20. 1500-1700 Virgin Encounters in the New World

|

Women in the Americas saw their world altered dramatically as white men from Europe poured onto their shores. They lost their lives to European diseases, their customs, and became integrated into a new social structure, with indigenous people at the bottom. Despite all of that, some aspects of pre-contact life endured.

Trigger warning for discussion of sexual assault. |

Queen Isabella of Spain, Wikimedia Commons

Queen Isabella of Spain, Wikimedia Commons

When Columbus sailed the Atlantic and began lasting contact between the Americas and Afro-Eurasia, gender dynamics in the New World changed substantially. Indigenous societies including the Aztec and Incan empires, interacting with the Spanish patriarchies for the first time, changed considerably, according to the few surviving accounts of life before the Spanish and Portuguese. Spanish men explored and conquered the new world, but Indigenous women were present during all of those interactions.

First Contact

When the Spanish first arrived on the island of Hispaniola, originally called “Ay-ti” by the indigenous Taino population, they had positive interactions with the Native Americans there. Columbus wrote to his patron Queen Isabella and described their kindness and all of the gifts that they bestowed upon him. But then things changed, leading Isabella in her instructions to the Spanish to write, “Because we have been informed that some Christians in the above said islands, and especially in Hispaniola, have taken the Indians’ wives and other things from them against their will, you shall give orders, as soon as you arrive, that everything taken from the Indians against their will be returned . . . and if Spaniards should wish to marry Indian women, the marriages should be entered into willingly by both parties and not made by force.” Sadly, the need for this declaration gives us some insight into the ways that indigenous women of the Taino community were treated.

The mistreatment of the Taino on Hispaniola persisted. They were subjected to forced labor, raped, mutilated, and victimized by other horrific crimes. The Taino died en masse after being exposed to European diseases and subjected to horrific living conditions. In Haiti, Europeans pillaged native villages, taking women and children as slaves for labor and for sex.

First Contact

When the Spanish first arrived on the island of Hispaniola, originally called “Ay-ti” by the indigenous Taino population, they had positive interactions with the Native Americans there. Columbus wrote to his patron Queen Isabella and described their kindness and all of the gifts that they bestowed upon him. But then things changed, leading Isabella in her instructions to the Spanish to write, “Because we have been informed that some Christians in the above said islands, and especially in Hispaniola, have taken the Indians’ wives and other things from them against their will, you shall give orders, as soon as you arrive, that everything taken from the Indians against their will be returned . . . and if Spaniards should wish to marry Indian women, the marriages should be entered into willingly by both parties and not made by force.” Sadly, the need for this declaration gives us some insight into the ways that indigenous women of the Taino community were treated.

The mistreatment of the Taino on Hispaniola persisted. They were subjected to forced labor, raped, mutilated, and victimized by other horrific crimes. The Taino died en masse after being exposed to European diseases and subjected to horrific living conditions. In Haiti, Europeans pillaged native villages, taking women and children as slaves for labor and for sex.

Bartelome de la Casas, Wikimedia Commons

Bartelome de la Casas, Wikimedia Commons

Bartelome de la Casas

Bartelome de la Casas (1484-1556) was a Spanish priest who made several trips to the Americas in the 16th century, and came to abhor the treatment of the indigenous population he witnessed. He wrote that the Spanish had become conceited and mistreated the natives with growing contempt. He said they “thought nothing of knifing Indians by tens and twenties and of cutting slices off them to test the sharpness of their blades. He recorded his observations meticulously. He noted very different social norms as well as the freedom enjoyed by women with regard to control over their own bodies and relationships with men. He wrote: “Marriage laws are non-existent: men and women alike choose their mates and leave them as they please, without offense, jealousy or anger. They multiply in great abundance; pregnant women work to the last minute and give birth almost painlessly; up the next day, they bathe in the river and are as clean and healthy as before giving birth. If they tire of their men, they give themselves abortions with herbs that force stillbirths, covering their shameful parts with leaves or cotton cloth; although on the whole, Indian men and women look upon total nakedness with as much casualness as we look upon a man’s head or at his hands.”

The point of colonization was to find wealth and send it back to Europe. Thus, indigenous men, women, and children were forced to search for gold that the Spanish could bring back to their investors. The Spanish sought quick fortunes and violently used the indigenous people as a means to that end. La Casas described the toll this inflicted on women and their families. He said:

“Thus husbands and wives were together only once every eight or ten months and when they met they were so exhausted and depressed on both sides . . . they ceased to procreate. As for the newly born, they died early because their mothers, overworked and famished, had no milk to nurse them, and for this reason, while I was in Cuba, 7000 children died in three months. Some mothers even drowned their babies from sheer desperation. . . . In this way, husbands died in the mines, wives died at work, and children died from lack of milk . . . and in a short time this land which was so great, so powerful and fertile . . . was depopulated. . . . My eyes have seen these acts so foreign to human nature, and now I tremble as I write. . . . there were 60,000 people living on this island, including the Indians; so that from 1494 to 1508, over three million people had perished from war, slavery, and the mines. Who in future generations will believe this? I myself writing it as a knowledgeable eyewitness can hardly believe it...”

He took his case back to Spain to debate the treatment of indigenous people. The Valladolid Debate (1550-51) was a landmark debate about the rights and humanity of indigenous people living under colonial rule. The Spanish were found to have violated human decency in their treatment of the natives, but it did little to change what was happening an ocean away.

Bartelome de la Casas (1484-1556) was a Spanish priest who made several trips to the Americas in the 16th century, and came to abhor the treatment of the indigenous population he witnessed. He wrote that the Spanish had become conceited and mistreated the natives with growing contempt. He said they “thought nothing of knifing Indians by tens and twenties and of cutting slices off them to test the sharpness of their blades. He recorded his observations meticulously. He noted very different social norms as well as the freedom enjoyed by women with regard to control over their own bodies and relationships with men. He wrote: “Marriage laws are non-existent: men and women alike choose their mates and leave them as they please, without offense, jealousy or anger. They multiply in great abundance; pregnant women work to the last minute and give birth almost painlessly; up the next day, they bathe in the river and are as clean and healthy as before giving birth. If they tire of their men, they give themselves abortions with herbs that force stillbirths, covering their shameful parts with leaves or cotton cloth; although on the whole, Indian men and women look upon total nakedness with as much casualness as we look upon a man’s head or at his hands.”

The point of colonization was to find wealth and send it back to Europe. Thus, indigenous men, women, and children were forced to search for gold that the Spanish could bring back to their investors. The Spanish sought quick fortunes and violently used the indigenous people as a means to that end. La Casas described the toll this inflicted on women and their families. He said:

“Thus husbands and wives were together only once every eight or ten months and when they met they were so exhausted and depressed on both sides . . . they ceased to procreate. As for the newly born, they died early because their mothers, overworked and famished, had no milk to nurse them, and for this reason, while I was in Cuba, 7000 children died in three months. Some mothers even drowned their babies from sheer desperation. . . . In this way, husbands died in the mines, wives died at work, and children died from lack of milk . . . and in a short time this land which was so great, so powerful and fertile . . . was depopulated. . . . My eyes have seen these acts so foreign to human nature, and now I tremble as I write. . . . there were 60,000 people living on this island, including the Indians; so that from 1494 to 1508, over three million people had perished from war, slavery, and the mines. Who in future generations will believe this? I myself writing it as a knowledgeable eyewitness can hardly believe it...”

He took his case back to Spain to debate the treatment of indigenous people. The Valladolid Debate (1550-51) was a landmark debate about the rights and humanity of indigenous people living under colonial rule. The Spanish were found to have violated human decency in their treatment of the natives, but it did little to change what was happening an ocean away.

Gender Imbalance, Public Domain

Gender Imbalance, Public Domain

Gender Imbalance

In the Spanish and Portuguese colonies, there was a ratio of one European woman to every four European men. Spanish men ended up taking indigenous or African wives.

The conjugal relations between Spanish men and native women were rooted in the dynamics of colonialism: many of these relationships were coercive and involved rape, sexual assault, and domestic slavery. In other cases, native women attached themselves to European men in order to secure protection of their children and extended families from the ravages of colonialism.

A generation later, mixed-race relationships between Spanish men and Indian women resulted in a new class of people called the “Mestizos.” Eventually, this class of people would become the largest in Mexico, however the Spanish degraded the Mestizo class, regarding them as illegitimate citizens and subjects. Nonetheless, Mestizos and Mestizas enjoyed slightly better status than indigenous people. “Mestizas” served as domestic servants, worked in shops as retailers, and manufactured items like candles. Some of these women became very wealthy. An illiterate Mestiza named Mencia Perez was married and widowed twice to two wealthy Spanish men. She assumed responsibility for their businesses, becoming a very rich woman by the 1590s. But her story was an exception to the plight of most Mestizo women.

For women, conquest meant sexual violence and abuse. Rape was common as enslaved women worked under the authority of European men and were often forced to perform sexual acts.

In the Spanish and Portuguese colonies, there was a ratio of one European woman to every four European men. Spanish men ended up taking indigenous or African wives.

The conjugal relations between Spanish men and native women were rooted in the dynamics of colonialism: many of these relationships were coercive and involved rape, sexual assault, and domestic slavery. In other cases, native women attached themselves to European men in order to secure protection of their children and extended families from the ravages of colonialism.

A generation later, mixed-race relationships between Spanish men and Indian women resulted in a new class of people called the “Mestizos.” Eventually, this class of people would become the largest in Mexico, however the Spanish degraded the Mestizo class, regarding them as illegitimate citizens and subjects. Nonetheless, Mestizos and Mestizas enjoyed slightly better status than indigenous people. “Mestizas” served as domestic servants, worked in shops as retailers, and manufactured items like candles. Some of these women became very wealthy. An illiterate Mestiza named Mencia Perez was married and widowed twice to two wealthy Spanish men. She assumed responsibility for their businesses, becoming a very rich woman by the 1590s. But her story was an exception to the plight of most Mestizo women.

For women, conquest meant sexual violence and abuse. Rape was common as enslaved women worked under the authority of European men and were often forced to perform sexual acts.

Malinche, Wikimedia Commons

Malinche, Wikimedia Commons

Malintzin

Malinzin, or Malinche, was one of 20 female captives given by the Aztecs to the Spanish conquistador Heman Cortes as a gift. Her life exemplifies the contradictions of oppression experienced by young elite women. Like Pocahontas in Virginia, and Krotoa in the Dutch Cape Colony, she was born into an elite family and became a crucial mediator between the colonists and indigenous society. She was given as a gift precisely because of her status in her society, and was welcomed by Cortez because she provided access to Aztec society. She became Cortez‘s interpreter and was witness to his violent conquest of Mexico, which included deception and massacres of native people. The extent of her efforts and support for Cortés is questionable at best. For example, she supposedly warned the Spanish of an ambush she overhead being planned, leading the Spanish to massacre the people in question, but others say that she may have just been used by the Spanish as an excuse for their actions. We do know that she gave birth to Cortes’ first son, and thereby became a symbol of the American future, one forever influenced by Spain.

La Malinche was used as a propaganda tool for the Spanish who argued the indigenous peoples wanted their presence, while she is remembered in much of Latin History as a traitor. One version of her name became Mexican slang, “malinchista,” referring to someone who abandons their people for another.

We do not have records from her directly, which means she will remain a complicated figure in history. Nationalist history suggests she was a cunning girl who saw an opportunity out of slavery with the Spanish or that she was the traitor who turned on her people for her own gain. Newer scholarship suggests that as a woman with few options, she simply tried to to survive in a chaotic and cruel world. She was an enslaved woman who found a way to survive and achieve some form of agency; the Spanish remain the real culprit of the horrors experienced in Latin America.

Malinzin, or Malinche, was one of 20 female captives given by the Aztecs to the Spanish conquistador Heman Cortes as a gift. Her life exemplifies the contradictions of oppression experienced by young elite women. Like Pocahontas in Virginia, and Krotoa in the Dutch Cape Colony, she was born into an elite family and became a crucial mediator between the colonists and indigenous society. She was given as a gift precisely because of her status in her society, and was welcomed by Cortez because she provided access to Aztec society. She became Cortez‘s interpreter and was witness to his violent conquest of Mexico, which included deception and massacres of native people. The extent of her efforts and support for Cortés is questionable at best. For example, she supposedly warned the Spanish of an ambush she overhead being planned, leading the Spanish to massacre the people in question, but others say that she may have just been used by the Spanish as an excuse for their actions. We do know that she gave birth to Cortes’ first son, and thereby became a symbol of the American future, one forever influenced by Spain.

La Malinche was used as a propaganda tool for the Spanish who argued the indigenous peoples wanted their presence, while she is remembered in much of Latin History as a traitor. One version of her name became Mexican slang, “malinchista,” referring to someone who abandons their people for another.

We do not have records from her directly, which means she will remain a complicated figure in history. Nationalist history suggests she was a cunning girl who saw an opportunity out of slavery with the Spanish or that she was the traitor who turned on her people for her own gain. Newer scholarship suggests that as a woman with few options, she simply tried to to survive in a chaotic and cruel world. She was an enslaved woman who found a way to survive and achieve some form of agency; the Spanish remain the real culprit of the horrors experienced in Latin America.

Intermarriages, Wikimedia Commons

Intermarriages, Wikimedia Commons

Unmarried Spanish men in the new colonies were seen as a problem by the Spanish Crown, so by the mid 1500s, there was an effort to send more Spanish women to Mexico as wives. Later, the English colonies also dealt with a gender imbalance but actively worked to import more women as indentured servants and tobacco wives. Sometimes, women were even kidnapped off the streets.

Spanish women tended to marry older and wealthier men, which made widows common. In the Spanish empire, unlike the English, widows were allowed to inherit money easily. The presence of native women as domestic servants made life in the Spanish colonies for Spanish women enticing. Maria de Carranza encouraged her sister-in-law to come quickly saying, “[leave] the poverty and need which people suffer in Spain!”

Spanish women shared the privileges of their race with their husbands, but they were clearly subordinate to them because of their gender. Spanish women were barred from holding public office, viewed as weak, and in need of protection. They bore the Spanish legitimate children, the means for transmitting wealth and ensuring their legacy into future generations. This continued the Spanish legacy of focusing on “purity of blood“ seen previously in their liaisons with the Jews and Muslims under Isabella.

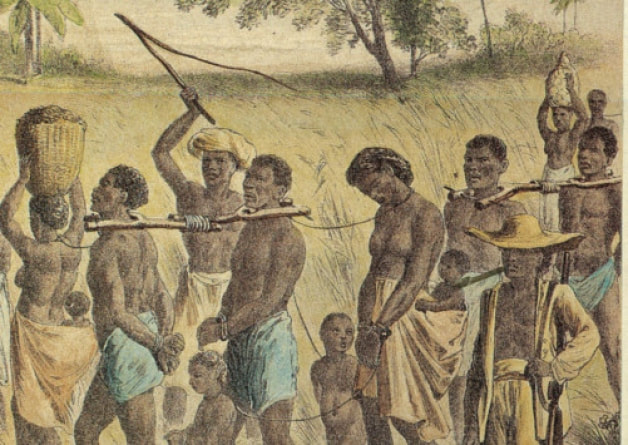

Mistreatment, murder, and diseases they didn’t have immunity to had a devastating impact on indigenous populations in the Americas. Some estimate that 90% of the population died. Aside from the horrific human cost, this presented an economic predicament for the colonists settling and establishing plantations. Who would help “civilize” and work the land? They sought enslaved people that were immune to these diseases and would therefore provide a more stable workforce. This led to the importation of African slaves and the growth of the transatlantic slave trade.

Spanish women tended to marry older and wealthier men, which made widows common. In the Spanish empire, unlike the English, widows were allowed to inherit money easily. The presence of native women as domestic servants made life in the Spanish colonies for Spanish women enticing. Maria de Carranza encouraged her sister-in-law to come quickly saying, “[leave] the poverty and need which people suffer in Spain!”

Spanish women shared the privileges of their race with their husbands, but they were clearly subordinate to them because of their gender. Spanish women were barred from holding public office, viewed as weak, and in need of protection. They bore the Spanish legitimate children, the means for transmitting wealth and ensuring their legacy into future generations. This continued the Spanish legacy of focusing on “purity of blood“ seen previously in their liaisons with the Jews and Muslims under Isabella.

Mistreatment, murder, and diseases they didn’t have immunity to had a devastating impact on indigenous populations in the Americas. Some estimate that 90% of the population died. Aside from the horrific human cost, this presented an economic predicament for the colonists settling and establishing plantations. Who would help “civilize” and work the land? They sought enslaved people that were immune to these diseases and would therefore provide a more stable workforce. This led to the importation of African slaves and the growth of the transatlantic slave trade.

Conclusion

Indigenous women lost so much. Disease decimated their communities, and colonial laws rendered them minors. They were increasingly excluded from the courts and colonial social systems. Their legal status made it difficult for them to maintain any property rights. Nevertheless these women persisted. Despite the colonial patriarchy imposed on them, Andean and Mayan women continued the tradition of leaving personal property to their female descendants.

As the transatlantic slave trade consolidated from the seventeenth century, the lives of indigenous people as well as enslaved became ever more connected, and women’s lives were fundamentally entangled with the various slave systems that emerged in the Americas.

Indigenous women lost so much. Disease decimated their communities, and colonial laws rendered them minors. They were increasingly excluded from the courts and colonial social systems. Their legal status made it difficult for them to maintain any property rights. Nevertheless these women persisted. Despite the colonial patriarchy imposed on them, Andean and Mayan women continued the tradition of leaving personal property to their female descendants.

As the transatlantic slave trade consolidated from the seventeenth century, the lives of indigenous people as well as enslaved became ever more connected, and women’s lives were fundamentally entangled with the various slave systems that emerged in the Americas.

Draw your own conclusions

|

Learn how to teach with inquiry.

Many of these lesson plans were sponsored in part by the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources Eastern Region Program, coordinated by Waynesburg University, the History and Social Studies Education Faculty at Plymouth State University, and the Patrons of the Remedial Herstory Project. |

Lesson Plans from Other Organizations

- This website, Women in World History has primary source based lesson plans on women's history in a whole range of topics. Some are free while others have a cost.

- The Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media has produced recommendations for teaching women's history with primary sources and provided a collection of sources for world history. Check them out!

- The Stanford History Education Group has a number of lesson plans about women in World History.

Coming Soon...

Remedial Herstory Editors. "20. 1500-1600 VIRGIN ENCOUNTERS IN THE NEW WORLD." The Remedial Herstory Project. November 1, 2022. www.remedialherstory.com.

Primary AUTHOR: |

Kelsie Brook Eckert

|

Primary Reviewer: |

Jacqui Nelson

|

Consulting Team |

Editors |

|

Kelsie Brook Eckert, Project Director

Coordinator of Social Studies Education at Plymouth State University Dr. Nancy Locklin-Sofer, Consultant Professor of History at Maryville College. Chloe Gardner, Consultant PhD Candidate in Religious Studies at Edinburgh University Dr. Whitney Howarth, Consultant Former Professor of History at Plymouth State University Jacqui Nelson, Consultant Teaching Lecturer of Military History at Plymouth State University Maria Concepcion Marquez Sandoval PhD Candidate in History at Arizona University |

Amy Flanders

Humanities Teacher, Moultonborough Academy ReviewersAncient:

Dr. Kristin Heineman Professor of History at Colorado State University Dr. Bonnie Rock-McCutcheon Professor of History at Wilson College Sarah Stone PhD Candidate in Religious Studies at Edinburgh University Medieval: Dr. Katherine Koh Professor of History at La Sierra University Dr. Jonathan Couser Professor of History at Plymouth State University Dr. Shahla Haeri Professor of History at Boston University Lauren Cole PhD Candidate in History at Northwestern University Modern: Dr. Barbara Tischler Supervisor for Hunter College Dr. Pamela Scully Professor of Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies and African Studies at Emory University |

|

When black women were brought from Africa to the New World as slave laborers, their value was determined by their ability to work as well as their potential to bear children, who by law would become the enslaved property of the mother's master. In Laboring Women: Reproduction and Gender in New World Slavery, Jennifer L. Morgan examines for the first time how African women's labor in both senses became intertwined in the English colonies. Beginning with the ideological foundations of racial slavery in early modern Europe, Laboring Women traverses the Atlantic, exploring the social and cultural lives of women in West Africa, slaveowners' expectations for reproductive labor, and women's lives as workers and mothers under colonial slavery.

Women, Witchcraft, and the Inquisition in Spain and the New World investigates the mystery and unease surrounding the issue of women called before the Inquisition in Spain and its colonial territories in the Americas, including Mexico and Cartagena de Indias. Edited by María Jesús Zamora Calvo, this collection gathers innovative scholarship that considers how the Holy Office of the Inquisition functioned as a closed, secret world defined by patriarchal hierarchy and grounded in misogynistic standards.

Women in Early America: Struggle, Survival, and Freedom in a New World provides insight into an era in American history when women had immense responsibilities and unusual freedoms. These women worked in a range of occupations such as tavernkeeping, printing, spiritual leadership, trading, and shopkeeping. Pipe smoking, beer drinking, and premarital sex were widespread. One of every eight people traveling with the British Army during the American Revolution was a woman.

Through powerful stories that place the reader on the ground in plantation-era Jamaica, Contested Bodies reveals enslaved women's contrasting ideas about maternity and raising children, which put them at odds not only with their owners but sometimes with abolitionists and enslaved men. Turner argues that, as the source of new labor, these women created rituals, customs, and relationships around pregnancy, childbirth, and childrearing that enabled them at times to dictate the nature and pace of their work as well as their value.

|

|

|

Sixteen-year-old Kit Tyler is marked by suspicion and disapproval from the moment she arrives on the unfamiliar shores of colonial Connecticut in 1687. Alone and desperate, she has been forced to leave her beloved home on the island of Barbados and join a family she has never met. Torn between her quest for belonging and her desire to be true to herself, Kit struggles to survive in a hostile place. Just when it seems she must give up, she finds a kindred spirit. But Kit’s friendship with Hannah Tupper, believed by the colonists to be a witch, proves more taboo than she could have imagined and ultimately forces Kit to choose between her heart and her duty.

Stuart Stirling tells the history of the Inca princesses and of their conquistador lovers and descendants. The story begins with the early days of Pizarro's conquest at Cajamarca in the 1530s, when the emperor Atahualpa gifted his young sister wife Quispe Sis Huaylas to Pizarro. This was the beginning of the distribution and rape of the princesses among the conquistadors - a practice which was in many ways a distillation of the tragedy of the Spanish colonization of the Americas. The detailed human stories of the princesses bring to life the world of the Incas and their conquerors and shed new light on the darker corners of colonial history.

|

|

How to teach with films:

Remember, teachers want the student to be the historian. What do historians do when they watch films?

- Before they watch, ask students to research the director and producers. These are the source of the information. How will their background and experience likely bias this film?

- Also, ask students to consider the context the film was created in. The film may be about history, but it was made recently. What was going on the year the film was made that could bias the film? In particular, how do you think the gains of feminism will impact the portrayal of the female characters?

- As they watch, ask students to research the historical accuracy of the film. What do online sources say about what the film gets right or wrong?

- Afterward, ask students to describe how the female characters were portrayed and what lessons they got from the film.

- Then, ask students to evaluate this film as a learning tool. Was it helpful to better understand this topic? Did the historical inaccuracies make it unhelpful? Make it clear any informed opinion is valid.

|

Elizabeth tells the story of Elizabeth's Golden era.

IMDB |

|

|

Mary Queen of Scots is a film about the relationship between the Protestant Queen Elizabeth I of England and her Catholic cousin Mary Queen of Scots who challenged her throne.

IMDB |

|

BIBLIOGRAPHY

DuBois, Ellen Carol, 1947-. Through Women's Eyes : an American History with Documents. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's, 2005.

Miles, Rosalind. The Women’s History of the World. London, UK: HarperCollins Publishers, 1988.

Scully, Pamela. "Malintzin, Pocahontas, and Krotoa: indigenous women and myth models of the Atlantic world." Journal of Colonialism and Colonial History 6, no. 3 (20

Strayer, R. and Nelson, E., Ways Of The World. 3rd ed. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2016.

Miles, Rosalind. The Women’s History of the World. London, UK: HarperCollins Publishers, 1988.

Scully, Pamela. "Malintzin, Pocahontas, and Krotoa: indigenous women and myth models of the Atlantic world." Journal of Colonialism and Colonial History 6, no. 3 (20

Strayer, R. and Nelson, E., Ways Of The World. 3rd ed. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2016.