9. 0CE: One Male God over Women

|

Monotheism was a liberating and uniting force in most of the western world. This section explores Judaism and Christianity and what they said about women, as well as explores the lives of the founders and the women who are all over those origin stories. As we are focusing on the impact of these faiths on women's status, this section can seem a bit critical, but remember the social experiences of women in faith are different from their spiritual ones, and despite some of the ways women may have been discriminated against, women from all walks of life flocked toward monotheism.

|

|

The Goddess Ishtar of Mesopotamia, Public Domain

The Goddess Ishtar of Mesopotamia, Public Domain

In the ancient world, many religions included prominent goddess traditions, attributing to goddesses the creation of the world and its ongoing survival. Many polytheistic faiths such as Hinduism presented the idea of a Divine Feminine, that God, or the Ultimate Being, was either completely without gender or had an equal feminine dimension. This view of a feminine God or goddesses was challenged, however, by the rise of the monotheistic and patriarchal Abrahamic religions of Judaism, Christianity and Islam, all born in the Middle East.

And while the idea of divine feminine takes a back seat, it’s important not to understate how patriarchal pagan societies were–pagan life was certainly not a golden age for women.

The Holy Scriptures of these faiths– the Torah, the remaining books of the Old Testament, the New Testament, and the Quran, consistently referred to the divine with masculine pronouns and are awash with male titles and images of God such as Lord, Father, or King, Brah. They lead to the equation of God with not just the male gender, but also with traditional concepts of masculinity and male power. In this section, we will explore the complex place of women within monotheistic traditions and how their spiritual and social equality has been both enhanced and hampered by their faith.

And while the idea of divine feminine takes a back seat, it’s important not to understate how patriarchal pagan societies were–pagan life was certainly not a golden age for women.

The Holy Scriptures of these faiths– the Torah, the remaining books of the Old Testament, the New Testament, and the Quran, consistently referred to the divine with masculine pronouns and are awash with male titles and images of God such as Lord, Father, or King, Brah. They lead to the equation of God with not just the male gender, but also with traditional concepts of masculinity and male power. In this section, we will explore the complex place of women within monotheistic traditions and how their spiritual and social equality has been both enhanced and hampered by their faith.

"The Fall of Man" by Peter Paul Rubens, Public Domain

"The Fall of Man" by Peter Paul Rubens, Public Domain

One Male God

From around the 5th century BCE to the 7th century CE, the view of a singular male god was solidified in western culture through a thousand years of monotheistic tradition in which all the major prophets whose works we know were men. These faiths share many views on women, such as the impurity of menstruation, the need for some degree of male control over women (and in particular female sexuality), and an apparent condoning of economic and social reliance on men, even where the genders may be considered spiritual equals. These constraints all relate to the perceived purpose of women–to bear and raise children. It was all about the continuation of the male family line.

Original Sin The Hebrew Bible is an early Abrahamic account of world events. Many stories within the Hebrew Bible are corroborated by other texts such as the Epic of Gilgamesh, which discusses a great flood similar to that of Noah’s story, making it hard to ignore as both a religious and historical text. Two books of the Hebrew Bible, Ruth and Esther, tell women’s stories and have women’s names. Although many women are featured in the Hebrew Bible, none of the confirmed authors are known to have been women, although, there are theories that some of them may have been female.

It begins with the story of Creation, where the idea of a strictly male monotheism is evident. God creates a garden and then Adam or literally, “Man.” The scriptures say he is made in God’s own image, solidifying the view of God as a male (despite assertions elsewhere that God is beyond human concepts such as gender). From Adam’s rib, Eve, the first woman, is created. God tells them not to eat from the tree of knowledge in the Garden, but Eve is corrupted by a snake and eats from the tree, subsequently convincing Adam to do so too. They become “knowledgeable,” the meaning of which has been debated for milenia, and they see their nakedness. God is furious. In the Christian interpretation, Eve is deemed singularly responsible for the fall of humankind and humans’ expulsion from the Garden because she was tempted by the devil to eat the forbidden fruit. In the 400s, this story was interpreted by Augustine of Hippo, who introduced the Christian concept of Original Sin. Some interpret it to mean that women were uniquely vulnerable to the temptation of sin.

When later Christians compiled the books of the Bible, they destroyed as blasphemy a collection of books, today known as the Gnostic Gospels. Today, the Gnostic Gospels are regarded as an alternative set of books that reveal the story of creation and early humans. They show the diversity of early Christian thinking. These works had a different rendition of the story of Adam and Eve: the snake is not evil, it represents divine wisdom. The snake “convinces Adam and Eve to partake of knowledge while ‘the Lord’ threatens them with death, trying jealously to prevent them from attaining knowledge and expelling them from Paradise when they achieve it.” In another Gnostic text, Thunder, Perfect Mind,” a feminine voice, often used to represent complex ideas, states:

For I am the first and the last.

I am the honored one and the scorned one.

I am the whore and the holy one.

I am the wife and the virgin....

I am the barren one, and many are her sons....

I am the silence that is incomprehensible....

I am the utterance of my name.

None of these scholars were likely women.

From around the 5th century BCE to the 7th century CE, the view of a singular male god was solidified in western culture through a thousand years of monotheistic tradition in which all the major prophets whose works we know were men. These faiths share many views on women, such as the impurity of menstruation, the need for some degree of male control over women (and in particular female sexuality), and an apparent condoning of economic and social reliance on men, even where the genders may be considered spiritual equals. These constraints all relate to the perceived purpose of women–to bear and raise children. It was all about the continuation of the male family line.

Original Sin The Hebrew Bible is an early Abrahamic account of world events. Many stories within the Hebrew Bible are corroborated by other texts such as the Epic of Gilgamesh, which discusses a great flood similar to that of Noah’s story, making it hard to ignore as both a religious and historical text. Two books of the Hebrew Bible, Ruth and Esther, tell women’s stories and have women’s names. Although many women are featured in the Hebrew Bible, none of the confirmed authors are known to have been women, although, there are theories that some of them may have been female.

It begins with the story of Creation, where the idea of a strictly male monotheism is evident. God creates a garden and then Adam or literally, “Man.” The scriptures say he is made in God’s own image, solidifying the view of God as a male (despite assertions elsewhere that God is beyond human concepts such as gender). From Adam’s rib, Eve, the first woman, is created. God tells them not to eat from the tree of knowledge in the Garden, but Eve is corrupted by a snake and eats from the tree, subsequently convincing Adam to do so too. They become “knowledgeable,” the meaning of which has been debated for milenia, and they see their nakedness. God is furious. In the Christian interpretation, Eve is deemed singularly responsible for the fall of humankind and humans’ expulsion from the Garden because she was tempted by the devil to eat the forbidden fruit. In the 400s, this story was interpreted by Augustine of Hippo, who introduced the Christian concept of Original Sin. Some interpret it to mean that women were uniquely vulnerable to the temptation of sin.

When later Christians compiled the books of the Bible, they destroyed as blasphemy a collection of books, today known as the Gnostic Gospels. Today, the Gnostic Gospels are regarded as an alternative set of books that reveal the story of creation and early humans. They show the diversity of early Christian thinking. These works had a different rendition of the story of Adam and Eve: the snake is not evil, it represents divine wisdom. The snake “convinces Adam and Eve to partake of knowledge while ‘the Lord’ threatens them with death, trying jealously to prevent them from attaining knowledge and expelling them from Paradise when they achieve it.” In another Gnostic text, Thunder, Perfect Mind,” a feminine voice, often used to represent complex ideas, states:

For I am the first and the last.

I am the honored one and the scorned one.

I am the whore and the holy one.

I am the wife and the virgin....

I am the barren one, and many are her sons....

I am the silence that is incomprehensible....

I am the utterance of my name.

None of these scholars were likely women.

"Abraham, Sarah, and the Angel" by Jan Provoost, Wikimedia Commons

"Abraham, Sarah, and the Angel" by Jan Provoost, Wikimedia Commons

Judaism

Gender differences found in Hebrew literature suggest women were subordinate to men in ancient Jewish tradition. In fact the first book, Genesis, is often called “God’s curse to womankind.” One example of women’s subservience to men appears in the story of Judaism’s founder, Abraham, a man from Ur, who accepts that there is only one true God. As in most patriarchal cultures, his wife Sarah follows him on his spiritual journey.

It was essential for the patriarch to have an heir, so it was very common in ancient cultures of the Fertile Crescent for men to take on concubines, or secondary wives, even at the request of the primary wife. The stability of the family relied upon a new generation. Sarah was worried that Abraham would have no heir with her, so she gave him an enslaved woman named Hagar to produce a male heir. In the story, God hadn’t intended this– he wanted Abraham to have a child with his wife. Because of her selflessness, Sarah becomes the first person in the Bible to have a healing– God allows her to become pregnant and produce a male child, Isaac.

In the Book of Genesis, we learn that Abraham betrays his wife to save his own skin.. A famine causes the couple to be refugees and Abraham worried that his beautiful wife would be a prize Egyptians would like. He begs her to pretend to be his sister so they won’t kill him to get her. The Pharaoh finds her desirable and she becomes his concubine, rewarding her “brother” with wealth. Abraham saved his own skin at the expense of his wife. Abraham pulls the same trick with their next host, the king Abemelek of Gerar. God spoke to the king and told him to return Sarah to her husband, and until he did so no woman of Abemelek’s court would conceive. Despite Abraham being responsible for the lies, only Sarah is blamed for the misfortune of all these women: “For the Lord had closed fast all the wombs of the house… because of Sarah, Abraham’s wife.” Abraham threw Sarah under the chariot.

Gender differences found in Hebrew literature suggest women were subordinate to men in ancient Jewish tradition. In fact the first book, Genesis, is often called “God’s curse to womankind.” One example of women’s subservience to men appears in the story of Judaism’s founder, Abraham, a man from Ur, who accepts that there is only one true God. As in most patriarchal cultures, his wife Sarah follows him on his spiritual journey.

It was essential for the patriarch to have an heir, so it was very common in ancient cultures of the Fertile Crescent for men to take on concubines, or secondary wives, even at the request of the primary wife. The stability of the family relied upon a new generation. Sarah was worried that Abraham would have no heir with her, so she gave him an enslaved woman named Hagar to produce a male heir. In the story, God hadn’t intended this– he wanted Abraham to have a child with his wife. Because of her selflessness, Sarah becomes the first person in the Bible to have a healing– God allows her to become pregnant and produce a male child, Isaac.

In the Book of Genesis, we learn that Abraham betrays his wife to save his own skin.. A famine causes the couple to be refugees and Abraham worried that his beautiful wife would be a prize Egyptians would like. He begs her to pretend to be his sister so they won’t kill him to get her. The Pharaoh finds her desirable and she becomes his concubine, rewarding her “brother” with wealth. Abraham saved his own skin at the expense of his wife. Abraham pulls the same trick with their next host, the king Abemelek of Gerar. God spoke to the king and told him to return Sarah to her husband, and until he did so no woman of Abemelek’s court would conceive. Despite Abraham being responsible for the lies, only Sarah is blamed for the misfortune of all these women: “For the Lord had closed fast all the wombs of the house… because of Sarah, Abraham’s wife.” Abraham threw Sarah under the chariot.

Rahab featured in James Tissot's The Harlot of Jericho and the Two Spies, Wikimedia Commons

Rahab featured in James Tissot's The Harlot of Jericho and the Two Spies, Wikimedia Commons

Women featured in the Hebrew Bible seem to have power and autonomy, although they were socially unequal. Rahab, for example, was a prostitute who sheltered Hebrew spies during the invasion of Canaan. Deborah, is the only female judge in a male-dominated culture, and Esther, the influential Persian Queen saves the Jewish people by foiling a plot to murder them by the evil minister, Haman.

Some women are derided in the Old Testament. Jezebel persecuted the prophets and clung to idolatrous religion and thus earned such a reputation for wickedness that even today her name is used to describe a deceitful woman. Her story shows that she had her own beliefs and had some agency to act upon them.

Jezebel wasn’t the only woman with agency in Hebrew stories. The Queen of Sheba, for instance, was described extensively in the Abrahamic faiths, although some consider her to be a mythological character. She was a wise and respected queen from Arabia who found clever ways to protect and mother her people, including marrying an enemy to save her people from war, only to kill him on their wedding night. The Jewish King Solomon then heard of her power, but he really desired her spectacular throne and demanded she submit to him. After an exchange, she eventually came with an entourage, only to find that Solomon had stolen her throne and was sitting on it. In some versions of the story, she accepted defeat and submitted to him to save her people. Humbling herself before a powerful male king, she crossed a glass floor to approach him and, thinking it was water, lifted her skirts to reveal her hairy legs. Modern female scholars across Abrahamic faiths read her story differently. She was a wise queen who put her people before her pride and accepted humiliation to avoid war.

Some women are derided in the Old Testament. Jezebel persecuted the prophets and clung to idolatrous religion and thus earned such a reputation for wickedness that even today her name is used to describe a deceitful woman. Her story shows that she had her own beliefs and had some agency to act upon them.

Jezebel wasn’t the only woman with agency in Hebrew stories. The Queen of Sheba, for instance, was described extensively in the Abrahamic faiths, although some consider her to be a mythological character. She was a wise and respected queen from Arabia who found clever ways to protect and mother her people, including marrying an enemy to save her people from war, only to kill him on their wedding night. The Jewish King Solomon then heard of her power, but he really desired her spectacular throne and demanded she submit to him. After an exchange, she eventually came with an entourage, only to find that Solomon had stolen her throne and was sitting on it. In some versions of the story, she accepted defeat and submitted to him to save her people. Humbling herself before a powerful male king, she crossed a glass floor to approach him and, thinking it was water, lifted her skirts to reveal her hairy legs. Modern female scholars across Abrahamic faiths read her story differently. She was a wise queen who put her people before her pride and accepted humiliation to avoid war.

Virgin Mary, Public Domain

Virgin Mary, Public Domain

Jesus

These stories were well known when Jesus Christ, a Jew born under Roman rule, preached the story of a loving God who absolved sin and offered forgiveness. Women, including his mother, Mary, became immediate followers. His teaching was recorded in the four gospels and other books in the New Testament in which women were frequently portrayed either so pure as to be unattainable, or whores.

Mary, or the Virgin Mary, is central to the story of Christianity and fits into the unattainable category. In the New Testament, God sends an angel to Mary to tell her that she will bear the son of God, Jesus. Mary's epic and pregnant journey to Bethlehem has been told and reenacted in churches around the world for millennia. But Mary's virginity, central to the story, has no basis in history. Mary would have been very young at the age she was betrothed to Joseph, perhaps 12. A year after their betrothal, she would have been sent to live with Joseph and his family. Had she become pregnant out of wedlock at that time, she would have been terrified, as the consequences were severe, including the possibility of being sold into slavery or stoned to death. Yet the New Testament tells us that Joseph was visited by an angel and told to marry her anyway. Some tried to slander Mary’s story by claiming she was raped by a Roman soldier and even provided a name of one, but this story was likely concocted to discredit Jesus.

In the Greek and Roman traditions, virgin births were common. Dionysos was the son of a virgin. Jason was the son of the virgin, Persephone. Plato’s mother, Perictione, was a virgin. Attis, a Phrygo-Roman god, was born to the virgin Nana, on December 2. Even Emperor Augustus, traced his lineage back to Romulus and Remus, who were born by a god to a virgin priestess.

These stories were well known when Jesus Christ, a Jew born under Roman rule, preached the story of a loving God who absolved sin and offered forgiveness. Women, including his mother, Mary, became immediate followers. His teaching was recorded in the four gospels and other books in the New Testament in which women were frequently portrayed either so pure as to be unattainable, or whores.

Mary, or the Virgin Mary, is central to the story of Christianity and fits into the unattainable category. In the New Testament, God sends an angel to Mary to tell her that she will bear the son of God, Jesus. Mary's epic and pregnant journey to Bethlehem has been told and reenacted in churches around the world for millennia. But Mary's virginity, central to the story, has no basis in history. Mary would have been very young at the age she was betrothed to Joseph, perhaps 12. A year after their betrothal, she would have been sent to live with Joseph and his family. Had she become pregnant out of wedlock at that time, she would have been terrified, as the consequences were severe, including the possibility of being sold into slavery or stoned to death. Yet the New Testament tells us that Joseph was visited by an angel and told to marry her anyway. Some tried to slander Mary’s story by claiming she was raped by a Roman soldier and even provided a name of one, but this story was likely concocted to discredit Jesus.

In the Greek and Roman traditions, virgin births were common. Dionysos was the son of a virgin. Jason was the son of the virgin, Persephone. Plato’s mother, Perictione, was a virgin. Attis, a Phrygo-Roman god, was born to the virgin Nana, on December 2. Even Emperor Augustus, traced his lineage back to Romulus and Remus, who were born by a god to a virgin priestess.

Mary Magdalene and Jesus, Public Domain

Mary Magdalene and Jesus, Public Domain

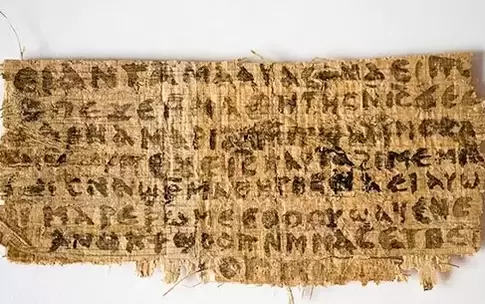

In 1896, a German scholar purchased fragments of what would later be determined to be Gnostic gospels. These 1st century Christian texts were not incorporated into the official Bible but are still used by scholars today. Combined, these fragments and complete works comprised over fifty different texts with different authors dated during and after the life of Jesus. They included gospels, poems, and myths, very different from those selected by the early Christian church to be in the Bible. One of these authors, uncopied for almost two millennia, was named after, and maybe authored by, a woman: Mary Magdalene.

The Gnostic gospels made Mary a complex and spiritual version of Mary, thereby making her controversial. The Gnostic gospels were condemned as heresy by the young Christian empire. What has been uncovered from the Gospel of Mary is still missing large portions as yet to be found and interpreted.

The account makes her central in the aftermath of Jesus’ passing. In Chapter 5, the grieving disciples turned to Mary to hear the words of Christ. She said, “What is hidden from you I will proclaim to you.”

In Chapter 9, Peter asks, “Did He really speak privately with a woman and not openly to us? Are we to turn about and all listen to her? Did He prefer her to us?” Mary weeps at his doubt, only to be defended by Levi, who says, “Peter you have always been hot tempered. Now I see you contending against the woman like the adversaries. But if the Savior made her worthy, who are you indeed to reject her? Surely the Savior knows her very well.”

These and other parts of the text suggest that Mary was closer to Jesus than the male disciples.

A translation by the historian Elaine Pagels reads, “the companion of the [Savior is] Mary Magdalene. [But Christ loved] her more than [all] the disciples, and used to kiss her [often] on her [mouth]. The rest of [the disciples were offended] . . . They said to him, ‘Why do you love her more than all of us?’ The Savior answered and said to them, ‘Why do I not love you as (I love) her?’”

Was the idea of a female partner to Jesus too much? Or was Mary’s gospel and those of her supporters repressed because of the jealousy of the other disciples? Did Jesus truly love her more?

Christian thinkers of the period created a landscape where obedience, self-abnegation, and perpetual remorse were the only acceptable attitudes for women. Why? This comes back to the function of women–to have children.

Early Christian leaders certainly held women in some contempt. Saint Paul, who spread the faith in the first century, wrote the most quoted line to silence and subordinate women in 1 Corinthians 14:34: “Women should keep silent in the churches, for they are not allowed to speak, but should be subordinate, as even the law says. But if they want to learn anything, they should ask their husbands at home. For it is improper for a woman to speak in the church.”

Paul was writing his letters to Christians in Rome and Corinth with advice on how to avoid being slaughtered by the pagan-Roman majority. Roman’s were very patriarchal compared to the early Christians. Pa was saying that women should keep quiet in church in order to help the Christian minority stay “under the radar,” and keep them safe.

For sure, this is difficult to interpret because he may even be quoting a Roman law. But regardless, the effect was that a lot of people interpreted it to mean that Paul wanted women to remain silent.

The Gnostic gospels made Mary a complex and spiritual version of Mary, thereby making her controversial. The Gnostic gospels were condemned as heresy by the young Christian empire. What has been uncovered from the Gospel of Mary is still missing large portions as yet to be found and interpreted.

The account makes her central in the aftermath of Jesus’ passing. In Chapter 5, the grieving disciples turned to Mary to hear the words of Christ. She said, “What is hidden from you I will proclaim to you.”

In Chapter 9, Peter asks, “Did He really speak privately with a woman and not openly to us? Are we to turn about and all listen to her? Did He prefer her to us?” Mary weeps at his doubt, only to be defended by Levi, who says, “Peter you have always been hot tempered. Now I see you contending against the woman like the adversaries. But if the Savior made her worthy, who are you indeed to reject her? Surely the Savior knows her very well.”

These and other parts of the text suggest that Mary was closer to Jesus than the male disciples.

A translation by the historian Elaine Pagels reads, “the companion of the [Savior is] Mary Magdalene. [But Christ loved] her more than [all] the disciples, and used to kiss her [often] on her [mouth]. The rest of [the disciples were offended] . . . They said to him, ‘Why do you love her more than all of us?’ The Savior answered and said to them, ‘Why do I not love you as (I love) her?’”

Was the idea of a female partner to Jesus too much? Or was Mary’s gospel and those of her supporters repressed because of the jealousy of the other disciples? Did Jesus truly love her more?

Christian thinkers of the period created a landscape where obedience, self-abnegation, and perpetual remorse were the only acceptable attitudes for women. Why? This comes back to the function of women–to have children.

Early Christian leaders certainly held women in some contempt. Saint Paul, who spread the faith in the first century, wrote the most quoted line to silence and subordinate women in 1 Corinthians 14:34: “Women should keep silent in the churches, for they are not allowed to speak, but should be subordinate, as even the law says. But if they want to learn anything, they should ask their husbands at home. For it is improper for a woman to speak in the church.”

Paul was writing his letters to Christians in Rome and Corinth with advice on how to avoid being slaughtered by the pagan-Roman majority. Roman’s were very patriarchal compared to the early Christians. Pa was saying that women should keep quiet in church in order to help the Christian minority stay “under the radar,” and keep them safe.

For sure, this is difficult to interpret because he may even be quoting a Roman law. But regardless, the effect was that a lot of people interpreted it to mean that Paul wanted women to remain silent.

Mary Magdalene proclaiming “The First Easter Homily" by Margaret Beaudette, Public Domain

Mary Magdalene proclaiming “The First Easter Homily" by Margaret Beaudette, Public Domain

Another prominent Christian thinker, Tertullian, said: “The sentence of God on this sex of yours lives on even in our times so it is necessary that the guilt should live on also. You are the one who opened the door to evil, you are the one who plucked the fruit of the forbidden tree, you are the one who deserted the divine law; you are the one who persuaded him whom the devil was not strong enough to attack. All too easily you destroyed the image of God, man. Because of your deception, that is, death, even the son of God had to die.”

Tertullian's philosophy and obsession with women’s subjugation became common by the Medieval era. Popular literature portrayed women as subversive and connected to the wild forces of nature. Men became suspicious of women’s sexuality and fought to suppress it. Once again, sex for women was supposed to be just about reproduction.

The myth of Adam and Eve as justification for female subordination led historian Rosalind Miles to assert that it was “the single most effective piece of enemy propaganda… Eve did not fall, she was pushed.” And certainly its repetition among early modern writers and the continued denial of women’s education supports this.

The two Marys with central roles in the New Testament were stripped of their substance and became known not for their spirituality and guidance of Jesus, but for their sexuality: Mary the impossibly virgin mother and Mary the whore. Were these stories repressed because they did not fit the church's vision of womanhood? This is a tricky question because that vision of women’s role in society was evolving in the early Christian period.

The fact that information was withheld or forcibly repressed reveals the greatest error in traditional history: we disproportionately attribute achievement to men because of a lack of sources about and by women. Women were generally not taught to read and write so they could not leave source documents. Women were confined to households so they did not contribute to public discourse. This suggests that it was impossible for women to create sources by women, not that women’s writings were repressed.

Tertullian's philosophy and obsession with women’s subjugation became common by the Medieval era. Popular literature portrayed women as subversive and connected to the wild forces of nature. Men became suspicious of women’s sexuality and fought to suppress it. Once again, sex for women was supposed to be just about reproduction.

The myth of Adam and Eve as justification for female subordination led historian Rosalind Miles to assert that it was “the single most effective piece of enemy propaganda… Eve did not fall, she was pushed.” And certainly its repetition among early modern writers and the continued denial of women’s education supports this.

The two Marys with central roles in the New Testament were stripped of their substance and became known not for their spirituality and guidance of Jesus, but for their sexuality: Mary the impossibly virgin mother and Mary the whore. Were these stories repressed because they did not fit the church's vision of womanhood? This is a tricky question because that vision of women’s role in society was evolving in the early Christian period.

The fact that information was withheld or forcibly repressed reveals the greatest error in traditional history: we disproportionately attribute achievement to men because of a lack of sources about and by women. Women were generally not taught to read and write so they could not leave source documents. Women were confined to households so they did not contribute to public discourse. This suggests that it was impossible for women to create sources by women, not that women’s writings were repressed.

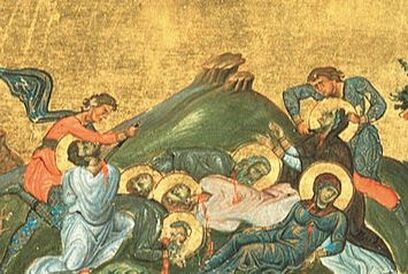

The martyrdom of Perpetua, Felicitas, Revocatus, Saturninus and Secundulus, from the Menologion of Basil II, 1000 CE, Wikimedia Commons

The martyrdom of Perpetua, Felicitas, Revocatus, Saturninus and Secundulus, from the Menologion of Basil II, 1000 CE, Wikimedia Commons

Spreading Christianity

Despite the attacks on women’s contributions to the faith, women were dedicated to spreading Christianity. Christian women were treated better than non-Christians.

Jesus died by crucifixion for the faith and thus early Christians, including women, willingly martyred themselves after his example. Two centuries after the death of Jesus, Perpetua was a 22- year old noblewoman and nursing mother. Her slave Felicity was pregnant when both were arrested for having converted to Christianity in Carthage in north Africa. In prison, she wrote an account that is generally recognized as historical, making it the earliest surviving text written by a Christian woman. Perpetua described the anxiety she felt being separated from her unweaned child, how her Pagan father begged her repeatedly to renounce her faith, and how she was eventually reunited with her child and was again able to breastfeed. She said, "Straightway I became well… suddenly the prison was made a palace for me." But her love for her child did not weaken her resolve. She, Felicity, and several male converts held to their faith and were sentenced to death by being attacked by wild animals, a common punishment in Ancient Rome. Felicity gave birth two days before the execution to a daughter adopted by other Christians, something she considered a miracle. She had been worried her pregnancy would prevent her from joining her friends in martyrdom since Roman law forbade the execution of a pregnant woman. Even in the arena, however, the women were separated from the men so that a female beast, “an enraged heifer”, could kill the women.

Despite the attacks on women’s contributions to the faith, women were dedicated to spreading Christianity. Christian women were treated better than non-Christians.

Jesus died by crucifixion for the faith and thus early Christians, including women, willingly martyred themselves after his example. Two centuries after the death of Jesus, Perpetua was a 22- year old noblewoman and nursing mother. Her slave Felicity was pregnant when both were arrested for having converted to Christianity in Carthage in north Africa. In prison, she wrote an account that is generally recognized as historical, making it the earliest surviving text written by a Christian woman. Perpetua described the anxiety she felt being separated from her unweaned child, how her Pagan father begged her repeatedly to renounce her faith, and how she was eventually reunited with her child and was again able to breastfeed. She said, "Straightway I became well… suddenly the prison was made a palace for me." But her love for her child did not weaken her resolve. She, Felicity, and several male converts held to their faith and were sentenced to death by being attacked by wild animals, a common punishment in Ancient Rome. Felicity gave birth two days before the execution to a daughter adopted by other Christians, something she considered a miracle. She had been worried her pregnancy would prevent her from joining her friends in martyrdom since Roman law forbade the execution of a pregnant woman. Even in the arena, however, the women were separated from the men so that a female beast, “an enraged heifer”, could kill the women.

Nuns, Public Domain

Nuns, Public Domain

Convents

Monasteries were common across Europe and as early as the 300s, and women performed similar duties to their male counterparts, although usually with male supervisors after the seventh century. Inside convents, women became scholars after vowing to be chaste, served the needy, and renounced their earthly possessions. By dedicating their lives to God, women were allowed a choice other than motherhood and domestic servitude. Nuns of the early convent period often lived longer than their married counterparts because childbirth was a leading cause of death for premodern women.

Convents did not upend patriarchy, but they provided refuge from it for centuries. But there was a limit to their academic and spiritual power. Nuns who forgot or defied the patriarchal power structure were punished, especially by the Reformation era in Europe. In the 1600s in England for example, one nun who tried to build a school to educate young girls was imprisoned in a windowless cell. Two other nuns began preaching in the streets. When asked who their husband was, the women replied, “They had no husband but Jesus Christ.” The mayor dubbed them whores and instructed the constable to whip them in the public square until blood ran down their backs.

Monasteries were common across Europe and as early as the 300s, and women performed similar duties to their male counterparts, although usually with male supervisors after the seventh century. Inside convents, women became scholars after vowing to be chaste, served the needy, and renounced their earthly possessions. By dedicating their lives to God, women were allowed a choice other than motherhood and domestic servitude. Nuns of the early convent period often lived longer than their married counterparts because childbirth was a leading cause of death for premodern women.

Convents did not upend patriarchy, but they provided refuge from it for centuries. But there was a limit to their academic and spiritual power. Nuns who forgot or defied the patriarchal power structure were punished, especially by the Reformation era in Europe. In the 1600s in England for example, one nun who tried to build a school to educate young girls was imprisoned in a windowless cell. Two other nuns began preaching in the streets. When asked who their husband was, the women replied, “They had no husband but Jesus Christ.” The mayor dubbed them whores and instructed the constable to whip them in the public square until blood ran down their backs.

Eastern and Western Empire, Wikimedia Commons

Eastern and Western Empire, Wikimedia Commons

Constantine and Hypatia

Eventually, the Roman empire split into the West and East. In Rome, Christianity gradually took root against a warring, bankrupt, and tumultuous political landscape. The Eastern emperor Constantine the first, or the Great, demanded religious toleration for all faiths, and he returned the sacked Christian churches to the faithful.

Constantine became the first Roman emperor to accept Christianity, his mother Helena’s religion. Roman traditionalists were horrified at his conversion and growing tyrannical rule. He used terror to force conversions and secure his power, which briefly reunited the fracturing empire. Constantine convened the Council of Nicaea, which determined the fate of the Marys by sanctifying the canon of texts to be included in the Bible and destroying all others as heresy.

Pagan writings and beliefs ultimately met the same fate. A group called the “parabalani” operated throughout the empire as essentially Christian terrorists, persecuting non-believers. After a brief reprise following Constantine’s death, Theodisius I became emperor, declaring Christianity the state religion and empowering the parabalani and bishops to destroy Jewish and pagan temples and idols.

Ancient Egypt had a long tradition of polytheism and a caste of female-priestesses under the goddess of the alphabet and library. Egyptians in the early centuries saw notable women scholars emerge such as Hypatia and Maria of Alexandria.

Maria, for example, founded theoretical and experimental alchemy and invented tools used by modern chemists. Little is known about her because none of her original philosophical writings exist. Some scholars believe she may be more than one woman. It is possible there were multiple Marias or that women assumed her name for her notability.

Eventually, the Roman empire split into the West and East. In Rome, Christianity gradually took root against a warring, bankrupt, and tumultuous political landscape. The Eastern emperor Constantine the first, or the Great, demanded religious toleration for all faiths, and he returned the sacked Christian churches to the faithful.

Constantine became the first Roman emperor to accept Christianity, his mother Helena’s religion. Roman traditionalists were horrified at his conversion and growing tyrannical rule. He used terror to force conversions and secure his power, which briefly reunited the fracturing empire. Constantine convened the Council of Nicaea, which determined the fate of the Marys by sanctifying the canon of texts to be included in the Bible and destroying all others as heresy.

Pagan writings and beliefs ultimately met the same fate. A group called the “parabalani” operated throughout the empire as essentially Christian terrorists, persecuting non-believers. After a brief reprise following Constantine’s death, Theodisius I became emperor, declaring Christianity the state religion and empowering the parabalani and bishops to destroy Jewish and pagan temples and idols.

Ancient Egypt had a long tradition of polytheism and a caste of female-priestesses under the goddess of the alphabet and library. Egyptians in the early centuries saw notable women scholars emerge such as Hypatia and Maria of Alexandria.

Maria, for example, founded theoretical and experimental alchemy and invented tools used by modern chemists. Little is known about her because none of her original philosophical writings exist. Some scholars believe she may be more than one woman. It is possible there were multiple Marias or that women assumed her name for her notability.

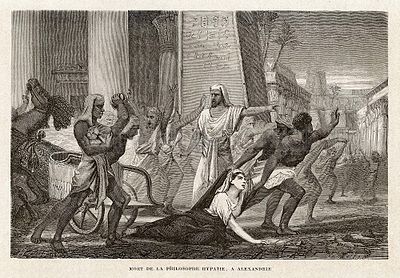

Death of Hypatia, Wikimedia Commons

Death of Hypatia, Wikimedia Commons

In Hypatia’s case, her accomplishments are well documented by primary sources. Her resistance to the dominant culture and her defiance of Christianity led to her demise. She was brilliant and noted by her contemporaries for her intellectualism. She was the only woman to hold a position as an academic at Alexandria’s University and did so wearing the same robes

as the male scholars. One primary account described her, saying: “On account of her self-possession and ease of manner, which she had acquired in consequence of the cultivation of her mind, she not infrequently appeared in public in the presence of the magistrates. Neither did she feel abashed in coming to an assembly of men. For all men on account of her extraordinary dignity and virtue admired her the more.”

Hypatia’s high profile proved to be problematic. She stood between reason and the newly-formed Christian church. Historian Joshua Mark explained that her “charisma, charm, and excellence in making difficult mathematical and philosophical concepts understandable to her students… contradicted the teachings of the relatively new church.” Hypatia’s world became the center of a religious conflict that disrupted the religious syncretism of the Roman Empire and ultimately cost her life.

Alexandria became a hotbed for the conflict when Cyril became the Christian bishop and a more moderate Christian, Orestes, was appointed the lesser title of Prefect. Cyril expelled the Jewish population and destroyed pagan temples, images of their gods and goddesses, and documents, an act that infuriated Orestes. He wrote to the bishop in opposition, which resulted in a multi-year political confrontation. Over time, Cyril fueled Christians’ fear by turning on Hypatia, one of Orestes greatest supporters, using her pagan beliefs and unnatural position as a famous woman scholar to condemn her. A sympathetic Socrates Scholasticus wrote: “Yet even she fell a victim to the political jealousy which at that time prevailed. For as she had frequent interviews with Orestes, it was calumniously reported among the Christian populace, that it was she who prevented Orestes from being reconciled to the bishop. Some of them therefore, hurried away by a fierce and bigoted zeal… and dragging her from her carriage… stripped her, and then murdered her with tiles. After tearing her body in pieces, they took her mangled limbs… and there burnt them… surely nothing can be farther from the spirit of Christianity than the allowance of massacres, fights, and transactions of that sort.”

Other accounts say that the parabalani pulled her from her carriage and murdered her with oyster shells. The ancient historian, Damascus, told a much different version of the story. He said that the Christian bishop was so shocked when he arrived in Alexandria by the throngs of people coming to listen to a woman that he immediately began to plan her murder. He said, “This information gave his heart such a prick… So next time, when following her usual custom, she appeared on the street, a mob of brutal men at once rushed at her—truly wicked men ‘fearing neither the revenge of the gods nor the judgment of men’ – and killed the philosopher… while she was still feebly twitching, they beat her eyes out… and as a result they laid upon the city the heaviest blood-guilt.”

Much later the story was dramatized by John of Naikiu to emphasize her wicked qualities: “She was devoted at all times to magic, astrolabes and instruments of music, and she beguiled many people through her satanic wiles. And the governor of the city [Orestes] honored her exceedingly for she had beguiled him through her magic.”

Whatever the detail of her horrible demise, Hypatia’s essential crime was being an educated woman allied with Orestes in opposition to the fanatic Christians in Alexandria.

None of the opponents who faced death for their pagan or Jewish beliefs died in such a way. Orestes himself, the person standing in Cyril’s path, disappeared. Had he been a woman, would he have met the same gruesome fate? Intellectual life in Alexandria ceased to exist following Hypatia’s murder.; The school closed, and Hypatia’s writings were destroyed as heresy. Cyril was elevated to sainthood and Hypatia was forgotten until the Renaissance re-interested Europe in the bygone knowledge.

Was it her womanhood or her pagan-ness that cost her life? Is it possible to separate the two?

as the male scholars. One primary account described her, saying: “On account of her self-possession and ease of manner, which she had acquired in consequence of the cultivation of her mind, she not infrequently appeared in public in the presence of the magistrates. Neither did she feel abashed in coming to an assembly of men. For all men on account of her extraordinary dignity and virtue admired her the more.”

Hypatia’s high profile proved to be problematic. She stood between reason and the newly-formed Christian church. Historian Joshua Mark explained that her “charisma, charm, and excellence in making difficult mathematical and philosophical concepts understandable to her students… contradicted the teachings of the relatively new church.” Hypatia’s world became the center of a religious conflict that disrupted the religious syncretism of the Roman Empire and ultimately cost her life.

Alexandria became a hotbed for the conflict when Cyril became the Christian bishop and a more moderate Christian, Orestes, was appointed the lesser title of Prefect. Cyril expelled the Jewish population and destroyed pagan temples, images of their gods and goddesses, and documents, an act that infuriated Orestes. He wrote to the bishop in opposition, which resulted in a multi-year political confrontation. Over time, Cyril fueled Christians’ fear by turning on Hypatia, one of Orestes greatest supporters, using her pagan beliefs and unnatural position as a famous woman scholar to condemn her. A sympathetic Socrates Scholasticus wrote: “Yet even she fell a victim to the political jealousy which at that time prevailed. For as she had frequent interviews with Orestes, it was calumniously reported among the Christian populace, that it was she who prevented Orestes from being reconciled to the bishop. Some of them therefore, hurried away by a fierce and bigoted zeal… and dragging her from her carriage… stripped her, and then murdered her with tiles. After tearing her body in pieces, they took her mangled limbs… and there burnt them… surely nothing can be farther from the spirit of Christianity than the allowance of massacres, fights, and transactions of that sort.”

Other accounts say that the parabalani pulled her from her carriage and murdered her with oyster shells. The ancient historian, Damascus, told a much different version of the story. He said that the Christian bishop was so shocked when he arrived in Alexandria by the throngs of people coming to listen to a woman that he immediately began to plan her murder. He said, “This information gave his heart such a prick… So next time, when following her usual custom, she appeared on the street, a mob of brutal men at once rushed at her—truly wicked men ‘fearing neither the revenge of the gods nor the judgment of men’ – and killed the philosopher… while she was still feebly twitching, they beat her eyes out… and as a result they laid upon the city the heaviest blood-guilt.”

Much later the story was dramatized by John of Naikiu to emphasize her wicked qualities: “She was devoted at all times to magic, astrolabes and instruments of music, and she beguiled many people through her satanic wiles. And the governor of the city [Orestes] honored her exceedingly for she had beguiled him through her magic.”

Whatever the detail of her horrible demise, Hypatia’s essential crime was being an educated woman allied with Orestes in opposition to the fanatic Christians in Alexandria.

None of the opponents who faced death for their pagan or Jewish beliefs died in such a way. Orestes himself, the person standing in Cyril’s path, disappeared. Had he been a woman, would he have met the same gruesome fate? Intellectual life in Alexandria ceased to exist following Hypatia’s murder.; The school closed, and Hypatia’s writings were destroyed as heresy. Cyril was elevated to sainthood and Hypatia was forgotten until the Renaissance re-interested Europe in the bygone knowledge.

Was it her womanhood or her pagan-ness that cost her life? Is it possible to separate the two?

Islam

Judaism and Christianity continued to spread, change,, and adapt throughout the world. In the 7th century, the battle for monotheism spread to the Arabian peninsula. This religion, whose tenets were revealed through the Prophet Muhammad, came to be known as Islam. It began as a monotheistic tradition intended to replace Paganism and perfect belief in the One True God as a culmination of the Jewish and Christian traditions. Like Christianity before it, Islam adopted all of the male prophets and stories of the Old and New Testaments. It also followed the Jewish tradition of referring to God, or Allah, a being beyond human categorizations such as gender, with masculine pronouns leading many to imagine God as male. Learn more about women in Islam here.

Conclusion

All around the world, religions played a critical role in creating the cultural and belief structures that defined women’s lives. Some feminists go so far as to suggest, “Religions are one of the oldest and the most persistent obstacles on the way of women’s equality and freedom. Indeed, religion is women’s enemy and it is the nature of all religions… to look backwards to past ancient times and antiquated values.”

Even in the Americas, where societies were developing without the benefits of Afro-Eurasian cultural diffusion, many of the Mesoamerican gods that had been gender-less or dual gender were superseded by an all powerful male, sun god, reflecting the military society they lived in.

To this day, the role of women in the monotheistic traditions is a hotly contested topic. We encourage you to revisit these faiths and find the women whose stories have been downplayed or even erased for centuries.

What role did women play in the early days of these traditions, and how have they shaped them in the centuries since? How did women find agency despite official doctrine? How did these faiths affect the day to day realities of female followers of the faiths? And if we look at the evidence, is the monotheistic God really as masculine as patriarchal tradition would have us believe? And those nunneries– what role would they play in pushing back against the male leadership?

Judaism and Christianity continued to spread, change,, and adapt throughout the world. In the 7th century, the battle for monotheism spread to the Arabian peninsula. This religion, whose tenets were revealed through the Prophet Muhammad, came to be known as Islam. It began as a monotheistic tradition intended to replace Paganism and perfect belief in the One True God as a culmination of the Jewish and Christian traditions. Like Christianity before it, Islam adopted all of the male prophets and stories of the Old and New Testaments. It also followed the Jewish tradition of referring to God, or Allah, a being beyond human categorizations such as gender, with masculine pronouns leading many to imagine God as male. Learn more about women in Islam here.

Conclusion

All around the world, religions played a critical role in creating the cultural and belief structures that defined women’s lives. Some feminists go so far as to suggest, “Religions are one of the oldest and the most persistent obstacles on the way of women’s equality and freedom. Indeed, religion is women’s enemy and it is the nature of all religions… to look backwards to past ancient times and antiquated values.”

Even in the Americas, where societies were developing without the benefits of Afro-Eurasian cultural diffusion, many of the Mesoamerican gods that had been gender-less or dual gender were superseded by an all powerful male, sun god, reflecting the military society they lived in.

To this day, the role of women in the monotheistic traditions is a hotly contested topic. We encourage you to revisit these faiths and find the women whose stories have been downplayed or even erased for centuries.

What role did women play in the early days of these traditions, and how have they shaped them in the centuries since? How did women find agency despite official doctrine? How did these faiths affect the day to day realities of female followers of the faiths? And if we look at the evidence, is the monotheistic God really as masculine as patriarchal tradition would have us believe? And those nunneries– what role would they play in pushing back against the male leadership?

Draw your own conclusions

|

Learn how to teach with inquiry.

Many of these lesson plans were sponsored in part by the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources Eastern Region Program, coordinated by Waynesburg University, the History and Social Studies Education Faculty at Plymouth State University, and the Patrons of the Remedial Herstory Project. |

Lesson Plans from Other Organizations

- This website, Women in World History has primary source based lesson plans on women's history in a whole range of topics. Some are free while others have a cost.

- The Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media has produced recommendations for teaching women's history with primary sources and provided a collection of sources for world history. Check them out!

- The Stanford History Education Group has a number of lesson plans about women in World History.

The Passion of Saints: Perpetua & Felicity Part I Part II

The Passion of Saints Perpetua and Felicity is the text through which these two martyrs became remembered. The text is largely autobiographical from the perspective of Perpetua with a preface and conclusion by another author. Therefore, the text is a rare example of a first-person historical narrative written by a woman. The source details the imprisonment of Perpetua and her fellow martyrs until their death. Below is part I-II of the Passion of Saints, introducing Perpetua and her fellow martyrs.

If the old examples of the faith, which testify to the grace of God and lead to the edification of men, were written down so that by reading them God should be honored and man comforted—as if through a reexamination of those deeds—should we not set down new acts that serve each purpose equally? For these too will some day also be venerable and compelling for future generations, even if at the present time they are judged to be of lesser importance, due to the respect naturally afforded the past. But let those who would restrict the singular power of the one spirit to certain times understand this: that newer events are necessarily greater because they are more recent, because of the overflow of grace promised for the end of time.

In the last days, says the Lord, “I will pour out my Spirit on all flesh; and their sons and daughters shall prophesy; and I will pour out my Spirit on my servants and handmaidens; and your young men shall see visions and your old men shall dream dreams.”

And we, who also acknowledge and honor the new prophecies and new visions as well, according to the promise, and regard the other virtues of the Holy Spirit as intended for the instruction of the church (to which church the same spirit was sent distributing all gift s to all, just as the Lord grants to each one); therefore, out of necessity we both proclaim and celebrate them in reading for the glory of God, lest any person who is weak or despairing in their faith should think that only the ancients received divine grace (either in the favor of martyrdom or of revelations), since God always grants what he has promised, as a proof to the unbelievers and as a kindness to believers. And so we also announce to you, our brothers and little sons, that which we have heard and touched, so that you who were present may be reminded of the glory of the Lord, and that you who know it now through hearing may have a sharing with the holy martyrs, and through them with our Lord Jesus Christ, to whom be glory and honor for ever and ever. Amen.

Some young catechumens were arrested: Revocatus and Felicity, his fellow slave; Saturninus; and Secundulus. And among these was also Vibia Perpetua—a woman well born, liberally educated, and honorably married, who had a father, mother, and two brothers, one of whom was also a catechumen. She had an infant son still at the breast and was about twenty-two years of age. From this point there follows a complete account of her martyrdom, as she left it, written in her own hand and in accordance with her own understanding.

Heffernan. T (2012) The Passion of Perpetua and Felicity. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Questions:

If the old examples of the faith, which testify to the grace of God and lead to the edification of men, were written down so that by reading them God should be honored and man comforted—as if through a reexamination of those deeds—should we not set down new acts that serve each purpose equally? For these too will some day also be venerable and compelling for future generations, even if at the present time they are judged to be of lesser importance, due to the respect naturally afforded the past. But let those who would restrict the singular power of the one spirit to certain times understand this: that newer events are necessarily greater because they are more recent, because of the overflow of grace promised for the end of time.

In the last days, says the Lord, “I will pour out my Spirit on all flesh; and their sons and daughters shall prophesy; and I will pour out my Spirit on my servants and handmaidens; and your young men shall see visions and your old men shall dream dreams.”

And we, who also acknowledge and honor the new prophecies and new visions as well, according to the promise, and regard the other virtues of the Holy Spirit as intended for the instruction of the church (to which church the same spirit was sent distributing all gift s to all, just as the Lord grants to each one); therefore, out of necessity we both proclaim and celebrate them in reading for the glory of God, lest any person who is weak or despairing in their faith should think that only the ancients received divine grace (either in the favor of martyrdom or of revelations), since God always grants what he has promised, as a proof to the unbelievers and as a kindness to believers. And so we also announce to you, our brothers and little sons, that which we have heard and touched, so that you who were present may be reminded of the glory of the Lord, and that you who know it now through hearing may have a sharing with the holy martyrs, and through them with our Lord Jesus Christ, to whom be glory and honor for ever and ever. Amen.

Some young catechumens were arrested: Revocatus and Felicity, his fellow slave; Saturninus; and Secundulus. And among these was also Vibia Perpetua—a woman well born, liberally educated, and honorably married, who had a father, mother, and two brothers, one of whom was also a catechumen. She had an infant son still at the breast and was about twenty-two years of age. From this point there follows a complete account of her martyrdom, as she left it, written in her own hand and in accordance with her own understanding.

Heffernan. T (2012) The Passion of Perpetua and Felicity. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Questions:

- What are Perpetua and Felicity's beliefs?

The Passion Of Saints: Perpetua & Felicity Part III

In this extract from the Passion of Saints, Perpetua explains her faith as her father begs her to denounce it.

“While,” she said, “we were still with the prosecutors, my father, because of his love for me, wanted to change my mind and shake my resolve. ‘Father,’ I said, ‘do you see this vase lying here, for example, this small water pitcher or whatever?’ ‘I see it,’ he said. And I said to him: ‘Can it be called by another name other than what it is?’ And he said: ‘No.’ ‘In the same way, I am unable to call myself other than what I am, a Christian.’ Then my father, angered by this name, threw himself at me, in order to gouge out my eyes. But he only alarmed me and he left defeated, along with the arguments of the devil. Then for a few days, freed from my father, I gave thanks to the Lord and was refreshed by my father’s absence. In the space of a few days we were baptized.

Heffernan. T (2012) The Passion of Perpetua and Felicity. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Questions:

“While,” she said, “we were still with the prosecutors, my father, because of his love for me, wanted to change my mind and shake my resolve. ‘Father,’ I said, ‘do you see this vase lying here, for example, this small water pitcher or whatever?’ ‘I see it,’ he said. And I said to him: ‘Can it be called by another name other than what it is?’ And he said: ‘No.’ ‘In the same way, I am unable to call myself other than what I am, a Christian.’ Then my father, angered by this name, threw himself at me, in order to gouge out my eyes. But he only alarmed me and he left defeated, along with the arguments of the devil. Then for a few days, freed from my father, I gave thanks to the Lord and was refreshed by my father’s absence. In the space of a few days we were baptized.

Heffernan. T (2012) The Passion of Perpetua and Felicity. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Questions:

- What are Perpetua and Felicity's beliefs?

The Passion Of Saints: Perpetua & Felicity Part XX

This final extract from the Passion of Saints describes the death of Perpetua and Felicity in the arena.

For the young women, however, the devil prepared a wild cow—not a traditional practice—matching their sex with that of the beast. And so stripped naked and covered only with nets, they were brought out again. The crowd shuddered, seeing that one was a delicate young girl and that the other had recently given birth, as her breasts were still dripping with milk. So they were called back and dressed in unbelted robes. Perpetua was thrown down first and fell on her loins. Then sitting up, she noticed that her tunic was ripped on the side, and so she drew it up to cover her thigh, more mindful of her modesty than her suffering. Then she requested a pin and she tied up her tousled hair; for it was not right for a martyr to suffer with disheveled hair, since it might appear that she was grieving in her moment of glory.

Then she got up; and when she saw Felicity crushed to the ground, she went over to her, gave her her hand and helped her up. And the two stood side by side. The cruelty of the crowd now being sated, they were called back to the Gate of Life. There Perpetua was received by a certain Rusticus, also a catechumen, who clung to her side. She awakened, as if from a sleep—she was so deep in the spirit and in ecstasy—and looked about her, and said, to the amazement of all: “When are we to be thrown to the mad cow, or whatever it is?” And when she heard that it had already happened, she refused at first to believe it until she noticed certain marks of physical violence on her body and her clothing.

Then after calling her brother and the catechumen, she spoke to them, saying: “Stand fast in faith and love one another, and do not lose heart because of our sufferings.”

Heffernan. T (2012) The Passion of Perpetua and Felicity. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Questions:

For the young women, however, the devil prepared a wild cow—not a traditional practice—matching their sex with that of the beast. And so stripped naked and covered only with nets, they were brought out again. The crowd shuddered, seeing that one was a delicate young girl and that the other had recently given birth, as her breasts were still dripping with milk. So they were called back and dressed in unbelted robes. Perpetua was thrown down first and fell on her loins. Then sitting up, she noticed that her tunic was ripped on the side, and so she drew it up to cover her thigh, more mindful of her modesty than her suffering. Then she requested a pin and she tied up her tousled hair; for it was not right for a martyr to suffer with disheveled hair, since it might appear that she was grieving in her moment of glory.

Then she got up; and when she saw Felicity crushed to the ground, she went over to her, gave her her hand and helped her up. And the two stood side by side. The cruelty of the crowd now being sated, they were called back to the Gate of Life. There Perpetua was received by a certain Rusticus, also a catechumen, who clung to her side. She awakened, as if from a sleep—she was so deep in the spirit and in ecstasy—and looked about her, and said, to the amazement of all: “When are we to be thrown to the mad cow, or whatever it is?” And when she heard that it had already happened, she refused at first to believe it until she noticed certain marks of physical violence on her body and her clothing.

Then after calling her brother and the catechumen, she spoke to them, saying: “Stand fast in faith and love one another, and do not lose heart because of our sufferings.”

Heffernan. T (2012) The Passion of Perpetua and Felicity. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Questions:

- Why did they give their life for their beliefs?

The New Testament: John 8:1-11

The following is an encounter reported by the Bible in which religious leaders demand a woman caught committing adultery should be stoned to death. Jesus challenges the hypocrisy of the demands and simply urges the woman to change. One thing important to note in this passage is the absence of the man also involved in the adultery.

Jesus returned to the Mount of Olives, but early the next morning he was back again at the Temple. A crowd soon gathered, and he sat down and taught them. As he was speaking, the teachers of religious law and the Pharisees brought a woman who had been caught in the act of adultery. They put her in front of the crowd.

“Teacher,” they said to Jesus, “this woman was caught in the act of adultery. The law of Moses says to stone her. What do you say?”

They were trying to trap him into saying something they could use against him, but Jesus stooped down and wrote in the dust with his finger. They kept demanding an answer, so he stood up again and said, “All right, but let the one who has never sinned throw the first stone!” Then he stooped down again and wrote in the dust.

When the accusers heard this, they slipped away one by one, beginning with the oldest, until only Jesus was left in the middle of the crowd with the woman. Then Jesus stood up again and said to the woman, “Where are your accusers? Didn’t even one of them condemn you?”

“No, Lord,” she said.

And Jesus said, “Neither do I. Go and sin no more.”

John 8-21 - New Living Translation. Bible Gateway. https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=John+8-21&version=NLT.

Questions:

Jesus returned to the Mount of Olives, but early the next morning he was back again at the Temple. A crowd soon gathered, and he sat down and taught them. As he was speaking, the teachers of religious law and the Pharisees brought a woman who had been caught in the act of adultery. They put her in front of the crowd.

“Teacher,” they said to Jesus, “this woman was caught in the act of adultery. The law of Moses says to stone her. What do you say?”

They were trying to trap him into saying something they could use against him, but Jesus stooped down and wrote in the dust with his finger. They kept demanding an answer, so he stood up again and said, “All right, but let the one who has never sinned throw the first stone!” Then he stooped down again and wrote in the dust.

When the accusers heard this, they slipped away one by one, beginning with the oldest, until only Jesus was left in the middle of the crowd with the woman. Then Jesus stood up again and said to the woman, “Where are your accusers? Didn’t even one of them condemn you?”

“No, Lord,” she said.

And Jesus said, “Neither do I. Go and sin no more.”

John 8-21 - New Living Translation. Bible Gateway. https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=John+8-21&version=NLT.

Questions:

- What does this text say about how Jesus was described to perceive women? What about the male adulterer?

The New Testament: Galatians 3:26-29

The Epistle to the Galatians is a book by Paul the Apostle. In Chapter three, Paul teaches readers that believers are justified by their faith in Jesus alone.

Now before faith came, we were held captive under the law, imprisoned until the coming faith would be revealed. So then, the law was our guardian until Christ came, in order that we might be justified by faith. But now that faith has come, we are no longer under a guardian, for in Christ Jesus you are all sons of God, through faith. For as many of you as were baptized into Christ have put on Christ. There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is no male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus. And if you are Christ's, then you are Abraham's offspring, heirs according to promise

Galatians 3:26-29. English Standard Version. Bible Gateway. https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Galatians+3%3A26-29&version=ESV.

Questions:

Now before faith came, we were held captive under the law, imprisoned until the coming faith would be revealed. So then, the law was our guardian until Christ came, in order that we might be justified by faith. But now that faith has come, we are no longer under a guardian, for in Christ Jesus you are all sons of God, through faith. For as many of you as were baptized into Christ have put on Christ. There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is no male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus. And if you are Christ's, then you are Abraham's offspring, heirs according to promise

Galatians 3:26-29. English Standard Version. Bible Gateway. https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Galatians+3%3A26-29&version=ESV.

Questions:

- Why doesn’t this excerpt mention women directly?

- What can this text tell us about women's role in the church?

The New Testament: Timothy I 2:8-15

In the following extract, Paul is explaining to Timothy how to lead his church. In the passage, he focuses on the expectations of women in worship.

I want the men everywhere to pray, lifting up holy hands without anger or disputing. I also want the women to dress modestly, with decency and propriety, adorning themselves, not with elaborate hairstyles or gold or pearls or expensive clothes, but with good deeds, appropriate for women who profess to worship God.

A woman should learn in quietness and full submission. I do not permit a woman to teach or to assume authority over a man; she must be quiet. For Adam was formed first, then Eve. And Adam was not the one deceived; it was the woman who was deceived and became a sinner. But women will be saved through childbearing—if they continue in faith, love and holiness with propriety.

1 Timothy 2. New International Version. Bible Gateway. https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=1+Timothy+2&version=NIV.

I want the men everywhere to pray, lifting up holy hands without anger or disputing. I also want the women to dress modestly, with decency and propriety, adorning themselves, not with elaborate hairstyles or gold or pearls or expensive clothes, but with good deeds, appropriate for women who profess to worship God.

A woman should learn in quietness and full submission. I do not permit a woman to teach or to assume authority over a man; she must be quiet. For Adam was formed first, then Eve. And Adam was not the one deceived; it was the woman who was deceived and became a sinner. But women will be saved through childbearing—if they continue in faith, love and holiness with propriety.

1 Timothy 2. New International Version. Bible Gateway. https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=1+Timothy+2&version=NIV.

The New Testament: I Corinthians 14:34-35

The First Epistle to the Corinthians is one of Paul’s epistles in the New Testament of the Christian Bible. In section 14, Paul discusses Christian worship practices. The extract below concerns women in the church. There's debate over the meaning of this passage. Apparently the language is very similar to texts from pagan culture prohibiting women from speaking in civic assemblies in the Roman Empire. Some scholars argue that Paul is quoting someone else here in order to reject it, but the ancient Greeks didn't use quotation marks, so it’s difficult to know if these are his ideas, or if he is quoting others. Still, through most of historical Christian tradition, the verse was interpreted to mean women should not speak in church.

Women should remain silent in the churches. They are not allowed to speak, but must be in submission, as the law says. If they want to inquire about something, they should ask their own husbands at home; for it is disgraceful for a woman to speak in the church.

1 Corinthians 14.34-35. New International Version. Bible Gateway. https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=I%2BCor%2B14.34-35&version=NIV.

Questions:

Women should remain silent in the churches. They are not allowed to speak, but must be in submission, as the law says. If they want to inquire about something, they should ask their own husbands at home; for it is disgraceful for a woman to speak in the church.

1 Corinthians 14.34-35. New International Version. Bible Gateway. https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=I%2BCor%2B14.34-35&version=NIV.

Questions:

- Some scholars argue that Paul was trying to adhere to the harsh Roman laws and was telling women to adhere to them to avoid drawing attention to the church. If that were the case, how would that change your view of women’s status in the church?

The Old Testament: Deuteronomy 22:20-24

Trigger Warning: this extract will discuss rape. Please keep this in mind before reading this source and feel free to omit this document from your final conclusion. The extract from Deuteronomy, the fifth book of the Old Testament. The extract discusses archaic virginity tests, punishments for ‘promiscuity’ and rape.

If a man takes a wife and, after sleeping with her, dislikes her and slanders her and gives her a bad name, saying, “I married this woman, but when I approached her, I did not find proof of her virginity,” then the young woman’s father and mother shall bring to the town elders at the gate proof that she was a virgin. Her father will say to the elders, “I gave my daughter in marriage to this man, but he dislikes her. Now he has slandered her and said, ‘I did not find your daughter to be a virgin.’ But here is the proof of my daughter’s virginity.” Then her parents shall display the cloth before the elders of the town, and the elders shall take the man and punish him. They shall fine him a hundred shekels of silver and give them to the young woman’s father, because this man has given an Israelite virgin a bad name. She shall continue to be his wife; he must not divorce her as long as he lives.

If, however, the charge is true and no proof of the young woman’s virginity can be found, she shall be brought to the door of her father’s house and there the men of her town shall stone her to death. She has done an outrageous thing in Israel by being promiscuous while still in her father’s house. You must purge the evil from among you.

If a man is found sleeping with another man’s wife, both the man who slept with her and the woman must die. You must purge the evil from Israel. If a man happens to meet in a town a virgin pledged to be married and he sleeps with her, you shall take both of them to the gate of that town and stone them to death—the young woman because she was in a town and did not scream for help, and the man because he violated another man’s wife. You must purge the evil from among you.

Deuteronomy 22:20-24 - New International Version. Bible Gateway. https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Deuteronomy+22%3A20-21&version=NIV.

Questions:

- What are the different punishments for man and women in this text?

- Is virginity idolized in the text?

- Are female rape victims blamed in any way by the text?

The New Testament: Matthew 1:1-24

Scholars hypothesize the Gospel of Matthew was written about 15 years after the Gospel of Mark in 85CE. The first 17 lines of the first chapter refer to and attempt to establish Jesus’ parentage and direct connection to King David, a descendant from Abraham. The English translation uses the term “begat” which means fathered or brought into existence, usually through the male line.

1 The book of the generation of Jesus Christ, the son of David, the son of Abraham.

2 Abraham begat Isaac; and Isaac begat Jacob; and Jacob begat Judas and his brethren;

3 And Judas begat Phares and Zara of Thamar; and Phares begat Esrom; and Esrom begat Aram;

4 And Aram begat Aminadab; and Aminadab begat Naasson; and Naasson begat Salmon;

5 And Salmon begat Booz of Rachab; and Booz begat Obed of Ruth; and Obed begat Jesse;

6 And Jesse begat David the king; and David the king begat Solomon of her that had been the wife of Urias;

7 And Solomon begat Roboam; and Roboam begat Abia; and Abia begat Asa;

8 And Asa begat Josaphat; and Josaphat begat Joram; and Joram begat Ozias;

9 And Ozias begat Joatham; and Joatham begat Achaz; and Achaz begat Ezekias;

10 And Ezekias begat Manasses; and Manasses begat Amon; and Amon begat Josias;

11 And Josias begat Jechonias and his brethren, about the time they were carried away to Babylon: