29. 1950-1990 Transnational Feminism

|

In the last third of the 20th century, women around the globe established a transnational feminist movement that transformed both legal measures and popular discourse about women. Women organized in the United Nations, shared strategies, and effected change in their home countries that improved women's lives.

|

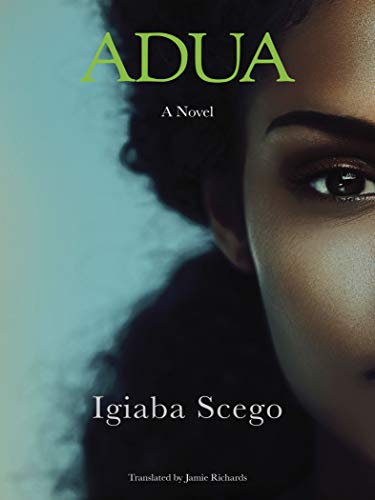

Eleanor Roosevelt with the Declaration of Human Rights, Public Domain

Eleanor Roosevelt with the Declaration of Human Rights, Public Domain

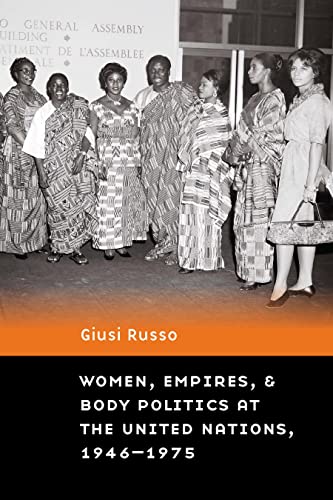

Women and the United Nations

After World War II, women assumed a number of leadership positions in governments and international organizations around the world. Eleanor Roosevelt was a crucial figure in the creation of the United Nations (UN), serving as the US delegate to the UN General Assembly from 1945 to 1952. In 1946, the UN established the Commission on the Status of Women (CSW) as a global policy-making body dedicated to promoting gender equality and women's empowerment. The CSW has since provided a key platform for discussing women's rights issues, reviewing progress, and developing strategies to advance gender equality worldwide.

The first meeting of the United Nations in 1947 in Corona, Queens included 15 female government representatives. Eleanor Roosevelt read "An Open Letter to the Women of the World," which was described as the "first official expression of women's voices within the UN and a blueprint for the role women should have in a new realm of international politics and collaboration." This letter was initiated by Hélène Lefaucheux from France. Lefaucheux also held prominent positions as the president of the French National Council of Women and the president of the International Council of Women (ICW) from 1957 to 1963. The combined efforts of Lefaucheux and Roosevelt aimed to promote human rights, social justice, and international cooperation.

From 1947 to 1962, the CSW focused on establishing standards and sponsoring international conventions to combat discriminatory legislation and raise global awareness of women's issues. Roosevelt served as the first Chair of the UN Commission on Human Rights and was instrumental in advocating for the adoption and implementation of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) in 1984. She traveled extensively, both within the United States and abroad, to engage in conversation on human rights issues. The UDHR explicitly recognized the equal rights and dignity of all individuals, regardless of gender, and emphasized the importance of eliminating discrimination based on sex. This marked a significant step towards recognizing women's rights as human rights on an international scale.

Recognizing the need for data and analysis to support the legal rights of women, the Commission undertook a global assessment of women's status. This extensive research produced a detailed, country-specific overview of women’s political and legal standing, becoming the foundation for drafting human rights policies.

In 1963, the UN General Assembly tasked the CSW with drafting a Declaration on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, adopted in 1967. The legally binding Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) followed in 1979, with the Optional Protocol in 1999, introducing the right of petition for women victims of discrimination.

But feminism looked different in different places around the world. And just because the UN promoted equality didn’t mean women gained rights, freedoms, and respect in their home countries including in the USA and elsewhere. Women activists shared their advances and their setbacks across national borders, seeking to define their grievances and refine the language with which they demanded greater equality and agency. Clearly stating the characteristics that defined a feminist was a particularly challenging undertaking, and the very definition of feminism has been disputed and re-cast over the past several decades. But for the organizers who placed the interests of women at the center of their activism, the goals of feminism, while varied among many individuals and groups, nevertheless coalesced around the idea that women’s needs were important, their voices needed to be heard, and their issues, while personal, deserved to be addressed politically. This perspective dominated international arenas despite other interpretive feminist frameworks.

After World War II, women assumed a number of leadership positions in governments and international organizations around the world. Eleanor Roosevelt was a crucial figure in the creation of the United Nations (UN), serving as the US delegate to the UN General Assembly from 1945 to 1952. In 1946, the UN established the Commission on the Status of Women (CSW) as a global policy-making body dedicated to promoting gender equality and women's empowerment. The CSW has since provided a key platform for discussing women's rights issues, reviewing progress, and developing strategies to advance gender equality worldwide.

The first meeting of the United Nations in 1947 in Corona, Queens included 15 female government representatives. Eleanor Roosevelt read "An Open Letter to the Women of the World," which was described as the "first official expression of women's voices within the UN and a blueprint for the role women should have in a new realm of international politics and collaboration." This letter was initiated by Hélène Lefaucheux from France. Lefaucheux also held prominent positions as the president of the French National Council of Women and the president of the International Council of Women (ICW) from 1957 to 1963. The combined efforts of Lefaucheux and Roosevelt aimed to promote human rights, social justice, and international cooperation.

From 1947 to 1962, the CSW focused on establishing standards and sponsoring international conventions to combat discriminatory legislation and raise global awareness of women's issues. Roosevelt served as the first Chair of the UN Commission on Human Rights and was instrumental in advocating for the adoption and implementation of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) in 1984. She traveled extensively, both within the United States and abroad, to engage in conversation on human rights issues. The UDHR explicitly recognized the equal rights and dignity of all individuals, regardless of gender, and emphasized the importance of eliminating discrimination based on sex. This marked a significant step towards recognizing women's rights as human rights on an international scale.

Recognizing the need for data and analysis to support the legal rights of women, the Commission undertook a global assessment of women's status. This extensive research produced a detailed, country-specific overview of women’s political and legal standing, becoming the foundation for drafting human rights policies.

In 1963, the UN General Assembly tasked the CSW with drafting a Declaration on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, adopted in 1967. The legally binding Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) followed in 1979, with the Optional Protocol in 1999, introducing the right of petition for women victims of discrimination.

But feminism looked different in different places around the world. And just because the UN promoted equality didn’t mean women gained rights, freedoms, and respect in their home countries including in the USA and elsewhere. Women activists shared their advances and their setbacks across national borders, seeking to define their grievances and refine the language with which they demanded greater equality and agency. Clearly stating the characteristics that defined a feminist was a particularly challenging undertaking, and the very definition of feminism has been disputed and re-cast over the past several decades. But for the organizers who placed the interests of women at the center of their activism, the goals of feminism, while varied among many individuals and groups, nevertheless coalesced around the idea that women’s needs were important, their voices needed to be heard, and their issues, while personal, deserved to be addressed politically. This perspective dominated international arenas despite other interpretive feminist frameworks.

Women in the Cultural Revolution, "Proletarian Revolutionary Rebels Unite," Public Domain

Women in the Cultural Revolution, "Proletarian Revolutionary Rebels Unite," Public Domain

Feminism in the Communist World

Women in the communist world also experienced the emergence of feminism, albeit one supported and controlled by state and party interests. The Russian Revolution had initially embraced equality, allowing women to assume various political roles. Women advocated for feminist ideas without explicitly labeling themselves as such, women's liberation was not a central focus of communist political goals. Instead, it was seen as a natural outcome after achieving socialism, with a focus on working-class women rather than women as a whole. In practice, male comrades often resisted treating female comrades as equals, undermining the goal of women's emancipation.

In China, feminism was part of the “Cultural Revolution” led by Mao Zedong from 1966 to 1977. The Cultural Revolution sought to eradicate the "Four Olds": old thoughts, old culture, old habits, and old customs. It promoted revolution and rebellion as positive forces in order to level c=old class distinctions and establish a more equitable society. As part of this campaign, many schools were shut down, and intellectuals were targeted in an effort to reposition them within society.

During the Cultural Revolution, there was a strong emphasis on the promotion of proletarian values and the suppression of perceived bourgeois elements. This included challenging traditional gender roles and hierarchies. The movement sought to dismantle perceived elitism and privilege, and individuals who were seen as upholding those values, regardless of their gender, could become targets. The Chinese government brought healthcare, education, and rural industrialization to the countryside. However, the movement also led to violent actions by the Red Guards, who attacked local party and government officials, teachers, intellectuals, factory managers, and others perceived as enemies of the revolution.

Communist feminism emerged during this time but faced significant challenges. Despite communist ideals of gender equality, women still bore the double burden of domestic work and paid employment, mirroring a problem seen in the Western world as well. Women were rarely seen in top political leadership positions, and communist feminism faded within a decade of its inception in each country. In addition, the one-child policy created pressure in a patriarchal society to have male children which led to femicide.

Communist economies, by the 1970s, showed little progress in catching up to capitalist economies. The Soviet economy was stagnant, and people faced long queues for consumer goods, which were of poor quality and increasingly scarce. Lastly, various incidents undermined communist claims to moral superiority over capitalism. The horrors of Stalin's "Terror" and the gulag, as well as Mao's Cultural Revolution and the genocide in communist Cambodia, were stark reminders of the failures and moral challenges within the communist systems.

For women living in communist systems, the transition to democracy wasn’t necessarily the answer. The loss of basic rights, including sexual equality and reproductive rights, has become a harsh reality. The political opposition's misleading narrative has contributed to the overall suppression of rights, particularly for women. This suppression of women's rights is intertwined with the broader political context. Despite democratic reforms and the promotion of equality ideals, traditional norms and biases continue to dominate. Surprisingly, the absence of a feminist movement in this context is notable, or more precisely, the existing feminism is limited to a relatively marginalized elite and lacks widespread societal support, even from accomplished women activists.

Meanwhile, globally, there was a broader embrace of democracy, feminism, and human rights as the intended legacy of humankind, however this has also been rarely realized.. In the USA in particular, the workplace opened up to women in new ways thanks to the effective agitation by Liberal feminist organizations. But issues such as child and elder care, and lack of maternity leave and parental leave hobbled women’s equality. The democracies of Europe attended more to the fundamental issues that secured equity for women.

Women in the communist world also experienced the emergence of feminism, albeit one supported and controlled by state and party interests. The Russian Revolution had initially embraced equality, allowing women to assume various political roles. Women advocated for feminist ideas without explicitly labeling themselves as such, women's liberation was not a central focus of communist political goals. Instead, it was seen as a natural outcome after achieving socialism, with a focus on working-class women rather than women as a whole. In practice, male comrades often resisted treating female comrades as equals, undermining the goal of women's emancipation.

In China, feminism was part of the “Cultural Revolution” led by Mao Zedong from 1966 to 1977. The Cultural Revolution sought to eradicate the "Four Olds": old thoughts, old culture, old habits, and old customs. It promoted revolution and rebellion as positive forces in order to level c=old class distinctions and establish a more equitable society. As part of this campaign, many schools were shut down, and intellectuals were targeted in an effort to reposition them within society.

During the Cultural Revolution, there was a strong emphasis on the promotion of proletarian values and the suppression of perceived bourgeois elements. This included challenging traditional gender roles and hierarchies. The movement sought to dismantle perceived elitism and privilege, and individuals who were seen as upholding those values, regardless of their gender, could become targets. The Chinese government brought healthcare, education, and rural industrialization to the countryside. However, the movement also led to violent actions by the Red Guards, who attacked local party and government officials, teachers, intellectuals, factory managers, and others perceived as enemies of the revolution.

Communist feminism emerged during this time but faced significant challenges. Despite communist ideals of gender equality, women still bore the double burden of domestic work and paid employment, mirroring a problem seen in the Western world as well. Women were rarely seen in top political leadership positions, and communist feminism faded within a decade of its inception in each country. In addition, the one-child policy created pressure in a patriarchal society to have male children which led to femicide.

Communist economies, by the 1970s, showed little progress in catching up to capitalist economies. The Soviet economy was stagnant, and people faced long queues for consumer goods, which were of poor quality and increasingly scarce. Lastly, various incidents undermined communist claims to moral superiority over capitalism. The horrors of Stalin's "Terror" and the gulag, as well as Mao's Cultural Revolution and the genocide in communist Cambodia, were stark reminders of the failures and moral challenges within the communist systems.

For women living in communist systems, the transition to democracy wasn’t necessarily the answer. The loss of basic rights, including sexual equality and reproductive rights, has become a harsh reality. The political opposition's misleading narrative has contributed to the overall suppression of rights, particularly for women. This suppression of women's rights is intertwined with the broader political context. Despite democratic reforms and the promotion of equality ideals, traditional norms and biases continue to dominate. Surprisingly, the absence of a feminist movement in this context is notable, or more precisely, the existing feminism is limited to a relatively marginalized elite and lacks widespread societal support, even from accomplished women activists.

Meanwhile, globally, there was a broader embrace of democracy, feminism, and human rights as the intended legacy of humankind, however this has also been rarely realized.. In the USA in particular, the workplace opened up to women in new ways thanks to the effective agitation by Liberal feminist organizations. But issues such as child and elder care, and lack of maternity leave and parental leave hobbled women’s equality. The democracies of Europe attended more to the fundamental issues that secured equity for women.

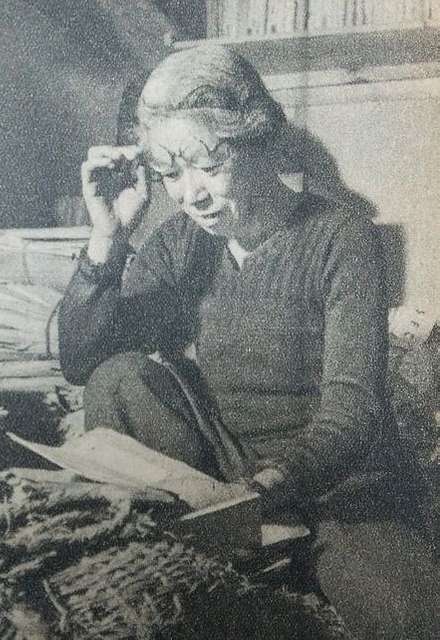

Fusae Ichikawa, Public Domain

Fusae Ichikawa, Public Domain

Western Feminism

In the western world, feminist movements and organizations appeared to advance women’s lives economically, politically, and personally. The goals of these groups varied over time and across national borders. Liberal feminists, like those who headed to the UN to make change, sought to reform institutions from within. These groups tended to attract middle-class women who expressed confidence that their efforts would bring positive results.

By contrast, radical Feminists rejected the idea that reform through traditional societal institutions would bring about the liberation of women. Radical Feminists advocated re-shaping society in a non-hierarchical and non-authoritarian manner. They rejected the male dominance of power structures and advocated the creation of new models for advancing women’s power. The major force to be overthrown from a Radical Feminist perspective was patriarchy. Radical feminists debated whether it was more important to challenge the patriarchy or overthrow capitalism as the root of oppression.

A number of feminist groups took shape around specific issues, and membership in these groups occasionally overlapped. Cultural or Difference Feminists rejected the notion that women should be more like men. They argued that there is a ‘female nature’ or ‘essence’ that makes women fundamentally different from men, and they reject any notion of male superiority. New understandings of gender as a result of the LGBTQ+ movement, and the idea of fluidity have made Difference Feminism outdated or out of place in the present context.

Women in France protested a rigid patriarchal system, a dogmatic and powerful Catholic Church, and the presumption that women did not need a life in the public sphere. French women who had taken part in the protests of 1968 were frustrated at the domination of men in the movement, even as men and women alike shut down universities, barricaded the streets, and demanded a loosening of social restrictions in French life. As they watched their male colleagues write theoretical treatises and make public speeches, women were relegated to tasks that were not recognized by the public or appreciated by their male colleagues.

Nine women affiliated with the MLF launched a women’s liberation protest in Paris. They laid a wreath at the Arc de Triomphe, the site of commemorations of the unknown dead in France’s wars. They called attention to “the one person more unknown than the unknown soldier, his wife.” The march and wreath laying received wide media coverage in France and was an important event in the evolution of France’s organized struggle for women’s liberation.

The most immediate political goal of the MLF was changing the criminal status of abortion in the French Penal Code. Abortion was illegal except to save the life of the mother. On April 5, 1971, the MLF published the Manifeste des 343 (Manifesto of the 343) in La Nouvelle Observateur, a weekly news magazine. This document was both a petition to the national government to change the Penal Code and an act of civil disobedience, as 343 women came forward to declare, “Je me suis fait avorter.” (I have had an abortion).

Lesbians in France had to struggle for their own voice within the discourse of French feminism. Monique Wittig was a prominent feminist theorist and a founder of the Front Homosexual d’Action Revolutionnaire (FHAR, or Homosexual Front for Revolutionary Action). On April 4, 1971, a small group of female FHAR members met to discuss their grievances. An angry member of the audience called the group a gouines rouges or “red dyke.” Both terms are slurs, “red” labels someone as a communist, while “dyke” is an derrogatory term for a lesbian. But not all slurs have to be hurtful and for the FHAR, the name stuck, becoming a badge of honor. The Gouines Rouges worked to organize women and later joined forces with MLF to integrate lesbian issues into the platform of France’s women’s liberation movement.

As late as 1970, women in Britain needed a husband or male relative’s permission to borrow money and had to have an escort to certain restaurants and pubs in the evening. Jobs were advertised by gender in the ‘help wanted’ columns, and only twenty-six of the 650 members of Parliament (MPs) were women in 1970. Domestic violence and marital rape were not crimes, male doctors were often ignorant of women’s health issues, husbands often retained child custody in the case of divorce; and marriage — allowed only to heterosexuals — was still idealized as the high point of a woman’s life.

A very public campaign for labor justice came in the three-year effort to gain higher wages for women who cleaned London offices at night. The Night Cleaners Campaign highlighted both class and gender as sources of women’s oppression. The women spent more than two years starting in 1970 picketing and leafleting in support of their cause. The Transport and General Workers Union offered no support to the night cleaners, as the majority of union men believed that women’s “nature” required them to be in the home rather than on the assembly line or in an office cleaning at night. One might well have asked what a woman would have done if she had wanted to take her late-night food break at a Wimpy Bar.

The legal system was slow to act on behalf of women. Married women gained the right to retain money they earned after marriage in 1964, but since most women did not work outside the home, the law granted them only minimal financial independence. Abortion within 24 weeks of conception was legalized in Britain in 1967, but two doctors had to consent to the procedure, affirming that it was necessary to preserve the life of the mother, and while that may seem reasonable, not all communities have access to two doctors in a timely manner. The Sex Discrimination Act, which outlawed only certain types of discrimination based on sex or marital status, was not passed until 1975.

Feminists have long protested the objectification of women represented by beauty pageants. The parade of women in evening gowns or bathing suits was often likened to a cattle auction. The 1968 protests at the Miss America pageant where a sheep was crowned as an alternative beauty queen was front page news in England. On November 20, 1970, members of Britain’s Women’s Liberation Movement stormed the Miss World pageant at the Royal Albert Hall. The in-person audience and one hundred million worldwide television viewers witnessed protesters throwing tomatoes and flour bombs and shooting water pistols at the stage. The WLM slogan was “We’re not beautiful, we’re not ugly, we’re angry!” They failed to stop the pageant, but the women got the publicity they needed.

Germany was split into the communist East and the capitalist West, the epitome of the Iron Curtain, or wall between the two dominant global worlds. It was not until 1977 that West German married women were allowed to work outside the home without her husband’s permission. The Basic Law of West Germany did not include specific protections for women. Abortion was one of the personal and political issues that inspired West German women to write letters, sign petitions, and risk arrest in public demonstrations. Law 218 of the German Penal Code was passed in 1871 and prohibited abortion under all circumstances. Neue Frauenbewegung (New Women’s Group) activists focused on abortion as essential to a woman’s freedom. The struggle to legalize Fristenlosung, or the termination of a pregnancy in the first trimester, activated the women’s movement in West Germany in the 1970s. Women who called themselves Brot und Rosen-Frauenaktion 70 (Bread and Roses—Women’s Action 70) articulated the earliest demands for access to abortion. Their slogan was Mein Bauch gehort mir! (My belly belongs to me!).

On June 6 1971, the popular news magazine Stern published a statement under the banner headline “We Had an Abortion.” 374 women protested bans on abortion, describing them as outdated. The statement was the creation of Alice Schwarzer, a journalist who was inspired by the efforts of French feminists. The 374 German women who put their names to the Stern statement declared that they had had abortions and thus broken the law. This was a powerful public statement from women who were expected to keep their private lives private.

Women from diverse educational and socioeconomic backgrounds came together around a highly personal political issue. The “scandal” of so many women admitting to having broken the law brought women from all over West Germany to the larger cause of women’s liberation. The publishers of Stern printed the statement on the magazine’s title page. Thousands of people, many with no political affiliation, wrote letters and signed petitions in support of the Stern women. The West German battle over access to abortion was an example of the transnational communication with feminists in the United States, France, and elsewhere that facilitated national political action.

Not surprisingly, Catholic leaders objected to any loosening of legal restrictions on abortion. Cardinal Joseph Hoffner of Cologne issued a statement on abortion that not only re-stated the Church’s position that human life starts at conception, it also reminded politicians of the political power of the Church.

In March of 1974, West Germany’s popular magazine, Der Spiegel, printed a statement from 329 doctors and nurses who said they had performed unpaid (but nevertheless illegal) abortions. Fourteen doctors said they were prepared to break the law by performing an abortion in public. They issued a statement, saying that “Every day 2,000 to 3,000 illegal abortions are carried out in the FRG (Federal Republic of Germany). Our campaign ought to put an end to the hypocrisy.” Women’s “personal” issues had become broadly political. The operation took place on March 9, 1974 at the Kreuzberg Women’s Center and was filmed by the public television Panorama network. But the procedure did not reach the television audience because of a legal challenge brought by the Catholic Church. Panorama executives instead aired footage of an empty studio in protest. In the days after the showing, women in West Germany staged acts of civil disobedience, but the law did not change. West German feminists ‘disrupted beauty contests, bricked up sex-shops, sat in at churches and doctors’ conventions, and organized tribunals on abortion, violence against women, and other central themes in the women’s movement’. One radical women’s group, Rote Zora, destroyed property in forty-five arson attacks and bombings of sexist institutions between 1975 and 1995.

The transnational nature of anti-war protests, challenges to traditional authority, and a recognition of the need for a movement that would act specifically on behalf of women was evident in protests led by Mexican students. A Mexican women’s movement was taking shape as young activists protested the Vietnam War, decried an antiquated and repressive university system, and mocked cultural mores that restricted the lives of young people. When students rallied in the Plaza de las Tres Culturas in the Tlateloco neighborhood of Mexico City on October 2, 1968, they were unprepared for the violence perpetrated by military and police forces. The Tlateloco Massacre took three hundred young lives and imprisoned and tortured many others. The treatment of the students undermined confidence in the government, the police, and other voices of authority in Mexican society. Women participants in the protest challenged the traditional authority of their parents, specifically their fathers, the paternalism of university administrators, and the intransigence of their government. Women began to speak for themselves and were convinced that they would never return to the subservient status they had occupied. The time had come for a new feminist movement in Mexico.

The feminist movement in Mexico was initially inspired by the events of October 1968 and the connections women had made with feminists in Europe and the United States. Many political parties promoted pejorative caricatures of feminists as self-indulgent and egotistical, anti-family and anti-male, and divisive of community and class solidarity. Such stigmas made it difficult to imagine that a feminist movement of any significance would ever take root there.

On Mothers’ Day in 1971, women staged a protest at the Monument to the Mother in Mexico City. They called their action Protesta Contra el Mito de la Mujer (Protest of the Myth of the Mother). The women defied the authorities who denied them a permit to gather at the monument. Coincidentally, contestants in the Miss Mexico competition were also gathered at the monument for a photo opportunity. The irony of potential Miss Mexicos competing for space with protesting mothers was not lost on the local television stations, which showed footage of both groups.

Many Mexican feminists looked to traditional channels and the legal system to integrate women more equally into the public sphere. This ‘feminism of equality’ sought to force political, economic, and social institutions to provide more opportunities for women. Arguing from a differing perspective, proponents of ‘feminism of difference’ were less concerned with equality in society than with locating the source of women’s equality in gender itself. Their areas of focus were violence against women and the demand to legalize abortion. Mexican feminists had transcended their fear of police reprisals and public mockery to articulate their demands. In the late 1970s, lesbian and gay organizations joined with feminist groups to demand equality.

Japanese women in the immediate aftermath of the War, the Women’s Committee on Post-war Policy led by Fusae Ichikawa negotiated more political rights for women, ensuring greater autonomy for them in the political sphere, if not yet in their homes. Women made political progress but they were still, in many respects, second-class citizens.

By the late 1960s, Japan’s feminists focused their protest on the Vietnam War and Japanese capitalism. Women voiced their opposition to the male leadership of New Left organizations and insisted that issues related to sexuality, the absence of power and agency for women, and the role of motherhood in promoting inequality deserved attention. Most male movement leaders paid little attention to the women’s demands. The emergence of feminist organizations in the 1970s contributed to a debate in Japanese society about the threat to masculinity posed by women. Japanese feminists sought more than legal equality. They argued for a transformation of society in which male and female perspectives were equally acknowledged and respected.

In the western world, feminist movements and organizations appeared to advance women’s lives economically, politically, and personally. The goals of these groups varied over time and across national borders. Liberal feminists, like those who headed to the UN to make change, sought to reform institutions from within. These groups tended to attract middle-class women who expressed confidence that their efforts would bring positive results.

By contrast, radical Feminists rejected the idea that reform through traditional societal institutions would bring about the liberation of women. Radical Feminists advocated re-shaping society in a non-hierarchical and non-authoritarian manner. They rejected the male dominance of power structures and advocated the creation of new models for advancing women’s power. The major force to be overthrown from a Radical Feminist perspective was patriarchy. Radical feminists debated whether it was more important to challenge the patriarchy or overthrow capitalism as the root of oppression.

A number of feminist groups took shape around specific issues, and membership in these groups occasionally overlapped. Cultural or Difference Feminists rejected the notion that women should be more like men. They argued that there is a ‘female nature’ or ‘essence’ that makes women fundamentally different from men, and they reject any notion of male superiority. New understandings of gender as a result of the LGBTQ+ movement, and the idea of fluidity have made Difference Feminism outdated or out of place in the present context.

Women in France protested a rigid patriarchal system, a dogmatic and powerful Catholic Church, and the presumption that women did not need a life in the public sphere. French women who had taken part in the protests of 1968 were frustrated at the domination of men in the movement, even as men and women alike shut down universities, barricaded the streets, and demanded a loosening of social restrictions in French life. As they watched their male colleagues write theoretical treatises and make public speeches, women were relegated to tasks that were not recognized by the public or appreciated by their male colleagues.

Nine women affiliated with the MLF launched a women’s liberation protest in Paris. They laid a wreath at the Arc de Triomphe, the site of commemorations of the unknown dead in France’s wars. They called attention to “the one person more unknown than the unknown soldier, his wife.” The march and wreath laying received wide media coverage in France and was an important event in the evolution of France’s organized struggle for women’s liberation.

The most immediate political goal of the MLF was changing the criminal status of abortion in the French Penal Code. Abortion was illegal except to save the life of the mother. On April 5, 1971, the MLF published the Manifeste des 343 (Manifesto of the 343) in La Nouvelle Observateur, a weekly news magazine. This document was both a petition to the national government to change the Penal Code and an act of civil disobedience, as 343 women came forward to declare, “Je me suis fait avorter.” (I have had an abortion).

Lesbians in France had to struggle for their own voice within the discourse of French feminism. Monique Wittig was a prominent feminist theorist and a founder of the Front Homosexual d’Action Revolutionnaire (FHAR, or Homosexual Front for Revolutionary Action). On April 4, 1971, a small group of female FHAR members met to discuss their grievances. An angry member of the audience called the group a gouines rouges or “red dyke.” Both terms are slurs, “red” labels someone as a communist, while “dyke” is an derrogatory term for a lesbian. But not all slurs have to be hurtful and for the FHAR, the name stuck, becoming a badge of honor. The Gouines Rouges worked to organize women and later joined forces with MLF to integrate lesbian issues into the platform of France’s women’s liberation movement.

As late as 1970, women in Britain needed a husband or male relative’s permission to borrow money and had to have an escort to certain restaurants and pubs in the evening. Jobs were advertised by gender in the ‘help wanted’ columns, and only twenty-six of the 650 members of Parliament (MPs) were women in 1970. Domestic violence and marital rape were not crimes, male doctors were often ignorant of women’s health issues, husbands often retained child custody in the case of divorce; and marriage — allowed only to heterosexuals — was still idealized as the high point of a woman’s life.

A very public campaign for labor justice came in the three-year effort to gain higher wages for women who cleaned London offices at night. The Night Cleaners Campaign highlighted both class and gender as sources of women’s oppression. The women spent more than two years starting in 1970 picketing and leafleting in support of their cause. The Transport and General Workers Union offered no support to the night cleaners, as the majority of union men believed that women’s “nature” required them to be in the home rather than on the assembly line or in an office cleaning at night. One might well have asked what a woman would have done if she had wanted to take her late-night food break at a Wimpy Bar.

The legal system was slow to act on behalf of women. Married women gained the right to retain money they earned after marriage in 1964, but since most women did not work outside the home, the law granted them only minimal financial independence. Abortion within 24 weeks of conception was legalized in Britain in 1967, but two doctors had to consent to the procedure, affirming that it was necessary to preserve the life of the mother, and while that may seem reasonable, not all communities have access to two doctors in a timely manner. The Sex Discrimination Act, which outlawed only certain types of discrimination based on sex or marital status, was not passed until 1975.

Feminists have long protested the objectification of women represented by beauty pageants. The parade of women in evening gowns or bathing suits was often likened to a cattle auction. The 1968 protests at the Miss America pageant where a sheep was crowned as an alternative beauty queen was front page news in England. On November 20, 1970, members of Britain’s Women’s Liberation Movement stormed the Miss World pageant at the Royal Albert Hall. The in-person audience and one hundred million worldwide television viewers witnessed protesters throwing tomatoes and flour bombs and shooting water pistols at the stage. The WLM slogan was “We’re not beautiful, we’re not ugly, we’re angry!” They failed to stop the pageant, but the women got the publicity they needed.

Germany was split into the communist East and the capitalist West, the epitome of the Iron Curtain, or wall between the two dominant global worlds. It was not until 1977 that West German married women were allowed to work outside the home without her husband’s permission. The Basic Law of West Germany did not include specific protections for women. Abortion was one of the personal and political issues that inspired West German women to write letters, sign petitions, and risk arrest in public demonstrations. Law 218 of the German Penal Code was passed in 1871 and prohibited abortion under all circumstances. Neue Frauenbewegung (New Women’s Group) activists focused on abortion as essential to a woman’s freedom. The struggle to legalize Fristenlosung, or the termination of a pregnancy in the first trimester, activated the women’s movement in West Germany in the 1970s. Women who called themselves Brot und Rosen-Frauenaktion 70 (Bread and Roses—Women’s Action 70) articulated the earliest demands for access to abortion. Their slogan was Mein Bauch gehort mir! (My belly belongs to me!).

On June 6 1971, the popular news magazine Stern published a statement under the banner headline “We Had an Abortion.” 374 women protested bans on abortion, describing them as outdated. The statement was the creation of Alice Schwarzer, a journalist who was inspired by the efforts of French feminists. The 374 German women who put their names to the Stern statement declared that they had had abortions and thus broken the law. This was a powerful public statement from women who were expected to keep their private lives private.

Women from diverse educational and socioeconomic backgrounds came together around a highly personal political issue. The “scandal” of so many women admitting to having broken the law brought women from all over West Germany to the larger cause of women’s liberation. The publishers of Stern printed the statement on the magazine’s title page. Thousands of people, many with no political affiliation, wrote letters and signed petitions in support of the Stern women. The West German battle over access to abortion was an example of the transnational communication with feminists in the United States, France, and elsewhere that facilitated national political action.

Not surprisingly, Catholic leaders objected to any loosening of legal restrictions on abortion. Cardinal Joseph Hoffner of Cologne issued a statement on abortion that not only re-stated the Church’s position that human life starts at conception, it also reminded politicians of the political power of the Church.

In March of 1974, West Germany’s popular magazine, Der Spiegel, printed a statement from 329 doctors and nurses who said they had performed unpaid (but nevertheless illegal) abortions. Fourteen doctors said they were prepared to break the law by performing an abortion in public. They issued a statement, saying that “Every day 2,000 to 3,000 illegal abortions are carried out in the FRG (Federal Republic of Germany). Our campaign ought to put an end to the hypocrisy.” Women’s “personal” issues had become broadly political. The operation took place on March 9, 1974 at the Kreuzberg Women’s Center and was filmed by the public television Panorama network. But the procedure did not reach the television audience because of a legal challenge brought by the Catholic Church. Panorama executives instead aired footage of an empty studio in protest. In the days after the showing, women in West Germany staged acts of civil disobedience, but the law did not change. West German feminists ‘disrupted beauty contests, bricked up sex-shops, sat in at churches and doctors’ conventions, and organized tribunals on abortion, violence against women, and other central themes in the women’s movement’. One radical women’s group, Rote Zora, destroyed property in forty-five arson attacks and bombings of sexist institutions between 1975 and 1995.

The transnational nature of anti-war protests, challenges to traditional authority, and a recognition of the need for a movement that would act specifically on behalf of women was evident in protests led by Mexican students. A Mexican women’s movement was taking shape as young activists protested the Vietnam War, decried an antiquated and repressive university system, and mocked cultural mores that restricted the lives of young people. When students rallied in the Plaza de las Tres Culturas in the Tlateloco neighborhood of Mexico City on October 2, 1968, they were unprepared for the violence perpetrated by military and police forces. The Tlateloco Massacre took three hundred young lives and imprisoned and tortured many others. The treatment of the students undermined confidence in the government, the police, and other voices of authority in Mexican society. Women participants in the protest challenged the traditional authority of their parents, specifically their fathers, the paternalism of university administrators, and the intransigence of their government. Women began to speak for themselves and were convinced that they would never return to the subservient status they had occupied. The time had come for a new feminist movement in Mexico.

The feminist movement in Mexico was initially inspired by the events of October 1968 and the connections women had made with feminists in Europe and the United States. Many political parties promoted pejorative caricatures of feminists as self-indulgent and egotistical, anti-family and anti-male, and divisive of community and class solidarity. Such stigmas made it difficult to imagine that a feminist movement of any significance would ever take root there.

On Mothers’ Day in 1971, women staged a protest at the Monument to the Mother in Mexico City. They called their action Protesta Contra el Mito de la Mujer (Protest of the Myth of the Mother). The women defied the authorities who denied them a permit to gather at the monument. Coincidentally, contestants in the Miss Mexico competition were also gathered at the monument for a photo opportunity. The irony of potential Miss Mexicos competing for space with protesting mothers was not lost on the local television stations, which showed footage of both groups.

Many Mexican feminists looked to traditional channels and the legal system to integrate women more equally into the public sphere. This ‘feminism of equality’ sought to force political, economic, and social institutions to provide more opportunities for women. Arguing from a differing perspective, proponents of ‘feminism of difference’ were less concerned with equality in society than with locating the source of women’s equality in gender itself. Their areas of focus were violence against women and the demand to legalize abortion. Mexican feminists had transcended their fear of police reprisals and public mockery to articulate their demands. In the late 1970s, lesbian and gay organizations joined with feminist groups to demand equality.

Japanese women in the immediate aftermath of the War, the Women’s Committee on Post-war Policy led by Fusae Ichikawa negotiated more political rights for women, ensuring greater autonomy for them in the political sphere, if not yet in their homes. Women made political progress but they were still, in many respects, second-class citizens.

By the late 1960s, Japan’s feminists focused their protest on the Vietnam War and Japanese capitalism. Women voiced their opposition to the male leadership of New Left organizations and insisted that issues related to sexuality, the absence of power and agency for women, and the role of motherhood in promoting inequality deserved attention. Most male movement leaders paid little attention to the women’s demands. The emergence of feminist organizations in the 1970s contributed to a debate in Japanese society about the threat to masculinity posed by women. Japanese feminists sought more than legal equality. They argued for a transformation of society in which male and female perspectives were equally acknowledged and respected.

Sirimavo Bandaranaike, Public Domain

Sirimavo Bandaranaike, Public Domain

Women Prime Ministers

The 20th Century also saw the rise of women appointed and elected for political office. It had taken centuries since the fall of monarchies, but finally, democracies were coming around to the idea of female leadership. In fact, as of September 2022, the United Nations reported there to be 28 current female world leaders. Female prime ministers, in particular, currently make up roughly 21% of prime ministers worldwide.

While more than 70 countries have now seen women serving in their country’s highest position, there are a handful of women whose impacts were particularly significant.

In 1960, Sirimavo Bandaranaike of Ceylon (later Sri Lanka) became the world’s first female prime minister. Bandaranaike was persuaded to enter the political sphere after her husband, who became prime minister in 1956, was assassinated in 1959. She would serve as prime minister for two terms initially. Bandaranaike created a legacy of female leadership when, in 1994, her daughter, Chandrika Kumaratunga, became president of Sri Lanka and appointed Bandaranaike to return as prime minister for a third term.

The year 1979 was particularly monumental for female prime ministers. Maria da Lourdes Pintasilgo of Portugal became the first female prime minister this year, as did Lidia Gueiler Tejada of Bolivia. Of course, the most well-known woman to be elected as prime minister in 1979 was Margaret Thatcher. Thatcher would become the first female prime minister of the United Kingdom and would also become the longest serving prime minister in modern history with nearly twelve years of public service in the role. Thatcher was tenacious, earning her the name of the “Iron Lady” for her strong-willed leadership style.

Europe would continue to see female prime ministers in the following years. In 1990, Mary Robinson became the first female president of Ireland. She played a significant role in the arenas of human rights, gender equality, and climate change. She was very well-liked throughout the country, receiving a 93% approval rating from the Irish public at her peak.

Golda Meir became Israel’s first female prime minister in 1969. She was particularly instrumental in the creation of the State of Israel as an independent nation as she was one of the 24 signatories (and one of the only two women) to sign the Israeli Declaration of Independence. She would later also earn the title of “Iron Lady” for her leadership during the 19-day Yom Kippur War.

Benazir Bhutto became the first female prime minister of Pakistan in 1988, but she also set another precedent during her time in this role. Bhutto would become the first female world leader to give birth to a child while in office, though she would not be the last.

New Zealand, in particular, has seen a number of female prime ministers, beginning with Jenny Shipley in 1997. Shipley was succeeded in 1999 by another female prime minister, Helen Clark. And, in 2017, Jacinda Arden became New Zealand’s third female prime minister. Arden would follow in Bhutto of Pakistan’s footsteps when she too gave birth to a child while serving as prime minister. Arden set other precedents as the youngest female world leader, banning military-style semi-automatic firearms after the tragic 2019 mosque shootings, and becoming the first prime minister to march in a Pride parade.

The United States has yet to elect a woman to the leadership role of president, but there have still been strides to equalize this field. In 2020, Kamala Harris became the first woman in American History to be elected as Vice President. While the United States still has a way to go, there have been great strides toward gender equality in leadership positions.

Yet the women at the top, don’t represent all women and everywhere women remain the majority of those living in poverty.

The 20th Century also saw the rise of women appointed and elected for political office. It had taken centuries since the fall of monarchies, but finally, democracies were coming around to the idea of female leadership. In fact, as of September 2022, the United Nations reported there to be 28 current female world leaders. Female prime ministers, in particular, currently make up roughly 21% of prime ministers worldwide.

While more than 70 countries have now seen women serving in their country’s highest position, there are a handful of women whose impacts were particularly significant.

In 1960, Sirimavo Bandaranaike of Ceylon (later Sri Lanka) became the world’s first female prime minister. Bandaranaike was persuaded to enter the political sphere after her husband, who became prime minister in 1956, was assassinated in 1959. She would serve as prime minister for two terms initially. Bandaranaike created a legacy of female leadership when, in 1994, her daughter, Chandrika Kumaratunga, became president of Sri Lanka and appointed Bandaranaike to return as prime minister for a third term.

The year 1979 was particularly monumental for female prime ministers. Maria da Lourdes Pintasilgo of Portugal became the first female prime minister this year, as did Lidia Gueiler Tejada of Bolivia. Of course, the most well-known woman to be elected as prime minister in 1979 was Margaret Thatcher. Thatcher would become the first female prime minister of the United Kingdom and would also become the longest serving prime minister in modern history with nearly twelve years of public service in the role. Thatcher was tenacious, earning her the name of the “Iron Lady” for her strong-willed leadership style.

Europe would continue to see female prime ministers in the following years. In 1990, Mary Robinson became the first female president of Ireland. She played a significant role in the arenas of human rights, gender equality, and climate change. She was very well-liked throughout the country, receiving a 93% approval rating from the Irish public at her peak.

Golda Meir became Israel’s first female prime minister in 1969. She was particularly instrumental in the creation of the State of Israel as an independent nation as she was one of the 24 signatories (and one of the only two women) to sign the Israeli Declaration of Independence. She would later also earn the title of “Iron Lady” for her leadership during the 19-day Yom Kippur War.

Benazir Bhutto became the first female prime minister of Pakistan in 1988, but she also set another precedent during her time in this role. Bhutto would become the first female world leader to give birth to a child while in office, though she would not be the last.

New Zealand, in particular, has seen a number of female prime ministers, beginning with Jenny Shipley in 1997. Shipley was succeeded in 1999 by another female prime minister, Helen Clark. And, in 2017, Jacinda Arden became New Zealand’s third female prime minister. Arden would follow in Bhutto of Pakistan’s footsteps when she too gave birth to a child while serving as prime minister. Arden set other precedents as the youngest female world leader, banning military-style semi-automatic firearms after the tragic 2019 mosque shootings, and becoming the first prime minister to march in a Pride parade.

The United States has yet to elect a woman to the leadership role of president, but there have still been strides to equalize this field. In 2020, Kamala Harris became the first woman in American History to be elected as Vice President. While the United States still has a way to go, there have been great strides toward gender equality in leadership positions.

Yet the women at the top, don’t represent all women and everywhere women remain the majority of those living in poverty.

Sharon Farmer, Photograph of First Lady Hillary Clinton at the United Nations Conference on Women in Beijing, China, September 5, 1995. National Archives.

Sharon Farmer, Photograph of First Lady Hillary Clinton at the United Nations Conference on Women in Beijing, China, September 5, 1995. National Archives.

UN Women’s Conferences in the late 20th Century

Addressing the disproportionate impact of poverty on women in the 1960s, the CSW focused on women's needs in community and rural development, agricultural work, family planning, and scientific and technological advances. The Commission advocated for the expansion of technical assistance to advance women's rights, especially in developing countries.

In 1972, marking its 25th anniversary, the CSW recommended designating 1975 as International Women's Year, leading to the First World Conference on Women in Mexico City and the subsequent 1976–1985 UN Decade for Women. This period saw the establishment of new UN offices dedicated to women, including the UN Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM) and the International Research and Training Institute for the Advancement of Women (INSTRAW).

In 1987, following the Third World Conference on Women in Nairobi, the CSW took the lead in coordinating and promoting the UN system's work on economic and social issues for women's empowerment. Efforts shifted towards integrating women's issues as cross-cutting and mainstream concerns, and the Commission played a key role in highlighting violence against women internationally. This led to the adoption of the Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women in 1993, and in 1994, the appointment of a UN Special Rapporteur on violence against women.

Perhaps the most significant CSW World Conference was the fourth, which occurred in 1995 in Beijing, China. There tens of thousands of women flocked together to craft the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action and created systems to monitor it in the decades that followed. The most memorable event from the conference was when then First Lady of the US, Hilary Clinton, addressed the assembly and declared “If there is one message that echoes forth from this conference, it is that human rights are women's rights - and women's rights are human rights. Let us not forget that among those rights are the right to speak freely - and the right to be heard.” But this refrain, which followed a long list of violations too routinely found around the world, was not Clintons, it belonged to the grassroots efforts of thousands of women from around the world. Clinton was just the one to popularize it.

In fact, this groundbreaking event underscored, unlike anything else, the valuable lessons American activists could glean from their global counterparts. This included insights into the detrimental impacts of neoliberal economic policies and the structural adjustment programs of the IMF and World Bank on women.

The connections established during those ten days would lead to fresh enthusiasm, goals, and the emergence of novel organizations, such as the National Asian Pacific American Women’s Forum. Out of the eight thousand Americans who journeyed to China, over a thousand were women of color, affording them the opportunity to engage with 22,000 activists from various nations.

These new connections led to important initiatives, one of the most important being the transnational movement to recognize the survivors of Japanese sexual slavery during World War Two, and to bring restitution to the “Comfort Women.” Thanks to the Violence Against Women in War-Network Japan (VAWW-NET Japan) including efforts by women from the Philippines, Japan and South Korea, a Women’s International War Crimes Tribunal on Japanese Military Sexual Slavery was held in Tokyo in 2000.. It helped bring to light the suffering of the so-called Comfort Women, and continued the fight to memorialize their experiences.

Addressing the disproportionate impact of poverty on women in the 1960s, the CSW focused on women's needs in community and rural development, agricultural work, family planning, and scientific and technological advances. The Commission advocated for the expansion of technical assistance to advance women's rights, especially in developing countries.

In 1972, marking its 25th anniversary, the CSW recommended designating 1975 as International Women's Year, leading to the First World Conference on Women in Mexico City and the subsequent 1976–1985 UN Decade for Women. This period saw the establishment of new UN offices dedicated to women, including the UN Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM) and the International Research and Training Institute for the Advancement of Women (INSTRAW).

In 1987, following the Third World Conference on Women in Nairobi, the CSW took the lead in coordinating and promoting the UN system's work on economic and social issues for women's empowerment. Efforts shifted towards integrating women's issues as cross-cutting and mainstream concerns, and the Commission played a key role in highlighting violence against women internationally. This led to the adoption of the Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women in 1993, and in 1994, the appointment of a UN Special Rapporteur on violence against women.

Perhaps the most significant CSW World Conference was the fourth, which occurred in 1995 in Beijing, China. There tens of thousands of women flocked together to craft the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action and created systems to monitor it in the decades that followed. The most memorable event from the conference was when then First Lady of the US, Hilary Clinton, addressed the assembly and declared “If there is one message that echoes forth from this conference, it is that human rights are women's rights - and women's rights are human rights. Let us not forget that among those rights are the right to speak freely - and the right to be heard.” But this refrain, which followed a long list of violations too routinely found around the world, was not Clintons, it belonged to the grassroots efforts of thousands of women from around the world. Clinton was just the one to popularize it.

In fact, this groundbreaking event underscored, unlike anything else, the valuable lessons American activists could glean from their global counterparts. This included insights into the detrimental impacts of neoliberal economic policies and the structural adjustment programs of the IMF and World Bank on women.

The connections established during those ten days would lead to fresh enthusiasm, goals, and the emergence of novel organizations, such as the National Asian Pacific American Women’s Forum. Out of the eight thousand Americans who journeyed to China, over a thousand were women of color, affording them the opportunity to engage with 22,000 activists from various nations.

These new connections led to important initiatives, one of the most important being the transnational movement to recognize the survivors of Japanese sexual slavery during World War Two, and to bring restitution to the “Comfort Women.” Thanks to the Violence Against Women in War-Network Japan (VAWW-NET Japan) including efforts by women from the Philippines, Japan and South Korea, a Women’s International War Crimes Tribunal on Japanese Military Sexual Slavery was held in Tokyo in 2000.. It helped bring to light the suffering of the so-called Comfort Women, and continued the fight to memorialize their experiences.

Wangari Maathai, Wikimedia Commons

Wangari Maathai, Wikimedia Commons

Women and Climate Change

The planet is warming. Climate change is defined as long-term, large-scale changes in temperature and weather patterns. Scientists have found that today our planet is around 1.1C (1.8F) warmer than it was in the late 19 th Century, and that warming has been caused by human activities. A changing climate is already impacting agriculture, economic productivity, health, and migration across the world. When people are forced to travel because their homes or their livelihoods have been destroyed by climate events, it is called climate migration.

Climate migration affects women and men, but often in different ways. For example, when changes in the climate decrease agricultural productivity, rural families are less able to feed themselves or make a living. In these circumstances, it is more common for men to travel to cities to find jobs. Women, however, are less able to migrate to new opportunities or safer environments because they are more likely to be responsible for taking care of children or ailing family members. Additionally, women on average have less money and are therefore less able to adjust to a changing climate, which might include buying air conditioning units or adopting new farming technologies. Climate change is also likely to increase the hours of unpaid care labor that women must do, since health services and social services are expected to be

impacted by severe weather events.

But women are not just victims. All over the world have also taken up the fight against climate change. In 1977, Kenyan activity Wangari Maathai founded the Green Belt Movement, an indigenous grassroots organization that empowers women through planting trees. Trees can absorb carbon dioxide, a major greenhouse gas that causes climate change, and so one key solution to a changing climate is to protect the world’s forests. For her "contribution to sustainable development, democracy and peace," Wangari Maathai won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2004, becoming the first African woman to do so.

However, to solve a global problem, we need global solutions. In 2010, Costa Rican diplomat Christiana Figueres was appointed Executive Secretary of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, otherwise known as the UNFCCC. The UNFCCC is responsible for the annual climate conferences in which all countries try to work together to solve climate change. For six years, Christiana Figueres worked to bring the nations of the world together, eventually succeeding in the adoption of the 2015 Paris Agreement, through which countries agree to work together to keep warming below 2 °C (3.6 °F).

Since then, young women have taken center stage to keep countries honest about their commitments. In 2018, at just 15 years old, Swedish activist Greta Thunberg began her Skolstrejk för klimatet (School Strike for Climate), which has since grown into a global youth movement in which students skip school on Fridays to attend demonstrations to pressure governments to take climate action. In Uganda, a country already facing rising temperatures, activist Vanessa Nakate initiated her own Fridays For Future strike in 2019, protesting outside of the Parliament of Uganda. She has since founded the Rise up Climate Movement to raise the voices of African climate activists as well as spearheaded a campaign to save Congo’s rainforests. Whether planting trees, building coalitions, or raising their voices, you can find women at the forefront of fighting climate change.

The planet is warming. Climate change is defined as long-term, large-scale changes in temperature and weather patterns. Scientists have found that today our planet is around 1.1C (1.8F) warmer than it was in the late 19 th Century, and that warming has been caused by human activities. A changing climate is already impacting agriculture, economic productivity, health, and migration across the world. When people are forced to travel because their homes or their livelihoods have been destroyed by climate events, it is called climate migration.

Climate migration affects women and men, but often in different ways. For example, when changes in the climate decrease agricultural productivity, rural families are less able to feed themselves or make a living. In these circumstances, it is more common for men to travel to cities to find jobs. Women, however, are less able to migrate to new opportunities or safer environments because they are more likely to be responsible for taking care of children or ailing family members. Additionally, women on average have less money and are therefore less able to adjust to a changing climate, which might include buying air conditioning units or adopting new farming technologies. Climate change is also likely to increase the hours of unpaid care labor that women must do, since health services and social services are expected to be

impacted by severe weather events.

But women are not just victims. All over the world have also taken up the fight against climate change. In 1977, Kenyan activity Wangari Maathai founded the Green Belt Movement, an indigenous grassroots organization that empowers women through planting trees. Trees can absorb carbon dioxide, a major greenhouse gas that causes climate change, and so one key solution to a changing climate is to protect the world’s forests. For her "contribution to sustainable development, democracy and peace," Wangari Maathai won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2004, becoming the first African woman to do so.

However, to solve a global problem, we need global solutions. In 2010, Costa Rican diplomat Christiana Figueres was appointed Executive Secretary of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, otherwise known as the UNFCCC. The UNFCCC is responsible for the annual climate conferences in which all countries try to work together to solve climate change. For six years, Christiana Figueres worked to bring the nations of the world together, eventually succeeding in the adoption of the 2015 Paris Agreement, through which countries agree to work together to keep warming below 2 °C (3.6 °F).

Since then, young women have taken center stage to keep countries honest about their commitments. In 2018, at just 15 years old, Swedish activist Greta Thunberg began her Skolstrejk för klimatet (School Strike for Climate), which has since grown into a global youth movement in which students skip school on Fridays to attend demonstrations to pressure governments to take climate action. In Uganda, a country already facing rising temperatures, activist Vanessa Nakate initiated her own Fridays For Future strike in 2019, protesting outside of the Parliament of Uganda. She has since founded the Rise up Climate Movement to raise the voices of African climate activists as well as spearheaded a campaign to save Congo’s rainforests. Whether planting trees, building coalitions, or raising their voices, you can find women at the forefront of fighting climate change.

Mahsa Amini Protest, Alamy Stock Photo

Mahsa Amini Protest, Alamy Stock Photo

Challenges for Women Today

Many women still face significant obstacles in exercising their basic freedoms, including the right to vote. In Syria, for example, women are effectively excluded from political engagement, including the ongoing peace process. In certain areas of Pakistan, patriarchal customs are used to prevent women from voting, despite it being their constitutional right. Afghanistan has introduced mandatory photo screening at polling stations, making it difficult for women in conservative areas to vote, as they traditionally cover their faces in public. The USA still has not passed the Equal Rights Amendment which guarantees equal legal rights for all American citizens regardless of sex.

Amnesty International advocates for the effective participation of all women in the political process, striving for gender equality. Sexual and reproductive rights are an integral part of these efforts. Every woman and girl should have the right to make decisions about their own body. This includes equal access to health services like contraception and safe abortions, the ability to choose if, when, and whom to marry, and the freedom to decide if they want to have children, as well as how many and with whom.

Unfortunately, there is still a long way to go to ensure these rights for all women. Access to safe and legal abortions remains limited in many parts of the world, forcing individuals to make risky choices or face legal consequences. Organizations like the UN, Amnesty International, and other women’s rights groups have campaigned for changes to strict abortion laws in countries like Argentina, Ireland, Northern Ireland, Poland, and South Korea, achieving significant progress in some cases.

Freedom of movement, a fundamental right, is still restricted for many women. In some places, women may not have their own passports or need permission from a male guardian to travel. Although Saudi Arabia recently lifted the ban on women driving, women's rights activists advocating for their rights continue to face persecution and detention by the authorities.

One other major issue facing women globally is the policing of their sexuality. For example, forced marriage is particularly problematic in Burkina Faso. Usually young girls are married off to older men without their consent. In parts of West Africa and the Horn of Africa female genital mutilation continues to be a serious problem. Practices range from cutting the clitoris, to cutting and sewing up the vulva to create a small opening to the vagina. . Women elders are often in charge of the practice which is often part of puberty rights. The practice is rooted in cultural associations around the need to limit women’s desire as well as the belief that it is required by religion. T In many parts of Southern Africa, confusion around sexual consent and limited access to sexual health services have left women and girls vulnerable to unwanted pregnancies and higher risks of HIV infection. In Jordan, women’s autonomy is threatened by an oppressive male "guardianship" system that restricts women's freedoms and subjects them to degrading "virginity tests." In Iran, women are subjected to a morality police that enforces female chastity and conservative dress codes. In the USA, the overturning of Roe v Wade has also led to increasing state laws that limit women’s access to safe healthcare including abortion.

Women are of course fighting back against these policies. Women and their allies in Iran made history when they rose up against the government in 2022 after Masa Amini was killed in police custody for improperly wearing her hijab, or head covering. Following the reports of this incident, protests erupted across Iran, particularly led by women who tore off their hijabs and adopted a rallying cry of "women, life, freedom."

What started as a protest against the mistreatment of women by the regime has evolved into a larger movement calling for regime change. Amini's death has become a symbol for freedom globally, with her name transformed into a hashtag used millions of times. This protest challenges an entrenched regime that legally treats women as second-class citizens, with discriminatory laws established after the 1979 Islamic Revolution.

Amini's significance lies in being an ordinary woman, making her relatable to many, not an activist. Her death galvanized the Iranian people and drew international attention, resulting in massive protests against compulsory hijab rules. Amini's Kurdish ethnicity played a role, as the Kurdish community turned her funeral into widespread protests. Despite Amini not being the first to die in the custody of Iran's Revolutionary Guard, her ordinary life made her a tangible symbol for countless families who have faced harassment or violence by the morality police.

The protests in Iran have faced a brutal crackdown, with hundreds reported dead and widespread human rights violations. The international community, including the United Nations Human Rights Council, has initiated investigations into these alleged abuses. The hope is that the support from the global community will push for genuine reform in Iran. However, concerns persist that the regime might resort to superficial changes without addressing deeper issues. Despite challenges, Iranian women continue their fight for reform, fueled by the sacrifice of individuals like Mahsa Amini.

Many women still face significant obstacles in exercising their basic freedoms, including the right to vote. In Syria, for example, women are effectively excluded from political engagement, including the ongoing peace process. In certain areas of Pakistan, patriarchal customs are used to prevent women from voting, despite it being their constitutional right. Afghanistan has introduced mandatory photo screening at polling stations, making it difficult for women in conservative areas to vote, as they traditionally cover their faces in public. The USA still has not passed the Equal Rights Amendment which guarantees equal legal rights for all American citizens regardless of sex.

Amnesty International advocates for the effective participation of all women in the political process, striving for gender equality. Sexual and reproductive rights are an integral part of these efforts. Every woman and girl should have the right to make decisions about their own body. This includes equal access to health services like contraception and safe abortions, the ability to choose if, when, and whom to marry, and the freedom to decide if they want to have children, as well as how many and with whom.

Unfortunately, there is still a long way to go to ensure these rights for all women. Access to safe and legal abortions remains limited in many parts of the world, forcing individuals to make risky choices or face legal consequences. Organizations like the UN, Amnesty International, and other women’s rights groups have campaigned for changes to strict abortion laws in countries like Argentina, Ireland, Northern Ireland, Poland, and South Korea, achieving significant progress in some cases.

Freedom of movement, a fundamental right, is still restricted for many women. In some places, women may not have their own passports or need permission from a male guardian to travel. Although Saudi Arabia recently lifted the ban on women driving, women's rights activists advocating for their rights continue to face persecution and detention by the authorities.

One other major issue facing women globally is the policing of their sexuality. For example, forced marriage is particularly problematic in Burkina Faso. Usually young girls are married off to older men without their consent. In parts of West Africa and the Horn of Africa female genital mutilation continues to be a serious problem. Practices range from cutting the clitoris, to cutting and sewing up the vulva to create a small opening to the vagina. . Women elders are often in charge of the practice which is often part of puberty rights. The practice is rooted in cultural associations around the need to limit women’s desire as well as the belief that it is required by religion. T In many parts of Southern Africa, confusion around sexual consent and limited access to sexual health services have left women and girls vulnerable to unwanted pregnancies and higher risks of HIV infection. In Jordan, women’s autonomy is threatened by an oppressive male "guardianship" system that restricts women's freedoms and subjects them to degrading "virginity tests." In Iran, women are subjected to a morality police that enforces female chastity and conservative dress codes. In the USA, the overturning of Roe v Wade has also led to increasing state laws that limit women’s access to safe healthcare including abortion.

Women are of course fighting back against these policies. Women and their allies in Iran made history when they rose up against the government in 2022 after Masa Amini was killed in police custody for improperly wearing her hijab, or head covering. Following the reports of this incident, protests erupted across Iran, particularly led by women who tore off their hijabs and adopted a rallying cry of "women, life, freedom."

What started as a protest against the mistreatment of women by the regime has evolved into a larger movement calling for regime change. Amini's death has become a symbol for freedom globally, with her name transformed into a hashtag used millions of times. This protest challenges an entrenched regime that legally treats women as second-class citizens, with discriminatory laws established after the 1979 Islamic Revolution.

Amini's significance lies in being an ordinary woman, making her relatable to many, not an activist. Her death galvanized the Iranian people and drew international attention, resulting in massive protests against compulsory hijab rules. Amini's Kurdish ethnicity played a role, as the Kurdish community turned her funeral into widespread protests. Despite Amini not being the first to die in the custody of Iran's Revolutionary Guard, her ordinary life made her a tangible symbol for countless families who have faced harassment or violence by the morality police.