28. 1950-1990 Decolonizing Women

|

Following World War II, colonies around the world fought to gain independence from the colonizers. The long journey toward decolonization involved social reform, peaceful and violent protest, and, as always, women were everywhere in this history.

|

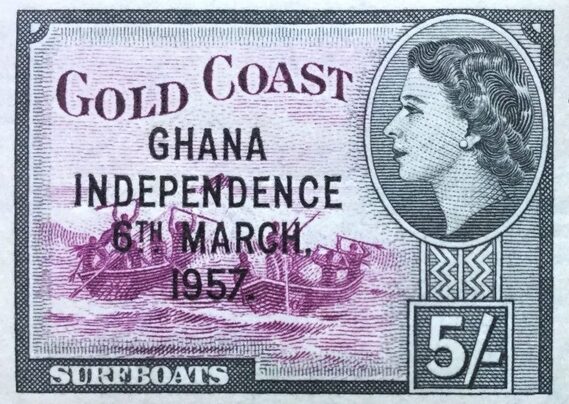

Ghana Freedom Stamp, Public Domain

Ghana Freedom Stamp, Public Domain

In the Modern era, the experiences of women across the world varied greatly depending on where the woman lived. Women in the mostly colonized Global South worked to decolonize, protect the planet, and fight poverty caused by imperialism. Women played vital roles in the decolonization movements in India and Africa, participating in various ways to challenge colonial rule and fight for independence. Their participation encompassed political engagement, activism, and intellectual contributions.

Decolonization

After World War Two, in which many colonial subjects had fought with the allies, they started demanding independence from the colonial powers. Starting in 1947 with India, 1957 with Ghana in West Afria, and into the early 1960s, almost every colonized country achieved independence. During the era of decolonization, men predominantly emerged as leaders in name in the various fights for independence. However, women were equally significant contributors to this struggle. Behind an influential male leader, there was often a strong and resilient woman. These women were well-educated, knowledgeable about European culture, and acutely aware of the disparity between its professed values and its practices. They challenged the notion that colonial rule was beneficial for their people's progress and fought for their rights and independence.

Education played a crucial role in the decolonization process, and women recognized its transformative power. They actively supported and participated in educational initiatives, particularly through government and missionary schools. By doing so, they helped bridge the cultural divide between those who had mastered the ways of their rulers and those who had not. They advocated for equal access to education for all, breaking down barriers and empowering individuals, especially women, to actively participate in the decolonization movement.

Across the Global South, formal efforts toward independence began in some form or another throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, but most were successful in achieving independence following World War II. The war illustrated the moral failings of colonizers, their inability to protect their colonies, and empowered bitter colonies to resist. Wherever these efforts took root, women enabled the process.

Decolonization

After World War Two, in which many colonial subjects had fought with the allies, they started demanding independence from the colonial powers. Starting in 1947 with India, 1957 with Ghana in West Afria, and into the early 1960s, almost every colonized country achieved independence. During the era of decolonization, men predominantly emerged as leaders in name in the various fights for independence. However, women were equally significant contributors to this struggle. Behind an influential male leader, there was often a strong and resilient woman. These women were well-educated, knowledgeable about European culture, and acutely aware of the disparity between its professed values and its practices. They challenged the notion that colonial rule was beneficial for their people's progress and fought for their rights and independence.

Education played a crucial role in the decolonization process, and women recognized its transformative power. They actively supported and participated in educational initiatives, particularly through government and missionary schools. By doing so, they helped bridge the cultural divide between those who had mastered the ways of their rulers and those who had not. They advocated for equal access to education for all, breaking down barriers and empowering individuals, especially women, to actively participate in the decolonization movement.

Across the Global South, formal efforts toward independence began in some form or another throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, but most were successful in achieving independence following World War II. The war illustrated the moral failings of colonizers, their inability to protect their colonies, and empowered bitter colonies to resist. Wherever these efforts took root, women enabled the process.

Yaa Asantewaa, Public Domain

Yaa Asantewaa, Public Domain

Decolonization of the Ashanti Empire

Yaa Asantewaa was the queen mother of Ejisu in the Ashanti Empire – now part of modern-day Ghana. In 1900 she led the Ashanti war known as the War of the Golden Stool, also known as the Yaa Asantewaa War, against British colonialism. She died in 1921, leaving a legacy as a successful farmer, an intellectual, a politician, human right activist, queen, mother and a military leader.

Ashanti is a southern region of modern Ghana, named after the clans of Ashanti people who had formed their own kingdom in 1670. The region had grown rich and powerful, trading gold and slaves with the British, Dutch and Danes. When Yaa Asantewaa was born in 1840, the British had assumed control of the other European’s Gold Coast forts. By 1870, they had ransacked the Ashanti capital, building their own palace to rival the king’s and demanding huge taxes of the Ashanti people.

During her brother's reign, Yaa Asantewaa saw the Ashanti Confederacy go through a series of events that threatened its future, including civil war from 1883 to 1888. After the King was deported, the British governor-general of the Gold Coast demanded the Golden Stool, the symbol of the Asante nation and their most prized possession. This request led to a secret meeting of the remaining members of the Asante government to discuss how to secure the return of their king and avoid surrendering the stool and with it their independence. There was a disagreement on how to go about this. Yaa Asantewaa was the Guardian of the Golden Stool at this time and she addressed the meeting with her now famous speech:

“How can a proud and brave people like the Asante sit back and look while white men took away their king and chiefs, and humiliated them with a demand for the Golden Stool. The Golden Stool only means money to the white men; they have searched and dug everywhere for it. I shall not pay one predwan to the governor. If you, the chiefs of Asante, are going to behave like cowards and not fight, you should exchange your loincloths for my undergarments.” For added emphasis, she seized a gun and shot it in front of the men.

The men were suitably roused, and Yaa Asantewaa was chosen by a number of regional Asante kings to be the war-leader of the Asante fighting force. This is the first and only example for a woman to be given that role in Asante history. The Ashanti-British War of the Golden Stool – also known as the "Yaa Asantewaa War"– was led by Queen Mother Nana Yaa Asantewaa with an army of 5,000.

She proved an effective leader, ordering each village to build a defensive stockade and winning back the capital by siege – preventing British troops receiving their supplies. Beginning in March 1900, the rebellion laid siege to the fort at Kumasi where the British had sought refuge. The fort still stands today as the Kumasi Fort and Military Museum. After several months, the Gold Coast governor eventually sent a force of 1,400 to quell the rebellion. Thus, her success was at an end. In 1901, the British overwhelmed the 5000 Ashanti troops and won the War of the Golden Stool.

During the fighting, Queen Yaa Asantewaa and her advisers were captured and sent into exile to the Seychelles. The rebellion was the final war in the Anglo-Asante wars. Following World War II, in 1957, Queen Yaa Asantewaa’s dream for an Asante free of British rule was realized. Asante was incorporated into Ghana. Ghana was the first African nation in Sub-Saharan Africa to achieve this feat.

Yaa Asantewaa's call upon the women of the Asante Empire was based on the political obligations of Akan women and their respective roles in legislative and judicial processes. The hierarchy of male stools among the Akan people was complemented by female counterparts. Within the village, elders who were heads of the matrilineages, constituted the village council known as the ôdekuro. The women were responsible for looking after women's affairs. For every ôdekuro, an ôbaa panyin acted as the responsible party for the affairs of the women of the village and served as a member of the village council. The head of a division, the ôhene, and the head of the autonomous political community, the Amanhene, had their female counterparts known as the ôhemaa: a female ruler who sat on their councils. Female stool occupants participated not only in the judicial and legislative processes, but also in the making and unmaking of war, and the distribution of land.

The experience of seeing a woman serving as political and military head of an empire was foreign to British colonial troops in 19th-century Africa, showing how the supposedly “savage” Africans were actually ahead of British “civilization” in many ways. “The woman who fights before cannons/You have accomplished great things/You have done well.”

Yaa Asantewaa remains a much-loved figure in Asante history and the history of Ghana as a whole for her role in confronting the colonialism of the British. She is a great example of why the stereotype of both women and of colonized nations as weak people who will simply roll over to more “dominant” forces is wrong. Not only did she and her women show more bravery and effectiveness than her male warriors in preparing to fight the battle, she also shows how passionately Africans resisted British imperialism and how both colonization and decolonization are gradual processes with pressure on both sides.

Yaa Asantewaa was the queen mother of Ejisu in the Ashanti Empire – now part of modern-day Ghana. In 1900 she led the Ashanti war known as the War of the Golden Stool, also known as the Yaa Asantewaa War, against British colonialism. She died in 1921, leaving a legacy as a successful farmer, an intellectual, a politician, human right activist, queen, mother and a military leader.

Ashanti is a southern region of modern Ghana, named after the clans of Ashanti people who had formed their own kingdom in 1670. The region had grown rich and powerful, trading gold and slaves with the British, Dutch and Danes. When Yaa Asantewaa was born in 1840, the British had assumed control of the other European’s Gold Coast forts. By 1870, they had ransacked the Ashanti capital, building their own palace to rival the king’s and demanding huge taxes of the Ashanti people.

During her brother's reign, Yaa Asantewaa saw the Ashanti Confederacy go through a series of events that threatened its future, including civil war from 1883 to 1888. After the King was deported, the British governor-general of the Gold Coast demanded the Golden Stool, the symbol of the Asante nation and their most prized possession. This request led to a secret meeting of the remaining members of the Asante government to discuss how to secure the return of their king and avoid surrendering the stool and with it their independence. There was a disagreement on how to go about this. Yaa Asantewaa was the Guardian of the Golden Stool at this time and she addressed the meeting with her now famous speech:

“How can a proud and brave people like the Asante sit back and look while white men took away their king and chiefs, and humiliated them with a demand for the Golden Stool. The Golden Stool only means money to the white men; they have searched and dug everywhere for it. I shall not pay one predwan to the governor. If you, the chiefs of Asante, are going to behave like cowards and not fight, you should exchange your loincloths for my undergarments.” For added emphasis, she seized a gun and shot it in front of the men.

The men were suitably roused, and Yaa Asantewaa was chosen by a number of regional Asante kings to be the war-leader of the Asante fighting force. This is the first and only example for a woman to be given that role in Asante history. The Ashanti-British War of the Golden Stool – also known as the "Yaa Asantewaa War"– was led by Queen Mother Nana Yaa Asantewaa with an army of 5,000.

She proved an effective leader, ordering each village to build a defensive stockade and winning back the capital by siege – preventing British troops receiving their supplies. Beginning in March 1900, the rebellion laid siege to the fort at Kumasi where the British had sought refuge. The fort still stands today as the Kumasi Fort and Military Museum. After several months, the Gold Coast governor eventually sent a force of 1,400 to quell the rebellion. Thus, her success was at an end. In 1901, the British overwhelmed the 5000 Ashanti troops and won the War of the Golden Stool.

During the fighting, Queen Yaa Asantewaa and her advisers were captured and sent into exile to the Seychelles. The rebellion was the final war in the Anglo-Asante wars. Following World War II, in 1957, Queen Yaa Asantewaa’s dream for an Asante free of British rule was realized. Asante was incorporated into Ghana. Ghana was the first African nation in Sub-Saharan Africa to achieve this feat.

Yaa Asantewaa's call upon the women of the Asante Empire was based on the political obligations of Akan women and their respective roles in legislative and judicial processes. The hierarchy of male stools among the Akan people was complemented by female counterparts. Within the village, elders who were heads of the matrilineages, constituted the village council known as the ôdekuro. The women were responsible for looking after women's affairs. For every ôdekuro, an ôbaa panyin acted as the responsible party for the affairs of the women of the village and served as a member of the village council. The head of a division, the ôhene, and the head of the autonomous political community, the Amanhene, had their female counterparts known as the ôhemaa: a female ruler who sat on their councils. Female stool occupants participated not only in the judicial and legislative processes, but also in the making and unmaking of war, and the distribution of land.

The experience of seeing a woman serving as political and military head of an empire was foreign to British colonial troops in 19th-century Africa, showing how the supposedly “savage” Africans were actually ahead of British “civilization” in many ways. “The woman who fights before cannons/You have accomplished great things/You have done well.”

Yaa Asantewaa remains a much-loved figure in Asante history and the history of Ghana as a whole for her role in confronting the colonialism of the British. She is a great example of why the stereotype of both women and of colonized nations as weak people who will simply roll over to more “dominant” forces is wrong. Not only did she and her women show more bravery and effectiveness than her male warriors in preparing to fight the battle, she also shows how passionately Africans resisted British imperialism and how both colonization and decolonization are gradual processes with pressure on both sides.

Indira Gandhi, Wikimedia Commons

Indira Gandhi, Wikimedia Commons

Decolonization of India

After World War I ended in 1919, Indian leaders began fighting for freedom from Great Britain. India had two major ethnic groups: Hindus, who were the majority, and Muslims, who were the minority. While many Hindus wanted a united India after British rule, some Muslims, especially leader Muhammad Ali Jinnah, were concerned about being a minority in a majority Hindu nation. In 1947, Lord “Dickie” Mountbatten, the last viceroy of India and cousin to the king of England arrived in India to settle the exit plan. Prime Minister Clement Attlee and his cabinet set a deadline for Mountbatten until June 1948 to facilitate an agreement between the major political party leaders in India, aiming for collaboration within a unified federation. The state of affairs became increasingly hostile and Mountbatten abandoned this last opportunity for the British Imperial Raj to leave India as a single, independent government. Instead, he opted to follow the desires of Muhammad Ali Jinnah and divide British India into separate dominions of India and Pakistan. The quick decision and poorly drawn partition lines in North India's significant provinces, Punjab and Bengal, cut through homelands of millions of people whose communal and familial lines could not be divided so easily.

Mountbatten’s wife Edwina played an interesting role in partition. She had an affair with Jawaharlal Nehru, the first prime minister of independent India and leader of the independence efforts. They affair played a significant role in history as Edwina convinced Nehru to accept dominion status for India in 1947, speeding up the process. Their affair continued long after the Mountbattens returned to England.

For Indian women, division led to millions of deaths due to communal violence as people moved to the correct side of the border. Women, with limited power, suffered greatly from gender-based violence. Sikh women, whose religion was not given a designated land, were tragically killed by their own relatives to prevent them from adopting a different religion. Other women, facing pressure and with little control, might have taken their own lives. Widespread sexual assault occurred during the Partition, including rapes, public humiliation, mutilation, and marking of bodies with opposing religious symbols.

In one tragic incident in Thoa Khalsa village, around ninety women jumped into a well in March 1947 to avoid confrontation with the enemy. For some, it may have been a personal decision, but others might have felt compelled due to the unique circumstances.

Later on, women who survived the violence were denied agency during the Central Recovery Operation (1948–1956) by the governments of India and Pakistan. This operation aimed to return abducted women to their families, but some had already converted, married, and built new lives. Unfortunately, their return may have not been desired.

Almost a decade later, Jawaharlal Nehru’s daughter, Indira Priyadarshini Gandhi, became the first female prime minister of India, serving for three consecutive terms (1966–77) and a fourth term from 1980 until she was assassinated in 1984. Throughout Gandhi’s reign, India continued to grapple with poverty, pluralism, inequality of wealth and education, and continuing provincial and communal violence. The worst violence erupted in Punjab.

It has been said that “Indira Gandhi’s “soft-spoken, attractive personality masked her iron will and autocratic ambition, and most of her Congress contemporaries underestimated her drive and tenacity.” While it is not unusual for men to underestimate the political acumen of women, Indira proved one of the most influential Indian leaders – for better or for worse. Gandhi undoubtedly made history by becoming the first female leader of her independent nation. She appeared to defeat (seemingly) more conservative branches of governments, improved the economy (albeit at a high cost to public well-being) and led India to decisive victories in (somewhat controversial but nonetheless widely celebrated) wars abroad.

However, Gandhi’s initial promise as a pioneering feminist icon was dampened by policies which increasingly punished the most vulnerable in society and abused their power at the expense of the lives of their own citizens. Gandhi’s troubling policies of forced sterilization of certain women in her society is a paradoxical degradation of her fellow women despite her own feminist achievements. Her disastrous role in the 1984 anti-Sikh riots will always caste a dark shadow over her reign (and one which eventually led to her assassination in 1984). However, India is (at least according to recent statistics on women’s education, employment, and domestic violence) the most patriarchal society in the world, so Gandhi deserves some credit for rising above the gender norms of her society and achieving a feat which at the time even women in supposedly more progressive Western countries had not achieved. Perhaps India’s conflict between the worshiping empowerment and patriarchal degradation of women is perfectly embodied in the figure of Indira Gandhi. Today, she is a controversial and complex figure, but she undoubtedly deserves her place as one of history’s most influential female politicians.

After World War I ended in 1919, Indian leaders began fighting for freedom from Great Britain. India had two major ethnic groups: Hindus, who were the majority, and Muslims, who were the minority. While many Hindus wanted a united India after British rule, some Muslims, especially leader Muhammad Ali Jinnah, were concerned about being a minority in a majority Hindu nation. In 1947, Lord “Dickie” Mountbatten, the last viceroy of India and cousin to the king of England arrived in India to settle the exit plan. Prime Minister Clement Attlee and his cabinet set a deadline for Mountbatten until June 1948 to facilitate an agreement between the major political party leaders in India, aiming for collaboration within a unified federation. The state of affairs became increasingly hostile and Mountbatten abandoned this last opportunity for the British Imperial Raj to leave India as a single, independent government. Instead, he opted to follow the desires of Muhammad Ali Jinnah and divide British India into separate dominions of India and Pakistan. The quick decision and poorly drawn partition lines in North India's significant provinces, Punjab and Bengal, cut through homelands of millions of people whose communal and familial lines could not be divided so easily.

Mountbatten’s wife Edwina played an interesting role in partition. She had an affair with Jawaharlal Nehru, the first prime minister of independent India and leader of the independence efforts. They affair played a significant role in history as Edwina convinced Nehru to accept dominion status for India in 1947, speeding up the process. Their affair continued long after the Mountbattens returned to England.

For Indian women, division led to millions of deaths due to communal violence as people moved to the correct side of the border. Women, with limited power, suffered greatly from gender-based violence. Sikh women, whose religion was not given a designated land, were tragically killed by their own relatives to prevent them from adopting a different religion. Other women, facing pressure and with little control, might have taken their own lives. Widespread sexual assault occurred during the Partition, including rapes, public humiliation, mutilation, and marking of bodies with opposing religious symbols.

In one tragic incident in Thoa Khalsa village, around ninety women jumped into a well in March 1947 to avoid confrontation with the enemy. For some, it may have been a personal decision, but others might have felt compelled due to the unique circumstances.

Later on, women who survived the violence were denied agency during the Central Recovery Operation (1948–1956) by the governments of India and Pakistan. This operation aimed to return abducted women to their families, but some had already converted, married, and built new lives. Unfortunately, their return may have not been desired.

Almost a decade later, Jawaharlal Nehru’s daughter, Indira Priyadarshini Gandhi, became the first female prime minister of India, serving for three consecutive terms (1966–77) and a fourth term from 1980 until she was assassinated in 1984. Throughout Gandhi’s reign, India continued to grapple with poverty, pluralism, inequality of wealth and education, and continuing provincial and communal violence. The worst violence erupted in Punjab.

It has been said that “Indira Gandhi’s “soft-spoken, attractive personality masked her iron will and autocratic ambition, and most of her Congress contemporaries underestimated her drive and tenacity.” While it is not unusual for men to underestimate the political acumen of women, Indira proved one of the most influential Indian leaders – for better or for worse. Gandhi undoubtedly made history by becoming the first female leader of her independent nation. She appeared to defeat (seemingly) more conservative branches of governments, improved the economy (albeit at a high cost to public well-being) and led India to decisive victories in (somewhat controversial but nonetheless widely celebrated) wars abroad.

However, Gandhi’s initial promise as a pioneering feminist icon was dampened by policies which increasingly punished the most vulnerable in society and abused their power at the expense of the lives of their own citizens. Gandhi’s troubling policies of forced sterilization of certain women in her society is a paradoxical degradation of her fellow women despite her own feminist achievements. Her disastrous role in the 1984 anti-Sikh riots will always caste a dark shadow over her reign (and one which eventually led to her assassination in 1984). However, India is (at least according to recent statistics on women’s education, employment, and domestic violence) the most patriarchal society in the world, so Gandhi deserves some credit for rising above the gender norms of her society and achieving a feat which at the time even women in supposedly more progressive Western countries had not achieved. Perhaps India’s conflict between the worshiping empowerment and patriarchal degradation of women is perfectly embodied in the figure of Indira Gandhi. Today, she is a controversial and complex figure, but she undoubtedly deserves her place as one of history’s most influential female politicians.

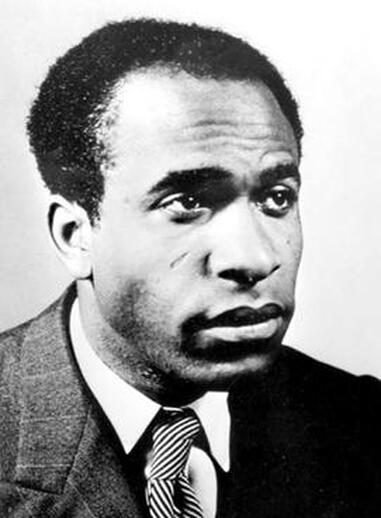

Frantz Fanon, Public Domain

Frantz Fanon, Public Domain

Decolonization of North Africa

Back in Africa, battles for decolonization continued. The end of World War II was widely celebrated. For those proudly waving French flags in the streets of Paris, the surrender of Germany’s armed forces meant that freedom from fascist violence and repression was their new reality. Press photographers captured flocks of French women smothering a soldier with kisses, or proudly donning dresses made up of red, white, and blue fabric—colors representing the land of Liberté, égalité, fraternité [Liberty, Equality, Fraternity] and its victorious allies: the United States, United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union. Countless published images from this day show crowds of beaming faces holding up issues of Libres and L’Humanité with headlines that read “Victoire! L’Allemagne Hitlérienne a capitule sans conditions!” [Victory! Hitler’s Germany Surrendered without Conditions!]

Across the Mediterranean and not photographed by press on VE day, however, were less commemorative Algerians, Tunisians, and Morroccans, many of whom were soldiers in European campaigns against fascism, protesting French colonial rule over their country.

In the small towns of Sétif and Guelma, thousands of Algerian men, women, and children took to the streets and marched in the town centers. In Oran and Algiers, clashes broke out between marchers and the police. While wreaths were placed on local war memorials and banners of the Allied countries were held high in France, Algerians waved handmade flags with a red star and crescent placed on a green and white background – a design unique to the struggle of liberation. Voices shouting “Long live free and independent Algeria!’ and choruses of Min Djibalina [From Our Mountains], echoed throughout the colonized land, demanding the attention of their colonial oppressor.[1] When French police ordered Algerians to take down flags and cease marching, scuffles between groups quickly escalated to deadly shots fired by authorities. In response, emotionally charged protestors attacked European businesses and homes, and riots continued for hours.

Tensions continued over the following weeks and months and anticolonial activists were met with State slaughters across the entire Constantine region and its countryside (Fig. 1.5). French army forces and civilian militias composed of Europeans deliberately targeted Algerian nationalists to dampen the insurgence of the resistance following the end of WWII. Because of the violence, 102 Europeans' lives were lost, but several thousands of Algerians.[2] Indeed dwarfed those numbers, as nationalist leader and historian Mohamed Harbi pithily stated: The Algerian War began 8 May 1945.[3]

This occurrence of Algerian resistance met with French State backlash is not exceptional. In the years preceding 1945, and with little to no avail, French nationals who allied with notoriously xenophobic and anti-Semitic Vichy France attempted to convince Algerians to collaborate and accept citizenship.[4] When the progressive switch of governance was made from Vichy collaborationists to the authority of the Free French after the Nazi regime, most Algerians remained apprehensive and recognized the French as universally Islamophobic and imperialist.

Taking advantage of the disorder caused by WWII, Algerian activists used the shifts of power in France as a catalyst for declaring an all-out war and the creation of new resistance factions. As the new French political administration did not seem to function any differently than the now condemned Vichy regime, anti-colonialist organizations and Muslim feminist groups, some with the support of European women activists, deliberately emerged to address new issues of religion, education, and societal roles facing Algerian women.

Women’s views and roles during the fight for Independence are historically undermined because of the initial dominance of masculine ideology, yet their participation in the war's ending was integral. Made famous by Frantz Fanon and Pontecorvo’s film The Battle of Algiers (1966), women combatants or moudjahidines joined the armed resistance of the FLN. While women’s liberation was secondary to the FLN’s achieving independence, gender played an important role in carrying out acts of resistance. Fanon describes how wearing the veil, or haïk, was a tool of warfare. It served as a symbol of protecting religious customs native to Muslim Algerians in an increasingly Islamophobic colonial regime. Fanon praised the haïk for its revolutionary value as it allowed moudjahidates to smuggle bombs and travel unnoticed by French soldiers in the Casbah, the city center of Algiers. Yet, even with these new roles, women were expected to preserve traditional moral standards. While men’s efforts in the war were given a platform and voice, women created their own inventions of selfhood and survival.

Similar patterns played out in Morocco. Many women participated actively in the 1953-56 armed resistance. In oral histories, Moroccan women recall missions they went on for the resistance effort. One woman explained that she regularly transported category seven weapons. Another described how her loose clothing enabled her to hide weapons and that due to emphasis in Muslim culture on modesty, women’s bodies were rarely searched. They also smuggled messages for the resistance, sometimes to male leadership in prison.

Back in Africa, battles for decolonization continued. The end of World War II was widely celebrated. For those proudly waving French flags in the streets of Paris, the surrender of Germany’s armed forces meant that freedom from fascist violence and repression was their new reality. Press photographers captured flocks of French women smothering a soldier with kisses, or proudly donning dresses made up of red, white, and blue fabric—colors representing the land of Liberté, égalité, fraternité [Liberty, Equality, Fraternity] and its victorious allies: the United States, United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union. Countless published images from this day show crowds of beaming faces holding up issues of Libres and L’Humanité with headlines that read “Victoire! L’Allemagne Hitlérienne a capitule sans conditions!” [Victory! Hitler’s Germany Surrendered without Conditions!]

Across the Mediterranean and not photographed by press on VE day, however, were less commemorative Algerians, Tunisians, and Morroccans, many of whom were soldiers in European campaigns against fascism, protesting French colonial rule over their country.

In the small towns of Sétif and Guelma, thousands of Algerian men, women, and children took to the streets and marched in the town centers. In Oran and Algiers, clashes broke out between marchers and the police. While wreaths were placed on local war memorials and banners of the Allied countries were held high in France, Algerians waved handmade flags with a red star and crescent placed on a green and white background – a design unique to the struggle of liberation. Voices shouting “Long live free and independent Algeria!’ and choruses of Min Djibalina [From Our Mountains], echoed throughout the colonized land, demanding the attention of their colonial oppressor.[1] When French police ordered Algerians to take down flags and cease marching, scuffles between groups quickly escalated to deadly shots fired by authorities. In response, emotionally charged protestors attacked European businesses and homes, and riots continued for hours.

Tensions continued over the following weeks and months and anticolonial activists were met with State slaughters across the entire Constantine region and its countryside (Fig. 1.5). French army forces and civilian militias composed of Europeans deliberately targeted Algerian nationalists to dampen the insurgence of the resistance following the end of WWII. Because of the violence, 102 Europeans' lives were lost, but several thousands of Algerians.[2] Indeed dwarfed those numbers, as nationalist leader and historian Mohamed Harbi pithily stated: The Algerian War began 8 May 1945.[3]

This occurrence of Algerian resistance met with French State backlash is not exceptional. In the years preceding 1945, and with little to no avail, French nationals who allied with notoriously xenophobic and anti-Semitic Vichy France attempted to convince Algerians to collaborate and accept citizenship.[4] When the progressive switch of governance was made from Vichy collaborationists to the authority of the Free French after the Nazi regime, most Algerians remained apprehensive and recognized the French as universally Islamophobic and imperialist.

Taking advantage of the disorder caused by WWII, Algerian activists used the shifts of power in France as a catalyst for declaring an all-out war and the creation of new resistance factions. As the new French political administration did not seem to function any differently than the now condemned Vichy regime, anti-colonialist organizations and Muslim feminist groups, some with the support of European women activists, deliberately emerged to address new issues of religion, education, and societal roles facing Algerian women.

Women’s views and roles during the fight for Independence are historically undermined because of the initial dominance of masculine ideology, yet their participation in the war's ending was integral. Made famous by Frantz Fanon and Pontecorvo’s film The Battle of Algiers (1966), women combatants or moudjahidines joined the armed resistance of the FLN. While women’s liberation was secondary to the FLN’s achieving independence, gender played an important role in carrying out acts of resistance. Fanon describes how wearing the veil, or haïk, was a tool of warfare. It served as a symbol of protecting religious customs native to Muslim Algerians in an increasingly Islamophobic colonial regime. Fanon praised the haïk for its revolutionary value as it allowed moudjahidates to smuggle bombs and travel unnoticed by French soldiers in the Casbah, the city center of Algiers. Yet, even with these new roles, women were expected to preserve traditional moral standards. While men’s efforts in the war were given a platform and voice, women created their own inventions of selfhood and survival.

Similar patterns played out in Morocco. Many women participated actively in the 1953-56 armed resistance. In oral histories, Moroccan women recall missions they went on for the resistance effort. One woman explained that she regularly transported category seven weapons. Another described how her loose clothing enabled her to hide weapons and that due to emphasis in Muslim culture on modesty, women’s bodies were rarely searched. They also smuggled messages for the resistance, sometimes to male leadership in prison.

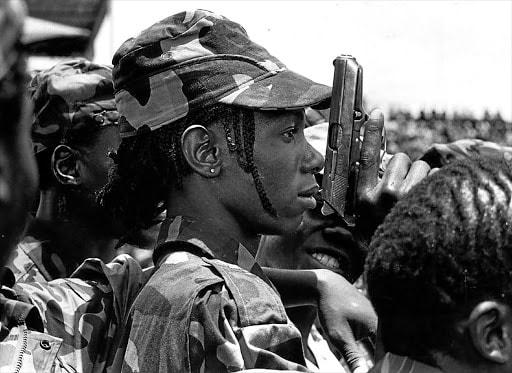

Unnamed woman in the Umkhonto we Sizwe, Public Domain

Unnamed woman in the Umkhonto we Sizwe, Public Domain

Decolonization of South Africa

Further south, in the nation of South Africa desires for independence had long been brewing. South Africa was colonized first by the Dutch East India Company from 1652, and permanently by the British from 1806. After the Anglo Boer War, the British gave South Africa dominion status as The Union of South Africa, in which political rights were given to White men. . Apartheid was instituted after World War Two, in 1948, and a system of political, social and economic oppression was instituted. The Apartheid government declared independence in 1961, as the Republic of South Africa. South Africa rejoined the British Commonwealth after Nelson Mandela became president of a democratic South Africa in 1994.

The development of mining in South Africa from the late nineteenth century, and later segregation and apartheid devastated African families. In rural areas, men moved to work on the gold and diamond mines in the cities, and women were left to manage the homestead. Policies forbade African women to move to the cities unless they worked for white households. Most stayed in the ever more poorer rural areas looking after the children, working in fields to produce food for the family, and spending a significant amount of time fetching water since rural villages lacked a water supply.

When food became scarce in rural areas, many women had to move to cities in search of work, leaving their children with grandmothers. Poverty played a major role in transforming their identity from mothers and caregivers to workers in cities where they were not welcomed.

In cities, women faced discrimination from white government authorities who opposed their permanent presence. The government viewed them as a threat to their vision of temporary black labor in urban areas. Life for women in cities was a struggle, but they managed to carve out a place for themselves, often finding informal work such as washing or selling goods. Some resorted to illegal activities like brewing beer to make ends meet.

The 1960s brought significant changes to Africa. While many African countries challenged and overthrew colonial rule, the white government in South Africa tightened its control over the black population.

Despite unjust pass laws, Black people, including through organizations like African National Congress (ANC) and the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC), protested against them. The Sharpeville Massacre in 1960 was a pivotal moment in the fight against apartheid, leading to a state of emergency, ANC and PAC bans, and an armed struggle against the apartheid government. In 1961, male leaders in independence organizations were arrested and charged with treason, and in 1963, prominent figures like Nelson Mandela were sentenced to life imprisonment, effectively silencing them.

Women like Frene Ginwala, Dorothy Nyembe, Ruth First, and Winnie Madikizela-Mandela played crucial roles in the anti-apartheid struggle. Ginwala assisted in organizing Oliver Tambo's departure and contributed to the ANC's external mission in Tanzania. Dorothy Nyembe, dedicated to the anti-apartheid struggle, faced harsh treatment during imprisonment. Ruth First faced detention and exile after the Sharpeville Massacre, and was ultimately assassinated by the Apartheid government in 1982. Nelson Mandela is a prominent figure in the struggle against apartheid in South Africa, yet he owed much of his success to the support of his wife, Winnie Madikizela-Mandela. She played an instrumental role in mobilizing support, providing solace to families affected by apartheid, and amplifying the voices of the oppressed. She endured years of confinement and played a significant role in the ANC Women's League. Her legacy was tainted through her calls to set collaborators on fire and being implicated in the murder of teenager Stompie Moketsi in the mid 1980s. In the 1990s, Archbishop Desmond Tutu begged her to apologize to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Gender double standard remain: no male politician was asked to apologize in the same way. These women’s resilience and courage, along with the contributions of countless other women, were essential in dismantling the oppressive regime and paving the way for a more inclusive South Africa.

Speaking to the spirit of women independence fighters, Florence Maleka said, "Women of South Africa, we pledge ourselves to intensify the struggle until apartheid has been eradicated, until the last bastion of colonialism and imperialism on the African continent has been overthrown and until South Africa is a free, democratic, non-racist and non-sexist country that truly belongs to all who live in it"

Women increasingly joined Umkhonto we Sizwe, fighting alongside men in the armed revolutionary struggle. The United Democratic Front (UDF) was formed on August 20, 1983, advocating for non-racialism and supporting the ideals of the Freedom Charter. Women played a central role in UDF structures and campaigns at every level. Women such as Cheryl Carolus and Amy Thornton galvanized the youth and helped create intergenerational and wide civic alliances. Albertina Sisulu was elected as one of the three co-presidents, even while in jail at the time. The UDF Women's Congress addressed discrimination and prejudices against women, fighting against the patriarchal society's power dynamics where women were treated as second-class citizens, expected to fulfill specific roles and often subjected to domestic violence without recourse to justice.

Further south, in the nation of South Africa desires for independence had long been brewing. South Africa was colonized first by the Dutch East India Company from 1652, and permanently by the British from 1806. After the Anglo Boer War, the British gave South Africa dominion status as The Union of South Africa, in which political rights were given to White men. . Apartheid was instituted after World War Two, in 1948, and a system of political, social and economic oppression was instituted. The Apartheid government declared independence in 1961, as the Republic of South Africa. South Africa rejoined the British Commonwealth after Nelson Mandela became president of a democratic South Africa in 1994.

The development of mining in South Africa from the late nineteenth century, and later segregation and apartheid devastated African families. In rural areas, men moved to work on the gold and diamond mines in the cities, and women were left to manage the homestead. Policies forbade African women to move to the cities unless they worked for white households. Most stayed in the ever more poorer rural areas looking after the children, working in fields to produce food for the family, and spending a significant amount of time fetching water since rural villages lacked a water supply.

When food became scarce in rural areas, many women had to move to cities in search of work, leaving their children with grandmothers. Poverty played a major role in transforming their identity from mothers and caregivers to workers in cities where they were not welcomed.

In cities, women faced discrimination from white government authorities who opposed their permanent presence. The government viewed them as a threat to their vision of temporary black labor in urban areas. Life for women in cities was a struggle, but they managed to carve out a place for themselves, often finding informal work such as washing or selling goods. Some resorted to illegal activities like brewing beer to make ends meet.

The 1960s brought significant changes to Africa. While many African countries challenged and overthrew colonial rule, the white government in South Africa tightened its control over the black population.

Despite unjust pass laws, Black people, including through organizations like African National Congress (ANC) and the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC), protested against them. The Sharpeville Massacre in 1960 was a pivotal moment in the fight against apartheid, leading to a state of emergency, ANC and PAC bans, and an armed struggle against the apartheid government. In 1961, male leaders in independence organizations were arrested and charged with treason, and in 1963, prominent figures like Nelson Mandela were sentenced to life imprisonment, effectively silencing them.

Women like Frene Ginwala, Dorothy Nyembe, Ruth First, and Winnie Madikizela-Mandela played crucial roles in the anti-apartheid struggle. Ginwala assisted in organizing Oliver Tambo's departure and contributed to the ANC's external mission in Tanzania. Dorothy Nyembe, dedicated to the anti-apartheid struggle, faced harsh treatment during imprisonment. Ruth First faced detention and exile after the Sharpeville Massacre, and was ultimately assassinated by the Apartheid government in 1982. Nelson Mandela is a prominent figure in the struggle against apartheid in South Africa, yet he owed much of his success to the support of his wife, Winnie Madikizela-Mandela. She played an instrumental role in mobilizing support, providing solace to families affected by apartheid, and amplifying the voices of the oppressed. She endured years of confinement and played a significant role in the ANC Women's League. Her legacy was tainted through her calls to set collaborators on fire and being implicated in the murder of teenager Stompie Moketsi in the mid 1980s. In the 1990s, Archbishop Desmond Tutu begged her to apologize to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Gender double standard remain: no male politician was asked to apologize in the same way. These women’s resilience and courage, along with the contributions of countless other women, were essential in dismantling the oppressive regime and paving the way for a more inclusive South Africa.

Speaking to the spirit of women independence fighters, Florence Maleka said, "Women of South Africa, we pledge ourselves to intensify the struggle until apartheid has been eradicated, until the last bastion of colonialism and imperialism on the African continent has been overthrown and until South Africa is a free, democratic, non-racist and non-sexist country that truly belongs to all who live in it"

Women increasingly joined Umkhonto we Sizwe, fighting alongside men in the armed revolutionary struggle. The United Democratic Front (UDF) was formed on August 20, 1983, advocating for non-racialism and supporting the ideals of the Freedom Charter. Women played a central role in UDF structures and campaigns at every level. Women such as Cheryl Carolus and Amy Thornton galvanized the youth and helped create intergenerational and wide civic alliances. Albertina Sisulu was elected as one of the three co-presidents, even while in jail at the time. The UDF Women's Congress addressed discrimination and prejudices against women, fighting against the patriarchal society's power dynamics where women were treated as second-class citizens, expected to fulfill specific roles and often subjected to domestic violence without recourse to justice.

Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, Wikimedia Commons

Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, Wikimedia Commons

African Women’s Leadership

Various societies across the continent of Africa witnessed women’s leadership as queens, as spiritual leaders, as economic leaders and as resistance fighters. Ellen Johnson Sirleaf made history in 2005 becoming president of Liberia in West Africa, andAfrica's first elected female president. Her path to power was long and arduous. She served in various financial roles under different regimes, earning a reputation for personal financial integrity. During Samuel K. Doe's military dictatorship, she faced imprisonment twice and narrowly escaped execution. In the 1985 national election, her open criticism of the military government led to arrest and a 10-year prison sentence, but she was later released and allowed to leave the country.

Exiled for twelve years, Johnson Sirleaf became an influential economist, working for international financial institutions as well as the United Nations. She returned to Liberia and played a crucial role in overseeing preparations for democratic elections.

When she finally won election, she was known as Liberia’s "Iron Lady." President Sirleaf erased nearly $5 billion in foreign debt, attracting foreign investment and increasing the annual government budget substantially. Her presidency faced challenges, including high unemployment and the aftermath of civil war from the late 1980s through 2003. Johnson Sirleaf focused on debt amelioration, securing foreign investment, and establishing a Truth and Reconciliation Committee. Despite controversies, including the fact that she rejected the recommendations from the committee's report, she was reelected in 2011. In 2011, she was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize alongside other women. The Nobel Committee noted her role in maintaining peace after the civil war and her dedication to advancing the rights and status of women as significant factors in their decision.

Economic progress continued until the Ebola outbreak in 2014, which severely impacted Liberia. In her final week in office, President Sirleaf signed an executive order on domestic violence, aiming to protect women, men, and children against various abuses. Yet, a crucial part of her proposal, the abolition of female genital mutilation (FGM) against young girls under 18, was removed, leaving Sirleaf disappointed.

In 2018, Johnson Sirleaf stepped down, handing over power to George Weah a famous soccer player. 2017 she received theIbrahim Prize for Achievement in African Leadership, recognizing her leadership during Liberia's challenging transition. The prize included financial support for charitable causes supported by Johnson Sirleaf.

Despite expectations that her presidency would pave the way for more women in politics, her departure marked a decline in women in power in Liberia, similar to the Thatcher era in the UK.

The lives of women in the Global South continue to be diverse and measured by the long history of colonialism and decolonization. Much remains to be done for women. Women’s rights are the greatest humanitarian issue of the modern era. How will the global community work together to repair the damages of colonialism? What role will women leaders play in this work?

Various societies across the continent of Africa witnessed women’s leadership as queens, as spiritual leaders, as economic leaders and as resistance fighters. Ellen Johnson Sirleaf made history in 2005 becoming president of Liberia in West Africa, andAfrica's first elected female president. Her path to power was long and arduous. She served in various financial roles under different regimes, earning a reputation for personal financial integrity. During Samuel K. Doe's military dictatorship, she faced imprisonment twice and narrowly escaped execution. In the 1985 national election, her open criticism of the military government led to arrest and a 10-year prison sentence, but she was later released and allowed to leave the country.

Exiled for twelve years, Johnson Sirleaf became an influential economist, working for international financial institutions as well as the United Nations. She returned to Liberia and played a crucial role in overseeing preparations for democratic elections.

When she finally won election, she was known as Liberia’s "Iron Lady." President Sirleaf erased nearly $5 billion in foreign debt, attracting foreign investment and increasing the annual government budget substantially. Her presidency faced challenges, including high unemployment and the aftermath of civil war from the late 1980s through 2003. Johnson Sirleaf focused on debt amelioration, securing foreign investment, and establishing a Truth and Reconciliation Committee. Despite controversies, including the fact that she rejected the recommendations from the committee's report, she was reelected in 2011. In 2011, she was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize alongside other women. The Nobel Committee noted her role in maintaining peace after the civil war and her dedication to advancing the rights and status of women as significant factors in their decision.

Economic progress continued until the Ebola outbreak in 2014, which severely impacted Liberia. In her final week in office, President Sirleaf signed an executive order on domestic violence, aiming to protect women, men, and children against various abuses. Yet, a crucial part of her proposal, the abolition of female genital mutilation (FGM) against young girls under 18, was removed, leaving Sirleaf disappointed.

In 2018, Johnson Sirleaf stepped down, handing over power to George Weah a famous soccer player. 2017 she received theIbrahim Prize for Achievement in African Leadership, recognizing her leadership during Liberia's challenging transition. The prize included financial support for charitable causes supported by Johnson Sirleaf.

Despite expectations that her presidency would pave the way for more women in politics, her departure marked a decline in women in power in Liberia, similar to the Thatcher era in the UK.

The lives of women in the Global South continue to be diverse and measured by the long history of colonialism and decolonization. Much remains to be done for women. Women’s rights are the greatest humanitarian issue of the modern era. How will the global community work together to repair the damages of colonialism? What role will women leaders play in this work?

Draw your own conclusions

|

Learn how to teach with inquiry.

Many of these lesson plans were sponsored in part by the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources Eastern Region Program, coordinated by Waynesburg University, the History and Social Studies Education Faculty at Plymouth State University, and the Patrons of the Remedial Herstory Project. |

Lesson Plans from Other Organizations

- This website, Women in World History has primary source based lesson plans on women's history in a whole range of topics. Some are free while others have a cost.

- The Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media has produced recommendations for teaching women's history with primary sources and provided a collection of sources for world history. Check them out!

- The Stanford History Education Group has a number of lesson plans about women in World History.

Unknown: A Report On The State Of Women’s Issues In Post-Communist Transition

In the countries of post-communism transition there are many similarities in the situation of women, despite the fact that these countries have different historical, economic and religious backgrounds and that their totalitarian regimes were also radically different.

The states of the so-called socialist (communist) systems, using their political and social power and propaganda, managed to cover up the depths of the inequalities in gendered opportunities. So, after the transformation, the illusion still remained that equal opportunities for women had already been established. At the same time, society was not prepared for the dramatic changes that occurred in the differences of opportunities (according to age, region, education, etc.)

During the transformation of the economy, women fell out of the labour market in great numbers to find themselves in the household, which did not provide any income for them, or in early retirement. Women's political representation radically decreased, compared to the "statist feminist" era, when their representation was regulated by quota. In the last decade, however, their proportion has increased again, especially at local levels. Non-profit organisations, representing the interests of women, were not strong enough to break through the political walls and realise their interests and programmes in political life, or to give voice to their values in public discourse, despite their strong activities in certain countries.

Therefore, the Parliamentary Assembly recommends to the governments of Central and Eastern Europe a number of measures aimed at improving legal norms on gender equality, the economic status of women in society, as well as their health and social protection.

Magdolna Kósá-Kovács. ‘The Situation of Women in the Countries of Post-Communism Transition’, 9 June 2004. https://assembly.coe.int/nw/xml/XRef/X2H-Xref- ViewHTML.asp?FileID=10366&lang=EN.

Questions:

The states of the so-called socialist (communist) systems, using their political and social power and propaganda, managed to cover up the depths of the inequalities in gendered opportunities. So, after the transformation, the illusion still remained that equal opportunities for women had already been established. At the same time, society was not prepared for the dramatic changes that occurred in the differences of opportunities (according to age, region, education, etc.)

During the transformation of the economy, women fell out of the labour market in great numbers to find themselves in the household, which did not provide any income for them, or in early retirement. Women's political representation radically decreased, compared to the "statist feminist" era, when their representation was regulated by quota. In the last decade, however, their proportion has increased again, especially at local levels. Non-profit organisations, representing the interests of women, were not strong enough to break through the political walls and realise their interests and programmes in political life, or to give voice to their values in public discourse, despite their strong activities in certain countries.

Therefore, the Parliamentary Assembly recommends to the governments of Central and Eastern Europe a number of measures aimed at improving legal norms on gender equality, the economic status of women in society, as well as their health and social protection.

Magdolna Kósá-Kovács. ‘The Situation of Women in the Countries of Post-Communism Transition’, 9 June 2004. https://assembly.coe.int/nw/xml/XRef/X2H-Xref- ViewHTML.asp?FileID=10366&lang=EN.

Questions:

- According to the report, what is the state of women’s issues?

- How have women’s rights transformed since the end of communism?

- What are some suggestions the report makes to improve the situation in post-communist countries?

Slavenka Drakulic: Excerpt from her Speech at the Institute for Human Sciences

Emancipation from above – as I call it – was the main difference between the lives of women under communism and those of women in Western democracies. Emancipatory law was built into the communist legal system, guaranteeing to women all the basic rights –from voting to property ownership, from education to divorce, from equal pay for equal work to the right to control their bodies. But, as Ulf Brunnbauer writes in his 2000 essay From equality without democracy to democracy without equality?:

“Proclamations of gender equality never corresponded to social reality. Patriarchal values and structures were not eradicated, but the ‘family patriarch’ was replaced by the authoritarian state – emancipation was not an end in itself, but an instrument for wider political goals, as defined by the party.”The formal equality of women in the communist world was observed mostly in public life and in institutions. The private sphere, on the other hand, was dominated by male chauvinism. This meant a lot of unreported domestic violence, for example. It also meant that men usually had no obligations at home, which left women with less time for themselves. It was not only the lack of freedom – and time – that prevented women fighting for changes but, more importantly, a lack of belief that change was necessary. Someone else up there was in charge of thinking about that for you. And because change came from the powers that be, women were made to believe there was no need for change or room for improvement.

If, however, there were any minor problems resulting from women’s specific needs, then

there were women’s organizations that were supposed to take care of them. However, these

were only instruments of communist party power and were concerned less with women and

their needs and more with ideology. Feminist consciousness didn’t exist. Since women were

emancipated, there was no need for a discussion about women’s rights, so the argument went. It

was as if women lived in an ideal world, but were not fully aware of it, or failed to appreciate the

fact. And those who tried to enlighten them about the real situation were seen as “suspicious

elements”. Women who attempted to publically discuss feminism in Yugoslavia in the 1980s

were accused by the authorities of “importing foreign, bourgeois ideas”.

At that time, Eastern European women speaking publicly would typically introduce

themselves by saying “I am not a feminist, but...” Of course, they were afraid of being ridiculed.

Today, one reads that numerous feminist NGOs were formed in Eastern Europe shortly after

1989, but that was not at all my experience. During my travels for the magazine Ms., trying to

find feminists was like looking for a needle in a haystack. There were good reasons for this. For a

long time, even after 1989, women in former communist countries did not want to be identified

as feminists, even if they were. If anything, to be a feminist was considered to be a kind of a

dissident. Prejudices against Western, and especially American feminists were spread by the

press; not only were they men-haters too ugly to find a husband, but they were also burning

bras!

The post-communist revival of conservative values, nationalism and religion is having an

effect on the behaviour of women not only in my small country. Their passivity and disinterest is

not hard to understand. When everything around you is changing so dramatically, then you

tend not to embrace the new circumstances, but to cling to habits, values and ideas that were

there before –before communism. Unfortunately, this means a radical backlash, the return to a

feudal value system. After the collapse of communism, most countries in the region experienced

a renaissance of nationalism and religion – precisely the two things that were suppressed under

communism. It was all that remained from the pre-communist past. Patriarchy, which seemed to

have disappeared, reared its head again, looking healthier than ever. Patriarchy after Patriarchy –

as Karl Kaser wrote. But is it only temporary?

So, for women in Eastern Europe, the freedom regained in 1989 has brought unexpected

limitations on economic, social and even reproductive rights. Women were hit by cuts in public

spending and seen as an inferior category of employee, causing mass female unemployment.

Poverty was feminized. With the political focus on economic transformation and the building of

democratic structures, women’s rights weren’t a top priority. As a result, fewer and fewer

women worked (although we now know that many, between 30 to 50 %, were part of the

informal economy). More and more stayed at home, avoiding politics and public life, being

persuaded that this was the right thing to do.

Drakulic, Slavenka., “How Women Survived Post-Communism (and didn’t Laugh)” (speech, Vienna, Austria, May 29 2015), Institute for Human Sciences. https://www.iwm.at/transit-online/how- women-survived-post-communism-and-didnt-laugh.

Questions:

“Proclamations of gender equality never corresponded to social reality. Patriarchal values and structures were not eradicated, but the ‘family patriarch’ was replaced by the authoritarian state – emancipation was not an end in itself, but an instrument for wider political goals, as defined by the party.”The formal equality of women in the communist world was observed mostly in public life and in institutions. The private sphere, on the other hand, was dominated by male chauvinism. This meant a lot of unreported domestic violence, for example. It also meant that men usually had no obligations at home, which left women with less time for themselves. It was not only the lack of freedom – and time – that prevented women fighting for changes but, more importantly, a lack of belief that change was necessary. Someone else up there was in charge of thinking about that for you. And because change came from the powers that be, women were made to believe there was no need for change or room for improvement.

If, however, there were any minor problems resulting from women’s specific needs, then

there were women’s organizations that were supposed to take care of them. However, these

were only instruments of communist party power and were concerned less with women and

their needs and more with ideology. Feminist consciousness didn’t exist. Since women were

emancipated, there was no need for a discussion about women’s rights, so the argument went. It

was as if women lived in an ideal world, but were not fully aware of it, or failed to appreciate the

fact. And those who tried to enlighten them about the real situation were seen as “suspicious

elements”. Women who attempted to publically discuss feminism in Yugoslavia in the 1980s

were accused by the authorities of “importing foreign, bourgeois ideas”.

At that time, Eastern European women speaking publicly would typically introduce

themselves by saying “I am not a feminist, but...” Of course, they were afraid of being ridiculed.

Today, one reads that numerous feminist NGOs were formed in Eastern Europe shortly after

1989, but that was not at all my experience. During my travels for the magazine Ms., trying to

find feminists was like looking for a needle in a haystack. There were good reasons for this. For a

long time, even after 1989, women in former communist countries did not want to be identified

as feminists, even if they were. If anything, to be a feminist was considered to be a kind of a

dissident. Prejudices against Western, and especially American feminists were spread by the

press; not only were they men-haters too ugly to find a husband, but they were also burning

bras!

The post-communist revival of conservative values, nationalism and religion is having an

effect on the behaviour of women not only in my small country. Their passivity and disinterest is

not hard to understand. When everything around you is changing so dramatically, then you

tend not to embrace the new circumstances, but to cling to habits, values and ideas that were

there before –before communism. Unfortunately, this means a radical backlash, the return to a

feudal value system. After the collapse of communism, most countries in the region experienced

a renaissance of nationalism and religion – precisely the two things that were suppressed under

communism. It was all that remained from the pre-communist past. Patriarchy, which seemed to

have disappeared, reared its head again, looking healthier than ever. Patriarchy after Patriarchy –

as Karl Kaser wrote. But is it only temporary?

So, for women in Eastern Europe, the freedom regained in 1989 has brought unexpected

limitations on economic, social and even reproductive rights. Women were hit by cuts in public

spending and seen as an inferior category of employee, causing mass female unemployment.

Poverty was feminized. With the political focus on economic transformation and the building of

democratic structures, women’s rights weren’t a top priority. As a result, fewer and fewer

women worked (although we now know that many, between 30 to 50 %, were part of the

informal economy). More and more stayed at home, avoiding politics and public life, being

persuaded that this was the right thing to do.

Drakulic, Slavenka., “How Women Survived Post-Communism (and didn’t Laugh)” (speech, Vienna, Austria, May 29 2015), Institute for Human Sciences. https://www.iwm.at/transit-online/how- women-survived-post-communism-and-didnt-laugh.

Questions:

- What does Slavenka Drakulic claim is the main difference between the lives of women in western societies and communist ones?

- What were some key similarities and differences between attitudes towards women’s issues in western democratic societies and in eastern european societies at the time?

- According to Drakulic, why was there a revival in conservative values after communism?

- What does this speech say about the environment towards women’s rights in eastern europe after communism?

Le Browne: Her Experience in the Diem Regime

Le Lieu Browne, a Vietnamese woman educated in France and married to an American journalist, recalls her mixed feelings about her experience working for the Diem regime.

I grew up in Ben Tre in the Mekong Delta, which was reputed to be a stronghold of Communist sympathizers. The French controlled big towns while the Viet Minh controlled the countryside. When the French tried to occupy Ben Tre with their legionnaires and Moroccans and Nigerans they were brutal. But so were the Viet Minh. If they found civil servants or "pro government elements" they took them away and we never heard from them again....

About half the students in my high school were pro-Viet Minh. They organized demonstrations and strikes which constantly closed down the school. My mother worried about our education and decided to send me, along with my twin brothers, to France.... When I returned in 1959 I worked for the Ministry of Information....I worked there for three years but I wasn't happy and wanted to get out....I strongly believed in freedom and suddenly we were ordered to wear uniforms to work and go to political meetings. It sounded to me more like Communism than democracy....

After the coup against Diem, the military generals competed with one another to take power and there was one coup after another. These Vietnamese generals had no experience in administration. They were even more corrupt than Diem...It wasn't good to have generals as presidents. They gave me no hope. But the American buildup also left me skeptical. If the French who colonized our country for a century could not win our support, how could the Americans, the newcomers with a different culture and language, hope to win the war against the Communists? We seemed to return to the situation in the fifties in which the government controlled the cities and the Viet Cong controlled the countryside. Corruption and police harassment made people distrust the government and sympathize more with the Viet Cong. But still I didn't think the Viet Cong would win. I just thought that the war would go on forever.

Appy G, Christian. Interview with Le Lieu Browne.“A South Vietnamese Woman Recalls Her Experience in the Diem Regime,” SHEC: Resources for Teachers.

Questions:

I grew up in Ben Tre in the Mekong Delta, which was reputed to be a stronghold of Communist sympathizers. The French controlled big towns while the Viet Minh controlled the countryside. When the French tried to occupy Ben Tre with their legionnaires and Moroccans and Nigerans they were brutal. But so were the Viet Minh. If they found civil servants or "pro government elements" they took them away and we never heard from them again....

About half the students in my high school were pro-Viet Minh. They organized demonstrations and strikes which constantly closed down the school. My mother worried about our education and decided to send me, along with my twin brothers, to France.... When I returned in 1959 I worked for the Ministry of Information....I worked there for three years but I wasn't happy and wanted to get out....I strongly believed in freedom and suddenly we were ordered to wear uniforms to work and go to political meetings. It sounded to me more like Communism than democracy....

After the coup against Diem, the military generals competed with one another to take power and there was one coup after another. These Vietnamese generals had no experience in administration. They were even more corrupt than Diem...It wasn't good to have generals as presidents. They gave me no hope. But the American buildup also left me skeptical. If the French who colonized our country for a century could not win our support, how could the Americans, the newcomers with a different culture and language, hope to win the war against the Communists? We seemed to return to the situation in the fifties in which the government controlled the cities and the Viet Cong controlled the countryside. Corruption and police harassment made people distrust the government and sympathize more with the Viet Cong. But still I didn't think the Viet Cong would win. I just thought that the war would go on forever.

Appy G, Christian. Interview with Le Lieu Browne.“A South Vietnamese Woman Recalls Her Experience in the Diem Regime,” SHEC: Resources for Teachers.

Questions:

- What kind of source is this?

- How might her background impact her biases?

- What were her opinions about the war?

Truong My Hoa: Her Recollection of Her Revolutionary Activities

Truong My Hoa, a Vietnamese woman from a "revolutionary tradition" and later a high-ranking member of the Communist Party, recalls her experiences as a young revolutionary and subsequent imprisonment by the South Vietnamese government.

I was born to a revolutionary family and inherited a revolutionary tradition. My hometown of Tien Giang was a revolutionary hotbed. My parents had taken part in the resistance war against the French for which both were arrested and imprisoned. My brothers and sisters and I were imprisoned during the American War. Altogether my family spent half a century in jail.

In 1954, my father regrouped to the North in compliance with the Geneva Accords. My mother remained in the South with the children, and like everybody else, she thought that general elections would be implemented two years later and the country, as well as all the families, would be reunited. However, the puppet government of Ngo Dinh Diem unilaterally carried out a bloody war, supported by American imperialists.

I began to participate in the revolution at age fifteen, in 1960, when the Saigon regime took its guillotine throughout the South to behead patriotic revolutionaries and even non- revolutionary common people. I realized in my heart that we had no alternative but to struggle against the Diem government and its henchmen. That was the only way we could achieve peace, independence, and unification. Because of Diem’s terror in the countryside, my mother took us to Saigon. There, right in the gorge of the puppet regime, I became a revolutionary. I participated in propaganda aimed at mobilizing high school and college students. We urged them to resist military conscription and the invasion of our country by American imperialists.

I was arrested on April 15, 1964. The Saigon Military Tribunal accused me of disrupting order and political stability. I was officially sentenced to eighteen months of confinement, but they kept prolonging the sentence and held me in prison for eleven years. I was released on March 7, 1975....

Over the years I underwent a lot of interrogation and torture.... Always they asked me if we were going to talk, or not, and they slandered our political loyalties. They tried to make us salute their flag and condemn Communism. They tried to make us say, 'Down with President Ho!' And, of course, they wanted to know about our revolutionary organizations and bases. But we would rather die than bow to their will.

Appy G, Christian. Interview with Truong My Hoa.“A Vietnamese Woman Recalls Her Revolutionary Activities,” SHEC: Resources for Teachers.

Questions:

I was born to a revolutionary family and inherited a revolutionary tradition. My hometown of Tien Giang was a revolutionary hotbed. My parents had taken part in the resistance war against the French for which both were arrested and imprisoned. My brothers and sisters and I were imprisoned during the American War. Altogether my family spent half a century in jail.

In 1954, my father regrouped to the North in compliance with the Geneva Accords. My mother remained in the South with the children, and like everybody else, she thought that general elections would be implemented two years later and the country, as well as all the families, would be reunited. However, the puppet government of Ngo Dinh Diem unilaterally carried out a bloody war, supported by American imperialists.

I began to participate in the revolution at age fifteen, in 1960, when the Saigon regime took its guillotine throughout the South to behead patriotic revolutionaries and even non- revolutionary common people. I realized in my heart that we had no alternative but to struggle against the Diem government and its henchmen. That was the only way we could achieve peace, independence, and unification. Because of Diem’s terror in the countryside, my mother took us to Saigon. There, right in the gorge of the puppet regime, I became a revolutionary. I participated in propaganda aimed at mobilizing high school and college students. We urged them to resist military conscription and the invasion of our country by American imperialists.

I was arrested on April 15, 1964. The Saigon Military Tribunal accused me of disrupting order and political stability. I was officially sentenced to eighteen months of confinement, but they kept prolonging the sentence and held me in prison for eleven years. I was released on March 7, 1975....

Over the years I underwent a lot of interrogation and torture.... Always they asked me if we were going to talk, or not, and they slandered our political loyalties. They tried to make us salute their flag and condemn Communism. They tried to make us say, 'Down with President Ho!' And, of course, they wanted to know about our revolutionary organizations and bases. But we would rather die than bow to their will.

Appy G, Christian. Interview with Truong My Hoa.“A Vietnamese Woman Recalls Her Revolutionary Activities,” SHEC: Resources for Teachers.

Questions:

- What kind of source is this?