18. 1000-1600 Women Explorers and Leaders

|

While historians’ and geographers’ focus has tended to be on voyages of exploration led by men during the so-called “Age of Discovery,” there were women engaged in the same activity. From Viking women making trailblazing journeys, to European Queens ruling countries and funding expeditions, women played a major role in exploration in this era.

|

Female Figurehead on a contemporary ship, Public Domain

Female Figurehead on a contemporary ship, Public Domain

A prevailing superstition among sailors was that a woman on board a ship was bad luck. In fact, few crews included women because they were considered a distraction to the crew. Some believed that a woman’s presence would anger the sea and endanger them all. Others believed female mermaids would pull them into rocky coastlines. Mythical or not, superstition dictated that it was best to avoid women while on board. Sailors were also notoriously drunkards, and social customs encouraged women to avoid such behavior.

Ships, however, which were addressed in the feminine “she” and “her.” In ancient history, ships were named after goddesses, but by the modern era, European ships were increasingly named after mortal women. Despite their reservations about women aboard their ships, sailors believed that naked women calmed the sea, so most figureheads depicted beautiful and topless women as a gift to the sea gods.

When one thinks of the exploration of the New World, visions of ships filled with men claiming new lands come to mind. Beyond being figureheads on ships, women were the financiers and often at the helm of these explorations. The Old and New Worlds are on the brink of connection.

Ships, however, which were addressed in the feminine “she” and “her.” In ancient history, ships were named after goddesses, but by the modern era, European ships were increasingly named after mortal women. Despite their reservations about women aboard their ships, sailors believed that naked women calmed the sea, so most figureheads depicted beautiful and topless women as a gift to the sea gods.

When one thinks of the exploration of the New World, visions of ships filled with men claiming new lands come to mind. Beyond being figureheads on ships, women were the financiers and often at the helm of these explorations. The Old and New Worlds are on the brink of connection.

Chinese Voyagers

The Chinese under the rebounding Ming Dynasty sent explorers into the Pacific and Indian Oceans in the early 1400s. These voyages under the leadership of Zheng He put those of the Europeans to shame. Chinese fleets were so big that the entirety of Columbus's voyage would have fit on just one level of one of the Chinese ships. But these explorations stopped just as quickly as they had begun, owing to a concern that investment in ships did not make economic sense and China retreated into a state of isolationism. Their retreat led to the rise of European traders seeking to fill the void in theIndia trade. Silver obtained from mines in Spanish America enriched Western Europe and was brought to China in exchange for tea and spices.

Europeans became the primary actors in the now “global” economy. They began to explore the Atlantic, looking for a more efficient trading path to the rich spices and teas of Asia. Of course, women were leaders there too.

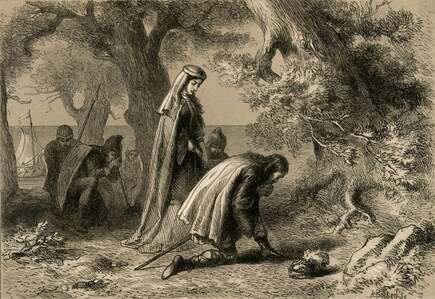

Gudrid the Viking

There were millions of diverse peoples living in the Americas before the arrival of the Old World. Ancient Egyptians are believed to have explored and settled in the Americas over three thousand years ago. Another wave of African exploration is said to have begun several hundred years before Columbus. If we are looking at his venture as the start of European discovery, we ignore the numerous Viking explorations of North America including,, for example, Gudrid’s exploration of Canada, more than 1,000 years ago.

Although women in the Viking Age (c. 790-1100 CE) lived in a male-dominated society, they ran farms and households, were responsible for textile production, and moved away from Scandinavia to help settle Viking territories abroad from Greenland, Iceland, and the British Isles to Russia. Women were likely involved in trade in the sparse urban centers. Some were part of a rich upper class, such as the lady – perhaps a queen – who was buried in the ostentatious Oseberg ship burial in 834 CE. Slaves, among them many women, were taken from conquered territories during the Viking expansion and integrated into Viking Age society.

The Chinese under the rebounding Ming Dynasty sent explorers into the Pacific and Indian Oceans in the early 1400s. These voyages under the leadership of Zheng He put those of the Europeans to shame. Chinese fleets were so big that the entirety of Columbus's voyage would have fit on just one level of one of the Chinese ships. But these explorations stopped just as quickly as they had begun, owing to a concern that investment in ships did not make economic sense and China retreated into a state of isolationism. Their retreat led to the rise of European traders seeking to fill the void in theIndia trade. Silver obtained from mines in Spanish America enriched Western Europe and was brought to China in exchange for tea and spices.

Europeans became the primary actors in the now “global” economy. They began to explore the Atlantic, looking for a more efficient trading path to the rich spices and teas of Asia. Of course, women were leaders there too.

Gudrid the Viking

There were millions of diverse peoples living in the Americas before the arrival of the Old World. Ancient Egyptians are believed to have explored and settled in the Americas over three thousand years ago. Another wave of African exploration is said to have begun several hundred years before Columbus. If we are looking at his venture as the start of European discovery, we ignore the numerous Viking explorations of North America including,, for example, Gudrid’s exploration of Canada, more than 1,000 years ago.

Although women in the Viking Age (c. 790-1100 CE) lived in a male-dominated society, they ran farms and households, were responsible for textile production, and moved away from Scandinavia to help settle Viking territories abroad from Greenland, Iceland, and the British Isles to Russia. Women were likely involved in trade in the sparse urban centers. Some were part of a rich upper class, such as the lady – perhaps a queen – who was buried in the ostentatious Oseberg ship burial in 834 CE. Slaves, among them many women, were taken from conquered territories during the Viking expansion and integrated into Viking Age society.

Stone mentioning Hassmyra, Wikimedia Commons

Stone mentioning Hassmyra, Wikimedia Commons

Almost all Viking Age women were involved in various socio-economic roles. The most common goods found in female graves from this period are spindle whorls, wool combs, and weaving battens, especially in the countryside. Other tasks that do not show up in the archaeological record but are traditionally associated with women include child-rearing and caring for the sick or the elderly. Women likely also did odd jobs around the farm or even some carpentry or leatherworking. How exactly children were brought up and whether girls were treated any differently from boys is unclear. We surmise that daughters could be given in marriage at an appropriate age.

Viking women may have had a good degree of control over running the household and were likely left in charge of matters while their husbands were away or dead. Although subordinate to their husbands, women arguably had significant responsibility and perhaps even control over the running of the household, as

symbolized by the fact they were often buried with keys. Anne-Sophie Gräslund, an archaeologist, has even suggested farms were like firms, "run by husband and wife together, in which the work of both partners was of equal importance although different and complementary" (Sørensen, 260). The people who owned large farms and their adjoining lands would have had considerable means and would likely have belonged to the upper classes within society, they did not reflect all of Viking Age society. Throughout Viking Age society, marriage was a pivotal institution used to create new ties of kinship among Scandinavians and locals in conquered or settled areas. It seems that unmarried women had very limited prospects. Before the advent of Christianity throughout Scandinavia and Viking territories around 1000 CE, concubinage (often connected to slavery), and plural marriages occurred, at least among the royals.

Although it is difficult to define the exact status of Viking Age housewives, their domestic role was a very central one and would not have gone unappreciated. The inscription found on a stone as Hassmyra (Vs 24) – the only verse found on a Swedish inscribed stone that commemorates a woman – certainly seems to confirm this.

Viking women may have had a good degree of control over running the household and were likely left in charge of matters while their husbands were away or dead. Although subordinate to their husbands, women arguably had significant responsibility and perhaps even control over the running of the household, as

symbolized by the fact they were often buried with keys. Anne-Sophie Gräslund, an archaeologist, has even suggested farms were like firms, "run by husband and wife together, in which the work of both partners was of equal importance although different and complementary" (Sørensen, 260). The people who owned large farms and their adjoining lands would have had considerable means and would likely have belonged to the upper classes within society, they did not reflect all of Viking Age society. Throughout Viking Age society, marriage was a pivotal institution used to create new ties of kinship among Scandinavians and locals in conquered or settled areas. It seems that unmarried women had very limited prospects. Before the advent of Christianity throughout Scandinavia and Viking territories around 1000 CE, concubinage (often connected to slavery), and plural marriages occurred, at least among the royals.

Although it is difficult to define the exact status of Viking Age housewives, their domestic role was a very central one and would not have gone unappreciated. The inscription found on a stone as Hassmyra (Vs 24) – the only verse found on a Swedish inscribed stone that commemorates a woman – certainly seems to confirm this.

Gudrid’s identity is a mystery. She is described as beautiful, smart, and political. She appears in a few Viking sagas, but in some she is a poor woman who never reached Greenland during her venture. In other versions, she is a wealthy explorer who not only made it to Greenland but sailed on to Canada with her husband and a small crew. She landed in what the Vikings called Vinland (“wine land”), modern Newfoundland, where she created a settlement and lived for three years. She later returned to Iceland, but her exploring days were not over.

The sagas indicate that Gudrid explored well into her forties and fifties. In her lifetime, it is said that she made eight crossings of the North Atlantic Sea. She may have traveled farther than any other Viking, from Scandinavia to Greenland to North America to Rome and back again in her later life. Archaeologists have found what they believe to be Gudrid’s home in Iceland based on the sagas. It is built in the style of those found in Newfoundland settlements, including the one she and her husband were said to have founded. While Gudrid was the most famous, there were likely other Viking women along with her crew to help form this settlement.

Generally, historians have not given Gudrid the same respect as others who made such voyages, but historian Nancy Marie Brown points out that Gudrid was an adventurer: . “She was not dragged along. This was her choice. She could have very easily stayed home in Greenland. She wanted to go.” Five hundred years before Columbus, and another several hundred years before even the heartiest of men were willing to make the leap to settle the New World, Gudrid had already come and gone.

Isabella and Spain

Christopher Columbus would not have had the money, ships, or crew for his “discovery” of the Americas without the support of Queen Isabella of Spain (1451-1504). Columbus asked Queen Isabella and her husband King Ferdinand to support his exploration. Money was not only key to his proposed journey, it was also essential to the Queen’s and King’s continued unification of Spain. They were trying to unify a Catholic Spain at the cost of the Muslims and Jews among their population and finding a new route to the Asian spice markets would save the Spanish money by avoiding the trading middlemen on the land routes or the pirates on the sea routes.

The sagas indicate that Gudrid explored well into her forties and fifties. In her lifetime, it is said that she made eight crossings of the North Atlantic Sea. She may have traveled farther than any other Viking, from Scandinavia to Greenland to North America to Rome and back again in her later life. Archaeologists have found what they believe to be Gudrid’s home in Iceland based on the sagas. It is built in the style of those found in Newfoundland settlements, including the one she and her husband were said to have founded. While Gudrid was the most famous, there were likely other Viking women along with her crew to help form this settlement.

Generally, historians have not given Gudrid the same respect as others who made such voyages, but historian Nancy Marie Brown points out that Gudrid was an adventurer: . “She was not dragged along. This was her choice. She could have very easily stayed home in Greenland. She wanted to go.” Five hundred years before Columbus, and another several hundred years before even the heartiest of men were willing to make the leap to settle the New World, Gudrid had already come and gone.

Isabella and Spain

Christopher Columbus would not have had the money, ships, or crew for his “discovery” of the Americas without the support of Queen Isabella of Spain (1451-1504). Columbus asked Queen Isabella and her husband King Ferdinand to support his exploration. Money was not only key to his proposed journey, it was also essential to the Queen’s and King’s continued unification of Spain. They were trying to unify a Catholic Spain at the cost of the Muslims and Jews among their population and finding a new route to the Asian spice markets would save the Spanish money by avoiding the trading middlemen on the land routes or the pirates on the sea routes.

Portrait of Queen Elizabeth I, wikimedia commons

Portrait of Queen Elizabeth I, wikimedia commons

Upon Columbus’s “discovery” of the Americas, which he thought opened a new route to Asia, he returned with a number of indigenous captives, who he mistakenly called “Indians” Isabella ordered some of these enslaved people to be freed,and was even considering the prospect of rights for them under the Spanish crown, but died in 1504. By then, explorers had realized that this was not Asia at all, but something entirely new.

Isabella was not the only Spanish monarch to fund expeditions to the New World, but she did help to unify Spain and established a strong and profitable court which made future expeditions possible. As a result, Spain held a monopoly on the exploration and riches of the New World for hundreds of years.

As Spain’s influence grew throughout South and Central America, the indigenous people suffered terribly as a consequence. European diseases such as smallpox spread rapidly throughout native population, which had no immunity to new pathogens. Historians estimate that up to 95 percent of the indigenous population died in the hundred to hundred and fifty years after Columbus’s voyage in 1492. Natives were also slaughtered, brutalized, and made homeless by the rampaging Spanish conquistadors. Women were victimized, but they also helped to support resistance efforts as well as protect their families through cooperation.

Queen Elizabeth and England

By the turn of the 16th century, the New World became the obsession of all Europeans, and soon the Spanish were not the only nation to explore and conquer the Americas. The Portuguese, French, Dutch, and Swedish all made their presence known. England’s Queen Elizabeth I who made exploration the cornerstone of her reign.

Queen of England from 1558-1603, Elizabeth remains one of the most famous and successful European monarchs. She not only defeated the mighty Spanish Armada, she also dominated politics, economic growth, and art. In addition, she also set the stage for England to become a primary power in the New World. She was well-educated, with one of her tutors, Roger Ascham, stating that “Her mind has no womanly weakness, […] her perseverance is equal to that of a man, and her memory long keeps what it quickly picks up.” For example, the number of people she witnessed being executed by her father, Henry the VIII, including her mother, taught her to keep her political and religious views to herself until she found herself in power.

.

Elizabeth quickly reorganized England’s power structure. She was perpetually scrutinized by a society that viewed women as mere detours to the real figures of power, men. Britons largely believed women unfit and too temperamental for power. Their job as monarchs was to bring the right men into power by marrying or birthing them. Elizabeth refused to play this role. Both before and after her coronation, she refused to marry. English nobles and international nobles courted her, but still she refused each, proclaiming that she had to make a careful decision for the protection of England. In reality, she likely didn’t want to give up her power. While many feared a civil war if the queen did not bear a natural heir, she played her game well.

Isabella was not the only Spanish monarch to fund expeditions to the New World, but she did help to unify Spain and established a strong and profitable court which made future expeditions possible. As a result, Spain held a monopoly on the exploration and riches of the New World for hundreds of years.

As Spain’s influence grew throughout South and Central America, the indigenous people suffered terribly as a consequence. European diseases such as smallpox spread rapidly throughout native population, which had no immunity to new pathogens. Historians estimate that up to 95 percent of the indigenous population died in the hundred to hundred and fifty years after Columbus’s voyage in 1492. Natives were also slaughtered, brutalized, and made homeless by the rampaging Spanish conquistadors. Women were victimized, but they also helped to support resistance efforts as well as protect their families through cooperation.

Queen Elizabeth and England

By the turn of the 16th century, the New World became the obsession of all Europeans, and soon the Spanish were not the only nation to explore and conquer the Americas. The Portuguese, French, Dutch, and Swedish all made their presence known. England’s Queen Elizabeth I who made exploration the cornerstone of her reign.

Queen of England from 1558-1603, Elizabeth remains one of the most famous and successful European monarchs. She not only defeated the mighty Spanish Armada, she also dominated politics, economic growth, and art. In addition, she also set the stage for England to become a primary power in the New World. She was well-educated, with one of her tutors, Roger Ascham, stating that “Her mind has no womanly weakness, […] her perseverance is equal to that of a man, and her memory long keeps what it quickly picks up.” For example, the number of people she witnessed being executed by her father, Henry the VIII, including her mother, taught her to keep her political and religious views to herself until she found herself in power.

.

Elizabeth quickly reorganized England’s power structure. She was perpetually scrutinized by a society that viewed women as mere detours to the real figures of power, men. Britons largely believed women unfit and too temperamental for power. Their job as monarchs was to bring the right men into power by marrying or birthing them. Elizabeth refused to play this role. Both before and after her coronation, she refused to marry. English nobles and international nobles courted her, but still she refused each, proclaiming that she had to make a careful decision for the protection of England. In reality, she likely didn’t want to give up her power. While many feared a civil war if the queen did not bear a natural heir, she played her game well.

Elizabeth led a weak, impoverished nation without a standing army but with a corrupt political system. She used every weapon available to her, including her gender and society’s expectation that she should marry, to manipulate suitors into helping her country. Despite their fears of a woman remaining in power, she convinced many of the love she had for her country through these efforts.

Throughout her reign, Elizabeth faced opposition, both internal and external, religious and secular, but she remained vigilant in her vision of an England rising in power. She poked the European bears of France and Spain with sanctioned privateering and raids on their international ports.Despite its weakness, her naval forces defeated the mighty Spanish Armada. She defied society's gender roles by parading in front of her men in armor, promising them great reward if they were victorious, and proclaiming, “I know I have the body of a weak and feeble woman, but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and of a king of England too.” Their victory gave the Bi\ritish navy a position of naval strength that would soon become naval superiority.

Her reign was not without controversy. Executions, bursts of rage, political manipulation, attempts to subjugate the Irish, famines, and more framed her reputation. In her efforts to compete with her European counterparts, she also looked to the possibilities of the New World. But the English found themselves facing populations of indigenous people occupying the lands the Europeans felt they deserved.

Conclusion

Women were at the forefront of European efforts to discover a better path to Asian markets. When looking at this period through a wider lens that includes the roles of women, how does your perspective of exploration change? How are women’s efforts remembered, and how can they be better celebrated or analyzed?

Throughout her reign, Elizabeth faced opposition, both internal and external, religious and secular, but she remained vigilant in her vision of an England rising in power. She poked the European bears of France and Spain with sanctioned privateering and raids on their international ports.Despite its weakness, her naval forces defeated the mighty Spanish Armada. She defied society's gender roles by parading in front of her men in armor, promising them great reward if they were victorious, and proclaiming, “I know I have the body of a weak and feeble woman, but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and of a king of England too.” Their victory gave the Bi\ritish navy a position of naval strength that would soon become naval superiority.

Her reign was not without controversy. Executions, bursts of rage, political manipulation, attempts to subjugate the Irish, famines, and more framed her reputation. In her efforts to compete with her European counterparts, she also looked to the possibilities of the New World. But the English found themselves facing populations of indigenous people occupying the lands the Europeans felt they deserved.

Conclusion

Women were at the forefront of European efforts to discover a better path to Asian markets. When looking at this period through a wider lens that includes the roles of women, how does your perspective of exploration change? How are women’s efforts remembered, and how can they be better celebrated or analyzed?

Draw your own conclusions

|

Learn how to teach with inquiry.

Many of these lesson plans were sponsored in part by the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources Eastern Region Program, coordinated by Waynesburg University, the History and Social Studies Education Faculty at Plymouth State University, and the Patrons of the Remedial Herstory Project. |

Lesson Plans from Other Organizations

- This website, Women in World History has primary source based lesson plans on women's history in a whole range of topics. Some are free while others have a cost.

- The Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media has produced recommendations for teaching women's history with primary sources and provided a collection of sources for world history. Check them out!

- The Stanford History Education Group has a number of lesson plans about women in World History.

Coming Soon...

Remedial Herstory Editors. "18. 1000-1600 WOMEN EXPLORERS AND LEADERS." The Remedial Herstory Project. November 1, 2022. www.remedialherstory.com.

Primary AUTHOR: |

Jacqui Nelson

|

Primary Reviewer: |

Dr. Katherine Koh

|

Consulting Team |

Editors |

|

Kelsie Brook Eckert, Project Director

Coordinator of Social Studies Education at Plymouth State University Dr. Nancy Locklin-Sofer, Consultant Professor of History at Maryville College. Chloe Gardner, Consultant PhD Candidate in Religious Studies at Edinburgh University Dr. Whitney Howarth, Consultant Former Professor of History at Plymouth State University Jacqui Nelson, Consultant Teaching Lecturer of Military History at Plymouth State University Maria Concepcion Marquez Sandoval PhD Candidate in History at Arizona University |

Amy Flanders

Humanities Teacher, Moultonborough Academy ReviewersAncient:

Dr. Kristin Heineman Professor of History at Colorado State University Dr. Bonnie Rock-McCutcheon Professor of History at Wilson College Sarah Stone PhD Candidate in Religious Studies at Edinburgh University Medieval: Dr. Katherine Koh Professor of History at La Sierra University Dr. Jonathan Couser Professor of History at Plymouth State University Dr. Shahla Haeri Professor of History at Boston University Lauren Cole PhD Candidate in History at Northwestern University Modern: Dr. Barbara Tischler Supervisor for Hunter College Dr. Pamela Scully Professor of Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies and African Studies at Emory University |

|

Focusing on the century between the introduction of Christianity in Japan by Portuguese Jesuit missionaries in 1549 and the Japanese government's commitment to the eradication of Christianity in the mid-seventeenth century, this book outlines how women provided crucial leadership in the spread, nurture, and maintenance of the faith through various apostolic ministries.

Medieval women were normally denied access to public educational institutions, and so also denied the gateways to most leadership positions. Modern scholars have therefore tended to study learned medieval women as simply anomalies, and women generally as victims. This volume, however, argues instead for a via media. Drawing upon manuscript and archival sources, scholars here show that more medieval women attained some form of learning than hitherto imagined, and that women with such legal, social or ecclesiastical knowledge also often exercised professional or communal leadership.

The year was 1765. Eminent botanist Philibert Commerson had just been appointed to a grand new expedition: the first French circumnavigation of the world. As the ships’ official naturalist, Commerson would seek out resources—medicines, spices, timber, food—that could give the French an edge in the ever-accelerating race for empire. Jeanne Baret, Commerson’s young mistress and collaborator, was desperate not to be left behind. She disguised herself as a teenage boy and signed on as his assistant. The journey made the twenty-six-year-old, known to her shipmates as “Jean” rather than “Jeanne,” the first woman to ever sail around the globe. Yet so little is known about this extraordinary woman, whose accomplishments were considered to be subversive, even impossible for someone of her sex and class.

Much of her life is shrouded in mystery. Putting aside Cecilys role as mother and wife, who was she really? Matriarch of the York dynasty, she navigated through a tumultuous period and lived to see the birth of the future Henry VIII. From seeing the house of York defeat their Lancastrian cousins; to witnessing the defeat of her own son, Richard III, at the battle of Bosworth, Cecily then saw one of her granddaughters become Henry VIIs queen consort. Her story is full of controversy and the few published books on her life are full of guesswork. In this highly original history, Dr John Ashdown-Hill seeks to dispel the myths surrounding Cecily using previously unexamined contemporary sources.

|

|

|

Eccentric Lady Jane Franklin makes an outlandish offer to adventurer Virginia Reeve: take a dozen women, trek into the Arctic, and find her husband's lost expedition. Four parties have failed to find him, and Lady Franklin wants a radical new approach: put the women in charge. A year later, Virginia stands trial for murder. Survivors of the expedition willing to publicly support her sit in the front row. There are only five. What happened out there on the ice?

|

Elizabeth of York, her life already tainted by dishonour and tragedy, now queen to the first Tudor king, Henry the VII. Joan Vaux, servant of the court, straining against marriage and motherhood and privy to the deepest and darkest secrets of her queen. Like the ravens, Joan must use her eyes and her senses, as conspiracy whispers through the dark corridors of the Tower. Through Joan’s eyes, The Lady of the Ravens inhabits the squalid streets of Tudor London, the imposing walls of its most fearsome fortress and the glamorous court of a kingdom in crisis.

|

Captain Thurídur, born in Iceland in 1777, lived a life that was both controversial and unconventional. Her first time fishing, on the open unprotected rowboats of her time, was at age 11. Soon after, she audaciously began wearing trousers. She later became an acclaimed fishing captain brilliant at weather-reading and seacraft and consistently brought in the largest catches. In the Arctic seas where drownings occurred with terrifying regularity, she never lost a single crewmember. Renowned for her acute powers of observation, she also solved a notorious crime. In this extremely unequal society, she used the courts to fight for justice for the abused, and in her sixties, embarked on perilous journeys over trackless mountains.

|

Prehistory (3,300,000-3000 BC)

They live in caves and huddle around fires, but they are fully human, though they belong to our most ancient history. Risa the Arbiter has now spent years in her role and is known and respected throughout the area. Her children are half-grown and exhibiting traits of independence, both of thought and action. Her tribe has grown along with her and now needs more than one Arbiter can provide alone. Risa struggles with how best to organize her duties and establishes acolytes in each village to screen petitioners.

Ancient HISTORY (3000 BC - 500 AD)

|

The men of Athens gather to determine the truth. Meanwhile, the women of the city, who have no vote, are gathering in the shadows. The women know truth is a slippery thing in the hands of men. There are two sides to every story, and theirs has gone unheard. Until now.

Timely, unflinching, and transportive, Laura Shepperson’s Phaedra carves open long-accepted wounds to give voice to one of the most maligned figures of mythology and offers a stunning story of how truth bends under the weight of patriarchy but can be broken open by the force of one woman’s bravery. |

|

Middle ages (500-1500 ad)

|

The earl of Trent's Norman widow, Blanche, and her English steward, Miles Edwulfson, take possession of Blanche's estates, hoping to live a life of peace and quiet. However, they run afoul of a baron named Aimerie, who is building an illegal castle and taxing the surrounding manors--including Blanche's--to pay for it. Aimerie has ambitions that go far beyond this castle, to the heart of the English throne, and he won't let anyone stand in his way. What's more, Aimerie's hot-headed son, Ernoul, lusts after Blanche and wants to make her his wife. When Blanche and Miles refuse to pay Aimerie's taxes, Aimerie vows to crush them.

Though Japan has been devastated by a century of civil war, Risuko just wants to climb trees. Growing up far from the battlefields and court intrigues, the fatherless girl finds herself pulled into a plot that may reunite Japan -- or may destroy it. She is torn from her home and what is left of her family, but finds new friends at a school that may not be what it seems

|

For all fifteen years of her life, Pauline de Pamiers has witnessed an attack on her family, friends, and faith. It’s the early thirteenth century and the Pope and King of France are conducting a Crusade against the Cathars; the only crusade on European soil and against another Christian sect. As a member of this sect in France that sits outside the dominant Roman Church, Pauline is an outsider: young, but independent and bold.

11th century North Africa. In an attempt to change her destiny, love-struck Zaynab makes a false prophecy: that she is destined to marry a man who will create an empire. Although her plan backfires, Zaynab’s intelligence, beauty and ambition leads to four marriages, each lifting her status higher.

|

Eleanor of Aquitaine, one of the most powerful women in Europe, is crowned queen of England beside her young husband Henry II. While Henry battles their enemies and lays his plans, Eleanor is an adept acting ruler and mother to their growing brood of children. But she yearns for more than this - if only Henry would listen.

England, 1364: When married off at aged twelve to an elderly farmer, brazen redheaded Eleanor quickly realizes it won’t matter what she says or does, God is not on her side—or any poor woman’s for that matter. But then again, Eleanor was born under the joint signs of Venus and Mars, making her both a lover and a fighter.

|

Early modern (1500-1800 ad)

|

Runner-up for the National Book Award for Children's Literature in 1969, Constance is a classic of historical young adult fiction, recounting the daily life, hardships, romances, and marriage of a young girl during the early years of the Pilgrim settlement at Plymouth.

Sirma used to be happy. She had a home, loving parents, and wonderful friends. But her quiet mountain village changed forever when she lost her two best friends to a gang of outlaws. The village elders did nothing, fearing the wrath of Hamza Bei – the head outlaw in the area. Not long after, the same outlaws returned and devastated her village. Sirma has had enough. On St. George’s day, she disguised herself as a man and lead her own mountain gang dedicated to protecting the mountain villages and searching for Hamza Bei to put a stop to his tyranny. But the path she has chosen is harsh and merciless. Clashing with gangs of outlaws, surviving the elements in the mountain wilderness, and keeping her men from becoming the scoundrels they’ve sworn to fight are just a few of the challenges. But the biggest issue was the fact that her comrades had no idea they were led by a woman.

The author of The Soong Dynasty gives us our most vivid and reliable biography yet of the Dowager Empress Tzu Hsi, remembered through the exaggeration and falsehood of legend as the ruthless Manchu concubine who seduced and murdered her way to the Chinese throne in 1861.

|

|

Explorers and leaders

HOW TO TEACH WITH FILMS:

Remember, teachers want the student to be the historian. What do historians do when they watch films?

- Before they watch, ask students to research the director and producers. These are the source of the information. How will their background and experience likely bias this film?

- Also, ask students to consider the context the film was created in. The film may be about history, but it was made recently. What was going on the year the film was made that could bias the film? In particular, how do you think the gains of feminism will impact the portrayal of the female characters?

- As they watch, ask students to research the historical accuracy of the film. What do online sources say about what the film gets right or wrong?

- Afterward, ask students to describe how the female characters were portrayed and what lessons they got from the film.

- Then, ask students to evaluate this film as a learning tool. Was it helpful to better understand this topic? Did the historical inaccuracies make it unhelpful? Make it clear any informed opinion is valid.

|

Elizabeth (1998)

The early years of the reign of Elizabeth I of England and her difficult task of learning what is necessary to be a monarch. IMDB |

|

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Durn, Sara. “Did a Viking Woman Named Gudrid Really Travel to North America in 1000 A.D.?.” Smithsonian. March 3, 2021. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/did-viking-woman-named-gudrid-really-travel-north-america-1000-years-ago-180977126/.

Groeneveld, Emma. "Women in the Viking Age." World History Encyclopedia. Last modified July 11, 2018. https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1251/women-in-the-viking-age/.

Miles, Rosalind. The Women’s History of the World. London, UK: HarperCollins Publishers, 1988.

Sara Pruitt, How the Columbian Exchange Brought Globalization—And Disease. History

https://www.history.com/news/columbian-exchange-impact-diseases

Strayer, R. and Nelson, E., Ways Of The World. 3rd ed. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2016.

Groeneveld, Emma. "Women in the Viking Age." World History Encyclopedia. Last modified July 11, 2018. https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1251/women-in-the-viking-age/.

Miles, Rosalind. The Women’s History of the World. London, UK: HarperCollins Publishers, 1988.

Sara Pruitt, How the Columbian Exchange Brought Globalization—And Disease. History

https://www.history.com/news/columbian-exchange-impact-diseases

Strayer, R. and Nelson, E., Ways Of The World. 3rd ed. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2016.