12. 700-1200 The Golden Age of Islam

|

Women are prominent in the history of Islam, from Muhammad's wives to his transformative policies related to women to the way their lives became increasingly restricted as the empire grew. Muslim women rose to leadership positions in the Golden Age and were essential to early Islamic religious thought.

|

As in most monotheistic religions, women were the first converts and were close to the prophet whose teachings are central to the faith. There is no Islam without women. From the very beginning, women were placed at the heart of Islam, as the Prophet Muhammad’s wife, Khadija, an older divorcee and financially independent business woman, became “the first Muslim.” She was the first to believe and follow her husband’s revelations. Their daughter, Fatimah bint Muhammad, commonly known as Fatimah al-Zahra, was also especially revered even by the Prophet himself. He is said to have regarded her as the most outstanding woman of all time, and she is now regarded as the paradigmatic example of Muslim womanhood for her compassion, generosity, and enduring suffering.

Global Context

As the old empire of Rome fractured and China entered into a Golden Age, the Middle of Eurasia saw a rebirth. In 622, a man called Muhammad claiming to be a prophet was forced to flee Mecca for Medina, a city on the Arabian peninsula. He traveled with his followers and was pursued by assassins, along with an army that was trying to wipe out his community, the first Muslims.

Muhammad had been trying to unite the various Meccan clans under monotheism. He is said to have received revelations from the one, almighty God (Allah). He would become the main prophet of Islam. His wife, Khadija was an older, wealthy business woman, who financially supported most of his efforts. Like Sarah in Judaism and Mary in Christianity, Khadija was the first Muslim, or believer in Islam.

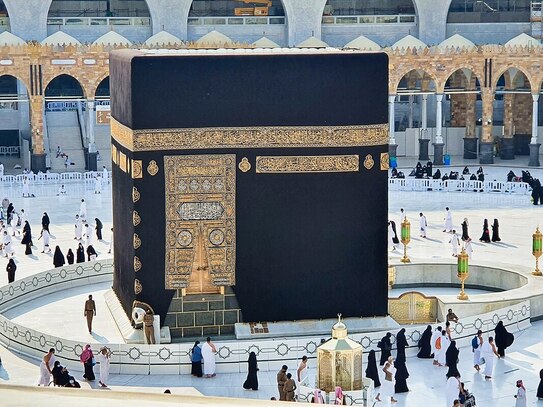

After Muhammad began to share his revelations, he faced opposition and violence from the tribe that held commercial and political authority in the region, the Quraysh. The Quraysh, like most tribes in the region, were pagans who worshiped many gods. They feared the monotheistic message would hurt the trade that brought thousands of merchants and pilgrims to the shrine in Mecca (the Ka’ba) each year. They feared losing power and wealth.

Global Context

As the old empire of Rome fractured and China entered into a Golden Age, the Middle of Eurasia saw a rebirth. In 622, a man called Muhammad claiming to be a prophet was forced to flee Mecca for Medina, a city on the Arabian peninsula. He traveled with his followers and was pursued by assassins, along with an army that was trying to wipe out his community, the first Muslims.

Muhammad had been trying to unite the various Meccan clans under monotheism. He is said to have received revelations from the one, almighty God (Allah). He would become the main prophet of Islam. His wife, Khadija was an older, wealthy business woman, who financially supported most of his efforts. Like Sarah in Judaism and Mary in Christianity, Khadija was the first Muslim, or believer in Islam.

After Muhammad began to share his revelations, he faced opposition and violence from the tribe that held commercial and political authority in the region, the Quraysh. The Quraysh, like most tribes in the region, were pagans who worshiped many gods. They feared the monotheistic message would hurt the trade that brought thousands of merchants and pilgrims to the shrine in Mecca (the Ka’ba) each year. They feared losing power and wealth.

Cesarian Section performed in the later Islamic Empire, Wikimedia Commons

Cesarian Section performed in the later Islamic Empire, Wikimedia Commons

Early Gains for Women

Women were drawn to Muhammad and his message, both spiritually and practically. A core tenet of Muhammad’s revelations was an emphasis on Charity. Men were encouraged to take in via marriage orphans, widows, and enslaved people as a type of social welfare for the society. In a desert culture where women without physical protection were vulnerable, taking multiple wives, it was argued, protected them from rape, violent assault, or death by warring tribesmen. Muhammed asked all Muslims to protect women and children as part of their duty to Allah. Men had a legal and religious obligation to care for their wives materially, sexually, and emotionally. He allowed women to enter into contracts by law, to seek custody of children after divorce, and frowned upon child marriage.

Muhammad himself had many wives, including some child brides. including child brides. Muhammad’s third and “most beloved wife,” Aisha, was one of the most important figures in early Islam. She was the daughter of his longtime ally and friend, Abu Bakr. She was a child, probably nine, when she married him. Following his death, she became one of the most prominent contributors to the spread of his message, narrating 2,210 hadiths, not just on matters related to Muhammad's private life, but also on topics such as inheritance, pilgrimage, and the end times.

Perhaps the greatest achievement of early Islam with regard to women was its strict prohibition of female infanticide, the killing of girl babies, which was commonplace in the Middle East, North Africa, and India. A preference for male babies was evidence of deep seeded misogyny in a society reliant on manual laborers and the belief that young girls are a burden.

Under Islam, women were given control over their own property, especially their dowries and inheritance, but their inheritance was half the rate of men. Islam enforced consent, and marriage by kidnapping was prohibited. Divorce was possible but difficult for women to attain. Nevertheless, divorce it was more possible than in any faith up to that time..

Female Contemporaries

Muslim women found incredible freedom and honor in aligning with the Prophet Muhammad. Women who followed him garnered protection.

Nusaybah bint Ka’ab is famous for defending Muhammad in the Battle of Uhud, one of the early conflicts as Muhammad defended against the pagans from Mecca. Nusaybah was there to help and nurse the soldiers. At some point in the battle, the archers on the hill believed victory was in sight and abandoned their position, leaving Muhammed and some of his followers vulnerable. Nusaybah grabbed weapons and stood between the Meccans and Muhammad. Muhammad described her in battle, “Wherever I turned, left or right, on the Day of Uhud — I saw her fighting for me.”

She was wounded in twelve or more places and fainted from a major blow to the shoulder. When she recovered, her first words were to inquire about the health of Muhammad. She and dozens of other women participated in subsequent battles, and in some cases they shared in the spoils of war.

But as the Islamic civilization flourished and expanded, elite Muslim women saw their rights restricted socially and economically

Women were drawn to Muhammad and his message, both spiritually and practically. A core tenet of Muhammad’s revelations was an emphasis on Charity. Men were encouraged to take in via marriage orphans, widows, and enslaved people as a type of social welfare for the society. In a desert culture where women without physical protection were vulnerable, taking multiple wives, it was argued, protected them from rape, violent assault, or death by warring tribesmen. Muhammed asked all Muslims to protect women and children as part of their duty to Allah. Men had a legal and religious obligation to care for their wives materially, sexually, and emotionally. He allowed women to enter into contracts by law, to seek custody of children after divorce, and frowned upon child marriage.

Muhammad himself had many wives, including some child brides. including child brides. Muhammad’s third and “most beloved wife,” Aisha, was one of the most important figures in early Islam. She was the daughter of his longtime ally and friend, Abu Bakr. She was a child, probably nine, when she married him. Following his death, she became one of the most prominent contributors to the spread of his message, narrating 2,210 hadiths, not just on matters related to Muhammad's private life, but also on topics such as inheritance, pilgrimage, and the end times.

Perhaps the greatest achievement of early Islam with regard to women was its strict prohibition of female infanticide, the killing of girl babies, which was commonplace in the Middle East, North Africa, and India. A preference for male babies was evidence of deep seeded misogyny in a society reliant on manual laborers and the belief that young girls are a burden.

Under Islam, women were given control over their own property, especially their dowries and inheritance, but their inheritance was half the rate of men. Islam enforced consent, and marriage by kidnapping was prohibited. Divorce was possible but difficult for women to attain. Nevertheless, divorce it was more possible than in any faith up to that time..

Female Contemporaries

Muslim women found incredible freedom and honor in aligning with the Prophet Muhammad. Women who followed him garnered protection.

Nusaybah bint Ka’ab is famous for defending Muhammad in the Battle of Uhud, one of the early conflicts as Muhammad defended against the pagans from Mecca. Nusaybah was there to help and nurse the soldiers. At some point in the battle, the archers on the hill believed victory was in sight and abandoned their position, leaving Muhammed and some of his followers vulnerable. Nusaybah grabbed weapons and stood between the Meccans and Muhammad. Muhammad described her in battle, “Wherever I turned, left or right, on the Day of Uhud — I saw her fighting for me.”

She was wounded in twelve or more places and fainted from a major blow to the shoulder. When she recovered, her first words were to inquire about the health of Muhammad. She and dozens of other women participated in subsequent battles, and in some cases they shared in the spoils of war.

But as the Islamic civilization flourished and expanded, elite Muslim women saw their rights restricted socially and economically

Aisha in the Battle of the Camel, Wikimedia Commons

Aisha in the Battle of the Camel, Wikimedia Commons

Death of Muhammad

When Muhammad died, Muslims were divided on the proper path for succession. Most favored Abu Bakr, Aisha’s father, while others preferred Khadija’s daughter Fatima’s husband, Ali. Abu Bakr succeeded Muhammad and began a war of conquest that continued after his death. Abu Bakr died of illness and the second Caliph, or leader, Umar continued the wars for expansion.

As the empire grew, women’s roles became more restricted. Umar told women that they must pray at home and veiling and seclusion became standard practice in Muslim society. This removed women from public life. Men and women prayed separately, and women were not seen by unrelated men. A later caliph created social infrastructure in order to make women’s segregation more practical by building a bridge across the Euphrates river only for women.

Being secluded became synonymous with being chaste, a symbol of one’s wealth and class. Poor Muslim women throughout the empire who lacked servants and slaves had to go to the market or to work and were not as secluded as wealthy women..

When the third caliph died, Ali again asserted his position as a rightful Caliph, but many still opposed him, including Aisha and several of Muhammad’s other widows.

Aisha is perhaps most famous for leading troops into battle to oppose Muhammad’s son-in-law for control of the Muslim Empire. Muhammad’s other wives notably did not join her, believing a widow’s place was in seclusion. Aisha fought in the “Battle of the Camel” to protect Islam and the honor of the chosen successor, Uthman, who was assassinated. This massive battle cost thousands of Muslims their lives and represented an emerging rift between the Sunni and Shia Muslims. The battle ended only after Aisha’s camel was hamstrung and killed and she was captured. She was spared by the mercy of Ali and marched, humiliated, to her home. Ali went on to become the fourth Caliph of Islam.

But Aisha retreated to Medina, opened a school, and became a teacher. Privately, Aisha continued influencing those intertwined in the Islamic political sphere. Within the Islamic community, she was known as an intelligent woman who debated law with male companions. For the last years of her life, Aisha spent much of her time telling the stories of Muhammad.

When Muhammad died, Muslims were divided on the proper path for succession. Most favored Abu Bakr, Aisha’s father, while others preferred Khadija’s daughter Fatima’s husband, Ali. Abu Bakr succeeded Muhammad and began a war of conquest that continued after his death. Abu Bakr died of illness and the second Caliph, or leader, Umar continued the wars for expansion.

As the empire grew, women’s roles became more restricted. Umar told women that they must pray at home and veiling and seclusion became standard practice in Muslim society. This removed women from public life. Men and women prayed separately, and women were not seen by unrelated men. A later caliph created social infrastructure in order to make women’s segregation more practical by building a bridge across the Euphrates river only for women.

Being secluded became synonymous with being chaste, a symbol of one’s wealth and class. Poor Muslim women throughout the empire who lacked servants and slaves had to go to the market or to work and were not as secluded as wealthy women..

When the third caliph died, Ali again asserted his position as a rightful Caliph, but many still opposed him, including Aisha and several of Muhammad’s other widows.

Aisha is perhaps most famous for leading troops into battle to oppose Muhammad’s son-in-law for control of the Muslim Empire. Muhammad’s other wives notably did not join her, believing a widow’s place was in seclusion. Aisha fought in the “Battle of the Camel” to protect Islam and the honor of the chosen successor, Uthman, who was assassinated. This massive battle cost thousands of Muslims their lives and represented an emerging rift between the Sunni and Shia Muslims. The battle ended only after Aisha’s camel was hamstrung and killed and she was captured. She was spared by the mercy of Ali and marched, humiliated, to her home. Ali went on to become the fourth Caliph of Islam.

But Aisha retreated to Medina, opened a school, and became a teacher. Privately, Aisha continued influencing those intertwined in the Islamic political sphere. Within the Islamic community, she was known as an intelligent woman who debated law with male companions. For the last years of her life, Aisha spent much of her time telling the stories of Muhammad.

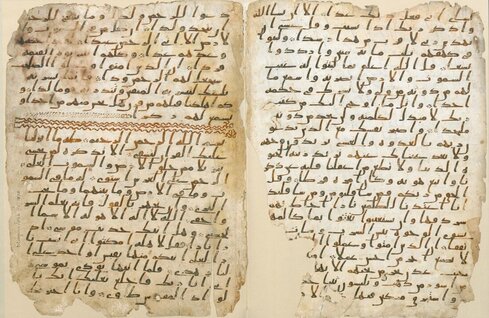

Quran, Wikimedia Commons

Quran, Wikimedia Commons

The Quran

In the years after Muhammad’s passing, his revelations were recorded by his followers in the form of a single book, the Quran. The Quran is explicit in its assertion that men and women are spiritually equal. The text uses gender-inclusive language such as, “those who surrender themselves to Allah and accept the true Faith; who are devout, sincere, patient, humble, charitable, and chaste; who fast in a never mind full of Allah— on these, both men and women, all I will bestow forgiveness and rich reward.”

But socially, Islam could not alone transcend the cultural norms in the growing Islamic empire. The Quran also limited women's lived experience, especially within marriage. One passage made women’s subordination explicit:, “Men have authority over women because Allah has made the one superior to the other, and because they spend their wealth to maintain them. Good women are obedient.”

The Quran banned women from taking more than one husband while permitting men to have numerous wives because women were not providers. This reinforced a patriarchal lineage and ownership of wives and children. Men could only have up to four wives and had to treat each of them equally. Men were allowed to have sex with enslaved women, but any children those women birthed were free.

Despite the numerous female contributors to the hadith, the denigration of the female sex was evident in the lack of schooling and woman-produced writings following the early period. While the Quran said heaven was at a mother’s feet, other passages were interpreted as permitting husbands to discipline their wives This included prioritizing males’ legal testimony over a woman’s, and proscribing violent punishments for adultery. For example, “Women are like fields for you; so seed them as you intend, but… remember, you have to face Allah in the end.” (The Quran THE COW, 2:223)

While the physical control of women may have been common in many Middle Eastern cultures in the 600s (in Christian and Jewish societies as well) passages like this are absent in other sacred texts from those traditions.

Later Muslims also recorded the Hadith, a collection of traditions and daily practices attributed to Muhammad. Some Hadiths are respected more than others, based on who recorded them and how far back one could trace the Hadith. Over time, Hadith pronouncements became increasingly hostile to women, almost contrary to the history known about Muhammad’s treatment of women.

In the years after Muhammad’s passing, his revelations were recorded by his followers in the form of a single book, the Quran. The Quran is explicit in its assertion that men and women are spiritually equal. The text uses gender-inclusive language such as, “those who surrender themselves to Allah and accept the true Faith; who are devout, sincere, patient, humble, charitable, and chaste; who fast in a never mind full of Allah— on these, both men and women, all I will bestow forgiveness and rich reward.”

But socially, Islam could not alone transcend the cultural norms in the growing Islamic empire. The Quran also limited women's lived experience, especially within marriage. One passage made women’s subordination explicit:, “Men have authority over women because Allah has made the one superior to the other, and because they spend their wealth to maintain them. Good women are obedient.”

The Quran banned women from taking more than one husband while permitting men to have numerous wives because women were not providers. This reinforced a patriarchal lineage and ownership of wives and children. Men could only have up to four wives and had to treat each of them equally. Men were allowed to have sex with enslaved women, but any children those women birthed were free.

Despite the numerous female contributors to the hadith, the denigration of the female sex was evident in the lack of schooling and woman-produced writings following the early period. While the Quran said heaven was at a mother’s feet, other passages were interpreted as permitting husbands to discipline their wives This included prioritizing males’ legal testimony over a woman’s, and proscribing violent punishments for adultery. For example, “Women are like fields for you; so seed them as you intend, but… remember, you have to face Allah in the end.” (The Quran THE COW, 2:223)

While the physical control of women may have been common in many Middle Eastern cultures in the 600s (in Christian and Jewish societies as well) passages like this are absent in other sacred texts from those traditions.

Later Muslims also recorded the Hadith, a collection of traditions and daily practices attributed to Muhammad. Some Hadiths are respected more than others, based on who recorded them and how far back one could trace the Hadith. Over time, Hadith pronouncements became increasingly hostile to women, almost contrary to the history known about Muhammad’s treatment of women.

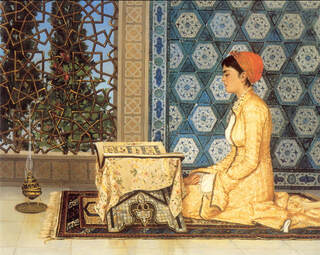

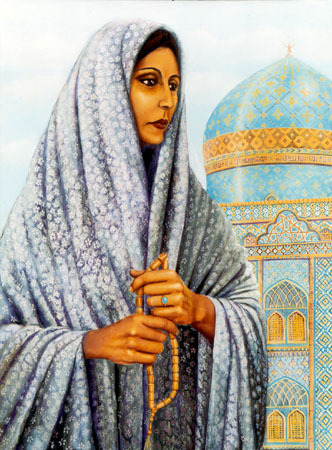

Muslim Women Scholar, Wikimedia Commons

Muslim Women Scholar, Wikimedia Commons

Female Scholars

Aisha was not the only female scholar to contribute to Islamic texts and literature. One analyst found that, “most of the important compilers of hadith from the earliest period received many of them from women teachers, as the immediate authorities. Ibn Hajar studied from 53 women; As-Sakhawi had ijazas from 68 women and As-Suyuti studied from 33 women, a quarter of his shuyukh.” Historians count more than 8,000 female Islamic scholars of note.

Women who memorized the teachings of Muhammad were often consulted by legal scholars, wrote petitions, entered opinions in the public sphere, and were mentioned by biographers, dictionaries, and debates of the day. To establish authenticity and authority, scholars kept track of lineages, noting which scholars mentored which schools and recorded “chains of transmission.” Oral histories that retold these chains served to strengthen legitimacy.

Sayiida Nafisa who lived a century after Muhammad, was famous for her devotion and asceticism. Living in near-seclusion, with almost no material goods, she and other Musim women scholars memorized thousands of Hadiths. Nafisa gave lectures at mosques, blessings to weary travelers on Hajj, and performed miracles. Nafisa helped prisoners and the hungry. She was revered even after her death as a holy woman, and pilgrims visited her shrine. She is one of the patron saints of the city of Cairo in Egypt.

Rabi’a was a Sufi Muslim poet whose ideas demonstrated persistent feminist inklings within the increasingly restrictive faith. One poem attributed to her demonstrated her pure devotion to Islam. She wrote:

O my Lord, if I worship you

from fear of hell, burn me in hell.

If I worship you from hope of Paradise,

bar me from its gates.

But if I worship you for yourself alone,

grant me then the beauty of your Face.

Still, women scholars and teachers were less common in this period as most women were illiterate. A Muslim woman was more likely to be educated in places like Al Andalusa (Muslim Spain) than her Christian counterparts, but that was only among the elites.

One particularly hostile and frequently quoted Hadith only weakly attributed to Muhammad was: “Never will succeed such a nation as makes a woman their ruler.” Aisha’s defeat only helped solidify these ideas. Yet women continued to rule Islamic kingdoms as consorts through the Golden Age of Islam.

Aisha was not the only female scholar to contribute to Islamic texts and literature. One analyst found that, “most of the important compilers of hadith from the earliest period received many of them from women teachers, as the immediate authorities. Ibn Hajar studied from 53 women; As-Sakhawi had ijazas from 68 women and As-Suyuti studied from 33 women, a quarter of his shuyukh.” Historians count more than 8,000 female Islamic scholars of note.

Women who memorized the teachings of Muhammad were often consulted by legal scholars, wrote petitions, entered opinions in the public sphere, and were mentioned by biographers, dictionaries, and debates of the day. To establish authenticity and authority, scholars kept track of lineages, noting which scholars mentored which schools and recorded “chains of transmission.” Oral histories that retold these chains served to strengthen legitimacy.

Sayiida Nafisa who lived a century after Muhammad, was famous for her devotion and asceticism. Living in near-seclusion, with almost no material goods, she and other Musim women scholars memorized thousands of Hadiths. Nafisa gave lectures at mosques, blessings to weary travelers on Hajj, and performed miracles. Nafisa helped prisoners and the hungry. She was revered even after her death as a holy woman, and pilgrims visited her shrine. She is one of the patron saints of the city of Cairo in Egypt.

Rabi’a was a Sufi Muslim poet whose ideas demonstrated persistent feminist inklings within the increasingly restrictive faith. One poem attributed to her demonstrated her pure devotion to Islam. She wrote:

O my Lord, if I worship you

from fear of hell, burn me in hell.

If I worship you from hope of Paradise,

bar me from its gates.

But if I worship you for yourself alone,

grant me then the beauty of your Face.

Still, women scholars and teachers were less common in this period as most women were illiterate. A Muslim woman was more likely to be educated in places like Al Andalusa (Muslim Spain) than her Christian counterparts, but that was only among the elites.

One particularly hostile and frequently quoted Hadith only weakly attributed to Muhammad was: “Never will succeed such a nation as makes a woman their ruler.” Aisha’s defeat only helped solidify these ideas. Yet women continued to rule Islamic kingdoms as consorts through the Golden Age of Islam.

Queen Arwa, Public Domain

Queen Arwa, Public Domain

Umayyad and Abbasid Empires

During the subsequent Umayyad and Abbasid Empires, women served as teachers, preachers, philanthropists, patrons, scholars and jurists. Sufi women especially were often wealthy property holders who built houses of worship, schools, feeding houses, and shrines to Muslim saints in order to care for the poor and use their influence to better society.

Women were involved in assassination plots, arranged marriages to consolidate wealth and power, collaborated with investors and patrons to support the arts, build schools, houses of worship, shrines, led armies, flouted dishonest viziers, pirates and social climbers and supervised sacred festivals and spectacles of devotion to gain influence. Showing piety and highlighting devotion via service and networks of the faithful guaranteed many women special status in the landscape of power in this period.

The Abbasid Empire existed in a period of great land expansion for the Caliphate. The capital city of Baghdad grew and embraced immigrants from around the Muslim world, including Christians, Jews, Hindus and Zoroastrians. Most women belonged to families of farmers and traders. In many areas, common women were likely subject to enslavement during territorial expansion.

Al-Khayzuran was the wife of al-Mahdi the Caliph. Like other Queens and Empresses of the period, Al-Khayzuran was enslaved to a wealthy master who trained her in the arts, science, mathematics, theology, and Islamic law. DShe was more educated than most women in the world at the time and more than most men in her society. She was sold as a concubine to the future Caliph. Harems in Muslim culture differed greatly from those found in East Asia. Only the elite men could afford them and their wives and concubines were active in politics and managed their own business. In this environment, Al-Lhayzuran’s wit and aptitude for leadership was apparent, and she found his favor. She convinced him to free her and make her his legitimate wife. When he ascended to leadership she maintained the lady-like seclusion expected of an elite woman. At court, she sat behind a screen and listened in on matters of state. She often quarreled with the Caliph and did not hesitate to confront him on important issues.

She had two sons who succeeded their father as Caliphs. One son did not like being controlled by his mother and at one point angrily rebutted, “Don’t you have a spindle to keep you busy, a Quran for praying, a residence in which to hide from those besieging you? Watch yourself, and woe to you if you open your mouth in favor of anyone at all.”

Failure to submit to her rule led to Al-Khayzuran having her son murdered. Her second son assumed the role of Caliph and happily shared power with his mother. His rule was arguably the most powerful of the Abbasids, and his mother is considered by most historians to be the power behind the throne. Although Caliphs were expected to be stoic, he wept openly when his mother died.

The Abbasids declined and were replaced by the Fatimid Empire that claimed lineage from Muhammad’s daughter. Here more powerful women thrived. Sitt al-Mulk, whose mother was a concubine.She was favored by her father, had an army at her disposal, and donated lavishly to charity. She never married so that her brother’s line would be uncontested. But after she arranged for her brother’s disappearance or death, she served as regent for his young son. She was a firm ruler who stayed in power until her death in 1023.

Al-Khayzuran and Sitt al-Mulk’s involvement in assassination plots is a very familiar trope of female leaders. Why are female rulers portrayed as conniving assassins of their rivals? Were they as evil as portrayed? Or was it a pattern of narrative that later chroniclers resorted to in order to frame power in the hands of women as something unearned or unacceptable?

Not all queens were portrayed that way. Queen Arwa was an orphan adopted by the king and queen of Yemen. She married the crown prince, but he became paralyzed, and Arwa served as de facto ruler. She focused her attention on public welfare, building schools, roads, and mosques. She affectionately earned the name “Little Queen of Sheba” from her people.

During the subsequent Umayyad and Abbasid Empires, women served as teachers, preachers, philanthropists, patrons, scholars and jurists. Sufi women especially were often wealthy property holders who built houses of worship, schools, feeding houses, and shrines to Muslim saints in order to care for the poor and use their influence to better society.

Women were involved in assassination plots, arranged marriages to consolidate wealth and power, collaborated with investors and patrons to support the arts, build schools, houses of worship, shrines, led armies, flouted dishonest viziers, pirates and social climbers and supervised sacred festivals and spectacles of devotion to gain influence. Showing piety and highlighting devotion via service and networks of the faithful guaranteed many women special status in the landscape of power in this period.

The Abbasid Empire existed in a period of great land expansion for the Caliphate. The capital city of Baghdad grew and embraced immigrants from around the Muslim world, including Christians, Jews, Hindus and Zoroastrians. Most women belonged to families of farmers and traders. In many areas, common women were likely subject to enslavement during territorial expansion.

Al-Khayzuran was the wife of al-Mahdi the Caliph. Like other Queens and Empresses of the period, Al-Khayzuran was enslaved to a wealthy master who trained her in the arts, science, mathematics, theology, and Islamic law. DShe was more educated than most women in the world at the time and more than most men in her society. She was sold as a concubine to the future Caliph. Harems in Muslim culture differed greatly from those found in East Asia. Only the elite men could afford them and their wives and concubines were active in politics and managed their own business. In this environment, Al-Lhayzuran’s wit and aptitude for leadership was apparent, and she found his favor. She convinced him to free her and make her his legitimate wife. When he ascended to leadership she maintained the lady-like seclusion expected of an elite woman. At court, she sat behind a screen and listened in on matters of state. She often quarreled with the Caliph and did not hesitate to confront him on important issues.

She had two sons who succeeded their father as Caliphs. One son did not like being controlled by his mother and at one point angrily rebutted, “Don’t you have a spindle to keep you busy, a Quran for praying, a residence in which to hide from those besieging you? Watch yourself, and woe to you if you open your mouth in favor of anyone at all.”

Failure to submit to her rule led to Al-Khayzuran having her son murdered. Her second son assumed the role of Caliph and happily shared power with his mother. His rule was arguably the most powerful of the Abbasids, and his mother is considered by most historians to be the power behind the throne. Although Caliphs were expected to be stoic, he wept openly when his mother died.

The Abbasids declined and were replaced by the Fatimid Empire that claimed lineage from Muhammad’s daughter. Here more powerful women thrived. Sitt al-Mulk, whose mother was a concubine.She was favored by her father, had an army at her disposal, and donated lavishly to charity. She never married so that her brother’s line would be uncontested. But after she arranged for her brother’s disappearance or death, she served as regent for his young son. She was a firm ruler who stayed in power until her death in 1023.

Al-Khayzuran and Sitt al-Mulk’s involvement in assassination plots is a very familiar trope of female leaders. Why are female rulers portrayed as conniving assassins of their rivals? Were they as evil as portrayed? Or was it a pattern of narrative that later chroniclers resorted to in order to frame power in the hands of women as something unearned or unacceptable?

Not all queens were portrayed that way. Queen Arwa was an orphan adopted by the king and queen of Yemen. She married the crown prince, but he became paralyzed, and Arwa served as de facto ruler. She focused her attention on public welfare, building schools, roads, and mosques. She affectionately earned the name “Little Queen of Sheba” from her people.

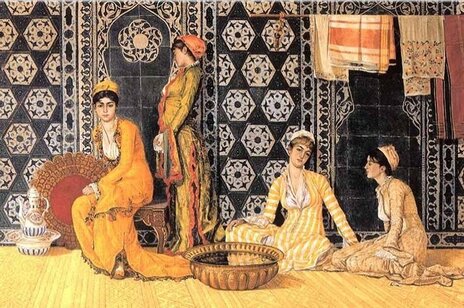

Muslim Women, Public Domain

Muslim Women, Public Domain

Conclusion

By 900, Islam had reached most of the Middle East and northern Africa. By 1300, it had expanded to include most of the Sahara and East coast of Africa, and northern India. By1500, followers could be found in Europe, modern day Russia, and further into India. When the Mongols sacked Baghdad, the capital of the Arab Empire, the strength of Islam as a faith was evident because the religion and Arabic, in which most texts were recorded, continued to expand even though the empire had fractured.

The west African empires of Ghana, Mali, Songhai, Hausa states, and Bornu embraced Islam and boasted hundreds of Quranic schools and universities. But wherever Islam spread, it melded with the local culture. When the world traveler Ibn Battuta came to Mali, he was appalled that practicing Muslims allowed their women to appear in public almost naked and mingle freely with men outside their families. In reply to his remark, one Mali man told him “they are not like the women of your country.”

As the Islamic Empire spread, cultural diffusion and integration took place. Practices in certain localities such as “honor killing“ of women by their male relatives when they were dishonored were practiced in the name of Islam even though Islam never called for it. Elsewhere, clitorectomy became common. This was the practice of cutting and sewing a woman’s vagina to make it painful to have sex to enforce chastity. This practice was not prescribed in the Quran or Islamic law, but it nevertheless existed where Islam existed.

The early years of Islam garnered women many freedoms and protections that had not existed in Arab clans, but those were challenged as the small faith grew into a series of massive empires. Like most places, elite women were policed more than lower class women, and all women found themselves subordinate to men.

By the end of this era, so much remained in question. Could Islam maintain its thriving culture? Would women continue to maintain their respected positions as scholars? Or would they be sidelined by patriarchal institutions?

By 900, Islam had reached most of the Middle East and northern Africa. By 1300, it had expanded to include most of the Sahara and East coast of Africa, and northern India. By1500, followers could be found in Europe, modern day Russia, and further into India. When the Mongols sacked Baghdad, the capital of the Arab Empire, the strength of Islam as a faith was evident because the religion and Arabic, in which most texts were recorded, continued to expand even though the empire had fractured.

The west African empires of Ghana, Mali, Songhai, Hausa states, and Bornu embraced Islam and boasted hundreds of Quranic schools and universities. But wherever Islam spread, it melded with the local culture. When the world traveler Ibn Battuta came to Mali, he was appalled that practicing Muslims allowed their women to appear in public almost naked and mingle freely with men outside their families. In reply to his remark, one Mali man told him “they are not like the women of your country.”

As the Islamic Empire spread, cultural diffusion and integration took place. Practices in certain localities such as “honor killing“ of women by their male relatives when they were dishonored were practiced in the name of Islam even though Islam never called for it. Elsewhere, clitorectomy became common. This was the practice of cutting and sewing a woman’s vagina to make it painful to have sex to enforce chastity. This practice was not prescribed in the Quran or Islamic law, but it nevertheless existed where Islam existed.

The early years of Islam garnered women many freedoms and protections that had not existed in Arab clans, but those were challenged as the small faith grew into a series of massive empires. Like most places, elite women were policed more than lower class women, and all women found themselves subordinate to men.

By the end of this era, so much remained in question. Could Islam maintain its thriving culture? Would women continue to maintain their respected positions as scholars? Or would they be sidelined by patriarchal institutions?

Draw your own conclusions

|

Learn how to teach with inquiry.

Many of these lesson plans were sponsored in part by the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources Eastern Region Program, coordinated by Waynesburg University, the History and Social Studies Education Faculty at Plymouth State University, and the Patrons of the Remedial Herstory Project. |

|

Was early Islam misogynistic?

In the west, Islamophobia contributes to a sense that Islam is inherently misogynistic. The veiling of Muslim women has led to heated, sometimes violent debate about the status of women in predominantly Islamic countries. Yet, is this accurate? This inquiry explores passages in the Quran and the later Haddith to more deeply understand the impact of Muhammad's ideas, as well as prevailing Arabic culture on women in his time and shortly afterward. Coming soon! |

Lesson Plans from Other Organizations

- This website, Women in World History has primary source based lesson plans on women's history in a whole range of topics. Some are free while others have a cost.

- The Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media has produced recommendations for teaching women's history with primary sources and provided a collection of sources for world history. Check them out!

- The Stanford History Education Group has a number of lesson plans about women in World History.

Women in Islam

The Quran: On Women

The text below contains excerpts from the Quran which relate to women.

In the name of Allah, the Beneficent, the Merciful.

4.1: O people! be careful of (your duty to) your Lord, Who created you from a single being and created its mate of the same (kind) and spread from these two, many men and women; and be careful of (your duty to) Allah, by Whom you demand one of another (your rights), and (to) the ties of relationship; surely Allah ever watches over you.

4.3: And if you fear that you cannot act equitably towards orphans, then marry such women as seem good to you, two and three and four; but if you fear that you will not do justice (between them), then (marry) only one or what your right hands possess; this is more proper, that you may not deviate from the right course.

4.4: And give women their dowries as a free gift, but if they of themselves be pleased to give up to you a portion of it, then eat it with enjoyment and with wholesome result.

4.7: Men shall have a portion of what the parents and the near relatives leave, and women shall have a portion of what the parents and the near relatives leave, whether there is little or much of it; a stated portion.

4.12: And you shall have half of what your wives leave if they have no child, but if they have a child, then you shall have a fourth of what they leave after (payment of) any bequest they may have bequeathed or a debt; and they shall have the fourth of what you leave if you have no child, but if you have a child then they shall have the eighth of what you leave after (payment of) a bequest you may have bequeathed or a debt; and if a man or a woman leaves property to be inherited by neither parents nor offspring, and he (or she) has a brother or a sister, then each of them two shall have the sixth, but if they are more than that, they shall be sharers in the third after (payment of) any bequest that may have been bequeathed or a debt that does not harm (others); this is an ordinance from Allah: and Allah is Knowing, Forbearing.

4.15: And as for those who are guilty of an indecency from among your women, call to witnesses against them four (witnesses) from among you; then if they bear witness confine them to the houses until death takes them away or Allah opens some way for them.

4.23: Forbidden to you are your mothers and your daughters and your sisters and your paternal aunts and your maternal aunts and brothers' daughters and sisters' daughters and your mothers that have suckled you and your foster-sisters and mothers of your wives and your step-daughters who are in your guardianship, (born) of your wives to whom you have gone in, but if you have not gone in to them, there is no blame on you (in marrying them), and the wives of your sons who are of your own loins and that you should have two sisters together, except what has already passed; surely Allah is Forgiving, Merciful.

4.25: And whoever among you has not within his power ampleness of means to marry free believing women, then (he may marry) of those whom your right hands possess from among your believing maidens; and Allah knows best your faith: you are (sprung) the one from the other; so marry them with the permission of their masters, and give them their dowries justly, they being chaste, not fornicating, nor receiving paramours; and when they are taken in marriage, then if they are guilty of indecency, they shall suffer half the punishment which is (inflicted) upon free women. This is for him among you who fears falling into evil; and that you abstain is better for you, and Allah is Forgiving, Merciful.

4.32: And do not covet that by which Allah has made some of you excel others; men shall have the benefit of what they earn and women shall have the benefit of what they earn; and ask Allah of His grace; surely Allah knows all things.

4.34: Men are the maintainers of women because Allah has made some of them to excel others and because they spend out of their property; the good women are therefore obedient, guarding the unseen as Allah has guarded; and (as to) those on whose part you fear desertion, admonish them, and leave them alone in the sleeping-places and beat them; then if they obey you, do not seek a way against them; surely Allah is High, Great.

4.124: And whoever does good deeds whether male or female and he (or she) is a believer -- these shall enter the garden, and they shall not be dealt with a jot unjustly.

4.128: And if a woman fears ill usage or desertion on the part of her husband, there is no blame on them, if they effect a reconciliation between them, and reconciliation is better, and avarice has been made to be present in the (people's) minds; and if you do good (to others) and guard (against evil), then surely Allah is aware of what you do.

4.130: And if they separate, Allah will render them both free from want out of His ampleness, and Allah is Ample-giving, Wise.

2.222: And they ask you about menstruation. Say: It is a discomfort; therefore keep aloof from the women during the menstrual discharge and do not go near them until they have become clean; then when they have cleansed themselves, go in to them as Allah has commanded you; surely Allah loves those who turn much (to Him), and He loves those who purify themselves.

2.223: Your wives are a tilth for you, so go into your tilth when you like, and do good beforehand for yourselves, and be careful (of your duty) to Allah, and know that you will meet Him, and give good news to the believers.

2.228: And the divorced women should keep themselves in waiting for three courses; and it is not lawful for them that they should conceal what Allah has created in their wombs, if they believe in Allah and the last day; and their husbands have a better right to take them back in the meanwhile if they wish for reconciliation; and they have rights similar to those against them in a just manner, and the men are a degree above them, and Allah is Mighty, Wise.

2.233: And the mothers should suckle their children for two whole years for him who desires to make complete the time of suckling; and their maintenance and their clothing must be -- borne by the father according to usage; no soul shall have imposed upon it a duty but to the extent of its capacity; neither shall a mother be made to suffer harm on account of her child, nor a father on account of his child, and a similar duty (devolves) on the (father's) heir, but if both desire weaning by mutual consent and counsel, there is no blame on them, and if you wish to engage a wet-nurse for your children, there is no blame on you so long as you pay what you promised for according to usage; and be careful of (your duty to) Allah and know that Allah sees what you do.

2.234: And (as for) those of you who die and leave wives behind, they should keep themselves in waiting for four months and ten days; then when they have fully attained their term, there is no blame on you for what they do for themselves in a lawful manner; and Allah is aware of what you do.

2.236: There is no blame on you if you divorce women when you have not touched them or appointed for them a portion, and make provision for them, the wealthy according to his means and the straitened in circumstances according to his means, a provision according to usage; (this is) a duty on the doers of good (to others).

2.240: And those of you who die and leave wives behind, (make) a bequest in favor of their wives of maintenance for a year without turning (them) out, then if they themselves go away, there is no blame on you for what they do of lawful deeds by themselves, and Allah is Mighty, Wise.

2.241: And for the divorced women (too) provision (must be made) according to usage; (this is) a duty on those who guard (against evil).

Questions:

In the name of Allah, the Beneficent, the Merciful.

4.1: O people! be careful of (your duty to) your Lord, Who created you from a single being and created its mate of the same (kind) and spread from these two, many men and women; and be careful of (your duty to) Allah, by Whom you demand one of another (your rights), and (to) the ties of relationship; surely Allah ever watches over you.

4.3: And if you fear that you cannot act equitably towards orphans, then marry such women as seem good to you, two and three and four; but if you fear that you will not do justice (between them), then (marry) only one or what your right hands possess; this is more proper, that you may not deviate from the right course.

4.4: And give women their dowries as a free gift, but if they of themselves be pleased to give up to you a portion of it, then eat it with enjoyment and with wholesome result.

4.7: Men shall have a portion of what the parents and the near relatives leave, and women shall have a portion of what the parents and the near relatives leave, whether there is little or much of it; a stated portion.

4.12: And you shall have half of what your wives leave if they have no child, but if they have a child, then you shall have a fourth of what they leave after (payment of) any bequest they may have bequeathed or a debt; and they shall have the fourth of what you leave if you have no child, but if you have a child then they shall have the eighth of what you leave after (payment of) a bequest you may have bequeathed or a debt; and if a man or a woman leaves property to be inherited by neither parents nor offspring, and he (or she) has a brother or a sister, then each of them two shall have the sixth, but if they are more than that, they shall be sharers in the third after (payment of) any bequest that may have been bequeathed or a debt that does not harm (others); this is an ordinance from Allah: and Allah is Knowing, Forbearing.

4.15: And as for those who are guilty of an indecency from among your women, call to witnesses against them four (witnesses) from among you; then if they bear witness confine them to the houses until death takes them away or Allah opens some way for them.

4.23: Forbidden to you are your mothers and your daughters and your sisters and your paternal aunts and your maternal aunts and brothers' daughters and sisters' daughters and your mothers that have suckled you and your foster-sisters and mothers of your wives and your step-daughters who are in your guardianship, (born) of your wives to whom you have gone in, but if you have not gone in to them, there is no blame on you (in marrying them), and the wives of your sons who are of your own loins and that you should have two sisters together, except what has already passed; surely Allah is Forgiving, Merciful.

4.25: And whoever among you has not within his power ampleness of means to marry free believing women, then (he may marry) of those whom your right hands possess from among your believing maidens; and Allah knows best your faith: you are (sprung) the one from the other; so marry them with the permission of their masters, and give them their dowries justly, they being chaste, not fornicating, nor receiving paramours; and when they are taken in marriage, then if they are guilty of indecency, they shall suffer half the punishment which is (inflicted) upon free women. This is for him among you who fears falling into evil; and that you abstain is better for you, and Allah is Forgiving, Merciful.

4.32: And do not covet that by which Allah has made some of you excel others; men shall have the benefit of what they earn and women shall have the benefit of what they earn; and ask Allah of His grace; surely Allah knows all things.

4.34: Men are the maintainers of women because Allah has made some of them to excel others and because they spend out of their property; the good women are therefore obedient, guarding the unseen as Allah has guarded; and (as to) those on whose part you fear desertion, admonish them, and leave them alone in the sleeping-places and beat them; then if they obey you, do not seek a way against them; surely Allah is High, Great.

4.124: And whoever does good deeds whether male or female and he (or she) is a believer -- these shall enter the garden, and they shall not be dealt with a jot unjustly.

4.128: And if a woman fears ill usage or desertion on the part of her husband, there is no blame on them, if they effect a reconciliation between them, and reconciliation is better, and avarice has been made to be present in the (people's) minds; and if you do good (to others) and guard (against evil), then surely Allah is aware of what you do.

4.130: And if they separate, Allah will render them both free from want out of His ampleness, and Allah is Ample-giving, Wise.

2.222: And they ask you about menstruation. Say: It is a discomfort; therefore keep aloof from the women during the menstrual discharge and do not go near them until they have become clean; then when they have cleansed themselves, go in to them as Allah has commanded you; surely Allah loves those who turn much (to Him), and He loves those who purify themselves.

2.223: Your wives are a tilth for you, so go into your tilth when you like, and do good beforehand for yourselves, and be careful (of your duty) to Allah, and know that you will meet Him, and give good news to the believers.

2.228: And the divorced women should keep themselves in waiting for three courses; and it is not lawful for them that they should conceal what Allah has created in their wombs, if they believe in Allah and the last day; and their husbands have a better right to take them back in the meanwhile if they wish for reconciliation; and they have rights similar to those against them in a just manner, and the men are a degree above them, and Allah is Mighty, Wise.

2.233: And the mothers should suckle their children for two whole years for him who desires to make complete the time of suckling; and their maintenance and their clothing must be -- borne by the father according to usage; no soul shall have imposed upon it a duty but to the extent of its capacity; neither shall a mother be made to suffer harm on account of her child, nor a father on account of his child, and a similar duty (devolves) on the (father's) heir, but if both desire weaning by mutual consent and counsel, there is no blame on them, and if you wish to engage a wet-nurse for your children, there is no blame on you so long as you pay what you promised for according to usage; and be careful of (your duty to) Allah and know that Allah sees what you do.

2.234: And (as for) those of you who die and leave wives behind, they should keep themselves in waiting for four months and ten days; then when they have fully attained their term, there is no blame on you for what they do for themselves in a lawful manner; and Allah is aware of what you do.

2.236: There is no blame on you if you divorce women when you have not touched them or appointed for them a portion, and make provision for them, the wealthy according to his means and the straitened in circumstances according to his means, a provision according to usage; (this is) a duty on the doers of good (to others).

2.240: And those of you who die and leave wives behind, (make) a bequest in favor of their wives of maintenance for a year without turning (them) out, then if they themselves go away, there is no blame on you for what they do of lawful deeds by themselves, and Allah is Mighty, Wise.

2.241: And for the divorced women (too) provision (must be made) according to usage; (this is) a duty on those who guard (against evil).

Questions:

- What parts of this text stood out the most to you?

- What expectations are made of women in this text? Are there expectations for how a man will treat a woman?

- Are there any rights or responsibilities directly attributed to women?

Kitāb al-Silah of Ibn Bashkuwal: 27 Prominent Medieval Andalusi Women

The following biographies of medieval Andalusi women are drawn from the Kitāb al-Ṣilah of Ibn Bashkuwal (d. 1183), the Takmilat Kitāb al-Ṣilah by Ibn al-Abbar (d. 1260), and the Kitāb Ṣilat al-Ṣila by Ibn al-Zubayr (d. 1308). They include women from various classes of society and different regions of al-Andalus who participated in scholarship and learning between the ninth and thirteenth centuries. These biographical works and accounts provide important insight into the social and intellectual history of al-Andalus and allow modern scholars to better understand the role of Andalusi women in the transmission of knowledge during the Middle Ages.

Fāṭima b. Yahya b. Yūsuf al-Maghāmī. She was the sister of the great jurist Yūsuf b. Yahya al-Maghāmī. She was amongst the most knowledgeable, most magnanimous and wisest individuals in her era. She lived in Cordoba and died there around 319 AH [931]. She was buried in the suburbs of the city and her funeral was among the greatest ever witnessed for a woman of the city.

‘Ā’isha b. Ahmad b. Muhammad b. Qādim. She was from Cordoba. The famous historian [Abū Marwān Ḥayyān ibn Khalaf] Ibn Hayyān [d. 469/1075] said about her: “There was none in the entire Iberian Peninsula in her era that could be compared with her in terms of knowledge, excellence, literary skill, poetic ability, eloquence, virtue, purity, generosity, and wisdom. She would often write panegyrics in praise of the kings of her era and would give speeches in their court. She was a very skilled calligrapher and copied many manuscripts of the Qur’an and other books. She was an avid collector of books, of which she had a very large amount, and was very concerned with the pursuit of knowledge. She was also very wealthy and died chaste, without having ever married. She died in the year 400 AH [1009].

Khadījah b. Ja’far b. Nusayr b. Tammār al-Tamīmī. She was the wife of the renowned jurist ‘Abd Allāh b. Asad and narrated al-Qa’nabi’s Muwattā’ from him. After learning it, she even transcribed a copy of that book in the year 394 AH [1003]. I heard my own shaykh Abū al-Ḥasan ibn al-Mughīth (may God have mercy upon him) mention this. He also mentioned that this book was actually in his possession, and I later saw it myself.

Rāḍiyah. She was the slave-girl of the caliph Abd al-Rahmān III [r. 300/912–350/961] and was known as Najm. The caliph al-Ḥakam [r. 350/961–366/976] bought her freedom, after which she married a servant called Labīb. Together, Labīb and Rāḍiya made the pilgrimage to Mecca in 353 AH [964]. They both excelled in reading and writing…Abū Muhammad b. Khazraj narrated hadith from her. He said that he was in possession of several of her books and that she had died in 423 AH [1032], when she was nearly 100 years old.

Fāṭima b. Zakariyya b. ‘Abd Allāh al-Kātib al-Shiblārī. She was an eminent secretary and lived for a very long time, over 94 years, and spent most of that time engaged in writing long epistles and books. She wrote well and was quite eloquent in speech. Ibn Hayyān made mention of her and said that she died in 427 AH [1036].

Maryam b. Abī Ya’qūb al-Faysūlī al-Shalabī. She was a renowned and eminent poet and litterateur who would teach literature to women. She was meticulous in observing her faith. A poem written about her by Asbagh b. Abī Sayyid al-Ishbīli describes her as “possessing the piety and asceticism of the Blessed Virgin Mary, and having all the skill and poetic excellence of al-Khansā’.”

Khadījah b. Abī Muhammad ‘Abd Allāh b. Sa’īd al-Shantajiyālī. Along with her father, she learned Sahīh Bukhārī from the illustrious scholar Abū Dharr ‘Abd Allāh b. Ahmad al-Harawī, and other books. She also learned from several other illustrious scholars in Mecca. She travelled to al-Andalus with her father and died there, may God have mercy upon her.

Wallāda b. al-Mustakfī billāh Muhammad b. ‘Abd al-Rahman b. ‘Ubayd Allāh b. Abd al-Rahmān III. She was a great litterateur and poet, very eloquent in speech, skilled in verse, and would keep the company of other litterateurs and poets. I heard one of my shaykhs, Abū ‘Abd Allāh ibn Makkī (may God have mercy upon him), describe her excellence and knowledge. He told me: there is no one to equal her in honor. He also mentioned that she died on Wednesday 2nd of Safar 484 AH [26th March 1091], the same day that al-Fath b. Muhammad b. ‘Abbad was killed [and the same day on which the Almoravids conquered Cordoba].

Ṭawiyah b. ‘Abd al-Azīz b. Mūsa b. Ṭāhir b. Manā‘. She was known as Habībah and was the wife of Abū al-Qāsim b. Mudīr, the preacher and expert Qur’an reciter. She learned and transmitted many of the works and books of the eminent scholar Abū ‘Umar b. ‘Abd al-Barr [d. 463/1071] directly from him. She also learned and transmitted many of the works of Abū al-‘Abbās Ahmad b. ‘Umar al-Udhrī al-Dalā’ī [d. 478/1085]. She was born in 437 AH [1045] and died in 506 AH [1112]. I was told this information by her son Abū Bakr, may God bless and ennoble him.

Al-Shifā’, the slave-girl of the emir ‘Abd al-Raḥmān [II] b. al-Ḥakam [r. 206/822–238/852]. He freed and married her. She was among the most intelligent, beautiful, pious, gracious and noble women. She built the mosque that is located in the center of the western suburbs of Cordoba. She raised and cared for her husband’s son, the [future] emir Muḥammad b. ‘Abd al-Raḥmān [r. 238/852–273/886], when he was still an infant since his mother, Tahtaz, had died young. During one of his military campaigns, she fell ill so the emir ‘Abd al-Raḥmān arranged for her to be sent to al-Maniyyah located in the hills around Toledo. She died and was buried there. Her grave became a renowned place of visitation. Due to the great care and devotion of the people of that village to her grave, which they constantly renovated, the emir Muḥammad exempted them from all taxation.

Al-Bahā’ bt. ‘Abd al-Raḥmān [II] b. al-Ḥakam b. Hishām b. ‘Abd al-Raḥmān b. Mu‘āwiyah. She was the best of women and was very pious, ascetic and chaste. She wrote many manuscripts of the Qur’an which she would then donate to mosques and pious endowments. She was the very emdodiment of graciousness and kindness. According to Ibn Ḥayyān and [Aḥmad b. Muḥammad] al-Rāzī [d. 344/955], she was the founder of the al-Bahā’ mosque which was located in the Rusafah suburb of Cordoba. I read written in the Tārīkh of ‘Arīb b. Sa‘īd [d. 370/980] that she died in Rajab 305 AH [917] at the beginning of the reign of [‘Abd al-Raḥmān III] al-Nāṣir. Her funeral was attended by everyone.

Umm al-Ḥasan bt. Abī Liwā’ Sulaymān b. Asbagh b. ‘Abd Allāh b. Wānsūs b. Yarbū‘ al-Miknāsī, the client (mawla) of [Umayyad caliph] Sulaymān b. ‘Abd al-Malik [r. 96/715–99/717]. She was one of the companions and students of Baqī b. Makhlad [d. 276/889], whom she narrated hadith from and recited the book Kitāb al-Duhūr in his presence. His son, Abū al-Qāsim Aḥmad b. Baqī [d. 324/936], was present during this recital and had with him this book (to ensure that she recited it correctly). During her journey in search of knowledge she made the pilgrimage to Mecca (Ḥajj). She was a righteous, intelligent, ascetic and gracious woman. She has been mentioned in the Book of the Virtues of Baqī b. Makhlad (Kitāb Faḍā’il Baqī b. Makhlad). She was also mentioned by al-Rāzī, who said: “She made the Ḥajj and accumulated knowledge of jurisprudence and hadith, with Baqī b. Makhlad narrating some hadith from her. During her second Ḥajj journey, she died in Mecca and was buried there.” This is his account of her life, but I believe he was mistaken in asserting that Baqī narrated hadith from her; it is more attested and accurate that she was his student and, thus, narrated from him.

The emir ‘Abd Allāh b. ‘Abd al-Raḥmān [III] al-Nāṣir b. Muḥammad stated in al-Muskitah: “The pious scholar, the daughter of Abī Liwā’ would attend study sessions every Friday with Baqī b. Makhlad in the house of Abī ‘Abd al-Raḥmān. She was an exceptional scholar. ‘Abd Allāh, her father’s grandfather, was a noble and gracious individual. She also made the Ḥajj during her travels. During the Day of Strife [202/818], which happened on a Friday, he made a praiseworthy stand by allowing large numbers of people fleeing the violence to take refuge in his mosque. He then wrote to the emir al-Ḥakam [r. 180/796–206/822] to confirm their immunity [from prosecution and punishment], telling him that they had sought sanctuary within a sacred space. The emir confirmed their immunity and put their fears at ease in a subsequent letter that he wrote to them.”

Al-Rāzī said: “The Banū Wānsūs family were renowned for producing many intelligent, pious, noble, and excellent women. Six of them made the Ḥajj: Umm al-Ḥasan bt. Abī Liwā’; Kulaybah, the wife of Asbagh b. ‘Abd Allāh b. Wāsūs; Ummah al-Raḥman and Ummah al-Raḥīm, the daughters of Asbagh; Ruqayyah bt. Muḥammad b. Asbagh; and ‘Ā’ishah bt. ‘Umar b. Muḥammad b. Asbagh.”

According to Ibn Ḥayyān, Umm al-Ḥasan was a sister of the Chief Judge Mundhir b. Sa‘īd al-Kuznī al-Ballūṭī [d. 355/966], but I am not certain of her first name. She resided in the Faḥṣ al-Ballūṭ neighborhood of Cordoba and was one of the best women. She would often spend her time in worship at her mosque near her house. She would often be joined there by the elderly and other righteous women of her family. Together, they would constantly engage in the remembrance of God, study the biographies of the ascetics, and increase their knowledge of the faith. She was highly regarded and renowned in her own country.

Ruqayyah bt. Tammām b. ‘Āmir b. Aḥmad b. Ghālib b. Tammām b. ‘Alqamah, the client of ‘Abd al-Raḥmān b, Umm al-Ḥakam al-Thaqafī. She was employed in the royal palace in Cordoba as a secretary for the daughter of Emir Mundhir b. Muḥammad [r. 273/886–275/888].

Lubna, the palace secretary of the caliph al-Hakam [b. ‘Abd al-Rahmān] al-Mustanṣir billāh. She was also one of the assistants of Muzn, the palace secretary of [the caliph ‘Abd al-Raḥmān] al-Nāṣir. She excelled in writing, grammar, and poetry. Her knowledge of mathematics was also immense and she was proficient in other sciences as well. There were none in the Umayyad palace as noble as her. She died around 376 AH. [986].

Nizām, the Secretary. She resided in the caliphal palace in Cordoba during the reign of Hishām al-Mu’ayyad b. al-Ḥakam al-Mustanṣir billāh [r. 366/976–399/1009, 400/1010–403/1013]. She was very learned, eloquent and particularly skilled at writing epistles. One of the official documents that she authored on behalf of al-Muẓaffar ‘Abd al-Malik b. al-Manṣūr b. Muḥammad Abī ‘Āmir [r. 392/1002–399/1008] was the elegy for his father [al-Manṣūr] in which he was also confirmed as holding the offices which his father had held. This was in Shawwāl 392 [August 1002]. She was mentioned by Ibn Ḥayyān in his Tārīkh al-Kabīr and it is from that work that I have taken her biography.

Ishrāq al-Suwaydā’ al-‘Arūdiyyah, the servant of Abū al-Muṭarrif ‘Abd al-Raḥmān b. Ghalbūn al-Qurtubī al-Kātib. She resided in Valencia and learned the Arabic language, grammar, and literature from Abū al-Muṭarrif during her time in Cordoba. She then left that city when he departed from it. Although he was her teacher in many subjects, she soon surpassed him in knowledge in many of these fields and excelled in all of them. She was particularly knowledgeable about the theory and presentation of poetry. Abū Dāwūd Sulaymān b. Najāḥ, an expert reciter of the Qur’an, said: “I studied poetry under her and in her presence recited Abū ‘Alī’s Nawādir and Abū al-‘Abbās al-Mubarrad’s al-Kāmil. She had fully memorized both works and would often provide elaborate commentary on both.” She died in Denia while in the service of al-Sayyida bt. Mujāhid, whose name was Asmā’, the wife of al-Manṣūr Abū al-Ḥasan ‘Abd al-Azīz b. ‘Abd al-Raḥmān b. Abī ‘Āmir al-Manṣūr, who was the ruler of Valencia after the death of her master Abū al-Muṭarrif. [Ishrāq] died in Valencia in 443 AH [1051]. I have read and abridged this biography from a work about women by the Qur’anic recitation expert Abū Dāwūd, which was written in the hand of Ibn ‘Ayyād.

The daughter of Fā’iz al-Qurtubī and the wife of Abū ‘Abd Allāh b. ‘Uttāb, her name has not been preserved. She was among those who were renowned for her vast knowledge, literary skill and memorization abilities. She studied exegesis, grammar, Arabic and poetry with her father and studied jurisprudence and mysticism with her husband. She traveled from Cordoba to Denia in order to meet and study with the famous scholar and Qur’anic recitation expert Abū ‘Amr [al-Dānī], but he had fallen seriously ill and died. After attending his funeral, she asked about his students and was referred to Abū Dāwūd. She met him after he arrived in Valencia and learned the seven readings of the Qur’an from him. She had these fully memorized by 444 AH [1052]. Shortly thereafter, she journeyed to the East to make the Ḥajj but she died in Egypt in 446 AH [1054], during her return journey to al-Andalus. I have read all this in the handwriting of Ibn ‘Ayyād.

Zaynab bt. Abī ‘Umar Yūsuf b. ‘Abd Allāh b. Muḥammad b. ‘Abd al-Barr al-Numayrī. She studied with her father and resided with him in Sharq al-Andalus. She was among the most righteous women. She was the mother of Ibn ‘Abd al-Barr’s grandson Abū Muḥammad ‘Abd Allāh b. Alī al-Lakhmī. I am uncertain whether she died during the lifetime of her father or afterwards.

Fāṭimah bt. Abī ‘Alī al-Ḥusayn b. Muḥammad al-Ṣadafī. Although her family was originally from Zaragoza, she resided in Murcia. Her father left her when she was still an infant to join the military campaign in Cutanda [514/1120]. She was one of the righteous ascetics who memorized the Qur’an and lived her life in accordance with its precepts. She would also frequently recite many hadith, especially in her supplications. She had beautiful handwriting and was an avid reader of books. She married Abū Muḥammad ‘Abd Allāh b. Mūsa b. Burṭulah, the prayer leader of Murcia. They had several children, including a son named Abū Bakr ‘Abd al-Raḥmān. She died after 590 AH [1194] by which point she was over eighty years old.

Zaynab, the daughter of the [Almohad] caliph Abū Ya‘qūb Yūsuf b. Abī Muḥammad ‘Abd al-Mu’min b. ‘Alī [r. 558/1163–580/1184]. She was born in al-Andalus and married her cousin Abū Zayd b. Abī Ḥafṣ. She studied dialectical theology (‘ilm al-kalām) and other scholarly disciplines with Abū ‘Abd Allāh b. Ibrāhīm. She was an excellent scholar, highly intelligent, thoughtful in her opinions and undoubedly the most learned woman of her era. This is how Ibn Sālim described her to me. He did not mention the date of her death.

Fāṭima bt. Abī al-Qāsim ‘Abd al-Rahmān b. Muhammad b. Ghālib al-Ansārī al-Sharrāṭ. Originally from Cordoba, she was known as Umm al-Fath. She memorized the Qur’an and learned the Qur’anic recitation of Nāfi‘ from her father. Moreover, she mastered innumerable books under the guidance of her father, including al-Makki’s Tanbīh, al-Qudā‘ī’s al-Shihāb, and [Ibn ‘Ubayd] al-Ṭulayṭalī’s Mukhtasar. She also studied Sahīh Muslim, Ibn Hishām’s Sīra [of the Prophet], al-Mubarrad’s al-Kāmil, al-Baghdādī’s Nawādir, and other works with her father, who also taught her numerous other subjects. She even memorized the verses of his poetry dealing with the virtues of asceticism. She also memorized the Qur’an under the guidance of the great ascetic Abū ‘Abd Allāh al-Andūjarī and the ascetic Abū ‘Abd Allāh b. al-Mufaḍḍal. Her son Abū al-Qāsim b. al-Ṭaylasān narrated hadith from her and with her guidance memorized the Qur’an in the Warsh recitation. He also studied with her many of the works that she had memorized and studied with her father. Her son also studied various other works with her. She wrote him a certificate of audition (ijāzah), confirming his mastery of these works, in her own handwriting. He said: “I think that Abū Marwān b. Masarrah was among those that had provided her with a certificate [of transmission]. He was the one who named her, prayed for her and the individual to whom her father carried her [for blessings] on the day of her birth. She died in 613 AH [1216] and was buried in the cemetery of Umm Salamah alongside her father and brothers.

Zaynab bt. Muḥammad b. Aḥmad b. ‘Abd al-Raḥmān al-Zuhrī, known as ‘Azīzah. Her father was known as Ibn Muḥriz. She was from Valencia and studied with Abū al-Ḥasan b. Hudhayl, her maternal grandfather, memorizing Abū ‘Umar b. ‘Abd al-Barr’s Kitāb al-Taqaṣṣī under his tutelage. She only had a few students but many came to learn from her knowledge. She had bad handwriting. She lived longer than most and died on the night of Monday 15th of Jumāda I 635 AH [January 3rd 1238]. She was buried in the afternoon in the cemetery of Bāb Bayṭālah near the grave of the renowned Qur’an reciter Abū Dāwūd. I attended her funeral. She was born in 555 AH [1160] and had surpassed the age of eighty.

Sayyidah bt. ‘Abd al-Ghanī b. ‘Alī b. ‘Uthmān al-‘Abdarī, known as Umm al-‘Alā’. She was from Granada but her father—the cousin of Abū al-Ḥajjāj Yūsuf b. Ibrāhīm b. ‘Uthmān al-Thaghrī—lived in Murcia. Her family was originally from Lleida. Her father Abū Muḥammad served as a judge in Orihuela but died, leaving her orphaned while she was still young. She was raised in Murcia and learned the Qur’an and becoming proficient in its study. Her handwriting wa excellent. She taught in the residences and palaces of kings throughout her life until she was struck by a chronic illness that left her confined to her home for more than three years. Even in this incapacitated state, she focused on educating her two daughters, one who had reached maturityand the other who was still a young girl. She met Abū Zakariyyah al-Dimashqī in Granada. It was in Granada where she began teaching the Qur’an to others. Shortly thereafter, she briefly moved to Fez before returning to Granada and then traveled to Tunis where she was also appointed as a teacher in the royal palace. She transcribed a manuscript of Abū Ḥāmid al-Ghazālī’s Iḥyā’ ‘Ulūm al-Dīn in her own hand based on a copy that was in possession of the aforementioned Abū Zakariyyah. She was constantly engaged in the remembrance of God, the recitation of the Qur’an, promoting the good and giving charity. She devoted whatever she could spare from her wealth to freeing captives, until she was struck with a serious illness. She died from this illness on the afternoon of Tuesday 5th of Muḥarram 647 AH [April 20th 1249]. She was buried after the noon prayers on Wednesday close to the mosque on the outskirts of Tunis. May God have mercy upon her.

Dhūnah bt. ‘Abd al-‘Azīz b. Mūsa b. Ṭāhir b. Mutā‘, known as Umm Ḥabībah. She was the wife of Abū al-Qāsim b. Mudīr. She studied under Abū ‘Umar b. ‘Abd al-Barr and transcribed a few manuscripts of his works. She also studied under Abū al-‘Abbās al-‘Udhrī. Her husband, in turn, studied with her. She had elegant handwriting and was a noble, gracious and pious lady. She was born in 437 AH [1045] and died in 506 AH [1112]. She was mentioned by the shaykh [Ibn ‘Abd al-Malik] in his Dhayl: “Ibn Bashkūwāl referred to her not in his Kitāb al-Ṣila but in one of the commentaries on one of its volumes. I was informed of this by her son Abū Bakr. I transcribed this from a manuscript written in the hand of Abū al-Qāsim b. al-Maljūm, who himself stated that he had transcribed it from a manuscript written in the hand of Ibn Bashkūwāl.”

Layla, the freed-woman of the vizier Abū Bakr b. al-Khaṭṭāb. She was from Murcia. The eminent judge (qāḍī) Abū Bakr b. Abī Jamra praised her as being the greatest women of her era in knowledge and understanding of the various sciences. It was this fact, along with her magnanimity and piety, which led the chief judge of Granada, Abū al-Qāsim b. Hishām ibn Abī Jamra, himself an individual of noble lineage, immense knowledge and great piety, to marry her. Various people had previously sought her hand in marriage, but she had rejected them all. She did, however, agree to marry the judge Abū al-Qāsim, who fell deeply and passionately in love with her. Many of his opponents and critics rebuked him for this and said:

Tell Ibn Jamrah that the people say that Layla has enticed you or that you have been struck by madness

That he has parted with loyalty, piety and faith. Verily, he will be most remorseful for having been so deceived.

She died shortly before his accession to the judgeship of Granada, which he assumed in 528 AH [1133].

Ḥafṣa, daughter of the jurist and judge Abū ‘Imrān Mūsa b. Ḥammād al-Sanhājī. Al-Malāḥī said about her: “She was married to the judge Abū Bakr Muḥammad b. ‘Alī al-Ghassānī al-Marshānī. She was one of the best and most noble women. She had the Qur’an memorized and was quite skilled in handwriting. She also had an immense knowledge of the law and the obligations of faith. She would often quote many of her father’s fatwas on any given matter. She was born in 519 AH [1125] and died in Granada. She was buried in the Bāb Elvira cemetery.

Hafsa bt. Abī ‘Abd Allāh Muhammad b. Ahmad al-Salamī, commonly known as Ibn ‘Arūs. She mastered the seven readings of the Qur’an under the guidance of her father and also memorized many books of hadith, literature, and other scholarly disciplines. She also studied the Muwattā’. Al-Malāhī said: “I was informed that she recited the Muwattā’ in the presence of her father’s maternal uncle Abū Bakr Yaḥya b. ‘Arūs al-Tamīmī. She was very eloquent and one of the most well-read people. She could even read difficult handwriting and manuscripts that omitted vowels and diacritical marks with relative ease. She died at the young age of 27 on the 15th of Ramadan 580 AH [December 20th 1184].”

‘Ā’ishah, the daughter of the esteemed judge Abū al-Khaṭṭāb Muḥammad b. Aḥmad b. Khalīl. We have already mentioned her father, paternal uncles and several of his ancestors in this work. She narrated hadith from her father and studied with her father (may God have mercy upon him). She also received certificates of transmission from other scholars, but she would not refer to any of them [in her writings]. She was one of the righteous women who narrated a significant amount of the history of her own ancestors and other families. She was attentive, vigilant, and brilliant. She only had a few students.

[https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/islam/islamsbook.asp. Ibn Bashkuwal, Kitāb al-Ṣilah (Cairo, 2008), Vol. 2: 323-327. Ibn al-Abbār, Takmilat Kitāb al-Sila (Tunis: Dar al-Gharb al-Islami, 2001), Vol. 4, pp. 222–247. Abū Ja’far Ahmad b. Ibrāhīm ibn al-Zubayr al-Gharnāṭī, Kitāb Ṣilat al-Ṣila (Beirut, 2008), pp. 455-460.]

Fāṭima b. Yahya b. Yūsuf al-Maghāmī. She was the sister of the great jurist Yūsuf b. Yahya al-Maghāmī. She was amongst the most knowledgeable, most magnanimous and wisest individuals in her era. She lived in Cordoba and died there around 319 AH [931]. She was buried in the suburbs of the city and her funeral was among the greatest ever witnessed for a woman of the city.

‘Ā’isha b. Ahmad b. Muhammad b. Qādim. She was from Cordoba. The famous historian [Abū Marwān Ḥayyān ibn Khalaf] Ibn Hayyān [d. 469/1075] said about her: “There was none in the entire Iberian Peninsula in her era that could be compared with her in terms of knowledge, excellence, literary skill, poetic ability, eloquence, virtue, purity, generosity, and wisdom. She would often write panegyrics in praise of the kings of her era and would give speeches in their court. She was a very skilled calligrapher and copied many manuscripts of the Qur’an and other books. She was an avid collector of books, of which she had a very large amount, and was very concerned with the pursuit of knowledge. She was also very wealthy and died chaste, without having ever married. She died in the year 400 AH [1009].

Khadījah b. Ja’far b. Nusayr b. Tammār al-Tamīmī. She was the wife of the renowned jurist ‘Abd Allāh b. Asad and narrated al-Qa’nabi’s Muwattā’ from him. After learning it, she even transcribed a copy of that book in the year 394 AH [1003]. I heard my own shaykh Abū al-Ḥasan ibn al-Mughīth (may God have mercy upon him) mention this. He also mentioned that this book was actually in his possession, and I later saw it myself.