23. 1600-1850 Cloistered Women in AsiA

|

During the West's period of rapid growth and expansion, Asian empires continued to thrive, but pressures to modernize and westernize affected women's lives everywhere. In China and India, the powerful empires provided stability before the gradual decline and intrusion from British imperialism. Japan saw major changes to women's lives and status as it underwent the Meiji Restoration. In the Ottoman Empire, women saw elevated status that shifted and changed. Wahhabism also transformed the lives of Muslim women wherever it took root.

|

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

Women across Asia saw their lives changing and shifting as the world modernized. Pressures to westernize both helped and hurt their status for various reasons. But women, wherever they were, served their communities and made history. Despite the influx of modernization efforts, the influence of Buddhism, Confucianism, Shintoism, and Islam, continued to play prominent roles in women's lives and societal expectations. Women increasingly were encouraged to serve the community beyond the cloistered sphere, which influenced freedoms as well as a backlash of restrictions. What was it like for cloistered women in Asia? It depends.

China

In 1644, the Chinese were conquered by the Qing, or Manchu, dynasty from Manchuria. Qing rulers had mixed feelings about Chinese customs. On the one hand, they worked to re-integrate Confucian teachings in which gender roles were devastating for women, but they also believed themselves superior, forbade intermarriage between the Manchu and the Chinese, and had segregated schools.

The Manchu attempted to rid the Chinese of many practices. For example, women were forbidden from foot binding, a painful Chinese practice left over from the Song dynasty. But so much of Confucian thinking about women was ingrained. Women were always referred to by their association with men: wife of __, or mother of __. Her strengths and social status was determined by her role as a mother or wife. Bearing children was essential.

In the Qing period, women, especially widows, were praised for not remarrying after the death of their husbands. Biographers recorded the lives of women deemed morally exceptional. Widows loyalty was recorded in stories, but not the names of the women. The family received awards from the Qing government and an arch was erected memorializing her. At the height of the Qing dynasty, 1644-1736, almost 7,000 women received these honors.

The Qing era was a period of expansion for the Chinese, leading to an influx of people from conquered territories into the Chinese population. Conquests transformed Central Asia, a cosmopolitan center along the silk roads, now a hotbed for conflict between the nomadic pastoralists and infiltrating agricultural society.

Despite these changes and increasing diversity within the empire, Qing women saw little improvement to their daily lives, which were highly restricted and revolved around the domestic sphere and rearing strong sons. Women were often one of several wives or lived as a concubine. The Qing campaigned to promote the ideal of a virtuous woman.

Men who had many wives valued the chastity and virginity of women. Literature of the period demonstrates just how important this was. Poems and songs highly valued female purity. They included stories of women who were so loyal to their virtue that they committed suicide to avoid rape or chose not to remarry when their spouse died. None of these stories actually named these women– so they were likely representative of the ideal woman, rather than any real woman. When the Qing government sought examples of “chaste widows,” families of the period nominated over 6,000 different women who were honored with a stone arch.

Poet Wanyan Yun Zhu was an elite Chinese woman who married into the Manchu and was famous for supporting other women. She was a patron of women’s literature and compiled poems written by other women. She also compiled biographies of important and moral Chinese women who lived exciting lives full of murder, sacrifice, and travels to exotic lands. The women she chose to include tell us a great deal about the pressure of chastity in her time. She selected faithful wives, submissive daughters, and other examples of "ideal” Chinese women.

The Qing dynasty declined slowly beginning in the late 1700s and culminating with British and other foreign imperialism in the late 1800s. Social uprisings against the Qing began with the White Lotus uprising in 1796–1820. With this decline, came major changes in women's lives and status.

China

In 1644, the Chinese were conquered by the Qing, or Manchu, dynasty from Manchuria. Qing rulers had mixed feelings about Chinese customs. On the one hand, they worked to re-integrate Confucian teachings in which gender roles were devastating for women, but they also believed themselves superior, forbade intermarriage between the Manchu and the Chinese, and had segregated schools.

The Manchu attempted to rid the Chinese of many practices. For example, women were forbidden from foot binding, a painful Chinese practice left over from the Song dynasty. But so much of Confucian thinking about women was ingrained. Women were always referred to by their association with men: wife of __, or mother of __. Her strengths and social status was determined by her role as a mother or wife. Bearing children was essential.

In the Qing period, women, especially widows, were praised for not remarrying after the death of their husbands. Biographers recorded the lives of women deemed morally exceptional. Widows loyalty was recorded in stories, but not the names of the women. The family received awards from the Qing government and an arch was erected memorializing her. At the height of the Qing dynasty, 1644-1736, almost 7,000 women received these honors.

The Qing era was a period of expansion for the Chinese, leading to an influx of people from conquered territories into the Chinese population. Conquests transformed Central Asia, a cosmopolitan center along the silk roads, now a hotbed for conflict between the nomadic pastoralists and infiltrating agricultural society.

Despite these changes and increasing diversity within the empire, Qing women saw little improvement to their daily lives, which were highly restricted and revolved around the domestic sphere and rearing strong sons. Women were often one of several wives or lived as a concubine. The Qing campaigned to promote the ideal of a virtuous woman.

Men who had many wives valued the chastity and virginity of women. Literature of the period demonstrates just how important this was. Poems and songs highly valued female purity. They included stories of women who were so loyal to their virtue that they committed suicide to avoid rape or chose not to remarry when their spouse died. None of these stories actually named these women– so they were likely representative of the ideal woman, rather than any real woman. When the Qing government sought examples of “chaste widows,” families of the period nominated over 6,000 different women who were honored with a stone arch.

Poet Wanyan Yun Zhu was an elite Chinese woman who married into the Manchu and was famous for supporting other women. She was a patron of women’s literature and compiled poems written by other women. She also compiled biographies of important and moral Chinese women who lived exciting lives full of murder, sacrifice, and travels to exotic lands. The women she chose to include tell us a great deal about the pressure of chastity in her time. She selected faithful wives, submissive daughters, and other examples of "ideal” Chinese women.

The Qing dynasty declined slowly beginning in the late 1700s and culminating with British and other foreign imperialism in the late 1800s. Social uprisings against the Qing began with the White Lotus uprising in 1796–1820. With this decline, came major changes in women's lives and status.

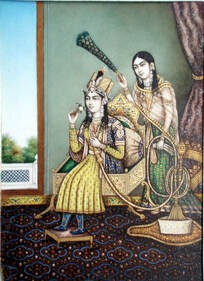

Nur Jahan, Wikimedia Commons

Nur Jahan, Wikimedia Commons

Mughals

Further south, India’s Mughal empire fostered a new phase of interaction between the Islamic and Hindu cultures in South Asia. The Mughal leadership were Muslims, along with just 20% of the population, while the rest formed a Hindu majority. Akbar, who ruled from 15 56–1605, recognized that he needed to accommodate the Hindu majority. When he conquered north western India, he married several princesses but did not force them to convert to Islam. He also supported the building of Hindu temples and made reforms to some Hindu restrictions on women that proved helpful to women’s status, including encouraging the remarriage of

widows which was forbidden in many Hindu communities. He also discouraged child marriages. He persuaded merchants to set aside certain days for women to go to the market in relative seclusion. Akbar’s reforms were deemed too tolerant by some Muslim elite who wanted Hinduism eradicated. The philosopher Shaykh Ahmad Sirhindi was one of Akbar's most vocal opponents. He blamed women from Sufi Islam and Hinduism for Akbar‘s deviation from the righteous path. He said, “because of their utter stupidity women pray to stones and idols and ask for their help. This practice is common, especially when smallpox strikes, and there’s hardly a woman who is not involved in this polytheistic practice.”

When times demanded it, women did wield enormous power in Mughal society. For example, Nur Jahan was the favorite wife of Akbar’s successor, Emperor Jahangir, a raging drunk and opium addict. She became the power behind his throne meeting with dignitaries, consulting with ministers, and having coins issued in her name. She was Persian, and she encouraged her family and poets, artists, scholars, and officers from her home region to bask in the luxury at her court in India. But she was accused of too much spending and corruption, and the large number of foreign Persians didn't help. Jahangir exercised mass conversions to Islam and persecuted the Jains.

In 1627, Shah Jahan, Jehangir's son by his second legitimate wife, Malika Jahan, became emperor of perhaps the greatest empire in the world at the time. Shah Jahan married many women, but his favorite was Nur Jahan's niece, Mumtaz Mahal whom he gave the title "Mumtaz Mahal" or the exalted one of the palace. She gave birth to fourteen children and died in her final childbirth. Shah Jahan had the Taj Mahal built as a tomb for her: considered to be a monument of undying love.

Further south, India’s Mughal empire fostered a new phase of interaction between the Islamic and Hindu cultures in South Asia. The Mughal leadership were Muslims, along with just 20% of the population, while the rest formed a Hindu majority. Akbar, who ruled from 15 56–1605, recognized that he needed to accommodate the Hindu majority. When he conquered north western India, he married several princesses but did not force them to convert to Islam. He also supported the building of Hindu temples and made reforms to some Hindu restrictions on women that proved helpful to women’s status, including encouraging the remarriage of

widows which was forbidden in many Hindu communities. He also discouraged child marriages. He persuaded merchants to set aside certain days for women to go to the market in relative seclusion. Akbar’s reforms were deemed too tolerant by some Muslim elite who wanted Hinduism eradicated. The philosopher Shaykh Ahmad Sirhindi was one of Akbar's most vocal opponents. He blamed women from Sufi Islam and Hinduism for Akbar‘s deviation from the righteous path. He said, “because of their utter stupidity women pray to stones and idols and ask for their help. This practice is common, especially when smallpox strikes, and there’s hardly a woman who is not involved in this polytheistic practice.”

When times demanded it, women did wield enormous power in Mughal society. For example, Nur Jahan was the favorite wife of Akbar’s successor, Emperor Jahangir, a raging drunk and opium addict. She became the power behind his throne meeting with dignitaries, consulting with ministers, and having coins issued in her name. She was Persian, and she encouraged her family and poets, artists, scholars, and officers from her home region to bask in the luxury at her court in India. But she was accused of too much spending and corruption, and the large number of foreign Persians didn't help. Jahangir exercised mass conversions to Islam and persecuted the Jains.

In 1627, Shah Jahan, Jehangir's son by his second legitimate wife, Malika Jahan, became emperor of perhaps the greatest empire in the world at the time. Shah Jahan married many women, but his favorite was Nur Jahan's niece, Mumtaz Mahal whom he gave the title "Mumtaz Mahal" or the exalted one of the palace. She gave birth to fourteen children and died in her final childbirth. Shah Jahan had the Taj Mahal built as a tomb for her: considered to be a monument of undying love.

Anti-Hindu thinking found a champion in Shah Jahan's successor, the Emperor Aurangzeb. He was less tolerant in his approach to establishing Islamic supremacy. Where Akbar had discouraged Hindu practices, Aurangzeb forbade them.. Music and dance were banned at court; common vices like gambling, drinking, and prostitution were suppressed. Dancing girls were ordered to get married, and the custom of widows burning themselves on their husband’s funeral pyre was outlawed. The fracturing religious tensions in the empire opened the way for the British takeover a century and a half later.

In Southeast Asia, Muslim women continued to hold significant political power. In Sumatra, many women ruled in the late 17 century, resulting in the male patriarchy banning women from exercising any political power. In Java, elite Muslim women served political roles in royal courts. And in Indonesia, women made substantial contributions to the economy as laborers, consumers, and shopkeepers–beyond their domestic responsibilities.

In Southeast Asia, Muslim women continued to hold significant political power. In Sumatra, many women ruled in the late 17 century, resulting in the male patriarchy banning women from exercising any political power. In Java, elite Muslim women served political roles in royal courts. And in Indonesia, women made substantial contributions to the economy as laborers, consumers, and shopkeepers–beyond their domestic responsibilities.

Meiji Restoration

Off the coast in Japan, rapid change affected the lives of women. The Shogunate that had brought centuries of peace (see Feudalism in Japan) ended in Civil War, out of which rose the Meiji Restoration. This 1868 political revolution that returned power to the Emperor Mutsuhito, the emperor Meiji. This move away from a military state ruled by warlords to an imperial nation, led to industrialization, modernization, westernization, and eventually imperialism at the end of the 1800s. For women, these changes would be monumental.

The reforms brought about by the Meiji included laws that created a degree of social equality. They included land redistribution, class restructuring, and a trend toward democracy. Women's roles, rights, and responsibilities were part of this social upheaval. Traditional Japanese society had a mix of Confucian, Shintoism, and Buddhist ideals for women. The push for modernity and thus "modern women," simultaneously challenged the idealized female role and created a nostalgia for it. "Good wives, and wise mothers” were supported by the imperial government to hold together the fabric of a rapidly changing society.

Women and girls were recruited to work in new government factories to produce industrial goods like silk. Women reported that they were grateful for these jobs and felt they earned more than they could have elsewhere. The liberalizing of roles allowed women freedoms they hadn't previously had. The "moga" was a sexually liberated, urban woman who spent her money and consumed products of her choosing. As this period, known as the Taishō period, ended in 1925, the government passed universal male suffrage and excluded women from the vote-- to their dismay.

Off the coast in Japan, rapid change affected the lives of women. The Shogunate that had brought centuries of peace (see Feudalism in Japan) ended in Civil War, out of which rose the Meiji Restoration. This 1868 political revolution that returned power to the Emperor Mutsuhito, the emperor Meiji. This move away from a military state ruled by warlords to an imperial nation, led to industrialization, modernization, westernization, and eventually imperialism at the end of the 1800s. For women, these changes would be monumental.

The reforms brought about by the Meiji included laws that created a degree of social equality. They included land redistribution, class restructuring, and a trend toward democracy. Women's roles, rights, and responsibilities were part of this social upheaval. Traditional Japanese society had a mix of Confucian, Shintoism, and Buddhist ideals for women. The push for modernity and thus "modern women," simultaneously challenged the idealized female role and created a nostalgia for it. "Good wives, and wise mothers” were supported by the imperial government to hold together the fabric of a rapidly changing society.

Women and girls were recruited to work in new government factories to produce industrial goods like silk. Women reported that they were grateful for these jobs and felt they earned more than they could have elsewhere. The liberalizing of roles allowed women freedoms they hadn't previously had. The "moga" was a sexually liberated, urban woman who spent her money and consumed products of her choosing. As this period, known as the Taishō period, ended in 1925, the government passed universal male suffrage and excluded women from the vote-- to their dismay.

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

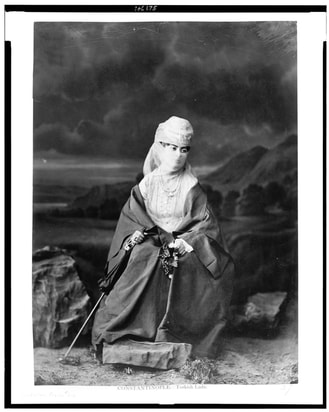

Ottomans

To the west, the Ottoman Empire controlled most of the modern Middle East. By the 1600s, the Empire began to lose its economic and military dominance over Europe. Europe had strengthened rapidly with the Renaissance era reforms. This growth would continue with the Enlightenment and Industrial Revolutions into the 1700s and 1800s. One of the most enduring images of Ottoman women's segregation is the harem, a place where the wives and daughters of royal men led segregated lives. The exotic and eroticized image of the harem is a Western obsession that overlooks the much more complex functioning of this important institution.

A major contrast between European and Ottoman women was harem life. Ottoman harems were much different from Chinese harems, and both were eroticized in the Western imagination. In Ottoman society, the harem served to exclude women, but also to grant them freedom of expression..

Lady Montagu

One remarkable woman who bridged the gap between East and West was Lady Mary Wortley Montagu. Lady Montagu was an English aristocrat, writer, and poet. Today, she is remembered for her letters, particularly her Turkish Embassy Letters, describing her travels to the Ottoman Empire in the early 1700s as wife to the British ambassador to Turkey. These have been described as "the very first example of a secular work by a woman about the Muslim Orient." Aside from her writing, Lady Montagu is also known for introducing and bringing smallpox inoculation to Britain on her return from Turkey. She is also notable for her travels, her scandalous love life, and her progressive views on women’s education, slavery, and Islam. Montagu shared with other philosophers a celebration of Islam for its rational approach to theology, its strict monotheism, and its teaching and practice of religious tolerance. In short, Montagu and other thinkers in this tradition saw Islam as a source of Enlightenment, as evidenced in her calling the Qur'an "the purest morality delivered in the very best language." Montagu dedicated large portions of the Turkish Embassy Letters to criticizing Catholic religious practices, sainthood, miracles, and religious relics, which she frequently denounced. At a time when many Western Christians viewed Islam as the enemy and its followers as barbarians, her understanding of the religion was astounding and nuanced.

During Montagu's time in the Ottoman Empire, she also saw and wrote extensively on the practice of slavery and the treatment of slaves by the Turks. She wrote frequently and positively about the various enslaved people whom she saw in the elite circles of Istanbul, including eunuchs and large collections of serving and dancing girls dressed in expensive outfits. In one of her letters from the interior of a bath house, she dismissed the idea that slaves of the Ottoman elite were figures to be pitied. In response to her visit to the slave market in Istanbul, she wrote "you will imagine me half a Turk when I don't speak of it with the same horror other Christians have done before me, but I cannot forbear applauding the humanity of the Turks to those creatures. They are never ill-used, and their slavery is in my opinion no worse than servitude all over the world." This again strongly contrasted with the reports of other travelers at the time that presented the Muslims as barbaric savages.

During her time in the Empire, Montagu was charmed by the beauty, style, and hospitality of the Ottoman women she encountered. Montagu constantly praised the "warmth and civility" of Ottoman women. She described the "hammam," a Turkish bath, "as a space of urbane homosociality, free of cruel satire and disdain,” and said that "hammam are remarkable for their undisguised admiration of the women's beauty and demeanor." She wrote about an amusing event in which Turkish women were horrified by the sight of the corset she was wearing. She said, "they believed I was so locked up in that machine that it was not in my own power to open it, which contrivance they attributed to my husband." This reflects the varied experiences of women's freedom around the world.

Montagu wrote about the misconceptions that previous travelers, specifically male travelers, had recorded about the religion, traditions and the treatment of women in the Ottoman Empire. Her gender and class status provided her access to female spaces that were closed off to European men and allowed her to give a more accurate account of experiences and freedoms of Turkish women. She published her letters under the title, "Sources that Have Been Inaccessible to Other Travelers." The letters draw attention to the descriptions provided by previous (male) travelers. She writes, "You will perhaps be surpriz'd at an account so different from what you have been entertained with by the common Voyage-writers who are very fond of speaking of what they don't know." In general, Montagu dismissed the quality of European travel literature of the 1700s century as nothing more than "trite observations…superficial…[of] boys [who] only remember where they met with the best wine or the prettiest women."

A pioneering scientist, feminist, explorer, religious scholar, writer, and potential queer icon, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu deserves the same fame as Dr. Jenner, who so often is credited with protecting Britain from smallpox!

To the west, the Ottoman Empire controlled most of the modern Middle East. By the 1600s, the Empire began to lose its economic and military dominance over Europe. Europe had strengthened rapidly with the Renaissance era reforms. This growth would continue with the Enlightenment and Industrial Revolutions into the 1700s and 1800s. One of the most enduring images of Ottoman women's segregation is the harem, a place where the wives and daughters of royal men led segregated lives. The exotic and eroticized image of the harem is a Western obsession that overlooks the much more complex functioning of this important institution.

A major contrast between European and Ottoman women was harem life. Ottoman harems were much different from Chinese harems, and both were eroticized in the Western imagination. In Ottoman society, the harem served to exclude women, but also to grant them freedom of expression..

Lady Montagu

One remarkable woman who bridged the gap between East and West was Lady Mary Wortley Montagu. Lady Montagu was an English aristocrat, writer, and poet. Today, she is remembered for her letters, particularly her Turkish Embassy Letters, describing her travels to the Ottoman Empire in the early 1700s as wife to the British ambassador to Turkey. These have been described as "the very first example of a secular work by a woman about the Muslim Orient." Aside from her writing, Lady Montagu is also known for introducing and bringing smallpox inoculation to Britain on her return from Turkey. She is also notable for her travels, her scandalous love life, and her progressive views on women’s education, slavery, and Islam. Montagu shared with other philosophers a celebration of Islam for its rational approach to theology, its strict monotheism, and its teaching and practice of religious tolerance. In short, Montagu and other thinkers in this tradition saw Islam as a source of Enlightenment, as evidenced in her calling the Qur'an "the purest morality delivered in the very best language." Montagu dedicated large portions of the Turkish Embassy Letters to criticizing Catholic religious practices, sainthood, miracles, and religious relics, which she frequently denounced. At a time when many Western Christians viewed Islam as the enemy and its followers as barbarians, her understanding of the religion was astounding and nuanced.

During Montagu's time in the Ottoman Empire, she also saw and wrote extensively on the practice of slavery and the treatment of slaves by the Turks. She wrote frequently and positively about the various enslaved people whom she saw in the elite circles of Istanbul, including eunuchs and large collections of serving and dancing girls dressed in expensive outfits. In one of her letters from the interior of a bath house, she dismissed the idea that slaves of the Ottoman elite were figures to be pitied. In response to her visit to the slave market in Istanbul, she wrote "you will imagine me half a Turk when I don't speak of it with the same horror other Christians have done before me, but I cannot forbear applauding the humanity of the Turks to those creatures. They are never ill-used, and their slavery is in my opinion no worse than servitude all over the world." This again strongly contrasted with the reports of other travelers at the time that presented the Muslims as barbaric savages.

During her time in the Empire, Montagu was charmed by the beauty, style, and hospitality of the Ottoman women she encountered. Montagu constantly praised the "warmth and civility" of Ottoman women. She described the "hammam," a Turkish bath, "as a space of urbane homosociality, free of cruel satire and disdain,” and said that "hammam are remarkable for their undisguised admiration of the women's beauty and demeanor." She wrote about an amusing event in which Turkish women were horrified by the sight of the corset she was wearing. She said, "they believed I was so locked up in that machine that it was not in my own power to open it, which contrivance they attributed to my husband." This reflects the varied experiences of women's freedom around the world.

Montagu wrote about the misconceptions that previous travelers, specifically male travelers, had recorded about the religion, traditions and the treatment of women in the Ottoman Empire. Her gender and class status provided her access to female spaces that were closed off to European men and allowed her to give a more accurate account of experiences and freedoms of Turkish women. She published her letters under the title, "Sources that Have Been Inaccessible to Other Travelers." The letters draw attention to the descriptions provided by previous (male) travelers. She writes, "You will perhaps be surpriz'd at an account so different from what you have been entertained with by the common Voyage-writers who are very fond of speaking of what they don't know." In general, Montagu dismissed the quality of European travel literature of the 1700s century as nothing more than "trite observations…superficial…[of] boys [who] only remember where they met with the best wine or the prettiest women."

A pioneering scientist, feminist, explorer, religious scholar, writer, and potential queer icon, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu deserves the same fame as Dr. Jenner, who so often is credited with protecting Britain from smallpox!

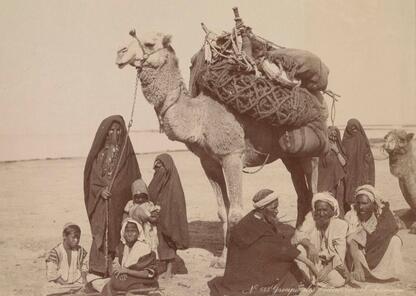

Ottoman Laborers, Cambridge University

Ottoman Laborers, Cambridge University

Ottoman Reforms

Much changed for Ottoman women in the century after Lady Montagu traveled there. Muslim reformers sought to restrict women’s religious gatherings. Turkish women kept some of the social power they had enjoyed in their pastoral societies, but they remained uncounted, and unconsidered in imperial censuses. Elite Turkish women were increasingly veiled. Veiling is regarded as an oppressive practice used to hide female bodies and show male ownership of them. For many women, the veil provided the freedom to be themselves, display their devotion, and be measured by their intellect and not their faces.

There was no doubt the empire was changing as it expanded. More and more enslaved women from the Caucasus mountains and the Sudan entered into the empire, diversifying the population. By 1839, the empire was becoming more modern with reforms across most systems.

Industrialization led many working class women to work full time jobs in factories, especially in rug production. This was a craft they had long worked on and followed as it modernized. The number of women working in factories doubled between 1880 and 1900.

For example, in 1880, workers in Usak numbered 3,000 women and 500 girls; by 1900 their total had increased to 6,000. In the final years of the century, rug production shifted from home workshops to large factories employing thousands of women, including girls as young as four years of age. Workdays were long, eleven hours for all but the youngest girls. Some women walked to work, others lived in dormitories furnished by the factory. In 1908, mobs of women protested against the move to factory production, as home working fit better with their lives and culture. In addition to rug making, Muslim and non-Muslim Ottoman women worked in the shoe, silk, and cigarette industries. Men and women worked side by side in many factories, even though the textile, rug, and cigarette industries were classified as women's work. The large number of women and girls working in Ottoman factories drove wages down and helped make those industries more competitive with European producers. One European report described women's labor as “cheaper than water,” usually costing less than half that of male workers.

Much changed for Ottoman women in the century after Lady Montagu traveled there. Muslim reformers sought to restrict women’s religious gatherings. Turkish women kept some of the social power they had enjoyed in their pastoral societies, but they remained uncounted, and unconsidered in imperial censuses. Elite Turkish women were increasingly veiled. Veiling is regarded as an oppressive practice used to hide female bodies and show male ownership of them. For many women, the veil provided the freedom to be themselves, display their devotion, and be measured by their intellect and not their faces.

There was no doubt the empire was changing as it expanded. More and more enslaved women from the Caucasus mountains and the Sudan entered into the empire, diversifying the population. By 1839, the empire was becoming more modern with reforms across most systems.

Industrialization led many working class women to work full time jobs in factories, especially in rug production. This was a craft they had long worked on and followed as it modernized. The number of women working in factories doubled between 1880 and 1900.

For example, in 1880, workers in Usak numbered 3,000 women and 500 girls; by 1900 their total had increased to 6,000. In the final years of the century, rug production shifted from home workshops to large factories employing thousands of women, including girls as young as four years of age. Workdays were long, eleven hours for all but the youngest girls. Some women walked to work, others lived in dormitories furnished by the factory. In 1908, mobs of women protested against the move to factory production, as home working fit better with their lives and culture. In addition to rug making, Muslim and non-Muslim Ottoman women worked in the shoe, silk, and cigarette industries. Men and women worked side by side in many factories, even though the textile, rug, and cigarette industries were classified as women's work. The large number of women and girls working in Ottoman factories drove wages down and helped make those industries more competitive with European producers. One European report described women's labor as “cheaper than water,” usually costing less than half that of male workers.

Ottoman Women, Wikimedia Commons

Ottoman Women, Wikimedia Commons

Reforms, known as Tanzimat, created educational opportunities for girls in state-run schools in the mid-1800s. In 1869, a decree required BOTH boys and girls to go to grade school. This new law required more teachers. In 1870, the Ottomans opened the Teacher Training College for Girls. Missionary schools also provided women with an education. New magazines and journals for women emerged as women became more literate. As in the west, these magazines focused on women's issues, family life, religion, "acceptable" women's work .

Feminism followed education. In 1876, the first Ottoman Women's Organization was founded to help wounded soldiers. Minority Ottoman women organized to influence reform. Ottoman women could sense some internal shifts happening.

In the late 1800s, scholars and government officials debated the status of women in Ottoman society. They were critical of traditional Ottoman practices and began to shift toward “Western,” practices. They asserted that the “new” woman would help the nation succeed in the modern world. The “traditional” woman, in contrast, was trapped in the antiquated traditions of the past and progress. One of the common tropes of the early 1900s was the image of an old hag, who symbolized traditional culture, contrasted with a young Westernized woman of the future. This vision of womanhood was championed by the political group called the Young Turks. The Young Turks stated, “Women must be liberated from the shackles of tradition.” Women's status in the cities improved a bit, and women began to participate in public social activities, education improved, and women earned positions in professional roles like lawyers and doctors. Public spaces like restaurants were segregated to allow women to participate. In 1917, marriage laws changed to become more secular, rather than religious. But in rural parts of the empire, traditional values prevailed. During World War I, the government created the Society for the Employment of Muslim Women to address the wartime labor shortages and encourage women to work in the Battalions of Women Workers. In six months 14,000 women in Istanbul had applied for employment through the society. This brought women of all classes into the workforce previously dominated by men. The Ottoman Empire collapsed after WWI and the ensuing Turkish War for Independence (1919-1923). Women like Halide Edib Adivar and Nakiye Elgun played a public role in the war.

Feminism followed education. In 1876, the first Ottoman Women's Organization was founded to help wounded soldiers. Minority Ottoman women organized to influence reform. Ottoman women could sense some internal shifts happening.

In the late 1800s, scholars and government officials debated the status of women in Ottoman society. They were critical of traditional Ottoman practices and began to shift toward “Western,” practices. They asserted that the “new” woman would help the nation succeed in the modern world. The “traditional” woman, in contrast, was trapped in the antiquated traditions of the past and progress. One of the common tropes of the early 1900s was the image of an old hag, who symbolized traditional culture, contrasted with a young Westernized woman of the future. This vision of womanhood was championed by the political group called the Young Turks. The Young Turks stated, “Women must be liberated from the shackles of tradition.” Women's status in the cities improved a bit, and women began to participate in public social activities, education improved, and women earned positions in professional roles like lawyers and doctors. Public spaces like restaurants were segregated to allow women to participate. In 1917, marriage laws changed to become more secular, rather than religious. But in rural parts of the empire, traditional values prevailed. During World War I, the government created the Society for the Employment of Muslim Women to address the wartime labor shortages and encourage women to work in the Battalions of Women Workers. In six months 14,000 women in Istanbul had applied for employment through the society. This brought women of all classes into the workforce previously dominated by men. The Ottoman Empire collapsed after WWI and the ensuing Turkish War for Independence (1919-1923). Women like Halide Edib Adivar and Nakiye Elgun played a public role in the war.

Wahhabism

Further south on the Arabian peninsula, reaction to modernization was brewing. In the early 1700s, an Islamic scholar, Muhammad Ibn Abd Abdullah al-Wahab, worked to address the weakening Ottoman empire through a return to what he saw as traditional Islamic thinking, the way women had been treated under Muhammad. He preferred Aisha’s contributions to the Hadith and for women’s agency. He believed women were spiritually equal to men and made no exceptions to the five daily prayers during menstruation, generally considered a positive because others considered menstruating women filthy. But the effect of Wahhabism varied significantly from his ideas. Wahhabism spread from the Saudi Arabian peninsula throughout the Islamic world, through Southeast and South Asia, the Middle East, and Africa.

The Wahhabi movement found political headway when it was backed by a Saudi Arabian ruler. The result was the destruction of idols, the burning of books, the banning of vices, and the banning of “non-authorized“ texts. This climate was dangerous for women. Wahhabism emphasized the rights of women within the patriarchal framework. He also returned to traditional Islam, where women had the right to consent to their marriages and power over their finances and divorce.

One particularly problematic trait of Wahhabism was its return to “traditional” Islam for forcible control of women’s sexuality and ancient tribal punishments of sexually promiscuous women. “Promiscuity” could be anything from having a child out of wedlock, to adultery, to prostitution .Women would be dragged by their male relations before all male judges and juries, using only male witnesses to defend their actions. Women convicted would be subjected to a horrendous punishment such as being buried up to their necks in dirt and then having stones hurled at their head until they died by the hands of those relatives closest to them.

Wahhabism still thrives in parts, but not all, of the Islamic world today, but to understand it would take a much deeper exploration than offered here. It's important to note that all of these ideas about Wahhabism are controversial among Muslims.

Conclusion

In Asia, women saw bold change driven by a desire to modernize as in Japan and the Ottoman Empire, stagnation that bred opportunities for imperialism as in the Mughal empire, and calls for a return to tradition as in Arabia, Everywhere, women's lives both changed and remained the same. Grounded in traditions present for centuries, if not millennia, women labored as they always had. The demands of the modern world, industry, and massive world wars put cracks into traditional expectations for women.

By the end of this era, so much remained in question. What changes did these empires endure and how did they impact the everyday lives of women - good and bad? What new freedoms did they allow women? How did the different ways women were treated influence the international relations between the diverging industrialized world?

Further south on the Arabian peninsula, reaction to modernization was brewing. In the early 1700s, an Islamic scholar, Muhammad Ibn Abd Abdullah al-Wahab, worked to address the weakening Ottoman empire through a return to what he saw as traditional Islamic thinking, the way women had been treated under Muhammad. He preferred Aisha’s contributions to the Hadith and for women’s agency. He believed women were spiritually equal to men and made no exceptions to the five daily prayers during menstruation, generally considered a positive because others considered menstruating women filthy. But the effect of Wahhabism varied significantly from his ideas. Wahhabism spread from the Saudi Arabian peninsula throughout the Islamic world, through Southeast and South Asia, the Middle East, and Africa.

The Wahhabi movement found political headway when it was backed by a Saudi Arabian ruler. The result was the destruction of idols, the burning of books, the banning of vices, and the banning of “non-authorized“ texts. This climate was dangerous for women. Wahhabism emphasized the rights of women within the patriarchal framework. He also returned to traditional Islam, where women had the right to consent to their marriages and power over their finances and divorce.

One particularly problematic trait of Wahhabism was its return to “traditional” Islam for forcible control of women’s sexuality and ancient tribal punishments of sexually promiscuous women. “Promiscuity” could be anything from having a child out of wedlock, to adultery, to prostitution .Women would be dragged by their male relations before all male judges and juries, using only male witnesses to defend their actions. Women convicted would be subjected to a horrendous punishment such as being buried up to their necks in dirt and then having stones hurled at their head until they died by the hands of those relatives closest to them.

Wahhabism still thrives in parts, but not all, of the Islamic world today, but to understand it would take a much deeper exploration than offered here. It's important to note that all of these ideas about Wahhabism are controversial among Muslims.

Conclusion

In Asia, women saw bold change driven by a desire to modernize as in Japan and the Ottoman Empire, stagnation that bred opportunities for imperialism as in the Mughal empire, and calls for a return to tradition as in Arabia, Everywhere, women's lives both changed and remained the same. Grounded in traditions present for centuries, if not millennia, women labored as they always had. The demands of the modern world, industry, and massive world wars put cracks into traditional expectations for women.

By the end of this era, so much remained in question. What changes did these empires endure and how did they impact the everyday lives of women - good and bad? What new freedoms did they allow women? How did the different ways women were treated influence the international relations between the diverging industrialized world?

Draw your own conclusions

|

Learn how to teach with inquiry.

Many of these lesson plans were sponsored in part by the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources Eastern Region Program, coordinated by Waynesburg University, the History and Social Studies Education Faculty at Plymouth State University, and the Patrons of the Remedial Herstory Project. |

Lesson Plans from Other Organizations

- The University of Colorado has a lesson plan on the experiences of women in the Meiji Restoration. It includes primary sources. It includes the following essential questions: What did it mean to be a modern woman in Japan during the Meiji and Taishō Periods? What do modern Japanese women’s experiences tell us about the impact of rapid modernization on Japan and its people? What do modern Japanese women’s experiences tell us about changes in Japanese culture and society, generally, of the early 20th century (circa 1900-1930)?

- A past AP World History exam included a DBQ that compared industrialization in Russia and Japan, centralizing women's experiences in Japanese factories. The DBQ is here.

- This website, Women in World History has primary source based lesson plans on women's history in a whole range of topics. Some are free while others have a cost.

- The Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media has produced recommendations for teaching women's history with primary sources and provided a collection of sources for world history. Check them out!

- The Stanford History Education Group has a number of lesson plans about women in World History.

Mrs. Crane: An Excerpt from a letter to the New York Times about the Empress Cixi

Imperial rulers of China lived inside the Forbidden City, a palace city used by the Emperors of China. The city was “forbidden” to almost all subjects. Beginning during the Ming dynasty, the Forbidden City became the location of the imperial court. The city created a literal wall between the rulers and the lay people, clouding them in mystery and misunderstanding. Nothing in the historical record tells us more about Mrs. Crane, the author of this document, but her position on the empress is clear.

The sense of justice shown by England in her protest against the murderous cruelty of that human vampire, the Dowager of China, should be followed by all civilized and Christian folk [e]ndorsing these lines: ‘Rebellion to tyrants, obedience to God.” The tree of liberty only grows when watered by the blood of tyrants, and who more worthy of death than she who has connived at and urged on the murdering of our dear missionaries?

Mrs. William Halsted Crane, “Career of Chinese Dowager Empress,” New York Times, Aug. 8, 1903, 6.

Questions:

1. Who is the source of this document? Is she Chinese? How well is she likely to know the Empress?

2. What does the tone of this excerpt say about how Empress Cixi was viewed by some foreign sources?

3. Empress Cixi is often described as power hungry and manipulative. Looking further than just her description, how might these descriptives affect her legacy, as well as the perceptions of women in power?

The sense of justice shown by England in her protest against the murderous cruelty of that human vampire, the Dowager of China, should be followed by all civilized and Christian folk [e]ndorsing these lines: ‘Rebellion to tyrants, obedience to God.” The tree of liberty only grows when watered by the blood of tyrants, and who more worthy of death than she who has connived at and urged on the murdering of our dear missionaries?

Mrs. William Halsted Crane, “Career of Chinese Dowager Empress,” New York Times, Aug. 8, 1903, 6.

Questions:

1. Who is the source of this document? Is she Chinese? How well is she likely to know the Empress?

2. What does the tone of this excerpt say about how Empress Cixi was viewed by some foreign sources?

3. Empress Cixi is often described as power hungry and manipulative. Looking further than just her description, how might these descriptives affect her legacy, as well as the perceptions of women in power?

Empress Cixi: Reform Edict of the Qing Imperial Government

In the wake of the Boxer Uprising (1899-1901) and the catastrophic foreign intervention that that movement precipitated, the imperial government reconsidered the need for fundamental reforms. Government reform had already been attempted, and rejected, in 1898 when Kang Youwei (1858-1927) and his colleagues temporarily ran the imperial government, with the support of the Guangxu Emperor (1871-1908, r. 1875-1908), until the Empress Dowager Cixi (1835-1908) ousted them.

Certain principles of morality (changqing) are immutable, whereas methods of governance (zhifa) have always been mutable. The Classic of Changes states that “when a measure has lost effective force, the time has come to change it.” And the Analects states that “the Shang and Zhou dynasties took away and added to the regulations of their predecessors, as can readily be known.” …

We have now received Her Majesty’s decree to devote ourselves fully to China’s revitalization, to suppress vigorously the use of the terms new and old, and to blend together the best of what is Chinese and what is foreign. The root of China’s weakness lies in harmful habits too firmly entrenched, in rules and regulations too minutely drawn, in the overabundance of inept and mediorìcre officials and in the paucity of truly outstanding ones, in petty bureaus who hide behind the written word and in clerks and yamen runners who use the written word as talismans to acquire personal fortunes, in the mountains of correspondence between government offices that have no relationship to reality, and in the seniority system and associated practices that block the way of men of real talent…

The first essential, even more important than devising new systems of governance (zhifa) is to secure men who govern well (zhi ren). Without new systems, the corrupted old system cannot be salvaged; without men of ability, even good systems cannot be made to succeed.

‘Reform Edict of the Qing Imperial Government’. Columbia University Press, 29 January 1901. http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/ps/cup/qing_reform_edict_1901.pdf

Questions:

Certain principles of morality (changqing) are immutable, whereas methods of governance (zhifa) have always been mutable. The Classic of Changes states that “when a measure has lost effective force, the time has come to change it.” And the Analects states that “the Shang and Zhou dynasties took away and added to the regulations of their predecessors, as can readily be known.” …

We have now received Her Majesty’s decree to devote ourselves fully to China’s revitalization, to suppress vigorously the use of the terms new and old, and to blend together the best of what is Chinese and what is foreign. The root of China’s weakness lies in harmful habits too firmly entrenched, in rules and regulations too minutely drawn, in the overabundance of inept and mediorìcre officials and in the paucity of truly outstanding ones, in petty bureaus who hide behind the written word and in clerks and yamen runners who use the written word as talismans to acquire personal fortunes, in the mountains of correspondence between government offices that have no relationship to reality, and in the seniority system and associated practices that block the way of men of real talent…

The first essential, even more important than devising new systems of governance (zhifa) is to secure men who govern well (zhi ren). Without new systems, the corrupted old system cannot be salvaged; without men of ability, even good systems cannot be made to succeed.

‘Reform Edict of the Qing Imperial Government’. Columbia University Press, 29 January 1901. http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/ps/cup/qing_reform_edict_1901.pdf

Questions:

- Who is the author of this document?

- What are the problems outlined in the royal edict?

- In the final paragraph, why do they need to “secure men who govern well”? What does this imply about the real power Cixi has?

- Based on this edict, what kind of ruler was Empress Cixi?

Princess Der Ling: Two Years in the Forbidden City

For two years, Princess Der Ling was the favorite lady-in-waiting to the Empress Dowager Cixi in the imperial palace in Beijing. This book provides a unique and surprisingly intimate portrait of the Dragon Lady, who ruled China for 47 years, and brought the country to the brink of destruction. Der Ling refers to the larger political context on many occasions. But the best parts of the book are the small details. What emerges is an intimate portrait of the life and personality of the Empress Dowager, and a sense of the inner workings of the highly secretive world of the imperial palace.

[A]ccording to the Manchu custom, the daughters of all Manchu officials of the second rank and above, after reaching the age of fourteen years, should go to the Palace, in order that the Emperor may select them for secondary wives if he so desires, and my father had other plans and ambitions for us. It was in this way that the late Empress Dowager was selected by the Emperor Hsien Feng…

"Her Majesty has sent me to meet you," and was very sweet and polite, and had beautiful manners; but was not very pretty. Then we heard a loud voice from the hall saying, "Tell them to come in at once”... Her Majesty stood up when she saw us and shook hands with us. She had a most fascinating smile and was very much surprised that we knew the Court etiquette so well. After she had greeted us, she said to my mother: "Yu tai tai (Lady Yu), you are a wonder the wayyou have brought your daughters up. They speak Chinese just as well as I do, although I know they have been abroad for so many years, and how is it that they have such beautiful manners?" "Their father was always very strict with them," my mother replied… Her Majesty asked all sorts of questions about our Paris gowns and said we must wear them all the time, as she had very little chance to see them at the Court…

When we commenced to eat, Her Majesty ordered the eunuchs to place plates for us and give us silver chopsticks, spoons, etc., and said: "I am sorry you have to eat standing, but I cannot break the law of our great ancestors. Even the Young Empress cannot sit in my presence. I am sure the foreigners must think we are barbarians to treat our Court ladies in this way and I don't wish them to know anything about our customs. You will see how differently I act in their presence, so that they cannot see my true self.”

…”Do you think they, the foreigners, really like me? I don't think so; on the contrary I know they haven't forgotten the Boxer Rising in Kwang Hsu's 26th year. I don't mind owning up that I like our old ways the best, and I don't see any reason why we should adopt the foreign style. Did any of the foreign ladies ever tell you that I am a fierce-looking old woman?" I was very much surprised that she should… ask me such questions during her meal. She looked quite serious and it seemed to me she was quite annoyed. I assured her that no one ever said anything about Her Majesty but nice things. The foreigners told me how nice she was, and how graceful, etc. This seemed to please her, and she smiled and said: "Of course they have to tell you that, just to make you feel happy by saying that your sovereign is perfect, but I know better. I can't worry too much, but I hate to see China in such a poor condition… While she was saying this I noticed her worried expression. I did not know what to say, but tried to comfort her by saying that that time will come, and we are all looking forward to it.

Der Ling. Two Years in the Forbidden City. Project Gutenberg. 1911

Questions:

[A]ccording to the Manchu custom, the daughters of all Manchu officials of the second rank and above, after reaching the age of fourteen years, should go to the Palace, in order that the Emperor may select them for secondary wives if he so desires, and my father had other plans and ambitions for us. It was in this way that the late Empress Dowager was selected by the Emperor Hsien Feng…

"Her Majesty has sent me to meet you," and was very sweet and polite, and had beautiful manners; but was not very pretty. Then we heard a loud voice from the hall saying, "Tell them to come in at once”... Her Majesty stood up when she saw us and shook hands with us. She had a most fascinating smile and was very much surprised that we knew the Court etiquette so well. After she had greeted us, she said to my mother: "Yu tai tai (Lady Yu), you are a wonder the wayyou have brought your daughters up. They speak Chinese just as well as I do, although I know they have been abroad for so many years, and how is it that they have such beautiful manners?" "Their father was always very strict with them," my mother replied… Her Majesty asked all sorts of questions about our Paris gowns and said we must wear them all the time, as she had very little chance to see them at the Court…

When we commenced to eat, Her Majesty ordered the eunuchs to place plates for us and give us silver chopsticks, spoons, etc., and said: "I am sorry you have to eat standing, but I cannot break the law of our great ancestors. Even the Young Empress cannot sit in my presence. I am sure the foreigners must think we are barbarians to treat our Court ladies in this way and I don't wish them to know anything about our customs. You will see how differently I act in their presence, so that they cannot see my true self.”

…”Do you think they, the foreigners, really like me? I don't think so; on the contrary I know they haven't forgotten the Boxer Rising in Kwang Hsu's 26th year. I don't mind owning up that I like our old ways the best, and I don't see any reason why we should adopt the foreign style. Did any of the foreign ladies ever tell you that I am a fierce-looking old woman?" I was very much surprised that she should… ask me such questions during her meal. She looked quite serious and it seemed to me she was quite annoyed. I assured her that no one ever said anything about Her Majesty but nice things. The foreigners told me how nice she was, and how graceful, etc. This seemed to please her, and she smiled and said: "Of course they have to tell you that, just to make you feel happy by saying that your sovereign is perfect, but I know better. I can't worry too much, but I hate to see China in such a poor condition… While she was saying this I noticed her worried expression. I did not know what to say, but tried to comfort her by saying that that time will come, and we are all looking forward to it.

Der Ling. Two Years in the Forbidden City. Project Gutenberg. 1911

Questions:

- Who is the source of this document? Is she Chinese? How well is she likely to know the Empress?

- What does the tone of this excerpt say about how Empress Cixi was viewed by some foreign sources?

- Based on this book, what kind of ruler was Empress Cixi?

Unknown: The Red Lanterns

The following are excerpts from oral histories gathered through Shandong University in Jinan, China. The oral histories were recorded beginning in the 1960s.

Girls who joined the Boxers were called ‘Shining Red Lanterns.’They dressed all in red. In one hand they had a little red lantern and in the other a little red fan. They carried a basket in the crook of their arm. When bullets were shot at them they waved their fans and the bullets were caught in the basket. You couldn’t hit them!... In every village there were girls who studied the Shining Red Lantern. In my village there were eight or ten of them…There was a song then that went: ‘Learn to be a Boxer, study the Red Lantern, Kill all the foreign devils and make the churches burn.’ Miss Han [Han Guniang] was from Long’gu in Zhili [Hebei]...[she] came to Long[gu on the big hemp marketing day…in 1900. She was riding a big horse and a dozen or so followers came with her. They entered Long’gu blowing bugles and many people ran to watch her. Her followers came from all over Long’gu; there were several thousand of them…It was said she was a Shining Red Lantern. She was very skillful; she could fight with spears or a sword. When she rode on a bench, it would turn into a horse; if she rode a rope, it would change into a dragon; if she sat on a mat it would become a cloud and she could ride the cloud and fly away.

Chen, Janet Y, Pei-kai Cheng, Michael Elliot Lestz, and Jonathan D Spence. The Search for Modern China: A Documentary Collection. Third ed. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2014 (184-185).

Questions:

Girls who joined the Boxers were called ‘Shining Red Lanterns.’They dressed all in red. In one hand they had a little red lantern and in the other a little red fan. They carried a basket in the crook of their arm. When bullets were shot at them they waved their fans and the bullets were caught in the basket. You couldn’t hit them!... In every village there were girls who studied the Shining Red Lantern. In my village there were eight or ten of them…There was a song then that went: ‘Learn to be a Boxer, study the Red Lantern, Kill all the foreign devils and make the churches burn.’ Miss Han [Han Guniang] was from Long’gu in Zhili [Hebei]...[she] came to Long[gu on the big hemp marketing day…in 1900. She was riding a big horse and a dozen or so followers came with her. They entered Long’gu blowing bugles and many people ran to watch her. Her followers came from all over Long’gu; there were several thousand of them…It was said she was a Shining Red Lantern. She was very skillful; she could fight with spears or a sword. When she rode on a bench, it would turn into a horse; if she rode a rope, it would change into a dragon; if she sat on a mat it would become a cloud and she could ride the cloud and fly away.

Chen, Janet Y, Pei-kai Cheng, Michael Elliot Lestz, and Jonathan D Spence. The Search for Modern China: A Documentary Collection. Third ed. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2014 (184-185).

Questions:

- According to these interviews, how did women support and lead in the Boxer Rebellion?

- Descriptions of the Red Lanterns sometimes describe them as having magical powers. Whether they really had these powers or not, what might the idea of these powers tell us about how people viewed the Red Lanterns?

Liu Rong And Xu Fen: A Symbol Of Chinese Women

The red lantern of the Red Lanterns is a symbol of the militancy of Chinese women; the daughters of the Red Lantern are the vanguard of the opposition of Chinese women to imperialism! Mountains may be leveled and the seas may be emptied, but the red lantern of revolution will never be extinguished!

Quoted in Liu Rong and Xu Fen. 1975. “Hongdeng nu’er song” [In praise of the daughters of the Red Lantern]. Tianjin shiyuan xuebao [Tianjin Teachers College journal] No. 2:78-82, 77.

Questions:

1. How does this document portray the Red Lanterns?

2. According to this document, how were women important to the Boxer Rebellion?

Quoted in Liu Rong and Xu Fen. 1975. “Hongdeng nu’er song” [In praise of the daughters of the Red Lantern]. Tianjin shiyuan xuebao [Tianjin Teachers College journal] No. 2:78-82, 77.

Questions:

1. How does this document portray the Red Lanterns?

2. According to this document, how were women important to the Boxer Rebellion?

Empress Dowager Cixi: Calls For Reform

The Empress Dowager Cixi was officially the regent, or the person ruling on behalf of the Guangxu Emperor. In 1898, the young emperor was removed from power and Cixi was effectively the ruler of China for another decade. During the Boxer Rebellion, she supported the Boxers and saw their efforts as a way to remove foreigners from China. In January 1901, she issued an edict that called for government reform in the aftermath of the Boxer Rebellion.

It was only by an appeal to the Empress Dowager to resume the reins of power that the court was saved from immediate peril and the evil rooted out in a single day… We have now received Her Majesty’s decree to devote ourselves fully to China’s revitalization, to suppress vigorously the use of the terms new and old, and to blend together the best of what is Chinese and what is foreign. The root of China’s weakness lies in harmful habits too firmly entrenched, in rules and regulations too minutely drawn…To sum up, administrative methods and regulations must be revised and abuses eradicated. If regeneration is truly desired, there must be quiet and reasoned deliberation…

We therefore call upon the members of the Grand Council, the Grand Secretaries, the Six Boards and Nine ministries, our ministers abroad, and the governors-general and governors of the provinces to reflect carefully on our present sad state of affairs and to scrutinize Chinese and Western governmental systems…Duly weigh what should be kept and what abolished, what new methods should be adopted and what old ones retained. By every available means of knowledge and observation, seek out how to renew our national strength, how to produce men of real talent, how to expand state revenues and how to revitalize the military…Without new systems, the corrupted old system cannot be salvaged…

The Empress Dowager and we have long pondered these matters. Now things are at a crisis point where change must occur, to transform weakness into strength. Everything depends upon how the change is effected.

Reform Edict of the Qing Imperial Government, January 29, 1901. Selections from Asia for Educators, Columbia University, http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/ps/cup/qing_reform_edict_1901.pdf.

Questions:

It was only by an appeal to the Empress Dowager to resume the reins of power that the court was saved from immediate peril and the evil rooted out in a single day… We have now received Her Majesty’s decree to devote ourselves fully to China’s revitalization, to suppress vigorously the use of the terms new and old, and to blend together the best of what is Chinese and what is foreign. The root of China’s weakness lies in harmful habits too firmly entrenched, in rules and regulations too minutely drawn…To sum up, administrative methods and regulations must be revised and abuses eradicated. If regeneration is truly desired, there must be quiet and reasoned deliberation…

We therefore call upon the members of the Grand Council, the Grand Secretaries, the Six Boards and Nine ministries, our ministers abroad, and the governors-general and governors of the provinces to reflect carefully on our present sad state of affairs and to scrutinize Chinese and Western governmental systems…Duly weigh what should be kept and what abolished, what new methods should be adopted and what old ones retained. By every available means of knowledge and observation, seek out how to renew our national strength, how to produce men of real talent, how to expand state revenues and how to revitalize the military…Without new systems, the corrupted old system cannot be salvaged…

The Empress Dowager and we have long pondered these matters. Now things are at a crisis point where change must occur, to transform weakness into strength. Everything depends upon how the change is effected.

Reform Edict of the Qing Imperial Government, January 29, 1901. Selections from Asia for Educators, Columbia University, http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/ps/cup/qing_reform_edict_1901.pdf.

Questions:

- What role did the Empress Dowager Cixi play in the Boxer Rebellion?

- What methods did Empress Dowager Cixi use to address the Boxer Rebellion, according to this document?

Princess Der Ling: Excerpt From Two Years In The Forbidden City

For two years, Princess Der Ling was the favorite lady-in-waiting to the Empress Dowager Cixi in the imperial palace in Beijing. This book provides a unique and surprisingly intimate portrait of the Dragon Lady, who ruled China for 47 years, and brought the country to the brink of destruction. Der Ling refers to the larger political context on many occasions. But the best parts of the book are the small details. What emerges is an intimate portrait of the life and personality of the Empress Dowager, and a sense of the inner workings of the highly secretive world of the imperial palace.

When I informed Her Majesty of the arrival of the portrait she ordered that it should be brought into her bedroom immediately. She scrutinized it very carefully for a while, even touching the painting in her curiosity. Finally she burst out laughing and said: "What a funny painting this is, it looks as though it had been painted with oil." (Of course it was an oil painting.) "Such rough work I never saw in all my life. The picture itself is marvellously like you, and I do not hesitate to say that none of our Chinese painters could get the expression which appears on this picture. What a funny dress you are wearing in this picture. Why are your arms and neck all bare? I have heard that foreign ladies wear their dresses without sleeves and without collars, but I had no idea that it was so bad and ugly as the dress you are wearing here. I cannot imagine how you could do it. I should have thought you would have been ashamed to expose yourself in that manner. Don't wear any more such dresses, please. It has quite shocked me. What a funny kind of civilization this is to be sure. Is this dress only worn on certain occasions, or is it worn any time, even when gentlemen are present?" I explained to her that it was the usual evening dress for ladies and was worn at dinners, balls, receptions, etc. Her Majesty laughed and exclaimed: "This is getting worse and worse. Everything seems to go backwards in foreign countries. Here we don't even expose our wrists when in the company of gentlemen, but foreigners seem to have quite different ideas on the subject. The Emperor is always talking about reform, but if this is a sample we had much better remain as we are. Tell me, have you yet changed your opinion with regard to foreign customs? Don't you think that our own customs are much nicer?" Of course I was obliged to say "yes" seeing that she herself was so prejudiced.

Der Ling. Two Years in the Forbidden City. Project Gutenberg. 1911.

Questions:

When I informed Her Majesty of the arrival of the portrait she ordered that it should be brought into her bedroom immediately. She scrutinized it very carefully for a while, even touching the painting in her curiosity. Finally she burst out laughing and said: "What a funny painting this is, it looks as though it had been painted with oil." (Of course it was an oil painting.) "Such rough work I never saw in all my life. The picture itself is marvellously like you, and I do not hesitate to say that none of our Chinese painters could get the expression which appears on this picture. What a funny dress you are wearing in this picture. Why are your arms and neck all bare? I have heard that foreign ladies wear their dresses without sleeves and without collars, but I had no idea that it was so bad and ugly as the dress you are wearing here. I cannot imagine how you could do it. I should have thought you would have been ashamed to expose yourself in that manner. Don't wear any more such dresses, please. It has quite shocked me. What a funny kind of civilization this is to be sure. Is this dress only worn on certain occasions, or is it worn any time, even when gentlemen are present?" I explained to her that it was the usual evening dress for ladies and was worn at dinners, balls, receptions, etc. Her Majesty laughed and exclaimed: "This is getting worse and worse. Everything seems to go backwards in foreign countries. Here we don't even expose our wrists when in the company of gentlemen, but foreigners seem to have quite different ideas on the subject. The Emperor is always talking about reform, but if this is a sample we had much better remain as we are. Tell me, have you yet changed your opinion with regard to foreign customs? Don't you think that our own customs are much nicer?" Of course I was obliged to say "yes" seeing that she herself was so prejudiced.

Der Ling. Two Years in the Forbidden City. Project Gutenberg. 1911.

Questions:

- Who is writing and how does she know the Empress?

- Does the Queen seem open to reforms to women’s dress? Why or why not?

Remedial Herstory Editors. "23. 1600-1850 CLOISTERED WOMEN IN ASIA." The Remedial Herstory Project. November 1, 2022. www.remedialherstory.com.

Primary AUTHOR: |

Kelsie Brook Eckert

|

Primary Reviewer: |

Jacqui Nelson

|

Consulting Team |

Editors |

|

Kelsie Brook Eckert, Project Director

Coordinator of Social Studies Education at Plymouth State University Dr. Nancy Locklin-Sofer, Consultant Professor of History at Maryville College. Chloe Gardner, Consultant PhD Candidate in Religious Studies at Edinburgh University Dr. Whitney Howarth, Consultant Former Professor of History at Plymouth State University Jacqui Nelson, Consultant Teaching Lecturer of Military History at Plymouth State University Maria Concepcion Marquez Sandoval PhD Candidate in History at Arizona University |

Amy Flanders

Humanities Teacher, Moultonborough Academy ReviewersAncient:

Dr. Kristin Heineman Professor of History at Colorado State University Dr. Bonnie Rock-McCutcheon Professor of History at Wilson College Sarah Stone PhD Candidate in Religious Studies at Edinburgh University Medieval: Dr. Katherine Koh Professor of History at La Sierra University Dr. Jonathan Couser Professor of History at Plymouth State University Dr. Shahla Haeri Professor of History at Boston University Lauren Cole PhD Candidate in History at Northwestern University Modern: Dr. Barbara Tischler Supervisor for Hunter College Dr. Pamela Scully Professor of Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies and African Studies at Emory University |

|

Early modern Japan was a military-bureaucratic state governed by patriarchal and patrilineal principles and laws. During this time, however, women had considerable power to directly affect social structure, political practice, and economic production. This apparent contradiction between official norms and experienced realities lies at the heart of The Problem of Women in Early Modern Japan. Examining prescriptive literature and instructional manuals for women—as well as diaries, memoirs, and letters written by and about individual women from the late seventeenth century to the early nineteenth century—Marcia Yonemoto explores the dynamic nature of Japanese women’s lives during the early modern era.

This book traces the social history of early modern Japan’s sex trade, from its beginnings in seventeenth-century cities to its apotheosis in the nineteenth-century countryside. Drawing on legal codes, diaries, town registers, petitions, and criminal records, it describes how the work of "selling women" transformed communities across the archipelago. By focusing on the social implications of prostitutes’ economic behavior, this study offers a new understanding of how and why women who work in the sex trade are marginalized. It also demonstrates how the patriarchal order of the early modern state was undermined by the emergence of the market economy, which changed the places of women in their households and the realm at large.

Analyzing a series of narratives that described women who transformed the worlds they lived in, this book introduces students and scholars to the lives of the women of Joseon Korea 1550-1700. Exploring both their interactions at home and abroad, this book shows how the agency of these women reached far across the globe.

The early modern Ottoman poet Mihrî Hatun (1460–1515) succeeded in drawing an admiring audience and considerable renown during a time when few women were accepted into the male-dominated intellectual circles. Her poetry collection is among the earliest bodies of women’s writing in the Middle East and Islamicate literature, providing an exceptional vantage point on intellectual history. With this volume, Havlioglu not only gives readers access to this rare text but also investigates the factors that allowed Mihri to survive and thrive despite her clear departure from the cultural norms of the time.

Bernadette Andrea’s groundbreaking study recovers and reinterprets the lives of women from the Islamic world who travelled, with varying degrees of volition, as slaves, captives, or trailing wives to Scotland and England during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Andrea’s thorough and insightful analysis of historical documents, visual records, and literary works focuses on five extraordinary women: Elen More and Lucy Negro, both from Islamic West Africa; Ipolita the Tartarian, a girl acquired from Islamic Central Asia; Teresa Sampsonia, a Circassian from the Safavid Empire; and Mariam Khanim, an Armenian from the Mughal Empire. By analyzing these women’s lives and their impact on the literary and cultural life of proto-colonial England, Andrea reveals that they are simultaneously significant constituents of the emerging Anglo-centric discourse of empire and cultural agents in their own right.

This volume delves into the literary lives of four Muslim women in pre-modern India. Three of them, Gulbadan Begam (1523-1603), the youngest daughter of Emperor Babur, Jahanara (1614-1681), the eldest daughter of Emperor Shah Jahan, and Zeb-un-Nissa (1638-1702), the eldest daughter of Emperor Aurangzeb, belonged to royalty. This monograph explores the political imagination of these Mughal women that was constructed through statist interactions of their royal fathers and brothers, and how such knowledge percolated through the relatively cloistered communal life of the 'zenana'.

Gond Rani Veerangana Durgawati, queen of the tribal kingdom of Garha Mandla, ruled more than 450 years ago and died fighting for her dharma. A survivor who was not afraid to stand up for her rights, she was a warrior smart enough to use terrain to counter much larger manpower and artillery strength, a devoted mother and a model monarch who looked after her people till her last breath-the fact that she lived in blood-soaked medieval India, makes her story even more remarkable.

|

|

|

The daughter of a Buddhist priest, Tsuneno was born in a rural Japanese village and was expected to live a traditional life much like her mother’s. But after three divorces - and a temperament much too strong-willed for her family’s approval - she ran away to make a life for herself in one of the largest cities in the world: Edo, a bustling metropolis at its peak.

The Mumtaz Chronicles is a series of historical fiction novellas that tell the epic tale of life in 16th century India, when royal women had great wealth and influence, despite being hidden from men other than their royal benefactors. In Book One, The Royal Harem, the daughter of a common accountant is invited into a world filled with luxury and intrigue, where she comes across information that could jeopardize her life as well as the life of her friends and family. Can the women of the Royal Harem work together to manage the dysfunctional relationship between the prince and the most powerful man in the empire?