seeking protection from their former masters, and acquiring legal justice to help recover the wages they were being denied and any other form of exploitation that they were facing. Women of color fought for their lives and families in any way they could.

Testing Freedoms:

In many areas of the South, African American women found themselves and their families living with their former masters. They continued working for their previous owner in exchange for shelter and support as they began to grapple with freedom. Another challenge that Black women had to overcome was the anger of their former masters and mistresses as their previous owners struggled with the after effects of the Civil War. White owners found themselves destitute, homeless, traumatized by death, and now, they felt like they were being forced into a position of giving relief to their former slaves at the direction of an occupying northern army. The anger and resentment of their previous owners impacted the lives of African Americans, especially African American women, who were more likely to depend on the welfare of their former masters, as they were often the sole providers of basic necessities for their children. These women found themselves in tragic positions, being abused by their old masters and mistresses so that they could provide their children with the necessities in life. The Freedmen’s Bureau has a multitude of letters and reports showing these accounts of abuse and hardship.

After the war, African American women traveled for many miles on landscapes they knew nothing about seeking some kind of recourse for abuse, to gain the money that was due to them, and to find a safe haven for their families. Laura Scott, an African American woman owned by Robert Garrett, senior on the Greenway Plantation in King William County, Virginia explained that Garrett, Jr., beat her, refused to support her and her five children, who, she claimed, were fathered by Garrett Jr.. Laura also reported that the elder Garrett “left his entire estate to the colored people living on it” and the younger Garrett, unsurprisingly, denied this claim. Not only then, did African American mothers have to worry about supporting their children after freedom, but they were forced to deal with the fact that their children were a product of slavery and were illegitimate children of their previous owners or the owners family. These former masters felt no obligation to the children they fathered and left the women with no legal foundation to stand on for protection.

Testing Freedoms:

In many areas of the South, African American women found themselves and their families living with their former masters. They continued working for their previous owner in exchange for shelter and support as they began to grapple with freedom. Another challenge that Black women had to overcome was the anger of their former masters and mistresses as their previous owners struggled with the after effects of the Civil War. White owners found themselves destitute, homeless, traumatized by death, and now, they felt like they were being forced into a position of giving relief to their former slaves at the direction of an occupying northern army. The anger and resentment of their previous owners impacted the lives of African Americans, especially African American women, who were more likely to depend on the welfare of their former masters, as they were often the sole providers of basic necessities for their children. These women found themselves in tragic positions, being abused by their old masters and mistresses so that they could provide their children with the necessities in life. The Freedmen’s Bureau has a multitude of letters and reports showing these accounts of abuse and hardship.

After the war, African American women traveled for many miles on landscapes they knew nothing about seeking some kind of recourse for abuse, to gain the money that was due to them, and to find a safe haven for their families. Laura Scott, an African American woman owned by Robert Garrett, senior on the Greenway Plantation in King William County, Virginia explained that Garrett, Jr., beat her, refused to support her and her five children, who, she claimed, were fathered by Garrett Jr.. Laura also reported that the elder Garrett “left his entire estate to the colored people living on it” and the younger Garrett, unsurprisingly, denied this claim. Not only then, did African American mothers have to worry about supporting their children after freedom, but they were forced to deal with the fact that their children were a product of slavery and were illegitimate children of their previous owners or the owners family. These former masters felt no obligation to the children they fathered and left the women with no legal foundation to stand on for protection.

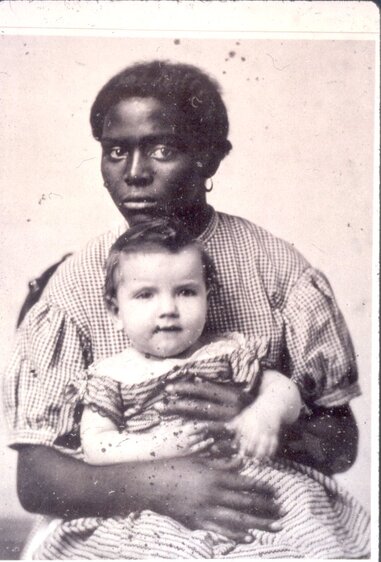

Mary Robsinson

Mary Robsinson

African American women sought help from the legal system to recover lost wages. Maria Barnett of New Kent County filed a complaint about Isiah Higgins because he promised to pay her, but “kept her till the crop was secured and turned her off, beating her severely.” In July 1866, Julia Reynolds presented her case to Provost Marshal Cook in Staunton, Virginia stating that Susan Alexander owed her forty-five dollars for labor stretching from April 1865 to March 1866. The date of when she claimed her labor began is telling. Julia insisted on being paid the same month the Civil War ended. The fact that Julia waited a year to file this complaint is intriguing, but perhaps Alexander could not pay her and kept promising her she would get paid.

In a complaint filed in August 1865, Sally Jackson visited P.S. Evans, a Bureau officer seeking justice and likely protection from John Taylor of King William County who “promised to feed and clothe her and her three children till Christmas.” According to Jackson, Taylor “with no provocation beat her very severely and drove her and her little ones away paying her nothing and threatening to shoot her if she returned.” Black women often found themselves in a convoluted web of expectations and realities that left them focused on food, shelter, and protection for themselves and their children, but left them forced to deal with labels of dependency, laziness, “sassiness”, and situations involving beatings and rape. The sacrifices that African American women made during slavery for their children did not simply vanish after the war; in many ways the challenges of womanhood and motherhood and merging of the two were only now beginning.

One of the first things that women sought after being freed was to reunite, if possible, with their families. These hopes are reflected often in the letters of the Freedmen’s Bureau. In November 1866, Mary Robinson of Winchester, Virginia visited the local Freedmen’s Bureau office to inquire about her two sons, George and Shirley, 16 and 11 years old, both of whom were sold in Richmond in 1862. Mary asked that an advertisement be placed in a local Richmond paper with “the largest southern circulation” for any word of her children. African American newspapers assisted with this effort for years after emancipation, which must have been a daunting task. These women, as chattel with no rights to their own children, are left with relying on strangers, extended family, newspapers, and word of mouth to find their families. Trying to communicate with displaced family members must have also limited the women’s opportunity to travel to find shelter and work. If a woman moved, she would jeopardize her chances of a loved one being able to find her. Her reluctance to move contributed to the false idea that African American women refused to migrate to find work and were lazy and insubordinate.

In a complaint filed in August 1865, Sally Jackson visited P.S. Evans, a Bureau officer seeking justice and likely protection from John Taylor of King William County who “promised to feed and clothe her and her three children till Christmas.” According to Jackson, Taylor “with no provocation beat her very severely and drove her and her little ones away paying her nothing and threatening to shoot her if she returned.” Black women often found themselves in a convoluted web of expectations and realities that left them focused on food, shelter, and protection for themselves and their children, but left them forced to deal with labels of dependency, laziness, “sassiness”, and situations involving beatings and rape. The sacrifices that African American women made during slavery for their children did not simply vanish after the war; in many ways the challenges of womanhood and motherhood and merging of the two were only now beginning.

One of the first things that women sought after being freed was to reunite, if possible, with their families. These hopes are reflected often in the letters of the Freedmen’s Bureau. In November 1866, Mary Robinson of Winchester, Virginia visited the local Freedmen’s Bureau office to inquire about her two sons, George and Shirley, 16 and 11 years old, both of whom were sold in Richmond in 1862. Mary asked that an advertisement be placed in a local Richmond paper with “the largest southern circulation” for any word of her children. African American newspapers assisted with this effort for years after emancipation, which must have been a daunting task. These women, as chattel with no rights to their own children, are left with relying on strangers, extended family, newspapers, and word of mouth to find their families. Trying to communicate with displaced family members must have also limited the women’s opportunity to travel to find shelter and work. If a woman moved, she would jeopardize her chances of a loved one being able to find her. Her reluctance to move contributed to the false idea that African American women refused to migrate to find work and were lazy and insubordinate.

Belle Kearney

Belle Kearney

Women Reformers:

Kay Ann Taylor wrote a great scholarly article about two black women who became educators during this period. She said, “The status of all women during this time was embedded in oppression. Black women lived in greater oppression than White women, thus making it more difficult for Black women to secure sponsorship to participate in the education of the freedpeople. Within this context, the accomplishments and self-determination of Peake and Forten during this time become more significant and compelling.”

The Penn School, which is still around today, was run by abolitionists Charlotte Forten, Ellen Murray, and Laura Towne. The school provided literacy and history instruction as well as practical skills like basketmaking, shoemaking, and carpentry to African-American children.

Mary Ames was a northern white woman who traveled to the south to help educate formerly enslaved people, specifically children. She wrote in her diary, “The school was in a building once used as a biller room, which accommodated a large number of peoples. We often had 120, and word went forth that supplies had come, the number increased. Indeed, it was so crowded that we told the men and women they must stay away to leave space for the children, as we considered teaching them more important…”

In 1868, Martha Schofield, a Quaker from Pennsylvania, brought her life savings of $468 to Aiken, South Carolina to establish a school for newly freed African-American folks. Students could learn basic academics and life skills—like cooking and sewing. The Schofield Normal and Industrial school is now a public middle school.

White Southern Women:

In the South, women not only had to adjust to the loss of free labor, they were also coming to terms with their newfound poverty and the defeat of the Confederacy. The ladies came to terms with their future in many ways. Some spoke out against Reconstruction. Others focused on the slaves who were freed. Ultimately, though, Southern women as a whole came together to honor their dead to to shape the narrative around the ideals of the Confederacy and the reason why the Confederacy lost the war.

Frances Butler Leigh was one of the women who spoke out against Reconstruction. She was a white woman from the South who opposed the Federal Government’s Reconstruction policies, especially when the Radical Republicans imposed military governments in Southern states, forcing the Southern states to rewrite and reformed their Constitutions if they wanted the military forces to leave. Leigh wrote about her frustrations with the new government structure in a letter, “We are, I am afraid, going to have terrible trouble by-and-by with the Negroes, and I see nothing but gloomy prospects for us ahead. The unlimited power the war has put into the hands of the present government at Washington seems to have turned the heads of the party now in office, and they don’t know where to stop. The whole south is settled and quiet, and the people too ruined and crushed to do anything against the government, even if they felt so inclined, and all are returning to their former peaceful pursuits, trying to rebuild their fortunes and thinking of nothing else. Yet the treatment we receive from the government becomes more and more severe every day the last acting to divide the south and to five military districts putting each under the command of the United States general, doing away with civil courts and law.”

Belle Kearney however focused on how she perceived the freeing of her fathers slaves. Kearney, who was the daughter of a white slaveowner observed the practicality of Reconstruction first hand. She wrote, ”As soon as father was physically strong enough to perform the trying duty, he went to the negro quarters on his plantation, assembled his slaves, and announced to them that they were free. There was no wild shout of joy or other demonstration of gladness. The deepest gloom prevailed in their ranks and an expression of mournful bewilderment settled upon their dusky faces. They did not understand that strange, sweet word—freedom. Poor things!... They were stunned. What were they to do? Where would they go? What would become of them? Who would feed and clothe them, and care for them in sickness, when they went out from the “marster” free?”

Kay Ann Taylor wrote a great scholarly article about two black women who became educators during this period. She said, “The status of all women during this time was embedded in oppression. Black women lived in greater oppression than White women, thus making it more difficult for Black women to secure sponsorship to participate in the education of the freedpeople. Within this context, the accomplishments and self-determination of Peake and Forten during this time become more significant and compelling.”

The Penn School, which is still around today, was run by abolitionists Charlotte Forten, Ellen Murray, and Laura Towne. The school provided literacy and history instruction as well as practical skills like basketmaking, shoemaking, and carpentry to African-American children.

Mary Ames was a northern white woman who traveled to the south to help educate formerly enslaved people, specifically children. She wrote in her diary, “The school was in a building once used as a biller room, which accommodated a large number of peoples. We often had 120, and word went forth that supplies had come, the number increased. Indeed, it was so crowded that we told the men and women they must stay away to leave space for the children, as we considered teaching them more important…”

In 1868, Martha Schofield, a Quaker from Pennsylvania, brought her life savings of $468 to Aiken, South Carolina to establish a school for newly freed African-American folks. Students could learn basic academics and life skills—like cooking and sewing. The Schofield Normal and Industrial school is now a public middle school.

White Southern Women:

In the South, women not only had to adjust to the loss of free labor, they were also coming to terms with their newfound poverty and the defeat of the Confederacy. The ladies came to terms with their future in many ways. Some spoke out against Reconstruction. Others focused on the slaves who were freed. Ultimately, though, Southern women as a whole came together to honor their dead to to shape the narrative around the ideals of the Confederacy and the reason why the Confederacy lost the war.

Frances Butler Leigh was one of the women who spoke out against Reconstruction. She was a white woman from the South who opposed the Federal Government’s Reconstruction policies, especially when the Radical Republicans imposed military governments in Southern states, forcing the Southern states to rewrite and reformed their Constitutions if they wanted the military forces to leave. Leigh wrote about her frustrations with the new government structure in a letter, “We are, I am afraid, going to have terrible trouble by-and-by with the Negroes, and I see nothing but gloomy prospects for us ahead. The unlimited power the war has put into the hands of the present government at Washington seems to have turned the heads of the party now in office, and they don’t know where to stop. The whole south is settled and quiet, and the people too ruined and crushed to do anything against the government, even if they felt so inclined, and all are returning to their former peaceful pursuits, trying to rebuild their fortunes and thinking of nothing else. Yet the treatment we receive from the government becomes more and more severe every day the last acting to divide the south and to five military districts putting each under the command of the United States general, doing away with civil courts and law.”

Belle Kearney however focused on how she perceived the freeing of her fathers slaves. Kearney, who was the daughter of a white slaveowner observed the practicality of Reconstruction first hand. She wrote, ”As soon as father was physically strong enough to perform the trying duty, he went to the negro quarters on his plantation, assembled his slaves, and announced to them that they were free. There was no wild shout of joy or other demonstration of gladness. The deepest gloom prevailed in their ranks and an expression of mournful bewilderment settled upon their dusky faces. They did not understand that strange, sweet word—freedom. Poor things!... They were stunned. What were they to do? Where would they go? What would become of them? Who would feed and clothe them, and care for them in sickness, when they went out from the “marster” free?”

The United Daughters of the Confederacy

The United Daughters of the Confederacy

As the ladies shifted their focus from emancipation and Reconstruction they chose to funnel their efforts into honoring the dead with new cemeteries, monuments, and annual Decoration Day observances. Women’s societies created during the war years became Ladies Memorial Associations that helped bring together former Confederates from across the South to help provide funds and support towards reburying the confederate soldiers in newly created Confederate Cemeteries throughout the South. There were Ladies Memorial Associations in every state of the South, and their tireless efforts soon transformed the “ladies groups” into powerful civic organizations that helped shape the programs of local and state governments.

From 1865 to 1890, Ladies Memorial Associations created memorials throughout the South to honor the soldiers who served the Confederacy in the war. At the end of the 19th century, these groups joined together to create a national organization known first as the National Association of the Daughters of the Confederacy. The name changed to United Daughters of the Confederacy shortly after it was established due to the original name being a bit of a handful to say or write. The original mission statement for the UDC asserted that it had been formed to "tell of the glorious fight against the greatest odds a nation ever faced, that their hallowed memory should never die." Southern women truly found their place in helping keep the memory alive of the Confederacy and those who they lost. Just as Northern and Southern women began finding their place in society after the war, so did the newly freedwomen.

Realities for Freedwomen:

The Freedwomen were eager to test their freedom and had clear ideas of what being free really meant. One unnamed freewoman wrote, “One time some Yankee soldiers stopped and started talking to me—they asked me what my name was. I say Liza, and they say, “Do anybody ever call you [the n-word]?” And I say, “Yes Sir.” He say, “Next time anybody call you [that] you tell ’em dat you is a Negro and your name is Miss Liza.” The more I thought of that the more I liked it and I made up my mind to do jest what he told me to. . . . One evening I was minding the calves and old Master come along. He say, “What you doin’ [n-word]?” I say real pert like, “I’se a Negro and I’m Miss Liza Mixon.” Old Master sho’ was surprised and he picks up a switch and starts at me. Law, but I was skeered! . . . I jest said dat to de wrong person.”

From 1865 to 1890, Ladies Memorial Associations created memorials throughout the South to honor the soldiers who served the Confederacy in the war. At the end of the 19th century, these groups joined together to create a national organization known first as the National Association of the Daughters of the Confederacy. The name changed to United Daughters of the Confederacy shortly after it was established due to the original name being a bit of a handful to say or write. The original mission statement for the UDC asserted that it had been formed to "tell of the glorious fight against the greatest odds a nation ever faced, that their hallowed memory should never die." Southern women truly found their place in helping keep the memory alive of the Confederacy and those who they lost. Just as Northern and Southern women began finding their place in society after the war, so did the newly freedwomen.

Realities for Freedwomen:

The Freedwomen were eager to test their freedom and had clear ideas of what being free really meant. One unnamed freewoman wrote, “One time some Yankee soldiers stopped and started talking to me—they asked me what my name was. I say Liza, and they say, “Do anybody ever call you [the n-word]?” And I say, “Yes Sir.” He say, “Next time anybody call you [that] you tell ’em dat you is a Negro and your name is Miss Liza.” The more I thought of that the more I liked it and I made up my mind to do jest what he told me to. . . . One evening I was minding the calves and old Master come along. He say, “What you doin’ [n-word]?” I say real pert like, “I’se a Negro and I’m Miss Liza Mixon.” Old Master sho’ was surprised and he picks up a switch and starts at me. Law, but I was skeered! . . . I jest said dat to de wrong person.”

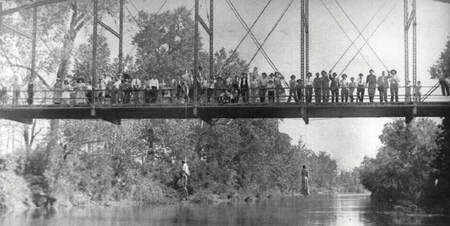

A postcard taken of Laura and L.D. Nelson

A postcard taken of Laura and L.D. Nelson

Black women, now free, were not really free though. On May 25, 1911, Laura Nelson and her son L.D. Nelson were lynched from a bridge over the North Canadian River due to allegations that L.D. Nelson shot and killed George H. Loney, who was Okemah’s deputy sheriff. This killing transpired after the deputy sheriff and a mob of individuals showed up at the Nelson household and accused Laura Nelson’s husband, Austin Nelson, of stealing a cow. Although it is not documented who fired the shot that killed the deputy, it is said that he was shot in self- defense. It is also said that Laura grabbed the gun first and L.D. fired the shot, but there is no record of what actually transpired. Following this incident, Austin, Laura, and L.D. Nelson were taken into custody. Laura and L.D. were charged with murder and awaited trial in the Okemah county jail. Austin pleaded guilty to larceny and was sent to the state prison in McAlester for three years.

According to police officer,W.L. Payne, who was in charge of guarding the cells, a lynch mob of approximately forty white men, tied, bound, and gagged him at gun point. After doing this, they proceeded to kidnap Laura and L.D. Nelson. Although it is presumed that Laura had a baby with her during her stay in jail and lynching, there are no records indicating the existence or survival of the child. After their kidnapping on May 24, the press reported that Laura was raped and then hung along with her thirteen-year-old son L.D. from the Old Schoolton Bridge that ran over the North Canadian River.

Following the event, sightseers gathered to take photos with the hanging bodies. Although a grand jury was convened, Laura and L.D.’s killers were not identified or charged. Despite the fact that there is no exact recounting of the specific details of the events, it is evident that two African American individuals were denied their rights to go through the legal system, instead the community took it upon themselves to take justice into their own hands rather than allowing a fair judicial sentencing. This postcard is one of the few visual records of the lynching of a woman. Aside from the postcard, Laura and her family are memorialized through the works of Woody Guthrie and Andrew Hardaway. Guthrie produced a song entitled, “Don’t Kill My Baby and My Son,” and Hardaway wrote a two-act play, Falling Eve, inspired by the Nelson lynching.

By the end of this era, so much remained in question. Would Black women find freedom after Reconstruction? Would these women find a place in the reform movements of the period? How would Southern women’s new found roles impact the suffrage movement? And could former masters and enslaved women learn to respect one another?

According to police officer,W.L. Payne, who was in charge of guarding the cells, a lynch mob of approximately forty white men, tied, bound, and gagged him at gun point. After doing this, they proceeded to kidnap Laura and L.D. Nelson. Although it is presumed that Laura had a baby with her during her stay in jail and lynching, there are no records indicating the existence or survival of the child. After their kidnapping on May 24, the press reported that Laura was raped and then hung along with her thirteen-year-old son L.D. from the Old Schoolton Bridge that ran over the North Canadian River.

Following the event, sightseers gathered to take photos with the hanging bodies. Although a grand jury was convened, Laura and L.D.’s killers were not identified or charged. Despite the fact that there is no exact recounting of the specific details of the events, it is evident that two African American individuals were denied their rights to go through the legal system, instead the community took it upon themselves to take justice into their own hands rather than allowing a fair judicial sentencing. This postcard is one of the few visual records of the lynching of a woman. Aside from the postcard, Laura and her family are memorialized through the works of Woody Guthrie and Andrew Hardaway. Guthrie produced a song entitled, “Don’t Kill My Baby and My Son,” and Hardaway wrote a two-act play, Falling Eve, inspired by the Nelson lynching.

By the end of this era, so much remained in question. Would Black women find freedom after Reconstruction? Would these women find a place in the reform movements of the period? How would Southern women’s new found roles impact the suffrage movement? And could former masters and enslaved women learn to respect one another?

Draw your own conclusions

|

Learn how to teach with inquiry.

Many of these lesson plans were sponsored in part by the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources Eastern Region Program, coordinated by Waynesburg University, the History and Social Studies Education Faculty at Plymouth State University, and the Patrons of the Remedial Herstory Project. |

Lesson Plans from Other Organizations

- The National Women's History Museum has lesson plans on women's history.

- The Gilder Lehrman Institute for American History has lesson plans on women's history.

- The NY Historical Society has articles and classroom activities for teaching women's history.

- Unladylike 2020, in partnership with PBS, has primary sources to explore with students and outstanding videos on women from the Progressive era.

- The Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media has produced recommendations for teaching women's history with primary sources and provided a collection of sources for world history. Check them out!

- The Stanford History Education Group has a number of lesson plans about women in US History.

Mary Ames: Diary

Mary Ames was a northern white woman who traveled to the south to help educate formerly enslaved people, specifically children. This excerpt comes from her diary.

The school was in a building once used as a biller room, which accommodated a large number of peoples. We often had 120, and word went forth that supplies had come, the number increased. Indeed, it was so crowded that we told the men and women they must stay away to leave space for the children, as we considered teaching them more important...

When we made out the school

report to send to Boston, we were

surprised that out of the hundred, only

three children knew their age, nor had they

the slightest idea of it; one large boy told

me he was “three months old.“ The next day many of them brought pieces of wood or bits of paper with straight marks made on them to show how many years they had lived. One boy brought a family record written in a small book...

In January smallpox brought out among the shoulders quarantined on our place... When... we began school again, we had 13 pupils. One of them, when asked asked if there was any smallpox at her plantation, answered, no, the last one died Saturday.“ On the third day one hundred children had come back.

Ames, Mary. A New England Woman’s Diary in Dixie in 1865. Springfield, 1906. Retrieved from Cheryl Edwards, Ed. Reconstruction: Binding the Wounds. Massachusetts: Discovery Enterprises, Ltd, 1995.

Questions:

The school was in a building once used as a biller room, which accommodated a large number of peoples. We often had 120, and word went forth that supplies had come, the number increased. Indeed, it was so crowded that we told the men and women they must stay away to leave space for the children, as we considered teaching them more important...

When we made out the school

report to send to Boston, we were

surprised that out of the hundred, only

three children knew their age, nor had they

the slightest idea of it; one large boy told

me he was “three months old.“ The next day many of them brought pieces of wood or bits of paper with straight marks made on them to show how many years they had lived. One boy brought a family record written in a small book...

In January smallpox brought out among the shoulders quarantined on our place... When... we began school again, we had 13 pupils. One of them, when asked asked if there was any smallpox at her plantation, answered, no, the last one died Saturday.“ On the third day one hundred children had come back.

Ames, Mary. A New England Woman’s Diary in Dixie in 1865. Springfield, 1906. Retrieved from Cheryl Edwards, Ed. Reconstruction: Binding the Wounds. Massachusetts: Discovery Enterprises, Ltd, 1995.

Questions:

- Summarize the source.

- How many children knew their age? Why does this tell us.

Frances Butler Leigh: Letter

Leigh was a white woman from the South who opposed the Federal Governments Reconstruction policies, especially when the Radical Republicans imposed military governments in Southern states until those states rewrote and reformed their constitutions. Leigh wrote about her frustrations with the military governments in this letter.

We are, I am afraid, going to have terrible trouble by-and-by with the Negroes, and I see nothing but gloomy prospects for us ahead. The unlimited power the war has put into the hands of the present government at Washington seems to have turned the heads of the party now in office, and they don’t know where to stop. The whole south is settled and quiet, and the people to ruined and crushed to do anything against the government, even if they felt so inclined, and all are returning to their former peaceful pursuits, trying to rebuild their fortunes and thinking of nothing else. Yet the treatment we receive from the government becomes more and more severe every day the last acting to divide the south and to five military districts putting each under the command of the United States general, doing away with civil courts and law.

Leigh, Frances Butler. Ten Years on a Georgia Plantation After the War. London: R. Bentley and Son, 1883. Retrieved from Cheryl Edwards, Ed. Reconstruction: Binding the Wounds. Massachusetts: Discovery Enterprises, Ltd, 1995.

Questions:

We are, I am afraid, going to have terrible trouble by-and-by with the Negroes, and I see nothing but gloomy prospects for us ahead. The unlimited power the war has put into the hands of the present government at Washington seems to have turned the heads of the party now in office, and they don’t know where to stop. The whole south is settled and quiet, and the people to ruined and crushed to do anything against the government, even if they felt so inclined, and all are returning to their former peaceful pursuits, trying to rebuild their fortunes and thinking of nothing else. Yet the treatment we receive from the government becomes more and more severe every day the last acting to divide the south and to five military districts putting each under the command of the United States general, doing away with civil courts and law.

Leigh, Frances Butler. Ten Years on a Georgia Plantation After the War. London: R. Bentley and Son, 1883. Retrieved from Cheryl Edwards, Ed. Reconstruction: Binding the Wounds. Massachusetts: Discovery Enterprises, Ltd, 1995.

Questions:

- What is her tone towards black women?

- Based on this source, how was the government treating the South?

Belle Kearney: Account

Kearney was the daughter of a white slave owner. She observed the practicality of Reconstruction first hand.

As soon as father was physically strong enough to perform the trying duty, he went to the negro quarters on his plantation, assembled his slaves, and announced to them that they were free. There was no wild shout of joy or other demonstration of gladness. The deepest gloom prevailed in their ranks and an expression of mournful bewilderment settled upon their dusky faces. They did not understand that strange, sweet word--freedom. Poor things!... They were stunned. What were they to do? Where would they go? What would become of them? Who would feed and clothe them, and care for them in sickness, when they went out from the “marster” free?

Noticing their consternation and dumb sorrow, father told them that they might stay and work for him as hired hands. Some of them did, but the majority drifted away and finally all... In the midst of the social and financial convulsions that surrounded us in those sad days, father stood facing the ruin about him with right hand hopelessly injured and depressed continually by a frail constitution.

Kearney, Belle. A Slaveholder’s Daughter. New York: The Abbey Press, 1900. Retrieved from Cheryl Edwards, Ed. Reconstruction: Binding the Wounds. Massachusetts: Discovery Enterprises, Ltd, 1995.

Questions:

As soon as father was physically strong enough to perform the trying duty, he went to the negro quarters on his plantation, assembled his slaves, and announced to them that they were free. There was no wild shout of joy or other demonstration of gladness. The deepest gloom prevailed in their ranks and an expression of mournful bewilderment settled upon their dusky faces. They did not understand that strange, sweet word--freedom. Poor things!... They were stunned. What were they to do? Where would they go? What would become of them? Who would feed and clothe them, and care for them in sickness, when they went out from the “marster” free?

Noticing their consternation and dumb sorrow, father told them that they might stay and work for him as hired hands. Some of them did, but the majority drifted away and finally all... In the midst of the social and financial convulsions that surrounded us in those sad days, father stood facing the ruin about him with right hand hopelessly injured and depressed continually by a frail constitution.

Kearney, Belle. A Slaveholder’s Daughter. New York: The Abbey Press, 1900. Retrieved from Cheryl Edwards, Ed. Reconstruction: Binding the Wounds. Massachusetts: Discovery Enterprises, Ltd, 1995.

Questions:

- How did slaves react to their newfound freedom?

Unknown: A Formal Enslaved Girl's Story

In this excerpt, she describes an interaction she had with a Union soldier. The misspellings are original to reveal her dialect.

One time some Yankee soldiers stopped and started talking to me--they asked me what my name was. I say Liza, and they say, “Liza who?” I thought a minute and I shook my head. “Jest Liza, I ain’t got no other name.” He say, “Who live up yonder in dat Big House?” I say, “Mr. John Mixon.” He say, “You are Liza Mixon.” He say, “Do anybody ever call you nigger?” And I say, “Yes Sir.” He say, “Next time anybody call you nigger you tell ’em dat you is a Negro and your name is Miss Liza Mixon.” The more I thought of that the more I liked it and I made up my mind to do jest what he told me to. . . . One evening I was minding the calves and old Master come along. He say, “What you doin’ nigger?” I say real pert like, “I ain’t no nigger, I’se a Negro and I’m Miss Liza Mixon.” Old Master sho’ was surprised and he picks up a switch and starts at me. Law, but I was skeered! I hadn’t never had no whipping so I run fast as I can to Grandma Gracie. I hid behind her . . . ’bout that time Master John got there. He say, “Gracie, dat little nigger sassed me.” She say, “Lawsie child, what does ail you?” I told them what the Yankee soldier told me to say and Grandma Gracie took my dress and lift it over my head and pins my hands inside, and Lawsie, how she whipped me . . . I jest said dat to de wrong person.

Excerpted from William E. Gienapp, ed., The Civil War and Reconstruction: A Documentary Collection (New York: W. W. Norton, 2001), 234. Retrieved from https://www.facinghistory.org/sites/default/files/publications/The_Reconstruction_Era_a nd_the_Fragility_of_Democracy_1.pdf.

Questions:

One time some Yankee soldiers stopped and started talking to me--they asked me what my name was. I say Liza, and they say, “Liza who?” I thought a minute and I shook my head. “Jest Liza, I ain’t got no other name.” He say, “Who live up yonder in dat Big House?” I say, “Mr. John Mixon.” He say, “You are Liza Mixon.” He say, “Do anybody ever call you nigger?” And I say, “Yes Sir.” He say, “Next time anybody call you nigger you tell ’em dat you is a Negro and your name is Miss Liza Mixon.” The more I thought of that the more I liked it and I made up my mind to do jest what he told me to. . . . One evening I was minding the calves and old Master come along. He say, “What you doin’ nigger?” I say real pert like, “I ain’t no nigger, I’se a Negro and I’m Miss Liza Mixon.” Old Master sho’ was surprised and he picks up a switch and starts at me. Law, but I was skeered! I hadn’t never had no whipping so I run fast as I can to Grandma Gracie. I hid behind her . . . ’bout that time Master John got there. He say, “Gracie, dat little nigger sassed me.” She say, “Lawsie child, what does ail you?” I told them what the Yankee soldier told me to say and Grandma Gracie took my dress and lift it over my head and pins my hands inside, and Lawsie, how she whipped me . . . I jest said dat to de wrong person.

Excerpted from William E. Gienapp, ed., The Civil War and Reconstruction: A Documentary Collection (New York: W. W. Norton, 2001), 234. Retrieved from https://www.facinghistory.org/sites/default/files/publications/The_Reconstruction_Era_a nd_the_Fragility_of_Democracy_1.pdf.

Questions:

- Is there importance behind her having no last name?

- How do the Yankee soldiers treat her? How does it compare to the Master?

Elias Hall: Testimony

Hall testified at a Senate hearing on terrorist activity he witnessed at his house conducted by Ku Klux Klan member in masked disguises. He described how they ravaged and burned homes of Black people before arriving at his brother’s house.

On the night of the 5th of last May, after I heard a great deal of what they had done in that neighborhood, they came... they came in a very rapid manner, and I could hardly tell whether it was the sound of horses or men. At last they came to my brothers door, which is in the same yard, and broke open the door and attacked his wife, and I heard her screaming and moaning. I could not understand what they said, for they were talking in an outlandish in our natural tone, which I had heard they generally used at a Negroes house. I heard them knocking around at her house. I was lying in my little cabin in the yard. That last I heard them have her in the yard. She was crying, and the Ku Klux Klan were whipping her to make her tell where I lived. I heard her say “Jan is her house.“ She has told me since that they first asked who had taken me out of her house. They said, “Where is Elias?“ She said “He doesn’t stay here; Yon is his house.“ They were then in the yard, and I had heard them strike her five or six licks when I heard her say this. Someone hit my door. It flew open. One ran in the house and stop being about the middle of the house, which is a small cabin, he turned around as it seemed to me as I lay there, awake, and said “Who’s here?“ Then I knew they would take me, and I answered “I am here.“ He shouted for joy, as it seemed, “Here he is! Here he is! We have found him!“ and he threw the bed clothes off of me and caught me by one arm, while another man took me by the other and they carried me into the yard between the houses, my brothers and mine, and put me on the ground beside a boy. The first thing they asked me was, who did that burning? Who burned your houses?“ Gin houses, dwelling houses and such. Some have been burned in the neighborhood. I told them it was not me; I could not burn houses; it was unreasonable to ask me. Then they hit me with their fists, and I said I did it, I ordered it.... They pointed pistols at me... I hoped they would not kill me... One of them took a strap and buckled it around my neck and said, “let’s take him down to the river and drowned him.“ ...With that one of them went into the house where my brother and my sister-in-law lived, and brought her to pick me up. As she stooped down to pick me up one of them struck her, and as she was carrying me into the house another struck her with a strap. She carried me into the house and laid me on the bed.

Van Noppen, Ina Woestemeyer. The South: A Documentary History. Princeton: D. Van Norstrand Company, 1958. From “A Report of the Joint Committee to Inquire into the Conditions of Affairs in the Late Insurrectionary States.” Washington, 1872, vol III. Retrieved from Cheryl Edwards, Ed. Reconstruction: Binding the Wounds. Massachusetts: Discovery Enterprises, Ltd, 1995.

Questions:

On the night of the 5th of last May, after I heard a great deal of what they had done in that neighborhood, they came... they came in a very rapid manner, and I could hardly tell whether it was the sound of horses or men. At last they came to my brothers door, which is in the same yard, and broke open the door and attacked his wife, and I heard her screaming and moaning. I could not understand what they said, for they were talking in an outlandish in our natural tone, which I had heard they generally used at a Negroes house. I heard them knocking around at her house. I was lying in my little cabin in the yard. That last I heard them have her in the yard. She was crying, and the Ku Klux Klan were whipping her to make her tell where I lived. I heard her say “Jan is her house.“ She has told me since that they first asked who had taken me out of her house. They said, “Where is Elias?“ She said “He doesn’t stay here; Yon is his house.“ They were then in the yard, and I had heard them strike her five or six licks when I heard her say this. Someone hit my door. It flew open. One ran in the house and stop being about the middle of the house, which is a small cabin, he turned around as it seemed to me as I lay there, awake, and said “Who’s here?“ Then I knew they would take me, and I answered “I am here.“ He shouted for joy, as it seemed, “Here he is! Here he is! We have found him!“ and he threw the bed clothes off of me and caught me by one arm, while another man took me by the other and they carried me into the yard between the houses, my brothers and mine, and put me on the ground beside a boy. The first thing they asked me was, who did that burning? Who burned your houses?“ Gin houses, dwelling houses and such. Some have been burned in the neighborhood. I told them it was not me; I could not burn houses; it was unreasonable to ask me. Then they hit me with their fists, and I said I did it, I ordered it.... They pointed pistols at me... I hoped they would not kill me... One of them took a strap and buckled it around my neck and said, “let’s take him down to the river and drowned him.“ ...With that one of them went into the house where my brother and my sister-in-law lived, and brought her to pick me up. As she stooped down to pick me up one of them struck her, and as she was carrying me into the house another struck her with a strap. She carried me into the house and laid me on the bed.

Van Noppen, Ina Woestemeyer. The South: A Documentary History. Princeton: D. Van Norstrand Company, 1958. From “A Report of the Joint Committee to Inquire into the Conditions of Affairs in the Late Insurrectionary States.” Washington, 1872, vol III. Retrieved from Cheryl Edwards, Ed. Reconstruction: Binding the Wounds. Massachusetts: Discovery Enterprises, Ltd, 1995.

Questions:

- Summarize this source.

- What is the KKK? What did they do?

Frederick Douglass: On Women's Suffrage

Douglass was one of the few men and the only Black person present at the Seneca Falls Convention. He was a founding member of the Equal Rights Association and he gave this speech in 1888 reflecting on his experience.

Mrs. President, Ladies and Gentlemen:— I come to this platform with unusual diffidence. Although I have long been identified with the Woman’s Suffrage movement, and have often spoken in its favor, I am somewhat at a loss to know what to say on this really great and uncommon occasion, where so much has been said.

When I look around on this assembly, and see the many able and eloquent women, full of the subject, ready to speak, and who only need the opportunity to impress this audience with their views... I do not feel like taking up more than a very small space of your time and attention, and shall not. I would not, even now, presume to speak, but for the circumstance of my early connection with the cause, and of having been called upon to do so... Men have very little business here as speakers, anyhow; and if they come here at all they should take back benches and wrap themselves in silence. For this is an International Council, not of men, but of women, and woman should have all the say in it. This is her day in court...

...When I ran away form slavery, it was for myself; when I advocated emancipation, it was for my people; but when I stood up for the rights of woman, self was out of the question, and I found a little nobility in the act.

...Man has been so long the king and woman the subject--man has been so long accustomed to command and woman to obey... thus has been piled up a mountain of iron against woman’s enfranchisement.

The same thing confronted us in our conflicts with slavery... But neither the power of time nor the might of legislation has been able to keep life in that stupendous barbarism.

Sources: Frederick Douglasss, Woman’s Journal, April 14, 1888.

Questions:

Mrs. President, Ladies and Gentlemen:— I come to this platform with unusual diffidence. Although I have long been identified with the Woman’s Suffrage movement, and have often spoken in its favor, I am somewhat at a loss to know what to say on this really great and uncommon occasion, where so much has been said.

When I look around on this assembly, and see the many able and eloquent women, full of the subject, ready to speak, and who only need the opportunity to impress this audience with their views... I do not feel like taking up more than a very small space of your time and attention, and shall not. I would not, even now, presume to speak, but for the circumstance of my early connection with the cause, and of having been called upon to do so... Men have very little business here as speakers, anyhow; and if they come here at all they should take back benches and wrap themselves in silence. For this is an International Council, not of men, but of women, and woman should have all the say in it. This is her day in court...

...When I ran away form slavery, it was for myself; when I advocated emancipation, it was for my people; but when I stood up for the rights of woman, self was out of the question, and I found a little nobility in the act.

...Man has been so long the king and woman the subject--man has been so long accustomed to command and woman to obey... thus has been piled up a mountain of iron against woman’s enfranchisement.

The same thing confronted us in our conflicts with slavery... But neither the power of time nor the might of legislation has been able to keep life in that stupendous barbarism.

Sources: Frederick Douglasss, Woman’s Journal, April 14, 1888.

Questions:

- Why is Douglass an appropriate speaker at Seneca Falls and future Women’s Rights Conventions?

- Why does Douglass think it is wrong that he is speaking at this event?

- Does he think women’s rights and slavery are the same? How so?

Susan B. Anthony: The Revolution

In 1869 Anthony defended her position in favor of woman suffrage in her suffrage newspaper The Revolution.

The Revolution criticizes, ‘opposes’ the fifteenth amendment, not for what it is, but for what it is not. Not because it enfranchises black men, but because it does not enfranchise all women, black and white. It is not the little good it proposes, but the greater evil it perpetuates that we deprecate. It is not that in the abstract we do not rejoice that black men are to become equals of white men, but that we deplore the fact that two million (sic) black women, hitherto the political and social equals of the men by their side, are to become subjects, slaves of these men. Our protest is not that all men are lifted out of the degradation of disfranchisement, but that all women are left in. The Revolution and the National Women’s Suffrage Association make women’s suffrage their test of loyalty, not Negro suffrage, not Maine law or prohibition. Do you believe women should vote? Is the one and only question in our catechism.

Anthony, Susan B. The Revolution. October 7, 1869. Retrieved from Susan B. Anthony Birthplace Museum. http://www.susanbanthonybirthplace.com/racism.html.

Questions:

1. Who is Susan B. Anthony?

2. Put her argument into your own words.

3. Do you interpret Anthony’s comment to be elitist, anti-gradual enfranchisement, or racist? Why?

The Revolution criticizes, ‘opposes’ the fifteenth amendment, not for what it is, but for what it is not. Not because it enfranchises black men, but because it does not enfranchise all women, black and white. It is not the little good it proposes, but the greater evil it perpetuates that we deprecate. It is not that in the abstract we do not rejoice that black men are to become equals of white men, but that we deplore the fact that two million (sic) black women, hitherto the political and social equals of the men by their side, are to become subjects, slaves of these men. Our protest is not that all men are lifted out of the degradation of disfranchisement, but that all women are left in. The Revolution and the National Women’s Suffrage Association make women’s suffrage their test of loyalty, not Negro suffrage, not Maine law or prohibition. Do you believe women should vote? Is the one and only question in our catechism.

Anthony, Susan B. The Revolution. October 7, 1869. Retrieved from Susan B. Anthony Birthplace Museum. http://www.susanbanthonybirthplace.com/racism.html.

Questions:

1. Who is Susan B. Anthony?

2. Put her argument into your own words.

3. Do you interpret Anthony’s comment to be elitist, anti-gradual enfranchisement, or racist? Why?

Sojourner Truth: Excerpt

Sojourner Truth escaped slavery and lived in Michigan. She changed her name to Sojourner Truth as a symbol of her freedom, Sojourner meaning a person who wanders. She became a powerful and outspoken voice for universal rights and suffrage. She delivered this speech at an Equal Rights Association convention in New York in 1867.

My friends, I am rejoiced that you are glad, but I don't know how you will feel when I get through. I come from another field- the country of the slave. They have got their liberty- so much good luck to have slavery partly destroyed; not entirely. I want it root and branch destroyed. Then we will all be free indeed. I feel that if I have to answer for the deeds done in my body just as much as man, I have a right to have as much as a man. There is a great stir about colored men getting their rights, but not a word about the colored women; and if colored men get their rights, and not colored women theirs, you see the colored men will be masters over the women, and it will be just as bad as it was before. So I am for keeping the thing going while things are stirring; because if we wait till it is still, it will take a great while to get it going again. White women are a great deal smarter, and know more than colored women, while colored women do not know scarcely anything. They go out washing, which is about as high as a colored woman gets, and their men go about idle, strutting up and down; and when the women come home, they ask for their money and take it all, and then scold you because there is no food. I want you to consider on that chil'n. I call you chil'n; you are somebody's chil'n, and I am old enough to be mother of all that is here. I want women to have their rights. In the courts women have no right, no voice; nobody speaks for them. I wish woman to have her voice there among the pettifoggers. If it is not a fit place for women, it us unfit for men to be there.

...I used to work in the field and bind grain, keeping up with the cradler, but men doing no more, got twice as much pay... You have been having our rights so long, that you think, like a slave-holder, that you own us... There ought to be equal rights now more than ever, since colored people have got their freedom.

Truth, Sojourner. “Address to the First Annual Meeting of the American Equal Rights Association.” New York City, May 9, 1867. Retrieved from Society for the Study of American Women Writers. Harriet Jacobs, Ed. https://www.lehigh.edu/~dek7/SSAWW/writTruthAddress.htm.

Questions:

1. Why would Truth be an appropriate speaker at an ERA convention and future Women’s Rights Conventions?

2. Does she think women’s rights and slavery are the same? How so?

3. How is Truth’s message different than Douglass, or are they the same?

My friends, I am rejoiced that you are glad, but I don't know how you will feel when I get through. I come from another field- the country of the slave. They have got their liberty- so much good luck to have slavery partly destroyed; not entirely. I want it root and branch destroyed. Then we will all be free indeed. I feel that if I have to answer for the deeds done in my body just as much as man, I have a right to have as much as a man. There is a great stir about colored men getting their rights, but not a word about the colored women; and if colored men get their rights, and not colored women theirs, you see the colored men will be masters over the women, and it will be just as bad as it was before. So I am for keeping the thing going while things are stirring; because if we wait till it is still, it will take a great while to get it going again. White women are a great deal smarter, and know more than colored women, while colored women do not know scarcely anything. They go out washing, which is about as high as a colored woman gets, and their men go about idle, strutting up and down; and when the women come home, they ask for their money and take it all, and then scold you because there is no food. I want you to consider on that chil'n. I call you chil'n; you are somebody's chil'n, and I am old enough to be mother of all that is here. I want women to have their rights. In the courts women have no right, no voice; nobody speaks for them. I wish woman to have her voice there among the pettifoggers. If it is not a fit place for women, it us unfit for men to be there.

...I used to work in the field and bind grain, keeping up with the cradler, but men doing no more, got twice as much pay... You have been having our rights so long, that you think, like a slave-holder, that you own us... There ought to be equal rights now more than ever, since colored people have got their freedom.

Truth, Sojourner. “Address to the First Annual Meeting of the American Equal Rights Association.” New York City, May 9, 1867. Retrieved from Society for the Study of American Women Writers. Harriet Jacobs, Ed. https://www.lehigh.edu/~dek7/SSAWW/writTruthAddress.htm.

Questions:

1. Why would Truth be an appropriate speaker at an ERA convention and future Women’s Rights Conventions?

2. Does she think women’s rights and slavery are the same? How so?

3. How is Truth’s message different than Douglass, or are they the same?

Elizabeth Cady Stanton: Manhood Suffrage

During the debates over the 15th Amendment, Stanton published these comments in the suffrage newspaper The Revolution. Some historians have argued that she was attempting to use male logic against them.

“Think of Patrick and Sambo [derogatory, meaning mixed-race] and Hans and Yung Tung who do not know the difference between a Monarchy and a Republic, who never read the Declaration of Independence or Webster’s spelling book, making laws for Lydia Maria Child, Lucretia Mott or Fanny Kemble. Think of jurors drawn from these ranks to try young girls for the crime of infanticide.”

Stanton, Elizabeth Cady. “Manhood Suffrage.” The Revolution. Retrieved from Susan B. Anthony Birthplace Museum.

http://www .susanbanthonybirthplace.com/racism.html.

Questions:

1. Do you interpret Stanton’s comment to be elitist, anti-gradual enfranchisement, or racist? Why?

“Think of Patrick and Sambo [derogatory, meaning mixed-race] and Hans and Yung Tung who do not know the difference between a Monarchy and a Republic, who never read the Declaration of Independence or Webster’s spelling book, making laws for Lydia Maria Child, Lucretia Mott or Fanny Kemble. Think of jurors drawn from these ranks to try young girls for the crime of infanticide.”

Stanton, Elizabeth Cady. “Manhood Suffrage.” The Revolution. Retrieved from Susan B. Anthony Birthplace Museum.

http://www .susanbanthonybirthplace.com/racism.html.

Questions:

1. Do you interpret Stanton’s comment to be elitist, anti-gradual enfranchisement, or racist? Why?

Numerous: Minutes from the American Equal Rights Association Convention, 1869

Tensions were high in 1869 as debates over the 15th Amendment raged. Women felt abandoned in the quest for Universal Suffrage. The following are minutes from a debate in the ERA convention.

Mr. Foster: – ...I admire our talented president with all my heart, and love the woman. (Great laughter.) but I believe she has publicly repudiated the principles of the society.

Mrs. Stanton: – I would like Mr. Foster to say in what way.

Mr. Foster: – what are these principles? The equality of men – universal suffrage. These ladies stand at the head of a paper which has adopted its motto educated suffrage. I put myself on this platform as an enemy of educated suffrage, as an enemy of white suffrage, as an enemy of man suffrage, as an enemy of any kind of suffrage except universal suffrage. The Revolution lately had an article headed “That Infamous 15th Amendment.“... The Massachusetts Abolitionists cannot cooperate with the society as it is now organized. If you choose to put officers here that ridicule the Negro, and pronounce the amendment infamous, why... I cannot work with you...

Henry B. Blackwell said:- In regard to the criticisms of our officers, I will agree that many unwise things have been written in The Revolution by a gentleman who furnished part of the means by which that paper has been carried on. But that gentleman has withdrawn and you, who know the real opinions of Miss Anthony and Mrs. Stanton on the questions of Negro Suffrage, do not believe that they mean to create antagonism between the Negro and the woman question. If they did disbelieve in Negro suffrage, it would be no reason for excluding them... But I know that Miss. Anthony and Mrs. Stanton believe in the right of the Negro to vote...

Mr. Douglass: – I came here more as a listener than to speak, and I have listened with a great deal of pleasure to the eloquent address... there is no name greater than that of Elizabeth Caddy Stanton in the matter of women’s rights and equal rights, but my sentiments are tinged a little against The Revolution. There was in the address to which I allude the employment of certain names such as “Sambo,“[derogatory, meaning mixed-race] and the gardener, and the boot black, and the daughters of Jefferson and Washington, and all the rest that I cannot coincide with. I have asked what difference there is between the daughters of Jefferson and Washington and other daughters. (Laughter.) I must say that I do not see how anyone can pretend that there is the same urgency and giving the ballot to woman as to the Negro. With us, the matter is a question of life and death, at least, and 15 states of the union. When women, because they are women, are hunted down through the cities of New York and New Orleans; when they are drag from their houses and hung up on lamp-posts; when their children are torn from their arms, and their brains dashed out upon the pavement; when they are objects of insult and outraged at every turn; When they are in danger of having their homes burnt down over their heads; when their children are not allowed to enter schools; then they will have an urgency to obtain the ballot equal to our own. (Great applause.)

A VOICE:-is that not all true about black women?

Mr. Douglass: – yes, yes, yes; it is true of the black woman, but not because she is a

woman, but because she is black. (Applause.) Julia Ward Howe at the conclusion of her great speech delivered at the convention in Boston last year, said: “I am willing that the Negro shall get the ballot before me.“ (Applause.) Woman! Why, she has 10,000 modes of grappling with her difficulties. I believe that all the virtue of the world can take care of all the evil. I believe that all the intelligence can take care of all the ignorance. (Applause.) I am in favor of women’s suffrage in order that we shall have all the virtue and vice confronted. Let me tell you that when there were a few houses in which the black man could have put his head, this woolly head of mine found a refuge in the house of Miss Elizabeth Caddy Stanton, and if I had been blacker than 16 midnights, without a single star, it would have been the same. (Applause.)

Miss Anthony: – the old anti-slavery school says women must stand back and wait until the Negroes shall be recognized. But we say, if you will not give the whole loaf of suffrage to the entire people, give it to the most intelligent first. (Applause.) if intelligence, justice, and morality are to have precedence in the Government, let the question of woman be brought up first and that of the Negro last. (Applause.) while I was canvassing the state with petitions and had them filled with names for our cause to the legislature, a man dared to say to me that the freedom of women was all a theory and not a practical thing. (Applause.) when Mr. Douglass mentioned the black man first and the woman last, if he had noticed he would have seen that it was the men that clapped and not the women. There is not the woman born who desires to eat the bread of dependence no matter whether it be from the hand of the father, husband, or brother; for anyone who does so eat her bread places herself in the power of the person from whom she takes it. (Applause.) Mr. Douglass talks about the wrongs of the Negro; but

with all the outrageous that he to-day suffers, he would not exchange his sex and

take the place of Elizabeth Caddy Stanton. (Laughter and applause.)

Mr. Douglass: – I want to know if granting you the right of suffrage will change the

nature of our sexes? (Great laughter.)

Miss Anthony: – it will change the pecuniary position of a woman; it will place her

where she can earn her own bread. (Loud applause.) She will not then be driven

to such employment only as man chooses for her.

Mrs. Norton said that Mr. Douglass’ remarks left her to defend the government from the

inferred inability to grapple with the two questions at once. It legislate upon many questions at one and at the same time, it has the power to decide the woman question and the Negro question at one and the same time. (Applause.)

Mrs. Lucy Stone: – Mrs. Stanton will, of course, advocate for the presidents for her sex, and Mr. Douglass will strive for the first position for his, and both are perhaps right. If it be true that the government derives its authority from the constant of the governed, we are safe in trusting that principle to the other most. If one has a right to say that you can not read and therefore cannot vote, then it may be said that you are a woman and therefore cannot vote. We are lost if we turn away from the middle principle and argue for one class. I was once a teacher among fugitive slaves. There was one old man, and every tooth was gone, his hair was white, and his face was full of wrinkles, yet, day after day and hour after hour, he came up to the school house and tried with patients to learn to read, and by- and-by, when he had spelled out the first few verses of the first chapter of the gospel of St. John, he said to me, “now, I want to learn to write.“ I tried to make him satisfied with what he had acquired, but the old man said, “Mrs. Stone, somewhere in the wide world I have A son; I have not heard from him in 20 years; if I should hear from him, I want to write to him, so to take hold of my hand and teach me.“ I did, but before he had preceded in many lessons the angels came and gathered him up and bore him to his Father. Let no man speak of an educated Suffrage. The gentleman who addressed you claimed that the Negroes had the first right to the suffrage, and drew a picture which only his great word Dash power can do. He again in Massachusetts, when it had cast a majority in favor of Grant and Negro Suffrage, stood up on the platform and said that women had better wait for the Negro; that is, that both could not be carried, and that the Negro had better be the one. But I freely for gave him because he felt as he spoke. But woman suffrage is more imperative than his own; and I want to remind the audience that when he says what the Ku Klux‘s is dead all over the south, the Ku Klux Klan is here and the north in the shape of men, take away the children from the mother, and separate them as completely as if done on the block of the auctioneer. Over in New Jersey they have a law which says that any father – he might be the most brutal man that ever existed – any father, it says, whether he be under the age or not, maybe by his last, will and testament dispose of the custody of his child, born or to be born, and that such a disposition shall be good against all persons, and that the mother may not recover her child; and that law modified inform exists over every state in the union except in Kansas. Woman has an ocean of wrongs too deep for any plummet, and the Negro, too, has an ocean of wrongs that cannot be fathomed. There are two great oceans; in the one is the black man, and the other is the woman. But I think God for that XV. Amendment, and hope that it will be adopted in every state. I will be thankful in my soul if anybody can get out of the terrible pit. But I believe that the safety of the government would be more promoted by the admission of woman as an element of restoration in harmony than the Negro. I believe that the influence of woman will save the country before every other power. (Applause.) I see the signs of the times pointing to this consummation, and I believe that in some parts of the country women will vote for the President of the United States in 1872. (Applause.)

Buhle, Mari Jo and Paul Buhle. “The Concise History of Woman Suffrage.” Chicago, University of Illinois Press, 2005.

Questions:

Mr. Foster: – ...I admire our talented president with all my heart, and love the woman. (Great laughter.) but I believe she has publicly repudiated the principles of the society.

Mrs. Stanton: – I would like Mr. Foster to say in what way.

Mr. Foster: – what are these principles? The equality of men – universal suffrage. These ladies stand at the head of a paper which has adopted its motto educated suffrage. I put myself on this platform as an enemy of educated suffrage, as an enemy of white suffrage, as an enemy of man suffrage, as an enemy of any kind of suffrage except universal suffrage. The Revolution lately had an article headed “That Infamous 15th Amendment.“... The Massachusetts Abolitionists cannot cooperate with the society as it is now organized. If you choose to put officers here that ridicule the Negro, and pronounce the amendment infamous, why... I cannot work with you...

Henry B. Blackwell said:- In regard to the criticisms of our officers, I will agree that many unwise things have been written in The Revolution by a gentleman who furnished part of the means by which that paper has been carried on. But that gentleman has withdrawn and you, who know the real opinions of Miss Anthony and Mrs. Stanton on the questions of Negro Suffrage, do not believe that they mean to create antagonism between the Negro and the woman question. If they did disbelieve in Negro suffrage, it would be no reason for excluding them... But I know that Miss. Anthony and Mrs. Stanton believe in the right of the Negro to vote...

Mr. Douglass: – I came here more as a listener than to speak, and I have listened with a great deal of pleasure to the eloquent address... there is no name greater than that of Elizabeth Caddy Stanton in the matter of women’s rights and equal rights, but my sentiments are tinged a little against The Revolution. There was in the address to which I allude the employment of certain names such as “Sambo,“[derogatory, meaning mixed-race] and the gardener, and the boot black, and the daughters of Jefferson and Washington, and all the rest that I cannot coincide with. I have asked what difference there is between the daughters of Jefferson and Washington and other daughters. (Laughter.) I must say that I do not see how anyone can pretend that there is the same urgency and giving the ballot to woman as to the Negro. With us, the matter is a question of life and death, at least, and 15 states of the union. When women, because they are women, are hunted down through the cities of New York and New Orleans; when they are drag from their houses and hung up on lamp-posts; when their children are torn from their arms, and their brains dashed out upon the pavement; when they are objects of insult and outraged at every turn; When they are in danger of having their homes burnt down over their heads; when their children are not allowed to enter schools; then they will have an urgency to obtain the ballot equal to our own. (Great applause.)

A VOICE:-is that not all true about black women?

Mr. Douglass: – yes, yes, yes; it is true of the black woman, but not because she is a

woman, but because she is black. (Applause.) Julia Ward Howe at the conclusion of her great speech delivered at the convention in Boston last year, said: “I am willing that the Negro shall get the ballot before me.“ (Applause.) Woman! Why, she has 10,000 modes of grappling with her difficulties. I believe that all the virtue of the world can take care of all the evil. I believe that all the intelligence can take care of all the ignorance. (Applause.) I am in favor of women’s suffrage in order that we shall have all the virtue and vice confronted. Let me tell you that when there were a few houses in which the black man could have put his head, this woolly head of mine found a refuge in the house of Miss Elizabeth Caddy Stanton, and if I had been blacker than 16 midnights, without a single star, it would have been the same. (Applause.)

Miss Anthony: – the old anti-slavery school says women must stand back and wait until the Negroes shall be recognized. But we say, if you will not give the whole loaf of suffrage to the entire people, give it to the most intelligent first. (Applause.) if intelligence, justice, and morality are to have precedence in the Government, let the question of woman be brought up first and that of the Negro last. (Applause.) while I was canvassing the state with petitions and had them filled with names for our cause to the legislature, a man dared to say to me that the freedom of women was all a theory and not a practical thing. (Applause.) when Mr. Douglass mentioned the black man first and the woman last, if he had noticed he would have seen that it was the men that clapped and not the women. There is not the woman born who desires to eat the bread of dependence no matter whether it be from the hand of the father, husband, or brother; for anyone who does so eat her bread places herself in the power of the person from whom she takes it. (Applause.) Mr. Douglass talks about the wrongs of the Negro; but

with all the outrageous that he to-day suffers, he would not exchange his sex and

take the place of Elizabeth Caddy Stanton. (Laughter and applause.)

Mr. Douglass: – I want to know if granting you the right of suffrage will change the