19. Women and World War II

|

Women in World War II, again, entered new fields. They became members of the military, and even faced combat. Took over their families, became correspondents, spies, and code breakers. The war created a time for women to branch out but still many struggled financially or were prevented, from things such as racism, to grow.

|

Martha Gellhorn, The New Yorker

Martha Gellhorn, The New Yorker

Wartime is often regarded as the province of men. But contrary to popular belief, women don’t disappear during war. During World War II, American women’s individual and collective contributions to the war effort, at home and at the front, proved essential to victory.

After World War I, the US experienced the Roaring Twenties followed by the Great Depression. Then, the world was at war again. Nazi German troops were annexing plenty of nearby land. When they invaded Poland with the help of the Soviets, the old allies of WWI had had enough. Germany’s neighbors quickly fell to the Blitzkrieg. Blitzkrieg was a lighting war strategy that caused much of Europe to fall under occupation.

Before the War:

The US, sheltered by the Atlantic and the Pacific, stayed out of the war despite cries from Europe for support. European nobility Princess Märtha of Sweden even came to live in the states with her children and regularly appealed to her new friends President Franklin Roosevelt and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, to take up Norway's cause. She urged them to provide Norway with war materials, and return her family to their home. But Roosevelt was in a political pickle, and kept the US out of the war.

Meanwhile, women war correspondents reported the situation to the American public. Martha Gellhorn, Josephine Herbst, and Frances Davis were among the women who told the story of the war to an international audience. They faced the discrimination common to women reporters--they were often ignored by the men. Davis observed that, “Somewhere within me there is the cloud of discomfort at being where I am not wanted.” She eventually won over her male colleagues…by smuggling their stories to France in her underwear.

After World War I, the US experienced the Roaring Twenties followed by the Great Depression. Then, the world was at war again. Nazi German troops were annexing plenty of nearby land. When they invaded Poland with the help of the Soviets, the old allies of WWI had had enough. Germany’s neighbors quickly fell to the Blitzkrieg. Blitzkrieg was a lighting war strategy that caused much of Europe to fall under occupation.

Before the War:

The US, sheltered by the Atlantic and the Pacific, stayed out of the war despite cries from Europe for support. European nobility Princess Märtha of Sweden even came to live in the states with her children and regularly appealed to her new friends President Franklin Roosevelt and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, to take up Norway's cause. She urged them to provide Norway with war materials, and return her family to their home. But Roosevelt was in a political pickle, and kept the US out of the war.

Meanwhile, women war correspondents reported the situation to the American public. Martha Gellhorn, Josephine Herbst, and Frances Davis were among the women who told the story of the war to an international audience. They faced the discrimination common to women reporters--they were often ignored by the men. Davis observed that, “Somewhere within me there is the cloud of discomfort at being where I am not wanted.” She eventually won over her male colleagues…by smuggling their stories to France in her underwear.

Eleanor Roosevelt, Library of Congress

Eleanor Roosevelt, Library of Congress

Back to Eleanor Roosevelt, who was privy to immense knowledge about the situation in Europe. In May 1939, more than 900 Jews fled Germany aboard a ship bound for the US, but were turned away and forced to return to Europe, where, tragically, more than 250 were killed by the Nazis. A year later when another ship of Jewish refugees docked in New York, they sent a telegram directly to the First Lady begging for support. Eleanor answered the call, took the Secretary of State to court, and saved the lives of 81 refugees seeking asylum.

Eleanor Roosevelt’s efforts were technically against the political will of the American public who wanted to limit immigration and stay out of war. But on December 7th, 1941, public opinion changed after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor in Hawaii and other Pacific island sites.

Roosevelt had started a column, My Day, to help Americans through the Depression. The day after Pearl Harbor Eleanor wrote, “Our people had been killed not suspecting there was an enemy, who attacked in the usual ruthless way which Hitler has prepared us to suspect. None of us can help but regret the choice which Japan has made, but having made it, she has taken on a coalition of enemies she must underestimate; unless she believes we have sadly deteriorated since our first ships sailed into her harbor.”

Eleanor Roosevelt’s efforts were technically against the political will of the American public who wanted to limit immigration and stay out of war. But on December 7th, 1941, public opinion changed after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor in Hawaii and other Pacific island sites.

Roosevelt had started a column, My Day, to help Americans through the Depression. The day after Pearl Harbor Eleanor wrote, “Our people had been killed not suspecting there was an enemy, who attacked in the usual ruthless way which Hitler has prepared us to suspect. None of us can help but regret the choice which Japan has made, but having made it, she has taken on a coalition of enemies she must underestimate; unless she believes we have sadly deteriorated since our first ships sailed into her harbor.”

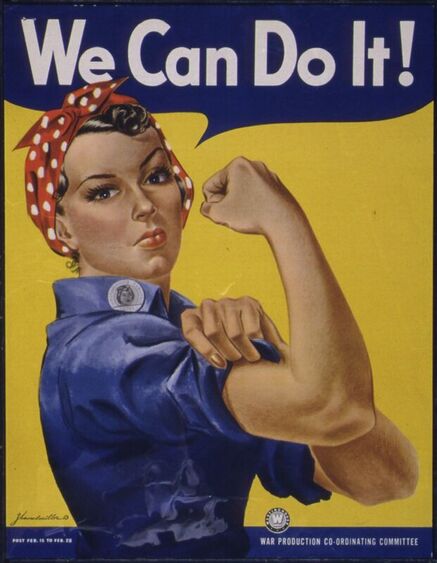

Rosie the Riveter, Library of Congress

Rosie the Riveter, Library of Congress

Rosie the Riveter:

Women had long been laboring outside the home in “gendered” jobs. As war production increased and men volunteered or were drafted into the military, factories needed women workers to shift industries and fill positions making tanks, jeeps, planes, and munitions. The symbol of “Rosie the Riveter” came to represent the woman who left the domestic sphere to support the war effort. Rosie was even the subject of a popular song in 1942.

Rosie was often portrayed as white, but in reality, a lot of Rosies were poor women of color. In fact 40 percent of Black women in America were already in the workforce, compared to only 25 percent of white women. Women of color made less than white women, who then made less than men. In wartime Black women finally had opportunities for new types of jobs with better pay. For most white women, the war inspired them to leave their traditional home life to learn new skills, do their patriotic duty, and earn a paycheck. Rosie the Riveter became a feminist symbol of women’s competence, independence, and disrupting traditional gender roles.

Hortense Johnson, a Black Rosie wrote, “Of course I’m vital to victory, just as millions of men and women who are fighting to save America’s chances for Democracy, even if they never shoulder a gun… I am an inspector in a war plant… When we approve them they are ready to be… headaches for Hitler or Hirohito.”

Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins, the first woman ever to hold a cabinet position, was instrumental in encouraging major manufacturers to hire women in defense industries. She importantly expressed the hope that the advances made by women in the workforce would continue after the war.

Women had long been laboring outside the home in “gendered” jobs. As war production increased and men volunteered or were drafted into the military, factories needed women workers to shift industries and fill positions making tanks, jeeps, planes, and munitions. The symbol of “Rosie the Riveter” came to represent the woman who left the domestic sphere to support the war effort. Rosie was even the subject of a popular song in 1942.

Rosie was often portrayed as white, but in reality, a lot of Rosies were poor women of color. In fact 40 percent of Black women in America were already in the workforce, compared to only 25 percent of white women. Women of color made less than white women, who then made less than men. In wartime Black women finally had opportunities for new types of jobs with better pay. For most white women, the war inspired them to leave their traditional home life to learn new skills, do their patriotic duty, and earn a paycheck. Rosie the Riveter became a feminist symbol of women’s competence, independence, and disrupting traditional gender roles.

Hortense Johnson, a Black Rosie wrote, “Of course I’m vital to victory, just as millions of men and women who are fighting to save America’s chances for Democracy, even if they never shoulder a gun… I am an inspector in a war plant… When we approve them they are ready to be… headaches for Hitler or Hirohito.”

Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins, the first woman ever to hold a cabinet position, was instrumental in encouraging major manufacturers to hire women in defense industries. She importantly expressed the hope that the advances made by women in the workforce would continue after the war.

Japanese American children at an internment camp in California, Library of Congress

Japanese American children at an internment camp in California, Library of Congress

Japanese American Internment:

After the Pearl Harbor attack, more than 110,000 people of Japanese descent were removed from their homes and forced to live in internment camps in remote areas of the United States. Executive Order 9066 was a response to fears on the west coast that Japanese Americans, even those who were born in the United States, maintained a primary allegiance to Japan. These families were given very little time to settle their affairs or pack before their confinement began. Many were sent to initial staging locations–like fairgrounds or horse racing tracks–where they were sometimes forced to stay for weeks before being sent to their assigned internment camp. In the camps, women got to work. They served as teachers, nurses, and organizers who did everything in their power to establish supportive communities. Their roles were domestic and maternal, but they were essential to the survival of the deportees.

Sadly, most Americans were essentially blind to the hypocrisy of fighting for democracy while fellow Americans were in camps. They went on with war life. Besides joining the job force, American women learned new skills and assumed typically “male” roles in society. They learned to drive, manage household finances, did home repairs, and in New Orleans even became street car “conductresses.” Women wrote letters to men serving overseas to provide glimpses of home. They grew victory gardens to feed their families, as basic necessities such as gasoline, coffee, sugar, butter, rubber, and canned milk were rationed. Women even gave up wearing silk stockings because that valuable fabric was used to manufacture parachutes. The slogan “Use it up-Wear it out-Make it do-or Do without” inspired creative solutions to the challenge of wartime shortages.

After the Pearl Harbor attack, more than 110,000 people of Japanese descent were removed from their homes and forced to live in internment camps in remote areas of the United States. Executive Order 9066 was a response to fears on the west coast that Japanese Americans, even those who were born in the United States, maintained a primary allegiance to Japan. These families were given very little time to settle their affairs or pack before their confinement began. Many were sent to initial staging locations–like fairgrounds or horse racing tracks–where they were sometimes forced to stay for weeks before being sent to their assigned internment camp. In the camps, women got to work. They served as teachers, nurses, and organizers who did everything in their power to establish supportive communities. Their roles were domestic and maternal, but they were essential to the survival of the deportees.

Sadly, most Americans were essentially blind to the hypocrisy of fighting for democracy while fellow Americans were in camps. They went on with war life. Besides joining the job force, American women learned new skills and assumed typically “male” roles in society. They learned to drive, manage household finances, did home repairs, and in New Orleans even became street car “conductresses.” Women wrote letters to men serving overseas to provide glimpses of home. They grew victory gardens to feed their families, as basic necessities such as gasoline, coffee, sugar, butter, rubber, and canned milk were rationed. Women even gave up wearing silk stockings because that valuable fabric was used to manufacture parachutes. The slogan “Use it up-Wear it out-Make it do-or Do without” inspired creative solutions to the challenge of wartime shortages.

All American Girls Professional Baseball League, Library of Congress

All American Girls Professional Baseball League, Library of Congress

All-American Girls Professional Baseball League:

With the departure of many Major League Baseball players for the front lines, Chicago Cubs owner Philip K. Wrigley organized the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League. The League began play in 1943 with four teams. It expanded to ten teams and nearly six hundred players in its twelve-year tenure. The women played to enthusiastic crowds throughout the Midwest. Although the women were professional athletes, they were expected to maintain a “feminine” image that included dress uniforms, making it difficult to slide into a base while maintaining one’s modesty or avoiding scraped legs. Despite poor pay and long bus travel, the “girls” provided popular entertainment. They saw their job as a positive aspect of the war effort and laid the groundwork for women's sports and Title IX of the future.

Women’s Service Branches:

But women weren’t just serving on the home and job fronts. Nearly three million women volunteered with the Red Cross in the US and abroad. They delivered packages of needed supplies to civilians in Europe as early as 1939, established a blood donor service that provided plasma for wounded soldiers, and even drove ambulances.

With the departure of many Major League Baseball players for the front lines, Chicago Cubs owner Philip K. Wrigley organized the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League. The League began play in 1943 with four teams. It expanded to ten teams and nearly six hundred players in its twelve-year tenure. The women played to enthusiastic crowds throughout the Midwest. Although the women were professional athletes, they were expected to maintain a “feminine” image that included dress uniforms, making it difficult to slide into a base while maintaining one’s modesty or avoiding scraped legs. Despite poor pay and long bus travel, the “girls” provided popular entertainment. They saw their job as a positive aspect of the war effort and laid the groundwork for women's sports and Title IX of the future.

Women’s Service Branches:

But women weren’t just serving on the home and job fronts. Nearly three million women volunteered with the Red Cross in the US and abroad. They delivered packages of needed supplies to civilians in Europe as early as 1939, established a blood donor service that provided plasma for wounded soldiers, and even drove ambulances.

Friedman, PBS

Friedman, PBS

More than any war before, women were mobilized in the combat effort. One of the first ways they were used were as code breakers. Elizebeth Smith Friedman (1892–1980) cracked hundreds of ciphers during her career as America’s first female cryptanalyst. She was well known for her service in WWI and busting smugglers during Prohibition. Though she and her husband both worked as contractors in intelligence, she earned half her husband’s pay for the same work. After Pearl Harbor the Navy took over Friedman’s unit and demoted her.

Friedman did not let the sexism and setbacks stop her. She and her team used analog methods (that means pen and paper) to break three separate Enigma machine codes. One year after Pearl Harbor, her team had cracked every one of the Nazi’s new codes. In March of 1942, she made an amazing discovery. She decoded messages that indicated the Nazis had located the Queen Mary carrying 8,000 soldiers off the coast of Brazil, and they were preparing to sink it. Friedman’s decoding success allowed the Queen Mary to evade German submarines and sail to safety.

Besides Friedman, 10,000 American women codebreakers managed the conveyor belt of wartime communications and intercepts from the Axis Powers. They were pulled from schools as teachers, found in colleges as math majors, or discovered through newspaper advertisements for crossword puzzles. Their work was instrumental in winning key naval battles and gunning down the plane of Isoroku Yamamoto, the architect of Pearl Harbor. They embodied patriotism and determination.

Historian Liza Mundy claims, "The recruitment of these American women—and the fact that women were behind some of the most significant individual code-breaking triumphs of the war—was one of the best-kept secrets of the conflict.”

Friedman did not let the sexism and setbacks stop her. She and her team used analog methods (that means pen and paper) to break three separate Enigma machine codes. One year after Pearl Harbor, her team had cracked every one of the Nazi’s new codes. In March of 1942, she made an amazing discovery. She decoded messages that indicated the Nazis had located the Queen Mary carrying 8,000 soldiers off the coast of Brazil, and they were preparing to sink it. Friedman’s decoding success allowed the Queen Mary to evade German submarines and sail to safety.

Besides Friedman, 10,000 American women codebreakers managed the conveyor belt of wartime communications and intercepts from the Axis Powers. They were pulled from schools as teachers, found in colleges as math majors, or discovered through newspaper advertisements for crossword puzzles. Their work was instrumental in winning key naval battles and gunning down the plane of Isoroku Yamamoto, the architect of Pearl Harbor. They embodied patriotism and determination.

Historian Liza Mundy claims, "The recruitment of these American women—and the fact that women were behind some of the most significant individual code-breaking triumphs of the war—was one of the best-kept secrets of the conflict.”

WASPS, NPR

WASPS, NPR

Women code breakers and their unbelievable value to the war effort opened the doors for women across the armed forces. First, Edith Nourse Rogers pressed Congress to create the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps, nicknamed the WACs in 1942. Women rushed to enlist and be of service. More than 300,000 women volunteered.

Women led many clerical tasks, rigged parachutes, and maintained aircraft and military vehicles. The symbol of the WACs was Pallas Athena, the ancient goddess of industries of peace and arts of war. She was also the goddess of storms and battle.

Shortly after WACs was established, the Navy began recruiting women into their own brace–the WAVES.

The Marine Corps and Coast Guard had a Women’s Reserve, and the budding civilian air force added a branch of Women Airforce Service Pilots (or WASPS) in 1947. They flew B-26 and B-29 planes on pre-combat flights.

Women led many clerical tasks, rigged parachutes, and maintained aircraft and military vehicles. The symbol of the WACs was Pallas Athena, the ancient goddess of industries of peace and arts of war. She was also the goddess of storms and battle.

Shortly after WACs was established, the Navy began recruiting women into their own brace–the WAVES.

The Marine Corps and Coast Guard had a Women’s Reserve, and the budding civilian air force added a branch of Women Airforce Service Pilots (or WASPS) in 1947. They flew B-26 and B-29 planes on pre-combat flights.

Virginia Hall, ABOTA

Virginia Hall, ABOTA

But while the gender barrier was opening, the racial barrier persisted. Black women in these branches were often relegated to low-skill assignments or segregated entirely. Tina Hill, an aircraft worker, said, “I could see where they made a difference in placing you in certain jobs… all the negroes went to Department 17 because there was nothing but shooting and bucketing rivets… I just didn’t like it… [Negroes] fought hand, tooth, and nail to get in[to better work]... they were educated, but they started them off as janitors… they had to start fighting all over again to get off that broom and get something decent.” Worse, if Black women challenged their treatment, they were sometimes court martialed. The brewing hypocrisy of patriotism and racism is part of what led to the Civil Rights Movement following the war.

Indigenous women volunteered and participated in the war effort as well. In terms of the WAC and WASP, some 800 women answered the call to serve and did so in a variety of roles. For instance, Grace Thorpe of the Sac and Fox people was initially a WAC recruiter before being transferred to New Guinea where she would later earn a Bronze Star (and later Congressional recognition) for service during battle. Towards the end of the war, she also worked in the headquarters of General MacArthur (pictured above). Like many other women, those of Indigenous descent also played an active role on the home front. In Wisconsin, for instance, Menominee women worked in sawmills. Elsewhere, Indigenous women also joined domestic defense units; one even remarked: “We have rifles, we have ammunition, and we know how to shoot.”

Some women possessed exceptional skills that were, frankly, exploited for the war effort. Virginia Hall was an American woman who lost her leg to gangrene in a hunting accident. She was fluent in French, having studied abroad and determined to be of service…but she was relegated to a desk. Defiantly, she volunteered to drive ambulances for the French army on the front line during the Nazi invasion of 1940. When France fell, she offered her services to the British in London. While the Allies were not keen on employing women, months of trying to infiltrate the Nazis with spies had failed. Ironically, Prime Minister Winston Churchill branded his emerging spy network as “ungentlemanly” warfare. Hall was recruited by Vera Atkins, a British intelligence officer keen on getting women into France. She knew since France fell, the countryside was mostly female, so a male spy would stick out.

Hall was dropped into France to operate a radio and pass messages back to the Allies. She helped the British land planes and supplied the French resistance in preparation for D-Day. When American boys landed, there would be an armed and ready French population waiting to help. Hall emerged as a dauntless guerrilla leader. She blew up bridges and attacked German convoys.

She was rewarded by becoming the only civilian woman of the war to be decorated with the Distinguished Service Cross for “extraordinary heroism.” CIA officers continue–to this day–to use her techniques developed in France.

Indigenous women volunteered and participated in the war effort as well. In terms of the WAC and WASP, some 800 women answered the call to serve and did so in a variety of roles. For instance, Grace Thorpe of the Sac and Fox people was initially a WAC recruiter before being transferred to New Guinea where she would later earn a Bronze Star (and later Congressional recognition) for service during battle. Towards the end of the war, she also worked in the headquarters of General MacArthur (pictured above). Like many other women, those of Indigenous descent also played an active role on the home front. In Wisconsin, for instance, Menominee women worked in sawmills. Elsewhere, Indigenous women also joined domestic defense units; one even remarked: “We have rifles, we have ammunition, and we know how to shoot.”

Some women possessed exceptional skills that were, frankly, exploited for the war effort. Virginia Hall was an American woman who lost her leg to gangrene in a hunting accident. She was fluent in French, having studied abroad and determined to be of service…but she was relegated to a desk. Defiantly, she volunteered to drive ambulances for the French army on the front line during the Nazi invasion of 1940. When France fell, she offered her services to the British in London. While the Allies were not keen on employing women, months of trying to infiltrate the Nazis with spies had failed. Ironically, Prime Minister Winston Churchill branded his emerging spy network as “ungentlemanly” warfare. Hall was recruited by Vera Atkins, a British intelligence officer keen on getting women into France. She knew since France fell, the countryside was mostly female, so a male spy would stick out.

Hall was dropped into France to operate a radio and pass messages back to the Allies. She helped the British land planes and supplied the French resistance in preparation for D-Day. When American boys landed, there would be an armed and ready French population waiting to help. Hall emerged as a dauntless guerrilla leader. She blew up bridges and attacked German convoys.

She was rewarded by becoming the only civilian woman of the war to be decorated with the Distinguished Service Cross for “extraordinary heroism.” CIA officers continue–to this day–to use her techniques developed in France.

Martha Gelhorn, WWII

Martha Gelhorn, WWII

When Americans finally landed on mainland Europe on June 6, 1944, no women were allowed. However, Martha Gelhorn, a journalist, stowed away on a ship because all the male journalists were going and she was not going to be excluded. Her account of D-Day is raw and was widely read. Nevertheless, she was found out and sent back to Britain to sit in military prison for defying orders. Gelhorn escaped and flew to Italy to cover the remainder of the war.

Eleanor Roosevelt addressed the nation about D-Day saying, “ The best way in which we can help is by doing our jobs here better than ever before, no matter what these jobs may be.”

It would take a year for the Allies to take Berlin. Unfortunately, the Soviet Union would get there first, with soldiers raping and pillaging German cities as they went.

Women in the Manhattan Project:

Back in the US, women scientists helped win the war for the Allies. Leona Woods Marshall worked on Enrico Fermi’s Manhattan Project team that created a self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction at the University of Chicago. Think of how complicated it was to make. Her contributions were overlooked when Fermi received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry, but another woman scientist, Maria Goepert Mayer, did earn a Nobel prize for her work in nuclear physics. Both women’s work was key to the development of the atomic bomb.

Eleanor Roosevelt addressed the nation about D-Day saying, “ The best way in which we can help is by doing our jobs here better than ever before, no matter what these jobs may be.”

It would take a year for the Allies to take Berlin. Unfortunately, the Soviet Union would get there first, with soldiers raping and pillaging German cities as they went.

Women in the Manhattan Project:

Back in the US, women scientists helped win the war for the Allies. Leona Woods Marshall worked on Enrico Fermi’s Manhattan Project team that created a self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction at the University of Chicago. Think of how complicated it was to make. Her contributions were overlooked when Fermi received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry, but another woman scientist, Maria Goepert Mayer, did earn a Nobel prize for her work in nuclear physics. Both women’s work was key to the development of the atomic bomb.

Atomic Heritage Foundation

Atomic Heritage Foundation

Lilli Hornig was a Harvard chemist recruited with her fellow scientist husband to work at the Los Alamos site in New Mexico. But when she arrived and met with the site’s officials, they asked how fast she could type. She retorted, “I don’t type.” Her later work was in plutonium chemistry.

Chien-Shiung Wu was also a major contributor to the Manhattan Project. Born in Jiangsu Province, China in 1912, she excelled in academics from an early age. In 1936, she traveled to the United States to undertake her Ph.D. in Physics at the University of California Berkeley. There, J. Robert Oppenheimer served on her degree committee. After graduation, she was invited to work on the Manhattan Project, where her work directly contributed to the creation of the atomic bomb. After WWII, she joined Columbia University where she was the first woman to become a tenured physics professor at the university. Her work on parity was instrumental in her colleagues Tsung-Dao Lee and Chen-Ning Yang winning the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1957, despite later protests that she should also have won. She was awarded the inaugural Wolf Prize in Physics in 1978.

Many women who worked at the Y-12 Electromagnetic Separation Plant had no idea of the critical nature of their work. The “Girls of Atomic City” operated uranium separation machines to create the U-235 isotope that fueled atomic devices. Women who came to these top secret sites as wives and children of scientists had no idea what their spouses did for work, but did the work that kept these sites functioning.

When the first atomic weapon was successfully detonated–known as the Trinity Test–Lilli Hornig remarked, “We thought in our innocence … if we petitioned hard enough, they may do a demonstration test… But of course the military made the decision well before... [that] they were going to use it no matter what.”

While the introduction of atomic warfare is a deeply complicated part of American history, on August 6 and 9th the first atomic bombs dropped in Hiroshima and Nagasaki effectively ended the war in Japan. And the women involved–for better or worse–were part of that history.

Conclusion:

In the wake of the Axis forces surrendering, the United States maintained a military presence in Japan to support rehabilitation efforts. The war was over, but the Cold War was beginning. Many women stayed on to help finish the job. As men returned from wartime service there was pressure on women to give up their high-paying war jobs and go back to their lower paid, often segregated work– and that was not cool, becoming the catalyst for the Civil Rights and Women’s Rights movements that shortly followed. From efforts at home, in the job force, overseas in the military, in the science lab, to even on the baseball field–American women made extensive and important contributions to the United States’ in the Second World War.

By the end of this era, so much remained in question. Would the progress made by women in this time remain into the post-war period? How would the mistreatment of people of color impact the post-war years and what role would those women play in transforming American society? Would the new options for women in the military and the workforce remain? Or would WWII be like other wars when women returned to more traditionally feminine roles? And finally, were women invisible? Absolutely not.

Chien-Shiung Wu was also a major contributor to the Manhattan Project. Born in Jiangsu Province, China in 1912, she excelled in academics from an early age. In 1936, she traveled to the United States to undertake her Ph.D. in Physics at the University of California Berkeley. There, J. Robert Oppenheimer served on her degree committee. After graduation, she was invited to work on the Manhattan Project, where her work directly contributed to the creation of the atomic bomb. After WWII, she joined Columbia University where she was the first woman to become a tenured physics professor at the university. Her work on parity was instrumental in her colleagues Tsung-Dao Lee and Chen-Ning Yang winning the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1957, despite later protests that she should also have won. She was awarded the inaugural Wolf Prize in Physics in 1978.

Many women who worked at the Y-12 Electromagnetic Separation Plant had no idea of the critical nature of their work. The “Girls of Atomic City” operated uranium separation machines to create the U-235 isotope that fueled atomic devices. Women who came to these top secret sites as wives and children of scientists had no idea what their spouses did for work, but did the work that kept these sites functioning.

When the first atomic weapon was successfully detonated–known as the Trinity Test–Lilli Hornig remarked, “We thought in our innocence … if we petitioned hard enough, they may do a demonstration test… But of course the military made the decision well before... [that] they were going to use it no matter what.”

While the introduction of atomic warfare is a deeply complicated part of American history, on August 6 and 9th the first atomic bombs dropped in Hiroshima and Nagasaki effectively ended the war in Japan. And the women involved–for better or worse–were part of that history.

Conclusion:

In the wake of the Axis forces surrendering, the United States maintained a military presence in Japan to support rehabilitation efforts. The war was over, but the Cold War was beginning. Many women stayed on to help finish the job. As men returned from wartime service there was pressure on women to give up their high-paying war jobs and go back to their lower paid, often segregated work– and that was not cool, becoming the catalyst for the Civil Rights and Women’s Rights movements that shortly followed. From efforts at home, in the job force, overseas in the military, in the science lab, to even on the baseball field–American women made extensive and important contributions to the United States’ in the Second World War.

By the end of this era, so much remained in question. Would the progress made by women in this time remain into the post-war period? How would the mistreatment of people of color impact the post-war years and what role would those women play in transforming American society? Would the new options for women in the military and the workforce remain? Or would WWII be like other wars when women returned to more traditionally feminine roles? And finally, were women invisible? Absolutely not.

Draw your own conclusions

|

Learn how to teach with inquiry.

Many of these lesson plans were sponsored in part by the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources Eastern Region Program, coordinated by Waynesburg University, the History and Social Studies Education Faculty at Plymouth State University, and the Patrons of the Remedial Herstory Project. |

Lesson Plans from Other Organizations

- The National Women's History Museum has lesson plans on women's history.

- The Guilder Lehrman Institute for American History has lesson plans on women's history.

- The NY Historical Society has articles and classroom activities for teaching women's history.

- Unladylike 2020, in partnership with PBS, has primary sources to explore with students and outstanding videos on women from the Progressive era.

- The Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media has produced recommendations for teaching women's history with primary sources and provided a collection of sources for world history. Check them out!

- The Stanford History Education Group has a number of lesson plans about women in World History.

Period Specific Lesson Plans from Other Organizations

- Rosie the Rivetter

- Clio: Rosie the Riveter is one of the most iconic images from World War II. She represents women who took on industrial work for the duration of the war. Students will look at poster art to examine how women on the home front were represented as patriotic workers during World War II. They will learn about one of the most extraordinary propaganda campaigns in American history.

- Gilder Lehrman: Although often understated, the social, economic, and political contributions of American women have all had profound effects on the course of this nation. For evidence of this, one needs to look no further than the many roles that women have played during wartime. From the Revolutionary War's "Molly Pitcher" to the thousands of women serving the United States military today, women have not only had a direct impact on the conflicts of their times but have also successfully transformed such experiences into opportunities for future generations. Never was this more apparent than during World War II. From 1941 to 1945, more than 200,000 women served in the United States military, while over six million flooded the American workforce. Furthermore, countless women—single and married—supported the Allied war effort through activities like civic campaigning and rationing. Many American students are aware that women played a role in the Second World War. Unfortunately this knowledge is often limited only to images of "Rosie the Riveter" and the wives and mothers left to manage households on their own. This lesson is designed to introduce and promote an interest in the many essential roles that women carried out during World War II and how they did so with great success. The driving force of this lesson is a student project entitled "The Faces of War" (see both Activity Three and the Extension Activity of this lesson for further details).

- Women in the Service:

- Edcitement: In this lesson, students will explore the contributions of the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASPs) during World War II. They will examine portrayals of women in World War II posters (and newsreels) and compare and contrast them with personal recollections of the WASPs. Students will gain an understanding of the importance of the WASP program, which enhanced careers for women in aviation. Students can also explore the EDSITEment Learning Lab collection "Breaking Barriers: Race, Gender, and the U.S. Military" to learn more about the contributions of women to multiple U.S. war efforts.

- Eleanor Roosevelt:

- Gilder Lehrman: Students will be asked to read and analyze primary and secondary sources about Eleanor Roosevelt and the work she did to support social justice issues both in the United States and around the world. They will look at the role of first lady and see how Mrs. Roosevelt expanded that role to influence the political, social, and economic issues of the twentieth century. Students will increase their literacy skills as outlined in the Common Core Standards as they explore the social justice actions taken by Eleanor Roosevelt, which at times changed the course of world events.

- Edcitement: This lesson asks students to explore the various roles that Eleanor Roosevelt took on, among them: First Lady, political activist for civil rights, newspaper columnist and author, and representative to the United Nations. Students will read and analyze materials written by and about Eleanor Roosevelt to understand the changing roles of women in politics. They will look at Eleanor Roosevelt's role during and after the New Deal as well as examine the lives and works of influential women who were part of her political network. They will also examine the contributions of women in Roosevelt's network who played critical roles in shaping and administering New Deal policies.

- National Womens History Museum: The purpose of this lesson is to learn about Eleanor Roosevelt as an agent of social change as the First Lady of the United States and later as a representative to the United Nations. Moreover, students will learn how Mrs. Roosevelt used her position as the First Lady to become a champion of human rights which extended after her time in the White House. Students will read primary sources to better understand the legacy of Mrs. Roosevelt.

D-Day

Martha Gelhorn: The Face of War

Martha Gelhorn was on the beach the morning of D-Day as a journalist. She was the only woman on the beach and was one of the first journalists to witness the event. The morning of D-Day, she had hoped to join the many male journalists covering the story, but was not permitted to be there by the military. She wrote letters to the military leaders demanding that she be permitted to witness the invasion on behalf of her magazine. She said, “It is necessary that I report on this war. I do not feel there is any need to beg as a favour for the right to serve as the eyes for millions of people in America who are desperately in need of seeing, but cannot see for themselves.” She was denied. Her estranged husband, Hemingway, applied for her spot and got it, he didn’t even work for a magazine, but he was famous.

The morning of the invasion, she got onto a ship on the pretense of interviewing nurses and stowed away in a bathroom on board so that she, like the male journalists, could write a first hand account of the day. After the initial assault on the beach she emerged with some doctors and helped them tend the wounded. At this point 9,000 allied soldiers were dead. She got there before Hemingway. Her account was later published in Colliers Magazine and many people found it a better read than the more widely published work of her ex because it was more human. She said, “all of us knew that our own wounded were good men and that with their amazing help, their selflessness and self-control, we would get through all right.” Gelhorn was stripped of her accreditation and sent to a nurses camp simply for wanting to do her job like other journalists, her only offense was that she was a woman. She subsequently escaped and flew to Italy to continue covering the war. The next Allied women to land on the beach would come a month later.

A Little Herstory Editors. “Committed to Reporting the Truth.” A Little Herstory. Last modified September 1, 2019, https://www.herstory-online.com/single-post/2019/09/01/Committed-to-Reporting-the-Truth.

Then we saw the coast of France and suddenly we were in the midst of the Armada of the invasion. People will be writing about this site for one hundred years and whoever saw it will never forget it. First it seemed incredible; then there could not be so many ships in the world. Then it seemed incredible as a feet of planning; if there were so many ships, what genius is required to get them there, what amazing and unimaginable genius. After the first shock of wonder and admiration, one began to look around and see separate details. They were destroyers and battleships and transports, a floating city of huge vessels anchored before the green cliffs of Normandy. Occasionally you could see a gun flash or perhaps only hear a distant roar, as a naval guns fired far over those hills. Small craft Beatles around in a curiously jolly way. It looks like a lot of fun to race from shore to ship in snubnose boats beating up the spray. It was no fun at all, considering the mines and obstacles that remained in the water, the sunken tanks with only the radio antenna showing above the water, the drowned bodies that still floated past. On an LCT near us washing was hung up on a line, in between the loud explosions of mines being that needed on the beach dance music could be hard coming from it’s radio. Barrage balloons, always looking like comic toy elephants bounced in the Highwind above the mast ships, and invisible planes drone behind the gray ceiling of cloud. Troops were unloading from big ships too heavy cement barges or to light craft, and on the shore moving up for brown roads that scarred the hillside, our tanks clanked slowly and steadily forward.

Then we stopped noticing the invasion, the ships, the ominous beach, because the first wounded had arrived. And LCT Drew alongside our ship, pitching in the waves; a soldier in a steel helmet shouted up to the crew at the aft rail, and a wooden box looking like a lidless coffin was lowered on a pulley, and with the greatest difficulty, bracing themselves against the movement of their boats, the men on the LCT latest structure inside the box. The box was raised to our deck and out of it was lifted a man who is closer to being a boy than a man, dead white and seemingly dying. The first spoon did Mandy brought to that ship for safety and care was a German prisoner.

Everything happened at once. We had six water ambulances, light motor launches, which swung down from the Shipp side and could be raised the same way when full of wounded. They carried six litter cases apiece or as many walking wounded as could be crowded into them...

The captain came down from the Bridge to watch this. He was feeling cheerful and he now remarked, “I got us in all right but God knows how we will ever get out.“ He gestured toward the ship that were stick around us as cars in a parking lot. “Worry about that some other time.“

Wounded were pouring in now, hauled up in the lidless coffin or swung aboard in the motor ambulances… An American soldier on that same deck had a head wound so horrible that he was not moved. Nothing could be done for him and anything, any touch, would have made him worse. The next morning he was drinking coffee. His eyes looked very dark and strange, as if he had been a long way away, so far away that he almost could not get back. His face was set in lines of weariness and pain, but when asked how he felt, he said he was okay. He was never known to say anything more…

We waded ashore in water to our waists… It was almost dark by now and there was a terrible feeling of working against time.

Everyone was violently busy on that crowded and dangerous shore. The pebbles were the size of melons and we stumbled up a road that a huge road shovel was scooping out… The dust that rose in the gray night light seemed like the fog of war itself… all of us knew that our own wounded were good men and that with their amazing help, their selflessness and self-control, we would get through it all right.

Gelhorn, Martha. The Face of War. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1959.

Questions:

The morning of the invasion, she got onto a ship on the pretense of interviewing nurses and stowed away in a bathroom on board so that she, like the male journalists, could write a first hand account of the day. After the initial assault on the beach she emerged with some doctors and helped them tend the wounded. At this point 9,000 allied soldiers were dead. She got there before Hemingway. Her account was later published in Colliers Magazine and many people found it a better read than the more widely published work of her ex because it was more human. She said, “all of us knew that our own wounded were good men and that with their amazing help, their selflessness and self-control, we would get through all right.” Gelhorn was stripped of her accreditation and sent to a nurses camp simply for wanting to do her job like other journalists, her only offense was that she was a woman. She subsequently escaped and flew to Italy to continue covering the war. The next Allied women to land on the beach would come a month later.

A Little Herstory Editors. “Committed to Reporting the Truth.” A Little Herstory. Last modified September 1, 2019, https://www.herstory-online.com/single-post/2019/09/01/Committed-to-Reporting-the-Truth.

Then we saw the coast of France and suddenly we were in the midst of the Armada of the invasion. People will be writing about this site for one hundred years and whoever saw it will never forget it. First it seemed incredible; then there could not be so many ships in the world. Then it seemed incredible as a feet of planning; if there were so many ships, what genius is required to get them there, what amazing and unimaginable genius. After the first shock of wonder and admiration, one began to look around and see separate details. They were destroyers and battleships and transports, a floating city of huge vessels anchored before the green cliffs of Normandy. Occasionally you could see a gun flash or perhaps only hear a distant roar, as a naval guns fired far over those hills. Small craft Beatles around in a curiously jolly way. It looks like a lot of fun to race from shore to ship in snubnose boats beating up the spray. It was no fun at all, considering the mines and obstacles that remained in the water, the sunken tanks with only the radio antenna showing above the water, the drowned bodies that still floated past. On an LCT near us washing was hung up on a line, in between the loud explosions of mines being that needed on the beach dance music could be hard coming from it’s radio. Barrage balloons, always looking like comic toy elephants bounced in the Highwind above the mast ships, and invisible planes drone behind the gray ceiling of cloud. Troops were unloading from big ships too heavy cement barges or to light craft, and on the shore moving up for brown roads that scarred the hillside, our tanks clanked slowly and steadily forward.

Then we stopped noticing the invasion, the ships, the ominous beach, because the first wounded had arrived. And LCT Drew alongside our ship, pitching in the waves; a soldier in a steel helmet shouted up to the crew at the aft rail, and a wooden box looking like a lidless coffin was lowered on a pulley, and with the greatest difficulty, bracing themselves against the movement of their boats, the men on the LCT latest structure inside the box. The box was raised to our deck and out of it was lifted a man who is closer to being a boy than a man, dead white and seemingly dying. The first spoon did Mandy brought to that ship for safety and care was a German prisoner.

Everything happened at once. We had six water ambulances, light motor launches, which swung down from the Shipp side and could be raised the same way when full of wounded. They carried six litter cases apiece or as many walking wounded as could be crowded into them...

The captain came down from the Bridge to watch this. He was feeling cheerful and he now remarked, “I got us in all right but God knows how we will ever get out.“ He gestured toward the ship that were stick around us as cars in a parking lot. “Worry about that some other time.“

Wounded were pouring in now, hauled up in the lidless coffin or swung aboard in the motor ambulances… An American soldier on that same deck had a head wound so horrible that he was not moved. Nothing could be done for him and anything, any touch, would have made him worse. The next morning he was drinking coffee. His eyes looked very dark and strange, as if he had been a long way away, so far away that he almost could not get back. His face was set in lines of weariness and pain, but when asked how he felt, he said he was okay. He was never known to say anything more…

We waded ashore in water to our waists… It was almost dark by now and there was a terrible feeling of working against time.

Everyone was violently busy on that crowded and dangerous shore. The pebbles were the size of melons and we stumbled up a road that a huge road shovel was scooping out… The dust that rose in the gray night light seemed like the fog of war itself… all of us knew that our own wounded were good men and that with their amazing help, their selflessness and self-control, we would get through it all right.

Gelhorn, Martha. The Face of War. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1959.

Questions:

- What human sacrifices were witnessed by Gelhorn?

- How might this description be helpful to families of soldiers back home?

The Diary of Marie Louise Osmot

Americans often forget that wars happen in people’s backyards. The Atlantic and Pacific oceans prevent Americans from facing the full realities of war that other nations feel so deeply. So of course many perhaps forget to consider the French women who witnessed the invasion first hand. One of the best eyewitnesses to D-Day was Marie Louise Osmont, She kept a diary throughout the war and the morning of the invasion. Her gorgeous home sat moments from the beaches. It had been occupied by the Nazi’s since the fall of France. In the diary, she refers to the “Tommies,” a nickname for the English.

June 4, 1944

Quiet, warm day; Night, by contrast, filled with the noise of six drunks staggering and bawling. The three NCOs in the “mean Speiss” we’re dead drunk! They click heels nevertheless.

June 6, 1944

Landing!! During the night of the 5th to 6th, I am awakened by a considerable rumbling of airplanes and buy cannon fire, prolong but fairly far away. Then noises in the garden and in the house: talking, loading ammunition boxes, nailing. I get up, go to the window. I see the big 15 Dash ton truck arriving, coming from the drive and pulling up in front of the stoop, and another truck backing up to the dining room window. I gather that a departure has begun, and I envisioned the unit moving to a new camp, and in the middle of the night as always. I am annoyed at the idea of changing troops. I stay up wondering. I watch through the keyhole of my door, which faces that of the Kommandantur. In the lake, I catch sight of shadows moving in the office. They’re dragging socks, boxes; they come up and go down. I recognized Mr. George, the bookkeeper, the Spiess. They don’t look happy. I stay by the window. The airplanes fly over in tight formations, round and round continuously. I envision German airplanes over flying the departure. I’m surprised. But the campfire gets closer, intensifies, pounds methodology; what’s going on? Great turmoil in the garden. The men have shouted, “Alarm”, from man to man with a siren hasn’t sounded. The Spiess fidgets, plays with the dog, with his unusual error of a man playing at being important... nothing more.

Little by little the grey dawn comes up, but by this time around, from the intensity of the aircraft in the canon an idea springs to mind: landing! I get dressed her early. I cross the garden, the men recognition as me. In one of the foxholes in front of the house, a wrecking nice one of the young man from the office; he has had phones on his ear the telephone having been move there. Airplanes,Canon right on the coast almost on us. I cross the road, run to the farm, come across Mel temps. “Well!“ I say, “is this it, this time?“ “Yes,“ he says, “I think so, and I’m really afraid we’re in a sector that’s being attacked; that’s going to be something!“ Were definite by the airplanes which make a never ending round, very low; obviously what I thought were German airplanes were quite simply English ones, protecting the landing. Coming from the sea, a dense artificial cloud; it’s ominous and begins to be alarming; the first shells his overheads. I feel cold; I’m agitated. I go back home, dress more warmly, close the door; I go to get Bernice to get into the trench, a quick bowl of milk and we run – just in time! The shells his explode continually in the trench in the farmyard parentheses the one that was dug in 1940 parentheses we find three or four Germans: Leo the cook, his helper, and to others crouching, not proud parentheses except for Leo, who stays outside to watch parentheses. We ask them, “ Tommy come?” They say yes, with conviction. Morning in the trench, with overhead the hisses and winds that make you bend even lower. For fun Leo fires a rifle shot at a low flying airplane, but the Spiess  appears and choose him out horribly; this is not the time to attract attention. Shelves are exploding everywhere, and not far away with short moments of calm; we take advantage of these to run and deal with the animals, and we return with hearts pounding to borrow into the trench. Each time a shell hisses by too low, I cling to the back of the cooks helper; it makes me feel a little more secure, and he turns around with a big smile. The fact is that we’re all afraid...

The afternoon is endless. At one point the sound of footsteps makes us jump up and look toward the opening, expecting anything. Consternation: it’s the replacement Spiess parentheses the nice dark- haired one parentheses, who, with a revolver in his hand, his submachine gun under his other Arm, and followed by a soldier carrying two boxes of ammunition on his shoulder, has come to see whether there are any stragglers still in the holes. He seems exhausted. He’s wounded near the year and there’s a trickle of blood; he sick down for a few moments on the edge of the trench, looking at us with sympathy and as it feeling sorry for us. A few words about his wound, a few words about “the Tommy’s here,” and he leaves. We continue to wait. The first English soldiers appear in the pasture by behind the farm at 2 o’clock. They come down, submachine guns and machine guns under their arms walking steadily, not trying to hide at all. Around 6 o’clock a lull. We get out and go to the house to care for the animals and get things to spend the night underground. And then we see the first damage. Branches of the big walnut broken roof on the outbuildings heavily damaged, a big hole all the way up, I keep a broken roof tiles on the ground, a few window panes at My Pl., Dash hundreds of slight blown off the Château, walls cracked first floor shutters won’t close – but at Bernice‘s it’s worse an airplane or tank shell has exploded in the paving of her kitchen at the corner of the stairs, in the whole interior of the room is devastated: the big clock, dishes, cooking equipment, walls, everything is riddled with holes, the dishes in broken pieces as are almost all the window panes...

The English tanks are silhouetted from time to time on the road above Periers. Grand impassioned exchanges on the road with people from the farm; we are all stupefied by the sudden this summer events….

June 7, 1944

Above our heads, sudden and horrifying, and airplane battle. I hung the walls of the outbuildings; I’m terrified. I want to get to the trench, to escape the machine gun bullets that smack everywhere. I run when I get to the turn that leads to the farmyard a throw myself flat on the ground, bewildered, glued to the slope. Suddenly everything’s erupting, everything falling around me. I feel a painful blow to the small of my back. I see balls of fire a few meters in front of me. I raise my head instinctively and catch sight of an airplane falling in flames. All in that few seconds I’m mad with terror and distress. I’m talking to myself, I say to myself, “I’m hit,“ and my first thought is to wonder whether I’ll be able to walk. Yes, I can get up, so I walk or run parentheses I don’t remember now parentheses, and I take refuge grasping for breath in the kitchen; I stay on my feet, glued to the wall between the two doors. I lean my head against the wall; I tried to call myself. Blood is running down my face my left arm hurts, but the right side of my back hurts so much more so I try to see whether my back is bleeding a lot. I take off my leather belt, and I see that it probably save me from death, the scout belt brought for the Red Cross and on which I hung a medallion of Saint George. ...

Day spent hiding, hitting the ground, running. Always the rotten fear, and still at times you get used to it...

The firing of the Naval shells empties you absolutely; you have the feeling that a runaway train is passing over your body. The straw stacks at the farm catch fire, probably hit by a shell. The English tanks Stream by continually in front of the house; the men salute with two fingers in the shape of a V parentheses victory! Parentheses. French flag hung on the school by the soldiers. In the evening some excitement: we learned that there are still Germans hidden in the woods. With a boy from the farm leading them, who do we see arriving, drawn, pale, hands dangling, guarded by Tommy‘s with machine guns? The tailor who slept on the third floor in the tall redhead who constantly worked on his vehicle in the garden. What a sight: these men surrounded, taken prisoner, sitting on the ground distraught, the little Taylor near tears. I am overwhelmed by this human English. I’d like to comfort them, encourage them. I try to get across to them that it’s better this way, that for them the war is over, that they won’t be killed. The Taylor talks to me about his wife, about his child. He sensed that he’s gripped by anguish, and his eyes constantly seek mine because he feels I understand him. We bring them eggs and milk, and we talk with them for a long time; the tummies are truly accommodating they both asked to get their overcoats from the car, and someone escorts them. They come back having found chocolate, and these poor devils who haven’t eaten since yesterday want to offer us some. We stay around them until late in the evening. The tailor is very much afraid of sinking on his way to England; he still believes in his countries victory, but not his comrade, who says they will never have enough equipment to fight. A little later they leave in a truck, waving goodbye to us and somewhat cheered...

I am horribly sad…

The Tommies distribute cigarettes, chocolate, candy…

Noisy night, cannon fire, airplanes, machine guns, but we are so worn out with fatigue that we sleep a little wet anyway. Ribs hurt pretty badly in the morning!

Osmont, Marie-Louise. “The Normandy Diary of Marie-Louise Osmont.”New York: Random

House, 1994.

Questions:

June 4, 1944

Quiet, warm day; Night, by contrast, filled with the noise of six drunks staggering and bawling. The three NCOs in the “mean Speiss” we’re dead drunk! They click heels nevertheless.

June 6, 1944

Landing!! During the night of the 5th to 6th, I am awakened by a considerable rumbling of airplanes and buy cannon fire, prolong but fairly far away. Then noises in the garden and in the house: talking, loading ammunition boxes, nailing. I get up, go to the window. I see the big 15 Dash ton truck arriving, coming from the drive and pulling up in front of the stoop, and another truck backing up to the dining room window. I gather that a departure has begun, and I envisioned the unit moving to a new camp, and in the middle of the night as always. I am annoyed at the idea of changing troops. I stay up wondering. I watch through the keyhole of my door, which faces that of the Kommandantur. In the lake, I catch sight of shadows moving in the office. They’re dragging socks, boxes; they come up and go down. I recognized Mr. George, the bookkeeper, the Spiess. They don’t look happy. I stay by the window. The airplanes fly over in tight formations, round and round continuously. I envision German airplanes over flying the departure. I’m surprised. But the campfire gets closer, intensifies, pounds methodology; what’s going on? Great turmoil in the garden. The men have shouted, “Alarm”, from man to man with a siren hasn’t sounded. The Spiess fidgets, plays with the dog, with his unusual error of a man playing at being important... nothing more.

Little by little the grey dawn comes up, but by this time around, from the intensity of the aircraft in the canon an idea springs to mind: landing! I get dressed her early. I cross the garden, the men recognition as me. In one of the foxholes in front of the house, a wrecking nice one of the young man from the office; he has had phones on his ear the telephone having been move there. Airplanes,Canon right on the coast almost on us. I cross the road, run to the farm, come across Mel temps. “Well!“ I say, “is this it, this time?“ “Yes,“ he says, “I think so, and I’m really afraid we’re in a sector that’s being attacked; that’s going to be something!“ Were definite by the airplanes which make a never ending round, very low; obviously what I thought were German airplanes were quite simply English ones, protecting the landing. Coming from the sea, a dense artificial cloud; it’s ominous and begins to be alarming; the first shells his overheads. I feel cold; I’m agitated. I go back home, dress more warmly, close the door; I go to get Bernice to get into the trench, a quick bowl of milk and we run – just in time! The shells his explode continually in the trench in the farmyard parentheses the one that was dug in 1940 parentheses we find three or four Germans: Leo the cook, his helper, and to others crouching, not proud parentheses except for Leo, who stays outside to watch parentheses. We ask them, “ Tommy come?” They say yes, with conviction. Morning in the trench, with overhead the hisses and winds that make you bend even lower. For fun Leo fires a rifle shot at a low flying airplane, but the Spiess  appears and choose him out horribly; this is not the time to attract attention. Shelves are exploding everywhere, and not far away with short moments of calm; we take advantage of these to run and deal with the animals, and we return with hearts pounding to borrow into the trench. Each time a shell hisses by too low, I cling to the back of the cooks helper; it makes me feel a little more secure, and he turns around with a big smile. The fact is that we’re all afraid...

The afternoon is endless. At one point the sound of footsteps makes us jump up and look toward the opening, expecting anything. Consternation: it’s the replacement Spiess parentheses the nice dark- haired one parentheses, who, with a revolver in his hand, his submachine gun under his other Arm, and followed by a soldier carrying two boxes of ammunition on his shoulder, has come to see whether there are any stragglers still in the holes. He seems exhausted. He’s wounded near the year and there’s a trickle of blood; he sick down for a few moments on the edge of the trench, looking at us with sympathy and as it feeling sorry for us. A few words about his wound, a few words about “the Tommy’s here,” and he leaves. We continue to wait. The first English soldiers appear in the pasture by behind the farm at 2 o’clock. They come down, submachine guns and machine guns under their arms walking steadily, not trying to hide at all. Around 6 o’clock a lull. We get out and go to the house to care for the animals and get things to spend the night underground. And then we see the first damage. Branches of the big walnut broken roof on the outbuildings heavily damaged, a big hole all the way up, I keep a broken roof tiles on the ground, a few window panes at My Pl., Dash hundreds of slight blown off the Château, walls cracked first floor shutters won’t close – but at Bernice‘s it’s worse an airplane or tank shell has exploded in the paving of her kitchen at the corner of the stairs, in the whole interior of the room is devastated: the big clock, dishes, cooking equipment, walls, everything is riddled with holes, the dishes in broken pieces as are almost all the window panes...

The English tanks are silhouetted from time to time on the road above Periers. Grand impassioned exchanges on the road with people from the farm; we are all stupefied by the sudden this summer events….

June 7, 1944

Above our heads, sudden and horrifying, and airplane battle. I hung the walls of the outbuildings; I’m terrified. I want to get to the trench, to escape the machine gun bullets that smack everywhere. I run when I get to the turn that leads to the farmyard a throw myself flat on the ground, bewildered, glued to the slope. Suddenly everything’s erupting, everything falling around me. I feel a painful blow to the small of my back. I see balls of fire a few meters in front of me. I raise my head instinctively and catch sight of an airplane falling in flames. All in that few seconds I’m mad with terror and distress. I’m talking to myself, I say to myself, “I’m hit,“ and my first thought is to wonder whether I’ll be able to walk. Yes, I can get up, so I walk or run parentheses I don’t remember now parentheses, and I take refuge grasping for breath in the kitchen; I stay on my feet, glued to the wall between the two doors. I lean my head against the wall; I tried to call myself. Blood is running down my face my left arm hurts, but the right side of my back hurts so much more so I try to see whether my back is bleeding a lot. I take off my leather belt, and I see that it probably save me from death, the scout belt brought for the Red Cross and on which I hung a medallion of Saint George. ...

Day spent hiding, hitting the ground, running. Always the rotten fear, and still at times you get used to it...

The firing of the Naval shells empties you absolutely; you have the feeling that a runaway train is passing over your body. The straw stacks at the farm catch fire, probably hit by a shell. The English tanks Stream by continually in front of the house; the men salute with two fingers in the shape of a V parentheses victory! Parentheses. French flag hung on the school by the soldiers. In the evening some excitement: we learned that there are still Germans hidden in the woods. With a boy from the farm leading them, who do we see arriving, drawn, pale, hands dangling, guarded by Tommy‘s with machine guns? The tailor who slept on the third floor in the tall redhead who constantly worked on his vehicle in the garden. What a sight: these men surrounded, taken prisoner, sitting on the ground distraught, the little Taylor near tears. I am overwhelmed by this human English. I’d like to comfort them, encourage them. I try to get across to them that it’s better this way, that for them the war is over, that they won’t be killed. The Taylor talks to me about his wife, about his child. He sensed that he’s gripped by anguish, and his eyes constantly seek mine because he feels I understand him. We bring them eggs and milk, and we talk with them for a long time; the tummies are truly accommodating they both asked to get their overcoats from the car, and someone escorts them. They come back having found chocolate, and these poor devils who haven’t eaten since yesterday want to offer us some. We stay around them until late in the evening. The tailor is very much afraid of sinking on his way to England; he still believes in his countries victory, but not his comrade, who says they will never have enough equipment to fight. A little later they leave in a truck, waving goodbye to us and somewhat cheered...

I am horribly sad…

The Tommies distribute cigarettes, chocolate, candy…

Noisy night, cannon fire, airplanes, machine guns, but we are so worn out with fatigue that we sleep a little wet anyway. Ribs hurt pretty badly in the morning!

Osmont, Marie-Louise. “The Normandy Diary of Marie-Louise Osmont.”New York: Random

House, 1994.

Questions:

- Who is the source? What bias do they likely have?

- What is Osmont describing in her diary?

- What human sacrifices were witnessed by Osmont?

- Why do you think Osmont is “horribly sad”?

Elanore Roosevelt: My Day

During the war, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt wrote a column for My Day to comfort the American people. Six days a week she wrote to uplift and inspire the women of America. On June 7th, she wrote the following passage.

So at last we have come to D-Day, or rather, the news of it reached us over the radio in the early hours of the morning on June the 6th… I have no sense of excitement whatsoever. It seems as though we have been waiting for this day for weeks, and dreading it, and now all emotion is drained away…

The time is here, and in this country, we live in safety and comfort and wait for victory. It is difficult to make life seem real. It is hard to believe that the beaches of France, which we once knew, are now places from which, in days to come, boys in hospitals over here will tell us that they have returned. They may never go beyond the water or the beach, but all their lives, perhaps, they will bear the marks of this day. At that, they will be fortunate, for many others won't return….

This is the beginning of a long, hard fight, a fight for ports where heavy materials of war must be landed, a fight for airfields in the countries in which we must operate. Day by day, miles of country may be taken, lost and retaken. That is what we have to face, what the boys who are over there have been preparing for and what must be done before the day of victory. That day is coming surely. It will be a happy and glorious day. How can we hasten it?

The best way in which we can help is by doing our jobs here better than ever before, no matter what these jobs may be.

E. R.

Roosevelt, Eleanor. “Eleanor Roosevelt's ‘My Day,’ 6/7/1944: sacrifice on d-day.” White House Historical Association. Electronically Published 2020, https://www.whitehousehistory.org/eleanor-roosevelts-my-day-6-7-1944.

Questions:

So at last we have come to D-Day, or rather, the news of it reached us over the radio in the early hours of the morning on June the 6th… I have no sense of excitement whatsoever. It seems as though we have been waiting for this day for weeks, and dreading it, and now all emotion is drained away…

The time is here, and in this country, we live in safety and comfort and wait for victory. It is difficult to make life seem real. It is hard to believe that the beaches of France, which we once knew, are now places from which, in days to come, boys in hospitals over here will tell us that they have returned. They may never go beyond the water or the beach, but all their lives, perhaps, they will bear the marks of this day. At that, they will be fortunate, for many others won't return….

This is the beginning of a long, hard fight, a fight for ports where heavy materials of war must be landed, a fight for airfields in the countries in which we must operate. Day by day, miles of country may be taken, lost and retaken. That is what we have to face, what the boys who are over there have been preparing for and what must be done before the day of victory. That day is coming surely. It will be a happy and glorious day. How can we hasten it?

The best way in which we can help is by doing our jobs here better than ever before, no matter what these jobs may be.

E. R.

Roosevelt, Eleanor. “Eleanor Roosevelt's ‘My Day,’ 6/7/1944: sacrifice on d-day.” White House Historical Association. Electronically Published 2020, https://www.whitehousehistory.org/eleanor-roosevelts-my-day-6-7-1944.

Questions:

- Who is the source? What bias do they likely have?

- Does Roosevelt seem optimistic?

- What human sacrifices are mentioned by Roosevelt?

- Why is this source important to understanding the impact of D-Day on American and world families?

Women in the WAr

Associated Press: Yamamoto Shot Down

Pay attention to whether women are credited or not in the code breaking that helped kill Japanese Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto.

Yamamoto Shot Down As Result of Code Being Broken in '43

By the Associated Press

Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto-- who boasted he would dictate peach in the White House-- met flaming death in the Solomons in April, 1943, because this country broke a Japanese code.

The commander in chief of the Japanese Navy was shot down by American airmen who knew in advance the course his aerial convoy was to follow. They set an elaborate trap, then sprung it from high above the admiral's tightly guarded bomber.

The Japanese themselves told of Yamamoto 's death, but they did not tell the part American intelligence played in reading coded orders.

Code Cracked in Early 1943

J. Norman Lodge, veteran Associated Press writer, learned of the incident while serving as a war correspondent in the South Pacific. His long unrevealed account related that the enemy code was cracked in March or April, 1943.

As a result, it was known what time Yamamoto would leave Truk, when he would arrive at Buka, and when he would leave Buka for Kahilli for Ballale.

Six Lightnings and some decoys were sent to the rendezvous. The Yamamoto convoy arrived escorted by 20 Zeros.

The decoys, flying at about 18,000 feet, tried to lure the Zeros away, but the enemy fighters stubbornly refused to be drawn from the precious cargo.

Both Bombers Blown Up.

When this strategy failed two Lightnings peeled off at 24,000 feet and headed in a vertical dive for the two Japanese bombers, not knowing which one held Yamamoto.

They exploded both bombers, despite the frantic defense of the Zeros.

Adding two of the zeros to their bag for good measure, both American ships reached home safely, although badly shot up.

Shizuo Sigiura, a correspondent captured in the Philippines, filled in details last July. He said the Japanese themselves credited American foreknowledge of the admiral's flight as being responsible for his death over Shortland, in the upper Solomons.

Associated Press. “Yamamoto Shot Down As Result of Code Being Broken in ‘43.” Evening Star. September 10, 1945. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov.

Questions:

By the Associated Press

Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto-- who boasted he would dictate peach in the White House-- met flaming death in the Solomons in April, 1943, because this country broke a Japanese code.

The commander in chief of the Japanese Navy was shot down by American airmen who knew in advance the course his aerial convoy was to follow. They set an elaborate trap, then sprung it from high above the admiral's tightly guarded bomber.

The Japanese themselves told of Yamamoto 's death, but they did not tell the part American intelligence played in reading coded orders.

Code Cracked in Early 1943

J. Norman Lodge, veteran Associated Press writer, learned of the incident while serving as a war correspondent in the South Pacific. His long unrevealed account related that the enemy code was cracked in March or April, 1943.

As a result, it was known what time Yamamoto would leave Truk, when he would arrive at Buka, and when he would leave Buka for Kahilli for Ballale.

Six Lightnings and some decoys were sent to the rendezvous. The Yamamoto convoy arrived escorted by 20 Zeros.

The decoys, flying at about 18,000 feet, tried to lure the Zeros away, but the enemy fighters stubbornly refused to be drawn from the precious cargo.

Both Bombers Blown Up.

When this strategy failed two Lightnings peeled off at 24,000 feet and headed in a vertical dive for the two Japanese bombers, not knowing which one held Yamamoto.

They exploded both bombers, despite the frantic defense of the Zeros.

Adding two of the zeros to their bag for good measure, both American ships reached home safely, although badly shot up.

Shizuo Sigiura, a correspondent captured in the Philippines, filled in details last July. He said the Japanese themselves credited American foreknowledge of the admiral's flight as being responsible for his death over Shortland, in the upper Solomons.

Associated Press. “Yamamoto Shot Down As Result of Code Being Broken in ‘43.” Evening Star. September 10, 1945. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov.

Questions:

- Who, based on this document, broke the Japanese code that would help kill Admiral Yamamoto?

- Why do you think the article does not name the code breaker(s)?

- Based on this document, did women help win WWII?