7. 100 BCE - 100 CE Women and the Roman Empire

|

Roman history includes many powerful and fascinating women such as. Cleopatra, who helped to define Roman history through her relationships with Roman leaders. The wives of Roman leaders, such as Octavia and Scribonia, as well as their daughters, also played prominent roles in the Empire’s history. Women close to the emperor could manipulate him. Cleopatra was not the only ancient woman to take on male Roman rulers. Women also fought Roman expansion. Boudicca, Zenobia, and Kandake were strong women who opposed Rome. They led powerful anti-imperial forces. Both inside and outside of Rome, women played politics, fought, and led.

|

|

River valleys settlements became city states. City states became empires. The Mesopotamian Empires that had dominated ancient times dissolved into the Persian and eventually Macedonian Empire, spreading Greek culture around the Mediterranean world. The Romans eventually surpassed the Greeks and conquered most of Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa, between 500 BCE to around 500 CE. In China the first empire, Qin, known for its harsh legal rule, was replaced by the Han from 200 BCE to 200 CE. But did women live and thrive in these Empires? Were any opposed to these Empires?

Rome

Roman culture built on the Greek models that preceded it. Its polytheistic religious beliefs accounted for the renaming of most of the Greek gods with equivalent Roman names. IRome adopted most Greek ideas about medicine, philosophy, culture, and a woman’s place. Check out Founding Myths and Women’s Place to learn more about these.

The Romans also developed their own ideas. As Rome expanded, it increasingly became a warrior society where masculinity was strictly defined and men were measured on their successes as soldiers and property owners. In their private lives, this meant that Roman men had absolute control over their wives, children, and slaves. Absolute control means exactly what it sounds like, including the right to kill them without interference from anyone– not even the government. Absolute freedom became a part of the male identity. As the Empire expanded and government control seeped into people's personal lives, so did the life and death power of the (male) head of household.

Rome

Roman culture built on the Greek models that preceded it. Its polytheistic religious beliefs accounted for the renaming of most of the Greek gods with equivalent Roman names. IRome adopted most Greek ideas about medicine, philosophy, culture, and a woman’s place. Check out Founding Myths and Women’s Place to learn more about these.

The Romans also developed their own ideas. As Rome expanded, it increasingly became a warrior society where masculinity was strictly defined and men were measured on their successes as soldiers and property owners. In their private lives, this meant that Roman men had absolute control over their wives, children, and slaves. Absolute control means exactly what it sounds like, including the right to kill them without interference from anyone– not even the government. Absolute freedom became a part of the male identity. As the Empire expanded and government control seeped into people's personal lives, so did the life and death power of the (male) head of household.

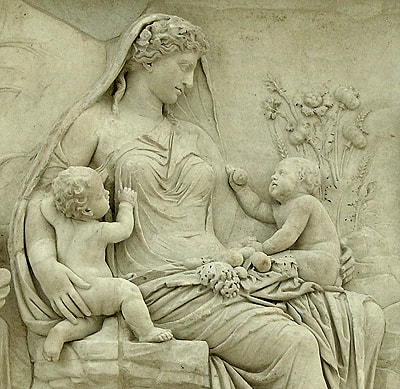

Roman Motherhood, Public Domain

Roman Motherhood, Public Domain

Women participated in this warrior culture by raising brave sons and passing on the values of the warrior state to their children. Roman mothers, like the Spartans before them, were known to tell their sons going off to war, "Return with your shield or on it.”

Rome’s endless conquests also meant that hundreds of thousands of women and men were brought into the empire as slaves. Female slaves did domestic work, worked in brothels, were dancers, actresses, and were sometimes used for sex by their male owners. Slavery was deeply embedded in the culture of Rome as punishment from the gods..

Despite the persistent belief that women should not be educated, upper class Roman women capitalized on the need to build strong and educated warriors to justify their own educations as mothers and future wives of military leaders. In order to protect family fortunes, elite women were sometimes married off without transferring legal control of property to their husbands.This allowed those women to manage their own fortunes. However, the legal control of women’s property frequently remained with their father or male guardian. During the reign of Augustus, he passed a law that stated free-born women who bore three or more children were free from guardianship. Otherwise women were under the control of men.

Little changed for the average Roman woman. Ordinary women were educated just enough to serve the home and rear their children. Male contemporaries remained staunchly opposed to women’s education. Titus Livy, one of the first Roman historians, stated, “a woman’s mind is influenced by little things.” Publius Syrus said, “A woman who meditates alone meditates evil.” Another wrote his misogyny in a poem, “But out of all plagues, the greatest is untold; the book learned wife, in Greek and Latin bold.” If the scholars of the era held such derogatory views of women, there was little possibility for training, recognition, and archiving of female achievements.

Yet we do know about some women, notably the most elite of elite women. Their power or proximity to power meant that their lives and stories would be recorded.

Rome’s endless conquests also meant that hundreds of thousands of women and men were brought into the empire as slaves. Female slaves did domestic work, worked in brothels, were dancers, actresses, and were sometimes used for sex by their male owners. Slavery was deeply embedded in the culture of Rome as punishment from the gods..

Despite the persistent belief that women should not be educated, upper class Roman women capitalized on the need to build strong and educated warriors to justify their own educations as mothers and future wives of military leaders. In order to protect family fortunes, elite women were sometimes married off without transferring legal control of property to their husbands.This allowed those women to manage their own fortunes. However, the legal control of women’s property frequently remained with their father or male guardian. During the reign of Augustus, he passed a law that stated free-born women who bore three or more children were free from guardianship. Otherwise women were under the control of men.

Little changed for the average Roman woman. Ordinary women were educated just enough to serve the home and rear their children. Male contemporaries remained staunchly opposed to women’s education. Titus Livy, one of the first Roman historians, stated, “a woman’s mind is influenced by little things.” Publius Syrus said, “A woman who meditates alone meditates evil.” Another wrote his misogyny in a poem, “But out of all plagues, the greatest is untold; the book learned wife, in Greek and Latin bold.” If the scholars of the era held such derogatory views of women, there was little possibility for training, recognition, and archiving of female achievements.

Yet we do know about some women, notably the most elite of elite women. Their power or proximity to power meant that their lives and stories would be recorded.

Cleopatra, Public Domain

Cleopatra, Public Domain

Cleopatra

Across the Mediterranean from Rome, Cleopatra, one of the most famous female rulers, came to power. Cleopatra was not Roman, she was the last leader of Ptolemaic Egypt, but her reign had a huge influence on Rome and was a crucial element of the transition of Rome into the Roman Empire. Cleopatra tried to keep Egypt in play as a major world power in the wake of the crushing Roman conquest as well as both internal and external threats. In 51 B.C., the Egyptian throne passed to 18-year-old Cleopatra and her 10-year-old brother, Ptolemy XIII. As is all too common in politics, her brother’s advisors soon painted her as a political threat, and she was forced to flee to Syria. Refusing to see her power stripped away, she raised an army of mercenaries and returned the following year to face her brother’s forces in a civil war. She was known to be financing the war, and she also made sure to be present on the battlefield.

She used all the weapons at her disposal, including her political guile. When Julius Caesar came to Alexandria, Cleopatra had herself smuggled into his headquarters to ask for his support in this war against her brother. Finding mutually beneficial ground, they eventually united against her brother, and successfully overthrew him. She also gave birth to Caesar’s son.

Cleopatra maintained a long, strained relationship with Caesar and Rome, but after Caesar’s assassination, she saw herself potentially in the crosshairs of the new Roman Empire. In her time as pharaoh, she worked to gain the respect of the people for herself and her son, even identifying herself as a vessel of the goddess Isis, which was typical of Egyptian royalty trying to secure their power.

Internal strife always followed Cleopatra. Her younger sister Arsinoe, who had been exiled, was looking to dethrone Cleopatra. Seeking additional security, Cleopatra found herself in a political and romantic alliance with Mark Antony– her ultimate undoing. In her first formal meeting with the general, Plutarch wrote, “she brought with her her surest hopes in her own magic arts and charms.”

Antony was in his own power struggle with Julius Caesar's designated successor, his nephew Octavian (the eventual Augustus), which had been divided into three sections. In an attempt to secure peace. Octavian's sister, Octavia, the Younger, had been married off to Antony. The marriage was initially successful, but tensions mounted and Antony and Octavian were soon at war. In 36BCE Antony left to command troops in Parthia resuming his alliance and romantic liaison with Cleopatra. Octavia was a good and decent wife who, despite his betrayal and infidelity, brought him troops and money. When she arrived, he refused her, and three years later obtained a divorce.

Cleopatra brought her ships and soldiers to aid Antony in the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE, but they lost and she and Antony fled to Alexandria, only to be cornered. Both committed suicide, and their bodies were carried in a victory parade in Rome. Back in Italy, Octavia raised Antony’s children by Cleopatra along with their own children.

Cleopatra was labeled as a seductress by Roman historians because of her relationships. These relationships were undoubtedly romantic in nature, and she used the opportunity to protect her power. Cleopatra stood with some of the most famous figures of the classical world.

Across the Mediterranean from Rome, Cleopatra, one of the most famous female rulers, came to power. Cleopatra was not Roman, she was the last leader of Ptolemaic Egypt, but her reign had a huge influence on Rome and was a crucial element of the transition of Rome into the Roman Empire. Cleopatra tried to keep Egypt in play as a major world power in the wake of the crushing Roman conquest as well as both internal and external threats. In 51 B.C., the Egyptian throne passed to 18-year-old Cleopatra and her 10-year-old brother, Ptolemy XIII. As is all too common in politics, her brother’s advisors soon painted her as a political threat, and she was forced to flee to Syria. Refusing to see her power stripped away, she raised an army of mercenaries and returned the following year to face her brother’s forces in a civil war. She was known to be financing the war, and she also made sure to be present on the battlefield.

She used all the weapons at her disposal, including her political guile. When Julius Caesar came to Alexandria, Cleopatra had herself smuggled into his headquarters to ask for his support in this war against her brother. Finding mutually beneficial ground, they eventually united against her brother, and successfully overthrew him. She also gave birth to Caesar’s son.

Cleopatra maintained a long, strained relationship with Caesar and Rome, but after Caesar’s assassination, she saw herself potentially in the crosshairs of the new Roman Empire. In her time as pharaoh, she worked to gain the respect of the people for herself and her son, even identifying herself as a vessel of the goddess Isis, which was typical of Egyptian royalty trying to secure their power.

Internal strife always followed Cleopatra. Her younger sister Arsinoe, who had been exiled, was looking to dethrone Cleopatra. Seeking additional security, Cleopatra found herself in a political and romantic alliance with Mark Antony– her ultimate undoing. In her first formal meeting with the general, Plutarch wrote, “she brought with her her surest hopes in her own magic arts and charms.”

Antony was in his own power struggle with Julius Caesar's designated successor, his nephew Octavian (the eventual Augustus), which had been divided into three sections. In an attempt to secure peace. Octavian's sister, Octavia, the Younger, had been married off to Antony. The marriage was initially successful, but tensions mounted and Antony and Octavian were soon at war. In 36BCE Antony left to command troops in Parthia resuming his alliance and romantic liaison with Cleopatra. Octavia was a good and decent wife who, despite his betrayal and infidelity, brought him troops and money. When she arrived, he refused her, and three years later obtained a divorce.

Cleopatra brought her ships and soldiers to aid Antony in the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE, but they lost and she and Antony fled to Alexandria, only to be cornered. Both committed suicide, and their bodies were carried in a victory parade in Rome. Back in Italy, Octavia raised Antony’s children by Cleopatra along with their own children.

Cleopatra was labeled as a seductress by Roman historians because of her relationships. These relationships were undoubtedly romantic in nature, and she used the opportunity to protect her power. Cleopatra stood with some of the most famous figures of the classical world.

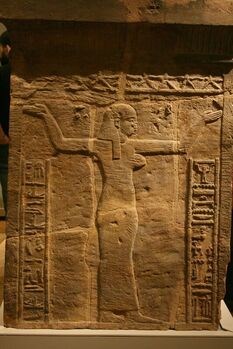

Kandake, Wikimedia Commons

Kandake, Wikimedia Commons

Kandake Amanirenas

Further south, another female African monarch prepared to face Rome and end its expansion southward. Unlike Cleopatra, she would succeed–sort of. Romans began incursions south toward the Empire of Kush, so the Kushites planned a preemptive attack on Roman-held cities in southern Egypt and were initially successful, but their king died in battle.

Quee, Kandake whose name means “great woman,” Amanirenas, and her son, again led the Kushites north to engage the Romans. Romans responded by leading 10,000 soldiers southward. The result was basically a stalemate. By succeeding in negotiations, Kandake Amanirenas spared her people from domination.

Empresses of RomeBack in Rome, Cleopatra’s defeat and continued Roman expansion led to wealth and a long line of powerful empresses. Octavian was surrounded by powerful women who defined and navigated his political leadership.

Further south, another female African monarch prepared to face Rome and end its expansion southward. Unlike Cleopatra, she would succeed–sort of. Romans began incursions south toward the Empire of Kush, so the Kushites planned a preemptive attack on Roman-held cities in southern Egypt and were initially successful, but their king died in battle.

Quee, Kandake whose name means “great woman,” Amanirenas, and her son, again led the Kushites north to engage the Romans. Romans responded by leading 10,000 soldiers southward. The result was basically a stalemate. By succeeding in negotiations, Kandake Amanirenas spared her people from domination.

Empresses of RomeBack in Rome, Cleopatra’s defeat and continued Roman expansion led to wealth and a long line of powerful empresses. Octavian was surrounded by powerful women who defined and navigated his political leadership.

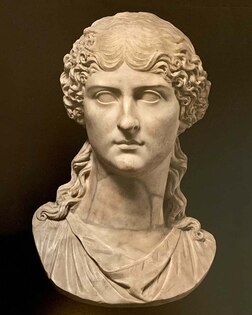

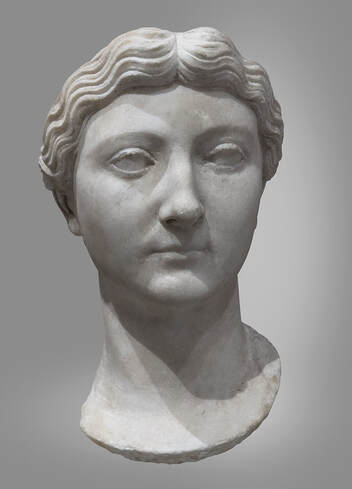

Livia Drusilla, Wikimedia Commons

Livia Drusilla, Wikimedia Commons

The Julias

Octavian’s wife, Scibonia, bore only one child, a daughter, Julia. When she was only a few days old, Augustus fell in love with Livia Drusilla at first sight and they both promptly divorced their spouses. As empress consort, Livia was active in politics and governed her own affairs. She pushed him towards making Tiberius his heir. Augustus forced him to divorce his wife and instead marry his daughter Julia, her second political marriage, and a marriage neither wanted. Julia already had two daughters, another Julia and Agrippina the Elder. When Julia and Tiberius’s only child died in infancy, any semblance of happiness they had was gone. Julia was left alone in Rome, where she lived a promiscuous life. Roman author Macrobius claimed she was a witty and intelligent woman who was loved by the people, but her sexual activity led Augustus to exile her as a “disease in my flesh.” She died from malnutrition while in exile.

Augustus gave his wife Livia the title of Augusta, guaranteeing that she would maintain her title after he died. He left her one third of his estate. Her son Tiberius found her power hard to maneuver around, an influence she maintained through political allies. But Tiberius’s rule was problematic for other reasons. Mostly because Julia the Elder’s daughters were wreaking havoc on his legitimacy. Agrippina the Elder accused him of murdering her husband, whom she had nine children with. When Tiberius’s son died, she came into the line of succession, so she and her older sons were exiled and died.

Her remaining son became Tiberius’s successor, Emperor Caligula. Three daughters also survived. Caligula was by all accounts a terrible ruler, so his sister, Julia and Agrippina the Younger plotted to kill him. Agrippina was exiled for a short time, but when Caligula was finally murdered, her uncle and third husband, Claudius, brought her back to Rome. Agrippina was labeled by historians as the “first true empress of Rome.”

Claudius was Livia’s grandson. His third wife was executed for having an affair with a Senator. So Agrippina the Younger needed to navigate her path cautiously, which she did. He elevated her title to the one his grandmother had, Augusta, and elevated Livia to deity status! According to some sources Claudius was sickly, weak and not suited for imperial life, although by the standards of his successors he did a pretty okay job. Despite being an Empress consort, Agrippina wanted to exercise real power. She was visible in politics and sat next to Claudius at occasions of state. For five years there was prosperity, but Roman historians tell us Agrippina wanted even more influence, so she murdered Claudius and installed her infamous son: Nero.

Gold coins from right after Nero became emperor show him nose to nose with his mom, with the title, “Wife of the Deified Claudius, Mother of Nero Caesar.” But Roman historians who recorded his legacy sought to paint him as the epitome of a corrupt, debaucherous, and evil ruler. In doing so they told the stories of his violence against women. It’s hard to know what is true and what is not, because the authors of these texts were blatantly biased against him. According to later Roman historians, he and his mother were sometimes lovers— ew! Then in order to solidify his rule, he had her killed because she was too powerful and Senators were teasing him for being “ruled by a woman” and his manhood was threatened. A little bit of ancient toxic masculinity, anyone? The Roman historian Tacitus alleged that Agrippina was so desperate for power after murdering her husband that she seduced her own son! Regardless of the likely exaggerations, Nero did order his mother killed. Later, Nero apparently had his first wife, and step-sister, Claudia Octavia (the daughter of Claudius) banished, bound, and stabbed before suffocating her in a hot bath. He then murdered his second wife, Poppaea Sabina, by kicking her pregnant belly. But a lot of this probably tells us more about the historians than Nero and his wives. It is interesting though that ill-treatment of women was used to demonstrate the evil nature of a ruler, which perhaps suggests that treating your women well was to be admired (a controversial opinion in those days!)

Although Nero is remembered for killing Christians, intentionally burning Rome, and other ridiculous things, a lot of evidence shows that Nero was not unpopular with the people. He clashed with the Senate and wealthy elites because they wanted to maintain their wealth, but the Roman Empire could no longer be governed like a city state-- taxes had to be raised, and soldiers sent to defend land. The government had difficulty defending its vast territory from the many “barbarian” tribes moving into Roman lands.

Octavian’s wife, Scibonia, bore only one child, a daughter, Julia. When she was only a few days old, Augustus fell in love with Livia Drusilla at first sight and they both promptly divorced their spouses. As empress consort, Livia was active in politics and governed her own affairs. She pushed him towards making Tiberius his heir. Augustus forced him to divorce his wife and instead marry his daughter Julia, her second political marriage, and a marriage neither wanted. Julia already had two daughters, another Julia and Agrippina the Elder. When Julia and Tiberius’s only child died in infancy, any semblance of happiness they had was gone. Julia was left alone in Rome, where she lived a promiscuous life. Roman author Macrobius claimed she was a witty and intelligent woman who was loved by the people, but her sexual activity led Augustus to exile her as a “disease in my flesh.” She died from malnutrition while in exile.

Augustus gave his wife Livia the title of Augusta, guaranteeing that she would maintain her title after he died. He left her one third of his estate. Her son Tiberius found her power hard to maneuver around, an influence she maintained through political allies. But Tiberius’s rule was problematic for other reasons. Mostly because Julia the Elder’s daughters were wreaking havoc on his legitimacy. Agrippina the Elder accused him of murdering her husband, whom she had nine children with. When Tiberius’s son died, she came into the line of succession, so she and her older sons were exiled and died.

Her remaining son became Tiberius’s successor, Emperor Caligula. Three daughters also survived. Caligula was by all accounts a terrible ruler, so his sister, Julia and Agrippina the Younger plotted to kill him. Agrippina was exiled for a short time, but when Caligula was finally murdered, her uncle and third husband, Claudius, brought her back to Rome. Agrippina was labeled by historians as the “first true empress of Rome.”

Claudius was Livia’s grandson. His third wife was executed for having an affair with a Senator. So Agrippina the Younger needed to navigate her path cautiously, which she did. He elevated her title to the one his grandmother had, Augusta, and elevated Livia to deity status! According to some sources Claudius was sickly, weak and not suited for imperial life, although by the standards of his successors he did a pretty okay job. Despite being an Empress consort, Agrippina wanted to exercise real power. She was visible in politics and sat next to Claudius at occasions of state. For five years there was prosperity, but Roman historians tell us Agrippina wanted even more influence, so she murdered Claudius and installed her infamous son: Nero.

Gold coins from right after Nero became emperor show him nose to nose with his mom, with the title, “Wife of the Deified Claudius, Mother of Nero Caesar.” But Roman historians who recorded his legacy sought to paint him as the epitome of a corrupt, debaucherous, and evil ruler. In doing so they told the stories of his violence against women. It’s hard to know what is true and what is not, because the authors of these texts were blatantly biased against him. According to later Roman historians, he and his mother were sometimes lovers— ew! Then in order to solidify his rule, he had her killed because she was too powerful and Senators were teasing him for being “ruled by a woman” and his manhood was threatened. A little bit of ancient toxic masculinity, anyone? The Roman historian Tacitus alleged that Agrippina was so desperate for power after murdering her husband that she seduced her own son! Regardless of the likely exaggerations, Nero did order his mother killed. Later, Nero apparently had his first wife, and step-sister, Claudia Octavia (the daughter of Claudius) banished, bound, and stabbed before suffocating her in a hot bath. He then murdered his second wife, Poppaea Sabina, by kicking her pregnant belly. But a lot of this probably tells us more about the historians than Nero and his wives. It is interesting though that ill-treatment of women was used to demonstrate the evil nature of a ruler, which perhaps suggests that treating your women well was to be admired (a controversial opinion in those days!)

Although Nero is remembered for killing Christians, intentionally burning Rome, and other ridiculous things, a lot of evidence shows that Nero was not unpopular with the people. He clashed with the Senate and wealthy elites because they wanted to maintain their wealth, but the Roman Empire could no longer be governed like a city state-- taxes had to be raised, and soldiers sent to defend land. The government had difficulty defending its vast territory from the many “barbarian” tribes moving into Roman lands.

Boudicca, Wikimedia Commons

Boudicca, Wikimedia Commons

Boudicca of Britain

In 60 CE, half a world away, an Iceni queen on the island of Britain, Boudicca, took up the mantle of warrior for her people, The Iceni, had once welcomed the Romans, seeing them as a powerful, and potentially beneficial ally during the early expeditions by Caesar. However, in the later colonial efforts, the Romans made a number of enemies among the tribe of Britain, including those who had offered alliances to Caesar in the years before by forcing them into economic and political arrangements that only benefited Rome. Increased oppression over the years would lead to a number of rebellions, large and small, but none created such fear as Boudicca’s.

When her husband died, he left behind a will that named the Roman emperor co-heir with his two teenage daughters. His hope had been that this would protect his people by maintaining some of their power, and would also please Rome by giving them a share of his fortune. However, Rome had no interest in obeying the will of a dead king, and claimed the entirety of the tribe’s lands as their own.

Soon the Romans appeared to take their lands. When Boudicca objected, she was mercilessly flogged in front of her people. Far worse, her daughters were dragged in front of her and raped. Boudicca rose up and avenged her own family, as well as her tribal family. She gained support from surrounding tribes who united to free themselves from “the Roman menace.” Some argued that she used false omens and witchcraft to convince others to follow her, though that comes mainly from Roman historians.

Soon she led her united tribal armies against Roman colonial towns. Brutality was clearly not just a Roman tactic, as her armies were known to brutalize the population, even burning down a Roman temple with hundreds inside. Her pattern of success seemed marked by a blaze of glory as she destroyed multiple Roman and Roman-allied towns, to the point that Roman officials had no choice but to attack.

10,000 Romans confronted Boudicca and her people at an unknown location. When they met, she supposedly had an army of 230,000. It is likely that Boudicca had the larger force, but many of her soldiers were undertrained or ill-equipped compared to professional Roman forces. Still, it is said that Boudicca’s forces consisted of men and women, young and old, following her and her daughters’ carriage into battle. According to Tacitus, she rode in front of her people on a chariot with her daughters, “avenging, not, as a queen of glorious ancestry, her ravished realm and power, but, as a woman of the people, her liberty lost, her body tortured by the lash, the tarnished honor of her daughters. Roman cupidity had progressed so far that not their very persons, not age itself, nor maidenhood, were left unpolluted."

Unfortunately, her forces were routed by the Roman legionaries, and Boudicca, like Cleopatra, chose suicide over capture. She still remains a symbol of freedom, unity, and courage in British culture. Her statue stands, ironically, in the very city she burned down: London.

In 60 CE, half a world away, an Iceni queen on the island of Britain, Boudicca, took up the mantle of warrior for her people, The Iceni, had once welcomed the Romans, seeing them as a powerful, and potentially beneficial ally during the early expeditions by Caesar. However, in the later colonial efforts, the Romans made a number of enemies among the tribe of Britain, including those who had offered alliances to Caesar in the years before by forcing them into economic and political arrangements that only benefited Rome. Increased oppression over the years would lead to a number of rebellions, large and small, but none created such fear as Boudicca’s.

When her husband died, he left behind a will that named the Roman emperor co-heir with his two teenage daughters. His hope had been that this would protect his people by maintaining some of their power, and would also please Rome by giving them a share of his fortune. However, Rome had no interest in obeying the will of a dead king, and claimed the entirety of the tribe’s lands as their own.

Soon the Romans appeared to take their lands. When Boudicca objected, she was mercilessly flogged in front of her people. Far worse, her daughters were dragged in front of her and raped. Boudicca rose up and avenged her own family, as well as her tribal family. She gained support from surrounding tribes who united to free themselves from “the Roman menace.” Some argued that she used false omens and witchcraft to convince others to follow her, though that comes mainly from Roman historians.

Soon she led her united tribal armies against Roman colonial towns. Brutality was clearly not just a Roman tactic, as her armies were known to brutalize the population, even burning down a Roman temple with hundreds inside. Her pattern of success seemed marked by a blaze of glory as she destroyed multiple Roman and Roman-allied towns, to the point that Roman officials had no choice but to attack.

10,000 Romans confronted Boudicca and her people at an unknown location. When they met, she supposedly had an army of 230,000. It is likely that Boudicca had the larger force, but many of her soldiers were undertrained or ill-equipped compared to professional Roman forces. Still, it is said that Boudicca’s forces consisted of men and women, young and old, following her and her daughters’ carriage into battle. According to Tacitus, she rode in front of her people on a chariot with her daughters, “avenging, not, as a queen of glorious ancestry, her ravished realm and power, but, as a woman of the people, her liberty lost, her body tortured by the lash, the tarnished honor of her daughters. Roman cupidity had progressed so far that not their very persons, not age itself, nor maidenhood, were left unpolluted."

Unfortunately, her forces were routed by the Roman legionaries, and Boudicca, like Cleopatra, chose suicide over capture. She still remains a symbol of freedom, unity, and courage in British culture. Her statue stands, ironically, in the very city she burned down: London.

Zenobia in Chains, Public Domain

Zenobia in Chains, Public Domain

Zenobia of the Middle East

Boudicca was not the only leader to challenge Rome. Zenobia was queen of the Palmyrene Empire, formed as a breakaway kingdom from the Roman Empire amid power struggles in the Third Century CE. Unlike Boudicca, who fought Rome directly, Zenobia cleverly constructed an expansive empire right under their nose until her power could no longer be ignored.

Born in a Roman province, Zenobia was a Roman citizen and possibly had ties to prominent, historic Roman families. However, she would proclaim that she was a descendant of Hellenistic royalty, including Cleopatra and Dido. Long before she came to power, sArabic histories indicate that she developed her characteristic stamina, equestrian skills, and her experience in leading men.

She later married the Roman governor of Syria from the city of Palmyra, which was an important trade center on the Silk Road where merchants had to pay taxes both on their way to and from Rome. Yet, with increasing incursions by the Parthian Empire, the Romans attempted to reassert their authority and reconquer their territories in the region, which failed epically until Zenobia’s husband, Odaenthus, marched against the Persians and reinstated Roman rule. He was rewarded with governorship of the eastern portion of the empire.

Odaenthus became more and more powerful, however, around 266 CE he was assassinated by his nephew. Some ancient historians hinted that Zenobia herself was behind the assassination. Zenobia's son inherited the throne, but because he was still a child, she ruled in his place.

Palmyra had a solid relationship with Rome at the time, and Odaenthus was even considered a possible successor for the emperor. Initially, Zenobia saw the same potential for herself and her son, but as the chaos of the Crisis of the Third Century continued, she decided not to wait. In 269 CE, she sent her army into Roman Egypt and claimed it as her own, but cleverly did so under the guise of putting down a local revolt, and thereby looking like she was doing so in favor of Rome. Contemporary historians contended that she sent instigators to start the revolt. She not only gained control of Egypt, but soon the areas of the Levant and parts of Asia Minor, all while proclaiming loyalty to Rome. Only five years into her rule as regent, and two years after her conquest of Egypt, she created an empire that began to rival the two major powers on either side of her: the Roman and Persian Empires, but neither seemed to even realize what she was doing.

When Aurelian became emperor, he was a military man who was intent on bringing order back to Rome through force. He turned on Zenobia’s blooming empire in 272CE, destroying everything in his path. Cities soon surrendered to him before he even reached them to ensure their safety. Zenobia tried to reach the emperor and assure him of her (questionable) loyalty, but he didn't respond and in his silence, she raised her army in preparation for battle.

Unfortunately for the warrior queen, Aurelian’s forces slaughtered hers, not only at the Battle of Immae, but again outside of Emesa where Zenobia had retreated to regroup.. Though defeated, this is not to say her and her people didn’t put up quite a fight in the process. Aurelian wrote, “It cannot be told what a store of arrows is here, what great preparations for war, what a store of spears and of stones; there is no section of the wall that is not held by two or three engines of war, and their machines can even hurl fire. Why say more? She fears like a woman, and fights as one who fears punishment. I believe, however, that the gods will truly bring aid to the Roman commonwealth, for they have never failed our endeavors."

She and her son fled toward Persia. The skilled equestrians had outpaced his pursuing cavalry for some time, but they were finally caught trying to cross the Euphrates River and were brought back to Rome.

Her fate is contested. Some historians claimed she was paraded through the capital city, as many prisoners had been, chained and publicly shamed. Some proclaim that she died on the way to Rome. Others say she was put on trial in Rome, but was ultimately acquitted when claiming that she was innocent and simply misled by advisors. Others still say that she was not only acquitted, but actually married a prominent Roman and had a daughter who was later married to Aurelian himself.

While she may or may not have met a noble fitt for the warrior queen that she was, Zenobia, like the other leading women of the ancient world, had proven her ability to weather the hardships and consequences of war. Historians described her as being a leader who worked her soldiers hard, and could out-hunt and out-drink any one of them. More modern historians have analyzed that she had deftly used the stereotypes of her gender both in her methods of building her empire and possibly in her trial after the fact, allowing the men around her to assume she was weaker or more naïve than she truly was. In doing so, she created a powerful army and empire, that while short-lived, was one of her own creation, and her authority became a primary target of the greatest empire of the ancient world. Zenobia was one of the most powerful, although under-appreciated figures of the ancient world. Let’s reinstall her in her proper, impressive place.

Boudicca was not the only leader to challenge Rome. Zenobia was queen of the Palmyrene Empire, formed as a breakaway kingdom from the Roman Empire amid power struggles in the Third Century CE. Unlike Boudicca, who fought Rome directly, Zenobia cleverly constructed an expansive empire right under their nose until her power could no longer be ignored.

Born in a Roman province, Zenobia was a Roman citizen and possibly had ties to prominent, historic Roman families. However, she would proclaim that she was a descendant of Hellenistic royalty, including Cleopatra and Dido. Long before she came to power, sArabic histories indicate that she developed her characteristic stamina, equestrian skills, and her experience in leading men.

She later married the Roman governor of Syria from the city of Palmyra, which was an important trade center on the Silk Road where merchants had to pay taxes both on their way to and from Rome. Yet, with increasing incursions by the Parthian Empire, the Romans attempted to reassert their authority and reconquer their territories in the region, which failed epically until Zenobia’s husband, Odaenthus, marched against the Persians and reinstated Roman rule. He was rewarded with governorship of the eastern portion of the empire.

Odaenthus became more and more powerful, however, around 266 CE he was assassinated by his nephew. Some ancient historians hinted that Zenobia herself was behind the assassination. Zenobia's son inherited the throne, but because he was still a child, she ruled in his place.

Palmyra had a solid relationship with Rome at the time, and Odaenthus was even considered a possible successor for the emperor. Initially, Zenobia saw the same potential for herself and her son, but as the chaos of the Crisis of the Third Century continued, she decided not to wait. In 269 CE, she sent her army into Roman Egypt and claimed it as her own, but cleverly did so under the guise of putting down a local revolt, and thereby looking like she was doing so in favor of Rome. Contemporary historians contended that she sent instigators to start the revolt. She not only gained control of Egypt, but soon the areas of the Levant and parts of Asia Minor, all while proclaiming loyalty to Rome. Only five years into her rule as regent, and two years after her conquest of Egypt, she created an empire that began to rival the two major powers on either side of her: the Roman and Persian Empires, but neither seemed to even realize what she was doing.

When Aurelian became emperor, he was a military man who was intent on bringing order back to Rome through force. He turned on Zenobia’s blooming empire in 272CE, destroying everything in his path. Cities soon surrendered to him before he even reached them to ensure their safety. Zenobia tried to reach the emperor and assure him of her (questionable) loyalty, but he didn't respond and in his silence, she raised her army in preparation for battle.

Unfortunately for the warrior queen, Aurelian’s forces slaughtered hers, not only at the Battle of Immae, but again outside of Emesa where Zenobia had retreated to regroup.. Though defeated, this is not to say her and her people didn’t put up quite a fight in the process. Aurelian wrote, “It cannot be told what a store of arrows is here, what great preparations for war, what a store of spears and of stones; there is no section of the wall that is not held by two or three engines of war, and their machines can even hurl fire. Why say more? She fears like a woman, and fights as one who fears punishment. I believe, however, that the gods will truly bring aid to the Roman commonwealth, for they have never failed our endeavors."

She and her son fled toward Persia. The skilled equestrians had outpaced his pursuing cavalry for some time, but they were finally caught trying to cross the Euphrates River and were brought back to Rome.

Her fate is contested. Some historians claimed she was paraded through the capital city, as many prisoners had been, chained and publicly shamed. Some proclaim that she died on the way to Rome. Others say she was put on trial in Rome, but was ultimately acquitted when claiming that she was innocent and simply misled by advisors. Others still say that she was not only acquitted, but actually married a prominent Roman and had a daughter who was later married to Aurelian himself.

While she may or may not have met a noble fitt for the warrior queen that she was, Zenobia, like the other leading women of the ancient world, had proven her ability to weather the hardships and consequences of war. Historians described her as being a leader who worked her soldiers hard, and could out-hunt and out-drink any one of them. More modern historians have analyzed that she had deftly used the stereotypes of her gender both in her methods of building her empire and possibly in her trial after the fact, allowing the men around her to assume she was weaker or more naïve than she truly was. In doing so, she created a powerful army and empire, that while short-lived, was one of her own creation, and her authority became a primary target of the greatest empire of the ancient world. Zenobia was one of the most powerful, although under-appreciated figures of the ancient world. Let’s reinstall her in her proper, impressive place.

Women in Roman Empire, Public Domain

Women in Roman Empire, Public Domain

Conclusion

Inside and outside the Roman Empire, women participated in the issues of their time. Women labored in the domestic sphere as homemakers and mothers, in markets, were prostitutes and slaves, and jockeyed for power. Women also played prominent roles in securing and challenging the empire.

They rose to power amid the restrictions and expectations of their societies. While these outliers are known, many thousands of female leaders have been lost to time.

In many ways the Han Empire was similar to the Roman Empire. Compare and contrast these empires with Women and the Han Empire. What more can we learn about these women? How did the layers of class and region change their experiences? Why are these women symbolic of their time or region? What lessons do their stories hold for female leadership in the centuries to come?

Inside and outside the Roman Empire, women participated in the issues of their time. Women labored in the domestic sphere as homemakers and mothers, in markets, were prostitutes and slaves, and jockeyed for power. Women also played prominent roles in securing and challenging the empire.

They rose to power amid the restrictions and expectations of their societies. While these outliers are known, many thousands of female leaders have been lost to time.

In many ways the Han Empire was similar to the Roman Empire. Compare and contrast these empires with Women and the Han Empire. What more can we learn about these women? How did the layers of class and region change their experiences? Why are these women symbolic of their time or region? What lessons do their stories hold for female leadership in the centuries to come?

Draw your own conclusions

|

Learn how to teach with inquiry.

Many of these lesson plans were sponsored in part by the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources Eastern Region Program, coordinated by Waynesburg University, the History and Social Studies Education Faculty at Plymouth State University, and the Patrons of the Remedial Herstory Project. |

Lesson Plans from Other Organizations

- This website, Women in World History has primary source based lesson plans on women's history in a whole range of topics. Some are free while others have a cost.

- The Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media has produced recommendations for teaching women's history with primary sources and provided a collection of sources for world history. Check them out!

- The Stanford History Education Group has a number of lesson plans about women in World History.

Women in Roman Myths

Livy: The Rape of Rhea Silvia by Mars

This story is from the History of Rome, a text dating to around 29 BCE. The story follows Amulius’ attempts to secure his power after overthrowing his brother and the rescue of Romulus and Remus by a she-wolf.

Amulius drove out his brother and ruled in his stead. Adding crime to crime, he destroyed Numitor's male issue; and Rhea Silvia, his brother's daughter, he appointed a Vestal under pretense of honouring her, and by consigning her to perpetual virginity, deprived her of the hope of children. But the Fates were resolved, as I suppose, upon the founding of this great City, and the beginning of the mightiest of empires, next after that of Heaven. The Vestal was ravished, and having given birth to twin sons, named Mars as the father of her doubtful offspring, whether actually so believing, or because it seemed less wrong if a god were the author of her fault. But neither gods nor men protected the mother herself or her babes from the king's cruelty; the priestess he ordered to be manacled and cast into prison, the children to be committed to the river. It happened by singular good fortune that the Tiber having spread beyond its banks into stagnant pools afforded nowhere any access to the regular channel of the river, and the men who brought the twins were led to hope that being infants they might be drowned, no matter how sluggish the stream. So they made shift to discharge the king’s command, by exposing the babes at the nearest point of the overflow, where the fig-tree Ruminalis—formerly, they say, called Romularis—now stands. In those days this was a wild and uninhabited region. The story persists that when the floating basket in which the children had been exposed was left high and dry by the receding water, a she-wolf, coming down out of the surrounding hills to slake her thirst, turned her steps towards the cry of the infants, and with her teats gave them suck so gently, that the keeper of the royal flock found her licking them with her tongue.

Livy, History of Rome, Book 1. Chapter 4. Translation by Foster. B. O (1919) London: Loeb Classical Library.

Questions

Amulius drove out his brother and ruled in his stead. Adding crime to crime, he destroyed Numitor's male issue; and Rhea Silvia, his brother's daughter, he appointed a Vestal under pretense of honouring her, and by consigning her to perpetual virginity, deprived her of the hope of children. But the Fates were resolved, as I suppose, upon the founding of this great City, and the beginning of the mightiest of empires, next after that of Heaven. The Vestal was ravished, and having given birth to twin sons, named Mars as the father of her doubtful offspring, whether actually so believing, or because it seemed less wrong if a god were the author of her fault. But neither gods nor men protected the mother herself or her babes from the king's cruelty; the priestess he ordered to be manacled and cast into prison, the children to be committed to the river. It happened by singular good fortune that the Tiber having spread beyond its banks into stagnant pools afforded nowhere any access to the regular channel of the river, and the men who brought the twins were led to hope that being infants they might be drowned, no matter how sluggish the stream. So they made shift to discharge the king’s command, by exposing the babes at the nearest point of the overflow, where the fig-tree Ruminalis—formerly, they say, called Romularis—now stands. In those days this was a wild and uninhabited region. The story persists that when the floating basket in which the children had been exposed was left high and dry by the receding water, a she-wolf, coming down out of the surrounding hills to slake her thirst, turned her steps towards the cry of the infants, and with her teats gave them suck so gently, that the keeper of the royal flock found her licking them with her tongue.

Livy, History of Rome, Book 1. Chapter 4. Translation by Foster. B. O (1919) London: Loeb Classical Library.

Questions

- How are women depicted in this source?

- How is the rape of "the Vestal" portrayed?

Livy: The Abduction of The Sabine Women

Another story from Livy’s History of Rome, this text details the abduction of the Sabine women. Play close attention to the mention of marriage rites and the way women are described.

When the hour for the games had come, and their eyes and minds were alike riveted on the spectacle before them, the preconcerted signal was given and the Roman youth dashed in all directions to carry off the maidens who were present. The larger part were carried off indiscriminately, but some particularly beautiful girls who had been marked out for the leading patricians were carried to their houses by plebeians told off for the task. One, conspicuous amongst them all for grace and beauty, is reported to have been carried off by a group led by a certain Talassius, and to the many inquiries as to whom she was intended for, the invariable answer was given, ‘For Talassius.’ Hence the use of this word in the marriage rites. Alarm and consternation broke up the games, and the parents of the maidens fled, distracted with grief, uttering bitter reproaches on the violators of the laws of hospitality and appealing to the god to whose solemn games they had come, only to be the victims of impious perfidy.

The abducted maidens were quite as despondent and indignant. Romulus, however, went round in person, and pointed out to them that it was all owing to the pride of their parents in denying right of intermarriage to their neighbours. They would live in honourable wedlock, and share all their property and civil rights, and —dearest of all to human nature-would be the mothers of freemen. He begged them to lay aside their feelings of resentment and give their affections to those whom fortune had made masters of their persons. An injury had often led to reconciliation and love; they would find their husbands all the more affectionate because each would do his utmost, so far as in him lay to make up for the loss of parents and country. These arguments were reinforced by the endearments of their husbands who excused their conduct by pleading the irresistible force of their passion —a plea effective beyond all others in appealing to a woman's nature.

Livy, History of Rome, Book 1. Chapter 9. Translation by Foster. B. O (1919) London: Loeb Classical Library.

Questions

When the hour for the games had come, and their eyes and minds were alike riveted on the spectacle before them, the preconcerted signal was given and the Roman youth dashed in all directions to carry off the maidens who were present. The larger part were carried off indiscriminately, but some particularly beautiful girls who had been marked out for the leading patricians were carried to their houses by plebeians told off for the task. One, conspicuous amongst them all for grace and beauty, is reported to have been carried off by a group led by a certain Talassius, and to the many inquiries as to whom she was intended for, the invariable answer was given, ‘For Talassius.’ Hence the use of this word in the marriage rites. Alarm and consternation broke up the games, and the parents of the maidens fled, distracted with grief, uttering bitter reproaches on the violators of the laws of hospitality and appealing to the god to whose solemn games they had come, only to be the victims of impious perfidy.

The abducted maidens were quite as despondent and indignant. Romulus, however, went round in person, and pointed out to them that it was all owing to the pride of their parents in denying right of intermarriage to their neighbours. They would live in honourable wedlock, and share all their property and civil rights, and —dearest of all to human nature-would be the mothers of freemen. He begged them to lay aside their feelings of resentment and give their affections to those whom fortune had made masters of their persons. An injury had often led to reconciliation and love; they would find their husbands all the more affectionate because each would do his utmost, so far as in him lay to make up for the loss of parents and country. These arguments were reinforced by the endearments of their husbands who excused their conduct by pleading the irresistible force of their passion —a plea effective beyond all others in appealing to a woman's nature.

Livy, History of Rome, Book 1. Chapter 9. Translation by Foster. B. O (1919) London: Loeb Classical Library.

Questions

- How does this document describe the abduction of the Sabine women?

- Why is this description significant?

- What does this tell us about how this founding myth established gender norms?

Livy: The Intervention of The Sabine Women

Our final extract from Livy’s History of Rome describes how the Sabine women intervened in the war and called for peace.

They went boldly into the midst of the flying missiles with disheveled hair and rent garments. Running across the space between the two armies they tried to stop any further fighting and calm the excited passions by appealing to their fathers in the one army and their husbands in the other not to bring upon themselves a curse by staining their hands with the blood of a father-in-law or a son-in-law, nor upon their posterity the taint of parricide. "If," they cried, "you are weary of these ties of kindred, these marriage-bonds, then turn your anger upon us; it is we who are the cause of the war, it is we who have wounded and slain our husbands and fathers. Better for us to perish rather than live without one or the other of you, as widows or as orphans."

Livy, History of Rome, Book 1. Chapter 13. Translation by Foster. B. O (1919) London: Loeb Classical Library.

Questions

They went boldly into the midst of the flying missiles with disheveled hair and rent garments. Running across the space between the two armies they tried to stop any further fighting and calm the excited passions by appealing to their fathers in the one army and their husbands in the other not to bring upon themselves a curse by staining their hands with the blood of a father-in-law or a son-in-law, nor upon their posterity the taint of parricide. "If," they cried, "you are weary of these ties of kindred, these marriage-bonds, then turn your anger upon us; it is we who are the cause of the war, it is we who have wounded and slain our husbands and fathers. Better for us to perish rather than live without one or the other of you, as widows or as orphans."

Livy, History of Rome, Book 1. Chapter 13. Translation by Foster. B. O (1919) London: Loeb Classical Library.

Questions

- Why was this speech important?

- How are women portrayed in this document?

Women and Healthcare

Hippocrates: Diseases of Women 1

Diseases of Women is a collection of writings by the classical Greek author, Hippocrates, on gynecology. Hippocrates is often regarded as the father of modern medicine. The document below describes the Hippocratic understanding of why women experienced a menstrual bleed and how a woman might avoid menstrual issues.

Since in a woman who has not given birth, the body is not accustomed to being filled up (sc. with blood), but is robust, solider and denser than if she had experienced the lochia, and her uterus has not been dilated, her menstrual flow will be accompanied by more pain, and more troubles will be present: i.e., her menses will be obstructed when she has not given birth. This is so for the reason I first indicated when I contended that a woman is more porous and softer than a man; this being so, a woman’s body draws what is being exhaled from her cavity more quickly and in a greater amount than does a man’s...

Also, because a woman’s flesh is softer, when her body fills up with blood, unless the blood is then discharged from her body, the filling and warming, of their tissues that ensue will provoke pain: for a woman has hotter blood, and for this reason she herself is hotter than a man; if, however, most the blood that was added is subsequently discharged, no pain will arise from it. A man, having solider flesh than a woman, will never overfill with so much blood that, unless some it is discharged each month, he feels pain, and besides he takes in only as much (sc. blood) as is necessary for the nourishment his body, and his body—lacking softness as it does—is never overstretched or heated by fullness as a woman’s is. A great amount this is also due in a man to his exerting himself physically more than a woman, which consumes a part of the exhalation (sc. rising from his food).

Now when, in a woman who has not given birth, the menses fail to appear and cannot find their way out, a disease arises, and this happens if the mouth the uterus is closed or folded over, or some part the vagina has become constricted; for if any these things happens, the menses will be unable to find their way out until the uterus returns to a natural healthy state. This disease generally occurs in whose uterus has a narrow mouth or neck lying further forward into the vagina. For if either these be the case, and the woman does not have intercourse with her husband, and her cavity is more empty than it should be as the result of some disease, the uterus turns aside. For it has no moistness of its own, since the woman is not having intercourse, and there is an open space for it since the cavity is too empty, so that it turns aside because it is drier and lighter than it should be. And sometimes as it turns aside its mouth becomes displaced too far to one side because its neck is lying too far into the vagina. For if the uterus is moist as the result of intercourse and the cavity is not empty, it is not likely to turn aside. This is why the uterus closes as the result of a woman not having intercourse.

Hippocrates, Diseases of Women, Book 1. Translation by Potter. P (2018) London: Loeb Classical Library.

Questions:

- Based off this document, what does Hippocrates believe the relationship between sex and menstruation to be?

- What misogynistic (fearful or hateful) ideas about women can you find in this document?

- What can you infer about Hippocrates perception of women and menstruation?

Soranus of Ephesus: Gynecology

Soranus of Ephesus was a Greek gynecologist who commented on women’s diseases and childbearing. His work also features a 2nd century BCE understanding of menstrual cycles and what is now known as amenorrhea (an absence of menstruation).

Now of those who do not menstruate, some have no ailment and it is physiological for them not to menstruate: either because of their age (as in those too young or on the contrary too old) or because they are pregnant, or mannish, or barren singers and athletes in whom nothing is left over for menstruation, everything being consumed by the exercises or changed into tissue. Others, however, do not menstruate because of a disease of the uterus, or of the rest of the body, or of both: “of the uterus” if the condition of so-called imperforation is present, or callosity, or scirrhus, or inflammation, or a scar has formed on a sore, or a closure of the orifice (from long widowhood among other causes).

Soranus of Ephesus, Gynecology. Translation by Temkin. O (1956) Baltimore: The John Hopkins Press

Questions:

- Based off this document, what does Soranus of Ephesus believe a lack of menstruation to be caused by? Do any of those reasons seem inaccurate? Why or why not?

- What misogynistic (fearful or hateful) ideas about women can you find in this document?

- What can you infer about Soranus of Ephesus's perception of women and menstruation?

Pliny the Elder: Natural History

Pliny the Elder was a Roman author and philosopher most notably known for his work ‘Natural History’. In the following text, Pliny discusses the dangers of menstrual blood.

“But it is not easy that anything should be discovered that is more monstrous than woman’s menstrual fluid. New wine turns sour by coming near it, crops that are touched become barren, grafts whither, seeds of the garden dry up, fruit of trees by which she sits falls off, the brightness of mirrors are dimmed by reflecting her, the edge of iron is dulled, the brightness of ivory, beehives die, bronze and even iron are seized by rust, and the air is seized by an awful smell. Dogs become rabid by tasting it and their bite is infected by an incurable poison. In fact, bitumen, too, which has an otherwise pliable and sticky nature and which floats at certain times of the year on the lake of Judaea, which is called Asphaltites, is not able to be divided up, as it sticks to everything it makes contact with, except a thread which is infected with this slime. Also ants, the tiniest animal, and sensitive to its presence, reject the tasty fruit which it was carrying never to return to it again.”

Coughlin, S. (2022). Aristotle on menstruating women and mirrors — Ancient Medicine. [online] Ancient Medicine. Available at: <https://www.ancientmedicine.org/home/2020/7/26/aristotle-on-menstruating-women-and-mirrors> [Accessed 14 October 2022].

Questions:

“But it is not easy that anything should be discovered that is more monstrous than woman’s menstrual fluid. New wine turns sour by coming near it, crops that are touched become barren, grafts whither, seeds of the garden dry up, fruit of trees by which she sits falls off, the brightness of mirrors are dimmed by reflecting her, the edge of iron is dulled, the brightness of ivory, beehives die, bronze and even iron are seized by rust, and the air is seized by an awful smell. Dogs become rabid by tasting it and their bite is infected by an incurable poison. In fact, bitumen, too, which has an otherwise pliable and sticky nature and which floats at certain times of the year on the lake of Judaea, which is called Asphaltites, is not able to be divided up, as it sticks to everything it makes contact with, except a thread which is infected with this slime. Also ants, the tiniest animal, and sensitive to its presence, reject the tasty fruit which it was carrying never to return to it again.”

Coughlin, S. (2022). Aristotle on menstruating women and mirrors — Ancient Medicine. [online] Ancient Medicine. Available at: <https://www.ancientmedicine.org/home/2020/7/26/aristotle-on-menstruating-women-and-mirrors> [Accessed 14 October 2022].

Questions:

- What does Pliny the Elder believe that menstruation blood does?

- What misogynistic (fearful or hateful) ideas about women can you find in this document?

- What can you infer about Pliny the Elder's perception of women and menstruation?

Sotira: Efficacy of Menstrual Fluid

Although little is known about Sotira, we believe she was a Roman midwife. Her work now only exists in small fragments. The following document discusses the magical properties of menstrual fluid.

“To anoint the soles of the patient's feet with menstrual fluid is the most efficacious cure for tertian and quartan malaria; it is much more effective if it is done by the woman herself without the patient's knowledge. The same remedy also awakens an epileptic.”

Tan. D. A, Haththotuwa. R, Fraser. I. S (2017) ‘Cultural aspects and mythologies surrounding menstruation and abnormal uterine bleeding’ In Best Practice and Research Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. Amsterdam: Elseiver

Questions:

“To anoint the soles of the patient's feet with menstrual fluid is the most efficacious cure for tertian and quartan malaria; it is much more effective if it is done by the woman herself without the patient's knowledge. The same remedy also awakens an epileptic.”

Tan. D. A, Haththotuwa. R, Fraser. I. S (2017) ‘Cultural aspects and mythologies surrounding menstruation and abnormal uterine bleeding’ In Best Practice and Research Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. Amsterdam: Elseiver

Questions:

- What does Sotira believe that menstruation blood does?

- What can you infer about Sotira's perception of women and menstruation?

Unknown: Papyrus Ebers

The Papyrus ebers are a group of Egyptian medical texts containing herbal formulas and mythical remedies to cure an array of ailments.

‘If you examine a woman having pain in her stomach while hsmn (meaning menstruation) does not come for her, and you find (. . .), then you shall say concerning it: this is a case of obstruction of the blood in her uterus. If you examine a woman who has spent many years while hsmn does not come for her, she habitually spews up something like water, her stomach being like that which is under fire, but it stops when she has spewed up, then you shall say concerning it: this is an accumulation of blood in her uterus because she is bewitched. If you examine a woman having pain in one side of her vulva, you should say concerning it: this means that her hsmn has lost its regularity. When it (i.e., the hsmn) has started, you shall make for her: smashed garlic, cider and sawdust of fir tree. Her pubic region is to be bandaged with it’

This short text is also an extract from the Papyrus Ebers and discusses some medicinal use of menstrual blood.

“sagging breasts should be covered with menstrual blood, and the woman's belly and her thighs should be covered as well”

Frandsen. P. J (2007) ‘The Menstrual “Taboo” in Ancient Egypt’ In Journal of Near Eastern Studies, Vol. 66, No. 2, pp.81-206. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Questions:

‘If you examine a woman having pain in her stomach while hsmn (meaning menstruation) does not come for her, and you find (. . .), then you shall say concerning it: this is a case of obstruction of the blood in her uterus. If you examine a woman who has spent many years while hsmn does not come for her, she habitually spews up something like water, her stomach being like that which is under fire, but it stops when she has spewed up, then you shall say concerning it: this is an accumulation of blood in her uterus because she is bewitched. If you examine a woman having pain in one side of her vulva, you should say concerning it: this means that her hsmn has lost its regularity. When it (i.e., the hsmn) has started, you shall make for her: smashed garlic, cider and sawdust of fir tree. Her pubic region is to be bandaged with it’

This short text is also an extract from the Papyrus Ebers and discusses some medicinal use of menstrual blood.

“sagging breasts should be covered with menstrual blood, and the woman's belly and her thighs should be covered as well”

Frandsen. P. J (2007) ‘The Menstrual “Taboo” in Ancient Egypt’ In Journal of Near Eastern Studies, Vol. 66, No. 2, pp.81-206. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Questions:

- What does this text believe that menstruation blood does?

- What does this text believe about illness related to mensuration?

Hippocrates: Nature of Women

Nature of Women is a text compiled by Hippocratic authors, or students of Hippocrates, on gynecology. Hippocrates is often regarded as the father of modern medicine, which is strange because he wrote in ancient history. In ancient and classical Greece it was believed that the womb could move around freely in the women’s body resulting in medical problems. When we investigate it, this theory is rooted in misogyny with the womb becoming a weakness and procreation often becoming the solution.

Vocabulary:

This is my account of the nature and diseases of women: the most important factor in human affairs is the divine; then the natures of women, and their complexions: for very white women are moister and more subject to fluxes, and dark women are drier and more constricted, whereas wine-colored women have something of both.

The ages of life have the following significance: young women are generally moister and richer in blood, while old women are drier and have less blood: those between the two have something of both. A person who manages these matters correctly must begin from divine factors, and then distinguish the natures of women, their ages, the seasons, and the places where they happen to be; for cold places promote fluxes, while hot ones are drying and constipating.…

If a woman’s uterus moves against her liver, she will suddenly lose her speech, grind her teeth, and take on a livid [furious] coloring—these things befall her suddenly while she is in a healthy state. This happens to unmarried women, especially if they are advanced in age and widowed, but also if they are young and widowed after having had children.

When the case is such, push the uterus down away from the liver, and bind it with a band under the patient’s hypochondria [excessively and unnecessarily worried about being sick]. Open her mouth and pour in very fragrant wine, and hold evil-smelling fumigants under her nostrils and fragrant ones below her uterus. When the woman comes to her senses, have her:

If a woman’s uterus advances and moves outside [the 21st century medical term for this is a “prolapsed uterus,” which can occur after birth]... and irritates her. She suffers these things… after having given birth, she does not sleep with her husband. When the case is such:

If the uterus descends completely out of the genitalia, it hangs like a scrotum, pain occupies the lower abdomen and loins, and when the pain has set in, it (i.e., the uterus) is unwilling to return to its place. This condition comes on when after giving birth a woman strains her uterus, or sleeps with her husband during her lochial flow [bleeding after birth]. When the case is such, cooling compresses must be applied to the genitalia, and the part outside must be cleaned off; boil pomegranate in dark wine, and after washing with this replace the uterus inside, and then inject a mixture of honey and resin.

Hippocrates, Nature of Women, circa 440 and 360 BCE, Translation by Potter. P (Cambridge: Loeb Classical Library, 2012).

Questions

Vocabulary:

- hypochondria: In Hippocratic medicine the "hypochondria" was the part of the abdomen between the ribs and the navel. Hippocrates is saying to bind the patient there to prevent her uterus squeezing up against her liver. The meaning of this word has changed. Modern day it means excessively and unnecessarily worried about being sick.

- fumigate: use chemicals that produce good smelling fumes for cleansing

- genitalia: sexual organs, in women this includes the vulva, vagina, uterus, fillopian tubes, etc.

- lochia flow: the normal bleeding after giving birth, which usually lasts for six weeks

This is my account of the nature and diseases of women: the most important factor in human affairs is the divine; then the natures of women, and their complexions: for very white women are moister and more subject to fluxes, and dark women are drier and more constricted, whereas wine-colored women have something of both.

The ages of life have the following significance: young women are generally moister and richer in blood, while old women are drier and have less blood: those between the two have something of both. A person who manages these matters correctly must begin from divine factors, and then distinguish the natures of women, their ages, the seasons, and the places where they happen to be; for cold places promote fluxes, while hot ones are drying and constipating.…

If a woman’s uterus moves against her liver, she will suddenly lose her speech, grind her teeth, and take on a livid [furious] coloring—these things befall her suddenly while she is in a healthy state. This happens to unmarried women, especially if they are advanced in age and widowed, but also if they are young and widowed after having had children.

When the case is such, push the uterus down away from the liver, and bind it with a band under the patient’s hypochondria [excessively and unnecessarily worried about being sick]. Open her mouth and pour in very fragrant wine, and hold evil-smelling fumigants under her nostrils and fragrant ones below her uterus. When the woman comes to her senses, have her:

- drink a… medication

- and after that ass’s milk

- and then fumigate [use a chemical that produces fumes] her uterus with fragrant [good smelling] substances

- apply a preparation of buprestis

- and on the next day oil of bitter almonds

- leave two days free, and then flush her uterus with fragrant substances

- on the next day apply pennyroyal

- leave one day free and then fumigate with aromatic [good smelling] herbs.

If a woman’s uterus advances and moves outside [the 21st century medical term for this is a “prolapsed uterus,” which can occur after birth]... and irritates her. She suffers these things… after having given birth, she does not sleep with her husband. When the case is such:

- boil myrtle and the sawdust of nettle-tree wood in water

- set this out in the open air, and have the patient pour it as cold as possible onto her genitalia [vulva and vagina]

- also grind this fine and apply it as a plaster.

- Then have her vomit, by drinking lentil water, honey and vinegar, until her uterus is restored to its natural position.

- Positioning her bed with the foot end higher, fumigate beneath her genitalia with evil-smelling substances, and under her nostrils with fragrant ones.

- Have her employ foods that are very mild and cold, drink dilute white wine, and without having a bath sleep with her husband.

If the uterus descends completely out of the genitalia, it hangs like a scrotum, pain occupies the lower abdomen and loins, and when the pain has set in, it (i.e., the uterus) is unwilling to return to its place. This condition comes on when after giving birth a woman strains her uterus, or sleeps with her husband during her lochial flow [bleeding after birth]. When the case is such, cooling compresses must be applied to the genitalia, and the part outside must be cleaned off; boil pomegranate in dark wine, and after washing with this replace the uterus inside, and then inject a mixture of honey and resin.

Hippocrates, Nature of Women, circa 440 and 360 BCE, Translation by Potter. P (Cambridge: Loeb Classical Library, 2012).

Questions

- Based off this text, how is age believed to impact women's health?

- What do you think of some of the Hippocratic author’s prescribed solutions? Why?

- Examine the underlined text. Here the Hippocratic author blames women for having a prolapsed uterus, a rare, serious, and painful medical condition where the uterus falls out after birth. What does he accuse them of doing?

- Why might beliefs placing blame on women for their painful conditions be dangerous for women?

Hippocrates: Diseases of Young Girls

Yet another of Hippocrates works, Diseases of Young Girls focuses on the treatment of young girls after puberty. Again, we see this idea of women as the ‘weaker’ sex and the decision not to marry as the cause of their illnesses.

Vocabulary:

[C]oncerning terrors of the sort that people fear so strongly, that they are beside themselves and seem to see certain hostile spirits, sometimes by night, sometimes by day, and sometimes at both times… as a result of this kind of vision, many have already hanged themselves, more women than men, for female nature is weaker and more troublesome.

Young girls of an age for marriage, who remain unmarried, suffer this especially at the time of the descent of their menses [period]. Before puberty they were healthy. Afterwards blood is gathered into their wombs for evacuation. Yet, when the mouth of the exit is not opened and more blood flows in due to their nourishment and the increase of their body, then the blood, not having a way to flow out, rushes from the quantity towards the heart and the diaphragm. When these parts are filled, the heart becomes numb; then lethargy [laziness] seizes them after the numbness, then after the lethargy, madness seizes them… When these things occur in this way, the young girl is mad from the intensity of the inflammation; she turns murderous from the putrefaction; she feels fears and terrors from the darkness. From the pressure around the heart, these young girls long for nooses. Their spirit, distraught and sorely troubled by the foulness of their blood, attracts bad things, but names something else, even fearful things. They command the young girl to wander about, to cast herself into wells, and to hang herself, as if these actions were preferable and completely useful. Even when without visions, a certain pleasure exists, as a result of which she longs for death, as if something good.

When the female is recovering her senses, the women dedicate to Artemis many other things and especially expensive female clothing at the orders of the goddess's priests. But the women are being deceived. Release from this comes whenever there is no impediment for the flowing out of the blood. I urge, then whenever young girls suffer this kind of malady [sickness] they should as quickly as possible… become pregnant, they become healthy. If not, either at the same moment as puberty, or later, she will be caught by this sickness, if not by another

Hippocrates, Peri Parthenion (Diseases of Young Girls). Translated by Flemming. R, Hanson. A. E. (Leiden:Brill, 1998).

Guiding Questions

Vocabulary:

- menses: period

- womb: uterus

- diaphragm: part of their lungs

- lethargy: laziness

- malady: sickness