11. 300-900 The Age of Queens and Empresses

|

All around the world, in the early middle ages, women rose to power-- to the top of the hierarchy. The experiences of these women and those they ruled set precedents that lingered. They ruled differently then men, fought hard to consolidate power, and had to consider carefully how marriage and children would shift their hold on power.

|

The medieval era Europe proved to be a Golden Age for the Byzantines and China. In most places, events of the time served as harsh lessons in female leadership. Across the world, women rose to top positions in monarchies and empires but their successors tried to cover up the legacies of power held by these incredible Queens and Empresses, which tells us a great deal about these societies and the space they allowed for women at least in retrospect.

Byzantine Empire

With the collapse of the western Roman empire, the eastern Roman empire or Byzantium experienced a Golden Age. For women, this was a period of transition from pagan to Christian theology, a transition from diverse deities that included the feminine, to the acceptance of an all male God. Women had been instrumental in the spreading of Christianity, and many became martyrs in the quest to spread the gospel. Despite the instrumental role of women, the spread of Christianity ultimately led to further subordination as the patriarchal governing structures adopted it.

Byzantine Empire

With the collapse of the western Roman empire, the eastern Roman empire or Byzantium experienced a Golden Age. For women, this was a period of transition from pagan to Christian theology, a transition from diverse deities that included the feminine, to the acceptance of an all male God. Women had been instrumental in the spreading of Christianity, and many became martyrs in the quest to spread the gospel. Despite the instrumental role of women, the spread of Christianity ultimately led to further subordination as the patriarchal governing structures adopted it.

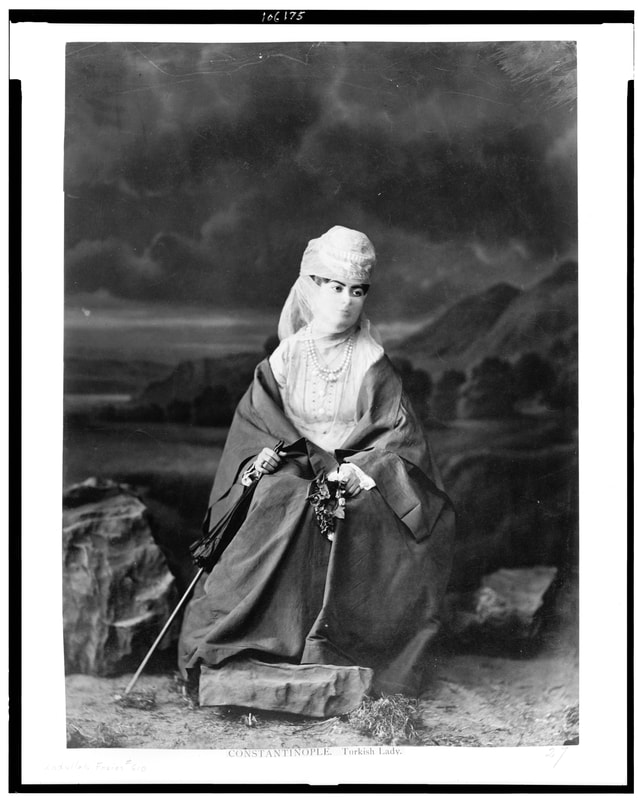

Mary of Egypt, Wikimedia Commons

Mary of Egypt, Wikimedia Commons

Constantine was tolerant of all religions in the empire and eventually accepted Christianity to some extent. His conversion ended the long persecution of Christians and began the process of repressing pagan practices. The altar to the Goddess of Victory was removed from the Senate House. But pagans still existed and led throughout the Empire. Byzantium was importantly inclusive, as the empire was vast and expansive. People of different ethnicities, backgrounds, and cultures thrived within the empire. Even its definition of gender was less restrictive and binary. Mary of Egypt, considered a saint in the eastern orthodox Christian tradition, achieved Sainthood after she gave up prostitution for a pious life in the desert. She cut her hair and impersonated a man. She is depicted in Byzantine art as masculine, with short hair and no curves. Notably different from depictions of the feminine Virgin Mary for example. This was a common trope of the era: women could attain holiness and male-like virtue by transcending the limitations of their sex.

It is in this context that female leaders rose to power in Byzantium, although none ruled the empire out right, but rather as a consort to the emperor. Most of the wives of the emperors are known and recorded in history, but several Byzantine empresses are notable for interesting reasons.

Helena was the mother of Constantine the Great. Her origins were likely humble. She may have even been a prostitute, because she later became a concubine to Constantius (Constantine’s father). She briefly disappears from the historic record and reemerges when her son becomes emperor. In 306 CE, Helena moved to his court. Constantine elevated her to Augusta, which means that she was considered an empress and a holy person.

It is in this context that female leaders rose to power in Byzantium, although none ruled the empire out right, but rather as a consort to the emperor. Most of the wives of the emperors are known and recorded in history, but several Byzantine empresses are notable for interesting reasons.

Helena was the mother of Constantine the Great. Her origins were likely humble. She may have even been a prostitute, because she later became a concubine to Constantius (Constantine’s father). She briefly disappears from the historic record and reemerges when her son becomes emperor. In 306 CE, Helena moved to his court. Constantine elevated her to Augusta, which means that she was considered an empress and a holy person.

Fausta, Wikimedia Commons

Fausta, Wikimedia Commons

Fausta

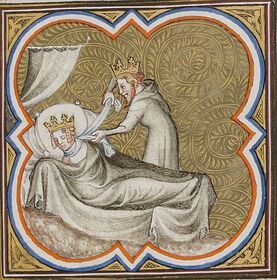

Constantine‘s wife, Fausta, is also interesting here because her inclusion in history shed a different light on Constantine’s legacy. According to some accounts, she died in a bath and he was blamed by his critics for her death. A bath is not a traditional location for execution, and this fact has puzzled historians. The official version of the story is that Fausta accused Constatine’s oldest son from a previous marriage of raping her. Constantine, believing her, had his oldest son and heir promptly executed, before his mother Helena could intervene and convince him that perhaps Fausta had lied.

Constantine then turned his rage on Fausta and had her locked and smothered in a bath. But a modern theory suggests that the affair was consensual, as the son was closer to her age than Constantine, and she died in the bath having an abortion to cover it up. Whether her death was an accident, murder, or she was forced to have an abortion is uncertain. But we do know that she was locked in the spa and she died. For Constantine, wives were disposable. Fausta had given birth to three future emperors. Her death reveals much about the rights of elite men compared to the rights of elite women. It also tells us that abortion practices were known.

Helena was distraught by these events and left on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. According to tradition, Helena found three crosses, including perhaps the most valuable relic to Christians: the cross and nails from the crucifixion of Jesus Christ. Three people touched the cross and the third was healed. Helena constructed two churches in Jerusalem.

Constantine‘s wife, Fausta, is also interesting here because her inclusion in history shed a different light on Constantine’s legacy. According to some accounts, she died in a bath and he was blamed by his critics for her death. A bath is not a traditional location for execution, and this fact has puzzled historians. The official version of the story is that Fausta accused Constatine’s oldest son from a previous marriage of raping her. Constantine, believing her, had his oldest son and heir promptly executed, before his mother Helena could intervene and convince him that perhaps Fausta had lied.

Constantine then turned his rage on Fausta and had her locked and smothered in a bath. But a modern theory suggests that the affair was consensual, as the son was closer to her age than Constantine, and she died in the bath having an abortion to cover it up. Whether her death was an accident, murder, or she was forced to have an abortion is uncertain. But we do know that she was locked in the spa and she died. For Constantine, wives were disposable. Fausta had given birth to three future emperors. Her death reveals much about the rights of elite men compared to the rights of elite women. It also tells us that abortion practices were known.

Helena was distraught by these events and left on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. According to tradition, Helena found three crosses, including perhaps the most valuable relic to Christians: the cross and nails from the crucifixion of Jesus Christ. Three people touched the cross and the third was healed. Helena constructed two churches in Jerusalem.

Theodora, Wikimedia Commons

Theodora, Wikimedia Commons

The empire grew and thrived over the next several centuries and by the sixth century reached its golden age. Here and across the globe, a woman’s class status and path to power were often remarkable. Women had incredible rags to riches stories, as some of the most powerful women in world history began their live as slaves and prostitutes.

Theodora reigned as empress of the Byzantine Empire alongside her husband, Emperor Justinian I, from 527 CE until her death in 548 CE. She came to the court as an actress, stripper, and possibly a prostitute who won a beauty contest, capturing the heart of Justinian. After their marriage, they ruled the empire together. Everything we know about her comes from biased contemporary historians: one is the court history written by Procopius and ordered by Justinian, and the other is a Secret History, also by Procopius, that considers Justinian and Theodora to be the worst thing to happen to Byzantium. Sources from the period are problematic with regard to Theodora, as they are all written by men. A Byzantine woman doing anything but being pretty and submissive would have been seen as improper. Procopius said she was scheming, unprincipled, and immoral– as most assertive and powerful women were often portrayed. He wrote of lurid sexual scandals she was supposedly involved in. In spite of her portrayal in the “official” historian, Theodora was a valuable partner who was directly involved in state affairs.

During a riot in Constantinople, Theodora convinced Justinian not to flee. Procopius credited her with saying:

"I do not care whether or not it is proper for a woman to give brave counsel to frightened men; but in moments of extreme danger, conscience is the only guide. Every man who is born into the light of day must sooner or later die; and how can an Emperor ever allow himself to become a fugitive? If you, my Lord, wish to save your skin, you will have no difficulty in doing so. We are rich, there is the sea, there too are our ships. But consider first whether, when you reach safety, you will not regret that you did not choose death in preference. As for me, I stand by the ancient saying: royalty makes the best shroud.”

Theodora’s influence was palpable everywhere. She contributed to the downfall of prominent men, including a pope– it’s no wonder Procopius wrote so poorly of her. Theodora was known for her social reforms and her charitable work at orphanages, hospitals, and a home for former prostitutes seeking to reenter respectable society. When Justinian fell ill with Bubonic plague that was ravaging the world, Theodora ruled alone, demonstrating control, political savvy, and perhaps some vindictiveness against her court rivals. After her death, Justinian's leadership suffered significantly.

Theodora reigned as empress of the Byzantine Empire alongside her husband, Emperor Justinian I, from 527 CE until her death in 548 CE. She came to the court as an actress, stripper, and possibly a prostitute who won a beauty contest, capturing the heart of Justinian. After their marriage, they ruled the empire together. Everything we know about her comes from biased contemporary historians: one is the court history written by Procopius and ordered by Justinian, and the other is a Secret History, also by Procopius, that considers Justinian and Theodora to be the worst thing to happen to Byzantium. Sources from the period are problematic with regard to Theodora, as they are all written by men. A Byzantine woman doing anything but being pretty and submissive would have been seen as improper. Procopius said she was scheming, unprincipled, and immoral– as most assertive and powerful women were often portrayed. He wrote of lurid sexual scandals she was supposedly involved in. In spite of her portrayal in the “official” historian, Theodora was a valuable partner who was directly involved in state affairs.

During a riot in Constantinople, Theodora convinced Justinian not to flee. Procopius credited her with saying:

"I do not care whether or not it is proper for a woman to give brave counsel to frightened men; but in moments of extreme danger, conscience is the only guide. Every man who is born into the light of day must sooner or later die; and how can an Emperor ever allow himself to become a fugitive? If you, my Lord, wish to save your skin, you will have no difficulty in doing so. We are rich, there is the sea, there too are our ships. But consider first whether, when you reach safety, you will not regret that you did not choose death in preference. As for me, I stand by the ancient saying: royalty makes the best shroud.”

Theodora’s influence was palpable everywhere. She contributed to the downfall of prominent men, including a pope– it’s no wonder Procopius wrote so poorly of her. Theodora was known for her social reforms and her charitable work at orphanages, hospitals, and a home for former prostitutes seeking to reenter respectable society. When Justinian fell ill with Bubonic plague that was ravaging the world, Theodora ruled alone, demonstrating control, political savvy, and perhaps some vindictiveness against her court rivals. After her death, Justinian's leadership suffered significantly.

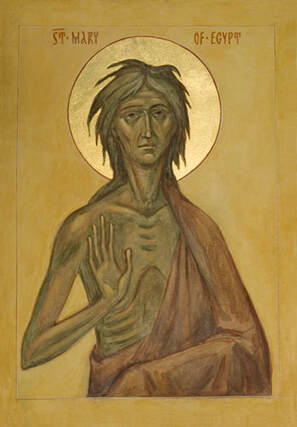

Radegund in 11th Century painting, Wikimedia Commons

Radegund in 11th Century painting, Wikimedia Commons

Francia

Theodora would have been in contact with other queens across the globe, particularly in Europe. Western Europe was politically turbulent compared to Byzantium. Instead of a unified empire, warlords referred to themselves as "kings" and emulated Roman customs. Our knowledge of women from this era primarily comes from Gregory, Bishop of Tours, through his work "The Ten Books of History." Gregory displayed biases favoring certain women over others and often relied on common stereotypes about women.

Consider Radegund, for instance. She resided in Francia (modern-day France) and was a Thuringian princess who witnessed the murder of her family before being captured and compelled to marry her enemy. Her writings provide profound psychological insight into the impact of conflict on elite women during that time. Radegund displayed agency by rejecting the advances of the king and dedicating herself to the church. Eventually, she convinced him to allow her to live in a convent, where she flourished. Her church became one of Western Europe's most powerful and influential after she successfully acquired a piece of Helena's true cross of Christ. For Radegund, the opportunity to study, serve, and escape her husband's clutches must have been a great relief.

Theodora would have been in contact with other queens across the globe, particularly in Europe. Western Europe was politically turbulent compared to Byzantium. Instead of a unified empire, warlords referred to themselves as "kings" and emulated Roman customs. Our knowledge of women from this era primarily comes from Gregory, Bishop of Tours, through his work "The Ten Books of History." Gregory displayed biases favoring certain women over others and often relied on common stereotypes about women.

Consider Radegund, for instance. She resided in Francia (modern-day France) and was a Thuringian princess who witnessed the murder of her family before being captured and compelled to marry her enemy. Her writings provide profound psychological insight into the impact of conflict on elite women during that time. Radegund displayed agency by rejecting the advances of the king and dedicating herself to the church. Eventually, she convinced him to allow her to live in a convent, where she flourished. Her church became one of Western Europe's most powerful and influential after she successfully acquired a piece of Helena's true cross of Christ. For Radegund, the opportunity to study, serve, and escape her husband's clutches must have been a great relief.

Chilperic strangles Galswintha, Wikimedia Commons

Chilperic strangles Galswintha, Wikimedia Commons

Upon her husband's death, he left behind five sons from different marriages, having unified Francia under the Merovingian family through warfare and violence. However, after his demise, his kingdom was divided among four of his sons, not the illegitimate one. The two youngest sons inherited smaller portions of the kingdom and spent their lives attempting to expand their territories by warring against their brothers. The third son waited until he was older to marry a princess, legitimizing his claims. Brunhild, a Visigoth Princess from Spain, received land and an elaborate Roman-style wedding to strengthen the alliance between the Visigoths and Francia.

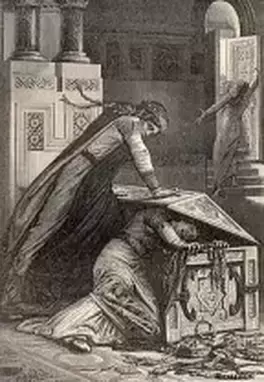

The fourth son married thrice in his life and was notorious for his involvement with enslaved palace women. His second wife was Galswintha, Brunhild's older sister, who married him on the condition that he would give up this habit. However, shortly after their marriage, Galswintha discovered he had resumed his affairs with a servant named Fredegund. Tragically, Galswintha was found dead in her bed, and within a month, Fredegund married the king, initiating a string of at least 12 murders attributed to this ambitious queen. As the king's third wife, Fredegund had to deal with the legitimacy of her stepchildren and plotted to endanger them, ensuring her own children would ascend to power and inherit the kingdom. Fredegund's life was marked by violence, deception, and assassination to maintain her hold on power. After murdering Brunhild's sister, she went on to kill her own husband as well. The rivalry between these two queens appears to be a tale straight out of a storybook. However, it is crucial to approach these accounts with skepticism, given Gregory's inclination to portray Fredegund as a femme fatale in contrast to Brunhild's heroic image.

The fourth son married thrice in his life and was notorious for his involvement with enslaved palace women. His second wife was Galswintha, Brunhild's older sister, who married him on the condition that he would give up this habit. However, shortly after their marriage, Galswintha discovered he had resumed his affairs with a servant named Fredegund. Tragically, Galswintha was found dead in her bed, and within a month, Fredegund married the king, initiating a string of at least 12 murders attributed to this ambitious queen. As the king's third wife, Fredegund had to deal with the legitimacy of her stepchildren and plotted to endanger them, ensuring her own children would ascend to power and inherit the kingdom. Fredegund's life was marked by violence, deception, and assassination to maintain her hold on power. After murdering Brunhild's sister, she went on to kill her own husband as well. The rivalry between these two queens appears to be a tale straight out of a storybook. However, it is crucial to approach these accounts with skepticism, given Gregory's inclination to portray Fredegund as a femme fatale in contrast to Brunhild's heroic image.

Fredegund attacking her own daughter, Wikimedia Commons

Fredegund attacking her own daughter, Wikimedia Commons

Brunhild was not a weak queen; she was a master of politics, having been trained and prepared her whole life to be a queen. Brunhild established alliances to secure her power, negotiated prominent marriages for her daughter and granddaughters, oversaw a trial as the first queen of the medieval era, and was a lead negotiator in the first treaty of Western Europe. Despite the prevailing disapproval of female leaders, her contemporaries had to acknowledge her exceptional abilities.

These two rival queens held onto power for nearly a century, providing the stability that their sons could not. Their reigns encompassed modern-day France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, western and southern Germany, and parts of Switzerland. In the medieval period, only Charlemagne briefly controlled more territory than these two women. Despite various husbands and sons coming and going, these queens ensured consistency in their realms. Whenever diplomatic letters were addressed to their male offspring and grandsons, the queens would reply using their own names and titles, Domina Regina. Pope Gregory, later known as Gregory the Great, recognized where true power resided and never made the mistake of addressing them incorrectly, referring to Brunhild as Queen of the Franks.

Brunhild was concerned about her legacy and, after securing her kingdoms, focused on church work. In alliance with the Pope, she supported the mission to convert pagans in Britain. In contrast, Fredegund continuously sought to expand her kingdom, displaying exceptional strategic prowess. One notable instance was her use of a unique strategy involving her soldiers holding sticks resembling trees to advance at night, pre-dating other references to such tactics. Instead of promoting God's work, she used the spoils of war to reward loyal bishops and buy the church's favor. Her life was marked by manipulation, involving at least twelve credible murders, and a decade as queen regent for her son. Fredegund died without much fanfare, while Brunhild outlived many of her contemporaries and champions, including Pope Gregory. She even outlived both of her children and most of her grandchildren.

These two rival queens held onto power for nearly a century, providing the stability that their sons could not. Their reigns encompassed modern-day France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, western and southern Germany, and parts of Switzerland. In the medieval period, only Charlemagne briefly controlled more territory than these two women. Despite various husbands and sons coming and going, these queens ensured consistency in their realms. Whenever diplomatic letters were addressed to their male offspring and grandsons, the queens would reply using their own names and titles, Domina Regina. Pope Gregory, later known as Gregory the Great, recognized where true power resided and never made the mistake of addressing them incorrectly, referring to Brunhild as Queen of the Franks.

Brunhild was concerned about her legacy and, after securing her kingdoms, focused on church work. In alliance with the Pope, she supported the mission to convert pagans in Britain. In contrast, Fredegund continuously sought to expand her kingdom, displaying exceptional strategic prowess. One notable instance was her use of a unique strategy involving her soldiers holding sticks resembling trees to advance at night, pre-dating other references to such tactics. Instead of promoting God's work, she used the spoils of war to reward loyal bishops and buy the church's favor. Her life was marked by manipulation, involving at least twelve credible murders, and a decade as queen regent for her son. Fredegund died without much fanfare, while Brunhild outlived many of her contemporaries and champions, including Pope Gregory. She even outlived both of her children and most of her grandchildren.

Death of Brunhild, Wikimedia Commons

Death of Brunhild, Wikimedia Commons

Brunhild revived old Roman trading networks and roads, showed mercy to her rival's living son, advocated for battered women, and exhibited tolerance towards Jews in her kingdom. Many of her reforms necessitated raising taxes on the aristocracy and the church, both of whom sought exemptions or worked against her.

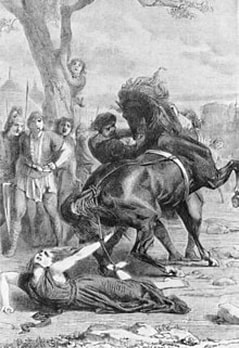

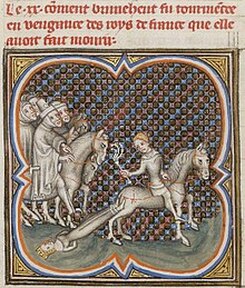

However, in her seventies, Brunhild and her four grandsons met their demise shortly after their father's untimely death, despite having finally united the Franks. The boys, none older than eleven, went to war against Fredegund's son and were betrayed by their Mayor of the Palace. One boy managed to escape, the youngest was sent to be raised by their enemies, and the two eldest were executed. Brunhild, in her old age, might have expected exile or confinement to a convent, but instead, she suffered a brutal and public death, reserved usually for kings: whipped, bloodied, and paraded before the masses before being trampled by a wild horse. She was accused of all of Fredegund's crimes and labeled a king killer.

This violent death can be attributed to the threat she posed to the new King's claim to power, given she was the most influential person in Western Europe. He and his chroniclers utilized the same old tactics of blaming women to elevate their male hero.

King Chlothar II, Fredegund's only surviving son, and the betraying aristocracy signed the Edict of Paris, which essentially curtailed the powers of the King and granted lifetime hereditary appointments to the Mayor of the Palace, who had betrayed Brunhild. This led to the rise of the Carolingians, Charlemagne's great great grandfathers. King Chlothar II erased Brunhild and her entire line from the legal record and made no effort to honor his mother, effectively suppressing knowledge of these two queens for centuries. The Carolingians manipulated history to depict themselves as heroes and vilify their rivals, relying on misogyny as a useful tool.

Nevertheless, women continued to be involved in politics under the Carolingians, such as Charlemagne's influential mother.

However, in her seventies, Brunhild and her four grandsons met their demise shortly after their father's untimely death, despite having finally united the Franks. The boys, none older than eleven, went to war against Fredegund's son and were betrayed by their Mayor of the Palace. One boy managed to escape, the youngest was sent to be raised by their enemies, and the two eldest were executed. Brunhild, in her old age, might have expected exile or confinement to a convent, but instead, she suffered a brutal and public death, reserved usually for kings: whipped, bloodied, and paraded before the masses before being trampled by a wild horse. She was accused of all of Fredegund's crimes and labeled a king killer.

This violent death can be attributed to the threat she posed to the new King's claim to power, given she was the most influential person in Western Europe. He and his chroniclers utilized the same old tactics of blaming women to elevate their male hero.

King Chlothar II, Fredegund's only surviving son, and the betraying aristocracy signed the Edict of Paris, which essentially curtailed the powers of the King and granted lifetime hereditary appointments to the Mayor of the Palace, who had betrayed Brunhild. This led to the rise of the Carolingians, Charlemagne's great great grandfathers. King Chlothar II erased Brunhild and her entire line from the legal record and made no effort to honor his mother, effectively suppressing knowledge of these two queens for centuries. The Carolingians manipulated history to depict themselves as heroes and vilify their rivals, relying on misogyny as a useful tool.

Nevertheless, women continued to be involved in politics under the Carolingians, such as Charlemagne's influential mother.

Empress Suiko, Wikimedia Commons

Empress Suiko, Wikimedia Commons

Japan

Across the world, another queen, Su8ko, was breaking barriers and coming to power.. There was some precedent for female rule. Himiko was an ancient queen of legend, but she is not mentioned in Japanese histories. Historians disagree on where her kingdom was. She was noted for being a shaman queen who never married and lived in a fortress where she was served by 1,000 women.

Suiko, living centuries later, was well documented. She was the daughter of Emperor Kimmei and at 18 became the empress-consort of Emperor Bidatsu, who reigned from 572 to 585. After a short rule by the Emperor Yomei, interclan warfare broke out over succession. Suiko's brother, Emperor Sujun or Sushun, reigned next but was murdered in 592. Her uncle, Soga Umako, a powerful clan leader who was likely behind Sushu's murder, convinced Suiko to take the throne with another of Umako's nephews, Shotoku administered the government as Empress for 30 years.

Empress Suiko is credited with ordering the promulgation of Buddhism, the religion of her family, the Soga, beginning in 594. During her reign, Buddhism became firmly established; the second article of the 17-article constitution instituted under her reign promoted Buddhist worship, and she sponsored Buddhist temples and monasteries.

During Suiko's reign, China first diplomatically recognized Japan, and Chinese influence increased. This included introducing the Chinese calendar and the Chinese system of government bureaucracy. Chinese monks, artists, and scholars also were brought into Japan during her reign. The power of the emperor also became stronger under her rule.

Queen Seondeok, Wikimedia Commons

Queen Seondeok, Wikimedia Commons

Korea

To the north in Korea, Queen Seondeok became the first female monarch in the Kingdom of Silla starting in 632. Her rule laid the groundwork for more female rulers. Unfortunately, so many aspects of her rule have been lost to time.

She ruled for 15 years and used skillful diplomacy to form a strong alliance with Tang China and secure Sillan independence. Her foreign policy allowed Seondeok to form alliances with leading families of Silla. She arranged marriages between prominent families and created a power bloc that unified the Korean Peninsula under her rule and ended the Three Kingdoms period.

Seondeok was challenged by Lord Bidam. He rallied supporters under the motto, "Women rulers cannot rule the country." The legend states that a falling star convinced him that the queen too would fall soon. To counter the narrative, Seondeok flew a flaming kite.

After 10 days, Bidam and his co-conspirators were seized and executed. Seondeok died of natural causes during this time. She, unlike other female monarchs around the world, had the chance to choose a successor and left her kingdom to another woman–her cousin Queen Jindeok.

The fact that another ruling queen followed immediately after Seondeok's reign demonstrates that she was an able and astute ruler. The Silla Kingdom could also boast Korea's third and final female ruler, Queen Jinseong, who ruled nearly two hundred years later from 887 to 897.

To the north in Korea, Queen Seondeok became the first female monarch in the Kingdom of Silla starting in 632. Her rule laid the groundwork for more female rulers. Unfortunately, so many aspects of her rule have been lost to time.

She ruled for 15 years and used skillful diplomacy to form a strong alliance with Tang China and secure Sillan independence. Her foreign policy allowed Seondeok to form alliances with leading families of Silla. She arranged marriages between prominent families and created a power bloc that unified the Korean Peninsula under her rule and ended the Three Kingdoms period.

Seondeok was challenged by Lord Bidam. He rallied supporters under the motto, "Women rulers cannot rule the country." The legend states that a falling star convinced him that the queen too would fall soon. To counter the narrative, Seondeok flew a flaming kite.

After 10 days, Bidam and his co-conspirators were seized and executed. Seondeok died of natural causes during this time. She, unlike other female monarchs around the world, had the chance to choose a successor and left her kingdom to another woman–her cousin Queen Jindeok.

The fact that another ruling queen followed immediately after Seondeok's reign demonstrates that she was an able and astute ruler. The Silla Kingdom could also boast Korea's third and final female ruler, Queen Jinseong, who ruled nearly two hundred years later from 887 to 897.

Wu Zeitan, Wikimedia Commons

Wu Zeitan, Wikimedia Commons

China

Both Theodora and Fredegund found paths to power through prostitution and cruelty, but this wasn’t true only in the west. In China, another empress, Wu Zeitan, was rising: Wu was regarded as one of the cruelest rulers in China’s history, which may say more about the chroniclers than it does about her.

The Tang Dynasty, during which she ruled, was a Golden Age for China, producing gorgeous art and culture. During the Tang, the Silk Roads were at the height of their influence. During Wu’s life, overland trade routes brought significant entrepreneurial opportunities with the West and other parts of Eurasia, making the capital of the Tang Empire the most cosmopolitan of the world’s cities. Merchants dealt for and traded many goods, and commerce involving textiles, minerals, and spices was particularly prominent. With such avenues of contact, Tang China was ready for changes in society and culture. Tang women were assertive, active, and visible; they rode horses, donned male attire, and participated in politics.

Wu was a master of politics. She came to the court as a concubine, one of many, to the emperor. She bore him four sons and earned his favor. She earned the respect of the court and even the Empress, and she knew the ins and outs of court because attendants would report gossip and even trivial events.

Greedy for power, she looked to eliminate the Empress Wang. After giving birth to a baby daughter, she brought her to the empress to hold. When the Empress Wang had played with the baby, Wu killed her own infant daughter and blamed the murder on Empress Wang. The emperor believed this and promoted Wu to Empress. Wu immediately put Wang and her other rivals to death, exiling their families.

She purged the court of those disloyal to her. When the emperor died, her son became emperor, and she a regent where she could rule from the shadows. But this arrangement had its limitations and in 690, she conferred upon herself the title “Holy and Divine Emperor,” founded what she called the “Zhou dynasty” and ruled for the next fifteen years as the only woman emperor in Chinese history until she was finally deposed in a coup.

Male historians recorded her legacy with contempt. Many are quick to point out the horrific and cruel ways with which she ruled. But this was not uncommon for male leaders around the world. It’s important to acknowledge that she ruled in a Golden Age. She recruited qualified officials to do important jobs, helped to spread Buddhism, expanded the empire, and sponsored the writing of agricultural texts to improve production. Finally, Wu represents the rare elite woman to support the women behind her. She campaigned to improve the status of women. She advised scholars to write and edit biographies of exemplary women. Wu believed the ideal emperor was one who ruled as a mother rules over her children.

Both Theodora and Fredegund found paths to power through prostitution and cruelty, but this wasn’t true only in the west. In China, another empress, Wu Zeitan, was rising: Wu was regarded as one of the cruelest rulers in China’s history, which may say more about the chroniclers than it does about her.

The Tang Dynasty, during which she ruled, was a Golden Age for China, producing gorgeous art and culture. During the Tang, the Silk Roads were at the height of their influence. During Wu’s life, overland trade routes brought significant entrepreneurial opportunities with the West and other parts of Eurasia, making the capital of the Tang Empire the most cosmopolitan of the world’s cities. Merchants dealt for and traded many goods, and commerce involving textiles, minerals, and spices was particularly prominent. With such avenues of contact, Tang China was ready for changes in society and culture. Tang women were assertive, active, and visible; they rode horses, donned male attire, and participated in politics.

Wu was a master of politics. She came to the court as a concubine, one of many, to the emperor. She bore him four sons and earned his favor. She earned the respect of the court and even the Empress, and she knew the ins and outs of court because attendants would report gossip and even trivial events.

Greedy for power, she looked to eliminate the Empress Wang. After giving birth to a baby daughter, she brought her to the empress to hold. When the Empress Wang had played with the baby, Wu killed her own infant daughter and blamed the murder on Empress Wang. The emperor believed this and promoted Wu to Empress. Wu immediately put Wang and her other rivals to death, exiling their families.

She purged the court of those disloyal to her. When the emperor died, her son became emperor, and she a regent where she could rule from the shadows. But this arrangement had its limitations and in 690, she conferred upon herself the title “Holy and Divine Emperor,” founded what she called the “Zhou dynasty” and ruled for the next fifteen years as the only woman emperor in Chinese history until she was finally deposed in a coup.

Male historians recorded her legacy with contempt. Many are quick to point out the horrific and cruel ways with which she ruled. But this was not uncommon for male leaders around the world. It’s important to acknowledge that she ruled in a Golden Age. She recruited qualified officials to do important jobs, helped to spread Buddhism, expanded the empire, and sponsored the writing of agricultural texts to improve production. Finally, Wu represents the rare elite woman to support the women behind her. She campaigned to improve the status of women. She advised scholars to write and edit biographies of exemplary women. Wu believed the ideal emperor was one who ruled as a mother rules over her children.

Brunhild's Death, Wikimedia Commons

Brunhild's Death, Wikimedia Commons

ConclusionWomen rulers were possible and somewhat common in monarchies throughout world history. Women came to power as consorts, regents, and through closeness with power, as enslaved people and prostitutes.

We cannot separate the stories of these women from the men who recorded them. So many of them were portrayed as evil, violent, and horrible. It’s possible that they were, but perhaps those chroniclers were unaccustomed to women outside their domestic roles. How different would our knowledge of these women be if women had recorded them?

It’s important to ask how the existence of female rulers influenced the lives of everyday women in the kingdoms. Did they support female education and rights to land ownership and bodily autonomy? How did these women leave space for future female leaders? And was their rule successful?

We cannot separate the stories of these women from the men who recorded them. So many of them were portrayed as evil, violent, and horrible. It’s possible that they were, but perhaps those chroniclers were unaccustomed to women outside their domestic roles. How different would our knowledge of these women be if women had recorded them?

It’s important to ask how the existence of female rulers influenced the lives of everyday women in the kingdoms. Did they support female education and rights to land ownership and bodily autonomy? How did these women leave space for future female leaders? And was their rule successful?

Draw your own conclusions

|

Learn how to teach with inquiry.

Many of these lesson plans were sponsored in part by the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources Eastern Region Program, coordinated by Waynesburg University, the History and Social Studies Education Faculty at Plymouth State University, and the Patrons of the Remedial Herstory Project. |

|

OTHER: Women in Tang China

In this inquiry from Women in World History focuses on the enduring influence of Confucianism on the lives of women in ancient and modern China and Wu Zeitan. Check it out! |

Lesson Plans from Other Organizations

- This website, Women in World History has primary source based lesson plans on women's history in a whole range of topics. Some are free while others have a cost.

- The Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media has produced recommendations for teaching women's history with primary sources and provided a collection of sources for world history. Check them out!

- The Stanford History Education Group has a number of lesson plans about women in World History.

Theodora of Byzantium

Theodora of Byzantium was born around 497 CE to a bear-keeper who worked for the Hippodrome in Constantinople, (a Byzantine arena for chariot racing and other entertainment). Theodora went on to work in the Hippodrome herself as an acrobat, dancer, actress and/or exotic dancer. She gained power after she married Justinian, the nephew of the Emperor Justin. Two years after their marriage, Justinian and Theodora were crowned Emperor and Empress. It appears Justinian actually insisted his wife be crowned as his equal and changed the law to elevate her status (actresses were not allowed to legally marry at the time). Despite the difference in class, such a marriage was not as rare as you might think. Some sources do exist retailing beauty competitions in which the victor would be married to a man from a prestigious position.

Few sources exist on Theorora’s life. The most referenced source is historian Prokopois of Caesarea, who wrote his ‘Secret History’ (Anekota), an outrageous and exaggerated history of Justinian and Theodora. For this reason, much of what we know about Theodora cannot be trusted. What we do know is she appears to have been a brave individual that suited leadership well. In 532 CE, the Nika Revolt saw rioters burn down much of Constantinople and attempt to crown a new emperor. We believe during this revolt, it was Theorora that persuaded the Emperor to stay and fight. We also know that Theorora ruled alone for a year as Justinian recovered from Bubonic Plague in 542 CE, securing her position by removing any threats to her throne. Finally, we know that she was a religious figure and a believer in Monophysitism, a factor of Christianity.

Few sources exist on Theorora’s life. The most referenced source is historian Prokopois of Caesarea, who wrote his ‘Secret History’ (Anekota), an outrageous and exaggerated history of Justinian and Theodora. For this reason, much of what we know about Theodora cannot be trusted. What we do know is she appears to have been a brave individual that suited leadership well. In 532 CE, the Nika Revolt saw rioters burn down much of Constantinople and attempt to crown a new emperor. We believe during this revolt, it was Theorora that persuaded the Emperor to stay and fight. We also know that Theorora ruled alone for a year as Justinian recovered from Bubonic Plague in 542 CE, securing her position by removing any threats to her throne. Finally, we know that she was a religious figure and a believer in Monophysitism, a factor of Christianity.

Procopius of Caesarea: Secret History

Procopius was a 6th century CE historian who wrote many works on Byzantine history. His most famous piece of work today is his Secret History, a scandalous and likely inaccurate historical source primarily on the marriage of Justinian and Theodora.

And he [Justinian] married a wife concerning whom I shall now relate how she was born and reared and how, after being joined to this man in marriage, she overturned the Roman State to its very foundations…

As soon as she came of age and was at last mature, she joined the women of the stage and straightway became a courtesan, of the sort whom men of ancient times used to call "infantry." For she was neither a flute-player nor a harpist, nay, she had not even acquired skill in the dance, but she sold her youthful beauty to those who chanced to come along, plying her trade with practically her whole body.

Later on she was associated with the actors in all the work of the theatre, and she shared their performances with them, playing up to their buffoonish acts intended to raise a laugh. For she was unusually clever and full of gibes, and she immediately became admired for this sort of thing. For the girl had not a particle of modesty, nor did any man ever see her embarrassed, but she undertook shameless services without the least hesitation, and she was the sort of a person who, for instance, when being flogged or beaten over the head, would crack a joke over it and burst into a loud laugh; and she would undress and exhibit to any who chanced along both her front and her rear naked, parts which rightly should be unseen by men and hidden from them.

And as she wantoned with her lovers, she always kept bantering them, and by toying with new devices in intercourse, she always succeeded in winning the hearts of the licentious to her; for she did not even expect that the approach should be made by the man she was with, but on the contrary she herself, with wanton jests and with clownish posturing with her hips, would tempt all who came along, especially if they were beardless youths. …

When she came back to Byzantium once more, Justinian conceived for her an overpowering love; and at first he knew her as a mistress, though he did advance her to the rank of the Patricians. Theodora accordingly succeeded at once in acquiring extraordinary influence and a fairly large fortune. For she seemed to the man the sweetest thing in the world, as is wont to happen with lovers who love extravagantly, and he was fain to bestow upon his beloved all favours and all money. And the State became fuel for this love. So with her help he ruined the people even more than before, and not in Byzantium alone, but throughout the whole Roman Empire.

Prokopius: The Secret History, The Anecdota. [online] Penelope Unhicago Avalible at <http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Procopius/Anecdota/home.html> [Accessed 6/11/2022]

Questions:

And he [Justinian] married a wife concerning whom I shall now relate how she was born and reared and how, after being joined to this man in marriage, she overturned the Roman State to its very foundations…

As soon as she came of age and was at last mature, she joined the women of the stage and straightway became a courtesan, of the sort whom men of ancient times used to call "infantry." For she was neither a flute-player nor a harpist, nay, she had not even acquired skill in the dance, but she sold her youthful beauty to those who chanced to come along, plying her trade with practically her whole body.

Later on she was associated with the actors in all the work of the theatre, and she shared their performances with them, playing up to their buffoonish acts intended to raise a laugh. For she was unusually clever and full of gibes, and she immediately became admired for this sort of thing. For the girl had not a particle of modesty, nor did any man ever see her embarrassed, but she undertook shameless services without the least hesitation, and she was the sort of a person who, for instance, when being flogged or beaten over the head, would crack a joke over it and burst into a loud laugh; and she would undress and exhibit to any who chanced along both her front and her rear naked, parts which rightly should be unseen by men and hidden from them.

And as she wantoned with her lovers, she always kept bantering them, and by toying with new devices in intercourse, she always succeeded in winning the hearts of the licentious to her; for she did not even expect that the approach should be made by the man she was with, but on the contrary she herself, with wanton jests and with clownish posturing with her hips, would tempt all who came along, especially if they were beardless youths. …

When she came back to Byzantium once more, Justinian conceived for her an overpowering love; and at first he knew her as a mistress, though he did advance her to the rank of the Patricians. Theodora accordingly succeeded at once in acquiring extraordinary influence and a fairly large fortune. For she seemed to the man the sweetest thing in the world, as is wont to happen with lovers who love extravagantly, and he was fain to bestow upon his beloved all favours and all money. And the State became fuel for this love. So with her help he ruined the people even more than before, and not in Byzantium alone, but throughout the whole Roman Empire.

Prokopius: The Secret History, The Anecdota. [online] Penelope Unhicago Avalible at <http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Procopius/Anecdota/home.html> [Accessed 6/11/2022]

Questions:

- How reliable is this text and what conclusions can be made about its content?

Judith Herrin: The Imperial Feminine in Byzantium

The following document is an extract from Judith Herrin’s article on imperial women in Byzantium. Herrin shares three ways in which Theodora claimed and secured the throne along with some comments on the reliability of Prokopios.

Theodora, the ex-circus entertainer and one of the most maligned of all imperial brides, [was] chosen by Justinian to share his throne. For Theodora, disguise as a man was out of the question since her power stemmed from her feminine qualities and seductive charms, which fascinated observers. While Prokopios, the sole source for most of our information about her, condemns these powers, on another occasion he presents her as leading the resistance to threatened revolt, putting into her mouth a speech derived from Isokrates, with the glorious message that it is better to die in the imperial purple than to flee in the face of rebellion...

Nonetheless, during the Nika riot in 532, he suggests that Theodora had to apologize for intervening in a male discourse in order to stiffen Justinian's resolve. Some modern commentators have built great theoretical edifices on this passage. They claim that Theodora is here transgressing the established borders of her position as a woman, even if she is the most elevated of all women in the empire…

Of course, we do not know how far the imperial couple shared or disputed power. Prokopios claims that they supported different factions in order to whip up disagreements between their supporters, to raise the tensions which they would later exploit to serve their own imperial purposes. Justinian seems to have consulted Theodora on other matters, not merely what to do about the riot of 532. And Theodora seems to have had control of considerable space of her own where she acted independently, for she hid a Monophysite patriarch inside her private quarters for years. She also tortured and probably killed several individuals whom she accused of serious crimes, trumped-up charges no doubt, but she was able to impose an arbitrary judgement. Theodora used imperial powers to remove her enemies and to force her rivals into marriages she arranged. But nearly all the evidence concerning this particularly brilliant empress derives from the record of Prokopios.

Herrin. J (2000) ‘The Imperial Feminine in Byzantium’ In Past and Present, No. 169, pp. 3-35. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Questions:

How does this text depict how Theorora claimed and then secured her position?

Theodora, the ex-circus entertainer and one of the most maligned of all imperial brides, [was] chosen by Justinian to share his throne. For Theodora, disguise as a man was out of the question since her power stemmed from her feminine qualities and seductive charms, which fascinated observers. While Prokopios, the sole source for most of our information about her, condemns these powers, on another occasion he presents her as leading the resistance to threatened revolt, putting into her mouth a speech derived from Isokrates, with the glorious message that it is better to die in the imperial purple than to flee in the face of rebellion...

Nonetheless, during the Nika riot in 532, he suggests that Theodora had to apologize for intervening in a male discourse in order to stiffen Justinian's resolve. Some modern commentators have built great theoretical edifices on this passage. They claim that Theodora is here transgressing the established borders of her position as a woman, even if she is the most elevated of all women in the empire…

Of course, we do not know how far the imperial couple shared or disputed power. Prokopios claims that they supported different factions in order to whip up disagreements between their supporters, to raise the tensions which they would later exploit to serve their own imperial purposes. Justinian seems to have consulted Theodora on other matters, not merely what to do about the riot of 532. And Theodora seems to have had control of considerable space of her own where she acted independently, for she hid a Monophysite patriarch inside her private quarters for years. She also tortured and probably killed several individuals whom she accused of serious crimes, trumped-up charges no doubt, but she was able to impose an arbitrary judgement. Theodora used imperial powers to remove her enemies and to force her rivals into marriages she arranged. But nearly all the evidence concerning this particularly brilliant empress derives from the record of Prokopios.

Herrin. J (2000) ‘The Imperial Feminine in Byzantium’ In Past and Present, No. 169, pp. 3-35. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Questions:

How does this text depict how Theorora claimed and then secured her position?

Procopius: The Persian Wars

The following extract is from Procopius’ Secret History. This extract details the events of the Nika revolt and Theodora’s influence.

But at this time the officers of the city administration in Byzantium were leading away to death some of the rioters. But the members of the two factions, conspiring together and declaring a truce with each other, seized the prisoners and then straightway entered the prison and released all those who were in confinement there, whether they had been condemned on a charge of stirring up sedition, or for any other unlawful act. And all the attendants in the service of the city government were killed indiscriminately; meanwhile, all of the citizens who were sane-minded were fleeing to the opposite mainland, and fire was applied to the city as if it had fallen under the hand of an enemy. The sanctuary of Sophia and the baths of Zeuxippus, and the portion of the imperial residence from the propylaea as far as the so‑called House of Ares were destroyed by fire, and besides these both the great colonnades which extended as far as the market place which bears the name of Constantine, in addition to many houses of wealthy men and a vast amount of treasure. During this time the emperor and his consort with a few members of the senate shut themselves up in the palace and remained quietly there. Now the watchword which the populace passed around to one another was Nika, and the insurrection has been called by this name up to the present time…

Now the emperor and his court were deliberating as to whether it would be better for them if they remained or if they took to flight in the ships. And many opinions were expressed favouring either course. And the Empress Theodora also spoke to the following effect: "As to the belief that a woman ought not to be daring among men or to assert herself boldly among those who are holding back from fear, I consider that the present crisis most certainly does not permit us to discuss whether the matter should be regarded in this or in some other way. For in the case of those whose interests have come into the greatest danger nothing else seems best except to settle the issue immediately before them in the best possible way. My opinion then is that the present time, above all others, is inopportune for flight, even though it bring safety. For while it is impossible for a man who has seen the light not also to die, for one who has been an emperor it is unendurable to be a fugitive. May I never be separated from this purple, and may I not live that day on which those who meet me shall not address me as mistress. If, now, it is your wish to save yourself, O Emperor, there is no difficulty. For we have much money, and there is the sea, here the boats. However, consider whether it will not come about after you have been saved that you would gladly exchange that safety for death. For as for myself, I approve a certain ancient saying that royalty is a good burial-shroud." When the queen had spoken thus, all were filled with boldness, and, turning their thoughts towards resistance, they began to consider how they might be able to defend themselves if any hostile force should come against them.

Procopius, The Persian Wars - Book 1. Translated by Dweing. H. B (2014) Cambridge: Harvard University Press

But at this time the officers of the city administration in Byzantium were leading away to death some of the rioters. But the members of the two factions, conspiring together and declaring a truce with each other, seized the prisoners and then straightway entered the prison and released all those who were in confinement there, whether they had been condemned on a charge of stirring up sedition, or for any other unlawful act. And all the attendants in the service of the city government were killed indiscriminately; meanwhile, all of the citizens who were sane-minded were fleeing to the opposite mainland, and fire was applied to the city as if it had fallen under the hand of an enemy. The sanctuary of Sophia and the baths of Zeuxippus, and the portion of the imperial residence from the propylaea as far as the so‑called House of Ares were destroyed by fire, and besides these both the great colonnades which extended as far as the market place which bears the name of Constantine, in addition to many houses of wealthy men and a vast amount of treasure. During this time the emperor and his consort with a few members of the senate shut themselves up in the palace and remained quietly there. Now the watchword which the populace passed around to one another was Nika, and the insurrection has been called by this name up to the present time…

Now the emperor and his court were deliberating as to whether it would be better for them if they remained or if they took to flight in the ships. And many opinions were expressed favouring either course. And the Empress Theodora also spoke to the following effect: "As to the belief that a woman ought not to be daring among men or to assert herself boldly among those who are holding back from fear, I consider that the present crisis most certainly does not permit us to discuss whether the matter should be regarded in this or in some other way. For in the case of those whose interests have come into the greatest danger nothing else seems best except to settle the issue immediately before them in the best possible way. My opinion then is that the present time, above all others, is inopportune for flight, even though it bring safety. For while it is impossible for a man who has seen the light not also to die, for one who has been an emperor it is unendurable to be a fugitive. May I never be separated from this purple, and may I not live that day on which those who meet me shall not address me as mistress. If, now, it is your wish to save yourself, O Emperor, there is no difficulty. For we have much money, and there is the sea, here the boats. However, consider whether it will not come about after you have been saved that you would gladly exchange that safety for death. For as for myself, I approve a certain ancient saying that royalty is a good burial-shroud." When the queen had spoken thus, all were filled with boldness, and, turning their thoughts towards resistance, they began to consider how they might be able to defend themselves if any hostile force should come against them.

Procopius, The Persian Wars - Book 1. Translated by Dweing. H. B (2014) Cambridge: Harvard University Press

FREDEGUN AND BRUNHILD

Fredegund was the queen consort of Chilperic I, the Merovingian Frankish King of Soissons. She began life as a servant in the royal house before becoming the king’s mistress. Within a few years, Fredegund had persuaded the king to set aside his first wife and kill his second before finally becoming the queen consort herself. The murder of Chilperic I’s second wife, Galswintha in 568 CE, however, ignited violent animosity between Chilperic and his brother, King Sigbert of Austrasia.

Born around 534 CE, Brunhild (or Brunhilde) was the daughter of the King of Visigoth Spain. She became the queen of Burgundy and Austrasia in 567 CE after she married King Sigebert. The lives of Fredegund and Brunhild begin to intertwine after the murder of Galswintha, Chilperic I’s second wife and Brunhild’s sister. After Fredegund organised the murder or Brunhild’s sister the pair were forced into a fourty-year feud. The feud witnessed an extensive war before Fredegund’s son, Chlotar, triumphed over Brunhild in 613 CE after Fredegund’s death. This led to the rather gruesome execution of Brunhild

Born around 534 CE, Brunhild (or Brunhilde) was the daughter of the King of Visigoth Spain. She became the queen of Burgundy and Austrasia in 567 CE after she married King Sigebert. The lives of Fredegund and Brunhild begin to intertwine after the murder of Galswintha, Chilperic I’s second wife and Brunhild’s sister. After Fredegund organised the murder or Brunhild’s sister the pair were forced into a fourty-year feud. The feud witnessed an extensive war before Fredegund’s son, Chlotar, triumphed over Brunhild in 613 CE after Fredegund’s death. This led to the rather gruesome execution of Brunhild

Gregory of Tours (539-594): Ten Books of Histories Book IV.

Gregory of Tours was an author and historian who wrote about the Merovingian dynasty. He is best known for his work, Libri Historiarum X, or History of the Franks, which follows the Frankish people from creation to the 6th century. Below is an extract from Book Four of his History of the Franks and details the marriage of king Sigibert to Brunhild, the murder of Galswintha and the marriage of Chilperic and Fredegund. (Note that Brunhilda and Brunhilde refer to Brunhild, Fredegunda refers to Fredegund and Galsuenda refers to Galswintha).

Now when king Sigibert saw that his brothers were taking wives unworthy of them, and to their disgrace were actually marrying slave women, he sent an embassy into Spain and with many gifts asked for Brunhilda, daughter of king Athanagild. She was a maiden beautiful in her person, lovely to look at, virtuous and well behaved, with good sense and a pleasant address. Her father did not refuse, but sent her to the king I have named with great treasures. And the king collected his chief men, made ready a feast, and took her as his wife amid great joy and mirth. And though she was a follower of the Arian law she was converted by the preaching of the bishops and the admonition of the king himself, and she confessed the blessed Trinity in unity, and believed and was baptized. And she still remains catholic in Christ's name.

When Chilperic saw this, although he had already too many wives, he asked for her sister Galsuenda, promising through his ambassadors that he would abandon the others if he could only obtain a wife worthy of himself and the daughter of a king. Her father accepted these promises and sent his daughter with much wealth, as he had done before. Now Galsuenda was older than Brunhilda. And coming to king Chilperic she was received with great honor, and united to him in marriage, and she was also greatly loved by him. For she had brought great treasures. But because of his love of Fredegunda whom he had had before, there arose a great scandal which divided them. Galsuenda had already been converted to the catholic law and baptized. And complaining to the king that she was continually enduring outrages and had no honor with him, she asked to leave the treasures which she had brought with her and be permitted to go free to her native land. But he made ingenious pretenses and calmed her with gentle words. At length he ordered her to be strangled by a slave and found her dead on the bed. After the death God caused a great miracle to appear. For the lighted lamp which hung by a rope in front of her tomb broke the rope without being touched by anyone and dashed on the pavement and the hard pavement yielded under it and it went down as if into some soft substance and was buried to the middle but not at all damaged. Which seemed a great miracle to all who saw it. But when the king had mourned her death a few days, he married Fredegunda again. After this action his brothers thought that the queen mentioned above had been killed at his command, and they tried to expel him from the kingdom. Chilperic at that time had three sons by his former wife Audovera, namely Theodobert, whom we have mentioned above, Merovech and Clovis. But let us return to our task.

Medieval SourceBook: Gregory of Tours (539-594): History of the Franks: Books I-X [online] Available at https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/basis/gregory-hist.asp#book1.

Questions:

Now when king Sigibert saw that his brothers were taking wives unworthy of them, and to their disgrace were actually marrying slave women, he sent an embassy into Spain and with many gifts asked for Brunhilda, daughter of king Athanagild. She was a maiden beautiful in her person, lovely to look at, virtuous and well behaved, with good sense and a pleasant address. Her father did not refuse, but sent her to the king I have named with great treasures. And the king collected his chief men, made ready a feast, and took her as his wife amid great joy and mirth. And though she was a follower of the Arian law she was converted by the preaching of the bishops and the admonition of the king himself, and she confessed the blessed Trinity in unity, and believed and was baptized. And she still remains catholic in Christ's name.

When Chilperic saw this, although he had already too many wives, he asked for her sister Galsuenda, promising through his ambassadors that he would abandon the others if he could only obtain a wife worthy of himself and the daughter of a king. Her father accepted these promises and sent his daughter with much wealth, as he had done before. Now Galsuenda was older than Brunhilda. And coming to king Chilperic she was received with great honor, and united to him in marriage, and she was also greatly loved by him. For she had brought great treasures. But because of his love of Fredegunda whom he had had before, there arose a great scandal which divided them. Galsuenda had already been converted to the catholic law and baptized. And complaining to the king that she was continually enduring outrages and had no honor with him, she asked to leave the treasures which she had brought with her and be permitted to go free to her native land. But he made ingenious pretenses and calmed her with gentle words. At length he ordered her to be strangled by a slave and found her dead on the bed. After the death God caused a great miracle to appear. For the lighted lamp which hung by a rope in front of her tomb broke the rope without being touched by anyone and dashed on the pavement and the hard pavement yielded under it and it went down as if into some soft substance and was buried to the middle but not at all damaged. Which seemed a great miracle to all who saw it. But when the king had mourned her death a few days, he married Fredegunda again. After this action his brothers thought that the queen mentioned above had been killed at his command, and they tried to expel him from the kingdom. Chilperic at that time had three sons by his former wife Audovera, namely Theodobert, whom we have mentioned above, Merovech and Clovis. But let us return to our task.

Medieval SourceBook: Gregory of Tours (539-594): History of the Franks: Books I-X [online] Available at https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/basis/gregory-hist.asp#book1.

Questions:

- What does this text tell us about Fredegund and Brunhild and how they both claimed their position as queen? How do they differ?

Venantius Fortunatus: De Sigiberctho Rege et Brunichilde Regina, Lines 9-130

Below are four short extracts from Venatius Fortunatus’ De Sigiberctho rege et Brunichilde regina, also known as ‘On King Sigibert and Queen Brunhild’. Fortunatus was a 6th century Latin poet who recently arrived in Francia from Italy. The piece was recited aloud as part of the wedding celebrations of King Sigibert and Queen Brunhild and an opportunity to show off his literary talent. With this in mind, it is important to question some of the statements made by Fortunatus here. The work is likely more about the expectations of royal women, rather than the reality, since he didn’t know Brunhild.

Fertile in its chaste bed…gets fresh offspring…Christ then joined Queen Brunhild to Himself in love, for her merits, when He gave her to you...before she had pleased only man, however, but now behold she pleases God. … Beautiful, modest, decorous, intelligent, dutiful, pleasing and good; superior in her character, her appearance and her nobility…As much as you, a glorious maiden, are seen to outshine the ranks of girls, so you, Sigibert, surpass the husbands

Venantius Fortunatus, “De Sigiberctho rege et Brunichilde regina,” lines 9-130, cited in Thomas. E J (2012) ‘The ‘second Jezabel’: Representations of the sixth-century Queen Brunhild’ PhD thesis for the School of Humanities, University of Glasgow.

Guiding Questions:

Fertile in its chaste bed…gets fresh offspring…Christ then joined Queen Brunhild to Himself in love, for her merits, when He gave her to you...before she had pleased only man, however, but now behold she pleases God. … Beautiful, modest, decorous, intelligent, dutiful, pleasing and good; superior in her character, her appearance and her nobility…As much as you, a glorious maiden, are seen to outshine the ranks of girls, so you, Sigibert, surpass the husbands

Venantius Fortunatus, “De Sigiberctho rege et Brunichilde regina,” lines 9-130, cited in Thomas. E J (2012) ‘The ‘second Jezabel’: Representations of the sixth-century Queen Brunhild’ PhD thesis for the School of Humanities, University of Glasgow.

Guiding Questions:

- In this text, underline keywords that describe why and how Brunhilde became queen?

- Is this a reliable and trustworthy text?

Remedial Herstory Editors. "11. 300-900 THE AGE OF QUEENS AND EMPRESSES." The Remedial Herstory Project. June 7, 2023. www.remedialherstory.com.

AUTHOR: |

Kelsie Brook Eckert

|

Primary Reviewer: |

Dr. Jonathan Couser

|

Consulting Team |

Editors |

|

Kelsie Brook Eckert, Project Director

Coordinator of Social Studies Education at Plymouth State University Dr. Nancy Locklin-Sofer, Consultant Professor of History at Maryville College. Chloe Gardner, Consultant PhD Candidate in Religious Studies at Edinburgh University Dr. Whitney Howarth, Consultant Former Professor of History at Plymouth State University Jacqui Nelson, Consultant Teaching Lecturer of Military History at Plymouth State University Maria Concepcion Marquez Sandoval PhD Candidate in History at Arizona University |

Chris Canfield

Humanities Teacher, Moultonborough Academy ReviewersAncient:

Dr. Kristin Heineman Professor of History at Colorado State University Dr. Bonnie Rock-McCutcheon Professor of History at Wilson College Sarah Stone PhD Candidate in Religious Studies at Edinburgh University Medieval: Dr. Katherine Koh Professor of History at La Sierra University Dr. Jonathan Couser Professor of History at Plymouth State University Dr. Shahla Haeri Professor of History at Boston University Lauren Cole PhD Candidate in History at Northwestern University Modern: Dr. Barbara Tischler Supervisor for Hunter College Dr. Pamela Scully Professor of Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies and African Studies at Emory University |

Bibli0graphy

Cartwright, Mark. "Empress Theodora." World History Encyclopedia. Last modified April 03, 2018. https://www.worldhistory.org/Empress_Theodora/.

Cartwright, Mark. "Queen Himiko." World History Encyclopedia. Last modified May 01, 2017. https://www.worldhistory.org/Queen_Himiko/.

Lewis, Jone Johnson. "Empress Suiko of Japan." ThoughtCo. https://www.thoughtco.com/empress-suiko-of-japan-biography-3528831 (accessed June 6, 2022).

Miles, Rosalind. The Women’s History of the World. London, UK: HarperCollins Publishers, 1988.

Pitchon, Allie, “Female Warriors Who Led African Empires and Armies,” HISTORY (January 3, 2024)

https://www.history.com/news/african-female-warriors.

Strayer, R. and Nelson, E., Ways Of The World. 3rd ed. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2016.

Cartwright, Mark. "Queen Himiko." World History Encyclopedia. Last modified May 01, 2017. https://www.worldhistory.org/Queen_Himiko/.

Lewis, Jone Johnson. "Empress Suiko of Japan." ThoughtCo. https://www.thoughtco.com/empress-suiko-of-japan-biography-3528831 (accessed June 6, 2022).

Miles, Rosalind. The Women’s History of the World. London, UK: HarperCollins Publishers, 1988.

Pitchon, Allie, “Female Warriors Who Led African Empires and Armies,” HISTORY (January 3, 2024)

https://www.history.com/news/african-female-warriors.

Strayer, R. and Nelson, E., Ways Of The World. 3rd ed. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2016.