23. Reproductive Freedom

|

Reproductive Freedom, or the rights to control your reproduction, came under attack by laws in the late 19th century. As soon as women gained political freedoms, they began attacking these restrictions in the 20th century, with advocacy efforts peaking in the 1960s. Rights to privacy, rights to contraception (birth control), and rights to abortion were all focal points for women and their allies.

Trigger warning: this section discusses rape and abortion. |

After women won the vote, many battles for women’s rights remained–especially in the area of reproductive rights which uniquely affected women, and had yet to be addressed by either Congress or almost all-male state legislatures.

While reproduction may seem awkward to talk about, it has been one of the most significant and defining facets of women’s lives throughout history. In the 20th century women pushed back against the laws of the late 19th century to expand their options and choices related to having children. This included birth control, access to abortion, maternity leave and child care. All of these efforts expanded women’s ability to join the workforce in greater numbers, but it was an uphill battle that took decades. Women had to fight against social norms, expected gender roles, and stigmas to redefine womanhood and femininity, to get a seat at the table where decisions were being made.

Forewarning, this section is going to discuss some difficult topics including rape, abortion, illegal abortion, and fetal abnormalities.

While reproduction may seem awkward to talk about, it has been one of the most significant and defining facets of women’s lives throughout history. In the 20th century women pushed back against the laws of the late 19th century to expand their options and choices related to having children. This included birth control, access to abortion, maternity leave and child care. All of these efforts expanded women’s ability to join the workforce in greater numbers, but it was an uphill battle that took decades. Women had to fight against social norms, expected gender roles, and stigmas to redefine womanhood and femininity, to get a seat at the table where decisions were being made.

Forewarning, this section is going to discuss some difficult topics including rape, abortion, illegal abortion, and fetal abnormalities.

19th Century Male Doctor, Public Domain

19th Century Male Doctor, Public Domain

Background:

Because of the way society is structured, and because most laws are written to protect lawmakers’ interests, few laws protected women and mothers. In marriage, women had some protections under laws that ensured the father would provide for his children, but outside of marriage women had little options. It wasn’t until 1950 that Wisconsin became the first state to enact a formal child support law, which required fathers to provide financial support for their children. Even today, while child support laws are common, fathers are not required to provide support for pregnant mothers or help with hospital bills. Following Wisconsin, other states gradually implemented their own child support laws, but since this was before reliable paternity tests, it was difficult to prove men were in fact the father.

The Patriarchal system, a system in which elite men hold the power and poor men and most women are largely excluded from it, caused married women to almost disappear in marriage. Married women could not open bank accounts without their husbands signature until 1974 and women were listed not by their own name, but as their husband’s wife, on their passports. In the workforce, women still made fractions of what men made and there were little-to-no protections for women if they got pregnant. Men on the other hand could have sex, not acknowledge the pregnancy, support the woman during the pregnancy and birth, and fail to provide for the child on the other end, leaving the risks and expense of childbirth and childrearing on women.

Divorce was often harder for women to acquire. Established laws gave men more choice over when they could divorce, and traditionally, women financially relied on men for support, so divorce was often detrimental to a woman’s financial situation. Common reasons for divorce included adultery, abandonment, and cruelty, but proving these grounds was often challenging for women. Additionally, divorce proceedings could be costly, time-consuming, and required significant evidence and witnesses. Some states introduced laws that allowed women to petition for divorce on grounds of desertion or extreme cruelty. However, even with these provisions, women often faced significant legal and societal obstacles when seeking divorce. Furthermore, divorce often carried social stigmas and financial implications for women. In many cases, divorced women were at a disadvantage in terms of property rights, child custody, and financial support. It wasn’t until the 1970s that “no-fault divorce” became more common

These vestiges, or hold outs, from the 19th century made women dependant on men to provide for them and their children. Moral and social conventions dictated that women not engage in sex before marriage. Marriage provided a woman with financial stability–theoretically–and provided a man with social status and sexual access. Once in a marriage, however, there were few options for women to leave, there were repercussions for her socially and economically if she did. If a woman became pregnant out of wedlock–her refusal to adhere to social and moral conventions meant that the father of the child was not obligated to provide for her or their child. It all created a system and structure wherein women were punished or denied protections if they stepped out of line.

Women in this period worked to change the laws that would make them better able to provide for their children without men, but they also looked at the root cause of the problem: sex. If women could increase their control over when they got pregnant or if they carried their pregnancy to term, then they could be more equal in society. This concept of control over your body is called “Reproductive Freedom.” Reproductive Freedom can’t exist where a woman has no ability to control what happens to her body. This is deeply important, especially for women where pregnancy carries health risks like high blood pressure, preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, genetic birth defects, and more.

Those are the challenges faced by women who have consensual sex, meaning they agreed to have sex. There are sadly also cases where people are coerced and forced into sexual acts. This is called rape. In the early 20th century, especially for Black women, rape was common, because again, the entire social and legal landscape was built to protect men. Today, one in four women have experienced attempted or completed rape.

For women of color, sexual abuse was a holdover from the culture of slavery in the south. Enslaved women in the US were “owned” by men who claimed access to their bodies and to any children born of sexual encounters between master and slave. Enslaved mothers had no choice over whether they had sex with the master and no rights to her children after they were born. In the decades after slavery, the southern rape culture persisted.

Reproductive Freedom is important for women when all the scales of the system are tipped to favor men. It protects women and ensures their children are raised in supportive environments.

Women in Developmental Biology:

Many actors on both sides of the struggle for reproductive justice – politicians, activists and religious leaders – make scientific claims to justify their positions. Interestingly, the field of developmental biology (that is, the study of how animals and plants grow and develop) has been well-populated with women since WWII. Even before then it was Nettie Stevens (1861-1912) who identified how X and Y chromosomes were responsible for sex-determination by studying mealworms. In the 1920s and 1930s, women were also more represented in the field of embryology (the study of embryos) for a number of potential reasons: it often involved slow-moving fieldwork over several years that appealed less to publication-oriented male professional and it involved a high degree of fine motor skills that were encouraged in women doing needlework.

The founder of developmental genetics, Salome Gluecksohn-Waelsch was born in Danzig, Germany in 1907 and earned her doctorate from the University of Freiburg in 1932–studying the development of salamander embryos. In 1933, she and her husband escaped Nazi Germany for New York City. She was just one of hundreds of Jewish scientists to flee Germany on the eve of WWII. In America she joined Columbia University as a “research associate.” In that role she was able to publish a number of papers that made clear the connection between genetics and embryo development, a novel contribution that established the field of developmental genetics.

These scientists worked together to promote the cause of fellow women scientists. Jane Marion Oppenheimer (1911-1996) was a friend of Waelsch and a professor of biology and the history of science at Bryn Mawr College. She was an embryologist whose experimental work focused on the embryo of the common minnow. In addition to her own rich career on regulation and differentiation in embryos, Oppenheimer supported her colleague by singing the praises of Waelsch’s work to Ernst Scharrer, who was hiring for the newly founded Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York. He ended up hiring Waelsch, finally giving her a full faculty position.

However, the most famous embryologist is probably Christiane Nüsslein-Volhard, who won the 1995 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for her work on how the genes in a fertilized egg form an embryo. Born in Germany in the middle of WWII, she studied biology, physics, and biochemistry, eventually earning her Ph.D. through her dissertation work on genetics. She became interested in how genes controlled the development of embryos. She and her colleague, Eric Wieschaus, worked with fruit flies and determined how the shape of fly embryos was determined by a small number of genes. While these women have worked to unlock the mysteries of how life is formed and developed, they can shed little light on the moral questions that are debated around reproductive rights. Those discussions take place not in the lab, but in households and the halls of power.

Because of the way society is structured, and because most laws are written to protect lawmakers’ interests, few laws protected women and mothers. In marriage, women had some protections under laws that ensured the father would provide for his children, but outside of marriage women had little options. It wasn’t until 1950 that Wisconsin became the first state to enact a formal child support law, which required fathers to provide financial support for their children. Even today, while child support laws are common, fathers are not required to provide support for pregnant mothers or help with hospital bills. Following Wisconsin, other states gradually implemented their own child support laws, but since this was before reliable paternity tests, it was difficult to prove men were in fact the father.

The Patriarchal system, a system in which elite men hold the power and poor men and most women are largely excluded from it, caused married women to almost disappear in marriage. Married women could not open bank accounts without their husbands signature until 1974 and women were listed not by their own name, but as their husband’s wife, on their passports. In the workforce, women still made fractions of what men made and there were little-to-no protections for women if they got pregnant. Men on the other hand could have sex, not acknowledge the pregnancy, support the woman during the pregnancy and birth, and fail to provide for the child on the other end, leaving the risks and expense of childbirth and childrearing on women.

Divorce was often harder for women to acquire. Established laws gave men more choice over when they could divorce, and traditionally, women financially relied on men for support, so divorce was often detrimental to a woman’s financial situation. Common reasons for divorce included adultery, abandonment, and cruelty, but proving these grounds was often challenging for women. Additionally, divorce proceedings could be costly, time-consuming, and required significant evidence and witnesses. Some states introduced laws that allowed women to petition for divorce on grounds of desertion or extreme cruelty. However, even with these provisions, women often faced significant legal and societal obstacles when seeking divorce. Furthermore, divorce often carried social stigmas and financial implications for women. In many cases, divorced women were at a disadvantage in terms of property rights, child custody, and financial support. It wasn’t until the 1970s that “no-fault divorce” became more common

These vestiges, or hold outs, from the 19th century made women dependant on men to provide for them and their children. Moral and social conventions dictated that women not engage in sex before marriage. Marriage provided a woman with financial stability–theoretically–and provided a man with social status and sexual access. Once in a marriage, however, there were few options for women to leave, there were repercussions for her socially and economically if she did. If a woman became pregnant out of wedlock–her refusal to adhere to social and moral conventions meant that the father of the child was not obligated to provide for her or their child. It all created a system and structure wherein women were punished or denied protections if they stepped out of line.

Women in this period worked to change the laws that would make them better able to provide for their children without men, but they also looked at the root cause of the problem: sex. If women could increase their control over when they got pregnant or if they carried their pregnancy to term, then they could be more equal in society. This concept of control over your body is called “Reproductive Freedom.” Reproductive Freedom can’t exist where a woman has no ability to control what happens to her body. This is deeply important, especially for women where pregnancy carries health risks like high blood pressure, preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, genetic birth defects, and more.

Those are the challenges faced by women who have consensual sex, meaning they agreed to have sex. There are sadly also cases where people are coerced and forced into sexual acts. This is called rape. In the early 20th century, especially for Black women, rape was common, because again, the entire social and legal landscape was built to protect men. Today, one in four women have experienced attempted or completed rape.

For women of color, sexual abuse was a holdover from the culture of slavery in the south. Enslaved women in the US were “owned” by men who claimed access to their bodies and to any children born of sexual encounters between master and slave. Enslaved mothers had no choice over whether they had sex with the master and no rights to her children after they were born. In the decades after slavery, the southern rape culture persisted.

Reproductive Freedom is important for women when all the scales of the system are tipped to favor men. It protects women and ensures their children are raised in supportive environments.

Women in Developmental Biology:

Many actors on both sides of the struggle for reproductive justice – politicians, activists and religious leaders – make scientific claims to justify their positions. Interestingly, the field of developmental biology (that is, the study of how animals and plants grow and develop) has been well-populated with women since WWII. Even before then it was Nettie Stevens (1861-1912) who identified how X and Y chromosomes were responsible for sex-determination by studying mealworms. In the 1920s and 1930s, women were also more represented in the field of embryology (the study of embryos) for a number of potential reasons: it often involved slow-moving fieldwork over several years that appealed less to publication-oriented male professional and it involved a high degree of fine motor skills that were encouraged in women doing needlework.

The founder of developmental genetics, Salome Gluecksohn-Waelsch was born in Danzig, Germany in 1907 and earned her doctorate from the University of Freiburg in 1932–studying the development of salamander embryos. In 1933, she and her husband escaped Nazi Germany for New York City. She was just one of hundreds of Jewish scientists to flee Germany on the eve of WWII. In America she joined Columbia University as a “research associate.” In that role she was able to publish a number of papers that made clear the connection between genetics and embryo development, a novel contribution that established the field of developmental genetics.

These scientists worked together to promote the cause of fellow women scientists. Jane Marion Oppenheimer (1911-1996) was a friend of Waelsch and a professor of biology and the history of science at Bryn Mawr College. She was an embryologist whose experimental work focused on the embryo of the common minnow. In addition to her own rich career on regulation and differentiation in embryos, Oppenheimer supported her colleague by singing the praises of Waelsch’s work to Ernst Scharrer, who was hiring for the newly founded Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York. He ended up hiring Waelsch, finally giving her a full faculty position.

However, the most famous embryologist is probably Christiane Nüsslein-Volhard, who won the 1995 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for her work on how the genes in a fertilized egg form an embryo. Born in Germany in the middle of WWII, she studied biology, physics, and biochemistry, eventually earning her Ph.D. through her dissertation work on genetics. She became interested in how genes controlled the development of embryos. She and her colleague, Eric Wieschaus, worked with fruit flies and determined how the shape of fly embryos was determined by a small number of genes. While these women have worked to unlock the mysteries of how life is formed and developed, they can shed little light on the moral questions that are debated around reproductive rights. Those discussions take place not in the lab, but in households and the halls of power.

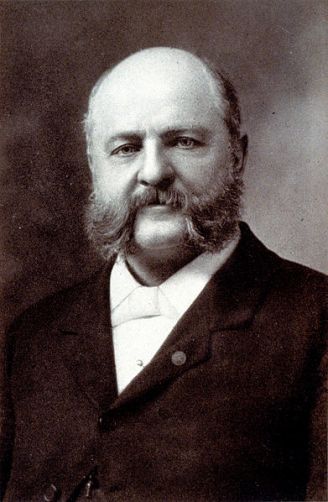

Anthony Comstock, Public Domain

Anthony Comstock, Public Domain

Comstock Laws:

So what does Reproductive Freedom look like? Most advocates agree that it includes things like the freedom to have sex or not when one chooses, the freedom to contraception (birth control) and access to it, the right to abortion and access to it, the right to parental leave to keep your job while you birth and raise an infant in its early months, access to affordable childcare, and tax breaks for single parents among other things. These of course were the battles fought during the late 19th century and through today.

The biggest barrier to women’s reproductive freedoms were laws passed by men in the 19th century. It’s important to note that these laws were not in practice during the founding of the US, but added later. The laws started with the formation of the American Medical Association (AMA) in 1847. Male doctors banded together to delegitimize the mostly female midwives who were competing for services with them. Over time, the midwives’ practices disappeared in favor of male doctors. Despite having little experience or exposure to pregnancy and birth practices, these doctors assumed that their medical degrees afforded them greater expertise in the field of women’s health and childbirth.

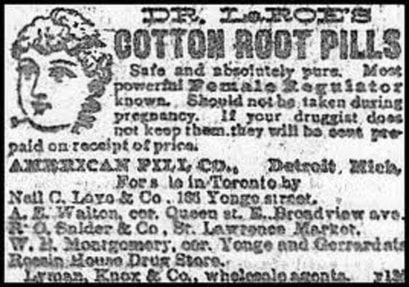

The most important of these oppressive laws were the Comstock Laws. The Comstock Laws were a series of federal acts in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. These laws were named after their chief architect, Anthony Comstock, a zealous advocate against what he saw as “vices.” Comstock succeeded in passing the first of these laws in 1873. They were designed to prohibit and regulate the distribution of materials deemed to be obscene, immoral, or indecent, particularly related to contraception and information about birth control. Birth control is a broad term used to describe devices or chemicals that could help prevent pregnancy. They include all forms of condoms, hormones, implantable devices in the vagina, and sterilization. People like Comstock believed that birth control would cause people to have riskier sex because the threat of pregnancy would be removed. Many religious people also believed that sex should be reserved solely for the purpose of reproduction.

Under the Comstock Laws, it was illegal to send through the mail any materials, including books, pamphlets, and contraceptives, that were considered obscene or lewd. The laws also targeted the distribution of information about abortion and contraception, making it punishable by imprisonment or fines.

Because men were the doctors, the lawyers, and the government officials, women had little say in the passage of these laws. Even today women make up a small minority in all of those professions.

Women of the late 19th century didn’t take these laws sitting down. Emma Goldman, for example, was an influential political activist and writer, born in 1869 in the Russian Empire (now Lithuania) and later emigrated to the United States. She played a prominent role in various social and political movements, advocating for women's rights, workers' rights, free speech, and anarchism.

So what does Reproductive Freedom look like? Most advocates agree that it includes things like the freedom to have sex or not when one chooses, the freedom to contraception (birth control) and access to it, the right to abortion and access to it, the right to parental leave to keep your job while you birth and raise an infant in its early months, access to affordable childcare, and tax breaks for single parents among other things. These of course were the battles fought during the late 19th century and through today.

The biggest barrier to women’s reproductive freedoms were laws passed by men in the 19th century. It’s important to note that these laws were not in practice during the founding of the US, but added later. The laws started with the formation of the American Medical Association (AMA) in 1847. Male doctors banded together to delegitimize the mostly female midwives who were competing for services with them. Over time, the midwives’ practices disappeared in favor of male doctors. Despite having little experience or exposure to pregnancy and birth practices, these doctors assumed that their medical degrees afforded them greater expertise in the field of women’s health and childbirth.

The most important of these oppressive laws were the Comstock Laws. The Comstock Laws were a series of federal acts in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. These laws were named after their chief architect, Anthony Comstock, a zealous advocate against what he saw as “vices.” Comstock succeeded in passing the first of these laws in 1873. They were designed to prohibit and regulate the distribution of materials deemed to be obscene, immoral, or indecent, particularly related to contraception and information about birth control. Birth control is a broad term used to describe devices or chemicals that could help prevent pregnancy. They include all forms of condoms, hormones, implantable devices in the vagina, and sterilization. People like Comstock believed that birth control would cause people to have riskier sex because the threat of pregnancy would be removed. Many religious people also believed that sex should be reserved solely for the purpose of reproduction.

Under the Comstock Laws, it was illegal to send through the mail any materials, including books, pamphlets, and contraceptives, that were considered obscene or lewd. The laws also targeted the distribution of information about abortion and contraception, making it punishable by imprisonment or fines.

Because men were the doctors, the lawyers, and the government officials, women had little say in the passage of these laws. Even today women make up a small minority in all of those professions.

Women of the late 19th century didn’t take these laws sitting down. Emma Goldman, for example, was an influential political activist and writer, born in 1869 in the Russian Empire (now Lithuania) and later emigrated to the United States. She played a prominent role in various social and political movements, advocating for women's rights, workers' rights, free speech, and anarchism.

Margaret Sanger, Public Domain

Margaret Sanger, Public Domain

Margaret Sanger:

Perhaps the most well-known advocate of birth control was Margaret Sanger, the founder of Planned Parenthood. When Margaret Sanger opened her clinic on Manhattan’s Lower East Side in 1916, immigrant women from Eastern and Southern Europe, the majority of whom were Catholic or Orthodox Jewish, flocked to her for help. Her goal was to distribute information on contraception in order to help women plan the birth of their children and avoid dangerous “back alley abortions” that frequently caused death. Sanger was arrested and tried under New York’‘s Comstock Laws for informing women about methods of contraception.

Prior to Sanger’s crusade for safe contraception, doctors had little advice to offer to women who wished to avoid pregnancy. One woman told Sanger that her doctor had only advised her to tell her husband to “sleep on the roof” in order to avoid sex altogether. Clearly, such advice did not provide effective birth control, and was meaningless in a society where women were unable to deny their husband’s sexual advances.

Sanger founded the American Birth Control League in 1921 to promote her pro-contraception philosophy.This organization was the precursor of The Planned Parenthood Federation of

America , an organization that fights for reproductive freedom for all people.

Sanger’s unfortunate advocacy of Eugenics as a means of controlling population tarnished her reputation. Eugenics was a science that promoted the idea of “better breeding;” however, the means through which this was accomplished was often through the sterilizing, or making it impossible for them to have children, of undesirable portions of the population, typically racial and religious minorities. The theory used Darwinism to suggest that a population could be “strengthened” by inhibiting the reproduction of its “weakest” people. Eugenics was widespread in the US and western Europe and was foundational to Nazi ideology leading up to World War II. Because of the Nazi’s application of Eugenics to justify exterminating the Jewish population, Eugenics was discredited as pseudoscience that disguised racism.

Margarett Sanger and others shifted away from Eugenics to support “family planning,” which instead of stopping certain populations from having children, gave them options and support to control when they had children. Elements of eugenicist thinking survived in the US, but the legal and political emphasis shifted to providing significant support for the poorest in American society. One part of that assistance was information on family planning so that families could devote their resources to supporting their living children.

Perhaps the most well-known advocate of birth control was Margaret Sanger, the founder of Planned Parenthood. When Margaret Sanger opened her clinic on Manhattan’s Lower East Side in 1916, immigrant women from Eastern and Southern Europe, the majority of whom were Catholic or Orthodox Jewish, flocked to her for help. Her goal was to distribute information on contraception in order to help women plan the birth of their children and avoid dangerous “back alley abortions” that frequently caused death. Sanger was arrested and tried under New York’‘s Comstock Laws for informing women about methods of contraception.

Prior to Sanger’s crusade for safe contraception, doctors had little advice to offer to women who wished to avoid pregnancy. One woman told Sanger that her doctor had only advised her to tell her husband to “sleep on the roof” in order to avoid sex altogether. Clearly, such advice did not provide effective birth control, and was meaningless in a society where women were unable to deny their husband’s sexual advances.

Sanger founded the American Birth Control League in 1921 to promote her pro-contraception philosophy.This organization was the precursor of The Planned Parenthood Federation of

America , an organization that fights for reproductive freedom for all people.

Sanger’s unfortunate advocacy of Eugenics as a means of controlling population tarnished her reputation. Eugenics was a science that promoted the idea of “better breeding;” however, the means through which this was accomplished was often through the sterilizing, or making it impossible for them to have children, of undesirable portions of the population, typically racial and religious minorities. The theory used Darwinism to suggest that a population could be “strengthened” by inhibiting the reproduction of its “weakest” people. Eugenics was widespread in the US and western Europe and was foundational to Nazi ideology leading up to World War II. Because of the Nazi’s application of Eugenics to justify exterminating the Jewish population, Eugenics was discredited as pseudoscience that disguised racism.

Margarett Sanger and others shifted away from Eugenics to support “family planning,” which instead of stopping certain populations from having children, gave them options and support to control when they had children. Elements of eugenicist thinking survived in the US, but the legal and political emphasis shifted to providing significant support for the poorest in American society. One part of that assistance was information on family planning so that families could devote their resources to supporting their living children.

Katharine Dexter McCormick, Wikimedia Commons

Katharine Dexter McCormick, Wikimedia Commons

The Pill:

Then in the late 1950s early 1960s a scientific revolution made contraceptives easier and more effective. As early as the 1940s, Margaret Sanger, as president of Planned Parenthood, closely monitored and funded birth control research. Sanger's friend, Katharine Dexter McCormick, generously funded research for an oral contraceptive, which people theorized would be more effective. McCormick was a women's rights advocate and a graduate of MIT. She contributed to the suffrage movement and League of Women Voters. After her husband's passing, she pledged $10,000 and later provided annual contributions exceeding $150,000 annually for contraceptive research.

The development of the oral contraceptive relied on ancient Aztec medical traditions. Russell Marker discovered the contraceptive properties of the Barbasco root, from which progestin was extracted and combined with estrogen by Gregory Pincus to create the first pill. McCormick funded initial clinical trials conducted by Dr. John Rock, a renowned gynecologist and devout Catholic. Rock's book advocating for the acceptance of the oral contraceptive by the Catholic Church was unsuccessful.

Due to Massachusetts' restrictive laws, Rock chose Puerto Rico for trials, where contraception was legal, birth control clinics existed, and trusted US-trained medical practitioners were present. Puerto Rican women desired effective birth control. The trials required specific criteria for participation, and they began in April 1956 with ongoing successes reported. The FDA approved the pill for menstrual regulation in 1957 and for sale in 1960. While this was an important milestone, it is important to recognize that these trials in Puerto Rico were also somewhat problematic. As testing evolved from things like sperimicides and jellies–which are far less effective–some scientists ascribed their lower success rates to Puerto Rican women’s presumed fecundity, hypersexuality, and lower intelligence rates. Though many Puerto Rican wanted access to birth control, this also put them in direct contact with white American scientists who came to Puerto Rico with their own existing racial ideologies that were informed by decades of US imperialism on the island. As such, Puerto Rico also became a site where abuses ran rampant–by the 1980s, it was discovered that more than ⅓ of Puerto Rican women had been coerced into sterilization procedures–la operación–or permanent birth control.

Enovid, the first oral contraceptive, gained popularity, with one in four married women under 45 using it by 1965. Sanger's efforts established family planning as the norm, significantly reducing unintended pregnancies. The first pill had higher hormone levels than necessary, unlike current lower-dose pills and thus had lots of side effects. It took time for doctors to figure out the root issues, and scientists to figure out the lowest effective dosages.

Then in the late 1950s early 1960s a scientific revolution made contraceptives easier and more effective. As early as the 1940s, Margaret Sanger, as president of Planned Parenthood, closely monitored and funded birth control research. Sanger's friend, Katharine Dexter McCormick, generously funded research for an oral contraceptive, which people theorized would be more effective. McCormick was a women's rights advocate and a graduate of MIT. She contributed to the suffrage movement and League of Women Voters. After her husband's passing, she pledged $10,000 and later provided annual contributions exceeding $150,000 annually for contraceptive research.

The development of the oral contraceptive relied on ancient Aztec medical traditions. Russell Marker discovered the contraceptive properties of the Barbasco root, from which progestin was extracted and combined with estrogen by Gregory Pincus to create the first pill. McCormick funded initial clinical trials conducted by Dr. John Rock, a renowned gynecologist and devout Catholic. Rock's book advocating for the acceptance of the oral contraceptive by the Catholic Church was unsuccessful.

Due to Massachusetts' restrictive laws, Rock chose Puerto Rico for trials, where contraception was legal, birth control clinics existed, and trusted US-trained medical practitioners were present. Puerto Rican women desired effective birth control. The trials required specific criteria for participation, and they began in April 1956 with ongoing successes reported. The FDA approved the pill for menstrual regulation in 1957 and for sale in 1960. While this was an important milestone, it is important to recognize that these trials in Puerto Rico were also somewhat problematic. As testing evolved from things like sperimicides and jellies–which are far less effective–some scientists ascribed their lower success rates to Puerto Rican women’s presumed fecundity, hypersexuality, and lower intelligence rates. Though many Puerto Rican wanted access to birth control, this also put them in direct contact with white American scientists who came to Puerto Rico with their own existing racial ideologies that were informed by decades of US imperialism on the island. As such, Puerto Rico also became a site where abuses ran rampant–by the 1980s, it was discovered that more than ⅓ of Puerto Rican women had been coerced into sterilization procedures–la operación–or permanent birth control.

Enovid, the first oral contraceptive, gained popularity, with one in four married women under 45 using it by 1965. Sanger's efforts established family planning as the norm, significantly reducing unintended pregnancies. The first pill had higher hormone levels than necessary, unlike current lower-dose pills and thus had lots of side effects. It took time for doctors to figure out the root issues, and scientists to figure out the lowest effective dosages.

Estelle Griswold, Public Domain

Estelle Griswold, Public Domain

Griswold v. Connecticut:

Finally, that same year, 1965 the Supreme Court ruled in Griswold v. Connecticut that married couples had a right to utilize birth control methods based on the right to privacy that is suggested but not explicitly defined in the 14th Amendment of the US Constitution. The plaintiffs were Estelle Griswold, who was the executive director of the Planned Parenthood League of Connecticut at the time, and Dr. C. Lee Buxton, who was a physician and a professor at the Yale School of Medicine. They challenged the constitutionality of a Connecticut law that criminalized the use of contraceptives, even by married couples.

Estelle Griswold and Dr. Buxton were arrested and convicted for providing contraceptive advice and services to married individuals. They argued that the Connecticut law violated the right to privacy and interfered with the intimate decisions made by married couples regarding family planning. This case was landmark and led to other cases that expanded reproductive freedoms to unmarried couples, like Eisenstadt v. Baird.

Finally, that same year, 1965 the Supreme Court ruled in Griswold v. Connecticut that married couples had a right to utilize birth control methods based on the right to privacy that is suggested but not explicitly defined in the 14th Amendment of the US Constitution. The plaintiffs were Estelle Griswold, who was the executive director of the Planned Parenthood League of Connecticut at the time, and Dr. C. Lee Buxton, who was a physician and a professor at the Yale School of Medicine. They challenged the constitutionality of a Connecticut law that criminalized the use of contraceptives, even by married couples.

Estelle Griswold and Dr. Buxton were arrested and convicted for providing contraceptive advice and services to married individuals. They argued that the Connecticut law violated the right to privacy and interfered with the intimate decisions made by married couples regarding family planning. This case was landmark and led to other cases that expanded reproductive freedoms to unmarried couples, like Eisenstadt v. Baird.

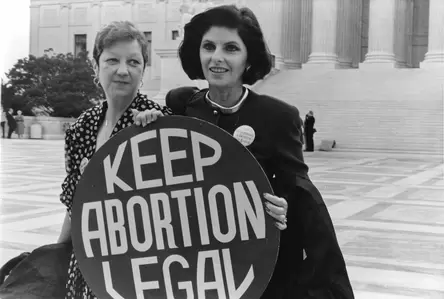

Norma McCorvey and her attorney, Wikimedia Commons

Norma McCorvey and her attorney, Wikimedia Commons

Roe v. Wade:

Reproductive freedom isn’t just about preventing pregnancy, it’s about the freedom to decide what happens to one’s body, control your financial future, and make the choice to be a mom. Some people have argued that consenting to sex is tacit consent to be a mother, but the long history of the patriarchy shows that the same or tacit consent has not fallen equally on men with fatherhood. Therefore some feminists argue that this argument is rooted in misogyn and a sexual double standard for women.

Abortion is a broad medical term that refers to termination of a pregnancy. It includes spontaneous abortions and induced abortions. Spontaneous abortions are often euphemistically referred to as “miscarriages;” however, in professional medical parlance (like the GTPAL acronym that defines a women’s reproductive medical history), the term is abortion. Induced abortions are what we socially think of as “abortion.”

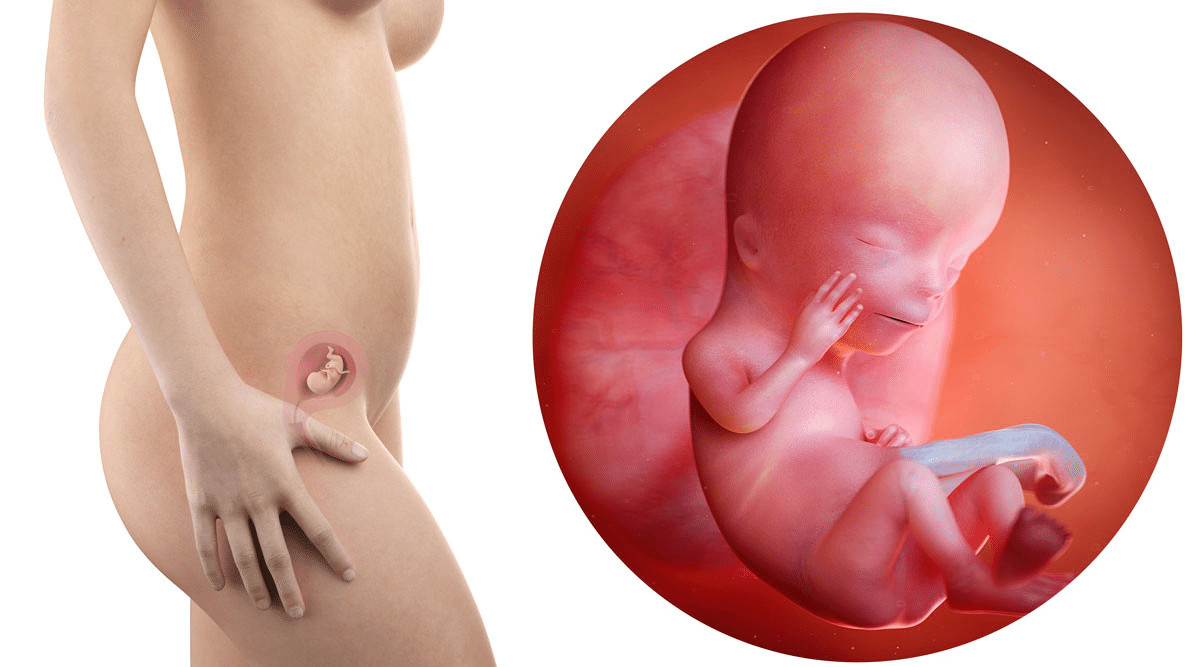

When it comes to induced abortions, they can be performed at any stage of a pregnancy; however, according to data from 2020, 93% of abortions happen before 13-weeks gestation (within the first trimester). This is before the mother is noticeably pregnant, before the fetus can be felt moving around, and before fetal viability. Abortions before nine weeks are typically done using medications that block hormone signals to the pregnancy and cause the uterus to contract and expel the embryo, a term for the cells that eventually become a fetus at 9 weeks.

Statistically few abortions occur in the second and third trimesters. 5.8% of abortions occur between 14 and 20 weeks of pregnancy, which is in the second trimester. 20 weeks is around when fetal movement can be felt. Induced abortions that occur in the second and third trimester almost always are performed because of potential health risks to the pregnant woman or fetus. As it stands, most prenatal screenings for fetal diseases or defects cannot be performed until the second trimester–thus delaying when it is feasible for a woman who discovers her fetus carries some type of disease to acquire an abortion. Less than 1% of abortions happen after 20 weeks and it is usually an extreme, health related circumstance. Abortions that happen after medication is effective are performed surgically and involve a doctor using tools to terminate the pregnancy.

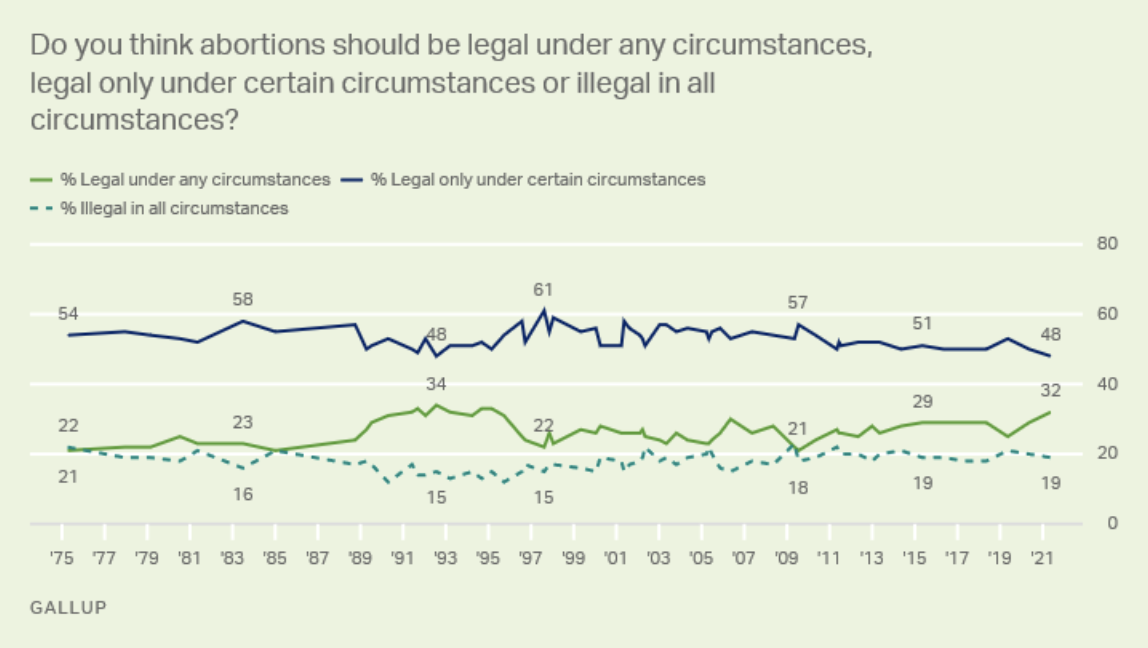

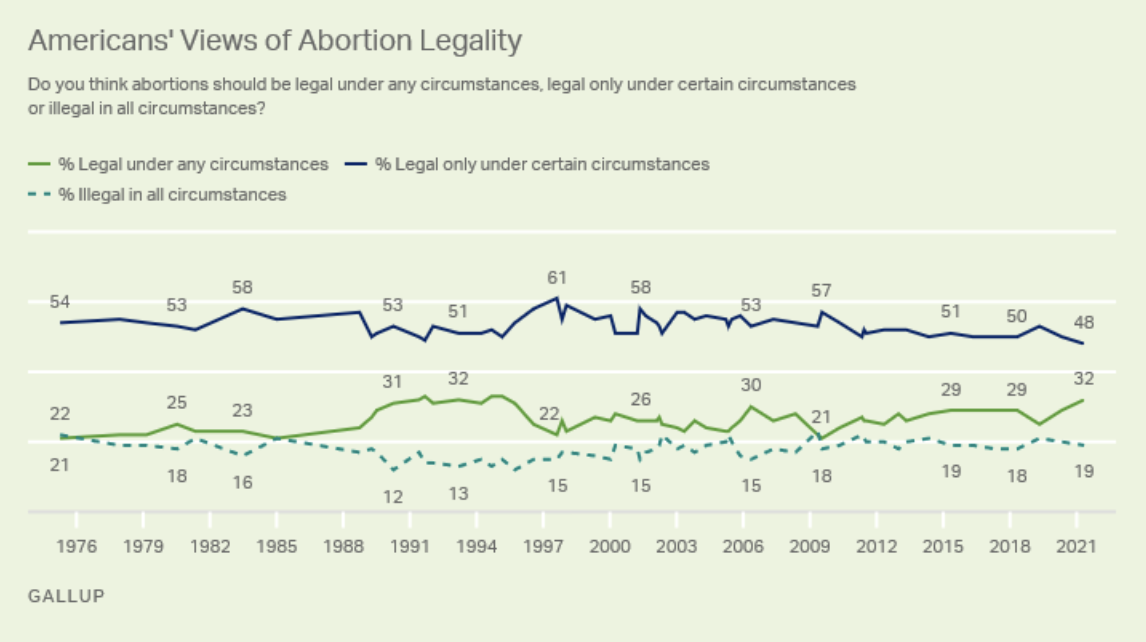

In the politicized discussions around abortion, much has been made about the pain mothers and, or fetus’ feel during abortion. Studies have shown that for pregnant people, abortion is safer than carrying a pregnancy to term and birth. This was also true for most of US history. Pregnancy is not a health-neutral event and carries with it risks–including the risk of death. For the embryo or fetus, abortion ends the lifelike activity, but it is debated by professionals how painful this is and the evidence varies by when the abortion is performed. Public opinion polls have varied since the 1960s on abortion, most people agree it is ending life, but most also feel it’s different from ending the life of something that has been born.

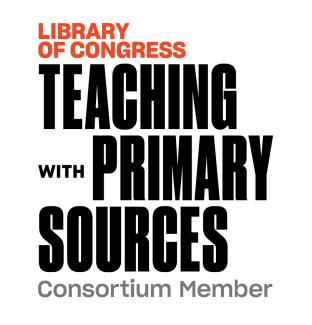

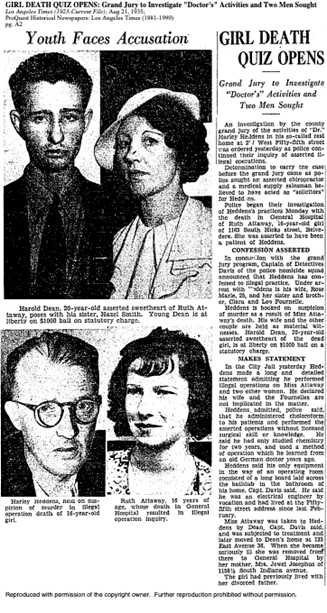

Throughout the early 20th century women and their doctors were put on trial for violating state abortion laws. By 1910, abortion was illegal in every state in the US. Only some states had built in exceptions to save the mother’s life. The decision of when a mother’s life was in jeopardy was left to doctors, who were almost all men, and these standards were not universal.

Making abortion illegal, also known as criminalizing it, simply meant that more women turned away from qualified people to have abortions. Getting abortions under extreme circumstances by people willing to do something illegal, resulted in an increased death toll for mothers. Abortion was not inherently unsafe, illegal abortion was. In 1930, nearly 2,700 US women died from an illegal abortion, or one in five maternal deaths that year.

Doctors caught performing abortions were put on trial and lost their medical licenses. Increasingly the press covered stories about women who had died from an illegal abortion. Women’s bodies were found in barrels, chopped up in suitcases, all after a botched abortion by someone unqualified. People began calling for abortion law reform.

But more importantly, women began appearing in court to give testimony as to why they wanted one in the first place. Abortion was so stigmatized that women never talked about it. Stories of safe, successful abortions were never in the press; however, stories about illegal abortions that resulted in death sold papers. Thus, the effect of criminalization was that women who were accused were forced to talk about it publicly. Women who believed they would never get an abortion listened to abortion stories and empathized with the mothers choice, given her circumstances. Criminalization forced women to talk about their darkest moments in a very public forum.

In 1955, Planned Parenthood called for a national conference on abortion. The few doctors who attended called for greater flexibility for doctors to perform abortions. These doctors had personally witnessed women dying from pregnancy-related causes unable to help them, or watched women carry babies to term knowing the baby could not survive more than a week or so.

Then in the 1960s a drug often prescribed to women to treat pregnancy discomforts, like morning sickness, was found to cause birth defects in babies. A television personality, Sherri Chessen Finkbine was expecting her fifth child when she consumed tranquilizers that her husband brought from England to relieve her nausea, the drug thalidomide. However, after reading an article about thalidomide that discussed its role in the birth of thousands of babies born without arms or legs, Finkbine became worried about the potential harm to her unborn child. Finkbine's doctor confirmed her fears, but at the time, there was no test to assess the fetus's condition. So, following her doctor's suggestion, Finkbine and her husband decided to quietly have an abortion. Abortion in Arizona was illegal, so they ended up traveling to Sweden. Her case was public and public opinion polls showed that 52% of Americans supported her choice under the circumstances.

Ironically, the United States did not witness a pharmaceutical disaster on par with Europe related to Thalidomide because of one scientist at the Food and Drug Administration (FDA): Dr. Frances Kathleen Oldham Kelsey. Dr. Kelsey worked for the American Medical Association and eventually taught pharmacology at the University of South Dakota. In addition to her Ph.D., she also had her medical degree and briefly worked as general practitioner. It was in her first month in her position at the FDA that Dr. Kelsey was taked with evaluating the drug thalidomide for approval in the United States. When the manufacturers of thalidomide submitted their information to Dr. Kelsey, she didn’t believe they had provided adequate data to show its safety and asked them to resubmit their application once they had effectively proved its safety. The manufacturers were frustrated by this woman’s attempt to slow their approval process for a drug that was already in widespread use in Europe. Instead of conducting the new tests and submitting a new report, the manufacturers attempted to pressure and coerce Dr. Kelsey into approval. However, she held firm–trusting her extensive expertise. This back-and-forth is what ultimately caused enough of a delay for word to spread of fetal anomalies and defects in Europe related to thalidomide use by pregnant women. After a congressional hearing on the matter, Dr. Kelsey was able to ensure that thalidomide would be banned in the United States. In 1962, just a year later, President John F. Kennedy granted Dr. Kelsey the President's Award for Distinguished Federal Civilian Service. She was only the second woman to ever receive the award. Kennedy acknowledged "Her exceptional judgment in evaluating a new drug for safety for human use…” In the immediate aftermath of the thalidomide disaster, Dr. Kelsey helped change laws about drug approval to protect the patient, ensure informed consent in clinical trials, and reporting of adverse side effects to the FDA. In her long and distinguished career at the FDA, Dr. Kelsey would eventually become chief of the Division of New Drugs, director of the Division of Scientific Investigations, and deputy for Scientific and Medical Affairs in the Office of Compliance. She retired in 2005, at the age of 90, after 45 years of service.

Dr. Kelsey receiving the President’s Award for Distinguished Federal Civilian Service from President Kennedy. National Library of Medicine, Images from the History of Medicine.

While thousands of babies would be born with thalidomide-related deformities, the United States was spared from a tragedy of that scale. However, when combined with the realization that many of these women in Europe were married and otherwise respectable women and mothers, this public concern about disabled babies–in an era when disability was considered shameful–helped to open the door for discussions about elective abortion and relaxing existing abortion laws.

Despite the stereotype of the young, naive, and sexually promiscuous girl being the ones who get abortions, studies showed that women who were already mothers were more likely to get abortions and that religiosity was not a factor. Women of all faiths got abortions.

In 1964, abortion law reform activists registered their first national group: the Association for the Study of Abortion (ASA). Then in 1966, a group of nine highly regarded California doctors faced a lawsuit for providing abortions to women who had contracted rubella, a disease that could harm unborn babies. However, doctors from all over the country rallied to support these doctors, with even 128 medical school deans joining their defense. As a result, one of the earliest changes to abortion laws in the United States occurred. California revised its strict ban on abortion to permit hospital committees to review and approve requests for the procedure.

Studies in the 1960s showed that poor women and their families were affected to a greater extent from abortion bans. One study examined low-income women in New York City and found that 8% had tried to end a pregnancy through illegal means. Additionally, 38% reported that someone they knew had attempted to get an abortion. Among the low-income women who admitted having an abortion, 77% said they had attempted a self-induced procedure, while only a small fraction 2% involved a medical professional at all.

By the end of the 1960s there was a full fledged movement to repeal abortion bans. National Association for the Repeal of Abortion Laws (NARAL) was founded in 1969. NARAL became the first nationwide organization dedicated exclusively to advocating for the legalization of abortion. Left and right states were repealing or modifying their abortion stances. Alaska, Hawaii, New York, and Washington completely eliminated their laws prohibiting abortion, while 13 other states introduced changes that broadened the circumstances under which abortion was permitted. Instead of solely permitting abortion to save the life of the mother, these reforms allowed for abortion in situations where the pregnancy posed risks to the patient's physical or mental health, when there were fetal abnormalities, or when the pregnancy resulted from rape or incest. However, much of these changes were piecemeal and state by state. It would not be until 1973 that the question of abortion was answered federally.

The Roe v. Wade decision was a landmark ruling by the United States Supreme Court in 1973 that legalized abortion across the country. The case originated in Texas and involved a woman named Norma McCorvey, referred to as "Jane Roe" to protect her identity, who sought to terminate her pregnancy but was denied access to legal abortion under Texas law. In 1969, when McCorvey became pregnant, she was unmarried, financially struggling, and unable to afford to travel to a state where abortion was legal. This also wasn’t her first pregnancy. Texas law at the time prohibited abortion except to save the life of the mother or in instances of rape. McCorvey's lawyers, Linda Coffee and Sarah Weddington, sought a representative plaintiff who could best illustrate the difficulties faced by women seeking abortions. They aimed to demonstrate that the Texas law violated women's constitutional right to privacy. McCorvey's circumstances and her inability to access a safe and legal abortion made her a suitable candidate for the case.

Reproductive freedom isn’t just about preventing pregnancy, it’s about the freedom to decide what happens to one’s body, control your financial future, and make the choice to be a mom. Some people have argued that consenting to sex is tacit consent to be a mother, but the long history of the patriarchy shows that the same or tacit consent has not fallen equally on men with fatherhood. Therefore some feminists argue that this argument is rooted in misogyn and a sexual double standard for women.

Abortion is a broad medical term that refers to termination of a pregnancy. It includes spontaneous abortions and induced abortions. Spontaneous abortions are often euphemistically referred to as “miscarriages;” however, in professional medical parlance (like the GTPAL acronym that defines a women’s reproductive medical history), the term is abortion. Induced abortions are what we socially think of as “abortion.”

When it comes to induced abortions, they can be performed at any stage of a pregnancy; however, according to data from 2020, 93% of abortions happen before 13-weeks gestation (within the first trimester). This is before the mother is noticeably pregnant, before the fetus can be felt moving around, and before fetal viability. Abortions before nine weeks are typically done using medications that block hormone signals to the pregnancy and cause the uterus to contract and expel the embryo, a term for the cells that eventually become a fetus at 9 weeks.

Statistically few abortions occur in the second and third trimesters. 5.8% of abortions occur between 14 and 20 weeks of pregnancy, which is in the second trimester. 20 weeks is around when fetal movement can be felt. Induced abortions that occur in the second and third trimester almost always are performed because of potential health risks to the pregnant woman or fetus. As it stands, most prenatal screenings for fetal diseases or defects cannot be performed until the second trimester–thus delaying when it is feasible for a woman who discovers her fetus carries some type of disease to acquire an abortion. Less than 1% of abortions happen after 20 weeks and it is usually an extreme, health related circumstance. Abortions that happen after medication is effective are performed surgically and involve a doctor using tools to terminate the pregnancy.

In the politicized discussions around abortion, much has been made about the pain mothers and, or fetus’ feel during abortion. Studies have shown that for pregnant people, abortion is safer than carrying a pregnancy to term and birth. This was also true for most of US history. Pregnancy is not a health-neutral event and carries with it risks–including the risk of death. For the embryo or fetus, abortion ends the lifelike activity, but it is debated by professionals how painful this is and the evidence varies by when the abortion is performed. Public opinion polls have varied since the 1960s on abortion, most people agree it is ending life, but most also feel it’s different from ending the life of something that has been born.

Throughout the early 20th century women and their doctors were put on trial for violating state abortion laws. By 1910, abortion was illegal in every state in the US. Only some states had built in exceptions to save the mother’s life. The decision of when a mother’s life was in jeopardy was left to doctors, who were almost all men, and these standards were not universal.

Making abortion illegal, also known as criminalizing it, simply meant that more women turned away from qualified people to have abortions. Getting abortions under extreme circumstances by people willing to do something illegal, resulted in an increased death toll for mothers. Abortion was not inherently unsafe, illegal abortion was. In 1930, nearly 2,700 US women died from an illegal abortion, or one in five maternal deaths that year.

Doctors caught performing abortions were put on trial and lost their medical licenses. Increasingly the press covered stories about women who had died from an illegal abortion. Women’s bodies were found in barrels, chopped up in suitcases, all after a botched abortion by someone unqualified. People began calling for abortion law reform.

But more importantly, women began appearing in court to give testimony as to why they wanted one in the first place. Abortion was so stigmatized that women never talked about it. Stories of safe, successful abortions were never in the press; however, stories about illegal abortions that resulted in death sold papers. Thus, the effect of criminalization was that women who were accused were forced to talk about it publicly. Women who believed they would never get an abortion listened to abortion stories and empathized with the mothers choice, given her circumstances. Criminalization forced women to talk about their darkest moments in a very public forum.

In 1955, Planned Parenthood called for a national conference on abortion. The few doctors who attended called for greater flexibility for doctors to perform abortions. These doctors had personally witnessed women dying from pregnancy-related causes unable to help them, or watched women carry babies to term knowing the baby could not survive more than a week or so.

Then in the 1960s a drug often prescribed to women to treat pregnancy discomforts, like morning sickness, was found to cause birth defects in babies. A television personality, Sherri Chessen Finkbine was expecting her fifth child when she consumed tranquilizers that her husband brought from England to relieve her nausea, the drug thalidomide. However, after reading an article about thalidomide that discussed its role in the birth of thousands of babies born without arms or legs, Finkbine became worried about the potential harm to her unborn child. Finkbine's doctor confirmed her fears, but at the time, there was no test to assess the fetus's condition. So, following her doctor's suggestion, Finkbine and her husband decided to quietly have an abortion. Abortion in Arizona was illegal, so they ended up traveling to Sweden. Her case was public and public opinion polls showed that 52% of Americans supported her choice under the circumstances.

Ironically, the United States did not witness a pharmaceutical disaster on par with Europe related to Thalidomide because of one scientist at the Food and Drug Administration (FDA): Dr. Frances Kathleen Oldham Kelsey. Dr. Kelsey worked for the American Medical Association and eventually taught pharmacology at the University of South Dakota. In addition to her Ph.D., she also had her medical degree and briefly worked as general practitioner. It was in her first month in her position at the FDA that Dr. Kelsey was taked with evaluating the drug thalidomide for approval in the United States. When the manufacturers of thalidomide submitted their information to Dr. Kelsey, she didn’t believe they had provided adequate data to show its safety and asked them to resubmit their application once they had effectively proved its safety. The manufacturers were frustrated by this woman’s attempt to slow their approval process for a drug that was already in widespread use in Europe. Instead of conducting the new tests and submitting a new report, the manufacturers attempted to pressure and coerce Dr. Kelsey into approval. However, she held firm–trusting her extensive expertise. This back-and-forth is what ultimately caused enough of a delay for word to spread of fetal anomalies and defects in Europe related to thalidomide use by pregnant women. After a congressional hearing on the matter, Dr. Kelsey was able to ensure that thalidomide would be banned in the United States. In 1962, just a year later, President John F. Kennedy granted Dr. Kelsey the President's Award for Distinguished Federal Civilian Service. She was only the second woman to ever receive the award. Kennedy acknowledged "Her exceptional judgment in evaluating a new drug for safety for human use…” In the immediate aftermath of the thalidomide disaster, Dr. Kelsey helped change laws about drug approval to protect the patient, ensure informed consent in clinical trials, and reporting of adverse side effects to the FDA. In her long and distinguished career at the FDA, Dr. Kelsey would eventually become chief of the Division of New Drugs, director of the Division of Scientific Investigations, and deputy for Scientific and Medical Affairs in the Office of Compliance. She retired in 2005, at the age of 90, after 45 years of service.

Dr. Kelsey receiving the President’s Award for Distinguished Federal Civilian Service from President Kennedy. National Library of Medicine, Images from the History of Medicine.

While thousands of babies would be born with thalidomide-related deformities, the United States was spared from a tragedy of that scale. However, when combined with the realization that many of these women in Europe were married and otherwise respectable women and mothers, this public concern about disabled babies–in an era when disability was considered shameful–helped to open the door for discussions about elective abortion and relaxing existing abortion laws.

Despite the stereotype of the young, naive, and sexually promiscuous girl being the ones who get abortions, studies showed that women who were already mothers were more likely to get abortions and that religiosity was not a factor. Women of all faiths got abortions.

In 1964, abortion law reform activists registered their first national group: the Association for the Study of Abortion (ASA). Then in 1966, a group of nine highly regarded California doctors faced a lawsuit for providing abortions to women who had contracted rubella, a disease that could harm unborn babies. However, doctors from all over the country rallied to support these doctors, with even 128 medical school deans joining their defense. As a result, one of the earliest changes to abortion laws in the United States occurred. California revised its strict ban on abortion to permit hospital committees to review and approve requests for the procedure.

Studies in the 1960s showed that poor women and their families were affected to a greater extent from abortion bans. One study examined low-income women in New York City and found that 8% had tried to end a pregnancy through illegal means. Additionally, 38% reported that someone they knew had attempted to get an abortion. Among the low-income women who admitted having an abortion, 77% said they had attempted a self-induced procedure, while only a small fraction 2% involved a medical professional at all.

By the end of the 1960s there was a full fledged movement to repeal abortion bans. National Association for the Repeal of Abortion Laws (NARAL) was founded in 1969. NARAL became the first nationwide organization dedicated exclusively to advocating for the legalization of abortion. Left and right states were repealing or modifying their abortion stances. Alaska, Hawaii, New York, and Washington completely eliminated their laws prohibiting abortion, while 13 other states introduced changes that broadened the circumstances under which abortion was permitted. Instead of solely permitting abortion to save the life of the mother, these reforms allowed for abortion in situations where the pregnancy posed risks to the patient's physical or mental health, when there were fetal abnormalities, or when the pregnancy resulted from rape or incest. However, much of these changes were piecemeal and state by state. It would not be until 1973 that the question of abortion was answered federally.

The Roe v. Wade decision was a landmark ruling by the United States Supreme Court in 1973 that legalized abortion across the country. The case originated in Texas and involved a woman named Norma McCorvey, referred to as "Jane Roe" to protect her identity, who sought to terminate her pregnancy but was denied access to legal abortion under Texas law. In 1969, when McCorvey became pregnant, she was unmarried, financially struggling, and unable to afford to travel to a state where abortion was legal. This also wasn’t her first pregnancy. Texas law at the time prohibited abortion except to save the life of the mother or in instances of rape. McCorvey's lawyers, Linda Coffee and Sarah Weddington, sought a representative plaintiff who could best illustrate the difficulties faced by women seeking abortions. They aimed to demonstrate that the Texas law violated women's constitutional right to privacy. McCorvey's circumstances and her inability to access a safe and legal abortion made her a suitable candidate for the case.

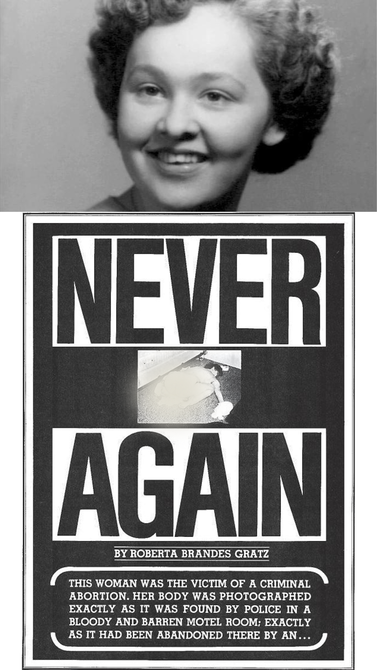

Gerri Santoro in life over the Ms. Magazine cover from 1972 with heading, "Never Again," Public Domain

Gerri Santoro in life over the Ms. Magazine cover from 1972 with heading, "Never Again," Public Domain

Ultimately, building on Griswold v. Connecticut, the Supreme Court, in a 7-2 decision, held that a woman's constitutional right to privacy, as protected by the 14th Amendment, includes the right to choose whether to have an abortion. The Court recognized that this right is not absolute and must be balanced against the government's interest in protecting the potential life of the fetus. It established a framework based on testimony from doctors using the trimesters of pregnancy to determine when and how states could regulate abortion.

In the first trimester, the Court held that the decision to have an abortion should be solely between a woman and her doctor, with minimal government interference. Since the fetus was not viable and legal abortion in the first trimester posed few medical risks, the government’s right to regulate was limited. In the second trimester, the state has a legitimate interest in protecting the woman's health and may regulate abortion to some degree–particularly since second trimester abortions were more dangerous than first trimester abortions, and the fetus was approaching viability. Later court decisions would indicate that these regulations should not impose an "undue burden" on a woman's right to access abortion. In the third trimester, the state's interest in protecting potential life becomes more compelling, and it may prohibit abortion except when necessary to protect the woman's life or health. With the court’s decision in Roe v. Wade, the federal government granted women a right to bodily autonomy, to make their own decisions in family planning, and to engage in sexual relations with the same freedom as men.

It's worth noting that McCorvey never had an abortion during the legal proceedings. By the time the Supreme Court ruled in 1973, she had given birth and placed her child up for adoption.

After the legalization of abortion nationwide, Ms. Magazine, a feminist publication, ran a picture of Gerri Santoro, a young mother who died when her boyfriend tried to perform an abortion on her in a motel room, on their cover. Santoro’s ex-husband was abusive. She fled from him with their children and started a new relationship; however, she never actually divorced her husband. Soon after learning she was pregnant with her boyfriend’s child, her estranged husband contacted her to let her know he would be visiting to see their children. Santoro was terrified he would kill her if he found out she was pregnant with another man’s child, or that he would use her pregnancy with another man in order to take their children away. She and her boyfriend tried to do the abortion themselves, borrowing a medical textbook from the local library. When she began hemorrhaging blood, her boyfriend fled the scene. Ms. Magazine hoped that by telling Santoro’s story people would see how illegal abortion impacted individual women’s lives.

In 1976, the Congress passed the Hyde Amendment to prevent federal funds from being used to support abortions. The funds came from medicaid, a government sponsored insurance program that helps low income families. Women who receive medicaid could not use that insurance to get an abortion. This restriction is still in place today and primarily affects the poor, Black, Latino, and LGBTQ+ communities that predominantly use Medicaid. Women in these categories then are faced with barriers to getting abortions that their wealthier sisters do not. Reproductive Freedom is only possible if the financial and social barriers to freedoms are removed.

In the first trimester, the Court held that the decision to have an abortion should be solely between a woman and her doctor, with minimal government interference. Since the fetus was not viable and legal abortion in the first trimester posed few medical risks, the government’s right to regulate was limited. In the second trimester, the state has a legitimate interest in protecting the woman's health and may regulate abortion to some degree–particularly since second trimester abortions were more dangerous than first trimester abortions, and the fetus was approaching viability. Later court decisions would indicate that these regulations should not impose an "undue burden" on a woman's right to access abortion. In the third trimester, the state's interest in protecting potential life becomes more compelling, and it may prohibit abortion except when necessary to protect the woman's life or health. With the court’s decision in Roe v. Wade, the federal government granted women a right to bodily autonomy, to make their own decisions in family planning, and to engage in sexual relations with the same freedom as men.

It's worth noting that McCorvey never had an abortion during the legal proceedings. By the time the Supreme Court ruled in 1973, she had given birth and placed her child up for adoption.

After the legalization of abortion nationwide, Ms. Magazine, a feminist publication, ran a picture of Gerri Santoro, a young mother who died when her boyfriend tried to perform an abortion on her in a motel room, on their cover. Santoro’s ex-husband was abusive. She fled from him with their children and started a new relationship; however, she never actually divorced her husband. Soon after learning she was pregnant with her boyfriend’s child, her estranged husband contacted her to let her know he would be visiting to see their children. Santoro was terrified he would kill her if he found out she was pregnant with another man’s child, or that he would use her pregnancy with another man in order to take their children away. She and her boyfriend tried to do the abortion themselves, borrowing a medical textbook from the local library. When she began hemorrhaging blood, her boyfriend fled the scene. Ms. Magazine hoped that by telling Santoro’s story people would see how illegal abortion impacted individual women’s lives.

In 1976, the Congress passed the Hyde Amendment to prevent federal funds from being used to support abortions. The funds came from medicaid, a government sponsored insurance program that helps low income families. Women who receive medicaid could not use that insurance to get an abortion. This restriction is still in place today and primarily affects the poor, Black, Latino, and LGBTQ+ communities that predominantly use Medicaid. Women in these categories then are faced with barriers to getting abortions that their wealthier sisters do not. Reproductive Freedom is only possible if the financial and social barriers to freedoms are removed.

Fannie Lou Hammer, Public Domain

Fannie Lou Hammer, Public Domain

Madrigal v. Quilligan:

A key tenant to Reproductive Justice is the idea of consent, which continued to be a problem through the second half of the 20th century. Family planning initiatives tied to economic policies to end poverty, known as the War on Poverty, funded non-consensual sterilizations of primarily Black and brown women in the 1960s and 1970s.

Fannie Lou Hamer, for example, was an activist and a critically important part of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s. She was a leading organizer of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) which played an important role in voter registration drives. She was often one of the only women at the protests.

Earlier in her life, Hamer had seen a physician in Mississippi for removal of a uterine tumor. This was a minor procedure, but Hamer left the hospital only to find out the doctor had also sterilized her without her consent. Hamer later stated, “[In] the North Sunflower County Hospital,...about six out of the 10 Negro women that go to the hospital are sterilized with the tubes tied.”

Some women were sterilized during Cesarean sections and never told, others were threatened with termination of welfare benefits or denial of medical care if they didn’t “consent” to the procedure, others received unnecessary hysterectomies (the surgical removal of the uterus) at teaching hospitals as practice for medical residents. In the South it was such a widespread practice that it had a euphemism: a “Mississippi appendectomy.”

Madrigal v. Quilligan was a class action lawsuit brought on by 10 Latina women in 1978 who represented more than 140 others. These women argued that physicians at the Los Angeles County General Hospital coerced them in the middle of childbirth to consent to surgical sterilization. In some instances, the women were deliberately lied to and told they were consenting to C-sections; in other instances, the women agreed to the surgical sterilizations because they were told they’d die if they got pregnant again, or that the doctors would not assist with childbirth unless they agreed. Some women were presented with consent forms in English, even if the woman signing only had a working understanding of Spanish. In the most extreme instances, the women were not told they had this procedure done at all. They only found out later when they were trying to conceive again.

The Madrigal case illustrates a convergence of the intersections of sex, gender, citizenship, language and culture. Even though the plaintiffs presented a compelling case, a judge ruled in favor of the physicians stating “the staff of a busy metropolitan hospital” had no way of knowing about these women’s “atypical cultural traits.”

In the Madrigal case, it was clear race and sexuality were central to making these women subordinated persons. In the context of the era, many white feminists were calling for access to birth control while minority women were calling for personhood: two very different focus points. For the most part, people of color and their parenting abilities were judged against standards based on white, middle class families. And often, they were found short or lacking by medical professionals and social workers.

A key tenant to Reproductive Justice is the idea of consent, which continued to be a problem through the second half of the 20th century. Family planning initiatives tied to economic policies to end poverty, known as the War on Poverty, funded non-consensual sterilizations of primarily Black and brown women in the 1960s and 1970s.

Fannie Lou Hamer, for example, was an activist and a critically important part of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s. She was a leading organizer of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) which played an important role in voter registration drives. She was often one of the only women at the protests.

Earlier in her life, Hamer had seen a physician in Mississippi for removal of a uterine tumor. This was a minor procedure, but Hamer left the hospital only to find out the doctor had also sterilized her without her consent. Hamer later stated, “[In] the North Sunflower County Hospital,...about six out of the 10 Negro women that go to the hospital are sterilized with the tubes tied.”

Some women were sterilized during Cesarean sections and never told, others were threatened with termination of welfare benefits or denial of medical care if they didn’t “consent” to the procedure, others received unnecessary hysterectomies (the surgical removal of the uterus) at teaching hospitals as practice for medical residents. In the South it was such a widespread practice that it had a euphemism: a “Mississippi appendectomy.”

Madrigal v. Quilligan was a class action lawsuit brought on by 10 Latina women in 1978 who represented more than 140 others. These women argued that physicians at the Los Angeles County General Hospital coerced them in the middle of childbirth to consent to surgical sterilization. In some instances, the women were deliberately lied to and told they were consenting to C-sections; in other instances, the women agreed to the surgical sterilizations because they were told they’d die if they got pregnant again, or that the doctors would not assist with childbirth unless they agreed. Some women were presented with consent forms in English, even if the woman signing only had a working understanding of Spanish. In the most extreme instances, the women were not told they had this procedure done at all. They only found out later when they were trying to conceive again.

The Madrigal case illustrates a convergence of the intersections of sex, gender, citizenship, language and culture. Even though the plaintiffs presented a compelling case, a judge ruled in favor of the physicians stating “the staff of a busy metropolitan hospital” had no way of knowing about these women’s “atypical cultural traits.”

In the Madrigal case, it was clear race and sexuality were central to making these women subordinated persons. In the context of the era, many white feminists were calling for access to birth control while minority women were calling for personhood: two very different focus points. For the most part, people of color and their parenting abilities were judged against standards based on white, middle class families. And often, they were found short or lacking by medical professionals and social workers.

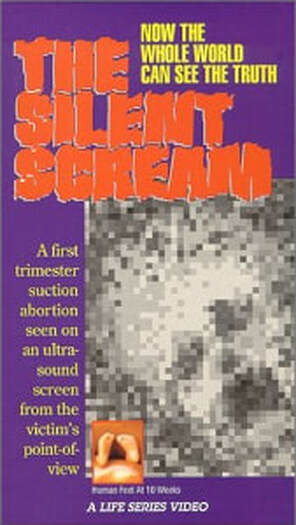

Silent Scream, Public Domain

Silent Scream, Public Domain

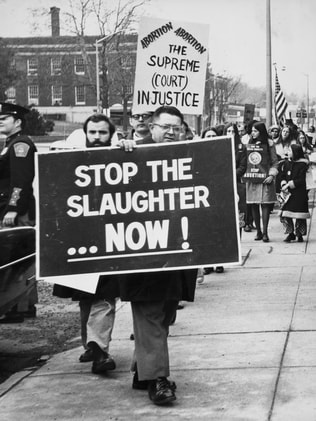

Conservative Opposition:

Many people, women included, opposed and remained opposed to abortion. In 1980, at the end of an era of massive change related to civil and human right enhancements, social shifts gave rise to conservative opposition.

That year anti-abortion activists released a very persuasive propaganda film called Silent Scream. It was a 28-minute long “documentary” of abortion using ultrasound imaging to try and persuade viewers of the wrongs of abortion. It is narrated by an authoritative male voice who claims, "The child," a word chosen to evoke emotion and convey the humanness of the fetus, "senses aggression in its sanctuary" and "agitated" flees from the abortionist’s tools in a "pathetic attempt to escape." The imaging is grainy, but it shows a fetus’ mouth wide open in what the narrator claimed was a "silent scream." This video was altered in a way to support the narrative that abortion was murder.

The video editors adjusted the speed of the video to make it appear like the fetus was thrashing about in pain. Doctors who reviewed the film claimed it was deceptive and argued it used special effects. The editors also showed images of an almost full-term baby but claimed it was 12-weeks old. In reality at 12-weeks old, the mother would not be noticeably pregnant, the fetus would be less than 2 inches long, and the fetus would only just recently have begun to resemble a human form.

Although intentionally altered and misleading, the film was weaponized for political means. Reverend Jerry Falwell, a Baptist pastor, televangelist, and conservative activist who founded the political organization known as the Moral Majority, stated that this film “may win the battle for us." The newly elected Republican President, Ronald Reagan supported the film and hoped every member of Congress would view it, calling the last decade of Reproductive Freedom a “tragedy." Anti-abortion groups had copies of the film mailed to every Congressional representative in order to persuade them to vote against abortion, or at least in favor of restrictions.