3. Women’s Colonial Life

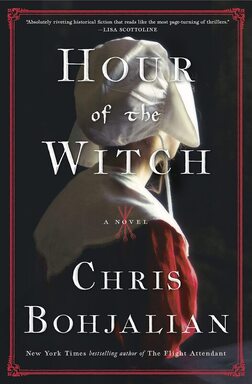

Life in Colonial America had many challenges. For women, the experience was both freeing in some respects–specifically from patriarchal controls–but also horrifying. This era would witness women who were able to acquire wealth through marriage and entrepreneurship, and women who would be burned at the stake for witchcraft. Undoubtedly, women’s experiences were incredibly diverse.

Witch Trials, Wikimedia Commons

Witch Trials, Wikimedia Commons

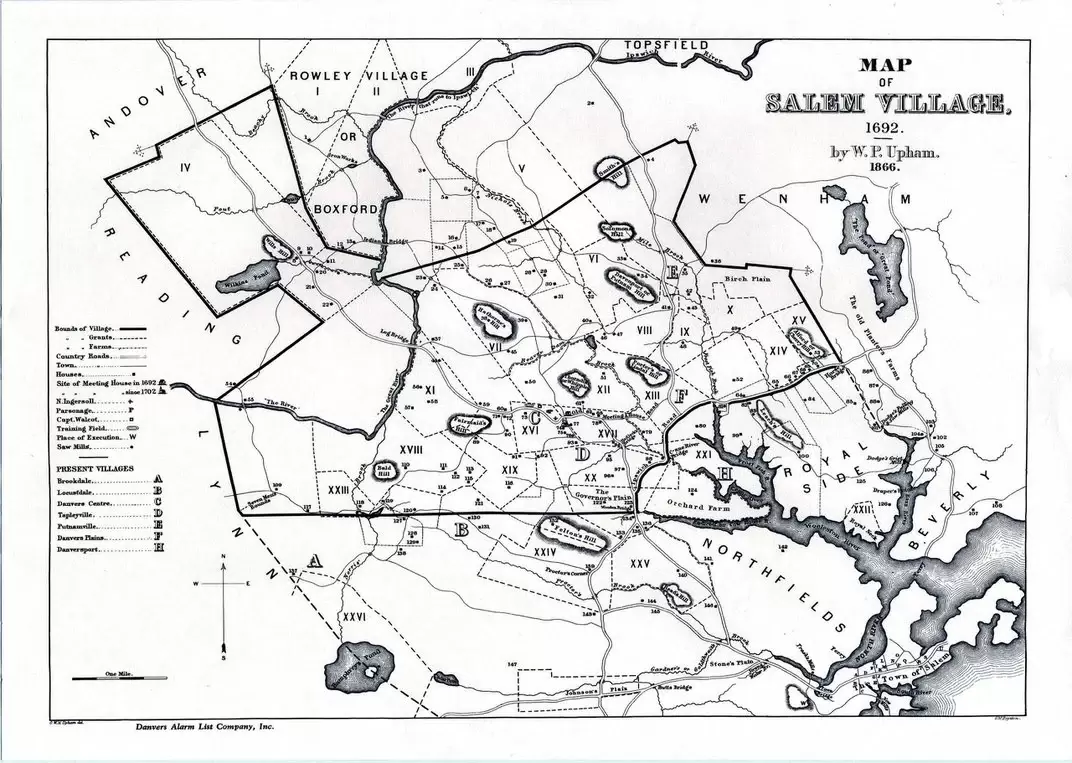

In the American colonies, women of the 1700s were greeted with horror after the overwhelmingly one-sided gendered massacre against women known as the Salem Witch Trials. Between 1692 and 1693 more than 200 people, mostly women, were accused of practicing witchcraft. 30 were found guilty, 19 were executed– 14 of those victims of superstition were women.

Worse, throughout the colonies, slavery was becoming synonymous with Blackness, and the conditions of servitude were becoming life sentences. Women in various states demonstrated their agency and lack of submission by leading slave rebellions.

Some women found opportunity in the religious movement of the period, known as the Great Awakening. For these women, this movement gave them more of a voice in churches and even resulted in some female preachers.

It was a time of tremendous change, solidifying footholds, colonial competition, and enduring restrictions on women’s rights and freedoms.

Worse, throughout the colonies, slavery was becoming synonymous with Blackness, and the conditions of servitude were becoming life sentences. Women in various states demonstrated their agency and lack of submission by leading slave rebellions.

Some women found opportunity in the religious movement of the period, known as the Great Awakening. For these women, this movement gave them more of a voice in churches and even resulted in some female preachers.

It was a time of tremendous change, solidifying footholds, colonial competition, and enduring restrictions on women’s rights and freedoms.

T.H. Matteson, Examination of a Witch, 1853, Wikimedia Commons

T.H. Matteson, Examination of a Witch, 1853, Wikimedia Commons

Salem Witch Trials:

The Salem Witch Trials in 1692 marked a dark period in American history. Three young girls in Salem Village—Betty Parris, her cousin Abigail Williams, and their friend Ann Putnam Jr.—displayed strange behaviors such as screaming, kicking, throwing objects, and contorting their bodies. A local doctor couldn't find a physical cause for their behavior and attributed the symptoms to witchcraft.

Witch trials and fear of witches had plagued Europe, and those fears had spread to the Americas. These trials typically targeted older women and provided little opportunity for them to defend themselves. Just fifty years prior, for example, hundreds of people, mostly women, were executed for witchcraft.

One early accused woman in America was Ann Hibbens of Boston. She was considered a witch simply for demanding quality work and expressing dissatisfaction with overcharging. Her execution was seen as a punishment for being more vocal than her neighbors.

Salem, Massachusetts became the center of the trials due to demographic displacement from King Philip's War, which reignited old rivalries. As for the three girls, they had traumatic childhoods. In their short lives, they had already been separated from their families, served as servants, and survived attacks by Native warriors. Betty and Abigail, living with troubled parents, sought help from an enslaved woman named Tituba. In a divination ritual, the girls became frightened by the imagery they saw, leading to their accusations of witchcraft.

Reverend Samuel Parris, Betty's father, pressed for answers regarding her behavior. Under pressure, Betty and her friend accused Tituba, Sarah Good (a homeless beggar), and Sarah Osborne (an elderly widow) of witchcraft. These marginalized women were easy targets for the accusations.

Sarah Good's four-year-old daughter, Dorcas, was also accused and imprisoned, enduring months of confinement. While she survived physically, the experience left her mentally disturbed for life.

Ann Putnam Jr. and her family actively accused others. Ann's parents desired inheritances that were rerouted to their stepmother's children, fueling their bitterness. The Putnam family accused 46 different people, and Ann's testimony led to numerous deaths. Her haunting nightmares of her deceased sister and other children contributed to her accusations against Tituba.

These girls didn't independently come up with their accusations. They were influenced by their parents and a legal system that took their claims seriously.

Under pressure and threats of torture, and despite being a devout Christian, Tituba confessed to witchcraft. Enslaved and lacking support, she likely felt she had no other choice. She accused the other two women as well.

The two women denied the accusations but were found guilty and executed. Tituba, spared from execution, remained imprisoned for over a year before being released. She never regained her previous life and died in obscurity.

The hysteria escalated, targeting wealthy and independent women. Martha Corey, convicted based on dubious witness testimonies, was accused of conversing with the devil and using witchcraft to harm others. Despite her denials, she was found guilty and sentenced to death. Rebecca Nurse, an older woman, was dragged from her home and forced to confront her accusers. With no strong defense against their dramatic behavior, she said, "I cannot tell what to think" and cried out for divine help. She was executed alongside four other women.

Increase Mather, the president of Harvard, warned against using "spectral evidence" in court, but the Salem court ignored his plea. Denying witchcraft allegations only fueled the belief in guilt. Mary Easty, a wealthy woman who refused to join the witch hunt, was also convicted and hanged.

While women were the majority of those convicted, men were also accused, often due to rivalries or family disputes. Giles Corey, Martha Corey's husband, was pressed to death with stones for refusing to enter a plea.

The legal process failed during the trials. The girls, primarily from the agrarian side of town, accused older and more powerful individuals from the wealthier side of town. Women constituted 14 out of the 20 convicted, mirroring previous European witch trials. The trials were conducted entirely by male juries, and recent studies suggest that the gender composition of juries influences the outcomes.

The trials ended in 1693 when public outcry led the governor of Massachusetts Bay Colony to dissolve the Court of Oyer and Terminer, responsible for the trials. Many convictions from the trials remain unresolved. The stories of the women involved serve as a reminder of the dangers of fear, superstition, and mass hysteria.

And this was only the beginning.

The Salem Witch Trials in 1692 marked a dark period in American history. Three young girls in Salem Village—Betty Parris, her cousin Abigail Williams, and their friend Ann Putnam Jr.—displayed strange behaviors such as screaming, kicking, throwing objects, and contorting their bodies. A local doctor couldn't find a physical cause for their behavior and attributed the symptoms to witchcraft.

Witch trials and fear of witches had plagued Europe, and those fears had spread to the Americas. These trials typically targeted older women and provided little opportunity for them to defend themselves. Just fifty years prior, for example, hundreds of people, mostly women, were executed for witchcraft.

One early accused woman in America was Ann Hibbens of Boston. She was considered a witch simply for demanding quality work and expressing dissatisfaction with overcharging. Her execution was seen as a punishment for being more vocal than her neighbors.

Salem, Massachusetts became the center of the trials due to demographic displacement from King Philip's War, which reignited old rivalries. As for the three girls, they had traumatic childhoods. In their short lives, they had already been separated from their families, served as servants, and survived attacks by Native warriors. Betty and Abigail, living with troubled parents, sought help from an enslaved woman named Tituba. In a divination ritual, the girls became frightened by the imagery they saw, leading to their accusations of witchcraft.

Reverend Samuel Parris, Betty's father, pressed for answers regarding her behavior. Under pressure, Betty and her friend accused Tituba, Sarah Good (a homeless beggar), and Sarah Osborne (an elderly widow) of witchcraft. These marginalized women were easy targets for the accusations.

Sarah Good's four-year-old daughter, Dorcas, was also accused and imprisoned, enduring months of confinement. While she survived physically, the experience left her mentally disturbed for life.

Ann Putnam Jr. and her family actively accused others. Ann's parents desired inheritances that were rerouted to their stepmother's children, fueling their bitterness. The Putnam family accused 46 different people, and Ann's testimony led to numerous deaths. Her haunting nightmares of her deceased sister and other children contributed to her accusations against Tituba.

These girls didn't independently come up with their accusations. They were influenced by their parents and a legal system that took their claims seriously.

Under pressure and threats of torture, and despite being a devout Christian, Tituba confessed to witchcraft. Enslaved and lacking support, she likely felt she had no other choice. She accused the other two women as well.

The two women denied the accusations but were found guilty and executed. Tituba, spared from execution, remained imprisoned for over a year before being released. She never regained her previous life and died in obscurity.

The hysteria escalated, targeting wealthy and independent women. Martha Corey, convicted based on dubious witness testimonies, was accused of conversing with the devil and using witchcraft to harm others. Despite her denials, she was found guilty and sentenced to death. Rebecca Nurse, an older woman, was dragged from her home and forced to confront her accusers. With no strong defense against their dramatic behavior, she said, "I cannot tell what to think" and cried out for divine help. She was executed alongside four other women.

Increase Mather, the president of Harvard, warned against using "spectral evidence" in court, but the Salem court ignored his plea. Denying witchcraft allegations only fueled the belief in guilt. Mary Easty, a wealthy woman who refused to join the witch hunt, was also convicted and hanged.

While women were the majority of those convicted, men were also accused, often due to rivalries or family disputes. Giles Corey, Martha Corey's husband, was pressed to death with stones for refusing to enter a plea.

The legal process failed during the trials. The girls, primarily from the agrarian side of town, accused older and more powerful individuals from the wealthier side of town. Women constituted 14 out of the 20 convicted, mirroring previous European witch trials. The trials were conducted entirely by male juries, and recent studies suggest that the gender composition of juries influences the outcomes.

The trials ended in 1693 when public outcry led the governor of Massachusetts Bay Colony to dissolve the Court of Oyer and Terminer, responsible for the trials. Many convictions from the trials remain unresolved. The stories of the women involved serve as a reminder of the dangers of fear, superstition, and mass hysteria.

And this was only the beginning.

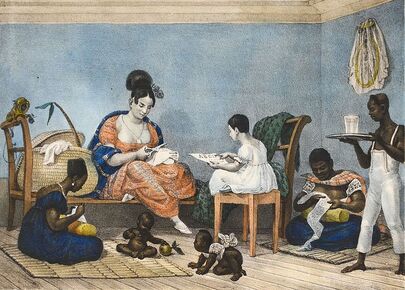

Colonial Life, Wikimedia Commons

Colonial Life, Wikimedia Commons

Life in Colonies:

Despite the grim end to the 1600s, life in the American colonies during the 1700s stabilized and in some ways improved for white women. White women in the American colonies contributed to their household and community’s success and wellbeing through a wide range of responsibilities, like: managing households, including tasks like baking, sewing, educating children, producing soap and candles, and supporting or running family businesses such as farming or shops.

While women had more children compared to today, infant mortality was high, with 1-3 out of 10 children dying before their fifth birthday. Giving birth was also dangerous, with a mortality rate of about 1 in 100 women (today, that number is closer to 32.9 per 100,000 or .0329 in 100). The availability of skilled midwives and the wealth of the colony often impacted maternal and infant mortality rates.

As the colonies stabilized and diversified, social classes started to emerge. In the 1700s women in the middle class often assisted their husbands in taverns, trades, or business ventures. However, despite their contributions, women had limited rights due to the concept of coverture. Coverture meant that women were socially, civilly, and legally represented and protected by their male heads of household, resulting in the denial of property and voting rights. Additionally, even though life expectancy was low, around 46-47 years old, becoming a widowed head of household did not grant women the right to vote.

Nevertheless, partnerships existed. In the colonial era, women were active participants in various cottage industries, such as textile production, pottery, candle making, and soap making. They often worked from home, utilizing their skills and creativity to produce goods that were essential for local consumption and trade. The operation and management of a household depended heavily on women’s work, and her work in the dairy, garden, kitchen, or spinning wheel was just as essential to the family’s well being as what her husband or father did in the fields or on a shipyard. As the Industrial Revolution gained momentum, women continued to be crucial contributors to the expanding manufacturing sector. They worked in factories, mills, and textile industries, operating machinery and performing tasks such as spinning, weaving, and assembling products. Women's labor and expertise were pivotal in fueling the early stages of industrialization, shaping not only the economic landscape but also paving the way for social and political advancements in the years to come.In fact, women and children were actually the most desirable workers in some of the first factories because they had fewer ties to the land and fewer obligations to agrarian farms. Plus, since women working out of the home–especially widows– were assumed to be in poverty and in economic desperation, they were a stable workforce whose labor could be purchased at a minimal cost.

Each colony had its own governing arrangements, with appointed colonial governors and colonial assemblies making decisions about taxes. However, these assemblies began to be disbanded by the British Parliament during the build-up to the American Revolution, which the colonists saw as evidence of corruption. Women had little participation in these political processes.

The colonies had their own distinct characteristics. New England states were heavily Puritan and placed a greater emphasis on education. They specialized in shipbuilding and craftsmanship. Southern colonies focused on cash crops like cotton and tobacco, aiming to export wealth back to England, resulting in fewer investments in cities and schools. The middle colonies, recently acquired from the Dutch, welcomed people from diverse backgrounds and engaged in farming, fishing, and merchant activities.

For free and upper-class women, life was relatively better, and notable outliers like Susanna Wright emerged. Susanna grew up in a Quaker family that emphasized equal education opportunities for girls. On the Pennsylvania frontier, she pursued intellectual and business interests, conducting botanical studies, writing essays, and serving as the chief clerk of the Wright's Ferry court. She advocated for the underprivileged in her community and cared for the sick, delving into medicinal herbs and medical science. Susanna also campaigned for fair treatment of Native communities facing displacement by English settlers, establishing her reputation in the Wright's Ferry community.

With financial independence from her father's successful ferry business and inherited lands, Susanna could pursue her scientific endeavors. She became the first person in Pennsylvania to successfully cultivate silkworms, exporting silk fibers to England for high-quality fabric production. Her achievements contributed to the development of silk worm farms and weaving factories among other colonies.

Susanna's prominence connected her with influential figures of the time, including Benjamin Franklin, with whom she maintained a close friendship. She acknowledged her privilege, recognizing that many women in the colonies had limited opportunities, compelled to subordinate themselves to the wishes of their fathers and husbands due to prevailing laws, religious practices, and social customs.

Despite the grim end to the 1600s, life in the American colonies during the 1700s stabilized and in some ways improved for white women. White women in the American colonies contributed to their household and community’s success and wellbeing through a wide range of responsibilities, like: managing households, including tasks like baking, sewing, educating children, producing soap and candles, and supporting or running family businesses such as farming or shops.

While women had more children compared to today, infant mortality was high, with 1-3 out of 10 children dying before their fifth birthday. Giving birth was also dangerous, with a mortality rate of about 1 in 100 women (today, that number is closer to 32.9 per 100,000 or .0329 in 100). The availability of skilled midwives and the wealth of the colony often impacted maternal and infant mortality rates.

As the colonies stabilized and diversified, social classes started to emerge. In the 1700s women in the middle class often assisted their husbands in taverns, trades, or business ventures. However, despite their contributions, women had limited rights due to the concept of coverture. Coverture meant that women were socially, civilly, and legally represented and protected by their male heads of household, resulting in the denial of property and voting rights. Additionally, even though life expectancy was low, around 46-47 years old, becoming a widowed head of household did not grant women the right to vote.

Nevertheless, partnerships existed. In the colonial era, women were active participants in various cottage industries, such as textile production, pottery, candle making, and soap making. They often worked from home, utilizing their skills and creativity to produce goods that were essential for local consumption and trade. The operation and management of a household depended heavily on women’s work, and her work in the dairy, garden, kitchen, or spinning wheel was just as essential to the family’s well being as what her husband or father did in the fields or on a shipyard. As the Industrial Revolution gained momentum, women continued to be crucial contributors to the expanding manufacturing sector. They worked in factories, mills, and textile industries, operating machinery and performing tasks such as spinning, weaving, and assembling products. Women's labor and expertise were pivotal in fueling the early stages of industrialization, shaping not only the economic landscape but also paving the way for social and political advancements in the years to come.In fact, women and children were actually the most desirable workers in some of the first factories because they had fewer ties to the land and fewer obligations to agrarian farms. Plus, since women working out of the home–especially widows– were assumed to be in poverty and in economic desperation, they were a stable workforce whose labor could be purchased at a minimal cost.

Each colony had its own governing arrangements, with appointed colonial governors and colonial assemblies making decisions about taxes. However, these assemblies began to be disbanded by the British Parliament during the build-up to the American Revolution, which the colonists saw as evidence of corruption. Women had little participation in these political processes.

The colonies had their own distinct characteristics. New England states were heavily Puritan and placed a greater emphasis on education. They specialized in shipbuilding and craftsmanship. Southern colonies focused on cash crops like cotton and tobacco, aiming to export wealth back to England, resulting in fewer investments in cities and schools. The middle colonies, recently acquired from the Dutch, welcomed people from diverse backgrounds and engaged in farming, fishing, and merchant activities.

For free and upper-class women, life was relatively better, and notable outliers like Susanna Wright emerged. Susanna grew up in a Quaker family that emphasized equal education opportunities for girls. On the Pennsylvania frontier, she pursued intellectual and business interests, conducting botanical studies, writing essays, and serving as the chief clerk of the Wright's Ferry court. She advocated for the underprivileged in her community and cared for the sick, delving into medicinal herbs and medical science. Susanna also campaigned for fair treatment of Native communities facing displacement by English settlers, establishing her reputation in the Wright's Ferry community.

With financial independence from her father's successful ferry business and inherited lands, Susanna could pursue her scientific endeavors. She became the first person in Pennsylvania to successfully cultivate silkworms, exporting silk fibers to England for high-quality fabric production. Her achievements contributed to the development of silk worm farms and weaving factories among other colonies.

Susanna's prominence connected her with influential figures of the time, including Benjamin Franklin, with whom she maintained a close friendship. She acknowledged her privilege, recognizing that many women in the colonies had limited opportunities, compelled to subordinate themselves to the wishes of their fathers and husbands due to prevailing laws, religious practices, and social customs.

Woman Whipping an Indenture, Wikimedia Commons

Woman Whipping an Indenture, Wikimedia Commons

Indentured Women:

Many poor immigrants to the English colonies arrived as indentured servants, and faced a challenging and difficult experience. Indentured servitude involved signing a contract, or "indenture," which obligated individuals to work for a specific period in exchange for passage to the colonies and possibly the opportunity to learn a trade. This system affected people of different races, including whites, Indigenous individuals, and Blacks.

For women from impoverished backgrounds or without family support, indentured servitude became a means of survival. Poverty, debt, or unfavorable circumstances in their home countries drove many women to become indentured servants. Elizabeth Ashbridge, for instance, was a young, poor, and widowed English Quaker who came to the Americas as an indenture after being disowned by her father. The woman who convinced her to travel back to Pennsylvania bound her before boarding the ship. Ashbridge worked diligently to quickly pay off her indenture. Over time, she found faith and wrote an autobiography about her life as an influential religious leader during the revolutionary period.

Terms of indenture varied, usually lasting from four to seven years. Throughout this period, servants worked for their masters without receiving wages. Their tasks ranged from household chores to fieldwork or skilled trades, depending on their abilities and the needs of their masters.This also was usually determined by the type of indenture that they had. Apprenticeships were the most favorable type of indenture as the laborer would learn some type of handicraft, trade, or profession. These were typically male indenture agreements. Apprenticeships were rare, though, and most indenture agreements simply involved service. They endured physically demanding labor, often working long hours with minimal rest or leisure time. Living conditions were basic and crowded, with servants sharing small quarters and lacking privacy.

Indentured servants were considered the property of their masters and could be bought, sold, or transferred without their consent. Physical abuse, sexual exploitation, and mistreatment were common occurrences that often went unpunished due to the servants' legal status. Pregnancy posed additional challenges, as some women faced the prospect of raising a child while still in servitude. Despite the opportunity for a fresh start in the colonies, female servants found it difficult to improve their social standing or achieve economic independence. They encountered social stigma and had limited opportunities to acquire new skills or advance in society.

Upon completing their indentured servitude, female servants gained their freedom, but their prospects for a better life remained limited. Some indenture agreements had terms that provided for “freedom dues.” “Freedom dues” were farewell gifts of sorts. For apprentices, this might include the tools that would be necessary for the apprentice to establish their own business. Some indentured servant agreements indicated that the servant would receive a small parcel of land. These “freedom dues” varied from contract to contract–some agreements did not include “freedom dues,” but those that did were highly gendered. For men who were leaving their indenture to become self-sufficient heads of household, their “freedom dues” in the form of tools, materials, supplies, or land would help establish them on their way to self-mastery. For women, who were not expected to own land, their “freedom dues,” (if they received any) had to be small so that they could take them with them when they presumably married and moved onto the property that their husbands owned. We know, for example, of one indenture, Willy Honywell, who was to receive 25 acres of land and 12 bushels of corn once he completed his seven years of service. On the other hand, Alice Grinder, another indentured servant around the same time, only received two new outfits. Some women, upon completion of their indenture, managed to establish their own households or find employment, while many struggled to secure stable jobs and faced ongoing difficulties.

While there were some similarities between the status of indentured servants and the status of enslaved people (specifically the limits on their freedom during the tenure of their indenture in the form of rules governing marriage, and the ability to have their contract transferred or sold–usually upon the death of their master) it is important to note that indenture contracts eventually expired, indentured servants had a bit of free will, usually had to approve of their indenture agreement being sold or transferred, and had legal resources. Altogether, these distinctions in their situation made indentured servitude different from the lifelong servitude endured by enslaved individuals.

Many poor immigrants to the English colonies arrived as indentured servants, and faced a challenging and difficult experience. Indentured servitude involved signing a contract, or "indenture," which obligated individuals to work for a specific period in exchange for passage to the colonies and possibly the opportunity to learn a trade. This system affected people of different races, including whites, Indigenous individuals, and Blacks.

For women from impoverished backgrounds or without family support, indentured servitude became a means of survival. Poverty, debt, or unfavorable circumstances in their home countries drove many women to become indentured servants. Elizabeth Ashbridge, for instance, was a young, poor, and widowed English Quaker who came to the Americas as an indenture after being disowned by her father. The woman who convinced her to travel back to Pennsylvania bound her before boarding the ship. Ashbridge worked diligently to quickly pay off her indenture. Over time, she found faith and wrote an autobiography about her life as an influential religious leader during the revolutionary period.

Terms of indenture varied, usually lasting from four to seven years. Throughout this period, servants worked for their masters without receiving wages. Their tasks ranged from household chores to fieldwork or skilled trades, depending on their abilities and the needs of their masters.This also was usually determined by the type of indenture that they had. Apprenticeships were the most favorable type of indenture as the laborer would learn some type of handicraft, trade, or profession. These were typically male indenture agreements. Apprenticeships were rare, though, and most indenture agreements simply involved service. They endured physically demanding labor, often working long hours with minimal rest or leisure time. Living conditions were basic and crowded, with servants sharing small quarters and lacking privacy.

Indentured servants were considered the property of their masters and could be bought, sold, or transferred without their consent. Physical abuse, sexual exploitation, and mistreatment were common occurrences that often went unpunished due to the servants' legal status. Pregnancy posed additional challenges, as some women faced the prospect of raising a child while still in servitude. Despite the opportunity for a fresh start in the colonies, female servants found it difficult to improve their social standing or achieve economic independence. They encountered social stigma and had limited opportunities to acquire new skills or advance in society.

Upon completing their indentured servitude, female servants gained their freedom, but their prospects for a better life remained limited. Some indenture agreements had terms that provided for “freedom dues.” “Freedom dues” were farewell gifts of sorts. For apprentices, this might include the tools that would be necessary for the apprentice to establish their own business. Some indentured servant agreements indicated that the servant would receive a small parcel of land. These “freedom dues” varied from contract to contract–some agreements did not include “freedom dues,” but those that did were highly gendered. For men who were leaving their indenture to become self-sufficient heads of household, their “freedom dues” in the form of tools, materials, supplies, or land would help establish them on their way to self-mastery. For women, who were not expected to own land, their “freedom dues,” (if they received any) had to be small so that they could take them with them when they presumably married and moved onto the property that their husbands owned. We know, for example, of one indenture, Willy Honywell, who was to receive 25 acres of land and 12 bushels of corn once he completed his seven years of service. On the other hand, Alice Grinder, another indentured servant around the same time, only received two new outfits. Some women, upon completion of their indenture, managed to establish their own households or find employment, while many struggled to secure stable jobs and faced ongoing difficulties.

While there were some similarities between the status of indentured servants and the status of enslaved people (specifically the limits on their freedom during the tenure of their indenture in the form of rules governing marriage, and the ability to have their contract transferred or sold–usually upon the death of their master) it is important to note that indenture contracts eventually expired, indentured servants had a bit of free will, usually had to approve of their indenture agreement being sold or transferred, and had legal resources. Altogether, these distinctions in their situation made indentured servitude different from the lifelong servitude endured by enslaved individuals.

Slaves Waiting for Sale - Richmond, Virginia by Eyre Crowe, 1853.

Slaves Waiting for Sale - Richmond, Virginia by Eyre Crowe, 1853.

Enslaved Women:

Enslaved women and girls had no such privileges. From a young age, girls were assigned small tasks like picking up trash, tending to younger children, cleaning cotton, or scaring birds away from newly planted rice fields. As they reached adolescence, enslaved girls typically took on more regular labor. Older women who could no longer work in the fields were sometimes tasked with caring for enslaved children. The work patterns of enslaved women varied throughout their lives and according to the region they were in as enslavers aimed to extract maximum profits from their labor.

Apart from their physical and reproductive labor, enslaved women were subjected to the oppressive demands of fulfilling the sexual desires of slaveholders, overseers, and other men in positions of power. The colony of Virginia, quickly followed by other colonies, passed a law in 1662 that laid out the principle of partus sequitur ventrem, or, “that which is born follows the womb.” This essentially dictated that the status of any child born would be based on the status–free or enslaved–of its mother and regardless of their father's legal standing. In other words, enslaved women gave birth to children who would inherit the status of slavery. While this was described as a way to settle questions about whether children should be free or enslaved based on some current questions the colony was having, it alsogave slave owners incentives to rape their enslaved women in order for them to produce more slaves. Obviously this cast a long shadow over the lives of enslaved women. While enslaved women’s experiences in slavery share many aspects in common with their male counterparts, the reality is also that for enslaved women, this reproductive dimension added another dimension to their experiences that cannot wholly be understood by the rest of us. Because enslaved women were workers, mothers, and survivors of sexual assault (enslaved women cannot provide true consent), one historian has argued that enslaved women were then “either especially oppressed or comparatively privileged” (perhaps in terms of material comfort).

Women dominated the ranks of the enslaved people who worked in the homes of slaveholders because this work was considered "domestic" and traditionally associated with women and girls. House duties encompassed a wide range of responsibilities, including cleaning, cooking, washing, and caring for all members of the white family, from adults to infants. Consequently, many enslaved women of various ages spent a significant portion of their adult lives working within the homes of their white enslavers. These women were both close to their enslavers and also more monitored by them: which proved to be a strange predicament. Many of these women dedicated their time to caring for children, undertaking tasks such as clothing, feeding, and bathing them. Enslaved women who were lactating (producing milk) even served as wet nurses for white infants, sometimes being forced to wean their own child early in order to prioritize the wellbeing of their masters’ baby.

Gradually, slaveholders created a stereotype of an older domestic woman, often known as the "mammy." Typically, this caricature was of a loyal, overweight or obese woman who was conventionally unattractive yet devoted to the family. This trope of a Black woman: solely devoted to her work and obedient, was used to justify slavery. Enslavers argued these women wouldn’t be so obedient if they didn’t really love the family that enslaved them. This caricature was also used as a shield to cover for some of the sexual abuses taking place within the Southern home. The mammy caricature is explicitly desexualized. She was designed to portray unattractiveness. This move to convey the mammy as older and overweight implicitly meant that the slave owner’s wife and family were safe. No reasonable white man would want to have sex with her. Though we know that sexual assault, and unequal relationships existed between masters and enslaved women, the mammy lie conveyed the idea that Black women were undesirable, existed to serve white families, and supported the institution of slavery.

White women often upheld the system of slavery and benefited from it. The typical female slave owner, as well as the average male slave owner, claimed legal ownership of 10 enslaved individuals or fewer. It is important to remember that most slaves in the South were concentrated in the hands of a small share of slave owners. Over time in the South, the proportion of those southerners who owned slaves shrank. The vast majority of slaveowners in the South were of the small farm or middling sort. These slaveowners had less than ten, but no more than 50 slaves. The elite among slaveowners held in their possession 50 slaves or more, and the best land, and enough of it to make that investment in labor profitable. That being said, in most cases, their ownership extended to fewer than five people. Young white girls often received enslaved people as gifts, even as infants. As when we talked about indentured servants and their freedom dues, those gifts needed to be something that the women could take with them. It was not uncommon for women to receive slaves as wedding gifts–particularly with the expectation that they might serve as wet nurses when the bride became pregnant. Women also purchased them from slave markets across the Southern region. White women were a part of the culture of slavery. While their responses to slavery varied, most were responsible for at least directing the house slave and clothing and feeding their slaves. Like men, Southern slave owning women could be benevolent enslavers, or they could be incredibly cruel, and were just as likely to inflict violent punishments upon their slaves. One woman starved her enslaved people and taunted them with candies. When one girl succumbed to her hunger, the slaver rocked her rocking chair atop the girl's head while her daughter whipped her, permanently deforming her jaw. The inclusion of her white daughter as the whipper shows how the violence of slavery was something that was taught from generation to generation.

Enslaved women and girls had no such privileges. From a young age, girls were assigned small tasks like picking up trash, tending to younger children, cleaning cotton, or scaring birds away from newly planted rice fields. As they reached adolescence, enslaved girls typically took on more regular labor. Older women who could no longer work in the fields were sometimes tasked with caring for enslaved children. The work patterns of enslaved women varied throughout their lives and according to the region they were in as enslavers aimed to extract maximum profits from their labor.

Apart from their physical and reproductive labor, enslaved women were subjected to the oppressive demands of fulfilling the sexual desires of slaveholders, overseers, and other men in positions of power. The colony of Virginia, quickly followed by other colonies, passed a law in 1662 that laid out the principle of partus sequitur ventrem, or, “that which is born follows the womb.” This essentially dictated that the status of any child born would be based on the status–free or enslaved–of its mother and regardless of their father's legal standing. In other words, enslaved women gave birth to children who would inherit the status of slavery. While this was described as a way to settle questions about whether children should be free or enslaved based on some current questions the colony was having, it alsogave slave owners incentives to rape their enslaved women in order for them to produce more slaves. Obviously this cast a long shadow over the lives of enslaved women. While enslaved women’s experiences in slavery share many aspects in common with their male counterparts, the reality is also that for enslaved women, this reproductive dimension added another dimension to their experiences that cannot wholly be understood by the rest of us. Because enslaved women were workers, mothers, and survivors of sexual assault (enslaved women cannot provide true consent), one historian has argued that enslaved women were then “either especially oppressed or comparatively privileged” (perhaps in terms of material comfort).

Women dominated the ranks of the enslaved people who worked in the homes of slaveholders because this work was considered "domestic" and traditionally associated with women and girls. House duties encompassed a wide range of responsibilities, including cleaning, cooking, washing, and caring for all members of the white family, from adults to infants. Consequently, many enslaved women of various ages spent a significant portion of their adult lives working within the homes of their white enslavers. These women were both close to their enslavers and also more monitored by them: which proved to be a strange predicament. Many of these women dedicated their time to caring for children, undertaking tasks such as clothing, feeding, and bathing them. Enslaved women who were lactating (producing milk) even served as wet nurses for white infants, sometimes being forced to wean their own child early in order to prioritize the wellbeing of their masters’ baby.

Gradually, slaveholders created a stereotype of an older domestic woman, often known as the "mammy." Typically, this caricature was of a loyal, overweight or obese woman who was conventionally unattractive yet devoted to the family. This trope of a Black woman: solely devoted to her work and obedient, was used to justify slavery. Enslavers argued these women wouldn’t be so obedient if they didn’t really love the family that enslaved them. This caricature was also used as a shield to cover for some of the sexual abuses taking place within the Southern home. The mammy caricature is explicitly desexualized. She was designed to portray unattractiveness. This move to convey the mammy as older and overweight implicitly meant that the slave owner’s wife and family were safe. No reasonable white man would want to have sex with her. Though we know that sexual assault, and unequal relationships existed between masters and enslaved women, the mammy lie conveyed the idea that Black women were undesirable, existed to serve white families, and supported the institution of slavery.

White women often upheld the system of slavery and benefited from it. The typical female slave owner, as well as the average male slave owner, claimed legal ownership of 10 enslaved individuals or fewer. It is important to remember that most slaves in the South were concentrated in the hands of a small share of slave owners. Over time in the South, the proportion of those southerners who owned slaves shrank. The vast majority of slaveowners in the South were of the small farm or middling sort. These slaveowners had less than ten, but no more than 50 slaves. The elite among slaveowners held in their possession 50 slaves or more, and the best land, and enough of it to make that investment in labor profitable. That being said, in most cases, their ownership extended to fewer than five people. Young white girls often received enslaved people as gifts, even as infants. As when we talked about indentured servants and their freedom dues, those gifts needed to be something that the women could take with them. It was not uncommon for women to receive slaves as wedding gifts–particularly with the expectation that they might serve as wet nurses when the bride became pregnant. Women also purchased them from slave markets across the Southern region. White women were a part of the culture of slavery. While their responses to slavery varied, most were responsible for at least directing the house slave and clothing and feeding their slaves. Like men, Southern slave owning women could be benevolent enslavers, or they could be incredibly cruel, and were just as likely to inflict violent punishments upon their slaves. One woman starved her enslaved people and taunted them with candies. When one girl succumbed to her hunger, the slaver rocked her rocking chair atop the girl's head while her daughter whipped her, permanently deforming her jaw. The inclusion of her white daughter as the whipper shows how the violence of slavery was something that was taught from generation to generation.

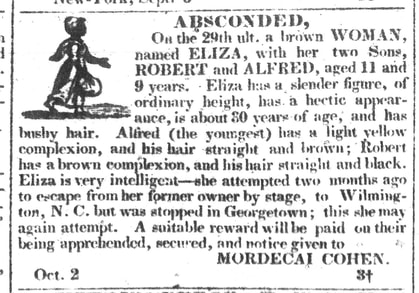

Absconded, Runaway Slave Advertisement for Eliza, Public Domain

Absconded, Runaway Slave Advertisement for Eliza, Public Domain

Rebel Women:

Enslaved people actively resisted slavery, by rebelling, slowing down work, and running away. Enslaved women and girls sought freedom as soon as they arrived in the Americas, with some choosing collective escapes while others fled individually. The timing of their escapes varied, as some women made their break for freedom immediately upon arrival, while others did so within weeks or even months later. An example is Juno, a fifteen-year-old girl who arrived on the slave ship Speaker in Charleston, SC on June 16, 1733. Just two weeks after being sold to a planter from Dorchester, Juno managed to escape. These acts of self-emancipation by enslaved Black individuals show the consistency with which women resisted bondage.

Some responded with violence to the violence they endured as slaves. In 1708, an enslaved Indigenous man named Sam and a woman identified only as a "Negro Fiend" murdered their master and his pregnant wife, leading to their capture. Sam was hanged, and the woman was burned at the stake due to an English law regarding treason. A few years later, a significant rebellion occurred in New York in 1712, involving Black slaves who killed nine white individuals and injured six others. The uprising resulted in the arrest of over 70 enslaved people, with 27 put on trial, including four women named Sarah, Abigail, Lily, and Amba. The historical record provides limited information on these women's opinions, except for a statement indicating they had made previous statements for themselves. Sarah and Abigail, along with 19 others, were convicted and sentenced to death. However, one of the women was pregnant, leading to a delayed hanging. The fate of the unnamed girl remained uncertain due to political turmoil in England.

Rebellions continued across the colonies, with the New York governor's house being destroyed by a fire in 1741. Multiple fires occurred in subsequent days, leading to suspicions of another rebellion. A white indentured servant named Mary Burton claimed a conspiracy involving dozens of enslaved people attempting to overthrow the colonial government, causing panic among white individuals. Sarah, an enslaved woman, was accused by four people of deep involvement, resulting in her collapsing in fits and foaming at the mouth during court proceedings. Sarah faced intense interrogation, leading to the execution of alleged conspirators. As a consequence, she was sent to a sugar plantation in the Caribbean, essentially a death sentence.

While rebellions demonstrated the humanity and desire for autonomy and freedom among enslaved people, they also resulted in tighter control and scrutiny over the enslaved population. For example, a rebellion in South Carolina in 1739 led to laws requiring a 1:10 ratio between slave masters and slaves as well as imposing prohibitions on growing their own food, assembling in groups, earning money, and learning to read.

Enslaved people actively resisted slavery, by rebelling, slowing down work, and running away. Enslaved women and girls sought freedom as soon as they arrived in the Americas, with some choosing collective escapes while others fled individually. The timing of their escapes varied, as some women made their break for freedom immediately upon arrival, while others did so within weeks or even months later. An example is Juno, a fifteen-year-old girl who arrived on the slave ship Speaker in Charleston, SC on June 16, 1733. Just two weeks after being sold to a planter from Dorchester, Juno managed to escape. These acts of self-emancipation by enslaved Black individuals show the consistency with which women resisted bondage.

Some responded with violence to the violence they endured as slaves. In 1708, an enslaved Indigenous man named Sam and a woman identified only as a "Negro Fiend" murdered their master and his pregnant wife, leading to their capture. Sam was hanged, and the woman was burned at the stake due to an English law regarding treason. A few years later, a significant rebellion occurred in New York in 1712, involving Black slaves who killed nine white individuals and injured six others. The uprising resulted in the arrest of over 70 enslaved people, with 27 put on trial, including four women named Sarah, Abigail, Lily, and Amba. The historical record provides limited information on these women's opinions, except for a statement indicating they had made previous statements for themselves. Sarah and Abigail, along with 19 others, were convicted and sentenced to death. However, one of the women was pregnant, leading to a delayed hanging. The fate of the unnamed girl remained uncertain due to political turmoil in England.

Rebellions continued across the colonies, with the New York governor's house being destroyed by a fire in 1741. Multiple fires occurred in subsequent days, leading to suspicions of another rebellion. A white indentured servant named Mary Burton claimed a conspiracy involving dozens of enslaved people attempting to overthrow the colonial government, causing panic among white individuals. Sarah, an enslaved woman, was accused by four people of deep involvement, resulting in her collapsing in fits and foaming at the mouth during court proceedings. Sarah faced intense interrogation, leading to the execution of alleged conspirators. As a consequence, she was sent to a sugar plantation in the Caribbean, essentially a death sentence.

While rebellions demonstrated the humanity and desire for autonomy and freedom among enslaved people, they also resulted in tighter control and scrutiny over the enslaved population. For example, a rebellion in South Carolina in 1739 led to laws requiring a 1:10 ratio between slave masters and slaves as well as imposing prohibitions on growing their own food, assembling in groups, earning money, and learning to read.

Great Awakening, Wikimedia Commons

Great Awakening, Wikimedia Commons

First Great Awakening:

Whether white, Black, free, indentured, or enslaved, religion and religious beliefs played an important role in the American colonies. The First Great Awakening in the 1730s-40s had a significant impact on women's subordinate status in the colonies. It was a period of intense religious enthusiasm that marked a significant shift in the religious landscape as many Americans renewed their commitment to God. The prevailing belief emphasized God's unlimited power and the necessity of fearing and following Him to attain salvation and avoid damnation. Notably, a large number of enslaved and Indigenous people converted to Christianity during this time.

Unlike previous emphasis on formal theology, the focus during the Great Awakening shifted to cultivating personal experiences of salvation and fostering a heartfelt connection with God. This revival sparked the emergence of a new generation of ministers, including women. However, these religious women were still constrained by societal expectations and the view that women's involvement in public or mixed-gender settings was improper. Nonetheless, women found ways to participate.

For instance, Mary Reed had visions that she shared privately with her minister, who then relayed them to the congregation while Mary remained calmly seated in the pews. Her humble demeanor bestowed authority upon her words among the worshipers. Although women were not allowed to publicly preach in the church, a notable difference with Great Awakening preachers was that they took their message outside the church to the unconverted. In open-air settings, women's voices could be heard.

Martha Stearns Marshall was a renowned preacher who moved her congregation to tears. She and her husband underwent a conversion during the revival, leading them to live among the Mohawk Indians in an attempt to bring them to Christianity. When war broke out, they settled in Virginia, North Carolina, and later Georgia. The Separate Baptists church Marshall belonged to differed from the "Regular" Baptists in that they granted women a more prominent role in worship and church leadership. Women served as deaconesses and eldresses and actively engaged in preaching.

Marshall was not the only influential female preacher. Sarah Wright Townsend, a Long Island school teacher, exhorted for over fifteen years on Sundays. Bathsheba Kingsley, known as the "brawling woman," fearlessly embarked on a journey from town to town, spreading the message of faith and confronting townsfolk about their sinful ways. Jamima Wilkinson transcended gender boundaries and delivered passionate sermons, evoking both fascination and disgust while adorned in a flowing robe.

Some women struggled to navigate the complexities of spiritual equality and social inferiority. Margaret Meuse Clay, a pious woman, was asked to lead public prayers in her church. However, her preaching was deemed excessive, leading to her and eleven male Baptists being sentenced to a public whipping for unlicensed preaching. She was spared when an unnamed man paid her fine. These struggles were compounded by factors such as race and class.Though evidence is fragmentary, it is believed that enslaved women may have served as evangelists on plantations. Stories passed down through later generations of slaves mention grandmothers and great-grandmothers exhorting in slave quarters.

Religion deeply influenced various aspects of women's lives, shaping their perspectives on suffering, marriage, motherhood, the body, and sexuality. For countless women, religion served as a guiding force, providing a sense of direction and allowing them to comprehend their position in the world. The societal changes brought about by the Great Awakening were remarkable, with traditional roles shifting as wives encouraged their husbands to pursue piety. Children became evangelists for their parents, and in a bold move, some women spoke publicly about their faith. As described by one Reverend, many individuals became so deeply engrossed in their religious fervor that they appeared temporarily disconnected from reality.

Whether white, Black, free, indentured, or enslaved, religion and religious beliefs played an important role in the American colonies. The First Great Awakening in the 1730s-40s had a significant impact on women's subordinate status in the colonies. It was a period of intense religious enthusiasm that marked a significant shift in the religious landscape as many Americans renewed their commitment to God. The prevailing belief emphasized God's unlimited power and the necessity of fearing and following Him to attain salvation and avoid damnation. Notably, a large number of enslaved and Indigenous people converted to Christianity during this time.

Unlike previous emphasis on formal theology, the focus during the Great Awakening shifted to cultivating personal experiences of salvation and fostering a heartfelt connection with God. This revival sparked the emergence of a new generation of ministers, including women. However, these religious women were still constrained by societal expectations and the view that women's involvement in public or mixed-gender settings was improper. Nonetheless, women found ways to participate.

For instance, Mary Reed had visions that she shared privately with her minister, who then relayed them to the congregation while Mary remained calmly seated in the pews. Her humble demeanor bestowed authority upon her words among the worshipers. Although women were not allowed to publicly preach in the church, a notable difference with Great Awakening preachers was that they took their message outside the church to the unconverted. In open-air settings, women's voices could be heard.

Martha Stearns Marshall was a renowned preacher who moved her congregation to tears. She and her husband underwent a conversion during the revival, leading them to live among the Mohawk Indians in an attempt to bring them to Christianity. When war broke out, they settled in Virginia, North Carolina, and later Georgia. The Separate Baptists church Marshall belonged to differed from the "Regular" Baptists in that they granted women a more prominent role in worship and church leadership. Women served as deaconesses and eldresses and actively engaged in preaching.

Marshall was not the only influential female preacher. Sarah Wright Townsend, a Long Island school teacher, exhorted for over fifteen years on Sundays. Bathsheba Kingsley, known as the "brawling woman," fearlessly embarked on a journey from town to town, spreading the message of faith and confronting townsfolk about their sinful ways. Jamima Wilkinson transcended gender boundaries and delivered passionate sermons, evoking both fascination and disgust while adorned in a flowing robe.

Some women struggled to navigate the complexities of spiritual equality and social inferiority. Margaret Meuse Clay, a pious woman, was asked to lead public prayers in her church. However, her preaching was deemed excessive, leading to her and eleven male Baptists being sentenced to a public whipping for unlicensed preaching. She was spared when an unnamed man paid her fine. These struggles were compounded by factors such as race and class.Though evidence is fragmentary, it is believed that enslaved women may have served as evangelists on plantations. Stories passed down through later generations of slaves mention grandmothers and great-grandmothers exhorting in slave quarters.

Religion deeply influenced various aspects of women's lives, shaping their perspectives on suffering, marriage, motherhood, the body, and sexuality. For countless women, religion served as a guiding force, providing a sense of direction and allowing them to comprehend their position in the world. The societal changes brought about by the Great Awakening were remarkable, with traditional roles shifting as wives encouraged their husbands to pursue piety. Children became evangelists for their parents, and in a bold move, some women spoke publicly about their faith. As described by one Reverend, many individuals became so deeply engrossed in their religious fervor that they appeared temporarily disconnected from reality.

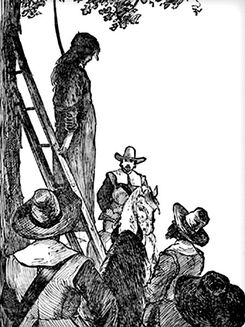

Engraving of a Women at Execution, Public Domain

Engraving of a Women at Execution, Public Domain

Colonial Laws:

Whether enslaved, Indigenous, or white, upper class or lower class, women suffered under a prejudiced legal system. Problems evident at Salem, still existed by the end of the colonial period. Women took no part in designing laws and could be accused, arrested, tried, and executed by all-male rule makers and enforcers. In the colonial period, we can learn a lot about the lives of women through court records, although we have taken these sources with a grain of salt. They are not representative of the majority of women, instead these are examples of the more extreme experiences women had. Furthermore, many of these sources were written by men about the women who were accused, and we rarely have sources provided by the women themselves. Based on verifiable sources, women were mostly executed on charges related to murder, attempted murder, or conspiracy to commit murder. Some were charged with witchcraft, and not just in Massachusetts. In fact, the first woman executed for witchcraft was in Virginia. Still others were accused of arson and one woman was executed for the crime of adultery.

Aside from those criminal acts, having a child outside of wedlock carried significant social stigma in colonial America. For example, when Anne Orthwood became pregnant out of wedlock with twins in late 17th century Virginia, she became the subject of four different cases–civil and criminal–stemming from her indenture being affected by her pregnancy, demands for child support, criminal fornication, and then a case much later when her only surviving twin tried to free himself from his indenture (Anne, unfortunately, died in childbirth). Orthwood’s case was unique because the father of her child was related to a wealthy politician. Anne’s status as an indentured servant likely played a role in her lover’s decision to end the relationship and deny paternity.

To cope with a rigid society in a time before effective contraceptives and sex education, abortion was common and legal up until the “quickening period.” Quickening was when the mother experienced fetal movement. Some women likely induced miscarriages because they feared social stigma, but that wasn’t always the case.Some women knew they could not provide for their babies emotionally, financially, or physically.

Some women were charged with infanticide, infanticide is the act of killing an infant after it is born. While this crime is hard to imagine or understand, it’s important to refrain from looking at these issues through our modern lens and to attempt to humanize the subjects we study. In a time before formula or intravenous nutrition, and when infant mortality was high, a mother who couldn’t breastfeed, or a child who was ill or wouldn’t latch, there weren’t really options outside of a wet nurse. Animal milk is bad for infant digestive systems and wouldn’t have helped. If another lactating woman was not available, these poor mothers were often stuck in the impossible scenario of watching their baby starve, or ending their suffering. It’s hard to imagine the pain of then being charged with murdering your child–particularly when we consider the circumstances that led to it.

Women were heavily policed under English law in order to protect paternity, fatherhood, and property. At one point, concealing the birth of an illegitimate child was also considered a capital offense. Concealment was punishable by death if the baby did not survive. With no one to witness a “concealed” birth, there was no one to prove that the child had been born dead and–perhaps in a recognition of the social stigma of a child out of wedlock–the dead infant was considered a murder victim unless the mother could prove her innocence. Five women in colonial America were hanged for concealing pregnancies: three in New Hampshire alone. Again, the legal system failed women. The burden of proof did not require evidence of intent. These laws were later seen as symbolic of the corruption of the British crown, but were probably more symbolic of the rampant misogyny embedded in these systems that stripped women of their personhood.

Ruth Blay was one of the women executed in New Hampshire for concealment. She was a poor school teacher who was likely impregnated by a prominent married man in her community. When she realized she was pregnant she left her teaching post to live with distant relatives with whom there was a generations old family feud that she hoped would not be used against her. When she went into labor, she delivered alone in a barn. The baby was stillborn and soon discovered by children buried under the barn. Blay was inspected by local male physicians and accused of concealment.

She was dragged from her temporary home to a prison in Portsmouth. Her siblings came and testified on her behalf, but whatever they said in defense is lost. The entirely male jury found her guilty. The colonial governor gave her reprieves but eventually she was hanged from a tree in December 1768, like all the women at Salem before her, by a legal system that gave women little choices.

The day after Ruth was hanged, she published her last words in the paper: “The time being now short after returning Thanks to all Friends for the kindness shown me, I must bid them farewell… my Conscience is clear with respect to my poor Infant;-- And though I die with a forgiving Spirit as to all my Enemies, but charge two women in particular to examine their own Hearts, as they will answer to it another day– whether they do not come under the Character of false witnesses?-- And whether Prejudice, Jealousy, or something else has not drove them thus to bear false Witness against me.”

Why did women at Salem tell on each other? Why did white women enslave their Black sisters and steal land from their Indigenous sisters? Why did women testify against each other, like with Ruth? Would things have been different with education, rights, and a voice in public spaces? We can only speculate.

Whether enslaved, Indigenous, or white, upper class or lower class, women suffered under a prejudiced legal system. Problems evident at Salem, still existed by the end of the colonial period. Women took no part in designing laws and could be accused, arrested, tried, and executed by all-male rule makers and enforcers. In the colonial period, we can learn a lot about the lives of women through court records, although we have taken these sources with a grain of salt. They are not representative of the majority of women, instead these are examples of the more extreme experiences women had. Furthermore, many of these sources were written by men about the women who were accused, and we rarely have sources provided by the women themselves. Based on verifiable sources, women were mostly executed on charges related to murder, attempted murder, or conspiracy to commit murder. Some were charged with witchcraft, and not just in Massachusetts. In fact, the first woman executed for witchcraft was in Virginia. Still others were accused of arson and one woman was executed for the crime of adultery.

Aside from those criminal acts, having a child outside of wedlock carried significant social stigma in colonial America. For example, when Anne Orthwood became pregnant out of wedlock with twins in late 17th century Virginia, she became the subject of four different cases–civil and criminal–stemming from her indenture being affected by her pregnancy, demands for child support, criminal fornication, and then a case much later when her only surviving twin tried to free himself from his indenture (Anne, unfortunately, died in childbirth). Orthwood’s case was unique because the father of her child was related to a wealthy politician. Anne’s status as an indentured servant likely played a role in her lover’s decision to end the relationship and deny paternity.

To cope with a rigid society in a time before effective contraceptives and sex education, abortion was common and legal up until the “quickening period.” Quickening was when the mother experienced fetal movement. Some women likely induced miscarriages because they feared social stigma, but that wasn’t always the case.Some women knew they could not provide for their babies emotionally, financially, or physically.

Some women were charged with infanticide, infanticide is the act of killing an infant after it is born. While this crime is hard to imagine or understand, it’s important to refrain from looking at these issues through our modern lens and to attempt to humanize the subjects we study. In a time before formula or intravenous nutrition, and when infant mortality was high, a mother who couldn’t breastfeed, or a child who was ill or wouldn’t latch, there weren’t really options outside of a wet nurse. Animal milk is bad for infant digestive systems and wouldn’t have helped. If another lactating woman was not available, these poor mothers were often stuck in the impossible scenario of watching their baby starve, or ending their suffering. It’s hard to imagine the pain of then being charged with murdering your child–particularly when we consider the circumstances that led to it.

Women were heavily policed under English law in order to protect paternity, fatherhood, and property. At one point, concealing the birth of an illegitimate child was also considered a capital offense. Concealment was punishable by death if the baby did not survive. With no one to witness a “concealed” birth, there was no one to prove that the child had been born dead and–perhaps in a recognition of the social stigma of a child out of wedlock–the dead infant was considered a murder victim unless the mother could prove her innocence. Five women in colonial America were hanged for concealing pregnancies: three in New Hampshire alone. Again, the legal system failed women. The burden of proof did not require evidence of intent. These laws were later seen as symbolic of the corruption of the British crown, but were probably more symbolic of the rampant misogyny embedded in these systems that stripped women of their personhood.

Ruth Blay was one of the women executed in New Hampshire for concealment. She was a poor school teacher who was likely impregnated by a prominent married man in her community. When she realized she was pregnant she left her teaching post to live with distant relatives with whom there was a generations old family feud that she hoped would not be used against her. When she went into labor, she delivered alone in a barn. The baby was stillborn and soon discovered by children buried under the barn. Blay was inspected by local male physicians and accused of concealment.

She was dragged from her temporary home to a prison in Portsmouth. Her siblings came and testified on her behalf, but whatever they said in defense is lost. The entirely male jury found her guilty. The colonial governor gave her reprieves but eventually she was hanged from a tree in December 1768, like all the women at Salem before her, by a legal system that gave women little choices.

The day after Ruth was hanged, she published her last words in the paper: “The time being now short after returning Thanks to all Friends for the kindness shown me, I must bid them farewell… my Conscience is clear with respect to my poor Infant;-- And though I die with a forgiving Spirit as to all my Enemies, but charge two women in particular to examine their own Hearts, as they will answer to it another day– whether they do not come under the Character of false witnesses?-- And whether Prejudice, Jealousy, or something else has not drove them thus to bear false Witness against me.”

Why did women at Salem tell on each other? Why did white women enslave their Black sisters and steal land from their Indigenous sisters? Why did women testify against each other, like with Ruth? Would things have been different with education, rights, and a voice in public spaces? We can only speculate.

Conclusion:

As the colonial era came to a close women were divided by region, race, class, and loyalties. There seemed to be no end to the slave trade in sight, and the status of women in the colonies was increasingly restrictive. Women, who had been important economic contributors in the settling of the English colonies, were now more likely to be referred to as emotional supporters to family life.

The French and Indian War, or the Seven Years war resulted in taxes imposed on the colonists which directly hit every colonial home. Enslaved and Indigenous peoples were left wondering about which side will support their freedom and land claims.

By the end of this era, so much remained in question. What role would women play in the Revolution? How would class, race, and condition of servitude impact their loyalties? Would women’s status, rights, and laws improve as a result of the Revolution?

As the colonial era came to a close women were divided by region, race, class, and loyalties. There seemed to be no end to the slave trade in sight, and the status of women in the colonies was increasingly restrictive. Women, who had been important economic contributors in the settling of the English colonies, were now more likely to be referred to as emotional supporters to family life.

The French and Indian War, or the Seven Years war resulted in taxes imposed on the colonists which directly hit every colonial home. Enslaved and Indigenous peoples were left wondering about which side will support their freedom and land claims.

By the end of this era, so much remained in question. What role would women play in the Revolution? How would class, race, and condition of servitude impact their loyalties? Would women’s status, rights, and laws improve as a result of the Revolution?

Draw your own conclusions

|

Learn how to teach with inquiry.

Many of these lesson plans were sponsored in part by the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources Eastern Region Program, coordinated by Waynesburg University, the History and Social Studies Education Faculty at Plymouth State University, and the Patrons of the Remedial Herstory Project. |

Lesson Plans from Other Organizations

- The National Women's History Museum has lesson plans on women's history.

- The Gilder Lehrman Institute for American History has lesson plans on women's history.

- The NY Historical Society has articles and classroom activities for teaching women's history.

- Unladylike 2020, in partnership with PBS, has primary sources to explore with students and outstanding videos on women from the Progressive era.

- The Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media has produced recommendations for teaching women's history with primary sources and provided a collection of sources for world history. Check them out!

- The Stanford History Education Group has a number of lesson plans about women in US History.

Period Specific Lesson Plans from Other Organizations

- First Encounters:

- Gilder Lehrman: The conclusion that encounters between European settlers and Native Americans changed the lives of both groups has been central to many historical accounts of colonial history. While the arguments made are convincing, the discussions do not directly address the lives of women. It is possible that this omission is a result of a paucity of sources. Regardless of the problems with sources, the question may still be asked: Does this assumption hold up when we look at the encounter of women of both cultures? If not, why not? Before we can consider questions such as these, we need to look at the available primary sources for seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century women and gather as much useful information as we can. Because there is not a wealth of primary sources available on the Internet on these women, we need to read what we do have carefully and learn as much as we can. Hopefully, this will enable us to analyze and write this history. In this lesson, students will use primary and secondary sources to research and understand the lives of women (both Native American and European) in North America in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

- NY Historical Society: Women were an integral part of the daily life and success of New Netherland. They served as translators between the Dutch government and the local Native tribes, and acted as liaisons during negotiations with enemy forces. Women were at the center of the colony’s struggle to define the terms of slavery and freedom for the black colonials who lived in the territory. Dutch women actively participated in the bustling trade in the colony, while Native women manipulated imperial power structures to ensure their own survival. And all women in New Netherland contributed to the survival of the colony while still carrying out the responsibilities of home and child care.

- NY Historical Society: The traditional role of women in English society was one of subordination or second-class status. Women were expected to answer to their fathers, their husbands, and their religious and political leaders. The English common law practice of coverture made it so married women did not legally or economically exist, so they could not be free. But women were hard at work affecting the colonies in many ways, from enslaved women bringing agricultural knowledge that made colonies flourish to housewives inventing new ways to perform basic tasks. Women took part in the armed resistance to European invasion, and challenged the gender norms they were forced to live under. The power of women was well recognized by English colonial governments, who made laws to govern their reproduction, tried them for heresy and witchcraft, and severely punished their crimes, even when the women themselves were not at fault. The very first published poet of the English colonies was a woman. Even though the odds were against them, the women of the early English colonies were important to the development of the New World.

- NY Historical Society: King Philip’s War proved disastrous for Weetamoo and her people. After a strong start, vicious English counterattacks wore away at the tribal alliance. Wampanoag society was destroyed. At least 750 Wampanoag were killed during the war, and all the Wampanoag who were captured were sold into slavery. Weetamoo drowned while crossing a river on her way to battle. Her body was found by English soldiers on August 3, 1676. She was so feared that the soldiers mounted her head on a pole outside an English settlement as proof that she had been defeated. The sight of her head sent captive Native warriors into a frenzy of grief, proof of the love she inspired in her people. Her endeavors may have failed, but her life story stands as a testament to the ways women in Native communities fought back against the aggression of European settlers.

- Stanford History Education Group: Examining Passenger Lists: What can passenger lists from ships arriving in North American colonies tell us about those who immigrated? And what can those characteristics tell us about life in the colonies themselves? In this lesson, students critically examine the passenger lists of ships headed to New England and Virginia to better understand English colonial life in the 1630s.

- Stanford History Education Group: Pocahontas: Thanks to the Disney film, most students know the legend of Pocahontas. But is the story told in the 1995 movie accurate? In this lesson, students use evidence to explore whether Pocahontas actually saved John Smith’s life and practice the ability to source, corroborate, and contextualize historical documents.