24. 1850-1950 Women’s Industrial Revolution

|

The Industrial Revolution brought significant change for women. New procedures for caesarean section advanced medicine and treatment for child birth. Women also began to find new career options and leadership in the workforce, giving them new chances to climb and even dismantle the social ladder. Women also had union labor strikes, and protests for voting rights, signifying the beginning of cultural and societal shifts in regards to women's place in society. As our industries and global sphere began to shift, so did the jobs, opportunities, and lives of women during this time.

|

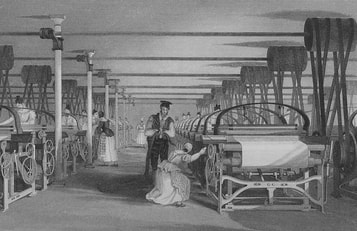

Industrial Women, Wikimedia Commons

Industrial Women, Wikimedia Commons

The Industrial Revolution began in England because of the natural resources available and the shift toward capitalist production. It resulted in many changes in society, including the type of work people did, where they lived, and the nature of their daily lives. These foundational changes also led to systemic changes such as who held power and how and where. Women of the laboring class went from domestic servants, weavers, and shopkeepers to being factory workers. Their increasing involvement in life outside the domestic world and the horrible conditions in the factories led to their greater political involvement and eventually demands for political rights.

Before Industrialization

The Industrial Revolution brought about fundamental change in English, then European, and later many other societies. Production shifted from small “manufactories” full of craftsmen and women to the mass production of goods in factories using steam and water power.

In the pre-industrial world, women had control of their day-to-day lives. As their work shifted to the factory, women worked about the same number of hours but in back breaking and repetitive labor. When they returned home, women were still responsible for their domestic duties. Caring for children in the pre-industrial world was possible because the children were always nearby, but in the industrial world, children were also working.

Midwives and Doctors

The practice of midwifery was one of the accepted ways that women worked outside the home around the world. Increasingly, governments worked to certify and professionalize industries, including medicine. Midwifery was generally a safe option in birth for women. High maternal death rates led to scholars examining the field scientifically, and men entered the field as “trained” obstetricians. Many of the men drawn to this field had personally lost loved ones at birth. In the 1500s, “The Rosengarten” became the first obstetrical textbook written by a male apothecary. It provided instructions, probably taken from common (female) midwife practices, on how to rotate the baby with pressure on the abdomen to get it into the proper position. It also introduced new methods and tools to extract the baby. Women at the time were largely illiterate, so how many of the midwives attending women at birth were familiar with the content of the text is hard to say, but the result of this and another text was tension between the midwives who had made careers in a field available to them that male doctors took over in the name of professionalism.

Before Industrialization

The Industrial Revolution brought about fundamental change in English, then European, and later many other societies. Production shifted from small “manufactories” full of craftsmen and women to the mass production of goods in factories using steam and water power.

In the pre-industrial world, women had control of their day-to-day lives. As their work shifted to the factory, women worked about the same number of hours but in back breaking and repetitive labor. When they returned home, women were still responsible for their domestic duties. Caring for children in the pre-industrial world was possible because the children were always nearby, but in the industrial world, children were also working.

Midwives and Doctors

The practice of midwifery was one of the accepted ways that women worked outside the home around the world. Increasingly, governments worked to certify and professionalize industries, including medicine. Midwifery was generally a safe option in birth for women. High maternal death rates led to scholars examining the field scientifically, and men entered the field as “trained” obstetricians. Many of the men drawn to this field had personally lost loved ones at birth. In the 1500s, “The Rosengarten” became the first obstetrical textbook written by a male apothecary. It provided instructions, probably taken from common (female) midwife practices, on how to rotate the baby with pressure on the abdomen to get it into the proper position. It also introduced new methods and tools to extract the baby. Women at the time were largely illiterate, so how many of the midwives attending women at birth were familiar with the content of the text is hard to say, but the result of this and another text was tension between the midwives who had made careers in a field available to them that male doctors took over in the name of professionalism.

Midwifery, Public Domain

Midwifery, Public Domain

The “professionalization” of midwifery really damaged female patients. Their physicians had never been through what they were going through, and Victorian gendered expectations respected women’s modesty. Sometimes, the doctors wouldn’t even look during the birthing process. Women died at higher rates under these male doctors, but still the doctors drove female midwives out of their jobs.

In the battle between midwives and male doctors, it’s wrong to assume midwives weren’t using medical instruments for interventions. Sarah Stone and Margaret Stephen, both female midwives in the late 1700s, used them. But the male doctors won the battle for the monopoly on birth. In America by the 1800s, especially among the wealthy and urban, doctors were preferred. No longer did women give birth with their female neighbors there for support and advice. Rather, they gave birth alone with just their mother and a male doctor in attendance. In Philadelphia over a ten-year period, the number of midwives fell from 21 to 6. As men were not allowed to look at a naked woman, even during childbirth, male medical students weren’t allowed to watch births, so instead learned from textbooks.

Throughout history, caesarian sections had been performed. The surgery was reserved for circumstances when it was evident the mother was dying or already dead and there was a chance to save the baby. Having a caesarian section was basically a death sentence. In 1814, a report from London announced that only 20-22 cesarean sections had been attempted in the empire and only nine had succeeded in saving the babies, while just two had succeeded in saving the mother. The first undisputed and well-documented caesarian section in Ireland took place in 1738 and saved both mother and baby; it was performed by a female midwife, Mary Donally. She was called to help Alice O’Neal, the thirty-year-old wife of an Irish farmer who had been in labor for twelve days. Mary cut Alice’s stomach with a razor while an assistant walked a mile to get silk to stitch the mother up. Even though the surgery worked, the medical community in Europe debated the validity of the procedure and few were willing to perform it, even into the 1900s. In Britain, there was much more support for killing the baby to save the mother, and so much of the debate was about which life was more valuable .

In the battle between midwives and male doctors, it’s wrong to assume midwives weren’t using medical instruments for interventions. Sarah Stone and Margaret Stephen, both female midwives in the late 1700s, used them. But the male doctors won the battle for the monopoly on birth. In America by the 1800s, especially among the wealthy and urban, doctors were preferred. No longer did women give birth with their female neighbors there for support and advice. Rather, they gave birth alone with just their mother and a male doctor in attendance. In Philadelphia over a ten-year period, the number of midwives fell from 21 to 6. As men were not allowed to look at a naked woman, even during childbirth, male medical students weren’t allowed to watch births, so instead learned from textbooks.

Throughout history, caesarian sections had been performed. The surgery was reserved for circumstances when it was evident the mother was dying or already dead and there was a chance to save the baby. Having a caesarian section was basically a death sentence. In 1814, a report from London announced that only 20-22 cesarean sections had been attempted in the empire and only nine had succeeded in saving the babies, while just two had succeeded in saving the mother. The first undisputed and well-documented caesarian section in Ireland took place in 1738 and saved both mother and baby; it was performed by a female midwife, Mary Donally. She was called to help Alice O’Neal, the thirty-year-old wife of an Irish farmer who had been in labor for twelve days. Mary cut Alice’s stomach with a razor while an assistant walked a mile to get silk to stitch the mother up. Even though the surgery worked, the medical community in Europe debated the validity of the procedure and few were willing to perform it, even into the 1900s. In Britain, there was much more support for killing the baby to save the mother, and so much of the debate was about which life was more valuable .

Dr. James Berry, Wikimedia Commons

Dr. James Berry, Wikimedia Commons

Life without the C-section meant many women continued to die, regardless of their status and access to the best medical care. Most notably, in 1817, Princess Charlotte, George IV's only child, died in childbirth at the young age of 21. Her baby was two weeks late and labor lasted for 50 hours. The nine-pound baby was stillborn. Doctors removed the placenta with difficulty, and six hours later Charlotte died. The obstetrician, Sir Richard Croft, was harassed mercilessly by the masses. He shot himself a few days later. King George was left without an heir, and the throne passed first to his brother and then to his niece, who became Queen Victoria.

A notable case of a successful cesarean section occurred in South Africa in 1826, by Dr. James Barry. Barry was identified as female at birth and raised as a girl by the name of Margaret Ann Bulkley. When his uncle died, he assumed the name James in his stead and used his new identity as an opportunity for self-betterment, enrolling in medical school in Edenborough. He seems to have identified as male for the rest of his life. Barry had been raped as a youth and the resulting child was raised by his mother, but the stretch marks from pregnancy remained for his entire life. Barry had a highly successful and controversial medical career, serving as a physician all over the world and in the Crimean War. While in South Africa, he performed a caesarian section that saved both the mother and child. The grateful mother named her new baby James in his honor. When Barry died years later, it was discovered that he was female or perhaps intersex. How he would have liked to be remembered is sadly unknown.

In hospitals, before germs were understood and sterilization common, doctors would go from surgery to surgery carrying infections to women in labor. By the 1800s, maternal death rate reached between two and eight per 100 deliveries, around 10 times the rate outside the hospital. In New York, in 1840, 80 percent of women who gave birth in a hospital died.

The discovery of anesthesia like chloroform was not far behind, but like the C-section, many were reluctant to use it in labor. Queen Victoria consented to its use during the birth of her eighth child and it quickly became widely accepted in obstetric practice.

Industrial Revolution

All over the world, the transition from an agricultural and cottage-based society to an industrial one was painful, full of failures, insecurities, and tension.

The nature of work done by women and men often reveals the attitudes, beliefs, and values that a society holds about gender differences. In most of Europe and East Asia, women were regarded as inherently docile, accustomed to using small muscles, and having considerable tolerance for monotony and detail. With these assumptions, women more than men were believed to be ideal assembly-line workers. Because of their supposed compliance, they would be willing to take lower wages and handle repetitive assembly line work, doing tasks that were already defined as womens’ work.

Lower class women, who, out of necessity, worked for a wage, were seen as “unsexing” themselves and entering into the cutthroat “man’s world.” Women were seen as desirable employees. Teenage girls, who had already learned manual dexterity at home, were thought to have the “special skills,” which is code for the fact that they were manipulatable. Employers used these gender-based characteristics to direct women toward grueling, low paying jobs and away from work that required training or leadership. Rarely did anyone question that running large, complex machinery was anything but a “man’s job.” For example, the more an expensive spinning mule became a male-operated machine, the male mule spinners union opposed the employment of women and children.

A notable case of a successful cesarean section occurred in South Africa in 1826, by Dr. James Barry. Barry was identified as female at birth and raised as a girl by the name of Margaret Ann Bulkley. When his uncle died, he assumed the name James in his stead and used his new identity as an opportunity for self-betterment, enrolling in medical school in Edenborough. He seems to have identified as male for the rest of his life. Barry had been raped as a youth and the resulting child was raised by his mother, but the stretch marks from pregnancy remained for his entire life. Barry had a highly successful and controversial medical career, serving as a physician all over the world and in the Crimean War. While in South Africa, he performed a caesarian section that saved both the mother and child. The grateful mother named her new baby James in his honor. When Barry died years later, it was discovered that he was female or perhaps intersex. How he would have liked to be remembered is sadly unknown.

In hospitals, before germs were understood and sterilization common, doctors would go from surgery to surgery carrying infections to women in labor. By the 1800s, maternal death rate reached between two and eight per 100 deliveries, around 10 times the rate outside the hospital. In New York, in 1840, 80 percent of women who gave birth in a hospital died.

The discovery of anesthesia like chloroform was not far behind, but like the C-section, many were reluctant to use it in labor. Queen Victoria consented to its use during the birth of her eighth child and it quickly became widely accepted in obstetric practice.

Industrial Revolution

All over the world, the transition from an agricultural and cottage-based society to an industrial one was painful, full of failures, insecurities, and tension.

The nature of work done by women and men often reveals the attitudes, beliefs, and values that a society holds about gender differences. In most of Europe and East Asia, women were regarded as inherently docile, accustomed to using small muscles, and having considerable tolerance for monotony and detail. With these assumptions, women more than men were believed to be ideal assembly-line workers. Because of their supposed compliance, they would be willing to take lower wages and handle repetitive assembly line work, doing tasks that were already defined as womens’ work.

Lower class women, who, out of necessity, worked for a wage, were seen as “unsexing” themselves and entering into the cutthroat “man’s world.” Women were seen as desirable employees. Teenage girls, who had already learned manual dexterity at home, were thought to have the “special skills,” which is code for the fact that they were manipulatable. Employers used these gender-based characteristics to direct women toward grueling, low paying jobs and away from work that required training or leadership. Rarely did anyone question that running large, complex machinery was anything but a “man’s job.” For example, the more an expensive spinning mule became a male-operated machine, the male mule spinners union opposed the employment of women and children.

European Textile Workers, Public Domain

European Textile Workers, Public Domain

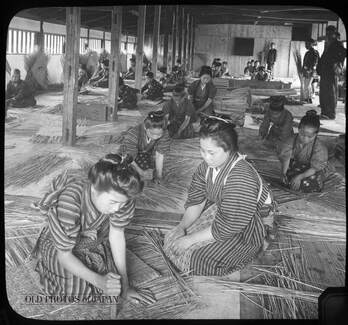

This pattern of gendered job segregation was notably true in Asia, where deeply-rooted gender norms and values played a large role in influencing labor patterns. At work, women were praised for “knowing their place,” for being more flexible than men, and for being subordinate to men and their masters.Women’s earnings were always lower in jobs they held equally with men, and they were unlikely to have access to supervisory positions or promotional ladders. At first, Asian women had no mutual aid societies and were largely excluded from collective action, such as strikes, work slowdown or stoppages. Accustomed to a patriarchal world in which male authority ruled and with few alternatives, working class women took whatever pay and conditions offered them in order to feed themselves and their family.

Women in the factories and mines of Europe and Asia during the formative years of industrialization were subjected to similar forms of exploitation and control. Everywhere the work tended to be dehumanizing and monotonous. Fourteen to sixteen hour shifts controlled by the clock and under the watchful eye of harsh male supervisors, were normal. The women worked six days a week. Sexual harassment was common. The workplace environment was an incubator for illnesses such as tuberculosis and dysentery. Safety measures were weak, and accidents were frequently reported, as were physical deformities caused by hard, repetitive work and poisoning caused by unsafe chemicals. When factory work removed young women from their parental households, factory owners often established dormitories for the workers and acted as substitute fathers. This system restricted women’s leisure-time activities and socializing habits, while ensuring that their wages would be sent home. Married women were encouraged to work at home if possible.

Women in the factories and mines of Europe and Asia during the formative years of industrialization were subjected to similar forms of exploitation and control. Everywhere the work tended to be dehumanizing and monotonous. Fourteen to sixteen hour shifts controlled by the clock and under the watchful eye of harsh male supervisors, were normal. The women worked six days a week. Sexual harassment was common. The workplace environment was an incubator for illnesses such as tuberculosis and dysentery. Safety measures were weak, and accidents were frequently reported, as were physical deformities caused by hard, repetitive work and poisoning caused by unsafe chemicals. When factory work removed young women from their parental households, factory owners often established dormitories for the workers and acted as substitute fathers. This system restricted women’s leisure-time activities and socializing habits, while ensuring that their wages would be sent home. Married women were encouraged to work at home if possible.

Japanese Textile Workers, Wikimedia Commons

Japanese Textile Workers, Wikimedia Commons

Around the world, working class women moved into cities and took up jobs, entering into the paid workforce in greater numbers than ever before. This changed the economic value of the unpaid domestic work women had been doing for milenia. The cultural effect of women earning a wage was that their domestic labor lost its value. The degradation of domestic work undermined its importance. Men of the working class could not earn enough to also pay for domestic labor, and thus families relied on the unpaid labor of women.

Women played a crucial role in supplying the labor that made industrialization possible. As household industries shifted to factories or centralized workshops, women in great numbers were sought to work in the mills. Most common was work in the textile mills. Histories of industrial revolutions everywhere began with the work of women textile workers. Recognizing this, one Japanese worker’s song says, “Factory girls are treasure chests for the company.”

It was no coincidence that women and children comprised much of the workforce of the early factories.

To run a successful factory, an owner needed cheap labor. Women in the 1800s and 1900s had few alternatives for work, and they took whatever pay and conditions were offered in order to feed themselves and their families. Women also were sought as desirable employees because of age-old beliefs that they, more than men, were nimble-fingered, dexterous, careful, meticulous and quick. Accustomed to a patriarchal world in which male authority ruled, employers also counted on women to be compliant, docile workers. For example, the tradition that valued absolute allegiance to a master was used to reinforce obedience at work among girls from Samurai Japanese families.

Families played an important role in sending daughters off to factories. In Europe, girls’ incomes were important to their families as well as to their dowries. Japan’s first workers in government mills were women from poor farm families that had “excess” daughters. A daughter’s work away from home was seen as part of the patriotic effort to industrialize the nation. It was also a requirement of their filial duty to contribute to the well-being of their parents. In China, a woman’s farm work was seen as less essential to the family economy than was a man’s. Impoverished families willingly signed contracts committing their daughters to long terms as indentured workers in the mills in return for advance cash loans.

In all cases, large factories offered ways to protect their female workforce. Through promises to supervise young females and their morals and in some cases provide safe, controlled housing in company dorms, factories became like second parents. Familial duties in a sense were transferred from the home to the patriarchal factory.

Women played a crucial role in supplying the labor that made industrialization possible. As household industries shifted to factories or centralized workshops, women in great numbers were sought to work in the mills. Most common was work in the textile mills. Histories of industrial revolutions everywhere began with the work of women textile workers. Recognizing this, one Japanese worker’s song says, “Factory girls are treasure chests for the company.”

It was no coincidence that women and children comprised much of the workforce of the early factories.

To run a successful factory, an owner needed cheap labor. Women in the 1800s and 1900s had few alternatives for work, and they took whatever pay and conditions were offered in order to feed themselves and their families. Women also were sought as desirable employees because of age-old beliefs that they, more than men, were nimble-fingered, dexterous, careful, meticulous and quick. Accustomed to a patriarchal world in which male authority ruled, employers also counted on women to be compliant, docile workers. For example, the tradition that valued absolute allegiance to a master was used to reinforce obedience at work among girls from Samurai Japanese families.

Families played an important role in sending daughters off to factories. In Europe, girls’ incomes were important to their families as well as to their dowries. Japan’s first workers in government mills were women from poor farm families that had “excess” daughters. A daughter’s work away from home was seen as part of the patriotic effort to industrialize the nation. It was also a requirement of their filial duty to contribute to the well-being of their parents. In China, a woman’s farm work was seen as less essential to the family economy than was a man’s. Impoverished families willingly signed contracts committing their daughters to long terms as indentured workers in the mills in return for advance cash loans.

In all cases, large factories offered ways to protect their female workforce. Through promises to supervise young females and their morals and in some cases provide safe, controlled housing in company dorms, factories became like second parents. Familial duties in a sense were transferred from the home to the patriarchal factory.

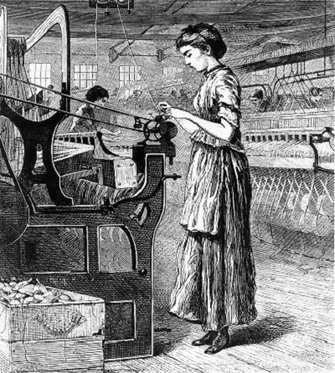

Spinning Jenny, Wikimedia Commons

Spinning Jenny, Wikimedia Commons

The large demand for female labor was tempting for many women. In Europe, given the choice between taxing farm work or demeaning domestic service, many women chose factory work for the money and independence it seemed to offer. In Japan, recruiters went into the countryside with tempting offers of good wages, pleasant working conditions, and tasty food. Within the workplace, men’s and women’s work were different and hardly ever equal. Women remained in lower-paid and lesser-authority positions throughout their careers, even in the industries, such as textile, where they dominated.

The Industrial Revolution was spawned by a legal system that encouraged invention. Thousands of inventions, big and small, transformed the technology and thus made the economy and production more efficient. Women were likely behind many of these inventions.

An important invention for women was the Spinning Jenny, which was invented in 1764 by James Hargreaves. This complex device cut the time and effort needed to produce cloth and transformed the textile industry. Women no longer sat at spinning wheels; they stood, 12-14 hours a day at the Jenny, working eight spools at once. The work was excruciating. Hannah Goode described her day to a government official, stating, "I work at Mr. Wilson's mill. I think the youngest child is about 7. I daresay there are 20 under 9 years. It is about half past five by our clock at home when we go in....We come out at seven by the mill. We never stop to take our meals, except at dinner. William Crookes is overlooker in our room. He is cross-tempered sometimes. He does not beat me; he beats the little children if they do not do their work right....I have sometimes seen the little children drop asleep or so, but not lately. If they are catched asleep they get the strap. They are always very tired at night....I can read a little; I can't write. I used to go to school before I went to the mill; I have since I am sixteen."

Mrs. Smith had three children working at the same mill. She said, "We don't complain. If they go to drop the hours, I don't know what poor people will do. We have hard work to live as it is. ...My husband is of the same mind about it...last summer my husband was 6 weeks ill; we pledged almost all our things to live; the things are not all out of pawn yet… We complain of nothing but short wages...My children have been in the mill three years. I have no complaint to make of their being beaten...I would rather they were beaten than fined."

Despite the mother’s hearty perspective, society was concerned about the way women in these factories were treated. One popular ballad sang: “Laboriously toiling, both night, noon, and morning/ For a wretched subsistence, now mark what I say. She's quite unprotected, forlorn, and dejected/ For sixpence, or eightpence, or tenpence a day. Come forward you nobles, and grant them assistance/ Give them employ, and a fair price them pay/ And then you will find, the poor hard working seamstress/ From honor and virtue will not go astray.”

The Industrial Revolution was spawned by a legal system that encouraged invention. Thousands of inventions, big and small, transformed the technology and thus made the economy and production more efficient. Women were likely behind many of these inventions.

An important invention for women was the Spinning Jenny, which was invented in 1764 by James Hargreaves. This complex device cut the time and effort needed to produce cloth and transformed the textile industry. Women no longer sat at spinning wheels; they stood, 12-14 hours a day at the Jenny, working eight spools at once. The work was excruciating. Hannah Goode described her day to a government official, stating, "I work at Mr. Wilson's mill. I think the youngest child is about 7. I daresay there are 20 under 9 years. It is about half past five by our clock at home when we go in....We come out at seven by the mill. We never stop to take our meals, except at dinner. William Crookes is overlooker in our room. He is cross-tempered sometimes. He does not beat me; he beats the little children if they do not do their work right....I have sometimes seen the little children drop asleep or so, but not lately. If they are catched asleep they get the strap. They are always very tired at night....I can read a little; I can't write. I used to go to school before I went to the mill; I have since I am sixteen."

Mrs. Smith had three children working at the same mill. She said, "We don't complain. If they go to drop the hours, I don't know what poor people will do. We have hard work to live as it is. ...My husband is of the same mind about it...last summer my husband was 6 weeks ill; we pledged almost all our things to live; the things are not all out of pawn yet… We complain of nothing but short wages...My children have been in the mill three years. I have no complaint to make of their being beaten...I would rather they were beaten than fined."

Despite the mother’s hearty perspective, society was concerned about the way women in these factories were treated. One popular ballad sang: “Laboriously toiling, both night, noon, and morning/ For a wretched subsistence, now mark what I say. She's quite unprotected, forlorn, and dejected/ For sixpence, or eightpence, or tenpence a day. Come forward you nobles, and grant them assistance/ Give them employ, and a fair price them pay/ And then you will find, the poor hard working seamstress/ From honor and virtue will not go astray.”

Women in the Coal Mines, Wikimedia Commons

Women in the Coal Mines, Wikimedia Commons

Coal Mines

For women of the working class, the best occupation one could get was in service. Following that was factory work, and the worst was in a mine. A six year old girl described her grueling work, "I have been down six weeks and make 10 to 14 rakes a day; I carry a full 56 lbs. of coal in a wooden bucket. I work with sister Jesse and mother. It is dark the time we go."

Maria Gooder’s testimony shows how, despite her constant working, she still had very little. "I hurry for a man with my sister Anne who is going 18. He is good to us. I don't like being in the pit. I am tired and afraid. I go at 4:30 after having porridge for breakfast. I start hurrying at 5. We have dinner at noon. We have dry bread and nothing else. There is water in the pit but we don't sup it."

Mary Enock worked in the mines with her sister and was just eleven years old. She said, “We are door-keepers in the four foot level. We leave the house before six each morning and are in the level until seven o’clock and sometimes later. We get 2p a day and our light costs us 2 ½ p. a week. Rachel was in a day school and she can read a little. She was run over by a tram a while ago and was home ill a long time, but she has got over it.”

For women of the working class, the best occupation one could get was in service. Following that was factory work, and the worst was in a mine. A six year old girl described her grueling work, "I have been down six weeks and make 10 to 14 rakes a day; I carry a full 56 lbs. of coal in a wooden bucket. I work with sister Jesse and mother. It is dark the time we go."

Maria Gooder’s testimony shows how, despite her constant working, she still had very little. "I hurry for a man with my sister Anne who is going 18. He is good to us. I don't like being in the pit. I am tired and afraid. I go at 4:30 after having porridge for breakfast. I start hurrying at 5. We have dinner at noon. We have dry bread and nothing else. There is water in the pit but we don't sup it."

Mary Enock worked in the mines with her sister and was just eleven years old. She said, “We are door-keepers in the four foot level. We leave the house before six each morning and are in the level until seven o’clock and sometimes later. We get 2p a day and our light costs us 2 ½ p. a week. Rachel was in a day school and she can read a little. She was run over by a tram a while ago and was home ill a long time, but she has got over it.”

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

Middle and Upper Classes

Industrialization brought the decline of the British aristocracy and the rise of the middle class. Women of the middle classes represented the ideal, in contrast to her lower class counterpart. A man who could provide enough for a wife to be spared working outside the home was a sign of

one’s class. Thus, working men began to agitate and unionize to protect their wages to provide for their wives at the expense of working women. Middle class and upper class women were mothers, homemakers, moral guideposts, and emotional supports. They were expected to strive for perfection in every aspect of their lives, and in return, women of this class were to be protected from the harsh realities of the capitalist world beyond the domestic sphere.

Over time, this idealized woman came to be seen as natural, even though historical records tell us otherwise. In Japan and China, there was contradictory government rhetoric calling for more women to join factory work, but there was also pressure for women to remain strictly in the home.

Women were encouraged to maintain “fine” homes that included the latest decor and were neat and clean. Women often had large families, and the pressure to meet all of these social demands necessitated domestic servants. Demand for servants rapidly increased and became one of the most common jobs for English women in the 1800s. Unmarried women who previously labored in family businesses and on farms shifted to working as domestic servants.

Servants provided middle and upper class women with more leisure time. Women became avid readers and writers, which made them one of the most educated groups of women in history. These ladies threw themselves into the socially acceptable charitable work and social reforms addressing the ills of industrialization. While we have a plethora of middle class female voices from this period, the everyday experience of working class women was largely ignored.

Upper class women became advocates for poor women and children. Speakers against alcoholism known as Temperance Reformers and abolitionists worked to end child labor, and more. The idealized version of womanhood was ever present. Some of these elite women, out of touch with the realities of the poor, claimed paid labor was unsuitable for women, as it was detrimental to her domestic duties. But how were these women supposed to feed their families?

This work forced upper class women to become political in ways yet seen by mass groups of women. They advocated for the Married Women’s Property Acts of 1870 and 1882, which gave women the right to control their finances, even within marriage. This also resulted in sweeping new laws that aimed to protect women but which ultimately created massive hurdles for working women. They claimed women’s bodies were too weak and delicate for some types of work and blocked women from competing with men in certain industries.

Some middle and upper class women became teachers until they were married in order to provide the education needed in an industrialized society. Girls received education related to domestic skills for their future as housewives and domestic servants. In Britain, women were barred from colleges and universities until the 1870s. Some European women did attend college, sat for exams, but the schools would not issue them degrees on account of their sex.

Industrialization brought the decline of the British aristocracy and the rise of the middle class. Women of the middle classes represented the ideal, in contrast to her lower class counterpart. A man who could provide enough for a wife to be spared working outside the home was a sign of

one’s class. Thus, working men began to agitate and unionize to protect their wages to provide for their wives at the expense of working women. Middle class and upper class women were mothers, homemakers, moral guideposts, and emotional supports. They were expected to strive for perfection in every aspect of their lives, and in return, women of this class were to be protected from the harsh realities of the capitalist world beyond the domestic sphere.

Over time, this idealized woman came to be seen as natural, even though historical records tell us otherwise. In Japan and China, there was contradictory government rhetoric calling for more women to join factory work, but there was also pressure for women to remain strictly in the home.

Women were encouraged to maintain “fine” homes that included the latest decor and were neat and clean. Women often had large families, and the pressure to meet all of these social demands necessitated domestic servants. Demand for servants rapidly increased and became one of the most common jobs for English women in the 1800s. Unmarried women who previously labored in family businesses and on farms shifted to working as domestic servants.

Servants provided middle and upper class women with more leisure time. Women became avid readers and writers, which made them one of the most educated groups of women in history. These ladies threw themselves into the socially acceptable charitable work and social reforms addressing the ills of industrialization. While we have a plethora of middle class female voices from this period, the everyday experience of working class women was largely ignored.

Upper class women became advocates for poor women and children. Speakers against alcoholism known as Temperance Reformers and abolitionists worked to end child labor, and more. The idealized version of womanhood was ever present. Some of these elite women, out of touch with the realities of the poor, claimed paid labor was unsuitable for women, as it was detrimental to her domestic duties. But how were these women supposed to feed their families?

This work forced upper class women to become political in ways yet seen by mass groups of women. They advocated for the Married Women’s Property Acts of 1870 and 1882, which gave women the right to control their finances, even within marriage. This also resulted in sweeping new laws that aimed to protect women but which ultimately created massive hurdles for working women. They claimed women’s bodies were too weak and delicate for some types of work and blocked women from competing with men in certain industries.

Some middle and upper class women became teachers until they were married in order to provide the education needed in an industrialized society. Girls received education related to domestic skills for their future as housewives and domestic servants. In Britain, women were barred from colleges and universities until the 1870s. Some European women did attend college, sat for exams, but the schools would not issue them degrees on account of their sex.

Japanese Industrial Workers, Public Domain

Japanese Industrial Workers, Public Domain

Labor Unions and Protest

Eventually, the realities of industry were investigated by a government commission in Britain. The documents revealed that women on average earned one-third to two-thirds of male salaries. It was a contrived pay scale that protected the male provider and head of house. This was one of many ways industrial society was designed to protect men and their wealth. Trade unions, for example, often barred women from entering and denied them training in advanced skills.

But women will only take so much before they stand up and demand change. Some women became politically active and formed unions. The Women’s Trade Union League formed in Britain in 1874, resulting in a massive influx of women’s union activity.

Similar patterns were seen in Japan when women organized massive strikes in the 1880s over low wages and contracts that forced them to live in housing away from home. There, women showed agency by running away from their jobs to be with their families.

There were differences in women’s behaviors based on marital status. Married women tended to participate less in militant activities. These women were responsible for their jobs as well as their unpaid domestic work. Male unions resisted female labor and unionization, as it posed a real threat to male jobs and wage security. Unions enforced a gender hierarchy, describing women as cheap, unskilled labor. Women’s involvement in labor unions resulted in incremental change. Pay, working conditions, and living conditions improved wherever unions took root, but change didn’t happen quickly enough.

Eventually, the realities of industry were investigated by a government commission in Britain. The documents revealed that women on average earned one-third to two-thirds of male salaries. It was a contrived pay scale that protected the male provider and head of house. This was one of many ways industrial society was designed to protect men and their wealth. Trade unions, for example, often barred women from entering and denied them training in advanced skills.

But women will only take so much before they stand up and demand change. Some women became politically active and formed unions. The Women’s Trade Union League formed in Britain in 1874, resulting in a massive influx of women’s union activity.

Similar patterns were seen in Japan when women organized massive strikes in the 1880s over low wages and contracts that forced them to live in housing away from home. There, women showed agency by running away from their jobs to be with their families.

There were differences in women’s behaviors based on marital status. Married women tended to participate less in militant activities. These women were responsible for their jobs as well as their unpaid domestic work. Male unions resisted female labor and unionization, as it posed a real threat to male jobs and wage security. Unions enforced a gender hierarchy, describing women as cheap, unskilled labor. Women’s involvement in labor unions resulted in incremental change. Pay, working conditions, and living conditions improved wherever unions took root, but change didn’t happen quickly enough.

Muriel Matters, Wikimedia Commons

Muriel Matters, Wikimedia Commons

Voting Rights

Industrialization took women and girls from farms, cottage industries, and domestic work and dragged them into a world dominated by men. Unionization led to slow change, and many women were fed up. Industrial labor and the failure of the unions and the law to protect women from exploitive pay, sexual harassment, and dangerous working conditions, hurled many women into political advocacy, where they eventually demanded the right to vote. They wanted the ballot, just like men.

New Zealand gave women the right to vote, known as enfranchisement, in 1893, making it the first nation to allow women to vote in national elections. Australia followed, when it became a federal state in 1901. Muriel Matters and Vida Goldstein were two of the many women who fought for women’s political recognition in Australia. Australian women were both admired and feared around the world.

Vida Goldstein became the first Australian to visit a president at the White House. President Theodore Roosevelt found her fascinating, as she had more political rights than any US woman. He said, “I’ve got my eye on you down in Australia.”

Australia continues to lead the world in female leadership., largely because they focused their efforts on reforming the structures and systems that made it difficult for women to participate in politics and leadership. Their model and countless academic studies shows that where women lead, there are enormous benefits, not only for women and girls, but for all of society.

Muriel Matters didn’t stop with Australia. Once suffrage was secure there, she headed to the United Kingdom, where suffrage had been a hot topic since the 1860s. In 1902, 37,000 women and girls who labored in the textile mills of Northern England petitioned Parliament for the right to vote, but nothing changed.

By 1905, British women were fed up with inaction on suffrage. It was then the mother daughter trio of Emmeline, Christabel, and Sylvia Pankhurst championed the militant wing of the English suffragette movement, the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), adopting the motto, “Deeds not Words.”

In 1907, 75 WSPU suffragettes were arrested when they attempted to storm the Houses of Parliament. They picketted, smashed mainstreet storefronts, bombed parliamentarian mailboxes, and performed a variety of stunts to get suffrage on the front page of British newspapers. Their international organization promoted militancy and pageantry as a means to an end.

In 1908, Muriel Matters, the Australian, earned the title of the first woman to speak in the British House of Commons in London because she chained herself to the grill that barred women’s view of parliament and shouted demands for women’s rights.

Guards cut her off the grill and dragged her out by force., even as she continued to demand the vote. Of course, not all women liked these tactics. Some left the Pankhersts for the more moderate Women’s Freedom League (WFL), while other women formed the UK’s first anti-suffrage league. But the suffragists kept fighting. In 1909, Marion Wallace Dunlop went on hunger strike while in prison and others soon followed her. Instead of releasing the women from prison, the jailers force fed them to keep them alive. Women began refusing to pay taxes until they could vote for the people who taxed them. They organized into the Women's Tax Resistance League (WTRL) with the slogan “No vote, no tax.”

Industrialization took women and girls from farms, cottage industries, and domestic work and dragged them into a world dominated by men. Unionization led to slow change, and many women were fed up. Industrial labor and the failure of the unions and the law to protect women from exploitive pay, sexual harassment, and dangerous working conditions, hurled many women into political advocacy, where they eventually demanded the right to vote. They wanted the ballot, just like men.

New Zealand gave women the right to vote, known as enfranchisement, in 1893, making it the first nation to allow women to vote in national elections. Australia followed, when it became a federal state in 1901. Muriel Matters and Vida Goldstein were two of the many women who fought for women’s political recognition in Australia. Australian women were both admired and feared around the world.

Vida Goldstein became the first Australian to visit a president at the White House. President Theodore Roosevelt found her fascinating, as she had more political rights than any US woman. He said, “I’ve got my eye on you down in Australia.”

Australia continues to lead the world in female leadership., largely because they focused their efforts on reforming the structures and systems that made it difficult for women to participate in politics and leadership. Their model and countless academic studies shows that where women lead, there are enormous benefits, not only for women and girls, but for all of society.

Muriel Matters didn’t stop with Australia. Once suffrage was secure there, she headed to the United Kingdom, where suffrage had been a hot topic since the 1860s. In 1902, 37,000 women and girls who labored in the textile mills of Northern England petitioned Parliament for the right to vote, but nothing changed.

By 1905, British women were fed up with inaction on suffrage. It was then the mother daughter trio of Emmeline, Christabel, and Sylvia Pankhurst championed the militant wing of the English suffragette movement, the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), adopting the motto, “Deeds not Words.”

In 1907, 75 WSPU suffragettes were arrested when they attempted to storm the Houses of Parliament. They picketted, smashed mainstreet storefronts, bombed parliamentarian mailboxes, and performed a variety of stunts to get suffrage on the front page of British newspapers. Their international organization promoted militancy and pageantry as a means to an end.

In 1908, Muriel Matters, the Australian, earned the title of the first woman to speak in the British House of Commons in London because she chained herself to the grill that barred women’s view of parliament and shouted demands for women’s rights.

Guards cut her off the grill and dragged her out by force., even as she continued to demand the vote. Of course, not all women liked these tactics. Some left the Pankhersts for the more moderate Women’s Freedom League (WFL), while other women formed the UK’s first anti-suffrage league. But the suffragists kept fighting. In 1909, Marion Wallace Dunlop went on hunger strike while in prison and others soon followed her. Instead of releasing the women from prison, the jailers force fed them to keep them alive. Women began refusing to pay taxes until they could vote for the people who taxed them. They organized into the Women's Tax Resistance League (WTRL) with the slogan “No vote, no tax.”

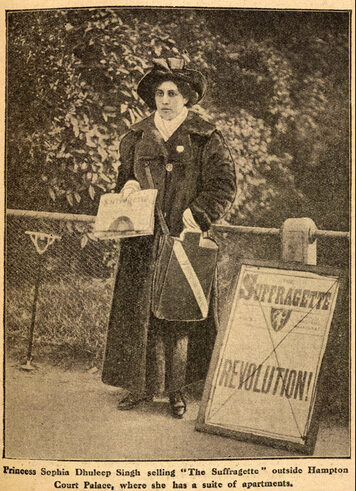

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

Sophia Duleep Singh stood out among the suffragists because of her position and heritage. She was the youngest daughter of the king of northern India. When her father was young he was bullied into a treaty with Queen Victoria that surrendered his country to her. He and his family were banished from India. In the United Kingdom, Sophia became Victoria’s goddaughter and led an opulent life and attended every social party. Eventually, she and her sisters returned to India, where they bore witness to the harsh realities of poverty and racism. She was a celebrity in London, but there she was just another brown face. Upon return, she threw herself into the suffrage cause, slamming into Parliamentarians and demanding female suffrage. She was eventually taken to court over her refusal to pay taxes.

In 1909, a Conciliation Bill was proposed to give women who owned a certain amount of property the right to vote, but the bill failed. In response, Pankhurst and Singh led 300 women to march on Parliament where they were met with police brutality in an event known as Bloody Friday.

Still women did not back down. Militancy peaked in 1912 with more window smashing and arson attacks. Then in 1913, Emily Wilding Davison attended the Epsom Derby where the King was racing. She stepped out onto the track with a suffrage banner as he raced by. His horse trampled her, creating a martyr for the suffrage cause. Thousands of suffrage sympathizers attended her funeral.

World War I disrupted women's suffrage activities. Eventually, Nancy Astor became the first female MP, Women took hold of power. Finally in 1928, women in the UK won the right to vote.

Women around the world were awed by the achievements of the New Zealand, Australian, American, and British women. Slowly, most countries followed suit, especially after World War II, but in some authoritarian places today ,women remain disenfranchised. The vote didn’t transform everything. In fact many of the gendered expectations of women remained for decades and remain today. One could argue that the vote did little without changing the structures that deny women equal opportunity to hold power.

In 1909, a Conciliation Bill was proposed to give women who owned a certain amount of property the right to vote, but the bill failed. In response, Pankhurst and Singh led 300 women to march on Parliament where they were met with police brutality in an event known as Bloody Friday.

Still women did not back down. Militancy peaked in 1912 with more window smashing and arson attacks. Then in 1913, Emily Wilding Davison attended the Epsom Derby where the King was racing. She stepped out onto the track with a suffrage banner as he raced by. His horse trampled her, creating a martyr for the suffrage cause. Thousands of suffrage sympathizers attended her funeral.

World War I disrupted women's suffrage activities. Eventually, Nancy Astor became the first female MP, Women took hold of power. Finally in 1928, women in the UK won the right to vote.

Women around the world were awed by the achievements of the New Zealand, Australian, American, and British women. Slowly, most countries followed suit, especially after World War II, but in some authoritarian places today ,women remain disenfranchised. The vote didn’t transform everything. In fact many of the gendered expectations of women remained for decades and remain today. One could argue that the vote did little without changing the structures that deny women equal opportunity to hold power.

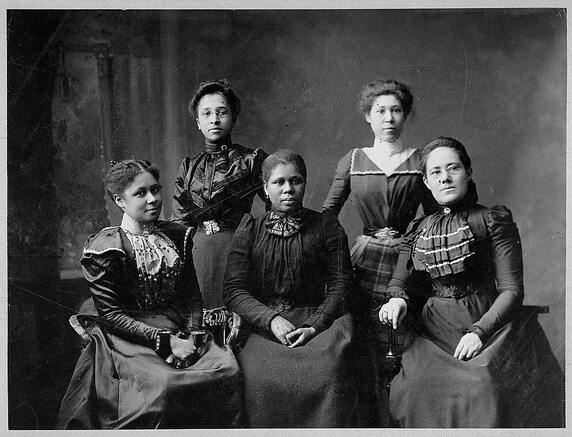

Black Women's Club, Wikimedia Commons

Black Women's Club, Wikimedia Commons

Conclusion

Industrialization improved women’s lives, perhaps more than it did men’s. Urbanization led to somewhat better medical care in pregnancy (especially after germs were better understood). Women and men in industrial work did better economically than their agrarian peers and the standard of living increased considerably. Despite low wages, some women did find means of supporting themselves, and a few even acquired considerable wealth.

Women also became consumers, and with that new role came great power to influence production. Industrialization also upended the patriarchal norms in some ways because it challenged the idea of a “male provider,” as it was increasingly obvious that more and more women needed to work to make ends meet.

Industrialization fueled western imperial expansion. Factories could produce more weapons, fueling military conquests in Africa, Asia, Siberia, the Pacific islands, and the western Americas. Whether in positions of leadership or in missionary efforts, women supported imperialism and fought against it.

Industrialization changed the global make-up, shifted power structures, and allowed the Global North to impose its systems on others, including their views of women.

By the end of this era, so much remained in question. How did class and region change the effects of industrialization? Did the benefits of industrialization outweigh the costs? How would women’s role in the labor force influence policy and social change? Would women be able to enter industries considered “male”? How would society adapt to allow for women to be wage earners and mothers? What would it take for women to earn the vote?

Industrialization improved women’s lives, perhaps more than it did men’s. Urbanization led to somewhat better medical care in pregnancy (especially after germs were better understood). Women and men in industrial work did better economically than their agrarian peers and the standard of living increased considerably. Despite low wages, some women did find means of supporting themselves, and a few even acquired considerable wealth.

Women also became consumers, and with that new role came great power to influence production. Industrialization also upended the patriarchal norms in some ways because it challenged the idea of a “male provider,” as it was increasingly obvious that more and more women needed to work to make ends meet.

Industrialization fueled western imperial expansion. Factories could produce more weapons, fueling military conquests in Africa, Asia, Siberia, the Pacific islands, and the western Americas. Whether in positions of leadership or in missionary efforts, women supported imperialism and fought against it.

Industrialization changed the global make-up, shifted power structures, and allowed the Global North to impose its systems on others, including their views of women.

By the end of this era, so much remained in question. How did class and region change the effects of industrialization? Did the benefits of industrialization outweigh the costs? How would women’s role in the labor force influence policy and social change? Would women be able to enter industries considered “male”? How would society adapt to allow for women to be wage earners and mothers? What would it take for women to earn the vote?

Draw your own conclusions

|

Learn how to teach with inquiry.

Many of these lesson plans were sponsored in part by the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources Eastern Region Program, coordinated by Waynesburg University, the History and Social Studies Education Faculty at Plymouth State University, and the Patrons of the Remedial Herstory Project. |

|

OTHER: Cottage Industries

In this inquiry from Women in World History, students examine primary material from women across the globe to better understand the Industrial Revolution's impact on women. Check it out! |

Lesson Plans from Other Organizations

- This website, Women in World History has primary source based lesson plans on women's history in a whole range of topics. Some are free while others have a cost.

- The Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media has produced recommendations for teaching women's history with primary sources and provided a collection of sources for world history. Check them out!

- The Stanford History Education Group has a number of lesson plans about women in World History.

Hannah Goode: Excerpt

"I work at Mr. Wilson's mill. I think the youngest child is about 7. I daresay there are 20 under 9 years. It is about half past five by our clock at home when we go in....We come out at seven by the mill. We never stop to take our meals, except at dinner.

William Crookes is overlooker in our room. He is cross-tempered sometimes. He does not beat me; he beats the little children if they do not do their work right....I have sometimes seen the little children drop asleep or so, but not lately. If they are catched asleep they get the strap. They are always very tired at night....I can read a little; I can't write. I used to go to school before I went to the mill; I have since I am sixteen."

Factory Inquiry Commission, Great Britain, Parliamentary Papers, 1833. Found in Hellerstein, Hume & Offen, Victorian Women: A Documentary Accounts of Women's Lives in Nineteenth-Century England, France and the United States, Stanford University Press

Questions:

William Crookes is overlooker in our room. He is cross-tempered sometimes. He does not beat me; he beats the little children if they do not do their work right....I have sometimes seen the little children drop asleep or so, but not lately. If they are catched asleep they get the strap. They are always very tired at night....I can read a little; I can't write. I used to go to school before I went to the mill; I have since I am sixteen."

Factory Inquiry Commission, Great Britain, Parliamentary Papers, 1833. Found in Hellerstein, Hume & Offen, Victorian Women: A Documentary Accounts of Women's Lives in Nineteenth-Century England, France and the United States, Stanford University Press

Questions:

- What do you think happened to younger children when the family was away at work in

mills? - What might be different about work done at home compared to work in the factory?

- Why did some workers oppose the imposition of laws restricting women and children's work?

- Today women are the majority of workers in textile and electronics industries around the world. What reasons do you think are given for employing mainly women? Does the problem of women's work being a "dead end" job exist in these plants too?

Mrs. Smith: Excerpt

"I have three children working in Wilson's mill; one 11, one 13, and the other 14. They work regular hours there. We don't complain. If they go to drop the hours, I don't know what poor people will do. We have hard work to live as it is. ...My husband is of the same mind about it...last summer my husband was 6 weeks ill; we pledged almost all our things to live; the things are not all out of pawn yet. ...We complain of nothing but short wages...My children have been in the mill three years. I have no complaint to make of their being beaten...I would rather they were beaten than fined."

Factory Inquiry Commission, Great Britain, Parliamentary Papers, 1833. Found in Hellerstein, Hume & Offen, Victorian Women: A Documentary Accounts of Women's Lives in Nineteenth-Century England, France and the United States, Stanford University Press

Questions:

Factory Inquiry Commission, Great Britain, Parliamentary Papers, 1833. Found in Hellerstein, Hume & Offen, Victorian Women: A Documentary Accounts of Women's Lives in Nineteenth-Century England, France and the United States, Stanford University Press

Questions:

- What do you think happened to younger children when the family was away at work in

mills? - What might be different about work done at home compared to work in the factory?

- Why did some workers oppose the imposition of laws restricting women and children's work?

- Today women are the majority of workers in textile and electronics industries around the world. What reasons do you think are given for employing mainly women? Does the problem of women's work being a "dead end" job exist in these plants too?

A 6-year-old girl: Testimonies in the South Wales Mines

"I have been down six weeks and make 10 to 14 rakes a day; I carry a full 56 lbs. of coal in a wooden bucket. I work with sister Jesse and mother. It is dark the time we go."

Children Working Underground Amgueddfa Genedlaethol Cymru National Museum of Wales, 1979.

Questions:

Children Working Underground Amgueddfa Genedlaethol Cymru National Museum of Wales, 1979.

Questions:

- How were children treated in the mines?

Jane Peacock Watson: In the South Wales Mines

"I have wrought in the bowels of the earth 33 years. I have been married 23 years and had nine children, six are alive and three died of typhus a few years since. Have had two dead born. Horse-work ruins the women; it crushes their haunches, bends their ankles and makes them old women at 40."

Children Working Underground Amgueddfa Genedlaethol Cymru National Museum of Wales, 1979.

Questions:

Children Working Underground Amgueddfa Genedlaethol Cymru National Museum of Wales, 1979.

Questions:

- Describe the quality of life.

Maria Gooder: in the South Wales Mines

"I hurry for a man with my sister Anne who is going 18. He is good to us. I don't like being in the pit. I am tired and afraid. I go at 4:30 after having porridge for breakfast. I start hurrying at 5. We have dinner at noon. We have dry bread and nothing else. There is water in the pit but we don't sup it."

Children Working Underground Amgueddfa Genedlaethol Cymru National Museum of Wales, 1979.

Questions:

Children Working Underground Amgueddfa Genedlaethol Cymru National Museum of Wales, 1979.

Questions:

- Generally how many hours did women work in the mines?

Mary (11) and Rachell Enock (12): in the South Wales Mines

“We are door-keepers in the four foot level. We leave the house before six each morning and are in the level until seven o’clock and sometimes later. We get 2p a day and our light costs us 2 1⁄2 p. a week. Rachel was in a day school and she can read a little. She was run over by a tram a while ago and was home ill a long time, but she has got over it.”

Children Working Underground Amgueddfa Genedlaethol Cymru National Museum of Wales, 1979.

Questions:

Children Working Underground Amgueddfa Genedlaethol Cymru National Museum of Wales, 1979.

Questions:

- How would this affect the family?

Isabel Wilson (38): In the South Wales Mines

"I have been married 19 years and have had 10 bairns [children]:...My last child was born on Saturday morning, and I was at work on the Friday night... None of the children read, as the work is no regular..When I go below my lassie 10 years of age keeps house..."

Children Working Underground Amgueddfa Genedlaethol Cymru National Museum of Wales, 1979.

Questions:

Children Working Underground Amgueddfa Genedlaethol Cymru National Museum of Wales, 1979.

Questions:

- Some ways that this type of work affected family life.

Children's Employment Commission: Excerpt

"Miss --- has been for several years in the dress-making business...The common hours of business are from 8 a.m. til 11 P.M in the winters; in the summer from 6 or half-past 6 A.M. til 12 at night. During the fashionable season, that is from April til the latter end of July, it frequently happens that the ordinary hours are greatly exceeded; if there is a drawing-room or grand fete, or mourning to be made, it often happens that the work goes on for 20 hours out of the 24, occasionally all night....The general result of the long hours and sedentary occupation is to impair seriously and very frequently to destroy the health of the young women. The digestion especially suffers, and also the lungs: pain to the side is very common, and the hands and feet die away from want of circulation and exercise, "never seeing the outside of the door from Sunday to Sunday." [One cause] is the short time which is allowed by ladies to have their dresses made.

“Miss is sure that there are some thousands of young women employed in the business in London and in the country. If one vacancy were to occur now there would be 20 applicants for it. The wages generally are very low...Thinks that no men could endure the work enforced from the dress-makers."

Hellerstein, Hume & Offen, Victorian Women: A Documentary Accounts of Women's Lives in Nineteenth-Century England, France and the United States, Stanford University Press.

Questions:

“Miss is sure that there are some thousands of young women employed in the business in London and in the country. If one vacancy were to occur now there would be 20 applicants for it. The wages generally are very low...Thinks that no men could endure the work enforced from the dress-makers."

Hellerstein, Hume & Offen, Victorian Women: A Documentary Accounts of Women's Lives in Nineteenth-Century England, France and the United States, Stanford University Press.

Questions:

- Why do you think young girls wanted to become seamstresses?

- What health problems occurred with this type of work?

- Imagine the types of clothing and the life of the Victorian era middle and upper class woman. How was this job in sharp contrast to the life of other working class women?

Unknown: The Distressed Seamstress Song

(Sung to the air "Jenny Jones")

You gentles of England, I pray give attention,

Unto those few lines, I'm going to relate, Concerning the seamstress,I'm going to mention, Who long time has been, in a sad wretched state, Laboriously toiling, both night, noon, and morning, For a wretched subsistence, now mark what I say. She's quite unprotected, forlorn, and dejected

For sixpence, or eightpence, or tenpence a day. Come forward you nobles, and grant them assistance, Give them employ, and a fair price them pay,

And then you will find, the poor hard working seamstress, From honour and virtue will not go astray.

To shew them compassion pray quickly be stirring,

In delay, there is danger, there's no time to spare,... The pride of the world is o'er whelmed with care,

Old England's considered, for honour and virtue, And beauty the glory and pride of the world,

Nor be not hesitating, but boldly step forward, Suppression and tyranny, far away hurl.

Roy Palmer, A Ballad History of England: From 1588 to the Present Day, B.T. Batsford Ltd, London, 1979

Questions:

You gentles of England, I pray give attention,

Unto those few lines, I'm going to relate, Concerning the seamstress,I'm going to mention, Who long time has been, in a sad wretched state, Laboriously toiling, both night, noon, and morning, For a wretched subsistence, now mark what I say. She's quite unprotected, forlorn, and dejected

For sixpence, or eightpence, or tenpence a day. Come forward you nobles, and grant them assistance, Give them employ, and a fair price them pay,

And then you will find, the poor hard working seamstress, From honour and virtue will not go astray.

To shew them compassion pray quickly be stirring,

In delay, there is danger, there's no time to spare,... The pride of the world is o'er whelmed with care,

Old England's considered, for honour and virtue, And beauty the glory and pride of the world,

Nor be not hesitating, but boldly step forward, Suppression and tyranny, far away hurl.

Roy Palmer, A Ballad History of England: From 1588 to the Present Day, B.T. Batsford Ltd, London, 1979

Questions:

- To whom was the song directed?

- What societal concerns about the "distressed seamstress" did the song reveal?

- What appeals did it use to convey its message?

- If you were writing a song which addressed the plight of the seamstress, what reasons for hiring and giving girls a decent wage might you include?

Remedial Herstory Editors. "24. 1850-1950 WOMEN’S INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION." The Remedial Herstory Project. November 1, 2022. www.remedialherstory.com.

Primary AUTHOR: |

Kelsie Brook Eckert

|

Primary Reviewer: |

Jacqui Nelson

|

Consulting Team |

Editors |

|

Kelsie Brook Eckert, Project Director

Coordinator of Social Studies Education at Plymouth State University Dr. Nancy Locklin-Sofer, Consultant Professor of History at Maryville College. Chloe Gardner, Consultant PhD Candidate in Religious Studies at Edinburgh University Dr. Whitney Howarth, Consultant Former Professor of History at Plymouth State University Jacqui Nelson, Consultant Teaching Lecturer of Military History at Plymouth State University Maria Concepcion Marquez Sandoval PhD Candidate in History at Arizona University |

Amy Flanders

Humanities Teacher, Moultonborough Academy ReviewersAncient:

Dr. Kristin Heineman Professor of History at Colorado State University Dr. Bonnie Rock-McCutcheon Professor of History at Wilson College Sarah Stone PhD Candidate in Religious Studies at Edinburgh University Medieval: Dr. Katherine Koh Professor of History at La Sierra University Dr. Jonathan Couser Professor of History at Plymouth State University Dr. Shahla Haeri Professor of History at Boston University Lauren Cole PhD Candidate in History at Northwestern University Modern: Dr. Barbara Tischler Supervisor for Hunter College Dr. Pamela Scully Professor of Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies and African Studies at Emory University |

|

From the mid-18th century, new machines powered by steam and coal began to produce goods on a massive scale. This was known as the Industrial Revolution. Workers were poorly paid and their working conditions were harsh. Life was even harder for working women, who received lower wages and fewer rights than men. Some women, however, would not stand for the poor treatment of themselves or others. These are the stories of four trailblazers who achieved amazing things in difficult circumstances.

This book charts the unhappy but aspirational story of women and children at work through the Industrial Revolution to the beginning of the 20th century. Without women there would have been no pre-industrial cottage industries, without women the Industrial Revolution would not have been nearly as industrial and nowhere near as revolutionary.

Recording the important milestones in the birth of the modern feminist movement and the rise of women into greater social, economic, and political power, Miles takes us through through a colorful pageant of astonishing women

Jenni Murray presents the history of Britain as you’ve never seen it before, through the lives of twenty-one women who refused to succumb to the established laws of society, whose lives embodied hope and change, and who still have the power to inspire us today..

|

|

|

In June 1917, General John Pershing arrived in France to establish American forces in Europe. He immediately found himself unable to communicate with troops in the field. Pershing needed telephone operators who could swiftly and accurately connect multiple calls, speak fluent French and English, remain steady under fire, and be utterly discreet, since the calls often conveyed classified information. At the time, nearly all well-trained American telephone operators were women—but women were not permitted to enlist, or even to vote in most states. Nevertheless, the U.S. Army Signal Corps promptly began recruiting them. They were among the first women sworn into the U.S. Army under the Articles of War. The male soldiers they had replaced had needed one minute to connect each call. The switchboard soldiers could do it in ten seconds. Deployed throughout France, including near the front lines, the operators endured hardships and risked death or injury from gunfire, bombardments, and the Spanish Flu. Not all of them would survive. The women of the U.S. Army Signal Corps served with honor and played an essential role in achieving the Allied victory. Their story has never been the focus of a novel…until now.

|

|

How to teach with film:

Remember, teachers want the student to be the historian. What do historians do when they watch films?

- Before they watch, ask students to research the director and producers. These are the source of the information. How will their background and experience likely bias this film?

- Also, ask students to consider the context the film was created in. The film may be about history, but it was made recently. What was going on the year the film was made that could bias the film? In particular, how do you think the gains of feminism will impact the portrayal of the female characters?

- As they watch, ask students to research the historical accuracy of the film. What do online sources say about what the film gets right or wrong?

- Afterward, ask students to describe how the female characters were portrayed and what lessons they got from the film.

- Then, ask students to evaluate this film as a learning tool. Was it helpful to better understand this topic? Did the historical inaccuracies make it unhelpful? Make it clear any informed opinion is valid.

|

Suffragette tells the stories of English women who grappled with a way to have their voices heard in the early movement.

IMDB |

|

|

Albert Nobbs is a film about the life of a poor woman living in 19th century Ireland who cross dresses in order to improve her station.

IMDB |

|

|

The Woman King is a film about the Dahomey "Amazons," women warriors who fought European imperialism in West Africa.

IMDB |

|

bibliography

Adams, Carol, Paula Bartley, Judy Lown, and Cathy Loxton. Under Control: Life in a nineteenth-century Silk Factory, Cambridge University Press.

British Library Editors, “Women's Suffrage Timeline.” British Library. N.D. https://www.bl.uk/votes-for-women/articles/womens-suffrage-timeline.

Children Working Underground Amgueddfa Genedlaethol Cymru National Museum of Wales, 1979.

ENGEL, BARBARA ALPERN. “WOMEN, WORK AND FAMILY IN THE FACTORIES OF RURAL RUSSIA.” Russian History 16, no. 2/4 (1989): 223–37. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24656506.

Factory Inquiry Commission, Great Britain, Parliamentary Papers, 1833. Found in Hellerstein, Hume & Offen, Victorian Women: A Documentary Accounts of Women's Lives in Nineteenth-Century England, France and the United States, Stanford University Press.

Gillard, Julia. “A global story: Women’s suffrage, forgotten history, and a way forward.” Brookings Institute. September 2020. https://www.brookings.edu/essay/a-global-story/.

Jackson S, Ho PSY. Interconnected Histories: Locating Women’s Lives in Time and Space. Women Doing Intimacy. 2020 Jun 12:47–86. doi: 10.1057/978-1-137-28991-9_3. PMCID: PMC7286840.

Reese, Lyn. “WOMEN’S WORK IN INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTIONS PRIMARY SOURCE LESSONS FROM EUROPE & EAST ASIA,” Women in World History Curriculum, 2005.

Strayer, R. and Nelson, E., Ways Of The World. 3rd ed. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2016.

British Library Editors, “Women's Suffrage Timeline.” British Library. N.D. https://www.bl.uk/votes-for-women/articles/womens-suffrage-timeline.

Children Working Underground Amgueddfa Genedlaethol Cymru National Museum of Wales, 1979.

ENGEL, BARBARA ALPERN. “WOMEN, WORK AND FAMILY IN THE FACTORIES OF RURAL RUSSIA.” Russian History 16, no. 2/4 (1989): 223–37. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24656506.

Factory Inquiry Commission, Great Britain, Parliamentary Papers, 1833. Found in Hellerstein, Hume & Offen, Victorian Women: A Documentary Accounts of Women's Lives in Nineteenth-Century England, France and the United States, Stanford University Press.

Gillard, Julia. “A global story: Women’s suffrage, forgotten history, and a way forward.” Brookings Institute. September 2020. https://www.brookings.edu/essay/a-global-story/.

Jackson S, Ho PSY. Interconnected Histories: Locating Women’s Lives in Time and Space. Women Doing Intimacy. 2020 Jun 12:47–86. doi: 10.1057/978-1-137-28991-9_3. PMCID: PMC7286840.

Reese, Lyn. “WOMEN’S WORK IN INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTIONS PRIMARY SOURCE LESSONS FROM EUROPE & EAST ASIA,” Women in World History Curriculum, 2005.

Strayer, R. and Nelson, E., Ways Of The World. 3rd ed. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2016.