14. Progressive women

|

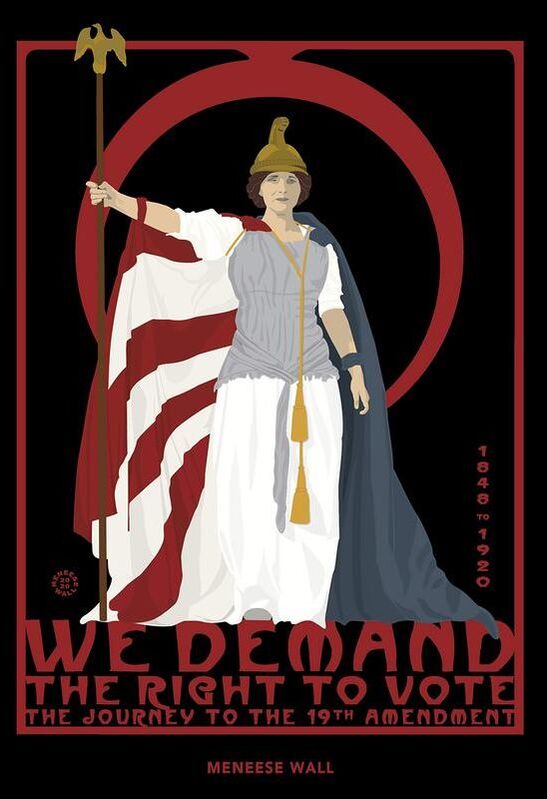

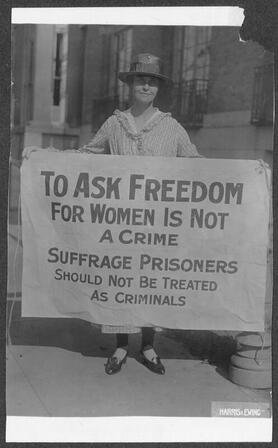

In the absence of the vote, women sought change through progressive social movements, efforts that stretched the traditional roles of women, and dragged them ever-more into politics. Women sought reform on temperance, child labor, lynching, public schools, and more. Women's efforts were central to and the backbone of the progressive.

|

Woman Protesting, Library of Congress

Woman Protesting, Library of Congress

The industrial revolution wasn’t very revolutionary for women. While new technologies revolutionized the public sphere, the domestic sphere remained inefficient. Women increasingly took jobs outside the home and life became a bit faster, but law had not yet caught up with societal change. Children were laboring in factories, alcoholism was rampant, public education was underfunded and limited, immigrants needed support, and more. Women led the way to reform society in what today is known as the Progressive Era.

Forewarning, this chapter will discuss lynchings and racial violence.

Between about 1890 and 1914, the United States experienced a period of reform that has earned the label “Progressive.” Women were active leaders of reform groups, guaranteeing the safety of the food supply, supporting crusades for temperance, the elimination of child labor, and the improvement of working conditions in factories. Women’s writing, organizing, and protesting efforts were not always successful, but they did raise the consciousness of the American public to many of the negative consequences of rapid industrialization.

Forewarning, this chapter will discuss lynchings and racial violence.

Between about 1890 and 1914, the United States experienced a period of reform that has earned the label “Progressive.” Women were active leaders of reform groups, guaranteeing the safety of the food supply, supporting crusades for temperance, the elimination of child labor, and the improvement of working conditions in factories. Women’s writing, organizing, and protesting efforts were not always successful, but they did raise the consciousness of the American public to many of the negative consequences of rapid industrialization.

Women Protesting Jim Crow Laws, Britannica

Women Protesting Jim Crow Laws, Britannica

Considering the time, the Progressive Era was incredibly intersectional with women reformers working on many issues from industrialization to race relations.

Jim Crow:

During the Progressive Era, race relations stagnated. Racial violence, riots, and neglect of Black Americans prevailed. Black women played a vital role in combating racism and organizing for change. Jim Crow laws severely oppressed Black women, impacting education, employment, accommodations, and voting rights. They resisted these injustices through activism.

Segregated schools for Black students were often underfunded and provided inferior resources and facilities compared to those available to white students. Black women, along with other community members, worked tirelessly to establish and maintain independent schools, known as "colored schools," to provide better educational opportunities for Black children.

Jim Crow laws enforced racial segregation in public spaces, including restaurants, theaters, and transportation. Black women faced humiliation, violence, and denial of basic services and accommodations. In response, Black women organized boycotts, sit-ins, and protests, advocating for equal access and challenging the discriminatory policies.

Jim Crow:

During the Progressive Era, race relations stagnated. Racial violence, riots, and neglect of Black Americans prevailed. Black women played a vital role in combating racism and organizing for change. Jim Crow laws severely oppressed Black women, impacting education, employment, accommodations, and voting rights. They resisted these injustices through activism.

Segregated schools for Black students were often underfunded and provided inferior resources and facilities compared to those available to white students. Black women, along with other community members, worked tirelessly to establish and maintain independent schools, known as "colored schools," to provide better educational opportunities for Black children.

Jim Crow laws enforced racial segregation in public spaces, including restaurants, theaters, and transportation. Black women faced humiliation, violence, and denial of basic services and accommodations. In response, Black women organized boycotts, sit-ins, and protests, advocating for equal access and challenging the discriminatory policies.

Ida. B Wells, Wikimedia Commons

Ida. B Wells, Wikimedia Commons

Jim Crow laws aimed to suppress the political power of Black women and men by implementing poll taxes, literacy tests, and other voter suppression tactics. Despite these obstacles, Black women played a crucial role in mobilizing and organizing voter registration campaigns, advocating for suffrage, and fighting for equal representation.

Prominent Black women activists such as Ida B. Wells-Barnett, Mary Church Terrell, and many others led and participated in resistance movements against Jim Crow laws. They used various strategies such as grassroots organizing, civil disobedience, public speaking, journalism, and legal challenges to expose the injustices and fight for civil rights and social equality.

In 1884, Wells-Barnett sued a railroad company in Memphis, Tennessee for forcing her into a segregated car, even though she had a valid first-class ticket. She won her case at the local level but lost on appeal. This case was among the first of many in which African-Americans sought relief for discrimination in the courts. Wells-Barnett also organized a boycott of the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893 for the World’s Fair’s negative portrayal of people of color.

Prominent Black women activists such as Ida B. Wells-Barnett, Mary Church Terrell, and many others led and participated in resistance movements against Jim Crow laws. They used various strategies such as grassroots organizing, civil disobedience, public speaking, journalism, and legal challenges to expose the injustices and fight for civil rights and social equality.

In 1884, Wells-Barnett sued a railroad company in Memphis, Tennessee for forcing her into a segregated car, even though she had a valid first-class ticket. She won her case at the local level but lost on appeal. This case was among the first of many in which African-Americans sought relief for discrimination in the courts. Wells-Barnett also organized a boycott of the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893 for the World’s Fair’s negative portrayal of people of color.

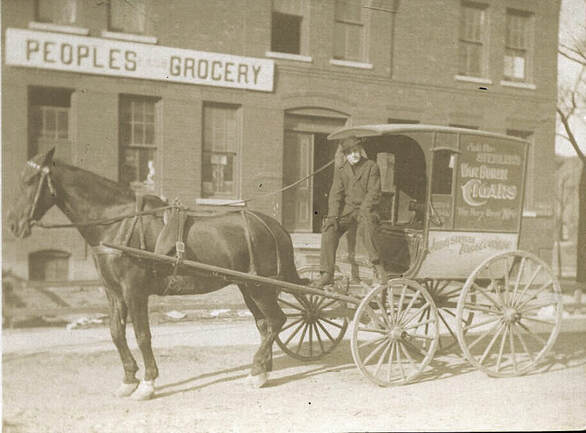

The People's Grocery Store, Wikimedia Commons

The People's Grocery Store, Wikimedia Commons

Lynching:

The effect of widespread social, political, and economic discrimination against Black people in America was prejudice driven racial violence, and even state violence against Black people.

One incident of racial violence in particular would inspire perhaps one of the most significant American women in history. Thomas Moss, Calvin McDowell, and Henry Stewart lived in Memphis, Tennessee and owned the People's Grocery Company, which competed with a nearby white-owned store. In 1892 a dispute between Black and white residents escalated, leading to violence. Moss and his associates were arrested, but before they could stand trial, a white mob stormed the jail, brutally murdered the three men, and burned down their store. The incident hit Ida B. Wells-Barnett deeply. The lynching of her close friends served as a turning point in her life and activism. She moved to Chicago and began investigating and documenting lynchings, aiming to expose the true motivations behind these acts of racial violence. In her pamphlets, she exposed the systemic racism and sexism, white supremacist ideologies, and economic competition that often lay behind lynchings, challenging the prevailing narrative that portrayed Black victims as criminals deserving punishment.

She also used her platform to defend Black men in particular against the racial and gendered fallacy of the Black-male predator. White people stoked fear that Black men were out to rape and molest their white daughters and so white women needed to be protected and segregated from Black men. Not only was this not statistically true, it was in fact the exact opposite based on criminal records. White men were molesting Black women. Wells wrote, “There are thousands of such cases throughout the South, with the difference that the Southern white men in insatiate fury wreak their vengeance without intervention of law upon the Afro-Americans who consort with their women.”

The effect of widespread social, political, and economic discrimination against Black people in America was prejudice driven racial violence, and even state violence against Black people.

One incident of racial violence in particular would inspire perhaps one of the most significant American women in history. Thomas Moss, Calvin McDowell, and Henry Stewart lived in Memphis, Tennessee and owned the People's Grocery Company, which competed with a nearby white-owned store. In 1892 a dispute between Black and white residents escalated, leading to violence. Moss and his associates were arrested, but before they could stand trial, a white mob stormed the jail, brutally murdered the three men, and burned down their store. The incident hit Ida B. Wells-Barnett deeply. The lynching of her close friends served as a turning point in her life and activism. She moved to Chicago and began investigating and documenting lynchings, aiming to expose the true motivations behind these acts of racial violence. In her pamphlets, she exposed the systemic racism and sexism, white supremacist ideologies, and economic competition that often lay behind lynchings, challenging the prevailing narrative that portrayed Black victims as criminals deserving punishment.

She also used her platform to defend Black men in particular against the racial and gendered fallacy of the Black-male predator. White people stoked fear that Black men were out to rape and molest their white daughters and so white women needed to be protected and segregated from Black men. Not only was this not statistically true, it was in fact the exact opposite based on criminal records. White men were molesting Black women. Wells wrote, “There are thousands of such cases throughout the South, with the difference that the Southern white men in insatiate fury wreak their vengeance without intervention of law upon the Afro-Americans who consort with their women.”

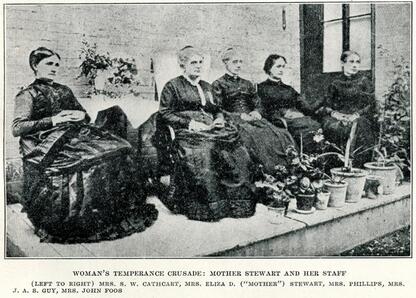

Woman's Temperance Members, Ohio State University

Woman's Temperance Members, Ohio State University

Temperance:

Gender dynamics hit every progressive cause including the crusade for temperance. The image of the male factory worker drinking away his weekly salary while his wife and children starved motivated Progressive Era women to pick up the cause for abstinence from alcohol where their grandmothers had left off. In the 19th century, temperance, not suffrage, was the largest, most politically powerful women’s movement.

The struggle for a ban on alcohol was a mass women-led movement. Alcohol was associated with poverty and violence inflicted on wives by their inebriated husbands. But at the beginning of the twentieth century, state and local legal systems gave husbands almost total authority and control over their wives, up to and including inflicting serious physical damage, casting a woman out of the home, and taking full custody of children.

The Women's Crusade was a grassroots movement that emerged in Ohio in the early 1870s. It was a significant precursor to the larger temperance movement. Groups of women organized and conducted prayer meetings, hymn singing, and peaceful demonstrations outside saloons and alcohol-selling establishments. They would enter these establishments, often singing hymns and praying for the owners and patrons to give up alcohol. The Women's Crusade was remarkable for its emphasis on women's moral authority and their ability to effect change through peaceful and persuasive means.

However, despite its initial momentum and the fervor of its participants, the Women's Crusade ultimately failed due to the formidable and well funded resistance posed by the alcohol industry.

Gender dynamics hit every progressive cause including the crusade for temperance. The image of the male factory worker drinking away his weekly salary while his wife and children starved motivated Progressive Era women to pick up the cause for abstinence from alcohol where their grandmothers had left off. In the 19th century, temperance, not suffrage, was the largest, most politically powerful women’s movement.

The struggle for a ban on alcohol was a mass women-led movement. Alcohol was associated with poverty and violence inflicted on wives by their inebriated husbands. But at the beginning of the twentieth century, state and local legal systems gave husbands almost total authority and control over their wives, up to and including inflicting serious physical damage, casting a woman out of the home, and taking full custody of children.

The Women's Crusade was a grassroots movement that emerged in Ohio in the early 1870s. It was a significant precursor to the larger temperance movement. Groups of women organized and conducted prayer meetings, hymn singing, and peaceful demonstrations outside saloons and alcohol-selling establishments. They would enter these establishments, often singing hymns and praying for the owners and patrons to give up alcohol. The Women's Crusade was remarkable for its emphasis on women's moral authority and their ability to effect change through peaceful and persuasive means.

However, despite its initial momentum and the fervor of its participants, the Women's Crusade ultimately failed due to the formidable and well funded resistance posed by the alcohol industry.

Frances Willard, Wikimedia Commons

Frances Willard, Wikimedia Commons

The largest temperance organization was the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, or WCTU, which had chapters all over the country. The first president of the Women's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) was Annie Wittenmyer. She served as the organization's president from its founding in 1874 until 1879. However, it is important to note that while Annie Wittenmyer was the first president, she did not hold this position for an extended period. She was retrained in her approach and failed to see the way in which various women’s organizations could work together to the same end, in particular suffrage. She viewed the suffrage movement as separate from the temperance movement and did not prioritize it.

Frances Willard succeeded her and served as the president of the WCTU from 1879 until her death in 1898. Under her leadership, the organization became the largest women's organization of its time, with thousands of members across the United States and around the world. Willard's organizational skills, strategic thinking, and oratory skills helped the WCTU grow in size and influence. Under Willard’s leadership, the WCTU officially endorsed suffrage in 1881, and many WCTU members actively campaigned for women's voting rights.

Frances Willard succeeded her and served as the president of the WCTU from 1879 until her death in 1898. Under her leadership, the organization became the largest women's organization of its time, with thousands of members across the United States and around the world. Willard's organizational skills, strategic thinking, and oratory skills helped the WCTU grow in size and influence. Under Willard’s leadership, the WCTU officially endorsed suffrage in 1881, and many WCTU members actively campaigned for women's voting rights.

WCTU Meeting, Piedmont Digital History

WCTU Meeting, Piedmont Digital History

The WCTU held conferences, protested outside taverns to embarrass male drinkers, and even hacked open barrels of whiskey. Carrie Nation was fed up with the state of Kansas’ failure to enforce anti alcohol laws and, convinced God had sent her, walked into bars and destroyed them with small rocks she called “smashers.” After her then husband picked her up from jail he ridiculed her and gave her the idea that would become her signature. He said she would be more effective if she used a hatchet, so she did. She went to bar after bar, town after town, smashing, amassing a following of members from the WCTU. They eventually divorced.

In the 1880s, the WCTU wanted to push for federal laws, so they started setting up chapters in the South. They thought that white Southern women could make a big impact in furthering these causes, but they faced some challenges. The society in the South had strict traditional gender roles, and lots of women didn't support suffrage because they were worried it would undermine their status as proper Southern "ladies." On top of that, many white Southern women were hesitant about collaborating with Black women.

Similarly, the WCTU was also active in Indigenous communities across the country—sometimes in cooperation with their women, though at other times in direct conflict with them. Given the devastating effect of alcohol consumption in their communities, Indigenous women often joined or partnered with the WCTU to improve the enforcement of existing laws banning the sale of alcohol to individuals of Native descent but also to promote abstinence amongst their own people. This proved to be a slippery slope, however, as efforts to instill temperance were often followed by and used as justification to separate Indigenous children from their families, promote conversion to Christianity, and overall, forcibly assimilate Indigenous peoples.

Ida B. Wells-Barnett was a member of the Women’s Christian Temperance union. She used her platform to battle for an intersectional approach to temperance and took to the press to challenge Willard to take a stand against lynchings in the south. Willard was worried that a public position on lynching would hurt the temperance cause in the south. Willard insisted that she had "not an atom of race prejudice," but her statements in the press upheld racial stereotypes and portrayed black men as specifically threatening white women.

Wells called her a coward. Willard eventually convinced the WCTU to put out a position statement on lynching after a private meeting with Wells.

In the 1880s, the WCTU wanted to push for federal laws, so they started setting up chapters in the South. They thought that white Southern women could make a big impact in furthering these causes, but they faced some challenges. The society in the South had strict traditional gender roles, and lots of women didn't support suffrage because they were worried it would undermine their status as proper Southern "ladies." On top of that, many white Southern women were hesitant about collaborating with Black women.

Similarly, the WCTU was also active in Indigenous communities across the country—sometimes in cooperation with their women, though at other times in direct conflict with them. Given the devastating effect of alcohol consumption in their communities, Indigenous women often joined or partnered with the WCTU to improve the enforcement of existing laws banning the sale of alcohol to individuals of Native descent but also to promote abstinence amongst their own people. This proved to be a slippery slope, however, as efforts to instill temperance were often followed by and used as justification to separate Indigenous children from their families, promote conversion to Christianity, and overall, forcibly assimilate Indigenous peoples.

Ida B. Wells-Barnett was a member of the Women’s Christian Temperance union. She used her platform to battle for an intersectional approach to temperance and took to the press to challenge Willard to take a stand against lynchings in the south. Willard was worried that a public position on lynching would hurt the temperance cause in the south. Willard insisted that she had "not an atom of race prejudice," but her statements in the press upheld racial stereotypes and portrayed black men as specifically threatening white women.

Wells called her a coward. Willard eventually convinced the WCTU to put out a position statement on lynching after a private meeting with Wells.

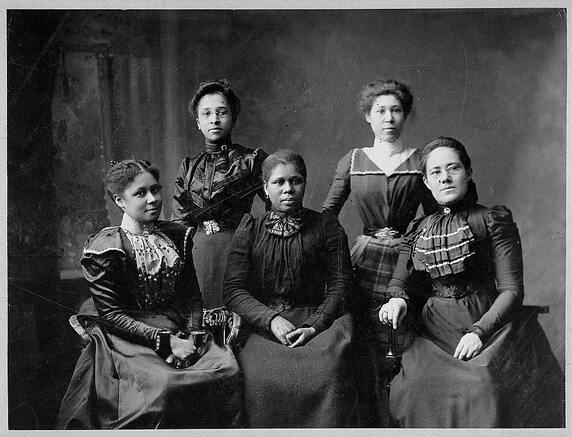

Black Women's Clubs, Wikimedia Commons

Black Women's Clubs, Wikimedia Commons

By 1917, rural and religious forces contributed to Congress's passage of the 18th amendment, which prohibited the manufacture, sale, and distribution of alcohol. The amendment was the law of the land in the United States until its repeal in 1933.

Black Women’s Clubs:

The second class status that Black women experienced in organizations like Temperance and Suffrage led Black women to form political clubs. Black women experienced intersecting forms of discrimination based on their race and gender. They faced racial segregation, limited access to education, employment discrimination, and restricted civil rights.

Black women's clubs provided a platform for addressing gender-specific issues and fostering solidarity among Black women. In this context, middle and upper class Black women adopted the “politics of respectability,” a set of social and cultural norms aimed at countering negative racial stereotypes and gaining acceptance within the larger society. They encouraged Black women to conform to societal expectations of proper behavior, appearance, and morality. It emphasized the importance of education, chastity, self-discipline, economic success, and adherence to traditional gender roles. By adhering to these standards, Black women sought to challenge prevailing racist beliefs that portrayed them as inferior or morally degenerate.

Critics argued that respectability politics served as a means of attaining acceptance, rather than advocating for structural change and social justice, which arguably would have helped Black women more.

Black Women’s Clubs:

The second class status that Black women experienced in organizations like Temperance and Suffrage led Black women to form political clubs. Black women experienced intersecting forms of discrimination based on their race and gender. They faced racial segregation, limited access to education, employment discrimination, and restricted civil rights.

Black women's clubs provided a platform for addressing gender-specific issues and fostering solidarity among Black women. In this context, middle and upper class Black women adopted the “politics of respectability,” a set of social and cultural norms aimed at countering negative racial stereotypes and gaining acceptance within the larger society. They encouraged Black women to conform to societal expectations of proper behavior, appearance, and morality. It emphasized the importance of education, chastity, self-discipline, economic success, and adherence to traditional gender roles. By adhering to these standards, Black women sought to challenge prevailing racist beliefs that portrayed them as inferior or morally degenerate.

Critics argued that respectability politics served as a means of attaining acceptance, rather than advocating for structural change and social justice, which arguably would have helped Black women more.

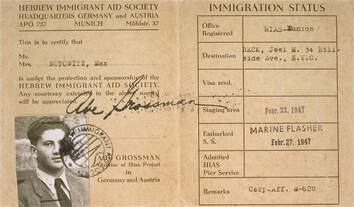

HIAS, Holocaust Encyclopedia

HIAS, Holocaust Encyclopedia

Immigration:

During the Progressive era, almost 30 million immigrants came from around the world to port cities like New York and Los Angeles before traveling further to the interior. Ethnic neighborhoods popped up everywhere as people settled near people from their home countries for social as well as practical support as they navigated a new nation.

Anti-immigrant sentiment raged around the turn of the twentieth century. Nativists argued that refugees from poverty in Italy and pogroms in Russia could not assimilate into their vision of a white and Protestant America. Fulfilling maternal roles, many middle-class and wealthy women were moved by the plight of the new immigrants to provide material help to the new arrivals. The Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS) was founded in 1881 by Jews of German ancestry to provide aid to poor immigrants.

During the Progressive era, almost 30 million immigrants came from around the world to port cities like New York and Los Angeles before traveling further to the interior. Ethnic neighborhoods popped up everywhere as people settled near people from their home countries for social as well as practical support as they navigated a new nation.

Anti-immigrant sentiment raged around the turn of the twentieth century. Nativists argued that refugees from poverty in Italy and pogroms in Russia could not assimilate into their vision of a white and Protestant America. Fulfilling maternal roles, many middle-class and wealthy women were moved by the plight of the new immigrants to provide material help to the new arrivals. The Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS) was founded in 1881 by Jews of German ancestry to provide aid to poor immigrants.

Lillian Wald, Wikimedia Commons

Lillian Wald, Wikimedia Commons

In 1893, Lillian Wald founded the Henry Street Settlement in New York to provide English language classes, health care, and other social services to the Lower East Side immigrant community.

The Henry Street Settlement followed the example of Chicago’s Hull House, founded in 1889 in a poor neighborhood of the city by Jane Addams, Jane Gates Starr and a small group of women dedicated to serving the needs of poor people who had no political voice or power. Addams, a graduate of the Rockford Female Seminary, grew up with a strong commitment to social justice and humanitarian service. Addams used her organizing ability to improve sanitary conditions in the Hull House neighborhood, and she provided a wide range of services and classes to immigrants who worked in Chicago’s factories and slaughterhouses. An opponent of World War I, Addams served as President of the Women’s Peace Party and later the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. An avid and active feminist, she supported women’s suffrage and was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1931, a few days before her death.

The Henry Street Settlement followed the example of Chicago’s Hull House, founded in 1889 in a poor neighborhood of the city by Jane Addams, Jane Gates Starr and a small group of women dedicated to serving the needs of poor people who had no political voice or power. Addams, a graduate of the Rockford Female Seminary, grew up with a strong commitment to social justice and humanitarian service. Addams used her organizing ability to improve sanitary conditions in the Hull House neighborhood, and she provided a wide range of services and classes to immigrants who worked in Chicago’s factories and slaughterhouses. An opponent of World War I, Addams served as President of the Women’s Peace Party and later the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. An avid and active feminist, she supported women’s suffrage and was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1931, a few days before her death.

Marie Van Vorst, Wikimedia Commons

Marie Van Vorst, Wikimedia Commons

Muckrakers:

Progressive women believed in the power of the written word and picked up their pen to improve society. Teddy Roosevelt dubbed these writers of the period Muckrakers because they were “raking through the muck” of American society. These women were sure that, if the American public could be informed about the evils of the factory system, citizens would support efforts to raise wages, limit working hours, promote the production of healthy food, and end child labor. These efforts were frequently couched in terms of protecting women and families from the evils of industrialization. Reporters like Marie Van Vorst wrote numerous exposes of factory conditions. Van Vorst, who came from a wealthy family, posed as a factory girl in Lynn, Massachusetts. Her descriptions of conditions of the workers in a shoe factory there led to the publication of The Woman Who Toils in 1903. While efforts to curb working hours, raise wages, or improve conditions in the factory did not bear fruit until the 1930s, reformers, including writers for “Good Housekeeping” magazine were successful in lobbying for the passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act in 1906. Once again, women were successful in achieving reforms through a maternal approach to social reform.

Progressive women believed in the power of the written word and picked up their pen to improve society. Teddy Roosevelt dubbed these writers of the period Muckrakers because they were “raking through the muck” of American society. These women were sure that, if the American public could be informed about the evils of the factory system, citizens would support efforts to raise wages, limit working hours, promote the production of healthy food, and end child labor. These efforts were frequently couched in terms of protecting women and families from the evils of industrialization. Reporters like Marie Van Vorst wrote numerous exposes of factory conditions. Van Vorst, who came from a wealthy family, posed as a factory girl in Lynn, Massachusetts. Her descriptions of conditions of the workers in a shoe factory there led to the publication of The Woman Who Toils in 1903. While efforts to curb working hours, raise wages, or improve conditions in the factory did not bear fruit until the 1930s, reformers, including writers for “Good Housekeeping” magazine were successful in lobbying for the passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act in 1906. Once again, women were successful in achieving reforms through a maternal approach to social reform.

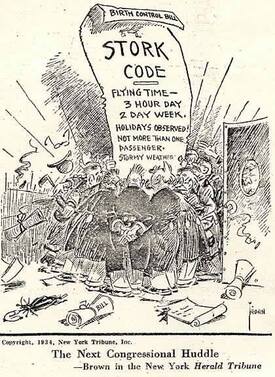

Political Cartoon of the Comstock Act, 1934

Political Cartoon of the Comstock Act, 1934

Reproductive Justice:

The Progressive Era was also a crucial period in the struggle for reproductive justice. State laws enacted during this time sought to control women's reproductive choices and limit access to contraception and abortion. These laws reflected the prevailing cultural and ideological shifts of the era, but they also sparked resistance and advocacy, laying the groundwork for future battles for reproductive rights. Examining this historical context reminds us of the importance of reproductive autonomy and the ongoing struggle for reproductive justice in contemporary society.

State laws enacted in the late 19th century often aimed to restrict women's reproductive autonomy, reflecting prevailing societal values and the influence of religious and moral beliefs. These laws varied across states but generally criminalized the dissemination and use of contraceptives and established restrictions on abortion. The Comstock Act of 1873, at the federal level, prohibited the distribution of obscene materials, including contraceptive devices and information, effectively limiting women's access to birth control methods. The Comstock Act was prompted primarily by Anthony Comstock, an influential social reformer and anti-vice crusader of the late 19th century. Comstock was a devout Christian and a special agent of the United States Postal Service, tasked with enforcing laws related to obscenity and vice.

The Comstock Act faced significant criticism from advocates of women's rights, reproductive health, and civil liberties. They argued that the act violated freedom of speech, limited access to vital healthcare information, and disproportionately affected women's rights and reproductive autonomy. Moreover, the laws disproportionately affected low-income women and women of color, as they often faced limited resources and greater difficulties in accessing reproductive healthcare.

The Progressive Era was also a crucial period in the struggle for reproductive justice. State laws enacted during this time sought to control women's reproductive choices and limit access to contraception and abortion. These laws reflected the prevailing cultural and ideological shifts of the era, but they also sparked resistance and advocacy, laying the groundwork for future battles for reproductive rights. Examining this historical context reminds us of the importance of reproductive autonomy and the ongoing struggle for reproductive justice in contemporary society.

State laws enacted in the late 19th century often aimed to restrict women's reproductive autonomy, reflecting prevailing societal values and the influence of religious and moral beliefs. These laws varied across states but generally criminalized the dissemination and use of contraceptives and established restrictions on abortion. The Comstock Act of 1873, at the federal level, prohibited the distribution of obscene materials, including contraceptive devices and information, effectively limiting women's access to birth control methods. The Comstock Act was prompted primarily by Anthony Comstock, an influential social reformer and anti-vice crusader of the late 19th century. Comstock was a devout Christian and a special agent of the United States Postal Service, tasked with enforcing laws related to obscenity and vice.

The Comstock Act faced significant criticism from advocates of women's rights, reproductive health, and civil liberties. They argued that the act violated freedom of speech, limited access to vital healthcare information, and disproportionately affected women's rights and reproductive autonomy. Moreover, the laws disproportionately affected low-income women and women of color, as they often faced limited resources and greater difficulties in accessing reproductive healthcare.

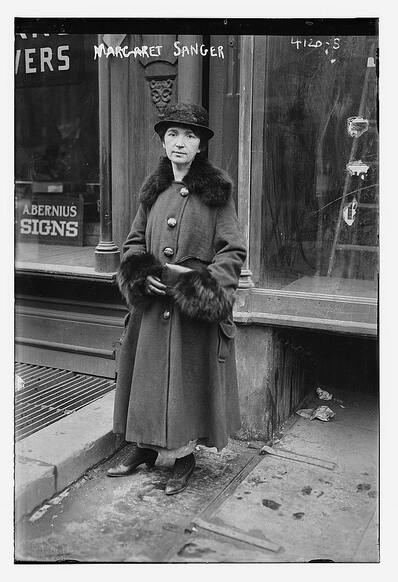

Margaret Sanger, Library of Congress

Margaret Sanger, Library of Congress

Activists such as Margaret Sanger and Emma Goldman fought for women's reproductive rights, aiming to challenge the status quo and provide access to contraceptive methods and safe abortion services. These early pioneers paved the way for future reproductive justice movements, establishing a foundation for the fight for bodily autonomy and reproductive freedom.

Margaret Sanger’s reputation as a heroic fighter for a woman’s right to control her reproductive life is marred by her eugenicist views that stood in contrast to the work she did to help the very poor women whose value to society she denied. Early in her career, Sanger abandoned nursing to establish a clinic that provided basic contraceptive information to women in New York. A founder of Planned Parenthood, Sanger believed that having fewer children was beneficial to poor families and could help lift them out of poverty.

Emma Goldman, an immigrant from Russia, was a vocal proponent of birth control and reproductive freedom, advocating for women's right to access contraception at a time when it was heavily restricted. As an anarchist, she believed that women should have control over their bodies and reproductive choices, and she played a significant role in raising awareness about contraception methods and challenging the legal and societal barriers surrounding it. She was eventually arrested for distributing information about birth control and deported to Russia.

Conclusion:

By the end of this era, so much remained in question. Would writing books and articles and organizing commissions to lobby for social change be sufficient to bring about improved conditions for Americans? Even as women worked hard for change, do you think they found themselves limited by the fact that they did not yet have the vote? Do you think Progressive women were successful? What was the role of race in limiting the activism of many women in this period?

Margaret Sanger’s reputation as a heroic fighter for a woman’s right to control her reproductive life is marred by her eugenicist views that stood in contrast to the work she did to help the very poor women whose value to society she denied. Early in her career, Sanger abandoned nursing to establish a clinic that provided basic contraceptive information to women in New York. A founder of Planned Parenthood, Sanger believed that having fewer children was beneficial to poor families and could help lift them out of poverty.

Emma Goldman, an immigrant from Russia, was a vocal proponent of birth control and reproductive freedom, advocating for women's right to access contraception at a time when it was heavily restricted. As an anarchist, she believed that women should have control over their bodies and reproductive choices, and she played a significant role in raising awareness about contraception methods and challenging the legal and societal barriers surrounding it. She was eventually arrested for distributing information about birth control and deported to Russia.

Conclusion:

By the end of this era, so much remained in question. Would writing books and articles and organizing commissions to lobby for social change be sufficient to bring about improved conditions for Americans? Even as women worked hard for change, do you think they found themselves limited by the fact that they did not yet have the vote? Do you think Progressive women were successful? What was the role of race in limiting the activism of many women in this period?

Draw your own conclusions

|

Learn how to teach with inquiry.

Many of these lesson plans were sponsored in part by the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources Eastern Region Program, coordinated by Waynesburg University, the History and Social Studies Education Faculty at Plymouth State University, and the Patrons of the Remedial Herstory Project. |

Lesson Plans from Other Organizations

- The National Women's History Museum has lesson plans on women's history.

- The Gilder Lehrman Institute for American History has lesson plans on women's history.

- The NY Historical Society has articles and classroom activities for teaching women's history.

- Unladylike 2020, in partnership with PBS, has primary sources to explore with students and outstanding videos on women from the Progressive era.

- The Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media has produced recommendations for teaching women's history with primary sources and provided a collection of sources for world history. Check them out!

- The Stanford History Education Group has a number of lesson plans about women in US History.

Period Specific Lesson Plans from Other Organizations

- Unladylike: Learn about the pioneering industrial engineer and psychologist, Lillian Moller Gilbreth, in this digital short from Unladylike2020. Using video, vocabulary and discussion questions, students learn about how her innovations improved American’s lives in both factories and the home.

- Unladylike: Learn about Susan La Flesche Picotte, the first American Indian physician and the first to found a private hospital on an American Indian reservation, in this video from the Unladylike2020 series. Susan La Flesche Picotte grew up on the Omaha Reservation in Nebraska against the backdrop of the Dawes Act of 1887 which sought to force indigenous tribes onto reservations and foster their assimilation into white society. Neither of her parents spoke English, but they encouraged her pursuit of an Anglo-American education. Picotte graduated from Women’s Medical College in 1889 and returned to the Omaha reservation to spend her career making house calls on foot, horse, and horse-drawn buggy across its 1,350 square miles. Also a fierce community leader, Picotte worked tirelessly to help her tribe combat the theft of American Indian land and public health crises including the spread of tuberculosis and alcoholism. Support materials include discussion questions, research project ideas, and primary source analysis.

- Unladylike: Learn about Annie Smith Peck, one of the first women in America to become a college professor and who took up mountain climbing in her forties, in this video from Unladylike2020. Peck gained international fame in 1895 when she first climbed the Matterhorn in the Swiss Alps -- not for her daring ascent, but because she undertook the climb wearing pants rather than a cumbersome skirt. Fifteen years later, at age 58, Peck was the first mountaineer ever to conquer Mount Huascarán in Peru, one of the highest peaks in the Western Hemisphere. Support materials include discussion questions, vocabulary, and teaching tips for extending learning through research projects.

- Voices of Democracy: There is a chasm in history classes between the Civil War and World War I in which it is difficult to engage students. If the Progressive Era is taught strictly through the historical facts—of unions, poor working conditions, Theodore Roosevelt’s reforms, and so on—students may have a difficult time envisioning the era’s importance to American history. This speech by Mary Harris ‘Mother’ Jones helps draw students into the Progressive Era in two ways. First, Jones’s vivid and cantankerous personality certainly draws students’ attention. She represents an important female voice during an era before women had the right to vote. Secondly, Jones’s speech provides an illustrative entry point to help students understand the working conditions that triggered the Progressive Movement, the intensity of the disputes between workers and their employers, and the formation of labor unions in the United States.

- National Womens History Museum: This lesson sees to explore the multifaceted and nuanced ways in which Helen Keller is remembered. By starting with an entry level text, students will be exposed to the way in which Keller is taught to elementary and middle school students. From there, students will seek to rewrite the story on Helen Keller using primary sources via a jigsaw activity to generate meaning. Students will consider the role of historical memory and consider the ways in which some of the ideas and beliefs of historical actors are ignored by history.

- Stanford History Education Group: Some historians have characterized Progressive reformers as generous and helpful. Others describe the reformers as condescending elitists who tried to force immigrants to accept Christianity and American identities. In this structured academic controversy, students read documents written by reformers and by an immigrant to investigate American attitudes during the Progressive Era.

- National History Day: Dorothea Lynde Dix (1802-1887) was born in Hampden, Maine, to a poor family. At age 12 she went to live with her grandmother in Boston. When she was only 14, Dix founded a school in Worcester, Massachusetts. After a 20-year career as a teacher and writer, in 1841 Dix visited a jail in East Cambridge, Massachusetts, and was appalled by the conditions. Many of the prisoners were mentally ill, and they were treated terribly by being ill-fed and abused. Dix took it upon herself to report these condition to the Massachusetts Legislature in 1843, documenting the poor conditions faced by hundreds of mentally ill men and women. Her action led to the successful passage of a bill to reform the way the state treated prisoners and people with mental illness. Dix canvassed the country working for prison reform and improved conditions for the mentally ill. Eventually her crusade became international. She even lobbied the pope in person about conditions in Italy. During the Civil War Dix served without pay as superintendent of nurses for the Union Army in the U.S. Sanitary Commission. She died on July 17, 1887, in a Trenton, New Jersey, hospital that she had founded.

- National History Day: Ida B. Wells (1862-1931) was born to slave parents in Holly Springs, Mississippi, on July 16, 1862, two months before President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. As a young girl, Wells watched her parents work as political activists during Reconstruction. In 1878, tragedy struck as Wells lost both of her parents and a younger brother in a yellow fever epidemic. To support her younger siblings, Wells became a teacher, eventually moving to Memphis, Tennessee. In 1884, Wells found herself in the middle of a heated lawsuit. After purchasing a first-class train ticket, Wells was ordered to move to a segregated car. She refused to give up her seat and was forcibly removed from the train. Wells filed suit against the railroad and won. This victory was short lived, however, as the Tennessee Supreme Court overturned the lower court ruling in 1887. In 1892, Wells became editor and co-owner of The Memphis Free Speech and Headlight. Here, she used her skills as a journalist to champion the causes for African American and women’s rights. Among her most known works were those on behalf of anti-lynching legislation. Until her death in 1931, Ida B. Wells dedicated her life to what she referred to as a “crusade for justice.”

- Unladylike: Examine the life and legacy of the health, labor, and immigrant rights reformer Grace Abbott in this resource from Unladylike2020. Born into a progressive family of abolitionists and suffragettes in Nebraska, Abbott made it her life’s work to help those in need—focusing on fighting for the rights of children, recent immigrants, and new mothers and their babies. Support materials include a digital short, vocabulary and discussion questions.

- PBS and DPLA: This collection uses primary sources to explore settlement houses during the Progressive Era. Digital Public Library of America Primary Source Sets are designed to help students develop their critical thinking skills and draw diverse material from libraries, archives, and museums across the United States. Each set includes an overview, ten to fifteen primary sources, links to related resources, and a teaching guide. These sets were created and reviewed by the teachers on the DPLA's Education Advisory Committee.

- Unladylike: Learn about Martha “Mattie” Hughes Cannon, an accomplished physician, suffragist, and the first woman state senator in the United States, elected in 1896 in the state of Utah. This digital short from Unladylike2020 features the story of an immigrant child from Wales, UK, who moved with her family at age 2 to Utah, became a physician, opened her own medical practice, married into a plural marriage, fled the country in exile, returned and then ran for state office—and won—when most women in the United States did not have the right to vote. In this resource, students explore the life and times of Hughes Cannon using video, discussion questions, and analysis of primary sources and informational texts to learn more about the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and how women’s roles evolved throughout its history.

- Unladylike: Williamina Fleming was a trailblazing astronomer and discoverer of hundreds of stars who paved the way for women in science. Learn about her contributions to the fields of astronomy and astrophysics with this digital short from Unladylike 2020. Support materials include discussion questions, vocabulary, and a quote analysis activity for students.

- Unladylike: Learn about the life and scientific achievements of botanist, explorer and environmentalist Ynés Mexía, in this digital short from Unladylike2020. Using video, discussion questions, classroom activities, and teaching tips, students learn about the historical period in which Mexía lived and her impact on science and the environmental movement.

- Unladylike: In this video from Unladylike2020, learn how Rose Schneiderman, an immigrant whose family settled in the tenements of New York City’s Lower East Side, became one of the most important labor leaders in American history. A socialist and feminist, she fought to end dangerous working conditions for garment workers, and worked to help New York State grant women the right to vote in 1917. Utilizing video, discussion questions, vocabulary, and teaching tips, students learn about Schneiderman’s role in creating a better life for workers in the United States. Sensitive: This resource contains material that may be sensitive for some students. Teachers should exercise discretion in evaluating whether this resource is suitable for their class.

- Unladylike: Tye Leung Schulze became the first Chinese American woman to work for the federal government and the first Chinese American woman to vote in a U.S. election, in 1912. Learn how this inspiring woman resisted domestic servitude and an arranged child marriage to provide translation services and solace to Asian immigrant victims of human trafficking in San Francisco in this video short from Unladylike2020. Sensitive: This resource contains material that may be sensitive for some students. Teachers should exercise discretion in evaluating whether this resource is suitable for their class.

- Unladylike: Learn about Mary Church Terrell, daughter of former slaves and one of the first African American women to earn both a Bachelor and a Master’s degree, who became a national leader for civil rights and women’s suffrage, in this video from Unladylike2020. Terrell was one of the earliest anti-lynching advocates and joined the suffrage movement, focusing her life’s work on racial uplift—the belief that blacks would end racial discrimination and advance themselves through education, work, and community activism. She helped found the National Association of Colored Women (NACW) and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Support materials include discussion questions and teaching tips for research projects. Primary source analysis activities emphasize how the content connects to racial justice issues that continue today, including a close reading of the Emmett Till Antilynching Bill of 2020. Sensitive: This resource contains material that may be sensitive for some students. Teachers should exercise discretion in evaluating whether this resource is suitable for their class.

- Unladylike: Learn about Maggie Lena Walker, the first African American woman to found a bank in the United States in this digital short from Unladylike2020. Utilizing a video, discussion questions and vocabulary, students will learn how Walker helped to improve the lives of African Americans and women at the turn of the 20th century by providing financial empowerment, social services, and civil rights leadership. Sensitive: This resource contains material that may be sensitive for some students. Teachers should exercise discretion in evaluating whether this resource is suitable for their class.

Female Relationships in the 19th century

Elizabeth Cady Stanton: Letter to Susan B. Anthony

In the 19th century, women spoke and wrote to each other much differently than they do today. Letters were more intimate in many ways and expressed love openly– this does not mean they were “in-love”-- or does it? Elizabeth Cady Stanton was a heterosexual woman in a lasting marriage. This is a letter she wrote to her fellow suffrage leader, Susan B. Anthony:

Dear Susan,

I wish that I were as free as you and I would stump the state in a twinkling. But I am not, and what is more, I passed through a terrible scourging when last at my father’s. I cannot tell you how deep the iron entered my soul. I never felt more keenly the degradation of my sex. To think that all in me which my father would have felt a proper pride had I been a man, is deeply mortifying to him because I am a woman.

That thought has stung me to a fierce decision—to speak as soon as I can do myself credit. But the pressure on me just now is too great. Henry sides with my friends, who oppose me in all that is dearest to my heart. They are not willing that I should write even on the woman question. But I will both write and speak. I wish you to consider this letter strictly confidential.

Sometimes, Susan, I struggle in deep waters…

As ever your friend, sincere and steadfast.

Stanton, Elizabeth Cady. Letter to Susan B. Anthony. Peterboro. September 10, 1855. Retrieved from “Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton: Their Words,” http://www.rochester.edu/sba/suffrage-history/susan-b-anthony-and-elizabeth-cady-stanton-their-words/.

Dear Susan,

I wish that I were as free as you and I would stump the state in a twinkling. But I am not, and what is more, I passed through a terrible scourging when last at my father’s. I cannot tell you how deep the iron entered my soul. I never felt more keenly the degradation of my sex. To think that all in me which my father would have felt a proper pride had I been a man, is deeply mortifying to him because I am a woman.

That thought has stung me to a fierce decision—to speak as soon as I can do myself credit. But the pressure on me just now is too great. Henry sides with my friends, who oppose me in all that is dearest to my heart. They are not willing that I should write even on the woman question. But I will both write and speak. I wish you to consider this letter strictly confidential.

Sometimes, Susan, I struggle in deep waters…

As ever your friend, sincere and steadfast.

Stanton, Elizabeth Cady. Letter to Susan B. Anthony. Peterboro. September 10, 1855. Retrieved from “Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton: Their Words,” http://www.rochester.edu/sba/suffrage-history/susan-b-anthony-and-elizabeth-cady-stanton-their-words/.

Katharine Lee Bates: If you Could Come

Katharine Lee Bates, the honored poet of the anthem, "America the Beautiful," wrote the above poem after the death of her lover, colleague, and partner of twenty-five years: Katharine Coman. In her grief over the loss of her friend, Bates wrote one of the most anguished memorials to the love and comradeship between two women that has ever been written; it was published in a limited edition as Yellow Clover: A Book of Remembrance. It is obvious from the yearning desire that glows throughout the poems in Yellow Clover, however, that the two women were more than just friends.

IF YOU COULD COME

My love, my love, if you could come once more

From your high place,

I would not question you for heavenly lore,

But, silent, take the comfort of your face.

I would not ask you if those golden spheres

In love rejoice,

If only our stained star hath sin and tears,

But fill my famished hearing with your voice.

One touch of you were worth a thousand creeds.

My wound is numb

Through toil-pressed day, but all night long it bleeds

In aching dreams, and still you cannot come.

Schwarz, Judith. “‘Yellow Clover’: Katharine Lee Bates and Katharine Coman.” Frontiers: A Journal of

Women Studies 4, no. 1 (1979): 59–67. https://doi.org/10.2307/3346671.

Bathes, Katharine Lee. Yellow clover; a book of remembrance. New York: E.P. Dutton & Company, 1922.

IF YOU COULD COME

My love, my love, if you could come once more

From your high place,

I would not question you for heavenly lore,

But, silent, take the comfort of your face.

I would not ask you if those golden spheres

In love rejoice,

If only our stained star hath sin and tears,

But fill my famished hearing with your voice.

One touch of you were worth a thousand creeds.

My wound is numb

Through toil-pressed day, but all night long it bleeds

In aching dreams, and still you cannot come.

Schwarz, Judith. “‘Yellow Clover’: Katharine Lee Bates and Katharine Coman.” Frontiers: A Journal of

Women Studies 4, no. 1 (1979): 59–67. https://doi.org/10.2307/3346671.

Bathes, Katharine Lee. Yellow clover; a book of remembrance. New York: E.P. Dutton & Company, 1922.

Mathilde Franziska Anneke and Mary Booth: Letters

Mathilde Franziska Anneke and Mary were married to men, but from 1860 to 1864 they lived together in Zürich, Switzerland with three of their children. They shared their money and the work of raising the children. There is no evidence that anyone questioned the propriety of their relationship, and Anneke’s daughter later insisted that it was not romantic, but their letters were very intense.

Mary Booth to Mathilde Franziska Anneke, Zürich, 1862

Pardon me, my Dear, for writing you such a miserable little note saying I was unhappy. I am indeed very happy when I think of your sweet love. It glorifies every even[ing] and illuminates the darkest midnights. You are the morning-star of my soul, the beautiful auroral glow of my heart, the saintly lily of my dream, the deep dark rose bud unfolding in my bosom day by day, sweetening my life with your etheriel fragrance – dearest, you are the reality of my dreams, my life, my Love – I have no more sorrow – I have You – My dear and dearest friend – good night

Your Mary

Mary Booth to Mathilde Franziska Anneke, Zürich, December 24, 1862

I have but one little thing,

Scarcely worth the offering,

Yet this little thing I hold,

Never could be bought for gold –

Not for all the pearls and gems

In the world’s bright diadems. –

Though it be of little worth

It is all I have on Earth.

It may not be found, or bought,

Yet I give it all unsought. –

Take – and lay it on the shelf –

For it only is – myself!

Efford, Alison Clark and Viktorija Bilic, editors. Radical Relationships: The Civil War–Era Correspondence of Mathilde Franziska Anneke. Translated by Viktorija Bilic. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2021. P. 155.

Mary Booth to Mathilde Franziska Anneke, Zürich, 1862

Pardon me, my Dear, for writing you such a miserable little note saying I was unhappy. I am indeed very happy when I think of your sweet love. It glorifies every even[ing] and illuminates the darkest midnights. You are the morning-star of my soul, the beautiful auroral glow of my heart, the saintly lily of my dream, the deep dark rose bud unfolding in my bosom day by day, sweetening my life with your etheriel fragrance – dearest, you are the reality of my dreams, my life, my Love – I have no more sorrow – I have You – My dear and dearest friend – good night

Your Mary

Mary Booth to Mathilde Franziska Anneke, Zürich, December 24, 1862

I have but one little thing,

Scarcely worth the offering,

Yet this little thing I hold,

Never could be bought for gold –

Not for all the pearls and gems

In the world’s bright diadems. –

Though it be of little worth

It is all I have on Earth.

It may not be found, or bought,

Yet I give it all unsought. –

Take – and lay it on the shelf –

For it only is – myself!

Efford, Alison Clark and Viktorija Bilic, editors. Radical Relationships: The Civil War–Era Correspondence of Mathilde Franziska Anneke. Translated by Viktorija Bilic. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2021. P. 155.

Tarbell vs. Rockefeller

Numerous: Clash of Titans

Tarbell

[Mr. Rockefeller] was no ordinary man. He had the powerful imagination to see what might be done with the oil business if it could be centered in his hands — the intelligence to analyze the problem into its elements and to find the key to control. He had the essential element to all great achievement, a steadfastness to a purpose once conceived which nothing can crush.

Mr. Rockefeller was "good." There was no more faithful Baptist in Cleveland than he. Every enterprise of that church he had supported liberally from his youth. He gave to its poor. He visited its sick. He wept for its suffering… Yet he was willing to strain every nerve to obtain for himself special and illegal privileges from the railroads which were bound to ruin every man in the oil business not sharing them with him. Religious emotion and sentiments of charity, propriety and self-denial seem to have taken the place in him of notions of justice and regard for the rights of others.

Tarbell, Ida. “The Rockefellers: Clash of Titans.” American Experience. PBS. Last modified 2020. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/rockefellers-clash/.

Rockefeller

This sweetness that she tries to bring in, referring to these good qualities, and this praise that she brings in as to ability and perseverance and whatever traits which she concedes bring success, is simply covering up her wrath and her jealousy which were all the time present, but which she did not show all the time and which she thought she could bring out all the better by weaving this in as silken thread.

She makes a pretence of fairness, of the judicial attitude, and beneath that pretence she slips into her 'history' all sorts of evil and prejudicial stuff, calling it 'the record of the court,' where it is only a statement by a party at interest, and she hides the other side. She is very adroit and cunning; but even she has defeated herself. She has over-reached herself, and anyone who reads her book with care can see that she is dishonest, prejudiced, untruthful.

Poor woman! How she has degraded herself and failed of accomplishing her object to injure, to smirch, to overthrow the Standard Oil Company, to satisfy the petty spite against it because forsooth her father and brother could not compete in the oil business.

Rockefeller, John D. “The Rockefellers: Clash of Titans.” American Experience. PBS. Last modified 2020. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/rockefellers-clash/.

Questions:

[Mr. Rockefeller] was no ordinary man. He had the powerful imagination to see what might be done with the oil business if it could be centered in his hands — the intelligence to analyze the problem into its elements and to find the key to control. He had the essential element to all great achievement, a steadfastness to a purpose once conceived which nothing can crush.

Mr. Rockefeller was "good." There was no more faithful Baptist in Cleveland than he. Every enterprise of that church he had supported liberally from his youth. He gave to its poor. He visited its sick. He wept for its suffering… Yet he was willing to strain every nerve to obtain for himself special and illegal privileges from the railroads which were bound to ruin every man in the oil business not sharing them with him. Religious emotion and sentiments of charity, propriety and self-denial seem to have taken the place in him of notions of justice and regard for the rights of others.

Tarbell, Ida. “The Rockefellers: Clash of Titans.” American Experience. PBS. Last modified 2020. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/rockefellers-clash/.

Rockefeller

This sweetness that she tries to bring in, referring to these good qualities, and this praise that she brings in as to ability and perseverance and whatever traits which she concedes bring success, is simply covering up her wrath and her jealousy which were all the time present, but which she did not show all the time and which she thought she could bring out all the better by weaving this in as silken thread.

She makes a pretence of fairness, of the judicial attitude, and beneath that pretence she slips into her 'history' all sorts of evil and prejudicial stuff, calling it 'the record of the court,' where it is only a statement by a party at interest, and she hides the other side. She is very adroit and cunning; but even she has defeated herself. She has over-reached herself, and anyone who reads her book with care can see that she is dishonest, prejudiced, untruthful.

Poor woman! How she has degraded herself and failed of accomplishing her object to injure, to smirch, to overthrow the Standard Oil Company, to satisfy the petty spite against it because forsooth her father and brother could not compete in the oil business.

Rockefeller, John D. “The Rockefellers: Clash of Titans.” American Experience. PBS. Last modified 2020. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/rockefellers-clash/.

Questions:

- What do these sources have against each other?

Numerous: The Cleveland Massacre

Tarbell

There were at the time some 26 refineries in [Cleveland], some of them very large plants. All of them were feeling more or less the discouraging effects of the last three or four years of railroad discriminations in favor of the Standard Oil Company. To the owners [of the 26 refineries] Mr. Rockefeller went one by one, and explained the South Improvement Company. "You see," he told them, "this scheme is bound to work. It means absolute control by us of the oil business…But we are going to give everybody a chance to come in. You are to turn over your refinery… and I will give you Standard Oil Company stock or cash."… It was useless to resist, he told the hesitating: they would certainly be crushed if they did not accept his offer, and he pointed out in detail, and with gentleness, how beneficent the scheme really was.

Tarbell, Ida. “The Rockefellers: Clash of Titans.” American Experience. PBS. Last modified 2020. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/rockefellers-clash/.

Rockefeller

I do not remember just how many [refineries] there were [in Cleveland] -- say 25 or 30, more or less. Some of them were very little. … More than 75, and probably more than 80 per cent -- certainly a great number -- of the refiners at Cleveland were already crushed by the competition which had been steadily increasing up to this time. … They didn't collapse. They had collapsed before. That's the reason they were so glad to combine their interest if they so wished it … [They were] mighty glad to get somebody to come and find a way out. We were taking all the risks, putting up our good money. They were putting in their old junk. … When it was found how much of stock or money would be given in exchange for their plants we found no difficulty in proceeding rapidly with the negotiations, and nearly all came in…

What I did say [to them] was: "We here [in Cleveland] are at a disadvantage. Something should be done for our mutual protection. We think this is a good scheme. Think it over. We would be glad to consider it with you if you are so inclined."

There was no compulsion, no pressure, no 'crushing'. How could our company succeed if its members had been forced to join it and were working under the dash?

Rockefeller, John D. “The Rockefellers: Clash of Titans.” American Experience. PBS. Last modified 2020. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/rockefellers-clash/.

Questions:

There were at the time some 26 refineries in [Cleveland], some of them very large plants. All of them were feeling more or less the discouraging effects of the last three or four years of railroad discriminations in favor of the Standard Oil Company. To the owners [of the 26 refineries] Mr. Rockefeller went one by one, and explained the South Improvement Company. "You see," he told them, "this scheme is bound to work. It means absolute control by us of the oil business…But we are going to give everybody a chance to come in. You are to turn over your refinery… and I will give you Standard Oil Company stock or cash."… It was useless to resist, he told the hesitating: they would certainly be crushed if they did not accept his offer, and he pointed out in detail, and with gentleness, how beneficent the scheme really was.

Tarbell, Ida. “The Rockefellers: Clash of Titans.” American Experience. PBS. Last modified 2020. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/rockefellers-clash/.

Rockefeller

I do not remember just how many [refineries] there were [in Cleveland] -- say 25 or 30, more or less. Some of them were very little. … More than 75, and probably more than 80 per cent -- certainly a great number -- of the refiners at Cleveland were already crushed by the competition which had been steadily increasing up to this time. … They didn't collapse. They had collapsed before. That's the reason they were so glad to combine their interest if they so wished it … [They were] mighty glad to get somebody to come and find a way out. We were taking all the risks, putting up our good money. They were putting in their old junk. … When it was found how much of stock or money would be given in exchange for their plants we found no difficulty in proceeding rapidly with the negotiations, and nearly all came in…

What I did say [to them] was: "We here [in Cleveland] are at a disadvantage. Something should be done for our mutual protection. We think this is a good scheme. Think it over. We would be glad to consider it with you if you are so inclined."

There was no compulsion, no pressure, no 'crushing'. How could our company succeed if its members had been forced to join it and were working under the dash?

Rockefeller, John D. “The Rockefellers: Clash of Titans.” American Experience. PBS. Last modified 2020. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/rockefellers-clash/.

Questions:

- What happened in Cleveland?

- Would you characterize it as a massacre?

Numerous: Legacy of Standard Oil

Rockefeller

The Standard Oil Co. has been one of the greatest, if not the greatest, of upbuilders we ever had in this country — or in any country. All of which has inured to the benefit of the towns and cities the country over; not only in our country but the world over. And that is a very pleasant reflection now as I look back. I knew it at the time, though I realize it more keenly now.

We had vision, saw the vast possibilities of the oil industry, stood at the center of it, and brought our knowledge and imagination and business experience to bear in a dozen — 20, 30 directions. There was no branch of the business in which we did not make money.

It will be said: "Here was a force that reorganized business, and everything else followed it — all business, even the Government itself, which legislated against it."

Rockefeller, John D. “The Rockefellers: Clash of Titans.” American Experience. PBS. Last modified 2020. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/rockefellers-clash/.

Tarbell

Mr. Rockefeller is a hypocrite. This man has for 40 years lent all the power of his great ability to perpetuating and elaborating a system of illegal and unjust discrimination by common carriers. He has done more than any other person to fasten on this country the most serious interference with free individual development which it suffers, an interference which, today, the whole country is struggling vainly to strike off, which it is doubtful will be cured, so deep-seated and so subtle is it, except by revolutionary methods.

It does not pay. Our national life is on every side distinctly poorer, uglier, meaner, for the kind of influence he exercises.

Tarbell, Ida. “The Rockefellers: Clash of Titans.” American Experience. PBS. Last modified 2020. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/rockefellers-clash/.

Questions:

The Standard Oil Co. has been one of the greatest, if not the greatest, of upbuilders we ever had in this country — or in any country. All of which has inured to the benefit of the towns and cities the country over; not only in our country but the world over. And that is a very pleasant reflection now as I look back. I knew it at the time, though I realize it more keenly now.

We had vision, saw the vast possibilities of the oil industry, stood at the center of it, and brought our knowledge and imagination and business experience to bear in a dozen — 20, 30 directions. There was no branch of the business in which we did not make money.

It will be said: "Here was a force that reorganized business, and everything else followed it — all business, even the Government itself, which legislated against it."

Rockefeller, John D. “The Rockefellers: Clash of Titans.” American Experience. PBS. Last modified 2020. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/rockefellers-clash/.

Tarbell

Mr. Rockefeller is a hypocrite. This man has for 40 years lent all the power of his great ability to perpetuating and elaborating a system of illegal and unjust discrimination by common carriers. He has done more than any other person to fasten on this country the most serious interference with free individual development which it suffers, an interference which, today, the whole country is struggling vainly to strike off, which it is doubtful will be cured, so deep-seated and so subtle is it, except by revolutionary methods.

It does not pay. Our national life is on every side distinctly poorer, uglier, meaner, for the kind of influence he exercises.

Tarbell, Ida. “The Rockefellers: Clash of Titans.” American Experience. PBS. Last modified 2020. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/rockefellers-clash/.

Questions:

- Do you think Rockefellers tactics were unjust? Why or why not?

Temperance and Intersectionality

Frances Willard: The Race Problem

As President of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, Frances Willard was known for her work to prevent the negative impact of alcohol on society, especially women and children, and her lifelong mission to advance women’s rights. In 1890, Frances Willard had traveled to Atlanta for a WCTU convention. While there, she gave an interview to a pro-prohibition newspaper, the New York Voice, about Southern politics. In the interview, Willard blamed black voters for the defeat of prohibition bills in the South, even though there was no evidence to suggest they were responsible. Below is a transcription of the article.

THE RACE PROBLEM.

MISS WILLARD ON THE POLITICAL PUZZLE OF THE SOUTH

"If I were Black and Young No Steamer Could Revolve Its Wheels Fast Enough to Convey Me to the Dark Continent" -Suffrage, With an Educational Qualification, Solves the Problem for the South

A reporter recently interviewed Miss Willard, with the following result. His question was: "What do you think of the race problem and the Force Bill?"

"I was born an abolitionist," said Miss Willard, "taught to read out of the 'Slave's Friend,' my father and mother were educated in Oberlin College. So far as I know, I have not an atom of race prejudice. With me the color of the heart and not the skin is what settles a human being's status. It seems to me that Africa, the youngest of the continents, will some day be the greatest. Centuries from now, the poetic, musical, kindly, institutional people may lead the civilization of the globe. If I were black and young, no steamer could revolve its wheels fast enough to convey me to the dark continent. I should go where my color was the correct thing, and leave these pale faces to work out their own destiny; and I should build in my life to make my color fashionable by as much as one owe individuality could do it. You know that matchless lecture of Wendell Philips on Toussaint L'Ouverture! Nothing in it was so inspiring to me as the climax with which he closes. I read it with tearful eyes when I was a farmer's daughter on the prairies. It is to be remembered that this great St. Dominican chief was of unmixed Negro blood. Such as he are prophecies. They only betoken what race shall yet become, even as a genius is but the beckoning hand and smiling face that points all her brothers and sisters onward, for a time shall come when every human being shall be a greater genius than any human being has yet been. Let me quote Wendell Phillips: "You think me a fanatic to-night, for you read history not with your eyes, but with your prejudices. But 50 years hence, when truth gets a hearing, the muse of history will put Phocion for the Greek, and Brutus for the Roman, Hamden for England, LaFayette for France, choose Washington as the bright, consumate flower of our earlier civilization, and John Brown as the ripe fruit of our noonday, then dipping her pen in the sunlight, will write in the clear blue, above them all, the name of the solider, the statesman, the martyr, Toussaint L'Ouverture!"

"Now as to the 'race problem' in its minified, current meaning. I am a true lover of the Southern people. Have spoken and worked in perhaps 200 of their towns and cities, have been taken into their love and confidence at scores of hospitable firesides. Have heard tham pour out their hearts in the splendid frankness of their impetuous natures; and I have said to them at such times, 'When I go North there will be no work wafted to you from pen or voice that is not loyal to what we are saying here and now.' Going South, a woman, a temperance woman -three great barriers to their good will yonder- I was received by them with a confidence that was one of the most delightful surprises of my life, I think we have wronged the South, though we did not mean to do so. The reason was, in part, that we had irreparably wronged ourselves by putting so safeguard on the ballot-box at the North that would sift out alien illiterates. They rule our cities to-day, the saloon is their palace, and the toddy stick their scepter. It is not fair that they should vote, nor is it fair that a plantation Negro, who can neither read, nor write, whose ideas are bounded by the fence of his own field and the price of his own mule, should be entrusted with the ballot. We ought to have put an educational test upon that ballot from the first. The Anglo-Saxon race will never submit to be dominated by the Negro so long as his aptitude reaches no higher than the personal liberty of the saloon and the power of appreciating the amount of liquor that a dollar will buy New England would no more submit to this than South Carolina. 'Better whiskey and more of it has been the rallying cry of great dark-faced mobs in the Southern localities where Local Option was snowed under by the colored vote, Temperance has no enemy like that, for it unreasoning and unreachable. To-night it promises in a great congregation, a vote for temperance at the polls to-morrow; but to-morrow twenty five cents changes that vote in favor of the liquor seller.

'I pity the Southerners; and I believe the great mass of them are as conscientious, and kindly-intentioned toward the colored man, as an equal member of white church members at the North. Would be demagogues lead the colored people to destruction. Half drunken white rouges murder them at the polls, or intimidate them so that they do not vote. But the better class of people must not be blamed for this, and a more thoroughly American population than the Christian people of the South does not exist. They have the traditions, the kindness, the probity, the courage of our forefathers, The problem on their hands is immeasurable. The colored race multiples like the locusts of Egypt. The grog shop is its center of power, The safety of woman, of childhood, of the home, in menaced in a thousand localities at this moment, so that men dare not go beyond the sight of their own roof-tree. How little we know of all this, seated in comfort and affluence here at the North, descanting upon the right of every man 'to cast one ballot and have it fairly counted,' that well-worn shibboleth invoked once more to dodge a living issue.