7. Women in the Abolition Movement

|

Women of all races identified with the abolition movement–some as Christians, some as humanitarians, some from personal experience–and many became notorious household names for their quest to end slavery in the United States.

|

|

Phyllis Wheatly, Library of Congress

Phyllis Wheatly, Library of Congress

It’s easy to compartmentalize the various human rights struggles of history. Most human rights issues are, and always have been, linked. The struggle for the emancipation of enslaved people was intertwined with the struggle for women’s rights: both in terms of the people advocating for it, and in the systemic and political issues they raised. As members of an oppressed class themselves, women intimately understood the issues at stake and brought empathy, compassion, intelligence, and organizational skills to the abolition movement.

Abolition was a Woman’s Cause:

Recognizing the connection between racial and gender oppression, iconic suffrage pioneer Susan B. Anthony famously urged her followers to “make the slave’s case our own.” But she was just one of many examples.

Advocacy for the abolition movement began in the colonial period. Phyllis Wheatly brought abolitionist ideas to American culture with her poetry. Wheatley was born in West Africa and taken to Boston as a child. In 1773 she was emancipated and became the first published African-American woman poet. Her poems included the reflection on slavery, “On Being brought From Africa,” which opened people’s eyes to the humanity of enslaved people. Her work was even praised by George Washington.

One of America’s earliest advocates for ending slavery was Abigail Adams, who once counseled her husband to “remember the ladies” when he and the Continental Congress were debating independence. In September of 1774, Abigail wrote to John: “I wish most sincerely there was not a Slave in the province. It always appeared a most iniquitous scheme to me—fight ourselves for what we are daily robbing and plundering from those who have as good a right to freedom as we have.” For Abigail Adams, the cause of liberty meant liberty for all.

Leading up to the Civil War, many women called for abolition in private letters and poems, but it was highly unusual for a woman, especially an African-American woman, to speak publicly on the matter. On September 21, 1832, Maria W. Miller Stewart spoke before the African-American Female Intelligence Society in Boston’s Franklin Hall. Stewart’s jeremiad, a form of speaking derived from the sermons of New England ministers, accused white Americans of breaking their covenant with God by supporting slavery. Stewart believed that God would judge Americans for the sin of slavery. She traveled throughout New England sharing her message with Christian Americans.

Women who had experienced the horrors of slavery were incredibly powerful representatives of the abolition movement. Amy Hester (Hetty) Reckless was born into slavery in southern New Jersey. She escaped violence at the hands of her mistress and settled in Philadelphia in 1826, operating a safe house on the underground railroad and supporting education for black children. In 1833, Hetty became a founding member of the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society. Reckless also worked with the Female Vigilant Association starting in 1838, assisting enslaved people on their Underground Railroad journey, often at considerable personal risk.

Black Women Writers:

Black women also wrote powerful pieces to teach people about the horrors of slavery. In 1861, Harriet Jacobs published her autobiography, "Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl." The book chronicles Jacobs’s life on a North Carolina plantation. She wrote about her abuse and her escape from her owner who sought to sexually abuse her. She got out by hiding in a crawlspace in her grandmother’s attic for seven years. When Jacobs finally escaped to New York, she worked as a nanny while supporting both the abolitionist and feminist causes. Her employer eventually purchased her freedom, and Jacobs helped found two schools for formerly enslaved people.

Abolition was a Woman’s Cause:

Recognizing the connection between racial and gender oppression, iconic suffrage pioneer Susan B. Anthony famously urged her followers to “make the slave’s case our own.” But she was just one of many examples.

Advocacy for the abolition movement began in the colonial period. Phyllis Wheatly brought abolitionist ideas to American culture with her poetry. Wheatley was born in West Africa and taken to Boston as a child. In 1773 she was emancipated and became the first published African-American woman poet. Her poems included the reflection on slavery, “On Being brought From Africa,” which opened people’s eyes to the humanity of enslaved people. Her work was even praised by George Washington.

One of America’s earliest advocates for ending slavery was Abigail Adams, who once counseled her husband to “remember the ladies” when he and the Continental Congress were debating independence. In September of 1774, Abigail wrote to John: “I wish most sincerely there was not a Slave in the province. It always appeared a most iniquitous scheme to me—fight ourselves for what we are daily robbing and plundering from those who have as good a right to freedom as we have.” For Abigail Adams, the cause of liberty meant liberty for all.

Leading up to the Civil War, many women called for abolition in private letters and poems, but it was highly unusual for a woman, especially an African-American woman, to speak publicly on the matter. On September 21, 1832, Maria W. Miller Stewart spoke before the African-American Female Intelligence Society in Boston’s Franklin Hall. Stewart’s jeremiad, a form of speaking derived from the sermons of New England ministers, accused white Americans of breaking their covenant with God by supporting slavery. Stewart believed that God would judge Americans for the sin of slavery. She traveled throughout New England sharing her message with Christian Americans.

Women who had experienced the horrors of slavery were incredibly powerful representatives of the abolition movement. Amy Hester (Hetty) Reckless was born into slavery in southern New Jersey. She escaped violence at the hands of her mistress and settled in Philadelphia in 1826, operating a safe house on the underground railroad and supporting education for black children. In 1833, Hetty became a founding member of the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society. Reckless also worked with the Female Vigilant Association starting in 1838, assisting enslaved people on their Underground Railroad journey, often at considerable personal risk.

Black Women Writers:

Black women also wrote powerful pieces to teach people about the horrors of slavery. In 1861, Harriet Jacobs published her autobiography, "Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl." The book chronicles Jacobs’s life on a North Carolina plantation. She wrote about her abuse and her escape from her owner who sought to sexually abuse her. She got out by hiding in a crawlspace in her grandmother’s attic for seven years. When Jacobs finally escaped to New York, she worked as a nanny while supporting both the abolitionist and feminist causes. Her employer eventually purchased her freedom, and Jacobs helped found two schools for formerly enslaved people.

Harriet Tubman, Public Domain

Harriet Tubman, Public Domain

Harriet Tubman was also an impressive figure. After her escape from bondage, Tubman made thirteen trips back to the south to free more than seventy enslaved people. In addition, Tubman gave many powerful speeches on behalf of abolition and women’s rights. Even though she could neither read nor write.

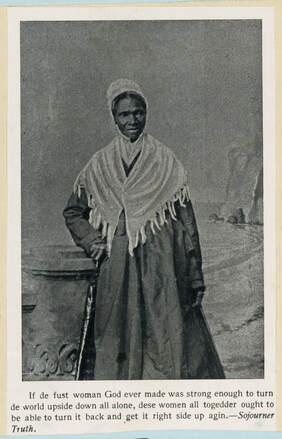

Sojourner Truth, who escaped from slavery in 1826, also rose to prominence speaking about intersectional equal rights. Her speech, “Ain’t I a Woman?” reminded folks that Black women were women too, and yet were not treated as such. It profoundly integrated the issues of racial and gender equality, and reminds us that women’s history isn’t experienced the same way for all women.

In spite of their own struggles to gain equal legal and social rights in American society, American women were in the forefront of the struggle to end slavery. They wrote pamphlets, gave speeches on behalf of enslaved people, and they dedicated their lives and their talents to the task of improving the lives of freed people.

White Women Writers:

More and more white women began to connect the struggle for emancipation from slavery to the journey for equal legal and social rights for women. Margaret Fuller, a philosopher and Transcendentalist colleague of Thoreau and Emerson, noted that restrictions on the economic and political freedom of women were comparable to the restrictions imposed on enslaved people. To be clear, the conditions of women and enslaved persons were not the same. Legally not being allowed to own property is not the same as being property, but Fuller’s point allowed others to consider a more equality-oriented perspective.

Lucretia Mott was active in William Lloyd Garrison’s American Anti-Slavery Society and helped to found the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society in 1833. She was a Quaker preacher, accustomed to speaking her mind in religious spaces, and found it difficult to reconcile that she could not do that outside her congregation. Her sister, Martha Coffin Wright was a friend and supporter of Harriet Tubman. Both were organizers of the first women’s rights convention in 1848 at Seneca Falls, NY.

Lydia Maria Child insisted abolition should be included in a broader social reform context. Born into a religious family, Child trained to be a teacher and founded a school in Watertown, Massachusetts in 1826. She published the Juvenile Miscellany, a magazine for children, but she lost her southern subscribers when she published her anti-slavery views. However, that didn't stop her. In 1833 Child argued for immediate emancipation of enslaved people in An Appeal in Favor of that Class of Americans Called Africans.

Sojourner Truth, who escaped from slavery in 1826, also rose to prominence speaking about intersectional equal rights. Her speech, “Ain’t I a Woman?” reminded folks that Black women were women too, and yet were not treated as such. It profoundly integrated the issues of racial and gender equality, and reminds us that women’s history isn’t experienced the same way for all women.

In spite of their own struggles to gain equal legal and social rights in American society, American women were in the forefront of the struggle to end slavery. They wrote pamphlets, gave speeches on behalf of enslaved people, and they dedicated their lives and their talents to the task of improving the lives of freed people.

White Women Writers:

More and more white women began to connect the struggle for emancipation from slavery to the journey for equal legal and social rights for women. Margaret Fuller, a philosopher and Transcendentalist colleague of Thoreau and Emerson, noted that restrictions on the economic and political freedom of women were comparable to the restrictions imposed on enslaved people. To be clear, the conditions of women and enslaved persons were not the same. Legally not being allowed to own property is not the same as being property, but Fuller’s point allowed others to consider a more equality-oriented perspective.

Lucretia Mott was active in William Lloyd Garrison’s American Anti-Slavery Society and helped to found the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society in 1833. She was a Quaker preacher, accustomed to speaking her mind in religious spaces, and found it difficult to reconcile that she could not do that outside her congregation. Her sister, Martha Coffin Wright was a friend and supporter of Harriet Tubman. Both were organizers of the first women’s rights convention in 1848 at Seneca Falls, NY.

Lydia Maria Child insisted abolition should be included in a broader social reform context. Born into a religious family, Child trained to be a teacher and founded a school in Watertown, Massachusetts in 1826. She published the Juvenile Miscellany, a magazine for children, but she lost her southern subscribers when she published her anti-slavery views. However, that didn't stop her. In 1833 Child argued for immediate emancipation of enslaved people in An Appeal in Favor of that Class of Americans Called Africans.

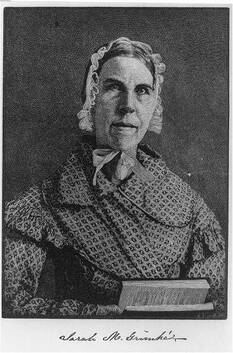

Sarah Grimke, Library of Congress

Sarah Grimke, Library of Congress

While most people relate abolition to the northern states, there were certainly Southern women who worked to end slavery, too. Sarah and Angelina Grimke were born into unimaginable wealth and raised on a South Carolina plantation that included hundreds of enslaved people. The family was so wealthy that each family member had their own personal slave. Using Christian arguments of charity and compassion, both sisters came to abhor slavery. In the 1820s, Angelina wrote to William Llyod Garrison and he published her letter in his journal The Liberator. She was widely criticized, and her writings were burned in Charleston. Despite the ridicule, the Grimke sisters doubled down and became among the most vocal and famous critics of slavery. As feminists, they broke the taboo regarding women’s presence on the lecture circuit, which contributed to their profound and positive influence on both movements, but they faced considerable backlash. Their male abolitionist peers tried to withdraw them from the speaking circuit. When Angelina married Theodore Dwight Weld, a pro-slavery mob burned down Pensylvania Hall where they were married. When they traveled through New England speaking to “mixed audiences,” a mob of protesters surrounded them. Who were they to speak to men?

The Grimke sisters were originally inspired to oppose slavery in part because their brother had children with an enslaved woman. One of these children was Francis James Grimke, who later served as a minister in Washington, D. C.. He married Charlotte Louise Bridges Forten, who came from a prominent free Black abolitionist family in Philadelphia. Forten’s family had a long history of helping enslaved people escape bondage. She trained as a teacher, becoming the first Black graduate of the Salem Normal School in 1856. She was one of the first African-American teachers in Salem and was a member of the Salem Female Anti-Slavery Society, a precursor of the black women’s club movement that flourished in the early twentieth century.

Another South Carolina native, Mary Boykin Chesnut, was the matriarch of a family that owned nearly 1,000 slaves. However, in February of 1861, as Confederate war sentiment was increasing in intensity, Mary Chesnut began to compose a diary that revealed the inner life of the plantation. While not specifically an abolitionist document, Chesnut’s diary, which was published long after her death, provided important material for historians hoping to understand the life of the plantation.

Some women contributed to the abolitionist cause by articulating a religious and moral position against slavery. Harriet Beecher Stowe was a member of a famous family of ministers. In 1832, Harriet moved with her father to Cincinnati, Ohio, a river town that was a northern destination for many escaping enslaved people. She’d listen to debates about slavery in her dad’s Seminary group, and after hearing about the absolutely legal terror happening to human beings, she used her talent to take a stand against oppression. In 1852, while sitting upstairs in the attic and having her sister watch her many children, Stowe wrote and published Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which detailed the horrific conditions and dangers of plantation life. The book and play based on the story were both wildly popular. Legend has it that President Abraham Lincoln told Stowe in 1862, “So you are the little woman who wrote the book that started this great war.” While perhaps a backhanded compliment, it can’t be denied that Stowe’s work affected her readers’ opinions of the political issue. Her home was even a stop along the underground railroad.

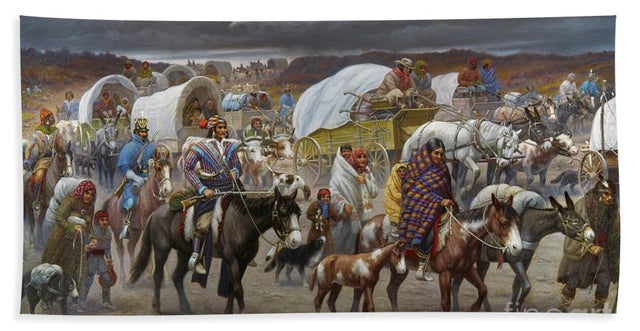

By the late 1850’s the divisions between the north and south were apparent. Talk of secession was eminent. John Brown, a radical abolitionist from New York who had done his part to protest slavery in Bleeding Kansas, led a raid on Harper’s Ferry, Virginia. Harriet Tubman was supposed to be with him, but she was on another mission. For many southerners, Brown’s raid showed the end was near. Southerners were already on edge, and when Lincoln was elected as president in 1860, it was the last straw.

The Grimke sisters were originally inspired to oppose slavery in part because their brother had children with an enslaved woman. One of these children was Francis James Grimke, who later served as a minister in Washington, D. C.. He married Charlotte Louise Bridges Forten, who came from a prominent free Black abolitionist family in Philadelphia. Forten’s family had a long history of helping enslaved people escape bondage. She trained as a teacher, becoming the first Black graduate of the Salem Normal School in 1856. She was one of the first African-American teachers in Salem and was a member of the Salem Female Anti-Slavery Society, a precursor of the black women’s club movement that flourished in the early twentieth century.

Another South Carolina native, Mary Boykin Chesnut, was the matriarch of a family that owned nearly 1,000 slaves. However, in February of 1861, as Confederate war sentiment was increasing in intensity, Mary Chesnut began to compose a diary that revealed the inner life of the plantation. While not specifically an abolitionist document, Chesnut’s diary, which was published long after her death, provided important material for historians hoping to understand the life of the plantation.

Some women contributed to the abolitionist cause by articulating a religious and moral position against slavery. Harriet Beecher Stowe was a member of a famous family of ministers. In 1832, Harriet moved with her father to Cincinnati, Ohio, a river town that was a northern destination for many escaping enslaved people. She’d listen to debates about slavery in her dad’s Seminary group, and after hearing about the absolutely legal terror happening to human beings, she used her talent to take a stand against oppression. In 1852, while sitting upstairs in the attic and having her sister watch her many children, Stowe wrote and published Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which detailed the horrific conditions and dangers of plantation life. The book and play based on the story were both wildly popular. Legend has it that President Abraham Lincoln told Stowe in 1862, “So you are the little woman who wrote the book that started this great war.” While perhaps a backhanded compliment, it can’t be denied that Stowe’s work affected her readers’ opinions of the political issue. Her home was even a stop along the underground railroad.

By the late 1850’s the divisions between the north and south were apparent. Talk of secession was eminent. John Brown, a radical abolitionist from New York who had done his part to protest slavery in Bleeding Kansas, led a raid on Harper’s Ferry, Virginia. Harriet Tubman was supposed to be with him, but she was on another mission. For many southerners, Brown’s raid showed the end was near. Southerners were already on edge, and when Lincoln was elected as president in 1860, it was the last straw.

Julia Ward Howe, Library of Congress

Julia Ward Howe, Library of Congress

When Julia Ward Howe met President Lincoln in 1861, she penned new words to the familiar tune, “John Brown’s Body,” and “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” was created. The song was a popular and invigorating anthem among Union soldiers not only toward victory, but the moral imperative to end slavery. She said:

“Let the Hero, born of woman, crush the serpent with His heel,

Since God is marching on. As He died to make men holy,

let us die to make men free; While God is marching on.

He is coming like the glory of the morning on the wave,

He is wisdom to the mighty, He is honor to the brave;

So the world shall be His footstool, and the soul of wrong His slave,

Our God is marching on."

“Let the Hero, born of woman, crush the serpent with His heel,

Since God is marching on. As He died to make men holy,

let us die to make men free; While God is marching on.

He is coming like the glory of the morning on the wave,

He is wisdom to the mighty, He is honor to the brave;

So the world shall be His footstool, and the soul of wrong His slave,

Our God is marching on."

Harriet E. Wilson, Public Domain

Harriet E. Wilson, Public Domain

Conclusion:

Social norms in the 19th Century demanded middle-class and wealthy women devote their energies to home and family; however, as the nation underwent dramatic shifts, those expectations were frustrating and stifling to many women. In order to fight for the causes that were important to them–morally and religiously–many of these women had to upset gender norms. In the fight for racial equality, these women had to pursue gender equality, too. Thus, American women found their voice and their place in both the struggles for women’s rights and the abolition movement. As we’ve learned, some women wrote books, others wrote songs. Some started schools, others risked their lives on the Underground Railroad. Some had power and wielded it to help others, and some women were born enslaved but became powerful through their actions. Regardless of how these women, and many more like them, attempted to create a more equal country, their attempts would not be in vain.

By the end of this era, so much remained in question. Would the federal government get involved? Would this come to war? Would women’s advocacy be well received? How would women’s politicization impact their role in society? Was suffrage an obvious next step?

Social norms in the 19th Century demanded middle-class and wealthy women devote their energies to home and family; however, as the nation underwent dramatic shifts, those expectations were frustrating and stifling to many women. In order to fight for the causes that were important to them–morally and religiously–many of these women had to upset gender norms. In the fight for racial equality, these women had to pursue gender equality, too. Thus, American women found their voice and their place in both the struggles for women’s rights and the abolition movement. As we’ve learned, some women wrote books, others wrote songs. Some started schools, others risked their lives on the Underground Railroad. Some had power and wielded it to help others, and some women were born enslaved but became powerful through their actions. Regardless of how these women, and many more like them, attempted to create a more equal country, their attempts would not be in vain.

By the end of this era, so much remained in question. Would the federal government get involved? Would this come to war? Would women’s advocacy be well received? How would women’s politicization impact their role in society? Was suffrage an obvious next step?

Draw your Own Conclusions

|

Learn how to teach with inquiry.

Many of these lesson plans were sponsored in part by the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources Eastern Region Program, coordinated by Waynesburg University, the History and Social Studies Education Faculty at Plymouth State University, and the Patrons of the Remedial Herstory Project. |

Lesson Plans from Other Organizations

- The National Women's History Museum has lesson plans on women's history.

- The Gilder Lehrman Institute for American History has lesson plans on women's history.

- The NY Historical Society has articles and classroom activities for teaching women's history.

- Unladylike 2020, in partnership with PBS, has primary sources to explore with students and outstanding videos on women from the Progressive era.

- The Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media has produced recommendations for teaching women's history with primary sources and provided a collection of sources for world history. Check them out!

- The Stanford History Education Group has a number of lesson plans about women in US History.

Period Specific Lesson Plans from Other Organizations

- Women and Slavery:

- C3 Teachers: In November of 1815, an enslaved woman known only as Anna jumped out of a third floor window in Washington DC in what was assumed to be a suicide attempt. Presumed dead, abolitionists used her story to expose the harsh realities of slavery and advocate for better treatment of slaves. In 2015, the Oh Say Can You See research project uncovered an 1828 petition for freedom from an Ann Williams for herself and three children. This woman was the same “Anna” who had leapt from the window, still alive but severely injured from her fall, a contrast to the widely held belief that she had died in the fall. In 1832, a jury ruled in her favor, granting Ann and her three children freedom from master George Williams. Ann and her children went on to live free in Washington, subsisting on the weekly $1.50 that Ann’s still enslaved husband was able to provide for his family. This inquiry and the compelling question seeks to address the autonomy that enslaved African Americans had, and the question of what freedom meant to Anna.

- Stanford History Education Group: In 1937, the Federal Writers' Project began collecting what would become the largest archive of interviews with former slaves. Few firsthand accounts exist from those who suffered in slavery, making this an exceptional resource for students of history. However, as with all historical documents, there are important considerations for students to bear in mind when reading these sources. In this lesson, students examine three of these accounts to answer the question: What can we learn about slavery from interviews with former slaves?

- Gilder Lehrman: Women always played a significant role in the struggle against slavery and discrimination. White and black Quaker women and female slaves took a strong moral stand against slavery. As abolitionists, they circulated petitions, wrote letters and poems, and published articles in the leading anti-slavery periodicals such as the Liberator. Some of these women educated blacks, both free and enslaved, and some of them joined the American Anti-Slavery Society and founded their own biracial organization, the Philadelphia Women’s Anti-Slavery Society. The little-known history of most of these women is a fragmented one. While several of the most well-known activists are mentioned in accounts of the abolitionist movement, there is scant reference to most other female abolitionists. Some brief biographies make reference to the births and deaths of the lesser-known women but offer only limited mention of their work. Through research and analysis in the classroom, students will learn about the diversity of women who participated in anti-slavery activities, the variety of activities and goals they pursued, and the barriers they faced as women.

- National History Day: Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811-1896) was born in Litchfield, Connecticut, the daughter of Lyman and Roxanna Beecher. Harriet grew up in a household that held equality and service to others in the highest regard. Her father and all seven of her brothers became ministers, while her sisters, Catherine and Isabella, were champions of women’s education and suffrage. Harriet received a formal education at Sarah Pierce’s Academy, one of the first institutions focused on educating young women. There she discovered her talent for writing. Harriet became a teacher and author, proving to be an outspoken woman in a time when female voices often went unheard. Following in her family’s tradition of service, she became a passionate abolitionist. She published more than thirty works in her lifetime, the most famous of which was Uncle Tom’s Cabin, a novel that exposed the evils of slavery. Through her writings and speaking engagements, Harriet Beecher Stowe effectively helped to open the eyes of the world to the urgent problem of slavery in the United States. Did Stowe misrepresent slavery?

- Gilder Lehrman: The accounts of African American slavery in textbooks routinely conflate the story of male and female slaves into one history. Textbooks rarely enable students to grapple with the lives and challenges of women constrained by the institution of slavery. The collections of letters and autobiographies of slave women in the nineteenth century now available on the Internet open a window onto the lives of these women and allow teachers and students to explore this history. Using the classroom as a historical laboratory, students can use these primary sources to research, read, evaluate, and interpret the words of African American slave women. The students can be historians; they can discover the history of African American slave women and write their history.

- Gilder Lehrman: Children’s Attitudes about Slavery and Women’s Abolitionism as Seen through Anti-slavery Fairs: Over two days, students will examine the attitudes that children from northern states had about slavery during the 1830s to 1860s and how abolitionists tried to change their way of thinking. They will also explore how woman abolitionists used anti-slavery fairs to generate support for the anti-slavery cause.

- Edcitement: Elizabeth Keckly was born into slavery in 1818 near Petersburg, Virginia. She learned to sew from her mother, an expert seamstress enslaved in the Burwell family. After thirty years as a Burwell slave, Keckly purchased her and her only son's freedom. Later, when Keckly moved to Washington, D. C., she became an exclusive dress designer whose most famous client was First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln. Keckly’s enduring fame results from her close relationship with Mrs. Lincoln, documented in her memoir, Behind the Scenes, or Thirty Years a Slave and Four Years in the White House (1868). In this lesson, students learn firsthand about the childhoods of Jacobs and Keckly from reading excerpts from their autobiographies. They practice reading for both factual information and making inferences from these two primary sources. They will also learn from a secondary source about commonalities among those who experienced their childhood in slavery. By putting all this information together and evaluating it, students get the chance to "be" historians and experience what goes into making sound judgments about a certain problem—in this case, how did child slaves live?

- PBS and DPLA: This collection uses primary sources to explore women in the antebellum reform movement. Digital Public Library of America Primary Source Sets are designed to help students develop their critical thinking skills and draw diverse material from libraries, archives, and museums across the United States. Each set includes an overview, ten to fifteen primary sources, links to related resources, and a teaching guide. These sets were created and reviewed by the teachers on the DPLA's Education Advisory Committee.

- PBS and DPLA: This collection uses primary sources to explore Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl by Harriet Jacobs. Digital Public Library of America Primary Source Sets are designed to help students develop their critical thinking skills and draw diverse material from libraries, archives, and museums across the United States. Each set includes an overview, ten to fifteen primary sources, links to related resources, and a teaching guide. These sets were created and reviewed by the teachers on the DPLA's Education Advisory Committee.

- PBS and DPLA: This collection uses primary sources to explore Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin. Digital Public Library of America Primary Source Sets are designed to help students develop their critical thinking skills and draw diverse material from libraries, archives, and museums across the United States. Each set includes an overview, ten to fifteen primary sources, links to related resources, and a teaching guide. These sets were created and reviewed by the teachers on the DPLA's Education Advisory Committee.

- Seneca Falls:

- Stanford History Education Group: When the 19th Amendment was passed in 1920, the fight for women’s suffrage had already gone on for decades. Many women had hoped that women would win suffrage at the same time as African Americans. However, the Fifteenth Amendment only extended suffrage to African-American men. In this lesson, students explore the broad context of the women’s suffrage movement through reading selections from Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth and Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

- Gilder Lehrman: Under the leadership of Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, a convention for the rights of women was held in Seneca Falls, New York in 1848. It was attended by between 200 and 300 people, both women and men. Its primary goal was to discuss the rights of women—how to gain these rights for all, particularly in the political arena. The conclusion of this convention was that the effort to secure equal rights across the board would start by focusing on suffrage for women. The participants wrote the Seneca Falls Declaration of Sentiments and Resolutions, patterned after the Declaration of Independence. It specifically asked for voting rights and for reforms in laws governing marital status. Reactions to the convention and the new Declaration were mixed. Many people felt that the women and their sympathizers were ridiculous, and newspapers denounced the women as unfeminine and immoral. Little substantive change resulted from the Declaration in 1848, but from that time through 1920, when the goal of women’s suffrage was attained with the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, the Declaration served as a written reminder of the goals of the movement.

- Edcitement: In the spirit of Abigail Adams's challenge to her husband (and his colleagues), this lesson looks at the women's suffrage movement that grew out of debates following the Declaration of Independence and the conclusion of the Continental Congress by "remembering the ladies" who are too often overlooked when teaching about the "foremothers" of the movements for suffrage and women's equality in U.S. history. Grounded in the critical inquiry question "Who's missing?" and in the interest of bringing more perspectives to who the suffrage movement included, this resource will help to ensure that students learn about some of the lesser-known activists who, like Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Mott, and Susan B. Anthony, participated in the formative years of the women's rights movement.

William Lloyd Garrison: The Declaration of Sentiments, American Anti-Slavery Society, 1833

The American Anti-Slavery Society was founded in 1833. The group’s organizer was William Lloyd Garrison, who authored this document. He was well-known as an uncompromising advocate for immediate emancipation. No female members of AASS signed this document.

More than fifty-seven years have elapsed since a band of patriots convened in this place, to devise measures for the deliverance of this country from a foreign yoke. The corner-stone upon which they founded the Temple of Freedom was broadly this—“that all men are created equal; and they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, LIBERTY, and the pursuit of happiness.” At the sound of their trumpet-call, three millions of people rose up as from the sleep of death, and rushed to the strife of blood; deeming it more glorious to die instantly as freemen, than desirable to live one hour as slaves. They were few in number—poor in resources; but the honest conviction that Truth, Justice, and Right were on their side, made them invincible.

We have met together for the achievement of an enterprise, without which that of our fathers is incomplete...Their grievances, great as they were, were trifling in comparison with the wrongs and sufferings of those for whom we plead. Our fathers were never slaves—never bought and sold like cattle—never shut out from the light of knowledge and religion—never subjected to the lash of brutal taskmasters.

But those for whose emancipation we are striving—constituting, at the present time, at least one-sixth part of our countrymen—are recognized by the law, and treated by their fellow- beings, as marketable commodities, as goods and chattels, as brute beasts; are plundered daily of the fruits of their toil without redress; really enjoying no constitutional nor legal protection from licentious and murderous outrages upon their persons, are ruthlessly torn asunder—the tender babe from the arms of its frantic mother—the heart-broken wife from her weeping husband—at the caprice or pleasure of irresponsible tyrants. For the crime of having a dark complexion, they suffer the pangs of hunger, the infliction of stripes, and the ignominy of brutal servitude. They are kept in heathenish darkness by laws expressly enacted to make their instruction a criminal offence.

These are the prominent circumstances in the condition of more than two millions of our people, the proof of which may be found in thousands of indisputable facts, and in the laws of the slaveholding States.

Hence we maintain,—that in view of the civil and religious privileges of this nation, the guilt of its oppression is unequalled by any other on the face of the earth... We further maintain,—that no man has a right to enslave or imbrute his brother—to hold or acknowledge him, for one moment, as a piece of merchandize—to keep back his hire by fraud—or to brutalize his mind by denying him the means of intellectual, social, and moral improvement.

The right to enjoy liberty is inalienable.

American Anti-Slavery Society. Declaration of sentiments of the American anti-slavery society. Adopted at the formation of said society, in Philadelphia, on the 4th day of December, . New York. Published by the American anti-slavery society, 142 Nassau Street. William S. New York, 1833. Pdf. https://www.loc.gov/item/rbpe.11801100/.

Questions:

More than fifty-seven years have elapsed since a band of patriots convened in this place, to devise measures for the deliverance of this country from a foreign yoke. The corner-stone upon which they founded the Temple of Freedom was broadly this—“that all men are created equal; and they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, LIBERTY, and the pursuit of happiness.” At the sound of their trumpet-call, three millions of people rose up as from the sleep of death, and rushed to the strife of blood; deeming it more glorious to die instantly as freemen, than desirable to live one hour as slaves. They were few in number—poor in resources; but the honest conviction that Truth, Justice, and Right were on their side, made them invincible.

We have met together for the achievement of an enterprise, without which that of our fathers is incomplete...Their grievances, great as they were, were trifling in comparison with the wrongs and sufferings of those for whom we plead. Our fathers were never slaves—never bought and sold like cattle—never shut out from the light of knowledge and religion—never subjected to the lash of brutal taskmasters.

But those for whose emancipation we are striving—constituting, at the present time, at least one-sixth part of our countrymen—are recognized by the law, and treated by their fellow- beings, as marketable commodities, as goods and chattels, as brute beasts; are plundered daily of the fruits of their toil without redress; really enjoying no constitutional nor legal protection from licentious and murderous outrages upon their persons, are ruthlessly torn asunder—the tender babe from the arms of its frantic mother—the heart-broken wife from her weeping husband—at the caprice or pleasure of irresponsible tyrants. For the crime of having a dark complexion, they suffer the pangs of hunger, the infliction of stripes, and the ignominy of brutal servitude. They are kept in heathenish darkness by laws expressly enacted to make their instruction a criminal offence.

These are the prominent circumstances in the condition of more than two millions of our people, the proof of which may be found in thousands of indisputable facts, and in the laws of the slaveholding States.

Hence we maintain,—that in view of the civil and religious privileges of this nation, the guilt of its oppression is unequalled by any other on the face of the earth... We further maintain,—that no man has a right to enslave or imbrute his brother—to hold or acknowledge him, for one moment, as a piece of merchandize—to keep back his hire by fraud—or to brutalize his mind by denying him the means of intellectual, social, and moral improvement.

The right to enjoy liberty is inalienable.

American Anti-Slavery Society. Declaration of sentiments of the American anti-slavery society. Adopted at the formation of said society, in Philadelphia, on the 4th day of December, . New York. Published by the American anti-slavery society, 142 Nassau Street. William S. New York, 1833. Pdf. https://www.loc.gov/item/rbpe.11801100/.

Questions:

- On what occasion was this document written?

- What pronouns are used throughout this document to describe Americans?

- In what capacity are women referenced in this document?

Lucretia Mott: Memoir

Lucretia Mott was a leader in the first wave of feminism in the United States and one of four women present at the inaugural meeting of the AASS. She would go on to form the Pennsylvania Female Anti- Slavery Society four days later and was a leader at the first Women’s Rights Convention in 1848 in Seneca Falls, NY.

At that time I had no idea of the meaning of preambles, and resolutions, and votings. Women had never been in any assemblies of the kind. I had attended only one convention — a convention of colored people — before that; and that was the first time in my life I had ever heard a vote taken. . . . When, a short time after, we came together to form the Female Anti- Slavery Society, there was not a woman capable of taking the chair and organizing that meeting in due order; and we had to call on James McCrummel, a colored man, to give us aid in the work.

Anna Davis Hallowell, ed., James and Lucretia Mott, Life and Letters (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1884), 121.

Questions:

At that time I had no idea of the meaning of preambles, and resolutions, and votings. Women had never been in any assemblies of the kind. I had attended only one convention — a convention of colored people — before that; and that was the first time in my life I had ever heard a vote taken. . . . When, a short time after, we came together to form the Female Anti- Slavery Society, there was not a woman capable of taking the chair and organizing that meeting in due order; and we had to call on James McCrummel, a colored man, to give us aid in the work.

Anna Davis Hallowell, ed., James and Lucretia Mott, Life and Letters (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1884), 121.

Questions:

- Based off of this source was the Abolition movement sexist?

Sarah Grimke: Letter to Angelina Grimke

Concord, Massachusetts

September 6, 1837

My dear sister,

There are few things which present greater obstacles to the improvement and elevation of woman to her appropriate sphere of usefulness and duty, than the laws which have been enacted to destroy her independence, and crush her individuality; laws which, although they are framed for her government, she has had no voice in establishing, and which robe her of some of her essential rights. Woman has no political existence. With the single exception of presenting a petition to the legislative body, she is a cipher in the nation; or, if not actually so in representative governments, she is only counted, like the slaves of the South, to swell the number of law-makers who form decrees for her government, with little reference to her benefit, except so far as her good may promote their own. . .

Here now, the very being of woman, like that of a slave, is absorbed in her master. All contracts made with her, like those made with slaves by their owners, are a mere nullity. Our kind defenders have legislated away almost all of our legal rights, and in the true spirit of such injustice and oppression,, have kept us in ignorance of those very laws by which we are governed. They have persuaded us, that we have no right to investigate the laws, and that, if we did, we could not comprehend them. . . .

What a mortifying proof this law affords, of the estimation in which woman is held! She is placed completely in the hands of a being subject like herself to the outbursts of passion, and therefore unworthy to be trusted with power. Perhaps I may be told respecting this law, that it is a dead letter, as I am sometimes told about the slave laws; but this is not true in either case. The slaveholder does kill his slave by moderate correction, as the law allows; and many a husband among the poor, exercises the right given him by the law, of degrading woman by personal chastisement. And among the higher ranks, if actual imprisonment is not resorted to, women are not unfrequently restrained of the liberty of going to places of worship by irreligious husbands, and of doing many other things about which, as moral and responsible beings, they should be the sole judges. . . .

I do not wish by any means to intimate that the condition of free women can be compared to that of slaves in suffering, or in degradation; still, I believe the laws which deprive married women of their rights and privileges, have a tendency to lessen them in their own estimation as moral and responsible beings, and that their being made by civil law inferior to their husbands, had a debasing and mischievous effect upon them, teaching them practically the fatal lesson to look unto man for protection and indulgence. . . Hoping that in the various reformations of the day, women may be relieved from some of their legal disabilities, I remain,

Thine in the bonds of womanhood,

Sarah M. Grimké

Sarah M. Grimké, Letters on the Equality of the Sexes and the Condition of Women, addressed to Mary S. Parker (Boston: Isaac Knapp, 1838), 74-83.

Questions:

September 6, 1837

My dear sister,

There are few things which present greater obstacles to the improvement and elevation of woman to her appropriate sphere of usefulness and duty, than the laws which have been enacted to destroy her independence, and crush her individuality; laws which, although they are framed for her government, she has had no voice in establishing, and which robe her of some of her essential rights. Woman has no political existence. With the single exception of presenting a petition to the legislative body, she is a cipher in the nation; or, if not actually so in representative governments, she is only counted, like the slaves of the South, to swell the number of law-makers who form decrees for her government, with little reference to her benefit, except so far as her good may promote their own. . .

Here now, the very being of woman, like that of a slave, is absorbed in her master. All contracts made with her, like those made with slaves by their owners, are a mere nullity. Our kind defenders have legislated away almost all of our legal rights, and in the true spirit of such injustice and oppression,, have kept us in ignorance of those very laws by which we are governed. They have persuaded us, that we have no right to investigate the laws, and that, if we did, we could not comprehend them. . . .

What a mortifying proof this law affords, of the estimation in which woman is held! She is placed completely in the hands of a being subject like herself to the outbursts of passion, and therefore unworthy to be trusted with power. Perhaps I may be told respecting this law, that it is a dead letter, as I am sometimes told about the slave laws; but this is not true in either case. The slaveholder does kill his slave by moderate correction, as the law allows; and many a husband among the poor, exercises the right given him by the law, of degrading woman by personal chastisement. And among the higher ranks, if actual imprisonment is not resorted to, women are not unfrequently restrained of the liberty of going to places of worship by irreligious husbands, and of doing many other things about which, as moral and responsible beings, they should be the sole judges. . . .

I do not wish by any means to intimate that the condition of free women can be compared to that of slaves in suffering, or in degradation; still, I believe the laws which deprive married women of their rights and privileges, have a tendency to lessen them in their own estimation as moral and responsible beings, and that their being made by civil law inferior to their husbands, had a debasing and mischievous effect upon them, teaching them practically the fatal lesson to look unto man for protection and indulgence. . . Hoping that in the various reformations of the day, women may be relieved from some of their legal disabilities, I remain,

Thine in the bonds of womanhood,

Sarah M. Grimké

Sarah M. Grimké, Letters on the Equality of the Sexes and the Condition of Women, addressed to Mary S. Parker (Boston: Isaac Knapp, 1838), 74-83.

Questions:

- Based off of this source, do you think the Abolition movement was sexist?

Charlotte Forten: Diary

Charlotte Forten was the wife of Sarah and Angelina Grimke’s nephew, a man of mixed race after their brother Henry Grimke had sexual relations with a woman he enslaved, Henry’s mother. Charlotte Forten Grimke worked as a teacher and was the first Black graduate of the Salem School.

June 18, 1856. Amazing, wonderful news I have heard to-day! it has completely astounded me. I cannot realize it.—Mr. Edwards [principal] called me into his room with a face full of such grave mystery, that I at once commenced reviewing my past conduct, and wondering what terrible misdeed I,—a very “model of deportment” had committed within the precincts of our Normal [school] world. The mystery was most pleasantly solved. I have received the offer of a situation as teacher in one of the public schools of this city,—of this conservative, aristocratic old city of Salem!!! Wonderful indeed it is! I know that it is principally through the exertions of my kind teacher, although he will not acknowledge it.—I thank him with all my heart. I had a long talk with the Principal of the school, whom I like much. Again and again I ask myself—‘Can it be true?’ It seems impossible. I shall commence to-morrow.—19 June 19, 1856. To-day, a rainy and gloomy one I have devoted to my new duties. Of course I cannot decide how I like them yet.—I thought it best to commence immediately, although the term has not quite closed. I could not write about it yesterday, the last day of my school-life. Yet I cannot think it quite over until after the examination, in which Mr. Edwards has kindly arranged that I shall take part...

Jan. 18, 1857. Dined with Mr. and Mrs. P[utnam]. We talked of the wrongs and sufferings on our race. Mr. P[utnam] thought me too sensitive.—But oh, how inexpressibly bitter and agonizing it is to feel oneself an outcast from the rest of mankind, as we are in this country! To me it is dreadful, dreadful. Were I to indulge in the thought I fear I should become insane. But I do not despair. I will not despair; though very often I can hardly help doing so. God help us! We are indeed a wretched people. Oh, that I could do much towards bettering our condition. I will do all, all the very little that lies in my power, while life and strength last!

Forten, Charlotte. Journal of Charlotte Forten. National Humanities Center: Making of African American Identity. http://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/pds/maai/identity/text3/charlottefortenjournal.pdf.

Questions:

June 18, 1856. Amazing, wonderful news I have heard to-day! it has completely astounded me. I cannot realize it.—Mr. Edwards [principal] called me into his room with a face full of such grave mystery, that I at once commenced reviewing my past conduct, and wondering what terrible misdeed I,—a very “model of deportment” had committed within the precincts of our Normal [school] world. The mystery was most pleasantly solved. I have received the offer of a situation as teacher in one of the public schools of this city,—of this conservative, aristocratic old city of Salem!!! Wonderful indeed it is! I know that it is principally through the exertions of my kind teacher, although he will not acknowledge it.—I thank him with all my heart. I had a long talk with the Principal of the school, whom I like much. Again and again I ask myself—‘Can it be true?’ It seems impossible. I shall commence to-morrow.—19 June 19, 1856. To-day, a rainy and gloomy one I have devoted to my new duties. Of course I cannot decide how I like them yet.—I thought it best to commence immediately, although the term has not quite closed. I could not write about it yesterday, the last day of my school-life. Yet I cannot think it quite over until after the examination, in which Mr. Edwards has kindly arranged that I shall take part...

Jan. 18, 1857. Dined with Mr. and Mrs. P[utnam]. We talked of the wrongs and sufferings on our race. Mr. P[utnam] thought me too sensitive.—But oh, how inexpressibly bitter and agonizing it is to feel oneself an outcast from the rest of mankind, as we are in this country! To me it is dreadful, dreadful. Were I to indulge in the thought I fear I should become insane. But I do not despair. I will not despair; though very often I can hardly help doing so. God help us! We are indeed a wretched people. Oh, that I could do much towards bettering our condition. I will do all, all the very little that lies in my power, while life and strength last!

Forten, Charlotte. Journal of Charlotte Forten. National Humanities Center: Making of African American Identity. http://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/pds/maai/identity/text3/charlottefortenjournal.pdf.

Questions:

- What does Forten-Grimke do for a living?

- How is she treated by Mr. Putnam?

Martha Morris: Sale of Home to Maria Battiste

December 31, 1845

Before me, notary public, appeared Miss Martha Morris “ who declared and acknowledged that for and in consideration of the sum of $700 payable by Maria Battiste, a free woman of color, cash in hand paid the receipt of which is hereby acknowledged... has this day given, granted, bargained, sold, transferred, aliened, conveyed, set over and delivered, and by these present doth give, grant, bargain, sell, transfer, alien, convey, set over and deliver unto the said Maria Battiste the following described property.”

Sale, Martha Morris to Maria Battiste, Book I, page 183, December 31, 1845, Conveyance Records, West Feliciana Parish, Louisiana.

Questions:

Before me, notary public, appeared Miss Martha Morris “ who declared and acknowledged that for and in consideration of the sum of $700 payable by Maria Battiste, a free woman of color, cash in hand paid the receipt of which is hereby acknowledged... has this day given, granted, bargained, sold, transferred, aliened, conveyed, set over and delivered, and by these present doth give, grant, bargain, sell, transfer, alien, convey, set over and deliver unto the said Maria Battiste the following described property.”

Sale, Martha Morris to Maria Battiste, Book I, page 183, December 31, 1845, Conveyance Records, West Feliciana Parish, Louisiana.

Questions:

- What does this document show about the work of a free Black woman in Louisiana?

Theodore Weld: Letter to Sarah and Angelina Grimké, 1837

Theodore Weld was a fellow abolitionist and later married Angelina Grimké. He wrote this letter to the sisters while they were out on speaking tour. He was doubtful that they would be effective.

My dear sisters

I had it in my heart to make a suggestion to you in my last letter about your course touching the “rights of women”, but it was crowded out by other matters perhaps of less importance...

As to the rights and wrongs of women, it is an old theme with me. It was the first subject I ever discussed. In a little debating society when a boy, I took the ground that sex neither qualified nor disqualified for the discharge of any functions mental, moral or spiritual; that there is no reason why woman should not make laws, administer justice, sit in the chair of state, plead at the bar or in the pulpit, if she has the qualifications, just as much as tho she belonged to the other sex... Now as I have never found man, woman or child who agreed with me in the “ultraism” of woman’s rights... What I advocated in boyhood I advocate now, that woman in EVERY particular shares equally with man rights and responsibilities... Now notwithstanding this, I do most deeply regret that you have begun a series of articles in the Papers on the rights of woman. Why, my dear sisters, the best possible advocacy which you can make is just what you are making day by day. Thousands hear you every week who have all their lives held that woman must not speak in public. Such a practical refutation of the dogma as your speaking furnishes has already converted multitudes... Besides you are Southerners, have been slaveholders; your dearest friends are all in the sin and shame and peril. All these things give you great access to northern mind, great sway over it...You can do more at convincing the north than twenty northern females, tho’ they could speak as well as you. Now this peculiar advantage you lose the moment you take another subject...

Let us all first wake up the nation to lift millions of slaves of both sexes from the dust, and turn them into MEN and then when we all have our hand in, it will be an easy matter to take millions of females from their knees and set them on their feet, or in other words transform them from babies into women... I pray our dear Lord to give you wisdom and grace and help and bless you forever.

Your brother T. D. Weld

*ultraism: holding of extreme opinions

Weld, Theodore. “The Letters of Theodore Weld, Angelina Grimké Weld and Sarah M. Grimké, 1822−1844.” New York: Da Capo Press, 1970. 425−432.

Questions:

My dear sisters

I had it in my heart to make a suggestion to you in my last letter about your course touching the “rights of women”, but it was crowded out by other matters perhaps of less importance...

As to the rights and wrongs of women, it is an old theme with me. It was the first subject I ever discussed. In a little debating society when a boy, I took the ground that sex neither qualified nor disqualified for the discharge of any functions mental, moral or spiritual; that there is no reason why woman should not make laws, administer justice, sit in the chair of state, plead at the bar or in the pulpit, if she has the qualifications, just as much as tho she belonged to the other sex... Now as I have never found man, woman or child who agreed with me in the “ultraism” of woman’s rights... What I advocated in boyhood I advocate now, that woman in EVERY particular shares equally with man rights and responsibilities... Now notwithstanding this, I do most deeply regret that you have begun a series of articles in the Papers on the rights of woman. Why, my dear sisters, the best possible advocacy which you can make is just what you are making day by day. Thousands hear you every week who have all their lives held that woman must not speak in public. Such a practical refutation of the dogma as your speaking furnishes has already converted multitudes... Besides you are Southerners, have been slaveholders; your dearest friends are all in the sin and shame and peril. All these things give you great access to northern mind, great sway over it...You can do more at convincing the north than twenty northern females, tho’ they could speak as well as you. Now this peculiar advantage you lose the moment you take another subject...

Let us all first wake up the nation to lift millions of slaves of both sexes from the dust, and turn them into MEN and then when we all have our hand in, it will be an easy matter to take millions of females from their knees and set them on their feet, or in other words transform them from babies into women... I pray our dear Lord to give you wisdom and grace and help and bless you forever.

Your brother T. D. Weld

*ultraism: holding of extreme opinions

Weld, Theodore. “The Letters of Theodore Weld, Angelina Grimké Weld and Sarah M. Grimké, 1822−1844.” New York: Da Capo Press, 1970. 425−432.

Questions:

- What is Weld most concerned with? See the underlined line. Why?

Sarah and Angelina Grimké: Letter to Weld and Whittier, 1837

Brethren beloved in the Lord.

As your letters came to hand at the same time and both are devoted mainly to the same subject we have concluded to answer them on one sheet and jointly. You seem greatly alarmed at the idea of our advocating the rights of woman ...These letters have not been the means of arousing the public attention to the subject of Womans rights, it was the Pastoral Letter which did the mischief... This Letter then roused the attention of the whole country to enquire what right we had to open our mouths for the dumb; the people were continually told “it is a shame for a woman to speak in the churches.” Paul suffered not a woman to teach but commanded her to be in silence. The pulpit is too sacred a place for woman’s foot etc. Now my dear brothers this invasion of our rights was just such an attack upon us, as that made upon Abolitionists generally when they were told a few years ago that they had no right to discuss the subject of Slavery. Did you take no notice of this assertion? Why no! With one heart and one voice you said, We will settle this right before we go one step further. The time to assert a right is the time when that right is denied. We must establish this right for if we do not, it will be impossible for us to go on with the work of Emancipation ...

And can you not see that women could do, and would do a hundred times more for the slave if she were not fettered? Why! we are gravely told that we are out of our sphere even when we circulate petitions; out of our “appropriate sphere” when we speak to women only; and out of them when we sing in the churches. Silence is our province, submission our duty. If then we “give no reason for the hope that is in us”, that we have equal rights with our brethren, how can we expect to be permitted much longer to exercise those rights?... If we are to do any good in the Anti Slavery cause, our right to labor in it must be firmly established...What then can woman do for the slave when she is herself under the feet of man and shamed into silence? ...

With regard to brother Welds ultraism on the subject of marriage, he is quite mistaken if he fancies he has got far ahead of us in the human rights reform. We do not think his doctrine at all shocking: it is altogether right...

May the Lord bless you my dear brothers...

A. E. G.

[P.S.] We never mention women’s rights in our lectures except so far as is necessary to urge them to meet their responsibilities...

Weld, Theodore. “The Letters of Theodore Weld, Angelina Grimké Weld and Sarah M. Grimké, 1822−1844.” New York: Da Capo Press, 1970. 425−432.

Questions:

As your letters came to hand at the same time and both are devoted mainly to the same subject we have concluded to answer them on one sheet and jointly. You seem greatly alarmed at the idea of our advocating the rights of woman ...These letters have not been the means of arousing the public attention to the subject of Womans rights, it was the Pastoral Letter which did the mischief... This Letter then roused the attention of the whole country to enquire what right we had to open our mouths for the dumb; the people were continually told “it is a shame for a woman to speak in the churches.” Paul suffered not a woman to teach but commanded her to be in silence. The pulpit is too sacred a place for woman’s foot etc. Now my dear brothers this invasion of our rights was just such an attack upon us, as that made upon Abolitionists generally when they were told a few years ago that they had no right to discuss the subject of Slavery. Did you take no notice of this assertion? Why no! With one heart and one voice you said, We will settle this right before we go one step further. The time to assert a right is the time when that right is denied. We must establish this right for if we do not, it will be impossible for us to go on with the work of Emancipation ...

And can you not see that women could do, and would do a hundred times more for the slave if she were not fettered? Why! we are gravely told that we are out of our sphere even when we circulate petitions; out of our “appropriate sphere” when we speak to women only; and out of them when we sing in the churches. Silence is our province, submission our duty. If then we “give no reason for the hope that is in us”, that we have equal rights with our brethren, how can we expect to be permitted much longer to exercise those rights?... If we are to do any good in the Anti Slavery cause, our right to labor in it must be firmly established...What then can woman do for the slave when she is herself under the feet of man and shamed into silence? ...

With regard to brother Welds ultraism on the subject of marriage, he is quite mistaken if he fancies he has got far ahead of us in the human rights reform. We do not think his doctrine at all shocking: it is altogether right...

May the Lord bless you my dear brothers...

A. E. G.

[P.S.] We never mention women’s rights in our lectures except so far as is necessary to urge them to meet their responsibilities...

Weld, Theodore. “The Letters of Theodore Weld, Angelina Grimké Weld and Sarah M. Grimké, 1822−1844.” New York: Da Capo Press, 1970. 425−432.

Questions:

- Why does Grimké feel she needs to speak on women's rights first?

Catherine Beecher: Memoir

Catharine Beecher, the older sister of Harriet Beecher Stowe, was an avid writer and reformer. She opposed the Grimke sisters' public speaking efforts.

My Dear Friend ...

It is the grand feature of the Divine economy, that there should be different stations of superiority and subordination, and it is impossible to annihilate this beneficent and immutable law... In this arrangement of the duties of life, Heaven has appointed to one sex the superior, and to the other the subordinate station, and this without any reference to the character or conduct of either. It is therefore as much for the dignity as it is for the interest of females, in all respects to conform to the duties of this relation. And it is as much a duty as it is for the child to fulfil [sic] similar relations to parents, or subjects to rulers. But while woman holds a subordinate relation in society to the other sex, it is not because it was designed that her duties or her influence should be any the less important, or all−pervading...

Woman is to win every thing by peace and love; by making herself so much respected, esteemed and loved, that to yield to her opinions and to gratify her wishes will be the free−will offering of the heart... But the moment woman begins to feel the promptings of ambition, or the thirst for power, her [protection] is gone...

Whatever... throws a woman into the attitude of a combatant... throws her out of her appropriate sphere. If these general principles are correct, they are entirely opposed to the plan of arraying females in any Abolition movement: because it enlists them in an effort... it brings them forward as partisans in a conflict that has been begun and carried forward by measures that are any thing rather than peaceful in their tendencies; because it draws them forth from their appropriate retirement, to expose themselves to the ungoverned violence of mobs, and to sneers and ridicule in public places; because it leads them into the arena of political collision, not as peaceful mediators to hush the opposing elements, but as combatants...

If petitions from females will operate to exasperate... if they will increase, rather than diminish the evil which it is wished to remove; if they will be the opening wedge, that will tend eventually to bring females as petitioners and partisans into every political measure that may tend to injure and oppress their sex... then it is neither appropriate nor wise, nor right, for a woman to petition for the relief of oppressed females...

In this country, petitions to congress, in reference to the official duties of legislators, seem, IN ALL CASES, to fall entirely[outside] the sphere of female duty.

Beecher, Catherine. "An Essay on Slavery and Abolitionism, in Reference to the Duty of American Females." Philadelphia: Henry Perkins, 1837. 96−107.

Questions:

My Dear Friend ...

It is the grand feature of the Divine economy, that there should be different stations of superiority and subordination, and it is impossible to annihilate this beneficent and immutable law... In this arrangement of the duties of life, Heaven has appointed to one sex the superior, and to the other the subordinate station, and this without any reference to the character or conduct of either. It is therefore as much for the dignity as it is for the interest of females, in all respects to conform to the duties of this relation. And it is as much a duty as it is for the child to fulfil [sic] similar relations to parents, or subjects to rulers. But while woman holds a subordinate relation in society to the other sex, it is not because it was designed that her duties or her influence should be any the less important, or all−pervading...

Woman is to win every thing by peace and love; by making herself so much respected, esteemed and loved, that to yield to her opinions and to gratify her wishes will be the free−will offering of the heart... But the moment woman begins to feel the promptings of ambition, or the thirst for power, her [protection] is gone...

Whatever... throws a woman into the attitude of a combatant... throws her out of her appropriate sphere. If these general principles are correct, they are entirely opposed to the plan of arraying females in any Abolition movement: because it enlists them in an effort... it brings them forward as partisans in a conflict that has been begun and carried forward by measures that are any thing rather than peaceful in their tendencies; because it draws them forth from their appropriate retirement, to expose themselves to the ungoverned violence of mobs, and to sneers and ridicule in public places; because it leads them into the arena of political collision, not as peaceful mediators to hush the opposing elements, but as combatants...

If petitions from females will operate to exasperate... if they will increase, rather than diminish the evil which it is wished to remove; if they will be the opening wedge, that will tend eventually to bring females as petitioners and partisans into every political measure that may tend to injure and oppress their sex... then it is neither appropriate nor wise, nor right, for a woman to petition for the relief of oppressed females...

In this country, petitions to congress, in reference to the official duties of legislators, seem, IN ALL CASES, to fall entirely[outside] the sphere of female duty.

Beecher, Catherine. "An Essay on Slavery and Abolitionism, in Reference to the Duty of American Females." Philadelphia: Henry Perkins, 1837. 96−107.

Questions:

- Why does she feel women's role is special?

- What concerns her about public speaking and women's rights?

Sarah Moore Grimké: Series Of Letters

Sarah Grimke published the following series of letters in 1837 in order to further promote her ideas.

LETTER III. THE PASTORAL LETTER OF THE GENERAL ASSOCIATION OF CONGREGATIONAL MINISTERS OF MASSACHUSETTS. No one can desire more earnestly than I do, that woman may move exactly in the sphere which her Creator has assigned her; and I believe her having been displaced from that sphere has introduced confusion into the world... The New Testament has been referred to [as justifying the inferiority of women], and I am willing to abide by its decision, but must enter my protest against the false translation of some passages by the MEN who did that work...

‘Her influence is the source of mighty power.’ This has ever been the flattering language of man since he laid aside the whip as a means to keep woman in subjection. He spares her body; but the war he has waged against her mind, her heart, and her soul, has been no less destructive to her as a moral being. How monstrous, how anti-christian, is the doctrine that woman is to be dependent on man! Where, in all the sacred Scriptures, is this taught? Alas, she has too well learned the lesson which MAN has labored to teach her. She has surrendered her dearest RIGHTS, and been satisfied with the privileges which man has assumed to grant her...

LETTER X. INTELLECT OF WOMAN. It will scarcely be denied, I presume, that, as a general rule, men do not desire the improvement of women. There are few instances of men who are magnanimous enough to be entirely willing that women should know more than themselves, on any subjects except dress and cookery; and, indeed, this necessarily flows from their assumption of superiority...

LETTER XII. LEGAL DISABILITIES OF WOMEN. Woman has no political existence... That the laws which have been generally adopted in the United States, for the government of women, have been framed almost entirely for the exclusive benefit of men, and with a design to oppress women, by depriving them of all control over their property... Men frame the laws, and, with few exceptions, claim to execute them on both sexes... Although looked upon as an inferior, when considered as an intellectual being, woman is punished with the same severity as man, when she is guilty of moral offences...

Thine in the bonds of womanhood, SARAH M. GRIMKÉ

Sarah M. Grimké, Letters on the Equality of the Sexes, and the Condition of Woman (Boston: Isaac Knapp, 1838), 12, 15-17, 23, 27, 33, 40-41, 45, 54-55, 61, 74, 81, 83, 86- 87, 121-123.

Questions:

LETTER III. THE PASTORAL LETTER OF THE GENERAL ASSOCIATION OF CONGREGATIONAL MINISTERS OF MASSACHUSETTS. No one can desire more earnestly than I do, that woman may move exactly in the sphere which her Creator has assigned her; and I believe her having been displaced from that sphere has introduced confusion into the world... The New Testament has been referred to [as justifying the inferiority of women], and I am willing to abide by its decision, but must enter my protest against the false translation of some passages by the MEN who did that work...

‘Her influence is the source of mighty power.’ This has ever been the flattering language of man since he laid aside the whip as a means to keep woman in subjection. He spares her body; but the war he has waged against her mind, her heart, and her soul, has been no less destructive to her as a moral being. How monstrous, how anti-christian, is the doctrine that woman is to be dependent on man! Where, in all the sacred Scriptures, is this taught? Alas, she has too well learned the lesson which MAN has labored to teach her. She has surrendered her dearest RIGHTS, and been satisfied with the privileges which man has assumed to grant her...

LETTER X. INTELLECT OF WOMAN. It will scarcely be denied, I presume, that, as a general rule, men do not desire the improvement of women. There are few instances of men who are magnanimous enough to be entirely willing that women should know more than themselves, on any subjects except dress and cookery; and, indeed, this necessarily flows from their assumption of superiority...

LETTER XII. LEGAL DISABILITIES OF WOMEN. Woman has no political existence... That the laws which have been generally adopted in the United States, for the government of women, have been framed almost entirely for the exclusive benefit of men, and with a design to oppress women, by depriving them of all control over their property... Men frame the laws, and, with few exceptions, claim to execute them on both sexes... Although looked upon as an inferior, when considered as an intellectual being, woman is punished with the same severity as man, when she is guilty of moral offences...

Thine in the bonds of womanhood, SARAH M. GRIMKÉ

Sarah M. Grimké, Letters on the Equality of the Sexes, and the Condition of Woman (Boston: Isaac Knapp, 1838), 12, 15-17, 23, 27, 33, 40-41, 45, 54-55, 61, 74, 81, 83, 86- 87, 121-123.

Questions:

- What topics on women's rights does Grimké tackle?

Margarett Fuller: Woman In The Nineteenth Century

Margarett Fuller was a writer and an editor. In the 1840’s she was an editor for the Transcendentalist journal, Dial. In the July 1843 issue she wrote an article titled "The Great Lawsuit: Man Versus Men: Woman Versus Women." This piece is considered a classic among feminist literature. The larger version discusses controversial topics such as prostitution and slavery, marriage, employment, and reform.

Much has been written about woman's keeping within her sphere, which is defined as the domestic sphere. As a little girl she is to learn the lighter family duties, while she acquires that limited acquaintance with the realm of literature and science that will enable her to superintend the instruction of children in their earliest years. It is not generally proposed that she should be sufficiently instructed and developed to understand the pursuits or aims of her future husband; she is not to be a help-meet to him in the way of companionship and counsel, except in the care of his house and children. Her youth is to be passed partly in learning to keep house and the use of the needle, partly in the social circle, where her manners may be formed, ornamental accomplishments perfected and displayed, and the husband found who shall give her the domestic sphere for which she is exclusively to be prepared.